Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anatomy and Pathophysiology of Disc Herniations

3. Radiological Stages of Disc Herniations

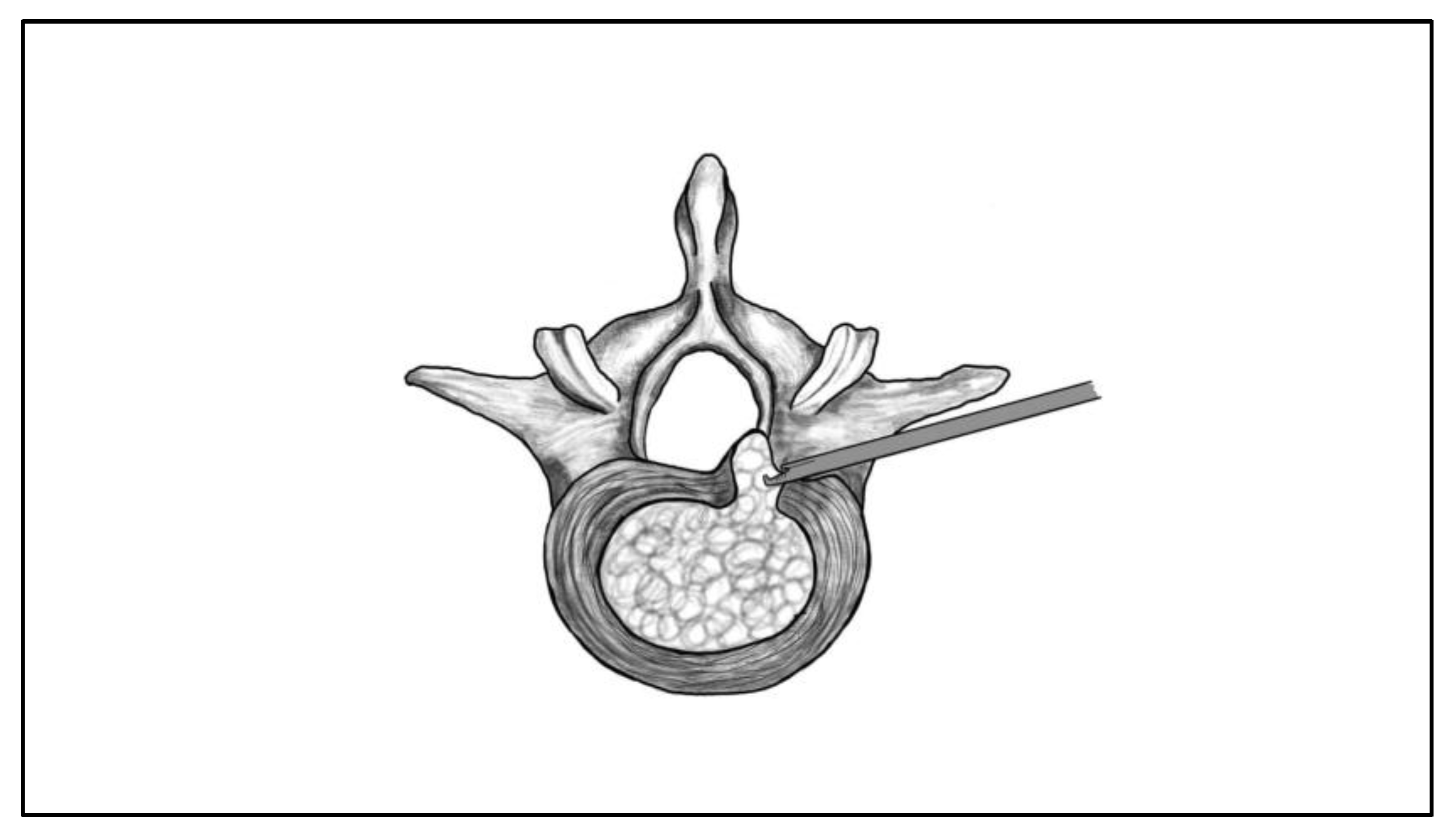

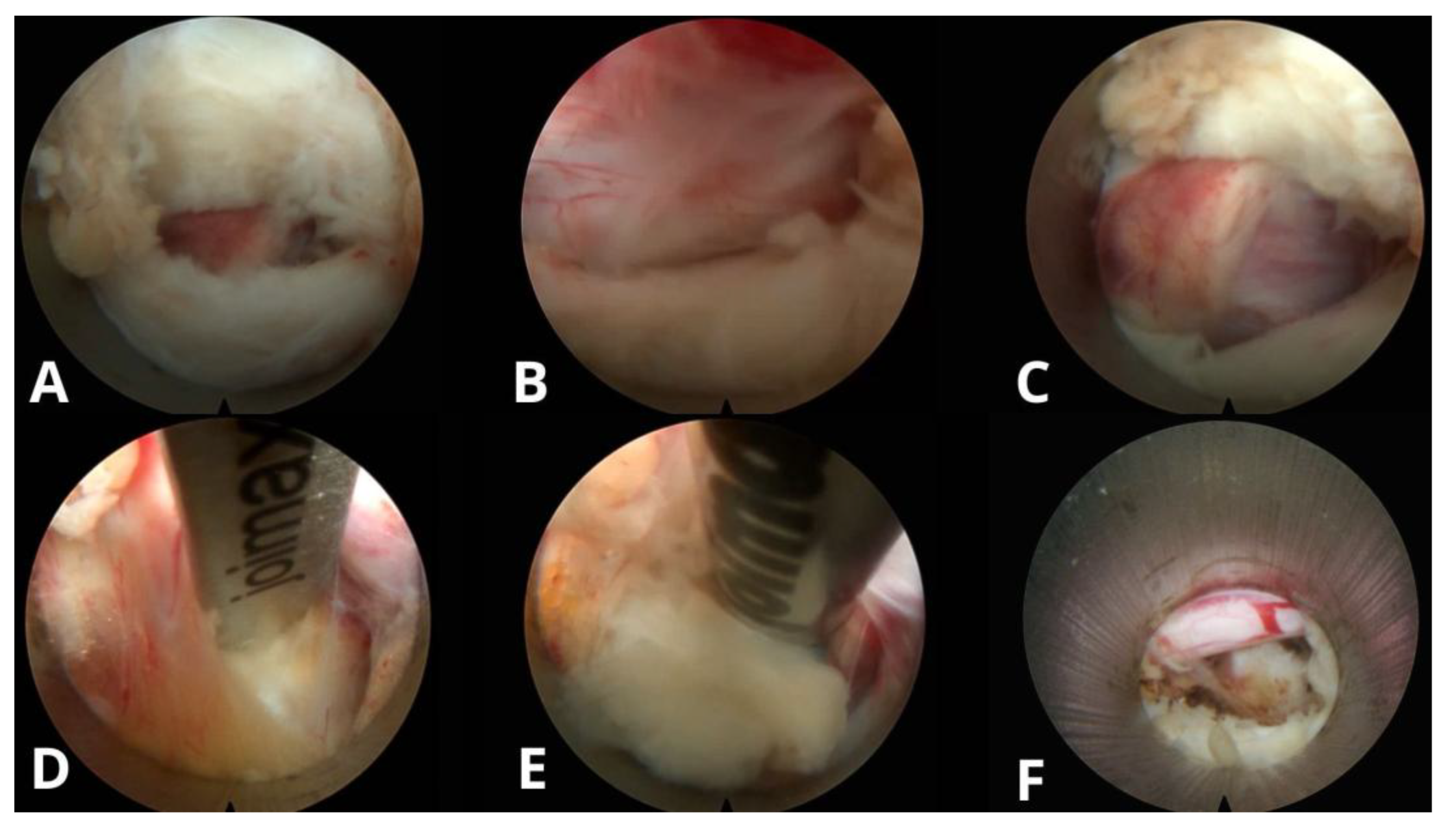

4. Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

General Overview

Surgical Technique and Anatomical Landmarks

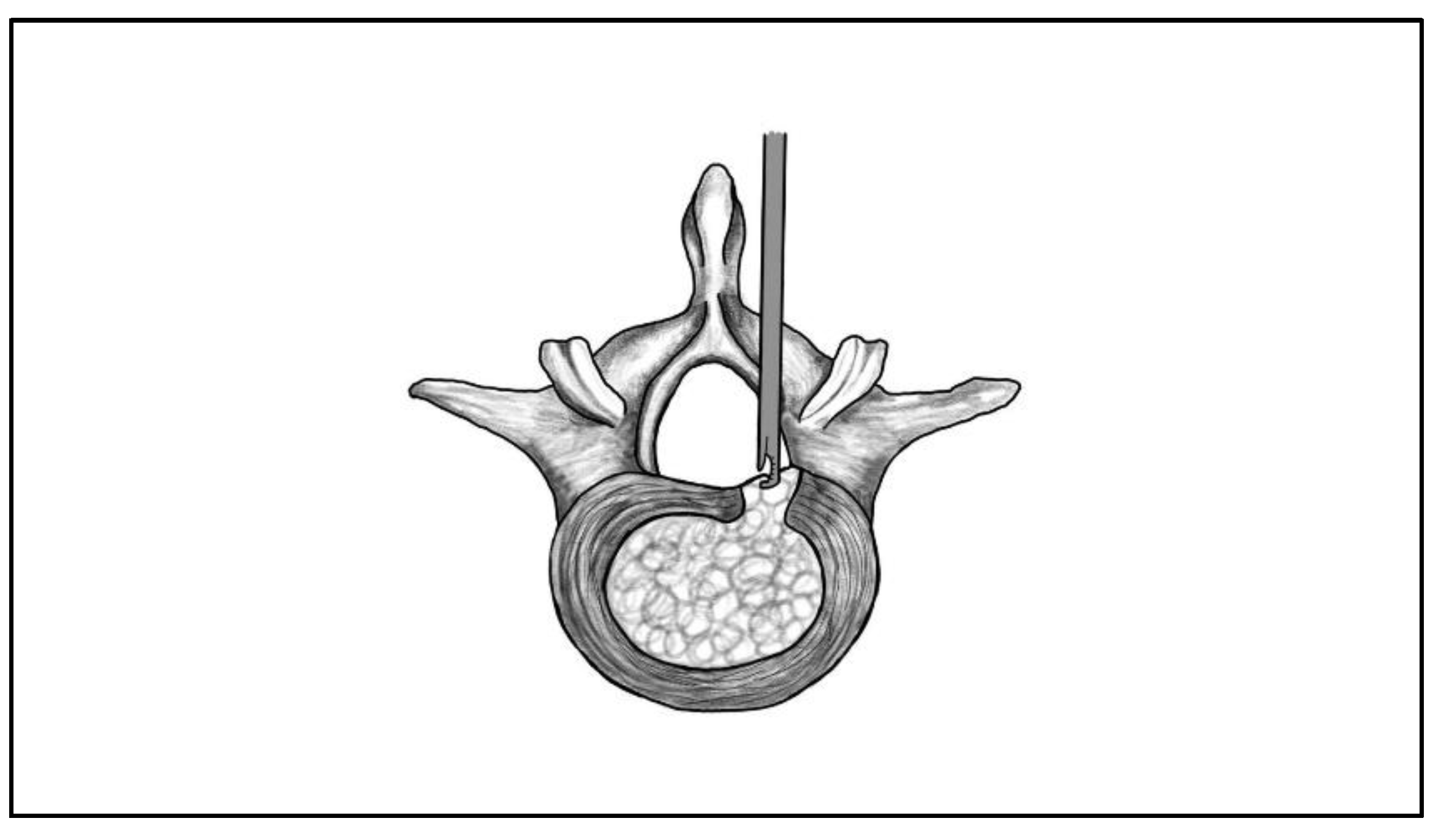

5. Interlaminar Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

General Overview

Surgical Technique and Anatomical Landmarks

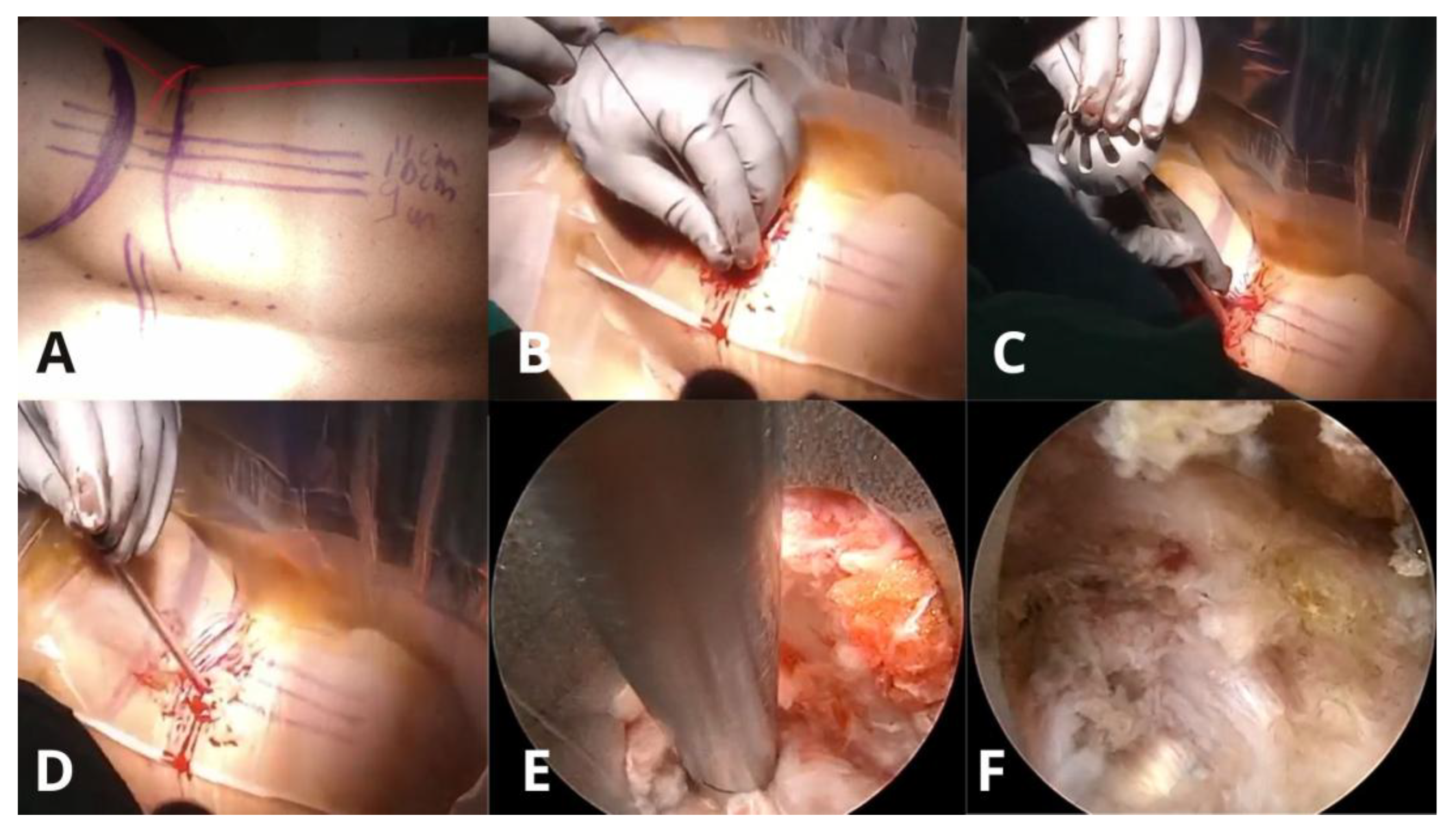

6. Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

General Overview

Surgical Technique and Anatomical Landmarks

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, M.; Theologis, A.A.; O’Connell, G.D. Understanding the Etiopathogenesis of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Herniation: From Clinical Evidence to Basic Scientific Research. JOR Spine 2024, 7, e1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.Y.; Shan, H.; Liu, T.F.; Zhang, Z.C.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, Y.Z. Emerging Issues Questioning the Current Treatment Strategies for Lumbar Disc Herniation. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 814531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, T.J.; Munakomi, S.; Dowling, T.J. Microdiscectomy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555984/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Burkett, D.; Brooks, N. Advances and Challenges of Endoscopic Spine Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, C.P.; Ahn, Y.; Choi, G.; Gibson, J.N.; Ruetten, S.; Zhou, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Yeung, A.; Telfeian, A.E.; Wagner, R. AOSpine Consensus Paper on Nomenclature for Working-Channel Endoscopic Spinal Procedures. Glob. Spine J. 2020, 10 (Suppl. 2), 111S–121S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, P.P. Intervertebral Disc: Anatomy–Physiology–Pathophysiology–Treatment. Pain Pract. 2008, 8(1), 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, M.; Choucha, A.; Ciaglia, E.; Varrassi, G.; Pergolizzi, J.; Paladini, A. Discogenic Low Back Pain: Anatomic and Pathophysiologic Characterization, Clinical Evaluation, Biomarkers, AI, and Treatment Options. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(19), 5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Hutton, W.C. The Mechanical Function of the Lumbar Apophyseal Joints. Spine 1983, 8(3), 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkantsinikoudis, N.; Kapetanakis, S.; Magras, I.; Tsiridis, E.; Kritis, A. Tissue Engineering of Human Intervertebral Disc: A Concise Review. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2022, 28(4), 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogduk, N. The Innervation of the Lumbar Spine. Spine 1983, 8, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freemont, A.J.; Peacock, T.E.; Goupille, P.; Hoyland, J.A.; O’Brien, J.; Jayson, M.I. Nerve Ingrowth into Diseased Intervertebral Disc in Chronic Back Pain. Lancet 1997, 350, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, G.D.; Guyre, C.A.; Vaccaro, A.R. The Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Lumbar Disc Herniations. Semin. Spine Surg. 2016, 28(1), 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, H.; Morio, Y.; Yamane, K.; Nanjo, Y.; Teshima, R. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha, Interleukin-1Beta, and Interleukin-6 in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Cervical Myelopathy and Lumbar Radiculopathy. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 1946–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamide, A.; Hashizume, H.; Yoshida, M.; Kawakami, M.; Hayashi, N.; Tamaki, T. Effects of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor on Spontaneous Resorption of Herniated Intervertebral Discs: An Experimental Study in the Rabbit. Spine 1999, 24(10), 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Kim, J.E.; Yoo, B.R.; Jeong, Y.M. A New Grading System for Migrated Lumbar Disc Herniation on Sagittal Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An Agreement Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11(7), 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardon, D.F.; Williams, A.L.; Dohring, E.J.; Murtagh, F.R.; Rothman, S.L.G.; Sze, G.K. Lumbar Disc Nomenclature: Version 2.0: Recommendations of the Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine 2014, 39(24), E1448–E1465. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Haefner, M. Indications and Contraindications of Full-Endoscopic Interlaminar Lumbar Decompression. World Neurosurg. 2021, 145, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Tao, J.; Yang, C. Efficacy and Safety of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy Compared with Transforaminal Route Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Decompression in the Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Minimum 1-Year Follow-Up. J. Pain Res. 2025, 18, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, D.; Gülsever, C.İ.; Özata, M.S.; Uysal, İ.Y.; Aydoseli, A.; Aras, Y. Full Endoscopic Interlaminar Approach for Paracentral L5–S1 Disc Herniation. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, (194), 64717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Isseldyk, F.; Padilla-Lichtenberger, F.; Guiroy, A.; Szmuda, T.; Gagliardi, M.; Kochanski, R.B.; López, W.; Fiani, B. Endoscopic Treatment of Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease: A Narrative Review of Full-Endoscopic and Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2024, 188, e93–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanakis, S.; Chaniotakis, C.; Tsioulas, P.; Gkantsinikoudis, N. Transforaminal Lumbar Endoscopic Discectomy: A Novel Alternative for Management of Lumbar Disc Herniation in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis? Neurospine 2024, 21(4), 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsever, C.İ.; Şahin, D.; Ortahisar, E.; Erguven, M.; Sabancı, P.A.; Aras, Y. Full-Endoscopic Transforaminal Approach for Lumbar Discectomy. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, (199). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.W.; Chen, C.D.; Zhan, B.S.; Wang, Y.L.; Tang, P.; Jiang, X.S. Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Discectomy versus Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy in the Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Retrospective Study. J. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 17(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.; Lewandrowski, K.U. Five-Year Clinical Outcomes with Endoscopic Transforaminal Foraminoplasty for Symptomatic Degenerative Conditions of the Lumbar Spine: A Comparative Study of Inside-Out versus Outside-In Techniques. J. Spine Surg. 2020, 6 (Suppl. 1), S66–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, J.P.M.; De Oliveira Teixeira, K.; Soares, T.Q.; Almeida, J.P.; Garcia, A.C.; Linhares, M.N.; Faccioni, W.J. Extraforaminal Full-Endoscopic Approach for the Treatment of Lateral Compressive Diseases of the Lumbar Spine. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13(3), 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanakis, S.; Gkantsinikoudis, N. Modified Transforaminal Lumbar Endoscopic Discectomy for Surgical Management of Extraforaminal Lumbar Disc Herniation: Case Series and Technical Note. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2025, 42(1), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ren, L.; Ye, Q.; Wu, M.; Wang, G.; Guo, J. Endoscopic and Microscopic Interlaminar Discectomy for the Treatment of Far-Migrated Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Retrospective Study with a 24-Month Follow-Up. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Jang, I.T.; Kim, W.K. Transforaminal Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy for Very High-Grade Migrated Disc Herniation. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 147, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, C.T.; Chen, K.T.; Jhang, S.W.; Lin, C.W.; Tsai, C.H.; Huang, K.Y.; Lin, Y.J. Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy with Foraminoplasty for Down-Migrated Disc Herniation: A Single-Center Observational Study. J. Minim. Invasive Spine Surg. Tech. 2022, 7(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depauw, P.R.A.M.; Gadjradj, P.S.; Soria van Hoeve, J.S.; Harhangi, B.S. How I Do It: Percutaneous Transforaminal Endoscopic Discectomy for Lumbar Disk Herniation. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2018, 160(12), 2473–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.G.; Ahn, Y. Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Basic Concepts and Technical Keys to Clinical Success. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2021, 15 (Suppl. 3), S38–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, N.; Yuan, S.; Du, P.; Wei, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lu, H.; Gao, T. Complications and Risk Factors of Percutaneous Endoscopic Transforaminal Discectomy in the Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22(1), 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillo-Olvera, J.; Quillo-Reséndiz, J.; Barrera-Arreola, M. Common Complications with Endoscopic Surgery and Management. Semin. Spine Surg. 2024, 36(1), 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.I.; Kim, P.; Ha, S.W.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.M. Contraindications and Complications of Full Endoscopic Lumbar Decompression for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2022, 168, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.P.; Olson, T.; Gabriel, B.; Rosinski, A.; Elsamadicy, A.; Mallow, G.; et al. What Is the Learning Curve for Endoscopic Spine Surgery? A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Spine J. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleiderman, V.J.; Lecaros, B.J.; Cirillo, T.J.I.; Álvarez Lemos, F.; Osorio, V.P.; Wolff, B.N. Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Learning Curve of a Single Surgeon. J. Spine Surg. 2023, 9(2), 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.I.; Yuh, W.T.; Kwon, S.W.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.T.; Lee, S.G. Interlaminar Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2021, 15 (Suppl. 3), S47–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Murillo, M.; Castro-Toral, J.; Casal-Grau, R.; Bonome-Roel, C.; Bonome-González, C.; De Mon-Montoliú, J.Á. Technical Considerations and Avoiding Complications in Interlaminar Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. J. Minim. Invasive Spine Surg. Tech. 2024, 9 (Suppl. 2), S136–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Choi, M.; Ryu, D.S.; Choi, I.; Kim, C.H.; Jung, S.K.; Sohn, M.J. Efficacy and Safety of Full-Endoscopic Decompression via Interlaminar Approach for Central or Lateral Recess Spinal Stenosis of the Lumbar Spine: A Meta-Analysis. Spine 2018, 43(24), 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaleddine, Y.; Haj Hussein, A.; Honeine, M.O.; El Masri, J.; Khoury, J.; Haidar, R.; Haidar, H. Evaluating the Learning Curve and Operative Time of Interlaminar and Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. Brain Spine 2025, 5, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.H.; Booker, J.; Choi, D.; Lin, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Smith, N.; et al. Learning Curve of Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant and Aggregated Data. Glob. Spine J. 2025, 15(2), 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, J.Y.; Park, J.Y. Essential Surgical Techniques during Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Spine Surg. Tech. 2023, 8(2), 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcu, C. Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy for Non-Migrated Lumbar Disc Herniation. In Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy of the Spine; Quillo-Olvera, J., Quillo-Olvera, D., Quillo-Reséndiz, J., Mayer, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.M. Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery (BESS): Considering Merits and Pitfalls. J. Spine Surg. 2020, 6(2), 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Li, Q.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, H.; Xu, J.; Li, X. Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Indications and Complications. Pain Physician 2020, 23(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lin, R.; Fang, D.; He, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Q. Learning Curve Insights in Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic (UBE) Spinal Procedures: Proficiency Cutoffs and the Impact on Efficiency and Complications. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 34(3), 954–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; et al. Learning Curve and Complications of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy: Cumulative Sum and Risk-Adjusted Cumulative Sum Analysis. Neurospine 2022, 19(3), 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, K.U. The Strategies behind “Inside-Out” and “Outside-In” Endoscopy of the Lumbar Spine: Treating the Pain Generator. J. Spine Surg. 2020, 6 (Suppl. 1), S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambin, P.; Casey, K.; O’Brien, E.; Zhou, L. Transforaminal Arthroscopic Decompression of Lateral Recess Stenosis. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 84(3), 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijikata, S. Percutaneous Nucleotomy: A New Concept Technique and 12 Years’ Experience. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, (238), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruetten, S.; Komp, M.; Godolias, G. A New Full-Endoscopic Technique for the Interlaminar Operation of Lumbar Disc Herniations Using 6-mm Endoscopes: Prospective 2-Year Results of 331 Patients. Minim. Invasive Neurosurg. 2006, 49(2), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.M. A History of Endoscopic Lumbar Spine Surgery: What Have We Learnt? Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 4583943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwa Eum, J.; Hwa Heo, D.; Son, S.K.; Park, C.K. Percutaneous Biportal Endoscopic Decompression for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Technical Note and Preliminary Clinical Results. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 24(4), 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.M.; Chung, J.T.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, D.J. How I Do It? Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2016, 158(3), 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Liang, Z.; Han, T.; Lu, H.; Hou, Z. Bibliometric and Visualization Analysis of Research Hotspots and Frontiers in Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 2165–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitpakdee, K.; Liu, Y.; Heo, D.H.; Kotheeranurak, V.; Suvithayasiri, S.; Kim, J.S. Minimally Invasive Endoscopy in Spine Surgery: Where Are We Now? Spine J. 2023, 32(8), 2755–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Antoni, D.J.; Claro, M.L.; Poehling, G.G.; Hughes, S.S. Translaminar Lumbar Epidural Endoscopy: Anatomy, Technique, and Indications. Arthroscopy 1996, 12(3), 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

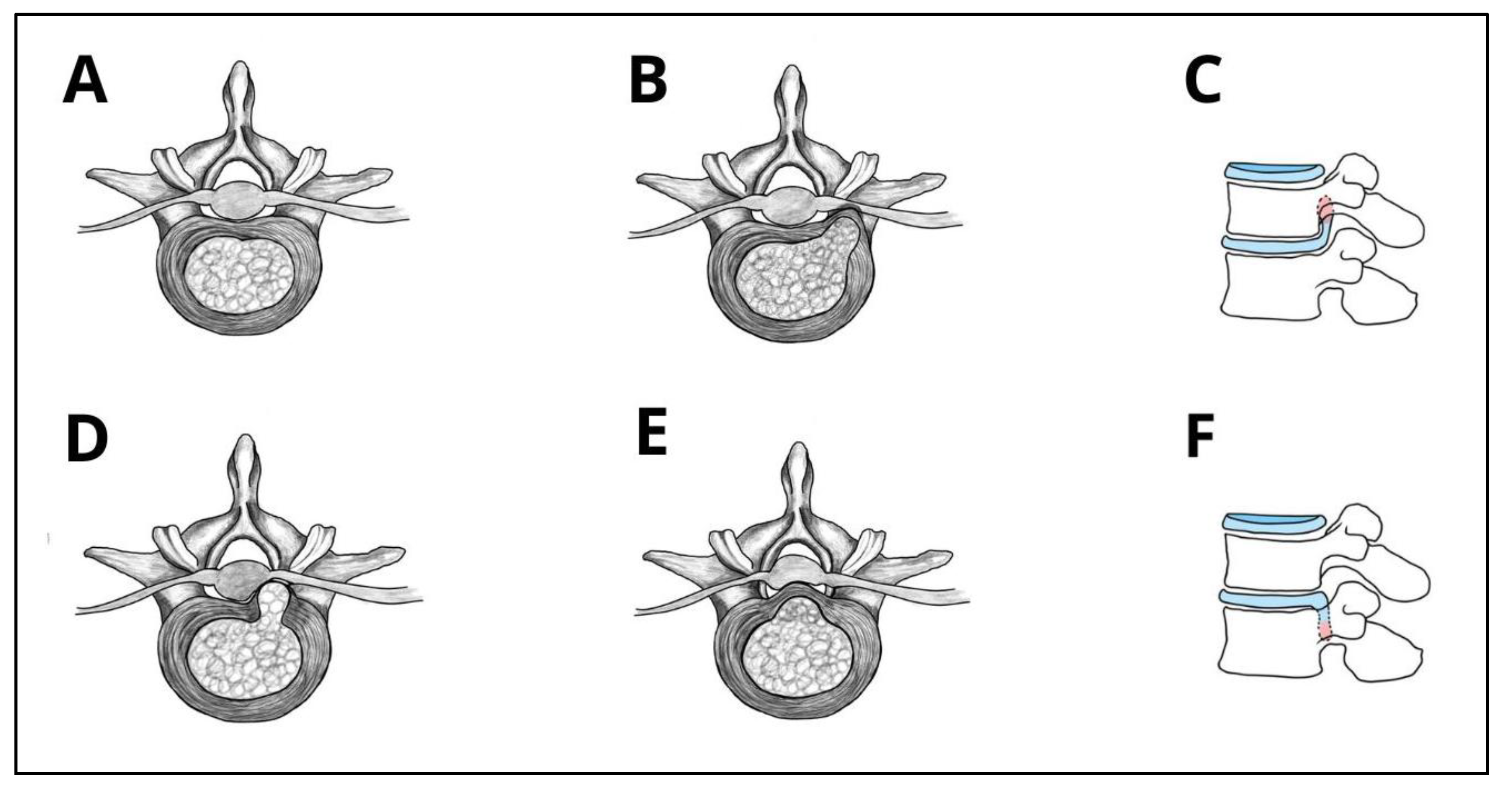

| Morphological Type | Definition | Clinical Considerations |

| Protrusion | Localized displacement where the width of herniation is smaller than the width of the base at the disc margin | Often asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic; usually responds well to conservative treatment; persistent bulging may lead to poorer conservative outcomes in some cases |

| Extrusion (contained) | Displaced portion of NP material with a narrower base than its displaced portion extends beyond AF, but remains covered by AF or PLL | Symptomatic cases could benefit from endoscopic decompression, as persistent bulging often leads to poor response to conservative treatment; however, if nerve compression is minimal, observation may still be appropriate. |

| Extrusion (uncontained) | Displaced portion of NP material with a narrower base than its displaced portion extends beyond AF, but remains covered by AF or PLL | Exposure causes higher inflammatory response, causing radiculopathy; usually responsive to surgical intervention. |

| Sequestration | Free NP fragment displaced from extrusion site and completely separated from disc, might migrate cranially/caudally | High surgical indication due to fragment migrations and acute symptoms; localization is important in surgical planning; spontaneous resorption typically occurs within 6–12 weeks. Follow-up MRI may show resolution, but residual pain may persist due to inflammatory response to NP exposure. |

| Anatomical Location | Preferred Endoscopic Approach | Surgical Insights & Notes |

| Central | Interlaminar [17]; UBE-LD [18] | Especially effective at L4–L5 and L5–S1, due to wider interlaminar window; Allows preservation of posterior elements, such as facet joints and lamina [17]; UBE provides bigger working space and has bilateral decompression capabilities [18]. The same applies to IELD, but in experienced hands. |

| Paracentral | Interlaminar [19]; Transforaminal [20,21,22]; UBE-LD [18,23] | Interlaminar approach is often preferred at L5-S1 due to high iliac crest [19]; The traversing nerve root is usually compressed, so precise decompression is critical to avoid residual symptoms; Annular modulation or foraminoplasty is rarely required; UBE is effective for paracentral herniations, including at L5–S1, where narrow foraminal access may limit transforaminal approaches [18,23]. |

| Foraminal | Transforaminal with foraminoplasty [24]; Modified Transforaminal [25]; Paraspinal or contralateral UBE-LD [23] | The transforaminal inside-out technique allows early intradiscal access, outside-in technique is more effective for severe foraminal stenosis and allows for more extensive bone resection [24]; Foraminoplasty allows for direct visualization of the entire neuroforamen, including the “hidden zone of Macnab” [24]; extraforaminal approach used when pathology lies lateral to facet joint [25]. |

| Extraforaminal (Far-Lateral) | Modified Transforaminal [25,26]; | Allows preservation of posterior elements, such as facet joints and lamina; Technically demanding due to limited working space and proximity to dorsal root ganglion [25]. |

| Cranially Migrated | Interlaminar [27]; Transforaminal [28]; UBE-LD [23] | Performing a foraminotomy is usually indicated in transforaminal approach [28]; calcified disc could convert to bone resection or open surgery; UBE accesses cranially migrated herniations not reachable with TELD [23]. |

| Caudally Migrated | Interlaminar [27]; Transforaminal [29]; UBE-LD [23] | Performing a foraminotomy is usually indicated in transforaminal approach; calcified disc could convert to bone resection or open surgery [23]. |

| Approach | Technique Types | First Surgery | Geographic Trends |

| Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy (TELD) | Inside-out & Outside-in [48] | Concept by Kambin (1973) [49]; first surgery by Hijikata (1975) [50] | Not specific to one approach, bibliometric analyses of FELD research show that China, South Korea, and the United States dominate the field, with over 80% of published studies [55]. |

| Interlaminar Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy (IELD) | Single Technique with minor variations: Direct-Posterior, Translaminar&Axillary/Shoulder [37,38] | First described as open interlaminar discectomy, adapted to full-endoscopic by Ruetten et al. (2006) [51,52] | Not specific to one approach, bibliometric analyses of FELD research show that China, South Korea, and the United States dominate the field, with over 80% of published studies [55]. |

| Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy (UBE-LD) | Interlaminar, Contralateral&Paraspinal [42] | Concept by De Antoni et al. (1996) [57]; modern biportal technique first defined by Choi et al. & Eum et al. (2016) [53,54] | Primarily developed and studied in South Korea (82.4% of publications); top 10 most-cited UBE articles are all from South Korea [56]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).