1. Introduction

The study of meaning has long oscillated between two gravitational poles: structure and process. For much of the late twentieth century, cognitive linguistics anchored itself firmly to the structural side. The prototype revolution initiated by Rosch [

27] and extended through Lakoff [

23]’s radial categories offered a powerful corrective to classical Aristotelian categorization, demonstrating that human concepts are not bounded by necessary and sufficient conditions but organized around graded, fuzzy structures with better and worse examples. This insight transformed how linguists understood polysemy, metaphor, and the architecture of the mental lexicon.

Yet as we moved into the second decade of the twenty-first century, cracks began to appear in this edifice. The radial diagrams that populated cognitive linguistics textbooks—elegant maps of semantic extension from prototypical cores to peripheral senses—captured

what meanings exist and

how they are theoretically connected, but remained silent on a crucial question: how do speakers actually

navigate these structures in the real time of discourse? The polysemy network for a word like “mother” or “over” [

23] presents a timeless snapshot, a photograph frozen at infinite exposure. What it cannot show is the cognitive and communicative

cost of moving from one sense to another, the

trajectory a speaker traces through the network, or the

constraints that channel certain paths while blocking others.

This limitation is not merely methodological; it is ontological. Critics have noted that classical radial models inherit an implicit representationalism that reifies meaning, treating it as an object stored in the mind rather than a dynamic event unfolding in interaction [

16]. The “quantitative turn” in cognitive linguistics [

17,

20] has further exposed the gap between introspective intuitions about category structure and actual patterns of use in corpora and experiments. What linguists judge to be “central” or “peripheral” often fails to align with distributional evidence, raising questions about the falsifiability and predictive power of static network models [

28].

Meanwhile, parallel developments in linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics were reshaping our understanding of indexicality and social meaning. Silverstein’s (2003) theory of indexical orders revealed that the relationship between linguistic signs and social context is not fixed but dialectically stratified—signs accumulate layers of meaning through historical processes of

enregisterment that unfold across biographical and cultural time. Hanks [

18] reconceptualized the deictic field not as a Cartesian coordinate system but as a

field of practice, where “here” and “there” are relational positions defined by perceptual access, social symmetry, and embodied orientation. Navigation through this field requires a practical

habitus—a know-how that is learned, embodied, and culturally saturated.

In stance and positioning research, a similar temporal turn was underway. Du Bois [

8] established the foundational “stance triangle”—the simultaneous evaluation of objects, positioning of subjects, and alignment with interlocutors—but this model was initially applied to brief interactional moments. Subsequent work expanded the temporal horizon. Thompson [

32] argued for analyzing stance across longer timescales, introducing the notion of “stance ownership” that accumulates through repeated positioning acts. Andries et al. [

2] documented how stance-taking is organized temporally throughout discourse, with participants continuously adapting and negotiating their positions through multimodal resources—gesture, gaze, prosody, posture. Yeung [

34] proposed the concept of “narrative trajectory” to capture how identity evolves through interdiscursive links across multiple speech events, not just within single interactions.

These converging developments point toward a fundamental reconceptualization: from meaning as

structure to meaning as

navigation. Yet despite growing consensus on the need for dynamic, process-oriented models, a significant methodological gap persists. As Burnett & Bonami [

3] observe, most approaches remain qualitative or descriptive, lacking formal tools to quantify the “distance” between discursive positions or the “cost” of transitioning between them. The geometry is intuited but not calculated; the dynamics are described but not measured.

1.1. The Contribution of Radial Analysis

Radial Analysis (RA) addresses this gap by transforming radial category theory from static structural mapping into dynamic trajectory modeling. Building on the Trace & Trajectory (T&T) Framework’s pre-representational architecture [

11], RA provides researchers with practical tools for three analytical challenges that categorical approaches handle only through ad hoc mechanisms:

Simultaneous multi-level positioning. When a speaker says “we Mexicans have always…” while gesturing toward themselves, the utterance operates at collective, historical, and embodied levels simultaneously. Categorical frameworks require separate analyses that fail to capture the

integrated navigational act—they map positions but miss the motion. RA tracks the single trajectory through multidimensional space, with formal tools introduced in

Section 2 that make these levels analytically distinct yet compositionally unified.

Asymmetric intersubjective dynamics. A clinician and patient discussing “your autism” occupy different positions relative to the same diagnostic category. The patient navigates

through the category to reach self-understanding; the clinician navigates

around it as a professional tool. Same words, different trajectories, different informational costs. RA develops metrics—formalized in

Section 2 and

Section 3—that quantify these asymmetries rather than merely describing them.

Geometric constraints on identity navigation. A deaf student explaining their competence to hearing faculty may need to detour through external validation before affirming self-knowledge. This obligatory trajectory—invisible to categorical analysis—reveals how institutional power configures the space of navigational possibilities. RA’s geometric architecture renders such constraints analytically tractable, providing formal tools to characterize how certain navigational paths become blocked, costly, or coerced.

The framework accomplishes this through three methodological innovations. First, trajectory formalization: rather than mapping speakers to static positions, RA tracks movement through identity space as ordered sequences , capturing the temporal unfolding of positioning acts. Second, calculable metrics: hexagonal distance provides a principled measure of informational cost, enabling quantitative comparison—we can demonstrate that certain trajectories require several times more navigational effort than direct alternatives, moving beyond impressionistic claims about “costly” identity work. Third, phenomenological grounding: the experiential zero-point anchors analysis in lived experience rather than abstract categories, ensuring that navigation is always analyzed from the agent’s own baseline rather than from an external observer’s coordinate system.

1.2. Position in the T&T Framework

RA is one component of the broader Trace & Trajectory (T&T) Framework, which comprises:

| Component |

Function |

| CLOUD |

Ontological foundations (consciousness-first, informational monism) |

| T&T Semantics |

Core theoretical architecture () |

| Radial Analysis |

Applied methodology for indexicality and identity |

This paper presupposes T&T foundations without extensive development. Readers seeking theoretical depth should consult Escobar L.-Dellamary [

11] for the core semantic framework and Escobar L.-Dellamary [

9] for ontological grounding. Here we focus on

how to use RA, not

why it works at the foundational level.

1.2.0.1. Foundational commitments.

Before proceeding, four commitments underlying T&T must be made explicit, as they shape how the hexid architecture should—and should not—be interpreted:

- 1.

Anti-representationalism. Meaning is not a relation between symbols and referents but a navigational dynamic. Trajectories through informational space are meanings, not vehicles that “carry” or “encode” them. There is no gap between form and content requiring a bridging mechanism.

- 2.

Informational monism. Reality is information; what we distinguish as “matter” and “mind” are interface-level distinctions within a unified substrate. Conscious agents are not receivers of information from an external source but navigational regimes within the informational field itself.

- 3.

Semiotic (not semantic) space. The hexid architecture establishes conditions for meaning creation, not a structure that stores or encodes meanings. We use “semiotic” deliberately: the space defines where and how signification can occur, not what signs mean. Meanings exist only as trajectories—they have no static address.

- 4.

Saturation, not composition. Positions in the hexid are saturations—accumulations over traces in regions of informational space—not semantic components. Crucially, saturation is a cumulative function over a discrete trace space: there is no true continuity, no genuine fuzziness. What appears as gradience or blurred boundaries reflects accumulation that de-differentiates distinctions at coarse observational resolution—like pixels that blend into continuous color when viewed from a distance but remain discrete at close inspection. The model is fine-grained enough to track apparent continuities in semiotic dynamics while remaining fundamentally discrete. Navigation through saturated regions constitutes the act of signification itself; it is not the dynamic combination of parts. This distinguishes T&T from construction grammars and other models that dynamize compositional assembly: meaning emerges through trajectory rather than through the recruitment and integration of stored units.

These commitments entail that RA’s hexagonal geometry should not be read as a spatial metaphor for “conceptual structure” in the cognitivist sense. The hexid is not a map of meanings but a navigational terrain—it constrains and enables trajectories without containing them. Readers familiar with Gärdenfors’s conceptual spaces or Lakoff’s radial categories will recognize superficial similarities, but the ontological status differs fundamentally: those frameworks model structure; RA models dynamics.

1.3. Paper Overview

Section 2 introduces the SpiderWeb architecture—the geometric substrate for trajectory analysis.

Section 3 presents the notation system and seven-step analytical procedure.

Section 4 demonstrates RA through worked examples spanning personal deixis, temporal reference, identity navigation, and epistemic appropriation dynamics.

Section 5 addresses extensions, limitations, and future directions.

Section 6 synthesizes contributions and situates RA within the broader landscape of dynamic approaches to meaning.

2. The Hexid Framework

This section introduces the geometric architecture underlying Radial Analysis. Rather than presenting abstract formalism, we focus on operational understanding: what do analysts need to know to apply RA effectively?

2.0.0.2. Origins: A game board for identity navigation.

HEXID emerged from empirical observation rather than theoretical mandate. During fieldwork with yoreme (Mayo) communities in northern Sinaloa, Mexico, analysis of identity discourse revealed a recurring pattern: speakers did not simply claim identity categories but moved between them—participating “as yoreme,” then “as yori” (the community’s counter-exonym for non-indigenous others), while repeatedly returning to an unmarked experiential center. One yoreme teacher captured this choreography with striking precision: “it’s a game, and it’s beautiful... there are yoremes who know songs as yoremes, and know songs as yoris... they opened the world of yoris for me, well then, we have to participate as yoris.”

This observation—identity as navigation rather than membership—demanded analytical tools that existing frameworks could not provide. What was needed was a heuristic structure with sufficient richness of movement, where positions could be located relative to a deictic center, where distances would encode informational effort, and where multiple navigational pathways would be available rather than binary alternatives. The question became: what kind of “board” would support this analysis?

The answer came from an unexpected source: Władysław Gliński’s hexagonal chess (1936). Hexagonal tessellation provides exactly the navigational flexibility required—each position maintains six equidistant neighbors, enabling isotropic movement without directional bias. But the choice proved to be more than pragmatic convenience. Hexagons are not arbitrary decoration but an organic geometry that appears spontaneously across natural systems: in honeycomb structures (optimally efficient per Hales’ 2001 proof), in neural grid cells mapping spatial navigation (Hafting et al., 2005), in Bénard convection cells and basalt columns. The hexagonal board accesses a fundamental organizational pattern rather than imposing one.

This ludic, didactic origin should not be forgotten as the formalism develops. HEXID remains, at its core, a board game for thinking about identity—a heuristic tool that trades mathematical generality for illustrative power. The hexagonal geometry is “medium-definition” access to a “high-definition” pre-representational substrate. Where the model succeeds, it succeeds by making navigational dynamics visible and playable, not by capturing some ultimate mathematical truth about identity’s structure.

Navigation as signification.

A terminological clarification is essential before proceeding. “Navigation” in RA is not a spatial metaphor for cognitive processing—it names the act of meaning-making itself. When we say an agent navigates through hexid positions, we do not mean they “move mentally” through a structure that contains pre-stored meanings. Rather, the trajectory through positions constitutes the meaning; there is no separate semantic content that navigation retrieves or expresses. This is the core anti-representationalist commitment: meaning does not consist of represented content encoded in forms, but emerges through navigational dynamics. A trajectory does not “carry” meaning—it is the semiotic event. Readers should resist the intuitive tendency to interpret hexid geometry as a map of meanings; it is better understood as a terrain of navigational possibilities whose traversal generates signification.

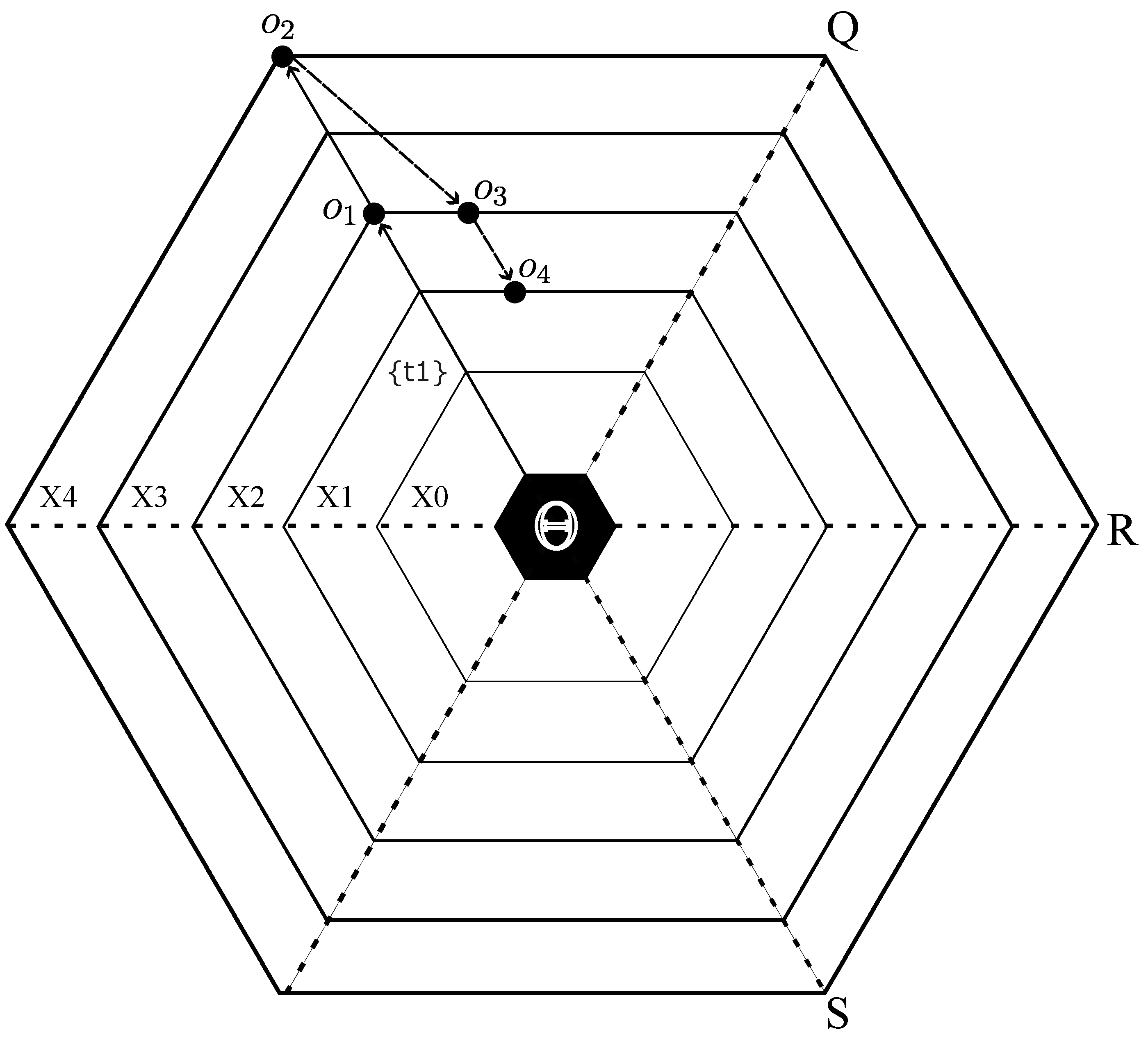

2.1. SpiderWeb Architecture: Hexid, Hex, Phex

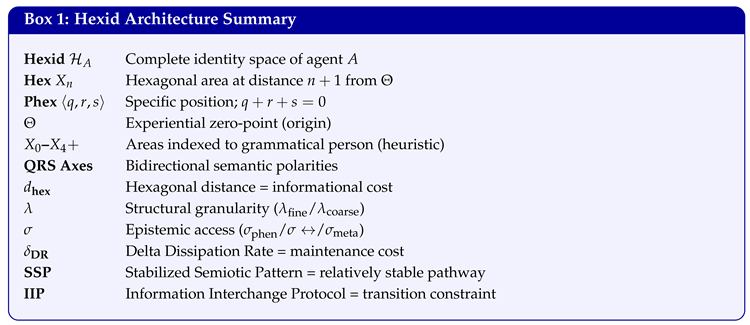

RA employs a hexagonal coordinate system we call the

SpiderWeb architecture or HEXID—Hexagonal Identity Dynamics—, a board game model comprising three nested levels of description (see

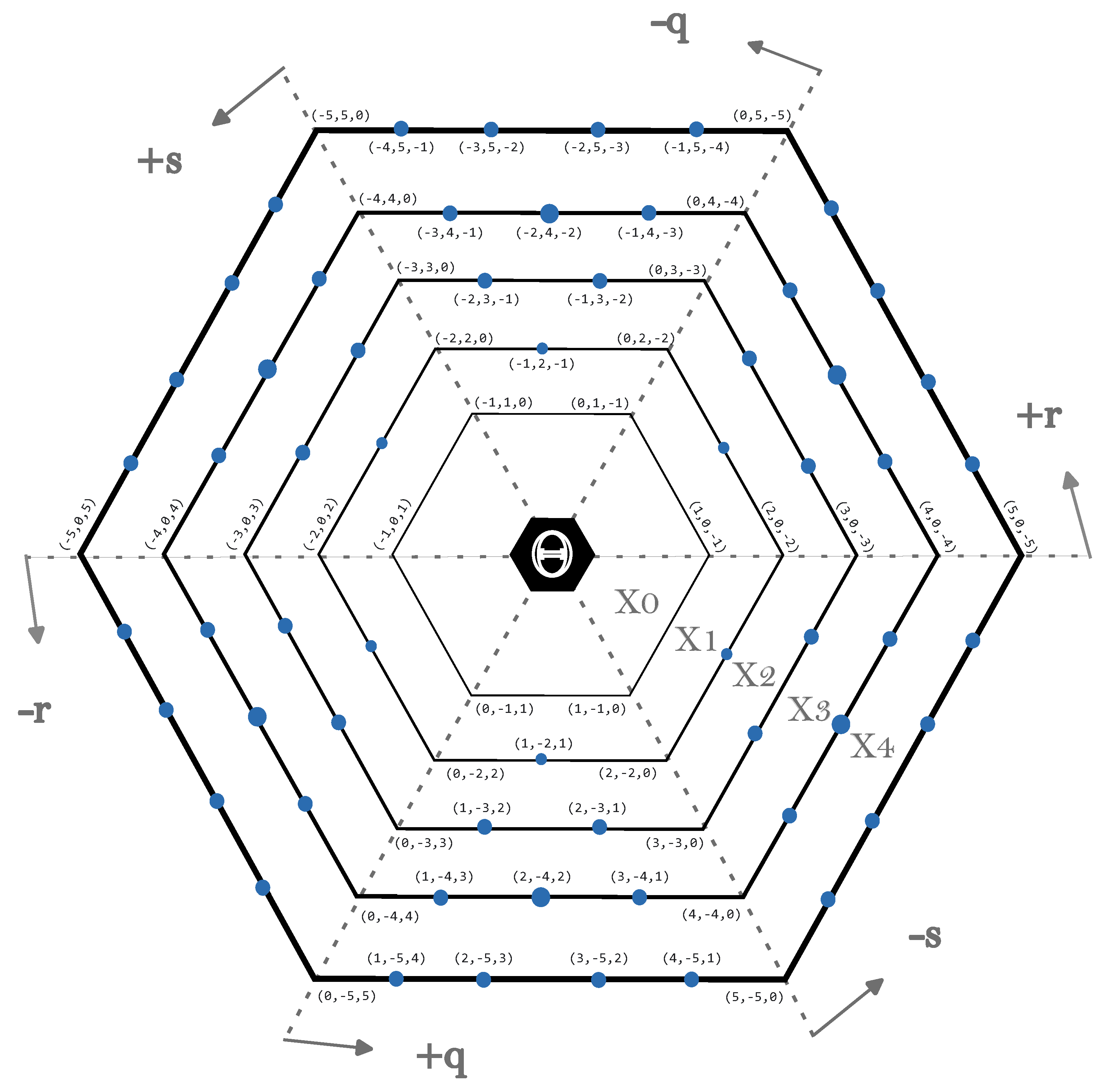

Figure 1):

-

Hexid ()

The complete identity space of agent A. The hexid encompasses all positions an agent can navigate—from experiential baseline through increasingly differentiated identity configurations. Think of it as the entire “board” on which identity navigation occurs.

-

Hex ()

A single hexagonal area at distance

from the center. Each hex contains

discrete positions arranged in a ring. The subscript

n is designed to correspond stereotypically with grammatical person (see §

2.2).

-

Phex ()

A specific position within the hexid, specified by cubic coordinates satisfying , notated as as the first position traversed by a trajectory. The angle brackets visually evoke hexagonal geometry and distinguish position notation from other uses of coordinates.

This three-level terminology enables analysts to shift seamlessly between holistic description (“the agent’s hexid shows restricted navigation”), area-level generalization (“trajectories cluster in ”), and precise specification (“position serves as attractor”).

2.2. Hexagonal Areas and Grammatical Person

The hexid centers on (theta), the experiential zero-point—the undifferentiated baseline from which all coded positioning emerges and to which navigation returns between discursive moves. is not a hex but the origin from which hexagonal areas radiate.

As the point of minimal saturation, represents informational homeostasis—the baseline to which agents return when discursive positioning relaxes. Navigation from requires investment; navigation toward releases accumulated informational load.

Hexagonal areas are indexed to facilitate intuitive correspondence with grammatical person and experiential distance:

| Area |

Label |

Characterization |

|

Experiential Zero |

Pre-embodiment baseline; informational homeostasis prior to differentiation. The point of minimal maintenance cost. |

|

Proprioceptive Self |

Embodied selfhood without categorical identity—the “I” of contemplative presence, prior to name or social role. Pre-personal. |

|

First Person |

The categorical “I” of identity and social roles. Stereotypical correspondence with 1st person singular/plural. |

|

Second Person |

The addressed “you”—interlocutor positions. Stereotypical correspondence with 2nd person. |

|

Third Person |

Referenced others not directly addressed. Stereotypical correspondence with 3rd person. |

|

Outer Areas |

Alienated, abstract, or institutionalized positions. Increasingly distant from experiential center. |

Critical clarification.

Hex positions do

not “mean” grammatical categories. The correspondence

-th person is a

heuristic for didactic purposes, not a semantic rule. Actual semantic values emerge from

navigation through positions modulated by axis polarities (§

2.3), saturation patterns, and interface parameters (§

2.4). A speaker may occupy

while referring to third parties, or navigate to

while discussing themselves—what matters is the

trajectory, not the static position.

The / distinction.

Previous frameworks sometimes conflated experiential baseline with minimal selfhood. RA distinguishes them architecturally: represents pre-embodiment (mathematically, the origin ), while represents embodied but pre-personal presence. This distinction proves crucial for analyzing contemplative states, certain neurodivergent experiences, and the phenomenology of “losing oneself” in absorption.

2.3. QRS Axes and Navigational Sectors

The hexagonal geometry employs cubic coordinates with the constraint , embedding a 2D hexagonal manifold in 3D coordinate space. This constraint ensures that movement along any axis automatically compensates along the others—a formal property with phenomenological significance: identity shifts are never isolated but ripple across dimensions.

2.3.1. Axis Polarities

Each axis has positive and negative poles, yielding six primary directional regions:

| Axis |

Positive Pole |

Negative Pole |

| Q |

Individual/Singular |

Collective/Plural |

| R |

Personal/Specific |

Generic/Impersonal |

| S |

Other-oriented |

Self-centered |

These semiotic assignments are domain-configurable. The Q/R/S polarities above (individual/collective, personal/generic, other-oriented/self-centered) suit deictic and identity analysis, but researchers studying other phenomena assign different stereotypical saturations to axis polarities while preserving the geometric structure. The core deictic logic—center () versus periphery, with increasing informational cost at greater hexagonal distance—remains constant; what varies is the semiotic content that saturates each directional region.

Configuration examples.

Classical indexicality: Axes might represent person (1st/2nd/3rd), space (proximal/distal), and time (past/present/future)—the traditional deictic coordinates, now geometrized as navigational terrain.

Identity studies: Axes might represent marginalized/dominant positioning, authentic/performed identity, and individual/collective affiliation—enabling formal analysis of identity negotiation dynamics.

Stance analysis: Axes might represent epistemic certainty, affective valence, and alignment with interlocutor—mapping Du Bois’s (2007) stance triangle onto navigable geometry. Recent work on narrative trajectories (Yeung, 2025) emphasizes how stances solidify across timescales and chronotopic configurations; TTF formalizes this intuition through thread stabilization ( reduction) and saturation dynamics across the hexid.

-

Temporal navigation (TAM): Axes reconfigure for tense-aspect-modality analysis:

- ∘

Q axis: Temporal orientation—prospective (+) versus retrospective (−), capturing directionality of navigation from the experiential present.

1

- ∘

R axis: Aspectual boundedness—bounded/perfective (+) versus unbounded/imperfective (−), following Langacker’s (1987) construal of event contour.

- ∘

S axis: Epistemic grounding—anchored (+, experiential trace, direct evidence) versus unanchored (−, inference, projection, counterfactual).

Radial distance (–) indexes phenomenological proximity to the experiential present, orthogonal to orientation: yesterday’s vividly remembered event (, , ) differs trajectorialy from yesterday’s inferred event (, , ). This configuration enables formal analysis of cross-linguistic TAM systems without collapsing tense, aspect, and evidentiality into a single dimension—each operates as independent navigational parameter with calculable interaction costs.

The hexid architecture does not prescribe which semiotic distinctions populate the axes; it provides the geometric scaffolding within which domain-specific distinctions can be rigorously analyzed. What remains invariant across configurations is the navigational logic: movement costs something, distance from indexes maintenance burden, and trajectories—not static positions—constitute meaning.

2.3.2. Vertices and Edges

The hexagonal perimeter contains two types of canonical positions (see

Figure 2):

Vertices occur where one coordinate equals zero, with the other two maximized at opposite signs. These represent “pure” axis positions—e.g., at coordinates for .

Edges connect adjacent vertices. Positions along edges have two coordinates of the same sign. These represent blended orientations—e.g., combines individual and other-oriented polarities.

2.3.3. Hexagonal Distance

The

hexagonal distance from any position to

is:

This metric indexes

informational cost: positions at greater hexagonal distance require more maintenance effort to sustain. The distance between any two positions (

) follows the same formula applied to their coordinate differences:

Practical implication.

Trajectory cost accumulates as summed hexagonal distances across movements. A trajectory costs hexagonal steps—substantially more than the “direct” at cost 2.

Coordinates as distance, not semantic intensity.

A critical clarification: cubic coordinates serve two distinct functions that must not be conflated. The signs of coordinates (, , ) indicate qualitative direction—the semiotic sector of navigation. The magnitudes indicate quantitative distance—how far from a configuration is being sustained. A position does not mean “4 units of collectivity”; it means the agent is navigating in the sector at hexagonal distance 5 from baseline (high maintenance cost). Coordinate magnitude indexes thermodynamic distance, not semantic intensity.

2.4. Parameters and Dynamics

Beyond spatial coordinates, RA employs parameters that modulate how navigation occurs.

2.4.1. Lambda (): Structural Granularity

Lambda configures the resolution at which informational structure is rendered. Think of it as a zoom level:

: High-resolution rendering with rich internal differentiation. Subtle distinctions are available; navigation can be precise.

: Low-resolution rendering with collapsed distinctions. Broad categories dominate; fine navigation is unavailable.

Clarification: is not the Macro/Micro distinction.

The fine/coarse axis must not be confused with the macro/micro distinction familiar from materialist science. The level is not analogous to cells or atoms; is not analogous to macromolecular or societal “systems.” Both poles of the scientific macro/micro scale operate at : they are categorical, institutionally stabilized, and thoroughly meta-representational. The relationship “molecule → cell → tissue → organ → organism → population” is itself a coarse-grained structure—a thread bundle at the level of theoretical saturation.

Only under specific conditions—autosimilar collapse toward trace structure, or sustained ontological attention approaching —might scientific representations approximate basal patterns. Even then, such approximation remains within meta: science describing science, categories tracking categories. This clarification matters because readers trained in naturalistic ontologies may otherwise import assumptions that “fine” means “fundamental physics” and “coarse” means “emergent structure.” In TTF, both extremes of the materialist scale are equally coarse from the standpoint of informational granularity; what they describe are saturated stabilizations, not pre-representational structure.

Lambda is not under direct agent control—it reflects the structural configuration of the informational interface at a given moment. A speaker fatigued or emotionally overwhelmed may find themselves operating at regardless of intention.

2.4.2. Sigma (): Epistemic Access Mode

Sigma modulates how agents engage with navigational structure:

/ (Phenomenal): Immersive, unreflective engagement. The agent navigates without monitoring their own navigation.

/ (Deliberative): Active, intentional positioning. The agent selects trajectories within conventional categories.

/ (Self-reflective): Reflective stance on the navigation itself. The agent can observe and comment on their own positioning patterns. With sufficient desaturation, may disclose pre-categorial structure—like perceiving individual pixels where habitual navigation renders only smooth images.

Orthogonality principle.

Lambda and sigma are independent: fine-grained structure () can be observed abstractly (); coarse structure () can be navigated immersively (). Scale ≠ access. This independence enables RA to model phenomena like alienation (meta-reflective access to fine-grained structure one cannot inhabit) or traditionalist absorption (phenomenological immersion in coarse-grained cultural patterns).

2.4.3. Stabilization and Dissipation

Two additional concepts complete the operational toolkit:

Delta Dissipation Rate ().

quantifies the rate at which an informational configuration loses coherence without reinforcement. High-

positions are “spinning plates”—they require constant discursive work to prevent collapse. Low-

positions persist with minimal maintenance. The relationship:

where

captures epistemic maintenance burden. Positions near

exhibit low

; peripheral positions exhibit high

. This connects RA to dissipative systems theory: identity configurations, like thermodynamic structures far from equilibrium, require energetic investment to sustain organization.

2

Distribution of maintenance: costs are not borne exclusively by the individual navigator. Some high-stability patterns persist through dynamics that exceed individual agency—collective sedimentation (e.g., the category “doctor” remains stable not because each speaker actively maintains it, but because institutional structures continuously reinforce it), or structural features of the informational substrate itself (e.g., basic perceptual constancies like figure-ground segregation require no personal effort to sustain). Conversely, the interface requires high- structures as “saturation valves”—ephemeral configurations enabling navigational flow. Slang, trending expressions, and conversational hedges (“like,” “you know”) function as low-cost, high-turnover channels that absorb navigational pressure without demanding lasting commitment. What appears as personal maintenance burden is often distributed across multiple scales: a speaker’s “professional identity” is simultaneously maintained by their own discursive choices, by collegial recognition, and by credentialing institutions—the is shared, not solely individual. Yet even collectively sustained configurations remain contextually bound: the “doctor” identity that persists effortlessly in clinical settings will dissipate in intimate relationships or prolonged social isolation, where the institutional reinforcement that subsidizes its is absent.

Stabilized Semiotic Patterns (SSPs).

SSPs are collectively-saturated trajectorial sequences exhibiting relative stability—pathways through semantic space that have been “worn smooth” by recurrent navigation. NET-backed SSPs (operating at ) exhibit genuinely low ; CA-maintained SSPs (at ) achieve stability through distributed maintenance but retain elevated intrinsic . Lexical forms, grammatical constructions, and institutional categories are SSPs: pre-packaged navigational constraints rather than pointers to stored concepts. When a speaker uses the word “teacher,” they activate an SSP that constrains subsequent navigation toward institutionally-saturated positions. SSPs create the phenomenological illusion of an “objective world” by packaging the hexid’s architecture into readily navigable form.

2.5. Depth Protocol and Shading

The parameters introduced in §

2.4 configure

what structure is available and

how agents access it. A third dimension governs

whether positions achieve navigational significance at all. The

Depth Protocol (

) determines semiotic visibility—the gradient from full navigational salience to infrastructural operation without phenomenal registration.

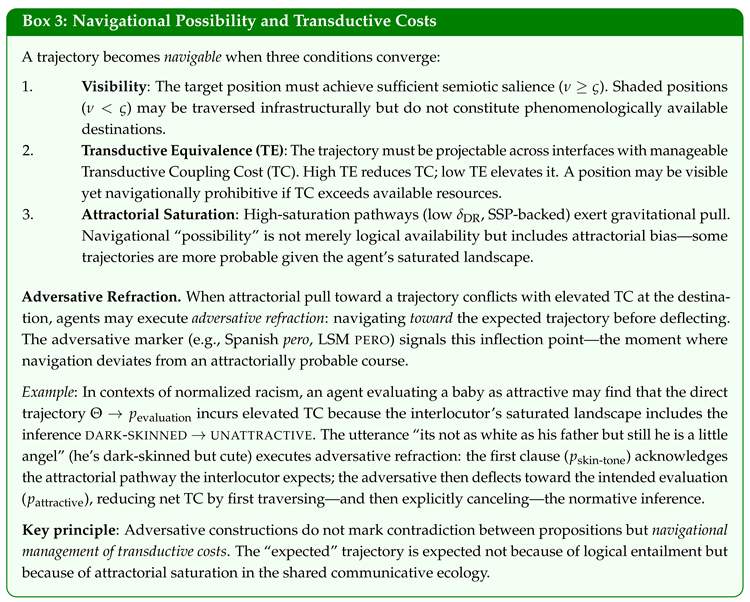

2.5.1. Shading as Semiotic Visibility Gradient

Shading describes a continuous gradient from full semiotic visibility to operational invisibility. Unlike binary visible/hidden distinctions, shading operates through a coefficient:

where

indicates full navigational significance and

indicates complete shading.

Three qualitative states emerge along this gradient:

-

Clear ()

The position achieves full navigational significance. It appears as a discrete location in the trajectory; informational costs are calculated; phenomenal content is rendered. This is the domain of conscious navigation—positions the agent experiences traversing.

-

Fog ()

Partial visibility. The position operates with reduced phenomenal presence—“glimpsed,” “sensed,” or “peripheral.” Typical of habituated objects, positions traversed rapidly, or configurations at the edge of attention.

-

Shaded ()

The position operates infrastructurally but does not signify. Navigation proceeds through these positions without registering them as locations. No phenomenal content; no conscious trajectory logging.

The significance threshold () determines the minimum value required for navigational significance. Crucially, is hexid-specific and modulable:

Different agents have different baseline values

Training can lower for specific thread bundles (heightened sensitivity)

Fatigue, overwhelm, or crisis can raise globally (reduced discrimination)

Contemplative practice characteristically lowers toward proprioceptive threads

2.5.2. Shading and Traditional Cognitive Distinctions

The distinction between clear and shaded positions may appear analogous to classical conscious/unconscious dichotomies, productively employed in cognitive semantics through notions like

windowing of attention [

31] or the

profile/base distinction [

24]. However, TTF is not a representationalist framework, and the architectural differences have substantive consequences.

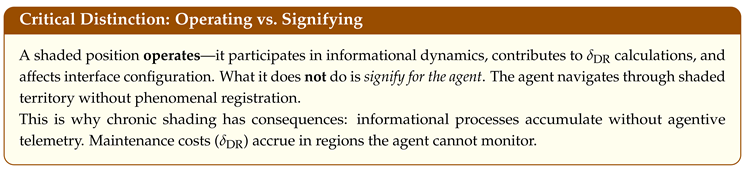

The representationalist trap.

Classical cognitive frameworks embed implicit commitments that shading explicitly rejects:

Mental compartments: The assumption that “unconscious” names a separate processing level, container, or reservoir where mental contents reside before emerging into consciousness.

Processing dualism: The distinction between what consciousness can “access” versus what operates “beneath” or “behind” awareness—even when framed as gradient, this repeatedly crystallizes into categorical language (unit vs. non-unit, accessible vs. inaccessible).

Individual locus: Processing occurs within individual cognitive architecture, treating depth as a property of one mind rather than of communicative situations.

Hidden representations: “Unconscious content” exists as stored mental objects awaiting retrieval or activation.

The TTF alternative.

Shading operates through fundamentally different commitments:

Relational ontology: Shading describes positions within communicative situations, not states of individual cognitive systems. A position is shaded relative to a specific intersubjective configuration, not intrinsically.

Dynamic constitution: Shading can shift through participatory coordination—it is not fixed by prior “processing.” What is shaded in one communicative moment can become salient in another through relational reorganization.

Non-representational: Shaded positions are not “hidden representations” waiting to be accessed but aspects of semiotic space not currently operative in participatory sense-making.

Emergent gradients: The visibility gradient () emerges from the dynamics of the communicative situation rather than being determined by individual cognitive architecture.

No homunculus: There is no internal “viewer” whose access determines what is shaded—salience emerges from relational configuration itself.

Depth as intersubjective integration.

The “depth” in Depth Protocol does not index vertical layers within individual cognition (conscious surface / unconscious depths). It indexes relational density—the degree to which positions are integrated into the intersubjective dynamics of the communicative situation. Significance thresholds () are hexid-specific, but a position is shaded not because it lies beneath a threshold granting “access” to hidden cognitive contents, but because it does not currently achieve phenomenal registration in participatory sense-making. The threshold determines what signifies, not what is “accessible”—and the threshold itself is relationally configured.

This reconceptualization has methodological consequences. When Langacker [

24] describes how entrenched structures become “less salient... precisely because the speaker no longer has to attend to them individually,” the explanatory weight falls on individual processing history (entrenchment). In RA, the explanatory weight shifts to

situational dynamics: the same agent may navigate the same thread bundle with different shading configurations depending on communicative context, interlocutor configuration, and participatory demands. Shading is situationally variable, not a fixed property of the agent’s “cognitive architecture.”

Visualizing thread stratigraphy.

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between constitutive thread depth and agential visibility. The mangrove-root structure captures a key architectural feature: thread bundles are not flat cuts across a uniform axis but

filamentous structures that rise and descend through the

-dimension, with Harmonic Folds (potential positions) distributed at varying depths along their extension.

The water-surface analogy clarifies what is agent-relative and what is not:

Thread depth: constitutive, not observer-dependent. The root is where it is.

Visibility threshold (): agent-relative, situation-dependent. The “water level” varies.

Clear/Fog/Shaded status: emergent from the intersection of constitutive depth and current threshold.

This architecture explains why the “same” thread bundle can present different visibility profiles across agents or situations without the thread itself changing. A contemplative practitioner operating at deep -cut (low ) renders Harmonic Folds that remain Shaded for an agent operating at coarse -cut. The roots have not moved; the water level differs.

2.5.3. Shading Configurations

Persistent configurations of where certain hexid regions chronically fail to achieve significance constitute stable shading regimes. These configurations constrain the agent’s significance range—the set of positions that achieve navigational significance ().

Two canonical configurations have particular analytical relevance:

Root-shading.

Chronic shading of basal positions (, ). The body operates but does not signify; proprioceptive and first-person positions fail to achieve navigational salience. Phenomenologically, this manifests as experiences of depersonalization, dissociation, or “not feeling like oneself.” The agent can navigate outer positions (+) while inner positions remain infrastructurally operative but phenomenally absent.

Root-shading typically produces low -centrality: the agent cannot return to significant baseline because baseline positions are shaded. Trajectories originate from and terminate at outer positions without registering inner transit.

Depth-shading.

Chronic shading of outer positions (+). The agent achieves stable significance at inner positions but outer positions fail to stabilize. Phenomenologically, this manifests as difficulty with intersubjective navigation, social anxiety, or “not knowing how to be around others.” The agent experiences rich inner life while outer positions remain operationally necessary but phenomenally inaccessible.

Depth-shading may produce high -centrality: the agent returns frequently to baseline because outer rings do not achieve stable significance—trajectories extend outward but collapse back before stabilizing at external positions.

Genesis typology.

Shading configurations emerge through different pathways:

Protective: Shading develops as adaptive response to overwhelming input—positions are shaded to reduce informational load.

Traumatic: Specific positions become shaded following experiences that made their navigation costly or dangerous.

Structural: Shading reflects chronic navigational patterns established through socialization, institutional constraints, or developmental history.

These genesis types are not mutually exclusive; an agent may exhibit protective root-shading, traumatic shading of specific outer positions, and structurally-conditioned shading of certain QRS sectors simultaneously.

2.5.4. Trajectory Notation with Shading

RA notation accommodates shading through

case distinction: significant positions appear as uppercase (

), shaded positions as lowercase (

). Optionally,

shading bars group continuous sub-threshold segments:

A trajectory with shaded transit appears as:

Here the agent navigates through and without phenomenal registration, achieves significance at , then returns to significant . The lowercase notation indicates that the initial outward movement occurred infrastructurally—the agent did not experience “passing through” these positions.

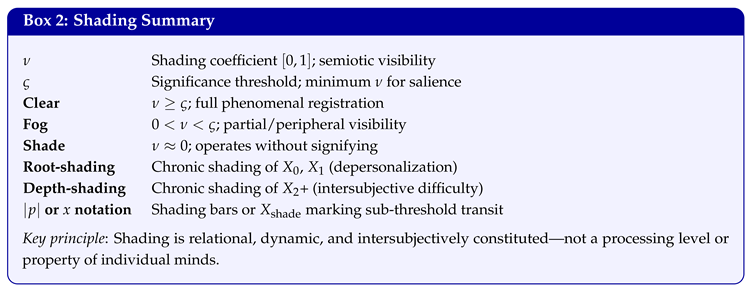

False navigational necessities.

Shading configurations can create the phenomenological illusion that certain external positions are

required for navigation. Consider an agent who has internalized a prejudicial category about their identity. Their

experienced trajectory appears as:

“I must accept being

to reach my social self.” But the

actual trajectory is:

The shading of inner positions ( through ) renders them phenomenally invisible, creating the illusion that the external position is the origin of social navigation rather than a detour. What remains hidden is that the direct path——was available all along. The prejudice did not enable social navigation; it occluded awareness of the agent’s own navigational capacity.

This is the operational mechanism of what Kastrup [

22] calls “conflating abstraction with empirical observation”: the abstract category (prejudice at

) is mistaken for experiential ground, while actual experiential ground (

,

) operates infrastructurally without signifying.

Shaded vs. direct trajectories.

Consider two agents navigating from

to

:

| Pattern |

Trajectory |

| Agent A (full significance) |

|

| Agent B (root-shading) |

|

Both trajectories traverse the same positions. Agent A experiences the full navigational arc—embodiment (), self-identification (), then interlocutor orientation (). Agent B experiences “arriving at” without the phenomenal sense of having traversed inner positions. The informational costs are comparable (both trajectories incur across the same distance), but the phenomenological profiles differ radically.

Analytical implications.

Shading notation enables analysts to distinguish:

Trajectory length vs. significance range: An agent may traverse long trajectories while achieving significance at only a subset of positions.

Cost without telemetry: Shaded positions contribute to without the agent’s phenomenal awareness—maintenance costs accrue in regions the agent cannot directly monitor.

Situational variation: The same trajectory structure may exhibit different shading configurations across communicative contexts.

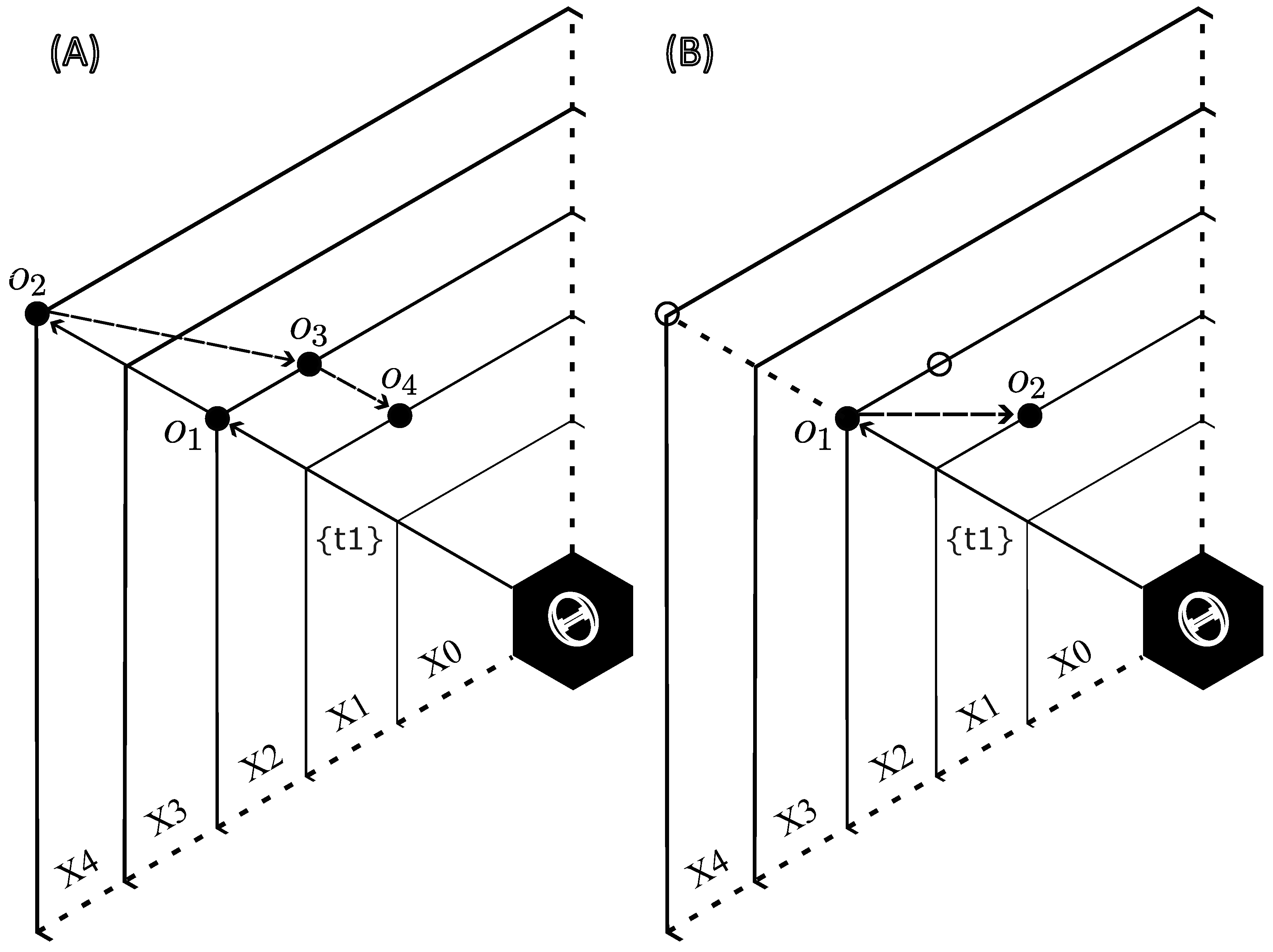

Figure 4 illustrates this contrast. Panel (A) shows an extended trajectory with multiple significant positions; Panel (B) shows a trajectory of similar extent where intermediate positions are shaded, producing apparent “directness” despite equivalent navigational distance.

Figure 4.

Shading contrast in trajectory visualization. (A) Extended trajectory with full significance across positions . (B) Trajectory of similar navigational extent where intermediate positions (hollow circles) are shaded—the agent experiences only and as significant, though the full arc is traversed infrastructurally.

Figure 4.

Shading contrast in trajectory visualization. (A) Extended trajectory with full significance across positions . (B) Trajectory of similar navigational extent where intermediate positions (hollow circles) are shaded—the agent experiences only and as significant, though the full arc is traversed infrastructurally.

3. Core Notation and Analytical Workflow

This section provides the practical tools for conducting Radial Analysis: the notation system for representing trajectories and the seven-step procedure for systematic analysis.

3.1. Trajectory Notation

RA employs a layered notation system that balances precision with readability:

3.1.1. Basic Trajectory

A trajectory is an ordered sequence of positions:

Each arrow represents a navigational move. The sequence captures temporal ordering without specifying duration.

3.1.2. Position Specification

Positions can be specified at varying granularity:

| Level |

Notation |

Example |

| Area only |

|

|

| Area + sector |

|

|

| Full coordinates |

|

|

Analysts choose granularity based on analytical needs. Exploratory analysis may use area-level notation; precise cost calculation requires full coordinates.

3.1.3. Extended Notation

Lambda specification: Append granularity when relevant:

Sigma marking: Use superscripts for access mode. Ocassionally (

p) can be used instead of (

o) for notational clarity (the latter is preferred):

Shading notation: Positions traversed without navigational significance use bars:

IIP notation: Transition cost markers:

Interface notation: The current interface configuration is .

3.1.4. Notation Reference Table

Table 1 consolidates the notation system.

3.2. The Seven-Step Analytical Procedure

The following procedure operationalizes RA for systematic discourse analysis (see Figure ):

-

Step 1

-

Segmentation

Divide discourse into analytically relevant units. Units may be utterances, turns, gesture phases, or thematic segments depending on research questions. RA does not prescribe segmentation criteria—analysts apply domain-appropriate methods.

-

Step 2

-

Position Identification

For each segment, identify the identity position(s) manifested. Ask: Where is the speaker positioning themselves relative to ? What categorical distinctions are in play? Multiple positions may be relevant for a single segment.

-

Step 3

-

Coordinate Assignment

Assign hexagonal coordinates to identified positions. Use area-level notation () for exploratory analysis; refine to full coordinates when precision is needed. Document assignment rationale.

-

Step 4

-

Trajectory Extraction

Connect sequential positions into trajectories. Note: not every position shift constitutes a new trajectory point. Analysts distinguish surface positions (integers) from granular displacement (decimals) based on whether the shift represents categorical movement or internal elaboration.

-

Step 5

-

Metric Calculation

Calculate relevant metrics:

Total trajectory cost:

Average distance from

-centrality: proportion of positions at or

profile: maintenance cost distribution

Shading configuration: significance range assessment

Comparison with “direct” alternatives

-

Step 6

-

Granularity Assessment

Determine operating parameters: Is navigation occurring at or ? What mode predominates? Are there shifts during the trajectory? Note IIP constraints encountered. Assess shading: which positions achieve significance ()?

-

Step 7

-

Interpretive Synthesis

Integrate findings into analytical narrative. What do the trajectorial patterns reveal? How do they relate to the phenomenon under study? What would alternative trajectories have looked like?

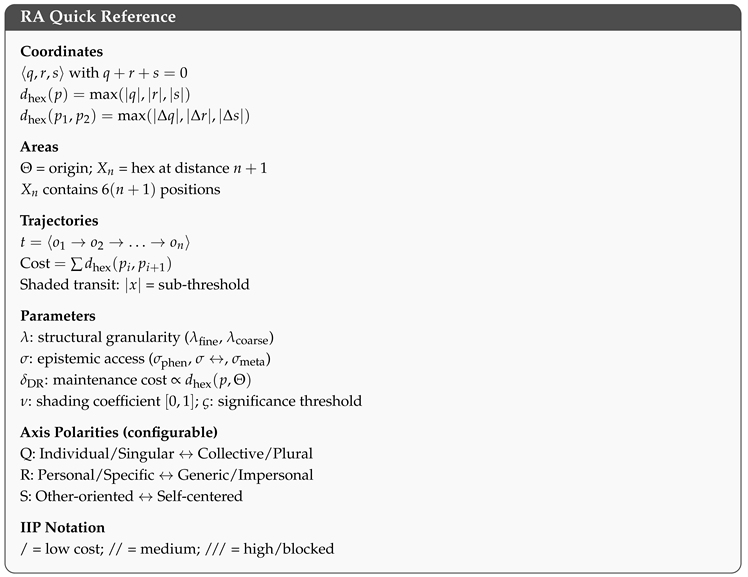

3.3. Quick Reference Card

4. Applications

This section demonstrates RA through five application domains, progressing from established linguistic territory (deixis) through identity dynamics to recent theoretical extensions (epistemic appropriation), concluding with comparative evaluation.

4.1. Personal Deixis

Personal pronouns provide an intuitive entry point for RA. Consider the English pronoun system:

| Pronoun |

Area |

Typical Sector |

Notes |

| I |

|

|

Individual, self-centered |

|

you (sg.) |

|

|

Individual, other-oriented |

|

we (inclusive) |

–

|

|

Collective, spanning self/other |

| they |

|

|

Collective, other-oriented |

|

one (generic) |

+ |

|

Generic/impersonal |

Analytical example.

A speaker recounting a personal experience might produce:

“I was walking home when you know how it gets dark early? And then one just feels unsafe...”

This movement from specific first-person () through addressee appeal () to generic positioning () accomplishes universalization of personal experience. The trajectory cost (approximately 4 hexagonal steps) quantifies the discursive work required.

The power of RA emerges when analyzing atypical trajectories. A speaker who begins at and moves inward (“One sometimes wonders... I mean, I wonder...”) performs a different kind of identity work—particularization rather than universalization—with different informational costs and rhetorical effects.

IIP asymmetry in person deixis.

The transition from first to third person () typically exhibits lower IIP cost than the reverse (). Universalizing personal experience is discursively unmarked; particularizing generic claims requires justification. This asymmetry—invisible to categorical analysis—becomes tractable through IIP notation.

4.2. Temporal Reference

Linguistic research has long treated the temporality of language as a composite of discrete systems. The canonical tradition separates tense from aspect [

5,

6], aspect from modality [

4], and evidentiality from both—establishing it as an autonomous grammatical category only in languages that mark information source obligatorily [

1]. Even integrationist frameworks like grammaticalization theory, which trace how these systems converge diachronically, preserve the analytic separation: TAM categories

become related through semantic drift, not

are inherently facets of unified navigational dynamics.

The consequence is a modular architecture where each domain receives its own descriptive apparatus—layered onto syntactic, morphosyntactic, semantic, and pragmatic “levels” that must then be reconciled through interface mechanisms. Epistemic stance enters as pragmatic overlay; evidentiality appears as optional grammatical elaboration in select languages; the prospective-retrospective axis reduces to tense morphology—until typological evidence accumulates and the apparatus must be revised: the English “future,” it turns out, is not a tense at all [

4,

26]. RA inverts this architecture: rather than starting from separated components that require post hoc integration, it begins from

navigation—the continuous trajectory through informational space—and derives apparent modularity as analytic abstraction from integrated phenomenological dynamics. The axis configuration introduced in §

2.3 provides the geometric scaffold for this integration.

Temporal deixis operates on analogous geometric principles, with the Q axis reconfigured for temporal rather than personal deixis:

| Temporal Expression |

Area |

Characterization |

|

now, present moment |

–

|

Experiential immediacy (low ) |

|

today, yesterday

|

|

Proximal temporal reference |

|

last year, in 2020

|

|

Medial temporal distance |

|

in ancient times, always

|

+ |

Distal/generic temporal reference (high ) |

This radial organization gains analytic precision when combined with the TAM axis configuration (§

2.3):

Q axis (temporal orientation): Prospective () versus retrospective () navigation from the experiential present.

R axis (aspectual boundedness): Bounded/perfective (

) versus unbounded/imperfective (

), following [

24]’s construal of event contour.

S axis (epistemic grounding): Anchored (, experiential trace, direct evidence) versus unanchored (, inference, projection, counterfactual).

Crucially, radial distance (–) indexes phenomenological proximity to the experiential present as an orthogonal parameter: one can be temporally distant () yet epistemically anchored (), or temporally proximal () yet epistemically unanchored (). This orthogonality—impossible to represent in linear tense models—enables formal analysis of cross-linguistic TAM systems without collapsing tense, aspect, and evidentiality into a single dimension.

The key insight is that temporal expressions are not merely locating events in time but

navigating the speaker’s relationship to temporal structure. “Yesterday” and “24 hours ago” may denote identical clock-time yet occupy distinct trajectorial positions—formalized through the axis configuration:

| Expression |

Area |

Q |

S |

Characterization |

| yesterday |

|

|

|

Retrospective, experientially anchored |

| 24 hours ago |

|

|

|

Retrospective, metrically indexed |

Both expressions navigate retrospectively () at comparable radial distance (), yet differ along the epistemic grounding axis: “yesterday” anchors to the lived experiential rhythm (waking, sleeping, the phenomenological “shape” of a day), while “24 hours ago” indexes measured duration detached from that rhythm. The profile differs accordingly: “yesterday” requires less maintenance when embedded in narrative because it aligns with the speaker’s experiential structure; “24 hours ago” demands explicit anchoring (“24 hours ago—around 3 pm—we were still...”) to stabilize the reference.

This distinction—invisible to analyses that reduce both expressions to “past reference”—emerges naturally when temporal navigation operates across orthogonal parameters. Aspectual boundedness (R axis) adds further discriminability: “I was working yesterday” (, imperfective) versus “I finished yesterday” (, perfective) occupy the same region but differ in R-polarity, capturing what traditional accounts require separate morphosyntactic modules to represent.

and temporal reference.

Positions closer to the experiential present exhibit lower ; distant temporal references require more maintenance. This explains why speakers often “anchor” distant events through proximal framing: “Back in 1985—I remember it clearly—we were living in...” The trajectory momentarily returns toward to stabilize the high- distant reference.

4.3. Identity Navigation: -Return Dynamics

The framework posits as an attractor—a baseline configuration toward which trajectories gravitate between coded positional excursions. But this is not merely theoretical stipulation; it generates testable predictions about navigational patterns in identity discourse.

4.3.1. The Attractor Hypothesis

If functions as experiential attractor, we should observe:

Return frequency: Trajectories should exhibit periodic movement toward inner areas (–) between outer-area excursions.

Cost asymmetry: Outward movement (toward +) should require more discursive work than inward movement.

Stabilization patterns: Positions closer to should exhibit lower —less maintenance effort required.

4.3.2. Empirical Signature: Navigating Institutional-Community Boundaries

Consider identity navigation in contexts where speakers must coordinate between institutional and community positionings. Data from ongoing research with Yoreme (Mayo) indigenous educators in northwestern Mexico reveals consistent patterns.

4

A Yoreme (Mayo) teacher, interviewed at the Autonomous Indigenous University of Mexico (UAIM) in Mochicahui, Sinaloa, produces the following reflection on navigating institutional and community identity:

5

“From, like, as yori, so then, and there it’s a game, and it’s beautiful, it’s beautiful, it’s good, yes. When they invite you to participate in an event, well, you sing, you participate as yori. Ah, well, I sing as yori, I sing songs as yori, and so on. There are yoremes who know songs as yoremes, and know songs as yoris, and so on. [...] You feel the appreciation of the yori, you feel it inside yourself, you can say, ah, well, it gave me an opportunity, they opened the world of yoris for me, well then, we have to participate as yoris.”

This segment—originating from the fieldwork that motivated the development of HEXID geometry—serves as the canonical worked example for RA methodology.

Position inventory.

The discourse reveals seven distinct identity configurations, each mappable to specific phex coordinates (see

Figure 2):

| ID |

Expression |

Hex |

Phex |

Characterization |

| (1) |

“you feel it,” “yourself” |

|

|

Generic first-person (impersonal self-reference) |

| (2) |

“as yori” (self-perf.) |

|

|

Yoreme performing institutional role |

| (3) |

“yoremes” (generic) |

|

|

Third-person community reference |

| (4) |

“as yoris” (skill) |

|

|

Transitional competence |

| (5) |

“the yori” (other) |

|

|

Counter-exonymic Other at

|

| (6) |

“as yoremes” (meta) |

|

|

Meta-performative self-awareness |

oordinate rationale.

Position (1) (generic first-person) receives : the axis marks impersonal/generic epistemic stance—self-reference without individuated content (“one feels it,” “you feel it inside yourself”). This is not , which has no linguistic expression, but the closest codable position to experiential baseline. Position (2) (yori-performance) receives : marks collective role, epistemic anchoring (“knowing the rules”), personal engagement (“it’s beautiful”). Position (5) (stereotypical yori) lands at with : the counter-exonymic move alienates the unmarked dominant to third-person distance while maintaining positive stance.

Distance calculations.

Using

:

| Transition |

Coordinates |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

1 |

Accumulated trajectory cost.

Averaging 2.3 units per transition across 7 coded moves, this moderate cost reflects navigational fluency: the speaker traverses multiple identity configurations while maintaining proximity to inner positions. The implicit -returns between utterances—not calculated here—function as cost resets, dissipating informational load accumulated at outer positions and preventing entrenchment at high-maintenance configurations.

Against polar identity models.

A critical finding emerges from examining

which axes the trajectory traverses. Dualist identity frameworks would predict navigation concentrated along a single Yoreme↔Yori axis—presumably the

q-axis (individuation/collectivity). The data reveal otherwise:

| Axis |

Transitions with |

Proportion |

|

q (individuation) |

3 |

33% |

|

r (epistemic familiarity) |

2 |

22% |

|

s (stance/proximity) |

4 |

44% |

Only 33% of significant displacements occur along the q-axis that would correspond to stereotypical Yoreme↔Yori polarity. The remaining two-thirds traverse r and s dimensions—epistemic familiarity and affective stance—invisible to dualist frameworks. The speaker navigates not between ethnic poles but through a multidimensional space where epistemic positioning (“knowing the rules,” “knowing songs as yoremes”) and affective stance (“it’s beautiful,” “you feel the appreciation”) carry as much navigational weight as collective identification.

This distribution provides empirical evidence against polar identity models. What dualist analysis would code as “negotiating between Yoreme and Yori identities” is better characterized as fluid multidimensional navigation where the supposed poles rarely serve as actual trajectory endpoints. The “world of yoris” (“me abrieron el mundo de yoris”) is not an opposing territory but a navigable region within the same hexid—entry does not require exit from Yoreme positioning.

Shading and navigational concentration.

The trajectory exhibits characteristic concentration: positions cluster in – (6 of 7 coded positions), with only position (5) extending to . This is not methodological artifact but navigational reality—the speaker maintains most movement within accessible inner and middle-distance positions while outer institutional categories (+) remain relatively shaded. The yori-as-category (position 5) achieves momentary salience but does not dominate; it emerges, serves its counter-exonymic function, and yields to inner-position return.

Contrast this with appropriated navigation (§

4.4), where institutional categories saturate the hexid’s outer regions, blocking return toward

and forcing extended occupation of high-

positions. The Yoreme speaker’s fluency consists precisely in

not getting trapped at

+.

This

-centrality of approximately 0.29 indicates that while the speaker navigates through generic self-reference (

,

), the bulk of navigation occurs at

—middle-distance positions where identity work is performed. High

-centrality would indicate a speaker who rarely ventures beyond minimal selfhood; very low

-centrality would indicate entrapment at outer positions. The Yoreme speaker’s moderate value reflects active engagement with identity categories while maintaining accessible return paths toward inner positions. This pattern—identity as

oscillation rather than

location—aligns with Yeung’s ([

34]) finding that identity coherence emerges through trajectory patterns across discourse, not through stable categorical occupation.

Methodological significance.

This worked example demonstrates RA’s analytical sequence: (1) segment discourse into navigated positions, (2) assign phex coordinates via axis semantics, (3) calculate hexagonal distances, (4) derive summary metrics enabling cross-context comparison. The calculations are reproducible—another analyst applying identical rationale derives comparable metrics. But beyond methodological reproducibility, the example illustrates RA’s theoretical yield: phenomena invisible to categorical analysis (multidimensional navigation, shading concentration, polar-model falsification) become tractable through geometric formalization.

4.3.3. Multimodal Coordination

Identity navigation operates across modalities simultaneously. When speakers produce discourse, gesture, gaze, and body orientation coordinate as parallel trajectorial streams sharing synchronization points.

Analytical example.

A speaker says “We need to move forward” while:

Gesturing with both hands in a gathering motion (collective-oriented)

Gazing at interlocutors (second-person engagement)

Leaning forward bodily (spatial forward = temporal forward)

Each modality traces a distinct trajectory:

The analytical question: How do these trajectories converge or diverge? Convergent multimodal trajectories signal emphatic positioning. Divergent trajectories (speech in while gesture remains in ) may signal hedging, irony, or interactional trouble. RA’s thread-based formalism naturally captures such simultaneity without requiring separate “gesture modules” bolted onto speech analysis.

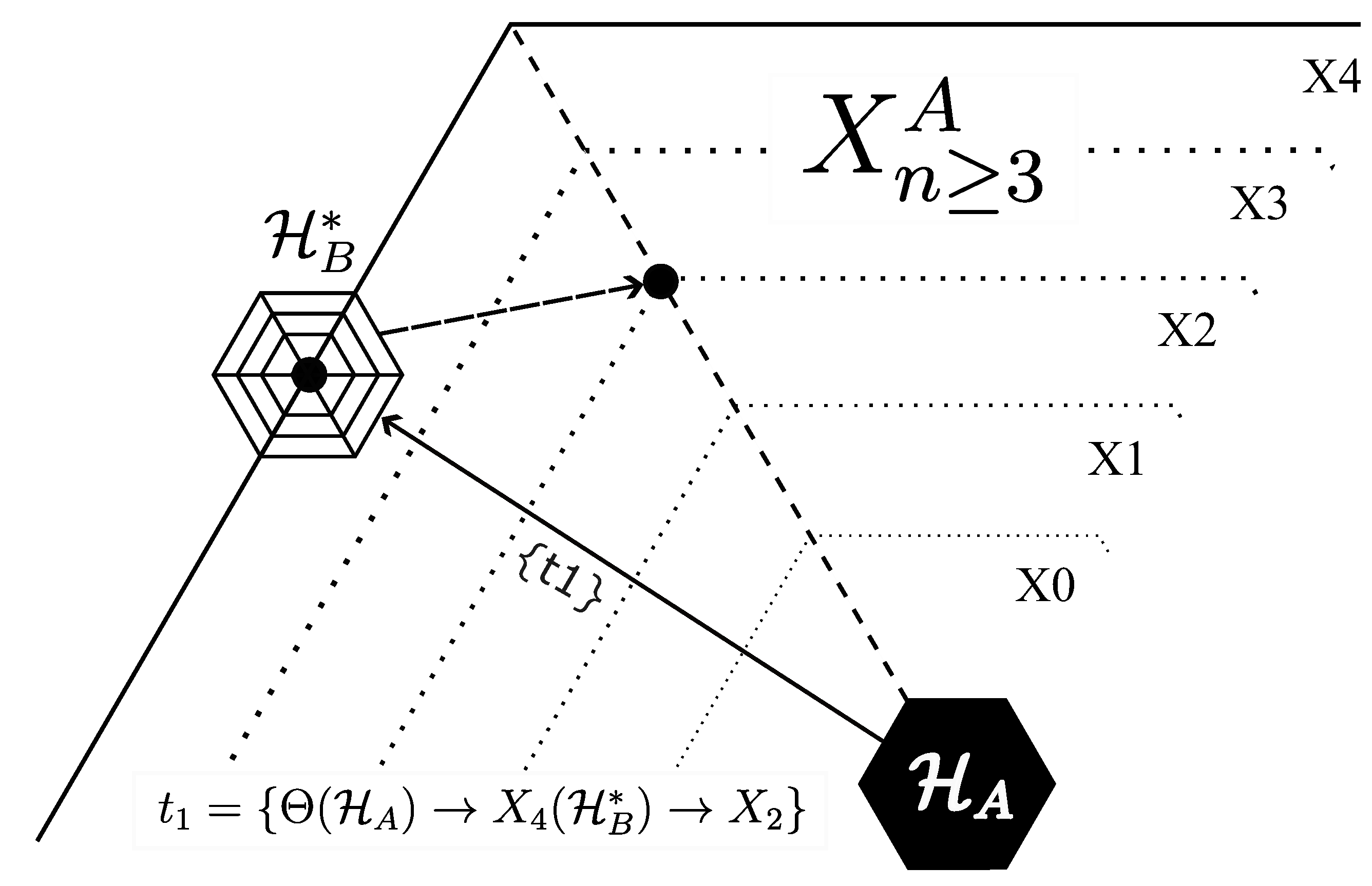

4.4. Epistemic Appropriation

Recent work on epistemic appropriation [

14] demonstrates RA’s capacity to analyze power asymmetries in institutional encounters. The core phenomenon: when a professional (clinician, educator) navigates identity categories in ways that constrain the client/student’s own navigation.

4.4.1. Operation 1: Flattening

Consider a diagnostic encounter where a clinician says: “Your autism makes social situations difficult.”

From the clinician’s hexid, “autism” operates as a categorical tool at (impersonal, other-oriented). But this utterance projects onto the patient’s hexid, where it lands at (first-person identity)—but with the structural properties of the clinician’s (coarse-grained, categorical).

The result is

flattening: the patient’s fine-grained self-understanding (

) is overwritten by the clinician’s categorical structure (

). Formally:

The patient’s navigational options within their own are reduced to the distinctions available in the diagnostic category. The patient does not appear as possessing an autonomous phenomenology; rather, they appear as failing to fit the clinician’s categories.

4.4.2. Operation 2: Internalization

More insidiously, repeated encounters can produce internalization: the construction of mirror positions () within the subalternized agent’s hexid that reproduce the dominant agent’s categorical structure.

The informational cost is calculable. Where direct self-affirmation might cost 2 hexagonal steps (

), the internalized trajectory requires detour through external validation:

This 2.5–3× overcost formalizes the “extra work” that marginalized subjects perform to achieve the same identity positions that dominant subjects reach directly.

Figure 5 schematizes the geometric mechanics underlying both operations. The trajectory

captures the dominant agent’s navigational move: accessing the Other not as autonomous center but as compressed object within one’s own terrain.

4.4.3. Operation 3: Trajectorial Refraction

Resistance to epistemic appropriation operates not through simple refusal but through trajectorial refraction—navigation that necessarily traverses dominant categories before emerging at angles that contest them.

The refraction mechanism.

Consider counter-exonymy: the trajectory toward endonyms (

Yoreme,

Deaf,

autistic) necessarily passes through exonymic traces (“Mayo,” “hearing-impaired,” “person with autism”) before emerging at a refracted angle. The trajectory does not avoid the dominant saturation but

traverses and transforms it:

Segment traces necessary movement through the mirror position —a node saturated by dominant SSPs. From this node, segment emerges at with angular displacement. Crucially, and are not separate trajectories but segments of a single navigational event.

Why refraction requires collective infrastructure.

Individual resistance is thermodynamically expensive: the agent must maintain counter-saturations against massive institutional recurrence. Collective resistance—Deaf cultural institutions, neurodivergent communities, indigenous assemblies—distributes this maintenance burden. The refracted position gains stability not through individual effort but through shared SSPs that make resistant trajectories mutually legible.

The -return constraint.

A critical finding from formal analysis [

14]: sustained outer-ring occupation produces impeded return to minimal selfhood. The agent can still access

, but the path now routes through

, fragmenting self-experience. This is not psychological fragmentation but geometric constraint: the saturated mirror positions have become obligatory waypoints.

4.4.4. Operational Indicators

RA enables detection of epistemic appropriation through observable patterns in professional discourse:

Indicators of flattening:

-invisibility: Professional discourse lacks language recognizing the subject’s experiential authority. Subject self-reports are treated as data requiring interpretation rather than testimony about phenomenological reality.

Categorical override: When subject account conflicts with professional categories, the category prevails (“The test shows X” overrides “I experience Y”).

Outer-area anchoring: The professional consistently positions the subject in – regions, never granting – status.

Asymmetric evidence requirements: Subject’s claims require corroboration; professional’s claims are presumed valid.

Indicators of internalization:

Self-reference through dominant categories: Subject spontaneously describes self using deficit-coded vocabulary (“my disorder,” “my limitations”) without critical framing.

Post-encounter collapse: Immediate fatigue or distress upon exiting the institutional encounter, revealing metabolic cost of maintaining mirror arrangements.

Blocked -return: Subject reports difficulty accessing “authentic self”—only institutional positions feel navigable.

4.4.4.3. Indicators of -orientation:

(Compliant): Categories treated as transparent reality; subject’s deviation interpreted as subject’s failure.

(Desaturating): Momentary suspension of categorical override to re-anchor encounter in subject’s lived trajectory; professional treats subject’s testimony as primary access to -based reality.

(Meta-reflexive): Categories recognized as tools with limitations; willingness to revise institutional framing based on subject testimony.

These indicators transform intuitive observations about “internalized oppression” into operationalizable analytical categories with specific trajectorial signatures.

4.5. Comparative Advantage

Table 2 synthesizes RA’s advantages relative to alternative frameworks across the phenomena demonstrated in this section.

The integration principle.

RA’s power derives not from handling any single phenomenon better than dedicated frameworks, but from handling all within unified architecture. Person, space, time, stance, modality, and power asymmetry operate in the same coordinate system, enabling analysis of their interactions without theoretical patchwork.

A speaker’s shift from “I” to “one” involves personal deixis, epistemic stance (), register elevation, and social positioning—simultaneously. Categorical approaches require separate analyses later reconciled; RA tracks the single trajectory through multidimensional space. The framework’s resistance to analytical collapse stems from a foundational principle: dissipation governs coherence, not accumulation. Through mechanics, RA formalizes how discourse maintains coherence through selective trace preservation rather than cumulative archiving.

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological Advantages

RA offers four distinctive advantages over existing frameworks:

(1) Integration without reduction. Where other approaches analyze deixis, identity, modality, and power separately—requiring coordination across incompatible frameworks—RA models all as navigational dynamics within a unified geometric substrate. The framework is genuinely integrative rather than merely eclectic.

(2) Calculable metrics. Hexagonal distance, , and trajectory cost provide principled quantification. Claims like “this trajectory is costly” become testable assertions with specific numerical values. This calculability enables comparative analysis across speakers, contexts, and languages.

(3) Phenomenological grounding. The experiential zero-point () anchors analysis in lived experience. Navigation is always from somewhere—the agent’s own baseline—preserving the first-person perspective that many cognitive frameworks eliminate.

(4) Formal without being formalist. RA’s mathematics (hexagonal coordinates, distance formulas, ) serve analytical purposes without demanding that users adopt controversial ontological commitments. The geometry is a tool, not a claim about neural architecture.

5.2. Extensions

Several domains invite immediate extension:

Sign language analysis. RA’s thread-based formalism naturally captures simultaneous multi-articulator dynamics: dominant/non-dominant hand coordination, facial grammar, spatial reference systems. Sign languages pose profound challenges to linear conceptions of meaning; RA’s trajectory architecture may prove particularly apt. The insight that “gestures and signs are phrases not words” [

12] aligns with RA’s trajectorial ontology.

Computational corpus analysis. Automated trajectory extraction, heatmap visualization of position frequency distributions, and statistical modeling of transition probabilities open pathways for large-scale empirical validation across typologically diverse languages.

Clinical and educational intervention. The epistemic appropriation framework suggests concrete intervention targets: practitioners can monitor their own trajectorial patterns for flattening tendencies; training can cultivate awareness of / mismatches; institutional protocols can be redesigned to reduce IIP asymmetries.

5.3. Limitations

Four limitations warrant acknowledgment:

(1) Empirical validation. While RA provides analytical tools, systematic empirical validation—demonstrating that trajectory metrics predict behavioral or interactional outcomes—remains ongoing work.

(2) Operationalization challenges. Detecting shifts or determining operating in real discourse requires interpretive judgment. The framework provides vocabulary but not algorithmic decision procedures.

(3) Cultural specificity. The QRS axis assignments (individual/collective, personal/generic, self/other) reflect particular cultural categories. Cross-cultural application requires axis reconfiguration, not merely translation.

(4) Learning curve. The hexagonal coordinate system, while mathematically simple, requires familiarization. Analysts accustomed to categorical frameworks may find the trajectorial perspective initially counterintuitive.

6. Conclusion

Radial Analysis transforms radial category theory from static structural description into dynamic trajectory modeling. By embedding identity navigation within hexagonal geometry, RA provides researchers with tools to track how speakers move through meaning space, what these movements cost informationally, and why certain patterns emerge rather than others.

Three contributions distinguish this framework:

Geometric formalization: The SpiderWeb architecture (Hexid/Hex/Phex) provides precise vocabulary for phenomena that other frameworks describe only vaguely. , SSP, IIP, and shading concepts enable operational analysis of stabilization, constraint, and visibility.

Calculable metrics: Hexagonal distance, trajectory cost, -return frequency, and significance range enable quantitative comparison, transforming impressionistic observations into testable claims.

Power dynamics integration: The epistemic appropriation extension demonstrates how RA captures asymmetric intersubjective dynamics—flattening, internalization, and trajectorial refraction—invisible to categorical approaches.

RA invites application wherever researchers seek to understand how subjects navigate structured spaces moment-by-moment—not merely where they position themselves, but how they move, what that movement costs, and what patterns of coherence emerge through navigational dynamics unfolding in real time.

The framework’s significance extends beyond methodological innovation to foundational questions about semantic ontology. If meaning emerges through navigational dynamics rather than categorical membership, then temporal architecture becomes constitutive—not merely how speakers express pre-existing concepts but how meaning comes to be through trajectorial selection under informational constraint. By bridging cognitive linguistics’ structural insights with T&T’s process ontology, Radial Analysis offers methodology for rendering implicit navigation explicit, subjective experience tractable to formal analysis, and the temporal unfolding of meaning-making visible as the dynamic process it fundamentally is.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This theoretical and methodological paper did not involve human subjects or data collection.

Data Availability Statement

This is a methodological paper. No new empirical data were generated. All cited sources are publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Claude (Anthropic) was used to assist with document preparation, formatting, and refinements. The framework, concepts, and original development are entirely the work of the author.

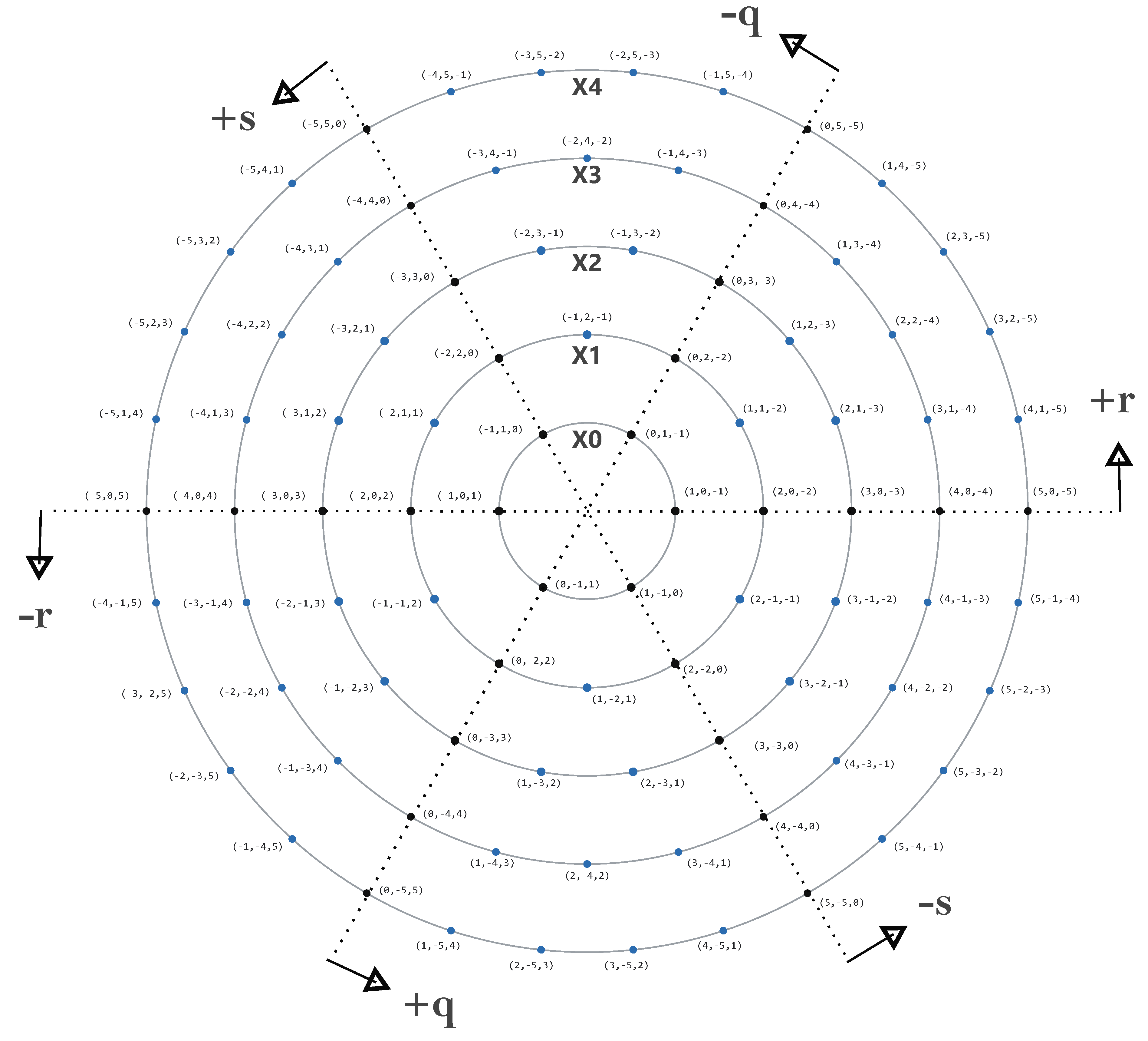

Appendix A. Hexid Coordinate Reference

Figure A1 provides an expanded radial representation of the hexid coordinate system, useful for verifying phex assignments and visualizing trajectory paths across the full

–

range.

Figure A1.

Radial coordinate reference for the hexid system. All phex positions from

through

are shown with their cubic coordinates

. The circular layout emphasizes radial distance from the experiential baseline while preserving angular sector relationships. Use in conjunction with

Figure 2 for trajectory analysis.

Figure A1.

Radial coordinate reference for the hexid system. All phex positions from

through

are shown with their cubic coordinates

. The circular layout emphasizes radial distance from the experiential baseline while preserving angular sector relationships. Use in conjunction with

Figure 2 for trajectory analysis.

References

- Aikhenvald, A. Y. Evidentiality; Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Andries, J.; Broné, G.; Feyaerts, K. Multimodal stance-taking in interaction: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Communication 2023, 8, 1187977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, H.; Bonami, O. Linguistic change and the logic of ideology. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Cognitive Modeling and Computational Linguistics, 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, J. L.; Perkins, R.; Pagliuca, W. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world; University of Chicago Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, B. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems; Cambridge University Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, B. Tense; Cambridge University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Ö. The grammar of future time reference in European languages. In Tense and aspect in the languages of Europe; Dahl, Ö., Ed.; Mouton de Gruyter, 1995; pp. 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, J. W. The stance triangle. In Stancetaking in discourse; Englebretson, R., Ed.; John Benjamins, 2007; pp. 139–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. CLOUD: Language, identity and meaning as fields of information; Peter Lang, 2025a. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. Dissipative Representations: A Non-Dualist Framework for Language and Identity Research (No. asdhx_v2). SocArXiv. 2025b. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/asdhx_v2/.

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. Trace & Trajectory Semantics: Meaning Dynamics in Pre-Representational Space (No. 2025102495). Preprints 2025c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L. Gestures and signs are phrases not words: A high definition account. In Manuscript in preparation; 2025d. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar L.-Dellamary, L.; Cortés Aguilar, S.; Velarde Inzunza, J. de J. Nombrar al otro: Contra-exónimos y resistencia identitaria en comunidades marginadas. Cuadernos de Lingüística de El Colegio de México 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]