1. Introduction

Textiles can turn into a host for microorganisms posing a threat to the safety and health of wearers while diminishing the useability of the textile. Antimicrobial function in textiles prevents bacterial transfer from the environment to the wearer and vice versa, thus assisting in health and hygiene of the surrounding [

1,

2]. Therefore, it is important to include antimicrobial function in textiles, especially in the case of protective and medical textiles. Nanofibers are fibers with diameters less than 1000nm. Along with other functional applications, nanofibers are now largely being explored for antimicrobial textile application due to their high loading capacity towards antimicrobial ingredients, large surface area, spinnability for a wide range of polymers, and easy manipulation of structural features [

3].

A variety of active antimicrobial ingredients can be utilized for the generation of antimicrobial nanofibers. The selection of the ingredient should be such that there is no toxicity and health hazard to the wearer [

2]. Metal and metal oxides have efficient antimicrobial properties and are largely used to impart antimicrobial functions to nanofibers. However higher concentrations of these active ingredients might be associated with health hazards [

4]. Further, commonly used synthetic antimicrobial agents such as triclosan and Quaternary Ammonium Salts (QAS) have also been associated with toxicity towards wearer and environment. This highlights the need for natural and non-toxic antimicrobial agents [

5].

Several research advancements are currently focused on utilizing naturally occurring antimicrobial ingredients in textiles. Some examples of natural agents being explored for antimicrobial property in nanofibers are natamycin, green tea, and rosemary extract [

6]; aloe vera gel [

7]; and photocatalytic vitamin K [

8]. Furthermore, biopolymers such as pectin (citrus peels), alginate, and chitosan are also being researched for nontoxic antimicrobial properties [

9]. One such biopolymer with inherent antimicrobial properties is ε-poly-L-lysine (PL). This cationic biopolymer is produced by Streptomyces albulus bacterium in sources like sugar and glycerol [

10,

11]. PL showcases efficient antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria via electrostatic absorption, is biocompatible, and is found to selectively target bacterial over mammalian cells [

10,

12,

13,

14]. PL has been successfully loaded into various nanofiber systems such as that of chitosan [

15,

16], gelatin [

14], polyhydroxybutyrate [

17], persian gum-polyethylene oxide [

18], cellulose [

19], and polyamide-6 [

20] for antimicrobial function in applications such as food packaging, wound dressing, and medical textiles.

Along with the nontoxic nature of the antimicrobial agent, it is also essential that the antimicrobial function is preserved throughout the use cycle of textiles. Reusability and stability of antimicrobial function in a textile is a key characteristic to allow for its large-scale adoption as well as to contain the growing medical textile waste. Despite being a vital characteristic, only a few studies address the durability of antimicrobial agents in nanofibers [

3,

21,

22].

Durable antimicrobial function in textiles is possible through sustained release of antimicrobial agents for its long-term stability and by protecting the antimicrobial agent from diminishing efficiency during use. Coaxial electrospinning can be used to achieve durable antimicrobial function. Electrospinning is a popular method of developing nanofibers by electrifying a viscoelastic solution to generate a charged jet which upon stretching and elongation results in nanofiber [

23]. Traditional electrospinning setup involves the use of a single nozzle spinneret, resulting in a monolithic nanofiber structure. Coaxial electrospinning on the other hand involves the use of a specialized spinneret with two nozzles for supplying two different spinning solutions as a single jet [

24,

25]. A core-shell fiber structure via coaxial electrospinning can allow the encapsulation of antimicrobial agents within the core protected by a polymeric shell, thus improving the lifespan of antimicrobial agents as compared to the monolithic nanofiber counterparts [

26,

27,

28].

Polyamide-6 (PA) is a vastly utilized textile polymer in medical and protective textiles due to its high mechanical performance in wet and dry conditions, biocompatibility, chemical resistance, and resistance to bodily fluids [

29,

30]. Herein, this study explores the development of nanofibers containing natural and non-toxic antimicrobial PL core surrounded by structurally similar PA shell. This novel combination of core-shell structure is expected to possess efficient antimicrobial performance that allows reusability and stability of the antimicrobial function.

2. Methods

2.1 Materials –

ε-Poly-L-lysine (PL) polymer (Mw = ~ 3500-4700 Da) was purchased from Zhengzhou Bainafo Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Henan, China). Polyamide-6 (PA) polymer (Mw = ~10,000 Da) and formic acid (88%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Nutrient Agar and Escherichia coli (K–12) bacterial culture was purchased from Carolina Biological Supply Company (Burlington, NC, USA).

2.2 Electrospinning Solution –

A monolithic fiber composition is used as the control sample for this study, in order to establish a comparison between monolithic vs core-shell nanostructure of PA and PL polymers. The spinning solution for the control sample was prepared by dissolving PA (30% w/v of formic acid) and PL (40% w/w of PA) polymers in formic acid [

20]. The core-shell nanofiber (hereon referred as CS) was spun using two spinning solutions that were prepared separately. The spinning solution for the core consisted of PL (30% w/v of formic acid) in formic acid while the spinning solution for the shell consisted of PA (30% w/v of formic acid) in formic acid. All the spinning solutions were stirred overnight to ensure homogeneity.

2.3 Electrospinning –

Nanofiber membranes were developed using electrospinning technique. The spinning solution/s were supplied to the spinneret needle at a constant rate using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The tip of the needle was connected to a fixed voltage supply using a DC power supply instrument (Gamma High Voltage Research, Ormond Beach, FL, USA). The nanofibers were collected at a fixed distance from the needle on a grounded collector.

The control sample was developed using a needle with a single nozzle (18 gauge). As for the CS sample, a custom needle (Rame-hart instrument co, NJ, USA) having a core (22 gauge) and a shell (18 gauge) nozzle was used. The spinning parameters were 1mL/hour feed rate, 20 KV voltage supply, 12 cm spinning distance, and 4 hours of collection time. Nanomembranes of different spinning compositions were developed in a randomized sequence to average out the effect of possible extraneous variables.

2.4 Thermal Bonding of Core Shell Nanofibers –

Thermal bonding is a form of physical crosslinking that can be used to bond and stabilize fibers within non-woven nanomembrane. Thermal bonding in nanofiber membranes can be utilized for improved mechanical performance and reduced water solubility [

31,

32,

33]. PL is water-soluble and thus to allow reusable and stable antimicrobial function, the CS nanomembranes were cross-linked at 80℃ for 6 hours under vacuum. The crosslinked CS nanomembranes are hereon referred to as CL-CS.

2.5 Morphological Analysis –

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, Philips, Morgagni 268, USA) with the accelerating voltage of 20 KV was utilized to confirm the formation of core-shell nanofiber structure. The TEM test samples were prepared by directly spinning CS nanofibers onto copper grids for a few seconds. Further the diameter and surface features of control, CS, and CL-CS nanofibers were analyzed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) (FEI Quanta 250, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). FESEM test samples were kept in vacuum overnight prior to imaging. The nanofiber diameters from the FESEM images were measured using Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and are reported as an average for 50 representative fibers.

2.6 Chemical Characterization –

The functional groups and chemical interaction within the nanomembranes were observed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Frontier FTIR, USA). For all the test samples a FTIR spectra was obtained in the range of 800–4000 cm−1 with 4 cm−1 wavenumber resolution, and each measurement consisted of 32 scans.

Further, X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted on all the samples with a Kratos Amicus XPS system (Kratos Analytical Ltd, Manchester, United Kingdom) to characterize the surface chemical compositions of the nanomembranes.

2.7 Thermal Analysis –

Thermal analysis was conducted using a differential scanning calorimeter (PerkinElmer DSC 4000, Shelton, CT, USA) and thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA 5500, TA Instruments, USA). During DSC analysis each sample was heated to 400 ◦C at a heating rate of 20 ◦C min-1. As for TGA analysis, the nanofiber films were heated from 25 °C to 400 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1. The whole process was performed under nitrogen atmosphere (40 mL min-1flow rate).

2.8 Water Contact Angle –

Hydrophilicity of the nanomembranes was evaluated by measuring static water contact angle using a video-based drop shape analyzer (OCA 25, Data Physics GmbH, Regensburg, Germany) and built-in SCA20 software (V.4.5.20). The analysis was conducted as per ASTM-D7334-08 sessile drop method [

34]. Testing was conducted in triplicate on separate nanomembranes for all the test samples.

2.9 Antimicrobial Analysis –

The antimicrobial property for all the samples was evaluated as per AATCC-147 zone inhibition method in triplicate on separate nanomembranes [

35]. Nutrient agar plates were prepared and seeded with 1mL Escherichia coli inoculums containing approximately 4x106 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL. Test samples were then plated in contact with the bacteria for 24 hours at 37℃. The test samples were observed for zones of inhibition post incubation.

2.10 Antimicrobial Performance Upon Long-term Exposure to Bacteria –

The testing was conducted as per AATCC-147 as described above, in triplicate on separate nanomembranes [

35]. In this case, the test samples were incubated with the bacteria for a period of 21 days and the zone of inhibition was observed.

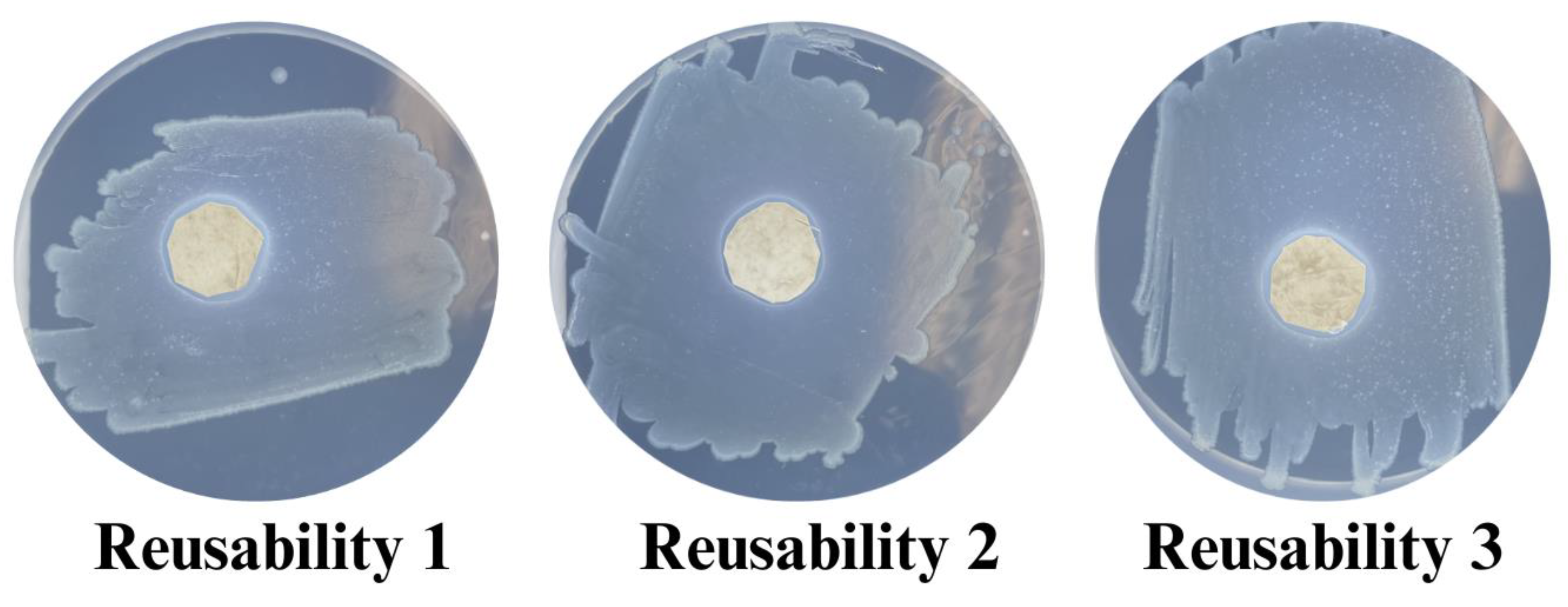

2.11 Reusability of Antimicrobial Function –

The antimicrobial function of developed nanomembranes was tested for reusability. Antimicrobial testing was conducted as per AATCC-147 and at the end of each antimicrobial test, the test sample was washed with 95% ethanol for ∼30 s and with deionized water for ∼30 s and then dried in a 60 °C oven [

35,

36]. Three cycles of reusability were performed, and three separate nanomembranes were included from each sample type for each of the test cycles.

2.12 Statistical Analysis –

The results in this study were analyzed with SPSS software (version 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey statistical tests. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Different letters in the superscripts in the tabular data indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Morphological Analysis of Nanofibers –

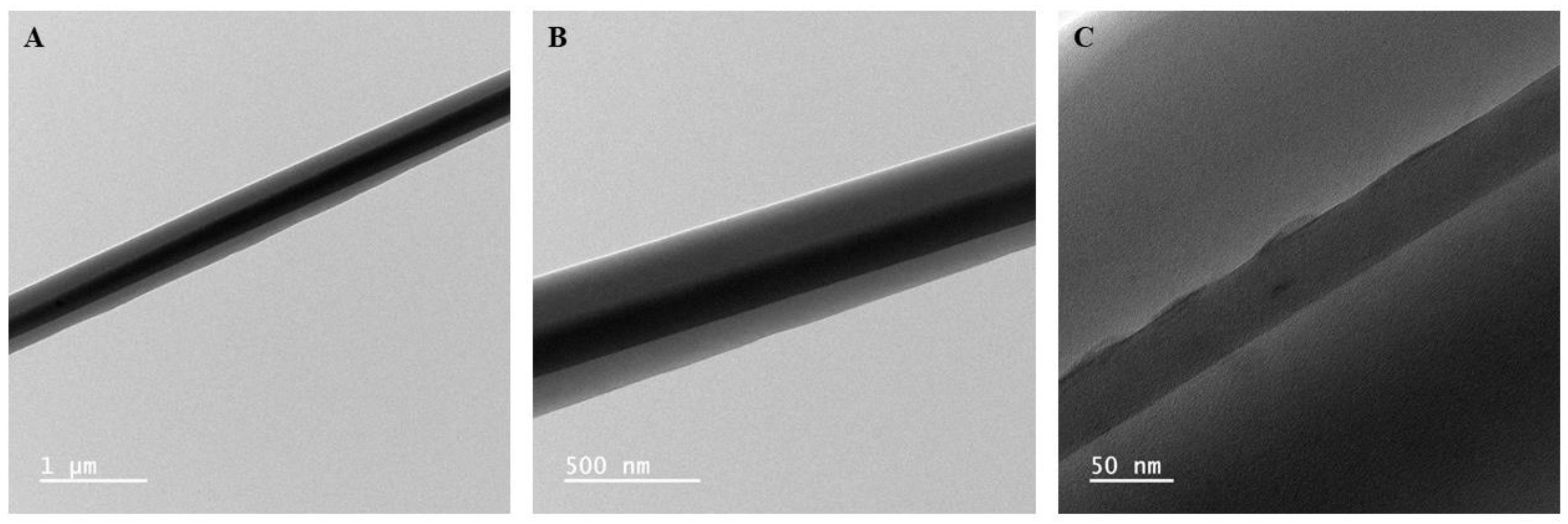

TEM imaging of CS samples was conducted to confirm the formation of core and shell structure within the nanofibers. As seen in

Figure 1, the distinct contrast in the brightness between the core and shell phases of the nanofiber allows us to confirm the presence of the two phases. Therefore, based on the TEM images, the spinning solution composition and spinning parameters used successfully translated into a core-shell nanofiber morphology.

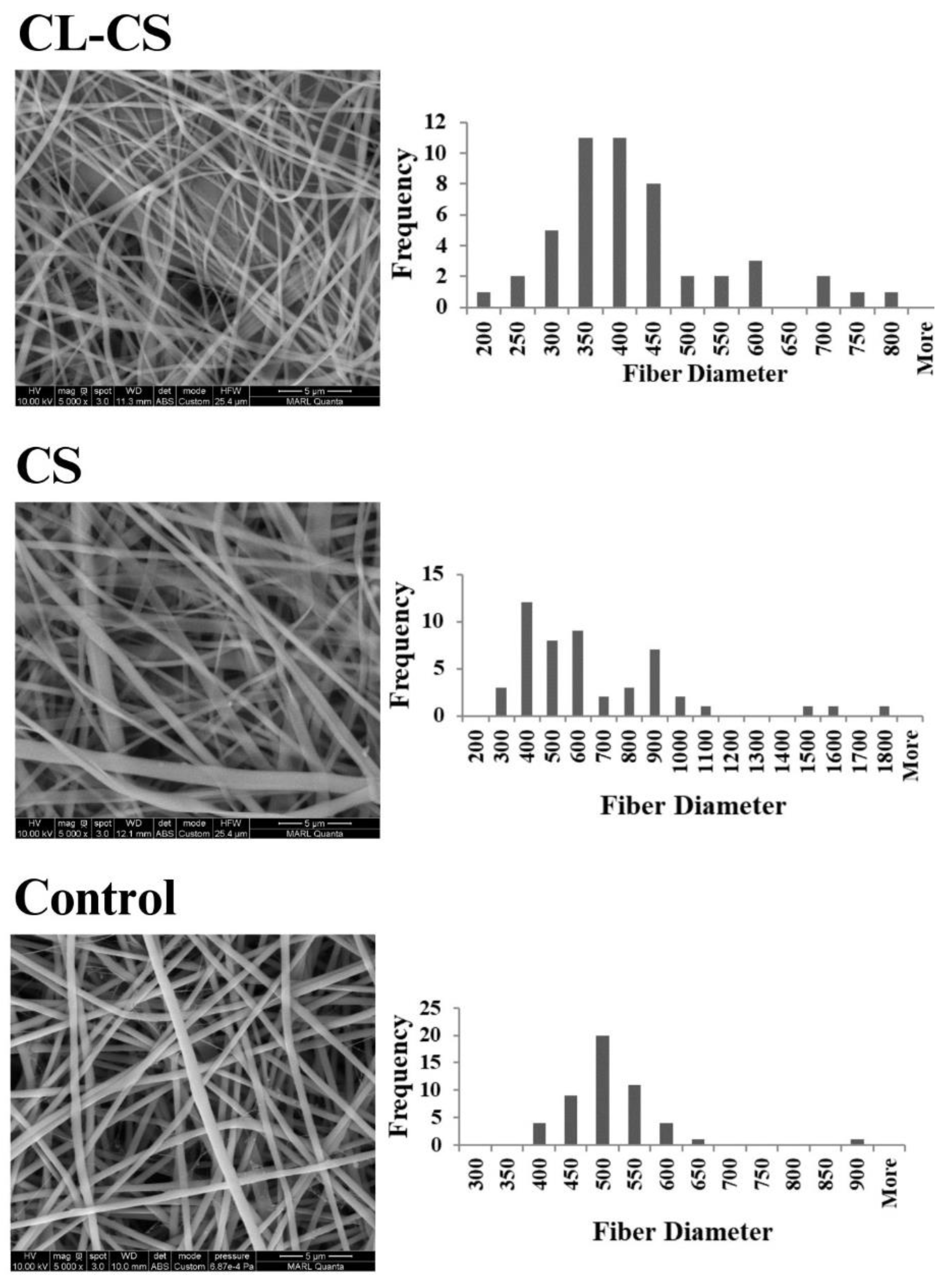

FESEM imaging was further conducted for all the samples to observe the surface features and to measure fiber diameters.

Figure 2 shows the FESEM images along with fiber diameter frequency distribution graphs for each sample. The average diameters of the nanofibers are listed in

Table 1. The FESEM images indicate the formation of continuous nanofibers for all the three samples, thus validating the spinning parameters. Nanoribbon structure is visible for some of the nanofibers in CS and CL-CS samples. Nanoribbon structure can be formed when there is a hindrance in solvent dissipation from core of spun jet due to the solidification of outer layer while the interior is still filled with undissipated solvent. Such solvent-rich jet collapses as a flat nanofiber upon reaching the collector. This phenomenon is common with thick viscous jets [

37,

38]. In this case, it can be assumed that upon dissipation of solvent molecules from the surface, the viscous spinning solution of comparatively high molecular weight PA shell hindered further dissipation of the solvent rich core made of lower molecular weight PL, thus forming the flat nanofibers. Further, the CL-CS image demonstrates bundles of bonded fibers, thus confirming that the exposure of nonwoven fiber web to temperature higher than the carrier polymer’s glass-transition temperature facilitates inter-fiber cohesion [

31].

3.2 Chemical Characterization of Nanomembranes –

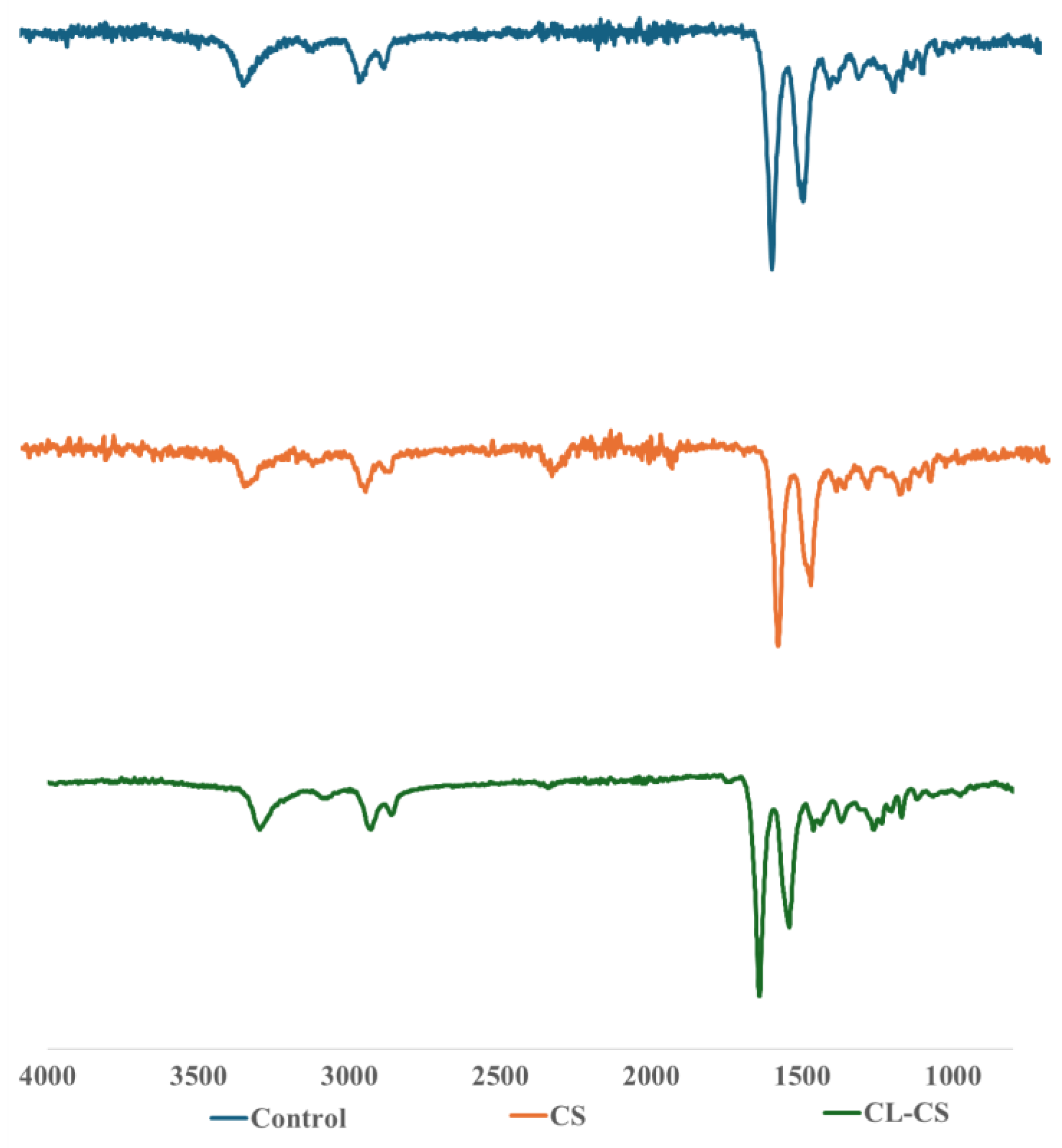

The elemental composition of all the nanomembranes was analyzed using FTIR analysis (see

Figure 3). The analysis demonstrated the characteristic peaks of both PA and PL polymers in all the samples, thus confirming their presence. The peaks characteristic to PL are ~1642 cm

-1 and ~1542 cm

-1 indicating C=O and N-H bending (amide II) stretching vibration, respectively [

16,

39,

40]. Peaks at ~3300 cm

-1 signify hydrogen-bonded N-H group. And those at ~2850 cm

-1 and ~2930 cm

-1 signify C-H_2 stretching. These peaks are characteristic of PA [

41]. A red shift is predicted for amide A in case of a replacement of the H-bonds with water to H-bonds with amide [

42]. A slight shift was observed from 3307 cm

-1 for CS sample to 3295 cm

-1 for CL-CS sample. This red shift thus could be due to the possible replacement of amide-water hydrogen bonds with amide-amide hydrogen bonds during the dehydrothermal crosslinking [

43].

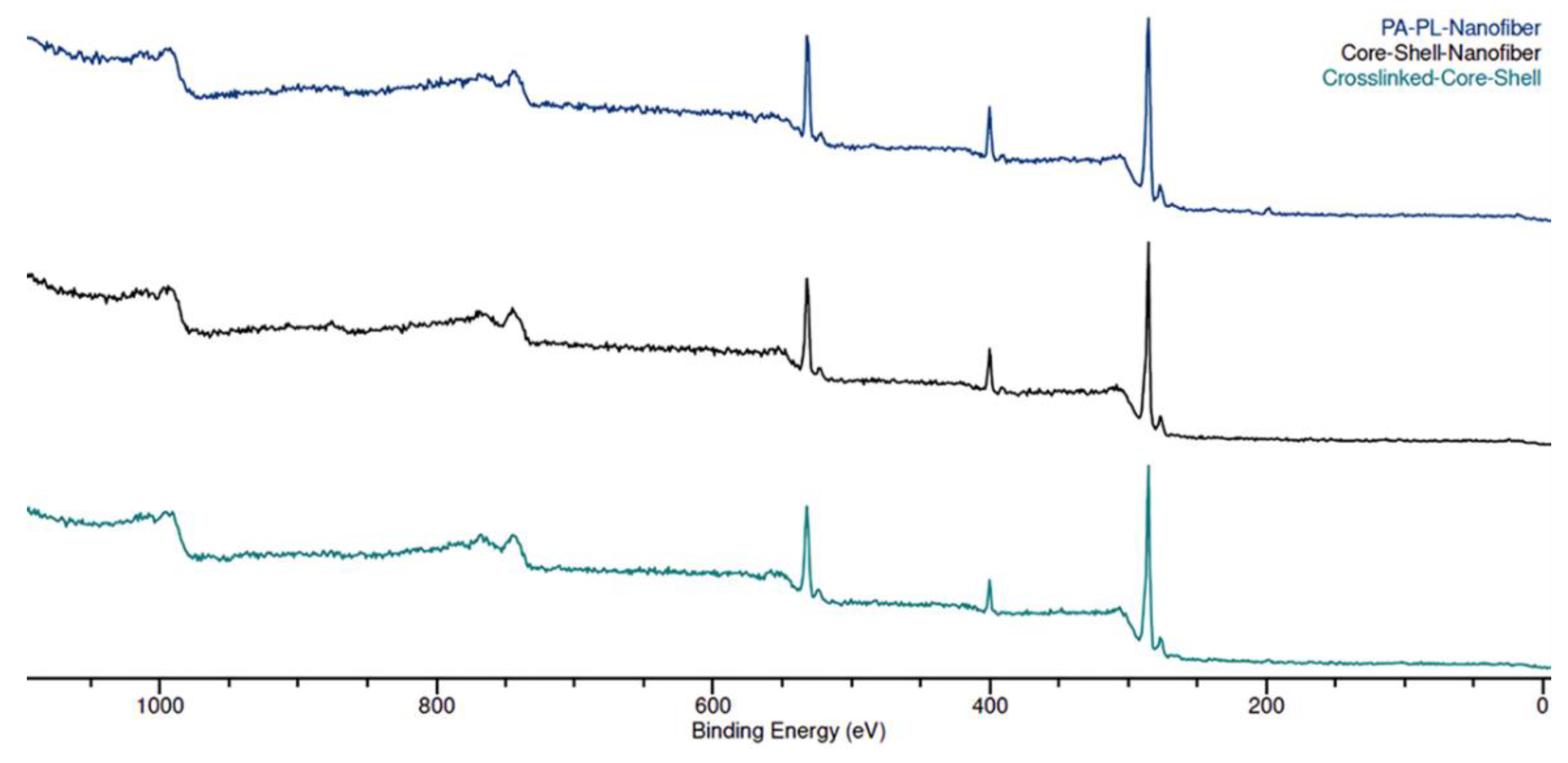

The XPS wide scan spectrum for all the nanomembranes showed the presence of carbon (C) and oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) (see

Figure 4). PL has a higher N/O ratio in its chemical structure as compared to PA, which can be used to track the presence of PL on fiber surface [

44]. The control sample exhibited a higher N/O ratio as compared to the CS and CL-CS samples (see

Table 2). This is because the control sample is a mix of PA and PL in a monolithic fiber system, expected to have the presence of both polymers on the surface. However, with the core-shell structure trapping PL within core, only nitrogen group from PA is expected on the surface. Therefore, the N/O ratio from XPS analysis further validates the different fiber structures of the samples.

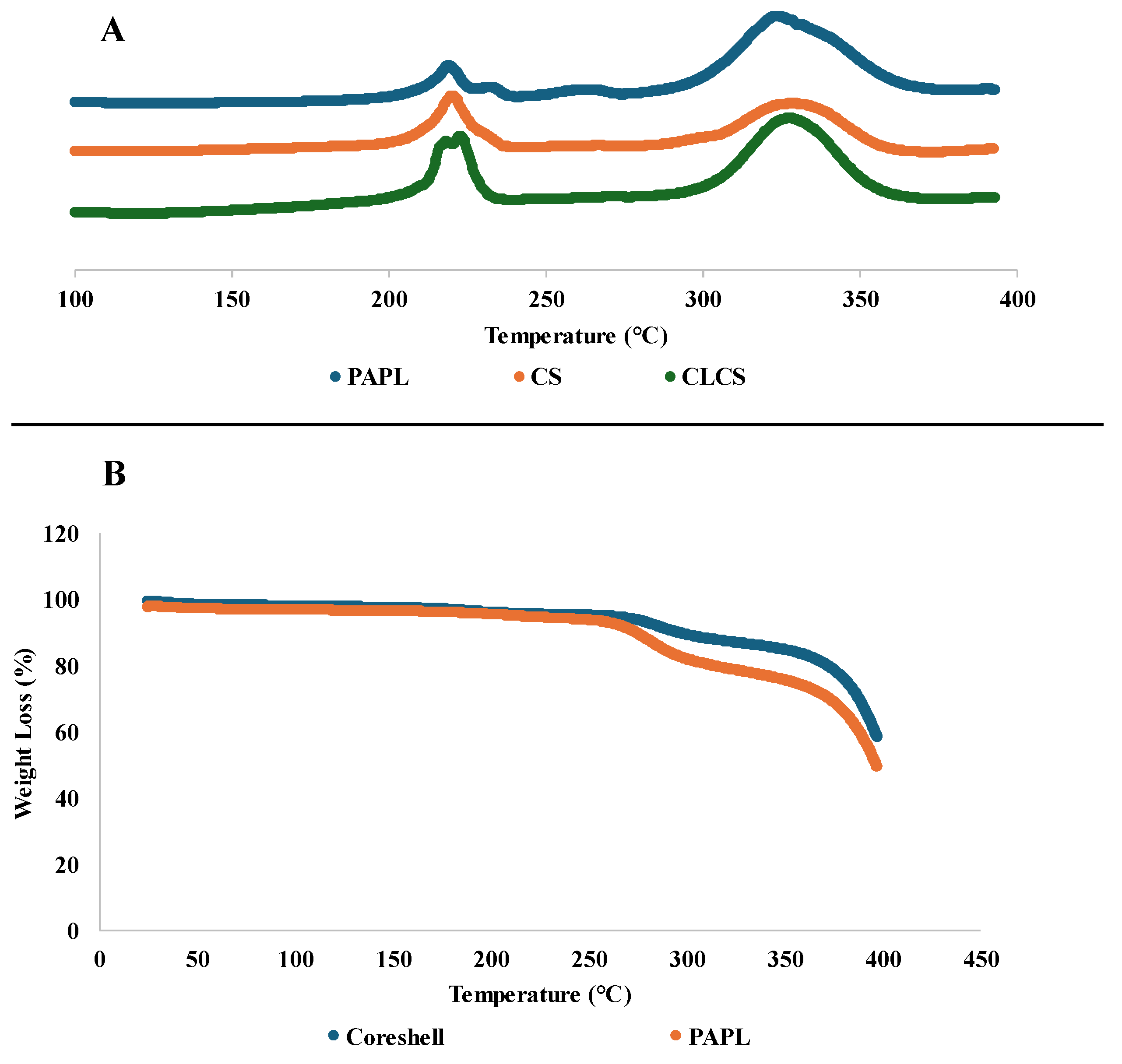

3.3 Thermal Analysis –

The DSC analysis of nanomembranes demonstrated endothermic peaks representing the melting behavior of the samples (see

Figure 5a). The onset of melting for control was at 208.30℃ and a second endothermic peak was observed at 291.16 ℃ [

20]. For CS, and CL-CS samples, melting onset was at 210.89 ℃, and 210.27 ℃, and a second endothermic peak was observed at 312.13 ℃ and 309.04 ℃, respectively. Multiple melting peaks can be an indication of secondary crystallization (melting–recrystallization–remelting) [

45,

46]. However, the absence of crystallization exotherm between the two melting peaks could be an indication of two separate phases generated during electrospinning [

47]. The melting point of PA nanomembrane is 207.05 ◦C [

20], while the melting peaks of PL powder are at 306 ◦C and 321 ◦C [

48]. Therefore, the two endothermic peaks in the samples analyzed can be said to belong to the two polymers. The phase separation in the control can be accounted for by the increased PL concentration in the fiber system [

20], possibly resulting in distinct phases. However, there is also an indication of possible interaction between the two polymers in the control sample since the melting onset, particularly for PL, is different from that of individual polymers. And as for the core shell nanofibers, the presence of two melting peaks indicates the presence of two different phases of core and shell structure [

49].

TGA analysis of the control and CS nanomembranes is shown in

Figure 5b. For both the samples a small weight loss of around 5% was observed till ~250℃, around 20 % weight loss till ~340℃, and a more dramatic weight loss thereafter. Both the samples retained around 50% of its weight at 400℃.

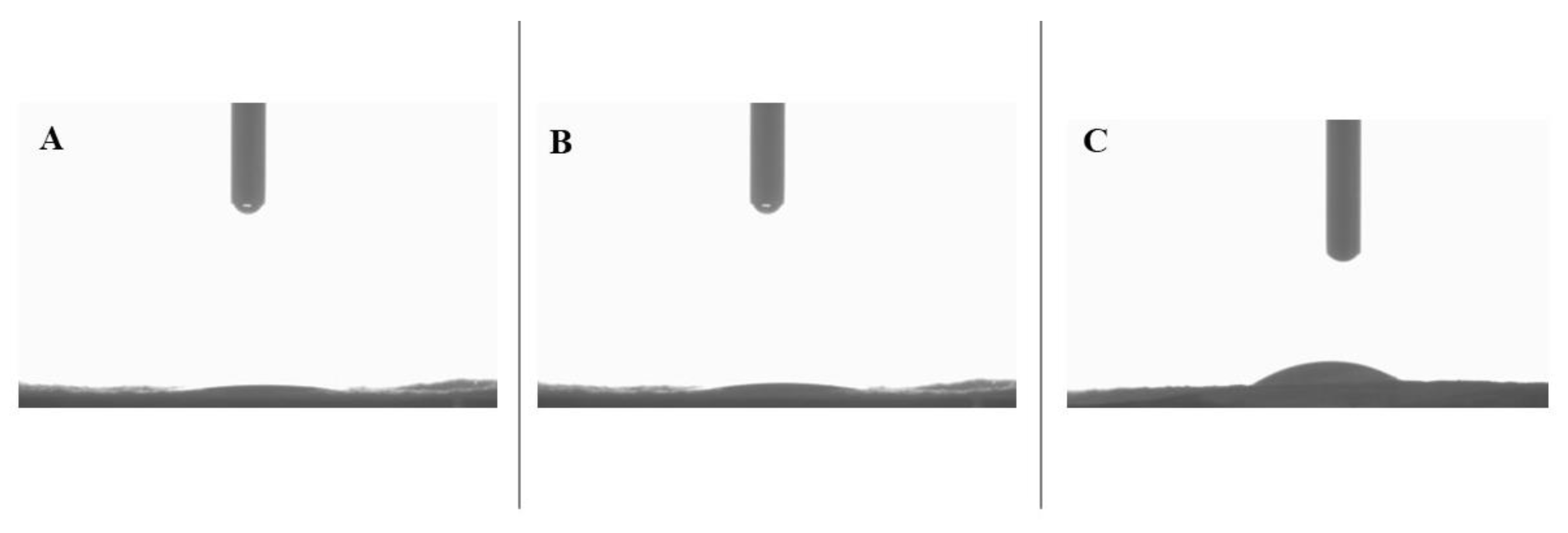

3.4 Static Water Contact Angle –

The hydrophilicity of all the samples was analyzed by measuring static water contact angles, as shown in

Figure 6. For both control and CS nanomembranes, the water contact angle between the droplet and nanomembrane became zero within the first 10 seconds of contact. This indicates highly hydrophilic behavior of the measured nanomembranes. PA nanomembrane is slightly hydrophilic with a water contact angle of 82.44 ± 9.72° at the 10 second mark [

20]. The control sample in this study is a monolithic nanofiber with a mix of PA and PL polymers. Therefore, the inclusion of PL with PA results in improved hydrophilicity due to the amino groups in PL structure that has affinity towards water molecules [

14,

20,

29]. As for CS nanomembrane, the highly hydrophilic PL core is responsible for the superhydrophilicity, either because PL readily absorbs water droplets that channel through PA or because of the presence of a few PL molecules close to/on the surface [

50,

51,

52]. Lastly, CL-CS nanomembrane exhibited a decrement in hydrophilicity with a static contact angle of 23.13 ± 1.91° at the 10 second mark. Thermal cross-linking is expected to introduce additional intermolecular crosslinks by replacing moisture via condensation due to the high temperature [

33]. Thus, the slightly reduced hydrophilic behavior in the CL-CS nanomembranes could possibly be an indication of successful crosslinking and reduced water solubility of PL.

Overall, all the nanomembranes are hydrophilic and the hydrophilicity is expected to facilitate the contact-induced antimicrobial action of PL. The cationic amino group in PL attacks bacterial anionic cell membrane upon contact, thereby disrupting its life cycle [

10,

53]. Hydrophilic surface properties allow absorption and rapid spreading of contaminated fluids, which helps with the contact-induced bacterial inactivation via electrostatic absorption [

54]. Hydrophilicity is also desirable for user-comfort and in applications such as inner layer of face mask, wound dressing, and sanitation.

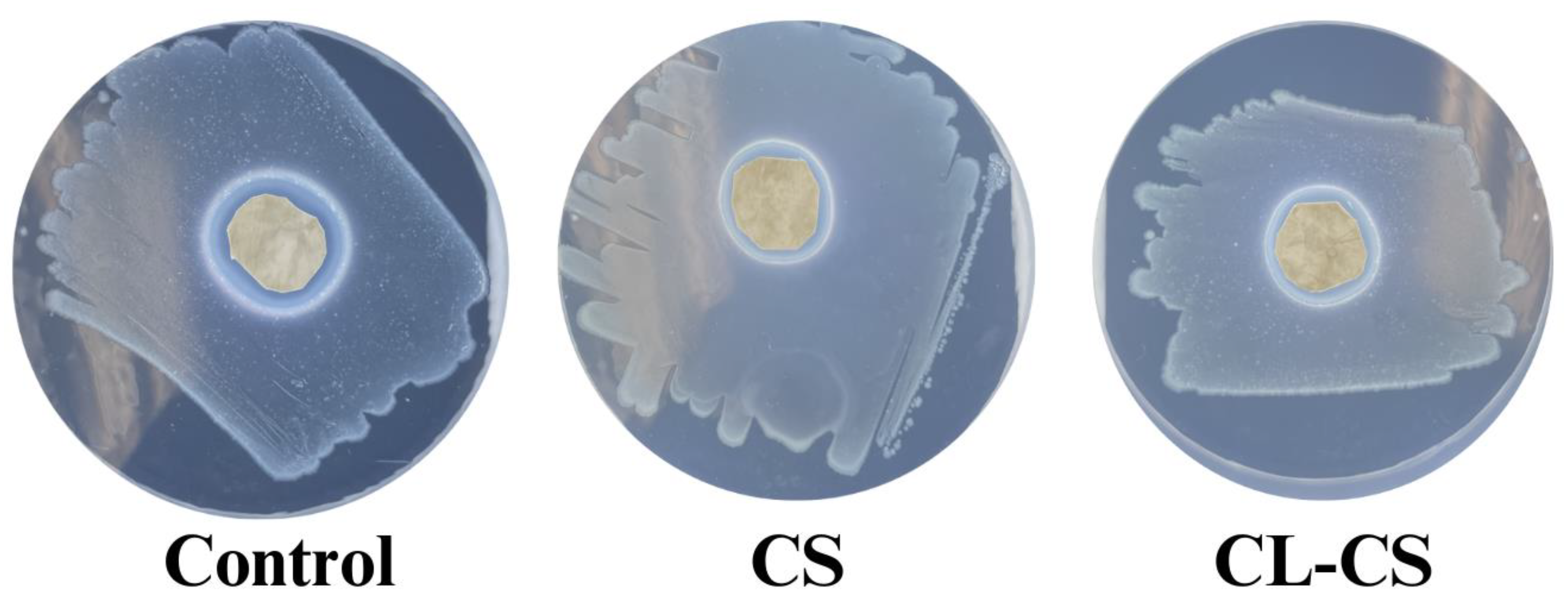

3.5 Antimicrobial Behavior of Nanomembranes –

The antimicrobial performance of the nanomembranes was tested as per AATCC-147 zone inhibition method. After 24 hours of incubation with the bacteria, all the samples (control, CS, and CL-CS) exhibited antimicrobial action through evident zones of inhibition (see

Figure 7 and

Table 3). The antimicrobial behavior observed in all the samples can be tied to the presence of cationic PL in each of them, known to exhibit contact induced antimicrobial action through electrostatic absorption [

10,

12].

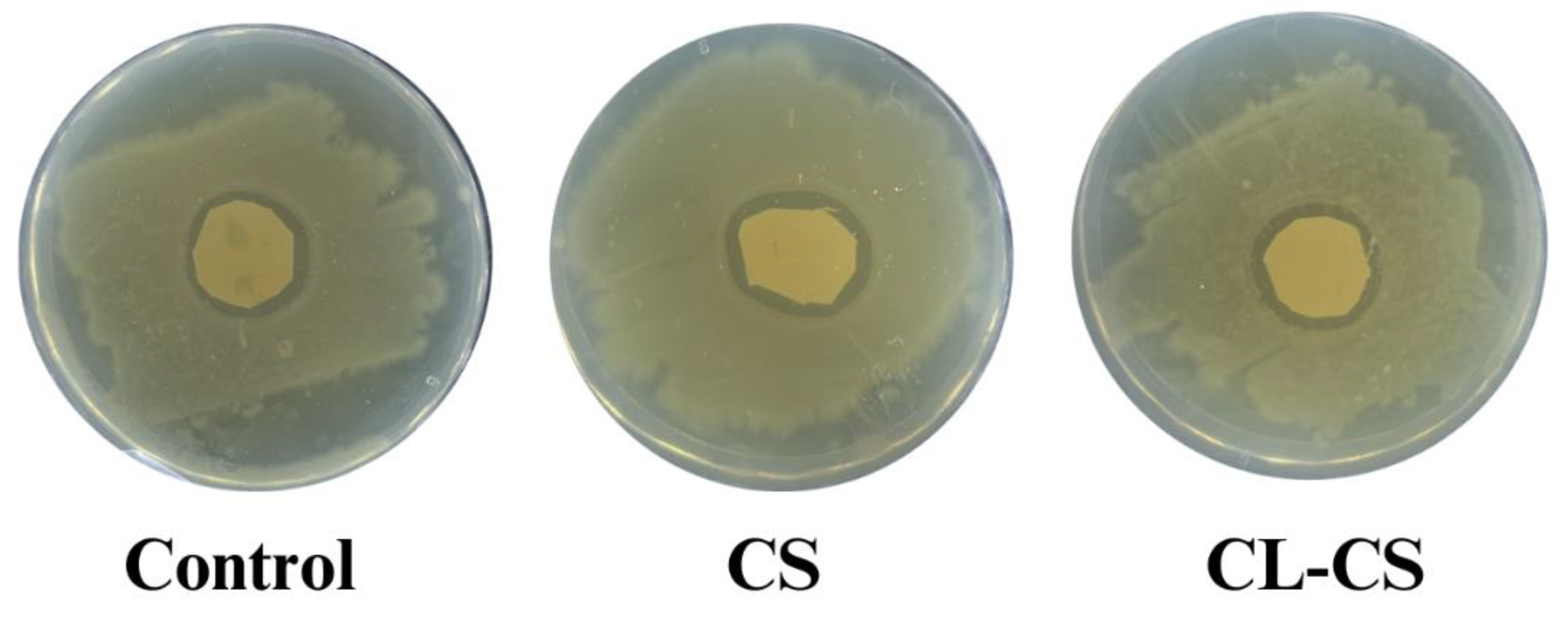

Cationic polymers such as PL can experience deteriorating antimicrobial function over time when there is exhaustion of cationic charge upon accumulation of cell debris on surface (Riga et al., 2017). Therefore, it is crucial to test the antimicrobial performance of nanomembranes against bacteria for a prolonged period. Such testing also showcases the sustained delivery of antimicrobial agents and allows the demonstration of clinical relevance [

13,

22,

56]. This study placed nanomembranes with bacterial culture for a period of 21 days under favorable bacterial growth conditions, to test whether there is sustained delivery and active cationic action after prolonged bacterial exposure. All the samples (control, CS, CL-CS) exhibited zones of inhibition after 21 days of incubation, thus ensuring antimicrobial activity despite the prolonged bacterial exposure (see

Figure 8 and

Table 4). Control sample exhibited significantly reduced antimicrobial activity after 21 days incubation in comparison to its antimicrobial activity after 24 hours incubation (p < 0.05). However, CS and CL-CS samples showed no significant difference between their antimicrobial activities after 24 hours and 21 days incubation (see Tables 7 and 8). This indicates that core-shell nanostructure can allow sustainable and durable antimicrobial function.

The reusability of antimicrobial performance was tested by rinsing and drying the samples between antimicrobial test cycles. The reusability of antimicrobial function was tested for three cycles. It was found that the CL-CS sample sustained all three cycles and continued to exhibit antimicrobial function. However, the antimicrobial function for the other two samples (control and CS) did not sustain reusability testing. The reason for the lack of reusable antimicrobial function in control and CS can be due to the water-soluble nature of PL [

57], along with swelling tendency and relative hydrophilicity of PA [

20], causing the PL to rapidly diffuse from the nanofiber system in presence of water [

58]. Physical crosslinking via thermal bonding can improve water resistance of water-soluble polymers [

32,

33,

59]. While the core-shell structure provides polymeric protective shell to the core. Therefore, the thermally bonded CL-CS nanomembranes preserved PL within the PA shell by preventing its rapid diffusion when exposed to rinsing, thereby allowing reusable antimicrobial function for all three rinsing cycles (see

Figure 9 and

Table 5).

4. Conclusions

Antimicrobial textiles are crucial to ensure health and safety of the wearer, especially in medical settings. Two criteria that remain important in terms of antimicrobial property in textiles are nontoxic antimicrobial agents and stable antimicrobial function that remains effective through the use of textile [

3,

5]. Electrospun nanofibers have various advantageous properties such as large surface area to volume, high loading capacity, and ease of spinnability. Therefore today, electrospun nanofibers are largely being explored in functional textile applications including antimicrobial textiles. Coaxial electrospinning is used to generate morphological variation to the conventional monolithic electrospun nanofibers. Core-shell nanofibers via coaxial electrospinning can generate nanofibers with antimicrobial core protected by polymeric shell, thereby allowing the sustained delivery of the antimicrobial core [

26,

27,

28].

PL is a naturally occurring biopolymer that exhibits a broad range of non-toxic antimicrobial performance owing to its cationic chemical structure [

10,

11]. This study explores the development of a core-shell fiber system by using PL as the core and structurally similar biocompatible PA as the shell (CS). A monolithic control sample of PL and PA was included for comparative analysis. Further, thermally crosslinked core shell sample (CL-CS) was also developed to allow reusable and durable antimicrobial property by preventing rapid diffusion of the water-soluble PL [

32,

33].

The morphological analysis conducted via FESEM and TEM provided evidence of the creation of continuous nanofibers with core and shell phases. The elemental composition of the nanomembranes was analyzed via FTIR. The analysis exhibited characteristic peaks of PA and PL for all samples. The FTIR analysis also demonstrated a slight red shift for amide A peak in CL-CS compared to the CS sample. This shift can be tied to the replacement of amide-water hydrogen bonds with amide-amide hydrogen bonds during the dehydrothermal crosslinking [

42,

43]. The XPS analysis exhibited a higher N/O ratio for the control sample as compared to CS and CL-CS samples. This demonstrates the presence of both the polymers on the surface of monolithic nanofibers whereas the absence of PL on the surface for core-shell structure. The static water contact angle testing exhibited hydrophilic behavior of all the samples as a result of the inherently hydrophilic PL being part of the fiber systems. The hydrophilicity is desirable for user comfort while benefiting the contact-induced antimicrobial action. All the samples (control, CS, and CL-CS) exhibited antimicrobial function by displaying zones of inhibition, when incubated with bacteria for 24 hours and 21 days. Antimicrobial function in the samples is due to the presence of cationic PL in the fibers. Unlike the control sample, CS and CL-CS samples showed no significant difference between the antimicrobial activity after 24 hours and 21 days of incubation. Thus, confirming that the core-shell structure allows sustainable and durable antimicrobial action. Lastly, CL-CS sample exhibited reusable antimicrobial function as opposed to the other two samples owing to the core-shell structural paired with thermal crosslinking that prevented rapid diffusion of PL from the fiber system.

This study thus demonstrates the generation of a fiber system with non-toxic, stable, durable, and reusable antimicrobial function; achieved via structural variation and inclusion of natural antimicrobial agent. The developed fiber systems can be explored for medical textile applications such as inner layer of face mask, wound dressing, and sanitation. This study hopes to build grounds for further exploration of non-toxic fiber systems that are capable of satisfying the multi-faceted requirements of antimicrobial textile for their practical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and C.X.; methodology, C.X. and R.L.; investigation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing— review and editing, G.S., C.X. and R.L.; supervision, C.X., R.L. and G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by CDC NIOSH, grant number R01 OH011947-01A1; this research was partially funded by DHS FEMA, grant number EMW-2021-FP-00088.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors..

Acknowledgments

Sincerely thankful Dr. Zhiyou Wen and Show-Ling Lee at Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, Iowa State University for letting the author use their lab space.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Stokes, K., Peltrini, R., Bracale, U., Trombetta, M., Pecchia, L., & Basoli, F. (2021). Enhanced medical and community face masks with antimicrobial properties: a systematic review. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(18), 4066. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184066. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V., Jose, S., Badanayak, P., Sankaran, A., & Anandan, V. (2022). Antimicrobial finishing of metals, metal oxides, and metal composites on textiles: a systematic review. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 61(1), 86-101. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.1c04203. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A., Kidanemariam, A., Lee, D., Pham, T. T. D., & Park, J. (2024). Durability of antimicrobial agent on nanofiber: A collective review from 2018 to 2022. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 130, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Simončič, B., & Klemenčič, D. (2016). Preparation and performance of silver as an antimicrobial agent for textiles: A review. Textile Research Journal, 86(2), 210-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517515586. [CrossRef]

- Karypidis, M., Karanikas, E., Papadaki, A., & Andriotis, E. G. (2023). A mini-review of synthetic organic and nanoparticle antimicrobial agents for coatings in textile applications. Coatings, 13(4), 693. [CrossRef]

- Lencova, S., Stiborova, H., Munzarova, M., Demnerova, K., & Zdenkova, K. (2022). Potential of Polyamide Nanofibers With Natamycin, Rosemary Extract, and Green Tea Extract in Active Food Packaging Development: Interactions With Food Pathogens and Assessment of Microbial Risks Elimination. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 857423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.857423. [CrossRef]

- Khanzada, H., Salam, A., Qadir, M. B., Phan, D. N., Hassan, T., Munir, M. U., ... & Kim, I. S. (2020). Fabrication of promising antimicrobial aloe vera/PVA electrospun nanofibers for protective clothing. Materials, 13(17), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13173884. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., El-Moghazy, A. Y., Wisuthiphaet, N., Nitin, N., Castillo, D., Murphy, B. G., & Sun, G. (2020). Daylight-induced antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes containing vitamin K derivatives for personal protective equipment. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 12(44), 49416-49430. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c14883. [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S., Azadi, E., & Hussain, C. M. (2021). Protection, disinfection, and immunization for healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic: Role of natural and synthetic macromolecules. Science of the Total Environment, 776, 145989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145989. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., Chen, X., Jia, F., Wang, S., Xiao, C., Cui, F., ... & Wang, X. (2015). New chemosynthetic route to linear ε-poly-lysine. Chemical science, 6(11), 6385-6391. 10.1039/C5SC02479J. [CrossRef]

- Patil, N. A., & Kandasubramanian, B. (2021). Functionalized polylysine biomaterials for advanced medical applications: A review. European Polymer Journal, 146, 110248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.110248. [CrossRef]

- Shima, S., Matsuoka, H., Iwamoto, T., & Sakai, H. (1984). Antimicrobial action of ε-poly-L-lysine. The Journal of antibiotics, 37(11), 1449-1455. https://doi.org/10.7164/antibiotics.37.1449. [CrossRef]

- Amariei, G., Kokol, V., Vivod, V., Boltes, K., Letón, P., & Rosal, R. (2018). Biocompatible antimicrobial electrospun nanofibers functionalized with ε-poly-l-lysine. International journal of pharmaceutics, 553(1-2), 141-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.10.037. [CrossRef]

- Mayandi, V., Wen Choong, A. C., Dhand, C., Lim, F. P., Aung, T. T., Sriram, H., ... & Lakshminarayanan, R. (2020). Multifunctional antimicrobial nanofiber dressings containing ε-polylysine for the eradication of bacterial bioburden and promotion of wound healing in critically colonized wounds. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 12(14), 15989-16005. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b21683. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., Xue, L., Duraiarasan, S., & Haiying, C. (2018). Preparation of ε-polylysine/chitosan nanofibers for food packaging against Salmonella on chicken. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 17, 134-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2018.06.013. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Liu, Y., Sun, Z., Wang, D., Wu, H., Du, L., & Wang, D. (2020). Preparation and antibacterial properties of ε-polylysine-containing gelatin/chitosan nanofiber films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 164, 3376-3387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.152. [CrossRef]

- Dias, Y. J., Robles, J. R., Sinha-Ray, S., Abiade, J., Pourdeyhimi, B., Niemczyk-Soczynska, B., ... & Yarin, A. L. (2021). Solution-blown poly (hydroxybutyrate) and ε-poly-l-lysine submicro-and microfiber-based sustainable nonwovens with antimicrobial activity for single-use applications. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 7(8), 3980-3992. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c00594. [CrossRef]

- Souri, Z., Hedayati, S., Niakousari, M., & Mazloomi, S. M. (2023). Fabrication of ɛ-Polylysine-Loaded Electrospun Nanofiber Mats from Persian Gum–Poly (Ethylene Oxide) and Evaluation of Their Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties. Foods, 12(13), 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132588. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Chen, H., Shi, Z., Liu, Y., Liu, L., Yu, J., & Fan, Y. (2023). Preparation of amino cellulose nanofiber via ε-poly-L-lysine grafting with enhanced mechanical, anti-microbial and food preservation performance. Industrial Crops and Products, 194, 116288. [CrossRef]

- Purandare, S., Li, R., Xiang, C., & Song, G. (2024). Development of Innovative Composite Nanofiber: Enhancing Polyamide-6 with ε-Poly-L-Lysine for Medical and Protective Textiles. Polymers, 16(14), 2046. [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F., Wang, F. P., Xie, Y. Y., Chu, L. Q., Jia, S. R., Duan, Y. X., ... & Zhong, C. (2019). Reusable ternary PVA films containing bacterial cellulose fibers and ε-polylysine with improved mechanical and antibacterial properties. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110486. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Lee, Y. K., Lee, Y., Hwang, W. T., Lee, J., Park, S., ... & Im, S. G. (2023). Anti-viral, anti-bacterial, but non-cytotoxic nanocoating for reusable face mask with efficient filtration, breathability, and robustness in humid environment. Chemical Engineering Journal, 470, 144224. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., Wu, T., Dai, Y., & Xia, Y. (2019). Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Methods, materials, and applications. Chemical reviews, 119(8), 5298-5415. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00593. [CrossRef]

- Teo, W. E., & Ramakrishna, S. (2006). A review on electrospinning design and nanofiber assemblies. Nanotechnology, 17(14), R89. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202100410. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhu, J., Cheng, H., Li, G., Cho, H., Jiang, M., ... & Zhang, X. (2021). Developments of advanced electrospinning techniques: A critical review. Advanced Materials Technologies, 6(11), 2100410. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202100410. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., Ghosh, C., Hwang, S. G., Chanunpanich, N., & Park, J. S. (2012). Porous core/sheath composite nanofibers fabricated by coaxial electrospinning as a potential mat for drug release system. International journal of pharmaceutics, 439(1-2), 296-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.09.019. [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, A., Shaibani, P. Á., Etayash, H., Kaur, K., & Thundat, T. (2013). Sustained drug release and antibacterial activity of ampicillin incorporated poly (methyl methacrylate)–nylon6 core/shell nanofibers. Polymer, 54(11), 2699-2705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2013.03.046. [CrossRef]

- Ulubayram, K., Calamak, S., Shahbazi, R., & Eroglu, I. (2015). Nanofibers based antibacterial drug design, delivery and applications. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 21(15), 1930-1943. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cpd/2015/00000021/00000015/art00004. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, J. X., Tang, R. C., & Zhai, A. D. (2020). Hydrophilic and antibacterial surface functionalization of polyamide fabric by coating with polylysine biomolecule. Progress in Organic Coatings, 142, 105571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.105571. [CrossRef]

- Matulevicius, J., Kliucininkas, L., Martuzevicius, D., Krugly, E., Tichonovas, M., & Baltrusaitis, J. (2014). Design and characterization of electrospun polyamide nanofiber media for air filtration applications. Journal of nanomaterials, 2014, 14-14. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C., & Frey, M. W. (2016). Increasing mechanical properties of 2-D-structured electrospun nylon 6 non-woven fiber mats. Materials, 9(4), 270. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Morales, J., Amariei, G., Letón, P., & Rosal, R. (2016). Antimicrobial activity of poly (vinyl alcohol)-poly (acrylic acid) electrospun nanofibers. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 146, 144-151. [CrossRef]

- Lan, X., Luo, T., Zhong, Z., Huang, D., Liang, C., Liu, Y., ... & Tang, Y. (2022). Green cross-linking of gelatin/tea polyphenol/ε-poly (L-lysine) electrospun nanofibrous membrane for edible and bioactive food packaging. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 34, 100970. [CrossRef]

- ASTM, D. (2008). 7334-08; Standard Practice for Surface Wettability of Coatings, Substrates and Pigments by Advancing Contact Angle Measurement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA.

- AATCC. (2011). TM147: Antibacterial activity assessment of textile materials: Parallel streak method. American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists. American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: Triangle Park, NC, USA.

- Xiong, S. W., Fu, P. G., Zou, Q., Chen, L. Y., Jiang, M. Y., Zhang, P., ... & Gai, J. G. (2020). Heat conduction and antibacterial hexagonal boron nitride/polypropylene nanocomposite fibrous membranes for face masks with long-time wearing performance. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 13(1), 196-206. [CrossRef]

- Koombhongse S, Liu W, Reneker DH. Flat polymer ribbons and other shapes by electrospinning. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics. 2001 Nov 1;39(21):2598-606. https://doi.org/10.1002/polb.10015. [CrossRef]

- Itoh H, Li Y, Chan KH, Kotaki M. Morphology and mechanical properties of PVA nanofibers spun by free surface electrospinning. Polymer Bulletin. 2016 Oct;73:2761-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-016-1620-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Li, R., Dong, F., Tian, A., Li, Z., & Dai, Y. (2015). Physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of starch films incorporated with ε-poly-l-lysine. Food Chemistry, 166, 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Wu C, Sun J, Lu Y, Wu T, Pang J, Hu Y. In situ self-assembly chitosan/ε-polylysine bionanocomposite film with enhanced antimicrobial properties for food packaging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019 Jul 1;132:385-92.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.133. [CrossRef]

- Rotter G, Ishida H. FTIR separation of nylon-6 chain conformations: Clarification of the mesomorphous and γ-crystalline phases. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics. 1992 Apr;30(5):489-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/polb.1992.090300508. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, B., Kawakami, T., Shigemoto, I., Sugita, Y., & Yagi, K. (2017). Weight-averaged anharmonic vibrational analysis of hydration structures of polyamide 6. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 121(24), 6050-6063. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Zhou, L., Xu, H., Yamamoto, M., Shinoda, M., Kishimoto, M., ... & Yamane, H. (2020). Effect of the Application of a Dehydrothermal Treatment on the Structure and the Mechanical Properties of Collagen Film. Materials, 13(2), 377. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Lan, X., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Tian, F., Li, Q., ... & Tang, Y. (2022). Preparation and in vitro evaluation of ε-poly (L-lysine) immobilized poly (ε-caprolactone) nanofiber membrane by polydopamine-assisted decoration as a potential wound dressing material. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 220, 112945. [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, L. M. W. K., & Shanks, R. A. (2005). Multiple melting behaviour of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) using step-scan DSC. European Polymer Journal, 41(12), 2980-2988. [CrossRef]

- Asran, A. S., Razghandi, K., Aggarwal, N., Michler, G. H., & Groth, T. (2010). Nanofibers from blends of polyvinyl alcohol and polyhydroxy butyrate as potential scaffold material for tissue engineering of skin. Biomacromolecules, 11(12), 3413-3421. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Yan, K. W., Lin, Y. D., & Hsieh, P. C. (2010). Biodegradable core/shell fibers by coaxial electrospinning: processing, fiber characterization, and its application in sustained drug release. Macromolecules, 43(15), 6389-6397. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Li, R., Dong, F., Tian, A., Li, Z., & Dai, Y. (2015). Physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of starch films incorporated with ε-poly-l-lysine. Food Chemistry, 166, 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Liu, C., Hsu, P. C., Xu, J., Kong, B., Wu, T., ... & Cui, Y. (2018). Core–shell nanofibrous materials with high particulate matter removal efficiencies and thermally triggered flame retardant properties. ACS central science, 4(7), 894-898. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Ma, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., & Sun, D. (2018). Potential of rhBMP-2 and dexamethasone-loaded Zein/PLLA scaffolds for enhanced in vitro osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 169, 384-394. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H. F., Luqman, M., Khalil, K. A., Elnakady, Y. A., Abd-Elkader, O. H., Rady, A. M., ... & Karim, M. R. (2018). Fabrication of core-shell structured nanofibers of poly (lactic acid) and poly (vinyl alcohol) by coaxial electrospinning for tissue engineering. European Polymer Journal, 98, 483-491. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Su, Y., He, C., Wang, H., Fong, H., & Mo, X. (2008). Sorbitan monooleate and poly (l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) electrospun nanofibers for endothelial cell interactions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials, 91(3), 878-885.

- Li, M., & Tao, Y. (2021). Poly (ε-lysine) and its derivatives via ring-opening polymerization of biorenewable cyclic lysine. Polymer Chemistry, 12(10), 1415-1424. 10.1039/D0PY01387K. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Sun, L., Zhao, B., Fang, Y., Qi, Y., Ning, G., & Ye, J. (2023). Reusable electrospun nanofibrous membranes with antibacterial activity for air filtration. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 6(12), 10872-10880. [CrossRef]

- Riga, E. K., Vöhringer, M., Widyaya, V. T., & Lienkamp, K. (2017). Polymer-Based Surfaces Designed to Reduce Biofilm Formation: From Antimicrobial Polymers to Strategies for Long-Term Applications. Macromolecular rapid communications, 38(20), 1700216. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, M., Yang, S. Y., & Asmatulu, R. (2017). Effects of gentamicin-loaded PCL nanofibers on growth of Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria.

- Takehara, M., & Hirohara, H. (2010). Occurrence and production of poly-epsilon-l-lysine in microorganisms. Amino-Acid Homopolymers Occurring in Nature, 1-22.

- Rosenberg, R., Devenney, W., Siegel, S., & Dan, N. (2007). Anomalous release of hydrophilic drugs from poly (ϵ-caprolactone) matrices. Molecular pharmaceutics, 4(6), 943-948. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Y., Wang, P. F., Li, H. X., Yang, Y. J., & Rao, S. Q. (2023). Enhanced Antibacterial Efficiency and Anti-Hygroscopicity of Gum Arabic–ε-Polylysine Electrostatic Complexes: Effects of Thermal Induction. Polymers, 15(23), 4517. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).