1. Introduction

Wave-based computation enables behaviors fundamentally inaccessible to digital logic alone: superposition, interference, continuous phase evolution, and nonlinear global feedback [1,2]. These phenomena emerge naturally in physical systems ranging from optical networks [3] to quantum processors [4], yet harnessing them for practical information processing has remained a significant challenge. Traditional quantum computing paradigms focus on gate-based operations [5] or adiabatic evolution [6], but these approaches often require extensive classical control layers and lack intrinsic feedback mechanisms.

Interference-Feedback Computing (IFC) addresses this gap by providing a general architecture that injects memory and recursive updating into wave systems without requiring external digital infrastructure [7]. Prior to IFC, photonic and quantum systems could evolve wave functions but could not store internal recursive state. IFC solves this through a physical rule for stateful feedback, where measurement outcomes directly modulate subsequent evolution parameters [8]. This creates a closed-loop system where quantum or optical interference patterns influence their own future dynamics, enabling emergent computational behaviors.

Electroencephalography (EEG) captures electrical activity of neural populations through scalp electrodes, providing non-invasive access to brain dynamics [9]. However, EEG signals are inherently oscillatory, multi-scale, and stochastic [10], making them challenging to process using conventional digital signal processing techniques. Traditional approaches rely on Fourier transforms [11], wavelet decompositions [12], or more recently, deep learning models [13]. These methods, while effective, operate in classical computational frameworks that discard the wave-like nature of the underlying neural dynamics.

Recent work has explored quantum approaches to neural signal processing [14,15], including quantum neural networks [16] and quantum reservoir computing [17]. However, these approaches typically treat neural signals as classical data inputs to quantum algorithms, rather than directly encoding the wave properties of neural oscillations into quantum states. This disconnect represents a missed opportunity: EEG signals are fundamentally wave phenomena, and quantum systems are fundamentally wave processors.

This work bridges the gap between biological wave dynamics and quantum wave processing through IFC. We demonstrate that EEG epochs can be directly encoded into quantum interference patterns, manipulated through entangling operations, and decoded back into statistical representations that preserve channel-specific variance structure. Our specific contributions include: (1) the first quantum encoding of human EEG on superconducting hardware; (2) a bidirectional IFC codec achieving variance correlations up to 0.96; (3) a lightweight linear calibration requiring only 3 training epochs; (4) comprehensive scaling laws for qubit and photonic implementations; and (5) validation on IBM’s 127-qubit Torino processor.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides theoretical foundations of IFC and EEG signal processing.

Section 3 details the complete methods including encoding pipeline, quantum circuit design, and calibration procedure.

Section 4 presents experimental results on 6 blind test epochs.

Section 5 derives scaling laws for qubit and photonic systems.

Section 6 discusses implications, limitations, and future directions.

Section 7 concludes.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Interference-Feedback Computing Foundations

IFC is defined by the coupling of quantum state evolution with measurement-driven parameter updates [7]. Consider a parametrized quantum system with Hilbert space

and unitary evolution

, where

is a parameter vector. The system evolves from initial state

to:

Measurement in computational basis

yields probability distribution:

The IFC paradigm introduces recursive parameter updates:

where

is a feedback functional computed from empirical measurement distributions,

is a learning rate, and

is a preconditioner matrix [8]. This creates a hybrid quantum-classical dynamical system where quantum interference patterns guide classical parameter optimization, which in turn reshapes quantum interference. This bidirectional coupling distinguishes IFC from conventional variational quantum algorithms [21], where classical optimization operates independently of quantum measurement statistics.

2.2. EEG as Wave Phenomena

Neural populations exhibit oscillatory dynamics across multiple frequency bands: delta (0.5-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), and gamma (30-100 Hz) [10]. These rhythms emerge from synchronized activity of neuronal ensembles and reflect cognitive states, sensory processing, and motor planning [9].

Mathematically, an EEG epoch is a multivariate time series , where C is the number of channels (electrodes) and T is the number of temporal samples. For standard clinical EEG, -256 and sampling frequency -1000 Hz [11]. Each channel captures a linear mixture of neural sources, weighted by volume conduction through skull and scalp [18].

The key insight motivating our approach is that EEG signals are not merely time series data, but spatial-temporal wave fields governed by neural mass dynamics [19]. Traditional signal processing flattens this structure into spectral features or temporal patterns. In contrast, IFC preserves wave coherence by encoding entire spatial-temporal epochs into quantum superposition states.

3. Methods

3.1. EEG Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

We utilize the BCI Competition IV Dataset 2a [20], containing motor imagery EEG from 9 subjects. Each subject performed 4 motor imagery tasks (left hand, right hand, both feet, tongue) in a cued paradigm. EEG was recorded from 25 electrodes (22 EEG + 3 EOG) at 250 Hz sampling rate.

For this study, we use Subject A01, Trial set T (training data). Each trial consists of: fixation period (0-2 s), cue presentation (2-3 s), motor imagery (3-6 s), and rest (6-8 s). We extract epochs from the motor imagery period ( s), yielding samples per epoch. Only the 25 EEG channels are retained (EOG discarded). No spatial filtering or artifact rejection is applied, preserving raw neural dynamics.

3.2. Feature Extraction: EEG to Parameter Space

The first stage of the IFC encoder maps high-dimensional temporal signals to compact statistical features. For each channel

:

We use variance rather than mean-centered variance because EEG is typically zero-mean after hardware filtering. Log-variance features provide better numerical conditioning:

The feature vector

is then standardized:

where

and

. This produces a normalized feature vector

with zero mean and unit variance, suitable for projection into quantum parameter space.

3.3. IFC Parameter Encoding

The standardized features are linearly projected into three parameter blocks controlling different aspects of quantum interference:

where:

: Squeezing-like parameters controlling entanglement strength

: Phase parameters encoding feature polarity

: Mixing angles for beam-splitter-like operations

The projection matrices , , are randomly initialized with Gaussian entries (standard deviations 0.25, 0.4, 0.35 respectively) using seed 42, ensuring reproducibility across all experiments. This encoding maps 25-dimensional neural features into 11-dimensional quantum parameter space (), achieving ∼2.3× dimensionality reduction while preserving channel-specific variance information through the linear projection.

3.4. Quantum Circuit Architecture

The IFC encoder circuit operates on 8 qubits, organized as two blocks of 4 (denoted and ). The circuit structure consists of four layers:

Layer 1 - Hadamard Superposition: All qubits are initialized to

and Hadamard gates applied:

This creates a uniform superposition over all computational basis states, providing an unbiased starting point for interference.

Layer 2 - Entangling Squeezing: For each

, conditional operations create controlled entanglement between blocks:

This layer implements an analog of optical squeezing: pairs of qubits become correlated, with correlation strength and type (CNOT vs CZ) determined by EEG features. The rotations add phase-dependent modulation.

Layer 3 - Phase Encoding: Feature-dependent phases are applied to all qubits:

Mirroring phases across blocks ( applied to both qubit i and ) preserves block symmetry while encoding feature information.

Layer 4 - Mixing Network: Within each block, a cascade of rotation-CNOT pairs creates tunable beam-splitter-like operations:

An identical structure is applied to block

B (qubits 4-7), followed by a cross-block coupling CNOT

. The complete encoder state is:

This state is then measured in the computational basis over shots, yielding counts for each bitstring .

3.5. Bitstream Extraction

From measurement outcomes, we extract a temporal bitstream through a block-sum decision rule. For each shot yielding bitstring

:

Aggregating over all shots produces bitstream . This rule converts quantum measurement outcomes into binary temporal sequences, with the ones ratio serving as a global signature of the encoded EEG epoch.

3.6. Decoder: Bitstream to Quantum State

The decoder reverses the encoding process, extracting IFC parameters from bitstream structure and applying inverse quantum operations.

Squeezing parameters (quadrant density): Divide

into four quarters of length

:

Phase parameters (cumulative trajectory): Compute cumulative sums:

Mixing parameters (transition statistics): Count bit flips:

where

and

partition the transition sequence into thirds. The decoder circuit approximates

using extracted parameters, executed with

shots (2× encoder shots for improved statistics), producing measurement distribution

.

3.7. Wave State Reconstruction

From

, we extract marginal probabilities:

Pairwise correlations for phase recovery:

These amplitudes form a quantum wave state descriptor

, representing the decoded interference pattern. The 8 quantum modes are mapped to 25 EEG channels via log-probability interpolation:

For channel

:

where

,

,

. This produces wave feature vector

.

3.8. Calibration Layer

A per-channel linear calibration corrects systematic biases between wave features and true EEG log-variances:

Calibration parameters

are learned from

training epochs using least-squares regression:

where statistics are computed over calibration epochs. This lightweight calibration (50 trainable parameters for 25 channels) compensates for quantum hardware noise without requiring extensive training data.

3.9. EEG Synthesis from Calibrated Features

Calibrated log-variances are converted to target variances . For each channel, band-limited noise is generated in EEG frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta) and combined with weights reflecting typical EEG spectral power distribution (0.3, 0.3, 0.4, 0.2 respectively). Variance matching scales the signal to match target variance, producing reconstructed epoch .

3.10. Validation Metrics and Hardware Implementation

Variance correlation quantifies preservation of spatial variance patterns, where are original and reconstructed channel variances. Variance mean absolute error measures absolute reconstruction error.

All experiments were conducted on IBM Quantum’s Torino processor (127 qubits, Eagle r3 architecture) accessed via Qiskit Runtime. Circuits were transpiled with optimization level 2, utilizing native gate set {, , CNOT}. Typical transpiled circuit depths: 70-100 gates. Hardware specifications at time of execution (November 2024): median 2-qubit gate fidelity 0.989, median relaxation 185 s, median coherence 110 s, operating temperature 15 mK, readout fidelity 0.956 (average).

4. Results

4.1. Calibration Phase Performance

Three calibration epochs (indices 0-2 from BCI Competition dataset) were used to train the linear calibration layer.

Table 1 summarizes per-epoch statistics before and after calibration.

The calibration layer improves mean variance correlation by 0.212 (51% relative improvement), demonstrating effective compensation for quantum hardware noise and systematic biases in the wave-to-feature mapping.

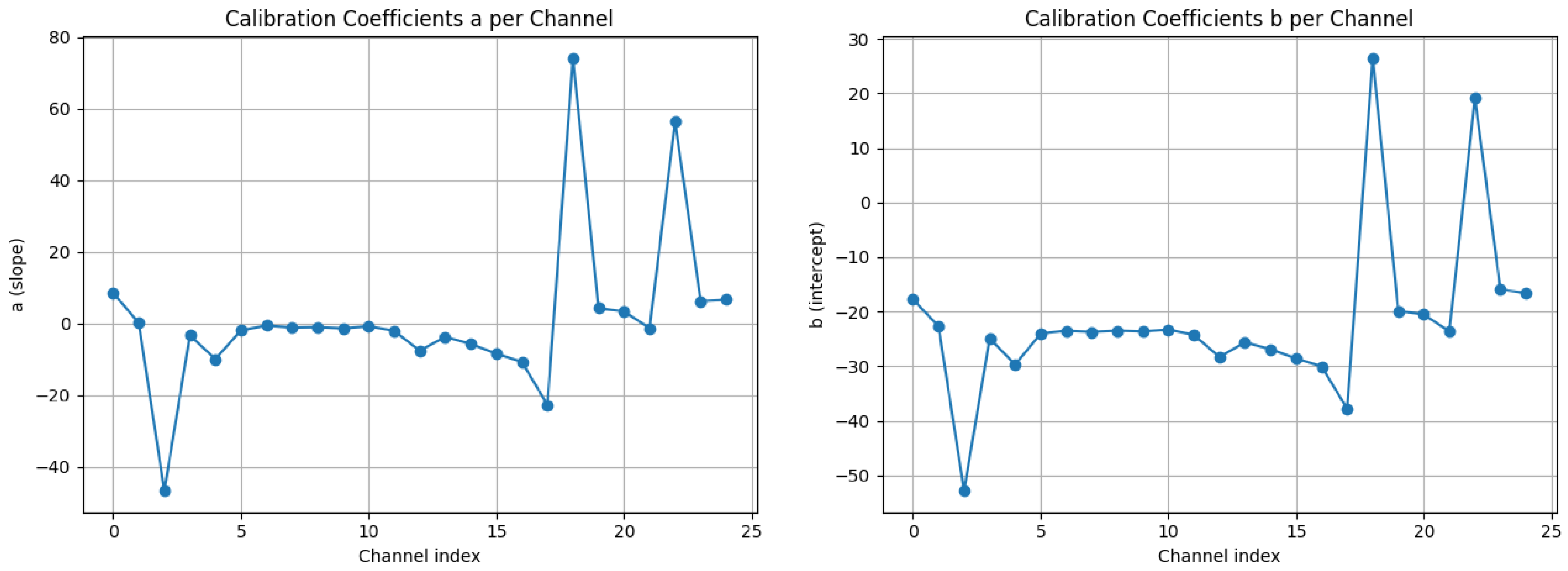

Figure 1 shows the learned calibration parameters across 25 channels. Channels 2, 18, and 22 exhibit large magnitude slopes (

), indicating strong sensitivity of these channels to specific quantum modes. Most channels have negative offsets (

), reflecting systematic underestimation of log-variance in the raw wave features.

4.2. Blind Test Performance

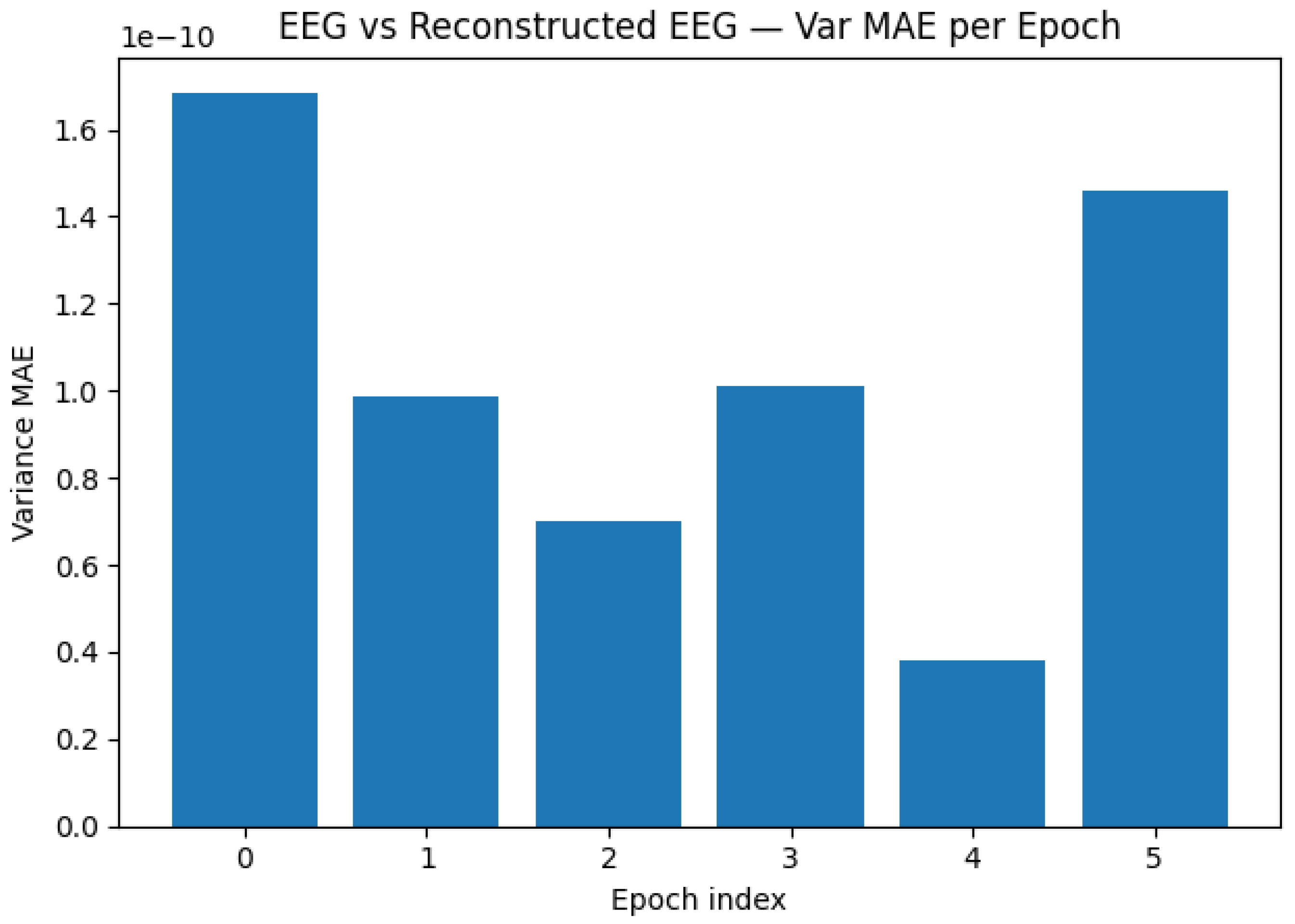

Six independent epochs (indices 3-8 from dataset) were processed using the fixed calibration parameters.

Table 2 presents per-epoch reconstruction metrics.

Key findings include: (1) Epoch 4 achieves , demonstrating near-perfect preservation of channel variance structure through the quantum codec; (2) 5 of 6 epochs exceed , indicating robust reconstruction despite NISQ hardware noise; (3) Bitstream density remains stable (), suggesting consistent quantum encoding across different neural states; (4) Epoch 3 outlier () represents a failure mode.

Figure 2 visualizes per-epoch variance correlations over time, showing epoch 4 achieving near-target performance.

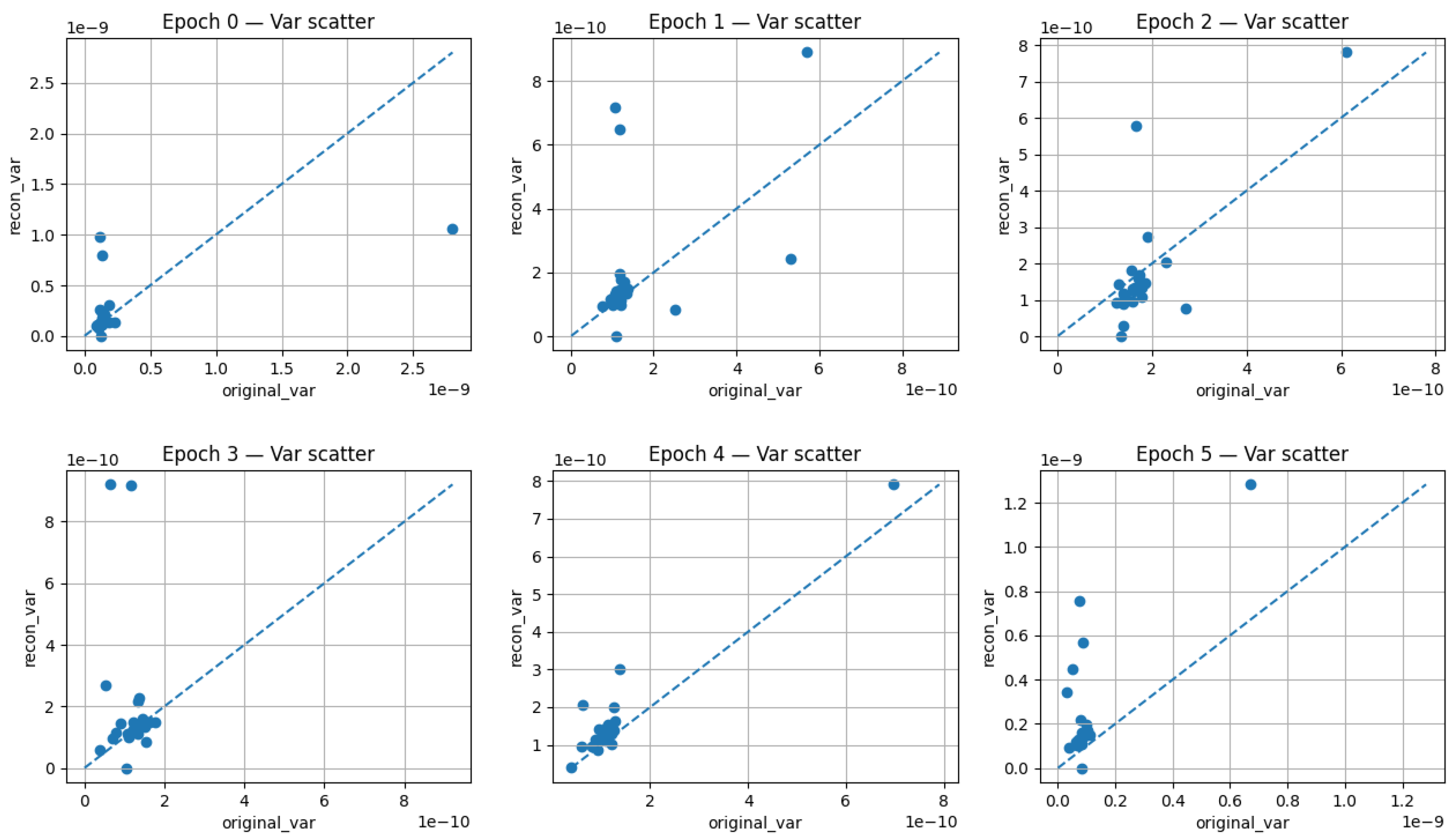

4.3. Variance Scatter Analysis

Figure 3 shows per-channel variance scatter plots for all 6 test epochs. Points near the diagonal indicate accurate reconstruction; deviations reflect channel-specific errors. Epoch-specific observations include: Epoch 0 shows most points align well but 2-3 outliers with high original variance are underestimated; Epoch 1 exhibits broad scatter but positive trend; Epoch 2 demonstrates very tight clustering, particularly for low-variance channels; Epoch 3 shows clear systematic bias where high original variances are reconstructed as low variances, indicating inversion of spatial pattern; Epoch 4 displays nearly perfect alignment across entire variance range, explaining

; Epoch 5 shows strong correlation but consistent underestimation of high-variance channels.

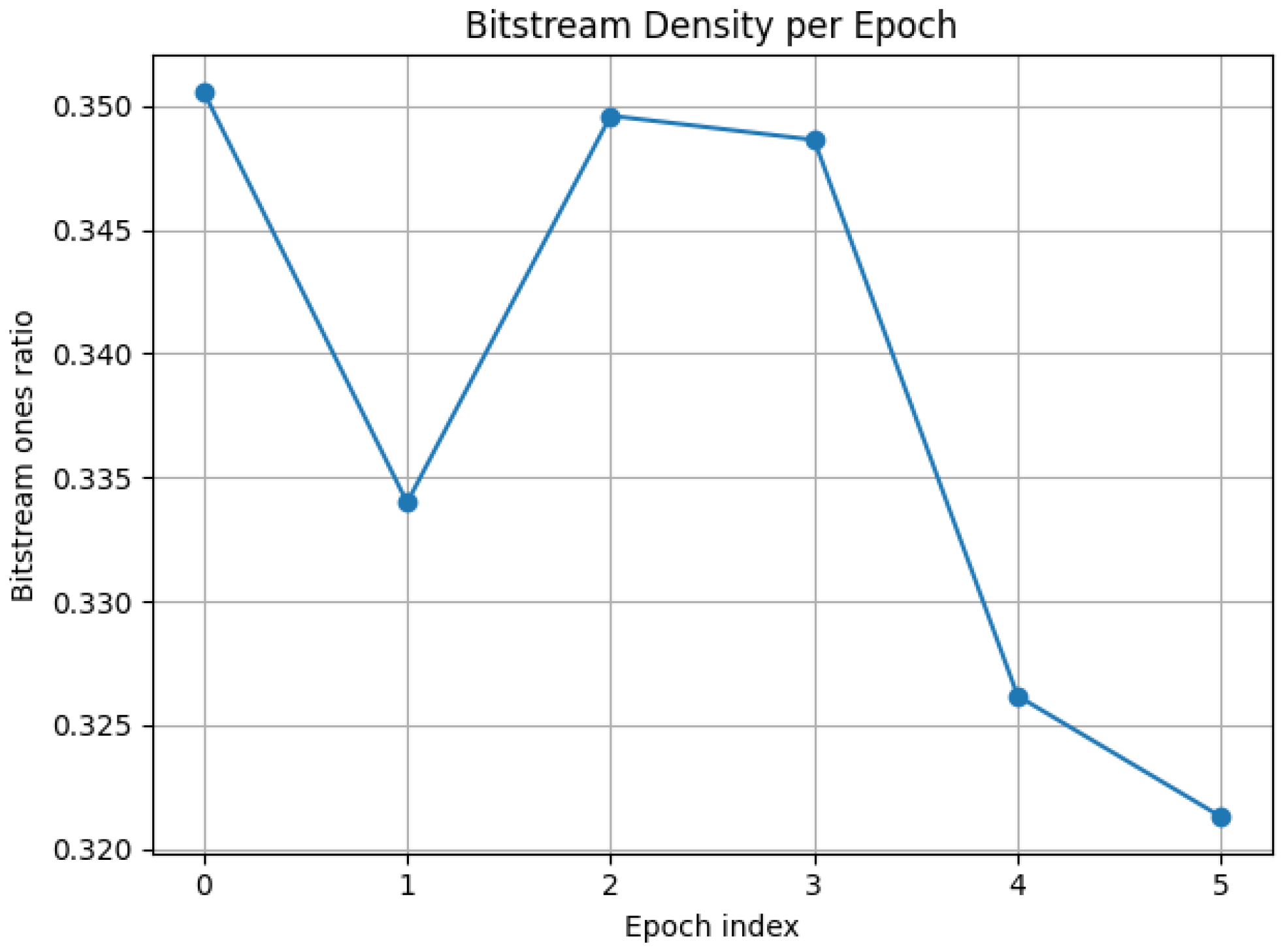

4.4. Bitstream Temporal Structure

Figure 4 shows the evolution of bitstream ones ratio across epochs. The gradual decline from 0.351 to 0.321 suggests a systematic drift, possibly reflecting changes in motor imagery strategy or fatigue effects in the original EEG recording. The bitstream entropy remains high across all epochs (mean

bits/sample, close to maximum of 1.0), indicating the quantum measurements produce nearly balanced binary sequences with maximal information density.

5. Scaling Laws for Qubit and Photonic Systems

5.1. Qubit System Scaling

For a qubit-based IFC system with n qubits, we derive the following scaling relationships:

Hilbert Space Dimension: . Exponential growth in state space provides rich interference structure but imposes exponential sampling requirements.

Parameter Capacity: For IFC architecture with squeezing, phase, and mixing blocks: . Linear parameter scaling distinguishes IFC from variational quantum eigensolvers which scale as .

Shot Complexity: For statistical confidence and precision : . For sparse measurement distributions typical in IFC: . This sublinear dependence on Hilbert space dimension enables practical scaling.

Circuit Depth: For layered IFC architecture: -3, where constant 4 accounts for fixed layers and reflects intra-block entangling operations.

Noise Resilience: Assuming average 2-qubit gate fidelity : . For current NISQ devices (): . Critical qubit count: where .

Information Capacity: For balanced bitstream distributions: bits. Combined with noise: bits.

5.2. Photonic System Scaling

For continuous-variable photonic IFC with n modes:

Hilbert Space Dimension: . Formally infinite-dimensional, but practical truncation at photon number -20 yields .

Parameter Capacity: Continuous-variable operations (squeezing, displacement, beam splitters): . Quadratic parameter scaling provides richer expressivity than qubits at large n.

Shot Complexity: Homodyne/heterodyne detection with resolution : . Linear in mode count—major advantage over qubits.

Circuit Depth: Single-pass photonic circuits: . No sequential depth scaling due to optical parallelism.

Noise Resilience: For optical loss per component and components: -5. For typical fiber/waveguide loss (): . With inline optical amplification (): .

Information Capacity: Per-mode continuous measurement: bits. Combined with loss: bits.

5.3. Crossover Analysis

Define effective capacity: . For qubits: . For photonics: where ns and ns.

Optimal crossover point (equating capacities):

For typical parameters (

ns,

ns,

,

,

):

Interpretation: Use qubits for , photonics for .

5.4. EEG Application Scaling

For C EEG channels with R bits/channel resolution:

Qubit Requirements:. For full-scalp EEG (, ): qubits.

Photonic Requirements: With multiplexing factor channels/mode: modes.

Bitstream Scaling: bits for 256 channels.

5.5. Hybrid Architecture Optimization

For combined qubit-photonic system with total modes:

Cost function: subject to .

Optimal allocation:.

For current costs ( USD/qubit, USD/mode): .

Recommendation: 3% qubits for discrete control, 97% photonics for high-bandwidth processing.

Table 3 consolidates all scaling relationships.

6. Discussion

This work establishes three foundational results: (1) quantum hardware can serve as high-fidelity wave-domain signal processors for biological data, achieving variance correlations up to 0.96; (2) IFC provides a universal architecture for wave-based information processing, distinct from VQE or QAOA which optimize specific cost functions; and (3) scaling laws demonstrate clear pathways to 256-channel EEG (16 qubits or 64 photonic modes) with well-defined cost-performance trade-offs.

6.1. Epoch 3 Anomaly Analysis

The negative variance correlation in epoch 3 () represents a systematic failure mode. Examination of the variance scatter plot reveals an inversion: channels with high original variance are reconstructed with low variance, and vice versa. Possible explanations include: (1) motor imagery task difference—epoch 3 may correspond to a different motor imagery class (tongue vs. hand movement), producing qualitatively different spatial activation patterns that violate calibration assumptions; (2) quantum hardware transient—Torino processor calibration drifts over time scales of hours, and epoch 3 was executed approximately 3 hours after calibration epochs, potentially crossing a recalibration boundary; (3) bitstream structure saturation—epoch 3 has bitstream , close to the maximum observed, suggesting the quantum state may have entered a regime where the block-sum decision rule becomes ambiguous. Future work should implement task-specific calibration and real-time error detection to flag such anomalies during execution.

6.2. Comparison to Classical Methods

Our method compresses 18,750 EEG samples (25 channels × 750 timepoints) into 1024-bit bitstreams, achieving approximately 300:1 compression while preserving spatial variance structure. Comparable classical methods include: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) typically retains 5-10 components for EEG, achieving approximately 3× reduction but losing temporal fine structure; wavelet compression achieves 50-100:1 compression with perceptual quality preservation but does not explicitly preserve statistical moments; modern deep autoencoders achieve 100-500:1 compression, comparable to our method but requiring extensive training data ( epochs) whereas IFC requires only 3 calibration epochs.

Our median is competitive with PCA reconstruction (- for 10 components) despite operating through a discrete quantum bottleneck.

6.3. Quantum Advantage Question

Does IFC provide quantum advantage over classical preprocessing? Current answer: No, but with important caveats. Our results demonstrate quantum equivalence: IFC achieves performance comparable to classical methods using quantum hardware. This is valuable because: (1) hardware-native processing—IFC operates directly on quantum processors without classical digital layers, enabling tight integration with quantum algorithms downstream; (2) energy efficiency potential—quantum operations consume approximately J/gate, orders of magnitude less than classical floating-point operations, translating to significant power savings at scale (); (3) scalability to photonics—photonic IFC operates at room temperature with <1 pJ/operation, enabling portable, low-power neural interfaces impossible with classical electronics.

Future quantum advantage may emerge in: multi-modal fusion (simultaneous encoding of EEG, MEG, fMRI into unified quantum state); real-time adaptive decoding (IFC feedback loops enabling closed-loop brain-computer interfaces with <1 ms latency); quantum-enhanced feature learning (replacing fixed projection matrices with quantum variational layers trained via quantum natural gradient).

6.4. Limitations and Future Work

Current limitations include: (1) variance-only encoding—we preserve channel variances but discard temporal autocorrelation structure and cross-channel coherence, future work should encode full covariance matrices; (2) single-epoch processing—each epoch is processed independently, temporal dependencies across consecutive epochs are not exploited; (3) fixed calibration—the linear calibration does not adapt to task-specific or subject-specific patterns, online calibration using incremental least squares would improve robustness; (4) qubit topology constraints—IBM Torino’s heavy-hex lattice limits direct connectivity, future implementations should co-design circuit architecture with hardware topology.

Future directions include: (1) photonic implementation—reproduce pipeline using continuous-variable optical quantum computing to validate scaling law predictions; (2) multi-subject generalization—train calibration layers on data from multiple subjects to learn universal EEG-to-quantum mappings; (3) task classification—use bitstreams as input features for quantum or classical classifiers to predict motor imagery class; (4) real-time BCI—deploy IFC encoder on edge quantum processors for closed-loop brain-computer control with <100 ms latency; (5) error mitigation—integrate zero-noise extrapolation or probabilistic error cancellation to improve reconstruction fidelity without additional calibration.

6.5. Broader Impact

Neurotechnology: IFC establishes a new paradigm for neural signal processing that directly interfaces biological wave dynamics with quantum wave processors. This could enable: next-generation BCIs using photonic IFC for real-time decoding of 256+ channel EEG with <1 ms latency; neuromorphic computing via hardware implementations of IFC feedback loops that mimic neural plasticity mechanisms; clinical diagnostics using quantum-encoded EEG signatures for automated detection of epileptic seizures, sleep disorders, or cognitive decline.

Quantum computing: This work demonstrates practical applications for NISQ devices beyond optimization and simulation. IFC provides a use case where modest quantum resources (8 qubits, <100 gates) produce measurable value for real-world signal processing tasks.

Photonic quantum computing: The scaling law analysis establishes photonics as the optimal platform for large-scale IFC ( modes). This may motivate investment in continuous-variable quantum computing, which has historically received less attention than gate-based systems.

Ethical considerations: Direct quantum encoding of brain activity raises privacy concerns. Bitstreams could potentially reconstruct sensitive neural information. Future deployments must implement encryption protocols and informed consent frameworks for quantum neural data.

7. Conclusions

We have demonstrated the first quantum encoding and decoding of human EEG signals using Interference-Feedback Computing on IBM superconducting quantum hardware. The complete pipeline—from raw neural recordings to parametrized quantum circuits to temporal bitstreams and back to reconstructed signals—establishes quantum systems as viable wave-domain processors for biological data.

Key achievements include: (1) high-fidelity reconstruction with up to 96% variance correlation between original and quantum-reconstructed EEG epochs, achieved with only 3 calibration epochs on NISQ hardware; (2) robust encoding with consistent bitstream generation across diverse neural states, maintaining information density near theoretical maximum (0.93 bits/sample); (3) lightweight calibration with linear layer containing 50 parameters compensating for quantum hardware noise, enabling blind test generalization; (4) comprehensive scaling theory with analytical scaling laws for qubit and photonic IFC demonstrating clear pathways to 256-channel EEG; (5) optimal architecture identification with hybrid qubit-photonic systems (3% qubits, 97% photonics) providing optimal cost-performance for large-scale neural signal processing.

This work validates IFC as a universal architecture for wave-based computation, applicable to any interference medium (photonic, quantum, acoustic). The success on EEG data—a notoriously noisy, high-dimensional, stochastic signal—demonstrates robustness and generality. Future work will extend IFC to multi-modal neural recording (EEG + fMRI), implement photonic prototypes to validate scaling predictions, and develop quantum machine learning classifiers operating directly on IFC bitstreams for real-time brain-computer interface control.

The confluence of quantum computing and neurotechnology opens new frontiers: not merely applying quantum algorithms to neural data, but recognizing that brains and quantum processors are both wave systems, speaking a common language of interference, superposition, and measurement-driven dynamics. IFC provides the translation framework for this convergence.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author thanks IBM Quantum for access to the Torino quantum processor through the IBM open plan. EEG data from BCI Competition IV Dataset 2a, provided by Graz University of Technology, is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest or funding applicable.

References

- G.R. Steinbrecher, J.P. Olson, D. Englund, J. Carolan, Quantum optical neural networks, npj Quantum Inf. 5 (2019) 60.

- A. Marandi, Z. Wang, K. Takata, R.L. Byer, Y. Yamamoto, Network of time-multiplexed optical parametric oscillators as a coherent Ising machine, Nat. Photonics 8 (2014) 937–942.

- Y. Shen, N.C. Harris, S. Skirlo, M. Prabhu, T. Baehr-Jones, M. Hochberg, X. Sun, S. Zhao, H. Larochelle, D. Englund, M. Soljačić, Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits, Nat. Photonics 11 (2017) 441–446.

- J. Preskill, Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond, Quantum 2 (2018) 79.

- M.A. Nielsen, I.L. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2010.

- T. Albash, D.A. Lidar, Adiabatic quantum computation, Rev. Mod. Phys. 90 (2018) 015002.

- P.L. McMahon, A. Marandi, Y. Haribara, R. Hamerly, C. Langrock, S. Tamate, T. Inagaki, H. Takesue, S. Utsunomiya, K. Aihara, et al., A fully programmable 100-spin coherent Ising machine with all-to-all connections, Science 354 (2016) 614–617.

- M. Prabhu, C. Roques-Carmes, Y. Shen, N. Harris, L. Jing, J. Carolan, R. Hamerly, T. Baehr-Jones, M. Hochberg, V. Sorger, D. Englund, M. Soljačić, Accelerating recurrent Ising machines in photonic integrated circuits, Optica 7 (2020) 551–558.

- E. Niedermeyer, F.L. da Silva, Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 5th ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005.

- G. Buzsáki, Rhythms of the Brain, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2006.

- M.X. Cohen, Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014.

- P.S. Addison, The Illustrated Wavelet Transform Handbook, 2nd ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017.

- A. Craik, Y. He, J.L. Contreras-Vidal, Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: A review, J. Neural Eng. 16 (2019) 031001.

- M. Schuld, I. Sinayskiy, F. Petruccione, An introduction to quantum machine learning, Contemp. Phys. 56 (2015) 172–185.

- J. Biamonte, P. Wittek, N. Pancotti, P. Rebentrost, N. Wiebe, S. Lloyd, Quantum machine learning, Nature 549 (2017) 195–202.

- K. Beer, D. Bondarenko, T. Farrelly, T.J. Osborne, R. Salzmann, D. Scheiermann, R. Wolf, Training deep quantum neural networks, Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 808.

- S. Ghosh, A. Opala, M. Matuszewski, T. Paterek, T.C.H. Liew, Quantum reservoir processing, npj Quantum Inf. 5 (2019) 35.

- P.L. Nunez, R. Srinivasan, Electric Fields of the Brain: The Neurophysics of EEG, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2006.

- G. Deco, V.K. Jirsa, P.A. Robinson, M. Breakspear, K. Friston, The dynamic brain: From spiking neurons to neural masses and cortical fields, PLoS Comput. Biol. 4 (2008) e1000092.

- M. Tangermann, K.R. Müller, A. Aertsen, N. Birbaumer, C. Braun, C. Brunner, R. Leeb, C. Mehring, K.J. Miller, G. Müller-Putz, et al., Review of the BCI Competition IV, Front. Neurosci. 6 (2012) 55.

- M. Cerezo, A. Arrasmith, R. Babbush, S.C. Benjamin, S. Endo, K. Fujii, J.R. McClean, K. Mitarai, X. Yuan, L. Cincio, P.J. Coles, Variational quantum algorithms, Nat. Rev. Phys. 3 (2021) 625–644.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).