1. Introduction

Human well-being and environmental sustainability are strongly connected. Socio-ecological systems theory recognizes this interdependence and encourages integrated approaches to natural resource management that take account of ecological, social, cultural, and governance dimensions (Berkes and Folke, 1998). Botanical gardens have evolved in this direction. Once focused mainly on plant collections, they now make broader contributions to biodiversity conservation, scientific research, public education, and community development (Mounce et al., 2017; Chen and Sun, 2018).

Botanical gardens function as living laboratories that safeguard threatened species and provide experimental settings for restoration ecology. As ex situ conservation centers, they support seed banking, propagation, and species reintroduction, while strengthening in situ efforts by producing ecological knowledge useful for natural habitats. They also promote environmental learning and help societies adopt more sustainable behavior through public engagement (Zelenika et al., 2018).

At the same time, botanical gardens can generate economic value through ecotourism, training programmes, and green job creation, demonstrating practical pathways to climate-smart development (Wyse Jackson and Sutherland, 2000). In urban areas, botanical gardens offer nature-based solutions that enhance liveability by improving air quality, cooling temperatures, and providing accessible recreation space that benefits physical and mental health (Aronson et al., 2014; Waylen, 2006).

Ethiopia represents a rich context for these functions. It contains more than 6,000 vascular plant species, with nearly 20% endemic to the country (Asefa et al., 2020). This biological wealth is threatened by deforestation, agricultural expansion, land degradation, and climate variability. National strategies such as the Climate-Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) framework aim to tackle these pressures through sustainable land and biodiversity management (Fashing et al., 2022). Botanical gardens in Ethiopia contribute significantly to these priorities by conserving endemic and culturally important species, including enset (Ensete ventricosum) and native Coffea species, which are pillars of food security and rural resilience.

Cultural heritage and traditional ecological knowledge are central to Ethiopia’s landscape governance. Botanical gardens serve as important platforms for documenting Indigenous practices and strengthening community stewardship of biodiversity (Sobrevila, 2008; Dunn, 2017). By integrating local perspectives into conservation planning, botanical gardens can help bridge generational knowledge gaps and enhance public legitimacy and participation.

Despite their growing roles, Ethiopian botanical gardens face systemic constraints. These include under-investment in research facilities, limited trained personnel, fragmented governance relationships, competing institutional priorities, and modest outreach capacity. These challenges reduce their ability to fully support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

To strengthen the contribution of botanical gardens to national sustainability objectives, evidence-based performance evaluation is needed. While international studies increasingly assess gardens as socio-ecological systems, similar comprehensive assessments remain scarce in Africa, including Ethiopia. The present study addresses this gap by examining the institutional performance of three major botanical gardens from a multi-dimensional perspective, focusing on governance, research, education, infrastructure, health and well-being, and cultural integration.

Specifically, the research aims to:

(1) compare performance across the three institutions;

(2) identify factors that influence success; and

(3) propose actions that will enable botanical gardens to fulfil their socio-ecological potential. By linking stakeholder perspectives, management performance, and sustainability goals, this study advances understanding of how botanical gardens can better contribute to climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, and community well-being in Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Research Methods

2.1. Study Area

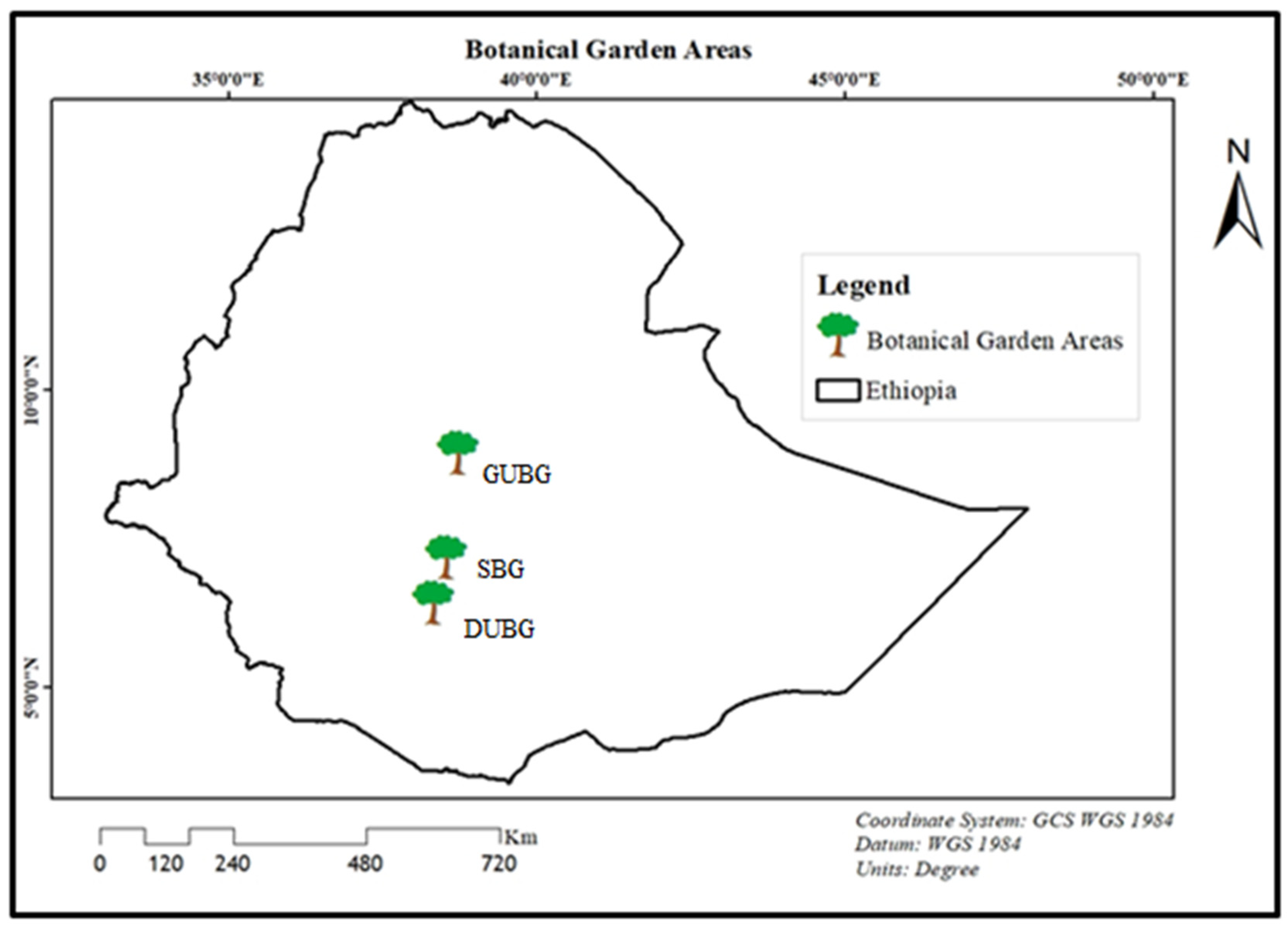

This study was conducted at three major botanical gardens in Ethiopia, selected to represent a range of ecological contexts, institutional affiliations, and conservation mandates. These include Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) located in Addis Ababa; Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG) in Oromia Regional State; and Dilla University Botanical and Ecotourism Garden (DUBEG) in the Gedeo Zone. Their differing landscapes, age, and management structures provide meaningful contrast for assessing performance.

Table 1 presents key characteristics such as year of establishment, area coverage, governance arrangements, and primary objectives. A location map (

Figure 1) further illustrates spatial distribution.

2.2. Study Design

A convergent parallel mixed-methods research design was employed (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2017), enabling simultaneous collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. This approach improved the depth and reliability of findings by allowing cross-validation (triangulation) and providing contextual interpretation that quantitative result alone cannot offer (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010).

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Structured Surveys

A structured questionnaire was developed based on six core domains:

• governance

• research

• education

• infrastructure

• cultural integration

• health and well-being

Respondents rated a series of statements using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire also captured socio-demographic characteristics

Validation

A three-member panel of experts reviewed the survey instrument for clarity and content appropriateness. A pilot test with 30 respondents confirmed reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.75).

Sampling and Administration

A total of 300 stakeholder surveys were completed:

• 100 per botanical garden

• stratified across visitors (20%), staff (30%), researchers (20%), and local residents (30%)

Data were collected during operational hours by trained enumerators with informed verbal consent obtained from each participant.

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Fifteen interviews were conducted with

• garden directors (n = 3)

• senior management officials (n = 6)

• government ministries/agencies (n = 3)

• respected local community elders (n = 3)

Interviews focused on governance arrangements, operational challenges, funding mechanisms, research capacity, community engagement, and strategic priorities. Conversations were recorded (with consent), transcribed, and translated into English for analysis.

2.3.3. Secondary Data and Field Observation

Annual operational reports, internal strategic plans, visitor statistics, and relevant national policy documents including the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) and the CRGE framework were reviewed to complement and contextualize primary data. In addition, a structured field checklist was used to observe infrastructure condition, conservation facilities, and visitor amenities.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative Analysis: Data from the 300 surveys were cleaned and coded for analysis. Descriptive statistics (means, percentages, standard deviations) were computed to summarize stakeholder perceptions and domain scores for each garden. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for statistically significant differences in mean scores among the three gardens. Tukey post-hoc tests identified specific pair wise differences.

A binary logistic regression model was employed to identify which domain scores significantly predicted a garden's classification as high-performing. The dependent variable was binary (high-performing = 1 if composite score ≥ 3.8; else 0). The six domain scores were entered as independent variables. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer Lemeshow test and Nagelkerke R². All quantitative analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.

2.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative Analysis: Interview transcripts and open-ended survey responses were analyzed using a reflexive thematic analysis approach following Braun and Clarke's (2019) framework. This involved an iterative process of data familiarization and systematic coding using NVivo software. It further included initial theme generation, theme review and refinement, and final theme definition and reporting. This process ensured that the themes were strongly grounded in the data while being interpreted through the lens of SES theory. Emerging themes provided rich, explanatory context for the quantitative results, helping to explain the how and why behind the statistical trends.

3. Results

3.1. Composite Performance Overview

Composite scores, calculated as the mean of the six domain scores, revealed notable differences across the three botanical gardens (

Table 2). Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) achieved the highest performance, with a composite score of 4.08/5, placing it firmly in the high-performing category.

In contrast, Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) and Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG) scored 3.45 and 3.60, respectively, corresponding to a low to moderate performance level. A one-way ANOVA confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (F(2, 297) = 15.83, p < 0.001). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that GUBG’s score was significantly higher than both DUBEG (p < 0.001) and SHBG (p = 0.002), whereas the difference between DUBEG and SHBG was not statistically significant (p = 0.215).

These results suggest that GUBG has successfully implemented practices that strengthen its performance across key domains, possibly reflecting better governance, resource management, and engagement with the public and research communities. Meanwhile, the moderate scores of DUBEG and SHBG indicate opportunities for targeted improvements, such as enhancing institutional capacity, diversifying funding sources, and increasing public outreach.

Strengthening these areas could elevate their role in biodiversity conservation and socio-ecological service provision. Overall, the findings highlight both the achievements and challenges of Ethiopian botanical gardens, emphasizing the need for strategic interventions to support their development as high-functioning socio-ecological institutions.

3.2. Determinants of Institutional Success

To test hypothesis H1, a binary logistic regression was conducted to examine the effects of the six domains on the likelihood of a garden being classified as high-performing. The model was statistically significant, χ² (6) = 28.41, p < 0.001, explaining 45.2% of the variance (Nagelkerke R²) and correctly classifying 84.7% of cases. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test indicated a good fit (p = 0.312).

As shown in

Table 3, infrastructure and governance were significant predictors. Infrastructure was the strongest positive predictor (β = 1.20, p = 0.023, Odds Ratio = 3.32), meaning a one-unit increase in infrastructure score increased the odds of being high-performing by 232%. Governance was also positively associated at the 10% significance level (β = 0.92, p = 0.067, Odds Ratio = 2.51). The other domains (research, education, health, cultural integration) were not significant predictors. These results support H1, highlighting the foundational role of governance and infrastructure in garden performance.

3.3. Thematic Analysis of Barriers to Performance

Thematic analysis of 15 in-depth interviews identified four primary, interconnected systemic challenges that provide important context for the quantitative performance scores:

Informants consistently described confusion and overlap in governance. Key government officials noted that the gardens are managed by universities, the city, and a federal institute, with no single coordinating policy or body. This fragmentation leads to competition for scarce resources rather than collaboration. A garden director explained: “We report to different sectors and their priorities are often different, which stalls decision-making and creates bureaucratic inertia.

- 2.

Chronic Funding Instability and Financial Precariousness

All interviewees emphasized financial constraints as a critical barrier. A senior manager stated: Our operational budget is unpredictable and heavily reliant on annual allocations from our parent institution. We cannot plan long-term, capital-intensive projects like species reintroduction programs or major infrastructure upgrades. While some revenue is generated from entry fees and venue rentals, it remains a tiny fraction of what is needed for sustainability, leaving the gardens in a constant state of survival.

- 3.

Limited Community Engagement

The lack of meaningful community involvement emerged as a recurring concern. A local community elder noted: The garden is seen as a government property, fenced off from us. We are not consulted about what plants to grow or how it should be used. They take knowledge from our elders but give little back. A garden staff member echoed this sentiment: Our outreach is mostly one-way; we tell communities about conservation. We haven't yet learned how to genuinely learn from their knowledge and make them true partners in management.

- 4.

Critical Infrastructural Deficits and Maintenance Backlogs

The qualitative findings aligned with the low infrastructure scores for SHBG and DUBEG. A researcher at DUBEG commented: Our research lab has been 'under construction' for two years. Without proper facilities for soil analysis, herbarium specimen preservation, or molecular work, our capacity for advanced, impactful research is severely limited. At SHBG, staff reported unreliable water supply for irrigation and deteriorating staff facilities, which negatively affected morale and operational capacity.

3.4. Domain-Based Performance Insights

3.4.1. Governance and Administrative Performance

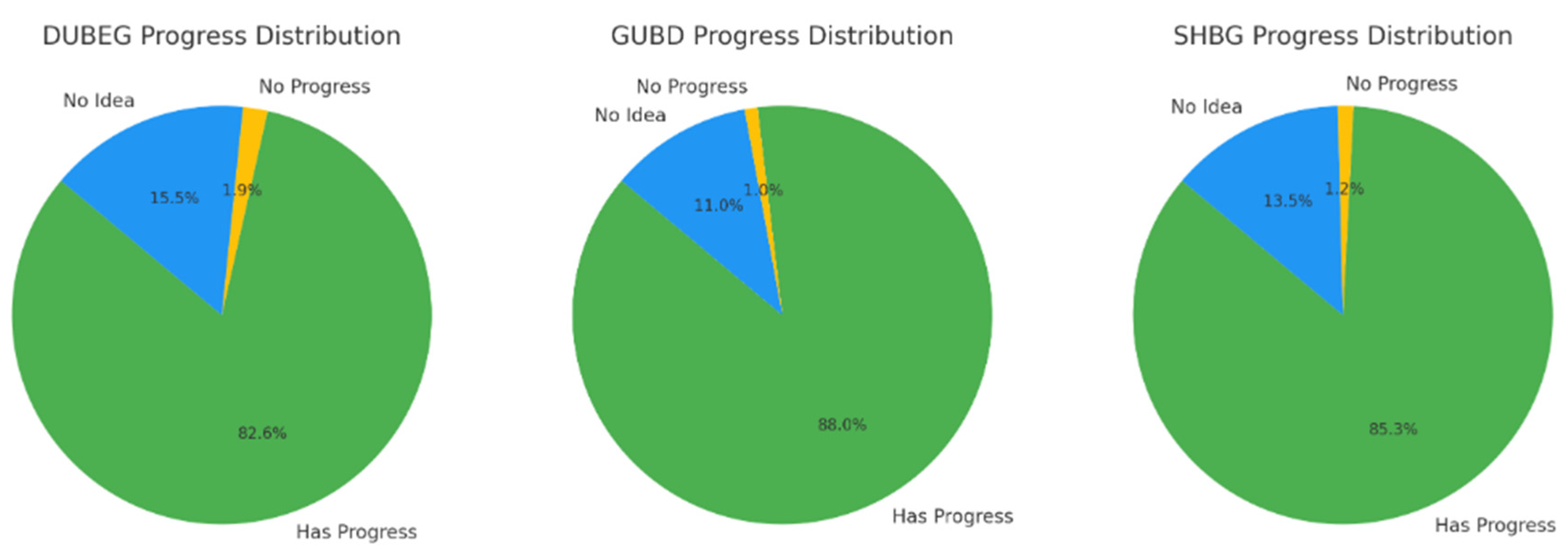

Stakeholder perceptions of administrative progress are shown in

Table 4. A Chi-square test indicated a significant association between the garden and perceived progress (χ² (4) = 10.85, p = 0.028). GUBG had the highest perceived progress (88%), attributed to its clear dual-governance model between the city and university. However, internal challenges remain, with one manager noting: Competing expectations between the recreational focus of the city and the academic focus of the university.

DUBEG (82.6% perceived progress) was seen as financially vulnerable due to reliance on fluctuating university funding. SHBG, under the federal Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI), lacked local visibility and operational autonomy, with 13.5% of stakeholders unaware of its operations, reflecting a gap between its national mandate and local presence.

Figure 2.

Adumbrative Performance of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

Figure 2.

Adumbrative Performance of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

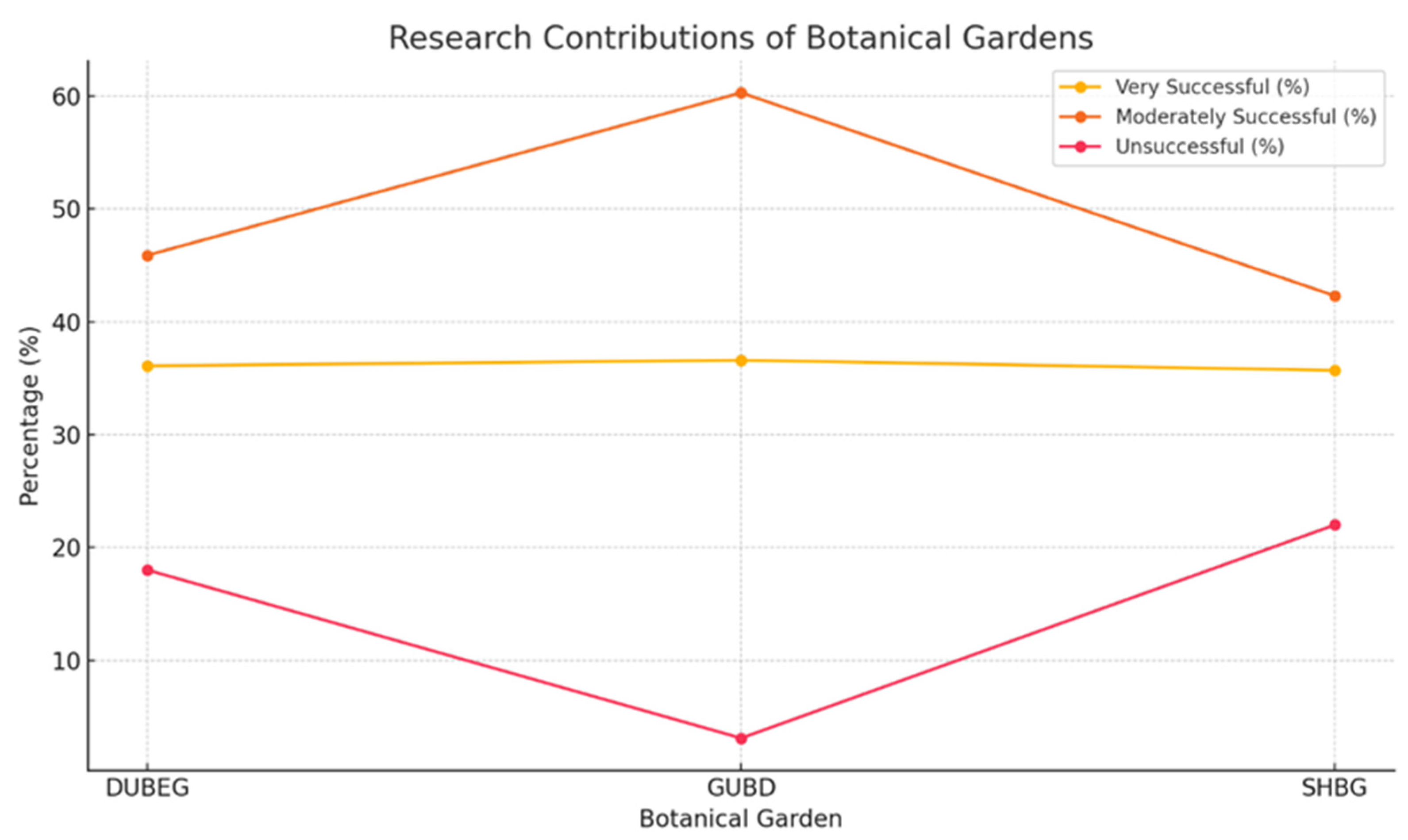

3.4.2. Research Contributions

Evaluation of research contributions is summarized in

Table 5. A one-way ANOVA showed significant differences in perceived research success among the gardens (F(2, 297) = 8.91, p < 0.001). GUBG led, with 60.3% of respondents rating its contributions as

moderately successful reflecting its strong infrastructure and partnerships. DUBEG also showed notable research engagement, with 36.1% of respondents rating it as

very successful supported by its academic environment and focus on endemic species.

In contrast, SHBG had the highest proportion of respondents (22%) rating its research efforts as unsuccessful, highlighting clear performance gaps. These gaps are likely linked to resource limitations and the garden’s focus on ethno-botany, which may be less visible in traditional academic metrics.

Figure 3.

Research Contributions of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

Figure 3.

Research Contributions of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

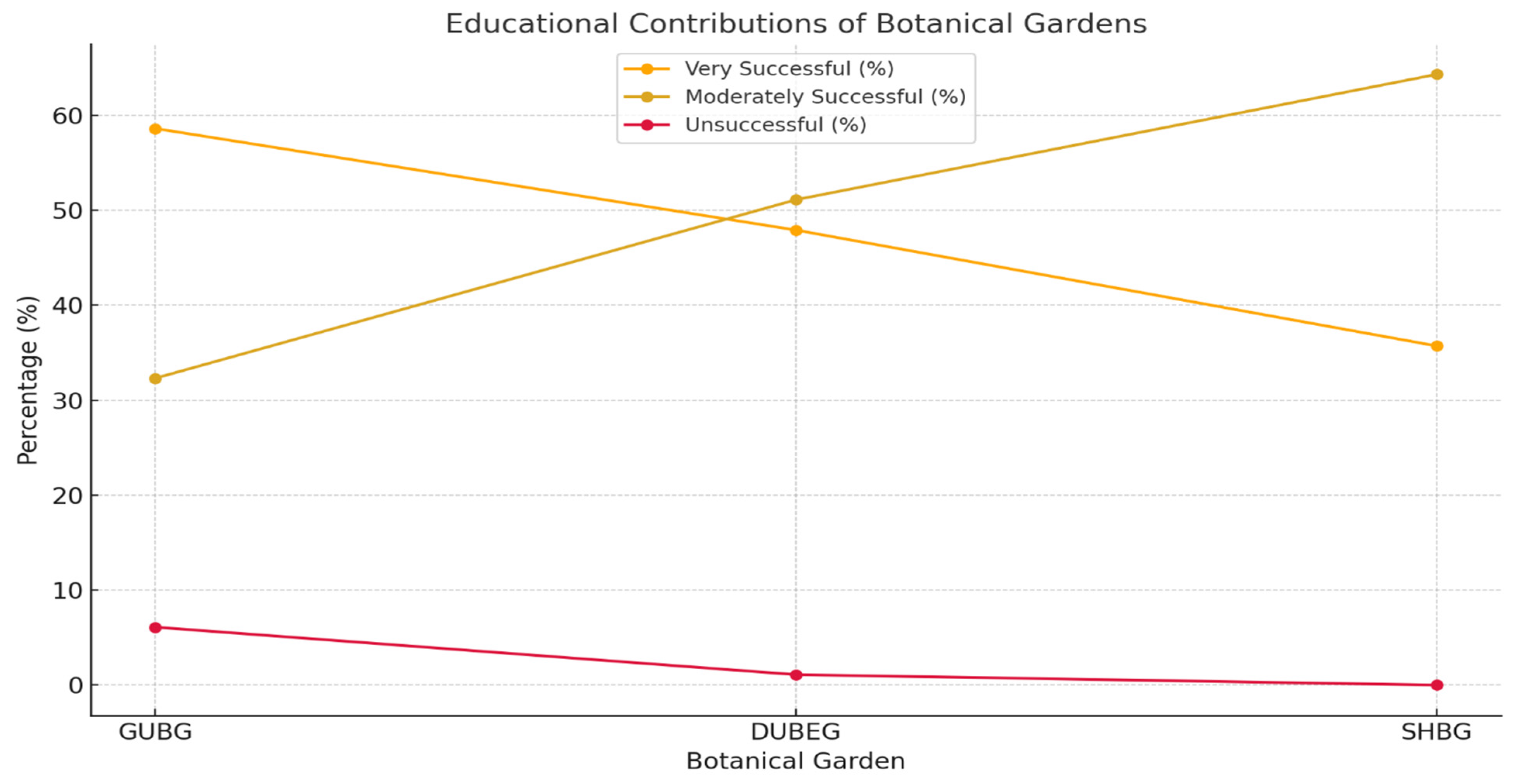

3.4.3. Educational Contribution of Botanical Gardens

Botanical gardens play a key role in environmental education, raising sustainability awareness and linking formal curricula with hands-on learning (Argaw, 2015). In this study, the educational effectiveness of the three gardens varied notably (

Table 6). A one-way ANOVA confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (F(2, 297) = 5.12, p = 0.032).

Figure 4.

Educational Contributions. Source: Survey Questions.

Figure 4.

Educational Contributions. Source: Survey Questions.

The ANOVA results indicate a statistically significant difference in educational performance among the gardens (p = 0.032). Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) emerged as the top performer, with 58.6% of respondents rating its educational programs as very successful. This is supported by structured initiatives such as guided tours and formal school partnerships. An interview with GUBG’s outreach director highlighted that the garden serves around 20,000 high school students annually a scale made possible by strong institutional support and dedicated outreach staff.

In contrast, Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG), despite its prime location in the UNESCO-recognized Gedeo agroforestry landscape and access to university resources, received a more moderate assessment. While 99% of respondents acknowledged some level of success, only 47.9% rated it as very successful suggesting its educational potential is underutilized. Qualitative data points to a possible academic bubble effect, where the garden’s focus may lean more toward university-level research than broader public engagement.

Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG) faces the most significant challenges, with the lowest proportion (35.7%) of very successful ratings. While no respondent deemed it unsuccessful, its primary need is to enhance visibility and develop more robust, structured educational programming to reach its full potential as a community educational resource.

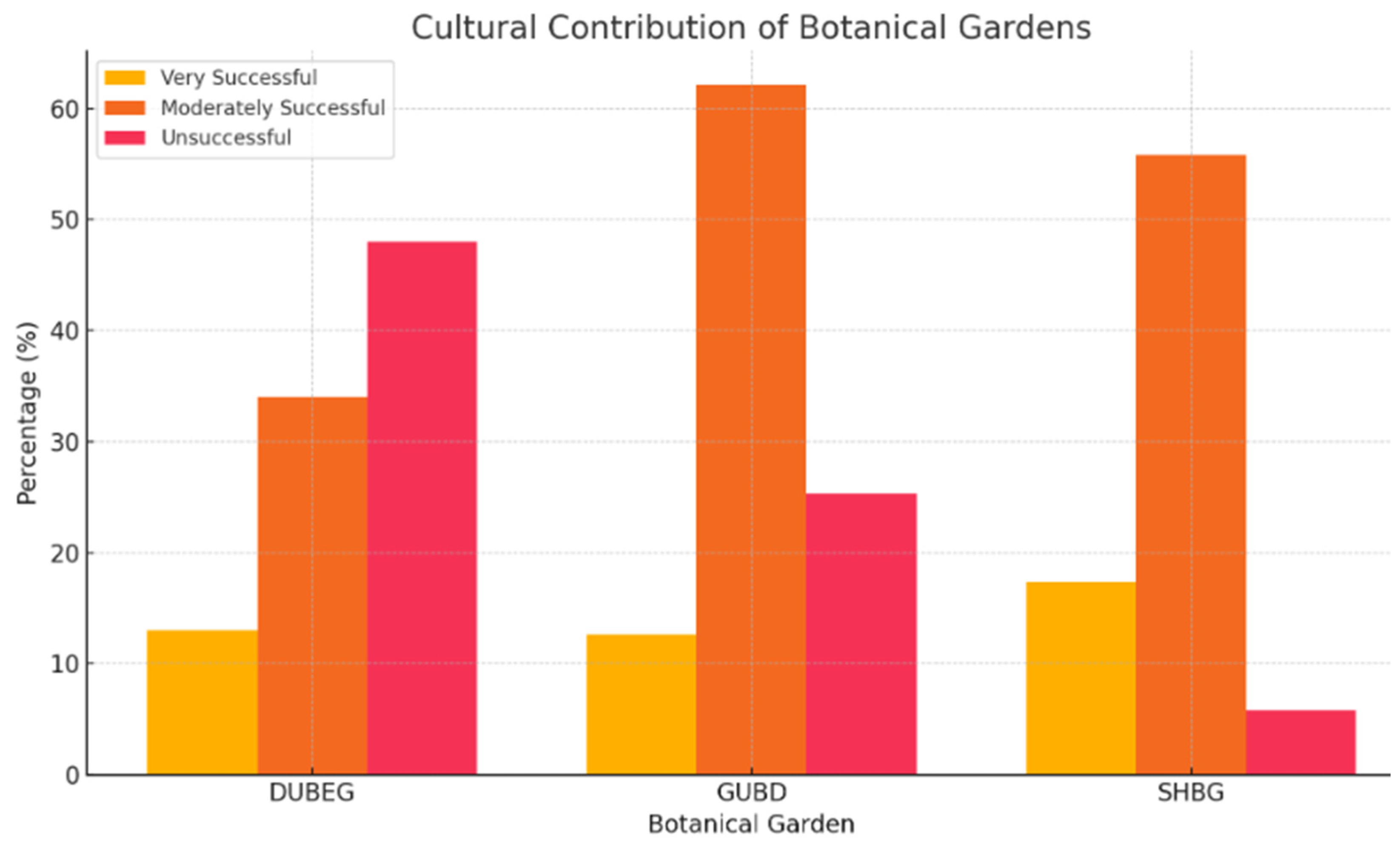

3.4.4. Cultural Contribution of Botanical Gardens

Botanical gardens play a vital role in conserving both plant biodiversity and the cultural heritage linked to it, acting as living repositories for Indigenous knowledge (Dunn, 2017). In Ethiopia, this includes safeguarding culturally important species such as Enset and native coffee. In this study, cultural integration efforts varied among the three gardens. A Chi-square test showed a significant association between the garden and perceived cultural contribution (χ² (4) = 13.85, p = 0.008).

Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG) emerged as the leader with 73.2% of respondents (combining Very and moderately successful) recognizing its strong cultural contributions. This reflects its mandate for ethno botanical research. As one community elder noted, SHBG is the only place that asks us about the uses of our local plants; they are trying to keep our traditions alive. This active collaboration with local communities helps explain the garden’s high performance.

Table 6.

Cultural Contribution of Botanical Gardens.

Table 6.

Cultural Contribution of Botanical Gardens.

| Botanical Garden |

Very Successful (%) |

Moderately Successful (%) |

Unsuccessful (%) |

Std.Dev (%) |

P-value (%) |

| SHNG |

17.4 |

55.8 |

5.8 |

6.4 |

0.022 |

| GUBG |

13.0 |

34.0 |

48.0 |

7.3 |

0.040 |

| DUBEG |

12.6 |

62.1 |

25.3 |

5.8 |

0.019 |

Figure 5.

Cultural Contribution of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

Figure 5.

Cultural Contribution of Botanical Gardens. Source: Survey Questions.

Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) also shows strong performance, with 75.1% of respondents recognizing its cultural contributions. However, its urban location may limit direct engagement with the source communities of some Indigenous knowledge. Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) faces greater challenges, with only 46.6% positive ratings, reflecting limited resources for structured cultural programs and community outreach. These findings highlight that successful cultural integration is not automatic. It relies on targeted strategies, adequate resources, and genuine partnerships with local communities. Strengthening these areas is essential for botanical gardens to fully serve as custodians of Ethiopia’s bicultural heritage.

3.4.5. The Contribution of Botanical Gardens to Health and Well-Being

Botanical gardens play a vital role in promoting community health through the conservation of medicinal plants, a role increasingly recognized worldwide in response to the rising demand for sustainable healthcare and traditional medicine (Sobrevila, 2008). In Ethiopia, where approximately 80% of the population relies on traditional medicine, botanical gardens like Gullele, Shashemene, and Dilla University have significant potential to support health and well-being by preserving medicinal plant diversity and associated indigenous knowledge.

The gardens’ differing performance reflects variations in institutional capacity and operational effectiveness, which also shape their ability to function as green spaces that promote mental and physical well-being by reducing stress and encouraging physical activity and social interaction (Aldous, 2015).

According to

Table 7, Dilla University Botanical and Ecotourism Garden (DUBEG), rated low in success and facing operational challenges, may underperform in delivering health benefits to local communities. In contrast, Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG), with higher success, likely provides stronger health-supportive services through better infrastructure, programming, and community engagement that promote outdoor recreation, environmental education, and psychological restoration (Pretty et al., 2005; Wassenberg et al., 2015).

Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG), with moderate performance, shows potential that could be improved by strengthening cultural integration and ethno botanical education. Exposure to botanical gardens and similar natural environments is linked to lower blood pressure, reduced cortisol, improved mood, and faster recovery from mental fatigue (Ulrich & Parsons, 1992; Bennett & Swasey, 1996). These benefits help reduce risks of chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and mental disorders, which are growing concerns in developing countries like Ethiopia.

Enhancing the operational capacity of all gardens, especially underperforming ones, offers multiple benefits for conservation, education, and public health. Investments in governance, infrastructure, and inclusive community programs can strengthen conservation outcomes while improving social cohesion, mental health, and physical well-being. By positioning botanical gardens as multifunctional platforms, Ethiopia can advance biodiversity conservation and public health together, contributing to a more resilient and sustainable society.

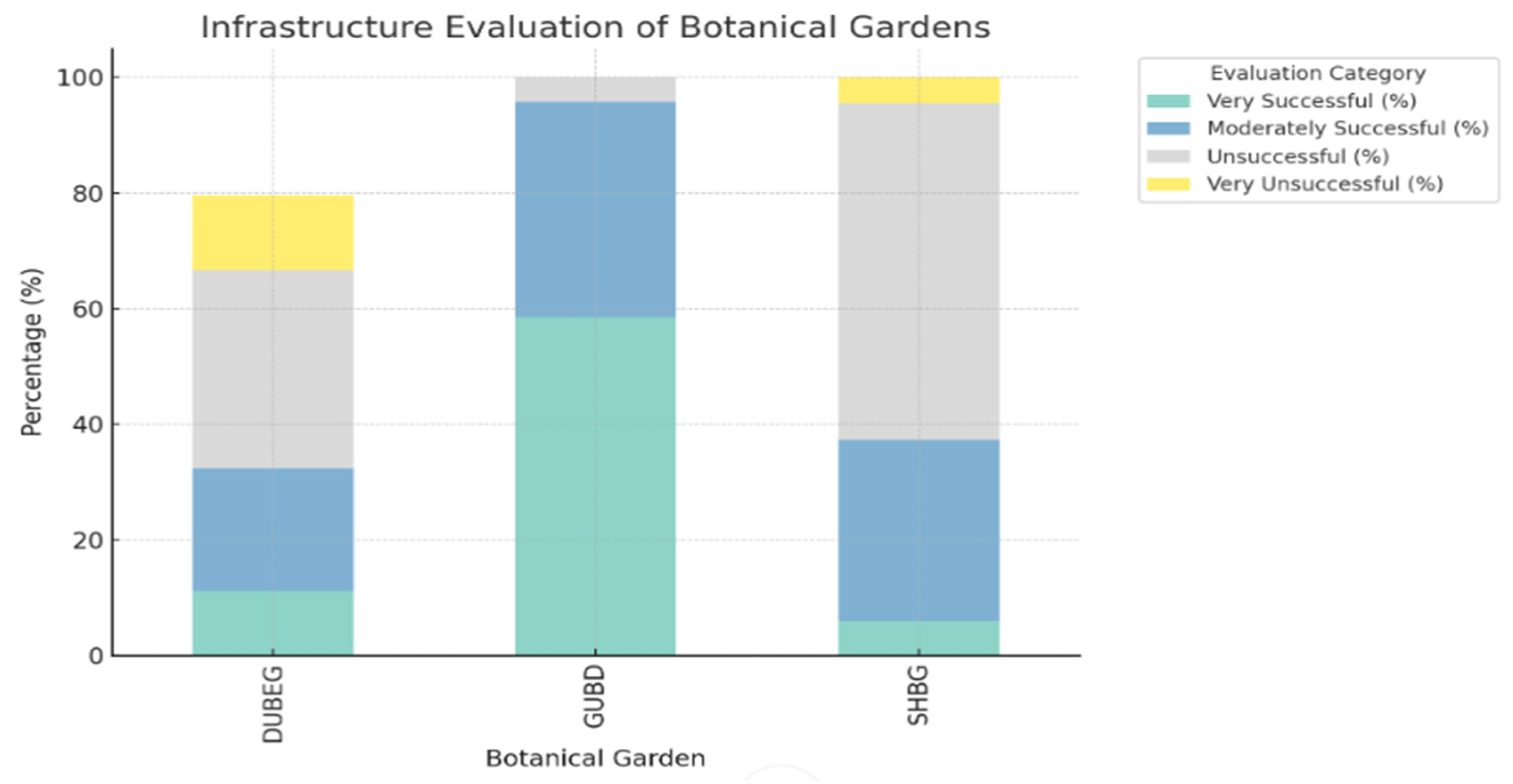

3.4.6. The Status of Development Facilities and Infrastructure

Infrastructural development determines the effectiveness of botanical gardens, particularly in areas such as visitor engagement, conservation, education, sustainability, community involvement, and operational efficiency (Neves, 2024; Richardson et al., 2016). This study evaluated the effectiveness of botanical gardens in enhancing infrastructure across three study areas DUBEG, GUBD, and SHBG based on the percentage distributions of success categories.

Statistical analyses, including ANOVA and Chi-square tests (

Table 8,

Figure 6) revealed significant differences in infrastructure development among Ethiopia’s botanical gardens. Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) had the highest infrastructure quality, with strong alignment between stakeholder perceptions and measured standards. Its well-developed facilities access roads, parking, gates, fencing, research and administrative buildings, gardens, greenhouses, and visitor services support multifunctional roles in conservation, research, and public engagement (Seta & Belay, 2021). This success is attributed to effective leadership, consistent funding, and strong stakeholder collaboration.

Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) has more modest infrastructure, including a paved road, visitor facilities, a meeting hall, nursery, thematic garden, and a research lab under construction. Survey results indicated 21.21% rated DUBEG as moderately successful and 34.34% as unsuccessful, reflecting limited investment, weak institutional commitment, and low community engagement.

Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG), despite having a gene bank, plant nursery, thematic gardens, a forest species restoration site, and research facilities, ranked lowest in infrastructure. Most respondents (58.21%) rated its facilities as inadequate, highlighting substantial gaps. Overall, infrastructure strongly affects botanical garden effectiveness, with performance varying due to differences in governance, funding, and urban integration. Strengthening infrastructure through increased investment, policy support, and stakeholder collaboration is crucial for transforming these gardens into vibrant hubs for conservation, education, and community development.

4. Discussion

This study offers a comprehensive evaluation of three major Ethiopian botanical gardens, highlighting their unique contributions to socio-ecological resilience. The findings show that governance and infrastructure are key drivers of institutional effectiveness.

4.1. Governance and Infrastructure as the Foundations of Resilience

Our findings strongly support H1, establishing governance and infrastructure as foundational pillars of botanical garden performance in Ethiopia. The collaborative governance between Addis Ababa City Administration and Addis Ababa University gives GUBG a clear advantage in strategic coherence, resource mobilization, and operational stability.

This polycentric model, where multiple governing bodies interact, enhances adaptability and problem-solving capacity, as predicted by SES (Socio-Ecological Systems) theory (Ostrom, 2010; McGinnis & Ostrom, 2014). In contrast, fragmented mandates and financial dependency at SHBG (under EBI) and DUBEG (under the university) create operational inertia and strategic ambiguity, a common challenge in the Global South where environmental institutions often work in silos and compete for limited resources (Neves, 2024; Bennett & Satterfield, 2018).

Infrastructure emerged as the strongest predictor of performance (Odds Ratio = 3.32), highlighting its critical enabling role. Well-maintained facilities including labs, greenhouses, visitor centers, and irrigation systems are essential for research, education, conservation, and recreation (Richardson et al., 2016). Deficits at SHBG and DUBEG limit their capacity to fulfill mandates, attract visitors and researchers, and adapt to challenges like climate-driven conservation and evolving educational needs. This aligns with evidence across Africa identifying inadequate infrastructure as a key constraint on conservation effectiveness (Maunder et al., 2021).

4.2. Policy Alignment and Functional Specialization

A notable finding is the distinct functional profile of each garden, reflecting an unconscious niche differentiation shaped by institutional affiliation, location, and historical mandate.

GUBG serves as an urban socio-ecological hub, leveraging proximity to the capital to excel in education and recreation functions that directly support SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

DUBEG operates primarily as an academic-conservation center, using its university connections to drive research on endemic species such as enset and coffee, contributing to SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

SHBG functions as a bicultural heritage center, with strength in cultural integration derived from its federal ethno botany mandate and engagement with local knowledge holders, supporting SDG 15 and the preservation of Indigenous knowledge.

Rather than treating these differences as imbalances, a strategic national policy could formalize and support this specialization within a collaborative network. This approach would allow each garden to deepen its comparative advantage while ensuring the network collectively covers all essential functions urban engagement, research, and bicultural preservation. This aligns with resilience thinking, which emphasizes functional diversity as a source of systemic strength (Folke et al., 2016).

4.3. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge for Bicultural Resilience:

Societal and Cultural Impacts

Botanical gardens play a vital role in supporting community well-being, cultural identity, and environmental awareness. They provide peaceful green spaces for relaxation, which help people lower stress and improve mental health. Educational programs and cultural events, such as workshops, school visits, art exhibitions, and traditional knowledge sharing, bring people together and foster social ties. These activities help communities connect with nature and with each other, building a sense of belonging and pride (Chen & Sun, 2018; Rakow & Lee, 2011).

In Ethiopia, botanical gardens act as living museums, preserving not only plant varieties but also centuries of indigenous wisdom about land stewardship and plant usage. By actively involving local elders, youth, and community members in garden planning and programming, these institutions bridge generations and strengthen cultural heritage. For example, gardens that invite elders to share stories and knowledge about medicinal plants, or that work with schools to teach children about Ethiopia’s biodiversity, make conservation personal and relevant (Fashing et al., 2022; Thomas & Löhne, 2014; Yaynemsa, 2023).

Botanical gardens also contribute economically by generating jobs and attracting visitors, which supports local businesses. Their presence can make neighborhoods more beautiful and desirable, often resulting in increased property values and investment in local areas. The gardens’ focus on sustainability encourages residents to adopt eco-friendly practices, such as recycling, water conservation, and planting native species (Godefroid et al., 2024; Science Publishing Group, 2025).

A Critical Imperative

Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG)’s exceptional leadership in cultural integration, reflected in its high score of 4.7, stands as a compelling example for conservation efforts in Ethiopia’s diverse landscape. This achievement underscores that effective and sustainable conservation is deeply intertwined with Ethiopia’s rich bio-cultural diversity (Yaynemsa, 2023; Dunn, 2017).

The garden’s active incorporation of Indigenous knowledge extends well beyond documenting plant uses; it cultivates community ownership, enhances the cultural relevance of conservation initiatives, and improves outcomes by embracing locally adapted, enduring practices and endemic species (Sobrevila, 2008; Winter et al., 2023; Garnett et al., 2018). Conversely, the lower performance in this crucial domain at Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG), with its urban context and possible detachment from rural knowledge systems, and the academically focused Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) highlights a broader missed opportunity. These gaps risk alienating local communities, thereby undermining the gardens’ long-term social legitimacy and operational effectiveness.

4.4. Addressing the Underutilized Health Nexus

Across all examined gardens, low scores in the health domain reveal a largely unexploited role of botanical gardens in promoting physical and mental health in Ethiopia. This oversight comes amid mounting global evidence that access to green spaces yields significant health benefits, including reduced stress and improved psychological well-being (Bratman et al., 2019; Twohig-Bennett & Jones, 2018).

Given that approximately 80% of Ethiopia’s population relies on traditional medicinal plants (Kloos et al., 2022), botanical gardens have considerable potential to develop targeted healing gardens, structured medicinal plant conservation programs, and actively promote nature-based therapies and passive recreation. Doing so would align garden activities with Sustainable Development Goal 3 on good health and well-being, strengthening the gardens’ social value and underpinning robust arguments for investment from both environmental and public health sectors.

4.5. Policy and Management Recommendations

This study underscores the urgent need for enhanced national coordination to enable Ethiopian botanical gardens to fulfill their vital socio-ecological roles. Establishing a unified national policy framework complemented by a dedicated Botanical Garden Strategy and Action Plan can mitigate fragmented governance structures and solidify clear institutional mandates, aligning with international best practices (Rakow & Lee, 2011; Neves, 2024).

Strengthening financial sustainability is critical; this can be achieved through diversified funding streams including public private partnerships, ecosystem service payments such as carbon credits (Pagiola et al., 2016; Sekhran & Matzke, 2019), government budget allocations, and dynamic ecotourism and philanthropic initiatives designed to deepen public engagement (Wyse Jackson & Sutherland, 2000). Investments targeted at research infrastructure, exhibition facilities, and visitor amenities are imperative to close operational gaps and bolster climate education and conservation efforts, especially in developing-country contexts (Godefroid et al., 2011; Chen & Sun, 2018).

Equally important is fostering inclusive governance by integrating Indigenous knowledge holders into decision-making processes, adhering to ethical principles such as Free, Prior, and Informed Consent under the Nagoya Protocol (UN CBD, 2011). This approach enhances community trust and embeds botanical gardens within the broader socio-ecological fabric (Berkes, 2018).

Finally, the establishment of a National Botanical Garden Network in Ethiopia would facilitate collaboration, staff training, joint research, and coordinated advocacy, drawing on successful models from global counterparts (BGCI, 2020; Donaldson, 2009). Collectively, these measures would enhance the socio-ecological performance of Ethiopian botanical gardens and amplify their contributions to biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and sustainable community development.

4.6. Research and Education Roles

Despite infrastructural challenges, Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) leads in research output with a score of 4.0, highlighting the crucial role universities play in advancing botanical science (Chen & Sun, 2018). The vibrant academic community at Dilla University sustains a steady flow of researchers and students focused on endemic and socio-economically major species like enset and coffee. This aligns well with botanical gardens’ conservation priorities, demonstrating how strong institutional research mandates can overcome physical limitations to produce impactful results (Sharrock & Jones, 2009).

In contrast, Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG) excels in education, scoring 4.5 due to extensive outreach initiatives that boost environmental literacy. Its location in Ethiopia’s capital and carefully structured programs, such as guided tours serving thousands of students, enable GUBG to be a key channel for engaging the public in sustainability education efforts proven to enhance knowledge and foster positive environmental attitudes (Zelenika et al., 2018).

Strengthening these complementary strengths across all gardens could significantly amplify their conservation impact. For instance, bolstering SHBG’s research infrastructure would allow for better documentation of ethno botanical knowledge. Similarly, developing formal educational programs at DUBEG would facilitate wider dissemination of its research to the public, making science accessible and actionable.

4.7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of Ethiopian botanical gardens but has some limitations that suggest directions for future work. First, the focus on three large, well-established gardens limits the overall view. Future research could include smaller or emerging gardens and herbaria to offer a fuller national picture.

Second, this study captures a single point in time. Longitudinal research is needed to follow these gardens’ performance and resilience over months or years, especially as policies change or climate events occur. Third, though we identified key predictors of success, future studies should use advanced methods like Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to better understand the causal relationships among socio-ecological factors.

Finally, more in-depth research is needed on specific issues. This includes socio-economic studies of funding models for gardens in Ethiopia and participatory action research to develop ethical ways to include Indigenous knowledge in garden governance and programming

5. Conclusions

This study reveals that Ethiopian botanical gardens stand at a critical crossroads. They have immense yet underutilized potential to serve as anchors of socio-ecological resilience, linking national policy goals with local community needs. The notable differences in performance among Gullele Botanical Garden (GUBG), Shashemene Botanical Garden (SHBG), and Dilla University Botanical Garden (DUBEG) make it clear that institutional success relies on strong, adaptive governance and well-maintained infrastructure.

While specialization in certain functions is promising, it should be nurtured strategically through a supportive national framework not simply emerge from scarcity or isolation. To truly transform these gardens, a shift guided by socio-ecological system (SES) thinking is essential: from isolated plant collections to dynamic, integrated, and resilient socio-ecological systems.

Addressing fragmented governance, funding shortfalls, and infrastructure gaps, alongside genuine community partnerships and the ethical inclusion of Indigenous knowledge, can unlock their full potential. These gardens could then become vital multifunctional platforms, crucial for tackling sustainable land use, biodiversity conservation, climate adaptation, and public health challenges facing Ethiopia in the 21st century.

List of Abbreviations

BG Botanical Garden

DUBEG Dilla University Botanical and Ecotourism Garden

GUBG Gullele Botanical Garden

SHBG Shashemene Botanical Garden

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

CRGE Climate-Resilient Green Economy

NBSAP National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

ANOVA Analysis of Variance

Declaration

We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published elsewhere, and is not under consideration for publication. All authors approve its submission

Author Contributions

GH contributed to the design of the study, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript write-up. HK contributed by reviewing the manuscript and providing comments and suggestions.GH also contributed by reviewing the manuscript and providing comments and suggestions.MM contributed by reviewing the manuscript and data collection. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and consent to its publication.

Funding

This research was funded by Dilla University. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Dilla University. All participants provided informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed, and data was stored securely.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dilla University for providing the research grant. We also extend our sincere gratitude to the management and staff of Gullele, Shashemene, and Dilla University Botanical Gardens, as well as all the survey respondents and interview participants for their valuable time and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Argaw, T. (2015). Opportunities of botanical garden in environmental and development education to support school based instruction in Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 5(15), 92–110.

- Aronson, M. F., La Sorte, F. A., Nilon, C. H., Katti, M., Goddard, M. A., Lepczyk, C. A., Warren, P. S., Williams, N. S., Cilliers, S., Clarkson, B., & Dobbs, C. (2014). A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1780), 20133330.

- Asefa, M., Cao, M., He, Y., Mekonnen, E., Song, X., & Yang, J. (2020). Ethiopian vegetation types, climate and topography. Plant Diversity, 42(4), 302–311.

- Berkes, F., & Folke, C. (Eds.). (1998). Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, G., & Sun, W. (2018). The role of botanical gardens in scientific research, conservation, and citizen science. Plant Diversity, 40(4), 181–188.

- Chen, G., & Sun, W. (2018). The role of botanical gardens in scientific research and community well-being.5.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dunn, C. P. (2017). Biological and cultural diversity in the context of botanic garden conservation strategies. Plant Diversity, 39(6), 396–401.

- Fashing, N. et al. (2022). Integration of Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Ethiopian Botanical Gardens.

- Fashing, P. J., Nguyen, N., Demissew, S., Gizaw, A., Atickem, A., Mekonnen, A., Nurmi, N. O., Kerby, J. T., & Stenseth, N. C. (2022). Ecology, evolution, and conservation of Ethiopia’s biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(50), e2206635119.

- Godefroid et al. (2024). Constraints on botanical garden efficacy in Ethiopia.

- Godefroid, S., Rivière, S., Waldren, S., Boretos, N., Eastwood, R., & Vanderborght, T. (2011). To what extent are threatened European plant species conserved in seed banks? Biological Conservation, 144(5), 1494–1498.

- Jackson, P. W., & Kennedy, K. (2009). The global strategy for plant conservation: A challenge and opportunity for the international community. Trends in Plant Science, 14(11), 578–580.

- Mohammed, A. (2021). The legal framework and barriers to access to environmental information in Ethiopia. [Missing Journal Name], 15(1).

- Mounce, R., Smith, P., & Brockington, S. (2017). Ex situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens. Nature Plants, 3(10), 795–802.

- Neves, K. G. (2024). Botanic gardens in biodiversity conservation and sustainability: History, contemporary engagements, decolonization challenges, and renewed potential. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 5(2), 260–275.

- Rakow, D., & Lee, S. (2011). Public garden management: A complete guide to the planning and administration of botanical gardens and arboreta. John Wiley & Sons.

- Richardson, M., Frediani, K., Manger, K., Piacentini, R., & Smith, P. (2016). Botanic gardens as models of environmental sustainability: Managing environmental sustainability in times of rapid global change. In From idea to realisation: BGCI’s manual on planning, developing and managing botanic gardens (pp. 226–239). Botanic Garden Conservation International (BGCI).

- Schleicher, J., Peres, C. A., Amano, T., Llactayo, W., & Leader-Williams, N. (2017). Conservation performance of different conservation governance regimes in the Peruvian Amazon. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11318.

- 20. Science Publishing Group (2025). Biodiversity and ecosystem services in Ethiopian botanical gardens.

- Seta, T., & Belay, B. (2022). BOTANIC GARDEN PROFILE Gullele botanic garden, Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Current status, challenges and opportunities. Sibbaldia: The International Journal of Botanic Garden Horticulture, (21), 13–34.

- Sobrevila, C. (2008). The role of indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation: The natural but often forgotten partners (No. 44300). The World Bank.

- Thomas Borsch & Cornelia Löhne (2014). Botanic Gardens for the Future: Conservation and Cultural Heritage.

- Waylen, K. (2006). Botanic gardens: Using biodiversity to improve human wellbeing. Medicinal Plant Conservation, (12), 4–8.

- Winter, K., Vaughan, M., Kurashima, N., Wann, L., Cadiz, E., Kawelo, A. H., Cypher, M., Kaluhiwa, L., & Springer, H. (2023). Indigenous stewardship through novel approaches to collaborative management in Hawaiʻi. [Missing Journal Name, Volume, and Pages].

- Wyse Jackson, P. S., & Sutherland, L. A. (2000). International agenda for botanic gardens in conservation. [No Publisher/Journal provided].

- Yaynemsa, K. G. (2023). Plant biodiversity conservation in Ethiopia: A shift to small conservation reserves. Springer Nature.

- Yaynemsa, T. (2023). Community participation and adaptation strategies in Ethiopian gardens.

- Zelenika, I., Moreau, T., Lane, O., & Zhao, J. (2018). Sustainability education in a botanical garden promotes environmental knowledge, attitudes and willingness to act. Environmental Education Research, 24 (11), 1581–1596.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).