1. Introduction

The global railway sector is a cornerstone of economic development, essential for the large-scale transport of freight and passengers. In an era of escalating environmental concerns and the urgent need for sustainable development, the industry is compelled to seek high-performance solutions that also minimize ecological footprint [

1,

2]. A primary focus of this pursuit is the track bed, particularly the sub-ballast layer, which plays a critical role in distributing loads, providing drainage, and protecting the subgrade [

3,

4]. The conventional use of virgin quarried materials for this layer is associated with high carbon emissions from extraction and transportation, depletion of natural resources, and significant environmental degradation.

Concurrently, various industrial processes generate substantial volumes of waste. The slate industry, a significant economic sector in countries like Brazil and Spain, produces vast amounts of waste—approximately 30% of the total extracted mass [

5]. This waste is typically stockpiled or landfilled near extraction sites, leading to land consumption, visual pollution, and potential contamination of soil and water resources [

6,

7]. The reuse of such Recycled Granular Materials (RGM) presents a promising pathway to mitigate these issues. RGMs generally have a significantly lower carbon footprint compared to traditional quarried materials, supporting the transition towards a more sustainable and circular economy [

8,

9].

The sub-ballast layer is fundamental to the long-term performance of a railway track. Located between the ballast and the subgrade, its main functions are to distribute stresses from traffic loads to prevent subgrade over-stressing, provide separation to prevent the intrusion of fine subgrade particles into the ballast (pumping), and facilitate drainage [

3,

10]. The material for this layer must possess adequate strength, stiffness (often characterized by the Resilient Modulus), and durability while meeting specific graduation requirements to ensure proper filtration and compaction [

11].

Traditionally, technical standards for sub-ballast materials have been conservative, often requiring high-quality crushed rock [

12]. This can make it difficult to find locally available materials that meet specifications, leading to increased costs and environmental impacts from long-distance transport [

13]. However, a growing body of research demonstrates the feasibility of using alternative and recycled materials. Studies have explored the use of recycled concrete aggregate, construction and demolition waste (CDW), rubber from tires, and industrial by-products like fly ash in both ballast and sub-ballast layers [

14,

15,

16,

17]. For instance, Indraratna et al. [

14] investigated the use of geogrids and recycled rubber in the ballast layer, while Ebrahimi and Keene [

15] studied mixtures of recycled ballast with recycled pavement materials and fly ash for sub-ballast applications, finding comparable or even improved mechanical behavior.

Despite this progress, research on the specific application of slate waste in railway sub-ballast remains limited. Previous studies on slate waste have primarily focused on its use in road pavements. Nunes et al. [

18] concluded that slate waste possesses adequate resilient properties, though its strength may not be as high as some primary aggregates. Other researchers have confirmed the potential of RGMs in general, with RM values often falling within the range of conventional materials [

19,

20]. The addition of RGM to soil mixtures has been shown to increase the RM and CBR significantly [

21,

22], which is a key indicator of performance for unbound pavement layers.

This research aims to fill a critical gap by providing a thorough laboratory investigation into the use of slate waste as a primary component in railway sub-ballast. The study will evaluate the physical, mechanical, and compaction characteristics of slate waste-clay soil mixtures across a range of proportions. The key parameters of CBR and RM will be analyzed in detail and compared against those of conventional gneiss aggregate mixtures. Furthermore, this work will contextualize its findings within the broader framework of railway sustainability, drawing parallels with successful applications of other recycled materials, such as fouled ballast [

1], and considering the specific challenges of constructing railways in tropical environments where moisture variation significantly influences performance [

23,

24]. The central hypothesis is that slate waste, when properly mixed and compacted, can exhibit mechanical properties that meet or exceed the requirements for railway sub-ballast, offering a technically sound and environmentally responsible alternative to conventional materials.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role and Requirements of the Railway Sub-Ballast

The railway track structure is a complex multi-layered system designed to withstand and distribute the dynamic loads from moving trains. The sub-ballast layer is a critical component of this structure, situated between the coarse ballast layer and the finer subgrade soil. Its importance is underscored by its multiple, and sometimes conflicting, functions as described in the literature.

Selig and Waters [

3] define the primary functions of the sub-ballast as: (i) distributing loads from the ballast to the subgrade to reduce vertical stress to a permissible level, (ii) preventing the intrusion of subgrade fines into the ballast layer (separation function), and (iii) providing lateral drainage for surface water that infiltrates the ballast. To achieve the separation and drainage functions, the sub-ballast must act as a filter between the ballast and the subgrade, a concept rooted in Terzaghi's filter criteria [

25]. This requires a well-graded material with a specific percentage of fines to prevent pumping, yet not so many as to impede drainage or increase water susceptibility [

12,

26].

However, other authors emphasize an alternative or additional function. Guimarães et al. [

2] and Stopatto [

27] suggest that in certain contexts, particularly when using fine-grained tropical soils, the sub-ballast should act as an impermeable or capillary barrier to protect the subgrade from surface water infiltration and erosion. This perspective highlights that the ideal characteristics of a sub-ballast can vary depending on the local climate, subgrade soil type, and overall track design philosophy.

International standards reflect these nuances. The American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) [

12] recommends that the sub-ballast should be "relatively impervious" to protect the subgrade, yet also notes its role in distributing load. European standards, such as those derived from UIC Code 719R, often emphasize the filter and drainage functions, specifying strict mechanical and graduation requirements [

28]. The choice of material is therefore a balancing act, requiring a careful evaluation of its properties against the specific site conditions and performance requirements.

2.2. Sustainable and Alternative Materials in Railway Infrastructure

The drive for sustainability has catalyzed extensive research into alternative materials for railway geotechnical layers. The overarching goals are to reduce the consumption of natural resources, repurpose waste materials, lower costs, and decrease the carbon footprint of railway construction and maintenance.

Recycled Ballast and Fouled Waste: A significant area of research focuses on reusing materials from the railway itself. Ballast deteriorates over time, becoming fouled with fine particles and losing its angularity. Instead of disposing of this spent ballast, researchers have investigated its potential for reuse. Castro et al. [

1] evaluated soils stabilized with recycled ballast fouled with iron ore for sub-ballast application. Using a non-linear elastic finite element model, they found that these stabilized materials showed significant potential, especially when combined with a small percentage (3%) of cement, reducing track displacements and subgrade stresses effectively. This approach is facilitated by advanced machinery like the Rail-mounted Formation Rehabilitation Machine, which can clean ballast and mix the waste with other materials in-situ to construct a new sub-ballast layer, offering higher productivity and lower emissions [

29,

30].

Other Industrial By-products and Recycled Aggregates: Beyond railway waste, other materials have been studied. Ebrahimi and Keene [

15] used recycled pavement materials with fly ash. Saborido Amate [

31] assessed blast furnace slag aggregates, noting their high durability and abrasion resistance. The use of recycled rubber tires mixed with gravel has been explored for its damping characteristics, which can reduce ballast degradation [

14]. Similarly, recycled concrete aggregate and construction and demolition waste have been successfully applied in road bases and sub-bases, with resilient modulus values often comparable to those of natural aggregates [

19,

20,

32].

The Case of Slate Waste: Slate waste is a specific industrial by-product that has received less attention in a railway context. Brazil is the world's second-largest producer of slate, with the state of Minas Gerais accounting for 90% of national production, generating about 0.6 million tons of waste annually [

5,

7]. Previous studies on its use in pavements are promising. Nunes et al. [

18] reported a resilient modulus of 272 MPa for slate waste under modified Proctor compaction, a value within the typical range for conventional granular materials.

2.3. Key Performance Indicators: CBR and Resilient Modulus

The mechanical evaluation of unbound granular materials for pavement layers relies heavily on two key parameters: the California Bearing Ratio and the Resilient Modulus.

The CBR is a penetration test used to empirically evaluate the mechanical strength of subgrades, sub-bases, and bases. It is a simple, widely used test that provides an index of a material's resistance to deformation. Many empirical design methods, including some historical railway design approaches, are based on CBR values [

33].

The Resilient Modulus, introduced by Hveem in 1955, is a more fundamental property that represents the elastic stiffness of a material under cyclic loading conditions that simulate traffic [

34]. It is defined as the ratio of the deviatoric stress to the recoverable (resilient) axial strain. Unlike the CBR, the RM accounts for the stress-dependent nature of granular materials and soils. Its behavior is often modeled using a non-linear constitutive relationship. A widely used model, adopted by AASHTO [

35], is the universal model (Equation 1):

RM = Resilient Modulus.

σ3 = Containment tension.

σd = Deviation tension.

K1, K2 e K3 = Experimental coefficients.

The RM is considered a superior input for mechanistic-empirical pavement design methods, as it more accurately captures the in-situ material response. For granular materials used in base and sub-ballast layers, RM values typically range from 100 MPa to 500 MPa [

36,

37]. The relationship between CBR and RM is known to be non-linear and material-dependent, though empirical correlations are often used in practice [

38].

2.4. The Influence of Moisture and Tropical Conditions

The performance of unbound layers is highly sensitive to moisture content. The railway track bed is continuously exposed to environmental actions, particularly precipitation, which can lead to moisture variation within the layers [

23]. This is especially critical in tropical regions, where heavy rainfall is common.

An increase in moisture content typically leads to a reduction in soil suction and a consequent decrease in the RM and shear strength of the material, potentially leading to increased permanent deformations [

24,

39]. Menezes et al. [

23] numerically simulated rainwater infiltration in a railway track and found that the moisture content in the sub-ballast could increase significantly above the optimum value, compromising its mechanical performance. This underscores the importance of selecting materials that are not only strong and stiff but also have favorable hydraulic properties—either draining water quickly or, in the case of fine-grained materials, maintaining strength under variable moisture conditions.

Lateritic soils, common in tropical countries like Brazil, have shown promise in this regard. Classified under the MCT system [

40], lateritic soils often exhibit stable mineralogy (e.g., kaolinite, iron oxides) that provides good mechanical behavior and low permeability, making them suitable for use as a capillary barrier in the sub-ballast layer [

2,

41]. The successful use of these soils in the Carajás Railway in Brazil [

1,

23] demonstrates that materials which may not meet traditional, conservative gradation specifications can perform excellently when their specific properties are properly understood and utilized.

This literature review establishes a clear rationale for the present study: to systematically evaluate slate waste, a plentiful and problematic industrial by-product, as a sustainable material for railway sub-ballast. By rigorously testing its mechanical properties (CBR, RM) and comparing them to conventional materials, and by contextualizing these findings within the broader movement towards sustainable and performance-based railway geotechnics, this research aims to provide a valuable contribution to both industry practice and academic knowledge.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material Characterization and Sampling

This research employed a comparative experimental methodology, investigating two distinct types of granular mixtures for sub-ballast application:

REF Mixtures (Reference): These served as the conventional benchmark and consisted of well-graded crushed gneiss aggregate, a material commonly used in pavement layers in Brazil, stabilized granulometrically with a local clayey soil.

SLT Mixtures (Slate Waste): These constituted the alternative sustainable solution and consisted of slate waste, obtained from a quarry in the state of Minas Gerais, mixed with the same clayey soil used in the REF mixtures.

The slate waste was collected directly from the stockpiles of a processing plant, representing the material typically destined for landfill. The clayey soil was collected from a site near potential railway construction projects. Both the gneiss aggregate and the slate waste were subjected to initial physical characterization.

The mixtures were prepared with varying proportions of granular material (gneiss or slate waste) and clayey soil, as detailed in

Table 1. This range of proportions allowed for the analysis of how the mechanical properties evolve with the increasing content of the granular skeleton.

3.2. Laboratory Testing Methods

A comprehensive suite of laboratory tests was performed to evaluate the compaction and mechanical characteristics of the ten mixtures (four REF and four SLT).

3.2.1. Compaction Test

The compaction characteristics—optimal moisture content (OMC) and maximum dry density (MDD)—were determined for all mixtures using the Modified Proctor energy (ASTM D1557 [

46]) to simulate the high compaction effort expected in heavy-haul railway construction. This test involved compacting specimens in a standard mold at different moisture contents to establish the compaction curve for each mixture.

3.2.2. California Bearing Ratio (CBR) Test

The CBR test was conducted according to DNIT-ME 172/2016 [

47] (similar to ASTM D1883). For each mixture, five identical specimens were compacted at their respective OMC and MDD (Modified Proctor). The specimens were then submerged in water for 96 hours to measure swell before being penetrated by a standard piston at a constant rate. The CBR value was calculated based on the stress required to achieve penetrations of 2.5 mm and 5.0 mm.

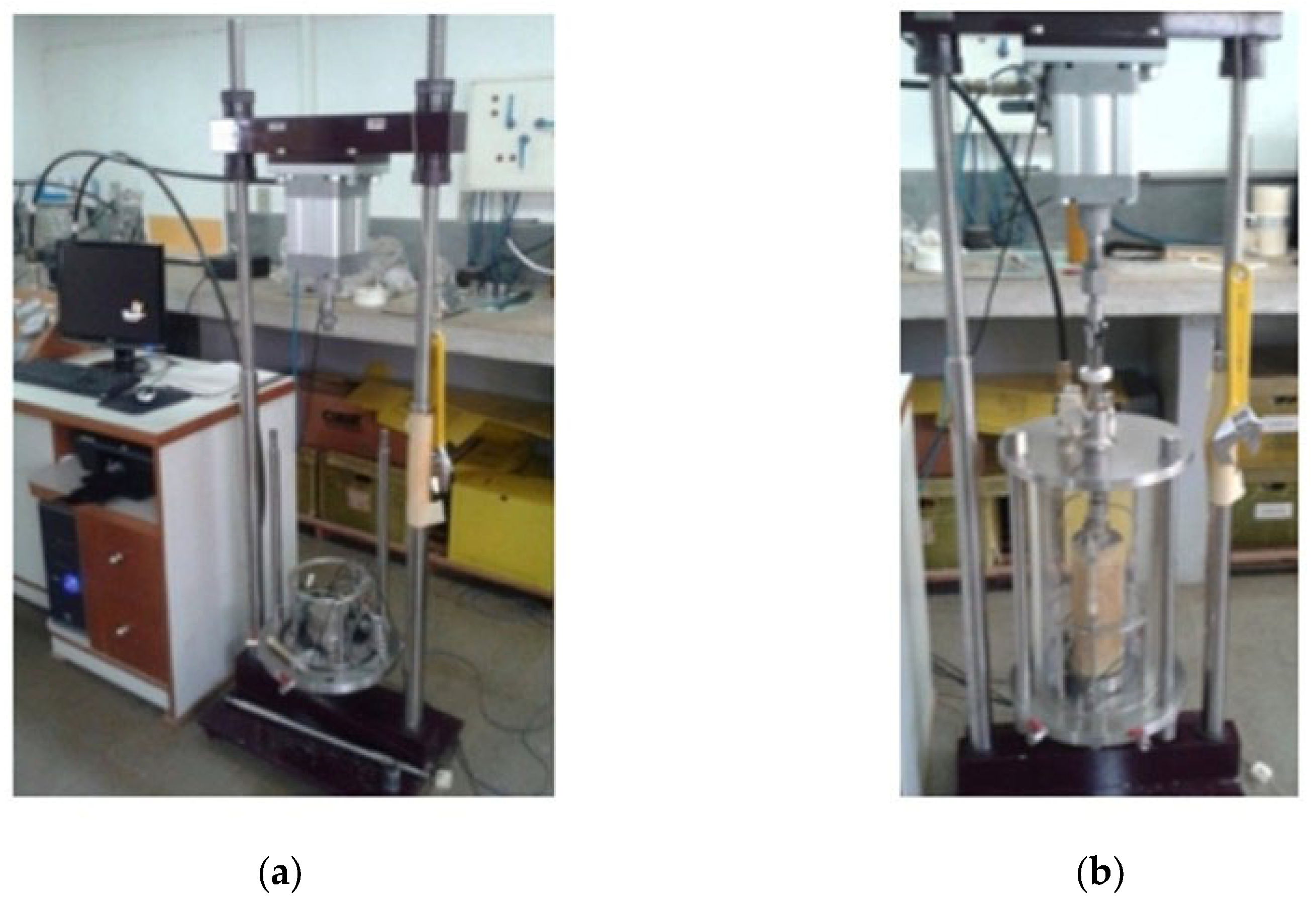

Figure 1 shows the submerged specimens to determine the expansion and CBR later.

3.2.3. Resilient Modulus (RM) Test

The resilient modulus test is the most crucial for characterizing the stiffness under cyclic loading. The tests were performed in accordance with DNIT-ME 134/2018 [

48] (similar to AASHTO T307). A total of 12 specimens (3 replicates for each of the 4 proportions for both SLT and REF, though the model doc suggests 3 per proportion, totaling 12) were prepared.

Specimen Preparation: Specimens were compacted in a split mold to 100% of their Modified Proctor maximum dry density at their respective optimum moisture content.

Testing Procedure: The test was conducted using a cyclic triaxial apparatus. Each specimen was placed in a triaxial chamber and subjected to an initial conditioning sequence of load cycles to eliminate initial plastic deformations. Following conditioning, a sequence of 15 stress combinations (confining stress - σ3 and deviator stress – σd) was applied. Each load pulse had a haversine waveform with a 0.1-second load duration and a 0.9-second rest period.

Data Acquisition and Analysis: The resulting resilient (recoverable) axial deformations were measured using Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs). The RM was calculated for each stress state as RM = σd/ ϵr, where ϵr is the resilient axial strain. The software SICTRI was used for data acquisition and initial calculation. The average RM for a specimen is often reported for a standard reference stress state, and the non-linear parameters (K1, K2 and K3) for the universal model (Equation 1) were determined for each specimen via regression analysis.

Figure 2 shows the equipment used in the RM tests.

3.3. Data Analysis

The results from the CBR and RM tests were analyzed to:

Compare the performance of SLT mixtures directly with REF mixtures for each granular content.

Analyze the trend of CBR and RM with increasing granular content for both material types.

Establish a statistical relationship between the CBR and the average RM for the investigated mixtures.

4. Results

4.1. Physical and Compaction Characteristics

The geotechnical properties and compaction characteristics of the REF and SLT mixtures are summarized in

Table 2.

Atterberg Limits: A clear trend of decreasing Liquid Limit (LL) and Plasticity Index (PI) is observed with the increasing percentage of granular material in both REF and SLT mixtures. This is expected as the non-plastic granular particles dilute the clay fraction. Notably, the SLT mixtures consistently exhibited lower LL and PI values than their REF counterparts at the same mix proportion. For instance, the PI of SLT 90/10 is 4.1%, which is significantly lower than the 12.3% of REF 90/10 and well below the maximum limit of 6% specified by DNIT [

44] for base layers, indicating a lower water susceptibility.

Compaction Characteristics: The optimum moisture content (OMC) decreased, and the maximum dry density (MDD) increased for both mixture types as the granular content rose from 60% to 90%. This is a classic behavior, as the denser, coarse particles require less water to compact and can achieve a tighter packing arrangement. The SLT mixtures showed a behavior very similar to the REF mixtures, with comparable MDD and OMC values across all proportions. This is a positive indicator, suggesting that similar field compaction equipment and procedures can be used for both materials.

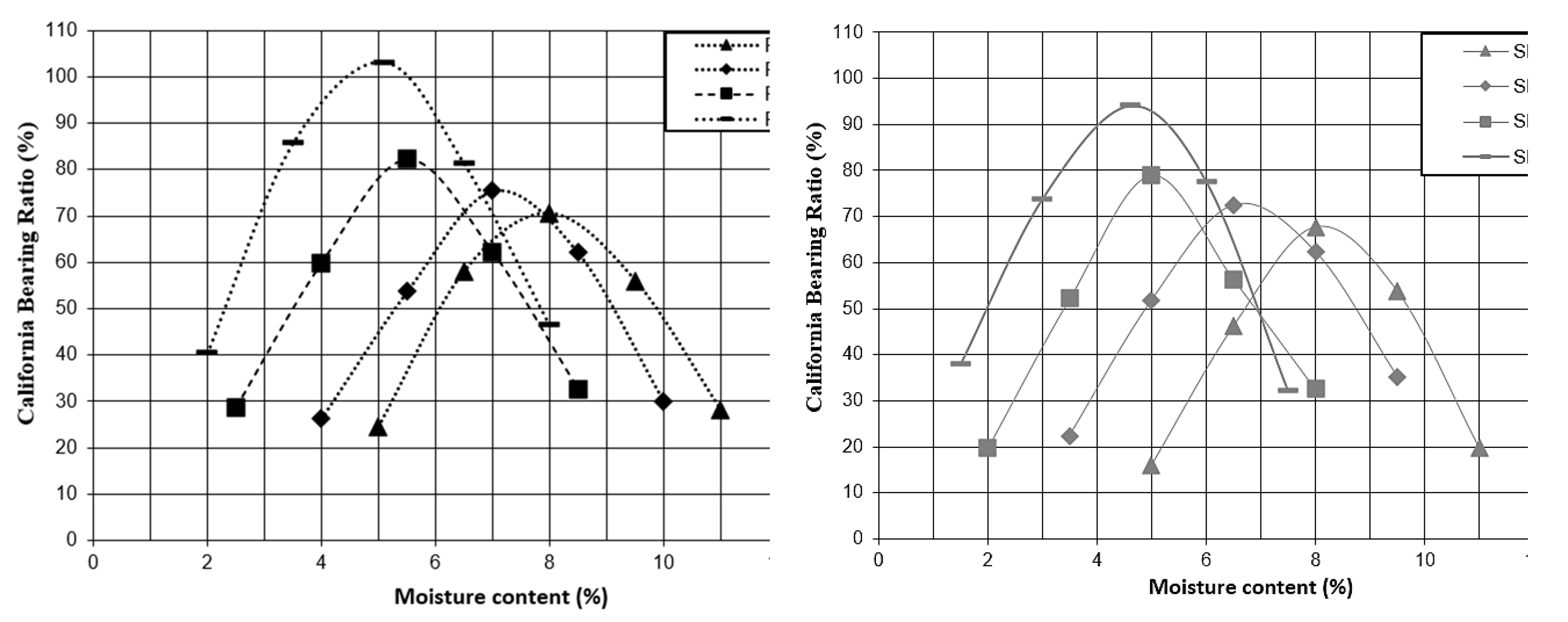

4.1. California Bearing Ratio

The CBR results, presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3, show a significant increase in strength with higher granular content for both material types.

The CBR value for the SLT mixtures rose from 67.9% (SLT 60/50) to 94.0% (SLT 90/10), representing a 38.4% increase. Similarly, the REF mixtures increased from 70.5% to 103.1%, a 46.2% increase. This demonstrates that the addition of a granular skeleton, whether gneiss or slate waste, dramatically enhances the bearing capacity of the soil.

While the REF mixtures consistently showed slightly higher CBR values than the SLT mixtures at equivalent proportions (e.g., 103.1% vs. 94.0% for the 90/10 mix), the performance of the slate waste mixtures is undoubtedly excellent. A CBR value of 94% far exceeds the typical requirements for sub-base and base layers in pavement design, indicating a very high resistance to deformation under static loading. The minor difference can be attributed to the inherent properties of the parent rocks; gneiss may produce more angular and interlocking particles compared to the slate waste.

4.3. Resilient Modulus (RM)

The resilient modulus tests provided a deeper insight into the dynamic stiffness of the materials. The results were analyzed using the universal constitutive model (Equation 1).

Table 3 presents a summary of the range of RM values for all stress states, the mean RM, and the regression coefficients (K1, K2 and K3) for a representative specimen of each mixture.

Stress Dependency: The high coefficients of determination (R

2) confirm that the universal model effectively captures the non-linear, stress-dependent behavior of both REF and SLT mixtures. The values of K1, K2 and K3 indicate how the RM changes with confining and deviatoric stress, which is crucial for accurate numerical modeling of track behavior [

1].

Stiffness Performance: The mean RM values for both mixture types show a clear and consistent increase with granular content, mirroring the CBR trend. The SLT mixtures exhibited mean RM values of 171, 183, 241, and 254 MPa for the 60/50 to 90/10 proportions, respectively. This represents a 48.5% increase in stiffness. The REF mixtures showed a similar trend, with mean RM values of 182, 186, 260, and 269 MPa, corresponding to a 47.8% increase.

The RM values for the slate waste mixtures are impressive. They fall well within the range of 100-500 MPa reported in the literature for conventional granular materials [

36,

37] and are comparable to values reported for other recycled materials like CDW [

19,

20]. For the higher granular contents (80/20 and 90/10), the RM of the SLT mixtures is very close to that of the REF mixtures, with the SLT 90/10 achieving 254 MPa versus 269 MPa for REF 90/10. This indicates that under the dynamic loading conditions representative of train traffic, a well-compacted slate waste sub-ballast would provide a level of support and stiffness very similar to that of a conventional crushed rock sub-ballast.

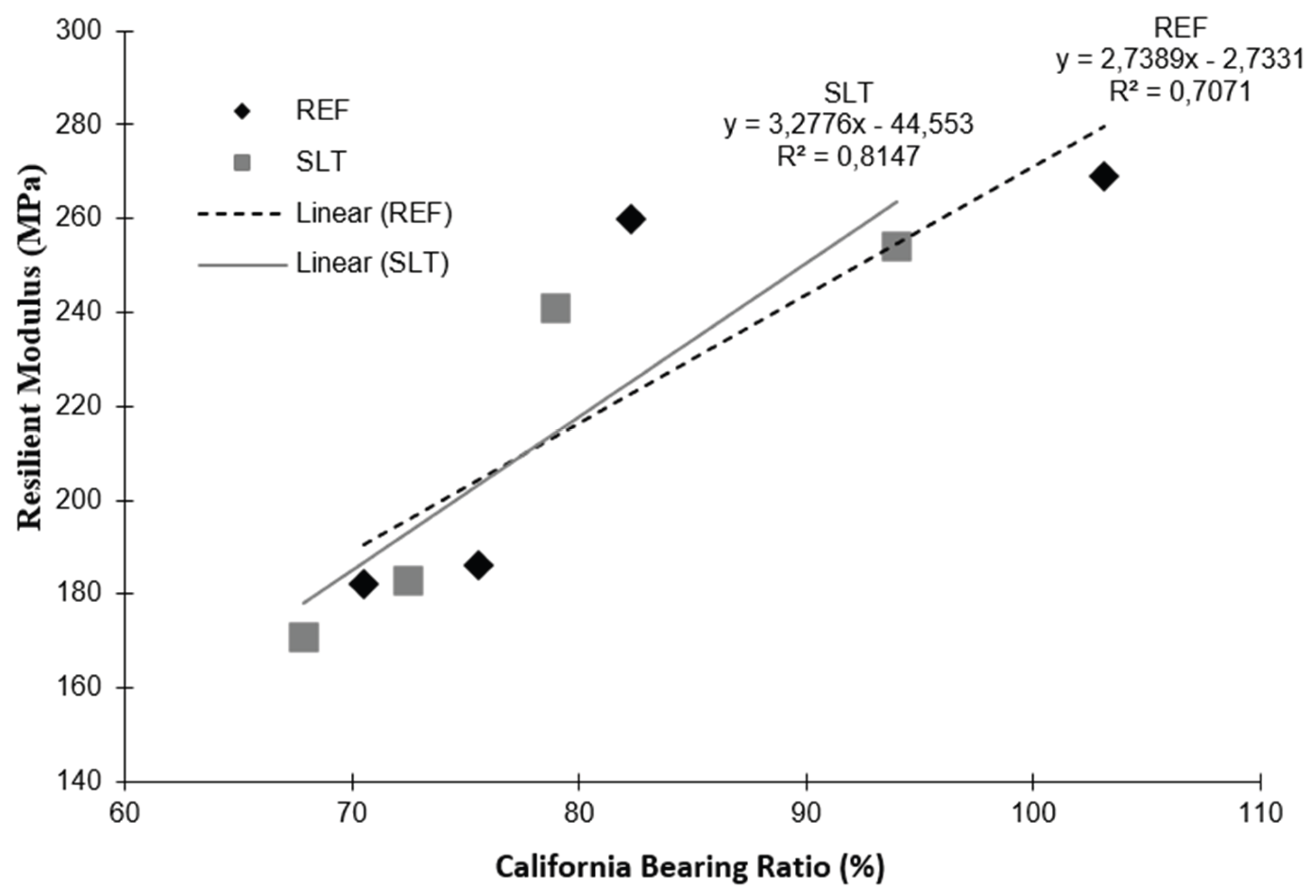

4.4. Relationship Between CBR and RM

A regression analysis was performed to establish a correlation between the average CBR and the mean RM for all mixtures. The resulting plot is shown in

Figure 4.

The analysis confirms a non-linear relationship between CBR and RM for these granular-soil mixtures. While both parameters increase with granular content, the rate of increase is not proportional. The coefficient of determination (R²) was 0.71 for the REF mixtures and 0.81 for the SLT mixtures, indicating a reasonably strong correlation for both material types. This similarity in the CBR-RM relationship further reinforces the finding that the slate waste mixtures behave in a mechanically analogous way to the conventional gneiss mixtures. However, the non-linearity also serves as a caution against using simple, universal conversion factors between these two important parameters; the relationship must be established for specific materials.

5. Discussion

The results of this study compellingly demonstrate that slate waste is a technically viable material for use in railway sub-ballast layers. The SLT mixtures performed remarkably similarly to the conventional REF mixtures across all key parameters: compaction characteristics, CBR, and most importantly, the Resilient Modulus.

5.1. Performance in the Context of Railway Requirements

The mechanical performance of the SLT mixtures, particularly at higher granular contents (80% and 90%), meets or exceeds the typical requirements for sub-ballast.

CBR: Values exceeding 80% are generally considered excellent for base courses in heavy-duty pavements. The SLT 80/20 and 90/10 mixtures, with CBR values of 79% and 94% respectively, are more than adequate for a sub-ballast layer, which is subjected to lower stresses than the ballast but higher ones than the subgrade.

Resilient Modulus: The mean RM values of 241 MPa and 254 MPa for the SLT 80/20 and 90/10 mixtures are substantial. For comparison, Castro et al. [

1] reported RM values for recycled fouled ballast stabilized with cement in the range of 200-225 MPa, which were found to be effective in reducing track displacements. The Portuguese technical specification IT.GEO.006, as cited by Paixão et al. [

13], requires a minimum deformation modulus of 120 MPa on top of the sub-ballast layer, a value that all high-content SLT mixtures easily surpass. The RM values obtained are also consistent with those reported for other successful alternative materials, such as steel slag [

32] and stabilized CDW [

19].

5.2. Sustainability and Economic Implications

The environmental argument for using slate waste is strong. By diverting this material from landfills, the project reduces its environmental footprint, conserves natural resources (gneiss aggregate), and aligns with the principles of a circular economy. The use of locally available slate waste can also lead to significant economic savings by reducing the cost of raw materials and transportation, as was the case in the Portuguese example where locally available limestone replaced imported granite [

13]. Furthermore, the ability to use a simple granulometric stabilization with local soil, rather than requiring high-cost binders in all scenarios, enhances the economic viability. However, as demonstrated by Castro et al. [

1], the addition of a small percentage (e.g., 3%) of cement can provide further performance enhancements for challenging subgrade conditions, offering a flexible design solution.

5.3. Considerations for Design and Implementation

For successful implementation, several factors must be considered:

Gradation Optimization: The mixtures in this study were designed to be well-graded. In practice, the particle size distribution of the slate waste-soil mixture must be carefully controlled to meet the required filter criteria relative to the underlying subgrade and overlying ballast, ensuring proper drainage and separation [

3,

12].

Durability and Long-Term Performance: While the initial mechanical tests are promising, the long-term durability of slate waste under cyclic loading and environmental weathering should be monitored. Accelerated weathering tests, such as those using ethylene glycol or sodium sulfate as performed on ballast rocks [

49], could be conducted in future research. The mineralogical composition of slate, often rich in quartz and stable minerals, suggests good durability.

Moisture Control: As with any unbound granular layer, the performance is sensitive to moisture. The low permeability of mixtures with higher fines content can be beneficial in acting as a capillary break to protect the subgrade, as observed in tropical soils [

2,

23]. However, during construction, strict control of moisture content near the optimum is essential to achieve the desired density and stiffness.

Comparison with Other Recycled Materials: The performance of slate waste appears to be competitive with, if not superior to, many other recycled materials proposed for railways. Its RM and CBR values are generally higher than those reported for some CDW applications and are comparable to stabilized fouled ballast.

6. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive laboratory investigation into the use of slate waste, a significant industrial by-product, as a sustainable material for railway sub-ballast layers. Based on the results and discussion, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Slate waste, when mixed with a clayey soil to form a well-graded granular material, exhibits geotechnical properties (compaction characteristics, Atterberg limits) that are very similar to those of conventional gneiss aggregate mixtures.

The mechanical strength, as measured by the California Bearing Ratio (CBR), of slate waste mixtures is excellent. The CBR increased by 38.4% (from 67.9% to 94.0%) as the slate waste content increased from 60% to 90%, a trend mirroring that of conventional mixtures.

The resilient response, characterized by the Resilient Modulus, demonstrates that slate waste mixtures provide high stiffness under dynamic loading. The mean RM increased by 48.5% (from 171 MPa to 254 MPa) with the increase in slate waste content. The RM values for the optimal mixtures (SLT 80/20 and 90/10) are well within the range for conventional granular materials and are sufficiently high for heavy-haul railway sub-ballast applications.

The relationship between CBR and RM for these materials is non-linear, but strongly correlated, and is nearly identical for both slate waste and gneiss mixtures, confirming their analogous mechanical behaviour.

The use of slate waste in sub-ballast layers presents a compelling sustainable solution that addresses waste management issues, reduces the consumption of natural aggregates, and can lead to economic benefits through the use of local materials.

In summary, slate waste is not merely an acceptable alternative but a high-performance sustainable material for railway sub-ballast. Its adoption can significantly advance the environmental and economic sustainability of railway infrastructure projects. Future research should focus on large-scale field trials, long-term performance monitoring, and a detailed life-cycle assessment to quantify the full environmental benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.S and C.R..; data collection, R.S. and G.L.; data analysis, R.S. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, R.S., C.R. and G.L.; project administration, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica de Minas Gerais (CEFET-MG) and the Departamento de Edificações e Estradas de Rodagem de Minas Gerais (DER-MG) for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Castro, G.; Saico, J.; de Moura, E.; Motta, R.; Bernucci, L.; Paixão, A.; Fortunato, E.; Oliveira, L. Evaluating Different Track Sub-Ballast Solutions Considering Traffic Loads and Sustainability. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.R.; Silva Filho, J.; Castro, C.D. Contribution to the use of alternative material in heavy haul railway sub-ballast layers. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 30, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, E.T.; Waters, J.M. Track Geotechnology and Substructure Management; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Indraratna, B.; Salim, W.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C. Advanced Rail Geotechnology—Ballasted Track; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodi, C.; Chiodi, D. Plano de ação para sustentabilidade do setor de rochas ornamentais—Ardósia em Papagaios. Belo Horizonte, 2014.

- Mansur, A.A.P.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Soares, G.L.; Mohallem, N.D.S. Study of pore size distribution of slate ceramic pieces produced by slip casting of waste powders. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.K. Propostas de aproveitamento de resíduos de ardósia da cidade de Pompéu, Minas Gerais. Rev. Intercâmbio 2015, 6, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Arulrajah, A.; Disfani, M.M.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Suksiripattanapong, C.; Prongmanee, N. Geotechnical and geoenvironmental properties of recycled construction and demolition materials in pavement subbase applications. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2013, 25, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celauro, C.; Cardella, A.; Guerrieri, M. LCA of different construction choices for a double-track railway line for sustainability evaluations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hyslip, J.; Sussmann, T.; Chrismer, S. Railway Geotechnics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Rose, J.; Lopresti, J. Test of hot-mix asphalt trackbed over soft subgrade under heavy axle loads. Technol. Dig. 2001, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- AREMA. Manual for Railway Engineering; American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association: Lanham, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paixão, A.; Fortunato, E.; Fontul, S.; Martins, F. A case study in construction optimisation for sub-ballast layer. In Proceedings of the Rail Engineering International Conference, London, UK; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Indraratna, B.; Qi, Y.; Ngo, T.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Neville, T.; Ferreira, F.; Shahkolahi, A. Use of geogrids and recycled rubber in railroad infrastructure for enhanced performance. Geosciences 2019, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Keene, A. Reconstruction of Railroad Beds with Industrial Byproducts and In Situ Reclamation Material. Student Project Report; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.; Humphrey, D.; Hyslip, J.; Moorhead, W. Use of recycled tire rubber to modify track-substructure interaction. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2374, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, S.; Santos, J.; Giunta, M.; Pistonesi, L.; Lo Presti, D. A comparative life-cycle assessment of asphalt mixtures for railway sub-ballast containing alternative materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.M.; Bridges, M.G.; Dawson, A.R. Assessment of secondary materials for pavement construction: Technical and environmental aspects. Waste Manag. 1996, 16, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.C.; Motta, R.S.; Vasconcelos, K.L.; Bernucci, L.L.B. Laboratory evaluation of recycled construction and demolition waste for pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2972–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.G. Caracterização mecanística de agregados reciclados de resíduos de construção e demolição. M.Sc. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arm, M. Mechanical properties of residues as unbound road materials. Doctoral Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Labuz, J.F.; Dai, S. Resilient modulus of base course containing recycled asphalt pavement. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, L.C.A.; Guimarães, A.C.R.; Marques, M.E.S.; Ribeiro, T.S.; do Nascimento, F.A.C. Analysis of the Influence of Moisture Variation on the Behavior of Tropical Soils of Carajás Railway. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, J. Variation of resilient modulus with soil suction for cohesive soils in south China. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 16, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzaghi, K.; Peck, R.B.; Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, K.; Ghataora, G. Design for efficient drainage of railway track foundations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Transp. 2012, 167, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stopatto, S. Railway Permanent Way: Concepts and Applications, 5th ed.; T.A. Queiroz: São Paulo, Brazil, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UIC Code 719R. Earthworks and track bed for railway lines. International Union of Railways, Paris, France, 1994.

- Schilder, R.; Piereder, F. Formation rehabilitation on Austrian Federal Railways—Five years of operating experience with the AHM 800-R. Rail Eng. Int. 2000, 4, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, F.; Schilder, R.; Zuzic, M.; Breymann, H. 13 years of experience with rail-mounted formation rehabilitation on the Austrian network. Railw. Technol. (RTR) 2008, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saborido Amate, C. New recycled aggregates with enhanced performance for railway track bed and form layers. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Railway Technology: Research, Development and Maintenance, Ajaccio, France, 8–11 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, B.; Fonseca, A.; Fortunato, E.; Paixão, A.; Alves, R. Geomechanical assessment of an inert steel slag aggregate as an alternative ballast material for heavy haul rail tracks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 279, 122438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.D.; Potter, J.F.; Mayhew, H.C.; Nunn, M.E. The Structural Design of Bituminous Roads; TRRL Laboratory Report LR1132; Transport and Road Research Laboratory: Crowthorne, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hveem, F.N. Pavement Deflections and Fatigue Failures. In Highway Research Board Bulletin; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 1955; Volume 114. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO T 307. Standard Method of Test for Determining the Resilient Modulus of Soils and Aggregate Materials. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Thorn, N.H.; Brown, S.F. The mechanical properties of unbound aggregates from various sources. In Unbound Aggregates in Roads; Jones, R.H., Dawson, A.R., Eds.; Butterworths: London, UK, 1989; pp. 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bennert, T.; Papp, W.J.; Maher, A.; Gucunski, N. Utilization of construction and demolition debris under traffic-type loading in base and subbase applications. Transp. Res. Rec. 2000, 1714, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theyse, H.L.; De Beer, M.; Rust, F.C. The Mechanical Behavior of Unbound Pavement Layers and their Influence on Pavement Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Asphalt Pavements, International Society for Asphalt Pavements, Lino Lakes, MN, USA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, A.C.R. CSA Report-First Technical Visit to EFC. Projeto IME/Vale: Studies for Revision of Design Criteria for the Permanent Way. Master's Thesis, Military Institute of Engineering, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nogami, J.S.; Villibor, D.F. Pavimentação de baixo custo com solos lateríticos; Editora Villibor: São Paulo, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Von Der Osten, F. Evaluation of Four Tropical Soils for Sub-Ballast of Railway Carajas. Master's Thesis, Military Institute of Engineering, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C136 / C136M-19. Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D6913 / D6913M-17. Standard Test Methods for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Soils Using Sieve Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- DNIT 141-ES. Pavimentação - Base estabilizada granulometricamente - Especificação de serviço. Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2010.

- ASTM D4318-17e1. Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D1557-12e1. Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Modified Effort. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- DNIT-ME 172/2016. Solos - Determinação do Índice de Suporte Califórnia utilizando amostras não trabalhadas. Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016.

- DNIT-ME 134/2018. Pavimentação - Solos - Determinação do módulo de resiliência. Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018.

- Alves, D.T.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Xavier, G.C.; Monteiro, S.N.; de Azevedo, A.R.G. Technological evaluation of stones from the eastern region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, for railway ballast. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).