Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

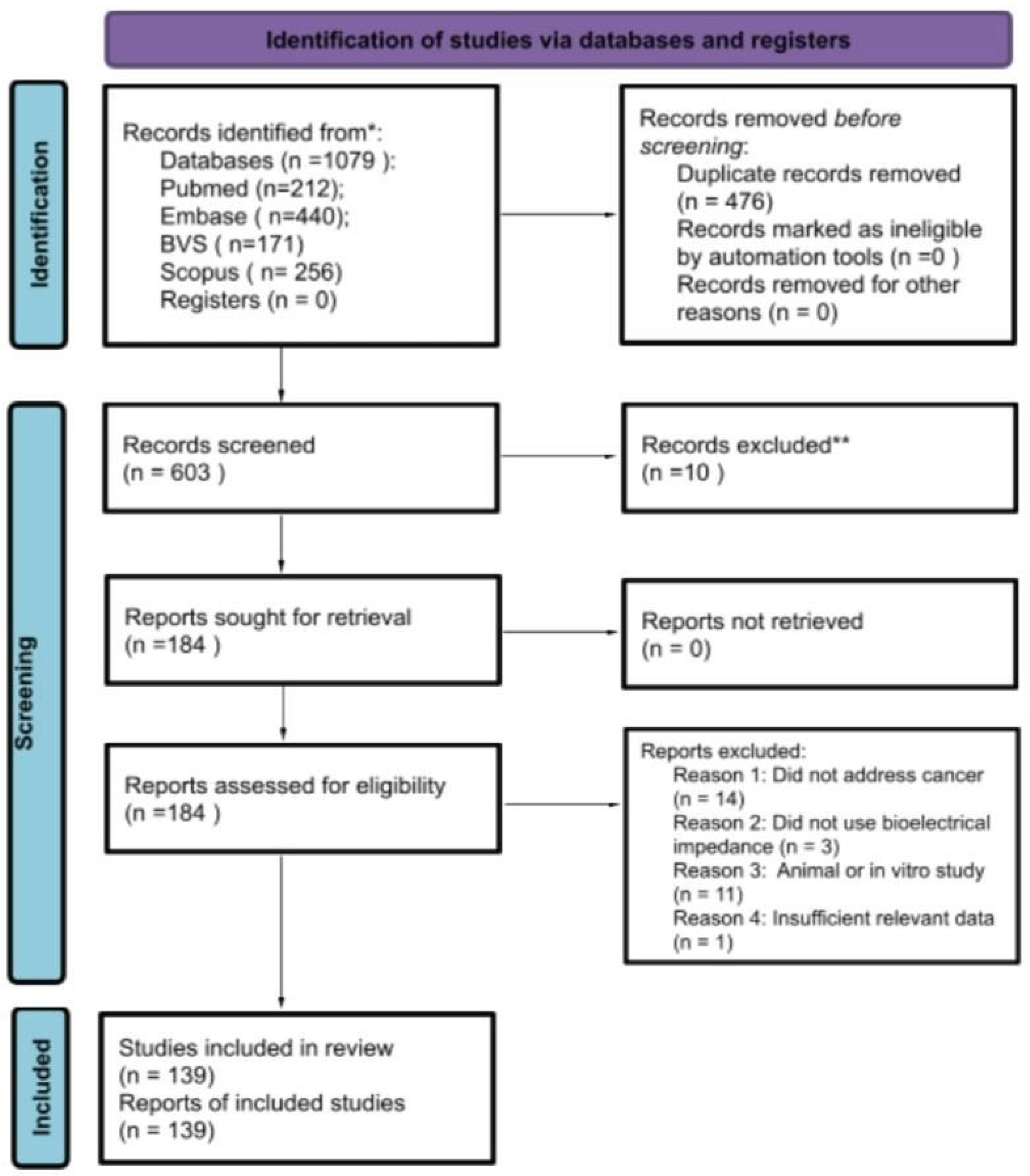

Methods

Study Deesign

Eligibility Criteria

Search, Screening, and Selection Process

Data Extraction and Analysis

Quality Appraisal

Synthesis of Results

Results

| Author (Year) | Sample/Context | Aims | Study Design | Conclusions |

| Malecka-Massalska et al. (2012) | 56 participants (28 with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and 28 sex-, age-, and BMI-matched controls). | To evaluate bioelectrical impedance vector patterns in patients with head and neck cancer before treatment. | Cross-sectional, case–control study. | Cancer patients showed vectors indicative of poorer cell integrity, lower body cell mass, and signs of dehydration; BIVA may support preoperative planning. |

| Cardoso et al. (2017) | 208 women undergoing surgery for gynecologic cancer (cervical and endometrial) between January and December 2015; | objective: to evaluate the applicability of BIA for nutritional status and surgical complications; | Prospective cohort | Lower PA in endometrial cancer and in poorer nutritional status (PG-SGA B or C); PA below the 25th percentile increased the risk of complications; BIVA indicated nutritional and hydration changes. |

| Malecka-Massalska et al. (2014) | 134 men (67 with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and 67 healthy controls matched by sex, age, and BMI) | Compare BIVA vectors in cancer patients vs. controls | Comparative observational study | Vectors shifted in cancer patients (R/H ↑ and Xc/H ↓), indicating worse nutritional and hydration status; no functional assessment or clinical outcomes evaluated. |

| Paiva et al. (2010) | 195 cancer patients evaluated before first chemotherapy | Assess the prognostic value of SPA for survival in oncology patients | Prospective cohort | SPA < −1.65 associated with significantly lower survival; higher mortality rate (RR = 2.35); risk of death increased progressively as SPA decreased. |

| – (2012, BEAM Study Group) | Patients with glioblastoma multiforme followed for up to 1 year (n not reported) | Test the effectiveness of BIA as a clinical tool for nutritional and prognostic assessment | Pilot, longitudinal, ongoing study | Planned to investigate associations between PhA, nutritional status, microbiota, patient DNA, and tumor progression; definitive results not yet reported. |

| Malecka-Massalska et al. (2013) | 31 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and 31 healthy controls matched by sex and age | Compare tissue electrical properties in cancer patients vs. controls | Cross-sectional study | Significantly lower PhA in patients (4.69°) vs. controls (5.59°); suggests nutritional/hydration alterations with potential prognostic value. |

| Morshed et al. (2022) | 54 male patients undergoing cancer surgery | Evaluate changes in body composition and PhA after surgery | Cross-sectional study | Significant reduction in PhA; decreases in weight, BMI, FFM, ICF, and TBW; increases in FM and ECF; decline in nutritional status (SGA). |

| Navigante et al. (2013) | 41 patients with advanced disease and fatigue and 20 matched healthy controls | Assess the relationship between fatigue, muscle strength, and PhA | Prospective observational study | Reduced PhA correlated with lower muscle strength; association between fatigue and cellular integrity evidenced by bioimpedance. |

| Axelsson et al. (2018) | 128 patients evaluated at diagnosis | Investigate PhA and SPA as prognostic predictors of survival | Prospective cohort | Lower PhA and SPA were associated with shorter survival; both were independent predictors of worse prognosis. |

| Büntzel et al. (2019) | 42 patients | Explore the relationship between PhA and survival | Observational study | PhA ≤ 5.0 associated with poorer survival; mean survival 13.8 months (≤ 5.0) vs. 51.2 months (> 5.0), p = 0.016. |

| Emir et al. (2024) | 100 patients (37 head/neck, 63 brain) | Evaluate PhA in relation to nutrition, inflammation, and survival during radiotherapy | Cross-sectional study | PhA cutoff = 5.72°; in head and neck tumors, 2-year survival was 87.5% vs. 32.1% (high vs. low PhA); PhA correlated with nutritional status and inflammation. |

| Herrera-Martínez et al. (2024) | 509 patients undergoing chemo- or radiotherapy | Compare PhA with other BIVA indicators in nutritional assessment | Cross-sectional observational study | Malnutrition was more prevalent in chemotherapy (59.2% vs. 40.8%); higher mortality in malnourished patients (33.3% vs. 20.1%); worse functional performance (ECOG) in malnourished patients. |

| Silva- Paiva et al. (2021) | 25 female breast cancer survivors (50.6 ± 8.6 years) | Evaluate a PhA cutoff as a marker of nutritional status and functional capacity | Cross-sectional study | PhA cutoff = 5.6°; values above this showed better fluid balance (lower ECW/ICW, ECW/BCM, ECW/TBW); no significant differences in functional capacity. |

| Yu et al. (2019) | 210 patients ≥65 years undergoing gastrectomy | Evaluate preoperative PhA as a predictor of complications | Retrospective study | Low PhA associated with overall complications (OR ≈ 2.9) and severe complications (OR ≈ 4.35). |

| Roh et al. (2023) | 25 patients with post-mastectomy lymphedema | Evaluate the impact of lymphatic-venular surgery on PhA and edema | Observational study | PhA inversely correlated with edema; surgery reduced arm volume and improved fluid balance. |

| Lundberg et al. (2019) | 61 patients evaluated preoperatively | Assess PhA as a predictor of length of stay and surgical complications | Prospective cohort | Low PhA values were associated with prolonged hospitalization and higher rates of surgical complications, suggesting its usefulness as a prognostic marker.. |

| Cai et al. (2023) | 92 surgical patients (gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal) | Investigate changes in PhA and body composition in the perioperative period | Observational cohort | PhA showed a continuous postoperative decline, accompanied by overall nutritional worsening, changes in body components, and correlations with serum markers. |

| Gupta et al. (2008) | 259 breast cancer patients | Evaluate the prognostic value of PhA for survival | Retrospective case series | PhA ≤ 5.6° was associated with lower survival, while each additional degree significantly reduced mortality risk, confirming its prognostic value.. |

| Sánches et al.(2010) | Patients with advanced lung cancer (stage IIIB–IV) treated with paclitaxel + cisplatin, randomized to oral EPA+DHA supplementation | Evaluate the effect of EPA+DHA on nutrition, inflammation, quality of life, and PhA | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Study planned to assess weight, LBM, PhA, QoL, toxicity, and inflammation; definitive results were not reported in this registry. |

| Gutiérrez-Santamaría et al. (2023) | 311 oncology patients | Explore the association between PhA and physical performance | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Each additional degree of PhA correlated with better physical performance, indicating a positive relationship between cellular integrity and clinical performance.. |

| Dalla Rovere et al. (2025) | 121 hospitalized patients with hematologic cancer | Investigate the value of PhA and handgrip strength for 12-month mortality | Retrospective observational study | Low PhA and HGS were independent predictors of 12-month mortality, identified as robust prognostic markers. |

| Lundberg et al. (2017) | 41 patients evaluated at initial diagnosis | Assess nutritional status and risk using PhA and BIVA | Prospective cohort | 76% had reduced PhA (median 4.6°); low values were associated with malnutrition and higher morbidity and mortality risk. |

| Kohli et al. (2018) | 20 Head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy | Evaluate changes in PhA throughout radiotherapy | Longitudinal cohort | Continuous reduction in PhA associated with weight loss and increased intracellular water. |

| Machado et al. (2022) | 1,023 ICU patients (including oncology) | Evaluate PhA as a predictor of 1-year mortality | Prospective cohort | Low PhA at admission independently predicted 1-year mortality (OR = 1.81; p = 0.02). |

| Pérez-Camargo et al. (2017) | 452 palliative care patients at the National Institute of Mexico | Evaluate PhA as a prognostic marker in palliative care | Observational study | PhA ≤ 4° associated with a median survival of 86 days vs. 163 days when > 4°; correlated with BMI and prognosis. |

| Tyagi et al. (2015) | 37 patients with tongue carcinoma and healthy controls | Compare PhA values between patients and controls | Case–control study | Patients with tongue carcinoma had significantly lower PhA than controls; use as a diagnostic and prognostic marker was suggested.. |

| Katsura et al. (2021) | 61 Cancer cachexia patients (n not reported) | Investigate whether ECW/TBW mediates the association between PhA and mortality | Retrospective study | Low PhA was associated with mortality; the relationship was partially mediated by the ECW/TBW ratio. |

| Mainardi et al. (2024) | 82 oncology patients (various types) | Explore the association between PhA and hematological parameters | Exploratory cross-sectional study | Hemoglobin and hematocrit correlated positively with PhA, suggesting a relationship between cellular integrity and hematologic status. |

| Bello et al. (2024) | 704 Patients with cancer; BIA and BMI data (n not reported) | Develop a machine learning (ML) model to predict nutritional status | Predictive study | The ML model predicted nutritional status with high accuracy from BIA and BMI data; PhA not reported. |

| Guedes et al. (2023) | 116 hospitalized cancer patients | Evaluate agreement between BIA devices | Cross-sectional study | Good agreement for PhA and FFM between devices from different manufacturers; confirmed by Bland–Altman analysis. |

| Gomes et al. (2020) | 124 cancer patients | Evaluate the association between PhA and fatigue | Cross-sectional study | PhA was not associated with fatigue after adjusting for hydration; the impact of extracellular water may mask the clinical relationship. |

| Gupta et al. (2009) | 165 patients with stage IIIB–IV non–small cell lung cancer | Evaluate the prognostic value of PhA | Retrospective case series | PhA ≤ 5.3° associated with a median survival of 7.6 months vs. > 5.3° with 12.4 months; each additional degree reduced mortality risk (RR = 0.79) |

| Kekez et al. (2025) | Metastatic colorectal cancer patients (n not reported) | Evaluate PhA as a prognostic biomarker | Prospective study | Ongoing/under review; full results not available, but proposed as a prognostic biomarker. |

| Maasberg et al. (2017) | 203 patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms | Evaluate the impact of malnutrition on clinical outcomes | Cross-sectional study | Malnutrition prevalence assessed by clinical instruments and BIA; nutritional status predicted clinical outcomes. |

| Da Silva et al. (2023) | 22 older female breast cancer survivors | Explore the association between PhA and muscle health/cardiorespiratory capacity | Observational pilot study | Higher PhA was associated with better cardiorespiratory capacity (R² = 0.54), greater muscle volume (R² = 0.83), and lower myosteatosis (R² = 0.25). |

| Cereda et al. (2024) | 640 oncology patients on systemic therapy (multicenter) | Evaluate the relationship between PhA/SPA and mortality/dose-limiting toxicity | Observational study | Low SPA and PhA were independently associated with mortality; SPA also predicted dose-limiting toxicity. |

| Motta et al. (20 | Patients with cancer eligible for radiotherapy (sample size not reported) | Define cutoff points for PhA and SPA before radiotherapy | Observational study | A PhA cutoff ≤ 5.2 indicated higher nutritional risk and lower survival; SPA showed additional predictive value. |

| Baş et al. (2023) | 53 Head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy | Determine PhA and SPA cutoffs for prognosis | Prospective cohort | Low PhA and SPA were associated with malnutrition and lower overall survival; specific cutoffs were defined. |

| Valentino et al. (2021) | 124 cancer patients (various types) | Evaluate the relationship between PhA and sarcopenia considering hydration | Cross-sectional study | Low PhA associated with increased risk of sarcopenia (OR = 1.74), even after adjusting for hydration. |

| Mialich et al. (2025) | 54 young women with non-metastatic breast cancer | Evaluate the association between muscle mass/quality, PhA, and mortality | Retrospective study | PhA correlated with muscle markers and mortality; low muscle mass was associated with worse prognosis. |

| Małecka-Massalska et al. (2016) | 75 newly diagnosed patients | Evaluate PhA as a marker of malnutrition | Prospective cohort | PhA cutoff = 4.73° detected malnutrition (80% sensitivity, 57% specificity); lower PhA in malnourished patients. |

| Yoon et al. (2018) | 38 patients with cachexia (GI, colorectal, and biliary) | Explore gender differences in body composition among cachectic patients | Observational pilot study | Lower PhA in women; reduced values compared to controls; ICW correlated positively with PhA. |

| Gulin et al. (2023) | 70 patients evaluated preoperatively | Assess PhA as a predictor of postoperative complications — Prospective study | Prospective study | PhA cutoff = 5.5° predicted complications; lower PhA values were associated with higher risk and longer length of stay. |

| Kashima et al. (2025) | 201 oncology patients | Evaluate the usefulness of PhA in locomotive syndrome (LS) | Cross-sectional study | Low PhA correlated with mobility decline; independent indicator of locomotive syndrome. |

| Schmidt et al. (2023) | 158 breast cancer patients undergoing a training program | Investigate the longitudinal association between PhA and fatigue | Randomized clinical trial | PhA decreased over the course of training; associated with the trajectory of fatigue. |

| Büntzel et al. (2012) | 110 patients (retrospective weight study); 66 patients with serial BIA (27 survived; 39 died) | Evaluate nutritional parameters and prognosis | Observational cohorts (retrospective and longitudinal) | PhA was stable/increased in survivors (4.7°→5.2°) and decreased in those who died (4.6°→3.7°); critical weight loss was associated with worse prognosis. |

| Company-Set al. (2023) | Lung tissue samples (neoplasia, fibrosis, pneumonia, emphysema, normal) via bronchoscopy | Evaluate differentiation of lung tissues using bioimpedance | Observational study | PhA and impedance parameters differentiated tumor from healthy tissue (p < 0.001); the technique showed good diagnostic accuracy. |

| Suzuki et al. (2023) | 240 patients undergoing lung surgery | Evaluate PhA as a predictor of postoperative complications | Retrospective cohort | PhA was an independent predictor of complications (OR = 0.51; p = 0.018). |

| Han et al. (2021–2022) | 160 operated colorectal cancer patients (110 followed longitudinally) | Investigate serial variations of PhA and ECW/TBW during treatment | Longitudinal cohort | PhA and ECW/TBW showed V-shaped changes over time during treatment (surgery + chemotherapy). |

| Kim et al. (2021) | 128 patients with cancer-related breast lymphedema | Test the feasibility of using segmental BIA for lymphedema assessment | Clinical feasibility study | Inter-arm s-PhA correlated negatively with edema severity; ECW/TBW was also altered. |

| Władysiuk et al. (2016) | 75 head and neck cancer patients | Evaluate PhA as a predictor of survival | Prospective cohort | PhA < 4.733° associated with reduced survival (19.6 vs. 45 months); HR ≈ 1.89; p = 0.049. |

| Vieira Maroun et al. (2024) | 35 patients with esophagogastric cancer | Explore the association of PhA and rectus femoris ultrasound in sarcopenia | Cross-sectional pilot study | RF-Y was an independent predictor of malnutrition and sarcopenia. → PhA showed only a weak correlation (r = 0.439). |

| Schulz et al. (2017) | 203 ambulatory oncology patients | Evaluate the relationship of PhA with quality of life, fatigue, and physical status | Descriptive observational study | Low PhA correlated with poorer quality of life; also associated with greater fatigue and lower physical function. |

| Escriche-Escuder et al. (2025) | 67 breast cancer survivors | Evaluate the impact of a 12-week exercise program on PhA | Prospective interventional cohort | PhA and resistance increased after the program. → Positive correlation with muscle strength and functional performance. |

| Kawata et al. (2025) | 134 Patients undergoing esophagectomy | Investigate the relationship between pre-op PhA, postoperative pneumonia, and survival | Retrospective cohort | Low PhA associated with higher risk of pneumonia. → Also linked to worse survival (full data restricted). |

| Zhou et al. (2022) | 49 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy | Assess the association between PhA, nutritional status, and complications | Prospective study | PhA cutoff ≤ 5.45° identified risk of malnutrition. → PhA cutoff ≤ 5.35° predicted postoperative complications. → Both showed good accuracy (AUC ≈ 0.7). |

| Souza et al. (2020) | 188 colorectal cancer patients | Compare methods of assessing muscle mass and PhA with CT | Prospective cohort | Low muscle mass and low PhA were associated with higher mortality; the association persisted after adjustment for age, sex, and treatment. |

| Frio et al. (2023) | 175 patients starting chemotherapy | Investigate the relationship between PhA, quality of life, and functionality | Longitudinal study | PhA declined from start to end of chemotherapy. → Associated with physical quality of life, functionality, and nutritional risk.. |

| Yasui-Yamada et al. (2020) | 501 patients undergoing gastrointestinal/hepatobiliary–pancreatic surgery | Evaluate the impact of preoperative PhA on postoperative prognosis | Retrospective study | Lowest PhA quartile had more complications, longer ICU stay, and lower 5-year survival. → PhA was an independent predictor of mortality. . |

| Wobith et al. (2020) | 102 patients undergoing upper GI/hepatobiliopancreatic surgery with nutritional jejunostomy (NCJ) | Evaluate the impact of jejunostomy on nutritional course and PhA | Retrospective study | NCJ was safe. → PhA and weight declined in the first 3 months and stabilized at 4–6 months. → NCJ helped attenuate weight loss. |

| Jiang et al. (2023) | 70 patients with newly diagnosed AML (excluding APL); median follow-up 9.3 months | Evaluate the prognostic and nutritional value of baseline PhA | Prospective cohort | Low PhA was associated with shorter PFS (7.1 vs. 11.6 months; p = 0.001) and reduced OS (8.2 vs. 12.1 months; p = 0.011). → PhA was an independent predictor of progression (HR 3.13). → Patients with low PhA had higher nutritional risk after chemotherapy. |

| Morlino et al. (2022) | 122 women with stage 0–III breast cancer (BMI < 30) + 80 controls | Estimate sarcopenia prevalence and its relationship with PhA/FFM | Cross-sectional study | Sarcopenia prevalence was 13.9%. → Sarcopenic women had significantly lower PhA (−0.5°, p = 0.048). → FFM was also lower in the sarcopenic group. |

| Mulasi et al. (2016) | 19 head and neck cancer patients (18 men, 1 woman), followed up to 3 months post-treatment | Compare Academy/ASPEN criteria vs. PG-SGA and assess the usefulness of PhA/IR | Prospective longitudinal study | 67% classified as malnourished by Academy/ASPEN criteria. → PG-SGA showed 94% sensitivity and 43% specificity. → Decreases in PhA and increases in IR correlated with PG-SGA and HGS. → Direct substitution with PhA/IR remains uncertain. |

| Castanho et al. (2012) | 0 men with NSCLC; tumor volume assessed by CT | Evaluate the relationship between PhA/ECM:BCM and tumor volume | Cross-sectional observational study | →PhA correlated negatively with tumor volume (r = −0.55). → The ECM/BCM ratio correlated positively (r = 0.59). → Tumor volume and Karnofsky score were independent predictors of PhA and ECM/BCM. |

| Barrea et al. (2018) | 83 patients with GEP-NET G1/G2 + 83 matched controls | Relate PhA and dietary adherence (PREDIMED) to tumor aggressiveness | Cross-sectional case–control study | → Lower PhA and lower PREDIMED adherence were associated with G2 tumors, presence of metastases, and progressive disease. → Patients showed poorer nutritional profiles in the more aggressive cases. |

| Paixão et al. (2021) | 62 patients in radiotherapy (subset of 104), 10-year follow-up | est the association of ΔPhA/ΔSPA and weight loss with mortality | Prospective cohort | ΔPhA and ΔSPA were not associated with mortality. → Weight loss during RT increased the risk of death (≈ +25% per −1 kg). → Age and irradiated site were also associated with risk. |

| Bae et al. (2022) | 191 hemodialysis patients (non-oncology) | Evaluate the impact of PhA and sarcopenia on survival — Retrospective longitudinal study | Retrospective longitudinal study | Better survival with PhA > 4°. → PhA was an independent predictor of survival (HR ≈ 0.51 per +1°, p = 0.010). → Higher IDWG, elevated CRP, and CAD were associated with worse prognosis. |

| Famularo et al. (2023) | 190 patients undergoing oncologic hepatectomy (76 with complications) | Associate PhA/SPA and body composition with postoperative complications | Prospective study | Complications occurred in 40% of patients. → SPA < −1.65 was an independent predictor of complications (OR 3.95). → Patients with complications had increased ECW and fat and reduced BCM/SMM. → Lower PhA and SPA were associated with complications. |

| Ji et al. (2020) | 445 men ≥65 years (NSCLC or digestive); sarcopenia prevalence = 22.2% | Correlate PhA with sarcopenia, handgrip strength (HGS), and SMI; define cutoff | Cross-sectional observational study | Lower PhA in sarcopenic patients (4.18° vs. 5.02°, p < 0.001). → OR for sarcopenia = 0.309. → PhA cutoff = 4.25° (AUC 0.785). → Significant correlations between PhA, HGS, and SMI. |

| — (2017, REE study) | Colorectal oncology patients (stages II–IV); subsamples for REE and validation | Examine resting energy expenditure (REE) in relation to body composition, intake, and activity; explore PhA, HGS, calf circumference, and PG-SGA as outcomes | Observational study | → REE assessed against composition, intake, and physical activity. → PhA, HGS, calf circumference, and PG-SGA included as exploratory variables. → Protocol ongoing with planned validations; definitive results not reported.. |

| Park et al. (2022) | 119 older men (70.7 ± 6.1 years) with prostate cancer | Assess the association of PhA with sarcopenia and physical performance | Retrospective study | Low PhA associated with sarcopenia (cutoff 4.87°; AUC 0.77). → PhA correlated positively with HGS. → Age, BMI, and HGS were variables associated with PhA. |

| Pagano et al. (2024) | 51 men with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Compare PhA (BIS) vs. TPAI (MRI) as predictors of nutritional risk and prognosis | Observational study | PhA outperformed TPAI in indicating nutritional risk and disease severity (CTP/BCLC). → PhA correlated positively with AMA, HGS, and NRI. |

| Paes et al. (2018) | 31 critically ill oncology patients in the ICU | Investigate the association between PhA, nutritional status, prognosis, and mortality | Prospective observational study | PhA ≤ 3.8° was associated with higher mortality and worse clinical outcomes (more ICU days, longer mechanical ventilation and hospital stay). → Positive correlation observed between PhA and albumin. |

| Di Renzo et al. (2019) | 50 postoperative oncology patients | Evaluate the effect of an immunomodulated formula on PhA and nutritional markers | Randomized clinical trial | The immunomodulated formula (EIN) increased PhA and improved prealbumin, RBP, and transferrin within 8 days. → Direct support for nutritional recovery and preparation for chemotherapy. |

| Nasser et al. (2024) | 152 preoperative patients with epithelial ovarian cancer | Examine PhA, NRI, and NRS-2002 and their clinical/prognostic implications | Prospective observational study | PhA ≤ 4.5° was the strongest predictor of overall survival (OS). → NRS-2002 ≥ 3 was associated with lower OS and a lower likelihood of complete cytoreduction. |

| Sarode et al. (2015) | 100 individuals (50 with oral squamous cell carcinoma—OSCC and 50 controls) | Evaluate the diagnostic utility of tissue bioimpedance | Cross-sectional study | Lower impedance (Z) in OSCC vs. controls. → Values decreased with stage and differed by histologic grade. → Suggests diagnostic value; Φ reported at extreme frequencies. |

| Roccamatisi et al. (2021) | 182 patients undergoing oncologic abdominal surgeries | Test preoperative SPA as a predictor of MDR/XDR infections | Prospective study | SPA was an independent predictor of MDR/XDR infection (OR 3.06; AUC 0.662; cutoff −0.3). → Complications in ~59% of cases. |

| Sánchez et al. (2012) | 119 patients with advanced NSCLC (pre-chemotherapy) | Relate nutritional/inflammatory parameters and PhA to overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) | Prospective study | PhA ≤ 5.8° was an independent predictor of worse OS (HR 3.02). → Low PhA was associated with poorer nutritional status and lower quality of life. |

| Zuo et al. (2024) | 248 patients (188 underwent radical gastrectomy) — | Validate PhA for screening malnutrition/sarcopenia and predicting complications | Cross-sectional study with a surgical subcohort | Each −1° in PhA increased the odds of malnutrition (OR 8.11) and sarcopenia (OR 2.90). → Low PhA predicted postoperative complications (OR 3.63). → PhA showed good diagnostic performance. |

| Da Silva et al. (2022) | 88 participants (36 breast cancer, 36 matched controls, 16 healthy); post-chemotherapy | Investigate metabolic/nutritional status and PhA after chemotherapy | Cross-sectional study | Breast cancer patients had lower PhA, HGS, and NRI. → Worse lipid/glycemic profile and greater visceral adiposity. → Unfavorable dietary pattern compared with controls. |

| Vegas-Aguilar et al. (2023) | 27 colorectal cancer patients in routine care | Evaluate nutritional tools as predictors of complications and sarcopenia (focus on PhA | Cross-sectional observational study | Women: higher PhA associated with fewer complications (OR 0.15). → Men: higher PhA associated with less sarcopenia (OR 0.42). → High diagnostic performance (AUC 0.894 and 0.959). → Consistent correlations with muscle parameters and body water. |

| Souza et al. (2021) | 190 colorectal cancer patients (78% stages III–IV) | Investigate PhA as a marker of muscle abnormalities and function | Cross-sectional study | Each −1° in PhA was associated with low SMI (OR 6.56) and low SMI+HGS (OR 11.10). → AUC between 0.80–0.88 indicated good accuracy. → Strong correlations between PhA, SMI, and HGS. |

| Limon-Miró et al. (2019) | 9 women with non-metastatic breast cancer, during treatment | Use BIVA/PhA to monitor response to a nutritional program | Pre–post intervention study | PhA increased in 8 of 9 patients (>5°). → Migration to more favorable BIVA quadrants. → Weight and fat decreased; slight drop in FFM with stable ASMM. |

| Pelzer et al. (2010) | 32 outpatients with advanced pancreatic cancer and cachexia | Evaluate the impact of additional parenteral nutrition on PhA and body composition | Phase II single-arm clinical trial | Median PhA increased by ~10% (3.6→3.9). → 84% improved in ≥1 parameter. → ECM/BCM ratio improved (1.7→1.5). → BMI increased from 19.7 to 20.5. |

| Lee et al. (2014) | 28 patients with advanced cancer (lung, hematologic, bladder, digestive) | Relate PhA to survival time | Prospective observational study | PhA correlated with survival. → Significant prediction both unadjusted and adjusted (HR ~0.64). → PhA > 4.4° associated with longer survival. |

| Bıçaklı et al. (2019) | 153 geriatric patients with gastrointestinal cancer, assessed pre- and post-chemotherapy | Evaluate sarcopenia/sarcopenic obesity and PhA before/after chemotherapy | Prospective descriptive study | No sex-based differences in PhA. → PhA was lower in malnourished vs. well-nourished patients. → Fat changes varied by sex. → Trend toward lower PhA in malnourished patients. |

| Pena et al. (2018) | 136 patients undergoing oncologic surgeries | Relate PhA/SPA to malnutrition and postoperative complications | Prospective observational study | SPA < −1.65 was associated with higher odds of malnutrition. → Patients with low SPA had more infections (p = 0.006). → No association with other clinical outcomes or mortality. |

| Sad et al. (2020) | 89 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) on chemotherapy ± targeted therapy | Relate PhA, BMI, and KRAS mutation to response and survival | Prospective observational stud | PhA < 4.1 was associated with poorer response and shorter survival. → Patients with PhA > 4.1 had survival > 36 months. → Higher PhA correlated with better clinical performance and body composition. |

| Inglis et al. (2022) | 59 patients with advanced prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and functional decline | Test the effect of high-dose vitamin D on PhA and function | Randomized clinical trial | High-dose supplementation significantly increased PhA compared with low dose; significant differences at week 12 (p = 0.014) and week 24 (p = 0.018). |

| Manikam et al. (2024) | 12 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer on chemotherapy, stratified by nutritional status | Evaluate changes in body composition and PhA with different diets during chemotherapy | Clinical trial | PhA increased in all groups during treatment. → Underweight patients showed a greater rise (4.08° → 4.50°). → Changes in SMM, FFM, FM, and VAT varied according to baseline nutritional status. |

| Ciho et al. (2020) | 237 patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic cancer | Identify predictors of severe complications — | Prospective clinical study | PhA < 4.75° was associated with ≥ IIIb complications (OR ≈ 3.15). → Also related to lower functional capacity. |

| Company-se et al. (2015) | 52 individuals with oral lichen planus vs. healthy mucosa | Evaluate tissue bioimpedance as a pre-neoplastic model | Cross-sectional study | OLP lesions showed reduced PhA compared with healthy mucosa; values normalized after treatment; impedance (Z) also showed alterations. |

| De Luis et al. (2006) | 67 participants (head and neck cancer patients vs. controls) | Compare electrical properties and body composition | Case–control study | PhA was lower in patients (6.9 ± 1.5 vs. 8.02 ± 1.3; p < 0.05). → Differences also observed in fat mass and fat-free mass. |

| Sehouli et al. (2021) | 226 patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic cancer | Evaluate sarcopenia, malnutrition, and PhA as predictors of complications and survival | Prospective study | PhA < 4.75° predicted severe complications (OR 3.52–3.95) and worse survival. → High fat mass and low muscle mass were also associated with complications. |

| García-García et al. (2023) | 57 oncology outpatients (AnyVida) | Test PhA and rectus femoris ultrasound as predictors of 12-month mortality | Prospective study | Non-survivors had PhA 4.7° vs. 5.4° in survivors. → Higher PhA reduced death risk (HR 0.42). → Cutoffs: PhA ≤ 5.6° (overall), ≤ 5.9° (men), ≤ 5.3° (women). |

| Norman et al. (2015) | 433 older adults with cancer, followed for 1 year | Relate PhA to strength, quality of life, and mortality | Prospective study | PhA decreased with age. → Low PhA was associated with lower strength (HGS/knee), worse quality of life (EORTC), more symptoms, and a 2× higher 1-year mortality risk (RR ≈ 2.11). |

| Bartoletti et al. (2021) | 123 candidates for prostate biopsy | Test BIA (including PhA) as diagnostic decision support | Prospective study | PhA did not differ between groups. → Resistance and reactance distinguished BPH vs. controls and cancer vs. controls. → PhA added no additional value to the diagnostic model. |

| Gosak et al. (2020) | 49 patients with advanced head and neck cancer undergoing RT/CRT | Investigate PhA, nutritional status, and psychological distress | Prospective study | Baseline PhA ≥ 5.2° associated with greater use of RT and concurrent chemotherapy. → PhA declined over treatment. → Lower psychological distress (HADS-A) was associated with higher PhA at final assessment. |

| López-Gómez et al. (2022) | 43 oncology patients at nutritional risk | Relate PhA with muscle ultrasound and body composition | Cross-sectional study | PhA correlated positively with rectus femoris area (MARA/MARAI) and FFMI. → Negative correlation with resistance. → Supports integrated morphofunctional use. |

| Ching et al. (2010) | 5 individuals, tongue tissue assessment (cancer vs. normal) | Explore BIA for tongue cancer screening | Prospective study | Lower impedance in tumor tissue. → PhA decreased with frequency but differentiated tissues. → Significant difference observed at 50 kHz. |

| Sun et al. (2010) | 12 individuals, tongue tissue assessment (control, NTT, CTT) | Test BIA for tongue cancer screenin | Prospective controlled study | Lower impedance in tumor tissue. → PhA varied with frequency and differentiated groups. → Notable differences: 20 Hz (lowest in CTT) and 50 kHz (higher in CTT vs. NTT/controls). |

| Matias et al. (2020) | 41 breast cancer survivors | Evaluate PhA as a marker of strength and body water | Cross-sectional study | PhA explained ~22% of variance in strength. → Remained a predictor after adjusting for age and MVPA. → Lymphedema × PhA interaction was not significant. |

| Silva et al. (2021) | 61 women with early breast cancer post-chemotherapy | Relate body composition, body water, and PhA to metabolic syndrome and outcomes | Prospective study | Increase in fat mass (+0.23 kg) and reduction in fat-free mass (−1.58 kg). → PhA decreased (6.04 → 5.18). → Water (ECW/ICW/TBW) and inflammatory changes linked to a worse metabolic profile. → Low PhA associated with poorer inflammatory response and cardiometabolic risk. |

| Tumas et al. (2020) | 92 patients with early pancreatic cancer undergoing duodenopancreatectomy | Evaluate the impact of nutritional status (FFMI/PhA/SPA) on inflammation and complications | Prospective study | Reduced PhA in 39% of patients. → Models combining LSMI, PhA, and sarcopenia explained variation in CRP and IL-6. → Categorical PhA featured in the best risk models for complications. |

| Skroński et al. (2018) | 50 patients with liver tumors eligible for resection | Describe perioperative changes in body composition and hydration using BIA | Prospective observational study | ECW increased (+1.58 L). → Reductions in FM (−1.52 kg), BCM (−1.25 kg), MM (−1.22 kg), and ICW (−0.9 L). → PhA decreased by an average of 0.61°. → Losses varied by type of surgery. → Higher baseline PhA. |

| Jachnis et al. (2021) | 76 patients with pancreatic/periampullary tumors | Associate nutritional status/composition and biomarkers (CA19-9, CEA) with clinical parameters | Prospective study | PhA correlated positively with BMI, Karnofsky, RBC, HCT, and HGB, and negatively with age. → Cachexia and nutritional-risk profiles were associated with poorer body composition, higher inflammation (CRP), and worse clinical performance. |

| Caccialanza et al. (2019) | 131 hypophagic oncology patients at nutritional risk | Test early supplemental parenteral nutrition (7 days) on body composition and PhA | Clinical trial | Intervention increased PhA (+0.25°; p = 0.001). → Patients who met calorie–protein targets had a larger PhA gain (+0.39°) vs. a decrease in non-adherent patients (−0.11°). → BIVA vectors improved with adherence. |

| Ozorio et al. (2019) | 109 patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer | Validate/adjust a resting energy expenditure (REE) equation incorporating fat-free mass and PhA | Retrospective observational study | Fat-free mass, PhA, and sex were independent predictors of REE. → Proposed equation: REE = 619.9 + 18.9×FFM (kg) + 29.6×PhA + 111.5×sex. → PhA contributed to higher model accuracy. |

| Grusdat et al. (2022) | 19 young women at the start of breast cancer treatment (surgery/CT/RT) | Describe biopsychosocial profile and PhA trajectory at treatment onset | Prospective observational study | Functional status and PhA declined from T0 to T1. → Critical PhA in 11% at T0 and 42% at T1. → Indicates rapid deterioration of cellular status early in therapy. |

| Viertel et al. (2019) | 227 patients with various cancers | Compare low SMI-CT, muscle attenuation, and low PhA for detecting nutrition-related mortality risk | Prospective study | Low PhA (<5th percentile) in 64% of patients. → High sensitivity (86.7%) and high negative predictive value (96.9%) for mortality. → PhA proved useful for screening nutrition-related mortality risk. |

| Nusca et al. (2021) | 11 patients with laparoscopic colorectal cancer undergoing postoperative rehabilitation | Evaluate the effect of postoperative physical training on nutritional parameters (including PhA) | Randomized pilot clinical trial | The intervention group showed an increase in PhA over time (significant T0–T2 and T0–T3). → Suggests early functional and nutritional benefits of the program. |

| Cereda et al. (2020) | 1,084 oncology patients (Italian and German cohorts) | Validate a new prognostic parameter (Nutrigram®) versus FFMI and SPA for mortality | Cohort | In the Italian cohort, low FFMI, low SPA, and low Nutrigram® predicted mortality. → In the German cohort, only Nutrigram® retained predictive value. → PhA/SPA contributed, but performance varied by cohort. |

| León-Idougourram et al. (2022) | 45 patients with head and neck cancer on systemic therapy | Assess morphofunctional nutritional status and the role of the inflammasome | Prospective study | SPA < −1.65 associated with greater chemotherapy toxicity. → Lower PhA correlated with lower BMI, reduced muscle circumference, and lower adiposity. → Elevated IL-6 and CRP linked to reduced PhA. |

| Flores-Cisneros et al. (2022) | 207 patients undergoing chemotherapy | Investigate predictors of gastrointestinal toxicity | Prospective study | Low PhA associated with higher risk of GI toxicity (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.50–0.83). → Muscle strength and overhydration were important complementary variables. |

| Maurício et al. (2017) | 84 colorectal cancer patients undergoing resection | Compare nutritional tools for predicting postoperative complications | Prospective cohort | PhA < −1.65 did not predict complications (RR 1.53; 95% CI 0.79–2.92). → No relevant BIA markers for complications were identified. |

| Sandini et al. (2024) | 542 oncology patients undergoing abdominal surgery | Evaluate ΔPhA as a predictor of morbidity in ERAS programs | Prospective study | PhA and SPA fell in the immediate postoperative period. → ΔPhA < −0.5 was associated with higher morbidity (59% vs. 46%). → Predictive value for major complications (CDC ≥ 3) with OR ≈ 1.7. |

| Huang et al. (2024) | 72 esophageal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy | Evaluate the impact of post-CRT functional support | Prospective study | Trunk and limb PhA decreased by 0.4–0.6° after CRT. → PhA was a more sensitive marker than ASMI/FFM for monitoring nutritional status. |

| Fernández-Medina et al. (2022) | 50 patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | Assess morphofunctional nutritional status | Retrospective study | Mean PhA = 5.7. → Reduced PhA associated with more aggressive tumors. → Significant sex differences. → GEP-NET patients showed lower fat, lower body cell mass, and higher body water. |

| Justa et al. (2022) | 114 female breast cancer survivors | Investigate the relationship between PhA and tumor aggressiveness | Prospective study | Significant PhA reduction associated with tumors > 2 cm, advanced stage, node-positive, ER−/PR−. → Luminal and smaller tumors showed a lower prevalence of reduced PhA. |

| Ferreira et al. (2021) | 25 individuals with cancers at various stages | Relate SPA/PhA to clinical staging | Cross-sectional study | Values between 4.0–2.0 were associated with severe risk. → Values < 2.0 indicated imminent risk of death. → The association between PhA and staging was not statistically significant. |

| Nishiyama et al. (2018) | 40 surgical patients with colorectal disease | Evaluate nutritional status and surgical complications | Retrospective study | Malnourished patients had lower PhA (p = 0.002). → ECW/ICW and ECW/TBW were elevated. → PhA < 6° predicted infection with good sensitivity and specificity. |

| Pena et al. (2016) | 121 oncologic surgical patients | Investigate the association of SPA with nutrition and clinical outcomes | Prospective study | Patients at nutritional risk by SPA had greater malnutrition (SGA, arm circumference, arm muscle area, handgrip strength) and more weight loss. → Higher risk of infectious complications (OR = 3.51). → No association with other clinical outcomes. |

| Prior-Sánchez et al. (2024) | 494 patients in a multicenter cohort undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer | Evaluate the prognostic value of BIA parameters (PhA, BCM, FFMI, FMI, SMI, water) | Multicenter observational study | Higher PhA and higher BCM were associated with fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and better overall survival. → PhA cutoff ≈ 5.1° (4.8° for women). → BCM was the strongest predictor of survival. → Higher PhA significantly reduced hospitalization risk. |

| Martínez-Herrera et al. (2023) | 139 head and neck cancer patients, sex-stratified analysis | Relate PhA to clinical/biological behavior and quality of life | Observational study | Lower PhA was associated with worse overall survival. — Women with PhA < 3.9° and men with PhA < 4.5° had higher mortality and poorer performance. — Marked sex differences in body fat and SMMI. |

| Sandini et al. (2023) | 161 patients undergoing pancreatic surgery, long follow-up | Evaluate the effect of fat-to-muscle ratio and PhA/SPA on survival | Prospective study | Each 1-unit increase in PhA and SPA was associated with better overall survival. → Higher ECW, fat mass (FM), and FM/FFM ratio were associated with worse survival. → Median survival: 44 months (FM/FFM < 27) vs. 26 months (≥ 27). |

| Turgay et al. (2022) | 31 women with cancer-related breast lymphedema | Evaluate bioimpedance spectroscopy for lymphedema severity/staging | Cross-sectional study | Impedance and resistance ratios across frequencies correlated with stage. → PhA was not associated with lymphedema severity or stage |

| Kutz et al. (2021) | 58 head and neck cancer patients undergoing (chemo)radiotherapy with nutritional intervention (HEADNUT) | Test predictors of survival during a nutritional intervention | Randomized controlled clinical trial | PhA ≤ 4.7° was associated with worse overall survival. → One– and two–year survival was 93.1% and 90.8%. → Baseline PhA was prognostic; the nutritional intervention accompanied treatment. |

| Ramírez Martínez et al. (2021) | 70 cervical cancer patients | Relate PhA to clinical/socioeconomic variables and body composition | Cross-sectional study. | PhA was associated with BMI, muscle mass, and water markers. → PhA varied by age and socioeconomic level. → No association with treatment type. → Multiple model explained R² ≈ 0.75. |

| Löser et al. (2021) | 61 head and neck cancer patients in the HEADNUT trial | Evaluate PhA and FFMI during (chemo)radiotherapy with nutritional intervention | Randomized controlled clinical trial | FFMI dropped significantly during treatment. → PhA did not change significantly. → Baseline PhA > 4.7° predicted better overall survival. → End-of-treatment PhA did not predict overall survival. |

| Ramos et al. (2021) | Women with early-stage breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy |

To evaluate the relationship between phase angle and functional, anthropometric, and body composition parameters during and after chemotherapy |

Prospective study |

75% of women showed decreased phase angle after chemotherapy; low PhA was already present at baseline and end of treatment; PhA correlated with other anthropometric indicators |

| Inci et al. (2020) |

Women undergoing gynecological cancer surgery (RISC-Gyn Trial) |

To identify predictive markers for severe postoperative complications in gynecological cancer surgery |

Prospective clinical study |

Lower PhA was associated with higher rates of severe postoperative complications (≥ grade IIIb) and reduced functional capacity. A PhA < 4.75° was linked to higher odds of severe complications (OR 3.51; 95% CI 1.68–7.35; p=0.001). |

| Tatullo et al. (2015) |

Patients with Oral Lichen Planus (OLP) |

To evaluate bioimpedance as a diagnostic tool in OLP lesions |

Cross-sectional study |

OLP lesions showed significantly lower phase angle (θ) in tongue and oral mucosa compared to healthy tissues. Treated OLP lesions had PhA values similar to healthy mucosa, suggesting recovery of tissue integrity. |

| Luis et al. (2006) |

Patients with head and neck cancer vs. healthy controls |

To assess tissue electrical properties in head and neck cancer patients |

Case-control study |

Cancer patients showed significantly lower PhA (6.9±1.5° vs. 8.02±1.3°, p<0.05) and reduced fat-free mass compared to controls, indicating poorer nutritional and cellular integrity. |

| Sehouli et al. (2021) |

Patients undergoing gynecological cancer surgery |

To investigate the impact of sarcopenia and malnutrition on morbidity and mortality |

Prospective study |

PhA < 4.75° strongly predicted severe postoperative complications (OR 3.95; 95% CI 1.71–9.10; p=0.001) and lower overall survival. Low muscle mass and high fat mass were also linked to worse outcomes. |

| Richter et al. (2012) |

Patients with pancreatic cancer receiving parenteral nutrition |

To assess the effects of parenteral nutrition on nutritional status and outcomes |

Prospective study |

Parenteral nutrition improved PhA in long-term survivors, indicating benefit from nutritional support; in short-survival patients, disease progression mitigated any improvement in PhA. |

| Regüeiferos et al. (2022) |

Newly diagnosed adult lung cancer patients |

To analyze clinical, bioelectrical, and functional variables in lung cancer patients |

Prospective and cross-sectional pilot study |

Women and older men had lower PhA values compared to young men. In women, PhA was lower in both healthy and cancer groups. About 21.7% of patients had below-normal PhA, suggesting altered cellular integrity in lung cancer. |

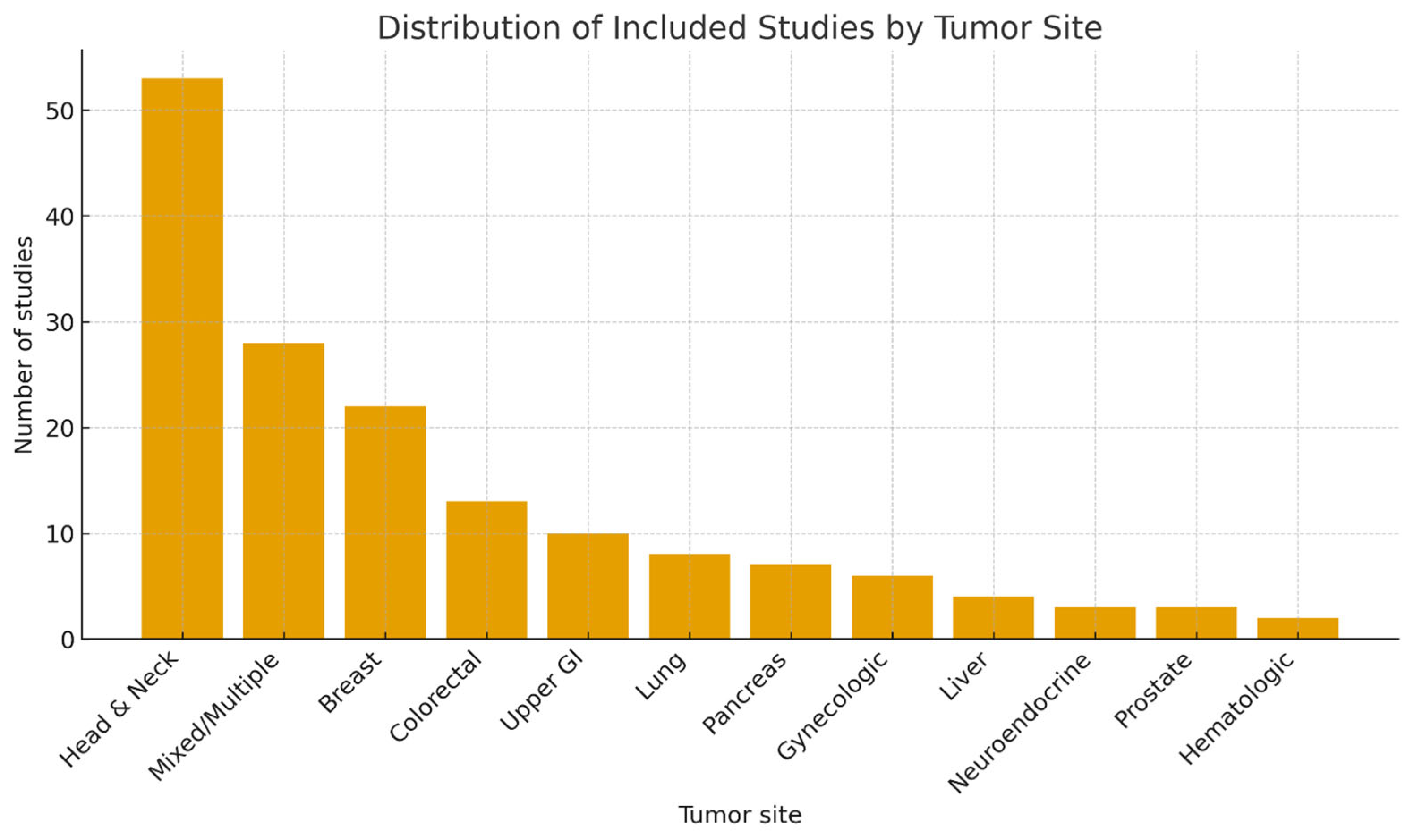

Study Designs and Distribution by Tumor Site

Phase Angle as a Central Marker

Impact of Therapeutic Modalities on Bioimpedance

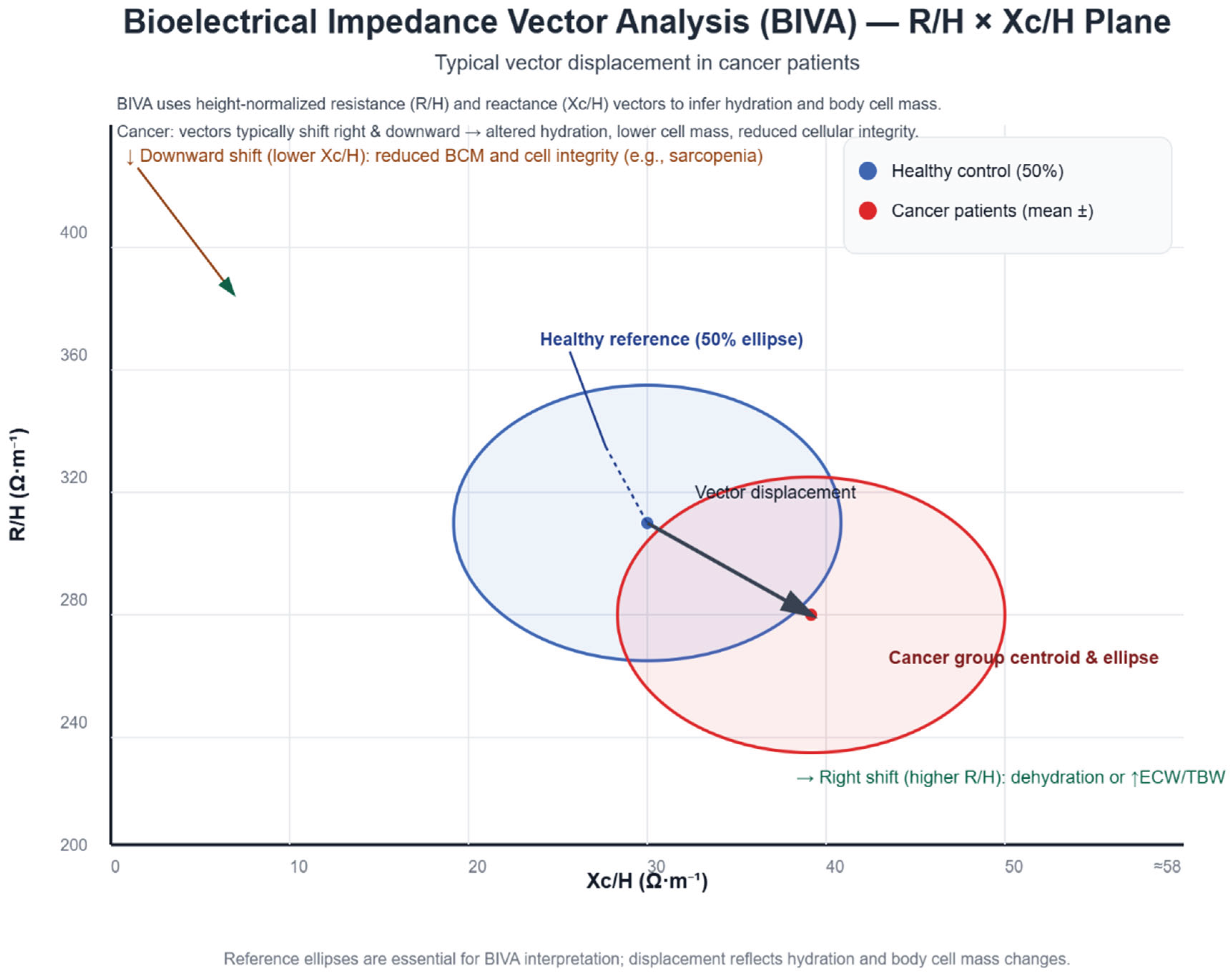

Other Relevant Bioimpedance Markers

Differences by Cancer Type

Standardization and Methodological Aspects

Discussion

Alterations in Phase Angle in Cancer Patients

Impact of Therapeutic Modalities

- Chemotherapy

Oncologic Surgery

Radiotherapy

Combined Therapies

Nutritional Status and Prognosis

Overall Survival and Hospital Complications

Quality of Life and Functionality

Clinical Integration, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

References

- Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:11–48. [CrossRef]

- Ryan AM, Power DG, Daly L, Cushen SJ, Ní Bhuachalla E, Prado CM. Cancer-associated malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia: the skeleton in the hospital closet 40 years later. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:199–211. [CrossRef]

- Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:5–15. [CrossRef]

- Paiva SI, Borges LR, Halpern-Silveira D, Assunção MCF, Barros AJD, Gonzalez MC. Standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis as prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(2):187–92. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Rovere L, et al. Role of bioimpedance phase angle and hand grip strength in predicting 12-month mortality in patients admitted with haematologic cancer. Cancers. 2025;17(5):886. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez MC, Pastore CA, Orlandi SP, Heymsfield SB. Obesity paradox in cancer: new insights provided by body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:999–1005. [CrossRef]

- Santarpia L, et al. Prognostic significance of bioelectrical impedance phase angle in advanced cancer: preliminary observations. Nutrition. 2009;25(9):930–1. [CrossRef]

- Grundmann O, Yoon SL, Williams JJ. The value of bioelectrical impedance analysis and phase angle in the evaluation of malnutrition and quality of life in cancer patients: a comprehensive review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(12):1290–7. [CrossRef]

- Bosy-Westphal A, et al. Quantification of whole-body and segmental skeletal muscle mass using phase-sensitive 8-electrode medical bioelectrical impedance devices. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(9):1061–7. [CrossRef]

- Lukaski HC, Kyle UG, Kondrup J. Assessment of adult malnutrition and prognosis with bioelectrical impedance analysis: phase angle and impedance ratio. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20(5):330–9. [CrossRef]

- Bello O, et al. Cancer predictive model derived from bioimpedance measurements using machine learning methods. Clin Nutr Open Sci. 2024;58:100–7. [CrossRef]

- Seo Y, et al. Can nutritional status predict overall survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer? Nutr Cancer. 2019;71(7):1108–17. [CrossRef]

- Yasui-Yamada S, et al. Impact of phase angle on postoperative prognosis in patients with gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer. Nutrition. 2020;79–80:110891. [CrossRef]

- Montes-Ibarra M, Orsso CE, Limon-Miro AT, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of abnormal body composition phenotypes in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023;117(6):1288–305. [CrossRef]

- Bellido D, et al. Future lines of research on phase angle: strengths and limitations. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2023;24(3):563–83. https:/doi.org/10.1007/s11154-023-09803-7.

- Yates SJ, Lyerly S, Manuel M, et al. The prognostic value of standardized phase angle in adults with acute leukemia: a prospective study. Cancer Med. 2020;9(7):2403–13. [CrossRef]

- Belarmino G, Gonzalez MC, Torrinhas RS, et al. Phase angle obtained by bioelectrical impedance analysis independently predicts mortality in patients with cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(7):401–8. [CrossRef]

- Nwosu AC, Mayland CR, Mason S, Cox TF, Varro A, Stanley S, Ellershaw J. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA) as a method to compare body composition differences according to cancer stage and type. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;30:59–66. [CrossRef]

- Limon-Miro AT, Lopez-Teros MT, Astiazaran-Garcia H. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA) in breast cancer patients: a tool for monitoring body composition changes. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):1509. [CrossRef]

- da Costa Pereira JP, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis and BIVA as bedside tools for estimating body composition and predicting outcomes in hospitalized cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2024;43(4):101358. [CrossRef]

- Branco MG, et al. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA) as a method to compare body composition differences according to cancer stage and type. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2023;55:1132972. [CrossRef]

- Büntzel J, et al. Phase angle as a predictor for survival in head and neck cancer. In Vivo. 2019;33(5):1519–24. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, et al. Phase Angle and Nutritional Status in Individuals with Advanced Cancer in Palliative Care. Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia 2019; 65(1): e-02272. https://orcid. 0000.

- Kohli R, et al. Phase angle changes during radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31(5):679–85. [CrossRef]

- Baş D, Atahan C, Tezcanli E. An analysis of phase angle and standard phase angle cut-off values and their association with survival in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Clin Nutr. 2023 Aug;42(8):1445-1453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo-Espinoza O, et al. Phase angle as an indicator of inflammation, cell integrity and nutrition in obese women with breast cancer. Nutr Hosp. 2024;41(1):97–104. [CrossRef]

- Gupta D, et al. Phase angle as a predictor of nutritional status in colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1630–4. [CrossRef]

- Kawata S, et al. Preoperative phase angle and postoperative complications in esophageal cancer. Esophagus. 2025;22(2):234–42. [CrossRef]

- Kekez T, et al. Prognostic significance of phase angle in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Nutr. 2025;44(1):55–63; Detopoulou P, et al. Phase angle and diet in cancer cachexia and sarcopenia: evidence from lung cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2022;25(3):231-6. 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000860. [CrossRef]

- Löser C, et al. Extracellular water/total body water ratio mediates the association between phase angle and mortality in cancer cachexia. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(6):4174–82. [CrossRef]

- Leo A, et al. Combined use of phase angle and G8 score improves nutritional risk assessment in elderly cancer patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14(8):101556. [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier NCT01133154. Efficacy of paclitaxel and cisplatin plus EPA/DHA in lung cancer. 2010. Disponível em: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01133154.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier NCT06272182. Effect of perioperative nutritional supplementation on phase angle in breast cancer. 2025. Disponível em: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06272182.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier NCT01890988. Prognostic value of standardized phase angle in acute leukemia. 2013. Disponível em: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01890988.

- Nuno; SANTOS, Teresa; MÄKITIE, Antti; et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) for body composition assessment in oncology: a scoping review. Nutrients, v. 15, n. 22, p. 4792, 2023. [CrossRef]

- PRETE, Melania; BALLARIN, Giada; PORCIELLO, Giuseppe; ARIANNA, Aniello; LUONGO, Assunta; BELLI, Valentina; et al. Phase angle (PhA) derived from bioelectrical impedance analysis in lung cancer patients: a systematic review. BMC Cancer, v. 24, n. 12378, 2024. [CrossRef]

- ERRERA-MARTÍNEZ, Aura D. ; PRIOR-SÁNCHEZ, Imaculada; FERNÁNDEZ-SOTO, María Luisa, GARCÍA-OLIVARES, María, NOVO-RODRÍGUEZ, Cristina, GONZÁLEZ-PACHECO, María, Eds.; et al. Improving nutritional assessment in head and neck cancer patients using bioelectrical impedance analysis: it’s not only phase angle that matters. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, v. 15, n. 4, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMANO, Koji; BRUERA, Eduardo; HUI, David. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of phase angle in cancer patients. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, v. 23, n. 4, p. 629-640, 2022. [CrossRef]

- GRUNDMANN, O.; YOON, S. L.; WILLIAMS, J. J. The value of bioelectrical impedance analysis and phase angle in the evaluation of malnutrition and quality of life in cancer patients – a comprehensive review. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 69, n. 12, p. 1290-1297, 2015. [CrossRef]

- ZHOU, Shen Nan; YU, Zhangping; SHI, Xiaodong; ZHAO, Huai Yu; DAI, Menghua; CHEN, Wei. Relationship between phase angle, nutritional status and complications in patients with pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 19, n. 11, p. 6426, 2022. [CrossRef]

- CONDE FRIO, Camila; HÄRTER, Jéssica; SANTOS, Leonardo Pozza; ORLANDI, Silvana Paiva; GONZÁLEZ, Maria Cristina. Phase angle, physical quality of life, and functionality in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, v. 54, p. 396-403, 2023. [CrossRef]

- PENA, Natália F.; MAURICIO, Sílvia F.; RODRIGUES, Ana M. S.; CARMO, Ariene S.; COURY, Nayara C.; CORREIA, Maria I. T. D.; et al. Standardized phase angle, nutritional status and clinical outcomes in surgical cancer patients. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, v. 33, n. 5, p. 743-750, 2018. [CrossRef]

- GOSAK, M.; GRADIŠAR, K.; ROTOVNIK KOZJEK, N.; STROJAN, P. Psychological distress and nutritional status in head and neck cancer patients: a pilot study. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, v. 277, n. 4, p. 1211-1217, 2020. [CrossRef]

- DELLA VALLE, S.; COLATRUGLIO, S.; LA VELA, V.; TAGLIABUE, E.; MARIANI, L.; GAVAZZI, C. Nutritional intervention in head and neck cancer patients during chemo-radiotherapy. Nutrition, v. 51-52, p. 95-97, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; YASUI-YAMADA, S.; FURUMOTO, T.; KUBO, M.; HAYASHI, H.; KITAO, M.; Association of phase angle with muscle function and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy. Nutrition, v.; et al. A.; YASUI-YAMADA, S.; FURUMOTO, T.; KUBO, M.; HAYASHI, H.; KITAO, M.; et al. Association of phase angle with muscle function and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy. Nutrition, v. 103-104, 111798, 2022. [CrossRef]

- HOPANCI BIÇAKLI, D.; ÇEHRELI, R.; ÖZVEREN, A.; MESERI, R.; USLU, R.; KARABULUT, B.; AKÇIÇEK, F. Evaluation of sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and phase angle in geriatric gastrointestinal cancer patients: before and after chemotherapy. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, v. 49, n. 2, p. 583-588, 2019. [CrossRef]

- COTOGNI, Paulo; MONGE, Taira; FADDA, Maurizio; DE FRANCESCO, Antonella. Bioelectrical impedance analysis for monitoring cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and home parenteral nutrition. BMC Cancer, v. 18, n. 990, 2018. [CrossRef]

- RIETVELD, S. C. M.; WITVLIET-VAN NIEROP, J. E.; OTTENS-OUSSOREN, K.; VAN DER PEET, D. L.; DE VAN DER SCHUEREN, M. A. E. The prediction of deterioration of nutritional status during chemoradiation therapy in patients with esophageal cancer. Nutrition and Cancer, v. 70, n. 2, p. 229-235, 2018. [CrossRef]

- STEGEL, P.; KOZJEK, N. R.; BRUMEN, B. A.; STROJAN, P. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle as indicator and predictor of cachexia in head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo)radiotherapy. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 70, n. 5, p. 602-606, 2016. [CrossRef]

- RAMOS DA SILVA, Bruna; RUFATO, S.; MIALICH, M. S.; CRUZ, L. P.; GOZZO, T.; JORDAO, A. A. Metabolic syndrome and unfavorable outcomes on body composition and in visceral adiposities indexes among early breast cancer women post-chemotherapy. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, v. 44, p. 306-315, 2021. [CrossRef]

- MANIKAM, N. R. M.; ANDRIJONO, A.; WITJAKSONO, F.; KEKALIH, A.; SUNARYO, J.; WIDYA, A. S.; NURWIDYA, F. Dynamic changes in body composition and protein intake in epithelial ovarian cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a preliminary study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, v. 25, n. 2, p. 555-562, 2024. [CrossRef]

- BAŞ, D.; ATAHAN, C.; TEZCANLI, E. An analysis of phase angle and standard phase angle cut-off values and their association with survival in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Clinical Nutrition, v. 42, n. 8, p. 1445-1453, 2023. [CrossRef]

- YAMANAKA, A.; YASUI-YAMADA, S.; FURUMOTO, T.; KUBO, M.; HAYASHI, H.; KITAO, M.; et al. Association of phase angle with muscle function and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy. Nutrition, v. 103-104, 111798, 2022. [CrossRef]

- LÖSER, A.; ABEL, J.; KUTZ, L. M.; KRAUSE, L.; FINGER, A.; GREINERT, F.; et al. Head and neck cancer patients under (chemo-)radiotherapy undergoing nutritional intervention: results from the prospective randomized HEADNUT-trial. Radiotherapy and Oncology, v. 159, p. 82-90, 2021. [CrossRef]

- MAŁECKA-MASSALSKA, T.; POWRÓZEK, T.; PRENDECKA, M.; MLAK, R.; SOBIESZEK, G.; BRZOZOWSKI, W.; BRZOZOWSKA, A. Phase angle as an objective and predictive factor of radiotherapy-induced changes in body composition of male patients with head and neck cancer. In Vivo, v. 33, n. 5, p. 1645-1651, 2019. [CrossRef]

- POWRÓZEK, T.; BRZOZOWSKA, A.; MAZUREK, M.; MLAK, R.; SOBIESZEK, G.; MAŁECKA-MASSALSKA, T. Combined analysis of miRNA-181a with phase angle derived from bioelectrical impedance predicts radiotherapy-induced changes in body composition and survival of male patients with head and neck cancer. Head & Neck, v. 41, n. 9, p. 3247-3257, 2019. [CrossRef]

- KOHLI, K.; CORNS, R.; VINNAKOTA, K.; STEINER, P.; ELITH, C.; SCHELLENBERG, D.; KWAN, W.; KARVAT, A. A bioimpedance analysis of head-and-neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Current Oncology, v. 25, n. 3, p. e193-e199, 2018. [CrossRef]

- BOĆKOWSKA, M.; KOSTRO, P.; KAMOCKI, Z. K. Phase angle and postoperative complications in a model of immunonutrition in patients with pancreatic cancer. Nutrients, v. 15, n. 20, p. 4328, 2023. [CrossRef]

- LIU, X. Y.; KANG, B.; LV, Q.; WANG, Z. W. Phase angle is a predictor for postoperative complications in colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Nutrition, v. 11, p. 1446660, 2024. [CrossRef]

- UCCELLA, S.; MELE, M. C.; QUAGLIOZZI, L.; RINNINELLA, E.; NERO, C.; CAPPUCCIO, S.; et al. Assessment of preoperative nutritional status using BIA-derived phase angle (PhA) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: correlation with the extent of cytoreduction and complications. Gynecologic Oncology, v. 149, n. 2, p. 263-269, 2018. [CrossRef]

- KLASSEN, D.; STRAUCH, C.; ALTEHELD, B.; LINGOHR, P.; MATTHAEI, H.; VILZ, T.; et al. Assessing the effects of a perioperative nutritional support and counseling in gastrointestinal cancer patients: a retrospective comparative study with historical controls. Biomedicines, v. 11, n. 2, p. 609, 2023. [CrossRef]

- I, M.; GIANOTTI, L.; PAIELLA, S.; BERNASCONI, D. P.; ROCCAMATISI, L.; FAMULARO, S.; et al. Predicting the risk of morbidity by GLIM-based nutritional assessment and body composition analysis in oncologic abdominal surgery in the context of enhanced recovery programs: the PHAVAS study. Annals of Surgical Oncology, v. 31, n. 6, p. 3995-4004, 2024. [CrossRef]

- LAI, Y. T.; PEH, H. Y.; BINTE ABDUL KADIR, H.; LEE, C. F.; IYER, N. G.; WONG, T. H.; et al. Bioelectrical-impedance-analysis in the perioperative nutritional assessment and prediction of complications in head-and-neck malignancies. OTO Open, v. 9, n. 1, e70046, 2025. [CrossRef]

- WOBITH, M.; WEHLE, L.; HABERZETTL, D.; ACIKGÖZ, A.; WEIMANN, A. Needle catheter jejunostomy in patients undergoing surgery for upper gastrointestinal and pancreato-biliary cancer – impact on nutritional and clinical outcome in the early and late postoperative period. Nutrients, v. 12, n. 9, p. 2564, 2020. [CrossRef]

- MATTHEWS, L.; BATES, A.; WOOTTON, S. A.; LEVETT, D. The use of bioelectrical impedance analysis to predict post-operative complications in adult patients having surgery for cancer: a systematic review. Clinical Nutrition, v. 40, n. 5, p. 2914-2922, 2021. [CrossRef]

- CAI, B.; LUO, L.; ZHU, C.; MENG, L.; SHEN, Q.; FU, Y.; et al. Influence of body composition assessment with bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in cancer patients undergoing surgery. Frontiers in Oncology, v. 13, p. 1132972, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASKLOF, M.; KJØLHEDE, P.; WODLIN, N. B.; NILSSON, L. Bioelectrical impedance analysis: a new method to evaluate lymphoedema, fluid status, and tissue damage after gynaecological surgery – a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, v. 228, p. 111-119, 2018. [CrossRef]

- SANDINI, M.; PAIELLA, S.; CEREDA, M.; ANGRISANI, M.; CAPRETTI, G.; FAMULARO, S.; et al. Independent effect of fat-to-muscle mass ratio at bioimpedance analysis on long-term survival in patients receiving surgery for pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in Nutrition, v. 10, p. 1118616, 2023. [CrossRef]

- KUTZ, L. M.; ABEL, J.; SCHWEIZER, D.; TRIBIUS, S.; KRÜLL, A.; PETERSEN, C.; LÖSER, A. Quality of life, HPV-status and phase angle predict survival in head and neck cancer patients under (chemo)radiotherapy undergoing nutritional intervention. Radiotherapy and Oncology, v. 166, p. 145-153, 2022. [CrossRef]

- YANG, L. Y.; CHAO, Y. K.; CHANG, W. Y.; TSAO, Y. T.; CHOU, C. Y.; et al. Improved functional oral intake and exercise training attenuate decline in aerobic capacity following chemoradiotherapy in patients with esophageal cancer. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, v. 56, jrm25906, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A VALLE, S.; COLATRUGLIO, S.; LA VELA, V.; TAGLIABUE, E.; MARIANI, L.; GAVAZZI, C. Nutritional intervention in head and neck cancer patients during chemo-radiotherapy. Nutrition, v. 51-52, p. 95-97, 2018. [CrossRef]

- LUNDBERG, M.; NIKANDER, P.; TUOMAINEN, K.; ORELL-KOTIKANGAS, H.; MÄKITIE, A. Bioelectrical impedance analysis of head and neck cancer patients at presentation. Acta Otolaryngologica, v. 137, n. 4, p. 417-420, 2017. [CrossRef]

- DETOPOULOU, P.; VOULGARIDOU, G.; PAPADOPOULOU, S. Cancer, phase angle and sarcopenia: the role of diet in connection with lung cancer prognosis. Lung, v. 200, n. 3, p. 347-379, 2022. [CrossRef]

- PAIXÃO, E. M. S.; GONZALEZ, M. C.; NAKANO, E. Y.; ITO, M. K.; PIZATO, N. Weight loss, phase angle, and survival in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: a prospective study with 10-year follow-up. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 75, n. 5, p. 823-828, 2021. [CrossRef]

- YANG, J.; XIE, H.; WEI, L.; RUAN, G.; ZHANG, H.; SHI, J.; et al. Phase angle: a robust predictor of malnutrition and poor prognosis in gastrointestinal cancer. Nutrition, v. 125, 112468, 2024. [CrossRef]

- ARAB, A.; KARIMI, E.; VINGRYS, K.; SHIRANI, F. Is phase angle a valuable prognostic tool in cancer patients’ survival? A systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature. Clinical Nutrition, v. in cancer patients’ survival? A systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature. Clinical Nutrition, v. 40, n. 5, p. 3182-3190, 2021. [CrossRef]

- AMANO, K.; BRUERA, E.; HUI, D. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of phase angle in patients with cancer. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, v. 24, n. 3, p. 479-489, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, X.; ZHAO, W.; DU, Y.; ZHANG, J.; ZHANG, Y.; LI, W.; et al. A simple assessment model based on phase angle for malnutrition and prognosis in hospitalized cancer patients. Clinical Nutrition, v. 41, n. 6, p. 1320-1327, 2022. [CrossRef]

- GARLINI, L. M.; ALVES, F. D.; CERETTA, L. B.; PERRY, I. S.; SOUZA, G. C.; CLAUSELL, N. O. Phase angle and mortality: a systematic review. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 73, n. 4, p. 495-508, 2019. [CrossRef]

- KAWATA, S.; BOOKA, E.; HONKE, J.; HANEDA, R.; SONEDA, W.; MURAKAMI, T.; et al. Relationship of phase angle with postoperative pneumonia and survival prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Nutrition, v. 135, 112743, 2025. [CrossRef]

- YAMANAKA, A.; YASUI-YAMADA, S.; FURUMOTO, T.; KUBO, M.; HAYASHI, H.; KITAO, M.; et al. Association of phase angle with muscle function and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy. Nutrition, v. 103-104, 111798, 2022. [CrossRef]

- OLIVEIRA, N. D. S.; CRUZ, M. L. S.; OLIVEIRA, R. S.; REIS, T. G.; OLIVEIRA, M. C.; BESSA JÚNIOR, J. Phase angle is a predictor of overall 5-year survival after head and neck cancer surgery. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, v. 90, n. 6, 101482, 2024. [CrossRef]

- HUI, D.; DEV, R.; PIMENTAL, L.; PARK, M.; CERANA, M. A.; LIU, D.; BRUERA, E. Association between multi-frequency phase angle and survival in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, v. 53, n. 3, p. 571-577, 2017. [CrossRef]

- DAVIS, M. P.; YAVUZSEN, T.; KHOSHKNABI, D.; KIRKOVA, J.; WALSH, D.; LASHEEN, W.; et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle changes during hydration and prognosis in advanced cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care, v. 26, n. 3, p. 180-187, 2009. [CrossRef]

- SHI, J.; XIE, H.; RUAN, G.; GE, Y.; LIN, S.; ZHANG, H.; et al. Sex differences in the association of phase angle and lung cancer mortality. Frontiers in Nutrition, v. 9, 1061996, 2022. [CrossRef]

- GRUNDMANN, O.; YOON, S. L.; WILLIAMS, J. J. The value of bioelectrical impedance analysis and phase angle in the evaluation of malnutrition and quality of life in cancer patients – a comprehensive review. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 69, n. 12, p. 1290-1297, 2015. [CrossRef]

- OZORIO, G. A.; BARÃO, K.; FORONES, N. M. Cachexia stage, patient-generated subjective global assessment, phase angle, and handgrip strength in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Nutrition and Cancer, v. 69, n. 5, p. 772-779, 2017. [CrossRef]

- SEHOULI, J.; MUELLER, K.; RICHTER, R.; ANKER, M.; WOOPEN, H.; RASCH, J.; et al. Effects of sarcopenia and malnutrition on morbidity and mortality in gynecologic cancer surgery: results of a prospective study. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, v. 12, n. 2, p. 393-402, 2021. [CrossRef]

- DEL OLMO-GARCÍA, M.; HERNANDEZ-RIENDA, L.; GARCIA-CARBONERO, R.; HERNANDO, J.; CUSTODIO, A.; ANTON-PASCUAL, B.; et al. Nutritional status and quality of life of patients with advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms in Spain: the NUTRIGETNE (GETNE-S2109) study. Oncologist, v. 30, n. 2, oyae343, 2025. [CrossRef]

- HÄRTER, J.; ORLANDI, S. P.; BIELEMANN, R. M.; DOS SANTOS, L. P.; GONZALEZ, M. C. Standardized phase angle: relationship with functionality, muscle mass and postoperative outcomes in surgical cancer patients. Medical Oncology, v. 41, n. 6, p. 139, 2024. [CrossRef]

- DO AMARAL PAES, T. C.; DE OLIVEIRA, K. C. C.; DE CARVALHO PADILHA, P.; PERES, W. A. F. r: angle assessment in critically ill cancer patients.

- KUTZ, L. M.; ABEL, J.; SCHWEIZER, D.; TRIBIUS, S.; KRÜLL, A.; PETERSEN, C.; LÖSER, A. Quality of life, HPV-status and phase angle predict survival in head and neck cancer patients under (chemo)radiotherapy undergoing nutritional intervention. Radiotherapy and Oncology, v. 166, p. 145-153, 2022. [CrossRef]

- EYİGÖR, S.; APAYDIN, S.; YESIL, H.; TANIGOR, G.; HOPANCI BICAKLI, D. Effects of yoga on phase angle and quality of life in patients with breast cancer: a randomized, single-blind, controlled trial. Complementary Medicine Research, v. 28, n. 6, p. 523-532, 2021. [CrossRef]

- RAMOS DA SILVA, B.; MIALICH, M. S.; CRUZ, L. P.; RUFATO, S.; GOZZO, T.; JORDAO, A. A. Performance of functionality measures and phase angle in women exposed to chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, v. 42, p. 105-116, 2021. [CrossRef]

- SÁNCHEZ-LARA, K.; TURCOTT, J. G.; JUÁREZ, E.; GUEVARA, P.; NÚÑEZ-VALENCIA, C.; OÑATE-OCAÑA, L. F.; et al. Association of nutrition parameters including bioelectrical impedance and systemic inflammatory response with quality of life and prognosis in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Nutrition and Cancer, v. 64, n. 4, p. 526-534, 2012. [CrossRef]

- NORMAN, K.; STÜBLER, D.; BAIER, P.; SCHÜTZ, T.; OCRAN, K.; HOLM, E.; et al. Effects of creatine supplementation on nutritional status, muscle function and quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer: a double blind randomised controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition, v. 25, n. 4, p. 596-605, 2006. [CrossRef]

- OSAKI, K.; MORISHITA, S.; KAMIMURA, A.; TAKAMI, S.; SHINDO, A.; KIDO, K.; et al. Associations between skeletal muscle mass, physical function, and quality of life at diagnosis in patients with hematological malignancies. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho, v. 51, n. 1, p. 53-57, 2024. [PubMed]

- CACCIALANZA, R.; CEREDA, E.; KLERSY, C.; MILANI, P.; CAPPELLO, S.; MARTINELLI, V.; et al. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis-derived phase angle predicts survival in patients with systemic immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis. Amyloid, v. 27, n. 3, p. 168-173, 2020. [CrossRef]

- WEHRLE, A.; KNEIS, S.; DICKHUTH, H. H.; GOLLHOFER, A.; BERTZ, H. Endurance and resistance training in patients with acute leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy: a randomized pilot study. Supportive Care in Cancer, v. 27, n. 3, p. 1071-1079, 2019. [CrossRef]

- COMPANY-SE G, NESCOLARDE L, PAJARES V, TORREGO A, RAFECAS A, ROSELL J, RIU PJ, BRAGOS R. Relaxation differences using EIS through bronchoscopy of healthy and pathological lung tissue. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2023 Jul;2023:1-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAŁECKA-MASSALSKA, T.; et al. Bioimpedance vector pattern in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, v. 63, n. 1, p. 101-104, 2012. Disponível em: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&id=L364537706. Acesso em: 21 out. 2025.

- CARDOSO, I. C. R.; AREDES, M. A.; CHAVES, G. V. Applicability of the direct parameters of bioelectrical impedance in assessing nutritional status and surgical complications of women with gynecological cancer. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, v. 71, n. 11, p. 1278-1284, 2017. [CrossRef]

- MAŁECKA-MASSALSKA, T. , SMOLEŃ, A.; MORSHE D, K. Body composition analysis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, v. 271, n. 10, p. 2775-2779, 2014. [CrossRef]

- PAIVA, S. I.; BORGES, L. R.; HALPERN-SILVEIRA, D.; ASSUNÇÃO, M. C. F.; BARROS, A. J. D.; GONZALEZ, M. C. Standardized phase angle from bioelectrical impedance analysis as prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, v. 19, n. 2, p. 187-192, 2011. [CrossRef]

- BEAM Study Group. A Pilot Study to Determine the Effectiveness of Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis as a Clinical Assessment Tool of Nutrition Status in Glioblastoma Multiforme Patients (The BEAM Study). ClinicalTrials.gov, 2012. Disponível em: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01770626. Acesso em: 21 out. 2025.

- MAŁECKA-MASSALSKA, T.; SMOLEŃ, A.; MORSHE D, K. Altered tissue electrical properties in squamous cell carcinoma in head and neck tumors: Preliminary observations. Head & Neck, v. 35, n. 8, p. 1101-1105, 2013. [CrossRef]

- MORSHED, K.; MLAK, R.; SMOLEŃ, A. Application of bioelectrical impedance analysis in monitoring patients with head and neck cancer after surgical intervention. Otolaryngologia Polska, v. 77, n. 2, p. 18-23, 2023. [CrossRef]

- NAVIGANTE, A.; CRESTA MORGADO, P.; CASBARIEN, O.; LÓPEZ DEL GADO, N.; GIGLIO, R.; PERMAN, M. Relationship between weakness and phase angle in advanced cancer patients with fatigue. Supportive Care in Cancer, v. 21, n. 6, p. 1685-1690, 2013. [CrossRef]

- AXELSSON, L.; SILANDER, E.; BOSAEUS, I.; HAMMERLID, E. Bioelectrical phase angle at diagnosis as a prognostic factor for survival in advanced head and neck cancer. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, v. 275, n. 9, p. 2379-2386, 2018. [CrossRef]

- BÜNTZEL, J.; MICKE, O.; KISTERS, K.; BÜNTZEL, H.; MÜCKE, R. Malnutrition and survival – bioimpedance data in head neck cancer patients. In Vivo, v. 33, n. 3, p. 979-982, 2019. [CrossRef]

- EMIR, K. N.; DEMİREL, B.; ATASOY, B. M. An Investigation of the Role of Phase Angle in Malnutrition Risk Evaluation and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck or Brain Tumors Undergoing Radiotherapy. Nutrition and Cancer, v. 76, n. 3, p. 252-261, 2024. [CrossRef]

- HERRERA-MARTÍNEZ, A. D.; PRIOR-SÁNCHEZ, I.; FERNÁNDEZ-SOTO, M. L.; GARCÍA-OLIVARES, M.; NOVO-RODRÍGUEZ, C.; GONZÁLEZ-PACHECO, M.; MARTÍNEZ-RAMÍREZ, M. J.; CARMONA-LLANOS, A.; JIMÉNEZ-SÁNCHEZ, A.; MUÑOZ-JIMÉNEZ, C.; TORRES-FLORES, F.; FERNÁNDEZ-JIMÉNEZ, R.; BOUGHANEM, H.; DEL GALINDO-GALLARDO, M. C.; LUENGO-PÉREZ, L. M.; MOLINA-PUERTA, M. J.; GARCÍA-ALMEIDA, J. M. Improving the nutritional evaluation in head neck cancer patients using bioelectrical impedance analysis: Not only the phase angle matters. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, v. 15, n. 6, p. 2426-2436, dez. 2024. [CrossRef]

- SILVA-PAIVA, S. I.; et al. Phase angle cutoff value as a marker of the health status and functional capacity in breast cancer survivors. Physiology & Behavior, v. 235, p. 113400, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- YU, B.; PARK, K. B.; PARK, J. Y.; LEE, S. S.; KWON, O. K.; CHUNG, H. Y. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis for Prediction of Early Complications after Gastrectomy in Elderly Patients with Gastric Cancer: the Phase Angle Measured Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis. Journal of Gastric Cancer, v. 19, n. 3, p. 278-289, 2019. [CrossRef]

- ROH, S.; KOSHIMA, I.; ANO, T.; et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in patients with breast-cancer-related lymphedema before and after lymphaticovenular anastomosis. Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, v. 11, n. 2, p. 404-410, 2023. [CrossRef]

- LUNDBERG, M.; DICKINSON, A.; NIKANDER, P.; ORELL, H.; MÄKITIE, A. Low-phase angle in body composition measurements correlates with prolonged hospital stay in head and neck cancer patients. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, v. 139, n. 4, p. 383-387, 2019. [CrossRef]

- CAI, B.; LUO, L.; ZHU, C.; MENG, L.; SHEN, Q.; FU, Y.; WANG, M.; CHEN, S. Influence of body composition assessment with bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in cancer patients undergoing surgery. Frontiers in Oncology, v. 13, p. 1132972, 2023. [CrossRef]

- GUPTA, D.; LAMMERSFELD, C. A.; VASHI, P. G.; KING, J.; DAHLK, S. L.; GRUTSCH, J. F.; LIS, C. G. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle as a prognostic indicator in breast cancer. BMC Cancer, v. 8, art. 249, 27 ago. 2008. [CrossRef]

- SÁNCHEZ-LARA, K.; et al. A Prospective Randomized Trial: Effect of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) and Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA)-Containing Supplement on the Nutritional and Inflammatory Status, Quality of Life, Toxicity and Response Rate to First-line Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov, 2010. Disponível em: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01048970. Acesso em: 21 out. 2025.

- GUTIÉRREZ-SANTAMARÍA, B.; MARTINEZ AGUIRRE-BETOLAZA, A.; GARCÍA-ÁLVAREZ, A.; ARIETALEANIZBEASKOA, M. S.; MENDIZABAL-GALLASTEGUI, N.; GRANDES, G.; CASTAÑEDA-BABARRO, A.; COCA, A. Association between PhA and Physical Performance Variables in Cancer Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 20, n. 2, p. 1145, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]