Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

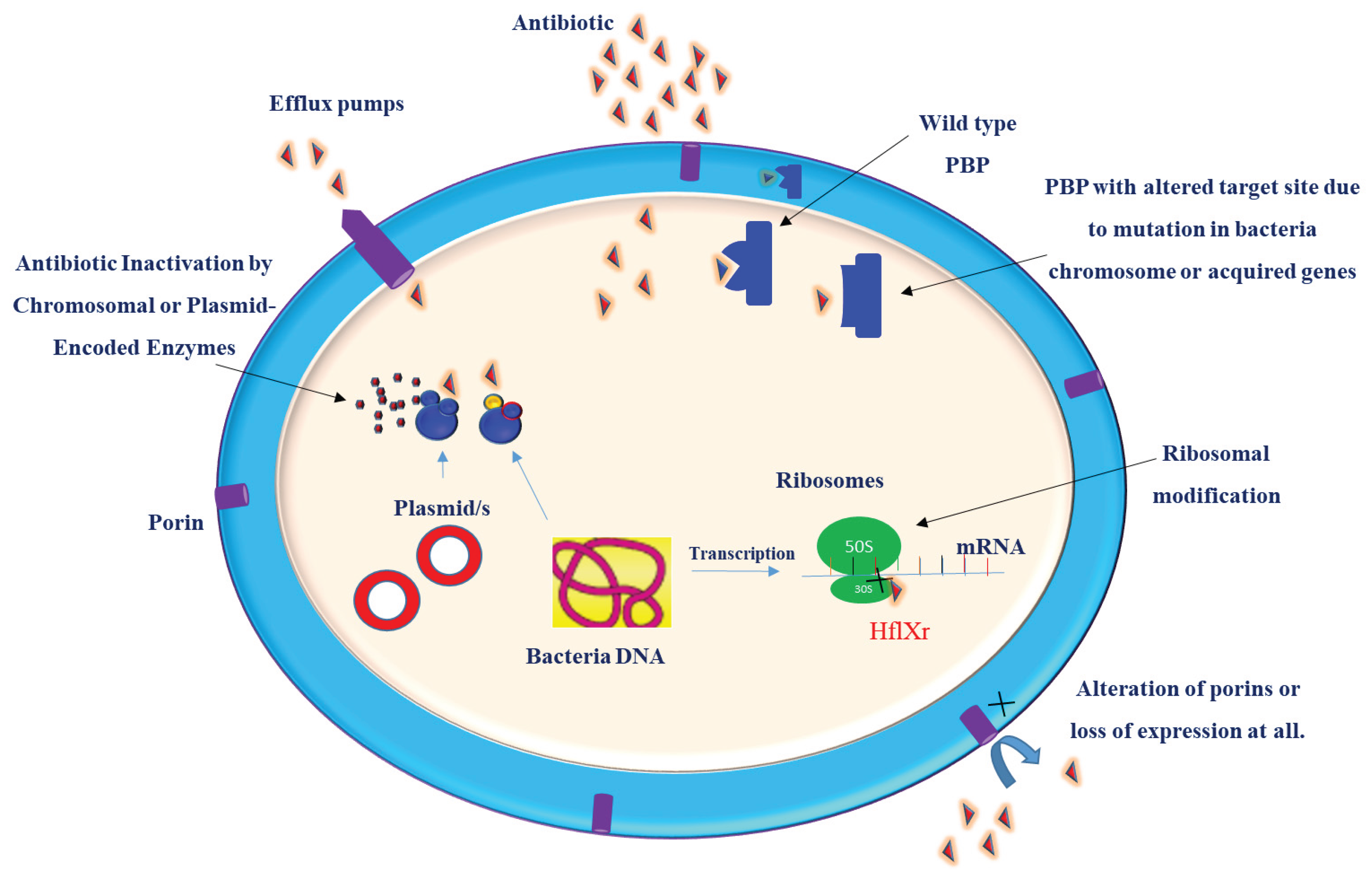

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a prominent pathogen implicated in a wide range of infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and septicemia. Its ability to acquire and disseminate antibiotic resistance, coupled with the rising prevalence of hypervirulent strains, represents a significant public health threat. Understanding the molecular basis of drug resistance can guide the design and development of effective treatment strategies. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in these bacteria is a complicated process and cannot be attributed to only a single resistance mechanism. K. pneumoniae develops resistance to antibiotics through a variety of mechanisms, ranging from single molecular mechanisms to complex interactions, where molecular synergy exacerbates resistance. This review summarizes the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the drug resistance and virulence of this pathogen. Key antibiotic resistance mechanisms include drug inactivation via B-lactamases and carbapenemases, membrane remodeling, efflux pump systems, such as AcrAB-TolC and OqxAB, and biofilm formation facilitated by quorum sensing. Additionally, the role of ribosomal changes in resistance was highlighted. This review also examines the mechanisms of virulence, emphasizing fimbriae, iron acquisition systems, and immune evasion strategies. Understanding these mechanisms of drug resistance and virulence is crucial for remodeling existing antibiotics and developing new therapeutic strategies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Antimicrobial Resistance in K. pneumoniae

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in K. pneumoniae

2.1. Drug Inactivation and Target Modification

2.1.1. B-Lactamases

2.1.2. Carbapenemases

2.1.2.1. Serine Carbapenemases (Molecular Class A Carbapenemases)

2.1.2.2. Molecular Class B Carbapenemases /Metallo- B-Lactamases (MBLs)

2.1.2.3. Molecular Class D Carbapenemases (OXA Carbapenemase)

2.1.2.4. K. pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)

2.1.2.5. Imipenemase (IMP)

2.1.2.6. Verona Integron-Encoded Metallo-B-Lactamases (VIMs)

2.1.2.7. New Delhi Metallo-B-Lactamases (NDM)

| Enzyme Class | Molecular Class | Representative Enzymes | Substrate Specificity | Inhibition | Ref |

| Serine-B-lactamases (Class A) | A | KPC,TEM, SHV, CTX-M | Penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems (KPC) | Inhibited by clavulanic acid, sulbactam | [46,47] |

| Metallo-B-lactamases (Class B) | B | IMP, NDM, VIM, SPM, GIM | Broad spectrum including carbapenems, not monobactams | Inhibited by metal chelators (e.g., EDTA) | [45,46] |

| Serine-B-lactamases (Class C) | C | AmpC-type enzymes | Cephalosporins, penicillins | Not inhibited by clavulanic acid | [39,142] |

| Oxacillinases (Class D) | D | OXA-48-like carbapenemases, OXA-23, OXA-24/40, OXA-58, OXA-1, OXA-10 | Penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems (OXA-48 group) | Variable inhibition by clavulanic acid | [54] |

| Extended-Spectrum-B-Lactamases (ESBLs) | Mostly Class A | CTX-M, SHV variants, TEM variants | Expanded activity against third-generation cephalosporins | Inhibited by clavulanic acid | [41,42] |

| Carbapenemases (Functional Group) | Classes A, B, D | KPC (A), IMP, VIM, NDM (B), OXA-48-like (D) | Hydrolyze carbapenems and other β-lactams | Varies by class (see above) | [45,46,59,74,80,81] |

2.1.3. Resistance to Colistin, Aminoglycosides, and Fluoroquinolones

2.2. Membrane Remodeling

2.3. Efflux Pump Systems

2.4. Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation

3. Molecular Mechanisms of Virulence and Pathogenicity in K. pneumoniae

3.1. Fimbriae

3.2. Iron Acquisition Systems

3.3. Capsule

4. Novel Therapeutic Strategies

5. Conclusion

Disclosure

References

- Kumar, V., et al., Comparative genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with different antibiotic resistance profiles. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2011. 55(9): p. 4267-4276. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J., et al., Insights into the evolution of gene organization and multidrug resistance from Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmid pKF3-140. Gene, 2013. 519(1): p. 60-66. [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M.K. and J. Mecsas, Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews, 2016. 80(3): p. 629-661. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K. Klebsiella (https://www.britannica.com/science/Klebsiella). 2022.

- Bengoechea, J.A. and J. Sa Pessoa, Klebsiella pneumoniae infection biology: living to counteract host defences. FEMS microbiology reviews, 2019. 43(2): p. 123-144.

- Murray, C.J., et al., Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The lancet, 2022. 399(10325): p. 629-655. [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C., et al., Population genomics of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal-group 23 reveals early emergence and rapid global dissemination. Nature Communications, 2018. 9(1): p. 2703. [CrossRef]

- Hala, S., et al., The emergence of highly resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae CC14 clone in a tertiary hospital over 8 years. Genome Med, 2024. 16(1): p. 58. [CrossRef]

- WHO, Antimicrobial Resistance, Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - Global situation (https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON527). 2024.

- Riwu, K.H.P., et al., A review: Virulence factors of Klebsiella pneumonia as emerging infection on the food chain. Vet World, 2022. 15(9): p. 2172-2179. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.d.S.S., S.M. Cordeiro, and J.N. Reis, Virulence Factors in Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Literature Review. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 2024. 64(2): p. 389-401. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., et al., The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2020. 17(17): p. 6278. [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T., et al., Phage therapy: past, present and future. 2017, Frontiers Media SA. p. 981. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.M., et al., Isolation and characterization of Klebsiella phages for phage therapy. Therapy, Applications, and Research, 2021. 2(1): p. 26-42. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A.A. and A.G. Birhanu, Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Drug Resistance Development and Novel Strategies to Combat. Infect Drug Resist, 2023. 16: p. 7641-7662. [CrossRef]

- Willy, C., et al., Phage Therapy in Germany-Update 2023. Viruses, 2023. 15(2).

- WHO, WHO bacterial priority pathogens list, 2024(https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461), in WHO. 2024.

- WHO, Antimicrobial Resistance, Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - Global situation (https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON527) searched in september 2024. . 2024.

- Li, Y., S. Kumar, and L. Zhang, Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and Developments in Therapeutic Strategies to Combat Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. Infect Drug Resist, 2024. 17: p. 1107-1119. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., Characteristics of antibiotic resistance mechanisms and genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Open Med (Wars), 2023. 18(1): p. 20230707. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella: Advances in Detection Methods and Clinical Implications. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2025: p. 1339-1354. [CrossRef]

- Moya, C. and S. Maicas. Antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains: mechanisms and outbreaks. in Proceedings. 2020. MDPI.

- Navon-Venezia, S., K. Kondratyeva, and A. Carattoli, Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS microbiology reviews, 2017. 41(3): p. 252-275. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Barba, S., E.M. Top, and T. Stalder, Plasmids, a molecular cornerstone of antimicrobial resistance in the One Health era. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2024. 22(1): p. 18-32. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., Characteristics of antibiotic resistance mechanisms and genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Open Medicine, 2023. 18(1): p. 20230707. [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.M., et al., Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nature reviews microbiology, 2015. 13(1): p. 42-51.

- Gaurav, A., et al., Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance, virulence, and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology, 2023. 169(5): p. 001333. [CrossRef]

- Queenan, A.M. and K. Bush, Carbapenemases: the versatile β-lactamases. Clinical microbiology reviews, 2007. 20(3): p. 440-458. [CrossRef]

- Bush, K. and P.A. Bradford, β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016. 6(8).

- Dabhi, M., et al., Penicillin-binding proteins: the master builders and breakers of bacterial cell walls and its interaction with β-lactam antibiotics. Journal of Proteins and Proteomics, 2024. 15(2): p. 215-232. [CrossRef]

- Sethuvel, D.P.M., et al., β-Lactam Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens Mediated Through Modifications in Penicillin-Binding Proteins: An Overview. Infect Dis Ther, 2023. 12(3): p. 829-841. [CrossRef]

- Heijenoort, J.v., Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Glycobiology, 2001. 11(3): p. 25R-36R. [CrossRef]

- Garde, S., P.K. Chodisetti, and M. Reddy, Peptidoglycan: structure, synthesis, and regulation. EcoSal Plus, 2021. 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., et al., Structural Insights for β-Lactam Antibiotics. Biomol Ther (Seoul), 2023. 31(2): p. 141-147.

- Tsai, Y.K., et al., Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 play roles in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(4): p. 1485-93. [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, E., S. Kojima, and H. Nikaido, Klebsiella pneumoniae Major Porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 Allow More Efficient Diffusion of β-Lactams than Their Escherichia coli Homologs OmpF and OmpC. J Bacteriol, 2016. 198(23): p. 3200-3208. [CrossRef]

- Raouf, F.E.A., et al., Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among Klebsiella pneumoniae from Iraqi patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992), 2022. 68(6): p. 833-837. [CrossRef]

- Soltani, E., et al., Virulence characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its relation with ESBL and AmpC beta-lactamase associated resistance. Iran J Microbiol, 2020. 12(2): p. 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Queenan, A.M. and K. Bush, Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2007. 20(3): p. 440-58, table of contents.

- De, J.M., et al., Review-Understanding β-lactamase Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2015.

- Livermore, D.M., et al., CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2007. 59(2): p. 165-174. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D. and D. Nair, Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Gram Negative Bacteria. Journal of global infectious diseases, 2010. 2(3): p. 263-274. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S., et al., First report of the emergence of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) as the predominant ESBL isolated in a US health care system. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2007. 51(11): p. 4015-4021. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, N.T., et al., Class D β-lactamases: are they all carbapenemases? Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2014. 58(4): p. 2119-2125. [CrossRef]

- Han, R., et al., Dissemination of carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from adult and children patients in China. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2020. 10: p. 314. [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi Halat, D. and C. Ayoub Moubareck, The current burden of carbapenemases: review of significant properties and dissemination among gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics, 2020. 9(4): p. 186. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., et al., Structure and mechanism-guided design of dual serine/metallo-carbapenemase inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2022. 65(8): p. 5954-5974. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.E., et al., Metallo-β-lactamases: structure, function, epidemiology, treatment options, and the development pipeline. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2020. 64(10): p. 10.1128/aac. 00397-20. [CrossRef]

- Palzkill, T., Metallo-β-lactamase structure and function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2013. 1277(1): p. 91-104.

- Ju, L.-C., et al., The continuing challenge of metallo-β-lactamase inhibition: mechanism matters. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2018. 39(7): p. 635-647. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.A., et al., Kinetic and structural characterization of the first B3 metallo-β-lactamase with an active-site glutamic acid. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2021. 65(10): p. 10.1128/aac. 00936-21. [CrossRef]

- Krco, S., et al., Structure, function, and evolution of metallo-β-lactamases from the B3 subgroup—emerging targets to combat antibiotic resistance. Frontiers in Chemistry, 2023. 11: p. 1196073. [CrossRef]

- Selleck, C., et al., AIM-1: An Antibiotic-Degrading Metallohydrolase That Displays Mechanistic Flexibility. Chemistry–A European Journal, 2016. 22(49): p. 17704-17714.

- Yoon, E.-J. and S.H. Jeong, Class D β-lactamases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2021. 76(4): p. 836-864.

- Antunes, N.T. and J.F. Fisher, Acquired class D β-lactamases. Antibiotics, 2014. 3(3): p. 398-434. [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L., A. Potron, and P. Nordmann, OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2012. 67(7): p. 1597-1606. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A., et al., Treatment of infections by OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2018. 62(11): p. 10.1128/aac. 01195-18. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.L., et al., Multiplex detection of the big five carbapenemase genes using solid-phase recombinase polymerase amplification. Analyst, 2024. 149(5): p. 1527-1536. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al., Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol, 2014. 22(12): p. 686-96. [CrossRef]

- Brink, A.J., et al., Emergence of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM-1) and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-2) in South Africa. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2012. 50(2): p. 525-527. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M., et al., Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 with blaoxa-181, South Africa, 2014–2016. Emerging infectious diseases, 2019. 25(4): p. 739.

- Budia-Silva, M., et al., International and regional spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe. Nature communications, 2024. 15(1): p. 5092. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Castañeda, J.A., et al., Mortality due to KPC carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: systematic review and meta-analysis: mortality due to KPC Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Journal of Infection, 2018. 76(5): p. 438-448.

- Shankar, C., et al., KPC-2 producing ST101 Klebsiella pneumoniae from bloodstream infection in India. Journal of medical microbiology, 2018. 67(7): p. 927-930. [CrossRef]

- Remya, P., M. Shanthi, and U. Sekar, Prevalence of blaKPC and its occurrence with other beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Laboratory Physicians, 2018. 10(04): p. 387-391. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., et al., High prevalence of KPC-2-producing hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae causing meningitis in Eastern China. Infection and drug resistance, 2019: p. 641-653. [CrossRef]

- Awoke, T., et al., Detection of bla KPC and bla NDM carbapenemase genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Dominance of bla NDM. PLoS One, 2022. 17(4): p. e0267657. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L., et al., Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase variants: the new threat to global public health. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2023. 36(4): p. e0000823. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.B., et al., KPC-2 allelic variants in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam from Argentina: bla KPC-80, bla KPC-81, bla KPC-96 and bla KPC-97. Microbiology Spectrum, 2024. 12(3): p. e04111-23.

- Robledo, I.E., E.E. Aquino, and G.J. Vázquez, Detection of the KPC gene in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii during a PCR-based nosocomial surveillance study in Puerto Rico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(6): p. 2968-70. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.C., et al., Emergence of Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli Isolates possessing the plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 in intensive care units of a Chinese hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2008. 52(6): p. 2014-8. [CrossRef]

- Validi, M., et al., Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella oxytoca in clinical isolates in Tehran Hospitals, Iran by chromogenic medium and molecular methods. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 2016. 7(5): p. 301-306. [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, K.M., et al., Global dissemination of bla KPC into bacterial species beyond Klebsiella pneumoniae and in vitro susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2016. 60(8): p. 4490-4500. [CrossRef]

- Pongchaikul, P. and P. Mongkolsuk, Comprehensive analysis of imipenemase (IMP)-type metallo-β-lactamase: a global distribution threatening asia. Antibiotics, 2022. 11(2): p. 236. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.F., et al., The brief case: IMP, the uncommonly common carbapenemase. 2020, American Society for Microbiology 1752 N St., NW, Washington, DC. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., et al., Carbapenem use is driving the evolution of imipenemase 1 variants. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2021. 65(4): p. 10.1128/aac. 01714-20. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella: Advances in Detection Methods and Clinical Implications. Infect Drug Resist, 2025. 18: p. 1339-1354. [CrossRef]

- Tada, T., et al., IMP-43 and IMP-44 metallo-β-lactamases with increased carbapenemase activities in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2013. 57(9): p. 4427-32. [CrossRef]

- Tada, T., et al., IMP-43 and IMP-44 metallo-β-lactamases with increased carbapenemase activities in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2013. 57(9): p. 4427-4432. [CrossRef]

- Bahr, G., L.J. Gonzalez, and A.J. Vila, Metallo-β-lactamases in the age of multidrug resistance: from structure and mechanism to evolution, dissemination, and inhibitor design. Chemical reviews, 2021. 121(13): p. 7957-8094. [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, M.A., Variations in carbapenem resistance associated with the Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase across the order Enterobacterales. 2022, Queen's University (Canada).

- Lombardi, G., et al., Nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas putida producing VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2002. 40(11): p. 4051-4055. [CrossRef]

- Makena, A., et al., Comparison of Verona integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase (VIM) variants reveals differences in stability and inhibition profiles. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2016. 60(3): p. 1377-1384. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., et al., High prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and identification of a novel VIM-type metallo-β-lactamase, VIM-92, in clinical isolates from northern China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2025. 16: p. 1543509. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y., et al., Genomic epidemiology of global VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2017. 72(8): p. 2249-2258. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., et al., NDM Metallo-β-Lactamases and Their Bacterial Producers in Health Care Settings. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2019. 32(2). [CrossRef]

- Halaby, T., et al., A case of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1 (NDM-1)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with putative secondary transmission from the Balkan region in the Netherlands. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012. 56(5): p. 2790-1. [CrossRef]

- Al-Agamy, M.H., et al., Cooccurrence of NDM-1, ESBL, RmtC, AAC(6')-Ib, and QnrB in Clonally Related Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Together with Coexistence of CMY-4 and AAC(6')-Ib in Enterobacter cloacae Isolates from Saudi Arabia. Biomed Res Int, 2019. 2019: p. 6736897. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.B., et al., Evolution of Colistin Resistance in the Klebsiella pneumoniae Complex Follows Multiple Evolutionary Trajectories with Variable Effects on Fitness and Virulence Characteristics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2020. 65(1). [CrossRef]

- Minarini, L.A. and A.L. Darini, Mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions of gyrA and parC in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Brazil. Braz J Microbiol, 2012. 43(4): p. 1309-14.

- Kherroubi, L., J. Bacon, and K.M. Rahman, Navigating fluoroquinolone resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: a comprehensive evaluation. JAC Antimicrob Resist, 2024. 6(4): p. dlae127. [CrossRef]

- García-Sureda, L., et al., OmpK26, a novel porin associated with carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2011. 55(10): p. 4742-4747. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, G.A., D.M. Mills, and N. Chow, Role of β-lactamases and porins in resistance to ertapenem and other β-lactams in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2004. 48(8): p. 3203-3206.

- Fairman, J.W., N. Noinaj, and S.K. Buchanan, The structural biology of β-barrel membrane proteins: a summary of recent reports. Current opinion in structural biology, 2011. 21(4): p. 523-531. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., et al., Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell, 2005. 121(2): p. 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Hagan, C.L., T.J. Silhavy, and D. Kahne, β-Barrel membrane protein assembly by the Bam complex. Annual review of biochemistry, 2011. 80(1): p. 189-210. [CrossRef]

- Rosas, N.C. and T. Lithgow, Targeting bacterial outer-membrane remodelling to impact antimicrobial drug resistance. Trends in Microbiology, 2022. 30(6): p. 544-552. [CrossRef]

- Ni, R.T., et al., The role of RND-type efflux pumps in multidrug-resistant mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 10876. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., S. Kumar, and L. Zhang, Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance and developments in therapeutic strategies to combat Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2024: p. 1107-1119. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M. and A. Amare, Biofilm-Associated Multi-Drug Resistance in Hospital-Acquired Infections: A Review. Infect Drug Resist, 2022. 15: p. 5061-5068. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A., J. Sun, and Y. Liu, Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2023. 13: p. 1137947. [CrossRef]

- Raju, D.V., et al., Effect of bacterial quorum sensing and mechanism of antimicrobial resistance. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 2022. 43: p. 102409. [CrossRef]

- Papenfort, K. and B.L. Bassler, Quorum sensing signal–response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2016. 14(9): p. 576-588. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H., S. Aulakh, and M. Paetzel, The bacterial outer membrane β-barrel assembly machinery. Protein Sci, 2012. 21(6): p. 751-68.

- Balestrino, D., et al., Characterization of type 2 quorum sensing in Klebsiella pneumoniae and relationship with biofilm formation. J Bacteriol, 2005. 187(8): p. 2870-80. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. and M. Ni, Regulation of biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol, 2023. 14: p. 1238482. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., et al., Virulence Factors in Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol, 2021. 12: p. 642484. [CrossRef]

- Weber-Dąbrowska, B., et al., Characteristics of Environmental Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca Bacteriophages and Their Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics, 2023. 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M.K., High-Throughput Identification and Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae Virulence Determinants in the Lungs. 2017, Tufts University-Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

- Klebba, P.E., et al., Iron acquisition systems of gram-negative bacterial pathogens define TonB-dependent pathways to novel antibiotics. Chemical reviews, 2021. 121(9): p. 5193-5239. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. and J.S. Marshall, Mechanics of biofilms formed of bacteria with fimbriae appendages. PLoS One, 2020. 15(12): p. e0243280. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C., et al., Regulation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae Kpc fimbriae by the site-specific recombinase KpcI. Microbiology, 2010. 156(7): p. 1983-1992. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C., et al., Regulation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae Kpc fimbriae by the site-specific recombinase KpcI. Microbiology (Reading), 2010. 156(Pt 7): p. 1983-1992. [CrossRef]

- Caneiras, C., et al., Community- and Hospital-Acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infections in Portugal: Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms, 2019. 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Adeolu, M., et al., Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the 'Enterobacteriales': proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2016. 66(12): p. 5575-5599.

- Andrews, S.C., A.K. Robinson, and F. Rodríguez-Quiñones, Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2003. 27(2-3): p. 215-37. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, K.N., E.A. Dertz, and S.S. Kim, Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 2003. 100(7): p. 3584-3588. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A. and V. Braun, Iron uptake and iron limited growth of Escherichia coli K-12. Arch Microbiol, 1981. 130(5): p. 353-6. [CrossRef]

- Parrow, N.L., R.E. Fleming, and M.F. Minnick, Sequestration and scavenging of iron in infection. Infect Immun, 2013. 81(10): p. 3503-14. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., et al., Genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology of outbreaks of Klebsiella pneumoniae mastitis on two large Chinese dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 2021. 104(1): p. 762-775. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., et al., Effects of iron on the growth, biofilm formation and virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing liver abscess. BMC microbiology, 2020. 20: p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., et al., Emergence and genomics of OXA-232-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a hospital in Yancheng, China. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 2021. 26: p. 194-198. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.C., et al., Structural and functional delineation of aerobactin biosynthesis in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2018. 293(20): p. 7841-7852. [CrossRef]

- Remya, P., M. Shanthi, and U. Sekar, Characterisation of virulence genes associated with pathogenicity in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Indian journal of medical microbiology, 2019. 37(2): p. 210-218. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, G., et al., Molecular analysis of the contribution of the capsular polysaccharide and the lipopolysaccharide O side chain to the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a murine model of pneumonia. Infection and immunity, 2002. 70(5): p. 2583-2590. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., et al., Klebsiella pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide: Mechanism in regulation of synthesis, virulence, and pathogenicity. Virulence, 2024. 15(1): p. 2439509. [CrossRef]

- Raetz, C.R., et al., Discovery of new biosynthetic pathways: the lipid A story. Journal of lipid research, 2009. 50: p. S103-S108. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, C., Biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide O antigens. Trends in microbiology, 1995. 3(5): p. 178-185. [CrossRef]

- Nang, S.C., et al., Polymyxin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: multifaceted mechanisms utilized in the presence and absence of the plasmid-encoded phosphoethanolamine transferase gene mcr-1. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2019. 74(11): p. 3190-3198. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-J., et al., Genetic analysis of capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene clusters in 79 capsular types of Klebsiella spp. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 15573. [CrossRef]

- Brisse, S., et al., wzi Gene sequencing, a rapid method for determination of capsular type for Klebsiella strains. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2013. 51(12): p. 4073-4078. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-J., et al., Identification of capsular types in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains by wzc sequencing and implications for capsule depolymerase treatment. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2015. 59(2): p. 1038-1047. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-J., et al., Capsular polysaccharide synthesis regions in Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K57 and a new capsular serotype. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2008. 46(7): p. 2231-2240. [CrossRef]

- Siu, L.K., et al., Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. The Lancet infectious diseases, 2012. 12(11): p. 881-887.

- Hung, C.H., et al., Experimental phage therapy in treating Klebsiella pneumoniae-mediated liver abscesses and bacteremia in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(4): p. 1358-65. [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.J., et al., Phage Therapy for Limb-threatening Prosthetic Knee Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection: Case Report and In Vitro Characterization of Anti-biofilm Activity. Clin Infect Dis, 2021. 73(1): p. e144-e151. [CrossRef]

- Rubalskii, E., et al., Bacteriophage therapy for critical infections related to cardiothoracic surgery. Antibiotics, 2020. 9(5): p. 232. [CrossRef]

- Eskenazi, A., et al., Combination of pre-adapted bacteriophage therapy and antibiotics for treatment of fracture-related infection due to pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nature communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 302. [CrossRef]

- Doub, J.B., et al., Salphage: salvage bacteriophage therapy for recalcitrant MRSA prosthetic joint infection. Antibiotics, 2022. 11(5): p. 616.

- Asma, S.T., et al., An Overview of Biofilm Formation-Combating Strategies and Mechanisms of Action of Antibiofilm Agents. Life (Basel), 2022. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Chatupheeraphat, C., et al., Synergistic effect and antibiofilm activity of the antimicrobial peptide K11 with conventional antibiotics against multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2023. 13: p. 1153868. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S., et al., Evaluation of co-transfer of plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance genes and bla(NDM) gene in Enterobacteriaceae causing neonatal septicaemia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control, 2019. 8: p. 46. [CrossRef]

- Martins, W., et al., Effective phage cocktail to combat the rising incidence of extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 16. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2022. 11(1): p. 1015-1023. [CrossRef]

- Broncano-Lavado, A., et al., Advances in Bacteriophage Therapy against Relevant MultiDrug-Resistant Pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel), 2021. 10(6). [CrossRef]

- Gan, L., et al., Bacteriophage Effectively Rescues Pneumonia Caused by Prevalent Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Early Stage. Microbiol Spectr, 2022. 10(5): p. e0235822. [CrossRef]

- Chadha, P., O.P. Katare, and S. Chhibber, In vivo efficacy of single phage versus phage cocktail in resolving burn wound infection in BALB/c mice. Microb Pathog, 2016. 99: p. 68-77. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., et al., Promising treatments for refractory pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 2023. 87: p. 104874. [CrossRef]

- Liang, B., et al., Effective of phage cocktail against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection of murine mammary glands. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2023. 182: p. 106218. [CrossRef]

- Kou, X., X. Yang, and R. Zheng, Challenges and opportunities of phage therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2024. 90(10): p. e01353-24. [CrossRef]

| Study / Report | Model / Patient | Phage Therapy Details | Outcome / Success Summary | Ref. |

| φNK5 phage in a mouse model of K. pneumoniae liver infection | Mouse model (liver abscess) | Single dose φNK5, intragastric or intraperitoneal | Protected mice from death, cleared bacteria, reduced liver damage | [135] |

| Personalized phage therapy for prosthetic knee infection | Human patient with prosthetic knee infection | De novo isolated phages φ2 and φ4, used alone | Infection controlled, clinical improvement, tolerated well | [136] |

| Phage cocktail Katrice-16 against MDR K. pneumoniae ST16 | In vitro and preclinical | Cocktail of 8 lytic phages | High in vitro activity against MDR K. pneumoniae, potential for human use | [143] |

| Treated pneumonia caused by MDR K. pneumoniae | A human patient with pneumonia | Increasing doses of nebulized phages over 16 days, combined with antibiotics initially | Clinical improvement, bacterial load reduction, and discharge from hospital | [144] |

| Dual-phage cocktail in mice for K. pneumoniae infection | Mouse model | Dual-phage cocktail | Improved survival rates compared to single phage therapy | |

| Treated pneumonia caused by MDR K. pneumoniae | Murine pneumonia model | Phages pKp11 and pKp383 targeting ST11 and ST383 MDR K. pneumoniae | Effective treatment of pneumonia | [145] |

| Phage cocktail therapy for burn wound infections (includes K. pneumoniae) | Animal model | Phage cocktail | Remarkable therapeutic efficacy and tolerance | [146] |

| Phage therapy in refractory pneumonia caused by MDR K. pneumoniae | Clinical case reports | Phage therapy alone or combined with antibiotics | Promising treatment outcomes in refractory pneumonia | [147] |

| Phage cocktails reduce inflammation in mouse mammary gland infection | Mouse model | Phage cocktail | Reduced bacterial load and inflammatory factors | [148] |

| Phage therapy for carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae in a trauma patient | Human patient | Phage cocktail targeting K. pneumoniae | Avoided amputation, clinical improvement | [144] |

| Phage therapy for K. pneumoniae infections in burn wounds | Animal model | Phage cocktail | Improved survival and infection control | [149] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).