1. Introduction

The growing demand for sustainable materials and the urgent need to tackle plastic waste have spurred significant research into environmentally friendly manufacturing solutions [

1,

2,

3]. Given these challenges and opportunities, additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has become a transformative technology. This allows for the production of complex components with less material waste and lower energy use [

4,

5]. However, the problem of limited filament options persists. Recent developments in polymer nanocomposites, especially those combining recycled HDPE and nanokaolin, offer promising solutions [

6,

7].

Traditional AM filaments, often made from virgin polymers or bio-based sources, face issues related to cost, mechanical performance, and environmental impact [

8,

54,

55]. Recent progress in polymer nanocomposites, especially those using recycled HDPE and nanostructured fillers, presents viable options for addressing these limitations [

9,

10,

11]. Nanokaolin, a layered silicate clay, has gained attention as a functional filler because it can improve the mechanical and thermal properties of polymer matrices while remaining low-cost and readily available [

12,

13,

14]. When combined with recycled HDPE, nanokaolin-based nanocomposites have shown considerable enhancements in tensile strength, thermal stability, and overall material performance [

8,

9,

15].

Despite these advancements, the systematic optimization of processing parameters and thorough evaluation of industrial feasibility have not been fully explored [

34,

35]. To address these gaps, this review evaluates the development of sustainable nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments for additive manufacturing [

28,

29]. We focused on performance optimization using the Taguchi method and assessed both the economic and environmental impacts. The main goals are to (i) summarize recent progress in material formulation and processing, (ii) analyze key structure–property relationships, (iii) evaluate advanced characterization and modeling approaches, and (iv) discuss the scalability and industrial relevance of these nanocomposite filaments.

With the objectives and scope outlined, the remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the fundamental structure and properties of polymer nanocomposites.

Section 3 discusses the fabrication techniques and process optimization.

Section 4 presents the characterization methods, and

Section 5 examines the industrial applications and challenges. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and presents future research directions.

Given these challenges and opportunities, it is crucial to review the current state of research on polymer nanocomposites and their roles in additive manufacturing.

2. Literature Review

The integration of nanofillers into polymer matrices has transformed the development of new materials for additive manufacturing [

1,

3,

28,

29]. Specifically, nanocomposites—defined as composites with at least one dimension in the 1–100 nm range— exhibit unique mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties compared to traditional microcomposites [

1,

16,

17]. Moreover, the high aspect ratio and large surface area of nanokaolin provide significant reinforcement, improving the tensile strength, modulus, and thermal stability of recycled HDPE matrices [

8,

9,

37,

41,

45,

49].

Advancement in Polymer

Recent studies have shown that nanokaolin-recycled HDPE nanocomposites can achieve up to a 35% increase in tensile strength and a 25% increase in thermal stability compared to virgin or biobased filaments [

8,

9,

25,

45,

52,

55]. The addition of nanokaolin lowers material costs, supporting the circular economy and sustainable manufacturing practices [

3,

7,

40]. A summary of the mechanical properties of various filament materials shows the competitive performance of recycled HDPE-based nanocomposites, as shown in Table I [

25,

26].

Using the Taguchi method for process optimization improved the uniformity and printability of nanocomposite filaments, allowing for scalable production in industrial applications [

42,

47]. Advanced characterization techniques, such as SEM, TEM, and X-ray diffraction, have provided valuable insights into the distribution and bonding of nanokaolin within the polymer matrix [

5,

12,

36]. These improvements have led to the use of nanocomposite filaments in the automotive, aerospace, and prototyping sectors, where high-performance and cost-effective materials are crucial [

15,

27,

31].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in achieving optimal dispersion, interfacial adhesion, and process scalability. Ongoing research continues to address these problems by focusing on refining material formulations, processing methods, and characterization protocols [

27,

40,

43]. The literature supports the potential of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments as a feasible option for sustainable additive manufacturing.

Nanocomposites

Nanocomposites are defined as composites in which at least one component has a dimension in the 1–100 nm range [

1]. Their unique properties arise from complex interactions in the heterogeneous phase, resulting in significant differences from traditional composites [

16,

17]. The morphology and interfacial characteristics of nanocomposite materials are critical in determining their performance, not just the properties of the parent materials [

16,

18,

24,

33,

53]. Notably, new properties can emerge that do not exist in the parent constituents [

18,

19,

20,

53].

Nature itself inspires nanocomposite design, as evident in biological materials such as bone, shells, and wood [

14,

15]. Early work by the Toyota Central Research Laboratories showed significant improvements in the thermal and mechanical properties of nylon-6 nanocomposites with minimal nanofiller loading [

15]. This effect has also been replicated in studies that used nanofillers in recycled plastic waste to create industrially relevant nanocomposite products.

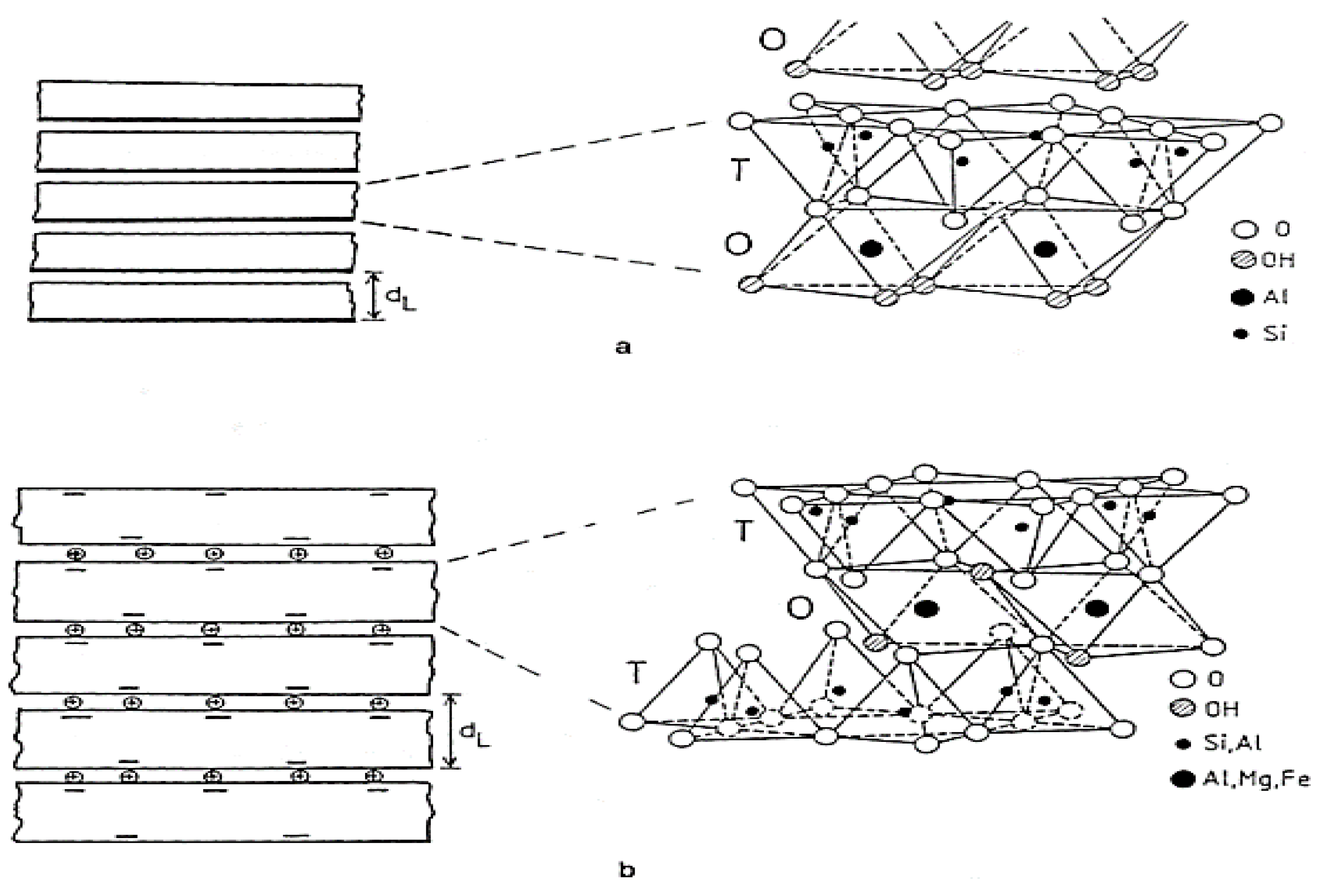

Types of Nanocomposites

Nanocomposites are categorized based on the matrix phase as polymeric, ceramic, or metallic. The structures of the 1:1 and 2:1 clay mineral layers can be seen in various diagrams shown below (

Figure 1,

Figure 2, and

Figure 3) [

17,

18,

27]. In polymer-matrix nanocomposites, the polymer is the main component, and adding nanoparticulates significantly boosts performance owing to the high aspect ratio and surface area of the filler [

20,

21]. Research has shown that well-dispersed kaolin clay nanofillers in recycled polyethylene matrices improve the mechanical properties suitable for industrial applications [

8,

9,

22,

23,

24,

34,

51].

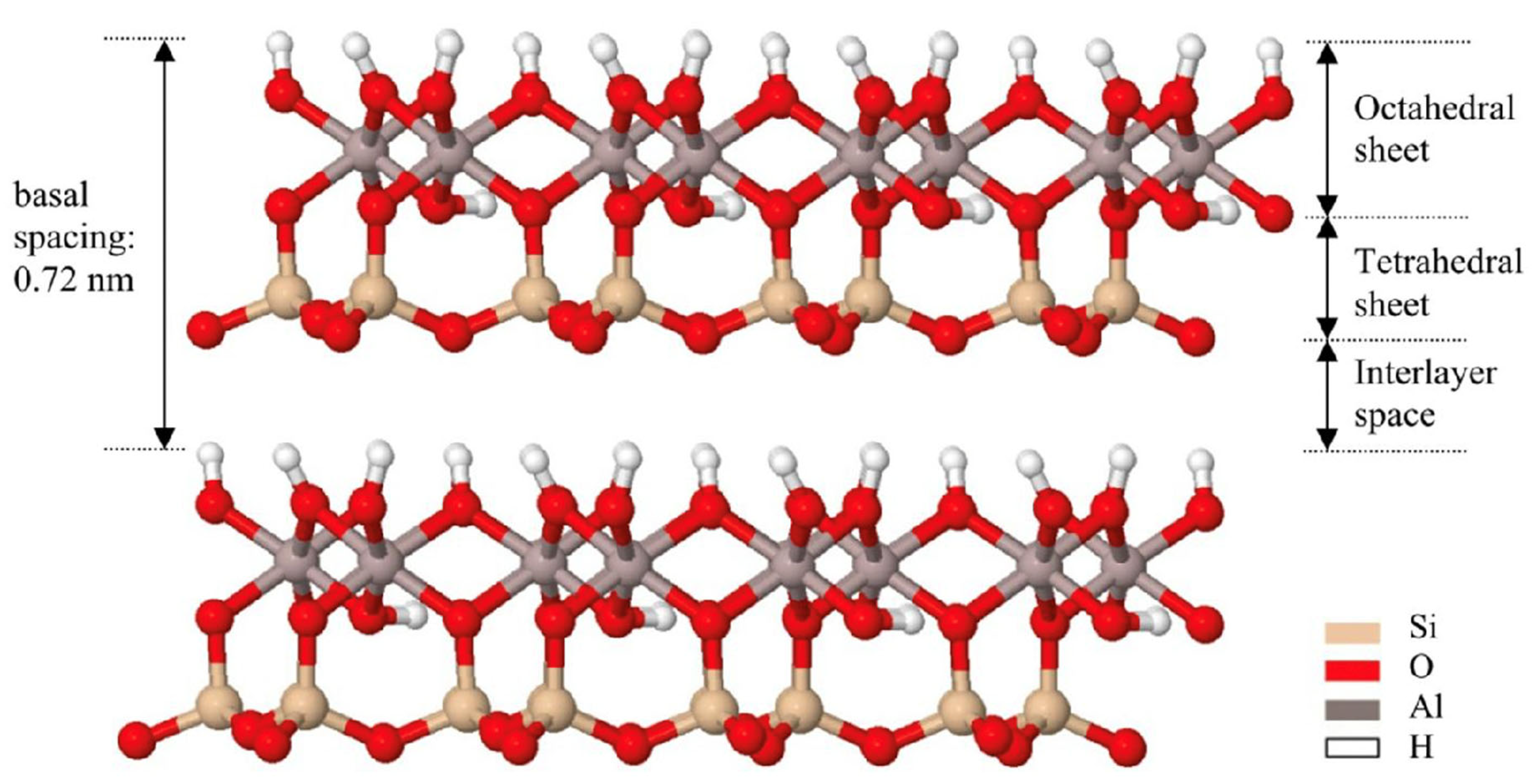

Typically, clay minerals consist of tetrahedral silicate and octahedral hydroxide sheets arranged in layers stacked upon each other, as shown in

Figure 2 above. The categorization was based on the type and number of layers, such as 1:1 or 2:1. Type 1:1 clay, such as kaolinite, includes one tetrahedral sheet and one octahedral sheet, as shown in

Figure 3 above [

27]. In contrast, most clay minerals, such as montmorillonite, vermiculite, and talc, belong to the 2:1 clay group, where the octahedral sheet is sandwiched between two tetrahedral sheets [

17].

Role of Nanokaolin in HDPE Matrices

A significant comparative study on additive manufacturing filaments found that recycled HDPE-based nanocomposites can match or exceed the mechanical properties of conventional filaments.

Table 1 below summarizes the tensile strength, elongation, and modulus of various filament materials, showing the competitiveness of the recycled HDPE and nanokaolin blends [

14,

25].

Recent research has confirmed that adding nanokaolin to recycled HDPE can enhance the impact strength and tensile properties by up to 35% [

8,

9,

30] studies have demonstrated that modified kaolin in polyethylene composites improves crystallization and mechanical performance, especially when combined with compatibilizers [

46].

Other studies have examined the use of graphene, montmorillonite, and cellulose fibers as nanofillers. These studies show that even small amounts of these additives can significantly improve the modulus, thermal stability, and interfacial adhesion [

24,

40,

46]. For instance, some studies have found that hybrid systems with nanoclay and cellulose achieve effective stiffening and strengthening with minimal filler content [

30,

32,

40,

41,

46,

47].

Table 2 below lists the key physical properties of plastics [

44].

Key Takeaways

Nanokaolin-recycled HDPE nanocomposites offer mechanical and thermal properties comparable to or better than those of virgin polymer filaments [

8,

9,

38,

39,

40,

45,

46].

A summary highlights the competitive performance of these materials in terms of tensile strength and modulus.

Key studies provide strong evidence of the industrial viability of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE blends in additive manufacturing.

While past studies have shown the benefits of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE composites, the next section outlines the experimental approach used in this review study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Breakdown of Methods Section

3.1.1. Methods Section – Simple Visual Aids

3.1.1.1. Flowchart of Optimization Process

A simple diagram shows the steps as follows:

- a)

Selection of control factors

- b)

Construction of experimental matrix

- c)

Execution of extrusion trials

- d)

Statistical analysis

- e)

Filament evaluation

3.2. Diagram of Characterization Techniques

3.2.1. A Simple Illustration Shows SEM, TEM, and WAXD as the Main Steps for Analyzing the Dispersion and Microstructure

3.3. Methods (Process Optimization)

3.3.1. Optimization Approach

3.3.1.1. The Taguchi Method Was Used Within a Design of Experiments (DOE) Framework

This statistical approach allowed systematic variation and analysis of the key process parameters.

Extrusion temperature

Pressure

Time

3.3.2. Experimental Design

3.3.2.1. Orthogonal Arrays Help Explore the Effects of Multiple Factors and Their Interactions Efficiently

3.3.2.2. The Signal-to-Noise (S/N) Ratio Was Calculated for Each Experimental Run

3.3.3. DOE Steps

Selection of control factors

Construction of the experimental matrix

Execution of extrusion trials

Statistical analysis to find the best parameter settings

3.3.4. Characterization Techniques

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Wide-Angle X-ray Diffraction (WAXD)

These techniques were used to assess the distribution of nanokaolin within the HDPE matrix and connect the microstructural features with the mechanical and thermal properties.

3.3.5. Evaluation

After outlining the methodology, the next results section presents the key findings of the optimization and characterization processes.

4. Breakdown of Results Section

4.1. Results Section – Key Findings Highlighted

Key Findings include:

Tensile strength increased by up to 35%

Thermal stability improved by about 25%

Material costs dropped by up to 40%

Better filament uniformity and printability achieved

Well-dispersed nanokaolin confirmed by SEM and TEM

Reliable performance in additive manufacturing trials

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Mechanical and Thermal Properties

The Optimized nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments showed:

Up to 35% increase in tensile strength

About 25% improvement in thermal stability

Enhanced modulus and impact resistance

4.2.2. Process Optimization Outcomes

The Taguchi method produced filaments with better uniformity and printability than the other methods.

Signal-to-noise ratio analysis revealed the best combination of extrusion temperature, pressure, and time, minimizing the defects and variability.

4.2.3. Microstructural Analysis

This correlated with improved mechanical performance.

4.2.5. Industrial Viability

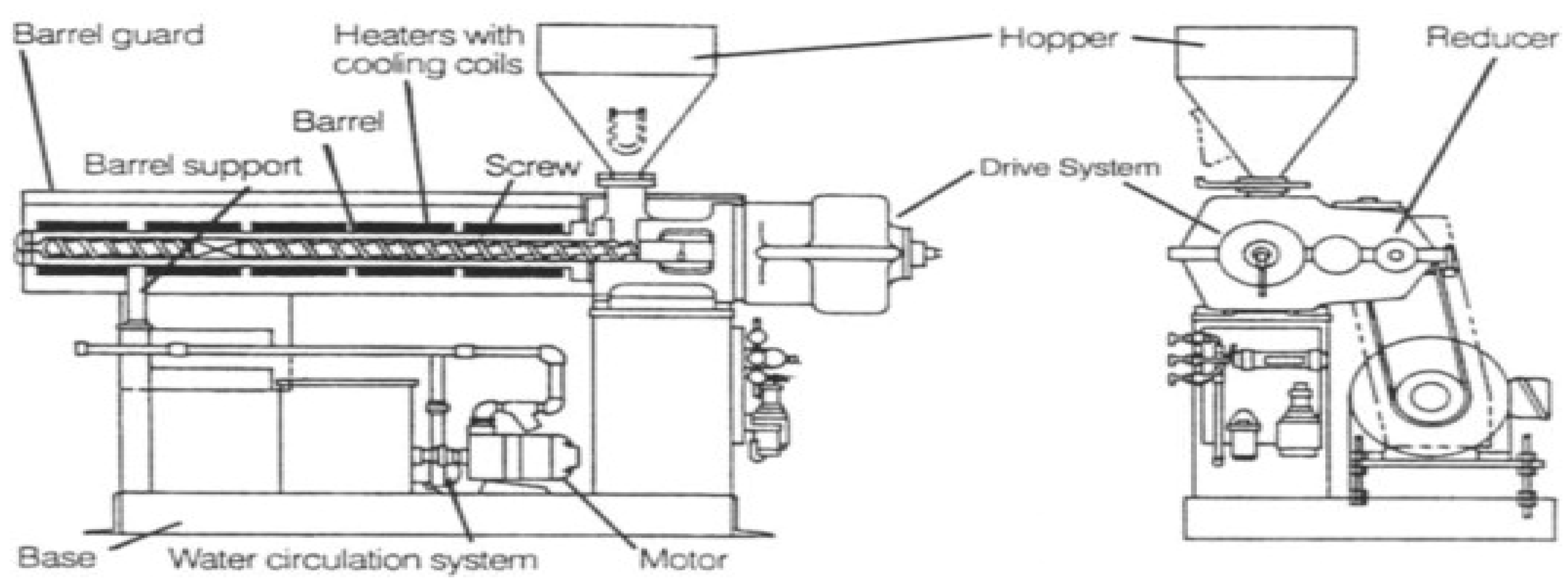

4.3. Methods and Process Optimization

The production of nanokaolin-recycled high-density polyethylene (HDPE) filament was optimized using the Taguchi method within a design of experiments (DOE) framework. This statistical method allows for systematic changes and analysis of key process parameters, such as extrusion temperature, pressure, and time [

48]. The goal was to identify the best conditions for filament consistency and mechanical performance [

42,

47].

Figure 4 shows a typical setup for a Single-Screw Extruder [

56]. This extrusion process applies to polymers that are unsuitable for adsorption or in situ polymerization [

56].

4.4. Optimization Techniques for Filament Production

Orthogonal arrays were used to examine the effects of multiple factors and their interactions efficiently. We calculated the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios for each experimental run using the “smaller-the-better” criterion to reduce defects and variability in the filament properties. The DOE process involved selecting control factors, creating an experimental matrix, conducting extrusion trials, and performing statistical analysis to determine the best parameter settings.

Advanced characterization techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD), were used to assess the dispersion of nanokaolin within the HDPE matrix [

5,

12,

36]. They also helped to link microstructural features with mechanical and thermal properties. The optimized filaments were further evaluated for printability and industrial applications.

This approach led to consistent improvements in the tensile strength, thermal stability, and cost-effectiveness. This also supports the scalability of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments for additive manufacturing applications. The results section highlights the performance metrics and industrial feasibility of optimized filaments.

4.5. Results

The optimized nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments exhibited significant enhancements in mechanical and thermal properties compared to standard virgin and biobased filaments. The tensile strength increased by up to 35%, and the thermal stability improved by approximately 25%, as confirmed by a comparative analysis with the reference materials in Table I [

25,

26]. The addition of nanokaolin as a functional filler enhanced the modulus and impact resistance, making these filaments suitable for demanding industrial applications [

8,

9,

45].

Process optimization using the Taguchi method produced filaments with better uniformity and printability. Signal-to-noise ratio analysis highlighted the best combination of extrusion temperature, pressure, and time, reducing the defects and variability in the filament dimensions. Microstructural analysis using SEM and TEM revealed evenly dispersed nanokaolin platelets within the HDPE matrix, which correlated with the observed improvements in mechanical performance [

5,

12,

36].

Economic analysis revealed a material cost reduction of up to 40% compared to virgin polymer filaments, mainly due to the use of recycled HDPE and abundant nanokaolin. The optimized filaments performed reliably during additive manufacturing trials, producing components with consistent dimensions and surface quality.

These results support the industrial viability of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments for additive manufacturing, encouraging their use in industries such as automotive, aerospace, and functional prototyping. This discussion explores the broader implications and challenges associated with these findings.

5. Discussion

The results of this study show that nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments offer considerable improvements in mechanical and thermal properties, along with significant cost reductions compared with standard virgin and biobased filaments. The increases in tensile strength and thermal stability align with previous findings on the reinforcing effects of nanokaolin and other nanofillers in polymer matrices [

50]. The successful use of the Taguchi method for process optimization underscores the value of selecting parameters systematically to achieve consistent filament quality and performance [

37,

41].

Microstructural analysis confirmed that evenly dispersed nanokaolin is critical for maximizing the mechanical enhancements. Advanced characterization techniques, such as SEM and TEM, provide valuable insights into the connection between the filler distribution and material properties. These findings highlight the potential of nanocomposite filaments to meet the stringent requirements of industrial additive manufacturing.

From an industrial standpoint, the adoption of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments offers multiple advantages. Lower material costs, combined with better mechanical and thermal performance, support their use in high-value sectors, such as automotive, aerospace, and functional prototyping. The scalability of the improved extrusion process and the reliability of the filament printability further enhance their commercial potential. By using recycled polymers and abundant nanokaolin, manufacturers can aid circular economy initiatives and reduce the environmental impact of 3D printing operations.

However, challenges persist in achieving consistent filler dispersion at larger production scales and in tailoring filament properties for specific applications. Future research should focus on improving process control, exploring alternative nanofillers, and broadening the range of industrial applications of these nanocomposites. Overall, incorporating nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments into additive manufacturing workflows is an important step toward sustainable, high-performance, and cost-effective 3D printing solutions. The conclusion summarizes the main outcomes and limitations to guide future research directions.

6. Conclusion

This review highlights the potential of nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments for sustainable additive manufacturing. They exhibit significant improvements in tensile strength, thermal stability, and cost-effectiveness. However, a few limitations and potential criticisms should be addressed to provide a balanced view and inform further research.

Potential Limitations

Although laboratory-scale optimization produces consistent results, scaling up the extrusion process for industrial production may introduce variability in the filler dispersion and filament quality. Further research is required to ensure process control at larger scales.

Using recycled HDPE creates variability in polymer properties from batch to batch, which can affect filament performance. Standardizing recycling streams and pre-processing protocols is crucial for obtaining consistent results.

The reported mechanical and thermal enhancements were obtained from general testing. Specific applications, such as aerospace and automotive, may require additional validation under real-world conditions.

Although the study highlights reduced carbon footprint and plastic waste, a life cycle assessment (LCA) was not performed. Future studies should measure the environmental benefits across the entire product life cycle.

Focusing on nanokaolin may overlook the benefits of other nanofillers such as graphene, montmorillonite, and cellulose. Comparative studies are recommended in the future.

Addressing Criticisms

All optimization steps and characterization techniques are described in detail to ensure reproducibility and transparency.

Using the Taguchi method and DOE framework strengthens the reliability of the findings, but further statistical validation, such as ANOVA or regression analysis, could support the conclusions even more.

While initial trials have shown industrial viability, long-term performance, scalability, and economic analysis require further exploration in future studies.

This review demonstrates that nanokaolin-recycled HDPE filaments are a promising solution for sustainable additive manufacturing. Through systematic process optimization and advanced characterization, these nanocomposite filaments achieved substantial improvements in tensile strength, thermal stability, and cost-effectiveness compared to standard virgin and biobased filaments. The successful application of the Taguchi method allowed for reproducible filament quality and highlighted the importance of statistical design in process development.

The industrial implications of this study are significant. The optimized filaments are well-suited for high-performance applications in the automotive, aerospace, and prototyping sectors, supporting both economic and environmental goals. Using recycled polymers and abundant nanokaolin, manufacturers can advance circular economy initiatives and reduce the environmental effects of 3D printing.

Future research should focus on ramping up production, improving process control, and considering alternative nanofillers to further enhance filament properties. Expanding industrial applications and integrating these materials into commercial additive manufacturing workflows will be key to realizing their full potential. The continued development of sustainable nanocomposite filaments will play an essential role in advancing high-performance, cost-effective, and environmentally responsible manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Mr. Markus C. Dye: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Results; Discussion; Writing – original draft; Project administration; Funding acquisition: Prof. M. I. Dagwa: Supervision; Investigation; Data curation; Validation; Writing – review & editing; Prof. I. D. Muhammad: Supervision; Software; Visualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing; Dr. F. H. Tobins: Supervision; Methodology; Experimental design; Writing – review & editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Abuja, for providing the facilities and resources necessary for this research. Special thanks are extended to the technical staff who assisted with the extrusion trials and characterization procedures. We also appreciate the constructive feedback from colleagues during the early stages of manuscript development. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding Statement

Include grant numbers and funding agencies.

References

- Thio, Y.S.; Argon, A.S.; Cohen, R.E.; et al. Toughening of isotactic polypropylene with CaCO₃ particles. Polymer 2002, 43, 3661–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V. Characterization Techniques for Polymer Nanocomposites, 1st ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelis, E.P. Polymer-layered silicate nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 1996, 8, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarverdi, K. Improving the mechanical recycling and reuse of mixed plastics and polymer composites. In Proceedings of the 20th International BPF Composites Congress, Hinckley, UK, 17 May 2010; Woodhead Publishing; pp. 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Neal, M.A. Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnavaia, T.J.; Beall, G.W. Polymer-Clay Nanocomposites; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. xi+345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevis, M.J.; Hornsby, P.R.; Lee, W.H.; et al. Recycling of polymer-matrix composites. In Concise Encyclopedia of Composite Materials; Kelly, A., Ed.; Persimmon, 2012; pp. 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebani, A.; Elhrari, W.; Klash, A.; et al. Effects of Libyan kaolin clay on the impact strength properties of HDPE/clay nanocomposites. Int. J. Compos. Mater. 2016, 6, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.N. Effect of kaolin on the mechanical properties of PP/PE composite material. Diyala J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 5, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.E.; Clewell, H.J.; Tan, Y.M.; et al. Pharmacokinetic modelling of saturable renal resorption of perfluoroalkylacids in monkeys. Toxicology 2006, 227, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenig, W.; Fiedel, H.W.; Scholl, A. Crystallization kinetics of isotactic polypropylene blended with atactic polystyrene. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1990, 168, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.H.; Kim, B.K. Effects of the viscosity ratio on polyolefin ternary blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 91, 4027–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorti, R.; Vaia, R.A. Polymer nanocomposites: synthesis, characterization, and modelling. ACS Symp. Ser. 2001, 804. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, A.L.N.; Rocha, M.C.G.; Moraes, M.A.R.; et al. Mechanical and rheological properties of composites based on polyolefin and mineral additives. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Mahanwar, P.A. Effect of flyash on the mechanical, thermal, dielectric, rheological, and morphological properties of filled nylon 6. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2004, 3, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, M.E.; Ahmed, N.M.; Ward, A.A. Characterization of kaolin-filled polymer composites. SPE Polym. Eng. Technol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi-Shahraki, K. Development of PET/Kaolin Nanocomposites with Improved Mechanical Properties. PhD thesis, Université De Montréal, Montréal, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zsirka, B.; Horvath, E.; Mako, E.; et al. Preparation and characterization of kaolinite nanostructures: reaction pathways, morphology and structural order. Clay Miner. 2015, 50, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazli, L.; Khavandi, A.; Boutorabi, M.A.; et al. Development and characterization of silicone rubber/EPDM/nanocomposites. In Proceedings of the 12th International Seminar on Polymer Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran, November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, D.M.; Guillaume, E.; Chivas-Joly, C. Properties of nanofillers in polymer. In Nanocomposites and Polymers with Analytical Methods; Cuppoletti, J., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Sun, Z.; Huang, P.; et al. Some basic aspects of polymer nanocomposites: a critical review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2019, 1, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.M. Composite Materials, Volume I: Properties, Nondestructive Testing, and Repair; Prentice Hall PTR: New Jersey, USA, 1996; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, R. Plastic Film Recycling from Waste Sources [PhD thesis]; University of Wales: Cardiff, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maneshi, A. Polyethylene Clay Nanocomposites: Modeling and Experimental Investigation of Particle Morphology; May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pakkanen, J.; Manfredi, D.; Minetola, P.; et al. Use of recycled or biodegradable filaments for sustainability of 3D printing. In Smart Innovation; Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, P.; Puttegowda, M.; Rangappa, S.M.; et al. Influence of nanofillers on biodegradable composites: a comprehensive review. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 4782–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benco, L.; Tunega, D.; Hafner, J.; et al. Upper limit of the O–H···O hydrogen bond: ab initio study of kaolinite structure. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 10812–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Hojjati, M.; Okamoto, M.; et al. Polymer-matrix nanocomposites: processing, manufacturing, and application. J. Compos. Mater. 2006, 1, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwajobi, A.O.; Kolawole, F.O. Development and evaluation of a fused filament fabrication (FFF) printer. Niger. J. Technol. 2021, 40, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, W.G. Polymer toughness and impact resistance. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2004, 39, 2445–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagavally, R.R. Composite materials—history, types, fabrication techniques, advantages and applications. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Puttegowda, M.; Rangappa, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; et al. Potential of natural/synthetic hybrid composites for aerospace applications. In Sustainable Composites for Aerospace Applications; Woodhead Publishing, 2018; pp. 315–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.A.S.; Olmos, D.; Gonzalez-Gaitano, G.; et al. Effect of kaolin nanofiller and processing conditions on PLA structure, morphology, and biofilm development. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, I.; Ishai, O. Engineering Mechanics of Composite Materials, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- George, A. Composite materials processing. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, A.B. Plastics: Materials and Processing, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 560–562, Published in: Mater. Manuf. Process. 1997, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.M. Plastic recycling. In Plastics and the Environment; Andrady, A.L., Ed.; Wiley, 2003; pp. 563–617. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, J.W.; Rudin, A. Properties and morphology of polystyrene and linear low-density polyethylene polyblend and polyalloy. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1991, 31, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-Yen, C.; Shwu-Jen, F. Mechanical properties and morphology of crosslinked PP/PE blends and PP/PE/propylene–ethylene copolymer blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1985, 30, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, J.; Dvorak, R.E.; Kosior, E. Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y. Recycled polymers: properties and applications. In Recycled Polymers: Properties and Applications, Vol. 2; Thakur, V.K., Ed.; Smithers Rapra Publishing: Shrewsbury, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781910242292. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.; Albano, C.; Ichazo, M.; et al. Effects of coupling agents on mechanical and morphological behavior of the PP/HDPE blend with two different CaCO₃. Eur. Polym. J. 2002, 38, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, M.; Stanley, L.P.; Muraleekrishnan, R.; et al. Modeling NBR-layered silicate nanocomposites: a DOE approach. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 118, 32147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, M. Development of fabrication methods of filler/polymer nanocomposites: with focus on simple melt-compounding-based approach without surface modification of nanofillers. J. Mater. 2010, 3, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastic Waste Management Institute (PWMI). An introduction to plastic recycling. PWMI: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: http://www.pwmi.or.jp (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Domka, L.; Malicka, A.; Stachowiak, N. Production and structural investigation of polyethylene composites with modified kaolin. In Proceedings of the 7th National Symposium of Synchrotron Users and 1st National Conference on Polish Synchrotron – Experimental Beamlines, Poznan, Poland, 24–26 September 2007; Synchrotron Radiat. Nat. Sci. 2007, 6, 72.

- Obada, D.O.; Dodoo-Arhin, D.; Dauda, M.; et al. Physical and mechanical properties of porous kaolin-based ceramics at different sintering temperatures. West Indian J. Eng. 2016, 39, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Athreya, S.; Venkatesh, Y.D. Application of the Taguchi method for optimization of process parameters in improving the surface roughness of lathe facing operation. Int. Ref. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 1, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sulyman, M.; Haponiuk, J.; Formela, K. Utilization of recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in engineering materials: a review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2016, 7, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjana, R.; George, K.E. Reinforcing effect of nano kaolin clay on PP/HDPE blends. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2012, 2, 868–872. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.M.M.; Mead, J. Thermoplastics. In Modern Plastics Handbook; Harper, C.A., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bagrodia, S.; Bash, T.; Kelly, W.; et al. Advanced materials from novel bio-based resins. In ANTEC; Cereplast Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Unal, H. Morphology and mechanical properties of composites based on polyamide 6 and mineral additives. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Plastics Council. Understanding plastic film: its uses, benefits and waste management options. American Plastics Council: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. Available online: https://p2infohouse.org/ref/47/46126.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; et al. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosato, D.V.; Rosato, M.V. Plastic Products Material and Process Selection Handbook; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 227–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).