Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

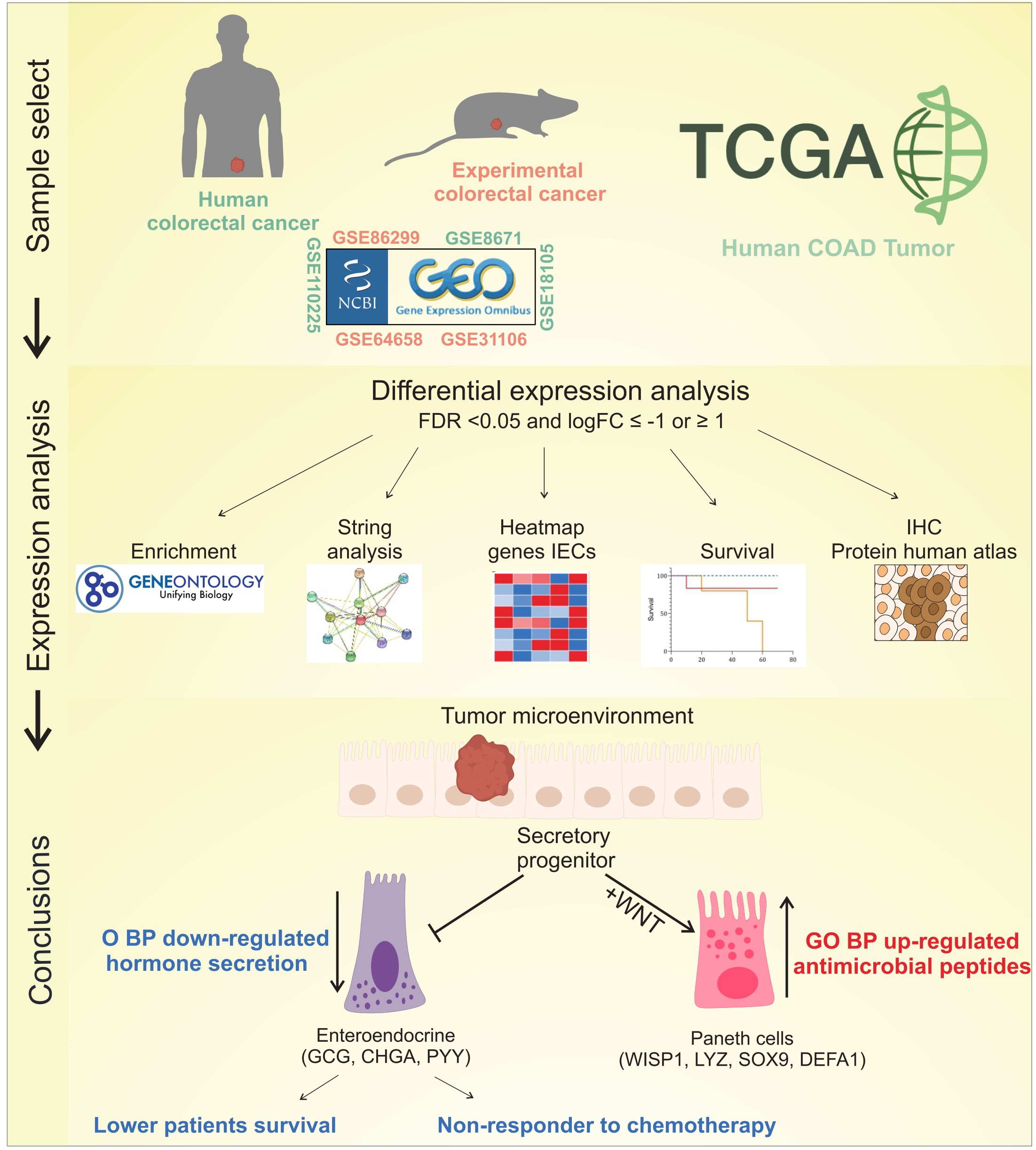

1. Introduction

2. Results

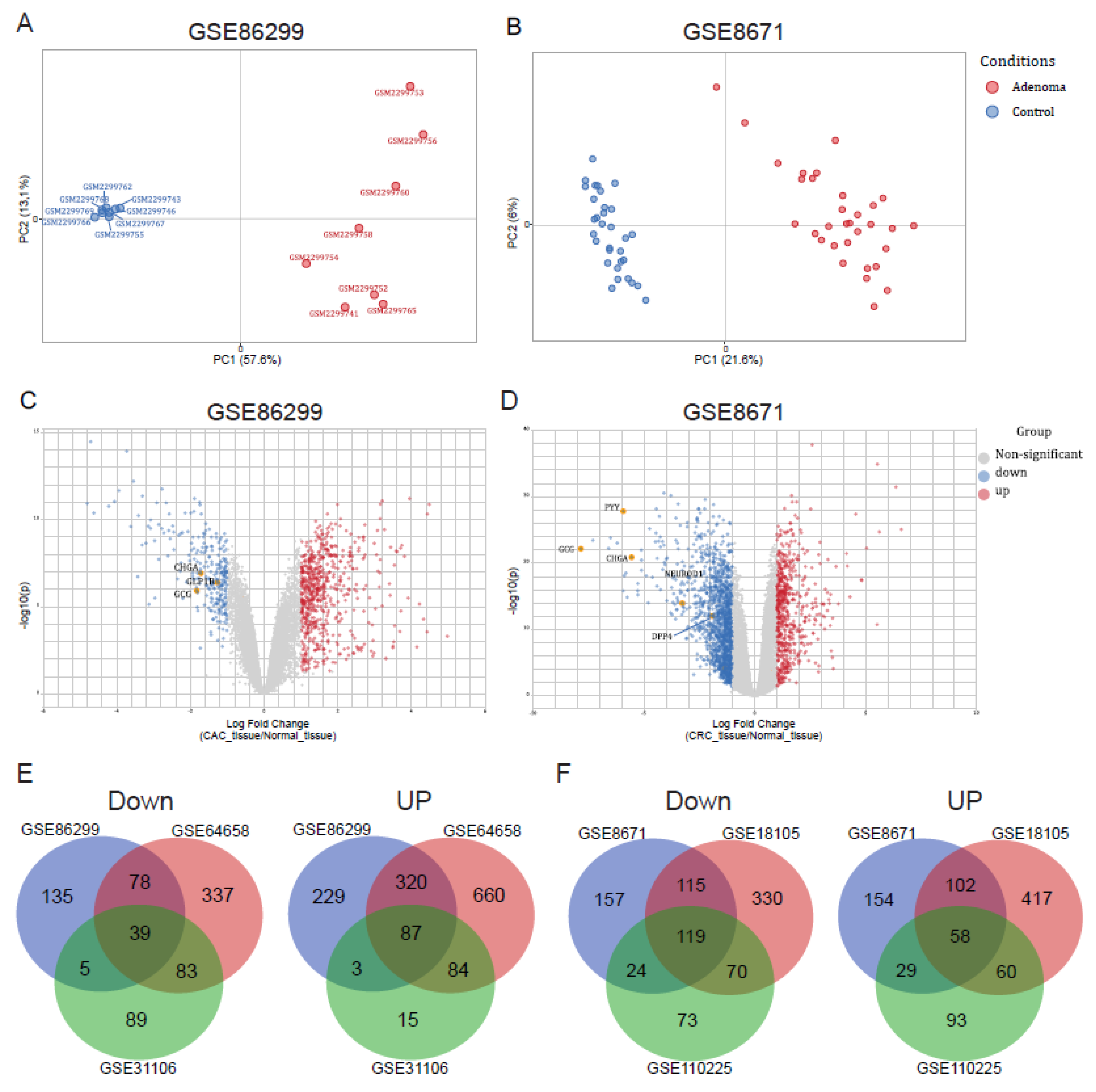

2.1. Differential Expression of IECs Markers in CRC

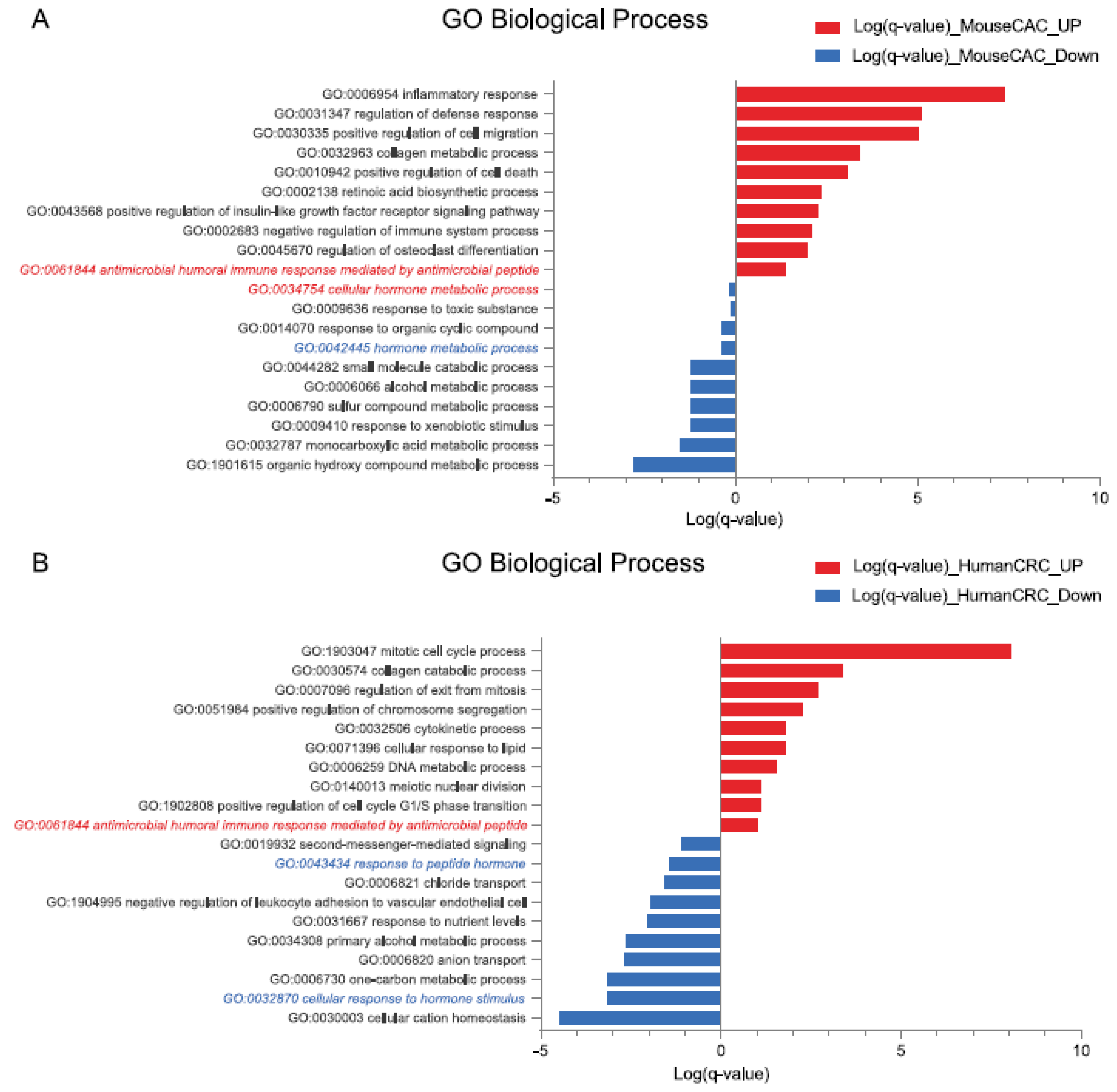

2.2. Antimicrobial Peptide-Related Pathways Are Upregulated While Hormonal Processes Are Downregulated in Colorectal Cancer

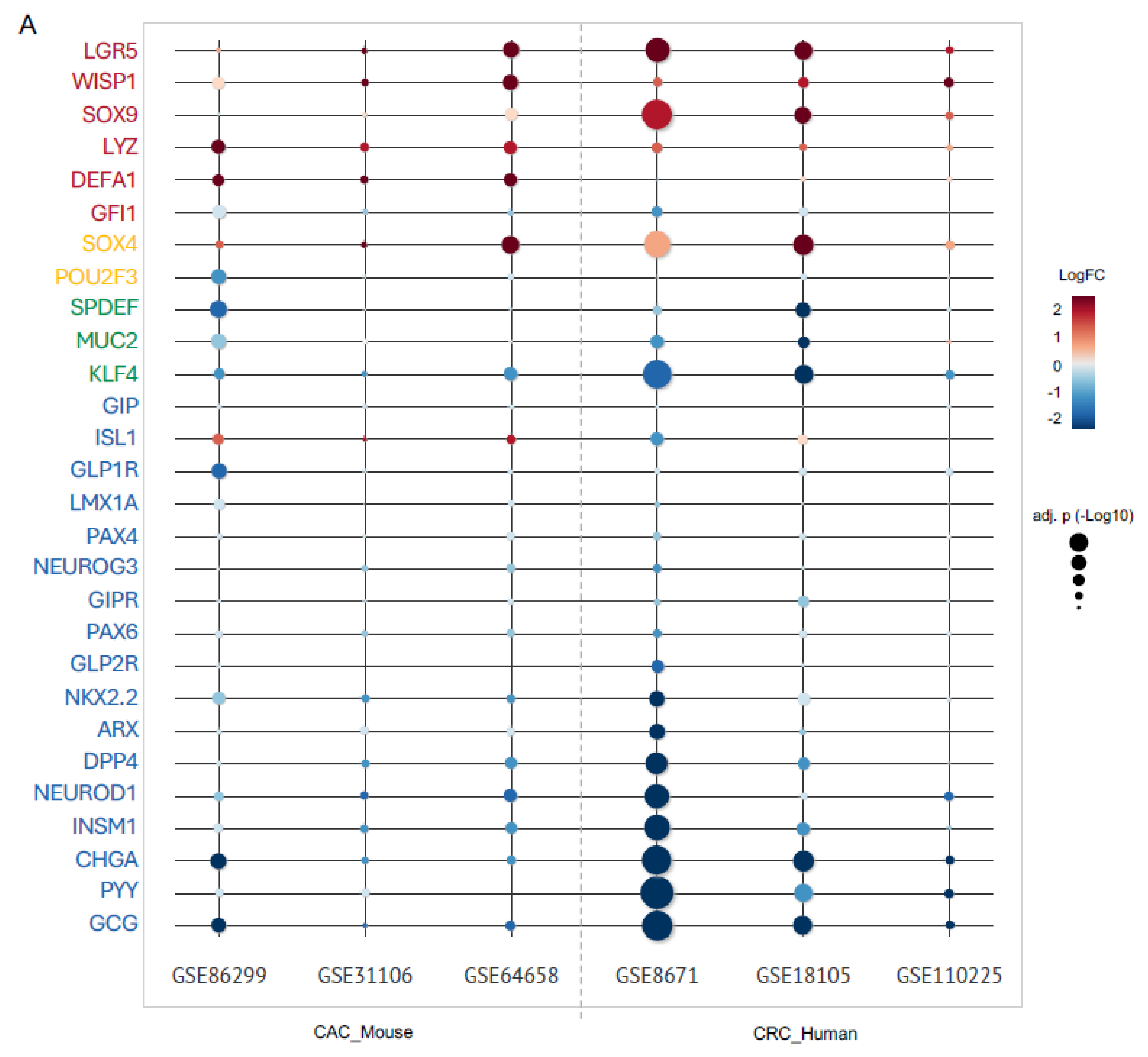

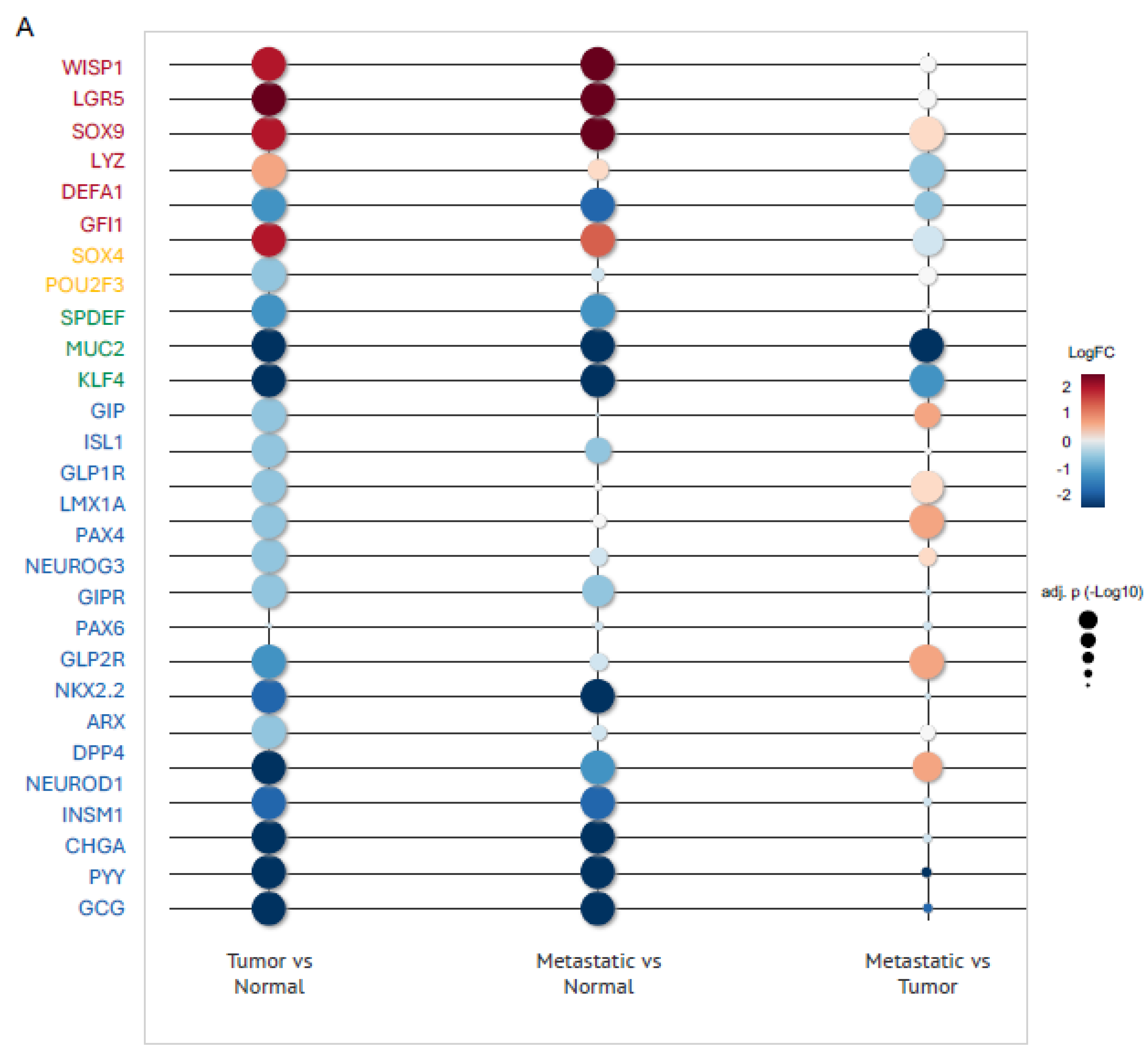

2.3. Upregulation of Paneth Cell-Related Markers and Downregulation of Enteroendocrine Cell Genes Is a Conserved Phenomenon Regardless the Origin of Colon Tumor

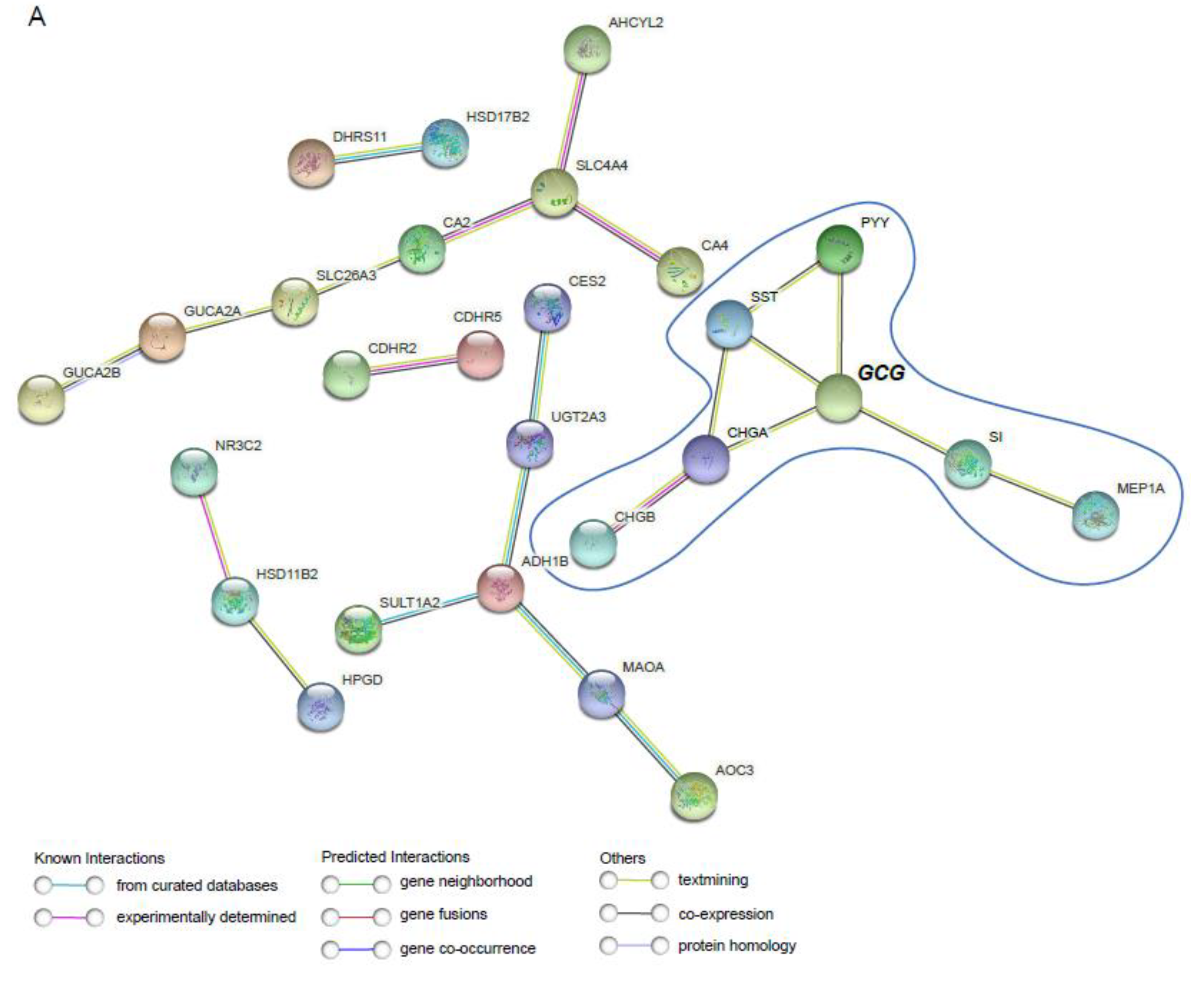

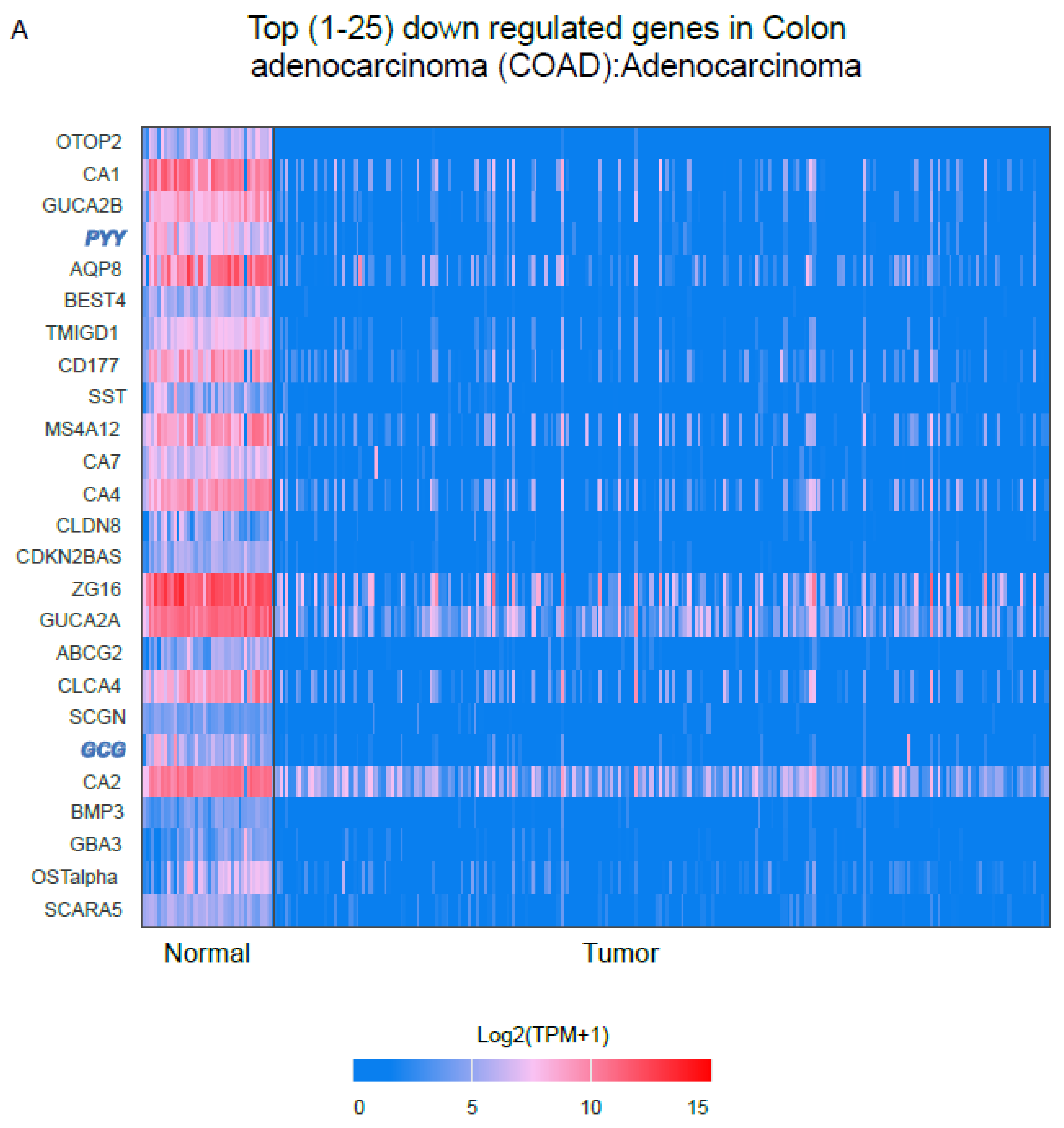

2.4. RNA-Seq Analysis from the TCGA Platform Identified GCG and PYY as One of the Top 25 Most Downregulated Genes in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) Tumor Samples

2.5. The Downregulation of EECs–Associated Genes and the Upregulation of Paneth Cell–Related Genes Within the COAD Tumor Microenvironment Occur Independently of Tumor Stage

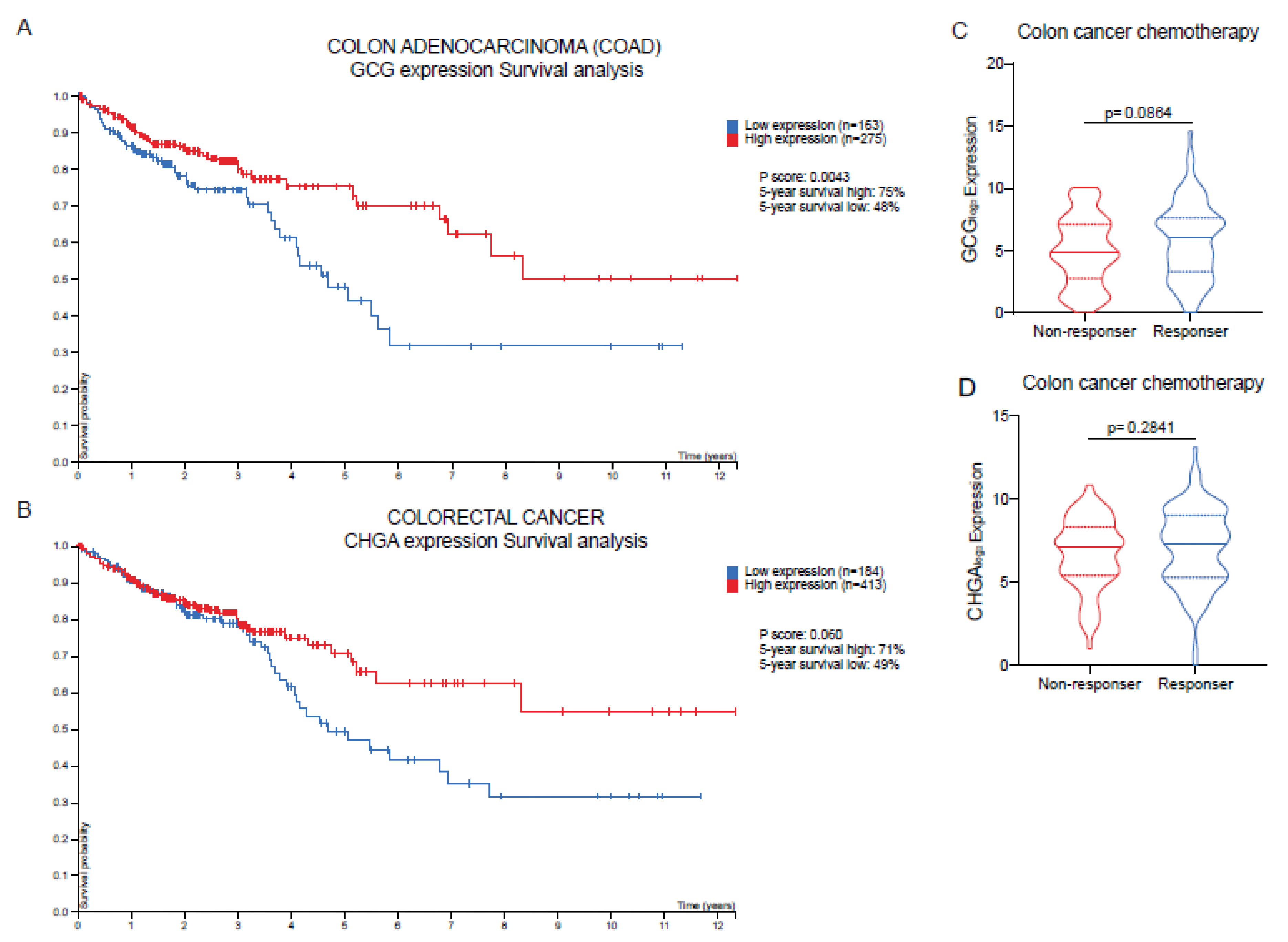

2.6. High Expression Levels of GCG and CHGA Are Positively Associated with Improved Overall Survival and Enhanced Chemotherapy Responsiveness in Patients with COAD Tumors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Databases Collection

4.2. Differential Expression Analysis Datasets from NCBI

4.3. RNAseq Differential Expression Analysis from TCGA Database

4.4. Survival Analysis and Chemotherapy Responder

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzić, J.; Grivennikov, S.; Karin, E.; Karin, M. Inflammation and Colon Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2101–2114.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, G.A.; Heisel, W.E.; Afshin, A.; Jensen, M.D.; Dietz, W.H.; Long, M.; Kushner, R.F.; Daniels, S.R.; Wadden, T.A.; Tsai, A.G.; et al. The Science of Obesity Management: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev 2018, 39, 79–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Zhang, W. Obesity and Cancer: Inflammation Bridges the Two. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2016, 29, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Seo, Y.-R.; Sung, M.-K. Effects of Diet-Induced Obesity on Colitis-Associated Colon Tumor Formation in A/J Mice. Int J Obes 2012, 36, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.A.; Woodward, M.; Huxley, R. Obesity and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 31 Studies with 70,000 Events. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2007, 16, 2533–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustgi, A.K. The Genetics of Hereditary Colon Cancer. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 2525–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, J.J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Enteroendocrine Cells-Sensory Sentinels of the Intestinal Environment and Orchestrators of Mucosal Immunity. Mucosal Immunol 2018, 11, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Ray, S.K.; Singh, N.K.; Johnston, B.; Leiter, A.B. Basic Helix-loop-helix Transcription Factors and Enteroendocrine Cell Differentiation. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011, 13, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastide, P.; Darido, C.; Pannequin, J.; Kist, R.; Robine, S.; Marty-Double, C.; Bibeau, F.; Scherer, G.; Joubert, D.; Hollande, F.; et al. Sox9 Regulates Cell Proliferation and Is Required for Paneth Cell Differentiation in the Intestinal Epithelium. J Cell Biol 2007, 178, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendel, S.K.; Kellermann, L.; Hausmann, A.; Bindslev, N.; Jensen, K.B.; Nielsen, O.H. Tuft Cells and Their Role in Intestinal Diseases. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchenough, G.M.H.; Johansson, M.E.; Gustafsson, J.K.; Bergström, J.H.; Hansson, G.C. New Developments in Goblet Cell Mucus Secretion and Function. Mucosal Immunol 2015, 8, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehne de Gonzalez, A.; del Portillo, A. P754 Beyond Paneth Cell Metaplasia: Small Intestinal Metaplasia of the Sigmoid Colon in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, i885–i886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevins, C.L.; Salzman, N.H. Paneth Cells, Antimicrobial Peptides and Maintenance of Intestinal Homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011, 9, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawardene, A.R.; Corfe, B.M.; Staton, C.A. Classification and Functions of Enteroendocrine Cells of the Lower Gastrointestinal Tract. Int J Exp Pathol 2011, 92, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. The GLP-1 Journey: From Discovery Science to Therapeutic Impact. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Cong, Y. Enteroendocrine Cells: Sensing Gut Microbiota and Regulating Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020, 26, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.M.; Yariwake, V.Y.; Alves, R.W.; de Araujo, D.R.; Andrade-Oliveira, V. Crosstalk between Incretin Hormones, Th17 and Treg Cells in Inflammatory Diseases. Peptides (N.Y.) 2022, 155, 170834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayasu, I.; Ohkusa, T.; Kajiura, K.; Kanno, J.; Sakamoto, S. Promotion of Colorectal Neoplasia in Experimental Murine Ulcerative Colitis. Gut 1996, 39, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, O.; Nita, M.E.; Nagawa, H.; Fujii, S.; Tsuruo, T.; Muto, T. Expressions of Cell Cycle Regulators in Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Japanese Journal of Cancer Research 1997, 88, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvhengo, T.; Mabasa, S.; Molepo, E.; Taunyane, I.; Palweni, S.T. Paneth Cell, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Diabetes Mellitus. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, F.; Stroehlein, J.R.; Wei, D. Context-Dependent Functions of KLF4 in Cancers: Could Alternative Splicing Isoforms Be the Key? Cancer Lett 2018, 438, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullayeva, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.-C.; Simmons, A.; Novelli, M.; Huseynova, I.; Lastun, V.L.; Bodmer, W. Goblet Cell Differentiation Subgroups in Colorectal Cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.M.; Richards, P.; Cairns, L.S.; Rogers, G.J.; Bannon, C.A.M.; Parker, H.E.; Morley, T.C.E.; Yeo, G.S.H.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Overlap of Endocrine Hormone Expression in the Mouse Intestine Revealed by Transcriptional Profiling and Flow Cytometry. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3054–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierl, M.S.; Karoulias, N.; Wende, H.; Strehle, M.; Birchmeier, C. The Zinc-Finger Factor Insm1 (IA-1) Is Essential for the Development of Pancreatic β Cells and Intestinal Endocrine Cells. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 2465–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naya, F.J.; Huang, H.-P.; Qiu, Y.; Mutoh, H.; DeMayo, F.J.; Leiter, A.B.; Tsai, M.-J. Diabetes, Defective Pancreatic Morphogenesis, and Abnormal Enteroendocrine Differentiation in BETA2/NeuroD-Deficient Mice. Genes Dev 1997, 11, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, C.F. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A Comparative Review. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011, 13, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collombat, P.; Mansouri, A.; Hecksher-Sørensen, J.; Serup, P.; Krull, J.; Gradwohl, G.; Gruss, P. Opposing Actions of Arx and Pax4 in Endocrine Pancreas Development. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 2591–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estall, J.L.; Drucker, D.J. Glucagon-Like Peptide-2. Annu Rev Nutr 2006, 26, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradwohl, G.; Dierich, A.; LeMeur, M.; Guillemot, F. Neurogenin3 Is Required for the Development of the Four Endocrine Cell Lineages of the Pancreas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.; Garofalo, D.C.; Balderes, D.A.; Mastracci, T.L.; Dias, J.M.; Perlmann, T.; Ericson, J.; Sussel, L. Lmx1a Functions in Intestinal Serotonin-Producing Enterochromaffin Cells Downstream of Nkx2.2. Development 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.P.; Perreault, N.; Goldstein, B.G.; Lee, C.S.; Labosky, P.A.; Yang, V.W.; Kaestner, K.H. The Zinc-Finger Transcription Factor Klf4 Is Required for Terminal Differentiation of Goblet Cells in the Colon. Development 2002, 129, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis, M.; De Koning, B.A.E.; De Bruijn, A.C.J.M.; Velcich, A.; Meijerink, J.P.P.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Büller, H.A.; Dekker, J.; Van Seuningen, I.; Renes, I.B.; et al. Muc2-Deficient Mice Spontaneously Develop Colitis, Indicating That MUC2 Is Critical for Colonic Protection. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, T.K.; Kazanjian, A.; Whitsett, J.; Shroyer, N.F. SAM Pointed Domain ETS Factor (SPDEF) Regulates Terminal Differentiation and Maturation of Intestinal Goblet Cells. Exp Cell Res 2010, 316, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbe, F.; Sidot, E.; Smyth, D.J.; Ohmoto, M.; Matsumoto, I.; Dardalhon, V.; Cesses, P.; Garnier, L.; Pouzolles, M.; Brulin, B.; et al. Intestinal Epithelial Tuft Cells Initiate Type 2 Mucosal Immunity to Helminth Parasites. Nature 2016, 529, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracz, A.D.; Samsa, L.A.; Fordham, M.J.; Trotier, D.C.; Zwarycz, B.; Lo, Y.-H.; Bao, K.; Starmer, J.; Raab, J.R.; Shroyer, N.F.; et al. Sox4 Promotes Atoh1-Independent Intestinal Secretory Differentiation Toward Tuft and Enteroendocrine Fates. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1508–1523.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroyer, N.F.; Wallis, D.; Venken, K.J.T.; Bellen, H.J.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Gfi1 Functions Downstream of Math1 to Control Intestinal Secretory Cell Subtype Allocation and Differentiation. Genes Dev 2005, 19, 2412–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Miramontes, C.E.; De Haro-Acosta, J.; Aréchiga-Flores, C.F.; Verdiguel-Fernández, L.; Rivas-Santiago, B. Antimicrobial Peptides in Domestic Animals and Their Applications in Veterinary Medicine. Peptides (N.Y.) 2021, 142, 170576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Balasubramanian, I.; Laubitz, D.; Tong, K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Lin, X.; Flores, J.; Singh, R.; Liu, Y.; Macazana, C.; et al. Paneth Cell-Derived Lysozyme Defines the Composition of Mucolytic Microbiota and the Inflammatory Tone of the Intestine. Immunity 2020, 53, 398–416.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Qin, K.; Fan, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, P.; Zeng, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, J.; et al. The Evolving Roles of Wnt Signaling in Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation, the Development of Human Diseases, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Genes Dis 2024, 11, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, N.; van Es, J.H.; Kuipers, J.; Kujala, P.; van den Born, M.; Cozijnsen, M.; Haegebarth, A.; Korving, J.; Begthel, H.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Identification of Stem Cells in Small Intestine and Colon by Marker Gene Lgr5. Nature 2007, 449, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Sui, H.; Fang, F.; Li, Q.; Li, B. The Application of ApcMin/+ Mouse Model in Colorectal Tumor Researches. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019, 145, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition <scp>AJCC</Scp> Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to Build a Bridge from a Population-based to a More “Personalized” Approach to Cancer Staging. CA Cancer J Clin 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betge, J.; Schneider, N.I.; Harbaum, L.; Pollheimer, M.J.; Lindtner, R.A.; Kornprat, P.; Ebert, M.P.; Langner, C. MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in Colorectal Cancer: Expression Profiles and Clinical Significance. Virchows Archiv 2016, 469, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.A.; Kain, T.; Drucker, D.J. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Activation Inhibits Growth and Augments Apoptosis in Murine CT26 Colon Cancer Cells. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3362–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.A.; Baggio, L.L.; Yusta, B.; Longuet, C.; Rowland, K.J.; Cao, X.; Holland, D.; Brubaker, P.L.; Drucker, D.J. GLP-1R Agonists Promote Normal and Neoplastic Intestinal Growth through Mechanisms Requiring Fgf7. Cell Metab 2015, 21, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Park, J.; Lim, J.; Jeong, J.; Dinesh, R.K.; Maher, S.E.; Kim, J.; Park, S.; Hong, J.Y.; Wysolmerski, J.; et al. Metastasis of Colon Cancer Requires Dickkopf-2 to Generate Cancer Cells with Paneth Cell Properties. Elife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Gregorieff, A.; Begthel, H.; Clevers, H. Canonical Wnt Signals Are Essential for Homeostasis of the Intestinal Epithelium. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 1709–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, P.; Peignon, G.; Slomianny, C.; Taketo, M.M.; Colnot, S.; Robine, S.; Lamarque, D.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Perret, C.; Romagnolo, B. A Genetic Study of the Role of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling in Paneth Cell Differentiation. Dev Biol 2008, 324, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colozza, G.; Lee, H.; Merenda, A.; Wu, S.-H.S.; Català-Bordes, A.; Radaszkiewicz, T.W.; Jordens, I.; Lee, J.-H.; Bamford, A.-D.; Farnhammer, F.; et al. Intestinal Paneth Cell Differentiation Relies on Asymmetric Regulation of Wnt Signaling by Daam1/2. Sci Adv 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Arribillaga, E.; Yan, B.; Lobo-Jarne, T.; Guillén, Y.; Menéndez, S.; Andreu, M.; Bigas, A.; Iglesias, M.; Espinosa, L. Accumulation of Paneth Cells in Early Colorectal Adenomas Is Associated with Beta-Catenin Signaling and Poor Patient Prognosis. Cells 2021, 10, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Luo, G.; Yang, P.; Chen, F.; Zhang, B.; Yang, C.; Li, G.; Chang, J. The Regulatory Role of Neuropeptide Gene Glucagon in Colorectal Cancer: A Comprehensive Bioinformatic Analysis. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Ewald, J.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: A Visual Analytics Platform for Comprehensive Gene Expression Profiling and Meta-Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W234–W241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.; Cho, M.; Wang, X. OncoDB: An Interactive Online Database for Analysis of Gene Expression and Viral Infection in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D1334–D1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An Update to the Integrated Cancer Data Analysis Platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P.; et al. STRING V10: Protein–Protein Interaction Networks, Integrated over the Tree of Life. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science (1979) 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, J.T.; Győrffy, B. ROCplot.Org: Validating Predictive Biomarkers of Chemotherapy/Hormonal Therapy/Anti-HER2 Therapy Using Transcriptomic Data of 3,104 Breast Cancer Patients. Int J Cancer 2019, 145, 3140–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell type | Gene | Gene Function / Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enteroendocrine cell | GCG | GLP-1/2 hormone L-cell marker | [24] |

| PYY | Hormone secreted by L-cells | ||

| CHGA | Classical marker | [15] | |

| INSM1 | Neuroendocrine transcription factor | [25] | |

| NEUROD1 | Neuroendocrine differentiation | [26] | |

| DPP4 | Incretin degradation (GLP-1, GIP) | [27] | |

| ARX | Regulates the fate of endocrine subtypes | [28] | |

| NKX2.2 | Required for intestinal endocrine differentiation | [24] | |

| GLP2R | GLP-2 receptor | [29] | |

| PAX6 | Regulates EEC subtypes | [24] | |

| GIPR | GIP receptor | ||

| NEUROG3 | EEC master regulator | [30] | |

| PAX4 | Intestinal endocrine development | [24] | |

| LMX1A | Regulates serotonin | [31] | |

| GLP1R | GLP-1 receptor | [24] | |

| ISL1 | Endocrine regulation | ||

| GIP | Hormone produced by K cells | ||

| Goblet cell | KLF4 | Goblet cell differentiation | [32] |

| MUC2 | Major secreted mucin | [33] | |

| SPDEF | Essential for goblet cells | [34] | |

| Tuft cell | POU2F3 | Tuft cell master regulator | [35] |

| SOX4 | Tuft development | [36] | |

| Paneth cell | GFI1 | Regulation of Paneth cells | [37] |

| DEFA1 | Antimicrobial peptide produced by Paneth cell | [38] | |

| LYZ | Lysozyme a classic marker | [39] | |

| SOX9 | Essential transcription factor | [10] | |

| WISP1 | Maintains niche and Paneth differentiation | [40] | |

| Stem cell | LGR5 | Intestinal stem cell marker | [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).