Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

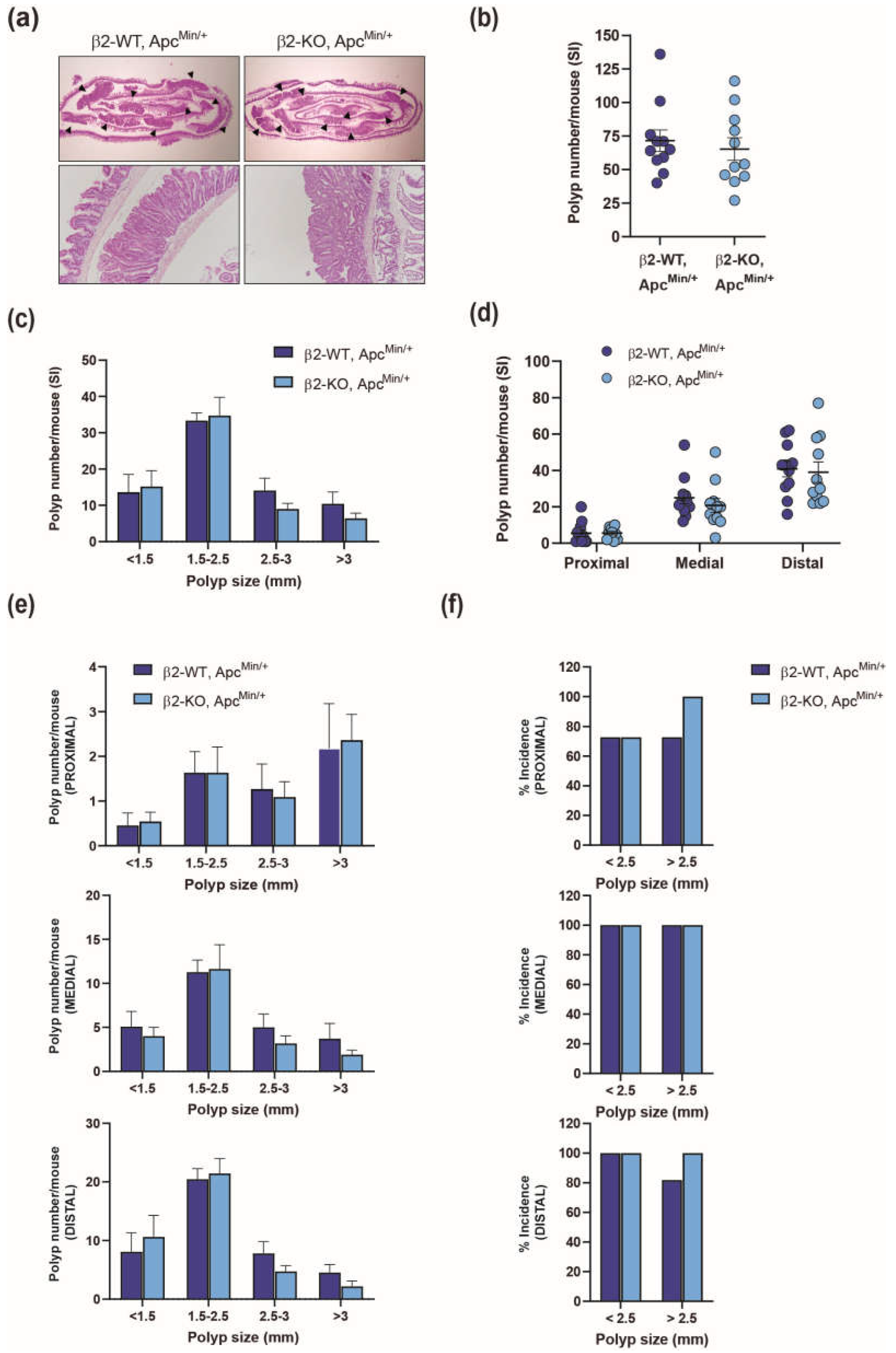

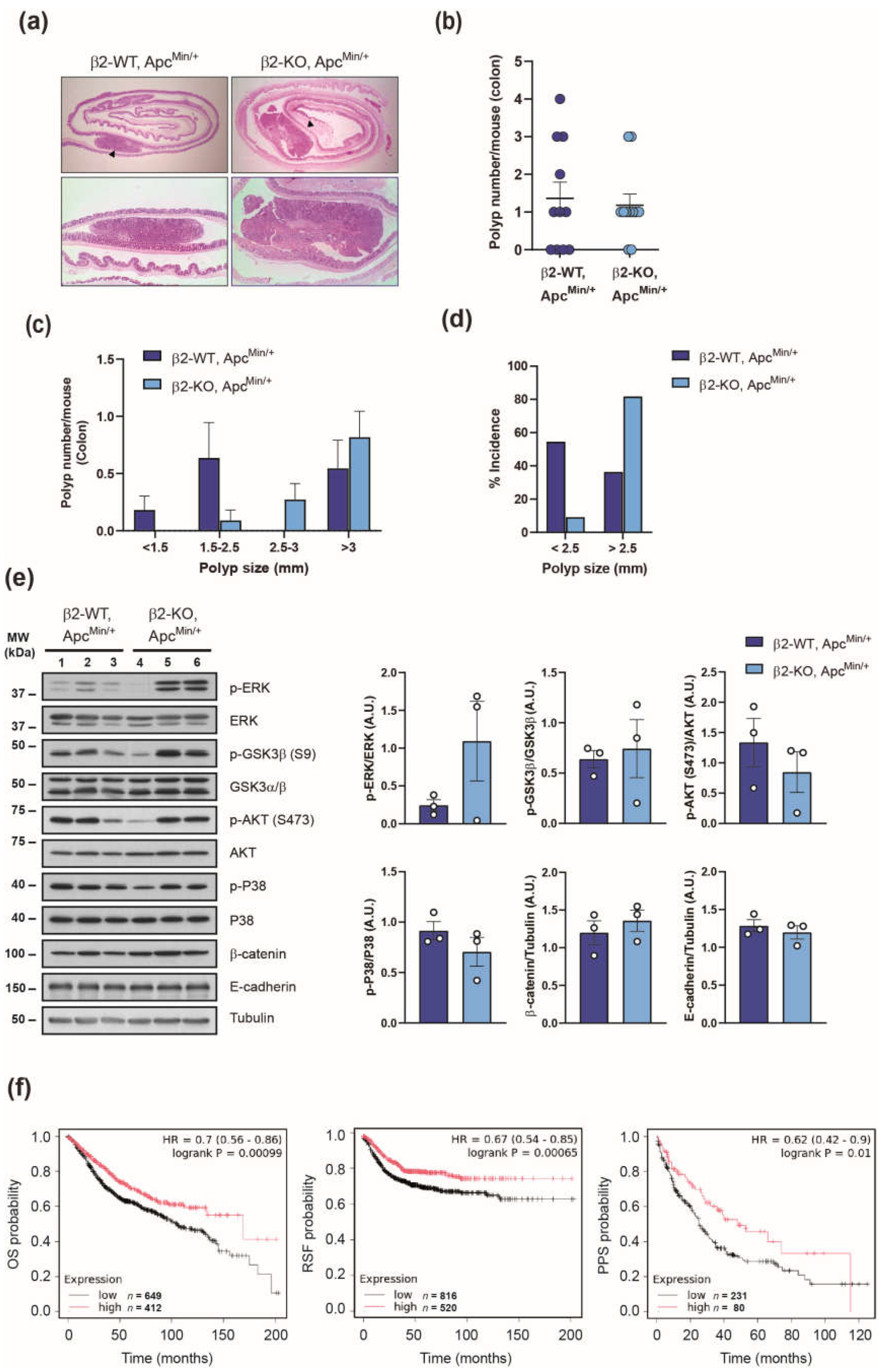

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice

4.2. Mouse Intestinal Tumor Analysis

4.3. Western Blot Assay

4.4. Clinical Dataset Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Fearon, E.R.; Vogelstein, B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990, 61, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 1996, 87, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakis, P. Wnt signaling in cancer. Cold Spring Har Perspec Biol 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, S.D.; Bertagnolli, M.M. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leve, F.; Morgado-Díaz, J.A. Rho GTPase signaling in the development of colorectal cancer. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2012, 113, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. Rho family GTPases. Bioch Soc Trans 2012, 40, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, R.B.; Ridley, A.J. Rho GTPases: Regulation and roles in cancer cell biology. Small GTPases 2016, 7, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, S.; Wang, P.; Yang, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M. Prognostic and Clinicopathological Value of Rac1 in Cancer Survival: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Journal of Cancer 2018, 9, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Del Pulgar, T. Valdés-Mora, F., Bandrés, E., Pérez-Palacios, R., Espina, C., Cejas, P., García-Cabezas, M. A., Nistal, M., Casado, E., González-Barón, M., García-Foncillas, J., & Lacal, J. C. Cdc42 is highly expressed in colorectal adenocarcinoma and downregulates ID4 through an epigenetic mechanism. Int J Oncol. 2008, 33, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakamori, R. Yu, S., Zhang, X., Hoffman, A., Sun, J., Das, S., Vedula, P., Li, G., Fu, J., Walker, F., Yang, C. S., Yi, Z., Hsu, W., Yu, D. H., Shen, L., Rodriguez, A. J., Taketo, M. M., Bonder, E. M., Verzi, M. P., & Gao, N. CDC42 Inhibition Suppresses Progression of Incipient Intestinal Tumors. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 5480–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango, D. Laiho, P., Kokko, A., Alhopuro, P., Sammalkorpi, H., Salovaara, R., Nicorici, D., Hautaniemi, S., Alazzouzi, H., Mecklin, J. P., Järvinen, H., Hemminki, A., Astola, J., Schwartz, S., Jr, & Aaltonen, L. A. Gene-Expression Profiling Predicts Recurrence in Dukes’ C Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P. Macaya, I., Bazzocco, S., Mazzolini, R., Andretta, E., Dopeso, H., Mateo-Lozano, S., Bilić, J., Cartón-García, F., Nieto, R., Suárez-López, L., Afonso, E., Landolfi, S., Hernandez-Losa, J., Kobayashi, K., Ramón y Cajal, S., Tabernero, J., Tebbutt, N. C., Mariadason, J. M., Schwartz, S., Jr, Arango, D. RHOA inactivation enhances Wnt signalling and promotes colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Yoon, S.R.; Lim, J.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, H.G. Dysregulation of Rho GTPases in Human Cancers. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanietz, M.G.; Caloca, M.J. The Rac GTPase in Cancer: From Old Concepts to New Paradigms. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 5445–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfils, J.; Zeghouf, M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 269–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njei, L.P.; Sampaio Moura, N.; Schledwitz, A.; Griffiths, K.; Cheng, K.; Raufman, J.P. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors and colon neoplasia. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024, 12, 1489321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Tsuji, S.; Muroya, K.; Furukawa, S.; Shibata, Y.; Okuno, M.; Ohwada, S.; Akiyama, T. The adenomatous polyposis coli-associated exchange factors Asef and Asef2 are required for adenoma formation in Apc(Min/+)mice. EMBO Rep 2009, 10, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, K.A.; Gilroy, K.; Cassidy, J.W.; Fey, S.K.; Najumudeen, A.K.; Zeiger, L.B.; Vincent, D.F.; Gay, D.M.; Johansson, J.; Fordham, R.P.; et al. A RAC-GEF network critical for early intestinal tumourigenesis. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreider-Letterman, G.; Carr, N.M.; Garcia-Mata, R. Fixing the GAP: The role of RhoGAPs in cancer. Eur J Cell Biol 2022, 101, 151209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeldia-Brenner, L.; Gutierrez-Uzquiza, A.; Barrio-Real, L.; Wang, H.; Kazanietz, M.G.; Leskow, F.C. β3-chimaerin, a novel member of the chimaerin Rac-GAP family. Mol Biol Rep 2014, 41, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Medrano, V.; Barrio-Real, L.; Gutiérrez-Miranda, L.; González-Sarmiento, R.; Velasco, E.A.; Kazanietz, M.G.; Caloca, M.J. Identification of a truncated β1-chimaerin variant that inactivates nuclear Rac1. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, T.; How, B.E.; Manser, E.; Lim, L. Cerebellar beta 2-chimaerin, a GTPase-activating protein for p21 ras-related rac is specifically expressed in granule cells and has a unique N-terminal SH2 domain. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 12888–12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruinsma, S.P.; Cagan, R.L.; Baranski, T.J. Chimaerin and Rac regulate cell number, adherens junctions, and ERK MAP kinase signaling in the Drosophila eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104, 7098–7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, M.; Kato, S.; Fukushima, S.; Kaneyuki, U.; Fujii, T.; Kazanietz, M.G.; Oshima, K.; Shigemori, M. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle proliferation and migration by beta2-chimaerin, a non-protein kinase C phorbol ester receptor. Int J Mol Med 2006, 17, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Medrano, V.; Barrio-Real, L.; García-Rostán, G.; Baumann, M.; Rocks, O.; Caloca, M.J. A new role of the Rac-GAP β2-chimaerin in cell adhesion reveals opposite functions in breast cancer initiation and tumor progression. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28301–28319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Leskow, F.C.; Weaver, V.M.; Kazanietz, M.G. Rac-GAP-dependent inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation by beta2-chimerin. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 24363–24370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloca, M.J.; Delgado, P.; Alarcón, B.; Bustelo, X.R. Role of chimaerins, a group of Rac-specific GTPase activating proteins, in T-cell receptor signaling. Cell Signal 2008, 20, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Carmona, C.A.; Zini, P.; Velasco-Sampedro, E.A.; Cózar-Castellano, I.; Perdomo, G.; Caloca, M.J. β2-Chimaerin, a GTPase-Activating Protein for Rac1, Is a Novel Regulator of Hepatic Insulin Signaling and Glucose Metabolism. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Miller, D.W.; Barnett, G.H.; Hahn, J.F.; Williams, B.R. Identification and characterization of human beta 2-chimaerin: association with malignant transformation in astrocytoma. Cancer Res 1995, 55, 3456–3461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Du, F.; Huang, H.; Yuan, C.; Fu, J.; Sun, S.; Tian, T.; Liu, X.; Sun, H.; et al. A panel of differentially methylated regions enable prognosis prediction for colorectal cancer. Genomics 2021, 113, 3285–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, M. A. McArt, D. G., Kelly, P., Fuchs, M. A., Alderdice, M., McCabe, C. M., Bingham, V., McGready, C., Tripathi, S., Emmert-Streib, F., Loughrey, M. B., McQuaid, S., Maxwell, P., Hamilton, P. W., Turkington, R., James, J. A., Wilson, R. H., & Salto-Tellez, M. Comprehensive molecular pathology analysis of small bowel adenocarcinoma reveals novel targets with potential for clinical utility. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 20863–20874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodde, R.; Edelmann, W.; Yang, K.; van Leeuwen, C.; Carlson, C.; Renault, B.; Breukel, C.; Alt, E.; Lipkin, M.; Khan, P.M.; Kucherlapati, R. A targeted chain-termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994, 91, 8969–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.R.; Pitot, H.C.; Dove, W.F. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science 1990, 247, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Győrffy, B. Integrated analysis of public datasets for the discovery and validation of survival-associated genes in solid tumors. Innovation 2024, 5, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Lemmon, M.A.; Kazanietz, M.G. Essential role for Rac in heregulin beta1 mitogenic signaling: a mechanism that involves epidermal growth factor receptor and is independent of ErbB4. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Klein, E.A.; Assoian, R.K.; Kazanietz, M.G. Heregulin beta1 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation through Rac/ERK-dependent induction of cyclin D1 and p21Cip1. Biochem J 2008, 410, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espina, C.; Céspedes, M.V.; García-Cabezas, M.A.; Gómez del Pulgar, M.T.; Boluda, A.; Oroz, L.G.; Benitah, S.A.; Cejas, P.; Nistal, M.; Mangues, R.; Lacal, J. C. A critical role for Rac1 in tumor progression of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Am J Pathol 2008, 172, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myant, Kevin B.; Cammareri, P.; McGhee, Ewan J.; Ridgway, Rachel A.; Huels, David J.; Cordero, Julia B.; Schwitalla, S.; Kalna, G.; Ogg, E.-L.; Athineos, D.; D., Timpson, P., Vidal, M., Murray, G. I., Greten, F. R., Anderson, K. I., & Sansom, O. J. ROS Production and NF-κB Activation Triggered by RAC1 Facilitate WNT-Driven Intestinal Stem Cell Proliferation and Colorectal Cancer Initiation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 761-773. [CrossRef]

- Malliri, A.; Rygiel, T.P.; van der Kammen, R.A.; Song, J.-Y.; Engers, R.; Hurlstone, A.F.L.; Clevers, H.; Collard, J.G. The Rac Activator Tiam1 Is a Wnt-responsive Gene That Modifies Intestinal Tumor Development. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.E.; Hunt, D.H.; Javid, S.H.; Redston, M.; Carothers, A.M.; Bertagnolli, M.M. Apc deficiency is associated with increased Egfr activity in the intestinal enterocytes and adenomas of C57BL/6J-Min/+ mice. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 43261–43272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, R.; Yang, M.; Pflieger, L.; Schell, M.J.; Rajan, M.; Davis, T.B.; Wang, H.; Presson, A.; Pledger, W.J.; Yeatman, T.J. APC and TP53 Mutations Predict Cetuximab Sensitivity across Consensus Molecular Subtypes. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, C.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Iglesias, M.; Fernández-Masip, J.L.; Vivancos, A.; Whissell, G.; Humà, M.; Peiró, N.; Gallego, L.; Jonkheer, S.; Davy, A. Lloreta, J., Sancho, E., & Batlle, E. EphB-ephrin-B interactions suppress colorectal cancer progression by compartmentalizing tumor cells. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, N.; Caloca, M.J.; Prendergast, G.V.; Meinkoth, J.L.; Kazanietz, M.G. Atypical protein kinase C-zeta stimulates thyrotropin-independent proliferation in rat thyroid cells. Endocrinol 2000, 141, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).