Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

1.2. Clinical and Sociodemographic Data

1.3. Anthropometric Measurements

1.4. Nutritional Screening and Diagnosis of Malnutrition

1.5. Morphofunctional Assessment

1.5.1. Bioelectrical Impedance Vector Analysis (BIVA)

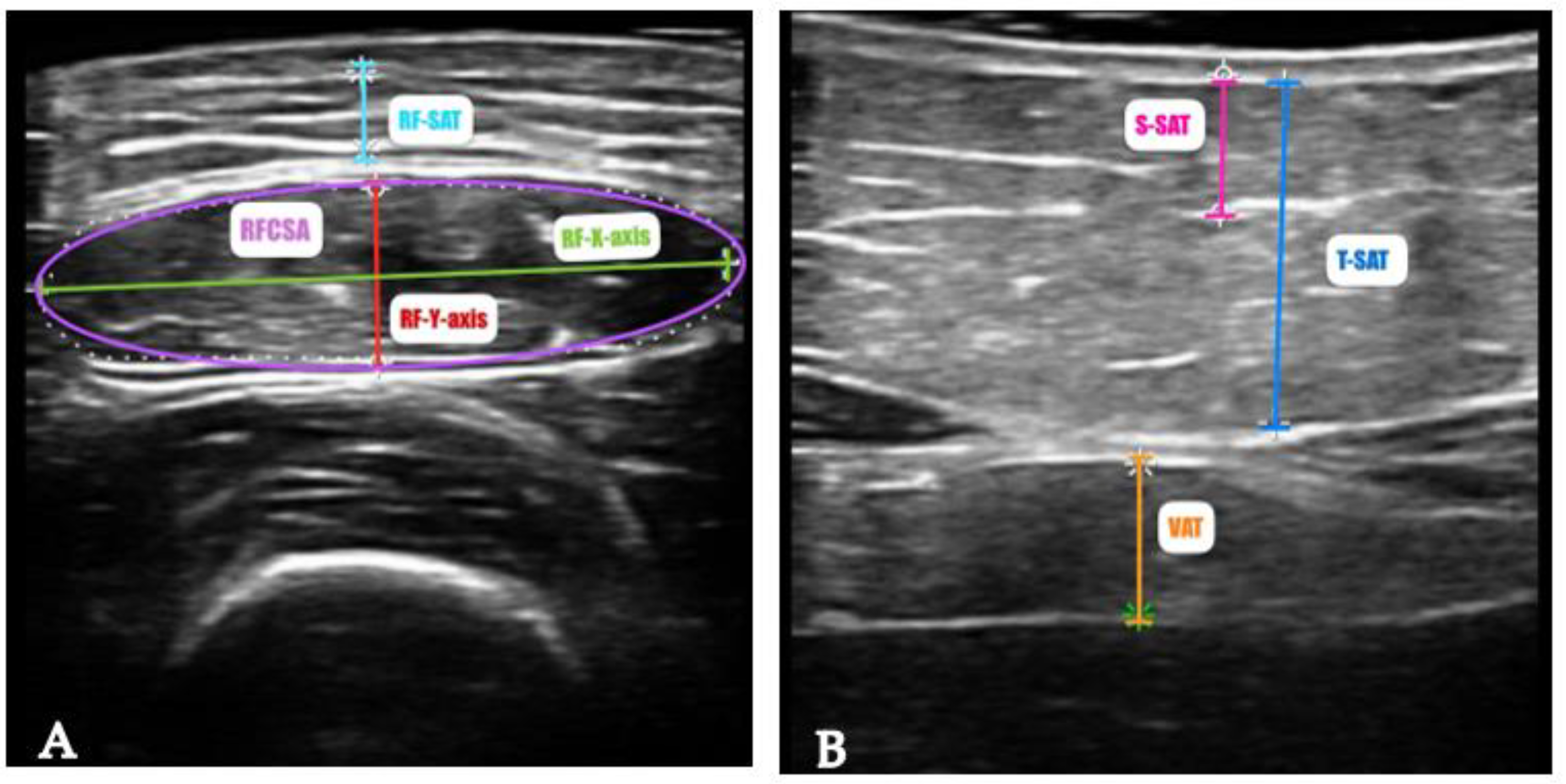

1.5.2. Nutritional Ultrasound (NU)®

1.5.3. Functional and Muscle Strength Assessment

1.6. Assessment and Diagnosis of Sarcopenia

1.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Participants Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shi, L.; He, X.; Luo, Y. Gastrointestinal Cancers in China, the USA, and Europe. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2021, 9, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardim, S.R.; de Souza, L.M.P.; de Souza, H.S.P. The Rise of Gastrointestinal Cancers as a Global Phenomenon: Unhealthy Behavior or Progress? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, F.; Martos, C.; Bettio, M.; Negrão Carvalho, R.; Zorzi, M.; Guzzinati, S.; Rugge, M. Geographical and Temporal Differences in Gastric and Oesophageal Cancer Registration by Subsite and Morphology in Europe. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1250107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahed, S.; Norouzy, A.; Motlagh, A.G.; Eslami, S.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Emadzadeh, M.; Nematy, M.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Tabrizi, F.V.; Bozzetti, F.; Toussi, M.S. Nutritional Status in Patients with Esophageal Cancer Receiving Chemoradiation and Assessing the Efficacy of Usual Care for Nutritional Managements. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2020, 21, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajani, J.A.; D’Amico, T.A.; Bentrem, D.J.; Cooke, D.; Corvera, C.; Das, P.; Enzinger, P.C.; Enzler, T.; Farjah, F.; Gerdes, H.; Gibson, M.; Grierson, P.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Ilson, D.H.; Jalal, S.; Keswani, R.N.; Kim, S.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Klempner, S.; Lacy, J.; Licciardi, F.; Ly, Q.P.; Matkowskyj, K.A.; McNamara, M.; Miller, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Mulcahy, M.F.; Outlaw, D.; Perry, K.A.; Pimiento, J.; Poultsides, G.A.; Reznik, S.; Roses, R.E.; Strong, V.E.; Su, S.; Wang, H.L.; Wiesner, G.; Willett, C.G.; Yakoub, D.; Yoon, H.; McMillian, N.R.; Pluchino, L.A. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023, 21, 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöll, E.; Amann, A.; Eisterer, W.; Gerger, A.; Grünberger, B.; Rumpold, H.; Weiss, L.; Winder, T.; Greil, R.; Prager, G.W. Treatment Algorithm for Patients With Gastric Adenocarcinoma: Austrian Consensus on Systemic Therapy-An Update. Anticancer Res 2023, 43, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasco, P.; Monteiro-Grillo, I.; Marques Vidal, P.; Camilo, M.E. Cancer: Disease and Nutrition Are Key Determinants of Patients’ Quality of Life. Support Care Cancer 2004, 12, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Mastnak, D.M.; Palamar, N.; Kozjek, N.R. Nutritional Therapy for Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Nutr Cancer 2018, 70, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, S.J.; Mozer, M. Differentiating Sarcopenia and Cachexia Among Patients With Cancer. Nutr Clin Pract 2017, 32, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.; Samaden, M.; Ruggieri, E.; Vénéreau, E. Cancer Cachexia as a Multiorgan Failure: Reconstruction of the Crime Scene. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 960341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Poulin, P.; Feldstain, A.; Chasen, M.R. The Association between Malnutrition and Psychological Distress in Patients with Advanced Head-and-Neck Cancer. Curr Oncol 2013, 20, e554-60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Laird, B.; Larsson, M.; Laviano, A.; Mühlebach, S.; Muscaritoli, M.; Oldervoll, L.; Ravasco, P.; Solheim, T.; Strasser, F.; de van der Schueren, M.; Preiser, J.C. ESPEN Guidelines on Nutrition in Cancer Patients. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Lucia, S.; Farcomeni, A.; Lorusso, V.; Saracino, V.; Barone, C.; Plastino, F.; Gori, S.; Magarotto, R.; Carteni, G.; Chiurazzi, B.; Pavese, I.; Marchetti, L.; Zagonel, V.; Bergo, E.; Tonini, G.; Imperatori, M.; Iacono, C.; Maiorana, L.; Pinto, C.; Rubino, D.; Cavanna, L.; Di Cicilia, R.; Gamucci, T.; Quadrini, S.; Palazzo, S.; Minardi, S.; Merlano, M.; Colucci, G.; Marchetti, P.; Fioretto, L.; Cipriani, G.; Barni, S.; Lonati, V.; Frassoldati, A.; Surace, G.C.; Porzio, G.; Martella, F.; Altavilla, G.; Santarpia, M.C.; Pronzato, P.; Levaggi, A.; Contu, A.; Contu, M.; Adamo, V.; Berenato, R.; Marchetti, F.; Pellegrino, A.; Violante, S.; Guida, M. Prevalence of Malnutrition in Patients at First Medical Oncology Visit: The PreMiO Study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 79884–79896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.R.; Laird, B.J.A.; Wigmore, S.J.; Skipworth, R.J.E. Understanding Cancer Cachexia and Its Implications in Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2022, 23, 1732–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.R.; Livingstone, K.M.; Daly, R.M.; Marchese, L.E.; Kiss, N. Associations between Dietary Patterns and Malnutrition, Low Muscle Mass and Sarcopenia in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, P.; Delrio, P.; Mascheroni, A.; Zanetti, M. The Spectrum of Malnutrition/Cachexia/Sarcopenia in Oncology According to Different Cancer Types and Settings: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J. Malnutrition in Cancer Patients: Causes, Consequences and Treatment Options. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024, 50, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soom, T.; El Bakkali, S.; Gebruers, N.; Verbelen, H.; Tjalma, W.; van Breda, E. The Effects of Chemotherapy on Energy Metabolic Aspects in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Clinical Nutrition 2020, 39, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.U.; Fan, G.H.; Hastie, D.J.; Addonizio, E.A.; Han, J.; Prakasam, V.N.; Karagozian, R. The Clinical Impact of Malnutrition on the Postoperative Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: Propensity Score Matched Analysis of 2011-2017 Hospital Database. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 46, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, A.F.; Chong, L.; Read, M.; Hii, M.W. Economic Burden of Complications and Readmission Following Oesophageal Cancer Surgery. ANZ J Surg 2022, 92, 2901–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giorno, R.; Quarenghi, M.; Stefanelli, K.; Rigamonti, A.; Stanglini, C.; De Vecchi, V.; Gabutti, L. Phase Angle Is Associated with Length of Hospital Stay, Readmissions, Mortality, and Falls in Patients Hospitalized in Internal-Medicine Wards: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Nutrition 2021, 85, 111068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Gajete-Martín, L.M.; Pintor-De-la-maza, B.; González-Arnáiz, E.; González-Roza, L.; García-Pérez, M.P.; González-Alonso, V.; García-González, M.A.; de Prado-Espinosa, R.; Cuevas, M.J.; Fernández-Perez, E.; Mostaza-Fernández, J.L.; Cano-Rodríguez, I. Disease-Related Malnutrition and Sarcopenia Predict Worse Outcome in Medical Inpatients: A Cohort Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; Crivelli, A.; Evans, D.C.; Gramlich, L.; Fuchs-Tarlovsky, V.; Keller, H.; Llido, L.; Malone, A.; Mogensen, K.M.; Morley, J.E.; Muscaritoli, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Pirlich, M.; Pisprasert, V.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Siltharm, S.; Singer, P.; Tappenden, K.; Velasco, N.; Waitzberg, D.; Yamwong, P.; Yu, J.; Van Gossum, A.; Compher, C.; Jensen, G.L.; Charlene, C.; Cederholm, T.; Van Gossum, A.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Fuchs, V. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition - A Consensus Report from the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; Schneider, S.M.; Sieber, C.C.; Topinkova, E.; Vandewoude, M.; Visser, M.; Zamboni, M.; Bautmans, I.; Baeyens, J.P.; Cesari, M.; Cherubini, A.; Kanis, J.; Maggio, M.; Martin, F.; Michel, J.P.; Pitkala, K.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D.; Schols, J. Sarcopenia: Revised European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokura, Y.; Nishioka, S.; Maeda, K.; Wakabayashi, H. Ultrasound Utilized by Registered Dietitians for Body Composition Measurement, Nutritional Assessment, and Nutritional Management. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 57, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, A.; D’Alessandro, C.; Regolisti, G.; di Mario, F.; Guglielmi, G.; Bazzocchi, A.; Fiaccadori, E. Muscle Mass Assessment in Renal Disease: The Role of Imaging Techniques. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2020, 10, 1672–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, J.; Foletto, E.; Cardoso, R.C.B.; Garbelotto, C.; Frenzel, A.P.; Carneiro, J.U.; Carpes, L.S.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Silva, F.M. Ultrasound for Measurement of Skeletal Muscle Mass Quantity and Muscle Composition/Architecture in Critically Ill Patients: A Scoping Review on Studies’ Aims, Methods, and Findings. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrinato Miola, T.; Santos Da Conceição, E.L.; De Oliveira Souza, J.; Vieira Barbosa, P.N.; José, F.; Coimbra, F.; Galvão, A.; Bitencourt, V. CT Assessment of Nutritional Status and Lean Body Mass in Gastric and Esophageal Cancer. Applied Cancer Research 2018 38:1 2018, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, T.; Souza, J.D.O.; Santos, M.C.; Gross, J.L.; Couto, N.L.; Bitencourt, A.G.V. Comparison between Nutritional Assessment and Computed Tomography Analysis of Muscle Mass in Patients with Lung Cancer. Braspen J 2021, 36, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.R.; Orsso, C.E.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Sicchieri, J.M.F.; Mialich, M.S.; Jordao, A.A.; Prado, C.M. Phase Angle and Cellular Health: Inflammation and Oxidative Damage. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 24, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukaski, H.C.; Kyle, U.G.; Kondrup, J. Assessment of Adult Malnutrition and Prognosis with Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis: Phase Angle and Impedance Ratio. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2017, 20, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Pirlich, M.; Bosy-Westphal, A. Bioelectrical Phase Angle and Impedance Vector Analysis--Clinical Relevance and Applicability of Impedance Parameters. Clin Nutr 2012, 31, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.G.; Mateus, C.; Capelas, M.L.; Pimenta, N.; Santos, T.; Mäkitie, A.; Ganhão-Arranhado, S.; Trabulo, C.; Ravasco, P. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) for the Assessment of Body Composition in Oncology: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, D.; García-García, C.; Talluri, A.; Lukaski, H.C.; García-Almeida, J.M. Future Lines of Research on Phase Angle: Strengths and Limitations. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2023, 24, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Herpich, C.; Müller-Werdan, U. Role of Phase Angle in Older Adults with Focus on the Geriatric Syndromes Sarcopenia and Frailty. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2023, 24, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Pirlich, M.; Bosy-Westphal, A. Bioelectrical Phase Angle and Impedance Vector Analysis – Clinical Relevance and Applicability of Impedance Parameters. Clinical Nutrition 2012, 31, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijholt, W.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Raj, I.S.; van der Schans, C.P.; Hobbelen, H. Reliability and Validity of Ultrasound to Estimate Muscles: A Comparison between Different Transducers and Parameters. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020, 35, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Bunout, D.; Barrera, G.; de la Maza, M.P.; Henriquez, S.; Leiva, L.; Hirsch, S. Rectus Femoris (RF) Ultrasound for the Assessment of Muscle Mass in Older People. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015, 61, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Liu, P.T.; Chiang, H.K.; Lee, S.H.; Lo, Y.L.; Yang, Y.C.; Chiou, H.J. Ultrasound Measurement of Rectus Femoris Muscle Parameters for Discriminating Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Adults. J Ultrasound Med 2022, 41, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, V.A.; Oliveira, D.; Cupolilo, E.N.; Miranda, C.S.; Colugnati, F.A.B.; Mansur, H.N.; Fernandes, N.M. da S.; Bastos, M.G. Rectus Femoris Muscle Mass Evaluation by Ultrasound: Facilitating Sarcopenia Diagnosis in Pre-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Stages. Clinics. [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, J.; Héréus, S.; Cattrysse, E.; Raeymaekers, H.; De Maeseneer, M.; Scafoglieri, A. Reliability of Muscle Quantity and Quality Measured With Extended-Field-of-View Ultrasound at Nine Body Sites. Ultrasound Med Biol 2023, 49, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nies, I.; Ackermans, L.L.G.C.; Poeze, M.; Blokhuis, T.J.; Ten Bosch, J.A. The Diagnostic Value of Ultrasound of the Rectus Femoris for the Diagnosis of Sarcopenia in Adults: A Systematic Review. Injury 2022, 53, S23–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijholt, W.; Scafoglieri, A.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Hobbelen, J.S.M.; van der Schans, C.P. The Reliability and Validity of Ultrasound to Quantify Muscles in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, C.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Rioja-Vázquez, R.; Cornejo-Pareja, I.; Tinahones, F.J.; García-Almeida, J.M. Rectus Femoris Muscle and Phase Angle as Prognostic Factor for 12-Month Mortality in a Longitudinal Cohort of Patients with Cancer (AnyVida Trial). Nutrients 2023, 15, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón-Frapolli, V.J.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Cornejo-Pareja, I.M.; Sánchez-García, A.M.; Martínez-López, P.; Nuevo-Ortega, P.; Reina-Artacho, C.; Estecha-Foncea, M.A.; Gómez-González, A.M.; González-Jiménez, M.B.; Avanesi-Molina, E.; Tinahones-Madueño, F.J.; García-Almeida, J.M. Phase Angle and Rectus Femoris Cross-Sectional Area as Predictors of Severe Malnutrition and Their Relationship with Complications in Outpatients with Post-Critical SARS-CoV2 Disease. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1218266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Yan, L.; Tong, R.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Hou, G. Ultrasound Assessment of the Rectus Femoris in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Predicts Sarcopenia. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022, 17, 2801–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.-L.; Hsieh, B.-Y.; Rong, M.; Tay, J.; Kong, K.H. Ultrasound Measurements of Rectus Femoris and Locomotor Outcomes in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Life 2022, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, T.L.N.; Soares, J.D.P.; Borges, T.C.; Pichard, C.; Pimentel, G.D. Phase Angle Is Not Associated with Fatigue in Cancer Patients: The Hydration Impact. Eur J Clin Nutr 2020, 74, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Lagergren, J.; Blomberg, J.; Johar, A.; Bosaeus, I.; Lagergren, P. Phase Angle as a Prognostic Marker after Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) in a Prospective Cohort Study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016, 51, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, C.N.; Cavaco-Silva, J.; Reis, M.; Campa, F.; Toselli, S.; Sardinha, L.; Silva, A.M. Phase Angle as a Marker of Muscular Strength in Breast Cancer Survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, N.P.; Gomes, T.L.N.; Barreto, C.S.; Borges, T.C.; Soares, J.D.P.; Pichard, C.; Laviano, A.; Pimentel, G.D. Low Phase Angle Is Associated with the Risk for Sarcopenia in Unselected Patients with Cancer: Effects of Hydration. Nutrition 2021, 84, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomachi, J.; Fukuda, T.; Mizushima, Y.; Nozawa, N.; Ishizaka, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Kambe, T.; Inoue, S.; Nishikawa, K.; Toyama, Y.; Takahashi, R.; Arakawa, T.; Yagi, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Ugata, Y.; Nakamura, F.; Sakuma, M.; Abe, S.; Fujita, H.; Mizushima, T.; Toyoda, S.; Nakajima, T. Clinical Usefulness of Phase Angle as an Indicator of Muscle Wasting and Malnutrition in Inpatients with Cardiovascular Diseases. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2023, 32, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui-Yamada, S.; Oiwa, Y.; Saito, Y.; Aotani, N.; Matsubara, A.; Matsuura, S.; Tanimura, M.; Tani-Suzuki, Y.; Kashihara, H.; Nishi, M.; Shimada, M.; Hamada, Y. Impact of Phase Angle on Postoperative Prognosis in Patients with Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Cancer. Nutrition 2020, 79–80, 110891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulin, J.; Ipavic, E.; Mastnak, D.M.; Brecelj, E.; Edhemovic, I.; Kozjek, N.R. Phase Angle as a Prognostic Indicator of Surgical Outcomes in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Radiol Oncol 2023, 57, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulin, J.; Ipavic, E.; Mastnak, D.M.; Brecelj, E.; Edhemovic, I.; Kozjek, N.R. Phase Angle as a Prognostic Indicator of Surgical Outcomes in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Radiol Oncol 2023, 57, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde Frio, C.; Härter, J.; Santos, L.P.; Orlandi, S.P.; Gonzalez, M.C. Phase Angle, Physical Quality of Life and Functionality in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 57, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sember, V.; Meh, K.; Sorić, M.; Jurak, G.; Starc, G.; Rocha, P. Validity and Reliability of International Physical Activity Questionnaires for Adults across EU Countries: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanden-Berghe, C. Valoración antropométrica. In Valoración nutricional en el anciano. Recomendaciones prácticas de los expertos en geriatría y nutrición (SENPE y SEGG); Galénitas-Nigra Trea: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M.C.; Mehrnezhad, A.; Razaviarab, N.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Heymsfield, S.B. Calf Circumference: Cutoff Values from the NHANES 1999-2006. Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 113, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detsky, A.S.; Mclaughlin, J.; Baker, J.P.; Johnston, N.; Whittaker, S.; Mendelson, R.A.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N. What Is Subjective Global Assessment of Nutritional Status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1987, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, L.M.; Lee, G.; Ackerie, A.; van der Meij, B.S. Malnutrition Screening and Assessment in the Cancer Care Ambulatory Setting: Mortality Predictability and Validity of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment Short Form (PG-SGA SF) and the GLIM Criteria. Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 2287 2020, 12, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, B.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y.; Hu, H.; Luo, B.; Li, Z. Comparison of Different Methods for Nutrition Assessment in Patients with Tumors. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C.; Bolonchuk, W.W.; Hall, C.B.; Siders, W.A. Validation of Tetrapolar Bioelectrical Impedance Method to Assess Human Body Composition. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986, 60, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artero, A.; Sáez Ramírez, T.; Muresan, B.T.; Ruiz-Berjaga, Y.; Jiménez-Portilla, A.; Sánchez-Juan, C.J. The Effect of Fasting on Body Composition Assessment in Hospitalized Cancer Patients. Nutr Cancer 2023, 75, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Almeida, J.M.; García-García, C.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Ballesteros Pomar, M.D.; Cornejo-Pareja, I.M.; Fernández Medina, B.; de Luis Román, D.A.; Bellido Guerrero, D.; Bretón Lesmes, I.; Tinahones Madueño, F.J. Nutritional Ultrasound®: Conceptualisation, Technical Considerations and Standardisation. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 2023, 70, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampisch, U.S.; Franke, J.; Jedamzik, N.; Hinrichs, T.; Platen, P. Optimal Jamar Dynamometer Handle Position to Assess Maximal Isometric Hand Grip Strength in Epidemiological Studies. J Hand Surg Am 2012, 37, 2368–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Torralvo, F.J.; Porras, N.; Abuín Fernández, J.; García Torres, F.; Tapia, M.J.; Lima, F.; Soriguer, F.; Gonzalo, M.; Rojo Martínez, G.; Olveira, G. Normative Reference Values for Hand Grip Dynamometry in Spain. Association with Lean Mass. Nutr Hosp 2018, 35, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaría-Peláez, M.; González-Bernal, J.J.; Da Silva-González, Á.; Medina-Pascual, E.; Gentil-Gutiérrez, A.; Fernández-Solana, J.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; González-Santos, J. Validity and Reliability of the Short Physical Performance Battery Tool in Institutionalized Spanish Older Adults. Nursing reports (Pavia, Italy) 2023, 13, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Rodríguez, L.; Szlejf, C.; García-González, A.I.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Cruz-Arenas, E.; Rosas-Carrasco, O. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Spanish-Language Version of the SARC-F to Assess Sarcopenia in Mexican Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013, 14, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Xie, H.; Wei, L.; Ruan, G.; Zhang, H.; Shi, J.; Shi, H. Phase Angle: A Robust Predictor of Malnutrition and Poor Prognosis in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Nutrition 2024, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.X.; Ding, X.; Hou, W.; Wang, C.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X. Phase Angle - A Screening Tool for Malnutrition, Sarcopenia, and Complications in Gastric Cancer. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2024, 59, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, R.; García-Rey, S.; Roque-Cuéllar, M.C.; Fernández-Soto, M.L.; García-Olivares, M.; Novo-Rodríguez, M.; González-Pacheco, M.; Prior-Sánchez, I.; Carmona-Llanos, A.; Muñoz-Jiménez, C.; Zarco-Rodríguez, F.P.; Miguel-Luengo, L.; Boughanem, H.; García-Luna, P.P.; García-Almeida, J.M. Ultrasound Muscle Evaluation for Predicting the Prognosis of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Large-Scale and Multicenter Prospective Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Cui, H.; Zhu, M. Influence of Malnutrition According to the GLIM Criteria on the Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients With Cancer. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 774636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.L.D. Dos; Leite, L.D.O.; Lages, I.C.F. Prevalence of malnutrition, according to the Glim criteria, in patients who are the candidates for gastrointestinal tract surgery. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2022, 35, e1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L. Bin; Shi, M.M.; Huang, Z.X.; Zhang, W.T.; Zhang, H.H.; Shen, X.; Chen, X.D. Impact of Malnutrition Diagnosed Using Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition Criteria on Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Gastric Cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2022, 46, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murnane, L.C.; Forsyth, A.K.; Koukounaras, J.; Shaw, K.; King, S.; Brown, W.A.; Mourtzakis, M.; Tierney, A.C.; Burton, P.R. Malnutrition Defined by GLIM Criteria Identifies a Higher Incidence of Malnutrition and Is Associated with Pulmonary Complications after Oesophagogastric Cancer Surgery, Compared to ICD-10-Defined Malnutrition. J Surg Oncol 2023, 128, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anconina, R.; Ortega, C.; Metser, U.; Liu, Z.A.; Suzuki, C.; McInnis, M.; Darling, G.E.; Wong, R.; Taylor, K.; Yeung, J.; Chen, E.X.; Swallow, C.J.; Bajwa, J.; Jang, R.W.; Elimova, E.; Veit-Haibach, P. Influence of Sarcopenia, Clinical Data, and 2-[18F] FDG PET/CT in Outcome Prediction of Patients with Early-Stage Adenocarcinoma Esophageal Cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2022, 49, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales-Balaguer, N.; Sorribes-Carreras, P.; Morillo Macias, V. Diagnosis of Sarcopenia and Myosteatosis by Computed Tomography in Patients with Esophagogastric and Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lee, C. min; Kang, B.K.; Ha, T.K.; Choi, Y.Y.; Lee, S.J. Sarcopenia Assessed with DXA and CT Increases the Risk of Perioperative Complications in Patients with Gastrectomy. Eur Radiol 2023, 33, 5150–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E.H.; Akbaş, F.; Yardimci, A.H.; Şahin, E. The Effect of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity on Survival in Gastric Cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegels, J.J.W.; Van Vugt, J.L.A.; Reisinger, K.W.; Hulsewé, K.W.E.; Hoofwijk, A.G.M.; Derikx, J.P.M.; Stoot, J.H.M.B. Sarcopenia Is Highly Prevalent in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Gastric Cancer but Not Associated with Worse Outcomes. J Surg Oncol 2015, 112, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Guirado-Peláez, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Boughanem, H.; Tinahones, F.J.; Garcia-Almeida, J.M. Exploratory Assessment of Nutritional Evaluation Tools as Predictors of Complications and Sarcopenia in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Liu, X.L.; Liu, P.; He, Y.W.; Zhao, Y.X.; Zheng, K.; Cui, J.W.; Li, W. The Efficacy of Fat-Free Mass Index and Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index in Cancer Malnutrition: A Propensity Score Match Analysis. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1172610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Martínez, A.D.; Prior-Sánchez, I.; Fernández-Soto, M.L.; García-Olivares, M.; Novo-Rodríguez, C.; González-Pacheco, M.; Martínez-Ramirez, M.J.; Carmona-Llanos, A.; Jiménez-Sánchez, A.; Muñoz-Jiménez, C.; Torres-Flores, F.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Boughanem, H.; del Galindo-Gallardo, M.C.; Luengo-Pérez, L.M.; Molina-Puerta, M.J.; García-Almeida, J.M. Improving the Nutritional Evaluation in Head Neck Cancer Patients Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis: Not Only the Phase Angle Matters. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.Z.; Ruan, G.T.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, W.J.; Zhang, X.; Song, M.M.; Zhang, X.W.; Li, X.R.; Zhang, K.P.; Tang, M.; Li, W.; Shen, X.; Shi, H.P. Extracellular Water to Total Body Water Ratio Predicts Survival in Cancer Patients with Sarcopenia: A Multi-Center Cohort Study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2022, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hida, T.; Ando, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Ito, K.; Tsushima, M.; Kobayakawa, T.; Morozumi, M.; Tanaka, S.; Machino, M.; Ota, K.; Kanbara, S.; Ito, S.; Ishiguro, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Imagama, S. Ultrasound Measurement of Thigh Muscle Thickness for Assessment of Sarcopenia. Nagoya J Med Sci 2018, 80, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, J.J.; Plaar, K.B.S.; Izaola-Jauregui, O.; Primo-Martín, D.; Gómez-Hoyos, E.; Torres-Torres, B.; De Luis-Román, D.A. Muscular Ultrasonography in Morphofunctional Assessment of Patients with Oncological Pathology at Risk of Malnutrition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Y.; Koca, M.; Burkuk, S.; Unsal, P.; Dikmeer, A.; Oytun, M.G.; Bas, A.O.; Kahyaoglu, Z.; Deniz, O.; Coteli, S.; Ileri, I.; Dogu, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Halil, M. The Role of Muscle Ultrasound to Predict Sarcopenia. Nutrition 2022, 101, 111692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Y.; Deniz, O.; Coteli, S.; Unsal, P.; Dikmeer, A.; Burkuk, S.; Koca, M.; Cavusoglu, C.; Dogu, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Halil, M. Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition Criteria with Different Muscle Assessments Including Muscle Ultrasound with Hospitalized Internal Medicine Patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2022, 46, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luis Roman, D.; García Almeida, J.M.; Bellido Guerrero, D.; Guzmán Rolo, G.; Martín, A.; Primo Martín, D.; García-Delgado, Y.; Guirado-Peláez, P.; Palmas, F.; Tejera Pérez, C.; García Olivares, M.; Maíz Jiménez, M.; Bretón Lesmes, I.; Alzás Teomiro, C.M.; Guardia Baena, J.M.; Calles Romero, L.A.; Prior-Sánchez, I.; García-Luna, P.P.; González Pacheco, M.; Martínez-Olmos, M.Á.; Alabadí, B.; Alcántara-Aragón, V.; Palma Milla, S.; Martín Folgueras, T.; Micó García, A.; Molina-Baena, B.; Rendón Barragán, H.; Rodríguez de Vera Gómez, P.; Riestra Fernández, M.; Jiménez Portilla, A.; López-Gómez, J.J.; Pérez Martín, N.; Montero Madrid, N.; Zabalegui Eguinoa, A.; Porca Fernández, C.; Tapia Guerrero, M.J.; Ruiz Aguado, M.; Velasco Gimeno, C.; Herrera Martínez, A.D.; Novo Rodríguez, M.; Iglesias Hernández, N.C.; de Damas Medina, M.; González Navarro, I.; Vílchez López, F.J.; Fernández-Pombo, A.; Olveira, G. Ultrasound Cut-Off Values for Rectus Femoris for Detecting Sarcopenia in Patients with Nutritional Risk. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | All Patients (n=35) | Male (n=26) | Female (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.8 ± 8.8 | 62.2 ± 9.5 | 64.8 ± 6.4 |

| Primary site tumor | |||

| Esophagus | 25 (71.4%) | 21 (80.8%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Gastric | 10 (28.6%) | 5 (19.2%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Tumor stage | |||

| I | 3 (8.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| II | 10 (28.6) | 8 (30.8%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| III | 14 (40%) | 11 (42.3%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| IV | 8 (22.9%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 7 (20%) | 6 (23.1%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| 1 | 8 (22.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| ≥2 | 20 (57.1%) | 14 (53.8%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| Physical Activity | |||

| Low or inactive | 26 (74.3%) | 19 (73.1%) | 7 (77.8%) |

| Medium | 5 (14.3%) | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| High | 4 (11.4%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Treatment | |||

| Only CTx | 8 (22.9%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| CTx and RTx | 4 (11.4%) | 2 (7.7%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Surgery and CTx | 10 (54.3%) | 13 (50%) | 6 (66.7%) |

| Surgery, CTx and RTx | 4 (11.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Variables | All Patients (n=35) | Male (n=26) | Female (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 ± 5.7 | 23.5 ± 5.3 | 22.6 ± 6.9 |

| Underweight | 13 (37.1%) | 9 (34.6%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Normal | 12 (34.3%) | 10 (38.5%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Overweight | 4 (11.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Obesity | 6 (17.1%) | 4 (15.4%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Weight loss within past 6 months (%) | 14.3 ± 7.9 | 14.9 ± 8.3 | 12.3 ± 6.5 |

| <5% | 4 (11.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| 5-10% | 5 (14.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| >10% | 26 (74.3%) | 21 (80.8%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| MAC (cm) | 26.1 ± 5.3 | 23.5 ± 5.3 | 25.2 ± 6.9 |

| CC (cm) | 32.9 ± 4.4 | 33.3 ± 4.5 | 31.9 ± 4.1 |

| Normal | 8 (22.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Low | 27 (77.1%) | 20 (66.9%) | 7 (77.8%) |

| BIVA-derived parameters | |||

| PhA (º) | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.8 |

| ECW/TBW ratio | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.08 |

| TBW/FFM (%) | 69.7 ± 17.6 | 71.1 ± 14.7 | 66.0 ± 24.6 |

| FM (%) | 19.6 ± 12 | 18.7 ± 10.2 | 22.2 ± 16.6 |

| ASMMI (kg/m2) | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.06 | 5.6 ± 0.86 |

| BCM (kg) | 24.9 ± 6.1 | 27.1 ± 5.2 | 18.8 ± 3.9 |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | |||

| RFCSA (cm2) | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.02 | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.87 ± 0.27 | 0.77 ± 0.22 |

| RF-X-axis | 3.65 ± 0.50 | 3.76 ± 0.44 | 3.31 ± 0.55 |

| RF-AT (cm) | 0.41 (0.23 – 0.74) | 0.35 (0.24-0.55) | 0.78 (0.22-1.42) |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: abdominal adipose tissue | |||

| T-SAT (cm | 1.4 (0.5-1.9) | 1.35 (0.47-1.85) | 1.41 (0.82-2.43) |

| S-SAT (cm) | 0.52 (0.28-0.87) | 0.47 (0.26-0.79) | 0.68 (0.35-1.06) |

| VAT (cm) | 0.55 (0.31-0.73) | 0.52 (0.30-0.65) | 0.58 (0.33-0.95) |

| Hand Grip Strength | |||

| HGS (kg) | 27.5 ± 8.4 | 31.1 ± 6.5 | 17.3 ± 2.5 |

| Functional test | |||

| SPPB | 10 (7-11) | 10 (7.7-11.2) | 10 (6.5-10.5) |

| Variables | No malnutrition (n=6) | Moderate malnutrition (n=11) | Severe malnutrition (n=18) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.773 | |||

| Male | 4 (66.7%) | 9 (81.8%) | 13 (72.2%) | |

| Female | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| Age (years) | 60.5 ± 4.8 | 63.3 ± 10.9 | 63.3 ± 8.7 | 0.786 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 5.6 | 25.9 ± 4.8 | 19.6 ± 3.0 | <0.001*** |

| Weight loss within past 6 months (%) | 4.2 ± 4.3 | 14.9 ± 5.5 | 17.3 ± 7.4 | <0.001*** |

| MAC (cm) | 31.0 ± 4.6 | 29.4 ± 4.3 | 22.4 ± 3.0 | <0.001*** |

| CC (cm) | 36.8 ± 5.3 | 34.9 ± 3.5 | 30.3 ± 2.8 | <0.001*** |

| SGA | ||||

| Well nourished (A) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001*** |

| Mild to moderately malnourished (B) | 2 (33.3% | 8 (72.7%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Severely malnourished (C) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | 14 (77.8%) | |

| BIVA-derived parameters | ||||

| PhA (º) | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 1.02 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 0.016* |

| ECW/TBW ratio | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 0.405 |

| TBW/FFM (%) | 62.3 ± 30.3 | 74.3 ± 2.1 | 69.7 ± 17.2 | 0.430 |

| FM (%) | 25.7 ± 13.9 | 21.0 ± 13.6 | 16.7 ± 9.8 | 0.255 |

| ASMMI (kg/m2) | 7.7 ± 1.5 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001*** |

| BCM (kg) | 29.9 ± 4.7 | 27.6 ± 5.6 | 21.7 ± 4.9 | <0.001*** |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | ||||

| RFCSA (cm2) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | <0.001*** |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 0.68 ± 0.18 | <0.001*** |

| RF-X-axis (cm) | 3.64 ± 0.22 | 3.96 ± 0.12 | 3.46 ± 0.11 | 0.030* |

| RF-Adipose tissue (cm) | 0.82 (0.4-1.16) | 0.44 (0.34-1.01) | 0.30 (0.18-0.50) | 0.037* |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: abdominal adipose tissue | ||||

| T-SAT (cm | 2.08 (1.72-2.59) | 1.30 (0.55-2.62) | 1.0 (0.36-1.56) | 0.012* |

| S-SAT (cm) | 1.07 (0.73-1.26) | 0.62 (0.34-0.95) | 0.44 (0.19-0.65) | 0.011* |

| VAT (cm) | 0.63 (0.56-0.97) | 0.62 (0.55-0.93) | 0.34 (0.24-0.48) | 0.004** |

| Variables | No sarcopenia (n=12) | Probable sarcopenia (n=5) | Confirmed sarcopenia (n=8) | Severe sarcopenia (n=10) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.003** | ||||

| Male | 12 (100%) | 1 (20%) | 5 (62.5%) | 8 (80%) | |

| Female | 0 (0%) | 4 (80%) | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (20%) | |

| Age (years) | 57.7 ± 9.4 | 68.8 ± 6.5 | 61.2 ± 6.9 | 67.2 ± 7.1 | 0.021* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 5.2 | 26.9 ± 5.5 | 18.5 ± 3.2 | 20.3 ± 2.6 | <0.001*** |

| MAC (cm) | 30.4 ± 3.8 | 29.2 ± 5.5 | 20.4 ± 2.3 | 23.9 ± 2.4 | <0.001*** |

| CC (cm) | 36.7 ± 4.2 | 33.3 ± 3.4 | 30.3 ± 3.1 | 30.3 ± 2.5 | <0.001*** |

| SARC-F | <0.001*** | ||||

| No risk | 12 (100%) | 2 (40%) | 8 (100%) | 5 (50%) | |

| Sarcopenia risk | 0 (0%) | 3 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (50%) | |

| BIA-derived parameters | |||||

| PhA (º) | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | <0.001*** |

| ECW/TBW ratio | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.550 |

| TBW/FFM (%) | 74.15 ± 1.97 | 60.13 ± 33.3 | 73.4 ± 0.29 | 66.0 ± 24.5 | 0.407 |

| FM (%) | 19.4 ± 12.7 | 25.2 ± 19.1 | 14.2 ± 8.9 | 21.4 ± 8.4 | 0.408 |

| ASMMI (kg/m2) | 7.98 ± 0.95 | 6.73 ± 0.57 | 5.92 ± 0.96 | 6.08 ± 0.69 | <0.001*** |

| BCM (kg) | 30.2 ± 3.6 | 23.5 ± 6.3 | 22.7 ± 6.3 | 21.1 ± 3.9 | <0.001*** |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | |||||

| RFCSA (cm2) | 3.56 ± 0.76 | 2.80 ± 0.60 | 1.82 ± 0.49 | 2.53 ± 1.05 | <0.001*** |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | 1.05 ± 0.22 | 0.86 ± 0.13 | 0.58 ± 0.18 | 0.80 ± 0.21 | <0.001*** |

| RF-AT (cm) | 0.48 (0.36-0.85) | 1.10 (0.28-1.84) | 0.26 (0.15-0.48) | 0.30 (0.18-0.49) | 0.072 |

| RF-X-axis (cm) | 3.79 ± 0.11 | 3.75 ± 0.20 | 3.49 ± 0.99 | 3.55 ± 0.23 | 0.520 |

| Hand Grip Strength | |||||

| HGS (kg) | 35.9 ± 4.9 | 19.5 ± 7.1 | 25.4 ± 5.2 | 23.3 ± 6.2 | <0.001*** |

| Functional test | |||||

| SPPB | 11.5 (10-12) | 10 (7.5-10.5) | 10 (9-10.75) | 6 (5-7.25) | <0.001*** |

| Variables | % weight loss | BMI (kg/m2) | ASMMI (kg/m2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | |

| BIA-derived parameters | ||||||

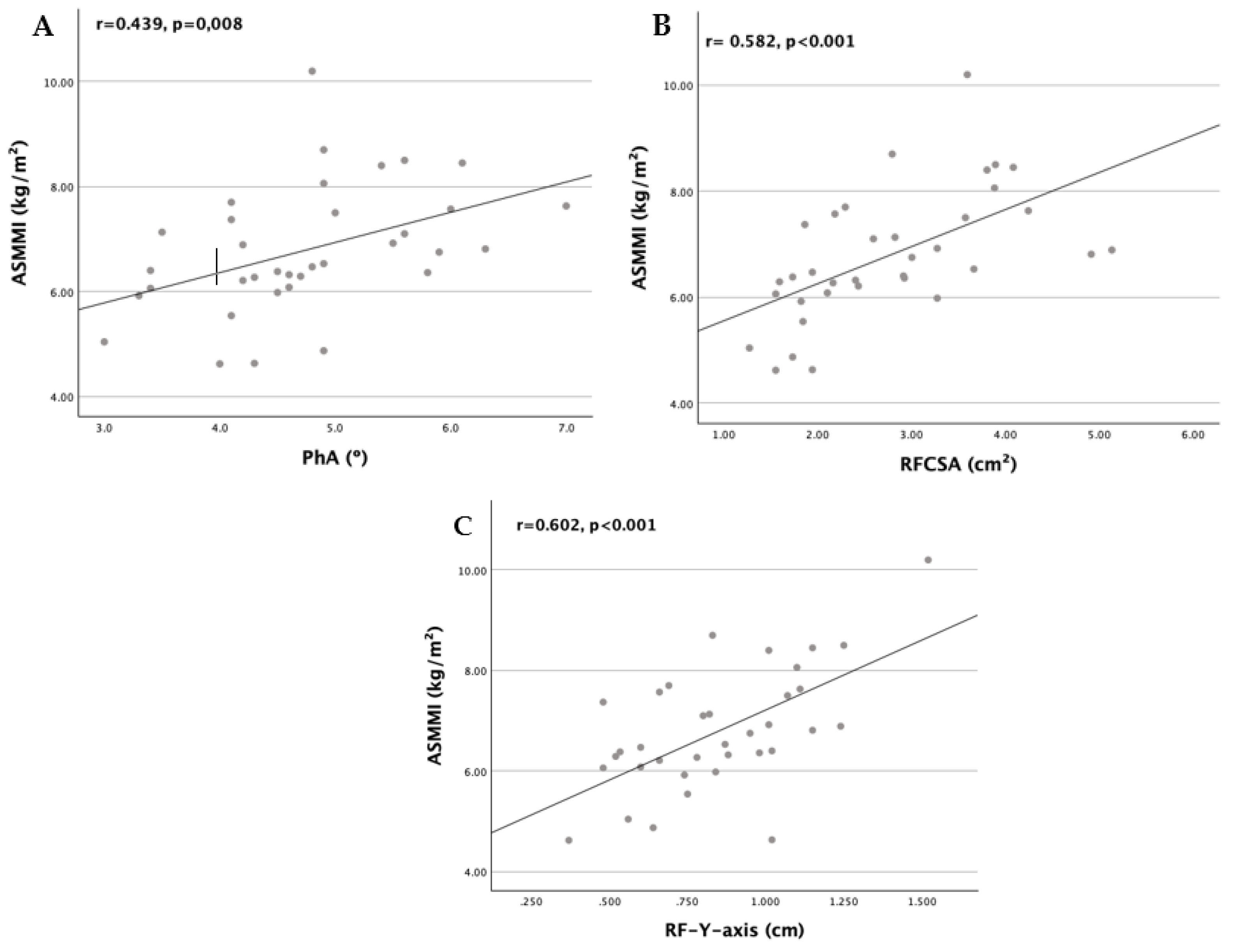

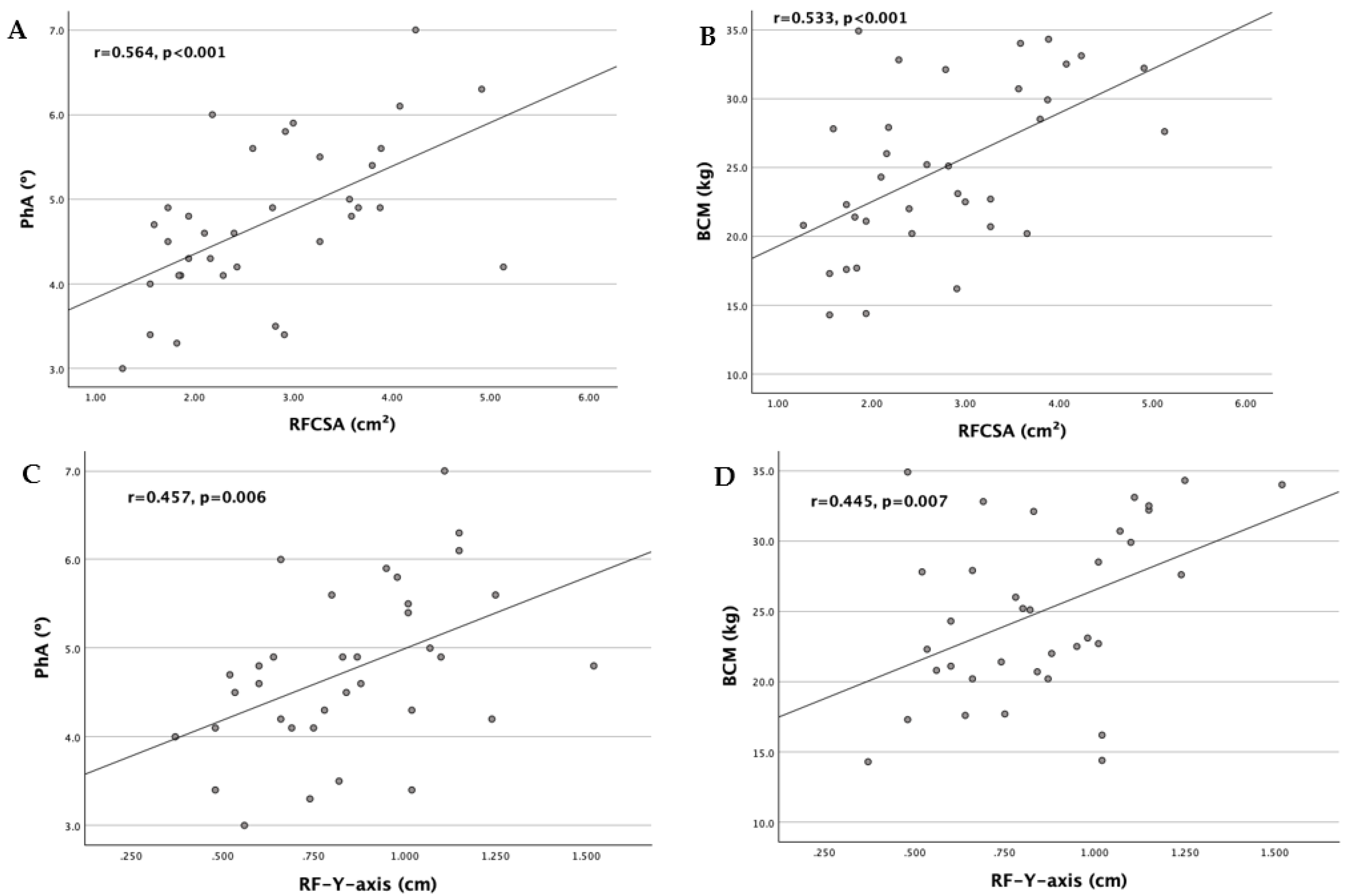

| PhA (º) | -0.093 | 0.596 | 0.288 | 0.094 | 0.439 | 0.008** |

| ECW/TBW ratio | 0.244 | 0.157 | 0.244 | 0.158 | -0.246 | 0.154 |

| TBW/FFM (%) | 0.156 | 0.378 | 0.261 | 0.136 | 0.169 | 0.338 |

| FM (%) | -0.232 | 0.181 | 0.543 | <0.001* | 0.204 | 0.240 |

| BCM (kg) | -0.313 | 0.067 | 0.397 | 0.018* | 0.837 | <0.001*** |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | ||||||

| RFCSA (cm2) | -0.311 | 0.069 | 0.531 | 0.001* | 0.582 | <0.001*** |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | -0.386 | 0.022* | 0.599 | <0.001* | 0.602 | <0.001*** |

| RF-AT (cm) | -0.420 | 0.012* | 0.742 | <0.001* | 0.245 | 0.156 |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: abdominal adipose tissue | ||||||

| T-SAT (cm | -0.491 | 0.005* | 0.826 | <0.001* | 0.399 | 0.026* |

| S-SAT (cm) | -0.459 | 0.009* | 0.799 | <0.001* | 0.416 | 0.020* |

| VAT (cm) | -0.092 | 0.112 | 0.607 | <0.001* | 0.278 | 0.130 |

| Variables | HGS (kg) | ASMMI (kg/m2) | SPPB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p value | R | p value | R | p value | |

| BIA-derived parameters | ||||||

| PhA (º) | 0.556 | <0.001* | 0.439 | 0.008* | 0.475 | 0.004** |

| ECW/TBW ratio | -0.257 | 0.135 | -0.246 | 0.154 | -0.376 | 0.026 |

| TBW/FFM (%) | 0.223 | 0.204 | 0.169 | 0.338 | 0.124 | 0.483 |

| BCM (kg) | 0.751 | <0.001* | 0.837 | <0.001* | 0.461 | 0.005** |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | ||||||

| RFCSA (cm2) | 0.447 | 0.007* | 0.582 | <0.001* | 0.233 | 0.178 |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | 0.315 | 0.065 | 0.602 | <0.001* | 0.151 | 0.388 |

| Malnutrition | Sarcopenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | p value | OR | p value |

| PhA (º) | 0.430 (0.152-1.217) | 0.112 | 0.167 (0.047-0.591) | 0.006** |

| BCM (kg) | 0.817 (0.673-0.993) | 0.042* | 0.797 (0.682-0.932) | 0.005** |

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: rectus femoris muscle | ||||

| RFCSA (cm2) | 0.401 (0.155-1.037) | 0.060 | 0.212 (0.074-0.605) | 0.004** |

| RF-Y-axis (cm) | 0.002 (0.000-0.418) | 0.023* | 0.002 (0.000-0.143) | 0.004** |

| RF-AT (cm) | 0.220 (0.035-1.369) | 0.105 | ||

| Nutritional ultrasound ®: abdominal adipose tissue | ||||

| T-SAT (cm | 0.192 (0.043-0.851) | 0.030* | ||

| S-SAT (cm) | 0.019 (0.001-0.448) | 0.014* | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).