1. Introduction

Ultra-high-bypass-ratio geared turbofans (GTFs) reduce

and noise. For bypass ratios

they enable lower specific fuel consumption, fewer low-pressure turbine stages, and reduced engine mass [

13] – the low-pressure turbine (LPT) can account for one-third of the engine mass [

14].

Torre et al. [

15] investigated a high-speed LPT in a transonic rotating rig and documented key differences from conventional LPT operation. In geared architectures, the higher shaft speed drives the LPT blading sections to transonic exit Mach numbers (

) and low Reynolds numbers at cruise [

16]. This combined transonic/low-Reynolds number regime is a principal challenge for GTF LPT design [

17,

18].

In conventional LPTs, profile losses typically exceed secondary losses because of their high aspect ratio [

14]. Under engine-representative conditions, they can be comparable [

19].

Vera et al. [

20] showed that profile loss is nearly independent of Mach up to

and rises beyond at

. Vázquez et al. [

21] observed increasing loss with Mach and decreasing loss with Reynolds number in an annular cascade. Both works attributed the Mach effect to higher dynamic pressure and altered suction side loading [

20,

21].

Perdichizzi [

22] reported that higher outlet Mach confines secondary structures toward the endwall, reducing under/overturning and net loss. Mach and Reynolds effects were not decoupled for LPT conditions. Vázquez et al. [

21] found endwall losses decrease with off-design Mach at fixed Reynolds number. Vázquez and Torre [

23] confirmed the Mach effect at fixed incidence and linked it to off-design loading changes.

Hodson and Dominy [

24] reported increasing secondary loss with Reynolds number near

. Duden and Fottner [

25] found secondary loss decreasing as both Mach and Reynolds increased for other LPT blades.

Despite this literature, few studies target the combined high Mach number, very-low-Reynolds number regime () that can exist in high-speed LPT blading. To our knowledge, no open database provides on- and off-design measurements for a high-speed LPT linear cascade.

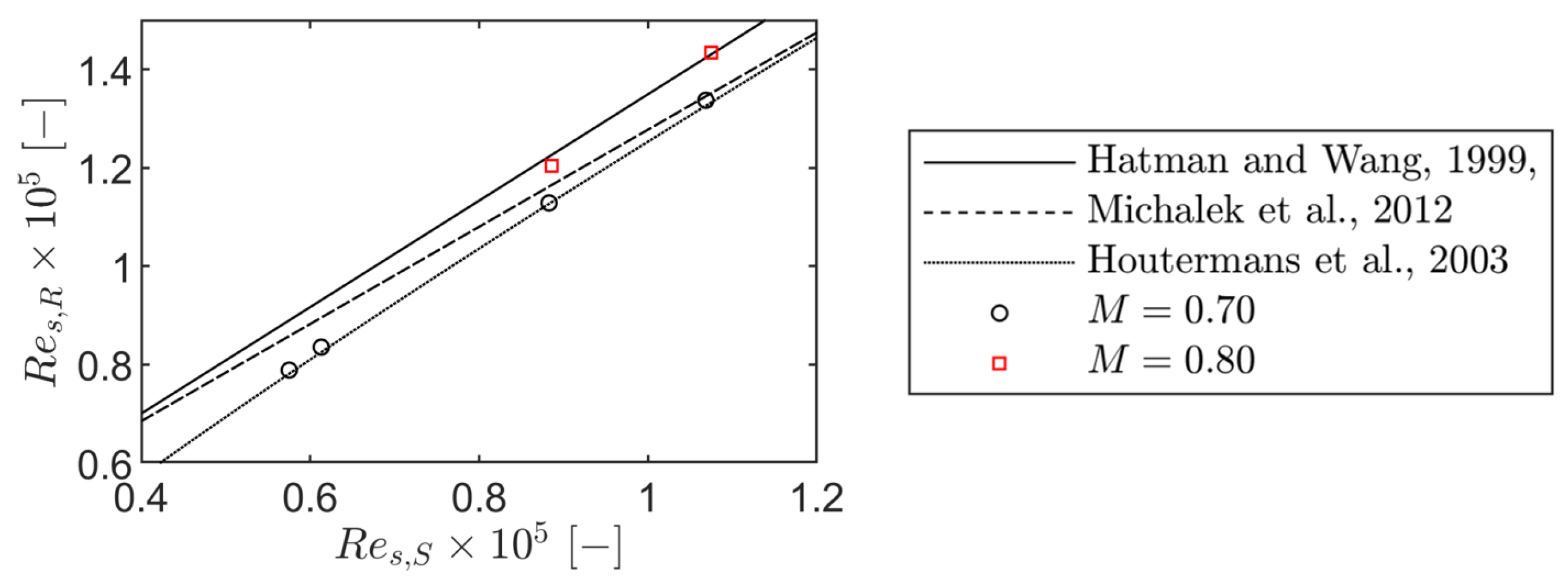

This study extends the open SPLEEN C1 test case. Operating points spanned

and

under steady inlet flow. Experiments were combined with 2D Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) computations and MISES with transition modelling. Inlet turbulence decay was calibrated to hot-wire measurements. Separation and reattachment were identified using an acceleration-parameter method anchored to the data. Profile and secondary losses were decomposed, and loss models were assessed under high-speed LPT conditions. The study builds upon and expands [

26]. The data presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7264761, reference number [

66] (accessed September 9, 2025).

5. Conclusions

This work examined the SPLEEN C1 high-speed low-pressure turbine cascade over sixteen steady operating points, and . Experiments were combined with 2D RANS and MISES to assess transition and loss modeling. Matching the measured inlet turbulence decay in RANS required tuning and an effective integral length scale; using the measured length scale produced a decay that was too slow. In MISES, a calibrated inlet intensity of improved suction side loading and bubble topology.

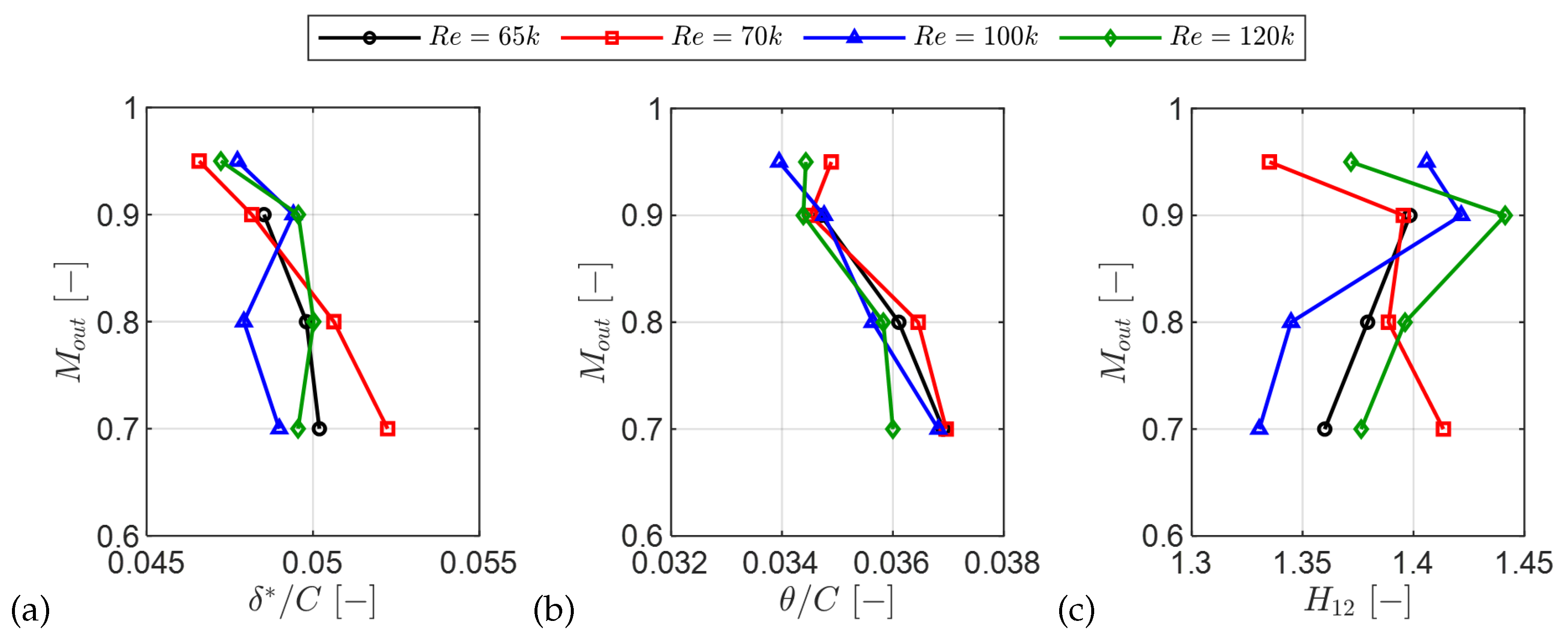

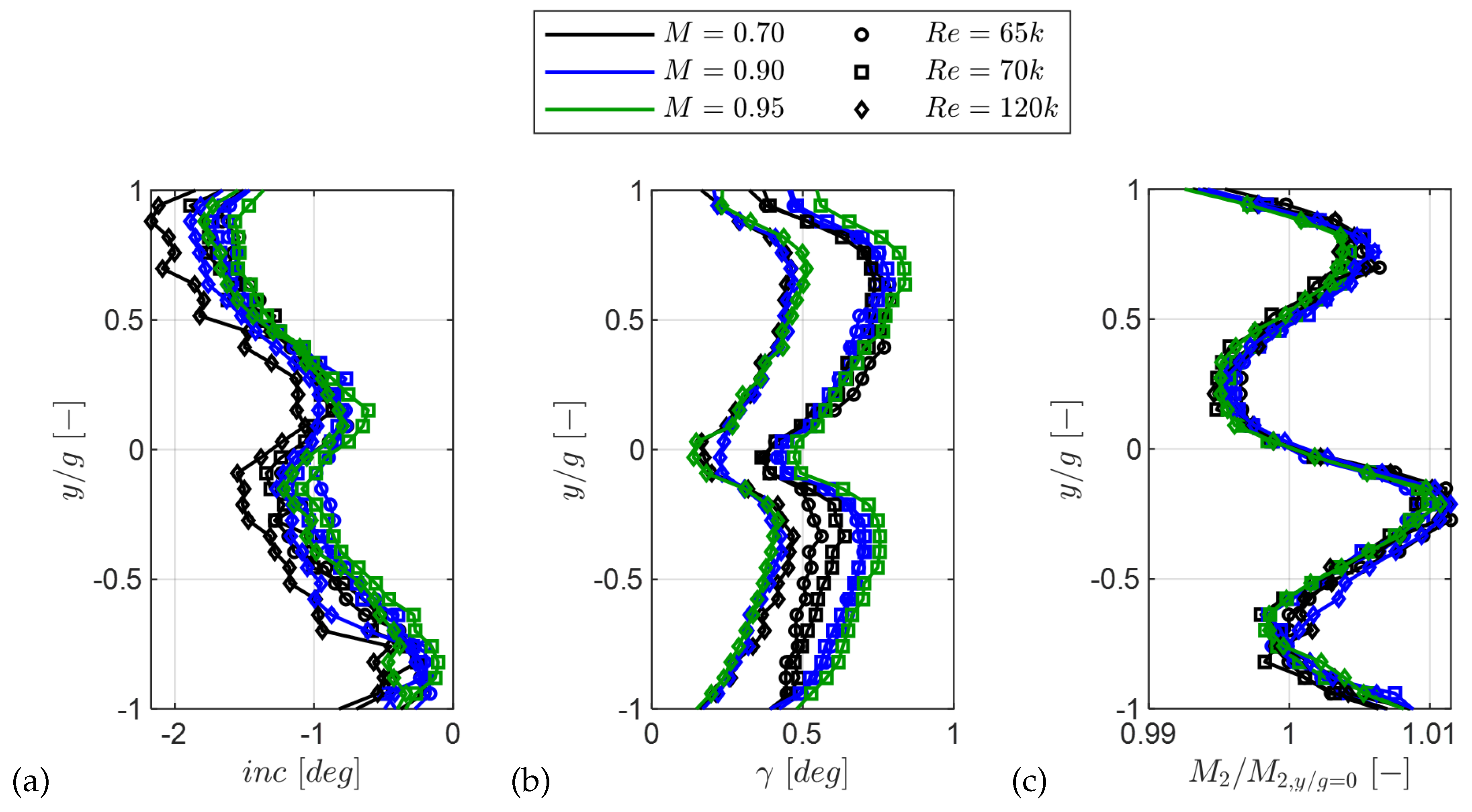

The inlet boundary layer at Plane 01 was essentially invariant across the matrix: the spanwise mean total-pressure deficit remained within of the inlet freestream total pressure; the displacement and momentum thickness varied by and ; the shape factor stayed near . At Plane 02, the mean incidence was with a pitchwise range of and a cross-condition variation of at fixed pitch.

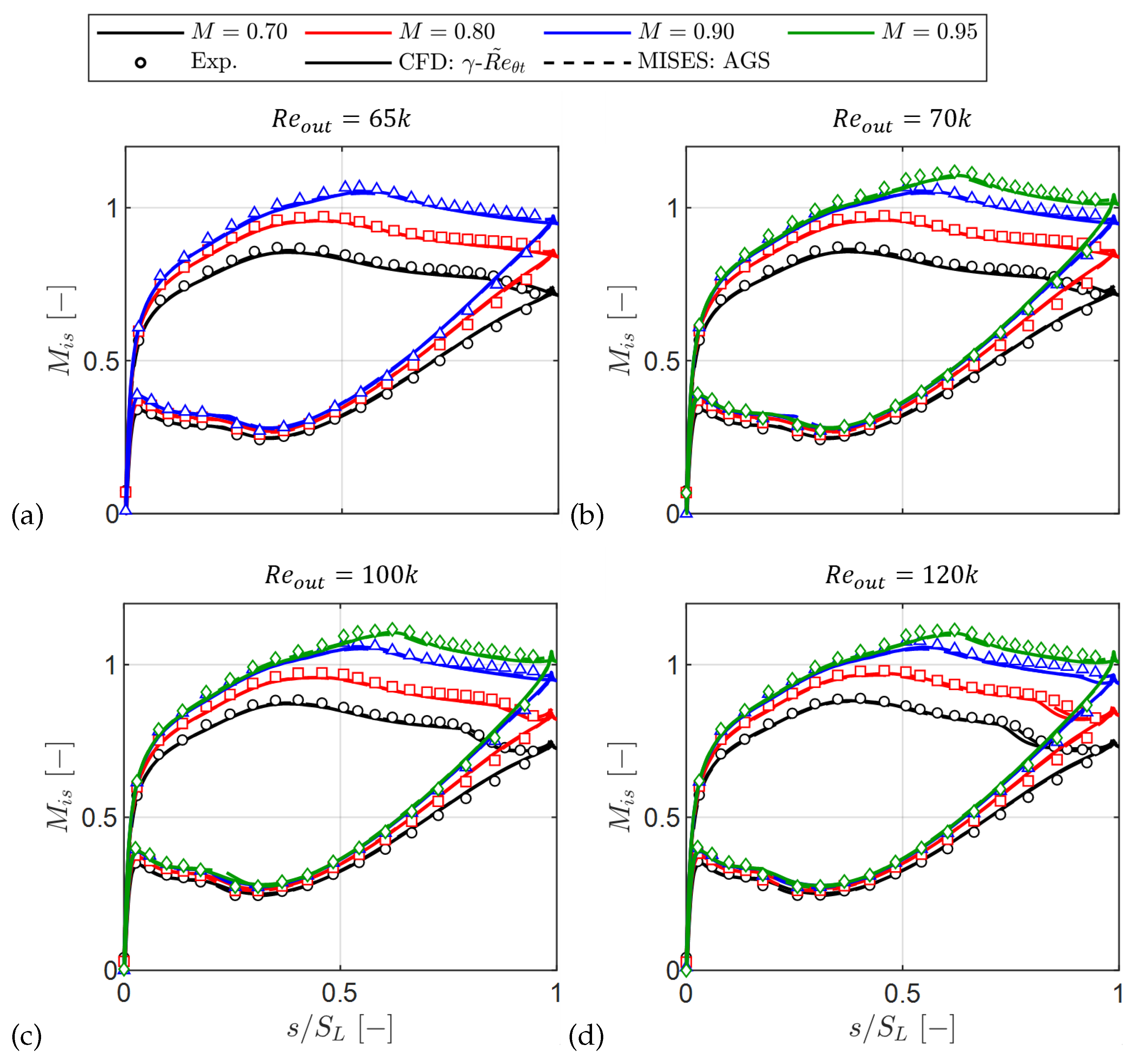

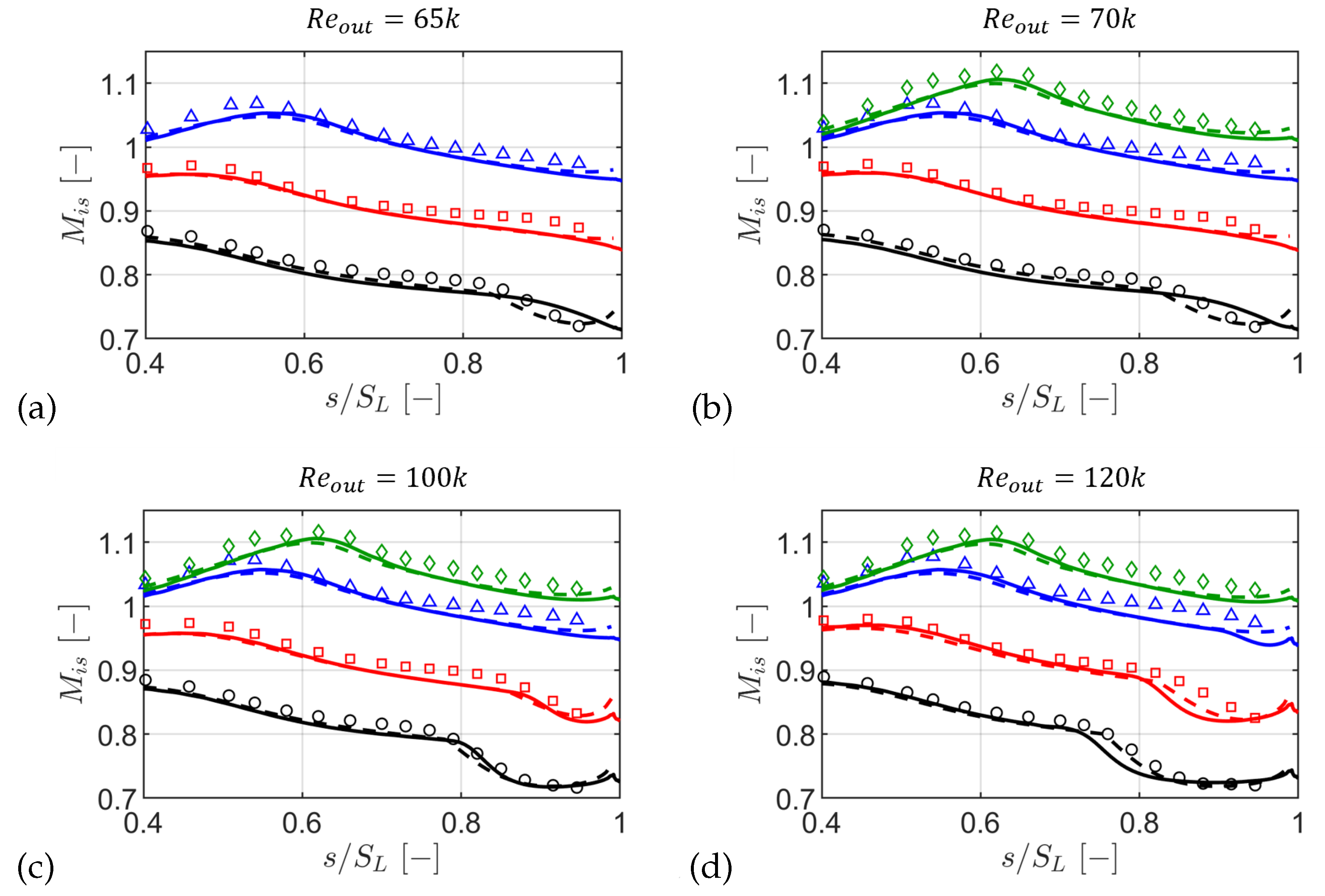

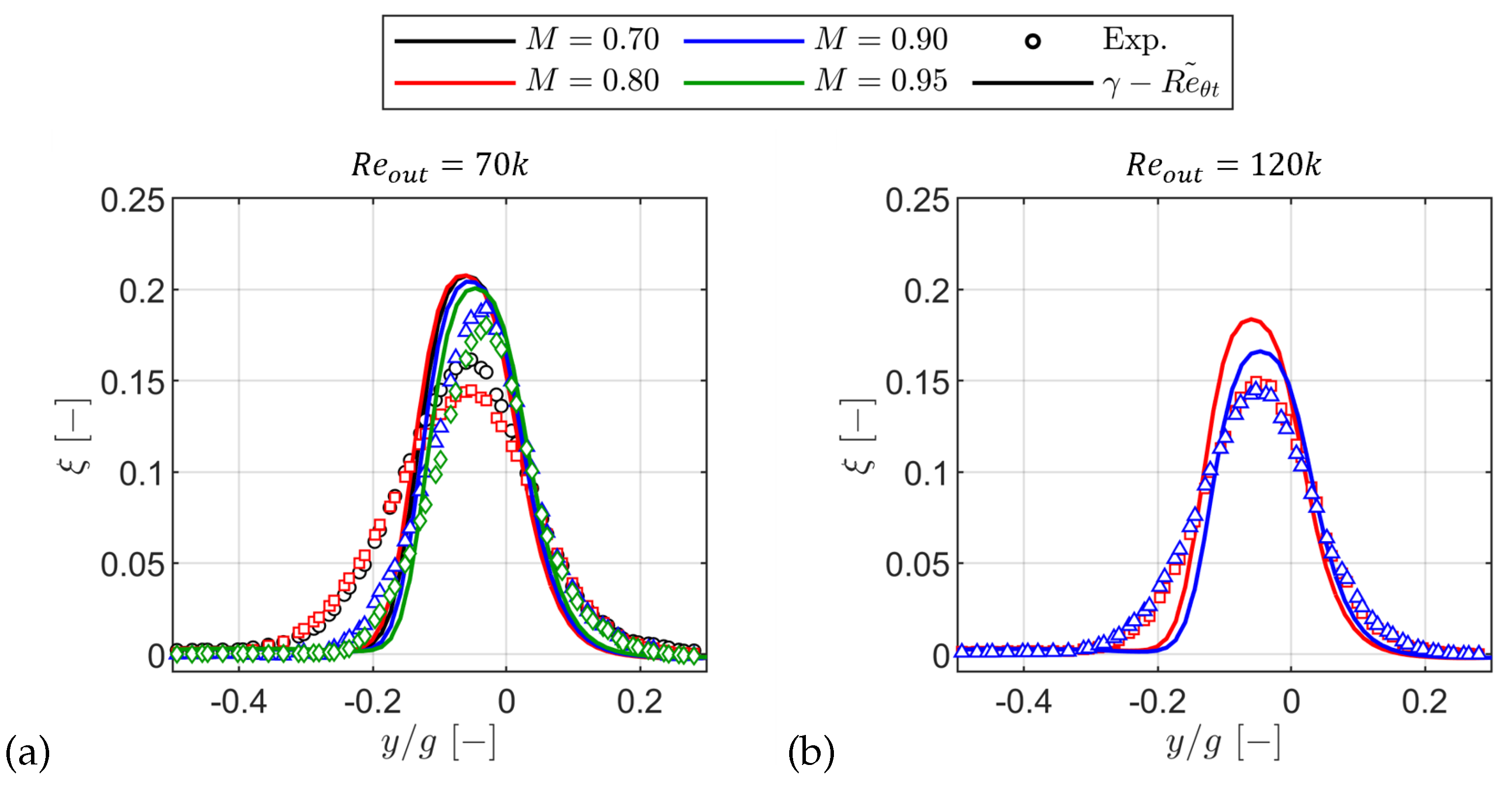

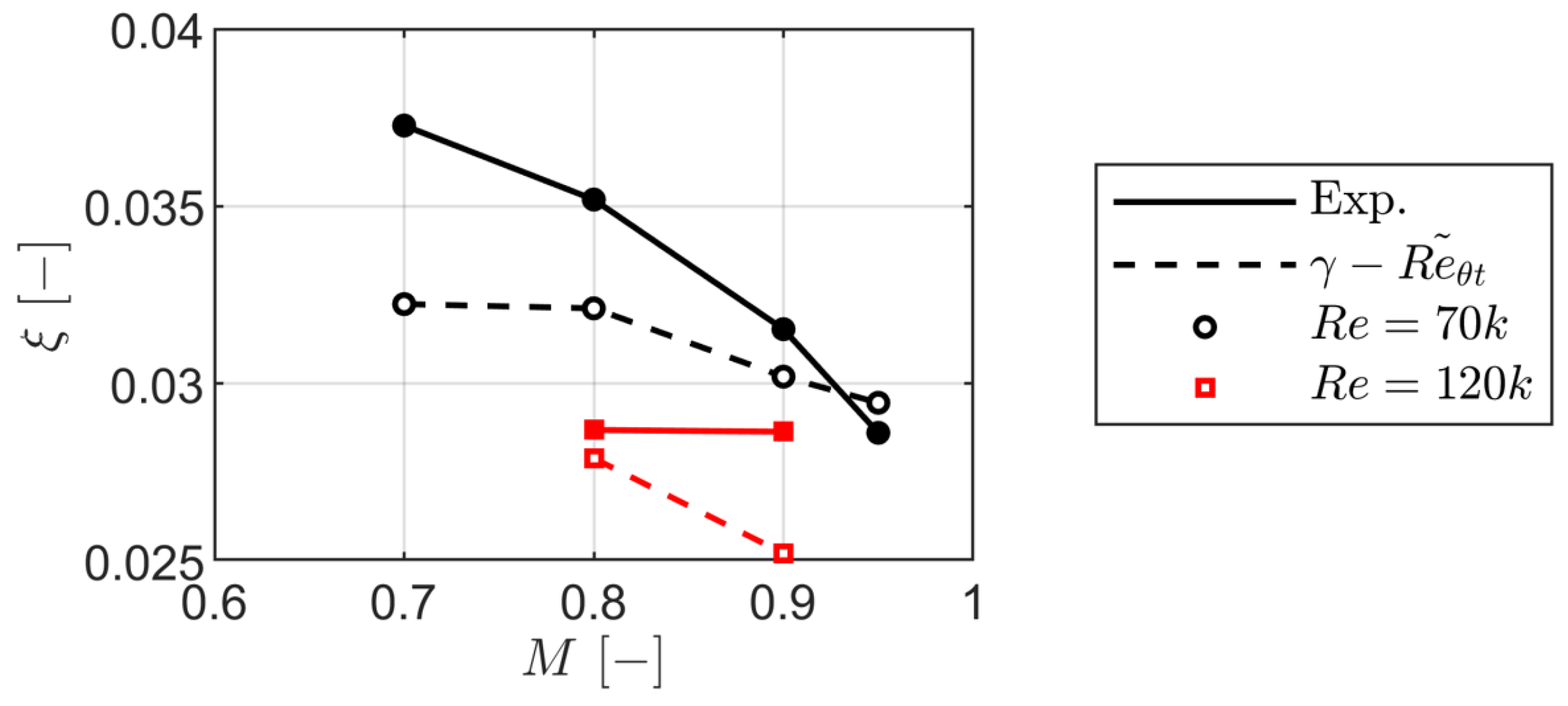

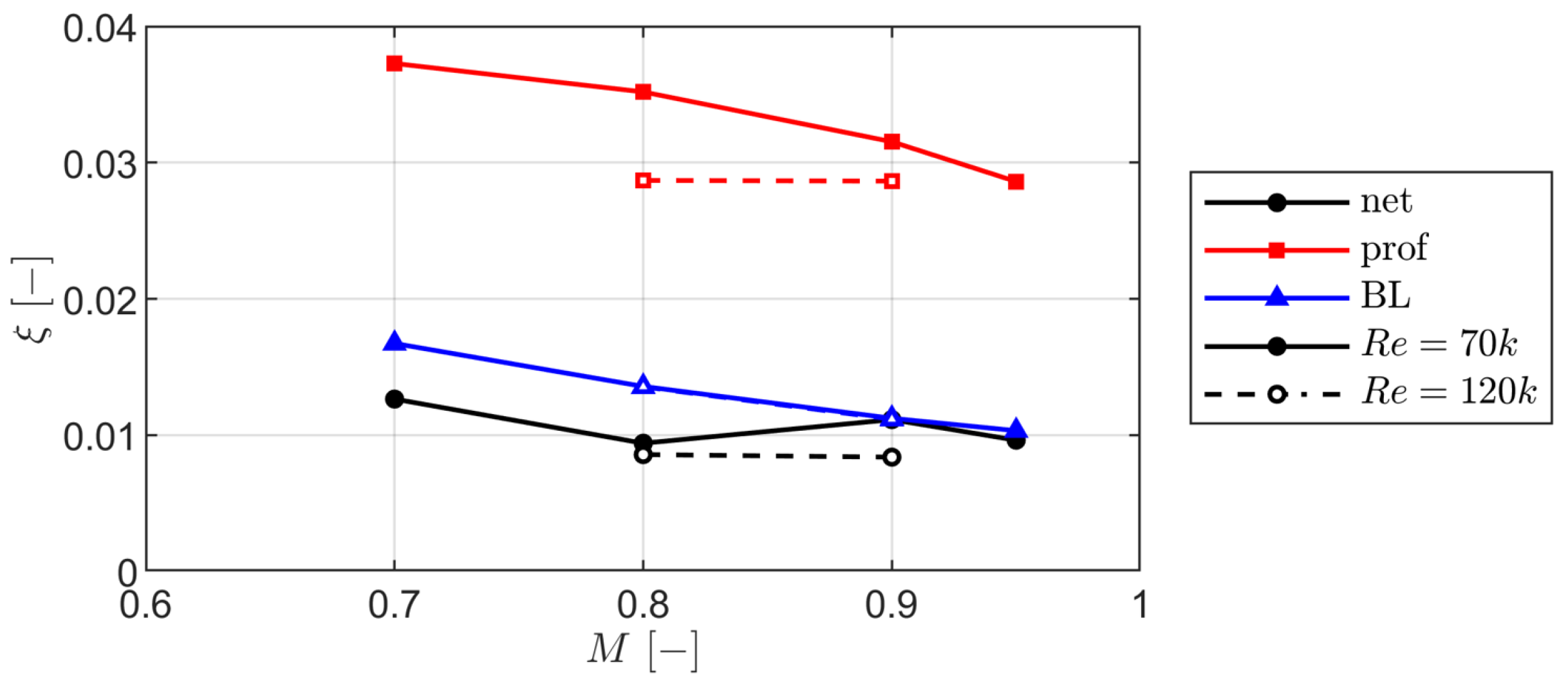

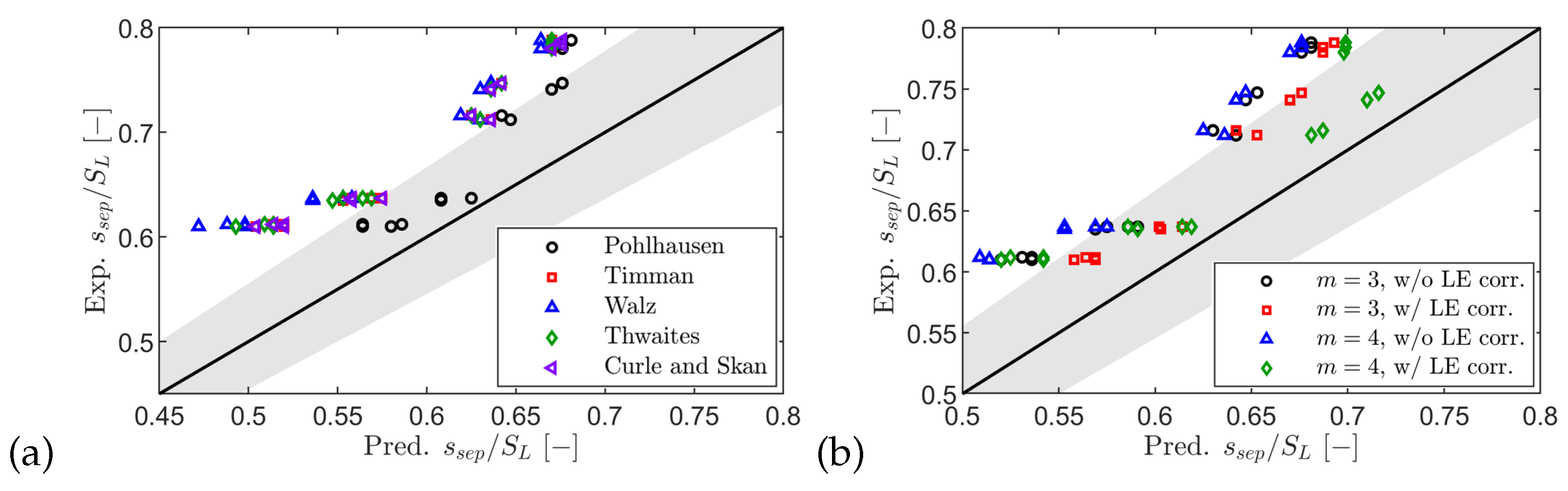

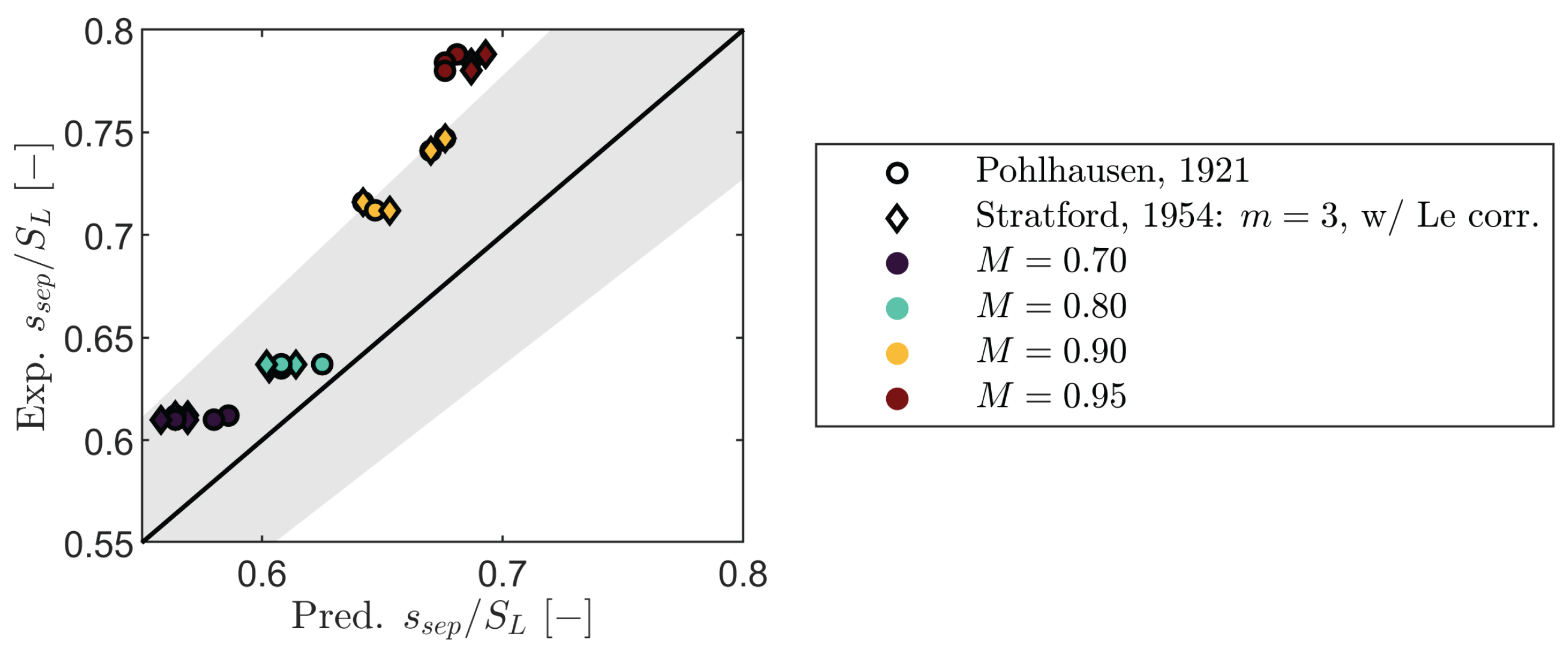

RANS and MISES generally reproduced midspan loading; at the lowest Reynolds numbers RANS struggled to capture open separation and late reattachment near the trailing edge. Separation and reattachment locations inferred from data agreed with flat-plate and linear cascade correlations for cases without shock-boundary layer interactions. Profile loss decreased with both Mach number and Reynolds number: at the lowest Reynolds number the measured mass-averaged kinetic energy loss dropped by between and (RANS: ). Suppressing open separation at reduced the measured loss by .

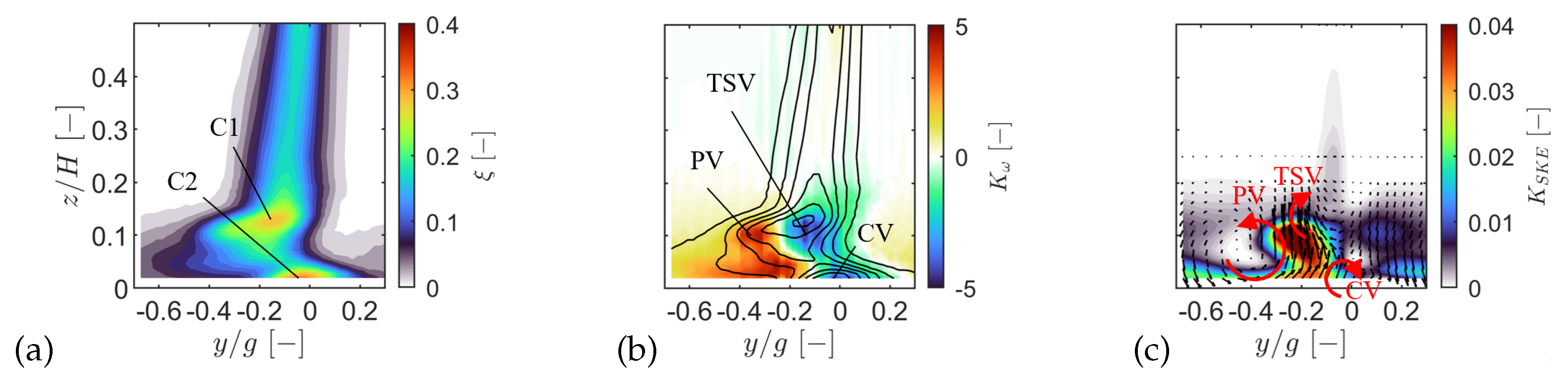

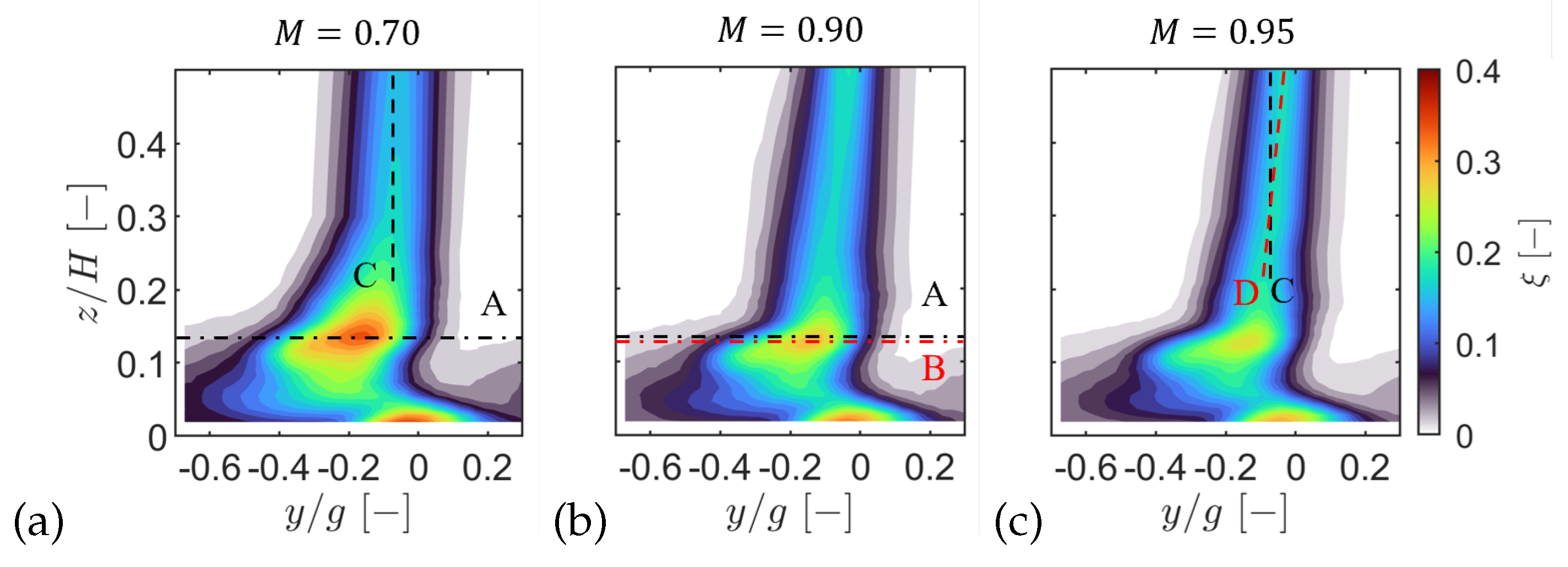

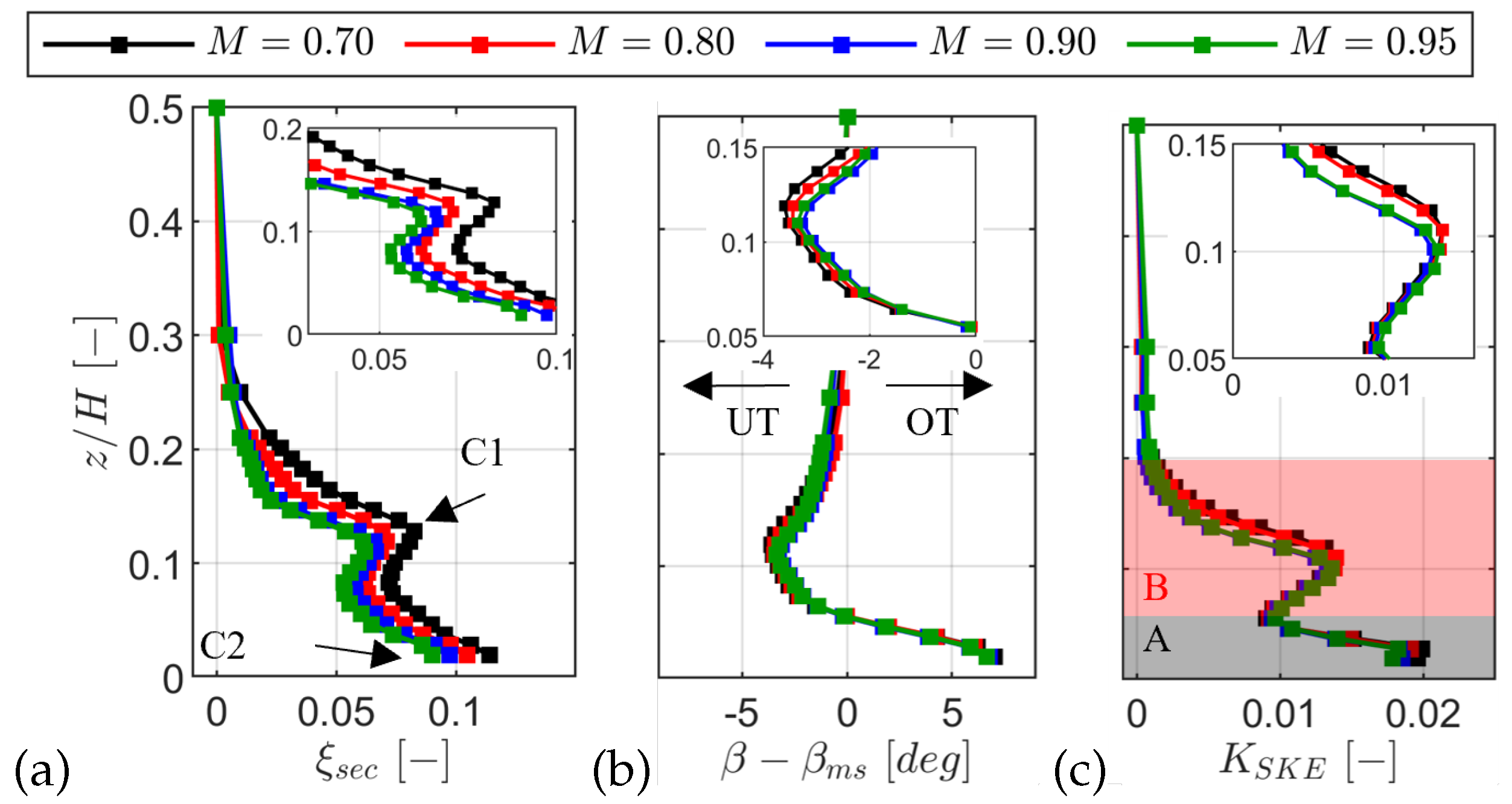

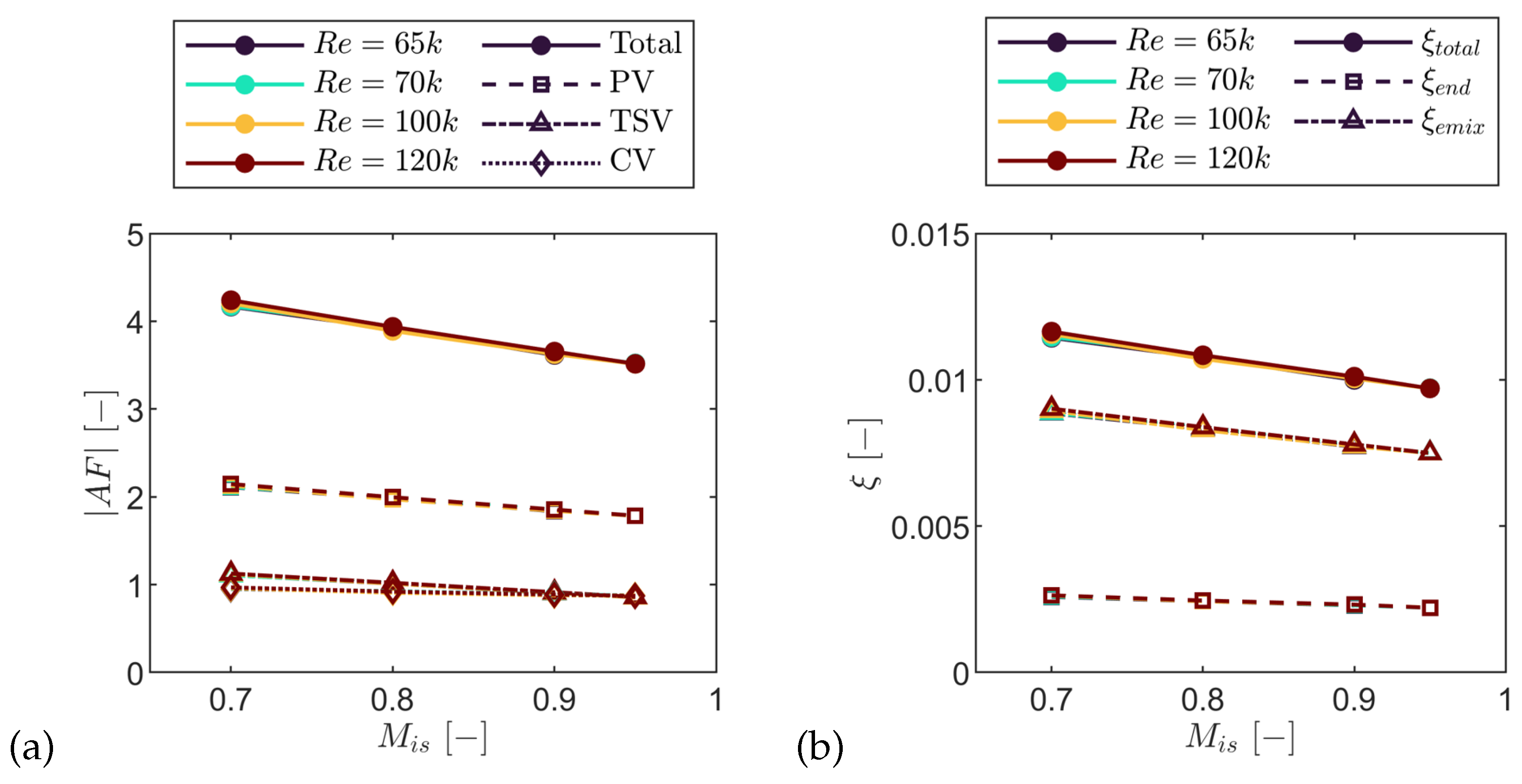

At the outlet, the secondary field comprised a passage vortex (PV), trailing shed vorticity (TSV), and a suction side corner vortex (CV). The spanwise secondary loss decreased with Mach number and Reynolds number and was of the profile loss. With increasing Mach number the PV + TSV peak (C1) fell by , peak underturning weakened by , and the dominant core reduced by . At , increasing the Reynolds number lowered the C1 peak of by while increasing the dominant core by .

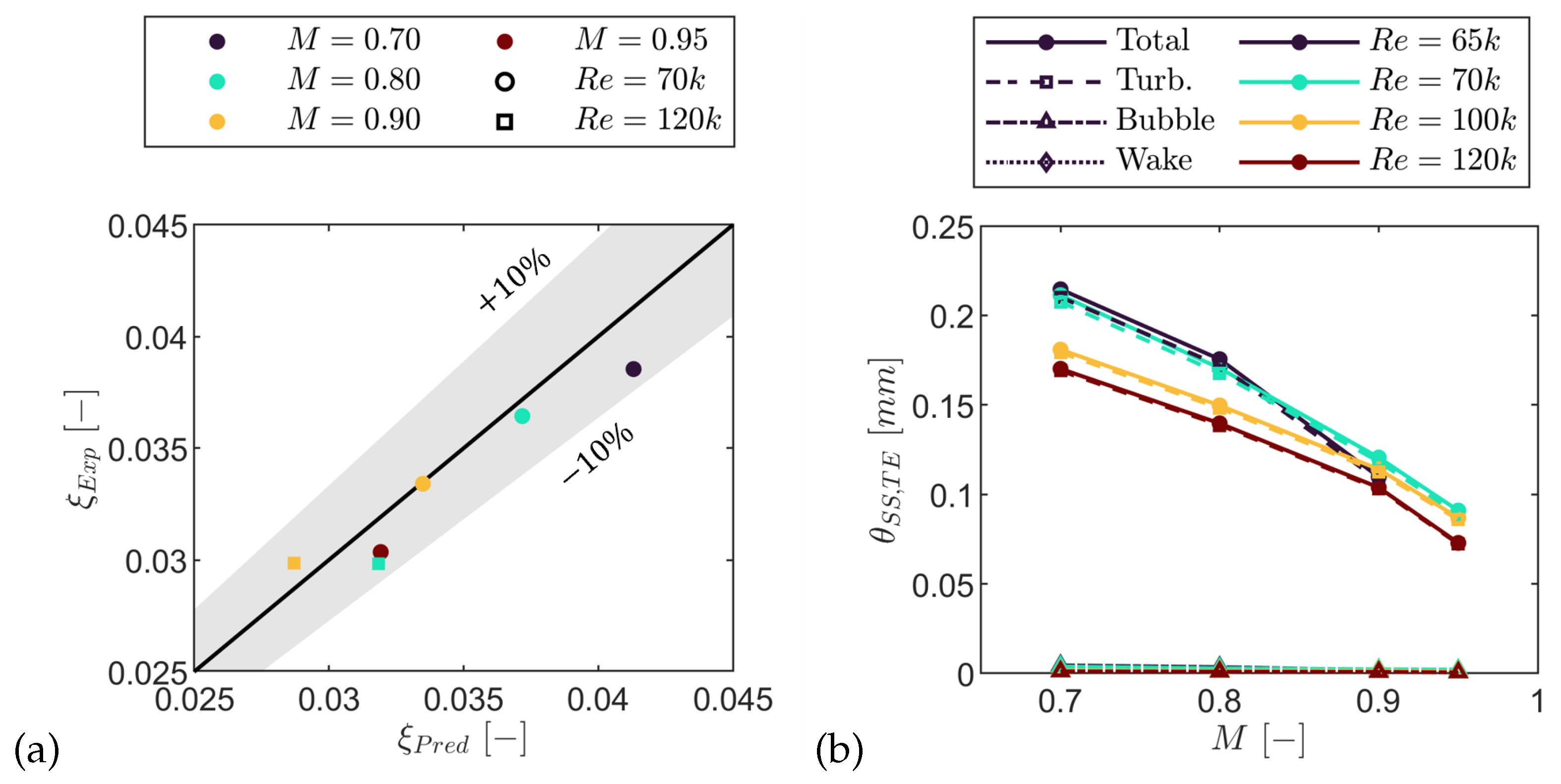

A profile-loss breakdown using Senior and Miller [

46] coupled to Coull and Hodson [

30] reproduced measured trends once separation was estimated with a Stratford-type criterion (

with leading-edge correction). Among Thwaites-type criteria, Pohlhausen yielded the lowest mean separation location error (

); Stratford

with the correction gave

and was more robust as Mach number increased. After calibration, the model matched the measured profile loss with an RMS error of

. Boundary layer mixing dominated the profile loss (up to

); within this term, turbulent growth downstream of separation contributed up to

, consistent with the thin bubble of the SPLEEN C1 loading. The blockage term rose with Mach number to

of profile loss at

. The wedge angle term was nearly invariant at

.

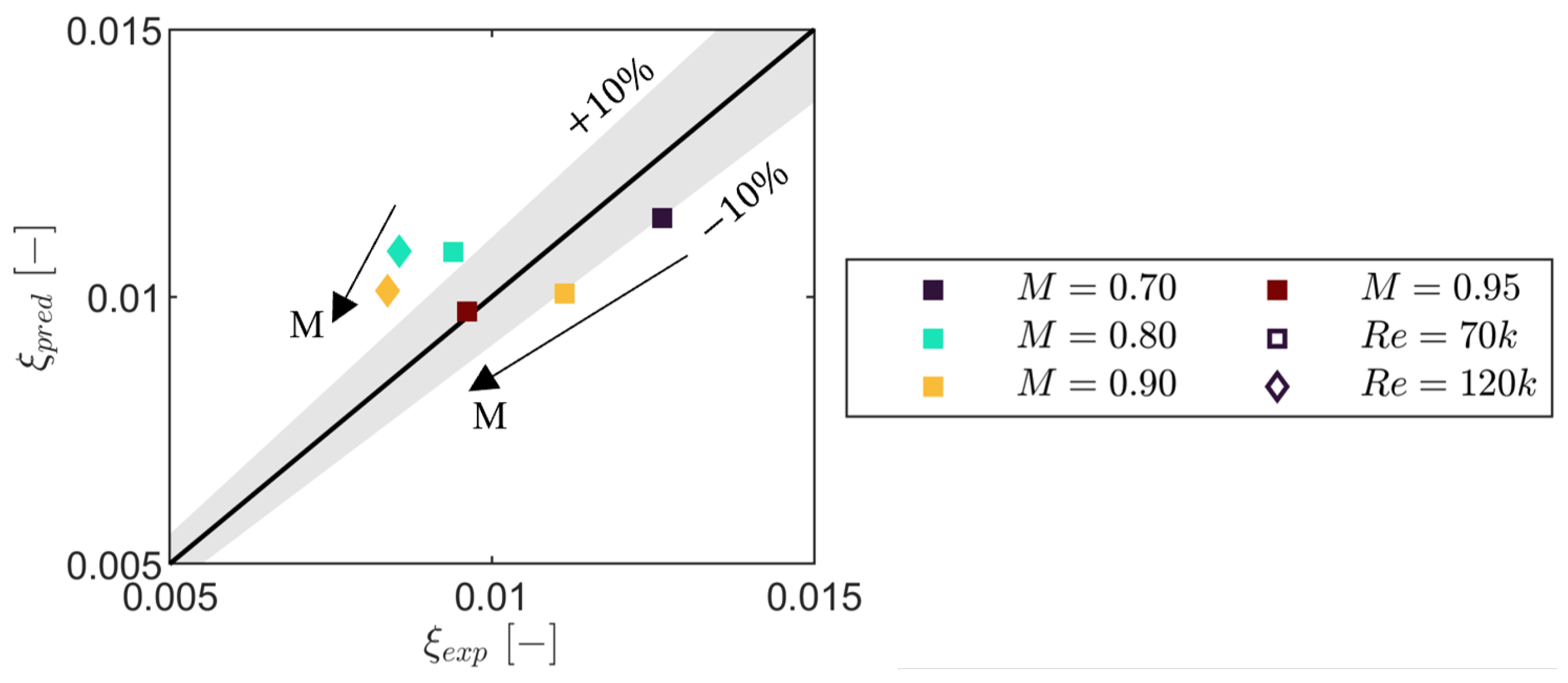

For secondary loss, Coull’s vorticity-amplification model [

34] captured the Mach number trend and was within

for most conditions, overpredicting at higher Reynolds numbers. Using a potential (fully turbulent MISES) midspan field to estimate endwall dissipation altered the dissipation integral by

relative to endwall data, but this corresponds to only

absolute loss (

of the expected endwall contribution), indicating that the inviscid approach is adequate for the present scope. The PV contributed

of the secondary mixing loss; at

, TSV and CV accounted for

and

, becoming comparable at higher Mach numbers. The Coull–Clark model [

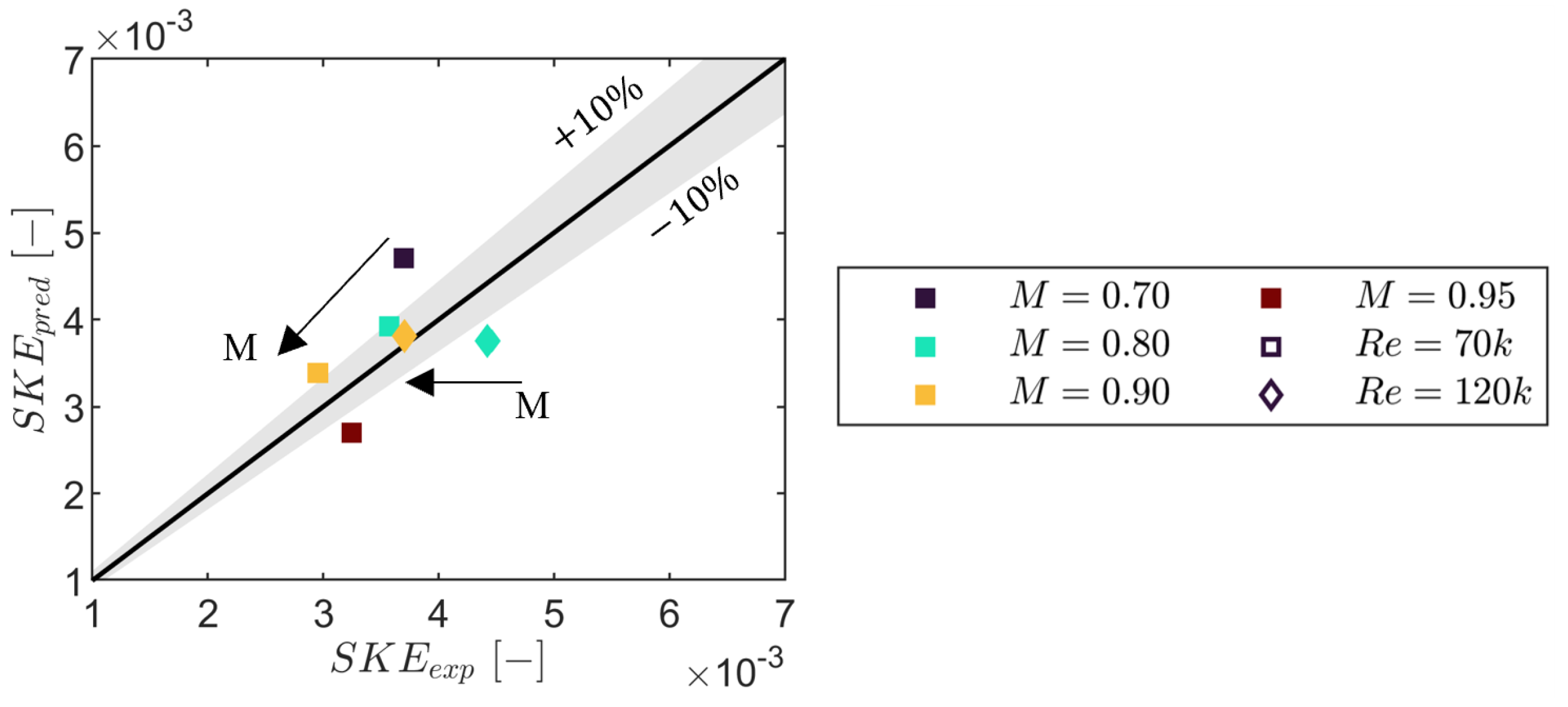

57] predicted secondary kinetic energy within

for most cases, with larger deviations at the lowest and highest Mach numbers at

and at

,

.

Coull and Clark [

57], which uses inlet boundary layer thickness and shape factor rather than a kinetic energy deficit, provides secondary kinetic energy predictions within

for most cases, with larger discrepancies at the lowest and highest Mach numbers at

and at

,

. Its simplicity and general accuracy make it attractive for design studies.

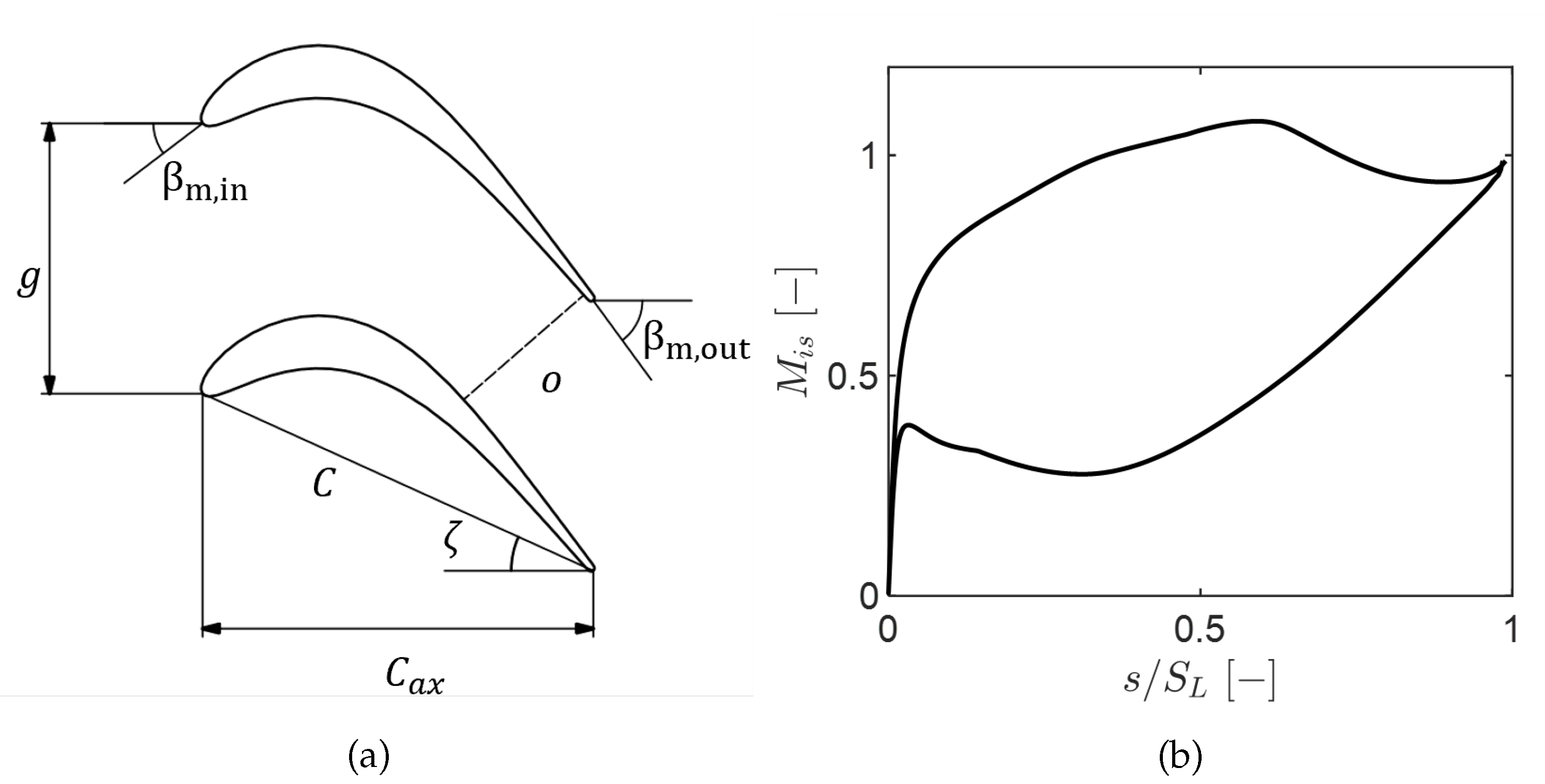

Figure 1.

SPLEEN C1 geometry (a) and blade loading at the design point (b).

Figure 1.

SPLEEN C1 geometry (a) and blade loading at the design point (b).

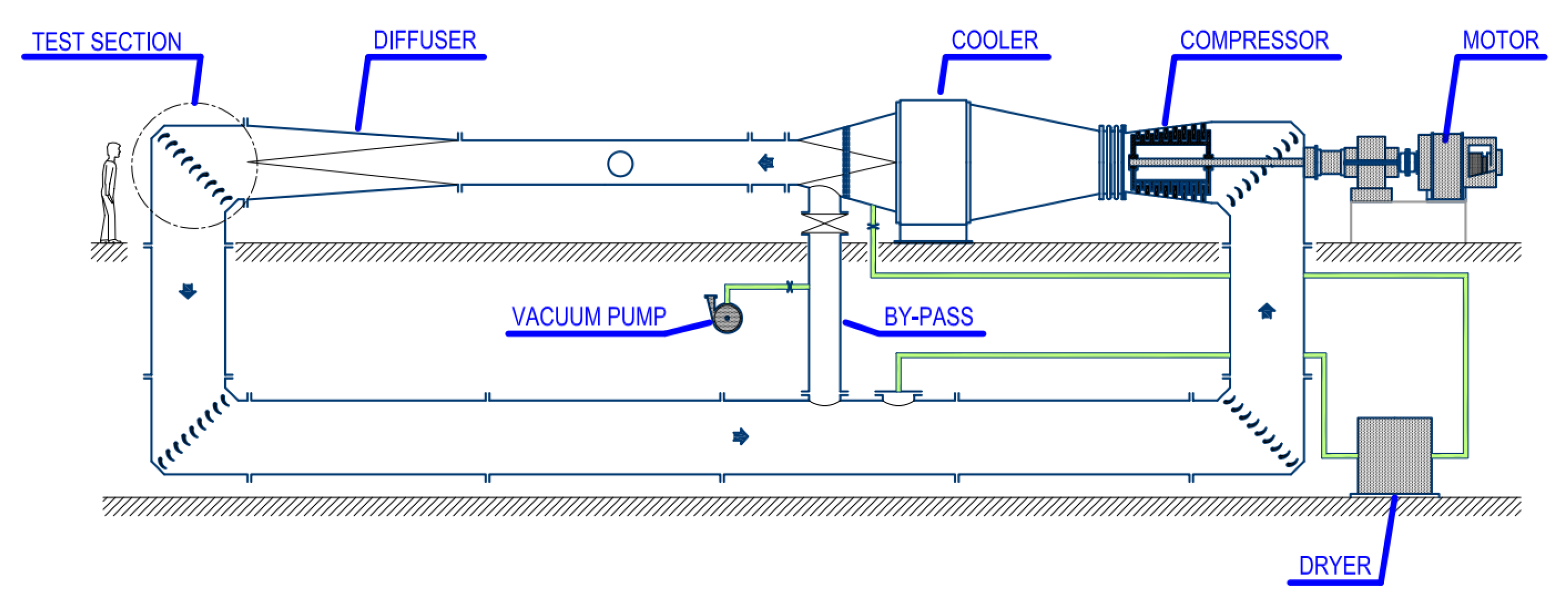

Figure 2.

The VKI S-1/C wind tunnel.

Figure 2.

The VKI S-1/C wind tunnel.

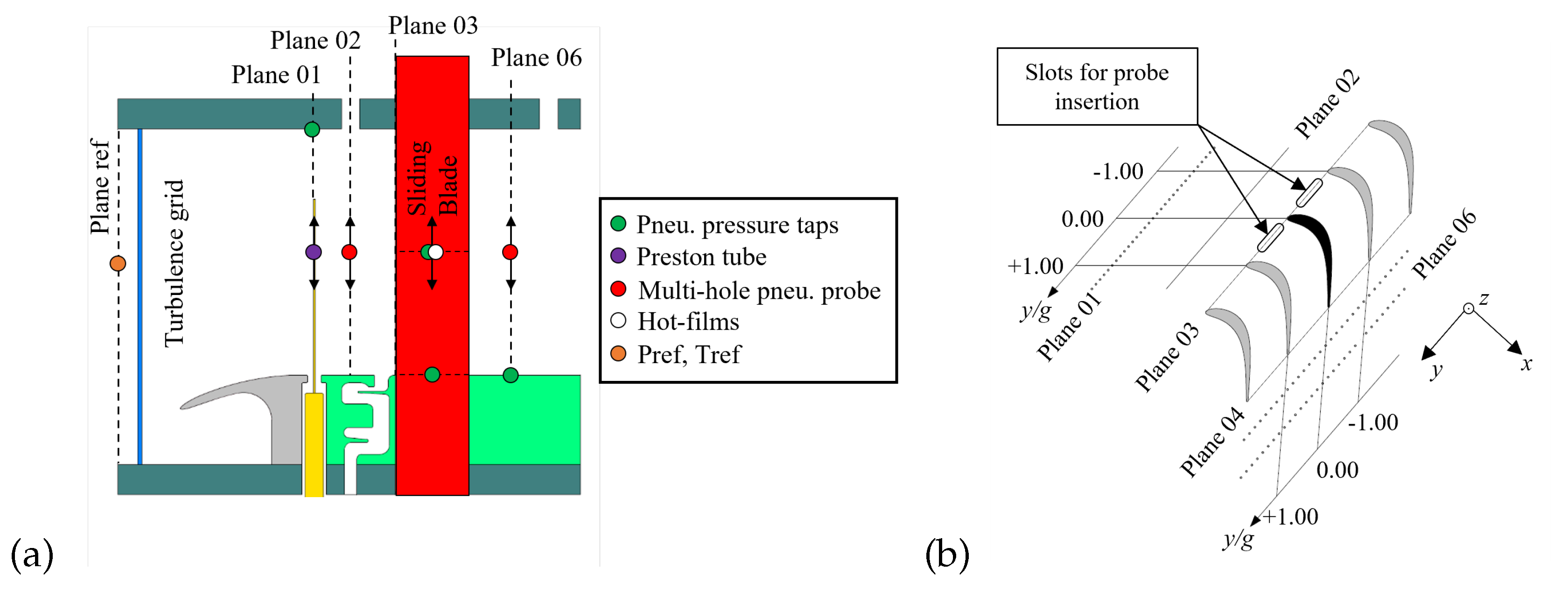

Figure 3.

Test section layout and instrumentation (a) and Blade-to-blade view (b).

Figure 3.

Test section layout and instrumentation (a) and Blade-to-blade view (b).

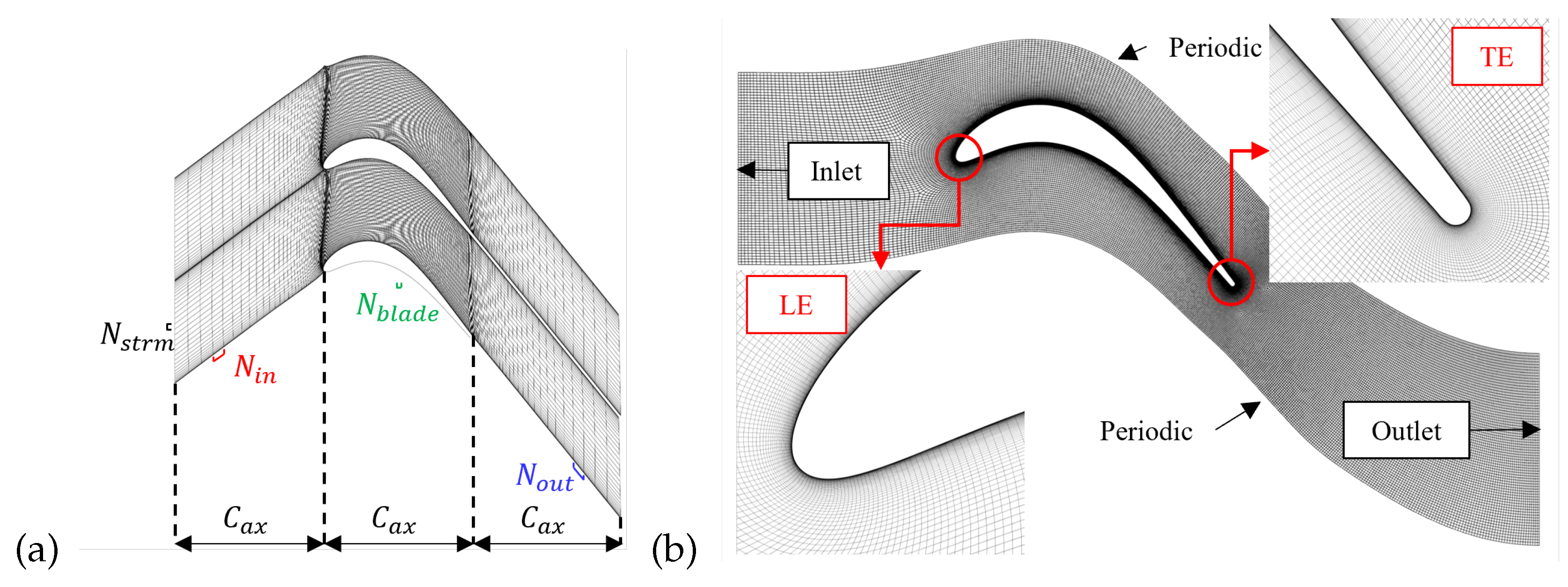

Figure 4.

Final meshes for MISES (a) and RANS (b).

Figure 4.

Final meshes for MISES (a) and RANS (b).

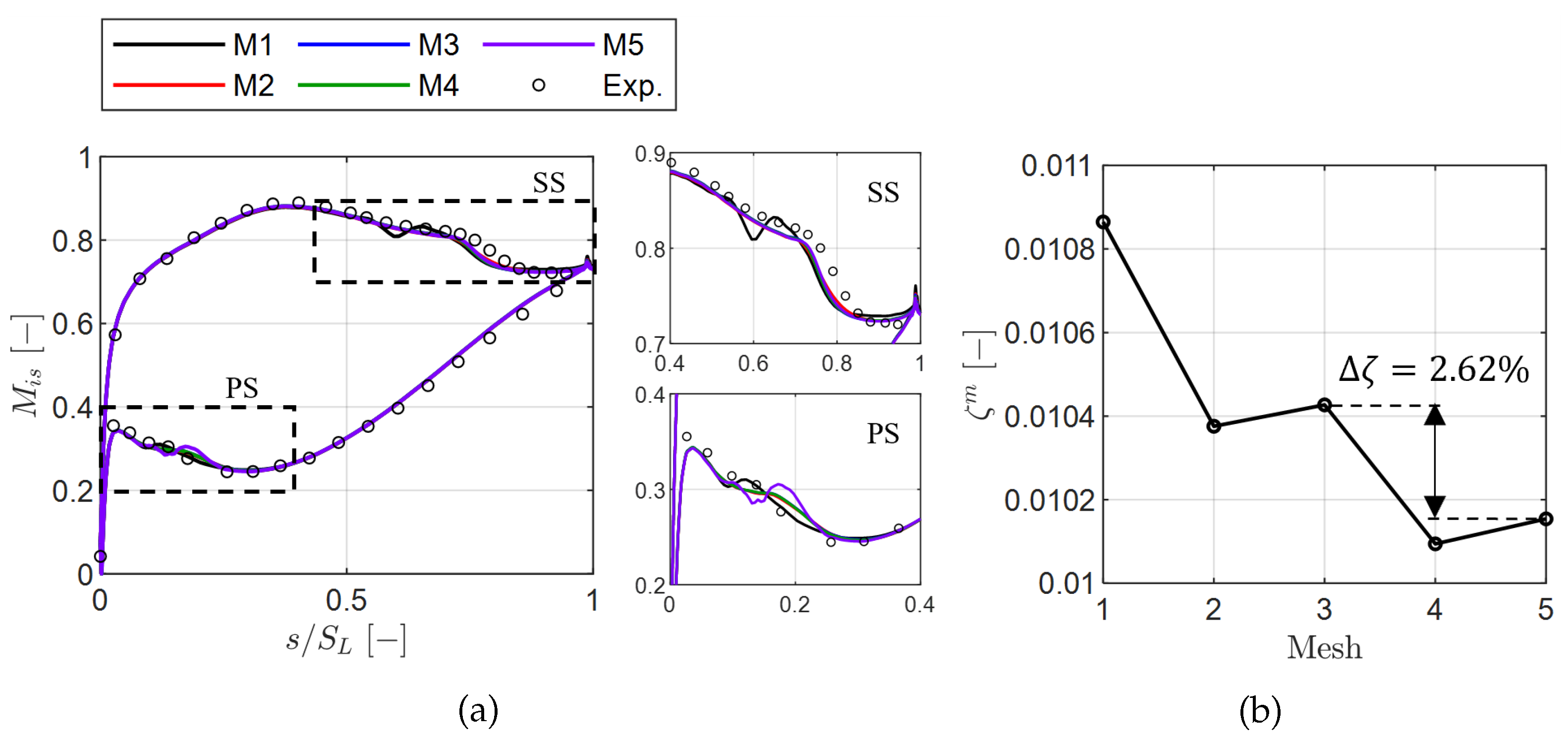

Figure 5.

RANS mesh sensitivity for and . (a) Surface isentropic Mach number along normalized surface length. (b) Mass-averaged total-pressure loss coefficient.

Figure 5.

RANS mesh sensitivity for and . (a) Surface isentropic Mach number along normalized surface length. (b) Mass-averaged total-pressure loss coefficient.

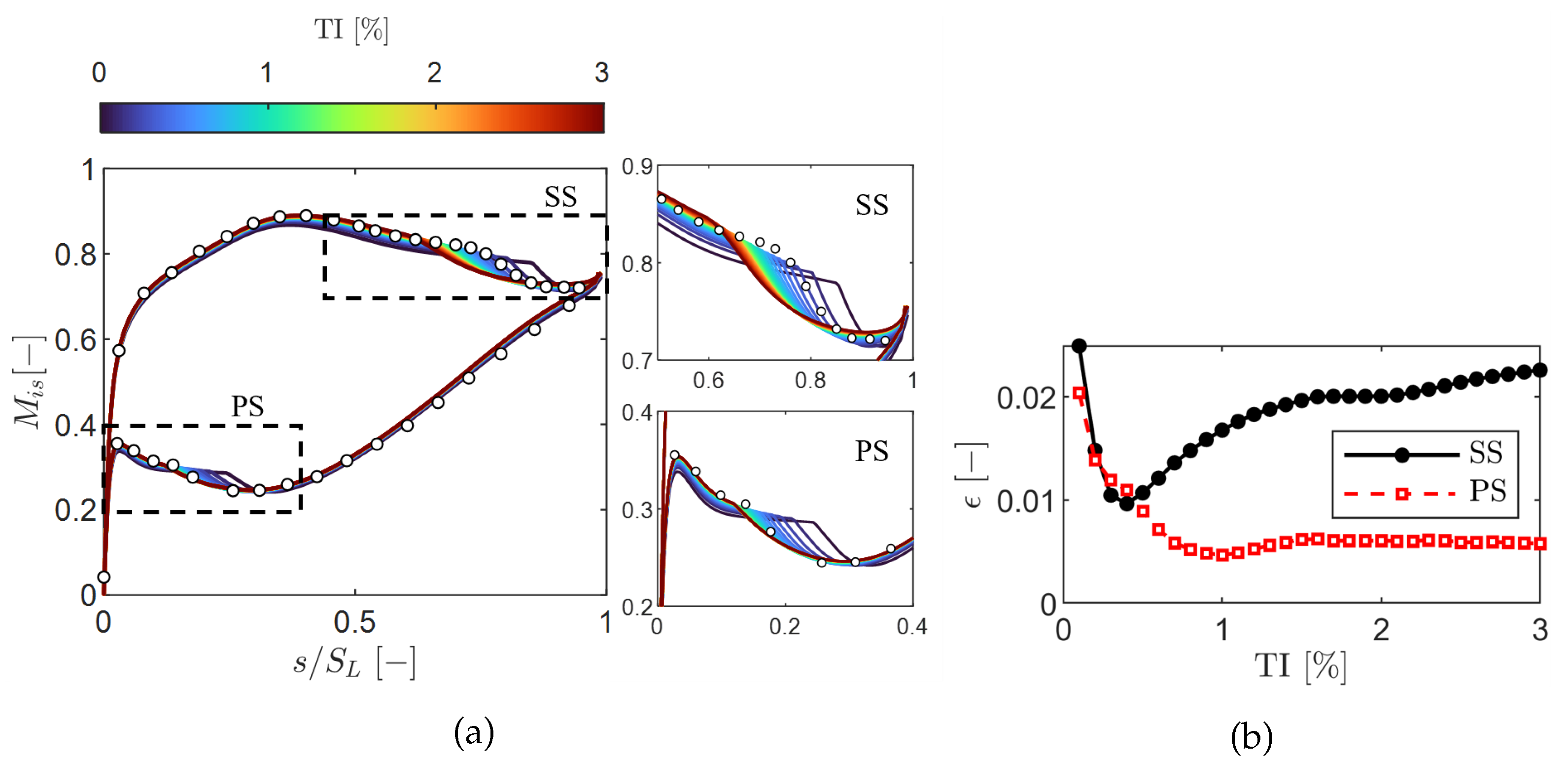

Figure 6.

Sensitivity to turbulence intensity. (a) Surface isentropic Mach number along the normalized surface length. (b) Relative error between MISES and experiments.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity to turbulence intensity. (a) Surface isentropic Mach number along the normalized surface length. (b) Relative error between MISES and experiments.

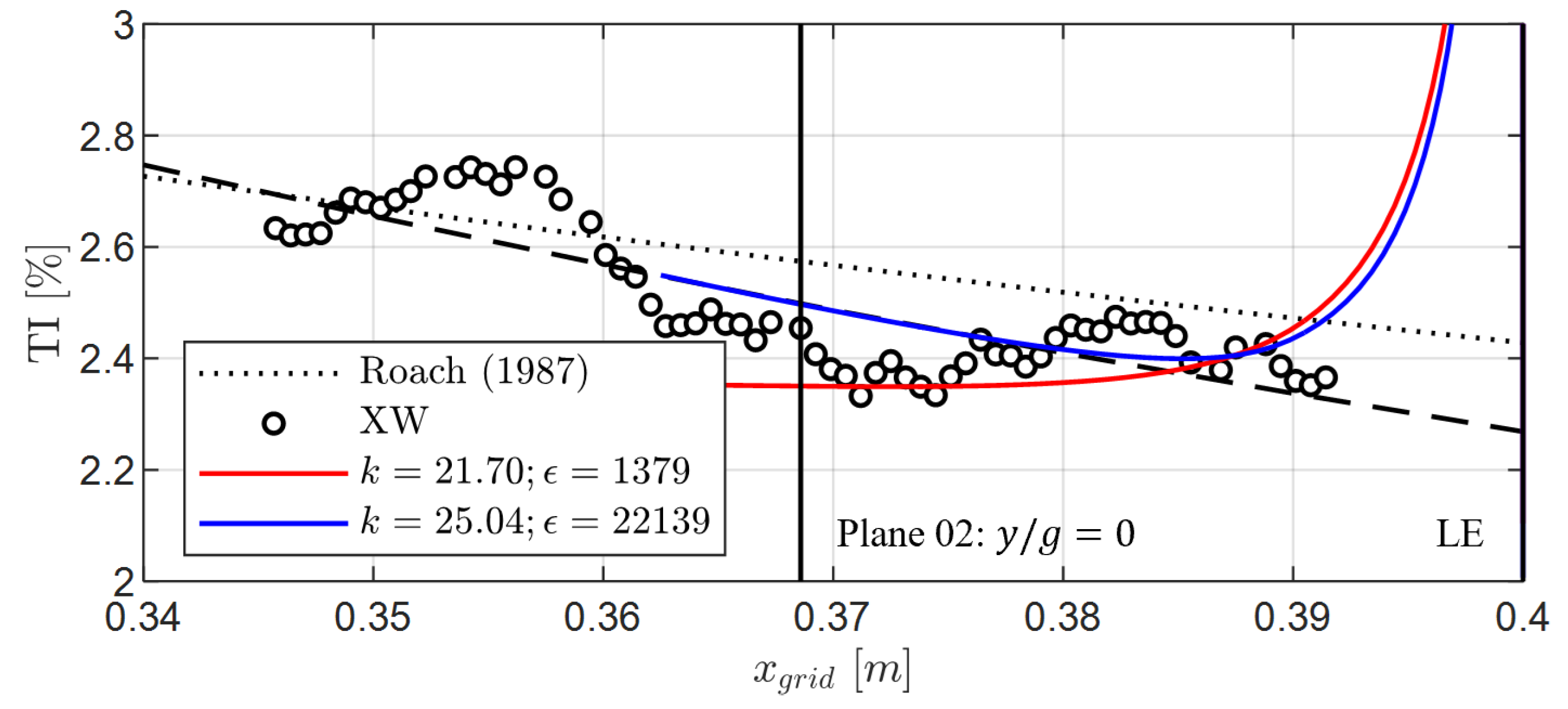

Figure 7.

RANS inlet turbulence decay tuned to cross-wire data and compared with the Roach correlation.

Figure 7.

RANS inlet turbulence decay tuned to cross-wire data and compared with the Roach correlation.

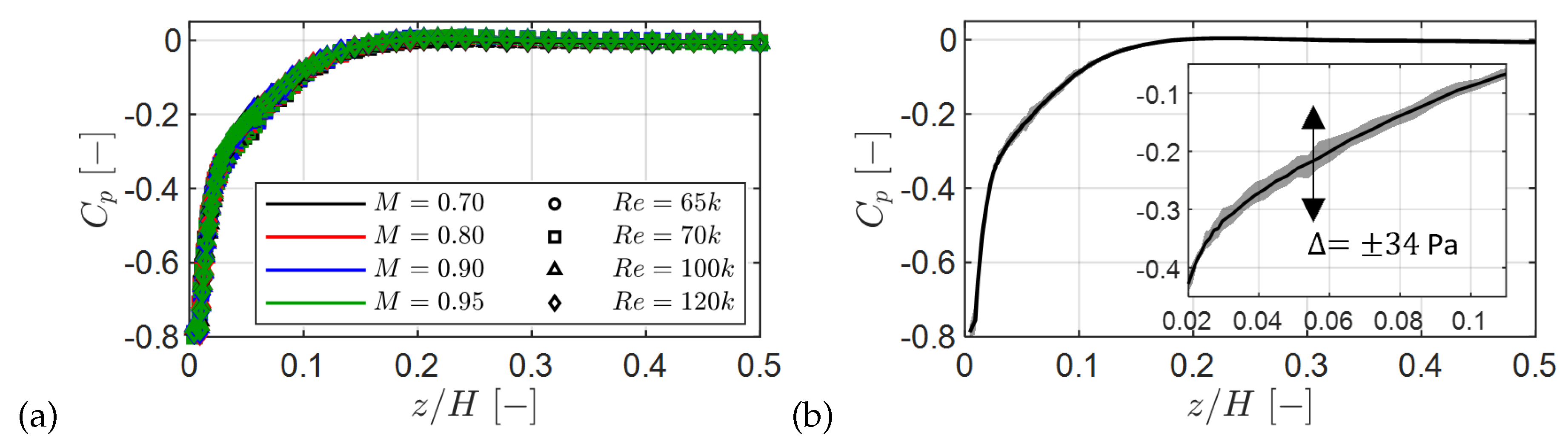

Figure 8.

Inlet boundary layer at Plane 01. (a) Spanwise for all conditions. (b) Spanwise mean with range (shaded).

Figure 8.

Inlet boundary layer at Plane 01. (a) Spanwise for all conditions. (b) Spanwise mean with range (shaded).

Figure 9.

Inlet boundary layer integral parameters versus operating point. (a) Displacement thickness. (b) Momentum thickness. (c) Shape factor.

Figure 9.

Inlet boundary layer integral parameters versus operating point. (a) Displacement thickness. (b) Momentum thickness. (c) Shape factor.

Figure 10.

Midspan inlet flow at Plane 02: (a) incidence, (b) cascade pitch angle, (c) normalized Mach number.

Figure 10.

Midspan inlet flow at Plane 02: (a) incidence, (b) cascade pitch angle, (c) normalized Mach number.

Figure 11.

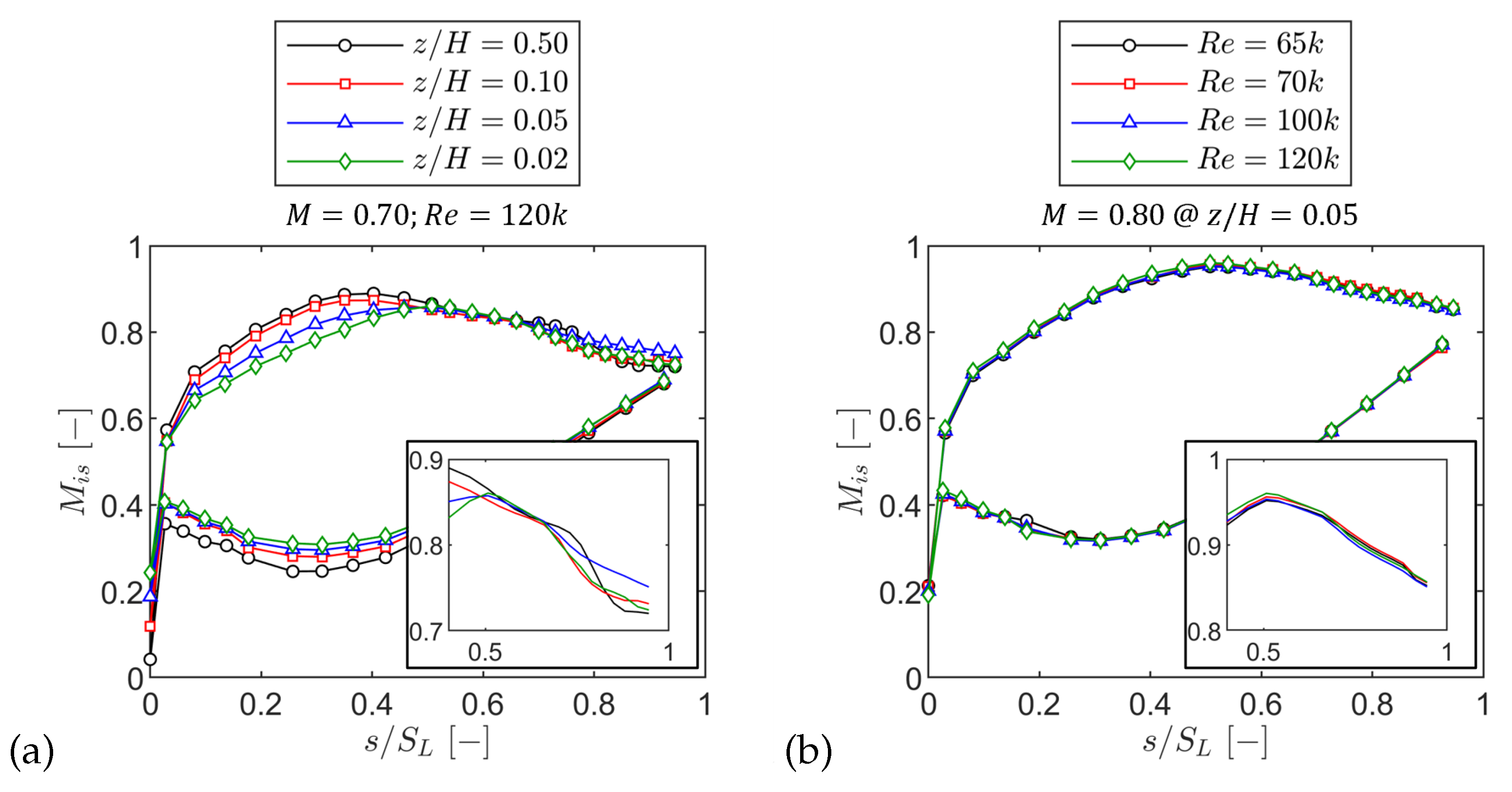

Blade loading: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). (a), (b), (c), (d).

Figure 11.

Blade loading: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). (a), (b), (c), (d).

Figure 12.

Suction side close-up: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). (a), (b), (c), (d).

Figure 12.

Suction side close-up: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). (a), (b), (c), (d).

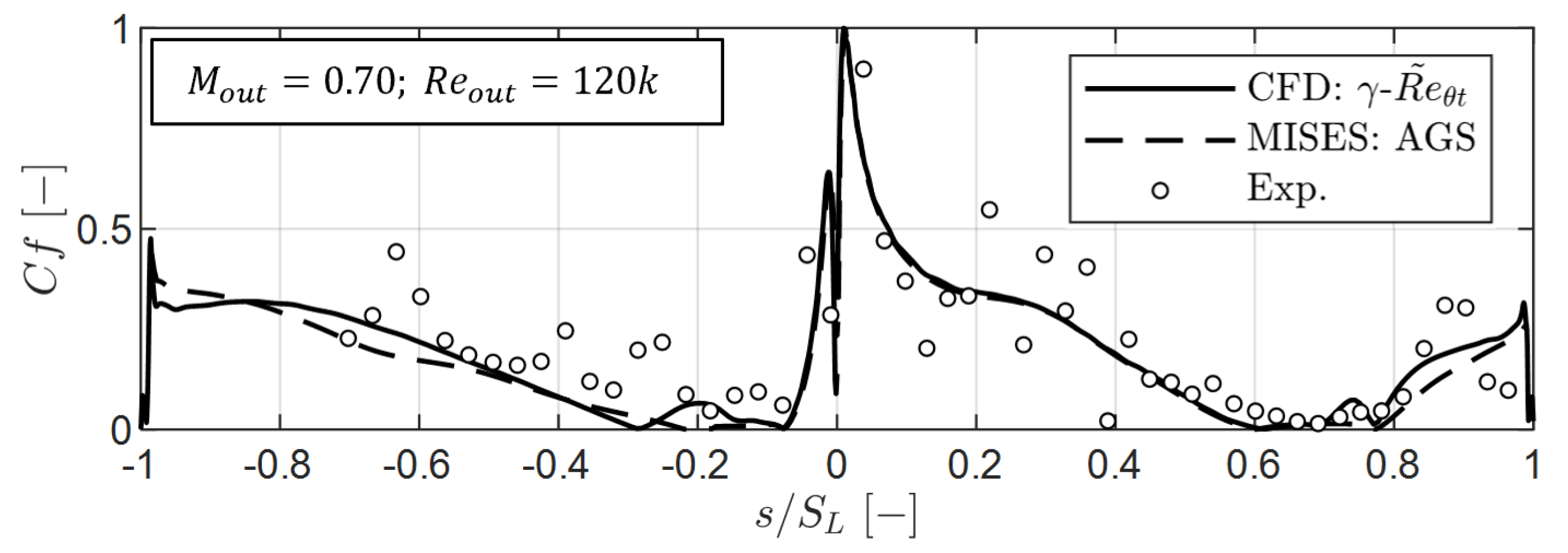

Figure 13.

Blade quasi-wall shear stress: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). Negative values are relative to the pressure side.

Figure 13.

Blade quasi-wall shear stress: experimental (markers), CFD (solid), and MISES AGS (dashed). Negative values are relative to the pressure side.

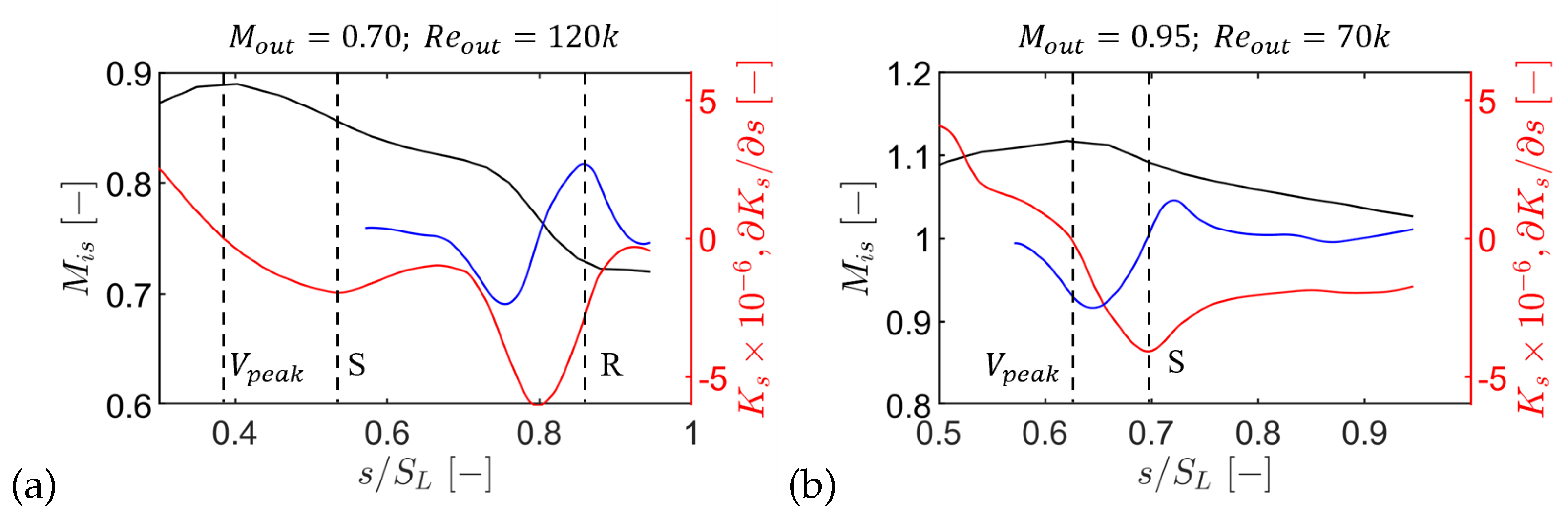

Figure 14.

Suction side (black, left axis), acceleration parameter (red, right axis), and scaled (blue, right axis). (a) and (b).

Figure 14.

Suction side (black, left axis), acceleration parameter (red, right axis), and scaled (blue, right axis). (a) and (b).

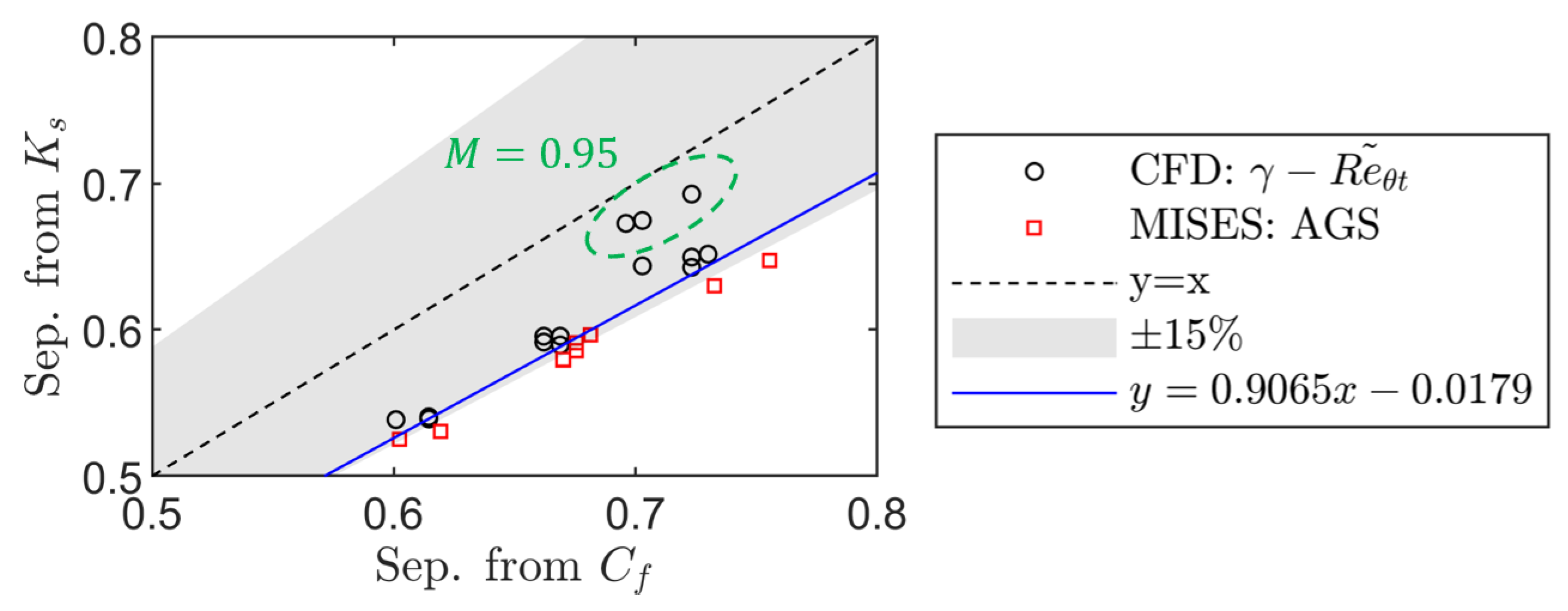

Figure 15.

Separation location from skin friction versus from the method. The shaded band indicates about the line.

Figure 15.

Separation location from skin friction versus from the method. The shaded band indicates about the line.

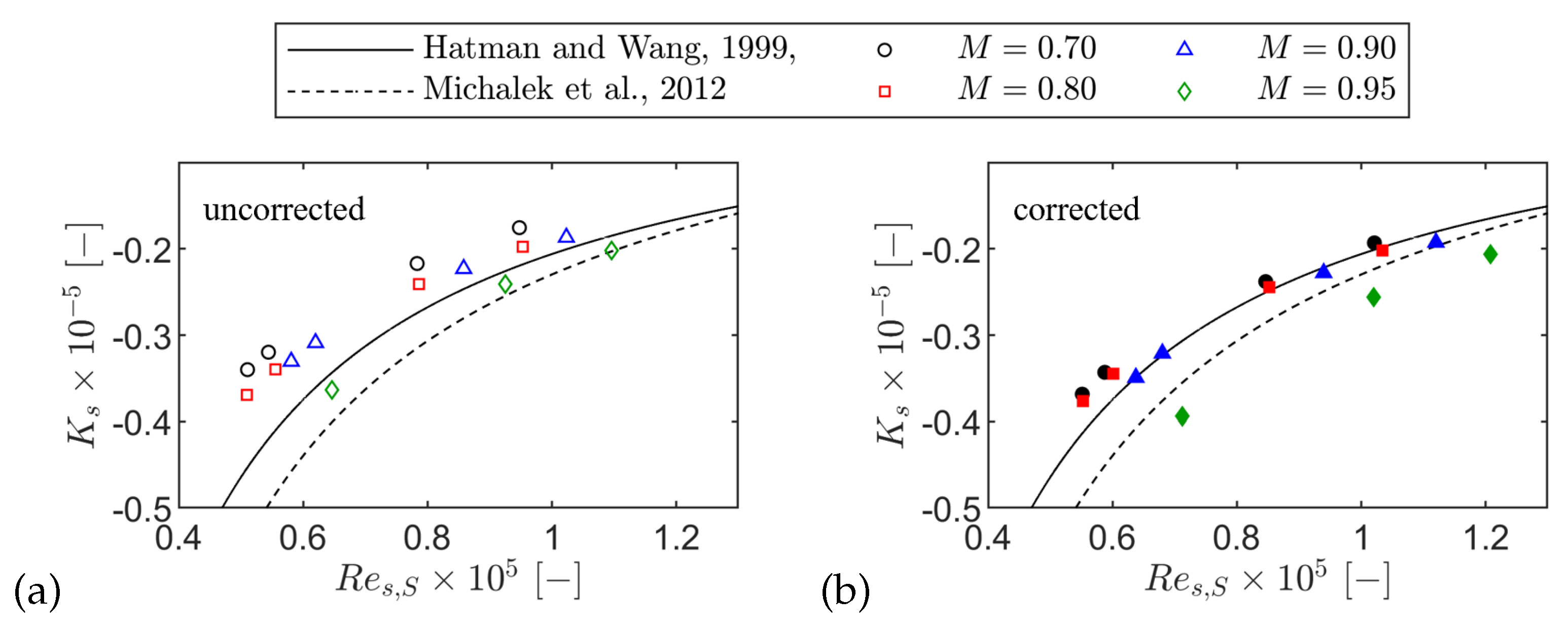

Figure 16.

Acceleration parameter at separation versus surface-length-based Reynolds number: without correction (a) and with separation-location correction (b).

Figure 16.

Acceleration parameter at separation versus surface-length-based Reynolds number: without correction (a) and with separation-location correction (b).

Figure 17.

Surface-length-based Reynolds number at reattachment versus at separation.

Figure 17.

Surface-length-based Reynolds number at reattachment versus at separation.

Figure 18.

Spanwise variation of blade loading: (a) and sensitivity of near-wall loading at to Reynolds number at (b).

Figure 18.

Spanwise variation of blade loading: (a) and sensitivity of near-wall loading at to Reynolds number at (b).

Figure 19.

Pitchwise distribution of kinetic energy loss coefficient: Re=70k (a) and Re=120k (b).

Figure 19.

Pitchwise distribution of kinetic energy loss coefficient: Re=70k (a) and Re=120k (b).

Figure 20.

Mass-averaged profile loss in terms of kinetic energy loss coefficient.

Figure 20.

Mass-averaged profile loss in terms of kinetic energy loss coefficient.

Figure 21.

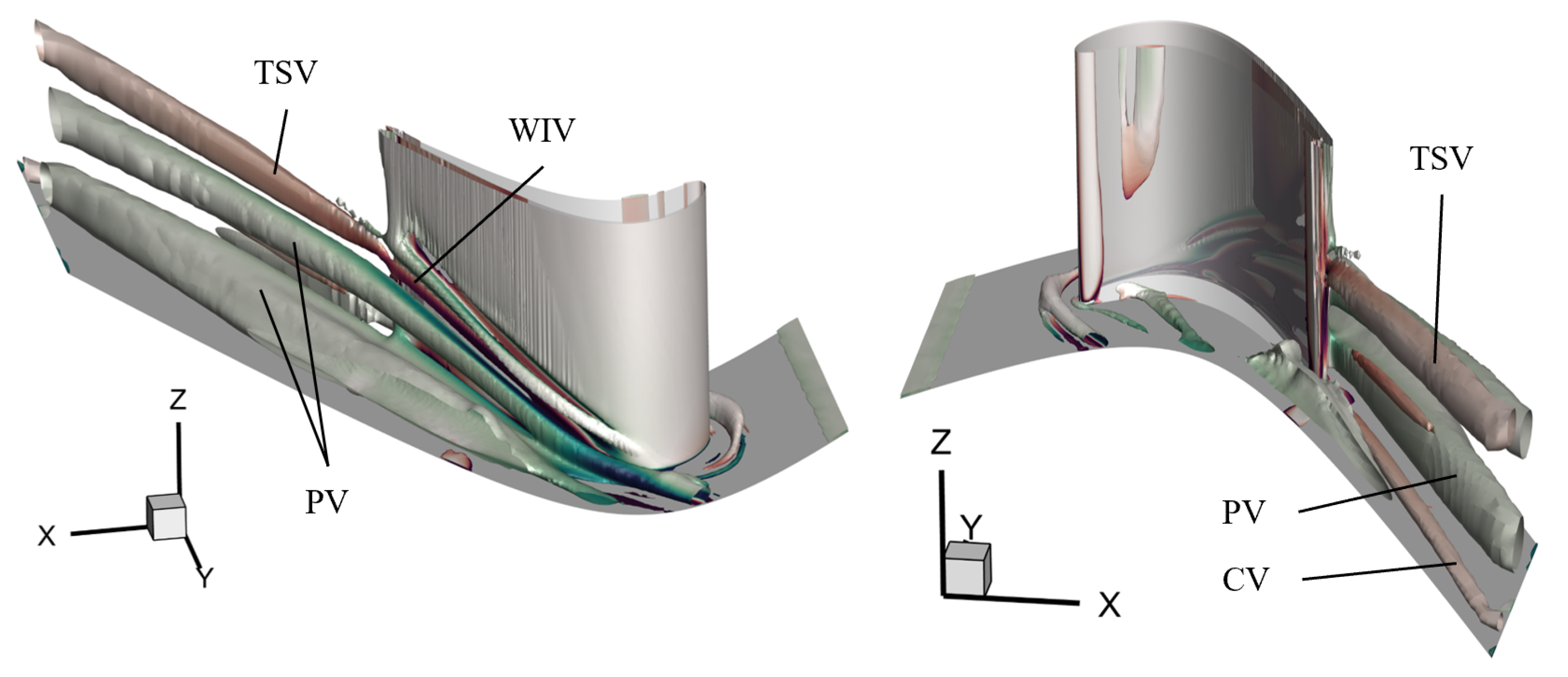

Representation of primary and secondary flow structures with Q-criterion.

Figure 21.

Representation of primary and secondary flow structures with Q-criterion.

Figure 22.

Secondary flow structures at Plane 06 for nominal flow case: kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), streamwise vorticity coefficient superimposed with isolines of kinetic energy loss coefficient (b) and secondary kinetic energy coefficient superimposed with secondary velocity vectors (c). The observer looks upstream.

Figure 22.

Secondary flow structures at Plane 06 for nominal flow case: kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), streamwise vorticity coefficient superimposed with isolines of kinetic energy loss coefficient (b) and secondary kinetic energy coefficient superimposed with secondary velocity vectors (c). The observer looks upstream.

Figure 23.

Impact of Mach number at a Reynolds number of 70,000: M=0.70 (a), M=0.90 (b) and M=0.95 (c).

Figure 23.

Impact of Mach number at a Reynolds number of 70,000: M=0.70 (a), M=0.90 (b) and M=0.95 (c).

Figure 24.

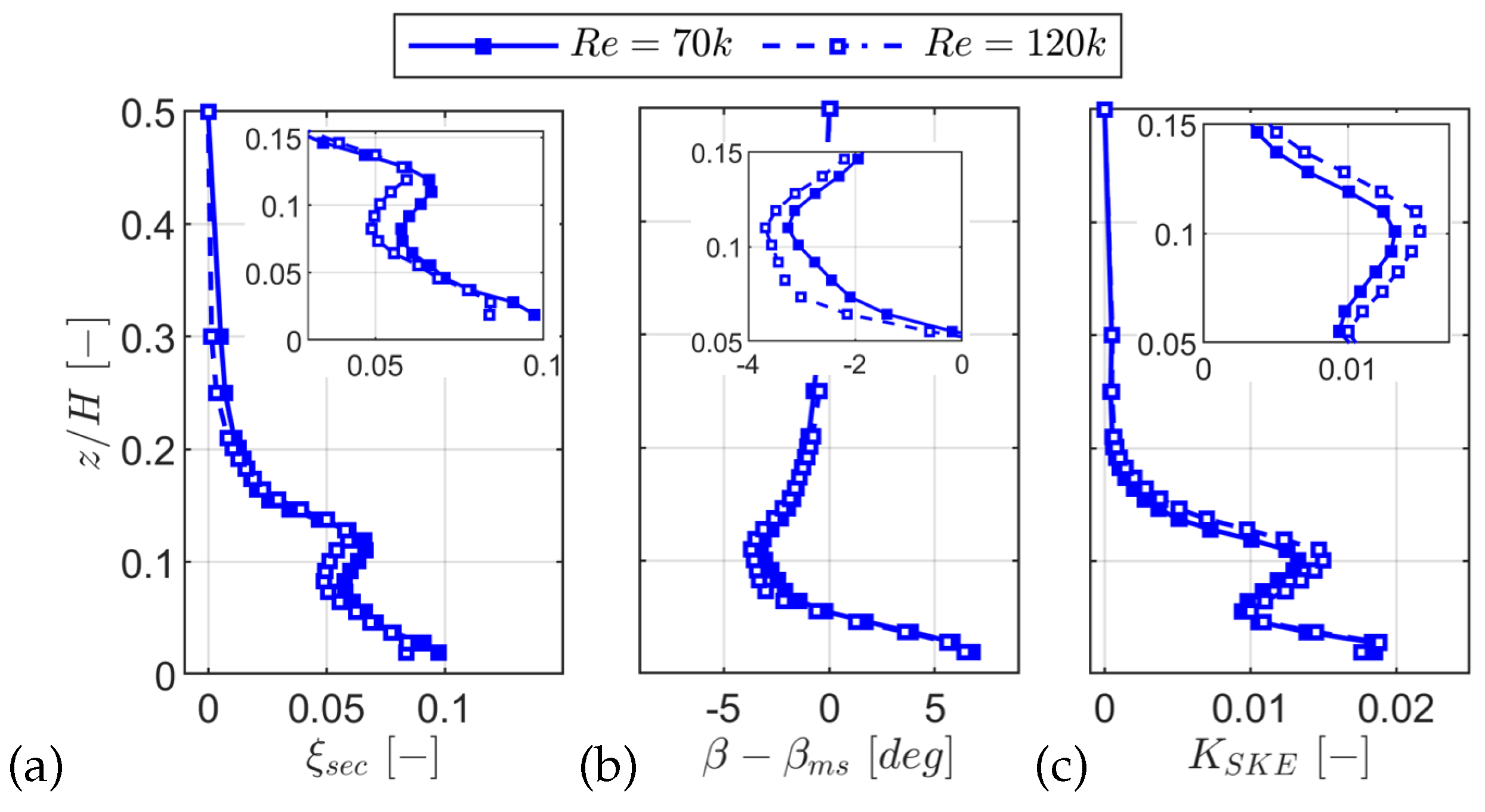

Radial profiles for Re=70k: secondary kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), deviation from primary flow direction (b), and secondary kinetic energy coefficient (c).

Figure 24.

Radial profiles for Re=70k: secondary kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), deviation from primary flow direction (b), and secondary kinetic energy coefficient (c).

Figure 25.

Radial profiles for M=0.90: secondary kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), deviation from primary flow direction (b), and secondary kinetic energy coefficient (c).

Figure 25.

Radial profiles for M=0.90: secondary kinetic energy loss coefficient (a), deviation from primary flow direction (b), and secondary kinetic energy coefficient (c).

Figure 26.

Breakdown of the planewise mass-averaged losses for the steady inlet flow cases.

Figure 26.

Breakdown of the planewise mass-averaged losses for the steady inlet flow cases.

Figure 27.

Comparison of experimentally obtained separation locations against those estimated with different methods: Thwaites (a) and Stratford (b).

Figure 27.

Comparison of experimentally obtained separation locations against those estimated with different methods: Thwaites (a) and Stratford (b).

Figure 28.

Comparison of experimentally obtained separation location against the one estimated with the best method of the Thwaites and Stratford type methods.

Figure 28.

Comparison of experimentally obtained separation location against the one estimated with the best method of the Thwaites and Stratford type methods.

Figure 29.

Loss breakdown by flow condition (a), and contributions of BL on SS (b) for steady inlet flow cases.

Figure 29.

Loss breakdown by flow condition (a), and contributions of BL on SS (b) for steady inlet flow cases.

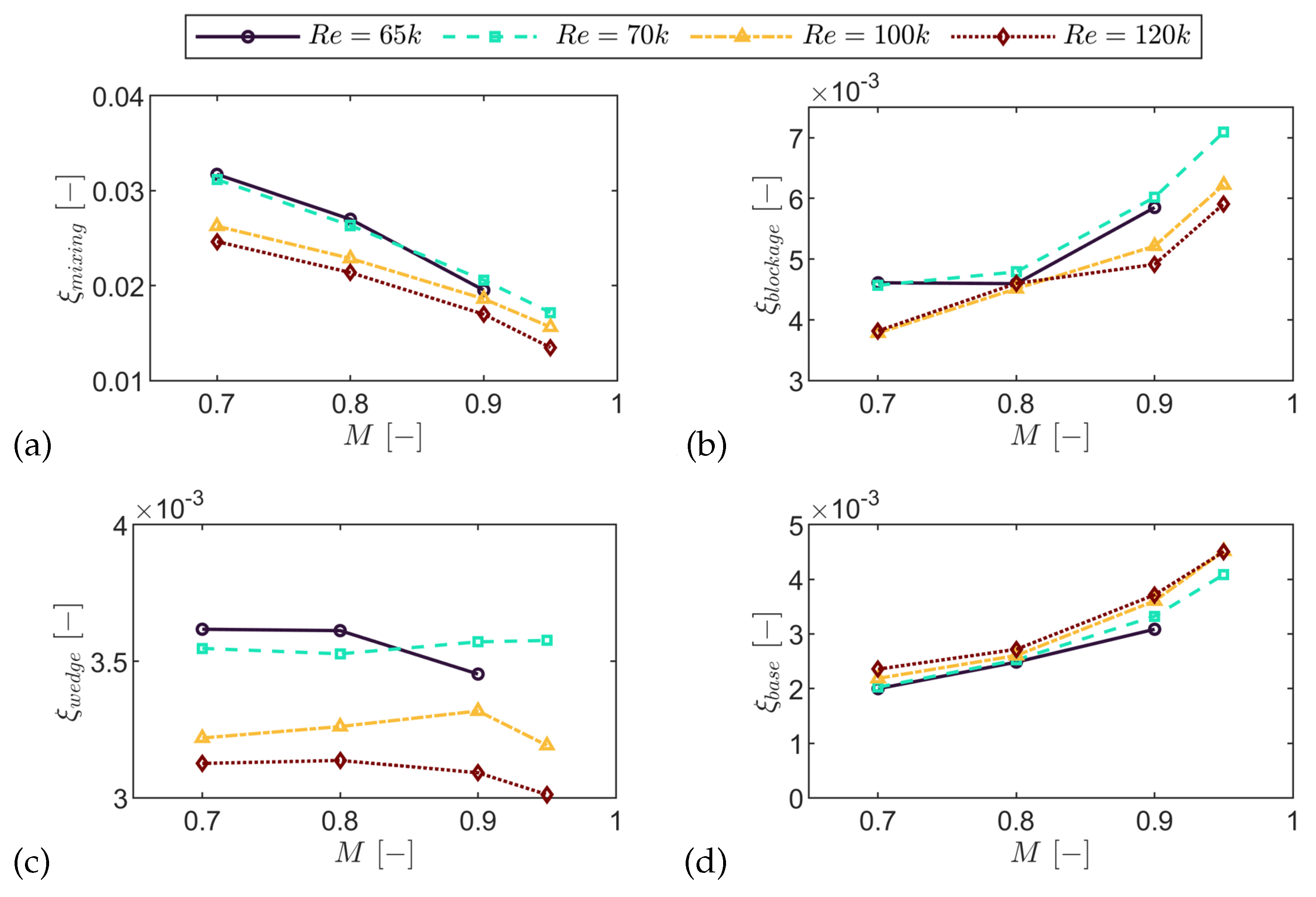

Figure 30.

Breakdown of loss contributions of profile loss from Equation

16–Equation

19: mixing loss

(a), blockage loss

(b), trailing edge wedge angle loss

(c), and base pressure loss

(d).

Figure 30.

Breakdown of loss contributions of profile loss from Equation

16–Equation

19: mixing loss

(a), blockage loss

(b), trailing edge wedge angle loss

(c), and base pressure loss

(d).

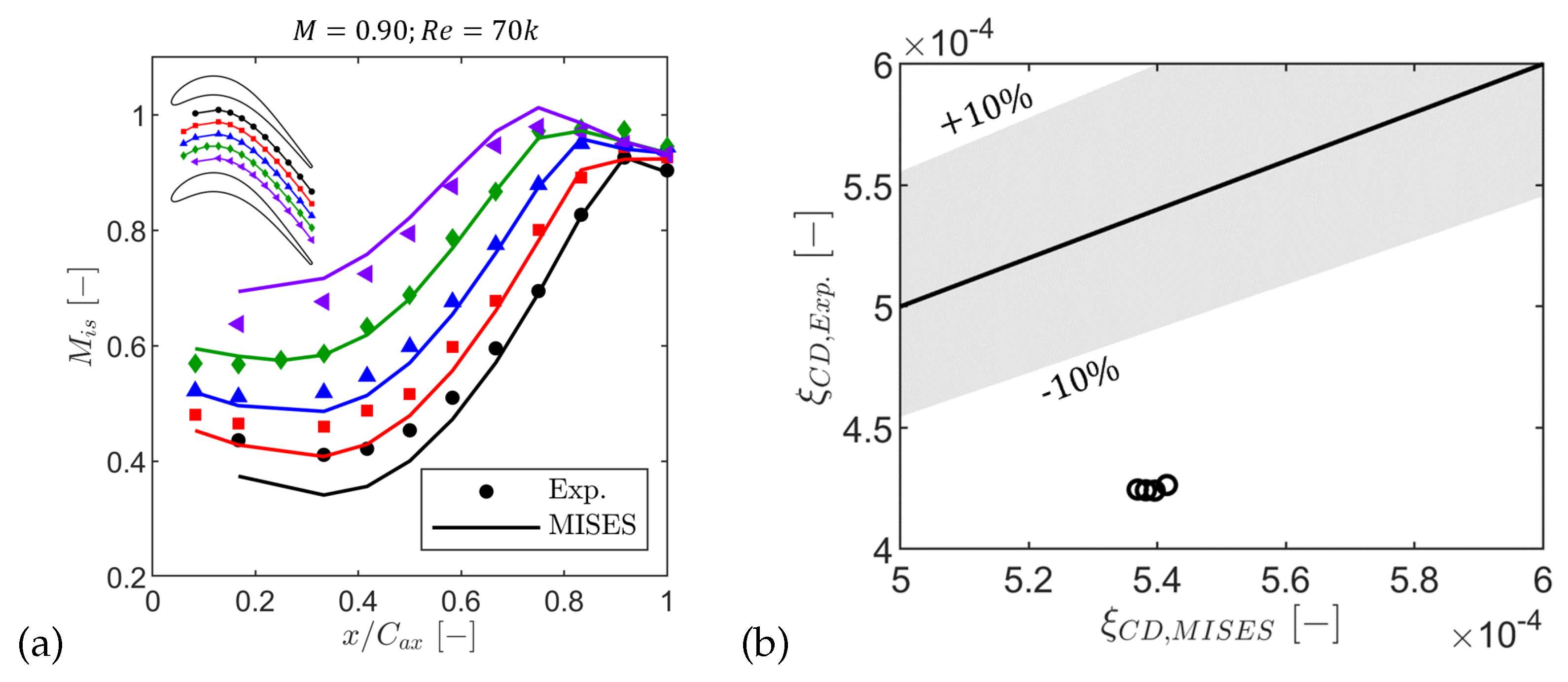

Figure 31.

Isentropic Mach number along the normalized axial direction (a) and endwall-loss integral using experimental versus MISES inputs (b). The loss integral is evaluated over the experimentally delimited area.

Figure 31.

Isentropic Mach number along the normalized axial direction (a) and endwall-loss integral using experimental versus MISES inputs (b). The loss integral is evaluated over the experimentally delimited area.

Figure 32.

Sensitivity of endwall loss to the Mach number and the Reynolds number using the model of Coull [

34].

Figure 32.

Sensitivity of endwall loss to the Mach number and the Reynolds number using the model of Coull [

34].

Figure 33.

Breakdown by secondary structure (a) and decomposition into endwall dissipation and mixing (b) for steady-flow cases.

Figure 33.

Breakdown by secondary structure (a) and decomposition into endwall dissipation and mixing (b) for steady-flow cases.

Figure 34.

Sensitivity of secondary kinetic energy to Mach and Reynolds numbers using the model of Coull [

57].

Figure 34.

Sensitivity of secondary kinetic energy to Mach and Reynolds numbers using the model of Coull [

57].

Table 1.

SPLEEN C1 cascade key geometrical features.

Table 1.

SPLEEN C1 cascade key geometrical features.

| True chord, C

|

52.285 |

[] |

| Axial chord,

|

47.614 |

[] |

| Pitch-to-chord ratio,

|

0.630 |

[−] |

| Cascade span, H

|

165 |

[] |

| TE thickness,

|

0.86 |

[] |

| TE radius/C

|

0.0082 |

[−] |

| TE wedge angle |

4.96 |

[∘] |

| Throat, o

|

19.400 |

[] |

| Inlet metal angle,

|

37.30 |

[∘] |

| Outlet metal angle,

|

53.80 |

[∘] |

| Stagger angle,

|

24.40 |

[∘] |

| Diffusion factor, DF |

18 |

[%] |

| Circulation coefficient, C0

|

0.61 |

[−] |

| Zweifel coefficient,

|

0.73 |

[−] |

Table 2.

Breakdown of experimental uncertainty with 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Breakdown of experimental uncertainty with 95% confidence interval.

| Instrument |

Qt. |

Unit |

|

|

| Fixed |

|

K |

0.01 |

0.52 |

| |

|

Pa |

7.01 |

29.82 |

| Blade pneu./Endwall pneu. |

|

− |

0.001 |

0.005 |

| Preston tube |

|

− |

0.001 |

0.008 |

| C5HP |

|

∘

|

0.31 |

0.98 |

| |

M |

− |

0.002 |

0.010 |

| L5HP |

-

|

∘

|

0.15 |

0.33 |

| |

|

− |

0.002 |

0.010 |

Table 3.

Instrumentation by operating condition. AP: aerodynamic probes. BP: blade pneumatic taps. EP: endwall pneumatic taps. HF: hot films.

Table 3.

Instrumentation by operating condition. AP: aerodynamic probes. BP: blade pneumatic taps. EP: endwall pneumatic taps. HF: hot films.

| |

|

|

| |

|

0.70 |

0.80 |

0.90 |

0.95 |

|

65,000 |

BP/EP |

BP |

BP/EP |

BP |

| |

70,000 |

AP/BP/HF |

AP/BP |

AP/BP/HF/EP |

AP/BP/HF/EP |

| |

100,000 |

BP |

BP |

BP/EP |

BP/EP |

| |

120,000 |

BP/HF |

AP/BP |

AP/BP/HF/EP |

BP |

Table 4.

Mesh parameters for MISES computations.

Table 4.

Mesh parameters for MISES computations.

|

|

|

|

Total elements |

| 40 |

40 |

40 |

200 |

10,803 |

Table 5.

RANS meshes for the sensitivity study.

Table 5.

RANS meshes for the sensitivity study.

| Name |

|

|

|

Max. ER |

Max.

|

| M1 |

137 |

121 |

∼50,000 |

1.20 |

1.02 |

| M2 |

177 |

157 |

∼80,000 |

1.20 |

0.64 |

| M3 |

209 |

189 |

∼115,000 |

1.20 |

0.38 |

| M4 |

241 |

213 |

∼150,000 |

1.20 |

0.26 |

| M5 |

261 |

229 |

∼180,000 |

1.20 |

0.13 |

Table 6.

RANS inlet turbulence parameters matching the experimental decay.

Table 6.

RANS inlet turbulence parameters matching the experimental decay.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.70 |

|

20.396 |

16275 |

2.60 |

0.93 |

| 0.80 |

|

23.585 |

20237 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.90 |

|

24.991 |

22074 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.70 |

|

20.733 |

16680 |

2.62 |

0.93 |

| 0.80 |

|

23.656 |

20329 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.90 |

|

25.067 |

22175 |

2.62 |

0.93 |

| 0.95 |

|

25.086 |

22200 |

2.60 |

0.93 |

| 0.70 |

|

21.269 |

17331 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.80 |

|

23.719 |

20410 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.90 |

|

25.271 |

22446 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.95 |

|

25.486 |

22733 |

2.63 |

0.93 |

| 0.70 |

|

21.585 |

17718 |

2.65 |

0.93 |

| 0.80 |

|

24.066 |

20859 |

2.64 |

0.93 |

| 0.90 |

|

25.370 |

22578 |

2.62 |

0.93 |

| 0.95 |

|

25.600 |

22885 |

2.61 |

0.93 |

Table 7.

Separation location, , from experiments, CFD, and MISES under steady inlet flow.

Table 7.

Separation location, , from experiments, CFD, and MISES under steady inlet flow.

| |

|

Exp. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

from

|

from

|

|

CFD |

|

MISES |

|

| 65,000 |

0.70 |

0.612 |

- |

- |

0.614 |

0.21 |

0.619 |

0.68 |

| |

0.80 |

0.637 |

- |

- |

0.669 |

3.17 |

0.681 |

4.41 |

| |

0.90 |

0.747 |

- |

- |

0.730 |

-1.67 |

- |

- |

| 70,000 |

0.70 |

0.610 |

0.601 |

-1.53 |

0.614 |

0.42 |

0.619 |

0.89 |

| |

0.80 |

0.637 |

|

|

0.662 |

2.49 |

0.676 |

3.84 |

| |

0.90 |

0.741 |

0.752 |

1.55 |

0.723 |

-1.73 |

- |

- |

| 100,000 |

0.70 |

0.612 |

- |

- |

0.601 |

-1.15 |

0.602 |

-1.00 |

| |

0.80 |

0.635 |

- |

- |

0.669 |

3.37 |

0.676 |

4.04 |

| |

0.90 |

0.716 |

- |

- |

0.703 |

-1.29 |

0.756 |

3.99 |

| 120,000 |

0.70 |

0.610 |

0.601 |

-1.53 |

0.614 |

0.42 |

0.602 |

-0.79 |

| |

0.80 |

0.637 |

- |

- |

0.662 |

2.49 |

0.670 |

3.27 |

| |

0.90 |

0.712 |

0.691 |

-2.89 |

0.723 |

1.16 |

0.733 |

2.10 |

Table 8.

Reattachment location, , from experiments, CFD, and MISES.

Table 8.

Reattachment location, , from experiments, CFD, and MISES.

| |

|

Exp. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

from

|

from

|

|

CFD |

|

MISES |

|

| 65,000 |

0.70 |

0.931 |

- |

- |

0.985 |

5.46 |

0.848 |

-8.23 |

| 70,000 |

0.70 |

0.921 |

- |

- |

0.972 |

5.12 |

0.837 |

-8.45 |

| 100,000 |

0.70 |

0.871 |

- |

- |

0.852 |

-1.84 |

0.802 |

-6.86 |

| |

0.80 |

0.932 |

- |

- |

0.915 |

-1.75 |

0.854 |

-7.86 |

| 120,000 |

0.70 |

0.858 |

0.873 |

1.800 |

0.771 |

-8.68 |

0.773 |

-8.44 |

| |

0.80 |

0.921 |

- |

- |

0.845 |

-7.58 |

0.831 |

-9.05 |

Table 9.

Constants for the Thwaites–parameter separation criteria.

Table 9.

Constants for the Thwaites–parameter separation criteria.

| Model |

Const. |

| Pohlhausen [50] |

-0.1567 |

| Timman [51] |

-0.0871 |

| Walz [54] |

-0.0682 |

| Thwaites [55] |

-0.0820 |

| Curle and Skan [52] |

-0.0900 |

Table 10.

Constants for the Stratford–type separation criteria.

Table 10.

Constants for the Stratford–type separation criteria.

| Model |

Const. |

| Stratford [53],

|

0.0108 |

| Stratford [53],

|

6.48×10−3

|

Table 11.

Summary of blade loading parameters.

Table 11.

Summary of blade loading parameters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.70 |

65,000 |

0.95 |

25 |

0.35 |

0.82 |

| 0.80 |

65,000 |

0.95 |

20 |

0.33 |

0.78 |

| 0.90 |

65,000 |

0.95 |

18 |

0.35 |

0.73 |

| 0.70 |

70,000 |

0.94 |

25 |

0.35 |

0.82 |

| 0.80 |

70,000 |

0.95 |

21 |

0.34 |

0.78 |

| 0.90 |

70,000 |

0.97 |

18 |

0.37 |

0.73 |

| 0.95 |

70,000 |

0.98 |

16 |

0.39 |

0.71 |

| 0.70 |

100,000 |

0.95 |

24 |

0.34 |

0.81 |

| 0.80 |

100,000 |

0.97 |

20 |

0.35 |

0.77 |

| 0.90 |

100,000 |

0.99 |

16 |

0.36 |

0.73 |

| 0.95 |

100,000 |

0.98 |

17 |

0.40 |

0.71 |

| 0.70 |

120,000 |

0.95 |

24 |

0.35 |

0.81 |

| 0.80 |

120,000 |

0.97 |

21 |

0.36 |

0.77 |

| 0.90 |

120,000 |

0.98 |

17 |

0.36 |

0.73 |

| 0.95 |

120,000 |

0.98 |

16 |

0.38 |

0.70 |

Table 12.

Mean error in estimating the separation location.

Table 12.

Mean error in estimating the separation location.

| Model |

Mean error

|

| Pohlhausen [50] |

-7.8 |

| Timman [51] |

-13.6 |

| Walz [54] |

-15.8 |

| Thwaites [55] |

-14.2 |

| Curle and Skan [52] |

-13.4 |

| Stratford [53], , w/o LE corr. |

-11.7 |

| Stratford [53], , w/o LE corr. |

-13.8 |

| Stratford [53], , w/ LE corr. |

-8.1 |

| Stratford [53], , w/ LE corr. |

-8.2 |

Table 13.

Mean error in estimating the separation location for each Mach number for the Pohlhausen and Stratford criteria.

Table 13.

Mean error in estimating the separation location for each Mach number for the Pohlhausen and Stratford criteria.

|

Pohlhausen |

Stratford, , w/ LE corr. |

| 0.70 |

-6.2 |

-7.5 |

| 0.80 |

-3.1 |

-4.5 |

| 0.90 |

-9.7 |

-9.5 |

| 0.95 |

-13.6 |

-12.1 |