1. Introduction

The field of epigraphy has been shaped by long-standing editing practices and major publication projects. The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) [

1] started in 1853 under Theodor Mommsen, and the Inscriptiones Graecae (IG) [

2], which continues the earlier Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, created comprehensive collections of Greek and Latin inscriptions and developed standards that still influence scholarly editing [

3]

i. These collections focused on accurately reproducing inscriptional texts and on editorial reconstruction, using sigla to mark restorations, missing parts, and other textual features. The Leiden Conventions, first established in the early 20th century and revised in 1931 and 1982, summarized these practices into widely used international guidelines. Similar efforts exist in other traditions, including the Répertoire d’épigraphie arabe for Arabic inscriptions and large-scale editions of cuneiform texts from Mesopotamia [

4,

5]. More recently, digital projects like EAGLE

ii in Europe and OCIANA

iii for Ancient North Arabian show how traditional collections can be integrated into interoperable digital infrastructures [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Within this global context, Armenian epigraphy shows both continuity with worldwide practices and the development of unique methods. The Armenian alphabet, created in the early fifth century, laid the groundwork for one of the earliest Christian epigraphic traditions. They are scattered worldwide—from India and Iran to Turkey, Europe, and the Americas—testifying to the long history of Armenian communities across diverse regions. Over the centuries, varying degrees of care have been devoted to preserving this heritage. Surviving inscriptions are numerous and spread across various regions, carved into the walls of churches and monasteries, engraved on khachkars (cross-stones), and placed on bridges, fortifications, and tombstones. These texts record a wide range of information: dedications, commemorations, donor lists, epitaphs, and documentation of construction projects. They are a vital part of Armenian cultural and religious history. Today, the challenge is not only to safeguard but also to digitize these invaluable assets. Digital preservation is essential for Armenian national history and identity, and for the study of Christianity and for broader regional and comparative historical research [

10,

11,

12].

The scholarly investigation of Armenian inscriptions began in the nineteenth century, when early antiquarians and travelers such as M. Brosset [

13], Gh. Alishan [

14], M. Barkhudaryants, Y. Lalayan, and others collected, copied, and occasionally published inscriptions they encountered. Their methods were often inconsistent, limited to hand-drawn facsimiles or textual transcriptions without a systematic framework [

15].

A significant development took place with the launch of the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV, Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

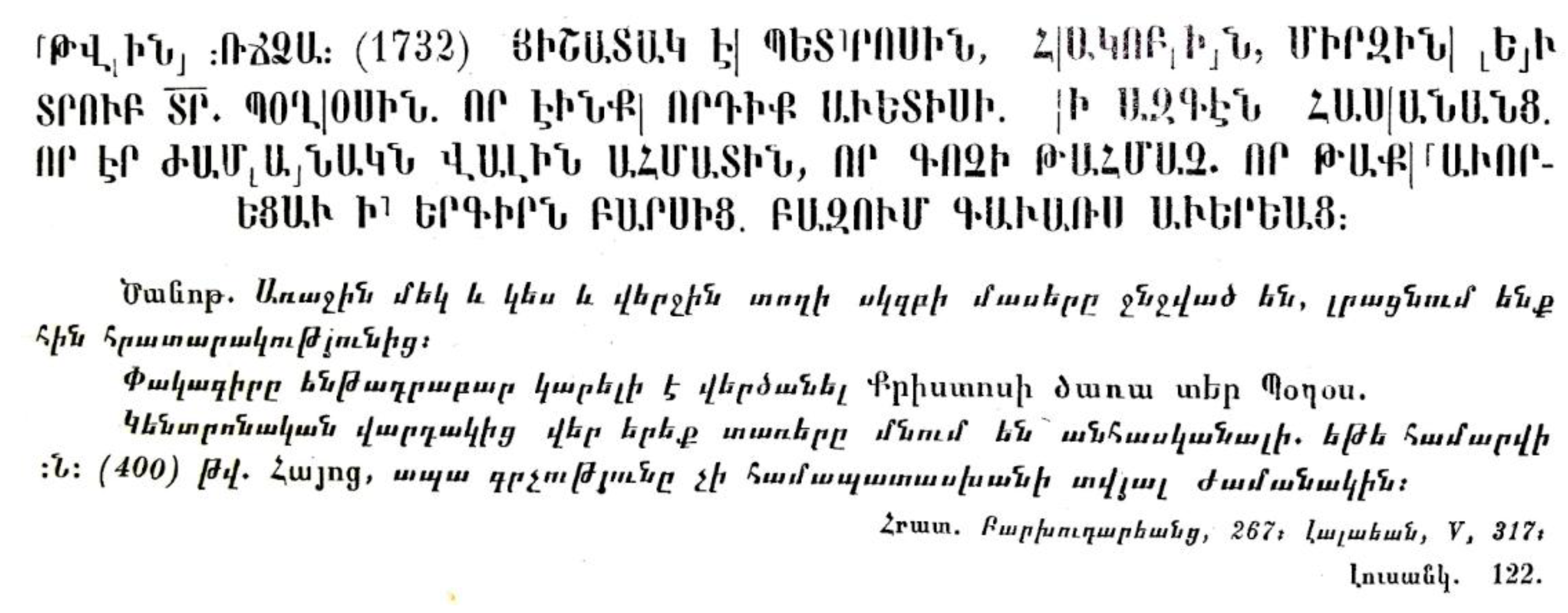

25] initiated in the 1960s by the Armenian Academy of Sciences. The DHV created a systematic framework for the transcription and presentation of Armenian inscriptions. The DHV introduced, for the first time, a standardized scholarly apparatus for transcribing inscriptions, distinguishing between diplomatic transcription, a faithful reproduction of the state of the stone, and interpretative transcription, an editorial reconstruction with expanded abbreviations and restored text. It is noteworthy that the diplomatic transcription was considered equivalent to the drawing. Already in the earliest volumes of the DHV, in the section where the editorial signs are explained, each sign is described as it appears in the interpretative transcription (վերածնության մեջ) or in the drawing (գծագրության), the latter corresponding to the diplomatic transcription.

“ՎԵՐԾԱՆՈՒԹՅԱՆ ՊԱՅՄԱՆԱԿԱՆ ՆՇԱՆՆԵՐ

- հորիզոնական գծով նշված են բնագրի մեջ համապատասխան թվով ջարդված գրերը,

... Կետերով նշված են բնագրի մեջ ջարդված գրերը՝ անկախ թվաքանակից,

⎡ ⎤ Փակագծով նշված են ջարդված գրերի վերականգնումները ,

⎣ ⎦ Փակագծով նշված են բնագրի մեջ գրչի բաց թողած, սղած կամ առանց պատվի (սղման նշան) սղումների վերականգնումները ,

[ ] նշված են բնագրում եղած ավելորդ գրերը,

/ Թեք գծով նշված են բնագրի տողերի սահմանները ։”

iv [

17] (p.1).

To support this dual presentation, the DHV employed a system of editorial signs. These allowed scholars to mark damaged or missing letters, restorations, abbreviations, and honorifics consistently. Over time, however, subsequent Armenian publications began to adapt these conventions. Some introduced typographic simplifications, while others reinterpreted or replaced certain signs. As a result, Armenian epigraphy today does not follow a single uniform practice but exhibits a range of overlapping variants.

This apparatus established a consistent reference point for Armenian scholarship. It compares to the role of the CIL or IG in their respective traditions because it provides both a large corpus and a standardized set of editorial standards. At the same time, the DHV conventions reflect the specific needs of Armenian epigraphy, such as handling highly abbreviated formulas or the presence of distinctive ligatures in carved letters.

In the decades that followed, Armenian editorial practice became marked by both innovation and instability [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Many later publications simplified or reinterpreted DHV conventions, often replacing specialized symbols with typographic substitutes. While these changes improved accessibility for a broader readership, they also diminished palaeographic precision and introduced inconsistency across editions. At the same time, publications produced under the leadership of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Armenian Academy of Sciences—the institution responsible for the DHV—have continued to follow the conventional sign system established in the corpus [

30]. This dual trajectory highlights the fragmentation of Armenian editorial practice, which raises challenges for integrating Armenian epigraphy into broader international systems and underscores the need for systematic comparison with established frameworks such as the Leiden Conventions [

31] and EpiDoc TEI [

32]. Addressing this issue requires careful documentation rather than eliminating variation.

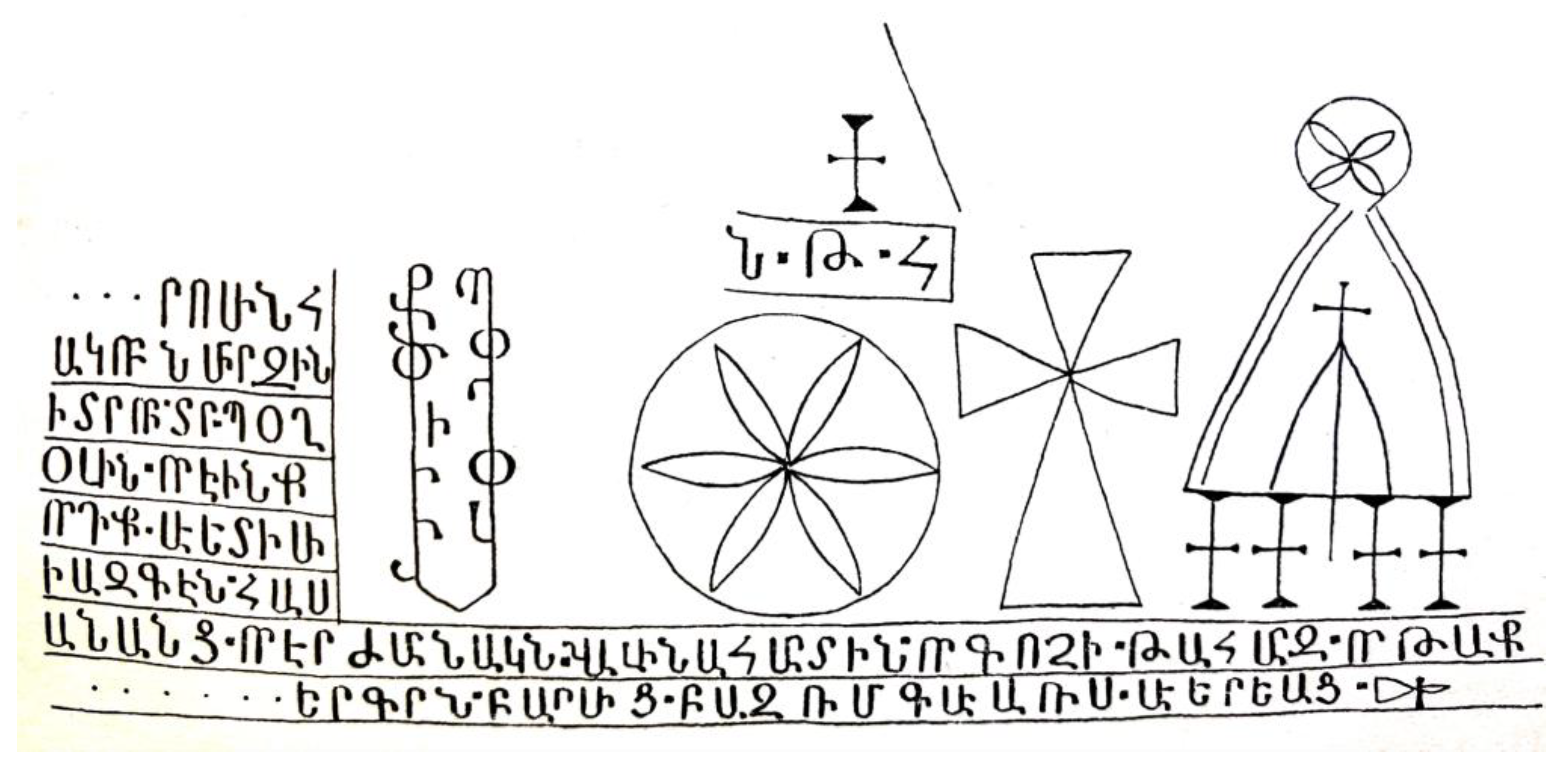

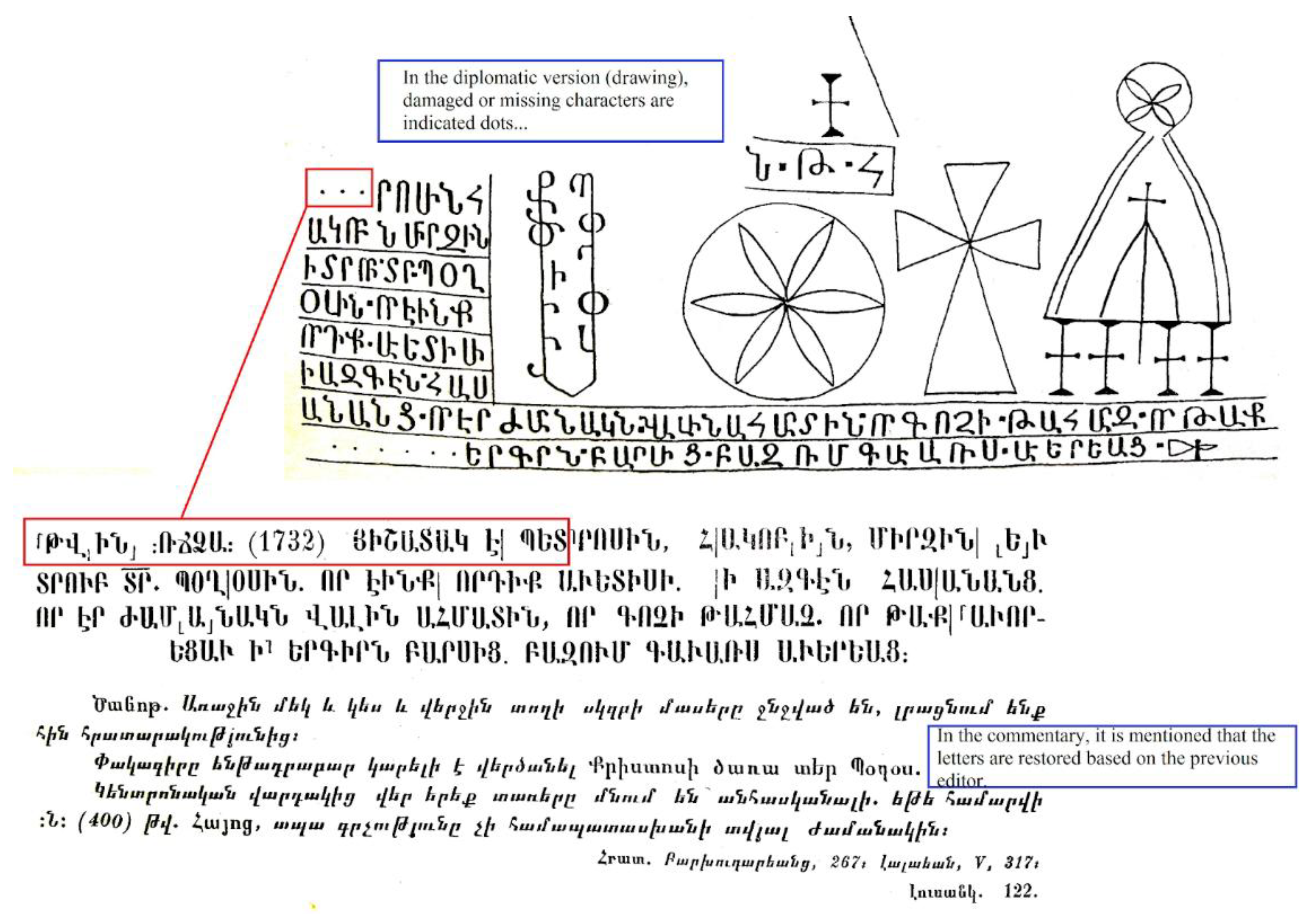

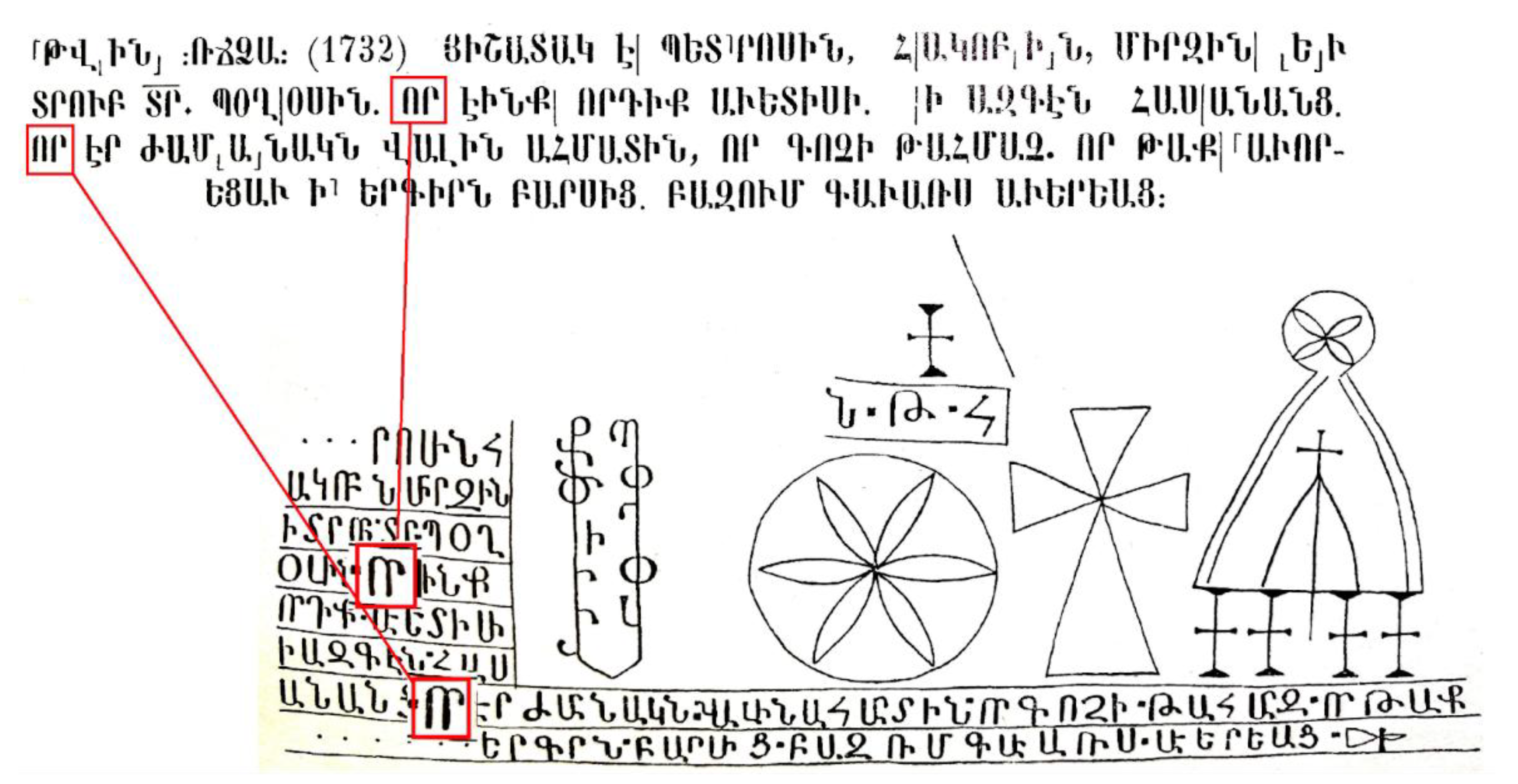

A representative example illustrating the DHV editorial method is an inscription from volume 5, carved on the stone of a lintel embedded in the southern wall of the Church of St Minas in the village of Ablah, located in the historical provinces of Artsakh–Utikʿ (later the Khanlar region). The inscription is commemorative in nature and, as noted by one of its publishers, Sedrak Barkhudaryan, its subtext also contains a reference to the renovation of the church, which was carried out through the patronage of the individuals mentioned in the text. In addition to the main inscription, the stone also preserves, almost in its center, a monogram, several cross reliefs, a rosette, and architectural motifs resembling a church with a dome. Barkhudaryan provisionally read the monogram as “Servant of Christ, Ter Poghos,” a reading we also consider correct. However, the capital letters Ն.Թ.Հ. visible above the rosette were considered illegible; Barkhudaryan even attempted to interpret them as a date (“Ն. – year 400 of the Armenian era”). Yet, taking into account that in the photograph of the inscription published in DHV vol. 5 the stone is clearly broken before the letter N (

Figure 1), we propose restoring there the initial letter Յ and reading the sequence as the frequently attested Christological formula in Armenian inscriptions: «⎡Յ⎤⎣իսուս⎦ Ն⎣ազովրեցի⎦ Թ⎣ագաւոր⎦ Հ⎣րէից⎦» (“Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”).

As for the restoration of the other damaged parts of the inscription, these follow the copy made by Bishop Makar Barkhutareants at the end of the nineteenth century, when the inscription was still intact [

33].

Figure 1.

Memorial inscription, Ablah village (previously Khanlar region), St. Minas Church, 1738 AD (DHV/5, Inscription 828).

Figure 1.

Memorial inscription, Ablah village (previously Khanlar region), St. Minas Church, 1738 AD (DHV/5, Inscription 828).

Figure 2.

The drawing of the Inscription 828.

Figure 2.

The drawing of the Inscription 828.

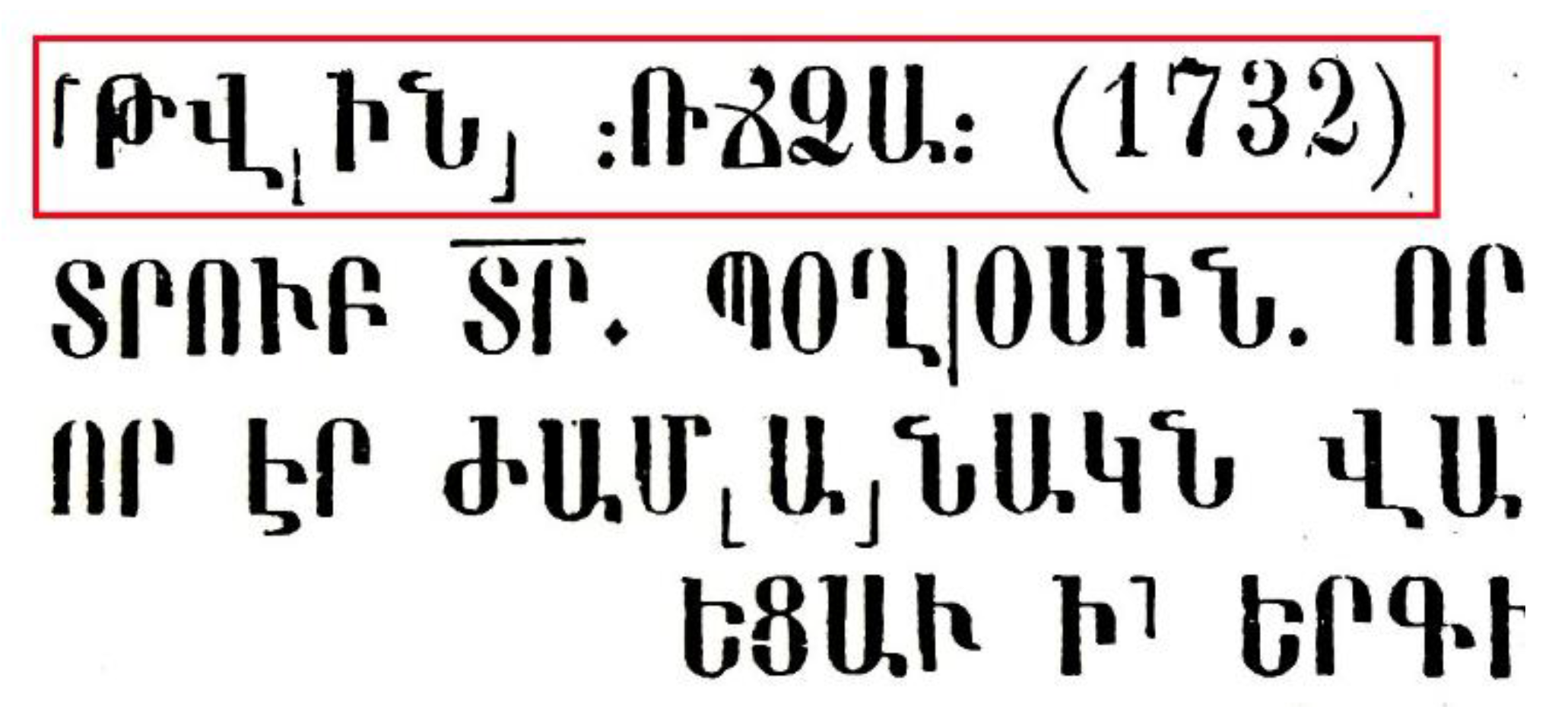

Figure 3.

The decipherment and comment of Inscription 828.

Figure 3.

The decipherment and comment of Inscription 828.

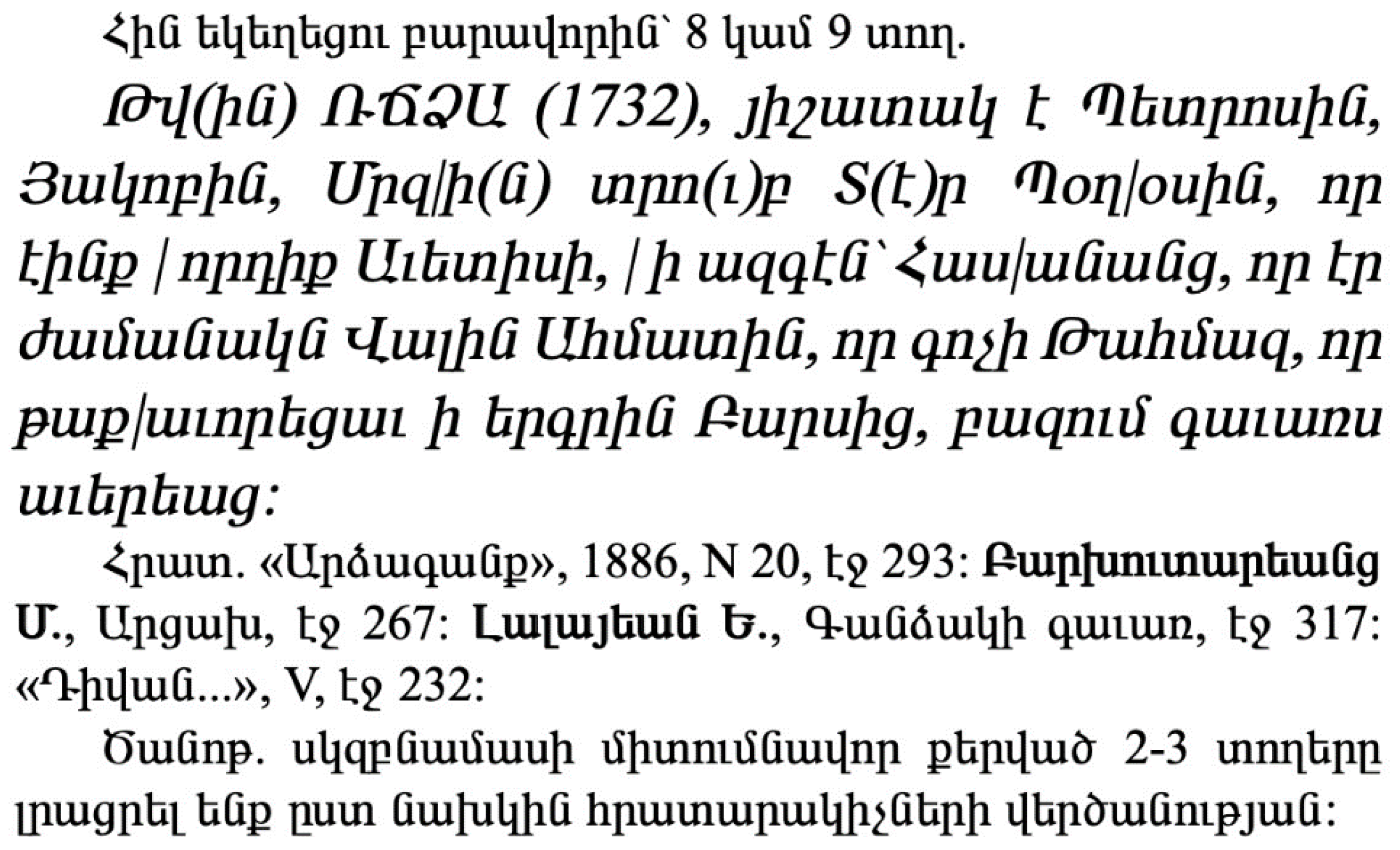

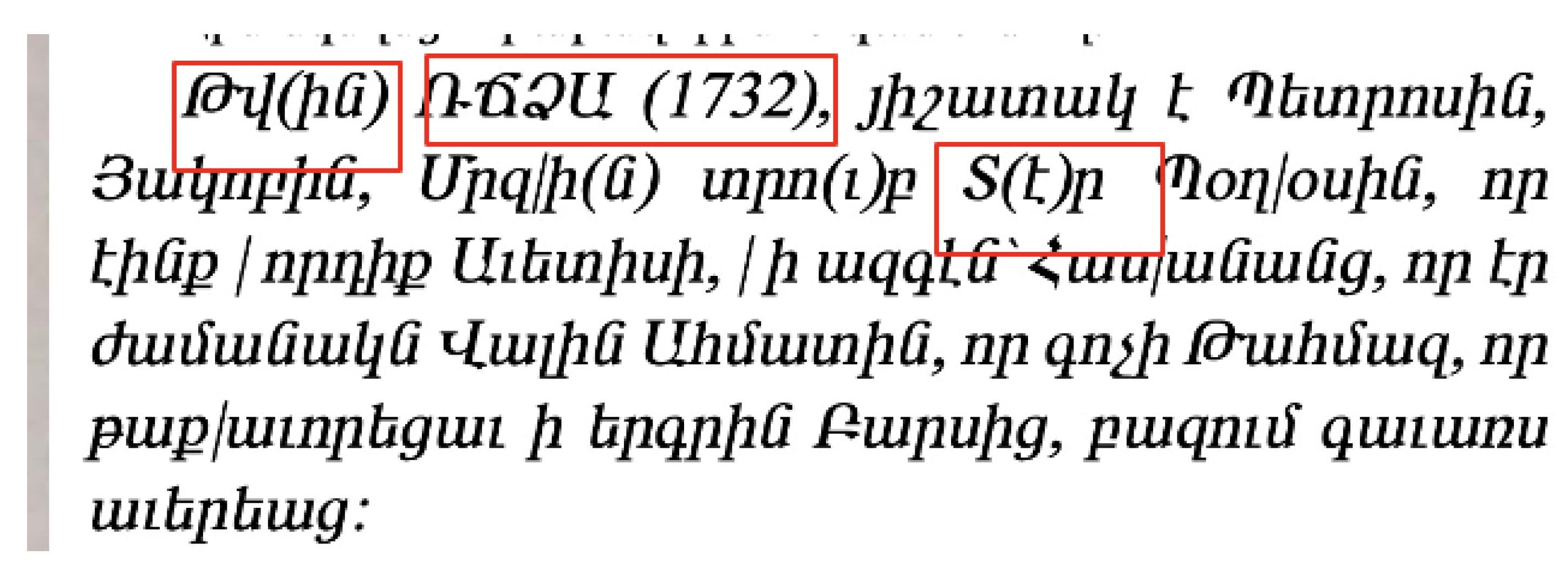

Figure 4.

Later edition of the same inscription [

26].

Figure 4.

Later edition of the same inscription [

26].

2. Methodology

Armenian epigraphy has never been systematically compared with the Leiden and EpiDoc systems. Therefore, the purpose of this study is twofold. First, it demonstrates practical pathways for aligning Armenian editorial conventions—developed most systematically in the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV)—with international frameworks such as the Leiden Conventions and EpiDoc TEI, without erasing local practice. Second, it shows that the principal contribution of Armenian material lies not in providing greater granularity of sigla (Leiden is more detailed), but in transparent documentation and consistent cross-walking of Armenian conventions to international categories, ensuring that editions remain both comparable and machine-actionable.

Methodologically, the study advocates corpus-level editorial policies, explicit mapping tables, and dual-track encoding strategies: a granular Leiden/EpiDoc mapping where evidence permits, alongside a simplified encoding faithful to Armenian usage. This approach supports large-scale digitization and promotes the interoperability of the globally dispersed Armenian inscriptional record, enabling its use in comparative epigraphic research across traditions.

By situating Armenian conventions within the Leiden–EpiDoc ecosystem, this research addresses a long-standing gap: the underrepresentation of Armenian Christian epigraphy in modern comparative inscriptional studies. The alignment highlights the unique methodological heritage of Armenian scholarship and ensures its interoperability in digital encoding and scholarly exchange. also. In this way, Armenian epigraphy moves from the heritage tradition kept in the margins of global research into an integrated framework where its specific practices contribute to international standards.

2.1. Corpus

This study explores the internal variation of editorial signs in Armenian epigraphic publications and evaluates their compatibility with international standards. The main assumption is that Armenian editorial practices form a continuum rather than isolated toolsets. Historically, this continuum begins with the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV). The DHV created a systematic distinction between diplomatic transcription, which reproduces inscriptions exactly as carved, and interpretative transcription, which restores missing or abbreviated parts. Later publications, especially from the 1990s onward, maintained these core principles while adding reinterpretations, simplifications, and typographic adjustments [

26,

29,

34]. This layered history makes Armenian epigraphy a valuable case for studying the development of local editorial conventions and their potential alignment with frameworks such as the Leiden Conventions and EpiDoc TEI [

6,

7,

32].

2.2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical foundation of this analysis rests on semiotic ontology, which treats inscriptional signs as triadic entities composed of material representation, conventional value, and interpretant. Following C. S. Peirce’s model [

35], a sign is not merely a visual mark but a dynamic relation between the representamen (the carved form), the object (its linguistic value), and the interpretant (the meaning attributed by editor or reader). Applied to Armenian editorial practice, this model highlights that symbols such as brackets, dashes, or ligature marks embody interpretive acts as much as they denote textual features. As Umberto Eco argued in his notion of the encyclopedia [

36][, signs operate within culturally embedded systems of knowledge.

Building on this semiotic basis, the study draws from editorial hermeneutics, particularly as formulated by Tanselle [

37]. Editing is conceived not as a neutral transfer but as an interpretive act that mediates between the witness (the inscription), the editor, and the imagined text reconstructed in transcription.

The study also employs the framework of diachronic graphemics, which treats writing systems as layered structures subject to systematic change. Graphemics distinguishes between graphetics (the physical form of signs), graphematics (the functional level of graphemes), and orthography (the regulated system) [

38,

39]. This model helps separate typographic substitutions from functional reassignments. By tracing these movements across visual, functional, and orthographic layers, graphemics provides a means to understand how Armenian editorial signs evolve and accumulate meaning over time.

Taken together, these perspectives—semiotic ontology, editorial hermeneutics, and diachronic graphemics—frame editorial signs as semiotic artifacts whose meanings are historically and culturally situated. This integrated approach also helps to distinguish graphic variation from conceptual change, to interpret editorial choices as hermeneutic acts, and to model inscriptional practices as layered writing systems. In turn, this enables a systematic mapping of Armenian traditions onto Leiden and EpiDoc international frameworks, where clarity, interoperability, and cultural specificity must be carefully balanced. The Leiden system provides a set of editorial symbols to show how ancient inscriptions are transcribed from damaged or incomplete originals. Created by philologists for print editions, it uses simple punctuation to tell readers what is visible, missing, or uncertain on the stone. The EpiDoc standard builds upon the Leiden conventions, but is a digital framework for encoding inscriptions so that computers can process, search, and display them online. It uses the .xml machine-readable format (tags).

2.3. Procedure

The procedure integrates formal-comparative and semiotic analysis. Each editorial sign was:

documented as it appears in the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV),

correlated with attestations in later Armenian publications, and

examined for semiotic status, including its use, interpretive value, and role within the editorial system.

This workflow produced a principled typology:

Graphic variation: typographic substitution without change in meaning (e.g., ⎡ …⎤ → [ ]).

Conceptual divergence: reallocation of editorial function (e.g., [ ] marking redundant letters in DHV but restorations in later editions).

Systemic innovation: introduction or repurposing of signs that reorganize the local editorial ecology.

Special emphasis was placed on three categories where divergences are most pronounced: (a) damaged letters (known vs. unknown quantity), (b) restorations versus redundancies, and (c) ligatures and honorifics. These were analysed both semiotically and functionally to determine their interoperability within digital corpora.

At the final stage, Armenian conventions were mapped against international epigraphic standards. The Leiden Conventions served as the benchmark for print epigraphy, while EpiDoc TEI provided the XML schema for digital encoding. Armenian signs were assigned to EpiDoc categories such as <gap> (missing text), <supplied> (restorations), <unclear> (uncertain readings), <abbr> (abbreviations), and <surplus> (redundant letters). This mapping highlights both areas of alignment and unique features requiring explicit documentation.

By combining comparative, semiotic-functional, and digital methods, the study accounts for the historical diversity of Armenian editorial conventions and ensures their compatibility within the broader semiotic paradigm of digital epigraphy.

3. Results

The comparative analysis confirms that Armenian epigraphic publications share a common foundation in the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV) but diverge in both graphic representation and conceptual interpretation. By mapping Armenian practices against the Leiden Conventions and EpiDoc encoding standards, the study identifies areas of alignment as well as points of divergence that require particular attention.

3.1. Damaged and Missing Letters

The Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV) distinguishes carefully between two cases: a dash (–) for each missing character, with the number of dashes equaling the number of lost letters, and an ellipsis (…) for an unknown number of missing letters. These correspond respectively to Leiden’s sublinear dots and ellipsis, and to EpiDoc <gap quantity=“n” unit=“character”/> and <gap extent=“unknown”/>. Later Armenian publications frequently collapse these two cases, employing ellipses for both. While this simplification improves readability, it diminishes palaeographic precision. For example, in the inscription (DHV/5, no. 828) (

Figure 2), the missing characters are clearly represented with three dots.

By comparison, the Leiden Conventions and EpiDoc offer a much more differentiated framework. They distinguish between visible but illegible letters, erased or corrected text, lacunae of known or unknown extent, and other fine-grained cases. Armenian conventions, by contrast, collapse these nuances into just two categories: (–) for known missing characters and (…) for unknown ones, with later publications often reducing both to a single ellipsis. Categories such as erased versus corrected text, or illegible versus entirely lost characters, are usually relegated to the commentary rather than encoded in the transcription line.

A further structural difference concerns how information is distributed within editions. In DHV, missing or unclear letters are not always shown directly in the transcription line but are explained in the accompanying Commentary (Ծանոթագրություն), which specifies whether letters are damaged, uncertain, or supplied from earlier witnesses. By contrast, Leiden-based systems expect such distinctions to appear directly in the transcription itself. For example, letters ambiguous outside their context may be marked as ạḅc̣ and encoded in EpiDoc <unclear>abc</unclear>, while vestiges of illegible letters are represented as +++ and encoded as <gap reason=“illegible” quantity=“3” unit=“character”/>. This comparison underscores a fundamental difference: Armenian editions often distribute palaeographic detail between transcription and commentary, whereas Leiden and EpiDoc integrate it directly into the line of transcription.

Figure 5.

The restoration of the damaged letters in DHV.

Figure 5.

The restoration of the damaged letters in DHV.

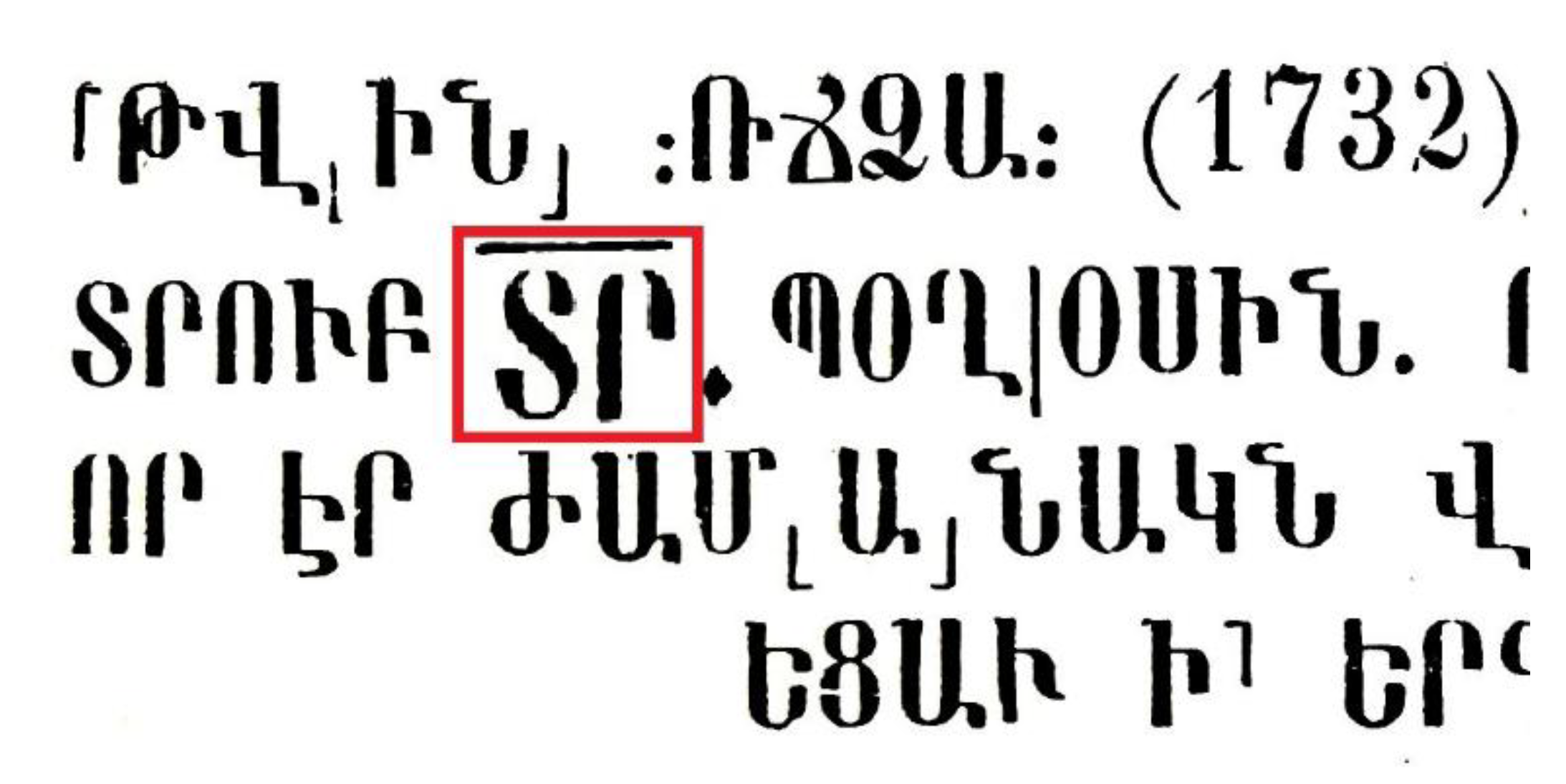

3.2. Restorations, Honorifics, Redundancies, and Abbreviations

Armenian practice is not uniform across editions. In DHV, ⌈…⌉ denotes restorations, corresponding to Leiden [ ] and to EpiDoc <supplied reason=“lost”>, while […] indicates redundant letters, corresponding to EpiDoc <surplus>. Later publications often collapse this distinction, using [ ] for restorations and leaving no clear symbol for redundancies. This shift erases the precision of the DHV system and introduces ambiguity in digital encoding.

The divergence extends further. Grigoryan reverses the DHV usage of ⌈…⌉ and ⎣…⎦; Karapetyan applies ⌈…⌉ to restorations and parentheses to expansions [

26]; Kortoshyan adopts [ ] for restorations and parentheses for abbreviations [

34]. Another important difference from Leiden is that Armenian conventions do not define a separate category for letters that have disappeared from the stone but were recorded by a previous editor. In Armenian editions these are marked simply as restored characters, while the commentary notes which earlier scholar last saw them. In Leiden/EpiDoc, by contrast, such cases can be encoded explicitly as <supplied evidence=“previouseditor”>.

Abbreviations are likewise treated differently. DHV draws a clear line between ordinary abbreviations and sacred abbreviations marked with honorific signs (overlines). Ordinary abbreviations are expanded using brackets ⎣…⎦, as in ԹՎ (“year”) → թվին, while later publications substitute parentheses, collapsing the visual and conceptual distinction. Sacred abbreviations, such as ՍԲ̅ → Սուրբ (“Holy”), Ա̅Յ̅ → Աստուած (“God”), and Տ̅Ր̅ → Տէր (“Lord”), are generally not expanded in DHV, preserving their sacred character. Later editions, however, often expand even these forms, for example rendering Տ̅Ր̅ as Տ(է)ր.

In EpiDoc, both practices can be encoded consistently: <abbr><expan> when expansions are supplied, or <hi rend=“superscript”> when the honorific form is preserved without expansion. Armenian corpora therefore require clear editorial policy at the project level to decide whether to follow the DHV convention of non-expansion (

Figure 6) or the later convention of expanded transcription (

Figure 7).

3.3. Ligatures and Line Breaks

Ligatures are consistently visible in DHV drawings, but they are not marked in the transcriptions themselves. In later publications, the ligatured letters may be connected by underlining, italics, or omitting explicit marking altogether. In EpiDoc, ligatures can be represented either as <g type=“ligature”> or through <choice><abbr/><expan/></choice>, depending on whether the ligature is treated as a palaeographic feature or as an abbreviation requiring expansion. This flexibility allows Armenian practice to be captured with precision, but only if the editorial policy defines clearly how ligatures will be encoded [

40].

Line breaks present fewer difficulties. DHV employs the symbol “/”, while some later publications use either “/” or a vertical bar “|”. Both map directly onto the <lb/> element in EpiDoc and therefore pose no interoperability challenges.

A recurring pattern is that DHV often relies on accompanying drawings to display ligatures in detail, including distinctions such as կապգիր (cursive ligature), կցագիր (connected ligature), փակգիր, փակագիր (monogram), and ծածկագիր (cryptogram). These features are explained in the commentary but not consistently reflected in the transcription line. For digital encoding, however, such details must be captured explicitly to ensure they are machine-actionable rather than remaining only in descriptive notes (

Figure 8).

3.4. Authorial and Scribal Signs

Decorative motifs such as crosses, rosettes, and architectural elements are not normally reproduced in the transcription line, but they are visible in accompanying drawings and sometimes mentioned in descriptive notes. Armenian editions therefore convey this information through multiple channels—transcription, drawing, and commentary—without necessarily integrating it into a single textual layer.

Some original graphic signs, however, are carried directly into the transcription. For example, the mark “: :“ frequently functions as a numeral indicator. These are faithfully preserved in DHV, reflecting the Armenian practice of reproducing semiotic features of the stone within the line of text (

Figure 9). A particularly common case is the use of two dots (: :) flanking a letter to indicate numerals, though the same sign can also serve as a word divider or general punctuation. In Armenian usage, the single colon-like mark (:) often functions as a full stop at the end of a sentence, highlighting its polyvalent role in inscriptional practice. In EpiDoc, these signs can be encoded with <g type=“punct” subtype=“numeral-marker”> for numeral indicators, <g type=“word-divider”> for dividers, and <g type=“fullstop”> for sentence-ending colons.

Armenian inscriptions also preserve authorial formulas such as “գրեցաւ” (grecʿaw, “was written by”), which identify the scribe or stonecutter. These function as agentive signs, comparable to colophons in manuscript traditions or signatures in other epigraphic corpora. Their systematic documentation ensures that Armenian corpora capture not only the commemorative content of inscriptions but also the practices and identities of their creators.

Later publications continue this approach but with further simplification: abbreviations and insertions are marked with parentheses rather than specialized signs, while line breakers (/) remain consistent (

Figure 10). These changes reflect a shift in editorial practice rather than a loss of information, since explanatory notes still provide details about abbreviations, restorations, and other palaeographic features.

For digital epigraphy, however, this distribution of information across transcription, commentary, and drawing presents a challenge. If damaged letters, ligatures, or decorations appear only in commentary or illustrations, they are not immediately available for computational analysis or cross-corpus comparison. To ensure both fidelity to Armenian scholarly tradition and interoperability with other corpora, such details must be recorded explicitly at the text level as well as in commentary, using EpiDoc elements such as <gap>, <unclear>, <g type=“ligature”>, and <figure>. In this way, the richness of Armenian editions is preserved while making the data fully usable in digital collections.

This synthesis illustrates the central tension of Armenian editorial traditions: the rigorous but commentary-dependent system of DHV versus the simplified and accessible conventions of later editions. It underscores the necessity of harmonized encoding strategies that retain palaeographic and semiotic detail while ensuring usability within international digital corpora.

Figure 9.

The principle of date decipherment in DHV.

Figure 9.

The principle of date decipherment in DHV.

Figure 10.

The simplified system of signs in later editions.

Figure 10.

The simplified system of signs in later editions.

Table 1.

Crosswalk table of editorial conventions in epigraphic editions (Panciera/EDH, SEG/DDb, Armenian DHV, later editions, and EpiDoc)

v.

Table 1.

Crosswalk table of editorial conventions in epigraphic editions (Panciera/EDH, SEG/DDb, Armenian DHV, later editions, and EpiDoc)

v.

| Description |

Panciera/EDH |

SEG/DDb |

Armenian (DHV) |

Armenain (Later editions) |

EpiDoc |

| Line breaks |

abc / abc |

|

աբգ / աբգ; աբգ | աբգ |

աբգ / աբգ; աբգ | աբգ |

<lb n=“1”/>first line

<lb n=“2”/>second line |

| Word divided across lines |

abc/def |

αβγ-

δεζ |

աբգ/աբգ; աբգ|աբգ |

աբգ/աբգ; աբգ|աբգ |

<lb n=“1”/>αβγ<lb n=“2” break=“no”/>δεζ |

| Text divisions |

abc // abc |

|

|

|

<div type=“textpart”>…</div> |

| Clear but incomprehensible letters |

ABC |

AΒ |

|

|

<orig>abc</orig> |

| Letters ambiguous outside context |

ạḅc̣ |

α̣β̣ |

|

|

<unclear>αβ</unclear> |

| Lacuna, extent unknown |

[---] |

[ ] |

--- |

… ; […] |

<gap reason=“lost” extent=“unknown” unit=“character”/> |

| Lacuna, approximate extent |

[c . 5] |

|

|

|

<gap reason=“lost” quantity=“5” unit=“character” precision=“low”/> |

| Characters lost, lacuna |

[...] |

[...] |

|

|

<gap reason=“lost” quantity=“3” unit=“character”/> |

| Vestiges of letters visible but illegible |

+++ |

... |

|

|

<gap reason=“illegible” quantity=“3” unit=“character”/> |

| Omitted letters; added by editor |

<abc> |

<αβ> |

⎣աբգ⎦ |

(աբգ) |

<supplied reason=“omitted”>αβ</supplied> |

| Expansion of abbreviation |

a(bc) |

α(βγ) |

|

|

<expan><abbr>α</abbr><ex>βγ</ex></expan> |

| Characters lost but restored |

[abc] |

[αβ] |

⌈աբգ⌉ |

[աբգ] |

<supplied reason=“lost”>αβ</supplied> |

| Erased |

[abc] |

[αβ] |

|

|

<del rend=“erasure”>αβ</del> |

| Text read by previous editor, now lost |

abc |

|

|

|

<supplied reason=“undefined” evidence=“previouseditor”>αβγ</supplied> |

| Ligatured letters |

ab͡ |

|

|

|

<hi rend=“ligature”>ab</hi> |

| Erased and overstruck / corrected |

«def» |

|

|

|

<subst><del rend=“corrected”>abc</del><add place=“overstrike”>def</add></subst> |

| Text added by ancient hand |

`abc’ |

|

|

|

<add place=“above”>αβ</add> |

| Line lost |

[- - - -] |

|

|

|

<gap reason=“lost” quantity=“1” unit=“line”/> |

| Line(s) possibly lost |

[- - - ?] |

|

|

|

<gap reason=“lost” quantity=“1” unit=“line”><certainty match=“..” locus=“name”/></gap> |

| Letters suppressed by editor |

{abc} |

{αβ} |

[աբգ] |

{աբգ} |

<surplus>αβγ</surplus> |

| Letters corrected by editor |

⌈abc⌉ |

<αβ> |

|

[աբգ] |

<choice><corr>αβ</corr><sic>βα</sic></choice> |

| Abbreviation: expansion unknown |

a(---) |

|

|

|

<abbr>α</abbr> |

| Editor’s note |

(!) |

|

|

|

<note>!</note>, <note>sic</note>, <note>e.g.,</note> |

| Space left on stone |

(vac.3) |

v. ; vacat |

|

|

<space quantity=“1” unit=“character”/> | <space quantity=“3” unit=“character”/> |

| Numeral (Roman|Greek) |

X̅I̅̅I̅ |

α’ ; ‚α |

|

|

<num value=“12”>XII</num> | <num value=“1”>α</num> |

| Symbol |

(leaf) |

|

|

|

<g ref=“#leaf”/> |

| Markers of numeral |

|

|

:աբգ: |

|

<g type=“punct” subtype=“numeral-marker”>::</g> |

| Separation |

|

|

|

|

<g type=“word-divider”>:</g> |

| End of Sentence |

|

|

|

|

<g type=“fullstopr”>:</g> |

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis demonstrates that Armenian epigraphy is rooted in a systematic editorial apparatus established by the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV), yet over time this framework was reshaped by later publications, producing a landscape of overlapping but inconsistent practices. On the one hand, DHV volumes set a rigorous standard, distinguishing carefully between diplomatic and interpretative transcription and introducing a coherent system of signs for restorations, redundancies, abbreviations, ligatures, and honorifics. On the other hand, later editions, especially from the 1990s onward, opted for simplification: specialized symbols were replaced with typographic substitutes, and some categories were reinterpreted or collapsed. This dual trajectory has left Armenian scholarship with a fragmented set of conventions that must be reconciled before integration into international digital infrastructures can take place.

From a philological perspective, the inconsistencies are significant. The same sign can denote different categories depending on the edition: for example, [ ] mark redundant letters in DHV but restorations in later works. Similarly, the distinction between “known” and “unknown” missing characters, expressed in DHV through dashes versus ellipses, is often erased in more recent publications. Such shifts not only obscure palaeographic precision but also create risks of misinterpretation when Armenian inscriptions are compared across corpora. In the absence of explicit documentation, readers may attribute meanings that were never intended by the original editors.

For digital encoding the consequences are even more direct. International frameworks such as the Leiden Conventions and the EpiDoc TEI schema provide categories for nearly all of the editorial phenomena observed in Armenian inscriptions: <gap> for missing text, <supplied> for restorations, <surplus> for redundant letters, <abbr>/<expan> for abbreviations, and <hi rend=“superscript”> for honorifics. In principle, the alignment is straightforward. The complication arises not from a lack of categories but from shifting and ambiguous usage within Armenian practice. Thus, if a bracket is used for two different functions, without a consistent editorial policy, the same EpiDoc element may be used to represent incompatible traditions, undermining the reliability of the corpus.

To address this kind of overlaps, three measures are essential:

Crosswalk tables – systematic mapping of DHV and later Armenian conventions against Leiden sigla and EpiDoc elements, with explicit notes where functions diverge. The comparative table presented in this article illustrates that nearly every Armenian phenomenon has a place in the Leiden/EpiDoc framework but requires careful documentation.

Corpus-level editorial guidelines – policies must be established at the project level (e.g., Armenian Epigraphic Corpus, Noratus Digital Twin, RAA datasets), defining how specific signs will be interpreted. For example, editors must decide whether [ ] in a given corpus encodes <supplied> or <surplus>. These guidelines ensure internal consistency.

Metadata documentation – each transcription should carry metadata recording which tradition it follows (DHV, later simplified, or hybrid). This allows both scholars and machines to contextualize the data correctly, avoiding the conflation of practices.

As shown in this example, the strategy applied here is dual-track encoding. The granular track applies the full Leiden/EpiDoc distinctions for maximum precision, interoperability, and participation in international infrastructures such as EFES, Trismegistos, or Pelagios. The simplified track reflects Armenian scholarly usage more faithfully, preserving the local tradition where fewer categories are recognized. Rather than privileging one system over the other, this dual approach ensures that Armenian inscriptions are both globally comparable and locally authentic.

This model also resonates with the theoretical perspectives adopted. From a semiotic standpoint, Armenian editorial signs are not merely technical devices but interpretive acts, part of a triadic relation between the carved form, its linguistic value, and the editor’s intervention. Their variation across publications represents not only graphic substitution but also hermeneutic shifts. Diachronic graphemics further shows that these signs form part of a layered writing system, where typographic replacements and functional reassignments accumulate over time. Recognizing these dynamics strengthens our ability to model Armenian epigraphy within international ontologies without erasing its historical depth.

Finally, adopting this model secures alignment with FAIR principles. By making Armenian inscriptions findable (with persistent identifiers), accessible (through open repositories), interoperable (via standardized EpiDoc encoding), and reusable (thanks to transparent documentation), this strategy guarantees long-term preservation and integration into the global Cultural Heritage Cloud. In this way, Armenian epigraphy is not confined to the margins of classical scholarship but emerges as a contributor to global comparative studies, offering insights into Christian epigraphy, diasporic communities, and cross-cultural transmission.

5. Conclusions

Armenian epigraphy is characterized by a shared foundation in the Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (DHV) but also by significant variation in later publications, which introduced simplifications and reassignments of editorial signs. These differences reflect both scholarly adaptation and practical concerns but create challenges for consistency, digital interoperability, and long-term reuse.

This study demonstrates that understanding of local epigraphic principles and their harmonization with international standards such as the Leiden Conventions and EpiDoc TEI is both feasible and desirable. By documenting divergences transparently and establishing clear crosswalks, Armenian epigraphic heritage can be made interoperable and accessible for the global research community

The principal innovation proposed here is a dual-track encoding strategy. One track enables granular mapping of Armenian signs to the full set of Leiden/EpiDoc distinctions, supporting maximum precision and comparability across corpora. The other offers a simplified schema faithful to Armenian usage, ensuring continuity with local scholarly traditions. Together, these approaches make Armenian inscriptions both internationally legible and culturally specific.

Aligning Armenian epigraphy with FAIR data principles guarantees that inscriptions will be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable in global digital infrastructures. This strengthens their integration into platforms such as EFES, Trismegistos, or the European Cultural Heritage Cloud and ensures their availability for future research, education, and heritage preservation.

By situating Armenian editorial conventions within an international framework, this work not only safeguards a vital Christian epigraphic tradition but also enriches the global repertoire of inscriptional practices, offering new resources for comparative cultural heritage research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H Tamrazyan; methodology, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan; validation, A. Harutyunyna; formal analysis, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan and A. Harutyunyna; investigation, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan, A. Harutyunyna; resources, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan, A. Harutyunyna; data curation, H. Tamrazyan; writing—original draft preparation, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan, A. Harutyunyna; writing—review and editing, H. Tamrazyan, G. Hovhannisyan, A. Harutyunyna; visualization, H. Tamrazyan, A. Harutyunyna; supervision, H. Tamrazyan; project administration, H. Tamrazyan; funding acquisition, H. Tamrazyan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) for the purposes of grammatical review and improving clarity and accuracy in English. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DHV |

Divan Hay Vimagrutʿyan (Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy) |

| CIL |

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum |

| IG |

Inscriptiones Graecae |

| EpiDoc |

Epigraphic Documents in TEI XML |

| TEI XML |

Text Encoding Initiative Extensible Markup Language |

| FAIR |

Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable |

| EAGLE |

Electronic Archive of Greek and Latin Epigraphy |

| OCIANA |

Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia |

| EFES |

Epigraphic Front-End Services |

References

- O. Mulholland, ‘Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum’.

- A. Böckh, Corpus inscriptionum Graecarum. Officina Academica, 1853.

- R. S. Bagnall, The Oxford handbook of papyrology. in Oxford Handbooks. New York: Oxford university press, 2009.

- J. S. Cooper, ‘Babylonian beginnings: the origin of the cuneiform writing system in comparative perspective’, p. 72, 2004.

- J. F. Healey, The early alphabet. Berkeley: University of California Press ; [London] : British Museum, 1990. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://archive.org/details/earlyalphabet0000heal.

- S. Orlandi, R. Santucci, F. Mambrini, and P. M. Liuzzo, Digital and Traditional Epigraphy in Context: Proceedings of the EAGLE 2016 International Conference. Sapienza Università Editrice, 2017.

- I. Rossi and A. Santis, Crossing Experiences in Digital Epigraphy: From Practice to Discipline. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Vértes, Digital Epigraphy | Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. Accessed: Oct. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://isac.uchicago.edu/research/publications/misc/digital-epigraphy.

- T. Elliott, ‘Epigraphy and Digital Resources’, in The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, C. Bruun and J. Edmondson, Eds, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 0. [CrossRef]

- T. Greenwood, ‘A Corpus of Early Medieval Armenian Inscriptions’, Dumbart. Oaks Pap., vol. 58, p. 27, 2004. [CrossRef]

- H. Tamrazyan and G. Hovhannisyan, ‘Preserving Endangered Heritage: Integrating GeoNames/Pleiades, Armenian Toponyms and Regularization for Cultural Identity Preservation in Conflict Zones’, Int. J. Humanit. Arts Comput., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 224–248, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Tamrazyan and G. Hovhannisyan, ‘Digital Guardianship: Innovative Strategies in Preserving Armenian’s Epigraphic Legacy’, Heritage, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 2296–2312, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M.-F. (1802-1880) A. du texte Brosset, Les ruines d’Ani, capitale de l’Arménie sous les rois Bagratides, aux Xe et XIe s. : histoire et description. Atlas / par M. Brosset... 1860. Accessed: Oct. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62148748.

- Ղ. Ալիշան, Սիսական: տեղագրութիւն Սիւնեաց աշխարհի. Ի Մխիթարեան Վան ի Ս. Ղազար, 1893.

- A. Harutyunyan, ‘Armenian Epigraphy’, Hist. Cult. Herit. Armen., 2022, Accessed: Oct. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/92703626/A_Harutyunyan_Armenian_Epigraphy_Historical_and_Cultural_Heritage_of_Armenia_edited_by_Kh_Harutyunyan_Yerevan_2022_pp_83_88_in_English_.

- Հ. Ա. Օրբելի, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 2, vol. 2, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՌ ԳԱ հրատ., 1960. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_2/book/content.html.

- Հ. Ա. Օրբելի, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 1, vol. 1, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՌ ԳԱ հրատ., 1965. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_1/book/content.html.

- Ս. Բարխուդարյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 3, vol. 3, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՌ ԳԱ հրատ., 1967. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_3/book/content.html.

- Ս. Բարխուդարյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 4, vol. 4, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՌ ԳԱ հրատ., 1973. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_4/book/content.html.

- Ս. Բարխուդարյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 5, vol. 5, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՌ ԳԱ հրատ., 1982. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_5/book/content.html.

- Ս. Ավագյան; Հ. Ջանփոլադյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 6, vol. 6, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՍՍՀ ԳԱ հրատ., 1977. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_6/book/content.html.

- Գ. Մ. Գրիգորյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության, Պ. 7, vol. 7, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՀ ԳԱԱ «Գիտություն»., 1996. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_7/book/content.html.

- Գ. Մ. Գրիգորյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության 8, vol. 8, 10 vols. Երևան: ՀՀ ԳԱԱ «Գիտություն»., 1999. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_26/book/content.html.

- Ս. Գ. Բարխուդարյան, ՂաֆադարյանԿ. Գ., and ՍաղումյանՍ. Տ., Դիվան հայ վիմագրության , Պր. 9, vol. 9. Երևան: ՀՀ ԳԱԱ «Գիտություն» հրատ., 2012. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_9/book/content.html.

- Ս. Գ. Բարխուդարյան, Դիվան հայ վիմագրության , Պր. 10, vol. 10.։ Խմբագր. Գ. Գ. Սարգսյան, Ա. Է. Հարությունյան, Կ. Տ. Ասատրյան, Երևան: ՀՀ ԳԱԱ «Գիտություն» հրատ., 2017. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://serials.flib.sci.am/openreader/vimagrutyun_10/book/content.html.

- Ս. Կարապետյան, ԲՈՒՆ ԱՂՎԱՆՔԻ ՀԱՅԵՐԵՆ ՎԻՄԱԳՐԵՐԸ. 2021. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://raa-am.org/բուն-աղվանքի-հայերեն-վիմագրերը/.

- Ս. Կարապետյան, ՀՅՈՒՍԻՍԱՅԻՆ ԱՐՑԱԽ. 2021. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://raa-am.org/հյուսիսային-արցախ/.

- Լ. Թաշճյան, ՑԵՂԱՍՊԱՆՈՒԹՅՈՒՆԸ ՎԵՐԱՊՐԱԾՆԵՐԻ ԾՆՆԴԱՎԱՅՐԵՐԸ ԼԻԲԱՆԱՆԻ ՏԱՊԱՆԱԳՐԵՐՈՒՄ, vol. 18. Երևան: ՀՃՈՒ ՀՐԱՏԱՐԱԿՈՒԹՅՈՒՆ, 2018. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://raa-am.org/ցեղասպանությունը-վերապրածների-ծննդա/.

- Հ. Պետրոսյան, Խաչքար. Երևան: Երևան Փրինթինֆո, 2008.

- Ա. Հարությունյան, ‘Տաթեւի վանքի վիմագրերի նախընթաց հրատարակութիւնները եւ ներկայ անելիքները’, Հանդէս Ամսօրեայ.

- D. Sterling, Conventions in Editing. A Suggested Reformulation of the Leiden System. 1969. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://dokumen.pub/conventions-in-editing-a-suggested-reformulation-of-the-leiden-system.html.

- G. Bodard and S. Stoyanova, ‘Epigraphers and Encoders: Strategies for Teaching and Learning Digital Epigraphy’, in 10.5334/bat, Ubiquity Press, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Մ. Բարխուդարյան, Աղվանից երկիր և դրացիք: Արցախ. Երևան: Գանձասար, 1999.

- Ր. Քորթոշյան, ՀԱԼԵՊԻ ԱՐՁԱՆԱԳՐՈՒԹՅՈՒՆՆԵՐԸ, vol. 16. Երևան: ՀՃՈՒ ՀՐԱՏԱՐԱԿՈՒԹՅՈՒՆ, 2013. Accessed: Sept. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://raa-am.org/հալեպի-արձանագրությունները/.

- K. Parker, ‘Peirce’s Semeiotic and Ontology’, Trans. Charles Peirce Soc., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 51–75, 1994, Accessed: Oct. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40320453.

- U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press, 1976. Accessed: Sept. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16xwcfd.

- G. T. Tanselle, Textual Criticism and Scholarly Editing. Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 1990.

- M. Neef, Die Graphematik des Deutschen. Walter de Gruyter, 2011.

- K. Berg, Die Graphematik der Morpheme im Deutschen und Englischen. De Gruyter, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ս. Սաղումյան, ‘Համառոտագրությունը հայ վիմագրության մեջ’, «Լրաբեր Հասարակական Գիտությունների», vol. 4, May 1978, Accessed: Oct. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/39601/edition/35516.

| i. |

|

| ii. |

|

| iii. |

|

| iv. |

“Conventional Signs”: A dash (–) marks the broken letters in the original text (as shown in the drawing), with the number of dashes corresponding to the number of missing letters. Dots (…) mark broken letters in the original text (drawing), regardless of their number. Brackets ⌈ ⌉ mark the restorations of broken letters (in the interpretative transcription). Brackets ⎣ ⎦ mark omissions left by the scribe in the original text—letters skipped, abbreviated, or omitted without authorization (in the interpretative transcription). Square brackets [ ] mark superfluous letters present in the original text (in the interpretative transcription). A slash (/) marks the line divisions of the original text (in the interpretative transcription). |

| v. |

Note: Column headings follow conventions used in major corpora. EpiDoc examples illustrate recommended TEI-XML markup. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).