1. Introduction

To identify mechanisms that explain how aberrant tissue renewal plays a role in colon tumorigenesis, we studied adenoma morphogenesis in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients. Indeed, tissue renewal determines the rate of cell division. In our quest, discovering why altered tissue kinetics occur was the crux of the matter.

Research Question: How does dysregulation of the rate of colonic crypt renewal lead to the development of CRC? We recently reported that the dynamic organization of cells in colonic epithelium is encoded by five biological rules [

1]. Our study showed that the organization of colonic tissue is encoded through temporal asymmetry of cell division whereby division of a mature parent cell produces two progeny cells with different temporal properties, a mature (cycling) cell and an immature (resting) cell. The precise timing, temporal order, and spatial direction of cell division provided a mechanism that explains how the organization of cells is dynamically maintained during tissue renewal. We surmised that these laws for the cellular organization of normal colonic epithelium might provide a means to understand how tissue disorganization occurs during cancer development. A clue came from another previous study on age-at-tumor diagnosis in FAP and sporadic CRC patients which indicated the mechanism for CRC development involves an autocatalytic polymerization reaction [

2]. A reaction is autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same reaction. In this view, the autocatalytic production of cells in tissue renewal may provide a mechanism that explains why colonic epithelium is self-sustaining. Hence, in our current study, we assumed that the colonic epithelium consists of a polymer of cells and investigated whether crypt renewal occurs via a cell polymerization process. Our study emerges from concepts on autocatalytic polymerization in engineering [

3], mathematics [

4], chemistry [

5], and tumor biology [

6]. In our thinking, autocatalytic cell polymerization is the mechanism that forms the epithelium which lines the colon and other hollow organs. To explore this mechanism, we modeled changes occurring

in vivo during adenoma development to quantify the kinetics of crypt renewal in colon tumorigenesis. We conjecture that: 1) Changes in the rate of crypt renewal correlate with phenotypic changes that occur during adenoma morphogenesis in FAP patients. 2) Altered kinetics of crypt renewal occur due to an auto-catalytic polymerization-based mechanism in CRC development.

We selected hereditary CRC to investigate because CRC development progresses along the lines of normal colon to pre-malignant adenomas to CRC, and because histologic data on familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and sporadic patients is quantitative [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. We have studied how the kinetics of dysregulated colonic crypt dynamics lead to stem cell overpopulation and colon tumorigenesis [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Indeed, it is widely accepted that CRC develops through an adenoma to carcinoma sequence in both FAP and sporadic CRCs [

18,

19] and that mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (

APC) gene are the key driver mutational events in the initiation and development of most (>85%) CRCs [

20].

Classic FAP patients develop 100s to 1000s of premalignant adenomas which demonstrates that

APC mutations drive tumor growth

in vivo. If FAP patients are left untreated, they have nearly a 100% risk of developing CRC. In FAP, germline

APC mutations are initiating event in adenoma morphogenesis, but loss of the 2

nd wild type-

APC allele occurs during progression to full adenoma formation [

21,

22]. Two hits at the

APC locus also occur as acquired mutations in the development of most sporadic CRCs [

23]. While in both FAP and sporadic cases, the sequence of genetic and pathological events in CRC development are well-characterized [

24], the kinetic mechanism that drives CRC initiation and progression is still not fully elucidated.

Herein, we took a three-pronged approach: 1) Use microscopic analysis of normal, FAP, and adenomatous crypts to study the change in distribution of different cell populations during adenoma morphogenesis in FAP patients; 2) Create a mathematical model for crypt renewal kinetics by simulating colon epithelium as a polymer of cells; and 3) Apply the model to simulate quantitative pulse-labeling data on colonic crypt labeling indices. Then we then determined if model output on tissue kinetic changes supports our hypothesis that changes in the rate of tissue renewal polymerization leads to epithelial expansion and tissue disorganization during adenoma histogenesis.

2. Methods

2.1. Microscopic Analysis of Ki67 Expression in FAP Colon Tissue Sections

Samples of normal human colon tissue were obtained from the distal margin of resection from individuals undergoing colon surgery, including, but not limited to, colon tumor resections. We investigated three types of tissues: (a) normal colonic crypts, (b) normal-appearing crypts from FAP patients, and (c) adenomatous crypts. The distribution of cycling cells in colonic tissues was illustrated by expression of the Ki67 marker for proliferating cells. Immunohistochemistry using 5-µm tissue sections was done as we previously reported [

25]. The primary antibody was anti-Ki-67, 1:100 (Immunotech, Westbrook, ME; Anti-Ki-67 mouse IgG1 Monoclonal Antibody, Unconjugated, Clone MIB-1, RRID:AB_86403). The study does not involve human participants in clinical trials, so randomization, inclusion and exclusion criteria, attrition, sex as a biological variable, age, weight, blinding, power analysis, replication, code information, data information, and protocol information were not part of the study. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of human colonic tissues were procured and obtained from our tissue procurement core facility. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to surgery. The use of human tissues was approved by Institutional Review Board of Christiana Care Health Services, Inc (FWA00006557). All tissue samples were de-identified and stripped of all direct identifiers so no information was available to identify the surgical patients from whom the tissue sections were derived. The patient tissue studies were conducted in accordance with the following ethical guidelines: Declaration of Helsinki, International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS), Belmont Report, and U.S. Common Rule.

2.2. Model Design for the Human Colonic Crypt

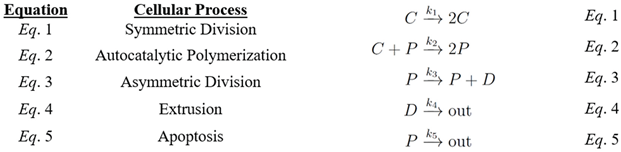

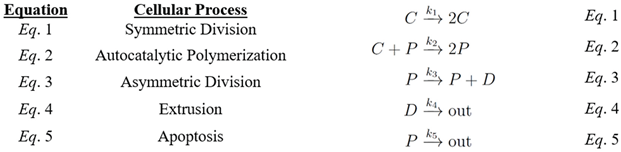

We created a mathematical model for the crypt by simulating colon epithelium as a polymer of cells. The model assumes that cell division produces cells that act as monomers that form polymers of cells (colon tissue) through an autocatalytic polymerization process. The model design contains a system of nonlinear differential equations that represent the changing dynamics of three cell populations (see below). The growth and death of all the cells is dictated by five equations.

In the model colonic crypt there are three main cell types, C represents cycling (actively dividing) cells, P represents proliferative (non-cycling, G0-like, quiescent) cells and D represents differentiated cells (unable to divide). The P and D cells make up the polymer of cells with P making up the clonogenic portion of the crypt lining and D filling up the rest of the polymer lining. The C cells exist in the crypt lining that divide symmetrically and daughter cells act like monomers that integrate into the polymer of cells through polymerization. Indeed, in colonic crypts, the biological self-renewal of stem cells continuously produces cells that act like monomers to form a polymer of cells (an interconnected, continuous cell sheet) in a polymerization-based process. Using the five equations above the rate of growth of each type of cell can be determined.

To be at equilibrium the values must be

The analysis of the system (Eqs. 6 – 8) shows that this is a stable equilibrium, and that a steady state is typically oscillatory as one would expect (see Supplemental Material #1).

3. Results

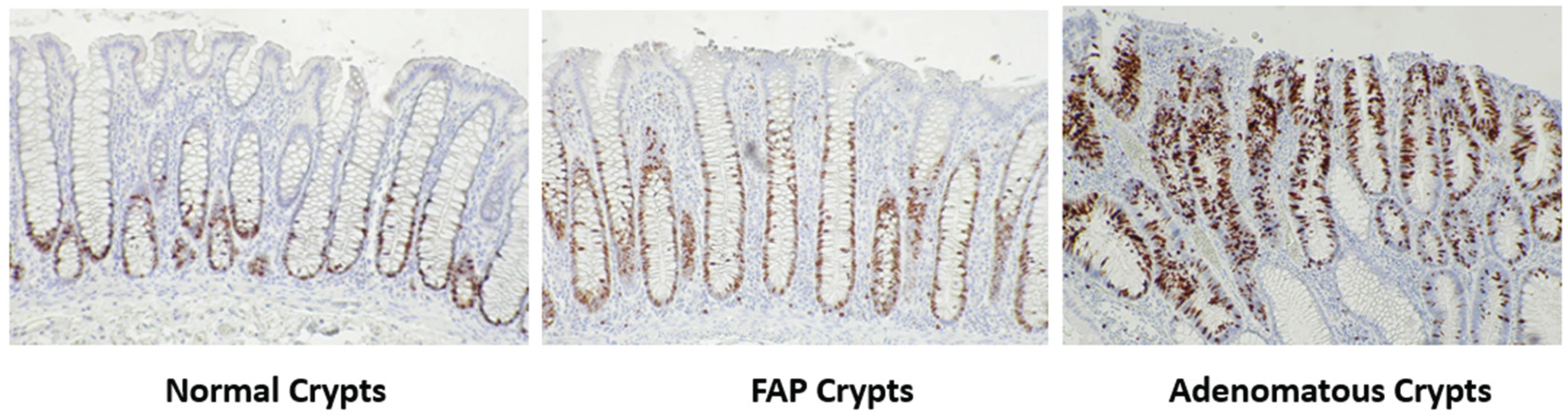

3.1. Staining for the Distribution of Cycling Cells in Normal and Neoplastic Colonic Crypts

To qualitatively illustrate how the distribution of cycling cells changes during colonic tumor development, we immuno-stained colon tissue sections for the expression of the Ki67 marker for proliferative cells. Note that Ki67 is expressed during most active phases of the cell cycle (G1, S, G2, M), but is absent in early G1 and G0 phase cells [

26].

Figure 1 shows results from Ki67 staining in normal colonic mucosa, normal-appearing colonic mucosa from FAP patients, and adenomas. In normal, FAP, adenomatous crypts, Ki67 staining shows that cycling cells are localized to the lower crypt, but absent at the bottom-most region of the crypt located next to the muscularis mucosa. During the progression from normal colon to normal-appearing FAP epithelium to adenoma, these positively Ki67 staining cell populations expanded and shifted upward along the crypt axis.

3.2. Quantitative Data on Labeling Indices

In our study, we used quantitative data derived from colonic crypt pulse-labeling indices (LIs) for model simulations (see Supplemental Material #2). These data were selected because they were derived from measurements on the uptake of [

3H] thymidine by cells in human colonic crypts which enables

in vivo pulse labeling of DNA-synthesizing S phase cells [7-10, 13]. Based on our analysis of these data, we were able to sub-classify crypt cells according to their temporal, kinetic phenotype, and to quantitatively map their distribution along the crypt axis. The proportion (fraction) of S phase (labeled) cells when plotted against cell position (level) along the crypt axis shows proliferative shifts in FAP crypts (normal-appearing and adenomatous) [

14,

15]. Our further computations (see Supplemental Material #2) give the distribution of: 1) Non-cycling differentiated (D) cells, 2) Non-cycling, G0-like, proliferative (P) cells, and 3) Cycling proliferative (C) cells in normal, FAP, and adenomatous crypts.

3.3. Model Output

We investigated the existence and stability of equilibrium solutions which were found analytically. The system has a first integral which shows that there is a neutrally stable equilibrium and that all other solutions oscillate around the equilibrium (Supplemental Material #1). Using Matlab, the system was solved numerically. The numerical solution confirms the predicted behavior of the system.

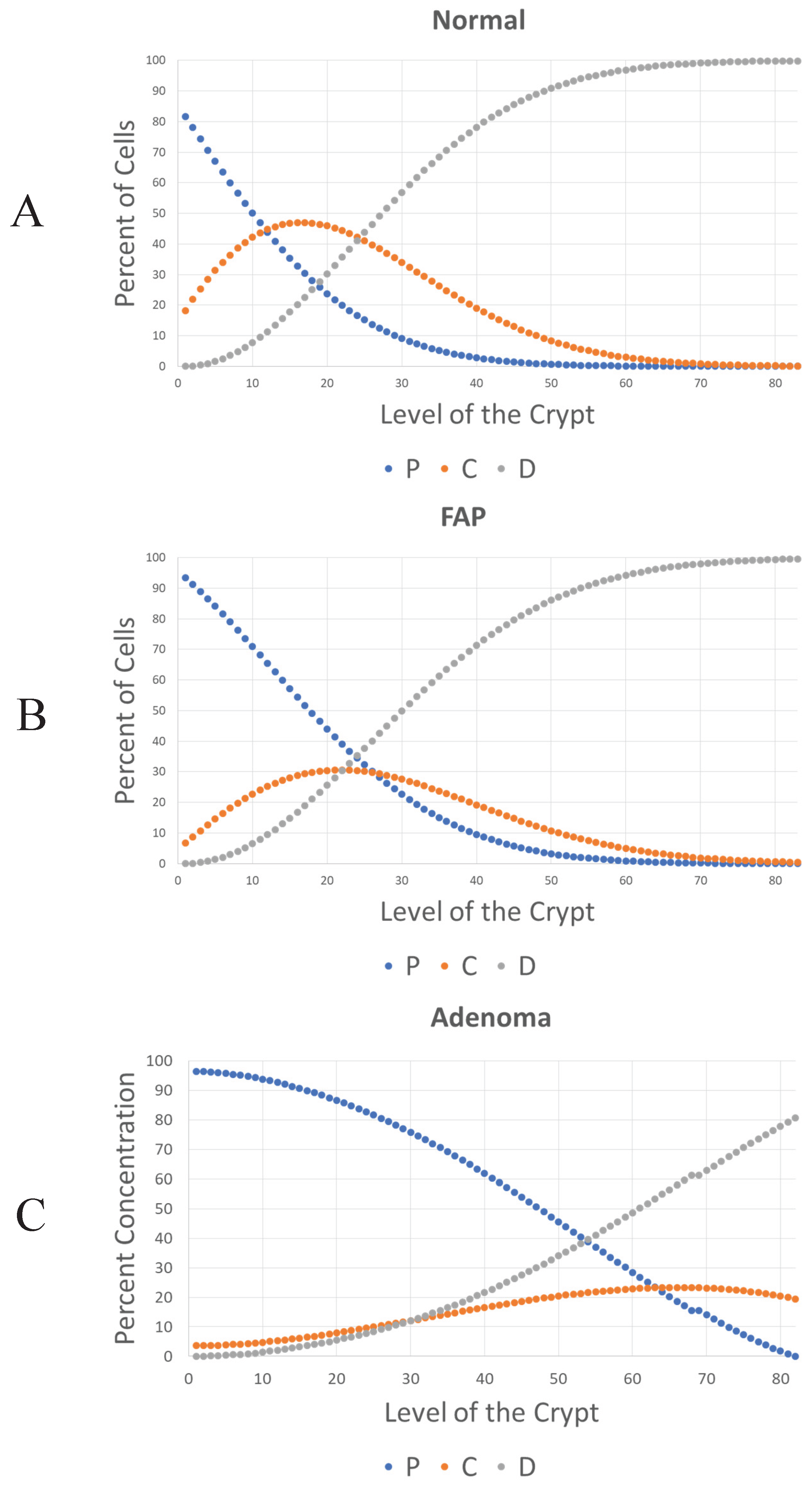

In equilibrium conditions, the percentage of each cell type can be expressed as a ratio of model rate constant values. To fit the parameters of the model, data on percentage of C, P and D cells in the colonic crypt (

Figure 2) was used. Specifically, by measuring the area under the curve (AUC) of C, P and D curves, in

Figure 2, and by assuming that

k1 is equal to one (i.e. time is measured in units of 1/

k1), it is possible to determine the value of each

k value at equilibrium based on

Eqs. 9–11.

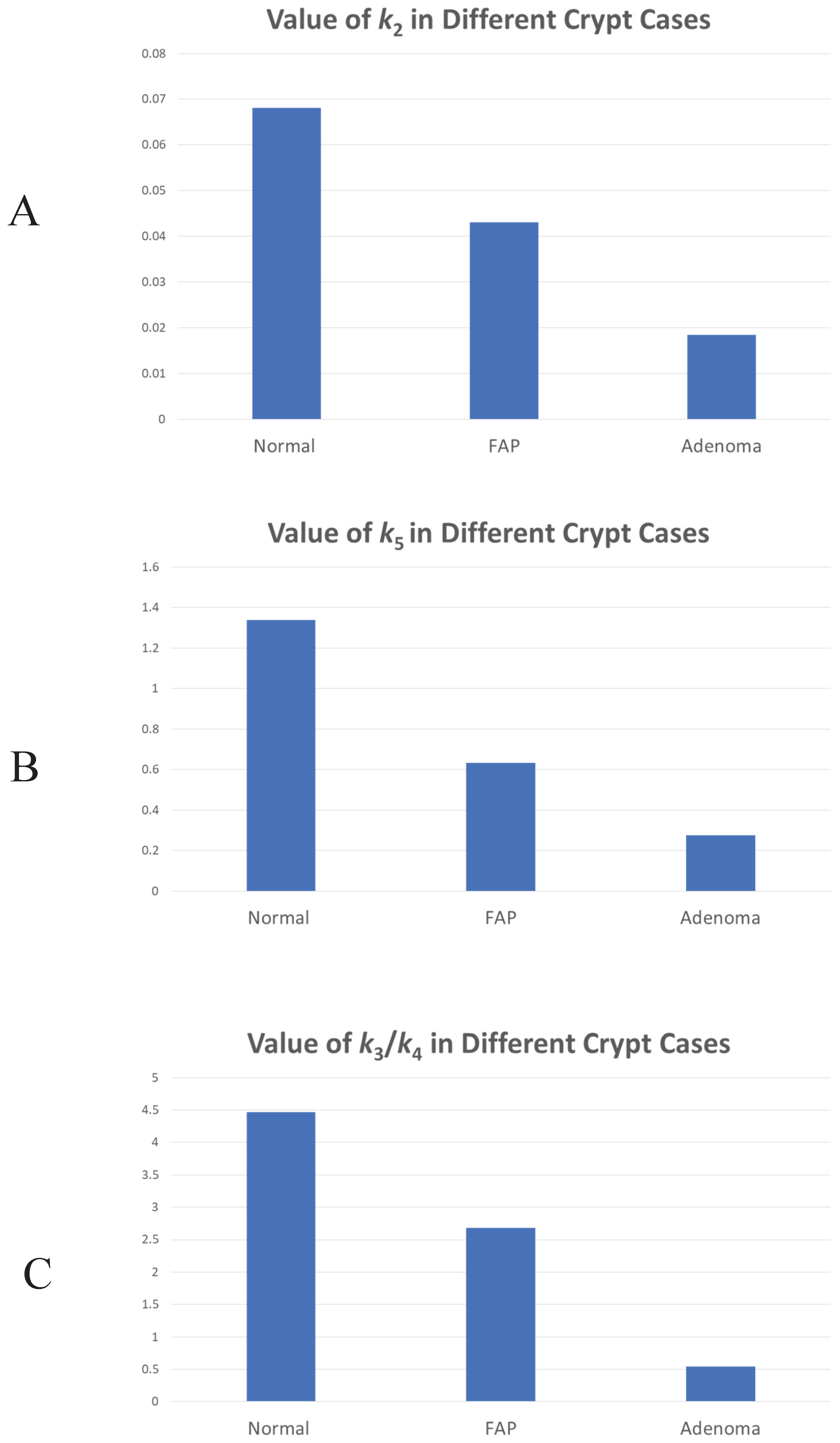

Figure 3 shows the changes in rate constant values (

k2,3,4,5) between normal, FAP and adenomatous crypts. Results show that FAP and dysplastic (adenomatous) colonic tissues have decreased values of

k2 (FAP crypts -1.6

X-fold; Adenomas -3.8

X-fold),

k5 (FAP crypts -2.6

X-fold; Adenomas -5.3

X-fold), and

k3/

k4 (FAP crypts -1.6

X-fold; Adenomas -8.8

X-fold) compared to normal tissues. The progressive decrease in

k2 and

k3/

k4 in normal-appearing and adenomatous crypts from FAP patients shows that the rate of auto-catalytic polymerization (see

Eqs. 2,3) becomes increasingly slower during adenoma morphogenesis.

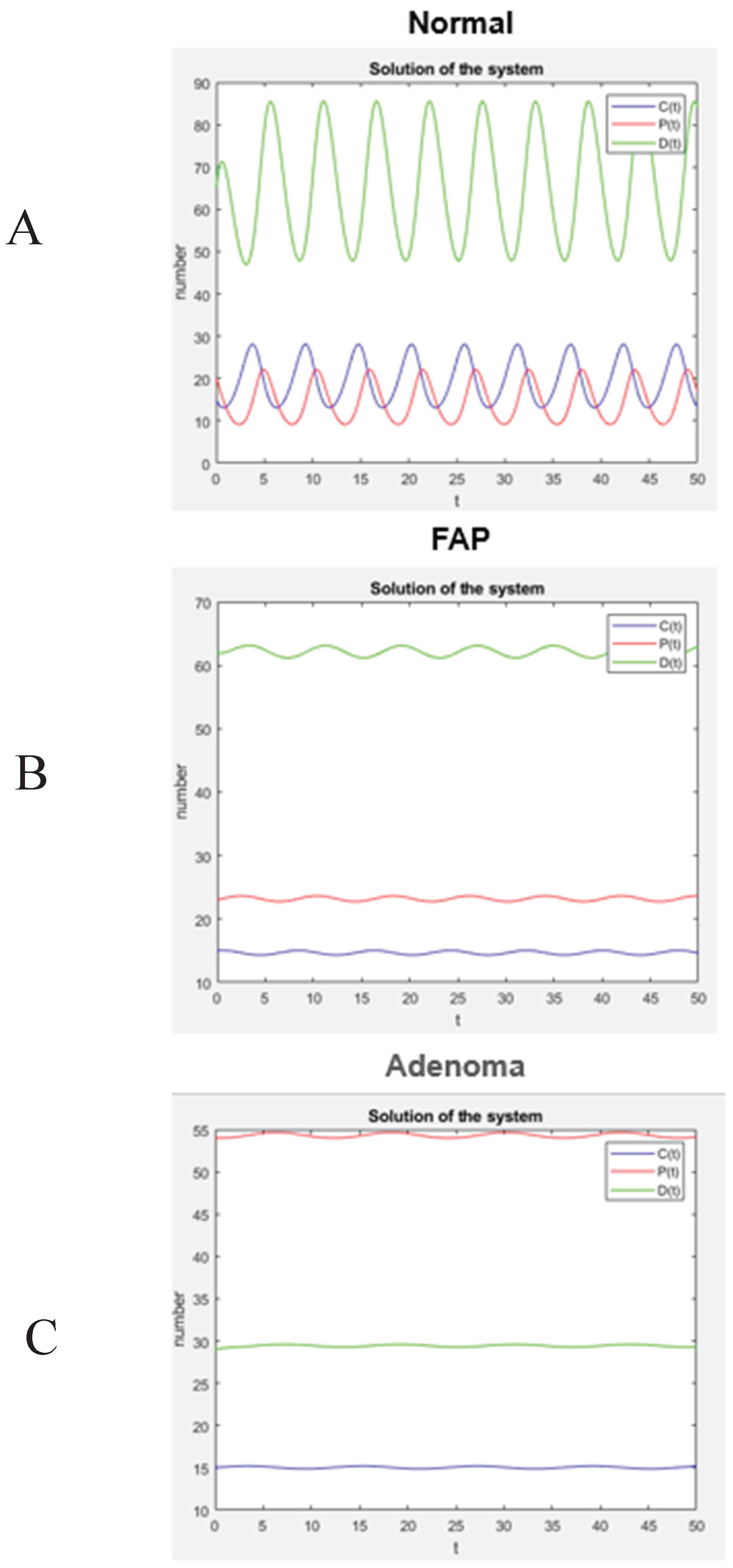

After the values of the rate constants were determined, a numerical computation was performed using Matlab, which reveals the dynamic behavior of the colon tissue systems according to the model. As shown in

Figure 4, the model system will have an oscillating but stable steady state. Specifically, these plots (

Figure 4A-4C) show changes in the number of C, P, and D cells at each level of normal, FAP, and adenomatous crypts. According to this model, the increased number of P cells in FAP crypts (+1.4X-fold) and adenomatous crypts (+1.1X-fold) and the decreased number of D cells in FAP crypts (-1.1X-fold) and adenomatous crypts (-2.3X-fold) is due to changes in the rate constants (

Figure 3). This finding indicates that the proportions of different cell populations progressively change in

APC-mutant crypts (see

Table 1) with a significant

increase in number of non-cycling proliferative cells and

decrease in number of differentiated cells.

4. Discussion

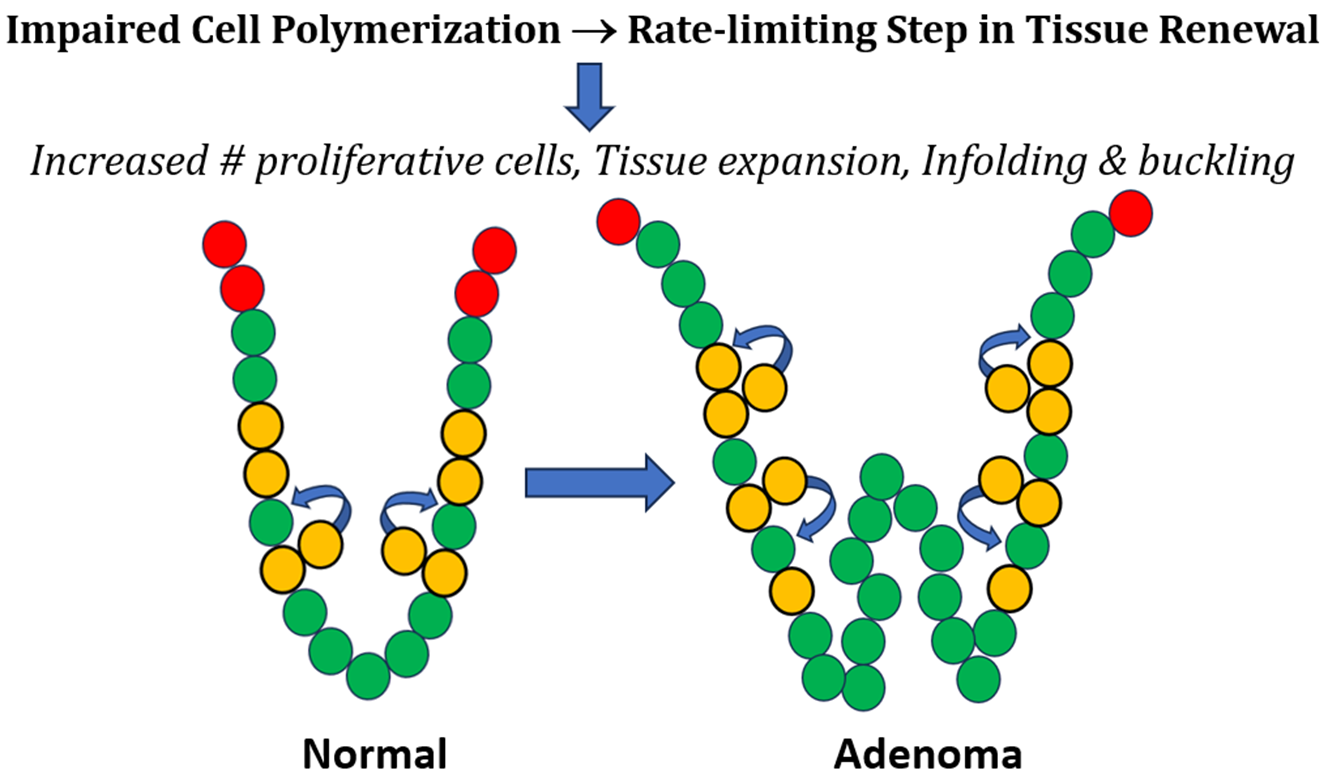

The main finding in our study is that premalignant colonic crypts have a slower rate of cell polymerization, which leads to an increase in percentage of proliferative cells and decrease in percentage of differentiated cells in

APC-mutant crypts. This discovery extends our previously reported findings that the dynamic organization of cells in colonic epithelium is encoded by five biological rules [

1] and that colon tumorigenesis may involve an autocatalytic tissue polymerization reaction [

2]. In comparison, the current study was designed to identify autocatalytic mechanisms at the tissue renewal level that lead to the development of colon cancer, which develops in colonic crypts that make up the intestine’s inner lining.

Accordingly, we created a mathematical model that considers the structure of colonic epithelium to be a polymer of cells and that colonic crypt renewal is autocatalytic. We then used the model to investigate changes in the proportion of different cell types occurring in adenoma development in familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Our analytical analysis showed that a positive equilibrium exists that is neutrally stable. Given a steady state, it was possible to determine the value of each kinetic rate constant k value at each reaction step in the model. Results show that FAP and adenomatous colonic tissues have decreased rate constant values (k2, k5, k3/k4) compared to normal tissues, indicating that the rate of auto-polymerization is slower in premalignant crypts. This slower rate of cell polymerization causes a rate-limiting step in the crypt renewal process that expands the non-cycling proliferative cell population size. These findings support our Hypothesis that changes in the rate of autocatalytic cell polymerization in colonic crypts lead to a larger cell polymer in relation to epithelial expansion during adenoma histogenesis. Indeed, the histogenesis of adenomas involves local expansion and infolding of colonic epithelium [27, 28]. This autocatalytic cell polymerization mechanism also explains how APC-mutation leads a prolonged rate of crypt renewal that drives the early development of CRC.

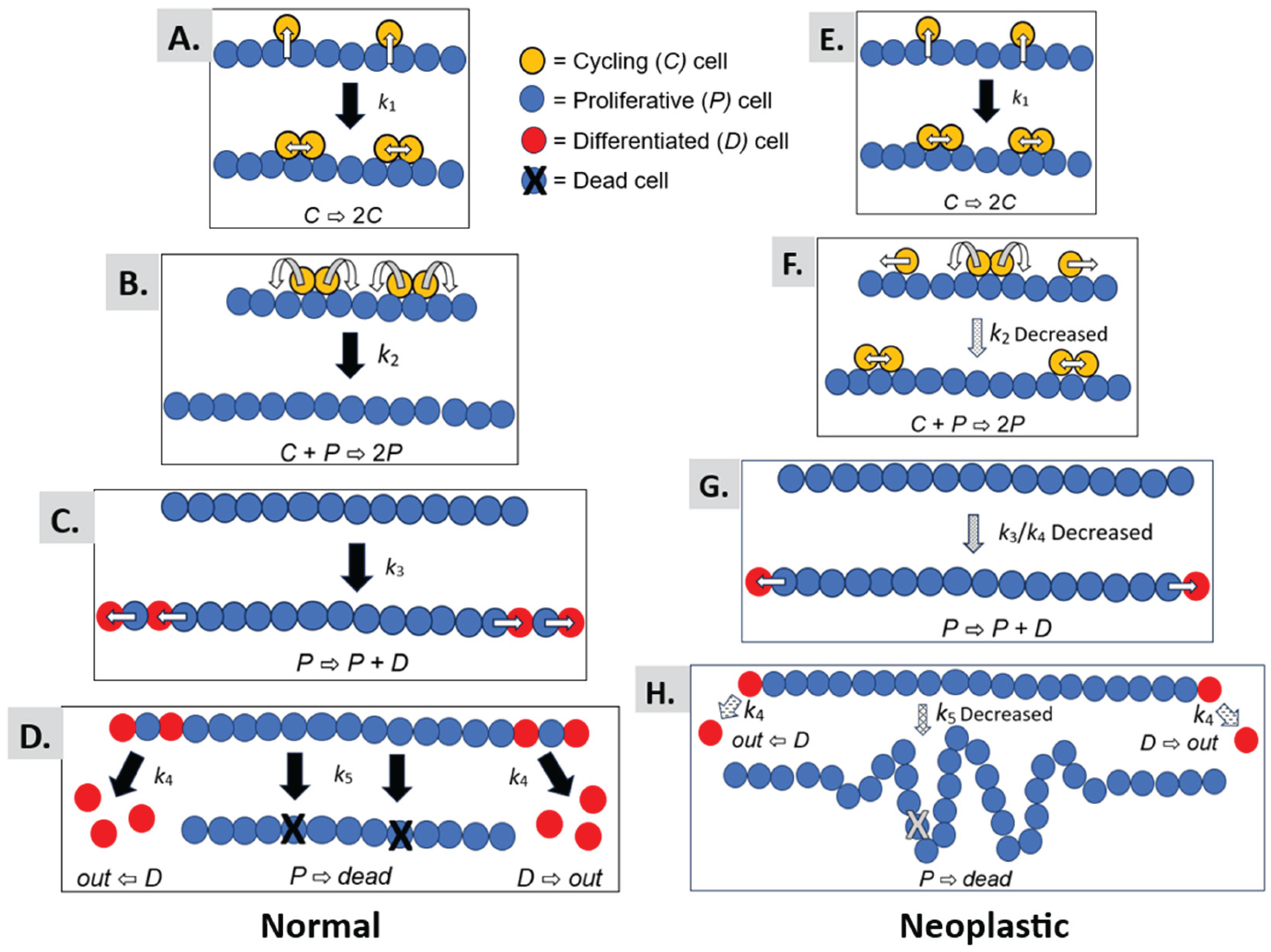

We provide a graphical illustration in

Figure 5 to help understand the mechanism that explains how autocatalytic polymerization drives colorectal cancer development. The autocatalytic polymerization dynamics are illustrated for normal (Panels A-D) and neoplastic epithelium (Panels E-H). Several points below warrant further discussion on what our modeling results mean for the mechanism of CRC development.

4.1. Autocatalytic Polymerization Kinetics

The autocatalytic dynamic occurs because in the process of symmetric cell division, the cells self-renew, and through the elevator process, the polymer catalyzes its own production. In normal epithelia, symmetric cell division occurs through a process termed “elevator movement” [29, 30]. In biology, the process of “elevator movement,” is highly specific and precisely regulated. Indeed, it involves the coordination of many cellular mechanisms such as the the orientation of mitosis in the intestine, retina, thyroid and brain [31-34]. It begins with detachment of mitotic cells from the basal lamina in prophase, which allows cells to rotate. The process ends with reattachment of the daughter cells to the basal lamina in late metaphase. During elevator movement, mitotic cells round up and precisely orient their mitotic spindle, rotate, and divide in a specific orientation. Then the daughter cells re-insert themselves into particular positions within the epithelium. Our model is designed to simulate the dynamics of this process as an autocatalytic reaction.

In our model, this process for symmetric cell division [35, 36] is assumed to occur in both normal epithelium (

Figure 5A) and neoplastic epithelium (

Figure 5E) as a reaction with rate constant

k1. The generation of a new daughter cell and reinsertion into the single cell epithelial monolayer simulates the polymerization process (

Figure 5B,F). That is, insertion of a daughter cell into the epithelial sheet is like the process of building a polymer via combination of monomers together to form a polymer. This reaction model for cell polymerization is regulated by the

k2 rate constant.

In our modeling, we found that the

k2 rate constant is decreased in FAP and adenomatous epithelia (

Figure 5F), which indicates that the rate of polymerization occurs more slowly in neoplastic epithelium. When the rate of polymerization is slowed down, it creates a rate-limiting step in the autocatalytic process. A slowed rate of autocatalytic polymerization could have two effects: (

i) A prolongation of the time for symmetric cell divisions that occur before the polymerization reaction. An extended “induction” period might increase the number of mitotic cells. Indeed, increased mitotic figures (mitotic index) is a pathological hallmark of many tumors; (

ii) A lengthening of the time for polymer growth. Extension of the time for polymer growth could lead to an increased cell polymer size and expanded epithelial sheet.

4.2. Cellular Differentiation Kinetics

Our model design also has a reaction with

k3 rate constant, for asymmetric cell division whereby a proliferative cell divides to produce a differentiated cell (

Figure 5C,G). Additionally, the model has a reaction with

k4 rate constant, for the extrusion of differentiated cells from the polymer (

Figure 5D,H). Our modeling of neoplastic epithelium shows that the

k3/

k4 ratio is decreased. In this case, a decreased

k3/

k4 ratio would cause an imbalance between asymmetric cell division and differentiated cell extrusion whereby the rate of asymmetric cell division becomes decreased relative to the rate of differentiated cell extrusion.

4.3. Cellular Apoptosis Kinetics

Finally, a reaction with

k5 rate constant, for programmed cell death (apoptosis) is also included in our model (

Figure 5D,H). For neoplastic epithelium, our modeling revealed that the

k5 rate constant is decreased indicating that the rate of apoptosis is reduced (see

Figure 5H). Taken together, a retarded rate of autocatalytic polymerization, a decreased ratio between asymmetric cell division and differentiated cell extrusion, and a decreased rate of apoptosis is predicted to cause local expansion of the epithelium that leads to infoldings of the single-layered cell epithelium. Progression of these dysregulated reactions provides a basis for tumor histogenesis.

5. Conclusions

Our Goal was to identify how CRC arises in the single-layered cell epithelium (simple columnar epithelium) that lines the luminal surface of the large intestine. Accordingly, we created a mathematical model that considers the structure of normal colonic epithelium to be a polymer of cells. In our model, an autocatalytic polymerization-like mechanism is the basis of colonic tissue renewal. We then applied our model to understand how tissue changes occur in premalignant APC-mutant colonic epithelium during early human CRC development. In modeling neoplastic epithelium, our findings here show that a decrease in the rate of autocatalytic cell polymerization causes a rate-limiting step that leads to a larger polymer size. In this view, a slower rate of cell polymerization increases the non-proliferative-proliferative cell population size and locally expands the colonic epithelium.

Thus, these findings support our

hypothesis that changes in the rate of tissue renewal polymerization leads to epithelial expansion and tissue disorganization during adenoma histogenesis.

Figure 5 illustrates how a prolonged rate of colonic tissue renewal, enlarged non-cycling proliferative cell population, and local epithelial tissue expansion leads to the infolding and buckling of colonic epithelium that occurs during adenoma histogenesis. Hence, our results provide a mechanism that explains how a tissue renewal-based polymerization mechanism drives colon tumorigenesis. Moreover, it is important to note that every tissue in the body has its specific tissue renewal time that controls the number and organization of cells in that organ [37, 38]. Since tissue renewal is such a fundamental process in biology [39, 40], the results from our study could significantly impact scientific understanding of how tumorigenesis occurs in the development of many cancer types.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This project was supported by a Drexel Student COOP Fellowship awarded to Ryan Boman by CATX Inc, Princeton NJ. Generous support was provided by the Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation for stem cell research (BMB), Carpenter Foundation, and Cawley Center for Translational Cancer Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

All data is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the late Dr. Olaf A. Runquist for valuable discussions and assistance with generation of new crypt data (Supplemental Materials #2). We also thank Dr. Tao Zhang for assistance with immunohistochemical staining. We thank Dr. Nicholas Petrelli for his ongoing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to claim.

References

- Boman BM, Dinh TN, Decker K, Emerick B, Modarai SR, Opdenaker LM, Fields JZ, Raymond C, Schleiniger G. Dynamic Organization of Cells in Colonic Epithelium is Encoded by Five Biological Rules. Biol Cell. 2025 Jul;117(7):e70017. [CrossRef]

- Boman BM, Guetter A, Boman RM, Runquist OA. Autocatalytic Tissue Polymerization Reaction Mechanism in Colorectal Cancer Development and Growth. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Feb 17;12(2):460. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Li B, Fu X, Zhao P, Zhao Y, Zhou W, Lu Y, Zheng Y. Autocatalytic Reaction Networks: A Pathway to Spatial Temporal Mastery in Dynamic Materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2024 Nov 27:e202415582. [CrossRef]

- Plasson R, Brandenburg A, Jullien L, Bersini H. Autocatalysis: at the root of self-replication. Artif Life. 2011 Summer;17(3):219-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.W. , Pearson R.G. Kinetics and Mechanism. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1981. p. 26.

- Decker F, Oriola D, Dalton B, Brugués J. Autocatalytic microtubule nucleation determines the size and mass of Xenopus laevis egg extract spindles. Elife. 2018 Jan 11;7:e31149. [CrossRef]

- Deschner EE, Lewis CM, Lipkin M. In vitro study of human epithelial cells: I. Atypical zone of H3-thymidine incorporation in mucosa of multiple polyposis. J Clin Invest 1963; 42: 1922–8.

- Bleiberg H, Mainguet P, Galand P. Cell renewal in familial polyposis. Comparison between polyps and adjacent healthy mucosa. Gastroenterology 1972; 63: 240–5.

- Iwana T, Utsunomiya J, Sasaki J. Epithelial cell kinetics in the crypts of familial polyposis of the colon. Jpn J Surg 1977; 7: 230–4.

- Lipkin M, Blattner WE, Fraumeni JF, Lynch HT, Deschner E, Winawer S. Tritiated thymidine labeling distribution as a marker for hereditary predisposition to colon cancer. Cancer Res 1983; 43: 1899–904.

- Potten CS, Kellett M, Roberts SA, Rew DA, Wilson GD. Measurement of in vivo proliferation in human colorectal mucosa using bromodeoxyuridine. Gut. 1992 Jan;33(1):71-8. [CrossRef]

- Potten CS, Kellett M, Rew DA, Roberts SA. Proliferation in human gastrointestinal epithelium using bromodeoxyuridine in vivo: data for different sites, proximity to a tumour, and polyposis coli. Gut. 1992 Apr;33(4):524-9. [CrossRef]

- Lightdale C, Lipkin M, Deschner E. In vivo measurements in familial polyposis: kinetics and location of proliferating cells in colonic adenomas. Cancer Res. 1982 Oct;42(10):4280-3. [PubMed]

- Boman BM, Fields JZ, Bonham-Carter O, Runquist OA. Computer modeling implicates stem cell overproduction in colon cancer initiation. Cancer Res. 2001 Dec 1;61(23):8408-11. [PubMed]

- Boman BM, Fields JZ, Cavanaugh KL, Guetter A, Runquist OA. How dysregulated colonic crypt dynamics cause stem cell overpopulation and initiate colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2008 ;68(9):3304-13. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- Runquist OA, Mazac R, Roerig J, Boman BM. Latent time (quiescence) properties of human colonic crypt cells: Mechanistic relationships to colon cancer development. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2017, 1, 1156–1164.

- Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Appelman H, Fields JZ, Wicha MS, Boman BM. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 15;69(8):3382-9. [CrossRef]

- Morson, B. President's address. The polyp-cancer sequence in the large bowel. Proc R Soc Med. 1974 Jun;67(6 Pt 1):451-7. PMCID: PMC1645739. [PubMed]

- Leslie A, Carey FA, Pratt NR, Steele RJ. The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Br J Surg. 2002 Jul;89(7):845-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2010, 487, 330–337.

- Levy DB, Smith KJ, Beazer-Barclay Y, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Inactivation of both APC alleles in human and mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1994 Nov 15;54(22):5953-8. [PubMed]

- Ichii S, Horii A, Nakatsuru S, Furuyama J, Utsunomiya J, Nakamura Y. Inactivation of both APC alleles in an early stage of colon adenomas in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Hum Mol Genet. 1992 Sep;1(6):387-90. [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.M.; Zilz, N.; Beazer-Barclay, Y.; Bryan, T.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 1992, 359, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990 Jun 1;61(5):759-67. [CrossRef]

- Boman BM, Walters R, Fields JZ, Kovatich AJ, Zhang T, Isenberg GA, Goldstein SD, Palazzo JP. Colonic crypt changes during adenoma development in familial adenomatous polyposis: immunohistochemical evidence for expansion of the crypt base cell population. Am J Pathol. 2004 Nov;165(5):1489-98. [CrossRef]

- Uxa S, Castillo-Binder P, Kohler R, Stangner K, Müller GA, Engeland K. Ki-67 gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2021 Dec;28(12):3357-3370. [CrossRef]

- Wong WM, Mandir N, Goodlad RA, Wong BC, Garcia SB, Lam SK, Wright NA. Histogenesis of human colorectal adenomas and hyperplastic polyps: the role of cell proliferation and crypt fission. Gut. 2002 Feb;50(2):212-7. [CrossRef]

- Maskens, AP. Histogenesis of adenomatous polyps in the human large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1979 Dec;77(6):1245-51. [PubMed]

- Fujita, S. The discovery of the matrix cell, the identification of the multipotent neural stem cell and the development of the central nervous system. Cell Struct Funct. 2003 Aug;28(4):205-28. [CrossRef]

- Woods DF, Bryant PJ. Apical junctions and cell signalling in epithelia. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1993;17:171-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potten CS, Roberts SA, Chwalinski S, Loeffler M, Paulus U (1988) Scoring mitotic activity in longitudinal sections of crypts of the small intestine. Cell Tissue Kinet.

- Jinguji Y & Ishikawa H (1992) Electron microscopic observations on the maintenance of the tight junction during cell division in the epithelium of the mouse small intestine. Cell Struct Funct.

- Saito K, Kawaguchi A, Kashiwagi S, Yasugi S, Ogawa M, Miyata T (2003) Morphological asymmetry in dividing retinal progenitor cells. Dev Growth Differ.

- Fujita S (2014) 50 years of research on the phenomena and epigenetic mechanism of neurogenesis. Neurosci Res.

- Boman BM, Wicha MS, Fields JZ, Runquist OA. Symmetric division of cancer stem cells--a key mechanism in tumor growth that should be targeted in future therapeutic approaches. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Jun;81(6):893-8. [CrossRef]

- Spradling A, Drummond-Barbosa D, Kai T. Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 2001 Nov 1;414(6859):98-104. [CrossRef]

- Milo R & Phillips R (2015) Cell Biology by the Numbers (Garland Science, New York, NY) pp 278-282.

- Sender R, Milo R. The distribution of cellular turnover in the human body. Nat Med. 2021 Jan;27(1):45-48. [CrossRef]

- Boman BM (2025) How Does Multicellular Life Happen? [CrossRef]

- Frank, SA. Stem cells: Tissue renewal, In Dynamics of Cancer: Incidence, Inheritance, and Evolution. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 2007. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1568. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).