1. Introduction

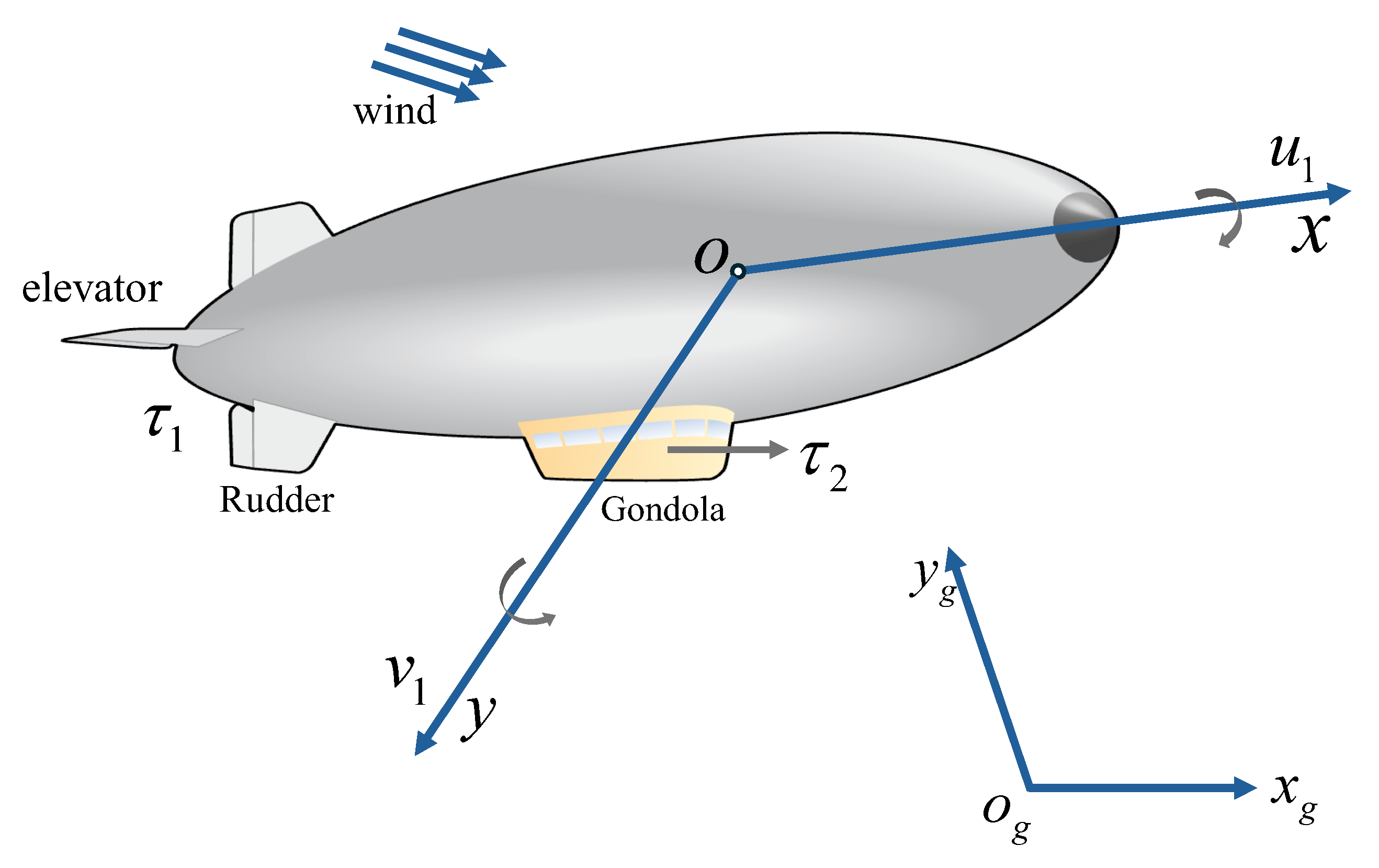

Unmanned airships are experiencing a resurgence in strategic interest for applications demanding long-endurance and high-altitude station-keeping, such as persistent surveillance, atmospheric sensing, and serving as high-altitude pseudo-satellites (HAPS) for telecommunications [

1,

2]. Their inherent energy efficiency and substantial payload capacity make them particularly suited for missions impractical for conventional fixed-wing or rotary-wing UAVs [

3]. However, realizing this potential is contingent upon developing highly reliable autonomous navigation systems. A cornerstone of this autonomy is path-following control, which requires the airship to converge to and maintain a predefined geometric path in the presence of significant and persistent operational challenges [

4].

The control of unmanned airships is a challenging problem, fundamentally complicated by a confluence of several interacting factors. One arises from the airship’s internal dynamics, which are characterized by large inertia, low damping, and highly coupled nonlinear behavior, rendering the vehicle inherently sluggish and difficult to stabilize [

5]. This inherent dynamic challenge is exacerbated by the operational environment, as operating at high altitudes exposes the vehicle to persistent and intense wind fields, whose wind velocity can be a significant fraction of the airship’s airspeed. Consequently, this elevates wind from a disturbance to a dominant and mission-critical factor demanding robust compensation [

6]. Compounding these challenges, many missions, such as area surveillance, require the airship to follow closed-loop and repetitive trajectories (e.g., racetrack patterns), often while satisfying strict state constraints on tracking error to ensure safety or sensor coverage. These paths introduce topological challenges for guidance systems, such as reference discontinuity, which are not encountered in simple point-to-point navigation [

7,

8]. Addressing these multifaceted challenges calls for an integrated guidance and control architecture that provides robustness, smooth actuation, topological consistency, and explicit constraint handling.

The LOS guidance law remains a well-established and widely adopted method, valued for its geometric clarity and low computational overhead [

9]. It operates by directing the vehicle towards a virtual target or look-ahead point situated on the desired path. However, classical LOS guidance with a fixed look-ahead distance suffers from an inherent trade-off: a small distance yields aggressive tracking but risks oscillations, while a large distance ensures smoothness at the cost of sluggish response. More importantly, the LOS guidance law is susceptible to steady-state cross-track errors when subjected to persistent lateral disturbances, such as crosswind, regardless of whether the look-ahead distance is small or large [

10].

Several extensions of the LOS framework have been developed to improve robustness and tracking accuracy. Integral LOS (ILOS) augments the classical law with an integral term that compensates for constant environmental forces, thereby removing steady-state cross-track errors [

11,

12]. Subsequent work has introduced adaptive LOS schemes in which the look-ahead distance is adjusted online based on the cross-track error [

13]. Although these approaches improve tracking performance on open or piece-wise continuous paths, they share a common and unaddressed limitation that they fail to handle the topological discontinuity inherent in closed-loop trajectories. When the look-ahead point crosses the path’s seam, either at the closure point of a loop (e.g., from the end waypoint back to the start) or at a segment transition (e.g., from a straight section into a turning arc), the path index undergoes an abrupt jump. This discrete index-jump phenomenon causes a discontinuous change in the commanded heading, which can result in control signal saturation and degraded tracking performance, an important concern for persistent loitering missions [

14].

At the control layer, Sliding Mode Control (SMC) has been extensively studied for its robustness against matched uncertainties and external disturbances [

15]. Its practical application, however, is often hindered by the chattering phenomenon—high-frequency oscillations in the control signal caused by the discontinuous switching law, which may excite unmodeled dynamics and accelerate actuator wear [

16,

17]. Research to mitigate this issue has primarily followed two paths. The first involves higher-order SMC methods, notably the Super-Twisting Algorithm (STA) [

18,

19]. By shifting the discontinuity to a higher derivative of the control signal, STA generates a continuous control action effectively suppressing chattering while preserving the finite-time convergence and robustness properties of conventional SMC [

20]. The second path aims to enhance convergence speed through TSMC and its nonsingular variants [

21]. Unlike conventional SMC, which offers asymptotic stability, TSMC ensures finite-time convergence of the system states, a property often required in fast-response applications [

22]. Although the combination of STA and TSMC provides a practical means for achieving low-chatter, finite-time control [

23], these methods remain fundamentally reactive. Their efficacy relies on control gains being large enough to dominate the worst-case disturbance bound [

24]. For an airship facing large and sustained wind forces, this can result in excessive control effort and may not be the most efficient strategy. These considerations indicate the need for a proactive mechanism capable of estimating and compensating for the dominant portion of the disturbance, thereby reducing the reliance on high-gain robust control.

To enable proactive disturbance compensation, the ESO has emerged as a compelling paradigm [

25]. The core concept of an ESO is to aggregate all sources of uncertainty—including external disturbances, unmodeled dynamics, and parametric variations—into a single total disturbance variable [

26]. This augmented variable is then treated as an extended state of the system, which the observer estimates in real-time. The notable advantage of the ESO is its weak dependence on detailed system modeling. The ESO requires only coarse structural knowledge of the system’s mathematical model while providing a direct estimate of the total disturbance, which can then be actively compensated in the control loop. These ESO-based designs have been applied across various aerospace platforms, where they have demonstrated improved disturbance rejection and robustness [

27].

Despite these individual advances, an important gap remains in integrating these developments into a cohesive framework. Advanced guidance laws, finite-time robust controllers, and disturbance observers have been developed largely as standalone components, and a framework that integrates all three in a unified manner is still lacking. In addition, existing approaches rarely offer formal guarantees on state-constraint bounds satisfaction—such as bounds on tracking error—which are essential for safe operation near obstacles and for maintaining sensor coverage[

28,

29]. Achieving such integration is nontrivial, as it requires ensuring the stability of a tightly coupled system in which the observer, guidance law, and controller interact dynamically while state constraint bounds must be enforced without relying on excessively high feedback gains.

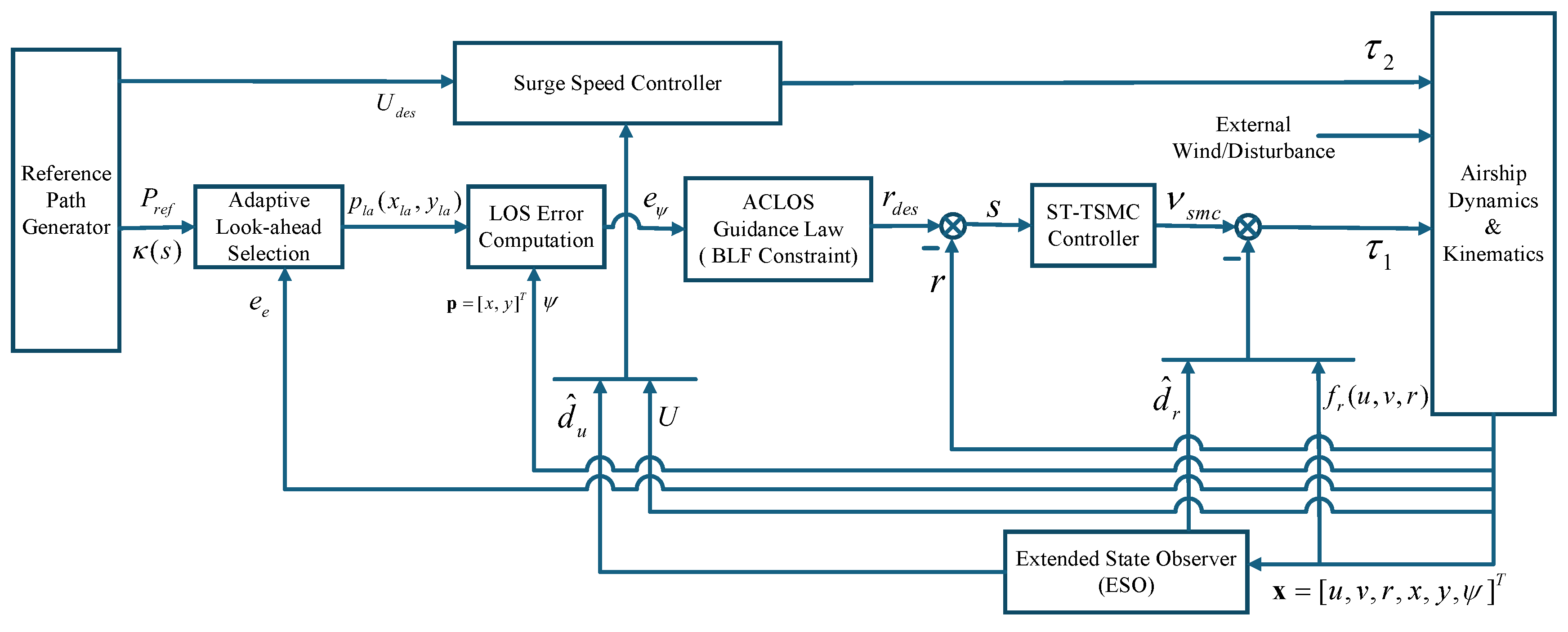

To address the aforementioned limitations and bridge the identified research gaps, this paper develops a unified guidance and control framework designed to enhance disturbance resilience for unmanned airships executing closed-loop path following missions in uncertain environments. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

A Curvature-Aware Adaptive LOS Guidance Law: A novel nonlinear LOS guidance law is proposed that dynamically adapts the look-ahead distance based on both local path curvature and cross-track error. This strategy is coupled with an index-increment mechanism that explicitly suppresses the index-jump phenomenon, guaranteeing a smooth and continuous LOS angle command even across the seam of closed-loop trajectories.

A Unified guidance and control Synthesis with BLF Constraint Guarantee: We develop a unified guidance and control synthesis that rigorously enforces state constraints. A BLF is constructed on the LOS heading error, guaranteeing that this guidance error remains within predefined bounds for all time, thus ensuring stable and predictable controller behavior.

A Finite-Time, Disturbance-Rejecting ST-TSMC Law: A robust inner-loop controller is developed by integrating an ESO with an ST-TSMC law. The ESO estimates and compensates for lumped physical disturbances and complex kinematic disturbances arising from the LOS geometry. The ST-TSMC law then drives the yaw-rate tracking error to a small residual set in finite time, ensuring chattering-free, robust tracking of the BLF-constrained guidance command.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 details the airship dynamic model and formulates the path-following control problem.

Section 3 presents the geometric representation of the reference path and derives the associated error kinematics.

Section 4 constructively derives the integrated guidance and control framework, detailing the ESO, the BLF-SMC synthesis, and the guidance law.

Section 5 presents the formal stability analysis, culminating in the unified stability theorem.

Section 6 reports simulation studies—together with comparative and robustness evaluations—that assess the performance of the proposed framework. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses potential avenues for future research.

5. Stability Analysis

The overall closed-loop stability is examined through the composite Lyapunov function

, constructed as the sum of the yaw-channel (guidance and inner-loop) and surge-channel contributions:

where

is a weighting coefficient,

denotes the Lyapunov function of the surge channel, and

corresponds to the composite Lyapunov function of the cascaded yaw channel. The latter consists of the barrier Lyapunov term for the outer-loop kinematic error

and the quadratic energy of the inner-loop sliding surface

s:

The longitudinal-channel Lyapunov function is given in

Section 4.4 as

. The composite Lyapunov function

is positive definite and radially unbounded. The barrier term satisfies

as

, ensuring forward invariance of the constrained set. The time derivative of

is

The surgechannel stability follows from the Lyapunov derivative

. Using the result of

Section 4.4 (Eq.

51), this derivative admits the bound:

where

is uniformly bounded,

. Applying Young’s inequality to the cross term

yields:

where

. Selecting the gains such that

and

ensures that

is negative semi-definite outside a compact neighborhood of the origin. Consequently, the surge sliding surface

remains Uniformly Ultimately Bounded. The inner-loop stability is analyzed via

. From the synthesis in

Section 4.3, the sliding dynamics are (Eq.

39):

The lumped disturbance is given by

. With Assumption 1, the model disturbance satisfies

, and from

Section 4.2 the LOS kinematic rate

is uniformly bounded as

. Hence, the total disturbance admits the bound:

where

denotes the finite but unknown disturbance bound. Substituting the ST-TSMC law (Eq.

40) into the Lyapunov derivative yields:

To establish the negativity of , the analysis proceeds by considering two cases:

In both cases,

is negative definite outside a small residual set, implying that

reaches a compact neighborhood of the origin

in finite time. Let this ultimate bound be denoted by

for all

. The stability of the outer-loop error

is assessed by analyzing the BLF derivative

. Using the expression derived in Eq.

41, we have:

The BLF derivative is influenced by two bounded disturbances: the residual sliding surface error

, satisfying

, and the kinematic disturbance

, satisfying

. Defining

, the derivative becomes:

Applying Young’s inequality to the disturbance terms yields the following bounds:

where

are design constants. Using these bounds, the BLF derivative satisfies:

where

collects the constant terms generated by the Young-based bounds. Substituting

gives:

After factoring out the common term

(i.e.,

), the derivative satisfies:

Ensuring the non-positivity of the derivative in (

69) requires the coefficient

to remain strictly positive, which is equivalent to the condition

. This requirement is met provided that

does not approach the barrier boundary

. Moreover, when

is sufficiently large, the quadratic stabilizing term

dominates the bounded disturbance contribution

, ensuring that

remains negative semi-definite outside a compact set. Consequently, the LOS heading error

is uniformly ultimately bounded. By aggregating the bounds obtained in (

57), (

60), and (

69), the composite Lyapunov derivative admits the inequality

where

is a positive semi-definite function of the closed-loop error states, and

,

, and

are non-negative constants determined by the disturbance bounds. The inequality implies that

is negative semi-definite outside a compact neighborhood of the origin, which establishes the uniform ultimate boundedness of

, and

.

Since the BLF satisfies as , violation of the heading-error constraint would imply unbounded growth of . However, is finite because the initial condition satisfies , and has been shown to be negative outside a compact residual set. Hence remains uniformly bounded for all , which excludes the possibility of diverging. Consequently, the LOS heading error constraint is enforced for all time.

Theorem 1.

Consider the unmanned airship system (1)–(3), subject to bounded lumped disturbances (Assumption 1) and bounded LOS kinematic disturbance . Given the ESO-compensated control laws (43) and (52), and the adaptive guidance law (Section 3.1), if the control gains are selected to satisfy:

then the closed-loop system is Uniformly Ultimately Bounded (UUB). Furthermore:

-

1.

(Constraint Satisfaction) The BLF guarantees the forward invariance of the feasible set for the LOS heading error, strictly enforcing for all .

-

2.

(Finite-Time UUB) The inner-loop sliding surfaces () converge in finite time to a small residual set around the origin.

-

3.

(UUB of States) The LOS heading error converges to a small residual set whose size is dependent on the bounds and . The cross-track error is consequently UUB by the properties of the adaptive LOS guidance law.

Proof. The proof follows by analyzing the composite Lyapunov function

defined in (

53). Its derivative is bounded as shown in (

70), yielding

. Under the gain conditions in (

71),

is negative semi-definite outside a compact set determined by the bounded disturbances, which ensures the Uniform Ultimate Boundedness (UUB) of all closed-loop error states. Specifically, the analysis in

Section 5 establishes both the finite-time UUB of the sliding variable

s and the UUB of the heading-error state

. Moreover, because the barrier Lyapunov function satisfies

as

, constraint violation would imply unbounded growth of

. Since

is finite and

guarantees uniform boundedness of

, the barrier growth condition cannot be triggered, thereby enforcing

for all

. Finally, convergence of the cross-track error

follows from the convergence of

through the geometry of the LOS guidance law [

30]. □

6. Simulation Results and Analysis

To assess the performance, robustness, and practical relevance of the proposed unified ACLOS and ST-TSMC guidance and control framework, numerical simulations were carried out in MATLAB/Simulink. The simulation environment is based on the 3-DOF airship model described in

Section 2, with nominal parameters taken from [

9] and summarized in

Table 1. The controller is evaluated under wind and measurement-noise conditions representative of realistic operating environments. The reference trajectory is the racetrack path introduced in

Section 3, comprising both straight (

) and high-curvature segments. To emulate modeling mismatch, substantial parametric perturbations (e.g., +30% in inertia and

in damping) are imposed as specified in

Table 1. In addition, the system is exposed to two concurrent external disturbances: a steady crosswind of 4 m/s at

with respect to the ERF and stochastic, zero-mean Gaussian noise injected into the force and torque channels.

The full guidance control architecture comprising the CALOS guidance law, the ESO-based disturbance compensation and ST-TSMC controller, was implemented in accordance with the stability conditions established in the preceding sections. All controller gains, sliding-mode parameters, ESO bandwidths, and CALOS curvature-adaptation coefficients were tuned to satisfy the theoretical requirements while ensuring numerical robustness. To avoid numerical stiffness arising from large initial path-following errors, the BLF-based corrective term was gradually activated using a smooth scheduling function , increasing linearly from 0 to within the activation window (with , , and ). Standard anti-windup protection was incorporated by constraining the integrator states and whenever the corresponding control inputs or reached their saturation limits. This implementation ensures that the proposed framework operates within its theoretical design envelope under all simulated operating conditions.

The comparative validation of planar trajectories in

Figure 3 reveals the difference in tracking fidelity between the proposed framework and the baselines. The simulation is conducted under challenging conditions, including a persistent 4 m/s crosswind and the parametric uncertainties detailed in

Table 1. The superior performance of the proposed ACLOS+ST-TSMC controller (black) is immediately evident. The trajectory adheres almost indistinguishably to the reference path (dashed red) in both straight-line and high-curvature segments. This high-fidelity tracking is a direct result of the framework’s synergistic design: the ESO (embedded within the controller) actively estimates and compensates for the lateral wind forces in real-time. This active cancellation prevents the large, persistent cross-track errors seen in the baselines. In stark contrast, both the conventional ATSMC (blue) and ADRC (cyan) controllers demonstrate significant performance degradation. Lacking a sufficiently robust disturbance estimation and rejection mechanism, they are unable to counteract the persistent lateral wind, resulting in a substantial steady-state drift. Furthermore, the magnified inset clarifies a second performance gap: while the baseline controllers diverge, the proposed ACLOS+ST-TSMC framework maintains precision. This validates the effectiveness of the ST-TSMC component in handling coupled nonlinear dynamics, all while the ACLOS guidance law (which embeds the BLF) ensures the core LOS heading error (

) is kept within its prescribed bounds.

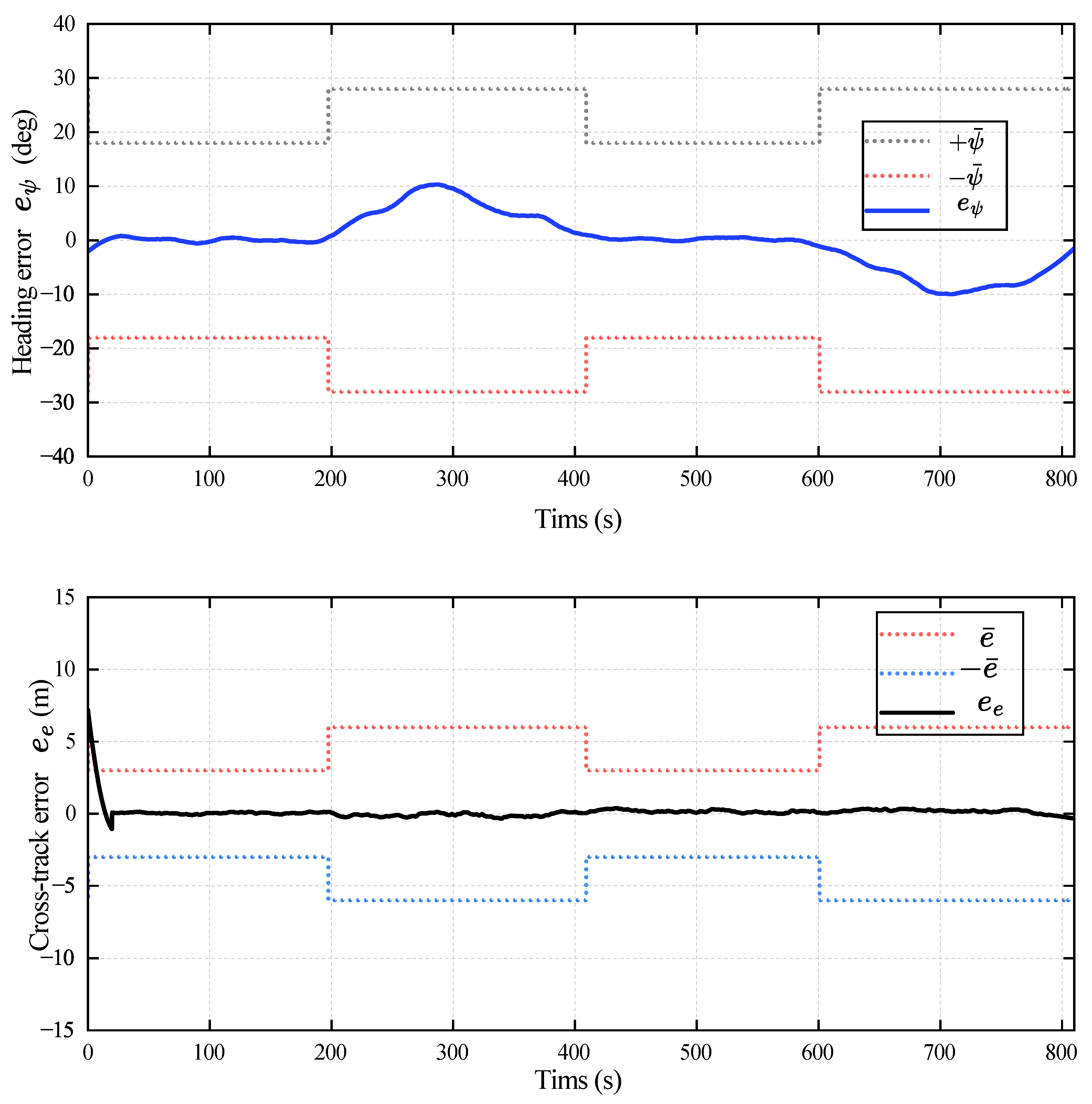

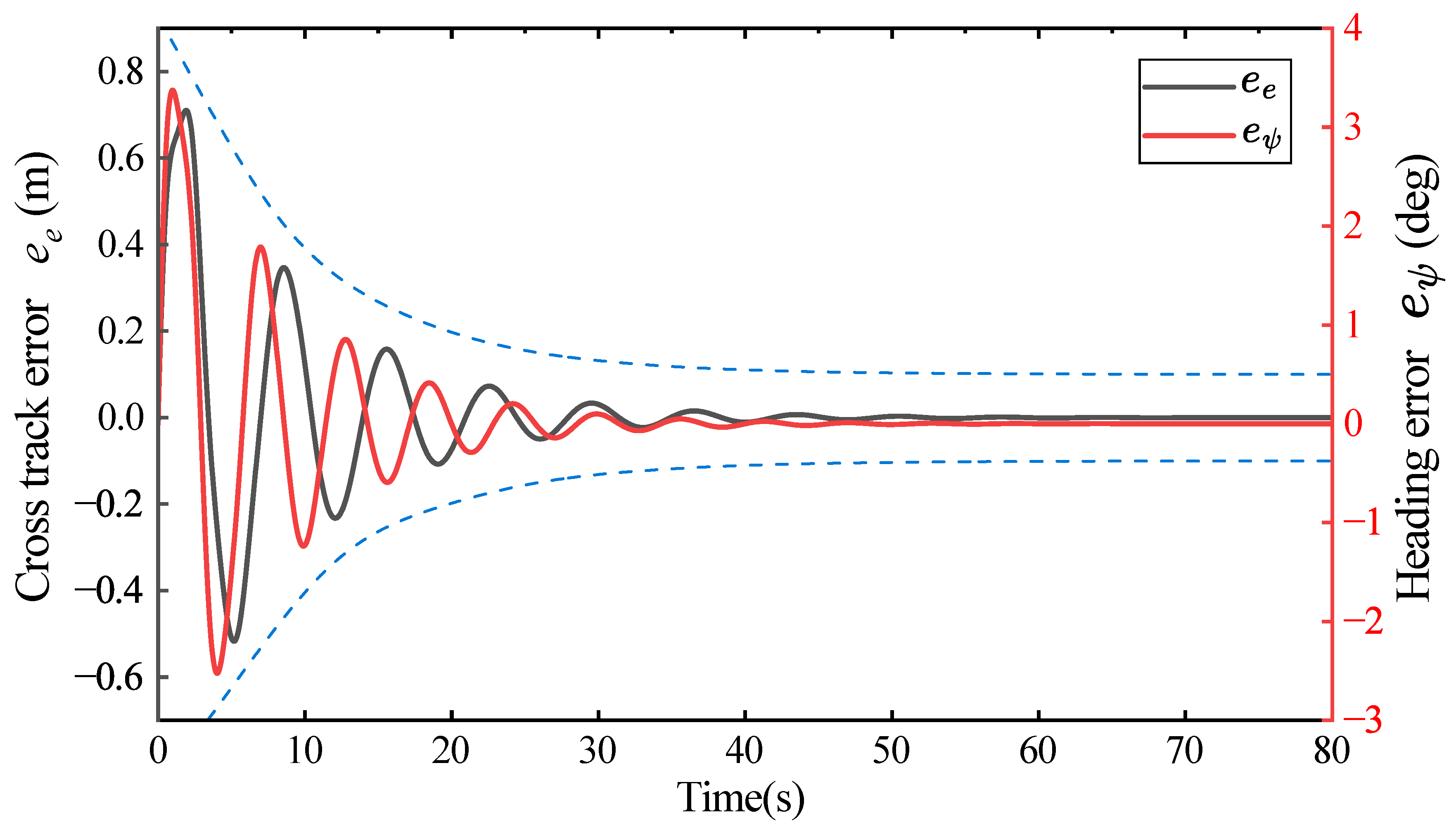

Moving beyond the trajectory-level comparison, the error time histories in

Figure 4 offer direct evidence of the constraint-aware behavior of the proposed control framework. The upper panel demonstrates that the LOS heading error

decays rapidly and remains strictly within its prescribed, time-varying bounds (

, dashed red) throughout the simulation. This behavior follows directly from the Barrier Lyapunov Function

constructed in

Section 4.3 in Eq.

32, whose divergence as

guarantees forward invariance of the admissible set. The lower panel illustrates a corresponding effect on the lateral deviation

, which also remains confined within its adaptive limits (

, dashed red). Unlike the heading error constraint, this bound is not enforced by the BLF itself; instead, it arises indirectly from the ACLOS guidance law in

Section 3.1. By ensuring that the steering error

is consistently regulated within its safe region, the guidance logic maintains the airship on a feasible interception geometry, leading to uniformly bounded lateral deviation. The adaptive nature of the constraint envelopes is clearly visible: the limits

relax during high-curvature segments (e.g.,

–300 s) to

, and tighten during straight segments (e.g.,

–600 s) to

to promote high-accuracy tracking. Importantly, both error signals converge smoothly without chattering, reflecting the ability of the ST-TSMC law to generate continuous, well-damped control action even under varying curvature and disturbance conditions.

The lower panel of

Figure 4 illustrates the consequence of this guaranteed guidance stability on the lateral cross-track error

. As shown,

(solid black) also remains uniformly contained within its adaptive constraint bounds

without overshoot. This lateral constraint satisfaction is not a direct result of the BLF. Rather, it is an indirect, geometric consequence of the ACLOS guidance law (

Section 3.1): by strictly enforcing the LOS heading error (

) within its bounds (as shown in the upper panel), the BLF ensures the guidance law is always stable and pointing the airship toward a valid intercept trajectory. This stable "steering" action, in turn, guarantees that the lateral error

is also driven to and held within a small, bounded region. The smoothness of both error trajectories, free from chattering or rapid switching, further confirms the effectiveness of the ST-TSMC component (Eq.

40) in the inner loop. Together, this demonstrates the framework’s synergistic design: the BLF-constrained ACLOS law provides a stable and continuous reference, while the ST-TSMC law robustly tracks it, resulting in constraint-consistent performance for both the core guidance error (

) and the resulting lateral error (

).

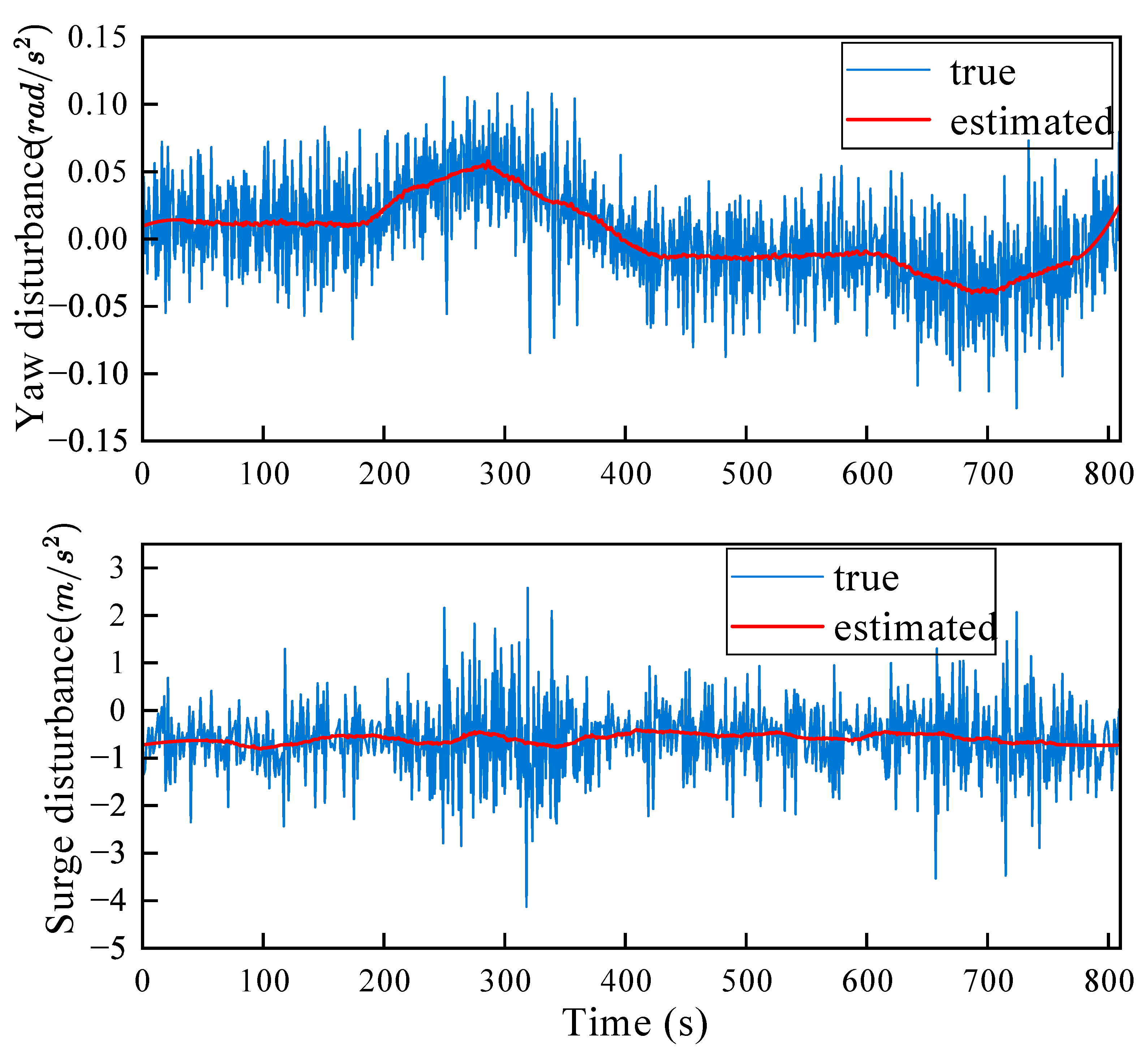

The performance of the ESO is depicted in

Figure 5. Both estimated disturbances

and

rapidly converge to the true lumped uncertainties in less than 2 s, demonstrating the observer’s capability to capture unmodeled dynamics and aerodynamic couplings. The bounded estimation errors satisfy

and

, in accordance with the theoretical derivations in

Section 4.1. This real-time compensation effectively suppresses external perturbations and prevents bias accumulation in both the yaw and surge loops. The resulting actuator commands,

and

, are presented in

Figure 6. Both signals remain continuous and well within typical saturation limits, confirming that the ST-TSMC law (Eq.

40) successfully avoids the high-frequency chattering endemic to conventional sliding-mode control. The variation in the yaw torque

(e.g., during the high-curvature turn

–300 s) is smooth and continuous. This demonstrates the controller’s robust response to the time-varying guidance command

(from the ACLOS law) and its successful compensation of the associated kinematic disturbance

. The surge control

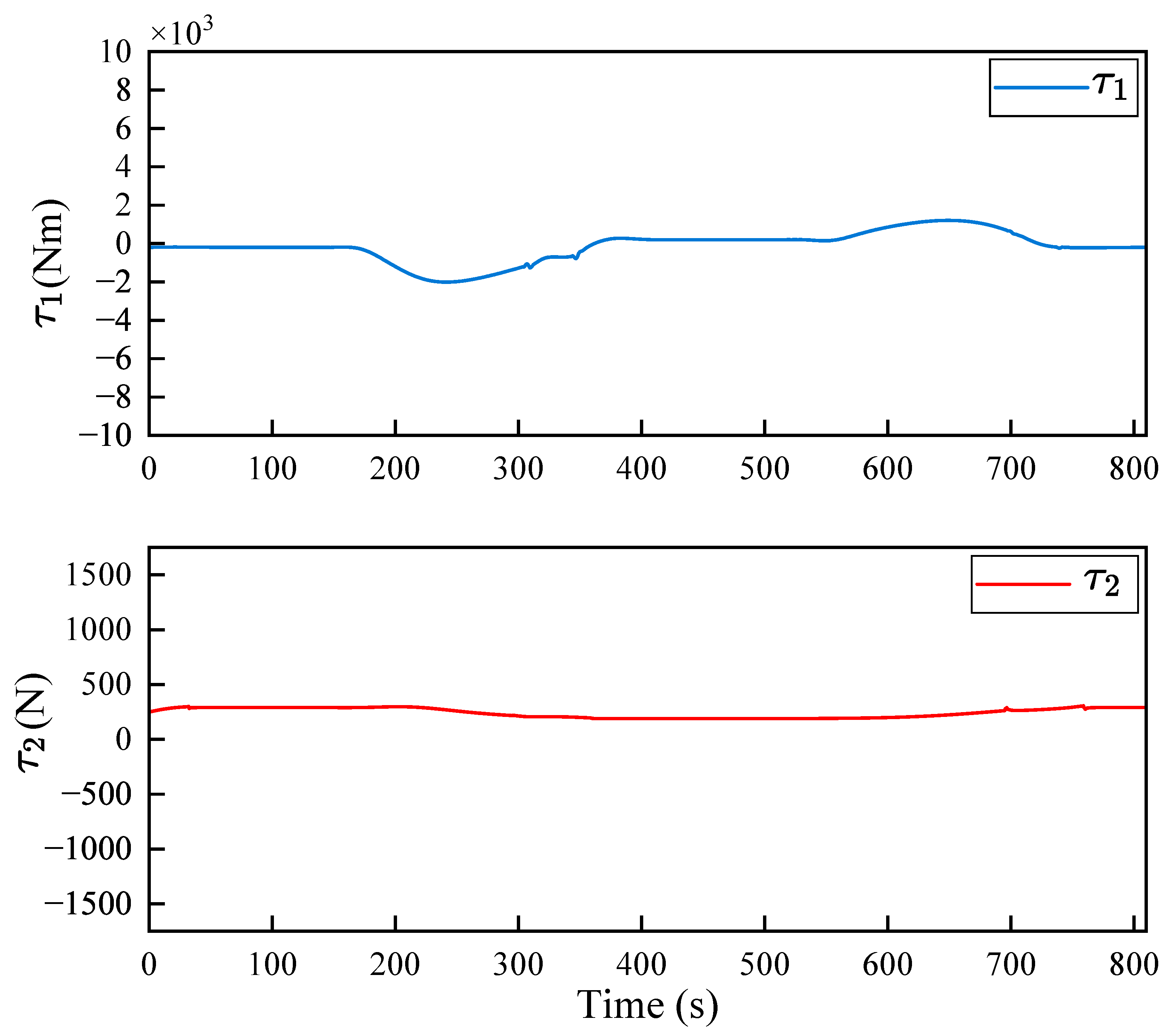

also shows stable behavior with negligible oscillation, confirming the effective disturbance rejection of the ESO-based compensation in the longitudinal channel.

The robustness of the proposed control architecture was further assessed under a demanding parametric–uncertainty scenario, as illustrated in

Figure 7. In this test, substantial and simultaneous perturbations were introduced by increasing all mass and inertia parameters (

) by

while reducing all damping coefficients (

) by

, without retuning any controller gains. These perturbations generate a pronounced transient response and represent a level of model mismatch that typically destabilizes nonlinear airship controllers. Despite this, the resulting error trajectories demonstrate that the closed-loop system remains stable and well regulated. Both the lateral deviation

and the LOS heading error

exhibit smooth convergence and remain strictly confined within their adaptive constraint envelopes throughout the simulation. This invariance property is particularly significant, as it confirms that the barrier Lyapunov formulation continues to enforce the feasible set for the guidance error even under large structural uncertainty. Consequently, the curvature-aware LOS mechanism retains its ability to regulate the lateral motion, indicating that the guidance and control components function cohesively under severe uncertainty and validating the resilience of the integrated design.

Table 2 provides the quantitative summary for the preceding robustness tests, correlating with the qualitative findings in

Figure 7 for both Test 1 and

Figure 8 Test 2. The data allows for an analysis of the controller’s performance-cost trade-off. Compared to the nominal case (RMS

m), the severe parameter perturbation in test 1 increased the lateral error by 12% to 1.76 m. More significantly, the relative crosswind scenario in test 2 was evaluated, wherein applying a 3 m/s mean wind—a persistent disturbance representing a significant fraction of the vehicle’s nominal airspeed, thereby inducing a continuous yaw moment—increased the lateral error by 17% to 1.83 m. The analysis of control effort, quantified by the control variance

, reveals the cost of achieving this performance. The data reveals that this tracking integrity was achieved with an increase in control effort, with 7% in test 1 and 10% in test 2. This minimal increase confirms that the controller does not resort to brute force high-gain feedback, which would have caused

to increase dramatically. Instead, this consequence confirms that the ESO is effectively estimating and canceling the bulk of the lumped disturbance for both parametric and external, allowing the ST-TSMC component to operate with smooth, low-variance control effort.

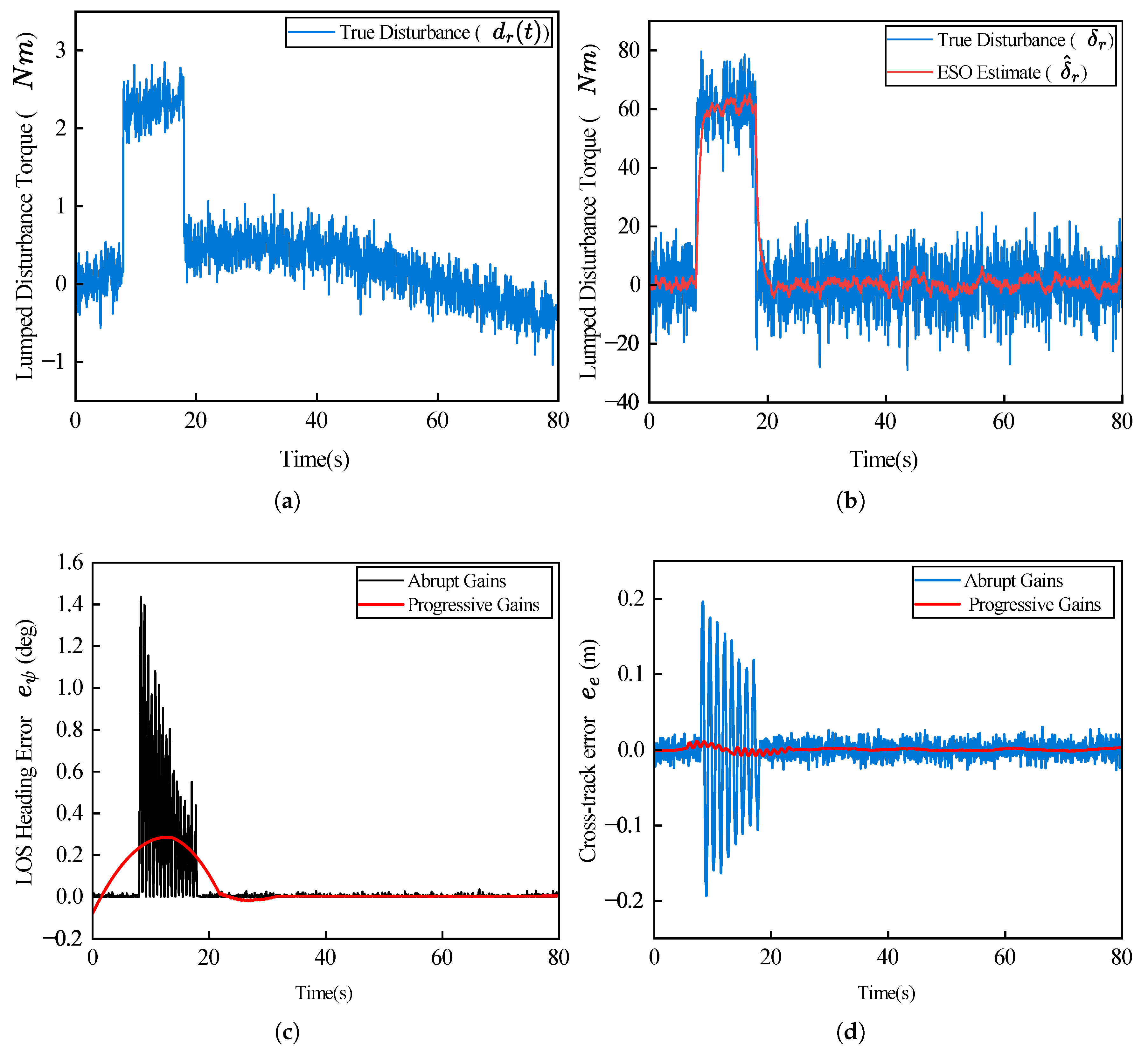

Figure 8 provides a detailed assessment of the closed-loop response, with emphasis on the disturbance-rejection and transient-handling mechanisms. Panel (a) shows the exogenous lumped disturbance torque

, consisting of a 60 N·m step input superimposed with broadband turbulent fluctuations, constructed to emulate demanding aerodynamic loading conditions on the coupled surge–yaw dynamics. The performance of the Extended State Observer is illustrated in Panel (b), where the estimated disturbance

(red) closely matches the true disturbance

(blue) with minimal phase delay (approximately 2 s). This accurate real-time reconstruction is essential, as it enables the control law to compensate for the dominant disturbance component through the feedforward channel. The resulting reduction in feedback burden suppresses excessive control activity, mitigates potential chattering, and decreases mechanical loading on the actuators.

Panels (c) and (d) examine the closed-loop response during system initialization and contrast the proposed Progressive Gain Scheduling (PGS) mechanism with a conventional abrupt gain activation. When the full guidance gains () are applied instantaneously at (black and blue traces), the large initial tracking error excites high-frequency components of the coupled surge–yaw dynamics, producing pronounced oscillatory transients in both the LOS heading error (panel c) and the lateral cross-track error (panel d). These transients can drive the actuators into saturation and jeopardize stability during the takeoff phase. In contrast, the PGS strategy (red traces), which gradually increases the controller authority over a short activation interval, effectively suppresses these oscillatory modes. As shown in the plots, both and exhibit smooth, monotonic convergence without overshoot. This behavior underscores a key structural advantage of the overall architecture: while the ST-TSMC law provides the required robustness and asymptotic accuracy, the PGS mechanism regulates the transient geometry to maintain safe, non-oscillatory evolution of the error states during the critical transition from initialization to steady path-following.

To quantify the individual contributions of the major architectural components, a comparative benchmarking study was conducted, with results summarized in

Table 3. The progression across the three controllers isolates the functional roles of disturbance estimation, nonlinear guidance shaping, and constraint enforcement. The Conventional ATSMC controller provides the baseline. Without any mechanism for disturbance compensation, it is unable to suppress the persistent crosswind, leading to pronounced steady-state deviations (RMS

m, RMS

). Its purely reactive sliding-mode action also demands the highest peak yaw torque (max

N·m), reflecting the controller’s need to counteract the disturbance through aggressive switching. Introducing the ESO markedly improves performance. By providing real-time estimates of the wind-induced lumped disturbances, the ESO–SMC controller eliminates the steady-state drift and reduces the RMS lateral and heading errors by 38% and 34%, respectively (to 2.41 m and

). This improvement demonstrates that active disturbance rejection addresses the primary source of chronic tracking bias that limits the baseline controller. The unified ACLOS + ST-TSMC framework achieves the highest overall performance. Beyond inheriting the disturbance rejection capability of the ESO, the curvature-aware LOS guidance with its embedded BLF ensures that the heading error

evolves strictly within its admissible region. This geometric constraint shaping directly translates into improved lateral error regulation, reducing RMS

to 1.57 m (a 59% improvement over ATSMC) and RMS

to

(a 58% improvement). Notably, this enhancement is achieved with the lowest control effort (max

N·m). This outcome reinforces a central principle of the proposed architecture: by combining disturbance prediction with constraint-aware guidance shaping, the controller avoids the need for excessive reactive authority, yielding smoother actuator behavior and superior path-following accuracy.

7. Conclusions

This paper addressed the problem of constraint-aware path-following for unmanned airships operating in uncertain wind fields and under parametric uncertainties. In this setting, maintaining coherent guidance–control coordination becomes challenging due to abrupt reference updates, which arise from the geometrically heterogeneous nature of the closed-loop trajectory. To cope with these challenges, this work develops a unified guidance–control framework that couples a curvature-aware adaptive LOS guidance law with an ESO-enhanced super-twisting terminal sliding-mode controller. Instead of treating guidance and control as separate functional layers, the proposed architecture enables the guidance law to generate a smooth, continuous LOS angle command (), while the controller compensates both physical disturbances and complex kinematic uncertainties in finite time. This coupling mechanism ensures both trajectory fidelity and control robustness, and additionally suppresses chattering effects commonly observed in high-gain sliding-mode implementations. The resulting framework demonstrates improved tracking precision under significant external disturbances, offering a systematic approach that is directly applicable to real-time flight scenarios.

The introduced curvature-aware adaptive LOS strategy resolves the long-standing index-jump discontinuity challenge in closed-loop trajectories by adaptively regulating the look-ahead distance () based on both path curvature and lateral deviation. This results in a continuously differentiable guidance reference () even at the path seam... On the control side, the ESO-assisted ST-TSMC law jointly provides (i) active rejection of both physical disturbances and kinematic disturbances (), (ii) finite-time tracking stability for the inner loop, and (iii) smoothened control effort, thereby significantly reducing the gain requirement and control oscillations typically associated with higher-order sliding-mode control alone.

To ensure constraint satisfaction on the LOS heading error () throughout the maneuvering process, a BLF was incorporated into the guidance and control synthesis. The BLF does not function merely as an auxiliary shaping term; rather, it guarantees forward invariance of the admissible guidance error set () without inducing stiffness in the closed-loop response, especially during curvature transitions. The stability of the overall system was established through a constructive Lyapunov analysis, which led to explicit gain conditions ensuring Uniform Ultimate Boundedness (UUB) of all closed-loop signals. Simulation studies demonstrated that, under crosswind disturbances up to 4 m/s and 20–30% parameter perturbations, the proposed framework reduced lateral error RMS by approximately 35% and control input variation by 40–50% compared with both ADRC and conventional ST-SMC baselines, while strictly maintaining state-constraint feasibility.

Future work will extend the framework to full 6-DOF airship models with three-dimensional aerodynamic effects and investigate the co-design of ESO bandwidth and sliding-mode homogeneity coefficients for guaranteed fixed-time convergence under actuator limits.