1. Introduction

The unilateral biportal endoscopic (UBE) technique has recently gained significant popularity. This minimally invasive technique is a revolutionary endoscopic approach performed through two independent portals, with continuous saline irrigation that provides hydrostatic pressure to suppress bleeding and wash away bone debris and oozing. Combined with a high-resolution endoscopic system, UBE delivers a clear, bright, magnified, and bloodless surgical field, allowing surgeons to conduct delicate procedures with minimal collateral soft tissue damage. The UBE technique has been applied to various spinal procedures, including discectomy for lumbar disc herniation, laminotomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis, lumbar interbody fusion for disc degeneration or spondylolisthesis, and posterior cervical foraminotomy for cervical foramen stenosis, all of which demonstrate good clinical efficacy and satisfactory outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

The most common complication of UBE surgery is incidental dural tears, followed by epidural hematoma and incomplete decompression [

8]. Most studies claim that dural tears in endoscopic spine surgeries are typically small and can be managed successfully with conservative measures [

9,

10]. However, this should not be taken for granted. The learning curve should not be an excuse [

11,

12,

13]. Although practice might make perfect, understanding the injury mechanism and modifying surgical techniques to avoid such complications in our daily practice should be a more effective solution. Many articles in the literature have proposed novel techniques to repair dural tears under the endoscope. In contrast, only one study attempted to avoid neural injuries by modifying surgical instruments and techniques [

14].

The Kerrison punch has been used as the most crucial surgical instrument for neural decompression in modern spine surgery. Based on our experience of more than 4000 cases of minimally invasive spine surgeries, we have observed that the Kerrison punch is the most offending surgical instrument, leading to dural tears or nerve root injuries. Therefore, we propose the “no-punch” technique for UBE surgeries, emphasizing two principles: 1. Utilize high-speed drills and curved chisels to replace the Kerrison punch for neural decompression. 2. Undercut the facet joint to remove the ligamentum flavum in whole or large pieces, along with bone chips from the periphery. The “no-punch” technique ensures effective decompression and preservation of the facet joint. Most importantly, the incidence of dural tears or nerve root injuries is very low [

15].

The goal of this comparative study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the “no-punch” technique in reducing the complication rate in UBE surgeries for extended surgical indications of degenerative spinal disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from our institute’s Research Ethics Review Committee. This retrospective study recruited 914 consecutive patients with various degenerative spine disorders who underwent UBE surgery from October 2018 to July 2023. The patients were divided into the Punch Group, which included 660 former patients (830 segments) who underwent UBE surgeries using the conventional technique with Kerrison punches as the principal decompression instrument, and the No-Punch Group, which comprised 254 later patients (330 segments) who underwent UBE surgeries utilizing the “no-punch technique.”

The study included patients with refractory low back pain, radicular leg pain, single or multiple lumbar radiculopathies, and neurogenic intermittent claudication due to various degenerative lumbar spine disorders such as lumbar disc herniation, degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, and degenerative scoliosis. We also included patients with cervical radiculopathy resulting from disc herniation or degenerative foraminal stenosis. Patients who had undergone lumbar spine surgeries with newly developed pathology or unsatisfactory outcomes were also included. However, patients with infection or neoplasm-related pathology were excluded. Before surgery, patients were encouraged to try conservative treatment for at least three months.

The surgical procedures were tailored to each patient based on their clinical presentation and radiological evaluation. These procedures included lumbar discectomy, lumbar canal decompression, lumbar interbody fusion, lumbar foramen decompression, posterior cervical foraminotomy, and revision surgery. All these procedures were performed using the UBE technique.

2.2. Surgical Techniques

In the Punch Group, the Kerrison punch was the primary surgical instrument for resecting the lamina and excising the ligamentum flavum during UBE surgeries. The decompression technique was the same as in traditional open, microscopic, or microendoscopic techniques. The ligamentum flavum was excised in small pieces from the central area to the periphery using the Kerrison punches.

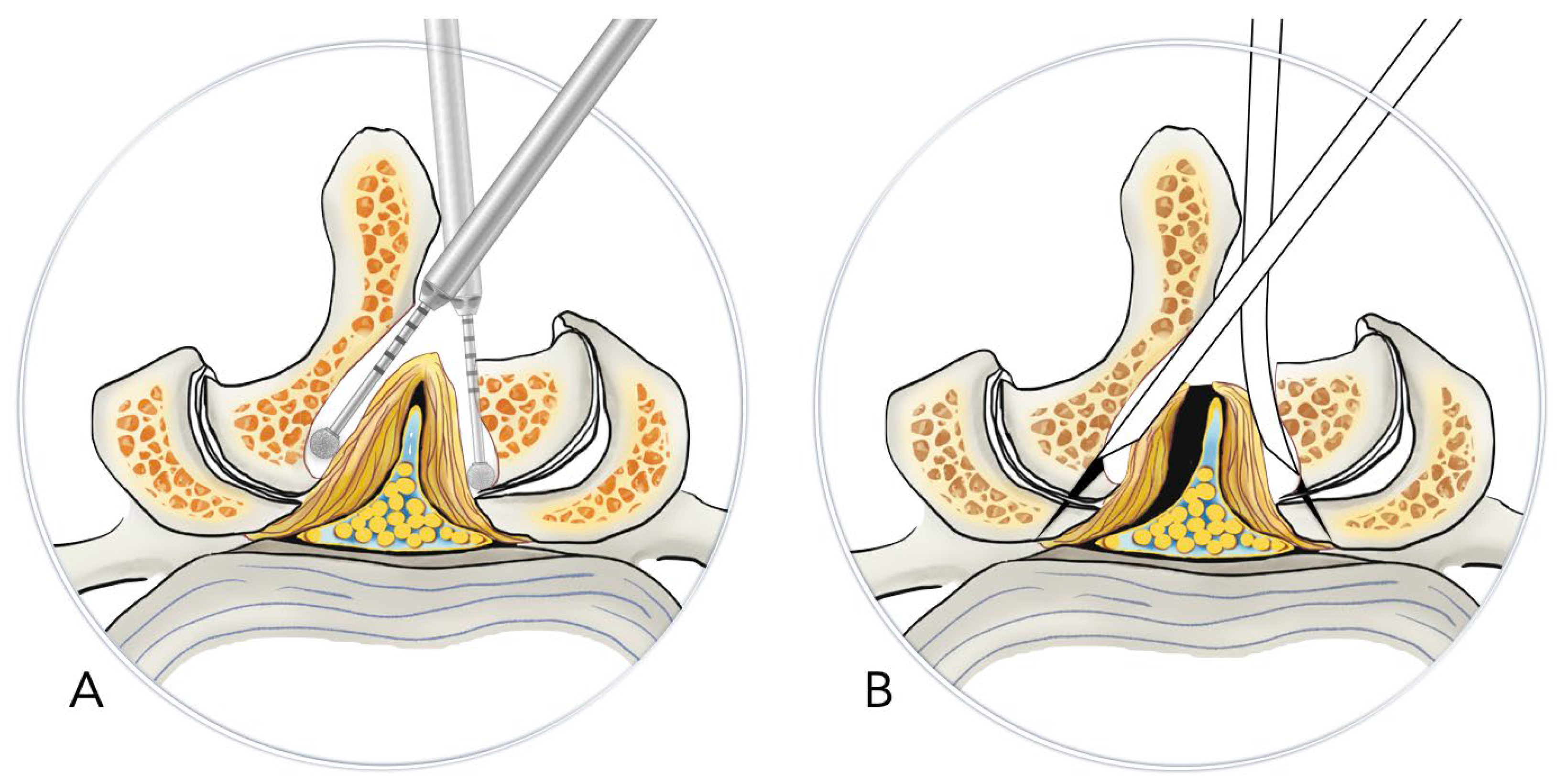

In the No-Punch Group, we used high-speed drills, curved chisels, and pituitary rongeurs as the primary decompression instruments to substitute for the Kerrison punch. Following the initial laminotomy performed by drilling, we exposed the facet joint’s medial margin and the ligamentum flavum’s insertion site. We used straight or curved chisels to undercut the insertion site. After detaching the ligamentum flavum with straight and angled curettes, we removed it as a whole or in large pieces after releasing the underlying epidural adhesion. Unlike the conventional technique, we preserved the ligamentum flavum until the end of the decompression process, where it was removed in a peripheral-to-central manner. (

Figure 1)

2.3. Evaluation of Clinical Data and Outcomes

For analysis, demographic data, clinical information, surgical complications, and treatment outcomes were retrieved from chart review. We also reviewed all operation notes and video records to identify possible mechanisms of neural injuries, offending surgical instruments, and the management of surgical complications. All patients had a minimum follow-up of six months after the surgery.

The null hypothesis states that the “no-punch technique” does not reduce the complication rate compared to the conventional technique using Kerrison punches. The incidence of each specific surgical complication was calculated and compared between groups using the Chi-square test. The numerical data were analyzed using the Student t-test, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In the Punch Group, there were 660 patients undergoing 830 segments of UBE surgeries, which included 294 male and 366 female patients, with an average age of 65.4 ± 12.1 years (ranging from 20 to 92). In the No-Punch Group, there were 254 patients undergoing 330 segments of UBE surgeries, comprising 111 male and 143 female patients, with an average age of 64.4 ± 12.0 years (ranging from 24 to 88). There was no significant difference in gender or age between the groups. The demographic data and distribution of specific surgical procedures performed in each group are summarized in

Table 1.

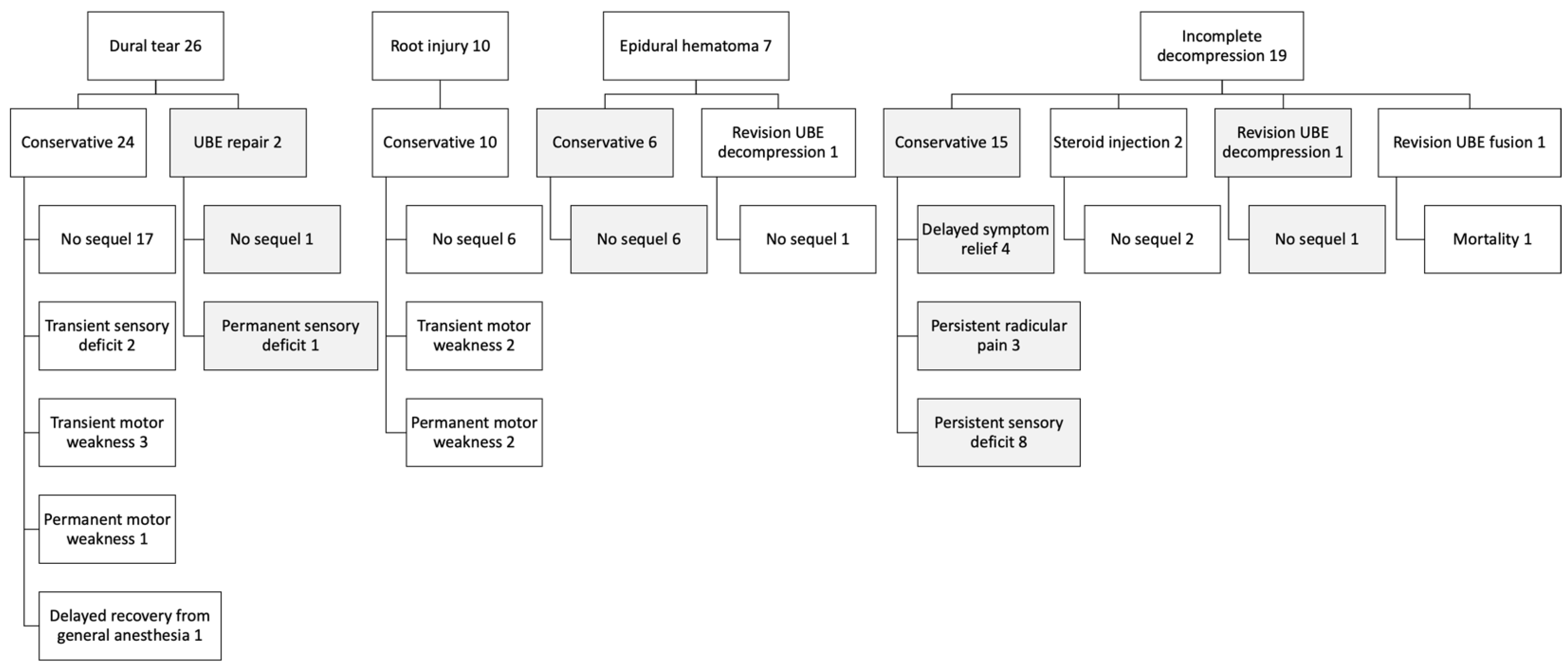

There were 63 surgical complications, including incidental dural tears, nerve root injuries, incomplete decompression, epidural hematoma, and broken instruments. Among these, there were 26 dural tears. Most dural tears were small and treated conservatively without direct repair. A gelatin patch covering the dural defect was usually sufficient to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Direct repair under the endoscope was performed in two patients with dural tears larger than 6 mm. Most patients with dural tears experienced no sequelae by the final follow-up. However, one patient had a permanent sensory deficit, while another had a permanent motor weakness.

We had 10 cases of nerve root injuries, all treated conservatively; however, two resulted in permanent motor weakness. An epidural hematoma was identified in 7 patients, with no sequelae following conservative treatment or revision UBE decompression. Nineteen patients experienced incomplete decompression; among them, 3 had persistent radicular leg pain, 8 had a permanent sensory deficit, and one died from a cardiovascular event after revision UBE fusion surgery. The management and outcomes of these complications are summarized in

Figure 2.

The most common complications were dural tears, followed by incomplete decompression, nerve root injury, epidural hematoma, and broken instruments. The overall complication rate and incidence of dural tears were significantly lower in the No-Punch Group (8.8% vs. 2.0%,

p < 0.001, and 3.9% vs. 0%,

p = 0.001) (

Table 2).

In the Punch Group, revision surgery had the highest incidence of neural injury (9.9%, including dural tears and nerve root injuries), followed by posterior cervical foraminotomy (7.7%), lumbar decompression (5.0%), and lumbar interbody fusion (2.2%). However, the incidence of neural injuries was significantly lower in the No-Punch Group (5.3% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.001), particularly in lumbar decompression (5.0% vs. 0.8%, p = 0.017) and revision surgeries (9.9% vs. 0%, p = 0.038). The most offending surgical instrument associated with neural injury is the Kerrison punch, which accounted for 32 out of 35 such complications (91.4%). In the No-Punch Group, only one nerve root injury was caused by the radiofrequency wand.

The incidence of incomplete decompression and epidural hematoma and their distribution among specific surgical procedures did not differ significantly between groups.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| |

Punch |

No-Punch |

p-value

|

| Patients |

660 |

254 |

|

| Male |

294 |

111 |

0.82* |

| Female |

366 |

143 |

|

| Mean age |

65.4±12.1 |

64.4±12.0 |

0.42* |

| Age range |

20 ~ 92 |

24 ~ 88 |

|

| Segments |

830 |

330 |

|

| Procedures |

|

|

|

| Lumbar canal decompression |

237 |

73 |

|

| Lumbar interbody fusion |

137 |

87 |

|

| Lumbar discectomy |

116 |

42 |

|

| Lumbar foramen decompression |

46 |

16 |

|

| Posterior cervical foraminotomy |

13 |

10 |

|

| Revision surgery |

111 |

26 |

|

Table 2.

Comparison of complications between groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of complications between groups.

| |

All |

Punch |

No-Punch |

p-value* |

| |

Patient |

% |

Patient |

% |

Patient |

% |

|

| Dural tears |

26 |

2.8% |

26 |

3.9% |

0 |

0.0% |

0.001 |

| Nerve root injuries |

10 |

1.1% |

9 |

1.4% |

1 |

0.4% |

0.207 |

| Incomplete decompression |

19 |

2.1% |

16 |

2.4% |

3 |

1.2% |

0.238 |

| Epidural hematoma |

7 |

0.8% |

6 |

0.9% |

1 |

0.4% |

0.423 |

| Broken instruments |

1 |

0.1% |

1 |

0.2% |

0 |

0.0% |

0.535 |

| Total |

63 |

6.9% |

58 |

8.8% |

5 |

2.0% |

< 0.001 |

Table 3.

Distribution and comparison of neural injuries and offending instruments in subcategories of surgical procedures between groups.

Table 3.

Distribution and comparison of neural injuries and offending instruments in subcategories of surgical procedures between groups.

| |

Punch |

No-Punch |

|

| |

Patient |

Dural tear |

Root injury |

Neural injury |

Patient |

Dural tear |

Root injury |

Neural injury |

|

| |

(n) |

(A) |

(B) |

(A+B) |

% |

(n) |

(A) |

(B) |

(A+B) |

% |

p-value |

| Procedures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lumbar decompression* |

399 |

13 |

7 |

20 |

5.0% |

131 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0.8% |

0.017 |

| Canal decompression |

237 |

12 |

3 |

15 |

6.3% |

73 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1.4% |

0.052 |

| Foramen decompression |

46 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4.3% |

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.380 |

| Discectomy |

116 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

2.6% |

42 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.282 |

| Lumbar interbody fusion |

137 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

2.2% |

87 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.282 |

| Posterior cervical foraminotomy |

13 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7.7% |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.535 |

| Revision surgery |

111 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

9.9% |

26 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.038 |

| Total |

660 |

26 |

9 |

35 |

5.3% |

254 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0.4% |

0.001 |

| Offending Instruments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kerrison punch |

660 |

25 |

7 |

32 |

4.8% |

254 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

| Radiofrequency wand |

660 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

0.5% |

254 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0.4% |

|

| Pituitary rongeur |

660 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0% |

254 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0% |

|

Table 4.

Distribution and comparison of epidural hematoma and incomplete decompression in subcategories of surgical procedures between groups.

Table 4.

Distribution and comparison of epidural hematoma and incomplete decompression in subcategories of surgical procedures between groups.

| |

Punch |

No-Punch |

|

| |

Patient |

Occurrence |

% |

Patient |

Occurrence |

% |

p-value* |

| Incomplete decompression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lumbar canal decompression |

237 |

4 |

1.7% |

73 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.214 |

| Lumbar foramen decompression |

46 |

1 |

2.2% |

16 |

2 |

4.3% |

0.132 |

| Lumbar discectomy |

116 |

1 |

0.9% |

42 |

1 |

0.9% |

0.483 |

| Lumbar interbody fusion |

137 |

0 |

0.0% |

87 |

0 |

0.0% |

- |

| Posterior cervical foraminotomy |

13 |

1 |

7.7% |

10 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.535 |

| Revision surgery |

111 |

9 |

8.1% |

26 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.061 |

| Total |

660 |

16 |

2.4% |

254 |

3 |

0.5% |

0.238 |

| Epidural hematoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lumbar canal decompression |

237 |

2 |

0.8% |

73 |

1 |

0.4% |

0.830 |

| Lumbar foramen decompression |

46 |

0 |

0.0% |

16 |

0 |

0.0% |

- |

| Lumbar discectomy |

116 |

1 |

0.9% |

42 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.535 |

| Lumbar interbody fusion |

137 |

3 |

2.2% |

87 |

0 |

0.0% |

0.282 |

| Posterior cervical foraminotomy |

13 |

0 |

0.0% |

10 |

0 |

0.0% |

- |

| Revision surgery |

111 |

0 |

0.0% |

26 |

0 |

0.0% |

- |

| Total |

660 |

6 |

0.9% |

254 |

1 |

0.2% |

0.423 |

4. Discussion

Minimally invasive techniques for spine surgery have been developed for nearly 30 years since Dr. Foley introduced the microendoscopic technique for lumbar discectomy [

16]. This procedure was performed through a tubular retractor system mounted on the surgical table via a flexible arm, with an endoscope attached to the tube or a remote microscope for visualization [

17,

18,

19]. Subsequently, this technique was adapted for various spine procedures to address different pathologies. The treatment outcomes were comparable to those of traditional open surgeries. However, patients benefit from smaller surgical wounds, minimal soft tissue damage, reduced wound pain, and faster recovery [

20,

21,

22].

The advancement of endoscopy technology and surgical instruments has recently enabled most minimally invasive procedures to be performed using endoscopic techniques, resulting in smaller surgical wounds and reduced soft tissue damage [

23,

24,

25,

26]. The Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic (UBE) approach is a revolutionary endoscopic technique with unique features, including a clear and magnified surgical field, the ability to handle instruments with both hands independently, a spacious working environment through a small instrument portal, and the use of familiar tools from traditional open surgery [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

27,

28].

Endoscopic spine surgery is technically challenging and involves a steep learning curve [

11,

12,

13,

29,

30]. This learning process is usually associated with a higher complication rate, extended operation time, and prolonged hospitalization [

10]. Most studies claim that complications in endoscopic spine surgery can be managed conservatively with no severe sequelae. However, potential sequelae from these complications have occurred and should not be overlooked as merely part of the learning curve [

9,

10,

31]. Surgical complications can negatively impact treatment outcomes. In our study, 17 patients experienced permanent sensory deficits, motor weakness, or persistent radicular leg pain due to surgical complications. Preventing complications rather than addressing them after they occur is always preferable. Understanding the mechanisms of injury is essential in preventing their occurrence.

The most common complication in UBE surgery is dural tears [

8,

32]. Besides the direct neural injury, dural tears in UBE surgery raise specific concerns. When a dural tear occurs, saline or air bubbles may enter the cerebrospinal fluid space, potentially causing brain injury by increasing intracranial pressure or by the air bubbles [

33]. Small tears can be covered with fibrin sealant or gelatin patches to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage. If the dural tear is larger than 10 mm, it should be repaired using non-penetrating hemostatic clips or direct sutures as soon as it is noticed [

9,

10,

34,

35]. However, direct repair under the endoscope is highly technically demanding and only feasible in an expert’s hands [

14]. In our study, dural tears were 2.8%, and direct repair under the endoscope was indicated in two patients. All these dural tears occurred in the Punch Group. The treatment outcomes were generally good, although one patient experienced permanent sensory deficits, another had permanent motor weakness, and one had a delayed recovery from general anesthesia.

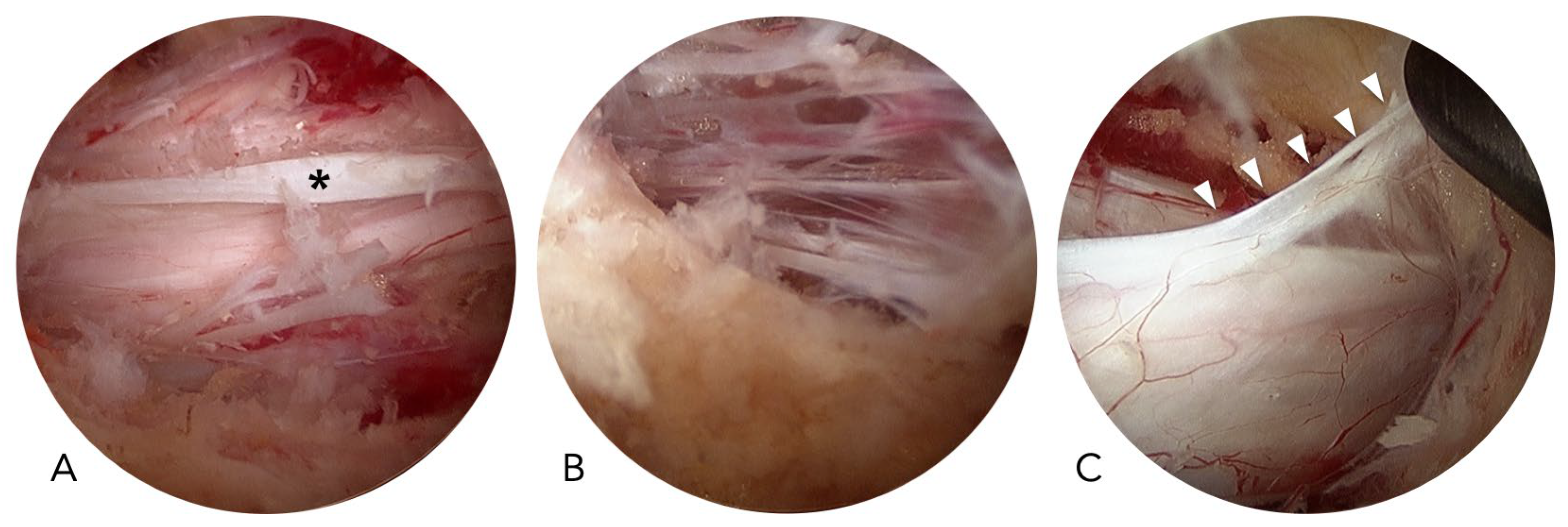

In UBE surgery, dural tears are more frequent in the central areas than in the lateral areas. The central dural folding, epidural adhesion, and the meningovertebral ligament may contribute to the increased risk of dural tears in the central region (

Figure 3). Central dural folding is a unique phenomenon observed only in endoscopic spine surgery using normal saline as the medium. The central dura connects to the ligamentum flavum or the lamina through fibrotic tissue and is covered with epidural fat. When saline enters the epidural space, hydrostatic pressure compresses the dural sac but keeps the central dura tethered by the fibrotic tissues, resulting in central dural folding [

10]. Epidural adhesion is frequently encountered in revision surgeries. However, it also happens in primary cases with severe stenosis. The meningovertebral ligaments are the structures connecting the dura to the ligamentum flavum or lamina, and they can cause dural lacerations if forcefully stretched without special attention [

36,

37].

Kerrison punches are the most crucial surgical instruments for neural decompression. However, they also pose significant risks for dural tears and nerve root injuries [

10]. They are convenient and efficient for resecting the lamina and removing the ligamentum flavum. The ligamentum flavum serves as a natural barrier that protects the dura mater during neural decompression. Nevertheless, this structure must be excised to achieve adequate neural decompression. Traditionally, the surgeon tends to insert the Kerrison punch into the central slit to excise the ligamentum flavum in a central-to-peripheral and piecemeal manner. If the central dural folding, epidural adhesion, or meningovertebral ligament is not appropriately identified, the dura may be inadvertently damaged by the Kerrison punches [

10,

35]. A massive dural tear may occur if the surgeon continuously pulls the ligamentum flavum along with the dura. In our study, the Kerrison punch was responsible for 25 dural tears and seven nerve root injuries, which account for 91% of the total 35 neural injuries in the Punch Group. In contrast, only one nerve root injury caused by the radiofrequency wand occurred in the No-Punch Group. Only one report in the literature has focused on modifying surgical techniques to prevent dural tears [

14]. Using their specially designed dural protectors, Hong et al. effectively prevented dural tears in the nerve root area. However, dural tears still occurred in the central thecal area.

Our “no-punch” decompression technique effectively reduces the risk of dural tears and nerve root injuries by avoiding the previously mentioned injury mechanisms. We abandoned the most dangerous surgical instrument, the Kerrison punch, and performed the decompression in a peripheral-to-central manner, releasing the ligamentum flavum from its periphery and removing the ligamentum flavum in large pieces along with attached laminotomy bone chips. All these modified techniques contribute to the very low incidence of neural injuries. The incidence of dural tears was significantly reduced from 3.9% to 0%. Additionally, the overall incidence of surgical complications was significantly reduced from 8.8% to 2.0%.

When considering various surgical procedures, the overall incidence of neural injury significantly decreased from 5.3% to 0.4%. Neural injuries typically occur more frequently in revision surgery due to epidural adhesive scarring resulting from previous surgeries. However, there were no neural injuries in the revision subgroup of our No-Punch Group. Epidural adhesive scarring is most severe in the central thecal area and least severe in the peripheral area. Our “no-punch technique” uses a high-speed bur to thin the remaining lamina, along with curved chisels or osteotomes to release adhesive scars from the peripheral area, thus avoiding direct manipulation in the central area. This concept is fundamental to our “no-punch technique” for UBE surgery.

The study has several limitations. First, it employs a retrospective study design. Second, the patients in control and experimental groups were not randomly assigned; the grouping criteria were based on the timing of the patient’s surgery. The improved results in the later No-Punch Group may be due to enhanced surgical skills. Finally, the selection of surgical procedures is influenced by each patient’s clinical presentation, which could introduce bias from the surgeon’s judgment and preferences. However, all surgeries were performed by an experienced surgeon with a consistent skill level in the UBE technique before we conducted this study. Therefore, despite these potential biases arising from the study design, we still believe the study is very valuable for evaluating the effectiveness of the “no-punch technique” in preventing complications in UBE surgery.

5. Conclusions

Practice helps surgeons overcome the learning curve, reduces operation time, and improves treatment outcomes. However, avoiding the same mistakes is impossible without thoroughly understanding why and how they occur. This study aims to identify the mechanisms of injury and demonstrate the “no-punch technique” as an effective surgical method for preventing neural injury and lowering the overall complication rate of UBE surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.; methodology, J.P.; validation, J.P. and C.C.; formal analysis, J.P. and C.C.; investigation, J.P. and C.C.; resources, J.P.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, J.P.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, grant number FEMH-2025-C-053.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan (protocol code 113052-E, approved on March 20, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective design.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pao, J.L.; Lin, S.M.; Chen, W.C.; Chang, C.H. Unilateral biportal endoscopic decompression for degenerative lumbar canal stenosis. J Spine Surg 2020, 6, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.J.; Kim, J.E. Efficacy of biportal endoscopic spine surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Surg 2019, 11, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.J.; Kim, J.E.; Jung, J.T.; Kim, Y.S.; Jang, H.J.; Yoo, B.; Kang, I.H. Biportal endoscopic spine surgery for various foraminal lesions at the lumbosacral lesion. Asian Spine J 2018, 12, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eun, S.S.; Eum, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Sabal, L.A. Biportal endoscopic lumbar decompression for lumbar disk herniation and spinal sanal stenosis: a technical note. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2017, 78, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; You, K.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Heo, D.H.; Chung, H.J.; Park, H.J. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion using the biportal endoscopic techniques versus microscopic tubular technique. Spine J 2021, 21, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-S.; Pao, J.-L. Contralateral Inside-out Biportal Endoscopic Posterior Cervical Foraminotomy: Surgical Techniques and Preliminary Clinical Outcomes. J Minim Invasive Spine Surg Tech 2023, 8, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, J.L. Biportal Endoscopic Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using Double Cages: Surgical Techniques and Treatment Outcomes. Neurospine 2023, 20, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.X.; Huang, P.; Kotheeranurak, V.; Park, C.W.; Heo, D.H.; Park, C.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. A Systematic Review of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Spinal Surgery: Preliminary Clinical Results and Complications. World Neurosurg 2019, 125, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, W.; Han, S.; Kang, S.S. Dural Tears in Percutaneous Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery: Anatomical Location and Management. World Neurosurg 2020, 136, e578–e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Choi, D.J.; Park, E.J. Risk Factors and Options of Management for an Incidental Dural Tear in Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery. Asian Spine J 2020, 14, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, G.U.; Choi, M.H.; Chang, B.S.; Lee, C.K.; Yeom, J.S. Learning Curve for Lumbar Decompressive Laminectomy in Biportal Endoscopic Spinal Surgery Using the Cumulative Summation Test for Learning Curve. World Neurosurg 2019, 122, e1007–e1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Yoon, K.J.; Kim, S.W. Percutaneous Endoscopic Decompression in Lumbar Canal and Lateral Recess Stenosis—The Surgical Learning Curve. Neurospine 2019, 16, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.J.; Choi, C.M.; Jung, J.T.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.S. Learning Curve Associated with Complications in Biportal Endoscopic Spinal Surgery: Challenges and Strategies. Asian Spine J 2016, 10, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.H.; Kim, S.K.; Suh, D.W.; Lee, S.C. Novel Instruments for Percutaneous Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery for Full Decompression and Dural Management: A Comparative Analysis. Brain Sci 2020, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pao, J.L. Preliminary Clinical and Radiological Outcomes of the “No-Punch” Decompression Techniques for Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery. Neurospine 2024, 21, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, K.T. Microendoscopic discectomy. Techniques in neurosurgery 1997, 3, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pao, J.L.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, P.Q. Clinical outcomes of microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J 2009, 18, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coric, D.; Adamson, T. Minimally invasive cervical microendoscopic laminoforaminotomy. Neurosurg Focus 2008, 25, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, L.T.; Fessler, R.G. Microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, S146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamide, A.; Yoshida, M.; Simpson, A.K.; Yamada, H.; Hashizume, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Tsutsui, S.; Okada, M.; Takami, M.; et al. Microendoscopic laminotomy versus conventional laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 5-year follow-up study. J Neurosurg Spine 2017, 27, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, K.; Mobbs, R.J. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Laminectomy for Lumbar Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016, 41, E91–E100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, J.L.; Oluwadara Akinduro, O.; Clifton, W.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Abode-Iyamah, K.O. Long-term clinical outcome of minimally invasive versus open single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar diseases: a meta-analysis. Spine J 2021, 21, 2049–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.H.; Lee, D.C.; Park, C.K. Comparative analysis of three types of minimally invasive decompressive surgery for lumbar central stenosis: biportal endoscopy, uniportal endoscopy, and microsurgery. Neurosurg Focus 2019, 46, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranata, R.; Lim, M.A.; Vania, R.; July, J. Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery versus microscopic decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2020, 138, e450–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Z.; Shibayama, M.; Nakamura, S.; Yamada, M.; Kawai, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Yoshimatsu, H.; Kuraishi, K.; Hoshi, N.; Miura, Y.; et al. Clinical comparison of unilateral biportal endoscopic laminectomy versus microendoscopic laminectomy for single-level laminectomy: a single-center, retrospective analysis. World Neurosurg 2021, 148, e581–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, H.; Inanami, H.; Koga, H. Comparative study between full-endoscopic laminectomy and microendoscopic laminectomy for the treatment of lumbar spinal canal stenosis. J Spine Surg 2020, 6, E3–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.H.; Hong, Y.H.; Lee, D.C.; Chung, H.J.; Park, C.K. Technique of biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurospine 2020, 17, S129–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, S.; Lv, H.; He, Y.; Xia, X. Efficacy of Biportal Endoscopic Decompression for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Meta-Analysis With Single-Arm Analysis and Comparative Analysis With Microscopic Decompression and Uniportal Endoscopic Decompression. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2024, 27, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusko, G.D.; Wang, M.Y. Endoscopic Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2020, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Yoshida, M. Assessment of the learning curve for microendoscopic decompression surgery for lumbar spinal canal stenosis through an analysis of 480 cases Involving a single surgeon. Global Spine J 2017, 7, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ham, D.W.; Song, K.S. A Beginner’s Perspective on Biportal Endoscopic Spine Surgery in Single-Level Lumbar Decompression: A Comparative Study with a Microscopic Surgery. Clin Orthop Surg 2023, 15, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.Y.; Upfill-Brown, A.; Curtin, N.; Hamad, C.D.; Shah, A.; Kwon, B.; Kim, Y.H.; Heo, D.H.; Park, C.W.; Sheppard, W.L. Clinical outcomes and complications after biportal endoscopic spine surgery: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 3673 cases. Eur Spine J 2023, 32, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Lin, S.M.; Lan, T.Y.; Pao, J.L. Pneumocephalus with Conscious Disturbance After Full Endoscopic Lumbar Diskectomy. World Neurosurg 2019, 131, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.H.; Ha, J.S.; Lee, D.C.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, H.J. Repair of Incidental Durotomy Using Sutureless Nonpenetrating Clips via Biportal Endoscopic Surgery. Global Spine J 2020, 2192568220956606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, D.H.; Park, D.Y.; Hong, H.J.; Hong, Y.H.; Chung, H. Indications, Contraindications, and Complications of Biportal Endoscopic Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Lumbar Stenosis: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg 2022, 168, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Ding, Z. The morphology and clinical significance of the dorsal meningovertebra ligaments in the lumbosacral epidural space. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012, 37, E1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Zheng, X.; Min, S.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, Z.; Jin, A. The morphology and clinical significance of the dorsal meningovertebra ligaments in the cervical epidural space. Spine J 2014, 14, 2733–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).