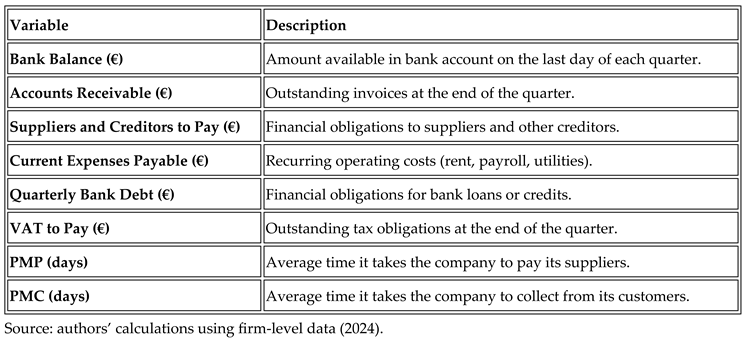

Data Collected and Variables Analyzed

For the analysis, the following financial data were collected from each company, as summarized in

Table 1. These variables provided the basis for constructing the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) and related econometric models used later in the analysis.

These data were organized into four quarters , taking as reference the bank balance on the last day of each period:

First Quarter (Q1 2024) → March 31, 2024

Second Quarter (Q2 2024) → June 30, 2024

Third Quarter (Q3 2024) → September 30, 2024

Fourth Quarter (Q4 2024) → December 31, 2024

Quarterly calculations allowed us to assess how liquidity perceptions are evolving and its impact on financial decision-making.

Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL)

To quantify the liquidity misperception bias, the following formula was used:

PEL = (Bank Balance + Accounts Receivable) / (Suppliers and Creditors Payable + Current Expenses Payable + Quarterly Bank Debt + Taxes)

This index assesses whether companies correctly perceive their liquidity or whether they are falling into a false sense of financial stability. The results are interpreted as follows:

A PEL below 0.8 indicates a high liquidity risk, as companies in this situation present payment flows that greatly exceed their available income, compromising their financial stability. In the range of 0.8 to 1.2, the company is considered to have tight liquidity, managing its treasury with foresight and maintaining a balance between collections and payments. If the PEL is between 1.2 and 1.5, the company experiences a false financial security, overestimating its liquidity by basing itself solely on its bank balance without considering its future obligations. Finally, a PEL above 1.5 reflects an extreme false perception of liquidity, which significantly increases the risk of financial crises due to a lack of adequate cash flow planning.

Justification of the Sample Size

The study analyzed 50 meat companies, selected for their high revenue turnover and operating costs, which amplify the impact of the PEL. Companies with detailed financial records were prioritized, allowing for a longitudinal assessment of liquidity.

The analysis covered four quarters to mitigate seasonal effects and detect financial patterns. Student's t-test confirmed significant differences between companies with high and low PELs (p < 0.05), while the odds ratio showed that a high PEL increases the probability of a liquidity crisis by 4.48 times.

The impact of PMP and PMC on liquidity perception was evident: companies with high PMP and low PMC tended to overestimate their stability, facing cash management problems. Machine learning models identified recurring patterns in this misperception, demonstrating that financial biases can be corrected with predictive tools.

The study provides empirical evidence on the relationship between perceived liquidity and financial management in meat companies. It is recommended that the sample be expanded to 500 companies to validate these findings in other food subsectors. Integrating AI and financial nudges into treasury planning could optimize decision-making, reducing reliance on bank balances as the sole indicator of liquidity.

Data Collection and Analysis

Longitudinal Financial Data

To analyze the evolution of the PEL in meat companies, financial data was collected for 12 months in 2024, organized into four quarters, taking as reference the bank balance at the end of each period: Q1 (March 31), Q2 (June 30), Q3 (September 30) and Q4 (December 31).

To ensure data reliability, three main sources were used: quarterly financial statements (balance sheets, income statements, and cash flows), bank statements to record the final balance for each quarter, and payment and collection records to calculate the PMP and PMC. This information allowed us to assess how liquidity perceptions varied depending on each company's payment and collection structure.

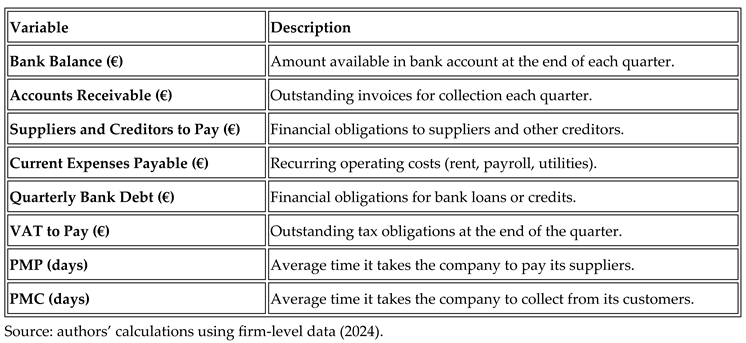

Indicators Analyzed

Eight key financial variables were selected to assess liquidity management and its misperception in the analyzed firms. These are summarized in

Table 2, which presents the variables used to build the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) and related econometric models.

Econometric Analysis and Applied Models

Development of Formulas Prior to Econometric Analysis

Before proceeding with the econometric analysis, it was necessary to develop a series of formulas that would allow for objective quantification of companies' liquidity misperceptions. To this end, the Liquidity Misperception Index (LMP) , the Adjusted Liquidity Balance (ALB) , and the Adjusted Liquidity Ratio (ALR) were designed . These metrics were essential for measuring the discrepancy between entrepreneurs' perceptions of liquidity and their companies' financial reality.

1. Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL)

The Liquidity Misperception (LMP) ratio assesses the difference between a company's perceived liquidity and its actual financial situation. Its calculation is based on a comparison between the estimated bank balance and the actual adjusted liquidity, i.e., the amount of resources available after discounting imminent financial obligations, such as short-term debts, outstanding payments, and taxes. This ratio is key to identifying companies that may be overestimating or underestimating their financial stability, which can influence their investment and spending decisions.

PEL values allow companies to be classified according to their perceived liquidity. When the ratio is between 0.8 and 1.2, the perception of liquidity is tight, indicating that the company has a realistic view of its financial stability and manages its cash flow prudently. However, if the PEL is greater than 1.2, it means the company is overestimating its liquidity, generating a false sense of security that can lead to erroneous decisions, such as making commitments without adequately considering financial risks. Conversely, when the PEL is less than 0.8, the company underestimates its liquidity, reflecting excessive caution that can lead to overly conservative decisions, limiting its investment or expansion capacity.

This indicator is essential for correcting biases in liquidity perception and ensuring that financial decisions are based on objective data and not merely on the availability of bank balances at a given time.

2. Adjusted Liquidity Balance (SLA)

To correct the distortion caused by simply observing the bank balance, the Adjusted Liquidity Balance was developed , which is calculated as:

SLA = Bank Balance − Imminent Financial Commitments

This adjustment allows to identify whether the company really has operational liquidity , eliminating the bias generated by the simple accumulation of funds without considering future obligations.

3. Adjusted Liquidity Ratio (ALR)

Since traditional liquidity ratios can be misleading if they do not consider the structure of financial commitments, an Adjusted Liquidity Ratio was designed , defined as:

RLA=Adjusted Liquid Assets - Adjusted Current Liabilities

This ratio corrects the false financial security derived from the bank balance and provides a more realistic view of the company's financial stability.

To assess the relationship between liquidity misperception and financial stability , advanced econometric models were applied.

1. Visual Analysis of Liquidity Perception

The objective of this analysis was to visualize whether the perceived liquidity (measured through the bank balance) aligns with the financial reality represented by the Adjusted Liquidity Balance and the Adjusted Liquidity Ratio.

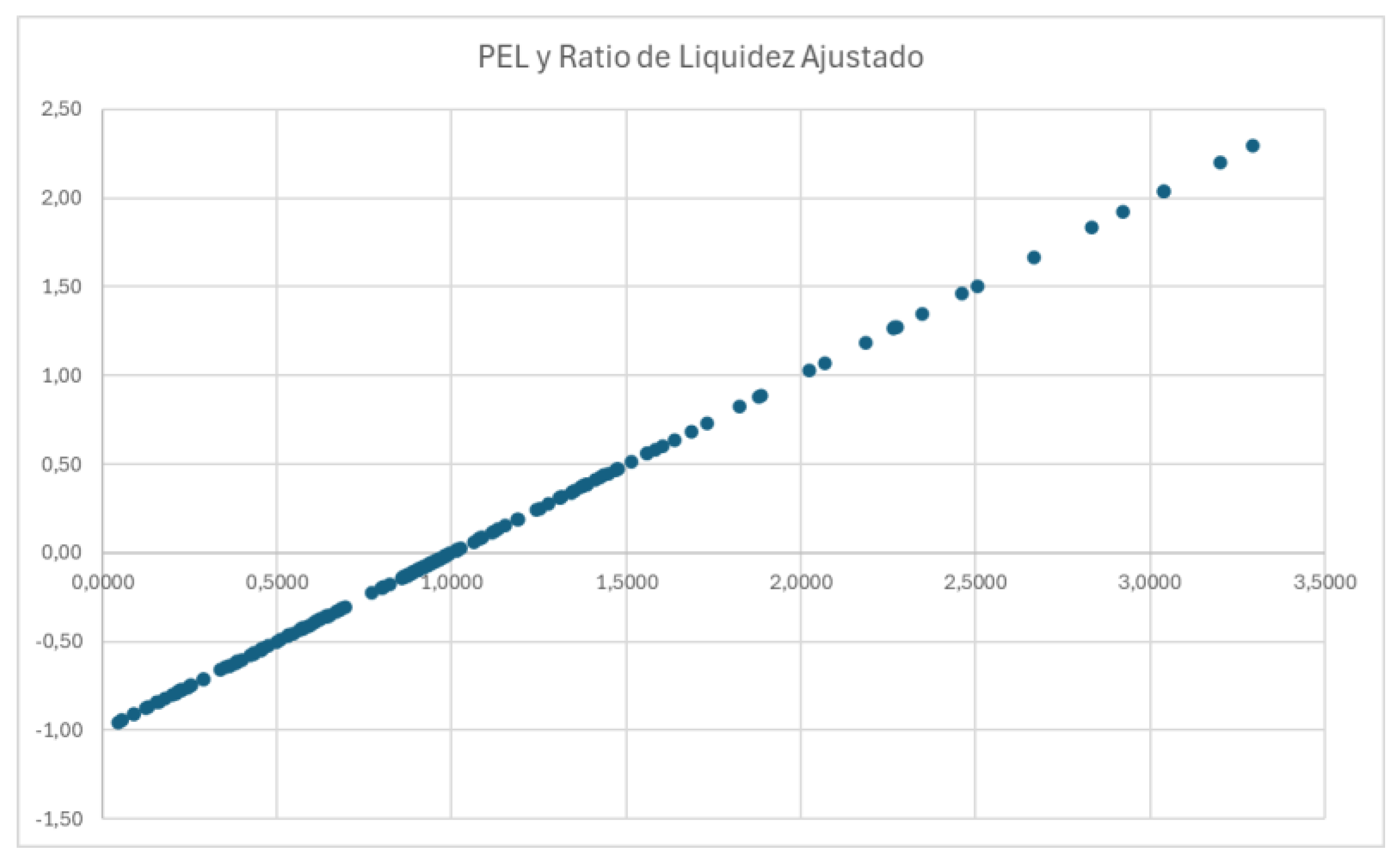

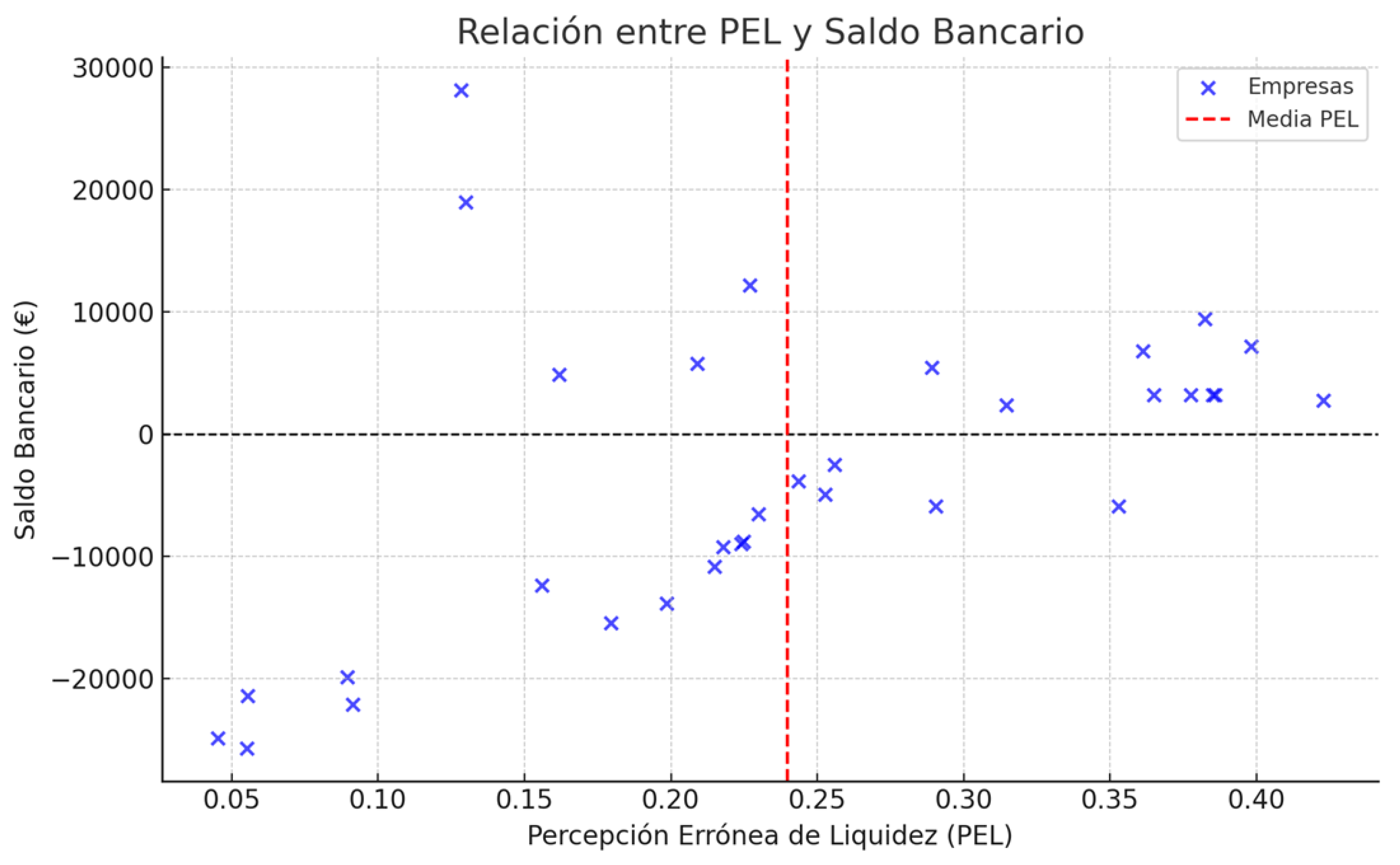

Data analysis revealed a clear positive relationship between the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) and the Adjusted Liquidity Ratio, as shown in

Figure 1. Firms with larger amounts of cash on hand tend to overestimate their liquidity, exhibiting a strong upward trend between perceived and adjusted liquidity. However, a significant portion of these firms displayed negative adjusted liquidity values, suggesting a false sense of financial stability.

Moreover, companies with a high Average Payment Period (APP) and a low Average Collection Period (ACP) exhibited greater liquidity misperceptions, confirming that payment and collection cycles play a critical role in shaping financial perception. During the analysis, several atypical cases were identified in which firms with negative real liquidity still perceived themselves as financially stable—reinforcing the hypothesis that cognitive biases distort the interpretation of liquidity in treasury management.

2. Pearson Correlations between PEL and Liquidity Ratio

Statistical analysis confirmed a significant relationship between liquidity misperceptions (LMP) and actual liquidity , as measured by the Adjusted Liquidity Ratio . The strong positive correlation ( r = 0.77) between the two variables indicates that firms with a high LMP (>1.2) tend to overestimate their adjusted liquidity, reinforcing the hypothesis that the LMP reflects distortions in firms' financial perceptions.

On the other hand, the bank balance showed a low correlation with actual liquidity, confirming that it is not a reliable financial indicator for assessing a company's stability. Furthermore, the negative correlation between the PMP-PMC gap and the PEL ( r = -0.64) suggests that companies that collect before paying have a greater misperception of their liquidity. This relationship highlights the influence of payment and collection cycles on the subjective assessment of financial stability, demonstrating that the structure of the treasury impacts how entrepreneurs interpret their availability of funds.

3. Correlation between PMP - PMC and PEL

Statistical analysis confirmed that the difference between the Average Payment Period (APP) and the Average Collection Period (ACP) directly influences the perceived liquidity misperception (ELP) . The significant negative correlation ( r = -0.64) between the APP-ACP mismatch and the ELP suggests that firms that collect before paying tend to overestimate their liquidity, which increases their perceived financial stability misperception.

Conversely, companies with a lower PMP than their MPC —that is, those that pay before receiving cash—have a more realistic assessment of their liquidity and a lower PEL . This finding confirms that the structure of payments and collections not only affects operating cash flow but also influences how entrepreneurs interpret their financial stability.

4. Linear Regression between PEL and Liquidity Crisis

Linear regression analysis confirmed that the Liquidity Misperception (LMP) ratio is a significant predictor of financial crises in firms. The multiple correlation coefficient obtained ( r = 0.775) indicates a strong relationship between the LMP and the likelihood of facing liquidity problems, while the coefficient of determination (R² = 0.601) suggests that 60.1% of the variability in a firm's financial stability can be explained by the LMP.

Furthermore, companies with a PEL above 1.2 were significantly more likely to experience liquidity crises, reinforcing the role of this ratio as a key tool in assessing financial risk.

5. Logistic Regression: Probability of Liquidity Crisis according to the PEL

Logistic regression analysis confirmed that the Liquidity Misperception Index (LMI) is a significant predictor of financial crises in firms. The results indicated that firms with a LMI greater than 0.9 had an 80% probability of facing a liquidity crisis, while those with a LMI less than 0.7 had a reduced probability of 20% .

The β₁ coefficient of the PEL in the logistic model was 0.40 , suggesting that an increase in the PEL directly increases the probability of a financial crisis. In contrast, the bank balance showed a negative β₂ coefficient (-0.10) , indicating that a higher bank balance contributes to reducing liquidity risk, although it does not eliminate it when financial perceptions are erroneous. These results reinforce the relevance of the PEL as a predictive tool in assessing corporate financial risk.

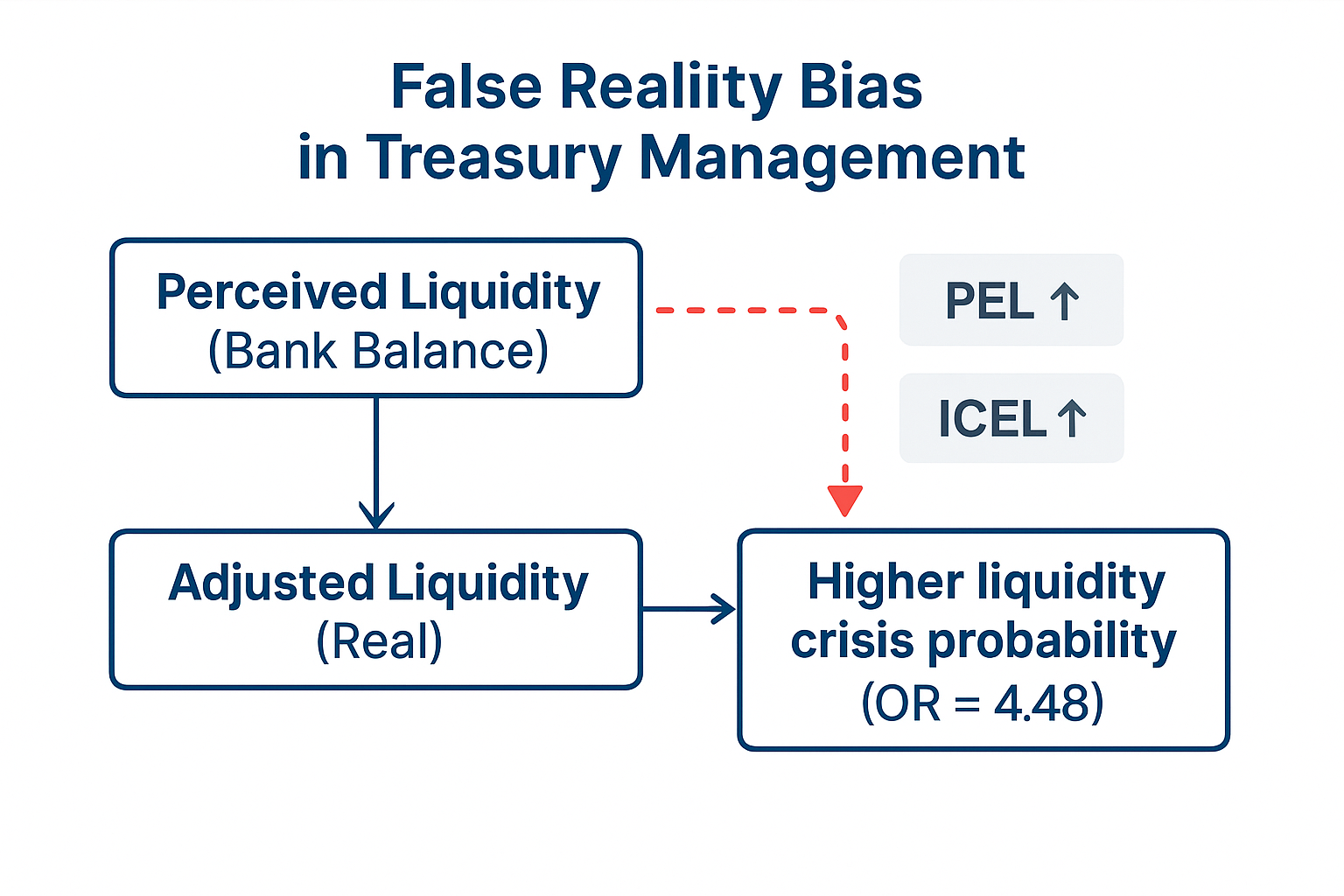

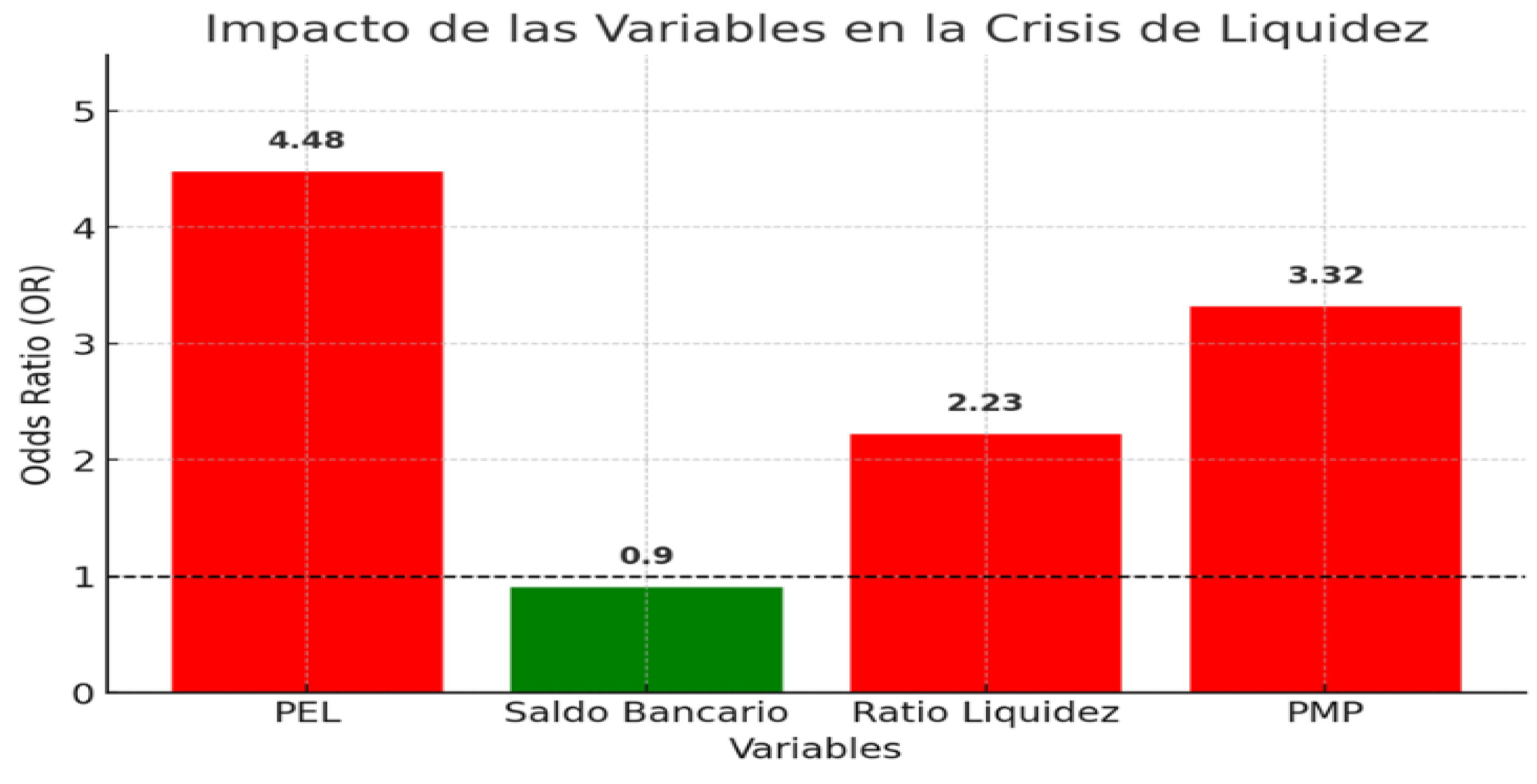

6. Odds Ratio: Quantifying the Risk of a Financial Crisis according to the PEL

To quantify the extent to which liquidity misperception increases the probability of financial distress, an odds ratio (OR) analysis was conducted. The results, displayed in

Figure 2, demonstrate that the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) is a significant predictor of corporate financial vulnerability.

Specifically, the analysis yielded an OR = 1.49, indicating that for every one-unit increase in the PEL, the likelihood of experiencing a liquidity crisis rises by approximately 49%. This confirms that firms displaying stronger liquidity misperceptions are substantially more exposed to financial instability and mismanagement of cash flow.

Conversely, the bank balance presented an OR = 0.90, suggesting that a higher balance slightly reduces the probability of financial distress by 10%. However, this protective effect remains insufficient to counterbalance the distortions caused by a false perception of liquidity when the PEL exceeds 1.2.

In particular, companies with PEL > 1.2 exhibited a markedly higher probability of liquidity crises compared to firms with balanced perceptions, confirming that overestimation of liquidity represents a critical behavioral vulnerability in treasury management. These findings reinforce the behavioral-finance perspective that subjective liquidity perception systematically biases objective risk evaluation, undermining rational financial decision-making.

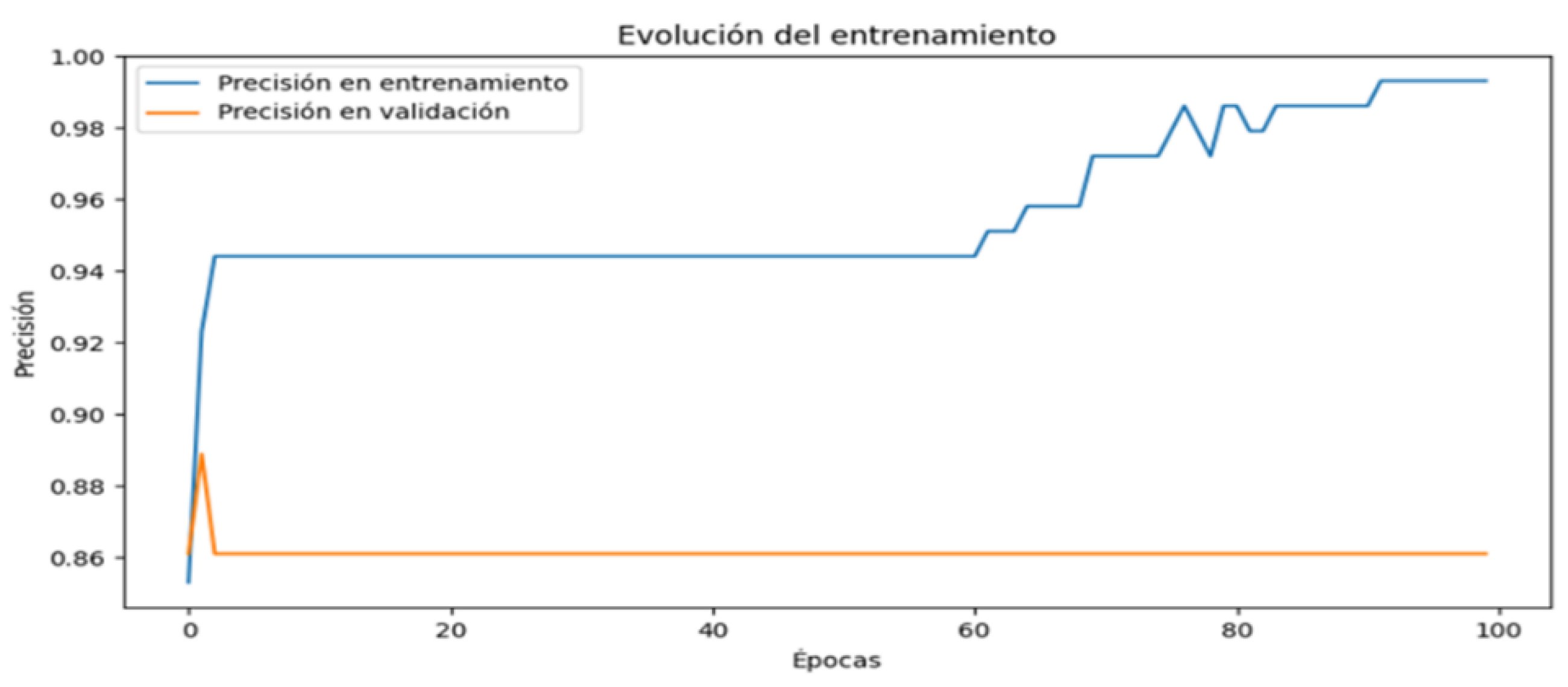

7. Accuracy of the Predictive Model

The predictive model developed using the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) demonstrated a high degree of accuracy in identifying firms at risk of liquidity crises. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the comparison between the training and test datasets showed highly consistent performance curves, indicating that the model generalizes well and does not suffer from overfitting.

Furthermore, the performance evaluation confirmed that the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model was able to correctly distinguish between at-risk and stable firms in the vast majority of cases. The model’s predictive capacity validates its usefulness as a reliable analytical tool for assessing corporate financial stability and for anticipating potential liquidity imbalances arising from behavioral distortions in decision-making.

These findings reinforce the role of AI-driven modeling as a complement to behavioral finance frameworks, providing quantitative mechanisms to identify, forecast, and mitigate risk factors associated with cognitive biases in treasury management.

8. T-Test to Validate Differences between Perception and Reality

A statistical analysis using the Student’s t-test confirmed a highly significant difference between perceived liquidity (as measured by the PEL) and actual financial conditions, represented by both the Bank Balance and the Adjusted Liquidity Balance. As shown in

Figure 4, the mean discrepancy between perceived and real liquidity was large and systematic rather than random, indicating a consistent behavioral pattern in treasury management (p = 1.59 × 10⁻³⁴).

Firms with PEL > 1.2 exhibited a markedly wider gap between perceived and actual liquidity, reinforcing the hypothesis that distorted financial perception can lead to suboptimal or risky decisions. In contrast, companies with PEL < 0.8 displayed closer alignment between their subjective liquidity assessments and objective financial data, suggesting more realistic management behavior.

Moreover, the analysis confirmed that firms showing greater divergence between perception and reality were significantly more likely to face liquidity crises, thereby validating the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) as a robust indicator of financial risk. This finding highlights how cognitive biases in treasury management manifest in quantifiable, statistically significant deviations between perceived and actual liquidity.

9. Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL)

The Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL) was developed to assess how managerial confidence influences liquidity misperceptions and to identify whether entrepreneurs tend to overestimate or underestimate their financial capacity. The index aims to distinguish between three behavioral profiles: (1) overconfidence, which leads to excessive risk-taking; (2) underconfidence, which results in missed investment opportunities; and (3) balanced perception, which reflects effective financial planning and sound decision-making.

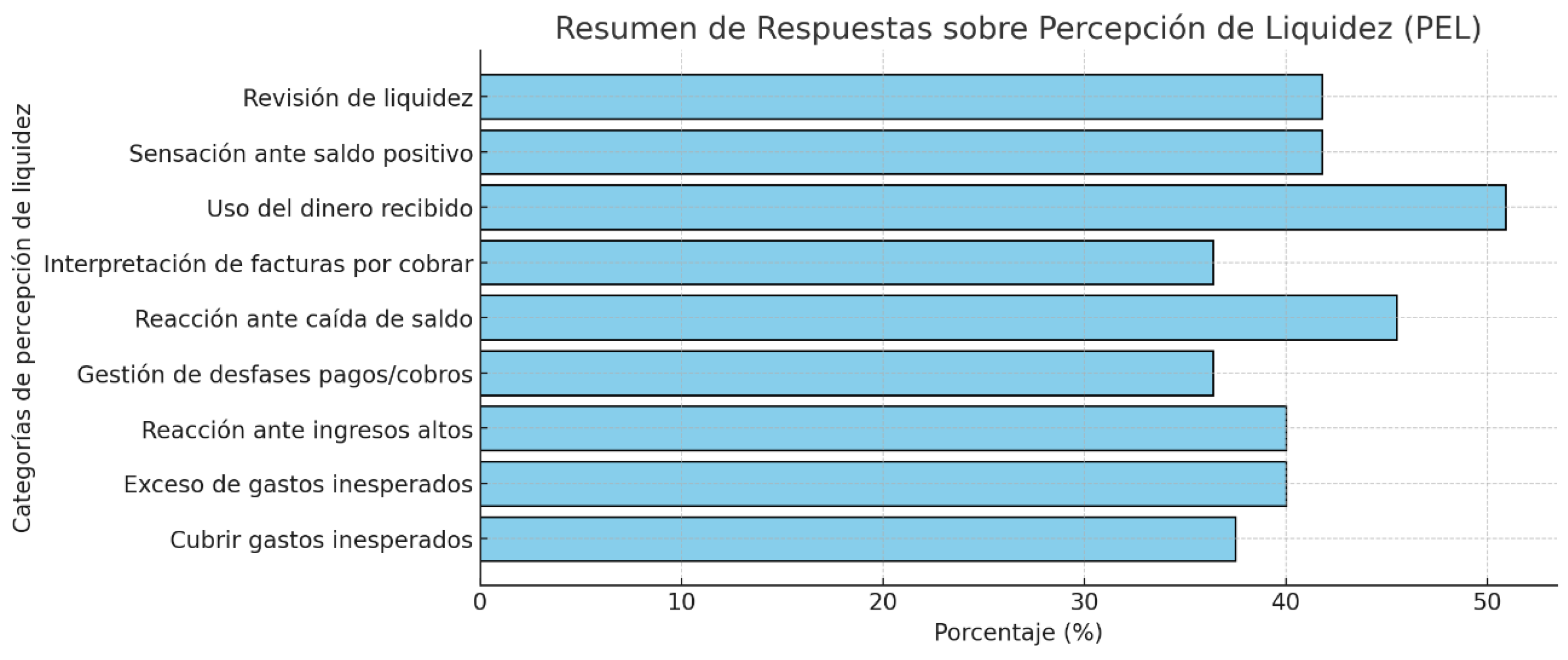

To measure these dimensions, a structured questionnaire was administered and divided into two sections. The first section, focused on the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL), measured the entrepreneur’s confidence in their perceived liquidity. The second section, focused on Financial Planning Efficiency (GFR), evaluated the effectiveness and realism of the firm’s financial planning. Initially, the survey was distributed via social media, but limited participation prompted a shift to direct WhatsApp-based delivery, which significantly improved the response rate and the representativeness of the dataset.

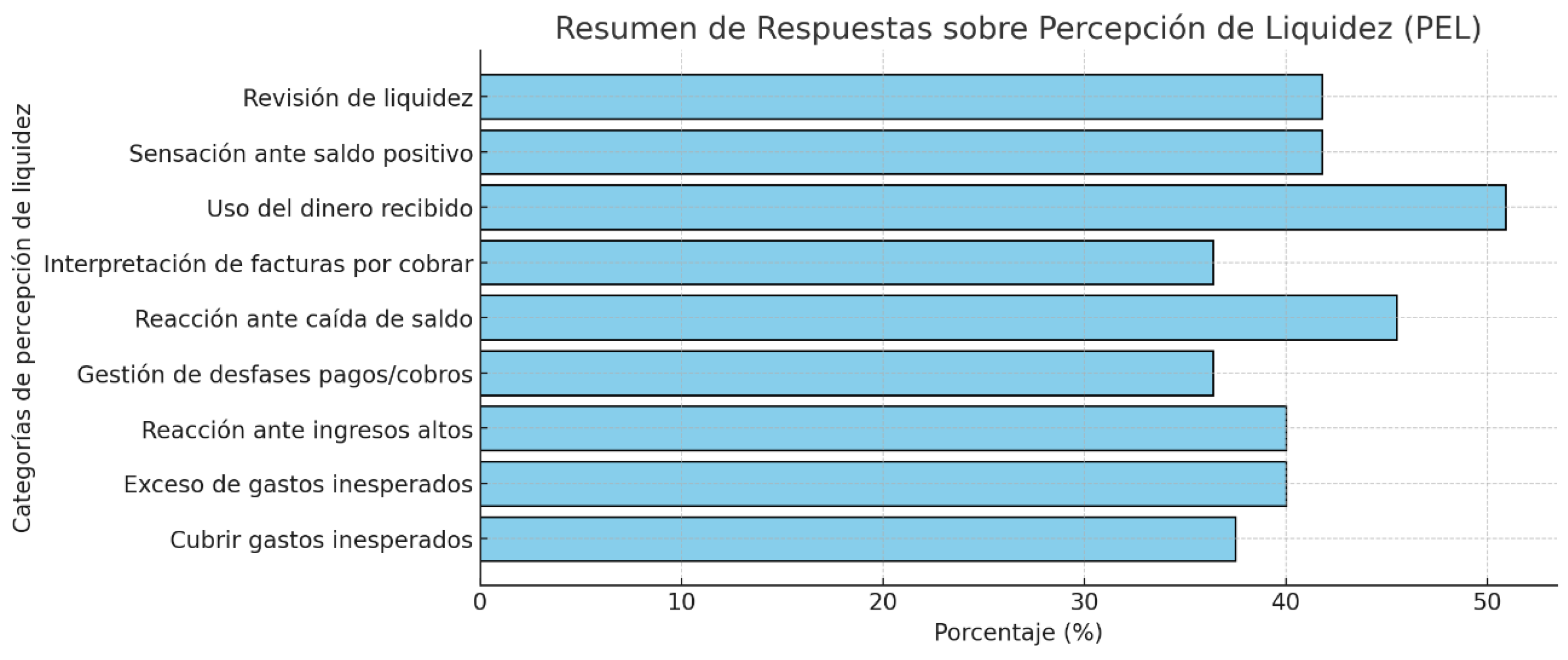

As illustrated in

Figure 5, responses from the first section of the survey (PEL) revealed substantial variability in self-reported confidence levels among participants. The ICEL was subsequently calculated as the ratio between the total PEL score and the GFR score, allowing for a comparative assessment of perceived versus planned liquidity.

Different confidence levels were established based on the ICEL values obtained:

ICEL > 1.3 → Overconfidence, associated with elevated financial risk.

≤ ICEL ≤ 1.3 → Moderate confidence, indicating the need for more accurate financial evaluation.

0.9 ≤ ICEL < 1.1 → Balanced perception, representative of effective liquidity management.

0.75 ≤ ICEL < 0.9 → Moderate caution, aligned with realistic financial perception.

ICEL < 0.75 → Excessive caution, minimizing risk but potentially limiting growth and innovation.

These results demonstrate that confidence in financial decision-making is not always proportional to actual performance. Firms that exhibit either extreme overconfidence or excessive caution face measurable disadvantages in liquidity management compared with those maintaining balanced perceptions.

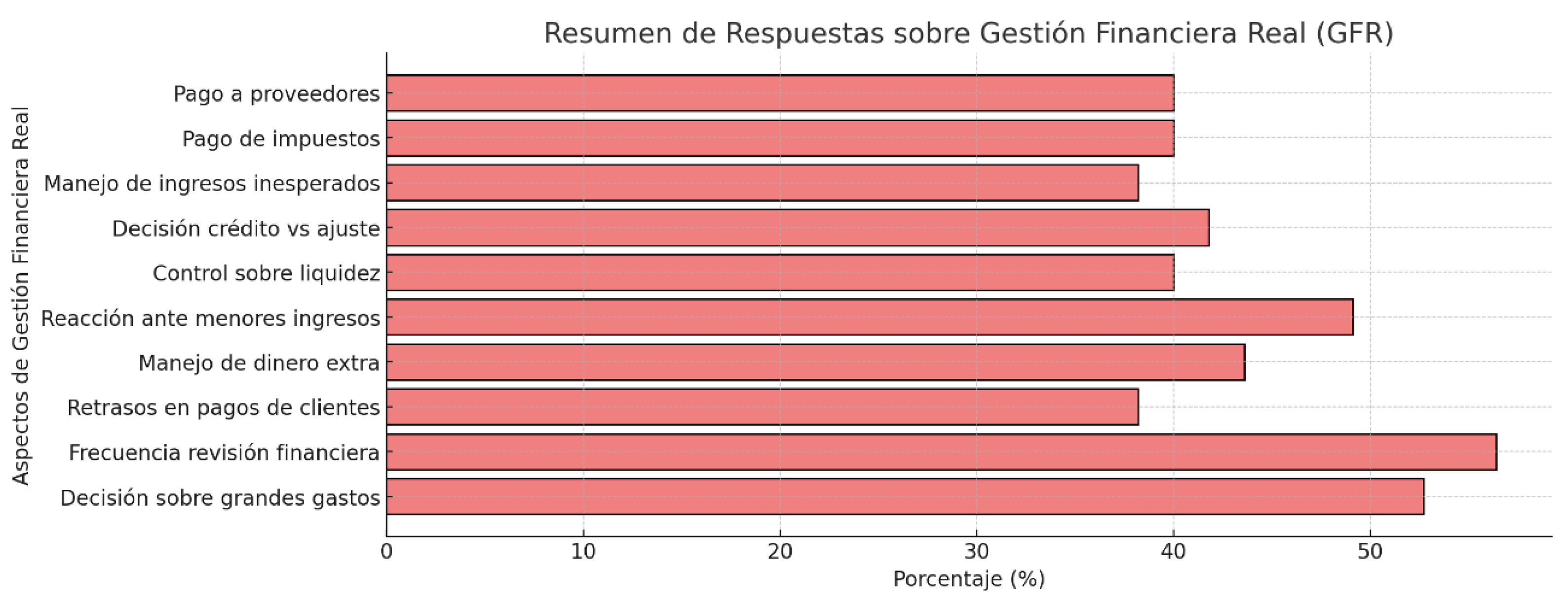

The results obtained from the second section of the questionnaire, focused on Financial Planning Efficiency (GFR), revealed substantial differences in how firms structure and execute their treasury planning. As presented in

Figure 6, respondents displayed a wide range of planning sophistication—from systematic, data-driven approaches to highly intuitive or reactive financial management styles.

These results reflect distinct levels of financial management maturity among respondents. While some entrepreneurs demonstrated a precise and consistent alignment between perceived and actual liquidity, others exhibited clear behavioral distortions, such as anchoring to bank balance or maintaining a false sense of financial security. This divergence reinforces the relevance of combining the PEL and GFR dimensions through the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL), allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of confidence-related biases in treasury management.

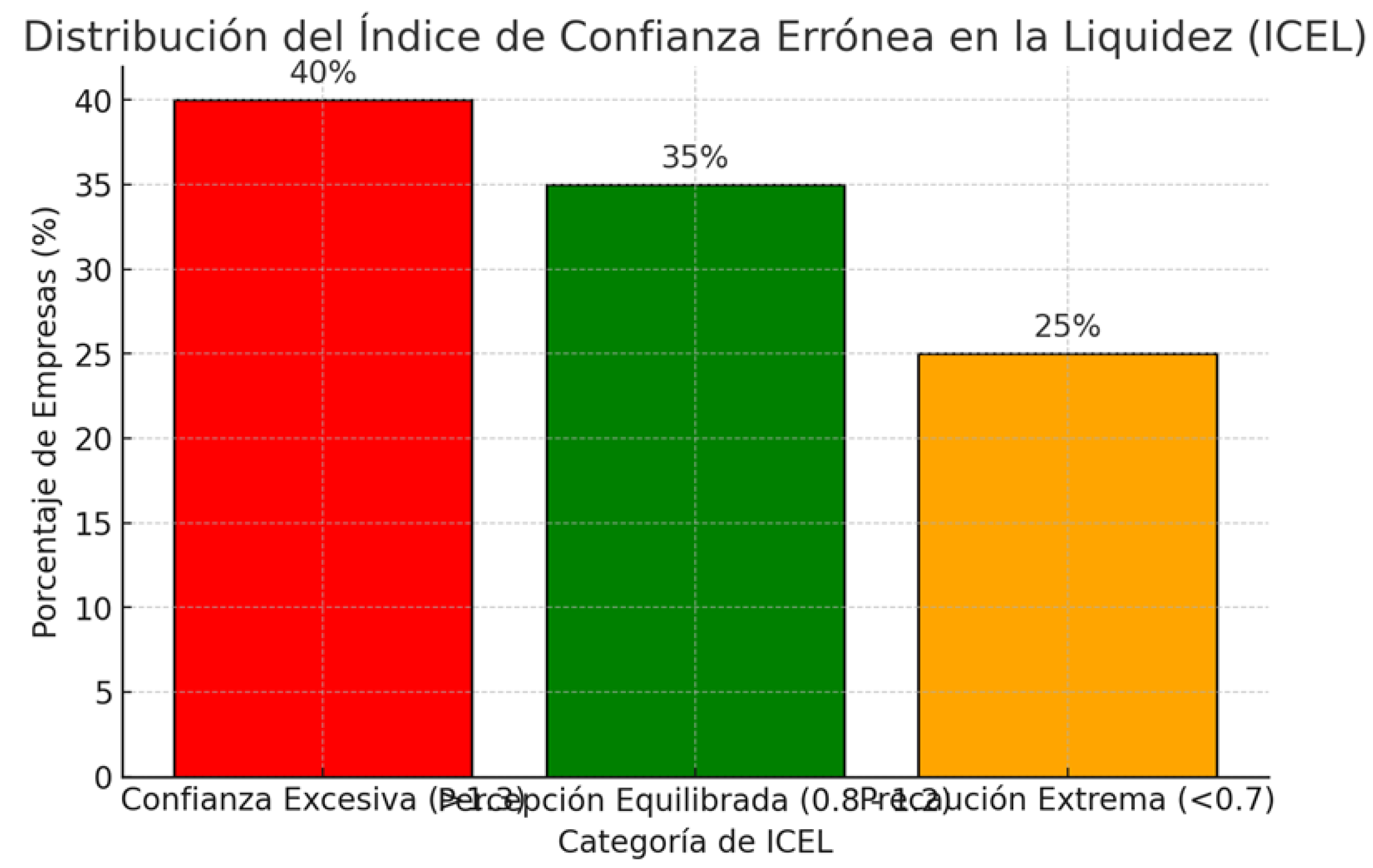

The comparative analysis between ideal financial planning and actual liquidity management revealed notable inconsistencies among the surveyed firms. As illustrated in

Figure 7, the distribution of the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL) shows a marked heterogeneity in managerial behavior: while some companies base their decisions on structured and data-driven financial planning, others continue to rely excessively on their bank balance or adopt improvised short-term solutions, increasing exposure to financial risk and instability. Quantitative analysis showed that 40% of firms exhibited an ICEL above 1.3, indicating overconfidence in their financial standing and a heightened likelihood of making poor decisions rooted in distorted liquidity perceptions. Conversely, 25% of firms demonstrated extreme caution (ICEL < 0.7), reflecting low confidence in financial management and elevated risk aversion—conditions that, while protective in the short term, may hinder long-term business growth. The remaining 35% of companies fell within a balanced perception range (0.8 ≤ ICEL ≤ 1.2), suggesting more accurate liquidity management and a reduced influence of cognitive biases. Importantly, a clear positive correlation between the ICEL and the Perceived Liquidity Error (PEL) was identified: firms with ICEL > 1.3 also tended to overestimate their liquidity (PEL > 1.2). This relationship confirms that misplaced managerial confidence is directly associated with a distorted perception of financial stability, validating the behavioral-finance premise that cognitive biases jointly affect both confidence and perception in treasury decision-making.

Liquidity management isn't just a matter of numbers, but rather how entrepreneurs perceive and trust their financial capacity. The ICEL results reveal that many companies operate with a false sense of security or excessive fear that limits their growth.

Forty percent of entrepreneurs rely too heavily on their liquidity, relying solely on their bank balance and assuming there will always be money available, which leads them to take unnecessary risks. In contrast, 25% avoid opportunities for fear of running out of liquidity, which will hinder their growth. Only 35% maintain a balance between confidence and planning, making decisions based on realistic analysis.

This study demonstrates that liquidity depends not only on the amount of money in your account, but also on how it is interpreted and managed. The key is not blind trust or unreasonable fear, but rather making informed decisions based on data and planning.

10. Relationship between PEL and ICEL

The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the relationship between liquidity misperceptions (PEL) and managerial confidence in financial management (ICEL), exploring the extent to which these behavioral dimensions are interconnected and how they jointly influence strategic decision-making within firms.

It was hypothesized that firms with high PEL values would also exhibit high ICEL levels, indicating excessive reliance on perceived —but not actual— liquidity, thereby exposing themselves to greater financial risk. Conversely, firms with low PEL values were expected to display low ICEL scores, reflecting limited managerial confidence and a tendency toward excessive risk aversion.

The analysis further aimed to determine whether a statistically significant correlation exists between the two indices, which would enable their joint use as predictive indicators of liquidity crises. Identifying this relationship contributes to a deeper understanding of how distorted liquidity perceptions and managerial overconfidence (or underconfidence) interact to shape financial stability and decision-making outcomes.

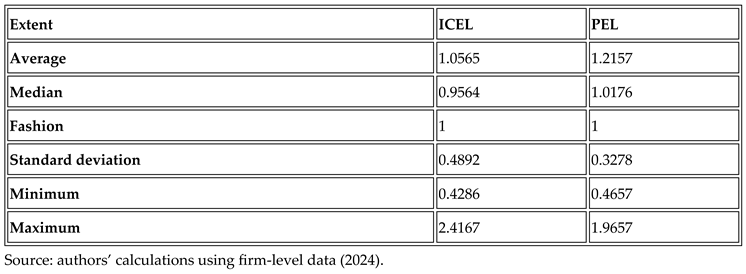

Descriptive Statistics: Characterization of the Indices

To characterize the distribution of both indices, descriptive statistical measures were calculated for the

Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) and the

Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL). As summarized in

Table 3, these measures provide an overview of the central tendencies and variability of the dataset, supporting subsequent correlation and regression analyses.

The interpretation of the results indicates that the Liquidity Misperception Index (LMI) has a mean above 1, suggesting that most companies overestimate their actual liquidity. In contrast, the Liquidity Misconfidence Index (LMI) shows greater variability, with a wider range of values, demonstrating significant differences in entrepreneurs' confidence in their financial management.

The median of both indices is close to 1, indicating that a considerable proportion of companies operate within reasonable values in terms of perception and confidence. However, the presence of significant exceptions suggests the need for further analysis to identify specific patterns in extreme cases and assess their impact on financial stability.

Distribution of PEL and ICEL: Histograms

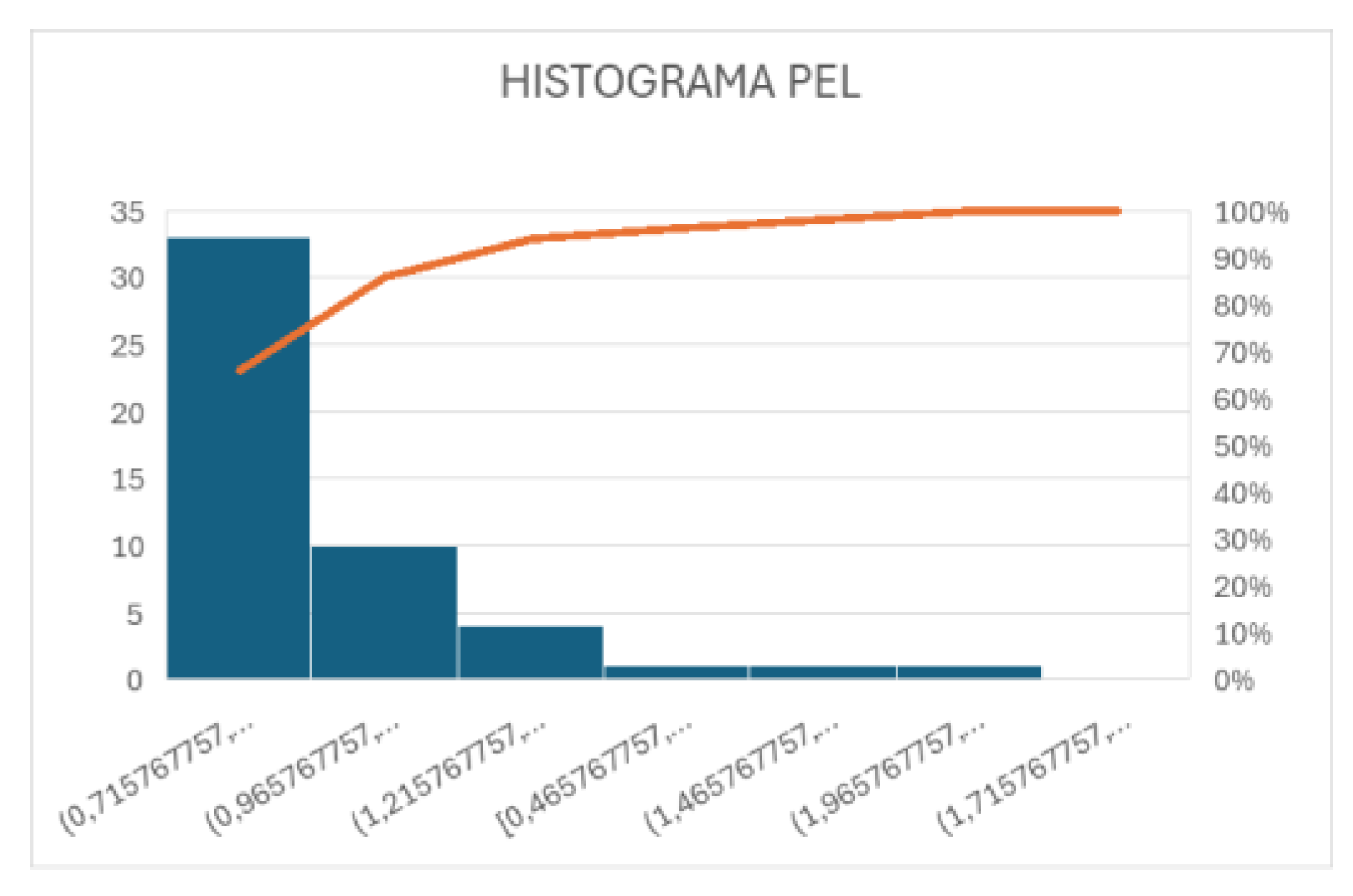

To gain a clearer understanding of the overall behavior of both indices, two histograms were constructed to visualize their respective frequency distributions. The first histogram focuses on the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL), assessing how frequently companies exhibit distorted perceptions of liquidity.

As shown in

Figure 8, the distribution of the PEL is moderately concentrated around values close to 1, indicating that most firms maintain a perception of liquidity that approximates financial reality. However, the right-tailed spread of the histogram reveals the presence of a significant subset of companies whose PEL values exceed 1.2, reflecting a tendency toward overestimation of liquidity and an accompanying illusion of financial stability.

This skewed distribution confirms that while the majority of firms perceive liquidity within a reasonable range, a non-negligible proportion systematically misjudge their financial position. These findings align with the behavioral-finance hypothesis that cognitive anchoring and overconfidence biases can cause persistent deviations between perceived and actual liquidity.

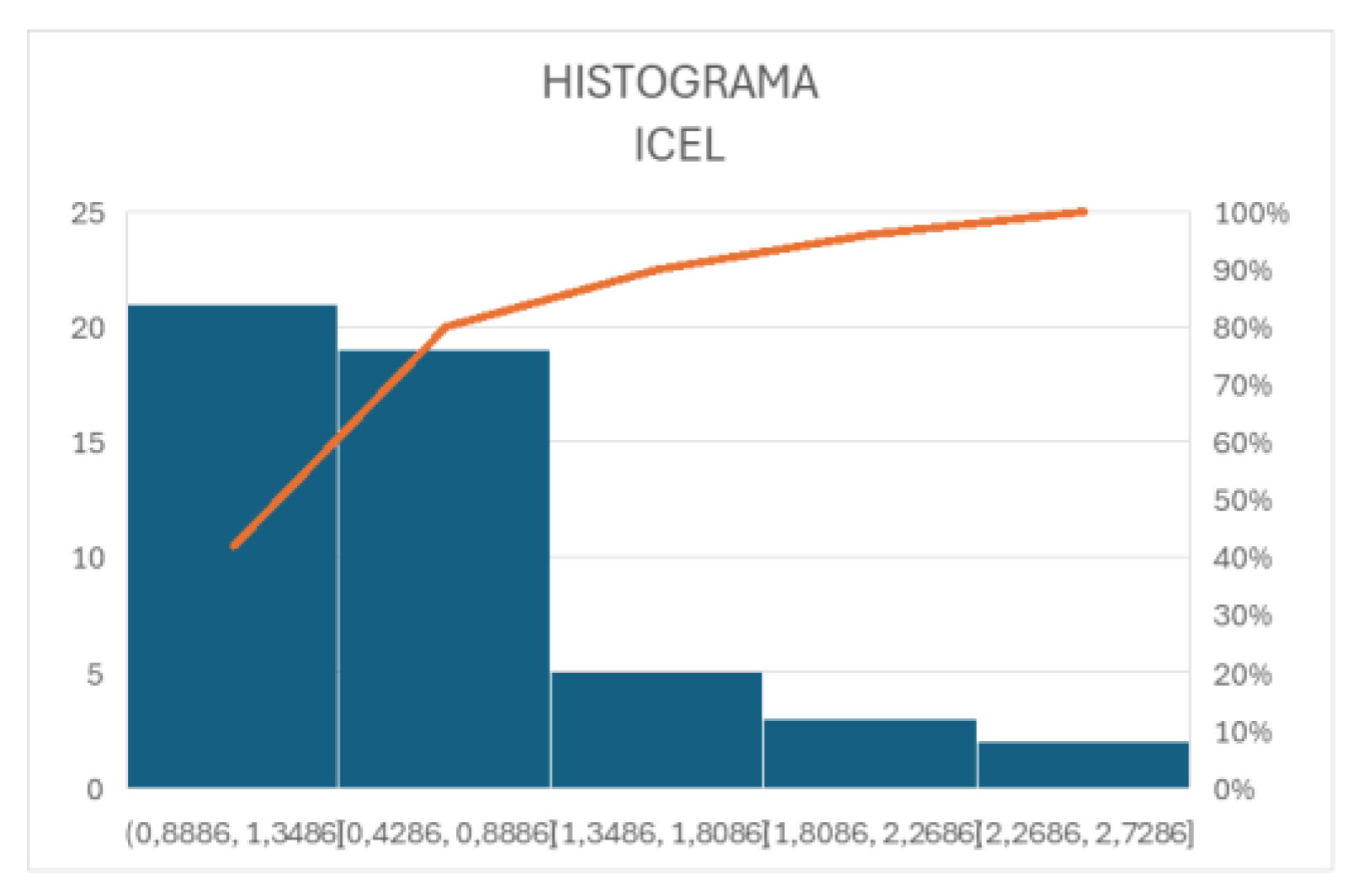

The second histogram focuses on the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL), which measures how frequently companies either rely excessively or insufficiently on their financial management practices. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the ICEL distribution is noticeably wider than that of the PEL, indicating a greater degree of dispersion and behavioral heterogeneity among firms.

While a portion of companies clusters around values near 1—reflecting balanced managerial confidence—there are substantial groups at both extremes. Firms with ICEL values above 1.3 demonstrate overconfidence, often taking unwarranted financial risks based on inflated perceptions of control. Conversely, those with ICEL values below 0.7 exhibit excessive caution, which, although protective in nature, may constrain investment, innovation, and long-term growth.

This bimodal distribution highlights that confidence in financial decision-making does not necessarily follow the same pattern as liquidity perception. The wider variance in ICEL values suggests that managerial confidence is shaped not only by financial indicators but also by psychological traits, prior experience, and contextual uncertainty, consistent with the principles of behavioral economics and decision theory.

Data analysis further revealed that the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) exhibits a more concentrated distribution around values close to 1, with fewer extreme values. In contrast, the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL) shows greater dispersion, with a significant proportion of firms at the extremes (<0.7 and >1.3), confirming that confidence in financial management varies more widely than liquidity perception.

A noteworthy finding is that, although 41% of companies displayed tight liquidity according to the PEL, 29.4% of them were excessively cautious according to the ICEL. This implies that, even when their liquidity perception was accurate, they lacked confidence in their financial management—suggesting that factors such as prior experience, organizational culture, or conservative strategies may strongly influence managerial confidence.

The greater dispersion of the ICEL compared to the PEL confirms that confidence in liquidity management does not follow a predictable statistical pattern and is subject to multiple behavioral variables beyond objective financial perception. These results reinforce the need to incorporate psychological and strategic components into the analysis of corporate financial behavior.

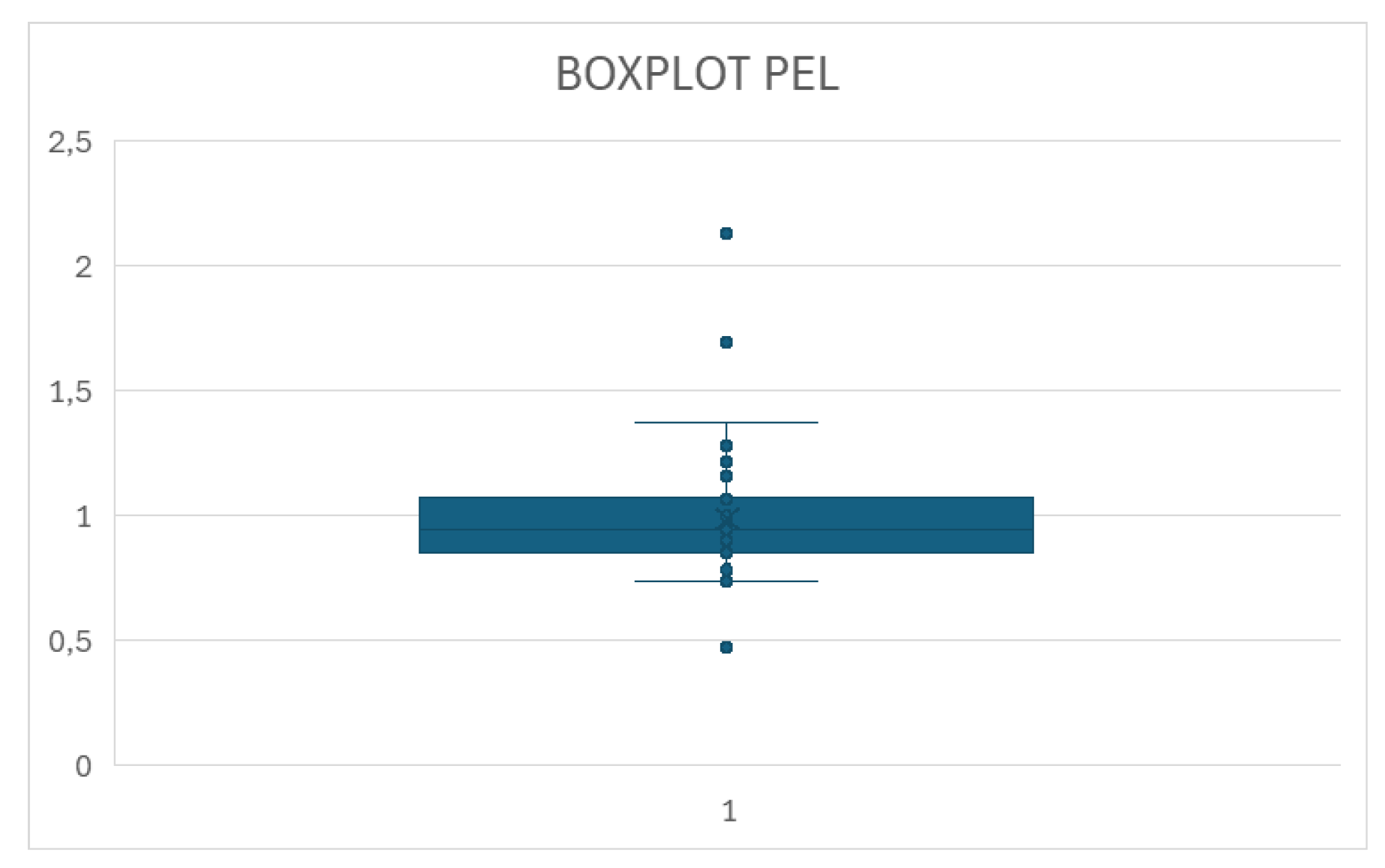

Variability and Outliers: Boxplots

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the boxplot representing the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) provides a clear visualization of the dispersion and outliers associated with firms’ perception of liquidity. The analysis reveals a relatively narrow interquartile range, suggesting that most companies maintain a stable and homogeneous perception of their financial liquidity. Only a few outliers appear above the upper whisker, indicating firms that significantly overestimate their liquidity conditions—likely due to cognitive biases such as overconfidence or optimism bias. The lower dispersion and limited presence of extreme values imply that, in general, firms exhibit a moderate deviation between perceived and actual liquidity levels. This consistency supports the idea that, while perception errors exist, they are less volatile across firms than the distortions observed in managerial confidence measures.

Variability and Outliers: Boxplot of the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL)

As shown in

Figure 11, the boxplot of the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL) reveals a substantially higher degree of dispersion compared to the PEL distribution, indicating pronounced variability in managerial confidence levels across firms. Several extreme values are observed at both ends of the scale, reflecting cases of excessive self-assurance (ICEL > 1.3) and extreme caution (ICEL < 0.7). This wider spread suggests that confidence distortions are more volatile and less predictable than liquidity perception itself, often influenced by emotional, contextual, and neurocognitive factors under stress. Such heterogeneity implies that while some managers overestimate their control and financial stability, others display disproportionate fear of liquidity loss—both tendencies that can lead to suboptimal decision-making. The ICEL variability thus underscores the behavioral-finance principle that confidence, rather than rational analysis, frequently dominates treasury-related decisions.

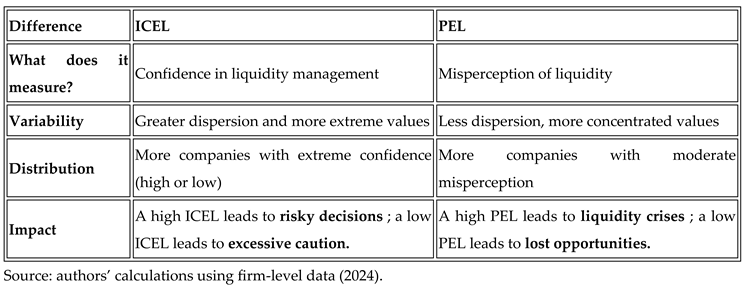

Similarities and Differences between PEL and ICEL

A comparative analysis was conducted to identify the main similarities and differences between the Liquidity Misperception Index (PEL) and the Index of Mistrust in Liquidity (ICEL). Although both indices evaluate corporate liquidity from complementary behavioral-finance perspectives, they capture distinct dimensions of managerial decision-making.

Similarities

Both the PEL and the ICEL analyze firms’ liquidity behavior but from two complementary perspectives. The PEL measures the accuracy of perceived liquidity relative to objective financial data, while the ICEL quantifies the degree of managerial confidence associated with that perception.

Both indices exhibit a median close to 1, suggesting that most companies operate within a balanced range in terms of both liquidity perception and confidence. However, in both datasets, outliers were identified, indicating the presence of firms that systematically overestimate or underestimate their liquidity and managerial capability. These extreme cases highlight the behavioral heterogeneity across firms and underscore the importance of incorporating psychological and strategic variables when analyzing financial stability.

Differences

As summarized in

Table 4, the comparative analysis revealed significant differences between the two indices. While the PEL displays lower dispersion—indicating that firms tend to maintain relatively stable perceptions of liquidity—the ICEL exhibits higher variability, suggesting greater diversity in managerial confidence levels.