Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

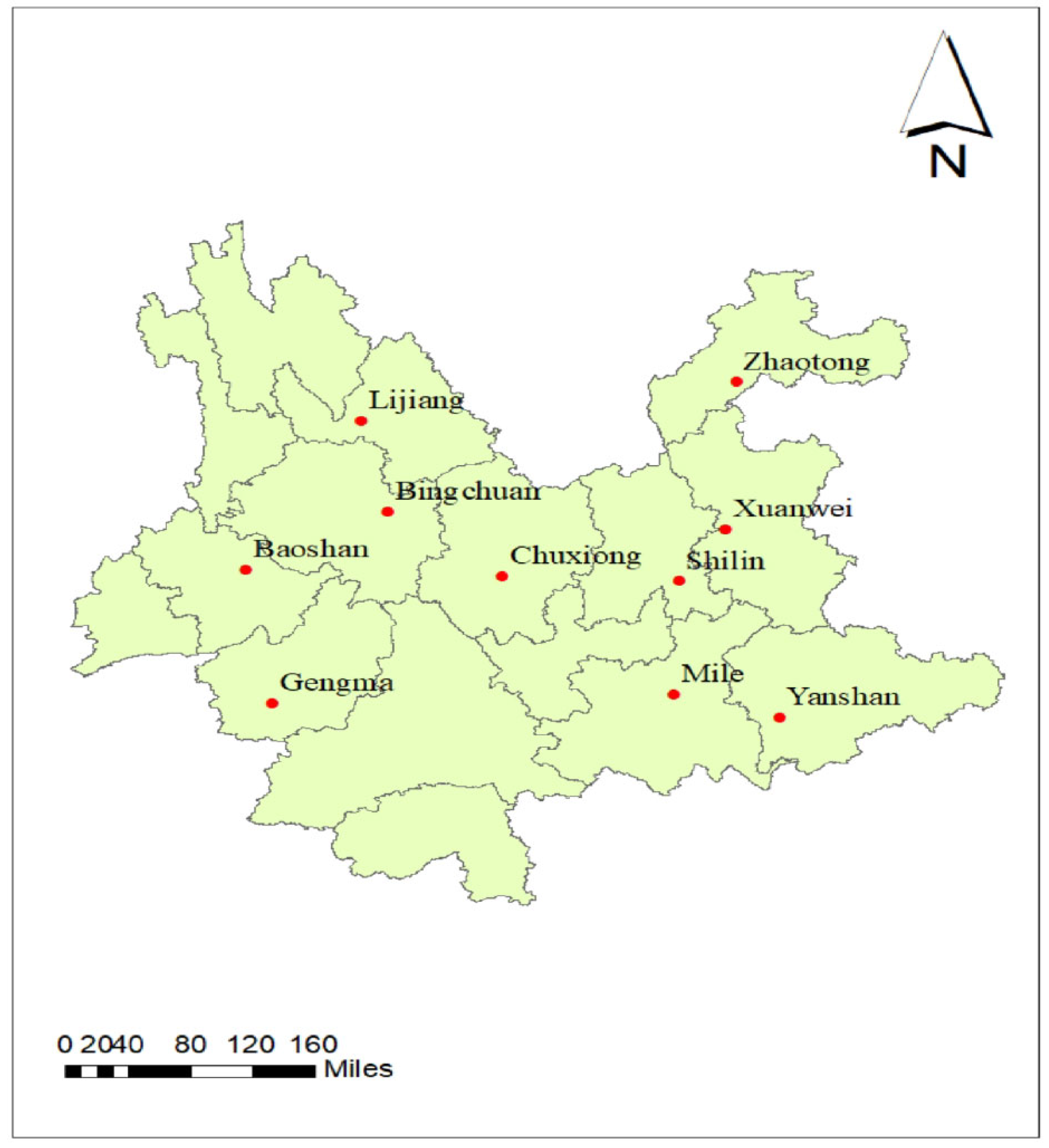

2.1. Experimental Materials, Sites, and Design

2.2. Trait measurement

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Variance Analysis (ANOVA) for Maize Yield

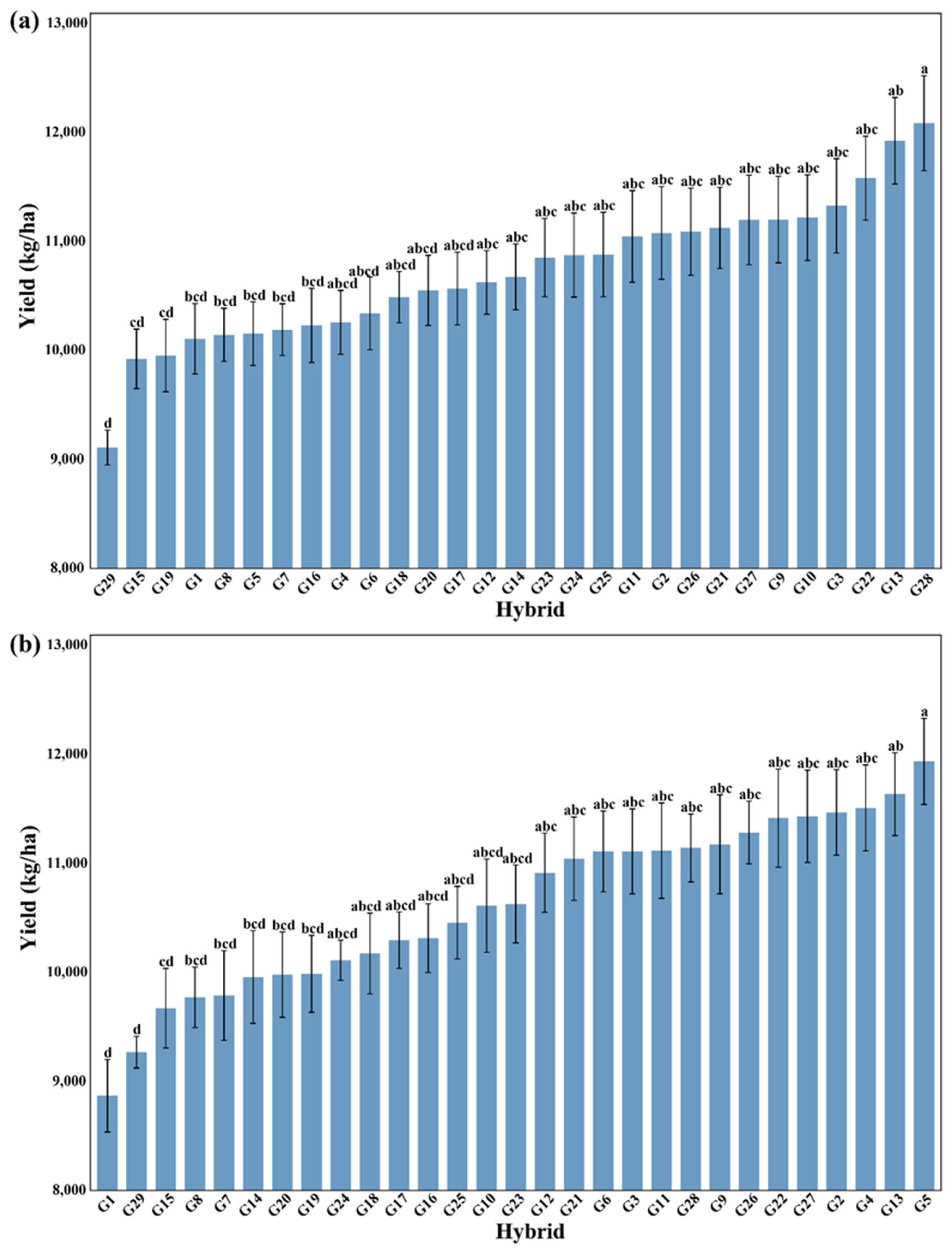

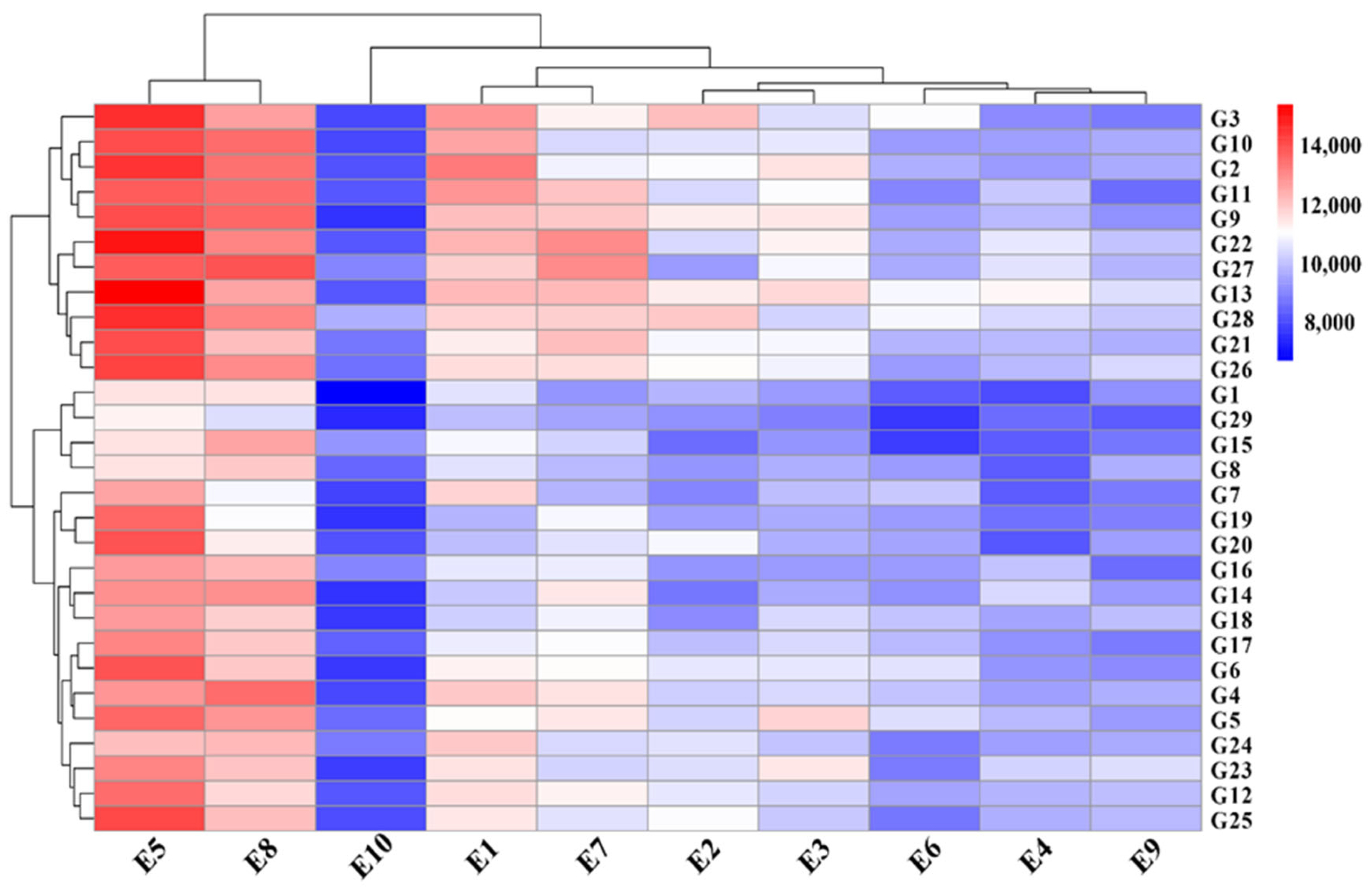

3.2. Comprehensive Visualization of Yield Bar Chart and Yield-Environment-Cultivar Relationships Heatmap

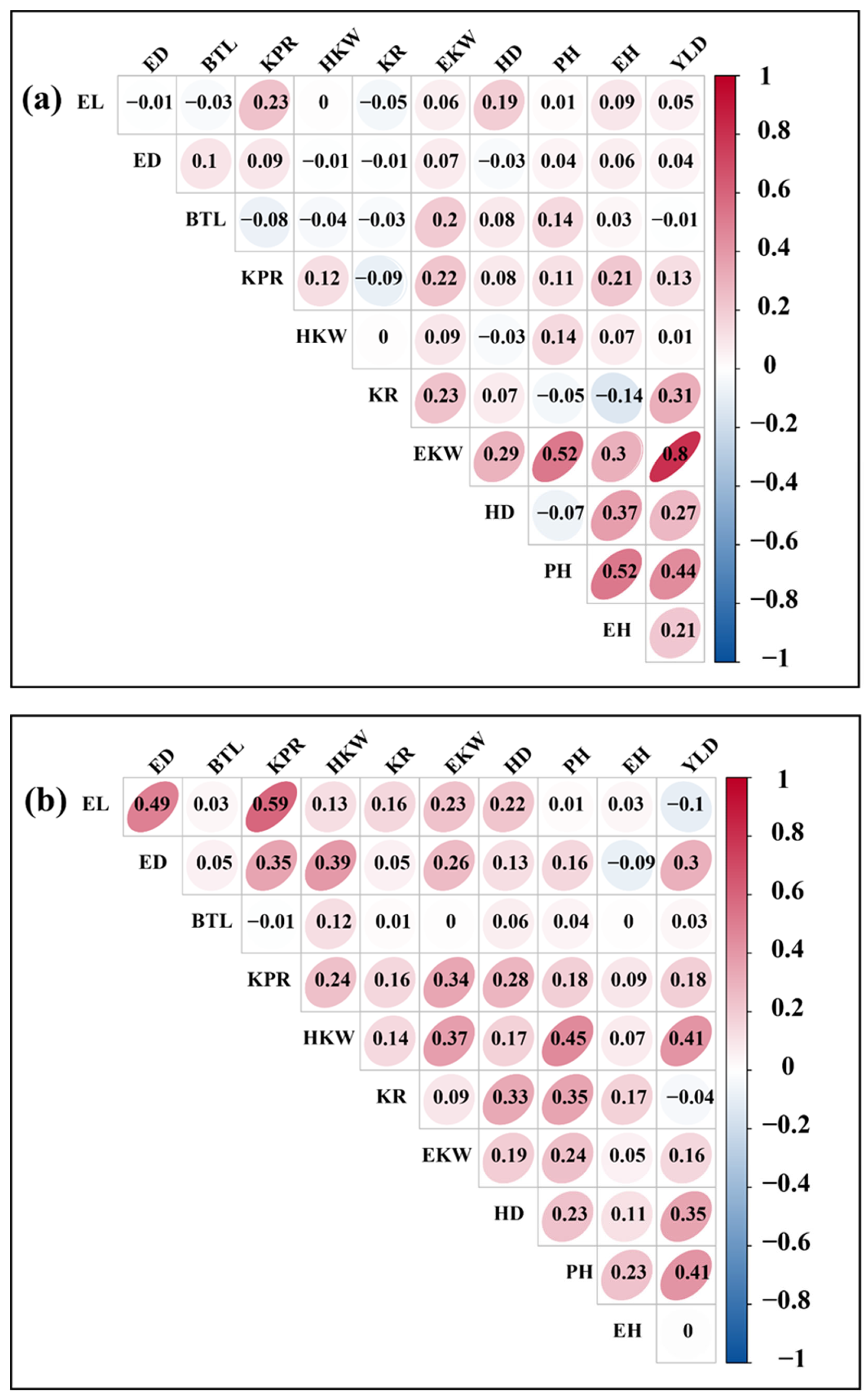

3.3. Analysis of Correlation Between Agronomic Traits and Yield

3.4. GGE Biplot Analysis

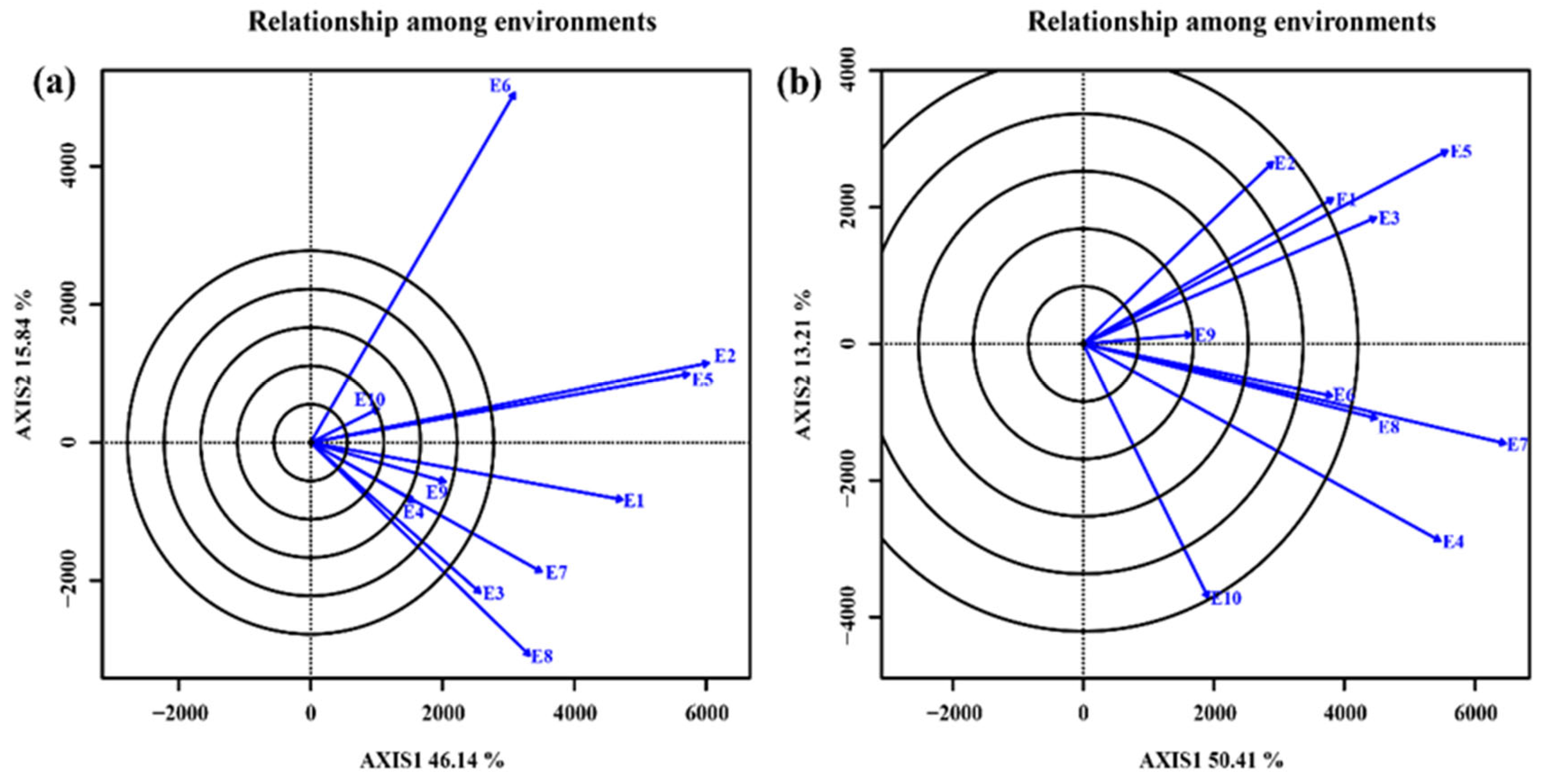

3.4.1. Relationship among test environments

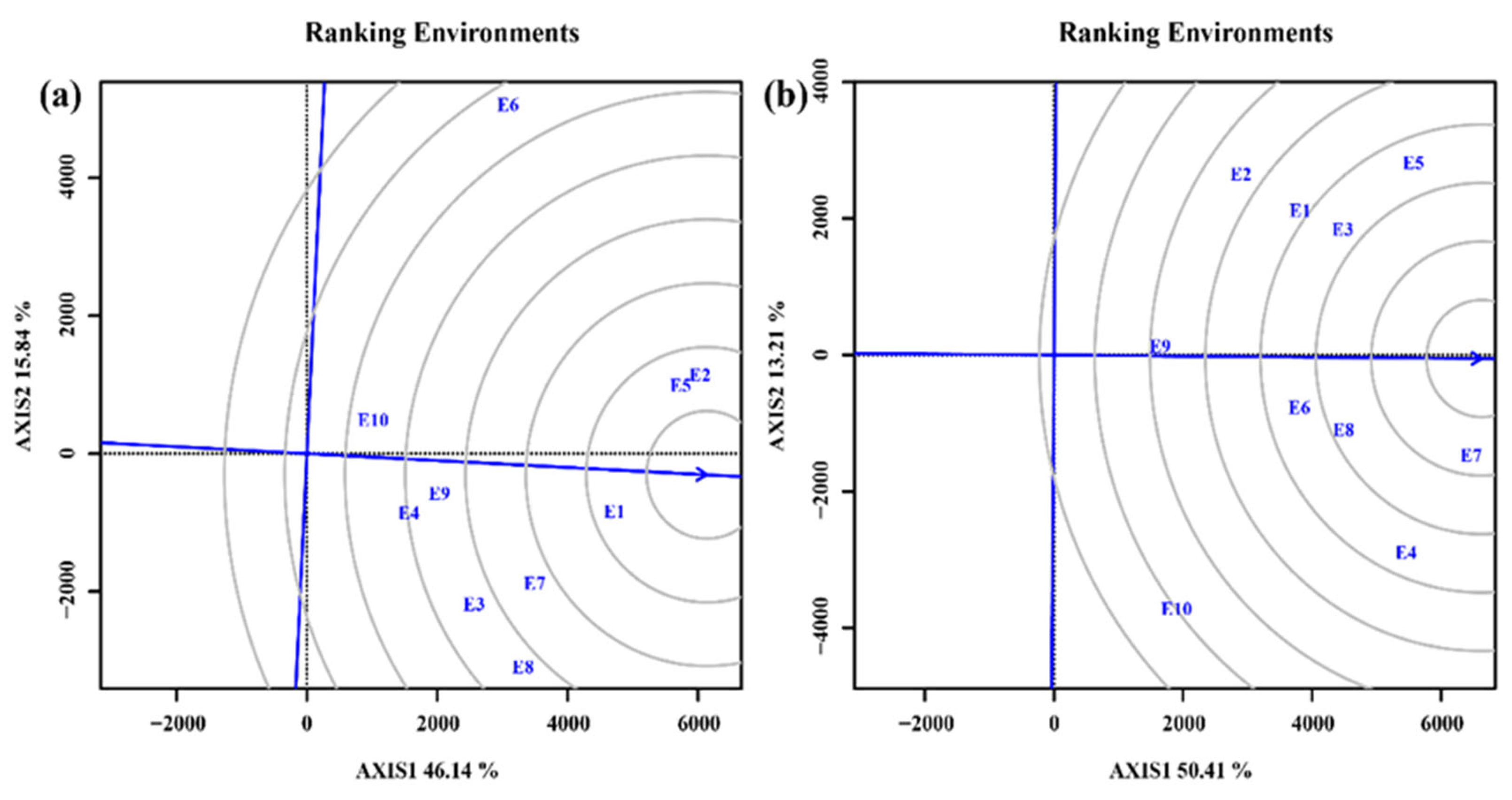

3.4.2. Selection of ideal test environments

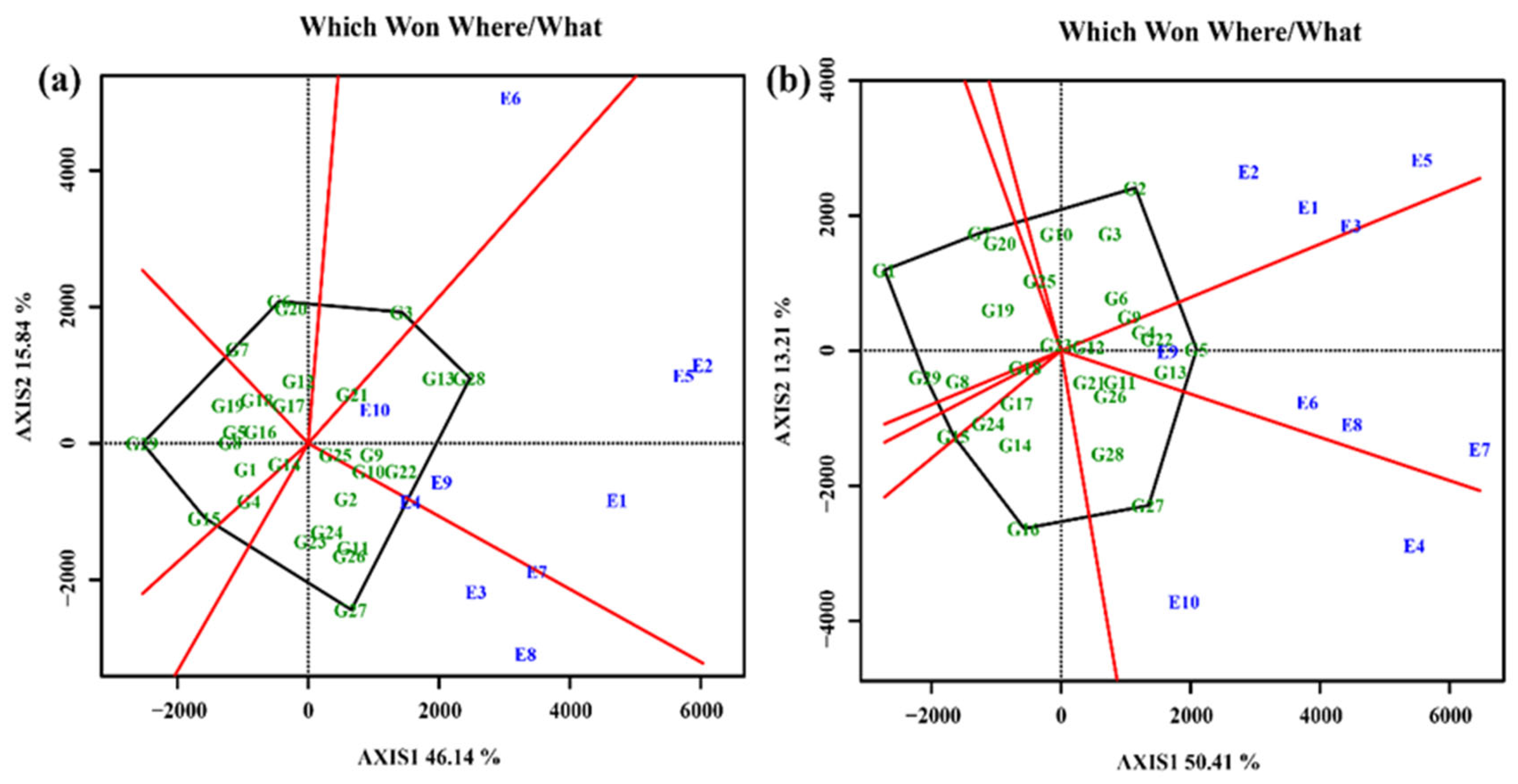

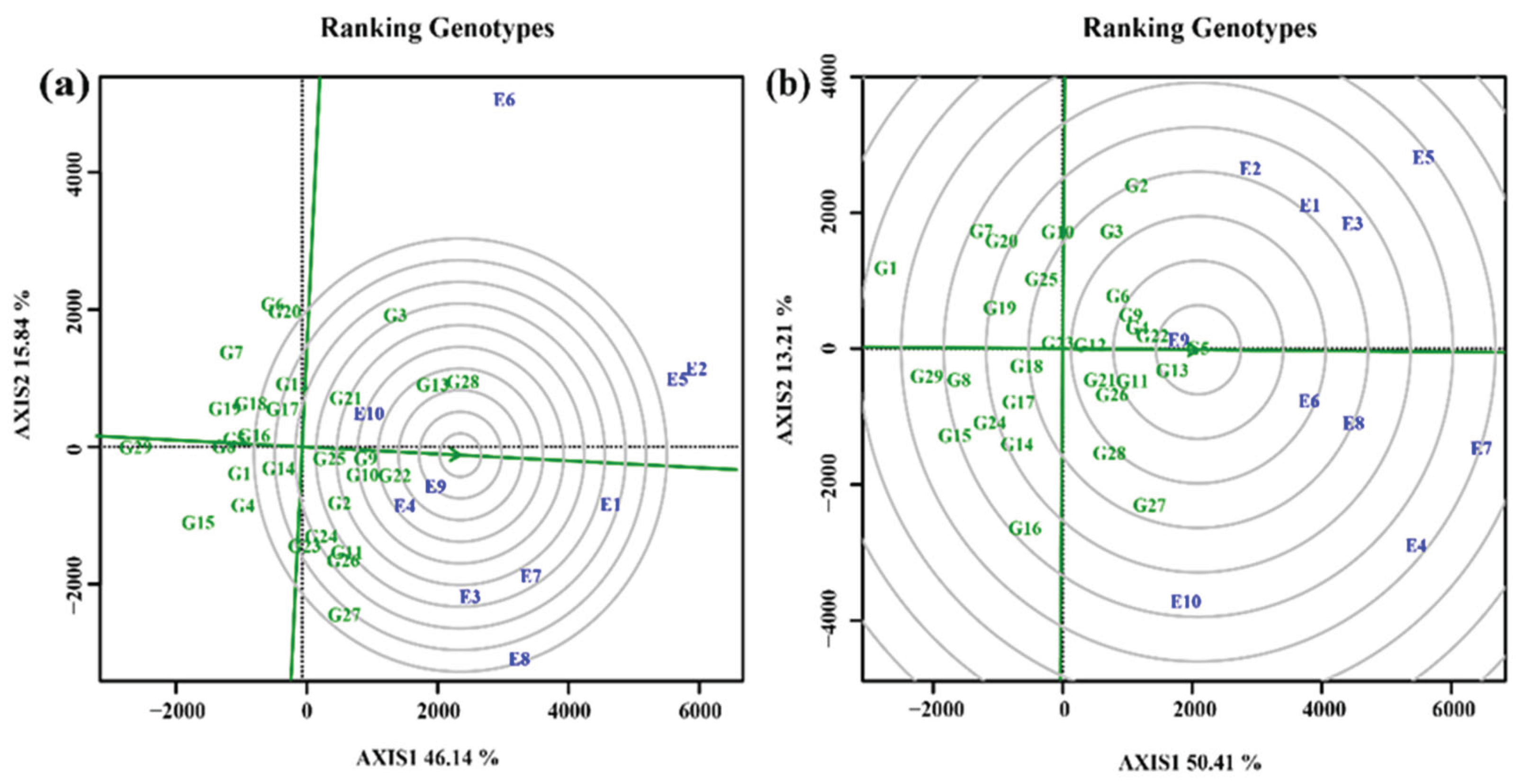

3.4.4. Screening of elite cultivars under test environments

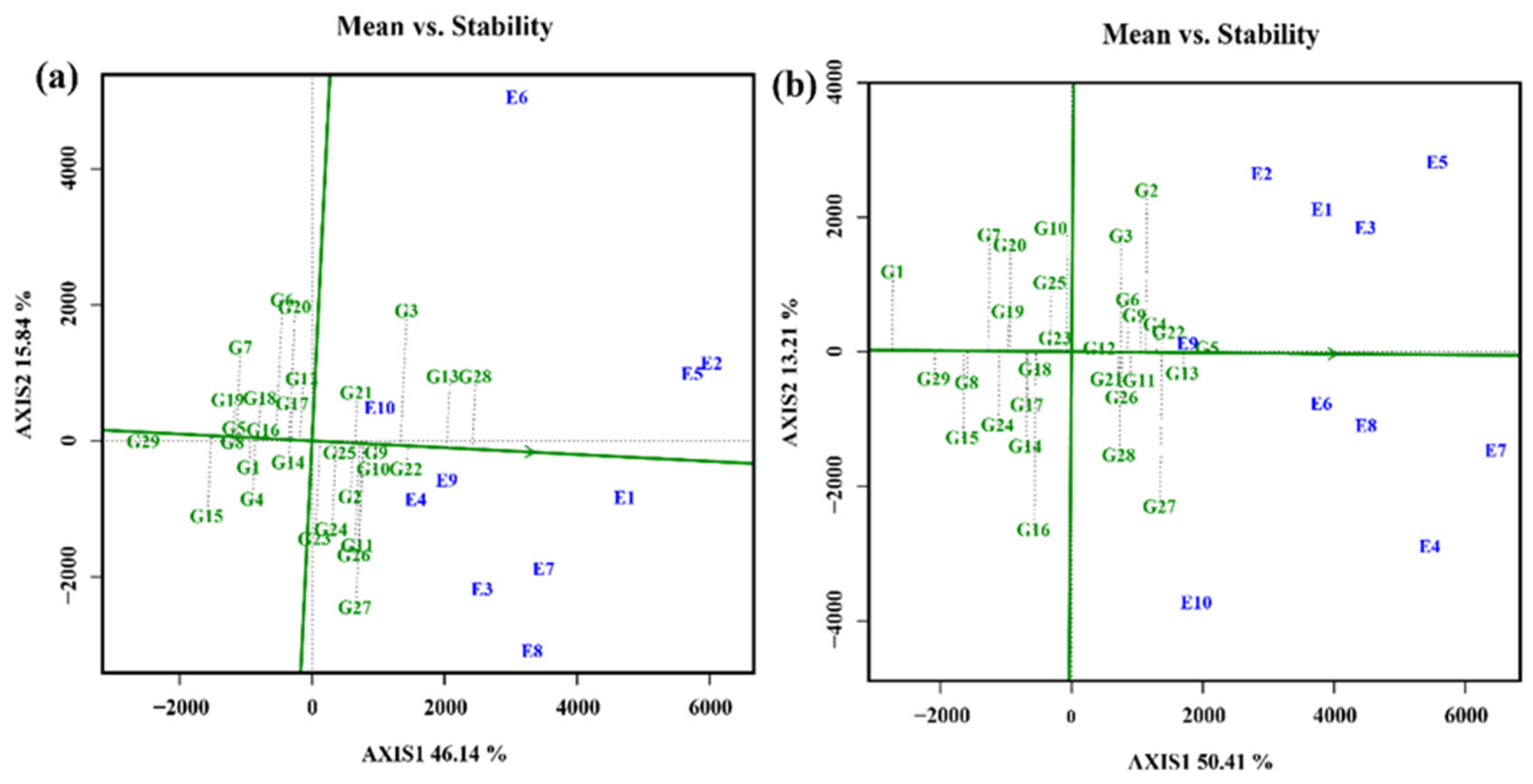

3.4.5. Selection of varieties with high stability and productivity

4. Discussion

4.1. Yield Variance Analysis

4.2. Evaluation of Ideal Test Environments

4.3. Evaluation of Ideal Genotypes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Revilla, P.; Alves, M.L.; Andelković, V.; Balconi, C.; Dinis, I.; Mendes-Moreira, P.; Redaelli, R.; Ruiz de Galarreta, J.I.; Vaz Patto, M.C.; Žilić, S. Traditional foods from maize (Zea mays L.) in Europe. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 8, 683399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food security 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, N.; Meng, Q.; Feng, P.; Qu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D.L.; Müller, C.; Wang, P. China can be self-sufficient in maize production by 2030 with optimal crop management. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Blankespoor, B.; Wood-Sichra, U.; Thomas, T.; You, L.; Kalvelagen, E. Estimating local agricultural gross domestic product (AgGDP) across the world. Earth Syst Sci Data 15: 1357–1387. 2023.

- Xin, Q.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Geng, H.; Li, X.; Peng, S. Satellite mapping of maize cropland in one-season planting areas of China. Scientific Data 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xia, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, T. Analysis of spatial and temporal changes and driving forces of arable land in the Weibei dry plateau region in China. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Duan, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Hou, P.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Dai, T.; Zhou, W. Photosynthetic capacity and assimilate transport of the lower canopy influence maize yield under high planting density. Plant Physiology 2024, 195, 2652–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bao, H.; Xu, Z.; Hu, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; Gao, J. AMMI an GGE biplot analysis of grain yield for drought-tolerant maize hybrid selection in Inner Mongolia. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocianowski, J.; Nowosad, K.; Rejek, D. Genotype-environment interaction for grain yield in maize (Zea mays L.) using the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) model. Journal of Applied Genetics 2024, 65, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Abdullah, N.; Magaji, U.; Miah, G.; Hussin, G.; Ramli, A. Genotype× Environment interaction and stability analyses of yield and yield components of established and mutant rice genotypes tested in multiple locations in Malaysia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science 2017, 67, 590–606. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, P.; Shrivastava, M.K.; Kumar, V.; Patel, N.; Biswal, M. Stability Analysis in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genotypes under Different Environmental Conditions. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2023, 35, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Barati, A.; Gholipoor, A.; Zali, H.; Marzooghian, A.; Koohkan, S.A.; Shahbazi-Homonloo, K.; Houseinpour, A. Deciphering genotype-by-environment interaction in barley genotypes using different adaptability and stability methods. Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology 2023, 26, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligarreto–Moreno, G.; Pimentel–Ladino, C. Grain yield and genotype x environment interaction in bean cultivars with different growth habits. Plant Production Science 2021, 25, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemo, B.B.; Wolancho, G.B.; Arke, Z.A.; Wakalto, D.D.; Onu, M.H.; Rahimi, M. Performance Evaluation and Stability of Maize (Zea mays L.) Genotypes for Grain Yield Using AMMI and GGE Biplot. International Journal of Agronomy 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafouasson, H.N.A.; Gracen, V.; Yeboah, M.A.; Ntsomboh-Ntsefong, G.; Tandzi, L.N.; Mutengwa, C.S. Genotype-by-Environment Interaction and Yield Stability of Maize Single Cross Hybrids Developed from Tropical Inbred Lines. Agronomy 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthoni, J.; Shimelis, H.; Melis, R. Genotype x Environment Interaction and Stability of Potato Tuber Yield and Bacterial Wilt Resistance in Kenya. American Journal of Potato Research 2015, 92, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, C.; Ye, Z. Influence of Genotype × Environment Interaction on Yield Stability of Maize Hybrids with AMMI Model and GGE Biplot. Agronomy 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.d.; Amaral, A.T.d.; Kurosawa, R.d.N.F.; Gerhardt, I.F.S.; Fritsche, R. GGE Biplot projection in discriminating the efficiency of popcorn lines to use nitrogen. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 2017, 41, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandong, E.; Uguru, M.; Oyiga, B. Determination of yield stability of seven soybean (Glycine max) genotypes across diverse soil pH levels using GGE biplot analysis. 2011.

- Zhang, P.-P.; Hui, S.; Yang, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, S.; ZHENG, D.-f. GGE biplot analysis of yield stability and test location representativeness in proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) genotypes. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2016, 15, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, P.; Almeida Filho, J.; Daher, R.; Menezes, C.; Cardoso, M.; Godinho, V.; Torres, F.; Tardin, F. Identification of sorghum hybrids with high phenotypic stability using GGE biplot methodology. Genetics and Molecular Research: GMR 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauch Jr, H.G.; Piepho, H.P.; Annicchiarico, P. Statistical analysis of yield trials by AMMI and GGE: Further considerations. Crop science 2008, 48, 866–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Nardino, M.; Carvalho, I.; Follmann, D.; Ferrari, M.; Szareski, V.; De Pelegrin, A.; De Souza, V. REML/BLUP and sequential path analysis in estimating genotypic values and interrelationships among simple maize grain yield-related traits. Genetics and Molecular Research 2017, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, R.; Bussi, B.; Petitti, M.; Franciolini, R.; Altavilla, V.; Galluzzi, G.; Di Luzio, P.; Migliorini, P.; Spagnolo, S.; Floriddia, R. Yield, yield stability and farmers’ preferences of evolutionary populations of bread wheat: A dynamic solution to climate change. European Journal of Agronomy 2020, 121, 126156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.; Hao, D.; Li, P.; Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Lu, H.; Yang, Z. Analysis of the regional trial for sweet maize in Jiangsu province based on the AMMI model and GGE biplot. Molecular Plant Breeding 2022, 20, 6939–6946. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Chen, D.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Luo, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, A.; Song, B. Evaluation of the high yield, stability and pilot discriminative power of spring maize in different ecological areas of Guizhou based on AMMI and GGE-biplot. Journal of Maize Sciences 2023, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Xu, W.; Xing, Y.; Song, W.; Li, G.; Chen, G.; Zhou, W. Application of AMMI model and GGE biplot of sweet maize varieties in Huang-Huai-Hai regional. Molecular Plant Breeding 2021, 19, 5909–5916. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Bian, G.; Huang, S.; Yang, G.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Bai, X. Analysis on the stability of national sugar beet varieties by AMMI model. China Beet & Sugar 2008, 4, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Ding, Y.; Zuo, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Yang, Z. Evaluation and analysis of the results from the regional trial of medium Japonica hybrid rice of Jiangsu province in 2018 based on the AMMI model and GGE biplot. Hybrid Rice 2021, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Kang, M.S.; Ma, B.; Woods, S.; Cornelius, P.L. GGE biplot vs. AMMI analysis of genotype-by-environment data. Crop science 2007, 47, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taak, Y.; Patel, M.K.; Chaudhary, R.; Basu, S.R.; Pardeshi, P.; Adhikari, S.; Nanjundan, J.; Saini, N.; Vasudev, S.; Yadava, D.K. Determining Drought-and Heat-Tolerant Genotypes in Indian Mustard [Brassica juncea] Employing GGE Biplot Analysis. Agricultural Research 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V.M.L.; Crevelari, J.A.; Catarina, R.S.; de Souza, Y.P.; Pereira, M.G. Adaptability and stability analysis via GGE biplot in single, double, and interpopulation maize hybrids. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, C.; Lü, J.; Ye, Z. Yield stability analysis in maize hybrids of southwest china under genotype by environment interaction using GGE biplot. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendrato, Y.; Azizah, Y.; Humam, B.; Marwiyah, S.; Ritonga, A.; Azrai, M.; Efendi, R.; Suwarno, W. Maize hybrids’ response to optimum and suboptimum abiotic environmental conditions using genotype by environment interaction analysis. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet 2025, 57, 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Neelam, S.; Bhoga, J.; Venkata, N.K.M.; Dharavath, B.; Kumari, V.; Kachhapur, R.M.; Dinasarapu, S.; Phagna, R.K.; Appavoo, D. Navigating Hybrid-Environment Interaction in Maize Evaluation: Parametric and Non-Parametric Insights. Crop Breeding, Genetics and Genomics 2025, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nišavić, N.; Čamdžija, Z.; Živanović, T.; Božinović, S.; Grčić, N.; Radinović, I.; Božović, D. Impact of genotype× environment interactions on the yield and stability of maize hybrids in Serbia. Romanian agricultural research 2025, 42, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, I.; Aleem, S.; Junaid, J.A.; Aleem, M.; Jamshaid, K.; Saleem, H.; Rizwan, M.; Chohan, S.M.; Sohail, S.; Akram, S. Evaluation of Genotype× Environment Interaction and Yield Stability of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L) Genotypes Under Heat Stress Conditions. Journal of Crop Health 2025, 77, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W. A systematic narration of some key concepts and procedures in plant breeding. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 724517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bao, H.; Xu, Z.; Hu, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; Gao, J. AMMI an GGE biplot analysis of grain yield for drought-tolerant maize hybrid selection in Inner Mongolia. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullualem, D.; Tsega, A.; Mengie, T.; Fentie, D.; Kassa, Z.; Fassil, A.; Wondaferew, D.; Gelaw, T.A.; Astatkie, T. Genotype-by-environment interaction and stability analysis of grain yield of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes using AMMI and GGE biplot analyses. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kona, P.; Ajay, B.; Gangadhara, K.; Kumar, N.; Choudhary, R.R.; Mahatma, M.; Singh, S.; Reddy, K.K.; Bera, S.; Sangh, C. AMMI and GGE biplot analysis of genotype by environment interaction for yield and yield contributing traits in confectionery groundnut. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.K.; Rai, N.; Singh, M.K.; Reddy, Y.S.; Kumar, R. Delineating genotype× environment interaction for horticultural traits in tomato using GGE and AMMI biplot analysis. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 23796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruswandi, D.; Syafii, M.; Wicaksana, N.; Maulana, H.; Ariyanti, M.; Indriani, N.P.; Suryadi, E.; Supriatna, J.; Yuwariah, Y. Evaluation of high yielding maize hybrids based on combined stability analysis, sustainability index, and GGE biplot. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 3963850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badu-Apraku, B.; Abubakar, A.M.; Adu, G.B.; Yacoubou, A.-M.; Adewale, S.; Adejumobi, I.I. Enhancing genetic gains in grain yield and efficiency of testing sites of early-maturing maize hybrids under contrasting environments. Genes 2023, 14, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, D.; Jeena, A.S.; Singh, N.K.; Pant, U.; Rohit, R.; Gaur, S. GGE biplot analysis for cane yield and sugar yield in advanced clones of sugarcane (Saccharum sp. complex). Journal of Applied Genetics 2025, 66, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanadya, S.K.; Sood, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, G.; Sood, R.; Katna, G.; Enyew, M.; Sahoo, S. Stability Indices, AMMI and GGE Biplots Analysis of Forage Oat Germplasm Under Variable Growing Regimes in the Northwestern Himalayas. Agricultural Research 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinamhodzi, L.; Makumbi, D.; Njeru, J.M.; Kanampiu, F. Performance of elite maize genotypes under selected sustainable intensification options in Kenya. Field crops research 2020, 249, 107738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Hu, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Kan, W.; Dong, X. AMMI and GGE biplot analysis for genotype× environment interactions affecting the yield and quality characteristics of sugar beet. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Tinker, N.A. Biplot analysis of multi-environment trial data: Principles and applications. Canadian journal of plant science 2006, 86, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Choudhary, M.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Sravani, D.; Vinodhana, N.K.; Kumar, G.S.; Gami, R.; Vyas, M.; Jat, B.S. GGE biplot analysis and selection indices for yield and stability assessment of maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes under drought and irrigated conditions. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 2024, 84, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagesh, P.; Takalkar, S.A.; Mohan, S.M.; Naidu, P.B.; Lohithaswa, C.H.; Kachapur, R.M.; Kuchanur, P.; Injeti, S.K.; Singh, N.K.; Kanwade, D.G. Genotype and environmental interactions in Maize ('Zea mays L.') across regions of India: Implications for hybrid testing locations in South Asia. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2025, 19, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hybrids | Code | Hybrids | Code | Hybrids | Code |

| ZHY-103 | G1 | ZF-2304 | G11 | LS-2304 | G21 |

| ZF-2302 | G2 | ZF-2305 | G12 | LS-2305 | G22 |

| ZF-2303 | G3 | YR-399 | G13 | JG-1356 | G23 |

| YR-17 | G4 | DY-801 | G14 | JG-1865 | G24 |

| YR-18 | G5 | YBY-202 | G15 | SS-2203 | G25 |

| DY-604 | G6 | SS-2201 | G16 | SS-2204 | G26 |

| YBY-201 | G7 | SS-2202 | G17 | SS-2205 | G27 |

| LS-2301 | G8 | JG-1872 | G18 | SS-2206 | G28 |

| LS-2303 | G9 | JG-1881 | G19 | WG-3861(CK) | G29 |

| MS-2301 | G10 | MS-2302 | G20 |

| Location | Code | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Altitude (m) |

| Baoshan | E1 | 25°09′ | 99°13′ | 1592 |

| Binchuan | E2 | 25°48′ | 100°35′ | 1430 |

| ChuXiong | E3 | 25°08′ | 101°18′ | 1767 |

| Gengma | E4 | 23°74′ | 99°62′ | 1340 |

| Lijiang | E5 | 100°3′ | 26°58′ | 1819 |

| Mile | E6 | 24°27′ | 103°31′ | 1543 |

| Shilin | E7 | 24°41′ | 103°27′ | 1927 |

| Xuanwei | E8 | 26°15′ | 104°8′ | 1980 |

| Yanshan | E9 | 23°07′ | 104°34′ | 1490 |

| Zhaotong | E10 | 27°19′ | 103°42′ | 1920 |

| Source of | Degrees of Freedom (DF) | Sum of Squares (SS) | Mean Squares | F-Calculated | Proportion of SS (%) |

| Variation | |||||

| Environments(E) | 9 | 2386119 | 265124355.8 | 576.3844*** | 63.79 |

| Genotypes(G) | 28 | 4921447 | 17576597.05 | 38.2117*** | 13.16 |

| G×E Interaction | 252 | 5684386 | 2255708.6 | 4.9039*** | 15.2 |

| Replication | 2 | 2246726 | 22467.26 | 0.0488 | 0 |

| Residuals | 639 | 2939261 | 459978.29 | 7.86 | |

| Total | 929 | 3740651 | 100 |

| Source of | Degrees of Freedom (DF) | Sum of Squares (SS) | Mean Squares | F-Calculated | Proportion of SS (%) |

| Variation | |||||

| Environments(E) | 9 | 2386119 | 265124355.8 | 576.3844*** | 63.79 |

| Genotypes(G) | 28 | 4921447 | 17576597.05 | 38.2117*** | 13.16 |

| G×E Interaction | 252 | 5684386 | 2255708.6 | 4.9039*** | 15.2 |

| Replication | 2 | 2246726 | 22467.26 | 0.0488 | 0 |

| Residuals | 639 | 2939261 | 459978.29 | 7.86 | |

| Total | 929 | 3740651 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).