1. Introduction

When it comes to preserving the cultural heritage of ancient civilizations, it is necessary to use our imagination to reconstruct the environment of societies that have disappeared, based on the excavated remains and chance discoveries. The knowledge we have of them can never be definitive and is in constant evolution.

This duty of memory involves three categories of actors: the researchers who produce knowledge, experts in their field; the public, whose level of knowledge varies and thus requires an adapted level of discourse; and finally, the cultural mediators, responsible for bridging the gap between the two and transmitting the results of research outside academic circles. The different areas are generally very compartmentalized, and the tools used for research are usually dedicated to experts, manipulating raw data, whereas the places (physical or virtual) that welcome the public favor remarkable displays. The latter, moreover, most often concern concrete objects, monuments and artefacts, allowing a better projection of the imagination. Intangible subjects such as languages and linguistics, considered too complex to grasp and transmit, are deemed to be of secondary importance. The development of digital technologies, however, provides an opportunity to reassess this paradigm by offering new experience of research and dissemination of results through new digital heritage practices.

Historically, linguistics was one of the first sectors of the Humanities to develop computing tools (databases) for statistical analysis of textual sources (computational linguistics), within a broader discipline known as Humanities Computing. But with the spread of digital technology in the broadest sense, it is now a question of transforming these tools exclusively into the service of research by upgrading them with features for knowledge transfer, valorization of results and dissemination to a wide public. Thus, the place where research is actually carried out would become its own cultural mediator, taking directly into account the different types of users and their different levels of knowledge, both of the subject and of the mastery of the digital tool itself.

The online digital dictionary of Ancient Egyptian VÉgA

1 was designed with this in spirit. It is the product of a research collaboration between the different fields involved: Egyptologists (who initiated the project), Computer Engineers and Designers. It is a technological program developed within the LabEx Archimede (ANR-11 LABX-0032-01), supported by the University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 and CNRS, in partnership with the digital design agency intactile DESIGN, specializing in the creation of digital HMIs in expert fields (aeronautics, medical, energy, agriculture...). The aim of the Egyptologists was not to draw up specifications themselves and wait for the computer engineers to deliver, but to engage in a genuine dialogue with digital technology professionals in order to develop a high-performance and coherent tool designed to represent and model the evolving knowledge of the ancient Egyptian lexicon in four languages (French, English, German, Arabic) and accessible directly via a Web browser. In this respect, the project is a clear example of the digital humanities [

1], ‘non pas parce qu’il modifie les pratiques des chercheurs, mais parce qu’il les améliore et les rend plus performants en soumettant la technologie informatique à leurs besoins et à leurs spécificités plutôt qu’en leur demandant de se soumettre à la rationalité abrupte d’une base de données.’ [

2] (§4)

The project started in 2010, with the first version of the software delivered first to the project team in December 2014 and opened to the public in May 2017 under a Version 3. But as it is a tool in constant evolution, it had undergone a massive makeover in 2023, and it is currently running at V4.0. Throughout this process, the team had to deal with various issues, the solutions to which can sometimes only be provided gradually:

How to model linguistic knowledge and make it accessible to different types of audience.

How to create a common environment for research practice and dissemination of results.

How to get the principles of knowledge engineering adopted by a scientific community whose methods are essentially based on print culture and the permanent questioning of sources for each new analysis.

How to expand the infrastructure to other areas.

How to transfer knowledge to other tools, exclusively didactic.

All these points will be addressed in this chapter, to participate in the creation of a new epistemology of digital Egyptology.

2. Modelling Language Knowledge

From the Renaissance onwards, Egyptian hieroglyphs have aroused the interest of an ever-widening public. Because of their ‘naturalistic’ and extremely precise figurative character, many scholars and amateurs wanted to see them as a system of ideograms that could be understood independently of the knowledge of the language spoken by the ancient Egyptians. Even today, this idea is persistent, and many curious people try to learn how to decipher these signs whose meaning seems so obvious. Most people, however, do not go beyond this stage, once they realise that they are indeed a system of graphic representation of sounds, i.e. a mainly phonetic script noting a language in its own right, in all its grammatical complexity. 2

Egyptology as a scientific discipline was born in 1822, when J.-Fr. Champollion realised that “[il] tient son affaire!”. With his elucidation of the hieroglyphic system, he opened the door to the study of this ancient language and the culture of ancient Egypt, where writing is omnipresent. The first dictionaries [

6,

7,

8] and grammars [

9,

10,

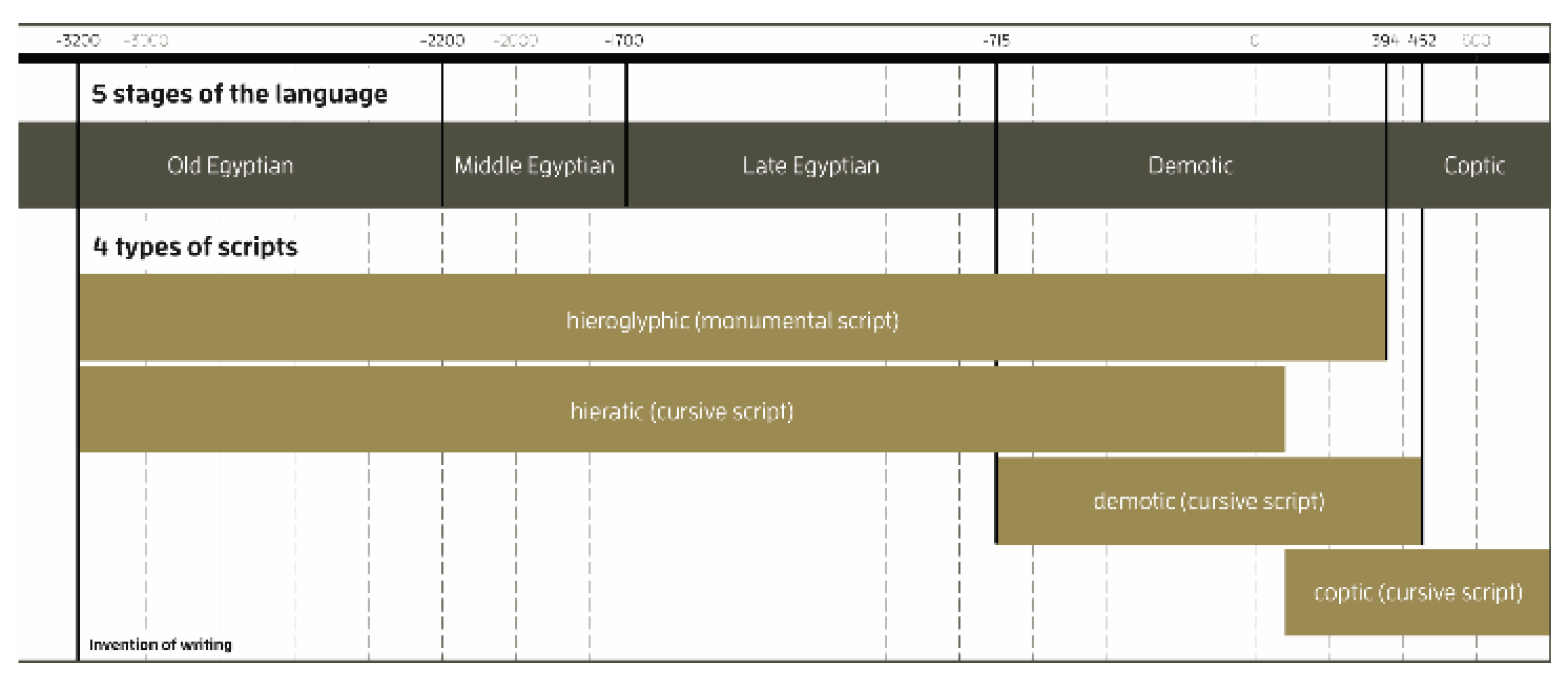

11] were soon produced, and philologists began a frantic study of this abundant documentation, covering 3,000 years of civilisation. Several language states were distinguished, from the Old Egyptian spoken in the 4

th millennium BCE to the Demotic of the last pharaohs, via Middle Egyptian and Late Egyptian

3. On the other hand, only the monumental texts are written in hieroglyphs, the common writing mode being the hieratic cursive. This was itself replaced by a demotic form during the first millennium BCE (

Figure 1).

In 1897, the Berlin Academy of Sciences began a vast project for a complete dictionary of ancient Egyptian, considering all known sources, which became the reference tool in lexicography that we know today: the

Wörterbuch der Ägyptische Sprache, edited by A. Erman and H. Grapow [

12]. The gathering of references, in the form of index cards,

4 was interrupted during the First World War and the five volumes were published between 1926 and 1931. They were followed by five volumes of references (

die Belegstellen) between 1935 and 1961. In total, 236 years of work - interspersed with two world wars - to make 16,000 lexemes accessible to the Egyptological community, based on sources dating from the very beginning of the twentieth century. Since then, no one has been able to make such an effort and the updates proposed has always been on the scale of a state of language, a period, a corpus or a restricted theme. These updates are then dispersed in such many sources of information, and the current philologist is forced to handle up to twenty-five different books to understand the meaning of a word from a diachronic point of view.

The Berlin team's approach of collection-analysis-publication has long been scientifically validated by lexicographers as the most relevant, but it suffers from three flaws, a fortiori in the case of the study of a dead language:

- 1)

The time required for execution is proportional to the mass of documentation to be processed, and the more exhaustive the dictionary is intended to be, the longer it will take. This also imposes a chronological limit on the sources considered, which can only be those known at a given time.

- 2)

Since publication can only take place once all the documentation has been processed, and since the analysis time is incompressible, a long period of time may elapse between the two, and the state of knowledge presented may not always reflect its actual state at the time of publication.

- 3)

The data and results produced are deeply interconnected, due to the need to master the meaning of all the words in a text extract to define a context of use for a single lexeme and to refine its understanding. These results are therefore, by definition, never definitive, as they are constantly being interpreted, depending on regular textual discoveries.

In reality, these are the limits imposed by the publication of a paper book, the only medium for disseminating knowledge that was available and mastered at the time of publication of these fundamental tools, and which is still widely used. Furthermore, faced with the multiplication of research centres, the exponential production of results, and thus the ever-increasing dissemination of data, traditional methods are becoming too slow to manage, and it is becoming necessary to think about new practices and new tools capable of handling all these settings, while maintaining the required scientific relevance. This means no longer thinking in terms of quantity of publications but in terms of quality of data structuring, to make them available in all their complexity, at any time, while allowing them to be interrogated in different, specific and reasoned ways.

Nowadays, only the digital medium offers the necessary conditions for the exploitation of such a mass of data, and several initiatives in this direction have been emerging throughout the world in recent years [

13,

14]. If the first ones were essentially focused on the digitisation of documents without any other computer processing than visualisation, the trend is evolving towards the constitution of large databases, giving rise to a new epistemology of digital Egyptology which only needs to be formalized today.

Although the use of digital tools is becoming increasingly widespread and we are all relatively efficient in mastering them, their development remains the business of specialized professionals. Egyptologists have the knowledge of the material sources they work with, but to design a digital tool - in our case, a dictionary - it seems unthinkable that the Academics should not rely on the expertise of computer engineers to transpose all our know-how into a field that is not their own. The aim of the Egyptologists behind the VÉgA was to provide an update on the current knowledge on the vocabulary of ancient Egyptian. The choice of a digital medium was motivated mainly by its plasticity, allowing the tool to be completed on a permanent basis, and thus to be made available without waiting for it to be completed, to be kept up to date with scientific discoveries, and to promote its dissemination to a public beyond the academic community. But this choice is not a minor one and goes beyond these apparent purely practical qualities. To ensure relevance, they turned to the digital design agency intactile DESIGN, which specializes in the design of HMIs for expert fields, thanks to a team made up of both designers and computer engineers. As a result, the apparently simple idea of making an online dictionary turned into a vast research project on the integration of Egyptology into the Digital Humanities and the application of the fundamental principles of knowledge engineering, implying a global questioning of Egyptological methods to develop tools reconciling research practice and dissemination of results.

According to the traditional method, the researcher constitutes his own database, specific to a study topic. After analysis, he or she publishes the results, accompanied at best by a corpus or a catalogue of sources, the structuring of which necessarily depends on the chosen line of research and conditions its use by default, which is difficult to divert. The researcher may also have to create different versions or multiply the databases according to the topics and repeat the whole process. Conversely, knowledge engineering is based on the creation and maintenance of a knowledge-based system (KBS) to solve complex problems by structuring data on an expert domain and representing knowledge explicitly through an ontology covering a maximum of aspects of the subject. This way, knowledge become available for any kind of inquiries, independently of the final form of the tool (or tools) for research and the visualisation of results [

15].

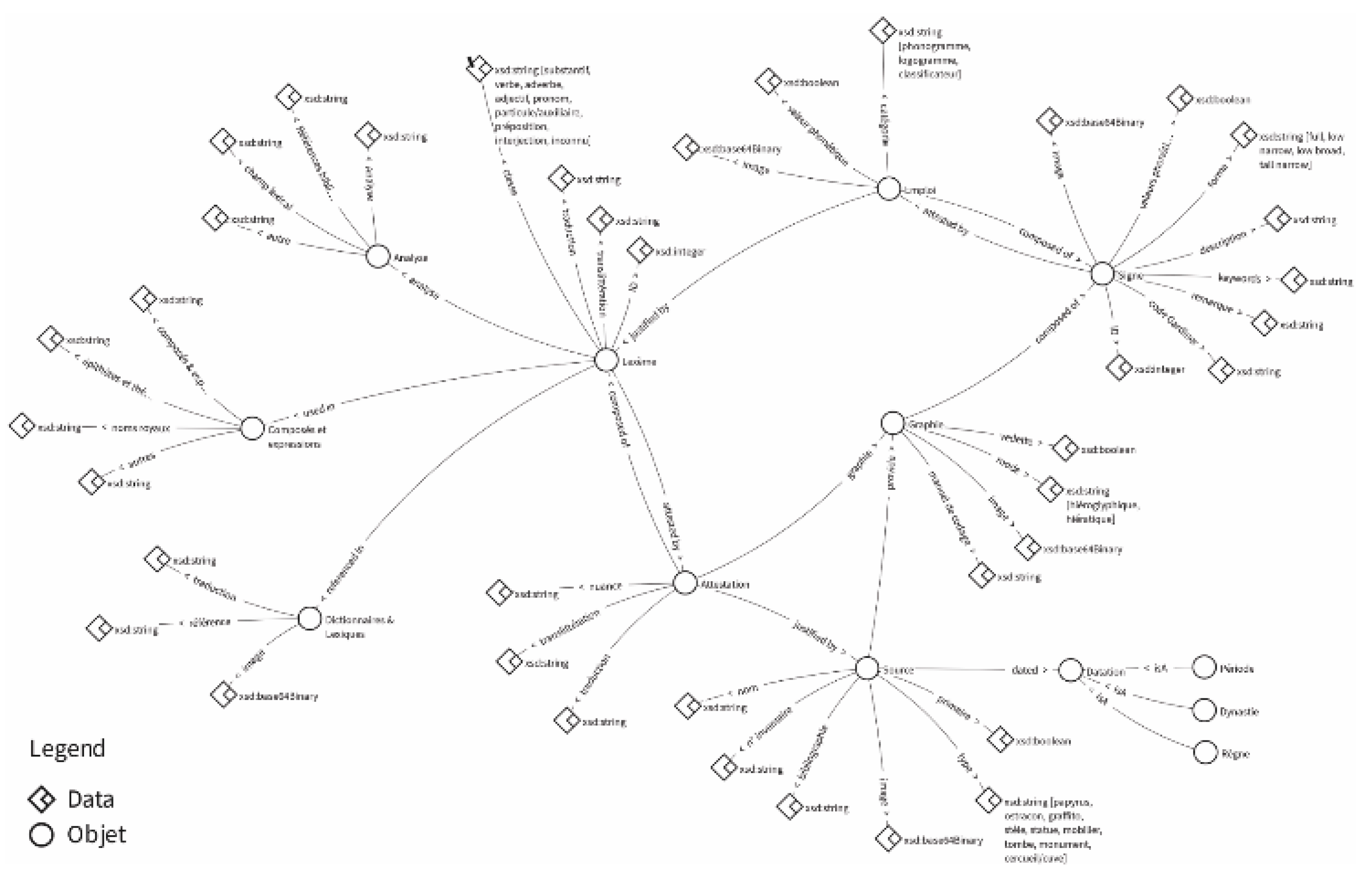

For VÉgA, the ontology is thus constituted on the scale of all the objects of Ancient Egyptian linguistics (

Figure 2), even though the first objective concerns only the lexicographical study. Indeed, it quickly became obvious that the study of a single lexeme is deeply linked to that of its written form (grammatology), of the signs that compose it (palaeography, semiology), of the textual source in which it is mentioned (philology), of the other words with which it shares a root (morphology, etymology), and of how its pronunciation can be reconstructed (phonology). In addition, there is data on the period in which it is used (chronology) and the regions where it is found (geography). Much knowledge is then accumulated for the study of a unique lexeme presented in a dictionary, but computer processing allows it to be capitalized upon and in turn exploited directly in tools dedicated to each of the other fields.

In practical terms, the data to be processed is massive and deeply interconnected. Approximately 20,000 lexemes must be recorded, each with between one and ten different spellings, the number of signs of which can vary greatly. Indeed, there is no rigorous orthography in Egyptian writing, each scribe being free to choose the combination of phonetic signs that is most meaningful in any given context, thus also playing on the ideographic aspect. Hence the importance of considering the paleographic and semiological clues of an attestation, to suggest an interpretation that is not truncated, as certain spellings can be highly contextual. Each attestation retained for a lexeme is also composed of a sequence of between five and fifty words, each pointing to the corresponding dictionary headwords. More than a hundred sources are considered, covering 3,000 years of history, itself divided into ten periods, thirty-two dynasties and nearly 350 kings. Finally, the contents of twenty-five dictionaries and lexicons are compiled. The same assessment can also be applied to the study of a single sign, thus multiplying the connections between objects. Based on this ontology, and to best respond to the problems of interconnected data and performance for the various applications envisaged, it was decided to develop a Document Graph database [

16] on OrientDB [

17]. In this way, it is also possible to update the database rapidly as new research areas are considered and new research tools are connected to it.

5

3. A Common Infrastructure for Research and Dissemination

From the outset, the Egyptologists had an idea of the tool they wanted to develop and the problems it should solve. However, their vision was restricted by their own limited knowledge of databases, system performance and programming languages. Moreover, in their dialogue with the computer scientists who were responsible for formalising this ontology and developing the KBS, they could only express a biased view of their working methods and basic needs, as part of their know-how, acquired during years of study, was now in the realm of the unconscious and beyond their comprehension. Conversely, from the point of view of knowledge engineering stricto sensu, only the performance of the search to retrieve data from the database is considered and the experience of the end user is rarely considered.

Nevertheless, what distinguishes digital humanities from simple computer processing (computing) is its capacity to propose a global environment of research and communication, thanks to adapted modelling and visualisation interfaces. To face this issue, the strength of the VÉgA project lies in the fact that it involves designers specialized in the design of digital HMIs. Because in no way the design work on the form of the final interface for consulting the dictionary can be reduced to a final aesthetic surfacing. It begins with the initial stages of structuring and representing the data in the KBS.

The intactile DESIGN agency uses a user-centred participatory design method, where innovation and creativity are expressed through collective intelligence [

18]. To achieve this, all the actors in the project are involved from the beginning of the process in codesign workshops: designers, computer scientists, experts in the field and end users. For VÉgA, the last two are Egyptologists, with experts in lexicography mastering the topic and philologist users, used to working with dictionaries. By starting to observe the practices and uses of the different researchers, the designers’ expertise enables them to highlight all the objects of research and their attributes, and thus to map the links and interactions between each. It is this first representation that will define the ontology and condition the structuring of the database, all of which will guide the interface choices for the final visualisation. Thus, by placing the user's experience at the heart of the approach and by intervening upstream, the designer manages to detach himself from the raw material of the database to propose an interface that best reconciles the needs of users with the imperatives of digital technology [

19].

The whole process follows the principles of the agile method. During the codesign workshops, a paper mock-up of the future interface is produced, where nothing is yet fixed, thus allowing scenarios to be played out and initial intuitions to be tested (

Figure 3). At the end of each workshop, an interaction storyboard is produced, formalising the paths followed, and with each iteration the prototype becomes increasingly robust, even before a single line of code has been written. In a second phase, the developers also work in sprints to encourage micro-testing and adaptability.

In its final form, the interface is intended to be minimalist so that the user can forget about it as much as possible and concentrate on his or her thoughts. In the same spirit, the point of entry into the database via the search field also allows to get away from the alphabetical order imposed by the medium of print, to offer an optimized, fluid and non-linear experience. Finally, navigation continues within the notes themselves, with links on each lexeme mentioned allowing the corresponding notes to be opened on the desktop and the search to be conducted in greater depth.

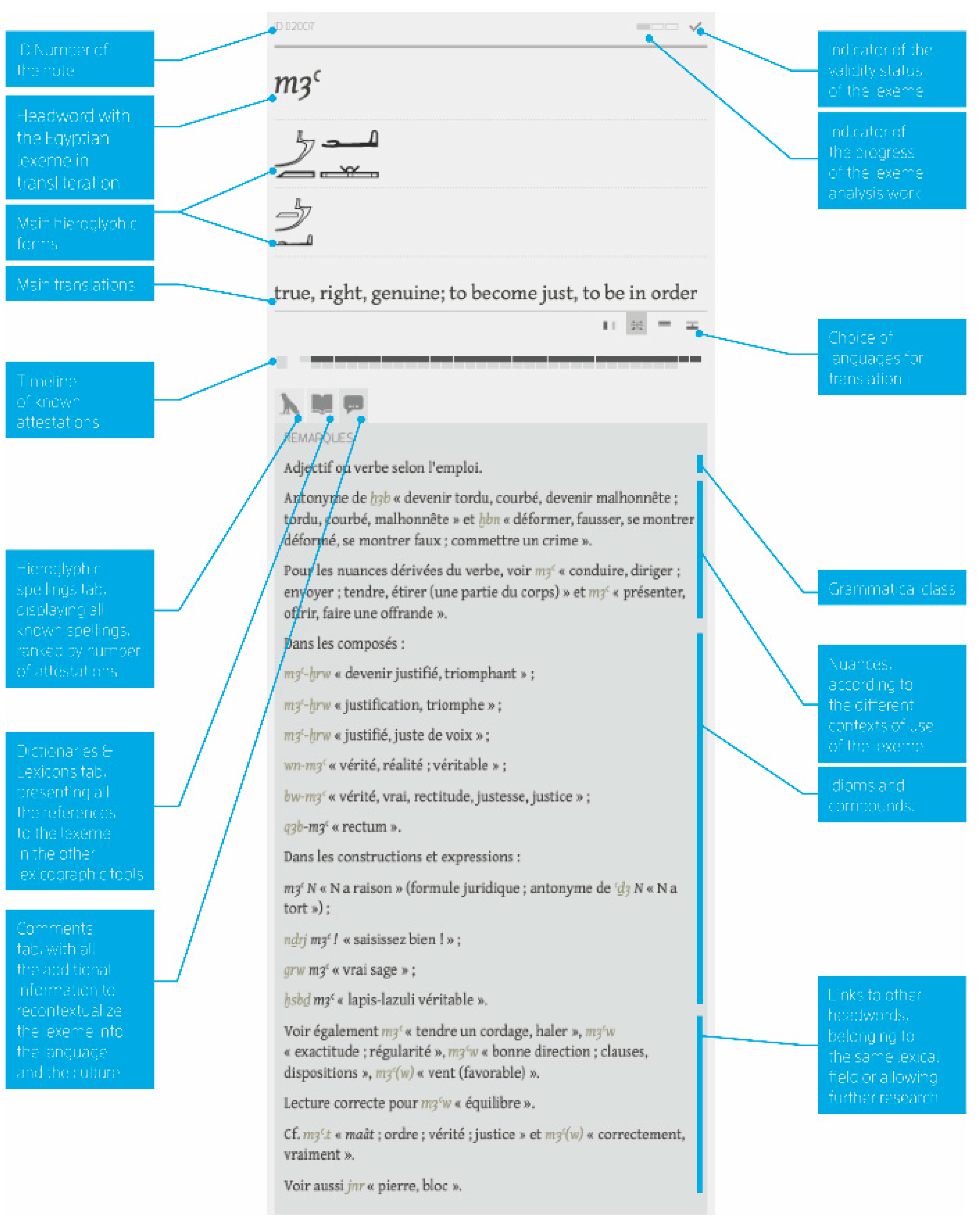

However, the main issue is the organisation of information spaces to address users with varying levels of knowledge and reduce the distance between scientific tools and popularisation. The interest of the digital format is therefore to be able to multiply the consultation spaces, with a general module in the header of the note presenting the basic information expected from a dictionary (the word in transliteration

6, its main written forms and its translation) and tabs dedicated to particular categories (

Figure 4). Some of these are mainly intended for experts (catalogue of sources, spellings, specialized publications mentioning the lexeme), others are more open, designed to place the word in its original language and culture in a broader sense. One finds idiomatic expressions, information concerning morphology and etymology, the associated lexical field, but also a summary of current debates and a bibliography dealing with the subject in greater depth. This encyclopaedic aspect, which is too often absent from the usual dictionaries, is nonetheless crucial for recontextualising the language and understanding the issues involved in vocabulary in the knowledge of ancient Egyptian culture and its dissemination to all audiences. Indeed, the work of the lexicographer is above all to define the categories of language specific to a given culture, to restore the categories of thought and the cognitive mechanisms that underlie them within the paradigm of the civilisation that uses them [

20] (p. 63-74). Vocabulary is thus the privileged gateway to the understanding of a disappeared culture in the broadest sense, and a dictionary can only become a veritable encyclopaedia covering all the facts of civilisation.

4. Time for Acculturation and Change

In this long-term project of creating and operating a KBS on the linguistics of ancient Egyptian, all the potential for capitalisation and generation of knowledge can only be put in place in a very gradual manner with Egyptologists. Indeed, the approach has always been to place the user at the heart of the process. Forcing them immediately to use a method that they do not understand, nor master would only serve to discourage them, despite the promise of performance. The synergy sought between the researcher and his tool can only be achieved after a period of acculturation between experts in different fields, in very specific subjects. The emphasis was therefore placed initially on the quality of the experience that the tool can deliver, which is the only guarantee of its general adoption by the community, which then becomes ready to trust the capabilities of the computer technology to go further.

As far as VÉgA is concerned, the KBS is already structured in a functional manner. However, the acquisition method was still manual at the beginning, close to the traditional practices of Egyptologists, according to a top-down method that was comfortable for them because they could control all the steps and know the results that it allowed to produce. The editing interface, reserved for the publication committee in charge of recording the data, was strictly identical to the public consultation interface and each tab was filled in by hand, even if it meant recording the same information several times in several places. This practice, considered from a technical point of view as a source of errors, was preferred by Egyptologists, who were used to carry out tedious work in a conscientious manner, requiring numerous checks, as it ensures that they kept control of the data processed throughout the process. However, as the versions progressed, they realised that some redundant actions could easily be automated, without compromising the integrity of the scientific method. The work on V4 therefore focuses on the implementation of a bottom-up method, which should in turn allow the generation of data through capitalisation and inference.

Indeed, the objective of the V4 is to optimize interoperability between the tabs as much as possible and to establish the scientific rigour of the process by systematically justifying a lexeme by one or more sources. Thus, the first initiative was to integrate a new tab, the thesaurus, where all the sources processed and all their attributes (name, inventory number, type of source, dating, mode of writing, etc.) are recorded, so that it is no longer necessary to repeat these data from one field to the next, but rather to make it accessible each time it is needed. On the other hand, while the consultation interface has changed only slightly, the editing mode has been completely redesigned, with the information on a source becoming the condition for justifying a written form, not only in the catalogue, but also in the one shown under the heading in the general module. The creation of this catalogue of spellings also automatically completes a chronological frieze according to the dating of the sources used, giving an overview of the period during which, the word is used in the language. On the other hand, if the philologist is working on a specific source, the thesaurus becomes a new entry point into the database, through which he or she can directly consult the lexemes analysed in this source.

Finally, the second major innovation imagined for a future version is the integration of a catalogue of hieroglyphic signs, making it possible to activate the search in the dictionary directly by sign. Indeed, the ability to decipher hieroglyphs constitutes the frontier between the expert Egyptologist and the neophyte. Since research has been carried out mainly by transliteration so far, the tool is primarily intended for researchers who have already mastered the language. However, the hieroglyphic sign is the only entry point available to the public and the first barrier to be removed to make the tool accessible to all. A classification of the signs has already existed for a long time [

11] as has the standard system

Manuel de codage for the computer-encoding of hieroglyphs in textual processing software. This encoding system has been developed in 1984 by an international committee of Egyptologists [

21]. It is based on the Gardiner classification, with specific features of hieroglyphic writing such as the respective placement of individual signs in a sequence, its orientation, color and size. Thus, rather than inserting SVG images, the encoding of signs directly in the database allows the generation of interactive hieroglyphs in consultation, which again become a new access point to the database.

5. Opening Up to Other Fields

Reassessing the entirety of knowledge on the lexicon of ancient Egyptian today is already an ambitious project, but in its new structuring, a platform such as VÉgA is destined to expand to answer questions other than those concerning lexicography alone. This opening towards other domains can be done at two levels: within the infrastructure itself by welcoming new modules, but also by its interoperability with other databases and tools.

As we have seen above in the description of the ontology, studying a lexeme requires collecting data on several aspects of the language. A first idea would therefore be to exploit them fully and to enrich the range of possible queries to solve problems in other areas of linguistics: morphology, grammatology, semiology... 7

At the same time, new subjects of study can be integrated into the infrastructure to create thematic directories. Thus, a partnership was concluded with the University of Paris-Sorbonne (UMR 8167 ‘Orient & Méditerranée’) to integrate data from the Capéa database (Corpus et analyses prosopographiques en Egypte ancienne). Initially, it was designed as a tool dedicated exclusively to research in prosopography, i.e. the collation and analysis of titles worn by administrative, civil, military and religious personnel in Egyptian society, as well as the study of the individuals who bore them. As a title is made up of several words, the link with the VÉgA dictionary is obvious. However, the research challenges in prosopography are very different from those in lexicography, and new formats for title- and individual-specific notes had to be designed, as well as new interactions between the data.

Moreover, although this data is already structured within a FileMaker Pro database, it is only recorded and used by the researcher who initiated the project. This restricted access has conditioned the structuration of the database originally for an ultra-expert use, to answer only to precise problems, against the principles of digital humanities supported by the VÉgA programme. It is therefore not a question of simply integrating the data as it is, but of making the effort once again to understand the specific uses of prosopography to model the results, so that they are made accessible to prosopographers as well as to non-specialist Egyptologists and to a wider public.

On the other hand, with the multiplication of database projects in Egyptology, it is essential to encourage as much interoperability as possible between them to overcome the persistent problem of data dispersion. A single research centre cannot produce the entirety of knowledge in a field, and it is necessary to capitalize on external content to optimize the user experience, which always prefers to focus on the thread of its reflection. VÉgA has begun to take steps in this direction by connecting the dictionary with the Karnak project, 8 which aims to organize and make accessible all the textual documentation from the Karnak temples in Luxor. For each source processed in VÉgA from Karnak, a link on the KIU (Karnak Unique Identifier) allows direct access to the corresponding document on their database, presenting a UHD photo of the source, a transliteration and a complete bibliography. In return, each word of the transliteration on the Karnak project record indicates its VÉgA ID number. Links have also been made between VÉgA and another lexicographical platform, heir to the Berlin’s Wörterbuch des Ägyptische Sprache, the Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae.

By encouraging collaboration between researchers and research centres, cyberinfrastructures can only gain in performance, inscribing in time the knowledge produced by research while making it accessible to a wide public, beyond its specific field.

6. Knowledge Transfer

The last issue facing the VÉgA team is that of transferring knowledge to exclusively didactic tools, intended for a non-specialist public, to reduce the intermediaries between scientific results and cultural mediation. This can take the form of pedagogical tools for training, informative objects in museums or applications for touring sites.

A first experiment was attempted in 2016, on the exhibition “A l'école des scribes. Les écritures de l’Égypte ancienne” organized at the Henri Prades Archaeological Museum in Lattes (Hérault, France). Based on a piece of the exhibition, the lintel of Tjeti

9, an application has been developed to make its

facsimile interactive (

Figure 5). Presented on a 1:1 scale touch table, the hieroglyphic text was accompanied by a translation. The visitor could then select a sign and the VÉgA note of the word to which it belongs would open on the side. In this exhibition dedicated to writing, this allowed visitors to make the link between the hieroglyphic text and its translation, and thus to understand the mechanisms of this writing system that uses both phonograms and logograms.

This experience showed the public's undeniable interest in a specific topic, but above all their enthusiasm for being able to access a specialist tool within their reach. Such an application can only be adapted to other media, or even to other serious game experiences. The playful aspect of digital technology is undeniable, as its plasticity makes it possible, for the same set of data, to constantly adapt to various types of use and to free oneself from any exclusively linear progression, which is sometimes too rigid, particularly in the case of training. It has long been proven that manipulating a concrete object facilitates the learning of the concepts to which it is attached. In fact, digital technology has this fundamental capacity to make tangible data that would remain purely abstract as long as they are only printed in a book.

7. Conclusion

The VÉgA platform is thus presented as a cyberinfrastructure that aims to be public, sustainable and interoperable, supporting experimentation and encouraging collaboration between researchers, in accordance with the recommendations of the American Council for Learned Societies' 2006 manifesto. By combining scientific and computer knowledge with digital design expertise, the user experience is placed at the heart of the system to ensure that the tool - and the knowledge it conveys - is appropriated by all types of publics, with varying levels of knowledge.

Since the generalisation of digital technology in recent years, the Humanities has increasingly realised that the digitisation of paper documents alone is not enough to improve research practices and its valorisation, or at best its dissemination to the ever-smaller circle of the scientific community. At the other end of the chain, it is exploited for its essentially visual and immersive qualities with the public, encouraging their curiosity and interest to learn more, with better quality content.

Digital Humanities are defined by their capacity to combine in the same infrastructure the production of knowledge (research), its transmission (publications and teaching) and its dissemination (valorisation). Knowledge engineering methods and the creation of KBSs, which are more efficient than basic databases (SQL), thus provide new perspectives on the knowledge of ancient cultural heritage and its representation. In return, these results themselves become easily accessible to anyone with an interest in the subject, on an ongoing or ad hoc basis, as they are updated in real time.

The cultural centre founded around the Library of Alexandria in the third century BCE can be considered the world's first KBS, with its commitment to collecting, organising, preserving and transmitting knowledge to encourage the advancement of science. Moving from papyrus and clay tablets to microprocessors and digital tablets, we seek today to spread the benefits of this ambitious enterprise for intellectual enrichment, while preserving and sharing the memory of the Mouseion of antiquity.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

On the language of the ancient Egyptians, see [ 3]. On the hieroglyphic system itself, see [ 4, 5]. |

| 3 |

After the Arab conquest, the Egyptian language was perpetuated by Coptic, the liturgical language of the Egyptian Christians. |

| 4 |

Digitized by the Berlin Institute and now freely available, within the Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae ( https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de, Corpus issue 18, Web app version 2.1.5, 7/26/2023, ed. by Tonio Sebastian Richter & Daniel A. Werning on behalf of the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften and Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert & Peter Dils on behalf of the Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig [accessed: 9/10/2024]; https://aaew.bbaw.de/tla/index.html). |

| 5 |

The team is currently working on a new module for studying job titles (prosopography), which are themselves made up of a sequence of lexemes, but with their own problematics, cf. infra, ‘Opening up to other fields’. |

| 6 |

Intermediate phase of translation of an Egyptian text, in which the Egyptian phonemes (represented by hieroglyphic phonograms) are substituted into alphabetic characters, according to conventions specific to Egyptology. |

| 7 |

However, these new axes can only become relevant once the entire vocabulary has been processed. The dictionary is currently estimated to be completed by the end of 2025. |

| 8 |

CNRS - LabEx Archimede, ANR-11-LABX-0032-01, Programme ‘Investissement d'Avenir’ - USR 3172 - CFEETK / UMR 5140, Equipe ENiM; http://sith.huma-num.fr/karnak. |

| 9 |

Limestone fragment preserved in the Louvre Museum, Department of Egyptian Antiquities, AF 9460 [ 22] (p. 118-119). |

References

- Burdick, A.; Drucker, J; Lunenfeld, P; Presner, T; Schnapp, J. Digital_Humanities; MIT Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2012.

- Vial, St. Le tournant design des humanités numériques. Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication 2016, vol. 8. [CrossRef]

- Loprieno, A. Ancient Egyptian. A Linguistic Introduction; University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1995.

- Vernus, P. Les origines de l’écriture hiéroglyphique et l’Égypte ancienne. In Les origines de l’écriture; Alleton, V., Maniaczyk, R., Shaer, R., Vernus, P., Eds.; Le Pommier: Paris, France, 2012, pp. 113-166.

- Winand, J. Les hiéroglyphes égyptiens; PUF: Paris, France, 2013.

- Champollion, J.-Fr. Dictionnaire égyptien en écriture hiéroglyphique; Firmin-Didot Frères: Paris, France, 1841.

- Brugsch, H. Hieroglyphisch-Demotisches Wörterbuch; Hinrichs: Lepizig, Germany, 1867.

- Budge, E.A.W. An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary; J. Murray: London, United Kingdom, 1920.

- Champollion, J.-Fr. Grammaire égyptienne, ou Principes généraux de l’écriture sacrée égyptienne appliquée à la representation de la langue parlée; Firmin-Didot Frères: Paris, France, 1836.

- Erman, A. Ägyptische Grammatik; Reuther & Reichard: Berlin, Germany, 1894.

- Gardiner, A.H. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs; Clarendon Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 1927.

- Erman, A.; Grapow, H. Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache im Auftrage der Deutschen Akademien; Akademie-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1926-1961.

- Claes, W.; van Keer, E. Les ressources numériques pour l’égyptologie. Bibliotheca Orientalis 2014, Vol. 71 (3-4), 297-306.

- Lucarelli, R.; Robertson, J.A.; Vinson, St. Ancient Egypt, New Technology. The Present and Future of Computer Visualization, Virtual Reality and Other Digital Humanities in Egyptology; Harvard Egyptological Studies, Vol. 17; De Gruyter Brill: Berlin, Germany and Leiden, Netherlands, 2023. Available online: https://brill.com/edcollbook-oa/title/55882 (accessed 22 July 2025).

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.R.; Fensel, F. Knowledge Engineering: Principles and Methods, Data & Knowledge Engineering 1998, Vol. 25 (1-2), 161-197. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Kaliyar, R. Graph databases: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing, Communication & Automation, Greater Noida, India, 15-16 May 2015. [CrossRef]

- NoSQL Performance Benchmark 2018 – MongoDB, PostgreSQL, OrientDB, Neo4j and ArangoDB. Available online : https://www.arangodb.com/2018/02/nosql-performance-benchmark-2018-mongodb-postgresql-orientdb-neo4j-arangodb (accessed 22 July 2025).

- Jacques, E.; Solinski, S.; Ollagnon Cl.; Rinato, Y. La conception numérique, entre espace intime et monstration. A la recherche des intelligences collectives. In Intelligence Collective. Rencontres; Penalva, M., Ed.; Presse des Mines: Paris, France, 2006, pp.321-334.

- Cassier, Ch.; Chauveau, N.; Massiera, M.; Rouffet, Fr. VEgA, une plateforme numérique de recherches lexicographiques pour la connaissance et la diffusion de l’égyptien ancient. In Systèmes d’organisation des connaissances et humanités numériques. Actes du 10e colloque ISKO France 2015, 6 et 7 novembre 2015, Collège doctoral européen, Strasbourg; Chevry Pébayle, E., Ed.; ISTE edition: London, United Kingdom, 2017, pp 273-288.

- Benveniste, E.; Problèmes de linguistique générale I, Gallimard: Paris, France, 1966.

- Burman, J.; Grimal, N.; Hainsworth, M.; Hallof, J.; van der Plas, D. Inventaire des signes hiéroglyphiques en vue de leur saisie informatique, Institut de France: Paris, France, 1988.

- Bazin Rizzo, L.; Gasse, A.; Servajean, Fr. À l’école des scribes. Les écritures de l’Égypte ancienne; Cahiers de l'ENiM, Vol.15; SilvanaEditoriale and CENiM: Milan, Italy and Montpellier, France, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).