1. Introduction

Small bowel cancers are rare, representing less than 5% of gastrointestinal cancers, though their incidence is rising [

1,

2]. Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) comprises roughly one-third of these cases. Due to its rarity, detailed molecular and clinicopathological data remain limited [

1,

3,

4]. Genomic profiling has revealed that SBA has distinct molecular features compared to colorectal and gastric cancers [

5]. Additionally, differences in molecular and clinicopathological features have been reported across small bowel subsites [

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. For example, duodenal adenocarcinomas have higher rates of

CDKN2A and

ERBB2 alterations but lower incidences of

BRAF,

PTEN, and

PIK3R1 mutations, as well as lower overall tumor mutational burden, compared to jejunal and ileal adenocarcinomas [

5,

11].

It remains uncertain whether carcinomas originating throughout the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum share common molecular characteristics and carcinogenetic pathways. Preinvasive epithelial lesions in the small bowel are less frequently observed than in the colon and are predominantly located in the duodenum. Sporadic non-ampullary duodenal adenomas, excluding familial adenomatous polyposis and other predisposing conditions, account for 40% of such lesions [

12,

13]. Okada et al. reported a 4.7% progression rate from sporadic adenoma to non-invasive carcinoma [

14]. However, the relatively low incidence of

APC mutations (7.1–37%) in sporadic adenocarcinomas, despite their high frequency in adenomas, suggests that the adenoma-carcinoma sequence may not be a dominant pathway in SBA carcinogenesis [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Despite the low

APC mutation rate, Wnt pathway activation is relatively frequent in SBA, as evidenced by abnormal nuclear localization and/or reduced membranous β-catenin staining in 40–50% of cases, based on immunohistochemistry [

15,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Although

CTNNB1 mutations may partly account for this [

24], their prevalence is insufficient to explain the high rates of Wnt activation [

5,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Consequently, the extent and nature of Wnt pathway involvement in SBA remains controversial.

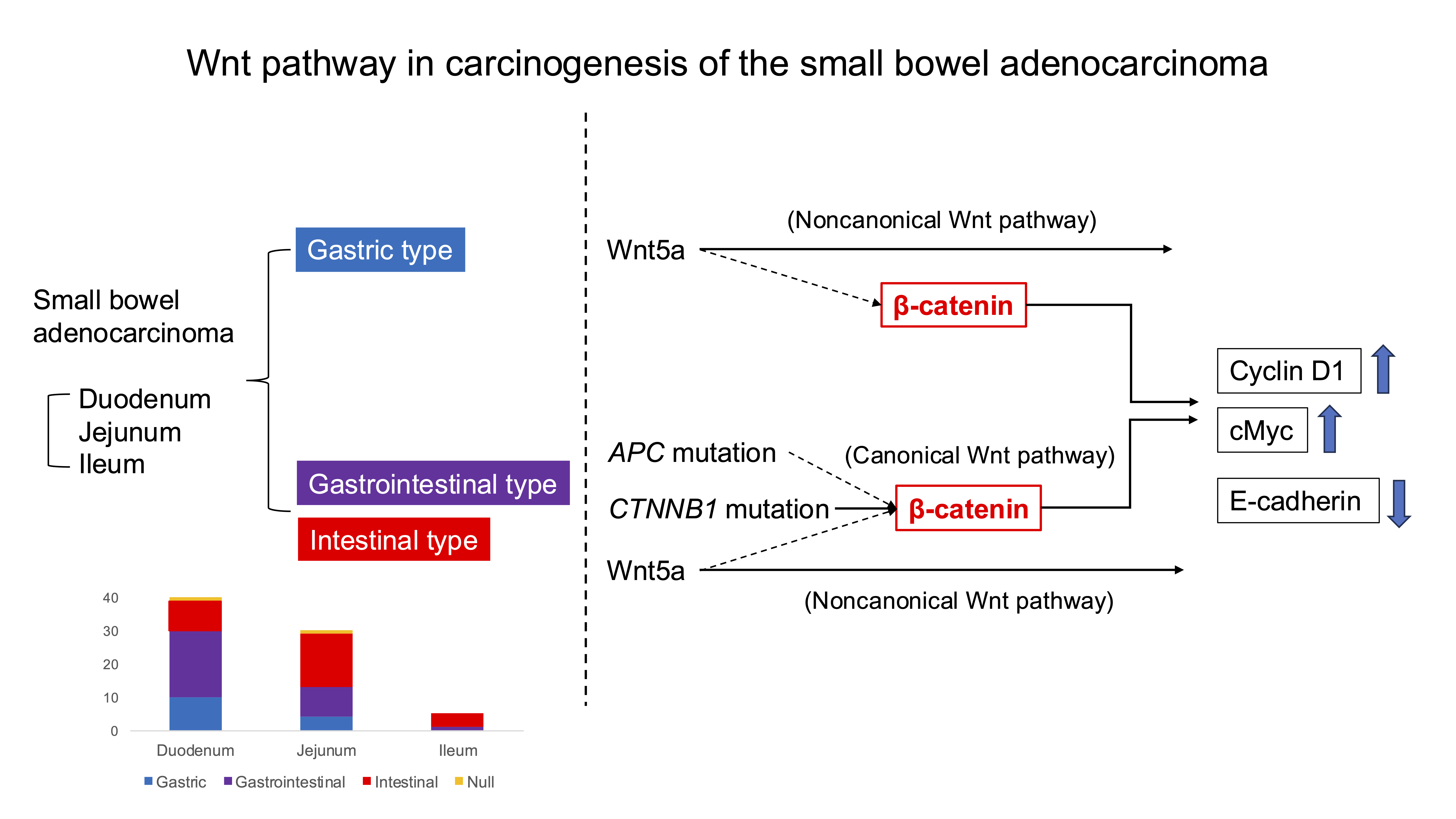

The Wnt signaling pathway can be divided into canonical and noncanonical pathways [

29]. The canonical Wnt pathway involves cytosolic β-catenin accumulation, nuclear translocation, and interaction with TCF/LEF transcription factors to induce the expression of various oncoproteins, such as cyclin D1 and c-Myc [

30,

31]. In contrast to the canonical Wnt/

β-catenin signaling, the noncanonical (β-catenin-independent) Wnt pathway, including Wnt/Ca²⁺ and planar cell polarity subtypes, is less studied in carcinogenesis. Wnt5a, a key noncanonical Wnt ligand, activates downstream signaling through Frizzled receptors, influencing cell migration and adhesion [

32].

To date, the functional status and clinicopathological relevance of canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathways in SBA have not been thoroughly elucidated. In this study, we investigated the correlation between Wnt pathway-related genomic alterations and the expression of downstream target gene products or associated proteins to better understand their roles in SBA carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Tissue Samples

We analyzed 75 tissue samples of duodenal, jejunal and ileal adenocarcinoma obtained from the archives of the Department of Pathology at Nippon Medical School Hospital and the Department of Pathology at Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital. These samples were used for immunohistochemical analysis of β-catenin, cyclin D1, c-Myc, E-cadherin, and Wnt5a expression. To focus on sporadic small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA), patients with predisposing conditions—such as Lynch syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, celiac disease, or Crohn’s disease—were excluded. Cases of ampullary adenocarcinomas and suspected metastatic cancers were also excluded. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was defined as the interval from the date of initial surgery to death caused by SBA, excluding other causes. All patients provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School. Tumor staging was based on the TNM classification by the International Union Against Cancer.

2.2. Immunohistochemical Analysis

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and deparaffinized. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersion in 0.5% H

2O

2–methanol for 10 minutes. Antigen retrieval was performed using microwave heating in either 0.01 mol/L citrate phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) or EDTA (pH 9.0), followed by incubation with 10% normal horse or goat serum to block nonspecific binding. Slides were incubated for 18 hours at 4°C with primary antibodies (listed in

Supplemental Table S1). Secondary detection was performed using biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:200, Vector) at 25°C for 30 minutes, followed by the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex for another 30 minutes at the same temperature. Visualization was achieved using 3,3‘-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution containing 0.03% H

2O

2.

2.3. Evaluation of Immunohistochemical Staining

All slides were independently evaluated by two observers (A.H. and A.S.), blinded to clinical data. Discrepancies were resolved using a multi-headed microscope. Staining intensity was scored based on the proportion of positively stained epithelial cells, using the following 5-point scale: 0, <10%; 1, 10–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; and 4, >75%. For cyclin D1 and c-Myc, cases with nuclear staining in ≥10% of cancer cells (score 1–4) were considered positive. For E-cadherin and β-catenin, expression was considered preserved if membranous staining was equivalent to normal small intestinal epithelium in >75% of cancer cells (score 4) and reduced if less than this threshold (score 0–3). In addition, β-catenin nuclear expression was considered as aberrant, when >10% of cancer cells exhibited nuclear positivity. Mucin immunophenotypes were categorized as gastric, intestinal, gastrointestinal, or null types, based on immunostaining for MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC6, and CD10. MUC 2 and CD10 were considered intestinal markers, while MUC5AC and MUC6 were considered gastric markers. Tumors expressing both gastric and intestinal markers were classified as gastrointestinal-type, and those expressing neither were classified as null-type.

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) status was assessed via immunostaining for MLH1, MSH2, MLH6, and PMS2. Tumors lacking expression of any one MMR protein were categorized as MMR-deficient (dMMR); all others were considered MMR-proficient (pMMR).

2.4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

NGS was performed on 48 SBA cases of comprehensive gene mutation analysis. DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing were conducted as previously described [

27,

28,

33]. Briefly, approximately 10 ng of DNA per sample was amplified using multiplex PCR with the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which targets 207 amplicons covering hotspot regions for 50 commonly mutated oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes as cataloged in COSMIC. Sequencing was performed on the Ion Torrent PGM™ system, and data were analyzed using Torrent Suite™ Software v5.2.2. Variant calling was carried out using the CHP2 Panel Somatic PGM under low stringency settings. Only variants classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to CinVar were included in the final analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Associations between immunohistochemical findings and clinicopathological features were evaluated using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. When multiple comparisons were conducted, the Bonferroni correction was applied. Correlations between protein expressions were assessed using the same statistical tests. The impact of clinicopathological variables on cancer-specific survival (CSS) was assessed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data of Patient

The study included 75 patients, comprising 53 men and 22 women, with ages ranging from 32 to 84 years (mean: 65 years; median: 68 years). At the time of analysis, 22 patients had died. The overall 5-year survival rate was 71%. The median follow-up duration was 52 months (mean: 50 months; range, 5–115 months)

3.2. Localization of β-Catenin, Cyclin D1, c-Myc, E-cadherin, and Wnt5a in SBA

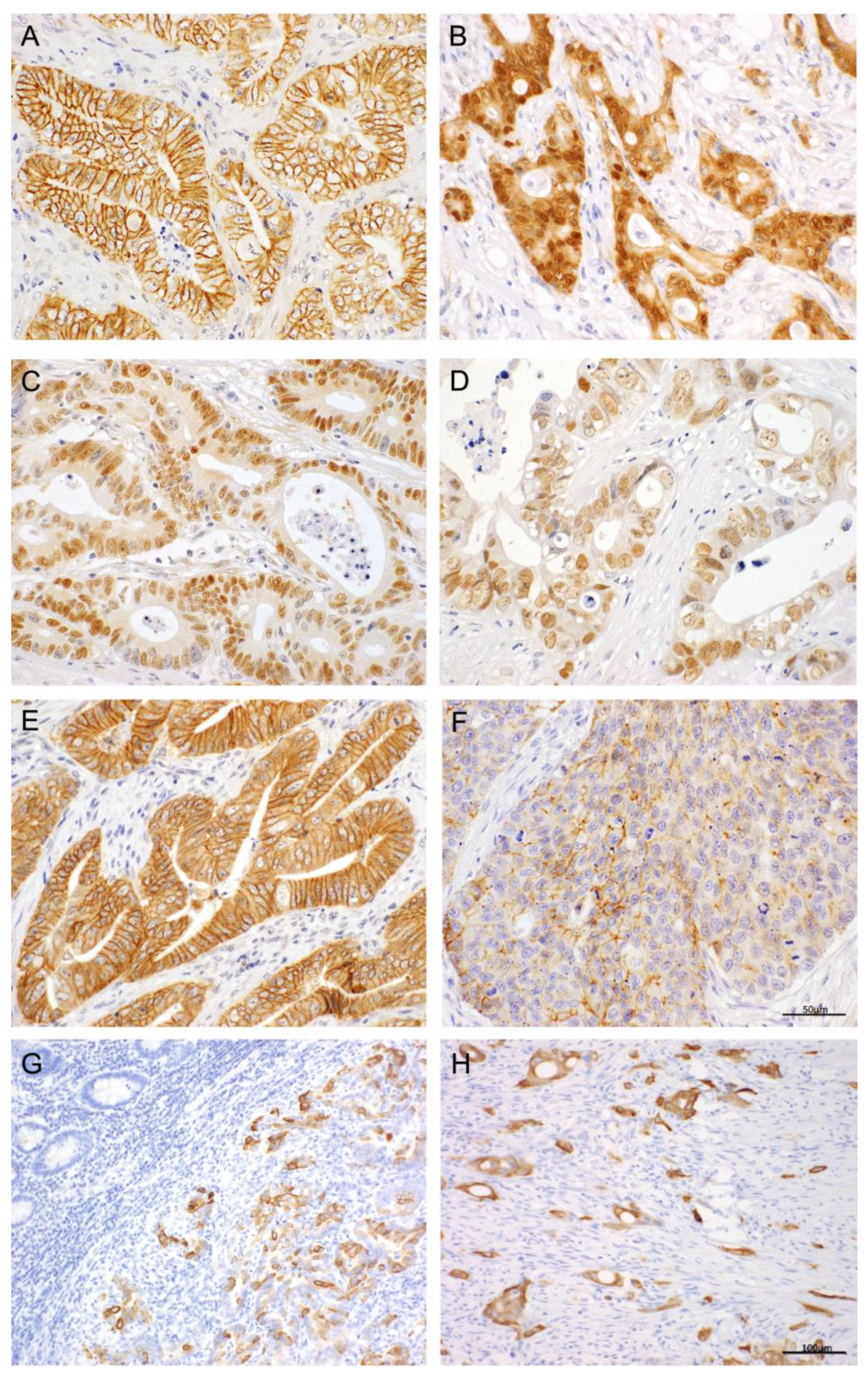

Immunostaining patterns for β-catenin, cyclin D1, c-Myc, E-cadherin, and Wnt5a are illustrated in

Figure 1. Quantitative immunoreactivity data, based on the percentage of unequivocally positive epithelial cells, are presented in

Supplemental Table S2. Reduced membranous expression of β-catenin, often accompanied by cytoplasmic localization in tumor cells, was observed in 28 (37%). Among these, nuclear expression of β-catenin was identified at the invasive tumor front in 9 cases (13%). Cyclin D1 expression was exclusively nuclear in 45 cases (60%). Similarly, c-Myc expression was observed exclusively in the nuclei of tumor cells in 31 cases (41%). Reduced membranous expression of E-cadherin in cancer cells occurred in 33 cases (44%). Wnt5a was expressed in the membranes and cytoplasm of tumor cells in 35 cases (47%) but was nearly undetectable in non-neoplastic epithelium. Sporadic Wnt5a positivity was also noted in some stromal cells including fibroblasts.

3.3. Association Between Marker Expression and Clinicopathological Factors

The relationships between immunohistochemical findings and clinicopathological features are summarized in

Table 1.

β-Catenin: Reduced membranous expression was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and advanced TNM stage. However, nuclear expression of β-catenin showed no significant correlation with clinicopathological parameters.

E-cadherin: Reduced membranous expression of E-cadherin was more common in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and significantly correlated with histological subtype, depth of invasion (pT factor), lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and advanced TNM stage.

Cyclin D1: Expression was more frequent in cases with lymph node metastasis and was less commonly seen in the gastric-type SBA.

Wnt5a: Expression significantly correlated with depth of invasion (pT factor), lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and higher TNM stage.

3.4. Interrelationship Between Marker Expressions

The interrelationships between β-catenin, cyclin D1, c-Myc, E-cadherin, and Wnt5a expressions are presented in

Table 2.

A significant positive correlation was found between reduced membranous β-catenin expression and both cyclin D1 and c-Myc. Cyclin D1 and c-Myc expressions were also significantly positively correlated with each other. Reduced membranous E-cadherin expression was associated with reduced membranous β-catenin expression, cyclin D1 positivity, and Wnt5a expression. In total, 60% of cases exhibited reduced membranous β-catenin expression and/or Wnt5a expression, which was significantly associated with increased expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc.

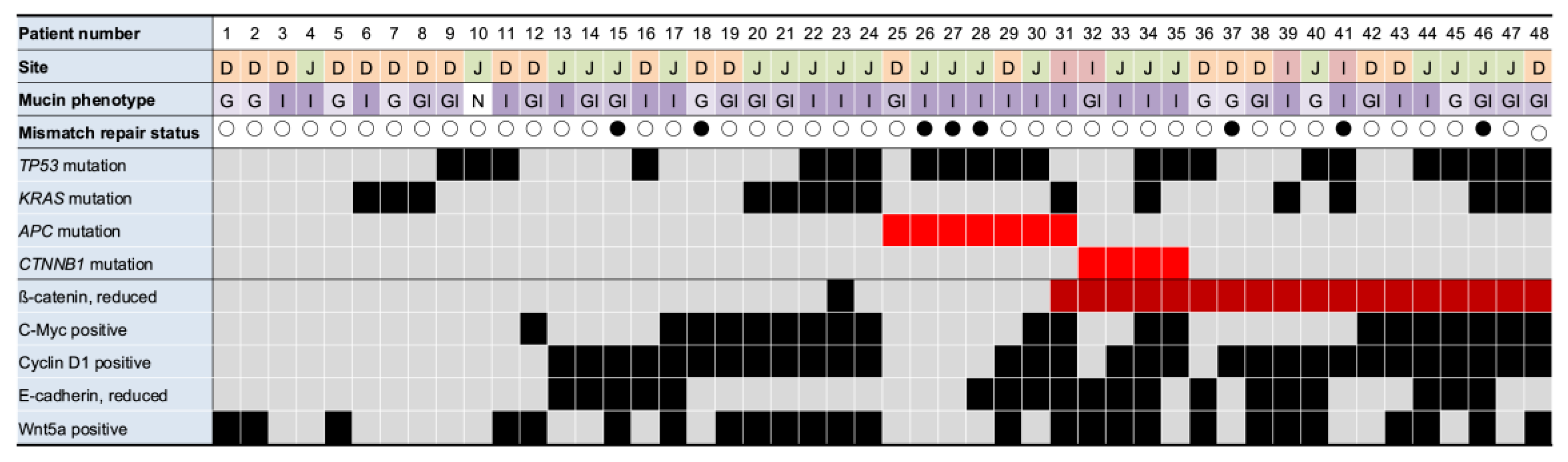

3.5. Association Between Gene Mutations and Marker Expression

Raw next-generation sequencing (NGS) results are provided in

Supplemental Table S3. Genomic alterations were identified in 40 of the 48 cases (83%). The most frequently mutated genes were

TP53, 47.9%;

KRAS, 31.3%;

APC, 14.6%; and

CTNNB1, 8.3%. Detailed correlations between mutations and clinicopathological parameters are outlined in

Supplemental Table S4.

TP53 mutations were more prevalent in tumors located in the jejunum.

APC and

CTNNB1 mutations were exclusively identified in intestinal and gastrointestinal-type SBA, with none detected in gastric-type SBA. No single case harbored mutations in both

APC and the

CTNNB1. All four cases with

CTNNB1 mutations exhibited reduced membranous β-catenin expression. In contrast, only one of the seven

APC mutation cases showed reduced similar β-catenin reduction (

Figure 2).

Among 20 cases with reduced β-catenin expression, 13 (patients 36–48) had neither APC nor CTNNB1 mutations. Of the 7 APC mutant cases, cyclin D1 was positive in 3 cases (patients 29–31) and c-Myc was positive in 2 cases (patients 30 and 31). The remaining 3 cases (patients 25–28) were negative for both cyclinD1 and c-Myc but showed TP53 mutations and mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency. Of the 4 CTNNB1 mutant cases, cyclin D1 was positive in 3 cases (patients 33–35) and c-Myc was positive in 2 cases (patients 34 and 35). All four tumors had proficient MMR status, with two lacking TP53 and KRAS mutations.

3.6. Comparative Survival Analysis

Depth of invasion (pT factor), lymph node metastasis, and expression of β-catenin, E-cadherin, and Wnt5a were significantly associated with cancer-specific survival (CSS). No single gene mutation showed a statistically significant association with CSS. In multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, lymph node status was the only independent prognostic factor (

Table 3, Model #1 and #2). However, in an alternative model that included pT factor, lymph node status, and reduced membranous expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin, both lymph node status and reduced membranous expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin retained independent prognostic significance (Model #3).

4. Discussion

To elucidate the carcinogenetic pathway in SBA, we performed a comprehensive analysis of gene mutations and evaluated the localization of proteins that associated with these gene mutations, along with their correlation with clinicopathological features.

Gene mutations link to the Wnt pathway in SBA included

APC and

CTNNB1, with one or the other present in 23% of cases. Notably, only one of seven SBA cases with

APC mutations exhibited reduced membranous β-catenin expression, suggesting limited activation of the canonical Wnt pathway even in the presence of

APC mutations. Furthermore, six of these seven

APC-mutant cases also harbored

TP53 mutations, and three showed MMR deficiency, implying that

APC mutations may not independently drive SBA carcinogenesis. Conversely, β-catenin staining abnormalities—an indicator of canonical Wnt pathway activation—were observed in 37% of SBA cases. Previous studies report abnormal β-catenin staining in 7–93% of SBA cases, and nuclear localization in 7–48%, which aligns with our findings [

15,

16,

22]. These studies, like ours, observed a lack of correlation between abnormal β-catenin expression and

APC mutations [

15,

16]. The current study has shown higher rates of β-catenin expression abnormalities than were found for the combined mutation rates of

APC and

CTNNB1. Moreover, we found higher rates of cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression than that of

APC/

CTNNB1 mutations, indicating downstream activation of Wnt target genes despite the absence of these mutations. To address this discrepancy, we categorized SBA into gastric and intestinal types based on histologic phenotype, since prior research suggests that these subtypes may arise through distinct molecular pathways [

13]. Ota et al. reported that the canonical Wnt pathway is less involved in gastric-type non-ampullary duodenal tumors, which exhibit lower rates of nuclear β-catenin expression and

APC mutations [

17]. Our results support this:

APC and

CTNNB1 mutations were exclusive to intestinal-type SBA, with a combined mutation rate of 39.1% (9/23), closely matching the 44.8% (13/29) abnormal β-catenin expression rate in this subtype. These findings suggest that the canonical Wnt pathway contributes predominantly to intestinal-type SBA, though

APC mutations alone may be insufficient to drive progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma.

No prior studies have examined the relationship between the Wnt pathway target proteins and β-catenin abnormalities in SBA. We found that c-Myc was expressed in 41% cases and significantly correlated with abnormal β-catenin expression, indicating its upregulation via the canonical Wnt pathway. Cyclin D1 was expressed in 60% of cases, paralleling a previous study [

34]. Although cyclin D1 expression showed a strong correlation with abnormal β-catenin expression, nearly half of the cyclin D1 positive cases lacked β-catenin abnormalities, suggesting that other regulatory pathways may also influence cyclin D1 expression.

Given the gap between the relatively low frequency of

APC/

CTNNB1 mutations and the high frequency of Wnt pathway activation, we hypothesized that the noncanonical Wnt pathway may also play a role in SBA carcinogenesis. We therefore evaluated the localization of Wnt5a, a ligand of the noncanonical Wnt pathway, by immunohistochemistry [

35]. Wnt5a was expressed in 46.7% of SBA cases, primarily in cancer cells. This is the first study to explore Wnt5a localization in SBA and its association with clinicopathological parameters. We found that Wnt5a expression was significantly correlated with pT factor, metastasis, and poor prognosis, independent of mucin phenotype or tumor location. Moreover, Wnt5a expression correlated with cyclin D1 and E-cadherin localization, but not with β-catenin or c-Myc.

Previous studies in colorectal cancer have shown that Wnt5a can act as both an oncogene and tumor suppressor depending on downstream pathway activation [

36]. Wnt5a is capable of modulating both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling [

37,

38], and its prognostic value remains context-dependent [

36]. In our study, Wnt5a expression was associated with poor prognosis, possibly due to its role in promoting epithelial mesenchymal transition [

39]. The observed correlation between Wnt5a and E-cadherin downregulation supports this mechanism and highlights the potential involvement of β-catenin-independent Wnt pathway in SBA progression.

Two earlier studies reported reduced membranous E-cadherin expression in 38% and 41.8% of SBA cases, respectively, slightly lower than our findings [

15,

22]. These variations may reflect differences in the proportion of advanced-stage tumors. In our cohort, E-cadherin downregulation was associated with β-catenin abnormalities and correlated with poor prognosis. These findings are consistent with those of Lee et al., who also reported that E-cadherin and β-catenin expression are significant worse prognostic factors in SBA [

22]. Notably, E-cadherin loss did not correlate with any genomic alteration but was significantly associated with protein-level β-catenin abnormalities.

Although prior studies suggest that small bowel subsite (duodenum, jejunum, ileum) may influence molecular features [

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], we found no significant association between tumor location and genomic alterations, except for

TP53 mutations, which were more common in jejunal tumors. Instead, our results indicate that histologic phenotype, rather than anatomical location, better reflects the molecular and clinicopathological characteristics of SBA.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size limited the number of cases available for next-generation sequencing. In addition, there is a bias in tumor location. Second, MMR status was assessed solely via immunohistochemistry, without MMR testing. Third, the Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 used includes only a subset of genes, potentially missing other relevant Wnt pathway alterations.

5. Conclusions

Genomic alterations in the Wnt pathway, including APC and CTNNB1 mutations, were identified in only 23% of all SBA cases, but increased to 39% in intestinal-type SBA. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed reduced membranous β-catenin expression in 37% of all cases and elevated expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc in 60%, suggesting that Wnt pathway activation extends beyond canonical mutations. This discrepancy may be attributed to the involvement of noncanonical Wnt signaling, notably via Wnt5a, which is associated with poor prognosis and epithelial mesenchymal transition related changes. Importantly, reduced expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin were independently associated with worse outcome in multivariate analysis. Together, these results suggest that canonical Wnt signaling is a key driver of carcinogenesis in intestinal-type SBA, while noncanonical Wnt signaling may contribute to tumor progression across SBA subtypes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N. and A.T.; Methodology, T.N., T.Y., S.K., A.H. and A.S.; Validation, T.Y. and A.S.; Formal analysis, T.N.; Investigation, T.N. and S.F.; Resources, A.H., K.M. and T.H.; Data curation, T.N., J.O., N.A., K.M., S.T. and T.H.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, T.N.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.T. and K.G.; Visualization, T.N., S.F.; Supervision, A.S. and M.A.; Project Administration, A.T.; Funding Acquisition, M.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School (Approval No. B-2020-164).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Kiyoko Kawahara and Mrs. Akiko Takeda for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSS |

Cancer-specific survival |

| MMR |

DNA mismatch repair |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| SBA |

Small bowel adenocarcinoma |

References

- Pedersen, K. S.; Raghav, K.; Overman, M. J., Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma: Etiology, Presentation, and Molecular Alterations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019, 17, 1135-1141. [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, A. M.; Robaszkiewicz, M.; Jooste, V.; Cariou, M.; Drouillard, A.; Bouvier, V.; Nousbaum, J. B., Trends in incidence of small bowel cancer according to histology: a population-based study. J Gastroenterol 2020, 55, 181-188. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R.; Romiti, A.; Filetti, M.; Roberto, M.; Righini, R.; Botticelli, A.; Pilozzi, E.; Ghidini, M.; Pizzo, C.; Mazzuca, F.; Marchetti, P., Impact of tumor site on the prognosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Tumori 2019, 105, 524-528. [CrossRef]

- Pandya, K.; Overman, M. J.; Gulhati, P., Molecular Landscape of Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Schrock, A. B.; Devoe, C. E.; McWilliams, R.; Sun, J.; Aparicio, T.; Stephens, P. J.; Ross, J. S.; Wilson, R.; Miller, V. A.; Ali, S. M.; Overman, M. J., Genomic Profiling of Small-Bowel Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2017, 3, 1546-1553. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. C.; Wima, K.; Morris, M. C.; Winer, L. K.; Sussman, J. J.; Ahmad, S. A.; Wilson, G. C.; Patel, S. H., Small Bowel Adenocarcinomas: Impact of Location on Survival. J Surg Res 2020, 252, 116-124. [CrossRef]

- Howe, J. R.; Karnell, L. H.; Menck, H. R.; Scott-Conner, C., The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: review of the National Cancer Data Base, 1985-1995. Cancer 1999, 86, 2693-706.

- Overman, M. J.; Hu, C. Y.; Wolff, R. A.; Chang, G. J., Prognostic value of lymph node evaluation in small bowel adenocarcinoma: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer 2010, 116, 5374-82.

- Wilhelm, A.; Galata, C.; Beutner, U.; Schmied, B. M.; Warschkow, R.; Steffen, T.; Brunner, W.; Post, S.; Marti, L., Duodenal localization is a negative predictor of survival after small bowel adenocarcinoma resection: A population-based, propensity score-matched analysis. J Surg Oncol 2018, 117, 397-408.

- Fujimori, S.; Hamakubo, R.; Hoshimoto, A.; Nishimoto, T.; Omori, J.; Akimoto, N.; Tanaka, S.; Tatsuguchi, A.; Iwakiri, K., Risk factors for small intestinal adenocarcinomas that are common in the proximal small intestine. World J Gastroenterol 2022, 28, 5658-5665. [CrossRef]

- Laforest, A.; Aparicio, T.; Zaanan, A.; Silva, F. P.; Didelot, A.; Desbeaux, A.; Le Corre, D.; Benhaim, L.; Pallier, K.; Aust, D.; Pistorius, S.; Blons, H.; Svrcek, M.; Laurent-Puig, P., ERBB2 gene as a potential therapeutic target in small bowel adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2014, 50, 1740-1746. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. D.; Mackey, R.; Brown, N.; Church, J.; Burke, C.; Walsh, R. M., Outcome based on management for duodenal adenomas: sporadic versus familial disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2010, 14, 229-35. [CrossRef]

- Vanoli, A.; Grillo, F.; Furlan, D.; Arpa, G.; Grami, O.; Guerini, C.; Riboni, R.; Mastracci, L.; Di Sabatino, A., Small Bowel Epithelial Precursor Lesions: A Focus on Molecular Alterations. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Fujisaki, J.; Kasuga, A.; Omae, M.; Kubota, M.; Hirasawa, T.; Ishiyama, A.; Inamori, M.; Chino, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tsuchida, T.; Nakajima, A.; Hoshino, E.; Igarashi, M., Sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenoma in the natural history of duodenal cancer: a study of follow-up surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol 2011, 106, 357-64. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. M.; Warren, B. F.; Mortensen, N. J.; Kim, H. C.; Biddolph, S. C.; Elia, G.; Beck, N. E.; Williams, G. T.; Shepherd, N. A.; Bateman, A. C.; Bodmer, W. F., An insight into the genetic pathway of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Gut 2002, 50, 218-23. [CrossRef]

- Bläker, H.; Helmchen, B.; Bönisch, A.; Aulmann, S.; Penzel, R.; Otto, H. F.; Rieker, R. J., Mutational activation of the RAS-RAF-MAPK and the Wnt pathway in small intestinal adenocarcinomas. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004, 39, 748-53. [CrossRef]

- Ota, R.; Sawada, T.; Tsuyama, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Kaizaki, Y.; Hasatani, K.; Yamamoto, E.; Nakanishi, H.; Inagaki, S.; Tsuji, S.; Yoshida, N.; Doyama, H.; Minato, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kasashima, S.; Kubota, E.; Kataoka, H.; Tokino, T.; Yao, T.; Minamoto, T., Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis of cancer-related genes in non-ampullary duodenal adenomas and intramucosal adenocarcinomas. J Pathol 2020, 252, 330-342. [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Naka, T.; Yatabe, Y.; Kojima, M.; Kuwata, T.; Nonaka, S.; Oda, I.; Esaki, M.; Kudo, M.; Gotohda, N.; Yoshida, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sekine, S., APC mutations are common in adenomas but infrequent in adenocarcinomas of the non-ampullary duodenum. J Gastroenterol 2021, 56, 988-998. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Q.; Chen, Z. M.; Wang, H. L., Immunohistochemical investigation of tumorigenic pathways in small intestinal adenocarcinoma: a comparison with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2006, 19, 573-80. [CrossRef]

- Svrcek, M.; Jourdan, F.; Sebbagh, N.; Couvelard, A.; Chatelain, D.; Mourra, N.; Olschwang, S.; Wendum, D.; Fléjou, J. F., Immunohistochemical analysis of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: a tissue microarray study. J Clin Pathol 2003, 56, 898-903. [CrossRef]

- Breuhahn, K.; Singh, S.; Schirmacher, P.; Bläker, H., Large-scale N-terminal deletions but not point mutations stabilize beta-catenin in small bowel carcinomas, suggesting divergent molecular pathways of small and large intestinal carcinogenesis. J Pathol 2008, 215, 300-7.

- Lee, H. J.; Lee, O. J.; Jang, K. T.; Bae, Y. K.; Chung, J. Y.; Eom, D. W.; Kim, J. M.; Yu, E.; Hong, S. M., Combined loss of E-cadherin and aberrant β-catenin protein expression correlates with a poor prognosis for small intestinal adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2013, 139, 167-76. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, T.; Svrcek, M.; Zaanan, A.; Beohou, E.; Laforest, A.; Afchain, P.; Mitry, E.; Taieb, J.; Di Fiore, F.; Gornet, J. M.; Thirot-Bidault, A.; Sobhani, I.; Malka, D.; Lecomte, T.; Locher, C.; Bonnetain, F.; Laurent-Puig, P., Small bowel adenocarcinoma phenotyping, a clinicobiological prognostic study. Br J Cancer 2013, 109, 3057-66. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, B.; Wei, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Zhou, D., Whole-exome sequencing of duodenal adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway mutations. Cancer 2016, 122, 1689-96. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, T.; Svrcek, M.; Henriques, J.; Afchain, P.; Lièvre, A.; Tougeron, D.; Gagniere, J.; Terrebonne, E.; Piessen, G.; Legoux, J. L.; Lecaille, C.; Pocard, M.; Gornet, J. M.; Zaanan, A.; Lavau-Denes, S.; Lecomte, T.; Deutsch, D.; Vernerey, D.; Puig, P. L., Panel gene profiling of small bowel adenocarcinoma: Results from the NADEGE prospective cohort. Int J Cancer 2021, 148, 1731-1742.

- Pan, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.; Ge, W.; Yuan, M.; Jiang, S.; Wan, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, R.; Fang, Y.; Lou, F.; Cao, S.; Han, W., Molecular profiling and identification of prognostic factors in Chinese patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tatsuguchi, A.; Yamada, T.; Ueda, K.; Furuki, H.; Hoshimoto, A.; Nishimoto, T.; Omori, J.; Akimoto, N.; Gudis, K.; Tanaka, S.; Fujimori, S.; Shimizu, A.; Iwakiri, K., Genetic analysis of Japanese patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma using next-generation sequencing. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 723. [CrossRef]

- Hoshimoto, A.; Tatsuguchi, A.; Yamada, T.; Kuriyama, S.; Hamakubo, R.; Nishimoto, T.; Omori, J.; Akimoto, N.; Gudis, K.; Mitsui, K.; Tanaka, S.; Fujimori, S.; Hatori, T.; Shimizu, A.; Iwakiri, K., Relationship Between Immunophenotypes, Genetic Profiles, and Clinicopathologic Characteristics in Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2024, 48, 127-139. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Que, H.; Li, Q.; Wei, X., Wnt/β-catenin mediated signaling pathways in cancer: recent advances, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 171.

- Li, C.; Furth, E. E.; Rustgi, A. K.; Klein, P. S., When You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It: Wnt Signaling Activates Multiple Pathways through the APC/Axin/GSK-3 Complex. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lecarpentier, Y.; Schussler, O.; Hébert, J. L.; Vallée, A., Multiple Targets of the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Signaling in Cancers. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 1248. [CrossRef]

- Kohn, A. D.; Moon, R. T., Wnt and calcium signaling: beta-catenin-independent pathways. Cell Calcium 2005, 38, 439-46. [CrossRef]

- Furuki, H.; Yamada, T.; Takahashi, G.; Iwai, T.; Koizumi, M.; Shinji, S.; Yokoyama, Y.; Takeda, K.; Taniai, N.; Uchida, E., Evaluation of liquid biopsies for detection of emerging mutated genes in metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018, 44, 975-982. [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. Y.; Hong, S. M.; Jang, K. T., Prognostic Significance of Cyclin D1 Expression in Small Intestinal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M. L. P.; Saad, S. T. O.; Roversi, F. M., WNT5A in tumor development and progression: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 155, 113599. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Wu, C., WNT5A: a double-edged sword in colorectal cancer progression. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2023, 792, 108465. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Hernández, E.; Velázquez, D. M.; Castañeda-Patlán, M. C.; Fuentes-García, G.; Fonseca-Camarillo, G.; Yamamoto-Furusho, J. K.; Romero-Avila, M. T.; García-Sáinz, J. A.; Robles-Flores, M., Canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling are simultaneously activated by Wnts in colon cancer cells. Cell Signal 2020, 72, 109636. [CrossRef]

- Mikels, A. J.; Nusse, R., Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol 2006, 4, e115. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, H.; Xu, L.; Huang, C.; Tong, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Z., Single-cell and spatial transcriptome profiling reveal CTHRC1+ fibroblasts promote EMT through WNT5A signaling in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 282. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).