Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- a statistical space of blueprints (statistical degrees of freedom, sDoF), carrying the variables that describe preparations, control knobs, and intended states;

- a physical space of responses (physical degrees of freedom, pDoF), carrying the variables that describe actual readouts, fields, or detector states;

- a calibration map , which tells us, for each blueprint , what the ideal response in would be if the device were perfectly implemented; and

- an instrument weight on , which encodes how the instrument “measures distance” between two responses via the norm .

- (Q1)

- Channels. Can DSFL be realised as a genuine Lyapunov law for finite–dimensional quantum channels, with admissibility exactly equivalent to a spectral data–processing condition in a fixed instrument norm?

- (Q2)

- (Q3)

1.1. Main Idea and Contributions

- C1

-

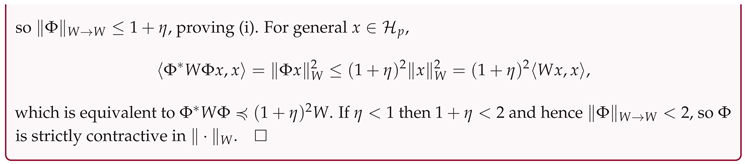

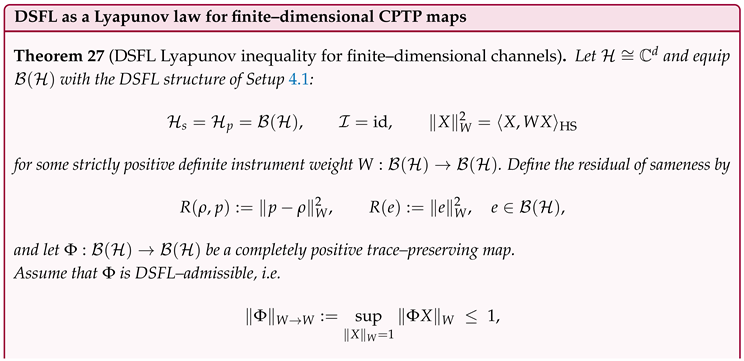

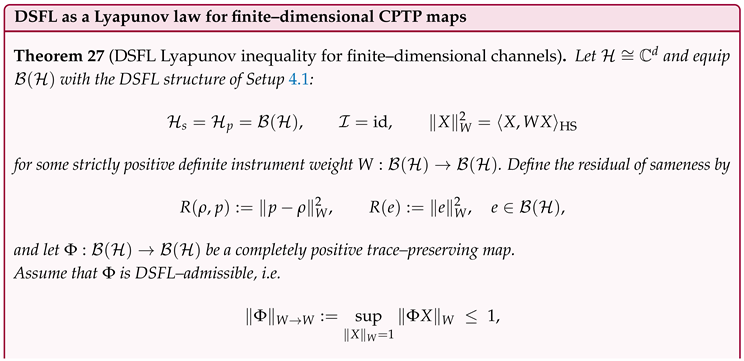

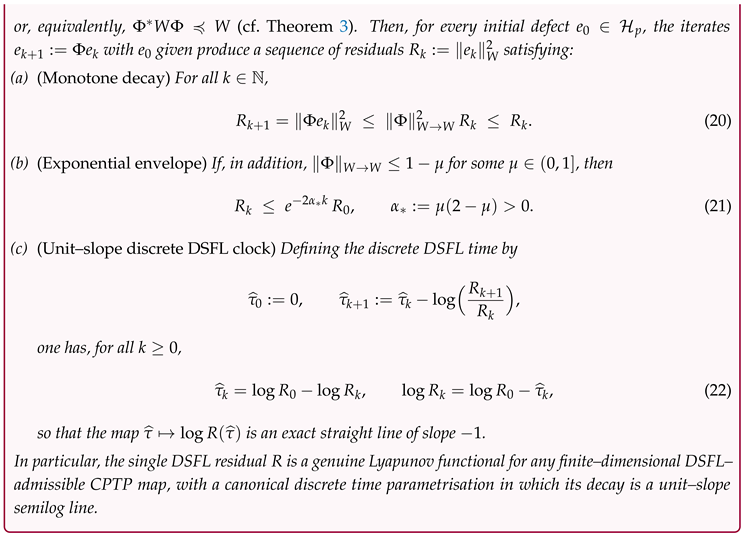

DSFL as a Lyapunov/DPI law for channels. In a finite–dimensional quantum sector we fix an SPD instrument weight W on and define admissibility of a channel via the induced normWe prove thati.e. admissibility is exactly equivalent to a spectral data–processing inequality for the single residual, and we show that in DSFL time the semilog envelope of has unit slope.

- C2

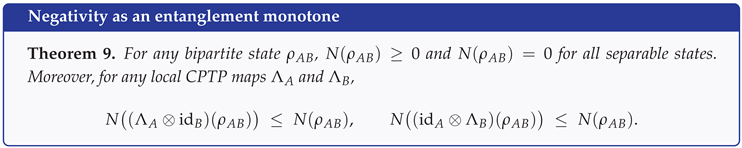

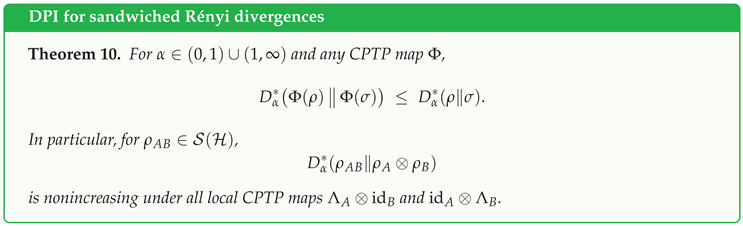

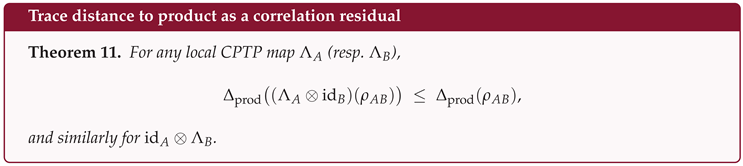

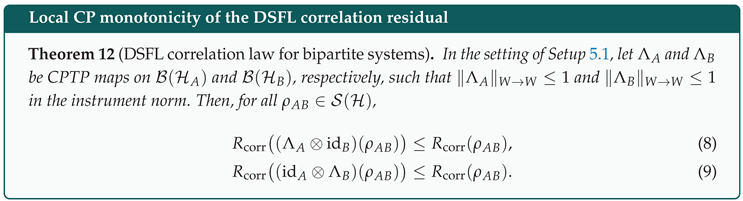

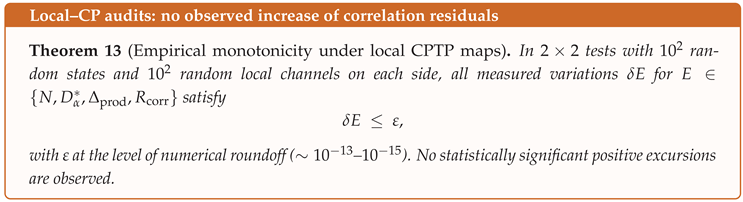

- Entanglement proxies as DSFL correlation residuals. On bipartite systems we interpret: (i) negativity,[13] (ii) sandwiched Rényi divergences ,14,15] and (iii) trace distance , as DSFL–style correlation residuals. We recall their monotonicity under local CPTP maps and support this with numerical audits using random states and random local channels.[3,4] In DSFL language this becomes a “no hidden gain in correlations’’ law for local admissible dynamics.

- C3

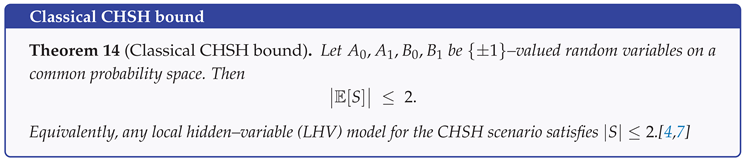

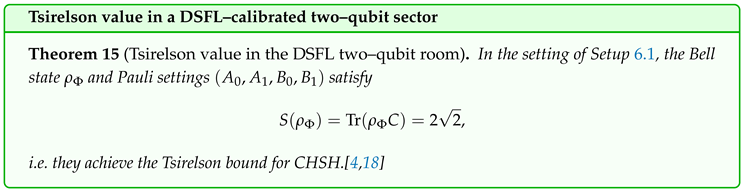

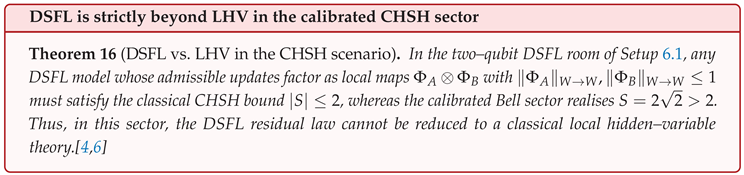

- Bell tests inside a DSFL room. We embed CHSH and GHZ/Mermin inequalities [7,17,18] into DSFL–calibrated qubit sectors. On the classical side we explicitly enumerate all deterministic LHV assignments in the CHSH scenario and confirm the classical bound [4]. On the DSFL side we calibrate a two–qubit sector to a Bell state and Pauli measurements and recover the quantum value . We further show that a three–qubit GHZ sector yields a Mermin value , again in agreement with standard quantum predictions and strictly beyond all LHV models [17,18]. In this sense the DSFL residual law is strictly beyond classical local hidden–variable theories in the calibrated finite–dimensional sector.

1.2. Outline

2. Positioning and Relation to Prior Work

2.1. Synthesis, Not Reinvention

2.2. Geometry of Information: Angles, Projections, and Alternating Schemes

2.3. Data Processing and Lyapunov Structure

2.4. Uncertainty: Variance, Entropic, and Geometric Viewpoints

2.5. Collapse, Instruments and POVMs

2.6. Locality and Finite Speed

2.7. Contextuality, EPR/Bell, and Tsirelson Bounds

2.8. Operator–Algebraic and Spectral Backdrop

2.9. Holography and Boundary Perspectives (Motivation Only)

2.10. Summary

3. DSFL Framework in a Single Hilbert Room

3.1. Ambient Geometry, Calibration, and Instrument Norm

- a bounded linear map (the calibration or interchangeability map), which sends blueprints to ideal responses ;

- a bounded, selfadjoint, strictly positive operator (the instrument weight ), inducing the W–inner product and norm

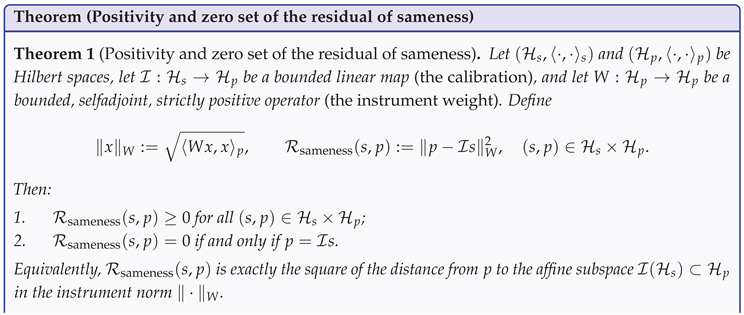

3.2. Residual of Sameness and Positivity

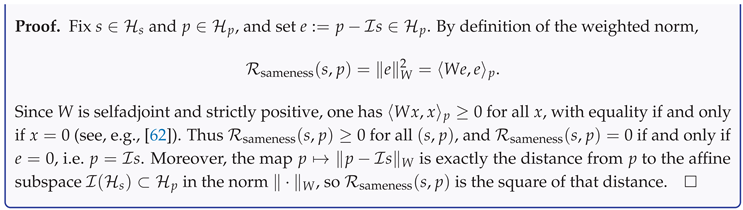

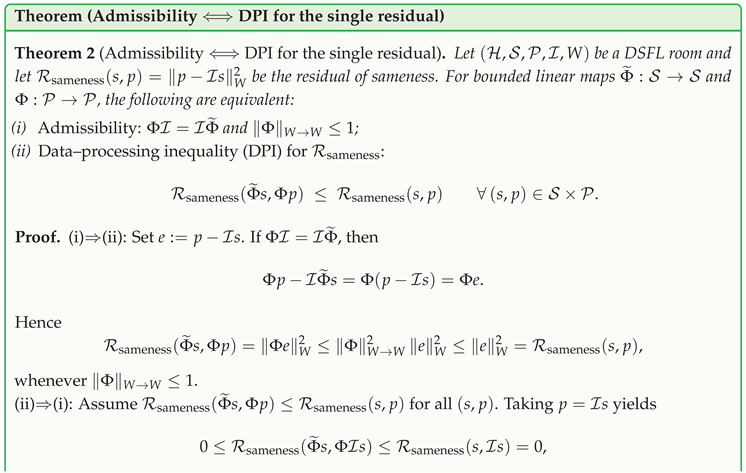

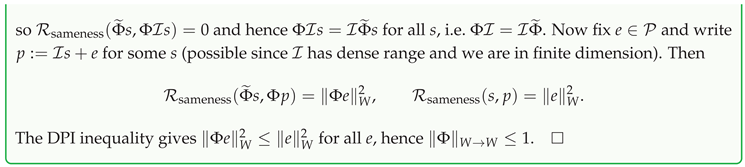

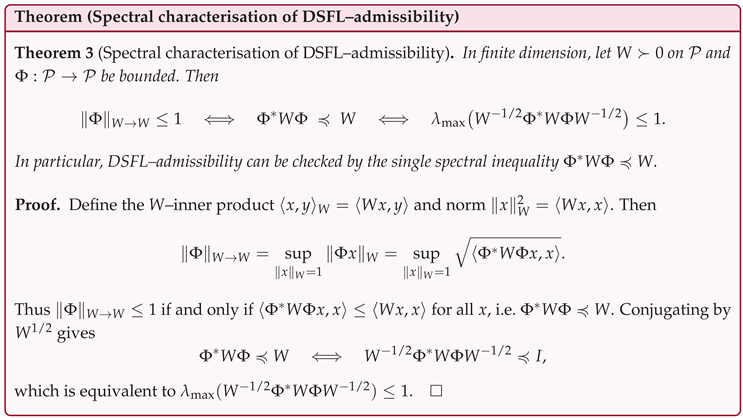

3.3. Admissible Updates and DPI Equivalence

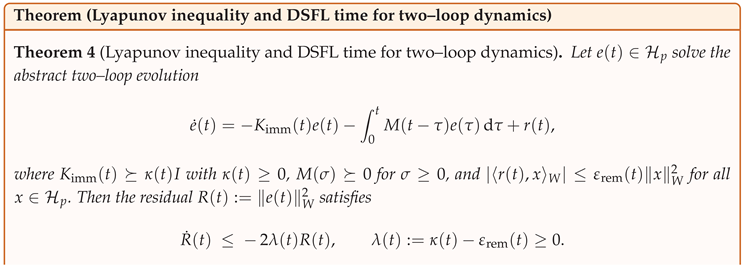

3.4. Two–Loop Continuous Law and DSFL Time

4. Finite–Dimensional Quantum Channels

4.1. DSFL Room for Channels and Admissible CPTP Maps

4.2. Discrete Lyapunov Envelope and DSFL Clock

4.3. Numerical Audits for Channels

- DPI / spectral audits. For a given instrument weight W and channel , we compute the largest eigenvalue . If the map is not DSFL–admissible and one can find explicit defects e with ; if (up to numerical tolerance) the DPI for R is satisfied. This is the basic “admissible / nonadmissible’’ test for finite–dimensional channels.

- Envelope fits in DSFL time. For a DSFL–admissible channel, we generate a sequence , record , and form the discrete DSFL time . A linear regression of versus confirms, to numerical precision, the unit–slope relation implied by Theorem 6.

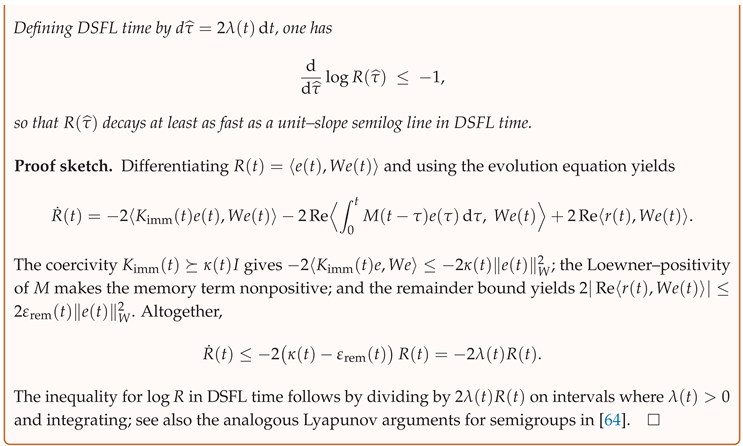

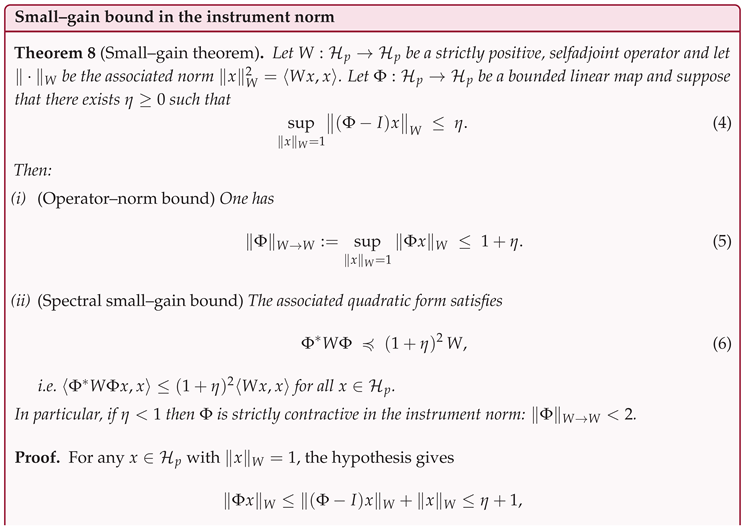

- Small–gain / robustness estimates. In applications one often has a numerical bound of the form The small–gain theorem (Theorem 8) then yields the quantitative estimates and which quantify how close is to being DSFL–admissible and how tight the Lyapunov envelope remains. This is what we use to interpret noisy or approximate implementations of DSFL channels.

5. Entanglement and Correlation Residuals

5.1. Bipartite DSFL Room, Separable vs. Entangled

5.2. Standard Correlation Functionals

5.3. DSFL Correlation Residual and Local CP Monotonicity

5.4. Numerical Local–CP Audits

- random states by sampling with i.i.d. complex Gaussian entries and setting ;

- random local CPTP maps , by sampling Kraus operators and normalising .

6. Bell Tests in a DSFL Room

6.1. Classical CHSH Bound

6.2. DSFL Calibration and Tsirelson Value

6.3. DSFL vs. Local Hidden–Variable Models

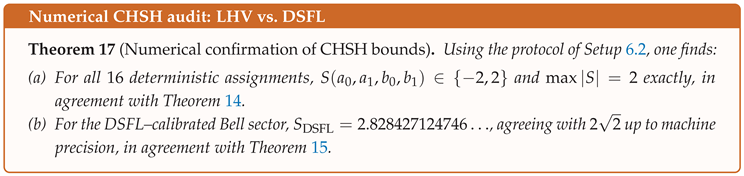

6.4. Numerical CHSH Audit

- LHV side: enumerate all deterministic assignments and compute

- DSFL/quantum side: build the matrices for and in the computational basis and evaluate

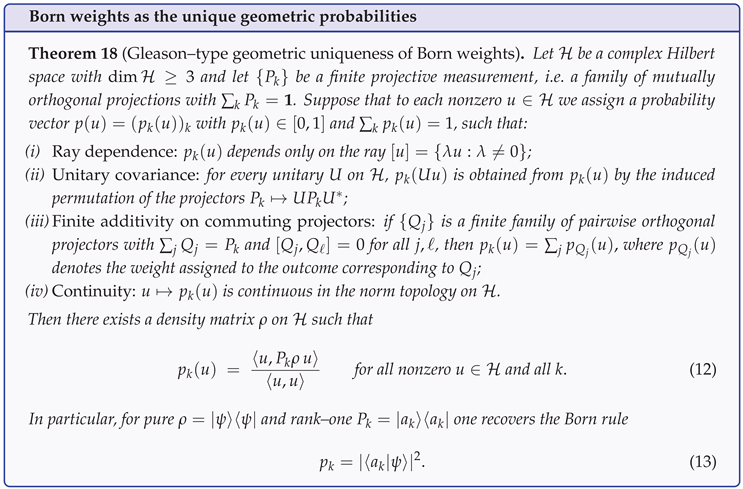

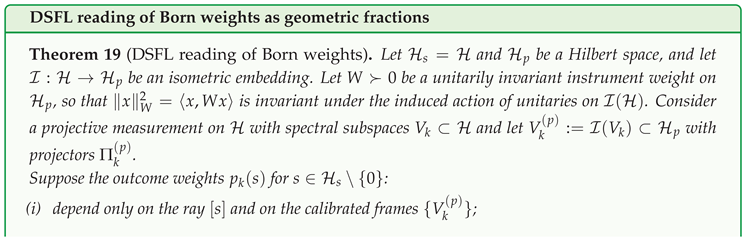

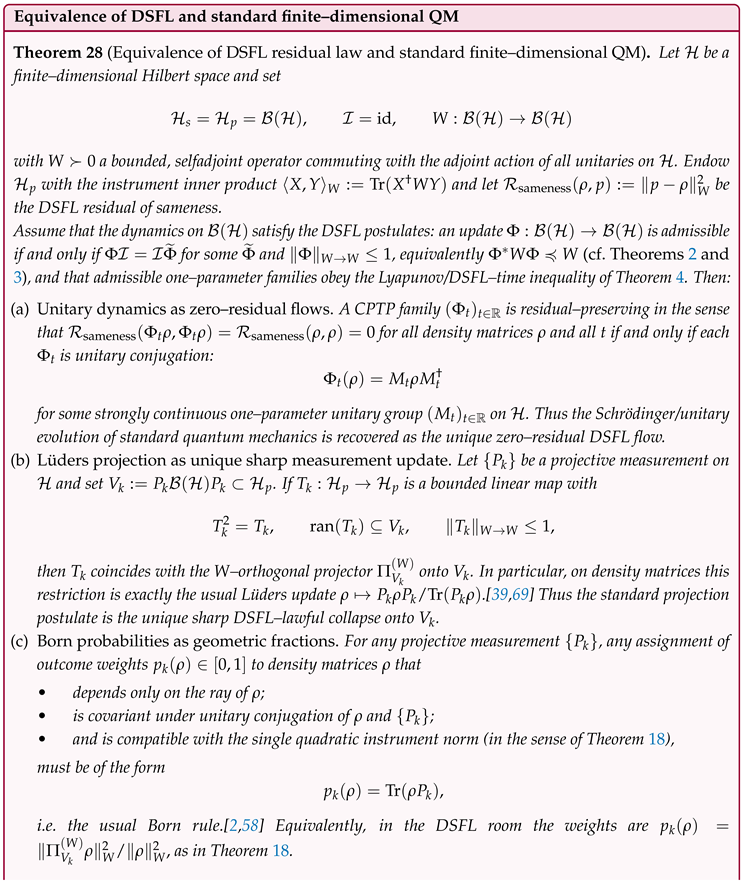

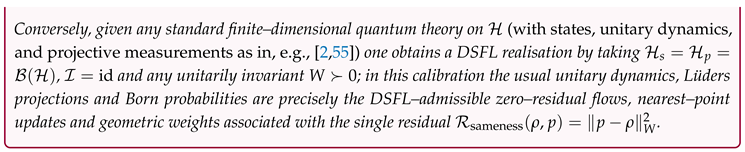

7. Born Rule, Projection, and Comparison with Standard QM

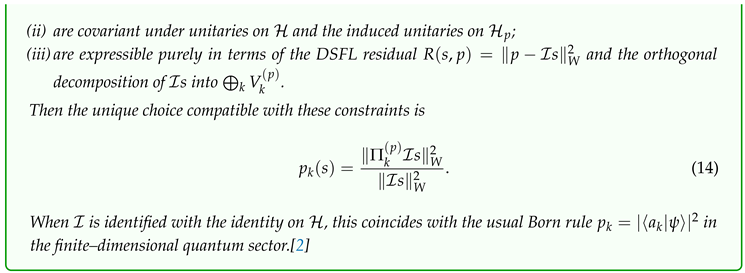

- Born weights arise as geometric fractions of a single quadratic norm in the DSFL room, in line with Gleason’s characterisation of frame–covariant probability measures.[58]

- In finite dimension, DSFL reproduces all standard quantum structures (unitary dynamics, projection, Born rule), while adding a global Lyapunov/DPI law and a single residual as the common “meter” for admissibility and locality.

7.1. Born Weights as Geometric Fractions

7.2. Nearest–Point Collapse and Lüders Uniqueness

8. Numerical Audits of the DSFL Law in a Finite–Dimensional Testbed

- DPI and nonexpansiveness for random and DSFL–designed channels in general instrument weights W;

- Lyapunov envelopes for iterated channels, verifying the unit–slope property in the discrete DSFL clock;

- Cone locality for relay dynamics on a discretised one–dimensional lattice;

- Local CP monotonicity for bipartite entanglement proxies and for the DSFL correlation residual under random local channels;

- CHSH sweeps confirming the classical bound 2 for LHV models and the Tsirelson value in the DSFL–calibrated Bell sector.

8.1. Cone Locality: Analytic Cone Bound

8.2. DPI Spectral Audit for Random Maps

- a random SPD weight W by sampling a Gaussian matrix G and setting with to ensure positivity;

- a random linear map Φ by sampling a complex Gaussian matrix and normalising its Hilbert–Schmidt norm to a prescribed scale.

- (a)

- for generic random maps Φ, one typically finds (often in the range –), and explicit vectors x with ;

- (b)

- for maps constructed as with B rescaled so that , one consistently finds and no violations within numerical precision.

8.3. Lyapunov Envelope Audit

8.4. Cone Locality Audit for Relay Dynamics

- (a)

- the front position , defined as the minimal radius with for small ε, grows approximately linearly in t; the fitted front speed scales linearly with and remains finite;

- (b)

- for fixed t, a regression of versus yields a negative slope , with increasing as ξ decreases; all such fits have .

8.5. Local CP Monotonicity Audits

- random two–qubit states by sampling with i.i.d. complex Gaussian entries and setting ;

- for each , random local CPTP maps by sampling Kraus operators and setting with .[2]

8.6. CHSH Audit: Classical vs. DSFL Quantum

- Classical side. Enumerate all deterministic LHV assignments and evaluate Record .

- DSFL/quantum side. In the calibrated two–qubit DSFL room of Setup 6.1, construct matrix representations of and in the computational basis, form the CHSH operator C, and compute

- (a)

- for all 16 deterministic LHV assignments one finds and , in agreement with Theorem 14;

- (b)

- for the DSFL–calibrated Bell sector one obtains , agreeing with up to machine precision, in agreement with Theorem 15.

8.7. Summary of Numerical Evidence

9. Structural DSFL Theorems in Finite Dimensions

- a Lyapunov law for completely positive trace–preserving (CPTP) maps, showing that every DSFL–admissible channel is automatically contractive for the residual of sameness and admits a rigid, unit–slope decay profile in an intrinsic “DSFL time”;

- an equivalence theorem stating that, in finite dimensions, the usual unitary dynamics, Lüders projections and Born rule of quantum mechanics are precisely the DSFL–lawful evolutions and measurements for a natural choice of instrument norm.

9.1. DSFL as a Lyapunov Law for Finite–Dimensional Channels

9.2. Discussion

9.3. Equivalence with Standard Finite–Dimensional Quantum Mechanics

9.4. Discussion

10. Concluding Discussion and Outlook

11. Author’s Note

12. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Notation (Symbols Only)

| Symbol | Type / Domain | Meaning / Assumptions |

| Ambient Hilbert geometry (“one room”) | ||

| Hilbert space | Common comparison space with inner product and norm | |

| Closed subspaces | Statistical (blueprint, sDoF) and physical (response, pDoF) arenas | |

| Projections | Orthogonal projectors onto , | |

| Linear map | Calibration / interchangeability map (blueprint → ideal response) | |

| Closed subspace | Coherent image of on the physical side (after closure) | |

| Projection | Orthogonal projector onto U | |

| SPD operator | Instrument weight; induces instrument inner product and norm | |

| Norm | Instrument norm on , associated with W | |

| States, channels, duals | ||

| Hilbert space | Finite–dimensional quantum system, typically | |

| Operator space | Bounded operators / matrices on | |

| State space | Density matrices with | |

| Operators | Quantum states in | |

| Linear map | Quantum channel (CPTP) or general linear update on | |

| Linear map | Hilbert–Schmidt adjoint of | |

| Operator norm | Induced norm ; admissibility requires | |

| Operators | Kraus operators of a CPTP channel, | |

| Residual of sameness and defects | ||

| Vector | Statistical (blueprint, sDoF) state | |

| Vector | Physical (response, pDoF) state | |

| Vector in | Calibrated mismatch (defect, residual direction) | |

| or | Scalar | Residual of sameness: |

| Nonnegative scalar | Residual magnitude; e.g. half–width of band tests | |

| Symbol | Type / Domain | Meaning / Assumptions |

| Frames, projectors, angles | ||

| Closed subspace | Measurement / reconstruction / constraint frame | |

| Projection | Orthogonal projector onto V (in the ambient inner product) | |

| Closed subspace | Spectral frame of observable A (after graph transport) | |

| Angle | Friedrichs angle; | |

| Scalar in | Overlap constant | |

| Closed subspace | Closed linear span of two frames , | |

| Variance and graph transport (when used) | ||

| Operator | Centered observable: | |

| Isomorphism | Graph–norm isomorphism | |

| Closed subspace | A–frame in after graph transport | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Standard deviation: | |

| Admissibility, DPI, and operators | ||

| Linear map | Statistical update (blueprint side) | |

| Linear map | Physical update (response side) | |

| Identity | Intertwining (coherent blueprint → coherent response) | |

| Operator inequality | Spectral DPI / nonexpansiveness in | |

| admissible | Property | and (iff DPI for R) |

| Inequality | Data–processing for the single observable R | |

| Two–loop dynamics and DSFL time | ||

| Trajectory in | Time–dependent residual | |

| Operator on | Immediate loop generator; selfadjoint, | |

| Operator kernel | Retarded, Loewner–positive memory kernel for | |

| Vector in | Remainder; | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Coercivity bound: | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Remainder bound in the Lyapunov inequality | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Instantaneous decay rate (envelope rate) | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Residual energy in time | |

| Scalar (time) | DSFL time via ; unit–slope clock | |

| Symbol | Type / Domain | Meaning / Assumptions |

| Causality & cone parameters (relay loop) | ||

| c | Speed constant | Sharp causal speed (instrument light–cone speed) |

| Semigroup on | Relay evolution; cone bound with margin | |

| Projection/localizer | Projection onto observables / defects supported in region O | |

| Length/time margin | Cone sharpness in | |

| Cutoff (bandwidth) | UV regulator; typically | |

| Finite–dimensional quantum sector | ||

| Hilbert spaces | Local qubit / qudit spaces, typically , | |

| Hilbert space | Tensor product | |

| Density matrix | Bipartite state on | |

| Density matrices | Reduced states: , | |

| Density matrix | Bell state in two–qubit sector | |

| Partial transpose | Transposition on subsystem B in a fixed basis | |

| Entanglement / correlation proxies | ||

| Scalar | Negativity: | |

| Scalar | Sandwiched Rényi divergence to product form | |

| Scalar | Trace–distance to product: | |

| Scalar | DSFL correlation residual | |

| Bell / CHSH notation | ||

| Observables | Local dichotomic () observables on | |

| Observables | Local dichotomic () observables on | |

| C | Operator | CHSH operator |

| Scalar | CHSH value | |

| Scalar | Classical (local hidden–variable) CHSH value; | |

| Scalar | DSFL / quantum CHSH value; (Tsirelson bound) | |

| Miscellaneous symbols | ||

| Norm | Ambient norm (context may indicate operator / trace norm) | |

| Inner product | Ambient inner product | |

| Loewner order | Positive semidefinite operator: for all x | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Distance of x to subspace V in | |

Master Definitions — Compact Longtable

| Entry | Definition / Formula | Role / Notes |

| Ambient Hilbert geometry (“one room”) | ||

| Instrument room | , | Single calibrated space for all DSFL audits (channels, entanglement, Bell) |

| Blueprint / response | (closed) | Statistical blueprints (sDoF) and physical readouts (pDoF) |

| Calibration | (bounded, linear) | Interprets blueprints as ideal responses; coherent image |

| Instrument weight | , | Defines instrument inner product and norm |

| Frames | , projector | Measurement / reconstruction / constraint subspaces |

| Angles | via | Geometry of what a frame can “see” from U |

| Single observable (“one residual”) | ||

| Residual of sameness | Only scalar used for DPI, Lyapunov rates, and audits | |

| Residual direction | Carries all mismatch / budget; | |

| DPI / admissibility | Iff and (spectral DPI) | |

| Spectral test | Equivalent operator inequality for nonexpansiveness in | |

| Nearest point (collapse as mechanism) | ||

| Orthogonal projector | Idempotent, nonexpansive, range V; DSFL–lawful sharp update | |

| Lüders uniqueness | , , | Collapse = unique DSFL–admissible nearest point onto V (no extra postulate) |

| Two–loop law & DSFL time (“one ruler”) | ||

| Immediate loop | , | Time–local contraction of the defect |

| Relay (memory) | Retarded for | Finite–speed transport of mismatch across the room |

| Envelope rate | Printed decay rate in | |

| DSFL clock | Time parametrisation with unit–slope semilog envelope | |

| Unit slope | In DSFL time, vs. is a line of slope (or steeper) | |

| Locality from relay (cone bounds) | ||

| Cone speed | Emergent signal / light–cone speed in the instrument norm | |

| Cone margin | Smearing scale; sharper cone as cutoff | |

| Instrument cone | Causality constraint for relay dynamics in the DSFL room | |

| Entry | Definition / Formula | Role / Notes |

| Finite–dimensional quantum sector | ||

| Single system | , | Finite–dimensional Hilbert space and operator algebra |

| State space | Density matrices (positive, trace one) | |

| Channel | Completely positive trace–preserving (CPTP) map | |

| Admissible channel | DSFL–lawful evolution (single–residual DPI holds) | |

| Bipartite systems and entanglement | ||

| Bipartite space | Two–party quantum system (qubits / qudits) | |

| Reductions | , | Local states of A and B |

| Separable state | Admits a classical mixture of product states | |

| Entangled state | not separable | Cannot be written as convex combination of product states |

| Negativity | Entanglement measure; monotone under local CPTP maps | |

| Rényi corr. residual | Sandwiched Rényi divergence to product form | |

| Trace corr. residual | Trace–distance to product state | |

| DSFL corr. residual | Correlation part of the DSFL mismatch (nonlocal budget) | |

| Bell tests (CHSH sector) | ||

| Local observables | on A, on B | Dichotomic () measurements per party |

| CHSH operator | Defines | |

| Classical bound | Local hidden–variable constraint (polytope inequality) | |

| Tsirelson bound | Maximal quantum / DSFL CHSH value in calibrated two–qubit sector | |

| Bell state | Saturates Tsirelson bound with suitable | |

| Born weights and frequencies (geometric content) | ||

| Born weights | Unique DSFL–compatible outcome weights in a projective frame | |

| Collapse map | Sharp Lüders update = nearest point in the instrument norm | |

| DSFL LLN (sketch) | Deterministic law of large numbers turning geometric weights into frequencies | |

| Entry | Definition / Formula | Role / Notes |

| Falsification / stress tests (device level) | ||

| Unit–slope test | Upper convex hull of has slope | Fails if non–admissible steps or miscalibrated DSFL clock |

| Cone test | No response for , tails | Violations indicate superluminal or nonlocal relay evolution |

| Band test | One–/two–frame bands tighten under DPI | Dimension–free audit of calibration, frames, and nonexpansiveness |

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Crépeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W.K. Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen Channels. Physical Review Letters 1993, 70, 1895–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Horodecki, R.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, K. Quantum Entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics 2009, 81, 865–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, N.; Cavalcanti, D.; Pironio, S.; Scarani, V.; Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 419–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Physical Review 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics 1964, 1, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Physical Review Letters 1969, 23, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Dalibard, J.; Roger, G. Experimental Test of Bell’s Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers. Physical Review Letters 1982, 49, 1804–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, V.; Kossakowski, A.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of N-level systems. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1976, 17, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.P.; Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Vidal, G.; Werner, R.F. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 65, 032314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M"uller-Lennert, M.; Dupuis, F.; Szehr, O.; Fehr, S.; Tomamichel, M. On quantum Rényi entropies: A new generalization and some properties. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2013, 54, 122203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomamichel, M. A Framework for Non-Asymptotic Quantum Information Theory. Foundations and Trends in Information Theory 2016, 11, 119–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Discussion of Probability Relations between Separated Systems. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1935, 31, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermin, N.D. Quantum Mechanics: Concepts and Applications; Prentice Hall, 1990.

- Cirel’son, B.S. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1980, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. Essai sur la géométrie à n dimensions. Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France.

- Friedrichs, K. On Certain Inequalities and Characteristic Angles. Annals of Mathematics.

- Lüders, G. Über die Zustandsänderung durch den Meßprozeß. Annalen der Physik 1951, 443, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. Completely Positive Maps and Entropy Inequalities. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 40, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, A. Relative Entropy and the Wigner–Yanase–Dyson Skew Information. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1977, 54, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petz, D. Monotonicity of quantum relative entropy revisited. Quantum Information & Computation 2003, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.; Kahan, W.M. The Rotation of Eigenvectors by a Perturbation. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 1970, 7, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik; Springer: Berlin, 1932. English translation by R. T. Beyer: Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, I. The Product of Projection Operators. Acta Scientiarum Mathematicarum (Szeged) 1962, 23, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, F. The method of alternating orthogonal projections. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1965, 118, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Borwein, J.M. On Projection Algorithms for Solving Convex Feasibility Problems. SIAM Review 1996, 38, 367–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, F.; Hundal, H. The Rate of Convergence for the Method of Alternating Projections. Journal of Approximation Theory 2006, 141, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1927, 43, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.P. The Uncertainty Principle. Physical Review 1929, 34, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Zum Heisenbergschen Unschärfeprinzip. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse.

- Hirschman, I. I., J. A Note on Entropy. American Journal of Mathematics 1957, 79, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckner, W. Inequalities in Fourier Analysis. Annals of Mathematics 1975, 102, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białynicki-Birula, I.; Mycielski, J. Uncertainty Relations for Information Entropy in Wave Mechanics. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 44, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.; Lahti, P.; Werner, R.F. Measurement Uncertainty Relations. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2014, 55, 042111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.; Lahti, P.; Werner, R.F. Colloquium: Quantum Root-Mean-Square Error and Measurement Uncertainty Relations. Reviews of Modern Physics 2014, 86, 1261–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, H.; Uffink, J.B.M. Generalized Entropic Uncertainty Relations. Physical Review Letters 1988, 60, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M. Universally valid reformulation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle on noise and disturbance in measurement. Physical Review A 2003, 67, 042105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimark, M.A. Spectral functions of a symmetric operator. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR. Seriya Matematicheskaya 1940, 4, 277–318. [Google Scholar]

- Stinespring, W.F. Positive functions on C*-algebras. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1955, 6, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieb, E.H.; Robinson, D.W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1972, 28, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, M.B. Lieb–Schultz–Mattis in higher dimensions. Physical Review B 2004, 69, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravyi, S.; Hastings, M.B.; Verstraete, F. Lieb–Robinson bounds and the generation of correlations and topological quantum order. Physical Review Letters 2006, 97, 050401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtergaele, B.; Sims, R. Lieb–Robinson bounds and the exponential clustering theorem. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2006, 265, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, R. Local Quantum Physics: Fields, Particles, Algebras, ed., 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisognano, J.J.; Wichmann, E.H. On the Duality Condition for a Hermitian Scalar Field. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1975, 16, 985–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratteli, O.; Robinson, D.W. Operator Algebras and Quantum Statistical Mechanics I, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesaki, M. Theory of Operator Algebras II; Vol. 125, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, M.; Petz, D. Quantum Entropy and Its Use; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kochen, S.; Specker, E.P. The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1967, 17, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirelson, B.S. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1980, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik; Springer: Berlin, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M.H. Linear transformations in Hilbert space. III. Operational methods and group theory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1930, 16, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Die Eindeutigkeit der Schrödingerschen Operatoren. Mathematische Annalen 1931, 104, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, A.M. Measures on the Closed Subspaces of a Hilbert Space. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1957, 6, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.M. The Large N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1998, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic Derivation of Entanglement Entropy from AdS/CFT. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 181602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raamsdonk, M.V. Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement. General Relativity and Gravitation 2010, 42, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics II: Fourier Analysis, Self-Adjointness; Academic Press: New York, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces, 2 ed.; Springer: Cham, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazy, A. Semigroups of Linear Operators and Applications to Partial Differential Equations; Vol. 44, Applied Mathematical Sciences, Springer: New York, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrous, J. The Theory of Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis; Vol. 169, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, K. General state changes in quantum theory. Annals of Physics 1971, 64, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author, A. Title of the Wilde Renyi DPI Paper. Journal Name.

- Lueders, G. Title Placeholder. Journal Placeholder 1951, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Author, A. Title of the DSFL Flagship Paper. Journal Name 2024, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. Stability Theory of Differential Equations; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gripenberg, G.; Londen, S.O.; Staffans, O. Volterra Integral and Functional Equations; Vol. 34, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems, 3 ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, E.D. Input to State Stability: Basic Concepts and Results. In Nonlinear and Optimal Control Theory; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dafermos, M.; Rodnianski, I. The red-shift effect and radiation decay on black hole spacetimes. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 2009, 62, 859–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).