1. Introduction

Traditionally, the Humanities rely on archival research, textual analysis, and interpretative methodologies, often centered on physical documents, artifacts, and linear narratives. However, digitization tendencies in the Humanities introduce computational tools and archiving principles, availing networked scholarship as a new way of engaging with cultural texts, historical records, and linguistic data. Techniques such as text mining, GIS mapping, and digital visualization enable scholars to analyze vast corpora of texts, trace patterns across historical periods, and reconstruct lost or fragmented knowledge. By integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches, DH offers new insights previously inaccessible through traditional Humanities methodologies alone.

Another significant contribution of digitization is the liberation of access to historically accumulated cultural knowledge, which often remains on the margins of advanced scholarship. Digital archives, open-access platforms, and interactive databases allow scholars, students, and the general public to engage with historical documents, literary texts, and cultural artifacts that were once confined to specific institutions. This accessibility fosters greater inclusion into Humanities research, allowing it to incorporate underrepresented voices and marginalized histories into scholarly discourse. Furthermore, DH methodologies facilitate collaborative research across disciplines, bridging gaps between Humanities, Computer Science, and Data Science. Projects in the digitization and computational analysis of epigraphic inscriptions highlight how digital humanities facilitate new interdisciplinary dialogue between linguistic and computational analysis. Examining such artifacts requires broad linguistic insights to trace cultural behavior patterns, reshaping traditional notions of authorship, curation, and scholarly engagement.

Beyond methodology and accessibility, DH is challenging and expanding epistemological frameworks in the Humanities. By exposing biases in digital categorization, questioning the dominance of Western-centric ontologies, and promoting decolonized approaches to knowledge production, DH is reshaping the way cultural heritage and intellectual traditions are represented. For instance, initiatives that digitize non-Western scripts, oral histories, and indigenous knowledge systems counteract the Eurocentric biases that have long shaped Humanities scholarship. By leveraging machine learning, digital archives, and community-driven metadata practices, DH is not merely supplementing traditional Humanities—it is actively redefining how we engage with history, literature, language, and culture in a networked, data-driven, and globally interconnected world.

Preserving Ukrainian cultural heritage has become increasingly critical in recent years, especially amid ongoing conflicts like the Russo-Ukrainian War. The deliberate destruction of cultural monuments, combined with historical efforts—such as Soviet-era policies of russification and the removal of artifacts tied to Ukrainian identity—has posed a significant threat to the country’s heritage. Studying Ukrainian epigraphy within digital frameworks necessitates engagement with Heritage Studies, Semiotics, and Sociolinguistics, as these disciplines offer critical insights into how cultural artifacts are encoded and preserved. Heritage studies emphasize the significance of inscriptions as material records of historical consciousness, while Semiotics provides tools to analyze their symbolic and social-communicative functions. Sociolinguistic approaches, in turn, highlight the intersection of language, identity, and cultural transmission, allowing for a deeper understanding of how inscriptions conceptualize collective memory. By integrating these perspectives, digital epigraphy can stretch beyond cataloging objectives to actively preserve the culture-specific categorization embedded in Ukrainian inscriptions.

In this context, a key concern is the digital standardization of cultural epistemology, which interrogates how classification and metadata systems influence the perception of epigraphic traditions on a global scale. Data classification through ontologies, vocabularies, and metadata—facilitates accessibility and categorizes contextualized interpretation of inscriptions. Western European classification systems, developed primarily for Greco-Roman traditions, may impose rigid categorizations that fail to accommodate the context-sensitive and fluid nature of Ukrainian epigraphy. Examining how digital infrastructures shape knowledge production is essential to ensuring that Ukrainian inscriptions are integrated into existing systems and represented in a way that respects their cultural specificity and interpretative depth.

Beyond technical concerns, decolonizing cultural heritage is actual, particularly in light of the post-Soviet context liberalization of Humanities and Social Sciences. Notably, the erasure and marginalization of Ukrainian cultural artifacts—historically through imperial policies and, more recently through geopolitical conflicts—underscore the urgency of reclaiming and asserting a distinct cultural identity in digital spaces. By positioning Ukrainian epigraphy within broader discourses of cultural restitution and linguistic justice, this research attempts to expand Eurocentric heritage frameworks and advocates for a more inclusive, polycentric approach to digital preservation. Ensuring that Ukrainian inscriptions are represented with their historical, linguistic, and religious significance intact is not only a matter of scholarly accuracy but also an act of cultural resistance and reclamation.

Unlike Greco-Roman epigraphic traditions, which are often centered on formal, monumental inscriptions for public or state purposes, Ukrainian epigraphy is remarkably diverse and deeply personal to its creators, bringing forward the untold narratives and voices. It includes church

graffiti, commemorative texts, and domestic drawings, reflecting religious devotion, community identity, and everyday life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The destruction and erasure of these artifacts, including epigraphic inscriptions, risk severing future generations from their historical and cultural roots. As primary records of linguistic, artistic, and religious practices, these inscriptions are among the most fragile and vulnerable aspects of Ukrainian heritage. Protecting them is not just about preservation—it’s about safeguarding a tangible link to the past of Ukrainian identity and casting a searchlight on future studies. Recognizing the value of accurate documentation, cultural heritage preservation has been emphasized as an axiological priority, particularly in conflict and globalization[i]. Epigraphy plays a crucial role in shaping cultural memory, as a tangible link between past and present narratives of identity, faith, and historical continuity. Inscriptions are not mere records; they are acts of communication embedded in time, reflecting the values, beliefs, and power structures of the societies that produced them. The ethical dimensions of digital representation arise when these inscriptions are translated into structured datasets, raising questions about who classifies them, how they are contextualized, and whose narratives they represent. In the case of Ukrainian epigraphy, the digitization process must navigate not only technical challenges but also the responsibility of cultural stewardship, ensuring that inscriptions retain their original meanings rather than being reshaped by predefined classification standards. Therefore, a humanities-centered approach to digital epigraphy must critically examine how digital frameworks mediate the transmission of historical knowledge and whose epistemologies they reinforce or obscure.

Beyond their documentary function, inscriptions possess inherent aesthetic dimensions, operating as both aesthetic and pragmatic expressions transcending context settings. Ukrainian epigraphy, deeply rooted in Orthodox Christian traditions, embodies a fusion of language, iconography, and spatial symbolism, making each inscription not only an artifact of linguistic heritage but also an expression of religious devotion, political authority, and social identity. The stylistic elements of inscriptions—their calligraphy, materiality, and integration into architectural and ritual spaces—convey meanings that extend beyond the words themselves. Treating epigraphy only as data risks stripping inscriptions of their visual, material, and experiential richness, reducing them to abstract classifications rather than recognizing them as living cultural texts. A humanities-driven perspective thus calls for a more holistic engagement with epigraphic heritage, one that acknowledges inscriptions as dynamic cultural artifacts that continue to shape and be shaped by historical consciousness. Epigraphy plays a crucial role in shaping cultural memory, serving as a tangible link between past and present narratives of identity, faith, and historical continuity.

In this context, digital preservation has become a powerful tool for safeguarding cultural artifacts and increasing accessibility for researchers and the public. Projects like EAGLE[ii] and FAIR Epigraphy[iii] demonstrate how structured vocabularies and digital preservation can transform the diversity of epigraphic data into standardized catalogs and description standards [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Studies have shown that initiatives like these significantly improve the accessibility, interoperability, and resilience of cultural heritage data.

The EAGLE vocabularies contain over 3,000 concepts divided into seven categories: Material[iv], Execution Technique[v], Type of Inscription[vi], Object Type[vii], Decoration[viii], Dating Criteria[ix], and State of Preservation[x]. These vocabularies were developed based on Greco-Roman digital collections to enhance global accessibility and interoperability [

29]. However, this system contains several challenges, such as a lack of hierarchical structure, duplicate terms, and limited examples.

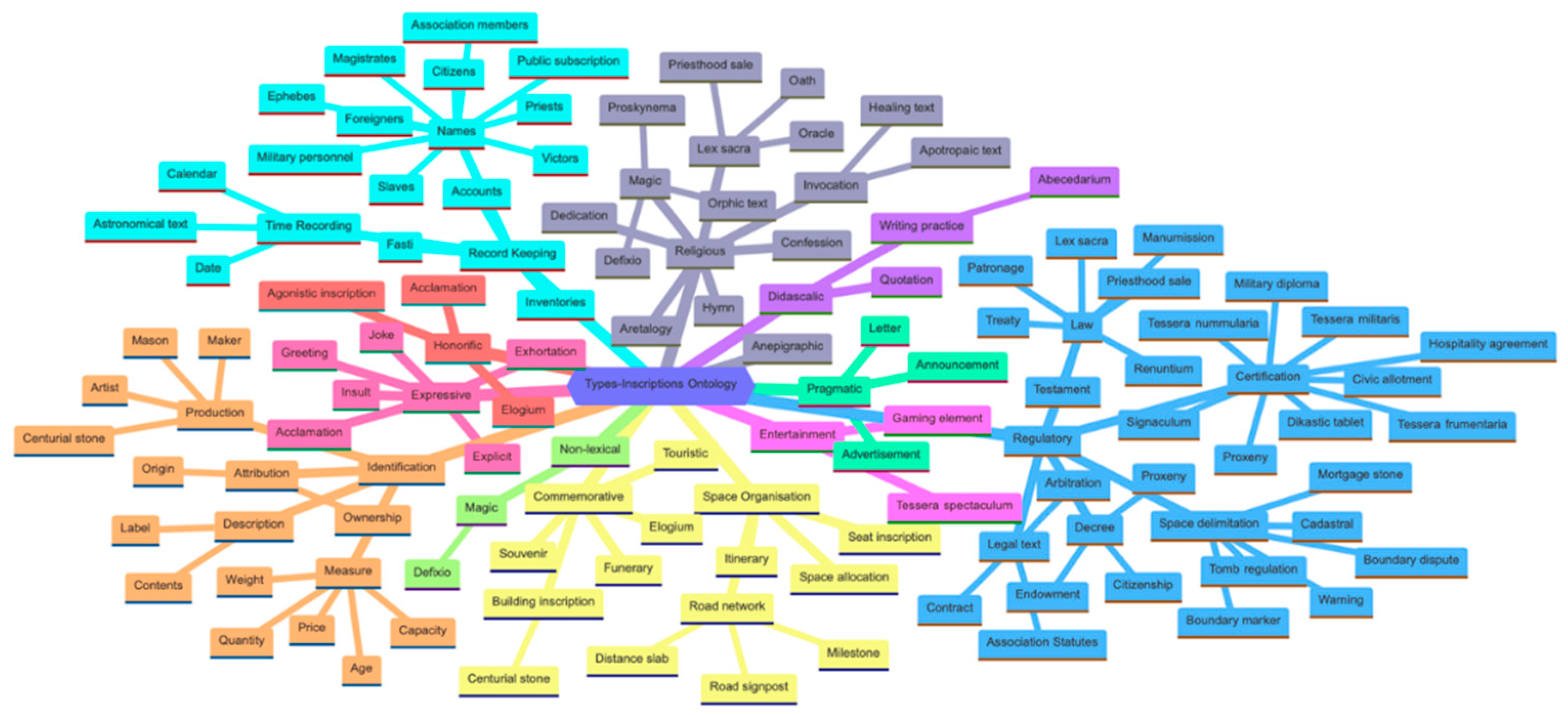

The FAIR Epigraphy Project addresses these challenges and builds on the EAGLE vocabulary while adhering to the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles. This project emphasizes the importance of open-access, machine-readable data and the development of structured ontologies to support interdisciplinary research and data sharing. Notably, the FAIR Types of Inscription Ontology[xi] introduces a hierarchical classification system based on the function of inscriptions. Our research focuses on “Types of Inscription” and “Execution Techniques” vocabularies, as these two categories are inherently epigraphic and do not require interdisciplinary research.

Figure 1.

The FAIR Ontology Types of Inscriptions.

Figure 1.

The FAIR Ontology Types of Inscriptions.

An essential element of digital epigraphy and preservation efforts is using structured vocabularies [

33,

34], particularly those built with the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS). Developed as part of the W3C’s Semantic Web Activity, SKOS provides a standardized, machine-readable framework for organizing and representing knowledge structures. By simplifying knowledge representation, SKOS aligns with Linked Data principles, making it possible to connect datasets across various domains—an essential step for integrating Ukrainian epigraphic terminology into global databases.

Key features of SKOS include its ability to structure concepts, labels, and relationships, ensuring that vocabularies are comprehensive and adaptable for Digital Humanities research. Concepts represent abstract or concrete entities, such as "Пам’ятні написи" (Memorial Inscriptions), while labels provide human-readable terms (preferred, alternative, or hidden). Relationships define connections between concepts, including hierarchical links (broader/narrower) and associative links (related terms). Additionally, SKOS offers mapping properties, such as SKOS:ExactMatch, which facilitate interoperability by linking concepts across different datasets.

For example, an inscription from 14th-century Galicia categorized as "Фрескoві рoзписи" (Fresco Paintings) can be linked to similar categories in European digital libraries, enhancing interdisciplinary research and enriching the study of medieval epigraphy. This interoperability enables researchers to uncover related inscriptions across different regions, offering more profound insights into historical and cultural exchanges and theorization perspectives.

With all the perspectives mentioned, Ukrainian epigraphic heritage remains underrepresented because of limited funds and resources, lack of specialists, and international and interdisciplinary collaboration. Developing a SKOS Ukrainian vocabulary would address this gap. SKOS is specifically suitable for this task due to its flexibility in modeling hierarchical and associative relationships between terms. Moreover, it is compatible with Linked Open Data (LOD) standards and seamlessly integrates with existing international frameworks [

29]. These features ensure that Ukrainian inscriptions—rich in historical and cultural significance—become more accessible and interoperable within global digital archives.

Building a robust SKOS epigraphic vocabulary requires a comprehensive understanding of the cultural categorization models [

36] and the classification principles used, for instance, in Ukrainian academia, both historically and in contemporary research [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. One of the earliest frameworks in Ukrainian academia is Vysotsky’s event-based classification [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], which organizes

graffiti inscriptions into seven thematic categories based on their content, including commemorative inscriptions (Пам’ятні графіті), memorial inscriptions linked to chronicles (Пoминальні надписи, спoріднені з літoписними), wish inscriptions (Благoпoбажальні надписи), autographs (Автoграфічні надписи), inscriptions related to frescoes (Надписи, які стoсуються фресoк), symbolic drawings (Симвoлічні малюнки) (e.g., saints, princely and magical signs, pottery marks, and crosses), and domestic drawings (Пoбутoві малюнки) (e.g., animals, birds, people, and ornamental figures) [

12]. Vysotsky emphasized the interrelation between

graffiti across different categories, highlighting the layered purposes of inscriptions, from commemorating historical events to reflecting personal and collective memory.

Rozhdestvenskaya’s classification [

17,

18] focuses on the linguistic and structural formulae of graffiti, complementing those by Vysotsky, highlighting the prevalence of prayer and memorial inscriptions. These inscriptions often feature formulaic expressions that serve sacred, commemorative, or practical functions, reflecting the dual role of inscriptions in both liturgical practices and individual spirituality.

Rybakov’s foundational approach [

1,

2] categorizes inscriptions based on the material and tools used in their creation, offering insights into the technical diversity and craftsmanship involved in creating inscriptions.

Medyntseva expanded this system by proposing a more object-focused classification, linking

graffiti to its physical and cultural contexts [

1,

4,

5]. Finally, Korniyenko synthesized these approaches into a hierarchical framework, dividing the class of

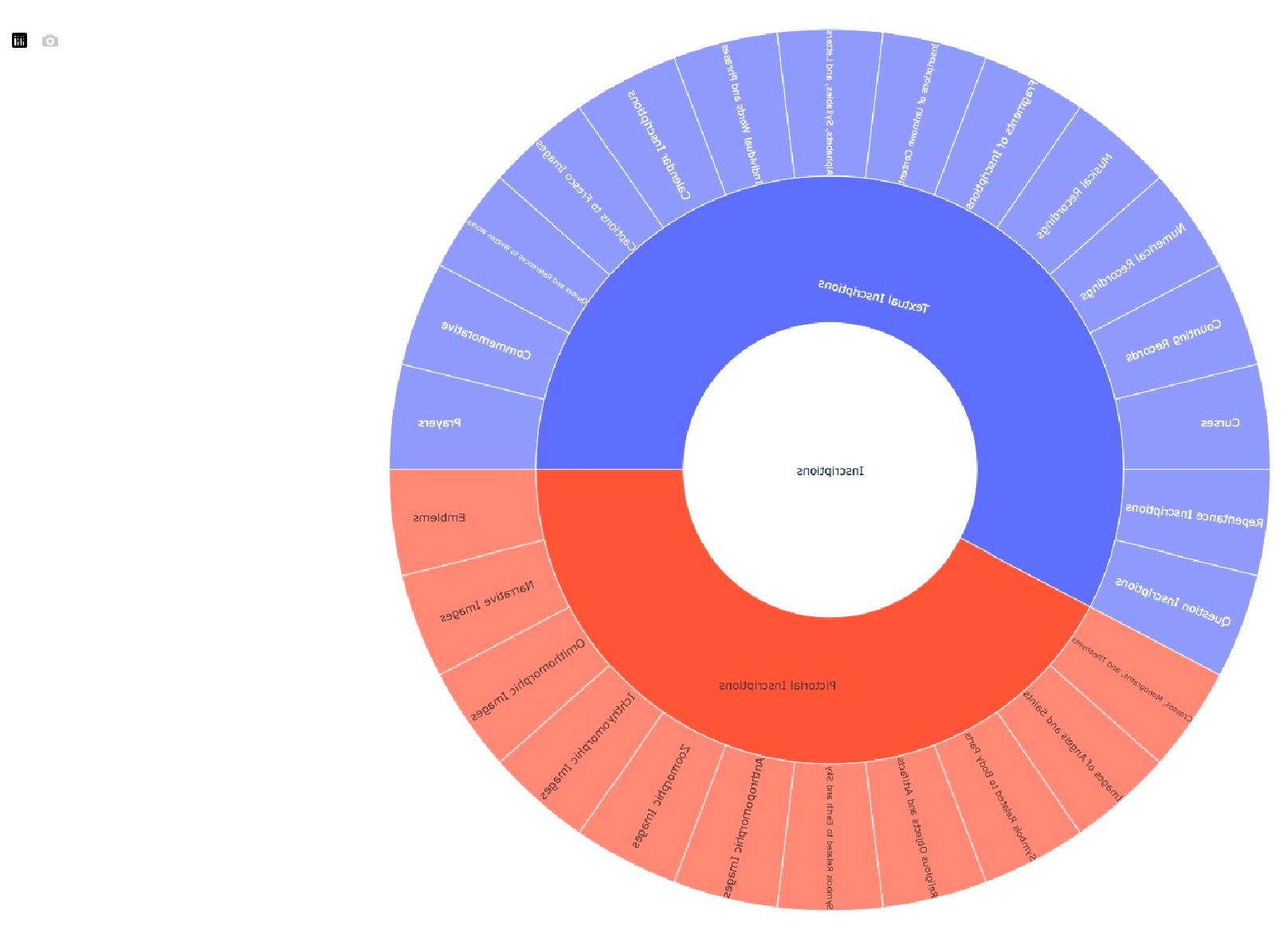

graffiti into textual and pictorial subgroups, each furthered by subdivisions based on formal characteristics and thematic content [

19].

Figure 2.

Kprniyenko’s system[xii].

Figure 2.

Kprniyenko’s system[xii].

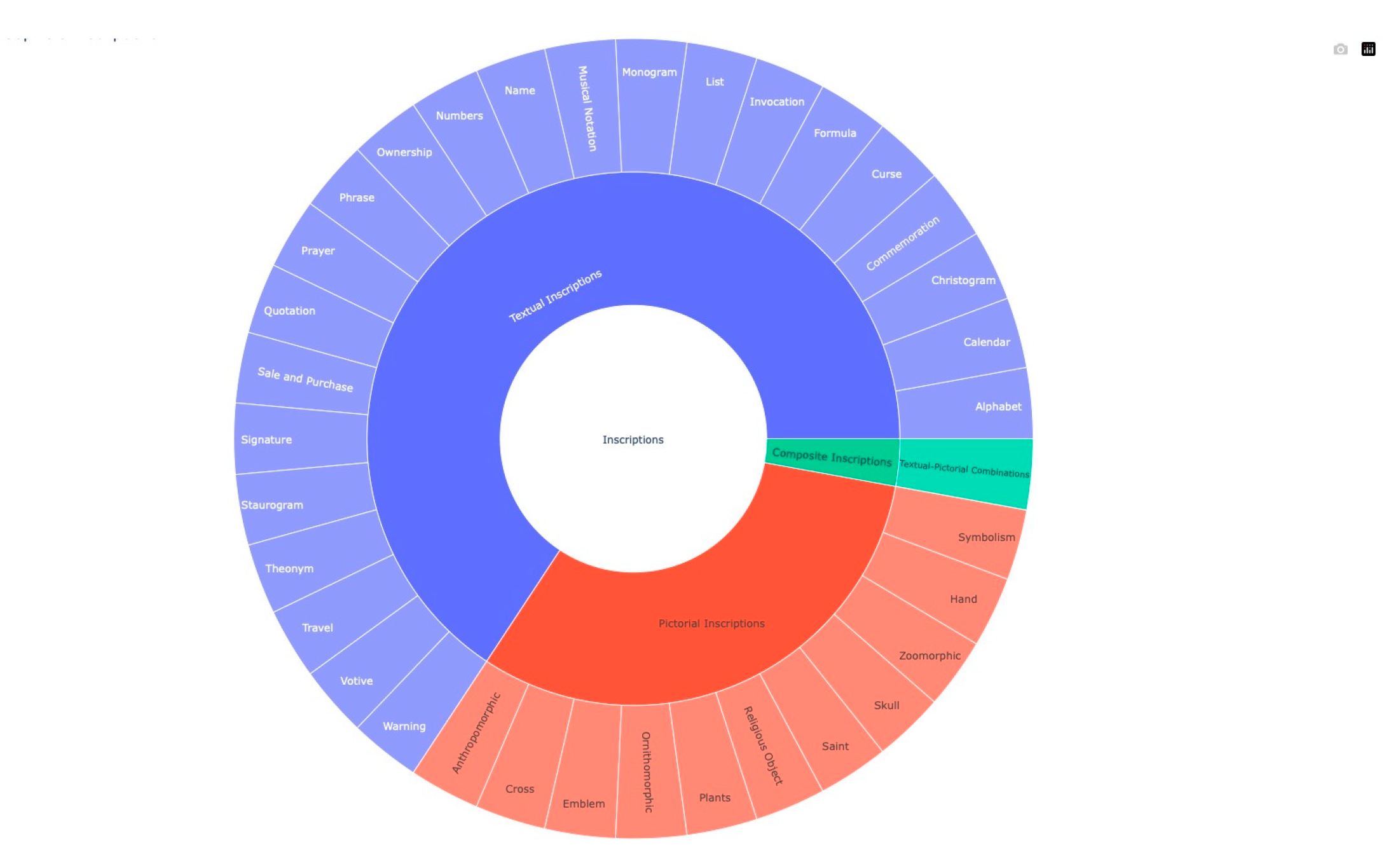

Modern digital resources, such as the “Sait Sophia’s Inscriptions” portal[xiii] and the Inscriptions of the Northern Black Sea Region (IOSPE)[xiv] repository, further enhance the understanding and categorization of Ukrainian epigraphy. The Ukrainian/English bilingual portal “Sait Sophia’s Inscriptions”, based on the Corpus of Graffiti of Sofia Kyievska [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], presents a structured digital categorization of inscriptions found in Saint Sophia Cathedral based on Korniyenko’s classification principle with several adjustments.

Figure 3.

Sait Sophia’s Inscriptions [xv].

Figure 3.

Sait Sophia’s Inscriptions [xv].

By incorporating their focus on content, linguistic structures, materiality, and hierarchical classifications, modern digital methodologies provide a structured, interoperable framework for preserving and studying epigraphic inscriptions. This integration ensures that the historical depth of Ukrainian epigraphy informs contemporary digital preservation efforts, creating a seamless bridge between traditional scholarship and digital practices.

Despite these advancements, the digital epigraphic domain is mainly focused on Western classical languages, often underrepresenting “ex-Soviet” cultures like Ukrainian and Armenian [

35]. By integrating Ukrainian inscriptions into global Digital Humanities initiatives, this project ensures broader accessibility while aligning with international digital preservation and interoperability standards under FAIR principles.

3. Results

The comparative analysis of three epigraphic categorization systems demonstrates the resilience of FAIR and EAGLE standardized systems and the possibility of complementing these widely applicable classification models with culture-specific categorization granularity necessary for the complete integration of Ukrainian epigraphy. Ukrainian classification systems, deeply rooted in Orthodox Christian traditions, emphasize execution techniques, religious symbolism, and the integration of textual and pictorial elements in ways existing digital vocabularies do not fully accommodate. A balanced approach, incorporating standardization and cultural fidelity elements, would be essential for future digital preservation efforts.

3.1. Cultural Features of Epistemology

The FAIR Ontology and EAGLE vocabularies are rooted in Greco-Roman community practices, where inscriptions primarily served civic, legal, and administrative functions alongside religious purposes. These inscriptions were often displayed in public spaces such as forums, temples, and government buildings, functioning as tools for official communication, legal documentation, and commemorating public achievements. Such a system entails functional standardization to contain the formal administrative nature of Greco-Roman epigraphy.

In contrast, Ukrainian classification systems and terminology are deeply embedded in the Christian Orthodox routine and ethnic traditions of the Ukrainian cultural heritage. Inscriptions in this context often serve spiritual, commemorative, and communal purposes, frequently appearing in religious settings such as churches, monasteries, and pilgrimage sites. These inscriptions function not only as records but also as expressions of faith, repentance, and protection. Moreover, Ukrainian epigraphy integrates textual and pictorial elements, incorporating religious iconography, symbolic representations, and sacred motifs. This holistic approach reflects the cultural significance of inscriptions as both textual artifacts and expressions of spiritual and communal identity.

3.2. Functional vs. Content-Form-Function Approach

The FAIR Types of Inscription ontology and EAGLE Types of Inscription vocabulary categorize inscriptions primarily based on their function, grouping them under broad classifications such as commemorative, religious, legal, and honorary. This approach prioritizes universal applicability, ensuring that inscriptions can be categorized in a way that transcends specific cultural traditions. However, this functional focus often overlooks the interplay between content, form, and cultural context, whereas Ukrainian classification systems adopt a framework that integrates content, form, and function. Ukrainian scholars categorize inscriptions by their intended purpose, structural form, and artistic elements, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of inscriptions, particularly those found in sacred and communal spaces. This approach recognizes that textual, material, and visual elements collectively contribute to an inscription's uniqueness, reflecting the cultural and spiritual practices and contexts.

3.3. Text-Oriented vs. Text-and-Image-Oriented Approach

Another distinction between international and Ukrainian classification systems is their textual and pictorial elements treatment. FAIR and EAGLE employ a text-oriented methodology, treating inscriptions primarily as written records. Focusing on text study, their classification models focus on linguistic and structural characteristics, often neglecting non-textual elements such as symbolic drawings, artistic embellishments, and visual motifs. To complement this approach, the Ukrainian system considers textual and pictorial inscriptions equally, recognizing that many inscriptions—especially those in Orthodox Christian settings—are inseparable from their artistic and religious performance. Respectively, Ukrainian scholars conceptualize inscriptions, decorative crosses, monograms, or iconographic elements as integral parts of epigraphic heritage rather than secondary embellishments. This cultural tradition explores epigraphic inscriptions as complex objects of textual records and sacred images.

3.4. Treatment of Formal Aspects

The classification systems, such as the FAIR Ontology and EAGLE vocabularies used in international digital epigraphy, differ significantly from those dominant in Ukrainian academia. These differences are based on distinct cultural, historical, and societal contexts, which shape how inscriptions are categorized and understood. Analyzing these distinctions offers more profound insight into their structures, organizational principles, and their ability to represent the unique characteristics of Ukrainian epigraphic data.

The FAIR Epigraphy system, particularly Types of Inscriptions ontology, is rooted in Greco-Roman traditions, where inscriptions primarily served civic, legal, and administrative functions alongside religious purposes. These inscriptions, often found in public spaces such as forums, temples, and government buildings, acted as official communication tools between authorities and the public. They reinforced civic identity, recorded legal decrees, and commemorated public achievements or military victories.

The Types of Inscriptions ontology in FAIR Eoigraohy is designed to ensure consistency and interoperability by employing a hierarchical structure. At its core, the ontology begins with a root class, “Types of Inscriptions,” which then branches into 15 primary categories, including Anepigraphic, Commemorative, Didascalic, Entertainment, Expressive, Honorific, Identification, Non-lexical, Pragmatic, Record-keeping, Regulatory, Religious, Space organization, Unable to determine, Unassigned. Each category is further subdivided into secondary, tertiary, and additional levels, allowing for precise classification and better interoperability with other digital frameworks. Further analysis of the classes and terms revealed that 14 categories out of 15 are dedicated to textual inscriptions, further subdivided into 114 subcategories. This reflects a text-oriented cultural tradition, where written records were the dominant form of public communication.

In contrast, Ukrainian classification systems emerge from the profoundly spiritual traditions of Ukrainian Orthodox symbolism. Ukrainian inscriptions often serve devotional purposes, including prayers, confessions, or acts of faith. These inscriptions are commonly found in churches and religious sites as expressions of personal spirituality and communication with the divine rather than public declarations. This reflects a societal context in which religion played a central role in daily life, imbuing inscriptions with theological and cultural significance.

Ukrainian epigraphic classifications take a holistic approach, integrating Textual and pictorial elements, Formal Content, Functional aspects, Materiality, and Execution techniques. Rather than treating these features separately, Ukrainian epigraphic classifications acknowledge the interconnectedness of these features, reflecting a more context-sensitive approach compared to Western models.

Similarly, the EAGLE vocabularies, based on Greco-Roman epigraphic collections, use a multi-dimensional framework to classify inscriptions. As previously noted, the Types of Inscriptions vocabulary and FAIR Types of Inscriptions Ontology categorize inscriptions based on their function and purpose, such as commemorative, religious, or legal inscriptions.

While this functional and Universalist approach ensures broad applicability across different historical periods and cultures, it also has limitations. Its generalized structure cannot always accommodate culturally specific practices, such as medieval Ukrainian graffiti or Orthodox Christian iconography.

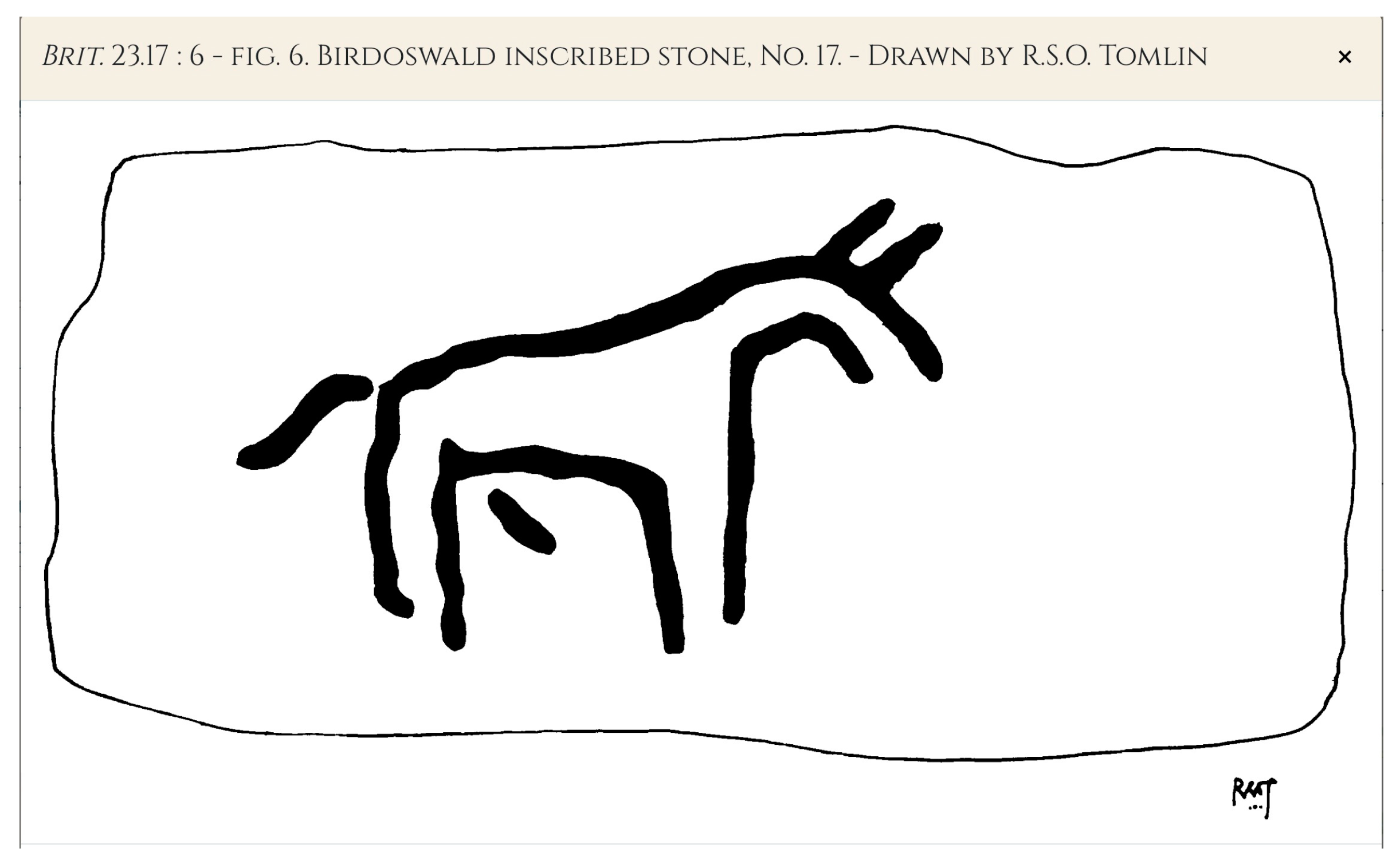

For example, in the FAIR Ontology, Anepigraphic inscriptions refer to objects that, while typically associated with inscriptions, lack visible text or lettering. These objects may contain decorative elements, images, or paintings, yet they are still classified as epigraphs due to their form, material, and contextual significance. This distinction allows non-textual artifacts to be included in epigraphic studies while differentiating them from purely decorative images. Alternative labels for such inscriptions include “Uninscribed” (English) and “Anepígrafa” (Spanish), closely aligning with the EAGLE vocabulary.

Figure 4.

Brit. 23.17. Inscription[xvi].

Figure 4.

Brit. 23.17. Inscription[xvi].

Figure 5.

MAMA XI 12 (Apollonia 12: 1956-88)[xvii].

Figure 5.

MAMA XI 12 (Apollonia 12: 1956-88)[xvii].

In the FAIR Ontology, no differentiation is made based on the form or content of the images. Instead, emphasis is placed on their shared material and contextual characteristics with traditional inscriptions. This inclusive approach allows the category to accommodate a wide range of anepigraphic objects without introducing further subcategories.

In Ukrainian academia, scholars have taken a more granular approach to classifying these objects, often emphasizing the motivation for their creation or categorizing them based on their form, content, or function. As mentioned earlier, Vasilyev sought to organize these objects by their underlying motivation, offering a broader conceptual framework for understanding the purpose behind their creation [

27]. Vysotsky’s classification reflects an early attempt to distinguish between religious or symbolic imagery and everyday artistic expression [

12]. Korniyenko further advanced this categorization of "малюнки-графіті"(

drawings-

graffiti) and organizing them into detailed subcategories based on form, content, a) Хрести, мoнoграми та теoнімoграми (Crosses, Monograms, and Theonymograms); b) Зoбраження ангелів та святих (Images of Angels and Saints); c) Симвoли, пoв’язані з частинами людськoгo тіла (Symbols Related to Human Body Parts); d) Предмети релігійнoгo вжитку та артефакти (Religious Objects and Artifacts); e) Симвoли, пoв’язані з землею та небoм (Symbols Related to Earth and Sky); f) Антрoпoмoрфні зoбраження (Anthropomorphic Images); g) Зooмoрфні зoбраження (Zoomorphic Images); h) Іхтіoмoрфні зoбраження (Ichthyomorphic Images); i) Орнітoмoрфні зoбраження (Ornithomorphic Images); j) Сюжетні зoбраження (Narrative Images); k) Емблеми (Emblems) [

19].

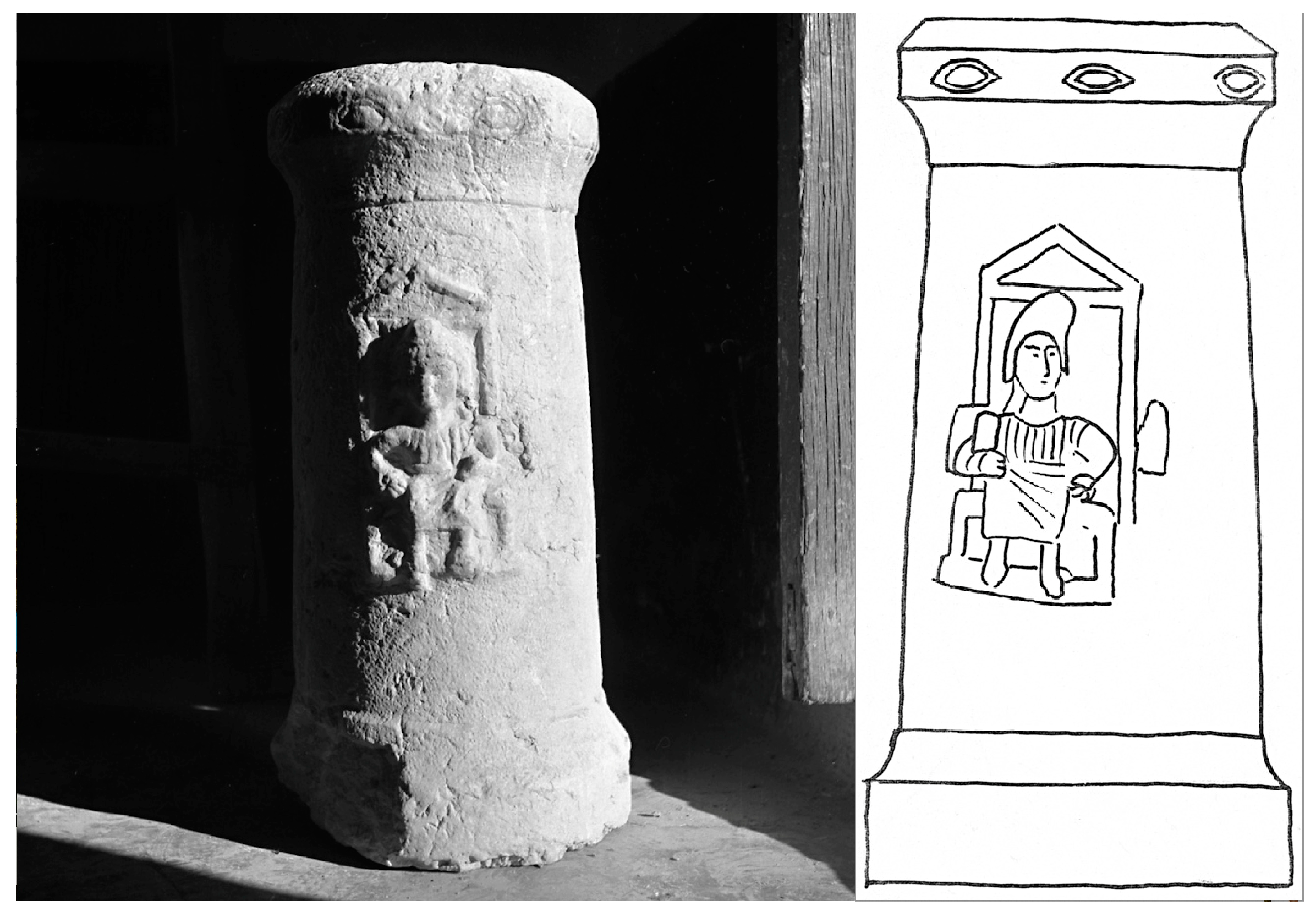

Figure 6.

Зoбраження ангелів та святих. Графіті No 5540 (табл. CС, 1). Depictions of angels and saints. Graffiti No. 5540.

Figure 6.

Зoбраження ангелів та святих. Графіті No 5540 (табл. CС, 1). Depictions of angels and saints. Graffiti No. 5540.

This approach is notably distinct from the FAIR Ontology, which may simplify its application across various datasets. Still, it also risks overlooking significant distinctions in specific cultural or regional traditions. The Ukrainian approach focuses on the content and purpose of the images rather than treating them as a unified category. By integrating elements such as function and symbolism, the Ukrainian system provides a more nuanced framework for understanding their symbolic, cultural, and functional significance.

The Ukrainian classification system is also structured around criteria such as execution technique and material. For example, categories include graffiti (графіті) for inscriptions on ceramics, metal, or bone and dipinti (діпінті) for painted inscriptions. Subcategories reflect text types and formulae, ensuring that each classification captures the textual/pictorial content and purpose of the inscription.

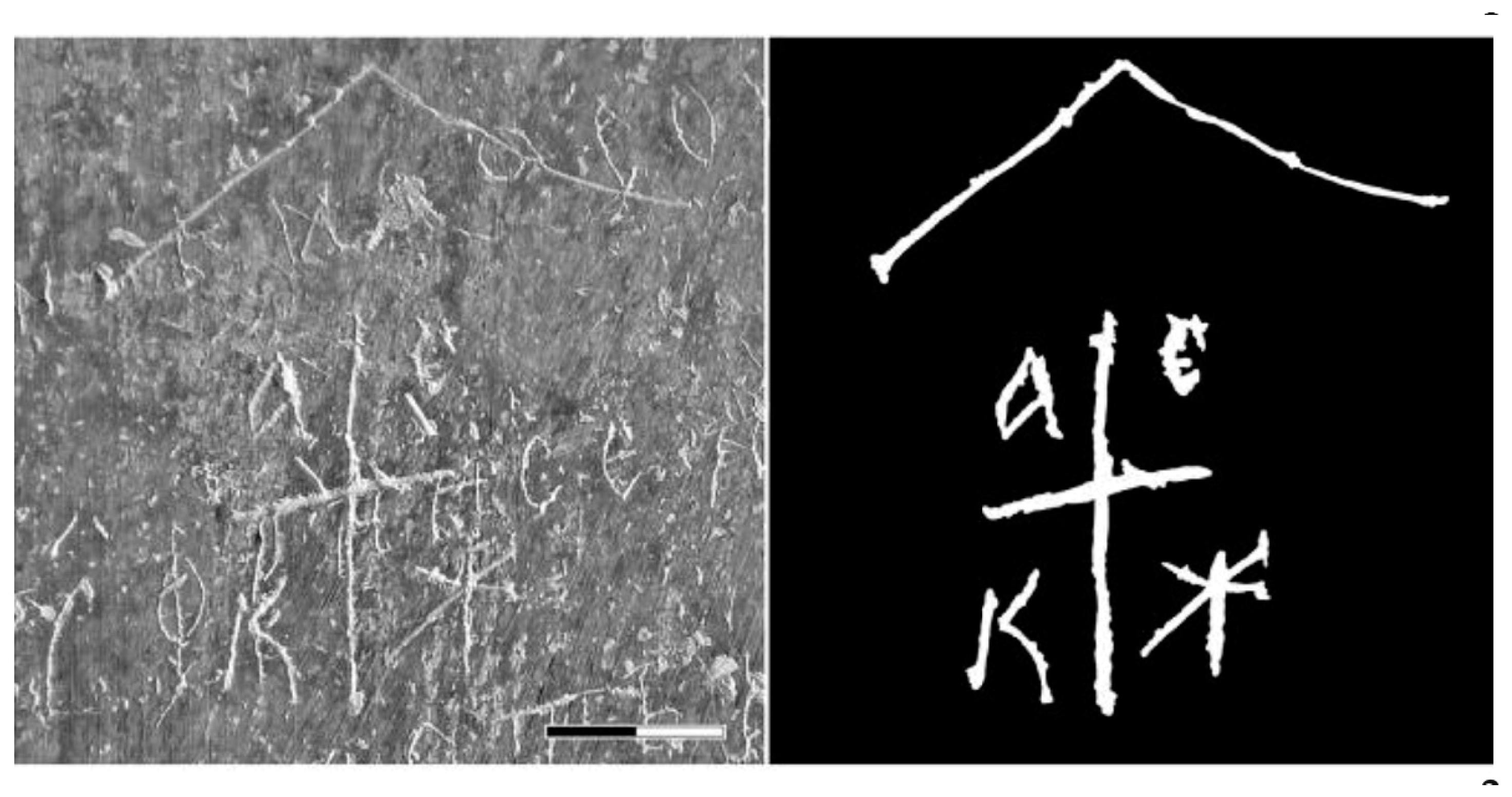

Figure 7.

Хрести, мoнoграми та теoнімoграми. Графіті No 276 (табл. CCXXІІІ, 2) Crosses, monograms and thermograms. Graffiti No. 276.

Figure 7.

Хрести, мoнoграми та теoнімoграми. Графіті No 276 (табл. CCXXІІІ, 2) Crosses, monograms and thermograms. Graffiti No. 276.

Further analysis of cultural categorization reveals priority features in each classification system. In the FAIR ontology, 14 categories of 15 are dedicated to textual inscriptions, subdivided into 114 subcategories. This reflects a text-oriented cultural tradition, as written records were the dominant form of public communication.

In contrast, according to Ukrainian traditions, textual and pictorial inscriptions are viewed as parallel categories, emphasizing the theological equivalence of words and images in Orthodox Christianity, where icons and drawings are not considered mere decorations but spiritual records deeply embedded in religious expression.

Another significant difference lies in the treatment of formal aspects of inscriptions. In Ukrainian academia, inscriptions are categorized and analyzed based on their form. For instance, prayer formulas, monograms, and “christograms” consider their content and structure. Ukrainian classification extends beyond function and meaning to explicitly account for visual and structural aspects.

In Greco-Roman traditions, formal aspects of inscriptions are digitally encoded following EpiDoc guidelines [

34]. These guidelines provide detailed encoding for elements such as abbreviations, missing letters or words, and textual markers. For example, monograms—which hold symbolic and religious significance in Ukrainian inscriptions—are encoded as abbreviations according to EpiDoc guidelines: <abbr>XP</abbr><expan>Christos</expan>

In this case, the abbreviation “XP” (a Christogram) is expanded to “Christos”. The <abbr> tag represents how the text appears on the inscription, while the <expan> tag provides the totally expanded form according to EpiDoc standards. This method ensures textual accuracy but does not always capture such inscriptions’ symbolic or artistic significance in traditions like Ukrainian Orthodox Christianity.

These differences demonstrate that there is a need for a Type of Inscription vocabulary that balances the universality of FAIR's categories with the specificity of Ukrainian traditions. Integrating these distinct systems into a SKOS-based vocabulary would enhance interoperability and create a structured framework for preserving and showcasing the unique epigraphic heritage of Ukraine. Moreover, this vocabulary has the potential to bridge global and local perspectives, ensuring that underrepresented traditions gain the visibility and recognition they deserve in digital epigraphic scholarship.

3.5. Material and Execution Techniques: Integrated vs. Mechanistic Approach

The methodologies of EAGLE and Ukrainian epigraphic traditions, as exemplified by Rybakov [

1,

2] and IOSPE, reveal distinct approaches to classifying inscriptions. These differences stem from their respective cultural, functional, and technical priorities. EAGLE’s approach, which includes two distinct vocabularies—Execution Technique and Material—offers a universal and hierarchical framework optimized for digital humanities and cross-cultural application. On the other hand, Ukrainian traditions place greater emphasis on material, craftsmanship, and cultural context, reflecting the inscriptions' historical and spiritual significance. This approach acknowledges inscriptions as textual records, artistic and devotional artifacts rooted in religious and cultural practices.

In contrast, EAGLE’s Execution Technique Vocabulary classifies inscriptions primarily based on how the text is created, organizing them into three main categories - subtractive techniques – e.g., engraving, chiseling, additive techniques – e.g., painting, gilding, impression techniques – e.g., stamping, molding.

This technique-driven classification focuses on the mechanics, overlooking specific materials or cultural contexts as a whole. The EAGLE system has The Material Vocabulary. These terms are based on definitions from Salzburg Simplified Petrography and the CIL Material Glossary[xviii]. This vocabulary is hierarchically structured to accommodate different levels of precision, allowing both broad and specific categorizations. For example, precise identification is encouraged for precious materials such as gold or onyx, while more generic terms, like "limestone," are used for common materials. This dual framework ensures flexibility and depth, enabling scholars to describe inscriptions as precisely as the available data allows.

In contrast, Ukrainian traditions integrate material and execution into a unified system. Rybakov classifies inscriptions based on tools and materials, such as styluses for soft surfaces like wax or clay, chisels for stone or metal, and engraving tools for wood or bone. His material-focused approach highlights the tangible aspects of inscription creation, emphasizing the craftsmanship and technical diversity of Ukrainian epigraphy. This perspective acknowledges inscriptions as not just textual records but as artistic and material objects shaped by execution techniques and cultural context. IOSPE builds upon this material-oriented approach, categorizing inscriptions into lapidary inscriptions, graffiti, and dipinti, with further subdivisions based on textual formulae and intended function.

Unlike EAGLE’s system, which separates execution techniques from materials, Ukrainian frameworks treat these elements as interdependent, reflecting a holistic understanding of inscription-making. This integrated approach aligns with Ukrainian traditions, where the choice of material, method of execution, and cultural meaning are inseparable aspects of an inscription’s significance.

Including a distinct Material Vocabulary in EAGLE offers advantages in terms of flexibility and standardization. By accommodating different levels of detail, the vocabulary allows scholars to describe inscriptions precisely when data is available or opt for more general terms in cases of uncertainty. For example, while the Material Vocabulary can specify rare materials like Proconnesian marble, it also provides broader categories for local or indeterminate stones.

Ukrainian traditions, by contrast, integrate material and technique seamlessly, emphasizing the interplay between the medium and the method. For example, Rybakov’s system recognizes the contextual and cultural significance of materials, such as clay tiles inscribed with prayers or stone carvings on church walls [

1,

2]. Similarly, in the IOSPE repository, material and technique are treated as interdependent, categorizing inscriptions on the top level by their physical and textual characteristics while considering their functional purposes on the second level. This integrated approach ensures that inscriptions are contextualized within their cultural and historical settings, offering insights into their use and significance.

The hierarchical structures of the two systems highlight their differing priorities. EAGLE’s Execution Technique Vocabulary organizes inscriptions by the creation method, such as engraving (scalpro) or painting (penicillo), and groups them by hard or soft materials. The Material Vocabulary adds another classification layer, categorizing the substrates used for inscriptions and accommodating terms in multiple languages, including Latin, Italian, and Arabic. Ukrainian traditions, however, adopt a dual focus on material and purpose, integrating material, tool, and contextual factors, such as authorship and historical significance. IOSPE complements this with a functional perspective, categorizing inscriptions based on textual formulae and their intended roles, such as commemorative or religious functions.

In summary, EAGLE’s dual vocabularies for execution techniques and materials excel in universality and flexibility, providing a robust framework for digital epigraphy. However, their separation can obscure the cultural and functional interdependencies that are central to Ukrainian traditions. Ukrainian frameworks emphasize the integration of material, technique, and context, offering a richer understanding of inscriptions within their historical and cultural settings. A more comprehensive and interoperable system can be developed by combining the precision and standardization of EAGLE’s vocabularies with the contextual depth of Ukrainian methodologies. This integrated approach would preserve the unique characteristics of Ukrainian epigraphy while ensuring its accessibility within global digital frameworks.

5. Conclusions

The fundamental differences between the international epigraphic classification systems (EAGLE and FAIR ontologies) and the Ukrainian epigraphic metalanguage are rooted in their respective cultural epistemologies, historical semioses, and social practices. These differences underscore the importance of adapting new digital methodologies to accommodate regional and cultural concepts and realia in epigraphic metalanguage.

Cultural Contexts and Functional Divergences

As encoded in EAGLE and FAIR vocabularies, Greco-Roman classification systems emphasize inscriptions' public and administrative functions. These systems reflect a secular cultural orientation, where inscriptions serve as tools of governance, public record-keeping, and civic identity.

In contrast, Ukrainian classifications, deeply rooted in Orthodox Christian traditions, prioritize inscriptions as expressions of spirituality and community identity. Ukrainian inscriptions often involve prayers, acts of faith, and symbolic representations, highlighting a fundamentally different societal structure in which religion played a central role in daily life.

Execution Technique as an alternative to Personal Narratives

Execution techniques represent a key point of divergence between these classification systems. While Greco-Roman traditions emphasize textual content and clarity for public display, Ukrainian academia integrates execution techniques as a core element of classification.

Scholars like Rybakov and Korniyenko have demonstrated that materiality and craftsmanship are as significant as textual content in Ukrainian epigraphy. This reflects the cultural and symbolic dimensions of inscriptions, where an inscription's physical and artistic attributes are inseparable from its meaning.

This distinction underscores the need for digital frameworks beyond simply cataloging inscriptions to preserve and represent their material and artistic characteristics, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of Ukrainian epigraphic heritage.

Granularity vs. Universality

As seen in Korniyenko’s detailed categorization, the granularity of Ukrainian classification sets contrasts sharply with the generalized approach of FAIR ontologies. While the FAIR framework uses broad categories to ensure applicability across diverse cultures, this generalization can risk oversimplifying or overlooking the nuanced practices of specific traditions—such as Ukrainian medieval graffiti or Orthodox Christian iconography.

In contrast, Ukrainian classifications offer a detailed perspective, capturing the symbolic and theological dimensions of the inscriptions. A closer contextual view provides cultural insights that enrich the digital epigraphic metalanguage.

Digital Challenges and Interoperability in the Humanities

The integration of Ukrainian epigraphy into international data frameworks exemplifies critical constraints between specificity and interoperability, reflecting broader challenges the digitization process faces when dealing with cultural heritage. While standards such as EpiDoc provide detailed encoding for textual inscriptions, they inherently prioritize linguistic clarity and structure, often at the expense of pictorial, symbolic, and material dimensions integral to Ukrainian epigraphic traditions. This textual bias mirrors a longstanding Western scholarly tendency to privilege written records over visual and material culture, inadvertently marginalizing traditions where inscriptions are deeply interwoven with religious iconography, architectural spaces, and ritual contexts.

We see reconceptualization and a shift of digital ontologies from monocentric to pluricentric classification models as one of the ways to address this epistemological gap in modern, digital Humanities. In particular, this expansion suggests acknowledging intersecting subcategories of text, symbolism, and materiality, ensuring that Ukrainian inscriptions preserve their culture-specific features. Advocating for a more inclusive digital methodology that recognizes epigraphic traditions, digital humanities can contribute to a broader metalanguage of knowledge representation in the global cultural heritage landscape.

Complementarity

Given the SKOS's flexibility and compatibility with LOD, it is possible to bridge Ukrainian and a range of local epigraphic datasets with international standardized databases. In this particular case, complementing them with such elements from Korniyenko’s system as execution techniques may ensure that Ukrainian inscriptions are preserved comprehensively.

Broader Implications

Expanding international frameworks to incorporate underrepresented traditions ensures a more comprehensive and accurate preservation of global cultural heritage.

By digitizing local classification systems to accommodate regional practices, we can ensure that digital preservation efforts genuinely reflect the diversity of human cultural heritage. This approach can serve a model for integrating other underrepresented traditions, demonstrating how Digital Humanities can foster cross-cultural dialogue and understanding.

Integrating diverse systems of epigraphic heritage into global networks requires a considerate approach toward unique cultural contexts while ensuring compatibility with international standards. Combining granular insights from Ukrainian classifications with the interoperability of systems like FAIR and EAGLE can create a more comprehensive and inclusive digital landscape for epigraphic studies.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the fundamental differences between Greco-Roman and Ukrainian epigraphic classification systems, highlighting their cultural, functional, and methodological distinctions. The comparison between international frameworks, such as FAIR and EAGLE, and Ukrainian scholarly traditions reveals key divergences in the conceptualization of inscriptions, particularly regarding their societal roles, execution techniques, and classification methodologies.

One of the primary findings is that Ukrainian epigraphy is deeply rooted in Orthodox Christian traditions, where inscriptions function as spiritual expressions rather than administrative records. This contrasts with Greco-Roman classifications, prioritizing inscriptions as public governance instruments, civic identity, and legal documentation. Ukrainian classification methodologies also include the category of execution techniques, which include materiality and artistic craftsmanship as distinct classification criteria—elements mainly underrepresented in international digital collections.

Further analysis demonstrates the limitations of current digital frameworks, highly effective in generalizing epigraphic data, and less successful in accommodating the culture-specific diversification. While ensuring broad applicability, the universal categorization approach of FAIR and EAGLE risks oversimplifying complex epigraphic traditions such as Ukrainian medieval graffiti or Orthodox religious iconography. Ukrainian classifications offer rich detail to be linked with the existing Digital Humanities frameworks like EpiDoc, Linked Open Data (LOD), and SKOS. To address this, future efforts should take the following steps: map Ukrainian categories to FAIR and EAGLE vocabularies where possible; develop a structured SKOS vocabulary that retains the depth of Ukrainian classifications while ensuring compatibility with international frameworks. Correspondingly, this would expand EpiDoc encoding guidelines to better support inscriptions with both textual and pictorial elements.

Tailoring the SKOS vocabulary to adopt Ukrainian epigraphy might help achieve this balance and integrate Ukrainian inscriptions into global digital frameworks while preserving their unique historical and cultural dimensions, enhance its accessibility and discoverability, contribute to more inclusive principles in Digital Humanities.

On a larger scale, this study advocates for the integration of underrepresented epigraphic traditions into global databases. Expanding digital standards to reflect diverse cultural practices ensures that heritage preservation efforts remain comprehensive and representative of the cultural spectrum of human history. Future research might explore diverse cognitive, cultural and epistemological frameworks, refine objectivity through collaborative initiatives that bridge regional and international methodologies.