Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

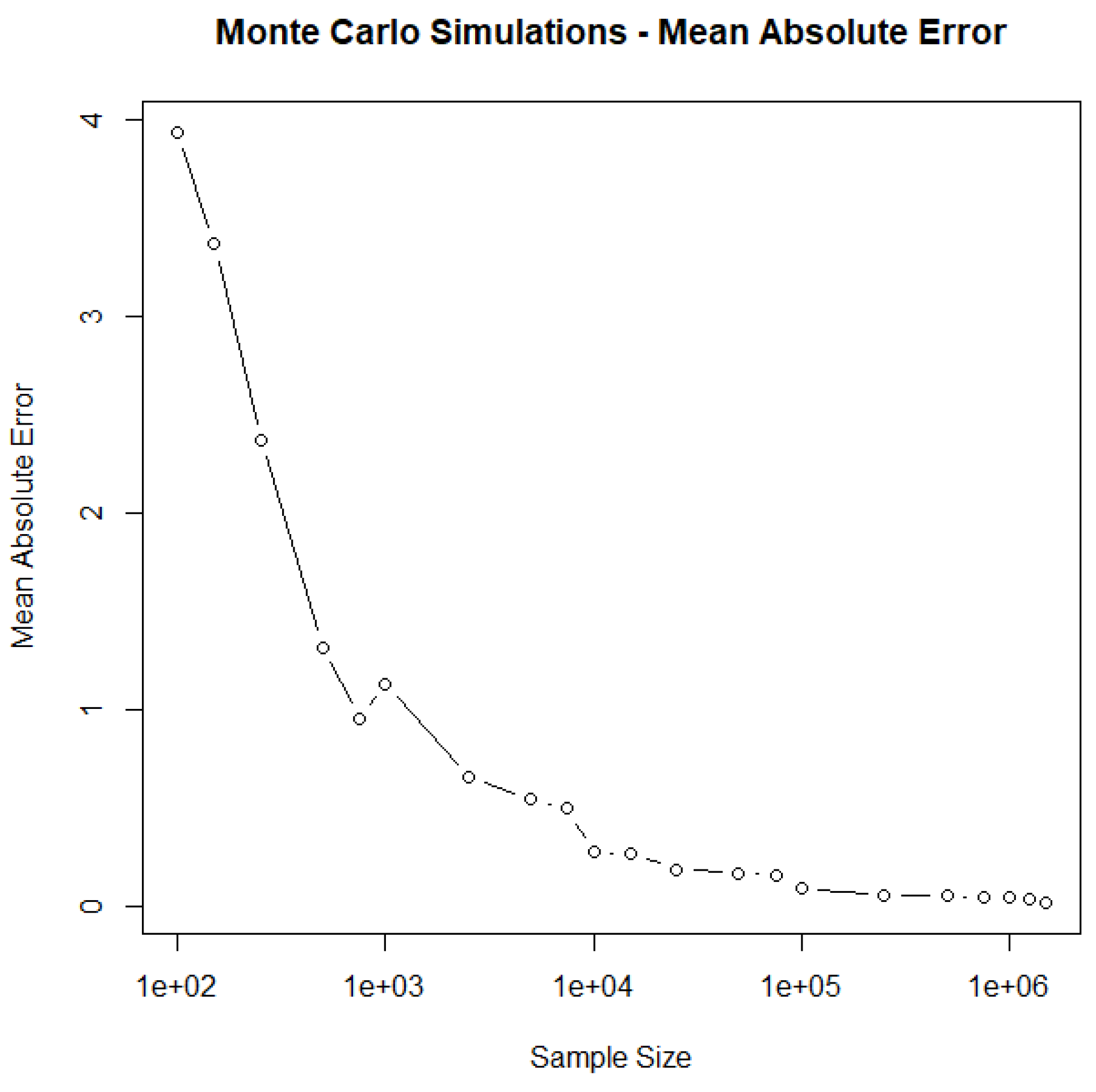

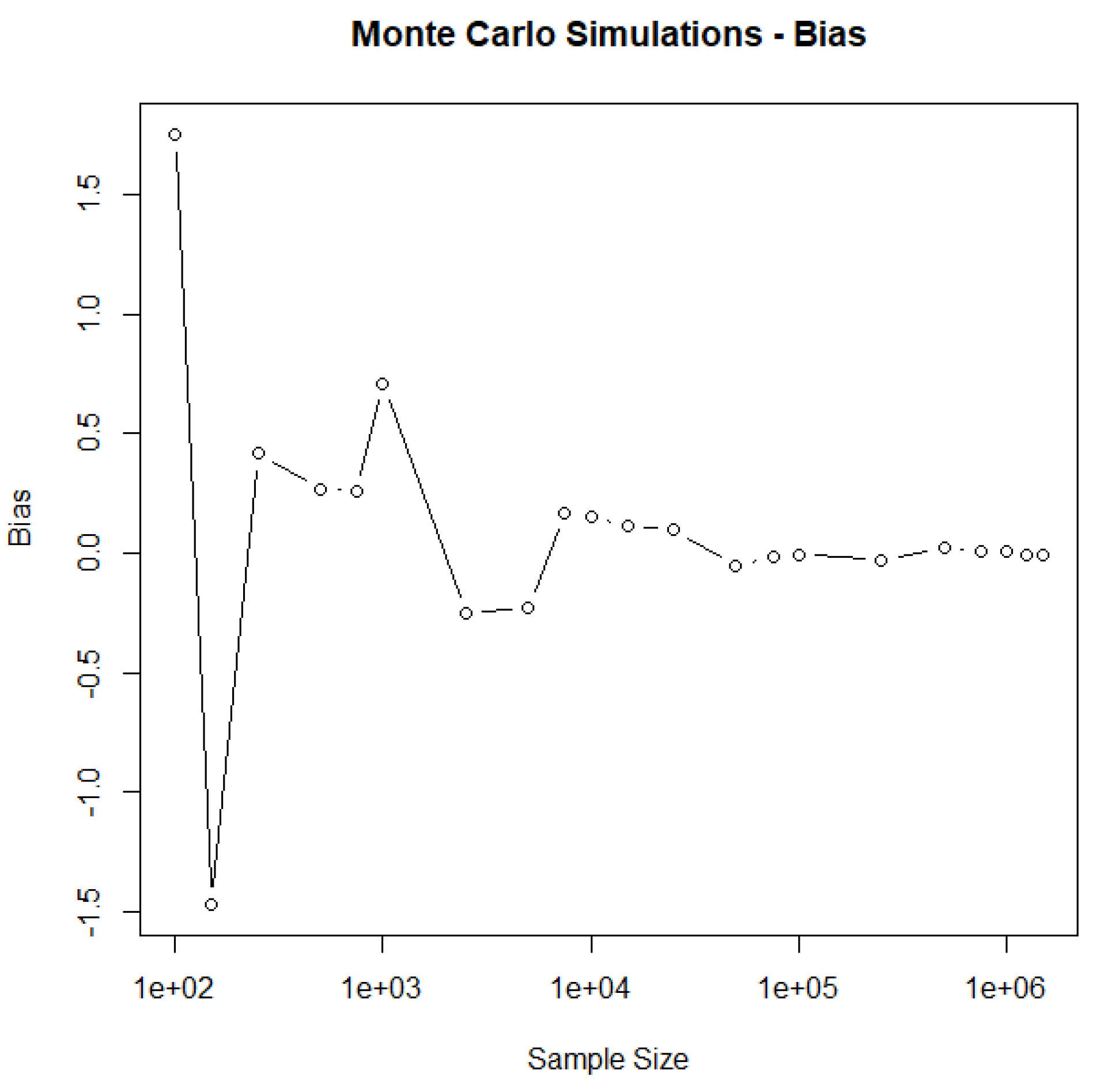

2. Monte Carlo Simulation in Treasury Management

3. Veridical Type Paradoxes

3.1. Bertrand’s box

- A box containing two gold coins

- A box containing two silver coins

- A box containing one gold coin and a silver coin

- P(A) – probability of choosing gold coin in second toss

- P(B) – probability of choosing gold coin in first toss

- [

- basicstyle=\small,

- ]

- #Bertrand's paradox

- set.seed(100)

- samplesize<-1000000

- a<-sample(0:2,samplesize,replace=T)

- # 3 boxes: 0- gold, gold; 1 - silver, silver; 2 - gold, silver

- b<-sample(0:1,samplesize,replace=T) # 2 balls in each box

- data<-data.frame(a,b)

- data2<-subset(data,(a==0) | (a==2 & b==0),select=a)

- round(sum(a==0)/nrow(data2),4) # final probability

3.2. Three prisoners dilemma

- A,B,C are corresponding prisoners

- P(A),P(B),P(C) are probabilities that governor pardoned corresponding prisoners

- a,b,c are events which warden mentions that corresponding prisoners were pardoned

- [

- basicstyle=\small,

- ]

- # Three prisoners problem

- set.seed(100)

- samplesize<-1000000

- governor<-sample(0:2,samplesize,replace=T)

- fm<-function(a,j) {

- if (a[j]==0) {thisone<-sample(1:2,1,replace=T)}

- if (a[j]==1) {thisone<-2}

- if (a[j]==2) {thisone<-1}

- thisone

- }

- warden<- sapply(1:samplesize, function(j) fm(governor,j))

- r<-data.frame(governor,warden)

- # Warden told B, given governor choose A.

- sum(r$warden==1 & r$governor==0)/sum(r$warden==1)

- # Warden told C, given governor choose A.

- sum(r$warden==2 & r$governor==0)/sum(r$warden==2)

- # Warden told B, given governor choose C.

- sum(r$warden==1 & r$governor==2)/sum(r$warden==1)

- # Warden told C, given governor choose B.

- sum(r$warden==2 & r$governor==1)/sum(r$warden==2)

3.3. Monty Hall problem

- Events C1,C2,C3, are indicating the car is behind door 1,2 or 3.

- $P(C_1 )=P(C_2 )=P(C_3 )={1\over 3}$

- Event X1 is indicating player initialy choosing door 1.

- As the position of the car is independent of the player’s first choice $P(C_i |X_1 )={1\over3}$.

- H3 is host opening door 3.

- 1)

- Switching decision

- 2)

- Flip a coin decision

- 3)

- Tic-toc decision

- 4)

- Opposite tic-toc decision

- [

- basicstyle=\small,

- ]

- #Monty Hall problem

- samplesize<-100000 # sample size

- doors<-9 # doors count -1

- door<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- prize<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- changedp<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- nochangep<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- ttp<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- ottp<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- flipp<-vector("numeric",length=doors*(doors-1)/2)

- results <- data.frame(door, prize, changedp, ttp,flipp,

- ottp,nochangep)

- #tic-toc oppposite tic-toc function

- ttott<-function(ttott1,win1,win2,trigger){

- if (ttott1==0) {if (win2==0) {thisone<-0

- } else {thisone<-1 }}

- if (ttott1==1) {if (win1==0) {thisone<-1

- } else {thisone<-0 }}

- if (trigger=="ott") {if (thisone==0) {thisone<-1

- } else {thisone<-0 }}

- thisone}

- for (i in 2:doors) {

- for (j in 1:(i-1)) {

- set.seed(100)

- initial<-replicate(samplesize,list(sample(0:i,1,replace=F)))

- priz<-replicate(samplesize,list(sample(0:i,j,replace=F)))

- # initial guess & prizes behind doors

- flip<-sample(0:1,samplesize, replace=T) # flip a coin

- tt<-sample(0,samplesize,replace=T) # tic toc

- ott<-sample(0,samplesize,replace=T) # opposite tic toc

- choices<-replicate(samplesize,list(c(0:i)))

- # WHICH GOAT WILL BE SHOWN

- goats<-mapply(setdiff,choices,priz)

- goats2<- lapply(1:ncol(goats), function(p) goats[,p])

- # goats are opposite prizes

- notinitial<-mapply(setdiff,choices,initial)

- notinitial2<-lapply(1:ncol(notinitial),

- function(p) notinitial[,p])

- # group of not initial decisions

- goats3<-mapply(intersect,goats2,notinitial2)

- goats4<-lapply(goats3, function(p) c(p,p))

- goat<-lapply(goats4, function(p) sample(p,1))

- # to show just one goat from intersect not initial & goats

- remove(goats,goats2,choices,notinitial,goats3,goats4)

- chmind<-mapply(setdiff,notinitial2,goat)#to change mind

- #to exclude goat which was shown from not initial group

- if (is.null(ncol(chmind))==FALSE) {

- chmind2<- lapply(1:ncol(chmind), function(p) chmind[,p])

- } else {chmind2<-chmind }

- chmind3<-lapply(chmind2, function(p) c(p,p))

- newmind<-lapply(chmind3, function(p) sample(p,1))

- # to choose 1 new decision from all the available

- remove(notinitial2, goat,chmind,chmind2,chmind3)

- win1<-mapply(intersect,newmind,priz)#win1 changed mind

- win2<-mapply(intersect,initial,priz)#win2 not changed mind

- win13<-as.numeric(lapply(win1,function(p) length(p)==0))

- win23<-as.numeric(lapply(win2, function(p) length(p)==0))

- # intersection - 1 no intersection,0 intersection

- for(l in 1:(samplesize-1)) { # TIC-TOC, OPPOSITE TIC TOC

- tt[l+1]<-ttott(tt[l],win13[l],win23[l],'tt')

- ott[l+1]<-ttott(ott[l],win13[l],win23[l],'ott')}

- #PROBABILITIES

- win1p<-sum(win13==0)/samplesize #win1p changed mind

- win2p<-sum(win23==0)/samplesize #win2p not changed mind

- remove(newmind,priz,initial,win1,win2)

- flipfr<-data.frame(win13,win23,flip,tt,ott)

- flip1<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$flip==1 & flipfr$win13==0,])

- flip2<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$flip==0 & flipfr$win23==0,])

- # flip1 - changed mind,flip2 - initial decision

- tt1<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$tt==1 & flipfr$win13==0,])

- tt2<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$tt==0 & flipfr$win23==0,])

- ott1<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$ott==1 & flipfr$win13==0,])

- ott2<-nrow(flipfr[flipfr$ott==0 & flipfr$win23==0,])

- flipp<-(flip1+flip2)/samplesize

- tictocp<-(tt1+tt2)/samplesize

- opptictocp<-(ott1+ott2)/samplesize

- results$door[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-i+1#RESULTS - WRITTING

- results$prize[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-j

- results$changedp[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-round(win1p*100,3)

- results$ttp[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-round(tictocp*100,3)

- results$flipp[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-round(flipp*100,3)

- results$ottp[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-round(opptictocp*100,3)

- results$nochangep[i*(i-1)/2-i+1+j]<-round(win2p*100,3)

- remove(win13,win23,flipfr,flip,tt,ott) } }

- nname<- paste(toString(samplesize),"r.txt",sep="")

- write.table(results,nname,append=FALSE)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carsey T., J. Harden (2014), Monte Carlo Simulation and Resampling Methods for Social Science, SAGE Publications, London.

- Koller D., N. Friedman (2009), Probabilistic Graphical Models Principles and Techniques, The MIT Press, London.

- Page S. (2010), Diversity and Complexity. Princeton University Press, Woodstock 2010.

- Brandimarte P. (2014), Handbook in Monte Carlo Simulation: Applications in Financial Engineering, Risk Management, and Economics, Handbook in Monte Carlo Simulation: Applications in Financial Engineering, Risk Management, and Economics, pp. 1 - 662. [CrossRef]

- Alban A., Darji H.A., Imamura A., Nakayama M.K. (2017), Efficient Monte Carlo methods for estimating failure probabilities, Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 165, pp. 376 - 394. [CrossRef]

- Austin P.C. (2009), Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and monte carlo simulations, Biometrical Journal, 51 (1), pp. 171 - 184. [CrossRef]

- Austin P.C. (2009), Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples, Statistics in Medicine, 28 (25), pp. 3083 - 3107. [CrossRef]

- Arnold U., Yildiz Ö. (2015), Economic risk analysis of decentralized renewable energy infrastructures - A Monte Carlo Simulation approach, Renewable Energy, 77 (1), pp. 227 - 239. [CrossRef]

- Steffen B. (2018), The importance of project finance for renewable energy projects, Energy Economics, 69, pp. 280 - 294. [CrossRef]

- Batan L.Y., Graff G.D., Bradley T.H. (2016), Techno-economic and Monte Carlo probabilistic analysis of microalgae biofuel production system, Bioresource Technology, 219, pp. 45 - 52. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh Banu J., Preethi, Kavitha S., Gunasekaran M., Kumar G. (2020), Microalgae based biorefinery promoting circular bioeconomy-techno economic and life-cycle analysis, Bioresource Technology, 302, art. no. 122822. [CrossRef]

- Vithayasrichareon P., MacGill I.F. (2012), A Monte Carlo based decision-support tool for assessing generation portfolios in future carbon constrained electricity industries, Energy Policy, 41, pp. 374 - 392. [CrossRef]

- Pereira E.J.S., Pinho J.T., Galhardo M.A.B., Macêdo W.N. (2014), Methodology of risk analysis by Monte Carlo Method applied to power generation with renewable energy, Renewable Energy, 69, pp. 347 - 355. [CrossRef]

- Hong L.J., Hu Z., Liu G. (2014), Monte carlo methods for value-at-risk and conditional value-at-risk: A review, ACM Transactions on Modeling and Computer Simulation, 24 (4), art. no. 5. [CrossRef]

- Fantazzini D. (2009), The effects of misspecified marginals and copulas on computing the value at risk: A Monte Carlo study, Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 53 (6), pp. 2168 - 2188. [CrossRef]

| No | Door | Prize | Changep | Ttp | Flipp | Ottp | No changep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 66.645 | 55.585 | 50.061 | 44.415 | 33.355 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 37.545 | 31.857 | 31.278 | 30.005 | 24.992 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 75 | 66.686 | 62.54 | 60.013 | 49.993 |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 26.704 | 23.5 | 23.35 | 22.854 | 19.979 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 53.287 | 47.463 | 46.657 | 45.705 | 40.047 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 | 80.014 | 73.354 | 69.997 | 68.534 | 59.99 |

| 7 | 6 | 1 | 20.86 | 18.802 | 18.791 | 18.505 | 16.649 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 | 41.67 | 37.76 | 37.493 | 37.015 | 33.303 |

| 9 | 6 | 3 | 62.565 | 57.244 | 56.253 | 55.6 | 50.053 |

| 10 | 6 | 4 | 83.273 | 77.724 | 75.042 | 74.074 | 66.719 |

| 11 | 7 | 1 | 17.155 | 15.756 | 15.767 | 15.591 | 14.286 |

| 12 | 7 | 2 | 34.268 | 31.582 | 31.477 | 31.138 | 28.581 |

| 13 | 7 | 3 | 51.457 | 47.512 | 47.114 | 46.796 | 42.892 |

| 14 | 7 | 4 | 68.592 | 63.727 | 62.917 | 62.387 | 57.163 |

| 15 | 7 | 5 | 85.661 | 80.856 | 78.553 | 77.89 | 71.399 |

| 16 | 8 | 1 | 14.564 | 13.591 | 13.562 | 13.408 | 12.49 |

| 17 | 8 | 2 | 29.171 | 27.15 | 27.097 | 26.916 | 25.009 |

| 18 | 8 | 3 | 43.77 | 40.764 | 40.609 | 40.408 | 37.492 |

| 19 | 8 | 4 | 58.368 | 54.537 | 54.252 | 53.886 | 49.989 |

| 20 | 8 | 5 | 72.953 | 68.614 | 67.716 | 67.327 | 62.504 |

| 21 | 8 | 6 | 87.511 | 83.353 | 81.251 | 80.743 | 74.955 |

| 22 | 9 | 1 | 12.709 | 11.932 | 11.919 | 11.793 | 11.063 |

| 23 | 9 | 2 | 25.378 | 23.882 | 23.85 | 23.712 | 22.286 |

| 24 | 9 | 3 | 38.05 | 35.79 | 35.62 | 35.541 | 33.302 |

| 25 | 9 | 4 | 50.793 | 47.765 | 47.603 | 47.438 | 44.429 |

| 26 | 9 | 5 | 63.514 | 59.971 | 59.574 | 59.209 | 55.543 |

| 27 | 9 | 6 | 76.224 | 72.26 | 71.459 | 71.043 | 66.624 |

| 28 | 9 | 7 | 88.856 | 85.161 | 83.35 | 82.965 | 77.803 |

| 29 | 10 | 1 | 11.263 | 10.659 | 10.663 | 10.589 | 9.974 |

| 30 | 10 | 2 | 22.496 | 21.287 | 21.273 | 21.272 | 20.021 |

| 31 | 10 | 3 | 33.796 | 31.901 | 31.856 | 31.801 | 29.957 |

| 32 | 10 | 4 | 44.983 | 42.591 | 42.497 | 42.38 | 40.009 |

| 33 | 10 | 5 | 56.281 | 53.328 | 53.151 | 52.905 | 49.971 |

| 34 | 10 | 6 | 67.475 | 64.136 | 63.734 | 63.504 | 59.945 |

| 35 | 10 | 7 | 78.761 | 75.157 | 74.413 | 74.125 | 69.99 |

| 36 | 10 | 8 | 90.008 | 86.636 | 84.967 | 84.669 | 79.949 |

| No | Door | Prize | Changep | No changep | No changep | Flipp | Flipp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo | True | combined | |||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 66.645 | 33.355 | 33.333 | 50.061 | 49.989 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 37.545 | 24.992 | 25 | 31.278 | 31.273 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 75 | 49.993 | 50 | 62.54 | 62.5 |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 26.704 | 19.979 | 20 | 23.35 | 23.352 |

| 5 | 5 | 2 | 53.287 | 40.047 | 40 | 46.657 | 46.644 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 | 80.014 | 59.99 | 60 | 69.997 | 70.007 |

| 7 | 6 | 1 | 20.86 | 16.649 | 16.667 | 18.791 | 18.764 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 | 41.67 | 33.303 | 33.333 | 37.493 | 37.502 |

| 9 | 6 | 3 | 62.565 | 50.053 | 50 | 56.253 | 56.283 |

| 10 | 6 | 4 | 83.273 | 66.719 | 66.667 | 75.042 | 74.97 |

| 11 | 7 | 1 | 17.155 | 14.286 | 14.286 | 15.767 | 15.721 |

| 12 | 7 | 2 | 34.268 | 28.581 | 28.571 | 31.477 | 31.42 |

| 13 | 7 | 3 | 51.457 | 42.892 | 42.857 | 47.114 | 47.157 |

| 14 | 7 | 4 | 68.592 | 57.163 | 57.143 | 62.917 | 62.868 |

| 15 | 7 | 5 | 85.661 | 71.399 | 71.429 | 78.553 | 78.545 |

| 16 | 8 | 1 | 14.564 | 12.49 | 12.5 | 13.562 | 13.532 |

| 17 | 8 | 2 | 29.171 | 25.009 | 25 | 27.097 | 27.086 |

| 18 | 8 | 3 | 43.77 | 37.492 | 37.5 | 40.609 | 40.635 |

| 19 | 8 | 4 | 58.368 | 49.989 | 50 | 54.252 | 54.184 |

| 20 | 8 | 5 | 72.953 | 62.504 | 62.5 | 67.716 | 67.727 |

| 21 | 8 | 6 | 87.511 | 74.955 | 75 | 81.251 | 81.256 |

| 22 | 9 | 1 | 12.709 | 11.063 | 11.111 | 11.919 | 11.91 |

| 23 | 9 | 2 | 25.378 | 22.286 | 22.222 | 23.85 | 23.8 |

| 24 | 9 | 3 | 38.05 | 33.302 | 33.333 | 35.62 | 35.692 |

| 25 | 9 | 4 | 50.793 | 44.429 | 44.444 | 47.603 | 47.619 |

| 26 | 9 | 5 | 63.514 | 55.543 | 55.556 | 59.574 | 59.535 |

| 27 | 9 | 6 | 76.224 | 66.624 | 66.667 | 71.459 | 71.446 |

| 28 | 9 | 7 | 88.856 | 77.803 | 77.778 | 83.35 | 83.317 |

| 29 | 10 | 1 | 11.263 | 9.974 | 10 | 10.663 | 10.632 |

| 30 | 10 | 2 | 22.496 | 20.021 | 20 | 21.273 | 21.248 |

| 31 | 10 | 3 | 33.796 | 29.957 | 30 | 31.856 | 31.898 |

| 32 | 10 | 4 | 44.983 | 40.009 | 40 | 42.497 | 42.492 |

| 33 | 10 | 5 | 56.281 | 49.971 | 50 | 53.151 | 53.141 |

| 34 | 10 | 6 | 67.475 | 59.945 | 60 | 63.734 | 63.738 |

| 35 | 10 | 7 | 78.761 | 69.99 | 70 | 74.413 | 74.381 |

| 36 | 10 | 8 | 90.008 | 79.949 | 80 | 84.967 | 85.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).