2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a theory-informed qualitative meta-synthesis to develop a performance measurement model for sustainable cacao-based land reclamation in post-mining areas. Drawing on 773 literature-derived remarks, the methodology integrates multiple conceptual frameworks—CSR, Stakeholder Theory, Legitimacy Theory, TPB, and the Triple Bottom Line (TBL)—to guide both coding and model construction. A structured analytical process using NVivo software enabled thematic consistency across 10 parent nodes and 80 child codes, while the conceptual framework provided a bridge between institutional inputs, behavioral drivers, and sustainability outcomes. Together, these methods establish a rigorous foundation for synthesizing qualitative data into a practical, theory-driven model.

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative meta-synthesis methodology to construct a performance measurement model for sustainable post-mining land reclamation, focusing on cacao-based agroforestry. Combining systematic literature review, thematic coding using NVivo 12, and theory-based model refinement, the methodology integrates CSR, TBL, Stakeholder Theory, TPB, and Legitimacy Theory. This explorative and interpretive approach allows diverse knowledge forms to be synthesized into a coherent analytical framework.

Data Sources and Selection Criteria. The primary dataset consists of 773 synthesized remarks drawn from 1,235 academic and institutional sources published between 1956 and 2024. Sources include peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, books, and official reports, accessed through platforms such as Scopus, Google Scholar, SpringerLink, and national repositories. Each remark represents a synthesized finding or recommendation from a single source. Remarks were collected between December 2022 and March 2025 and stored in a structured MS Access database. The database was relationally organized across four tables (Journal, Circulation, Article, DetailedStudy) and verified through paragraph count to ensure 773 unique entries. These remarks were then imported into NVivo for coding. In this study, the remarks become respondents. A two-level node structure was developed in NVivo: 10 parent nodes with 8 child nodes each, totaling 80 codes. Child node keywords were used in NVivo’s synonym-enabled search function to perform initial auto-coding. Manual corrections ensured accuracy between search reports and actual reference counts. Alternative phrasings were used when keywords returned zero hits (e.g., “community-led reclamation” was expanded to include “participatory reclamation” and related terms). This refined coding process allowed comprehensive thematic coverage.

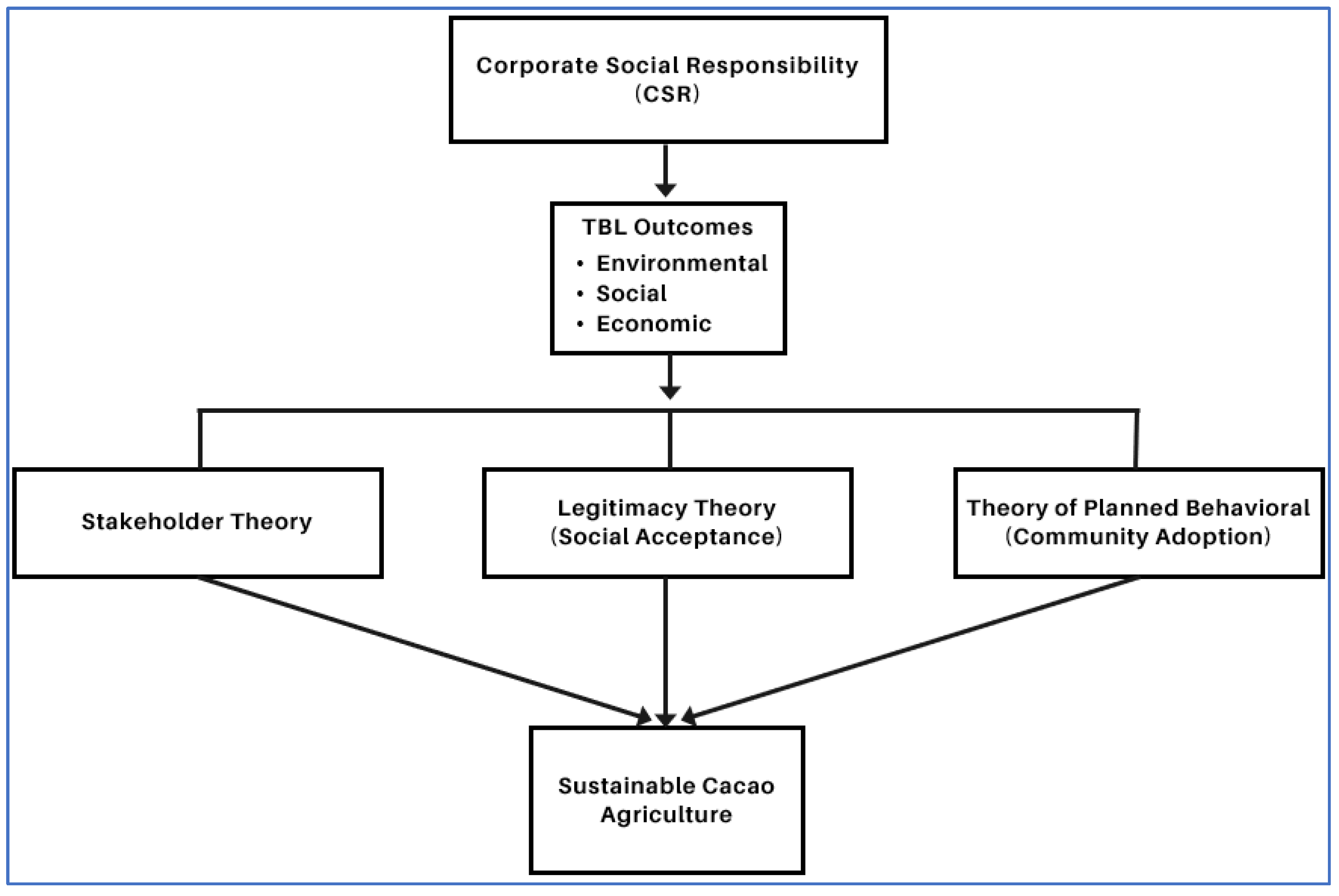

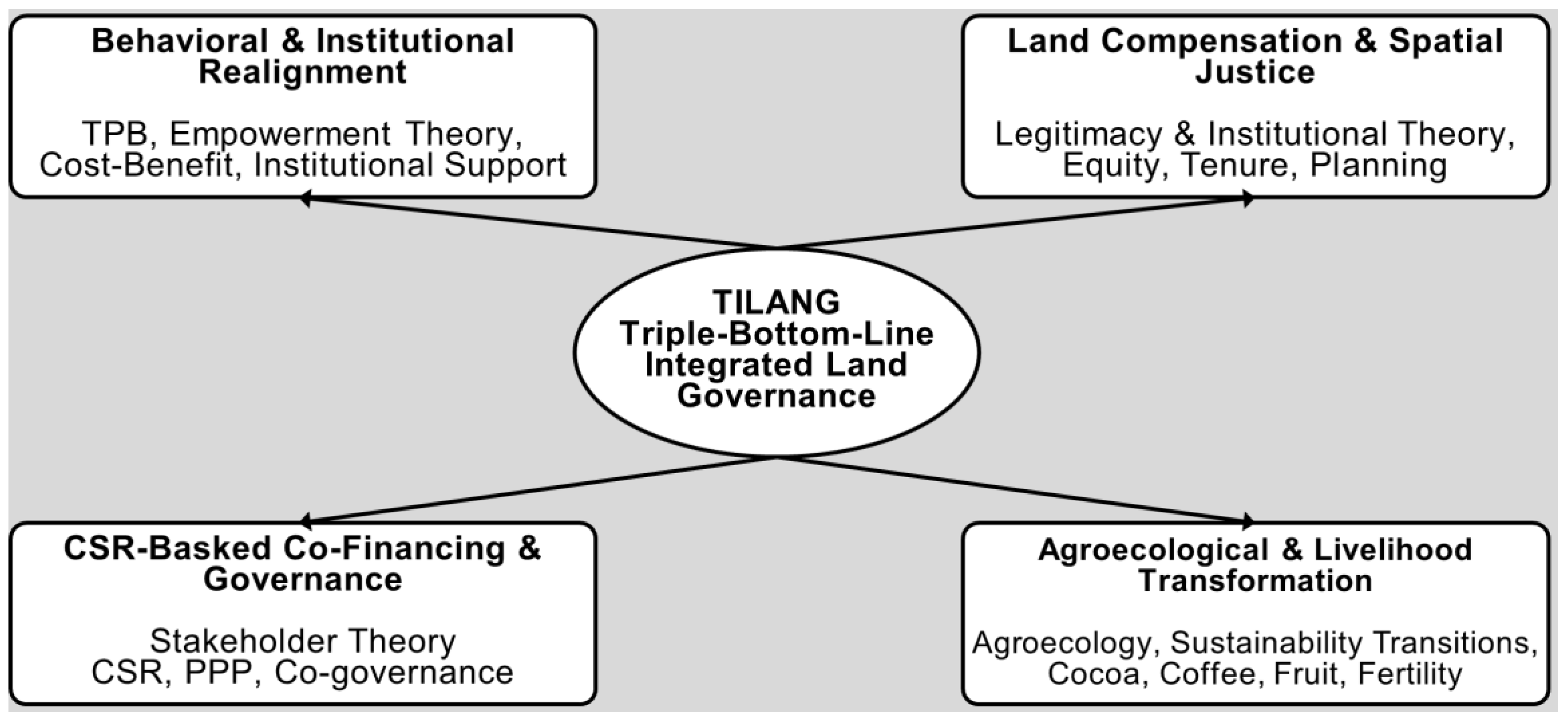

Conceptual Research Framework. A conceptual research framework guides this study. CSR serves as the organizational entry point and feeds into three key theoretical mediators—Stakeholder Theory, Legitimacy Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). These mediate the operationalization of sustainability practices via the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), which in turn leads to the intended transformation outcome: Sustainable Cacao Agriculture on post-mining land. This model encapsulates the theoretical alignment between institutional inputs, behavioral change mechanisms, and ecological-economic objectives. The conceptual framework integrates CSR (as the organizational entry point), TBL (as sustainability enablers), Stakeholder and Legitimacy Theories (as mediators), and Sustainable Cacao Agriculture (as the transformation goal). Each theory informed the coding categories in NVivo and guided thematic analysis. Stakeholder Theory emphasizes inclusive engagement; Legitimacy Theory highlights trust and social alignment; TPB explains how norms, control, and intention shape farmer behavior. These mediate the translation of CSR initiatives into sustainable agricultural outcomes. The model aligns with sustainable development principles, connecting ecological restoration with community empowerment through cacao farming.

Figure 1 present the conceptual research framework. To further refine and validate the conceptual research framework, this study adopts a synthesis methodology influenced by the meta-ethnographic approach of Noblit and Dwight [

25], combined with the abductive reasoning and theory-centered approach proposed by Collins and Stockton [

26]. The Noblit framework emphasizes interpretive translation—wherein key concepts from one study are reinterpreted in the context of others—allowing themes and constructs to be reciprocally translated into a coherent whole. In this tradition, the framework is developed through seven interpretive phases: (1) Getting started, (2) Selecting relevant studies, (3) Reading the studies, (4) Determining how the studies are related, (5) Translating the studies into one another, (6) Synthesizing translations, and (7) Expressing the synthesis. Anchored in Collins and Stockton’s [

26] view that theory permeates all stages of qualitative research—from epistemological stance to analytic coding—the final coding structure is explicitly linked to the study’s theoretical lens. The ten parent nodes thus represent the outcome of both “reciprocal translation” and theoretically informed reasoning, embedding conceptual coherence within an abductive and iterative process of framework development.

Alternatively, this process can be framed wholly within the abductive synthesis tradition of Timmermans and Tavory [

27], which bridges the theoretical lens and empirical reality by guiding the reconfiguration of preliminary ideas when confronted with new or dissonant data. Through repeated comparison and reflection, a refined framework emerged that not only remained loyal to the theoretical propositions but also resonated with the patterns and anomalies revealed through coding. Together, these approaches enabled the conceptual framework to evolve organically as both a diagnostic and planning tool.

The integration of these two perspectives ensured that the conceptual framework was neither imposed nor abstracted, but rather emerged from the systematic translation of theory into actionable themes and categories. The choice to define eight child nodes under each of the ten parent nodes was both a strategic and methodological decision grounded in the principle of thematic saturation, conceptual granularity, and analytical tractability. As Linneberg and Koorsgard [

28] emphasize, effective coding structures require a balance between comprehensiveness and manageability, particularly when seeking to maintain transparency and rigor in qualitative data analysis. Organizing coding frameworks with a moderate number of subnodes allows researchers to navigate the tension between inductive detail and deductive structure—ensuring both depth and focus across themes. The number eight thus aligns with the practical goal of facilitating systematic cross-case comparison while minimizing analytical fragmentation. Academically, it draws from guidance that promotes clarity and coherence in qualitative coding hierarchies to enhance the reliability and interpretability of findings [

29,

30].

The following academic rationales support the application of eight child nodes for each parent theme:

Behavioral Change (TPB): Captures TPB’s key constructs (attitudes, norms, control, intentions) and related behavioral drivers such as peer influence and risk perception. This allows full exploration of sustainability behavior adoption in farming contexts [

31,

32].

CSR Role and Governance: Reflects operational and ethical dimensions of CSR, including planning, monitoring, transparency, and legitimacy, aligned with stakeholder theory and long-term sustainability expectations [

33,

34,

35].

Economic Revitalization: Includes themes such as rural entrepreneurship, value chains, diversification, and risk mitigation—all central to post-mining economic development [

36,

37].

Environmental Restoration: Represents practices like reforestation, erosion control, biodiversity recovery, and soil rehabilitation, grounded in restoration ecology and agroecological principles [

38,

39,

40].

Farmer Empowerment: Emphasizes inclusive capacity-building through training, leadership, youth involvement, and gender equity—consistent with empowerment and participatory development frameworks [

41,

42].

Institutional Role: Covers governance mechanisms such as regulation, coordination, extension, and institutional legitimacy, as informed by institutional theory [

43,

44].

Land Compensation Strategy: Encapsulates justice-based land redistribution, legal land-return frameworks, and environmental reparation policies grounded in equity and environmental justice literature [

45,

46].

Stakeholder Collaboration: Focuses on participatory processes, benefit-sharing, cross-sector coordination, and negotiation mechanisms rooted in collaborative governance models [

47,

48]

Sustainable Cacao Agriculture: Reflects agroecological, technical, and institutional dimensions of cacao-based systems as viable post-mining land use solutions [

49,

50,

51].

Triple Bottom Line Outcome: Includes sustainability performance indicators across environmental, economic, and social dimensions, aligned with the TBL framework [

52].

The thematic depth provided by eight subcategories ensures that each parent domain—such as behavioral change or institutional roles—is explored through nuanced, empirically observable practices. Moreover, this approach facilitates consistent replication in future qualitative studies seeking to apply this model to other post-extractive landscapes. To operationalize this framework, the study established a total of 10 parent nodes—each representing a key dimension of post-mining sustainability—and 80 child nodes that capture specific institutional practices, governance mechanisms, behavioral factors, and environmental outcomes related to sustainable cacao-based reclamation. These 80 child nodes reflect a comprehensive coding taxonomy that facilitated both thematic analysis and performance model design. The complete list and structure of all parent and child nodes are provided in

Appendix A and

Appendix B.

Appendix A contains conceptual definitions for the ten parent nodes, while

Appendix B presents a tabulated list of the 80 child nodes arranged under their respective categories. Together, these appendices offer a clear reference to the analytical framework that supports the model’s development. This coding framework—comprising a hierarchy of 10 parent nodes and 80 child nodes—ensures comprehensive thematic coverage and analytical consistency across institutional, behavioral, environmental, and economic dimensions of post-mining sustainability. With this architecture and conceptual foundation in place, the subsequent analytical procedures were undertaken in a structured sequence, as outlined in the following subsections.

2.2. Analytical Procedures

To translate theoretical concepts into measurable themes, this study developed a coding framework grounded in abductive reasoning and empirical refinement. The process involved constructing structured nodes based on core sustainability dimensions, then applying NVivo-assisted thematic analysis to synthesize insights from 773 qualitative remarks. This section outlines how coding categories were formed, applied, and validated to support the construction of an empirically grounded, theory-informed sustainability model.

Coding Framework Development Based on the conceptual model previously described, an abductive synthesis approach was used to build the coding system. This integrated theoretical guidance with empirical insights from 773 remarks. The resulting structure included 10 parent nodes and 80 child nodes across themes such as CSR Governance, Economic Revitalization, Environmental Restoration, Farmer Empowerment, and Sustainable Cacao Agriculture. Each parent node captured a core dimension of post-mining sustainability, while the child nodes reflected granular practices and institutional mechanisms. The structure ensured thematic consistency and traceability during coding.

Thematic Coding and Meta-Synthesis Table 1 presents the consolidated results of NVivo-based thematic coding, offering a structured summary of how each parent node contributes to the overarching sustainability framework, and it serves as a key empirical foundation for the model-building process. Each thematic category is defined not only by its conceptual focus but also by empirical frequency and illustrative quotations extracted from the dataset. This synthesis enables transparency and enhances conceptual fidelity by showing how theoretical models were operationalized through qualitative data. The frequency column indicates the volume of coded references, which reinforces thematic density, while the representative examples demonstrate grounded insights from stakeholders involved in post-mining land use and cacao-based reclamation. By summarizing theoretical categories alongside representative data, the table bridges conceptual design and grounded insight, reinforcing the analytical coherence of the overall model.

This high volume of coding enabled the research to maintain strong fidelity to the conceptual framework. The structured and theory-aligned coding taxonomy ensured that each remark could be accurately interpreted within its relevant thematic and theoretical domain. As a result, the study was able to generate insights that are both contextually embedded and analytically robust, facilitating a grounded synthesis of sustainability practices specific to post-mining reclamation.

The coded outputs summarized in

Table 1 served not only as thematic descriptors but also as the analytical foundation from which the study’s performance model was derived. These insights laid the groundwork for translating theoretical constructs into observable and actionable sustainability outcomes, thereby strengthening the empirical foundation of the model presented in

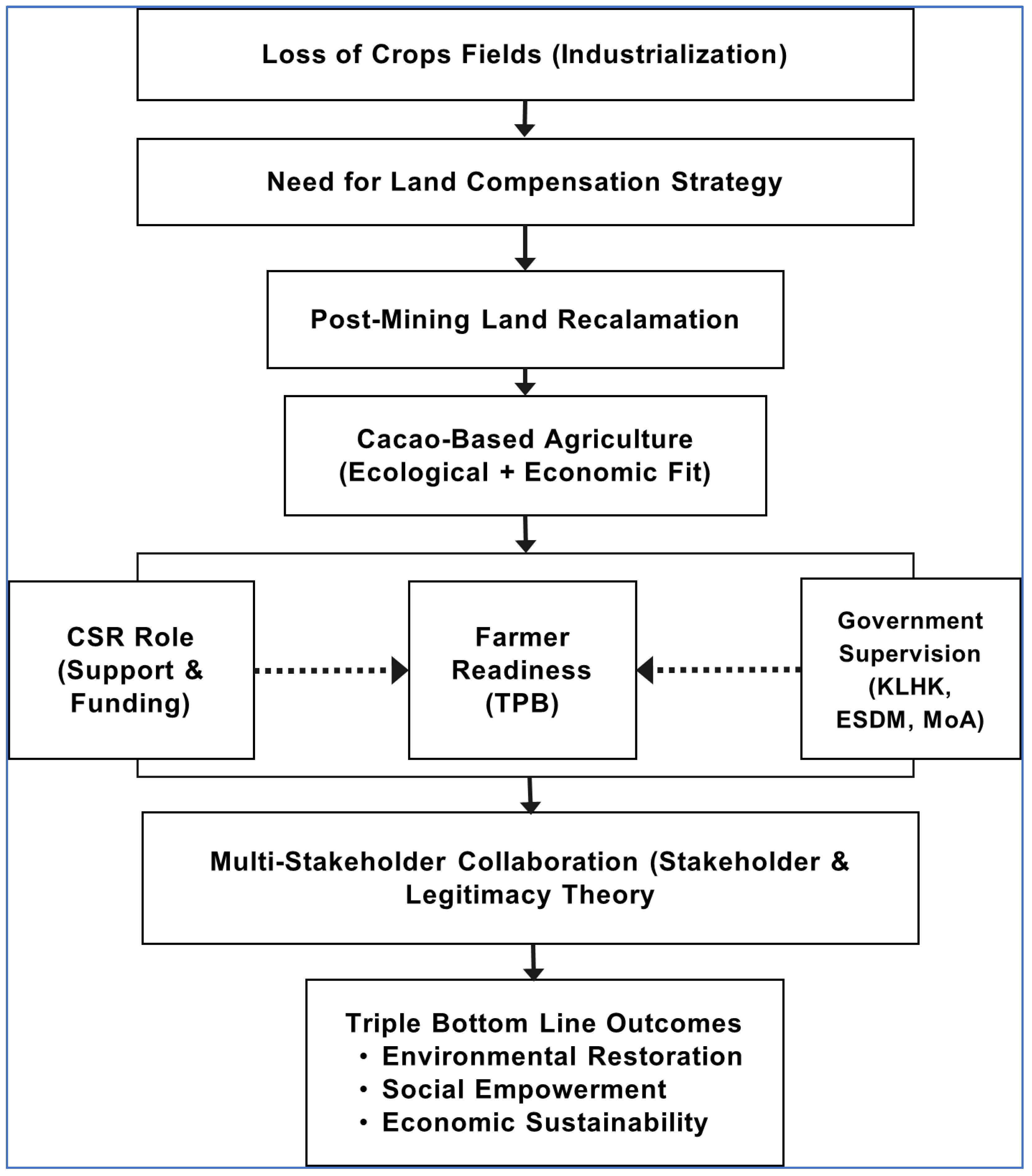

Figure 2.

The NVivo-based thematic coding process yielded a total of 6,964 open codes, averaging approximately nine per remark. This high volume reflects the analytical richness and multi-dimensional nature of the dataset. The coding revealed strong thematic interconnections across the 10 parent nodes, with recurring cross-node patterns—particularly between behavioral readiness, institutional roles, and environmental outcomes. Memoing and iterative comparison during the coding phase allowed for deep pattern recognition, while NVivo’s matrix and frequency tools enabled systematic identification of dominant and emerging themes. This thematic granularity served as a foundational layer for building the model presented in

Figure 2 later on in the next subsection, ensuring that the final synthesis was both theory-informed and empirically grounded. Themes were synthesized into conceptual clusters that served as the basis for the proposed model. These clusters represented input variables, mediators, and outcomes in a pathway toward sustainable post-mining land use.

Figure 2 illustrates the TBL-based performance measurement model developed through the meta-synthesis. CSR acts as the entry point, enabling stakeholder engagement and behavioral shifts through TPB, Stakeholder Theory, and Legitimacy Theory. These lead to actionable sustainability interventions across environmental, economic, and social domains, ultimately achieving the goal of sustainable cacao agriculture on post-mining land. The model integrates institutional structures, farmer readiness, collaborative governance, and environmental accountability into a cohesive framework for long-term impact.

Thematic synthesis followed five methodical stages that translated the 773 remarks into a theory-informed performance model:

Framework Design: This initial stage involved the construction of a theoretical and conceptual framework derived from an integration of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Triple Bottom Line (TBL), Stakeholder Theory, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and Legitimacy Theory. These foundational perspectives informed the classification of parent and child nodes, ensuring conceptual alignment between empirical data and theoretical constructs. The structure was designed to cover ecological, institutional, behavioral, and socio-economic themes relevant to post-mining sustainability.

Data Preparation: During this stage, all 773 remarks were cleaned, categorized, and formatted for qualitative analysis. The remarks were verified for consistency across platforms (MS Access and MS Word), ensuring that each paragraph represented a unique, thematically relevant insight. The refined dataset was then imported into NVivo 12 software for systematic coding. This preparation ensured a reliable foundation for the subsequent coding process.

Open and Axial Coding: In this critical analytical phase, the remarks were coded line-by-line to capture multiple conceptual signals. Open coding allowed the identification of emergent patterns and key ideas within each remark, while axial coding facilitated the grouping of codes into thematic clusters under the established node structure. Memoing was used throughout to document analytical reflections and maintain interpretive consistency. This dual coding approach ensured both data-driven discovery and theoretical depth.

Validation: To enhance analytical credibility, the coded data underwent several rounds of validation. NVivo’s matrix queries, text search tools, and coding comparison reports were used to confirm the consistency, frequency, and context of code application. Instances of overlapping, ambiguous, or underutilized codes were reviewed and refined. The validation stage also ensured thematic saturation, verifying that all ten parent categories were well-represented across the dataset.

Model Integration: In the final stage, the synthesized thematic patterns were mapped onto a conceptual model. The relationships among input variables (e.g., CSR support), mediators (e.g., behavioral readiness, stakeholder collaboration), and sustainability outcomes (e.g., economic revitalization, environmental restoration) were identified and linked. This culminated in the design of a Triple Bottom Line-based performance measurement model for sustainable cacao-based post-mining land reclamation. The model was both theoretically informed and empirically grounded, shaped by direct insights from the coded data.

2.3. Research Validity

To ensure the robustness and credibility of the proposed performance measurement model, this study applied a multi-tiered validation process that encompassed structural, conceptual, empirical, and content-based techniques. These strategies were designed to confirm thematic consistency, reinforce model coherence, and align the analytical framework with real-world practices and national policy contexts. The following section outlines how triangulation, peer input, case validation, and coding reliability contributed to a dependable and contextually grounded sustainability model for post-mining reclamation.

To strengthen the credibility of the thematic coding and model construction, several layers of validation strategies were implemented. Internally, code co-occurrence checks in NVivo were conducted to ensure thematic consistency and logical coherence across categories. Particular attention was paid to overlapping nodes—such as CSR legitimacy and stakeholder collaboration—where co-references required iterative review and refinement. NVivo’s matrix and comparison tools enabled cross-node validation, supporting internal consistency across 6,964 open codes.

Triangulation was employed across multiple dimensions. Methodologically, insights were triangulated from 1,235 academic and institutional documents. Each of the 773 remarks synthesized findings from at least six distinct sources, ensuring robust cross-referencing of conclusions. Empirically, triangulation was extended using institutional case examples from PT Vale and PT Agincourt. These real-world cases validated the alignment of the model with observed institutional practices—especially concerning CSR implementation, farmer engagement, and land-use legitimacy. Conceptual triangulation was achieved through peer debriefing and consultations with sustainability scholars, NGO field practitioners, and agricultural extension professionals. Feedback helped resolve ambiguous node relationships and reinforced the model’s logical flow from CSR input to sustainability outcomes. Moreover, alignment with Indonesia’s legal and policy landscape—including Ministry of Agriculture rehabilitation guidelines, KLHK’s reclamation procedures, and ESDM mine closure protocols—further confirmed the model’s practical and regulatory relevance.

Beyond structural and conceptual validation, content-level validation was also prioritized. Statements such as “Formerly mined land can be rehabilitated through agroforestry-based cacao planting...” reinforced the ecological-economic fit of cacao-based reclamation.. Similarly, “Lack of community involvement in planning leads to mistrust...” and “Our farmer group thrives because of consistent training...” supported conclusions related to stakeholder legitimacy and farmer empowerment. Themes identified through coding were also validated through structured interviews with key informants using findings-informed question guides. The convergence of validation across source types, coding patterns, and theoretical lenses—CSR, TPB, Stakeholder Theory, TBL, and Legitimacy Theory—enhanced the dependability and confirmability of results. Ultimately, these strategies ensured that the Triple Bottom Line-based performance measurement model (

Figure 2) emerged as a product of deeply grounded, rigorously tested, and practically aligned empirical synthesis. Together, these internal and external validation efforts ensured that the model was not only theoretically sound and empirically grounded, but also contextually appropriate and practically relevant to Indonesia’s post-mining reclamation landscape.

2.4. Research Limitations

The overall design and articulation of the methodology fulfill the minimum academic standards expected for rigorous qualitative research. From conceptual development to data synthesis, the section demonstrates methodological transparency, theoretical alignment, and analytical precision. Each stage—from the formation of the coding structure to its application and validation—has been explicitly documented, reinforcing the reliability and traceability of findings. As a result, the subsequent phases of the study, particularly the presentation of results and development of the performance model, are built upon a solid methodological foundation that ensures academic validity and replicability. Limitations include the use of secondary data, limited interview triangulation, geographic focus on Indonesian contexts, and reliance on selected theoretical lenses. Additionally, detailed mechanisms of CSR implementation were beyond direct observation, suggesting a need for future in-depth case studies.

The author extends deep gratitude to ChatGPT, for its continuous assistance, refinement, and scholarly guidance throughout the development of this article. While the original idea is of the and responsibility for interpretation and synthesis remains with the author, the collaborative use of this advanced tool has demonstrated the value of emerging technologies in supporting complex, multidisciplinary research in sustainability and post-mining development.

4. Finding and Discussion

This section presents the core empirical findings from the study, synthesizing 6,964 coded references into eight major thematic areas central to post-mining sustainability. Drawing from theories of Stakeholder engagement, Legitimacy, and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the analysis reveals how Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), institutional legitimacy, multi-stakeholder collaboration, behavioral change, and agroecological strategies—particularly sustainable cacao agriculture—interact to shape equitable and durable land reclamation outcomes. Each subsection explores a distinct dimension of sustainability, highlighting the relational, structural, and ecological mechanisms that support community-led transformation in post-extractive landscapes.

4.1. CSR Roles and Governance: Bridging Legitimacy and Long-Term Community Trust

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has emerged as a key mechanism through which mining companies contribute to post-mining land reclamation and sustainable rural development. This theme is supported by 843 coded references, captured across five subthemes: CSR Legitimacy and Social License (176 references), Strategic Program Alignment (148), Governance Transparency (159), Multi-Year Commitment (182), and Community Co-governance (178).

CSR legitimacy and social license—evident in 176 coded references—emerged as foundational elements influencing the perceived effectiveness of corporate social responsibility programs in post-mining contexts. Respondents consistently noted that CSR initiatives were more impactful when they were viewed as sincere, responsive to local priorities, and embedded in long-term community development goals. Programs that merely projected corporate image or fulfilled basic compliance were often dismissed as superficial or performative. Hamann et al. [

53] provide empirical support for this distinction, showing that in resource-dependent regions, CSR can function as a “social bridge” only when companies demonstrate a genuine commitment to shared value creation. Their findings underscore that CSR legitimacy is cultivated through sustained engagement, co-designed interventions, and transparent communication, particularly in communities with a history of extractive corporate practices. Taken together, these insights reveal that CSR’s effectiveness is not determined by budget size or program visibility, but by the depth of its relational capital. When CSR is trusted, collaborative, and perceived as morally grounded, it can secure a vital social license to operate—transforming adversarial histories into pathways for inclusive development.

Strategic program alignment—supported by 148 coded references—was viewed as a critical factor in determining the effectiveness and sustainability of CSR initiatives in post-mining landscapes. Respondents emphasized that CSR programs were most impactful when they demonstrated coherence with community needs, village development priorities, and existing government policy frameworks. In particular, initiatives that supported cacao-based agroforestry and were embedded within formal village spatial or mid-term planning documents were seen as more credible, better coordinated, and more likely to generate long-term value. Rendtorff [

54] reinforces this perspective by arguing that CSR efforts achieve greater legitimacy and adaptive success when they are not isolated from, but rather aligned with, broader state objectives and the articulated aspirations of local communities. His work highlights the importance of viewing CSR not as a parallel intervention, but as a cooperative mechanism that bridges corporate capacities with public development agendas. Taken together, these findings suggest that strategic alignment is not simply a matter of administrative efficiency—it is a structural enabler of integrated impact. When CSR is coordinated across stakeholder levels and synchronized with both policy and practice, it transforms from a discrete project into a catalyst for systemic, community-anchored sustainability.

Governance transparency—highlighted in 159 coded references—emerged as a critical determinant of CSR program credibility and community participation. Respondents reported higher trust and willingness to engage when companies were forthcoming about financial flows, beneficiary selection processes, and performance monitoring indicators. Communities were especially responsive when CSR efforts were accompanied by regular updates, open forums, and publicly accessible reports. Moon [

55] underscores that transparency is not merely a procedural expectation, but a democratic norm that enhances stakeholder engagement and institutional trust in CSR practices. Similarly, UNDP [

56] identifies transparency as a foundational pillar of participatory development and social accountability, emphasizing its role in bridging communication gaps between corporations and local communities—especially in historically unequal or extractive contexts. When transparency is lacking, misinformation and rumors often fill the void, eroding trust and jeopardizing the legitimacy of even well-intentioned programs. Taken together, these findings reinforce that transparency is more than a technical practice—it is a relational strategy that enables mutual accountability. By making decision-making visible and accessible, companies can foster deeper collaboration, reduce skepticism, and enhance the long-term sustainability of their CSR engagements

Multi-year commitment—captured in 182 coded references—was identified as a key factor in determining the sustainability and perceived legitimacy of CSR initiatives. Many respondents expressed frustration over projects that ceased abruptly following mine closures or leadership transitions, which not only disrupted program continuity but also led to disillusionment and loss of trust. In contrast, CSR initiatives designed with long-term horizons—spanning beyond the operational life of the mine—were praised for fostering consistency, building deeper relationships, and delivering more meaningful outcomes. Blowfield [

57] supports this view by emphasizing that in fragile or transitioning environments, sustained CSR engagement is critical to achieving structural change and lasting development. His work highlights that communities in resource-dependent regions often rely on CSR as a bridge to post-extractive resilience, making temporal consistency as important as technical quality. Taken together, these insights suggest that the duration of CSR commitments is not just a logistical or budgetary matter—it is a determinant of social credibility and impact durability. When companies embed CSR into long-term strategies, they signal accountability, enable adaptive learning, and lay the groundwork for post-mining sustainability rooted in trust and shared value.

Community co-governance—reflected in 178 coded references—was consistently identified as a vital mechanism for building mutual accountability and enhancing the legitimacy of CSR programs. Respondents emphasized that when communities were included not just as beneficiaries but as co-decision-makers, the nature of CSR shifted from short-term charity to long-term partnership. Concrete mechanisms such as participatory planning boards, village-level CSR forums, and joint monitoring committees were frequently cited as tools that allowed communities to voice priorities, oversee implementation, and ensure responsiveness. Muthuri and Gilbert [

58] support this perspective by documenting a global evolution in CSR—from unilateral philanthropic models to inclusive governance-based frameworks. Their research shows that shared decision-making structures increase transparency, empower local actors, and institutionalize community roles in shaping development outcomes. Taken together, these findings highlight that co-governance is not merely an idealistic addition to CSR—it is an operational strategy that fosters trust, enhances legitimacy, and aligns corporate responsibility with democratic accountability. When CSR is governed collaboratively, it becomes a platform for inclusive development rather than a top-down transaction.

Although the five subthemes contain 843 coded references, thematic summary data identified 749 unique coded references. The difference reflects NVivo’s coding overlap and instances where remarks were coded both at subtheme and parent levels. For analytical clarity, this finding synthesizes both levels to reflect CSR’s structural and relational roles. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in post-mining contexts is not a branding exercise—it is a governance function that builds legitimacy, fosters accountability, and enables lasting partnerships with communities. When CSR is aligned with local needs, practiced transparently, and sustained over time, it shifts from a peripheral obligation to a central pillar of rural transformation.

These findings offer important insights into the interplay between CSR and the three theoretical pillars.

Stakeholder Theory is strongly reinforced by the emphasis on multi-actor engagement and co-governance structures. When CSR operates through inclusive platforms that elevate local voices, it exemplifies stakeholder salience and collaborative value creation. However, the theory’s broader applicability is challenged when stakeholder engagement is limited to consultation without power redistribution, which several respondents critiqued as tokenistic. In terms of

Legitimacy Theory, the data support its core assertion that institutions and corporations must align their actions with community expectations to maintain credibility. The emphasis on long-term commitment, strategic alignment, and transparency mirrors Suchman’s [

34] definition of pragmatic and moral legitimacy. Yet, the theory’s assumption of a linear relationship between perceived fairness and legitimacy can be complicated by historical grievances and mistrust, especially in regions with deep extractive legacies. The

Theory of Planned Behavior is validated through the behavioral effects observed in communities exposed to consistent, transparent CSR programs. Positive experiences reinforced social norms, strengthened trust in institutional actors, and increased perceived behavioral control among farmers and community leaders to participate in sustainability programs. Nonetheless, TPB’s focus on individual intention may underemphasize structural barriers, such as unequal power relations or fragmented institutional mandates, which can suppress otherwise positive behavioral attitudes.

In summary, CSR functions most effectively when it operates as a governance bridge—connecting companies, communities, and state actors through transparent, aligned, and long-term engagement. The findings strengthen theoretical claims while also pointing to critical limitations, calling for a nuanced, context-sensitive application of stakeholder, legitimacy, and behavioral theories in post-mining sustainability transitions. In post-mining territories, CSR is not about giving back—it is about showing up: consistently, accountably, and in partnership with those who live the transformation.

While CSR provides a platform for corporate responsibility and social legitimacy, long-term sustainability relies on the active coordination and policy mandates of formal institutions. The next section examines the critical role of government and regulatory bodies in enabling, legitimizing, and harmonizing post-mining land reclamation efforts.

4.2. Institutional Role: Coordinating, Enabling and Legitimation Post-Mining Reclamation

Institutions play a pivotal role in ensuring that post-mining land reclamation is not only technically sound but socially embedded, legally grounded, and strategically coordinated. This theme is supported by 530 coded references, organized into five refined subthemes based on NVivo coding: Capacity-building Programs (25 references), Extension Services (44), Government Coordination (87), Institutional Legitimacy (145), and Land Policy Enforcement (77).

Capacity-building programs—reflected in 25 coded references—focused on institutional efforts to equip farmers and community leaders with the competencies needed to manage reclaimed land in sustainable and productive ways. Respondents described a variety of training initiatives, including reclamation schools, ecological literacy workshops, and smallholder business modules aimed at improving financial literacy and post-harvest practices. These programs were often delivered through partnerships involving government agencies, NGOs, and private sector CSR platforms. Hamidov et al. [

59] emphasize that for capacity-building to drive long-term behavioral change, it must combine technical content with participatory learning approaches that are locally relevant and culturally sensitive. Their work shows that sustainability is reinforced when learners can directly relate training to their lived experiences and land-use practices. Complementing this, USDA NRCS [

60] highlights the importance of iterative support mechanisms and cross-sectoral coordination—demonstrating that capacity-building is most effective when institutions offer follow-up, mentorship, and context-specific adaptation, especially in fragile or transitioning landscapes. Taken together, these findings suggest that capacity-building is not simply about one-time knowledge transfer—it is an ongoing process that builds adaptive capacity, reinforces agency, and embeds resilience into the foundations of reclaimed agricultural systems. When implemented holistically, such programs serve as both a technical foundation and a social catalyst for sustainable land stewardship.

Extension services—captured in 44 coded references—were described as vital channels of field-level technical assistance delivered by both government agencies and CSR-aligned field teams. Respondents consistently emphasized the importance of timely, on-site support that included personalized advice, regular follow-ups, and hands-on problem-solving—particularly during early stages of cacao cultivation and land recovery. Cedric et al. [

61], in their study of cocoa-producing regions in Cameroon, highlight the crucial role of both state and non-state extension agents in helping farmers navigate productivity constraints, soil degradation, and shifting climate patterns. Their findings affirm that effective extension services build adaptive capacity by connecting farmers to innovations and actionable knowledge. Similarly, Shillie et al. [

62] demonstrate that certified farming schemes rely heavily on embedded extension models, where CSR-backed field teams provide consistent coaching to ensure technical adoption, quality control, and ongoing compliance with sustainability standards. These long-term engagements help farmers internalize best practices while boosting confidence and accountability. Taken together, these insights suggest that extension services are not just add-on supports—they are foundational enablers of sustainable land-use transitions. When extension systems are localized, responsive, and embedded within broader institutional frameworks, they serve as the connective tissue that links farmer needs with policy goals, market standards, and environmental restoration in post-extractive landscapes.

Government coordination—reflected in 87 coded references—emerged as a critical enabler and, at times, a bottleneck in the effective implementation of post-mining land reclamation programs. Respondents discussed the importance of aligning mandates and efforts across multiple government bodies, including those overseeing land use, CSR compliance, agricultural extension, and environmental restoration. While some described successful models of inter-agency collaboration, others pointed to fragmentation and conflicting priorities as key challenges in achieving coherent policy delivery. Ostrom [

63] provides foundational insight into the complexities of institutional arrangements in managing shared resources, arguing that effective governance of common-pool assets—such as reclaimed land—requires nested systems of rules and clearly defined roles across multiple levels of authority. Expanding on this, the World Bank [

64] highlights the pressing need for multilevel policy coherence in decentralized governance contexts, noting that lack of coordination between national strategies and local implementation frameworks often results in inefficiencies or policy drift. Taken together, these perspectives affirm that government coordination is not merely an administrative concern—it is a structural prerequisite for successful and sustainable land-use transitions. Cross-sectoral governance mechanisms, clearly delineated mandates, and integrated planning processes are essential for transforming fragmented initiatives into unified efforts that align with both community needs and national development objectives.

Institutional legitimacy—highlighted in 145 coded references—emerged as a foundational condition for effective governance in post-mining land reclamation. Respondents frequently linked trust in government agencies, NGOs, and CSR actors to perceptions of integrity, transparency, and consistent responsiveness. Institutions that were seen as legitimate—those that engaged meaningfully with communities, honored commitments, and provided timely support—were markedly more successful in mobilizing participation and sustaining long-term stewardship. Young [

65] emphasizes that institutional legitimacy enhances the “fit” between governance structures and the socio-ecological systems they aim to manage. His framework suggests that legitimacy improves coordination across governance scales, enabling policies to align more closely with environmental goals and local realities. Arif [

66] complements this perspective by providing empirical evidence that legitimacy—both political and institutional—significantly boosts a government’s capacity to implement effective programs, generate compliance, and foster citizen engagement, particularly in decentralized or contested landscapes. Taken together, these insights position legitimacy not as a theoretical abstraction but as a practical and strategic driver of governance performance. In reclamation contexts, where institutional trust is often fragile, legitimacy becomes the bridge that links policy intent with on-the-ground transformation—ensuring that institutions are not only present but also respected and followed.

Land policy enforcement—reflected in 77 coded references—focused on the capacity of institutions to uphold, monitor, and ensure compliance with land-related regulations in post-mining reclamation zones. Respondents emphasized the importance of protecting land boundaries, preventing illegal occupation or land grabs, and holding stakeholders accountable to environmental restoration commitments. In many cases, visible enforcement was seen as critical for maintaining the credibility of reclamation programs and deterring opportunistic behavior during the transition from extractive use to sustainable agriculture. Ostrom [

44] underscores that the long-term sustainability of common-pool resources hinges on clearly defined rules and the presence of credible sanctions—administered either by trusted authorities or through community-based mechanisms. Her design principles highlight that rule enforcement must be context-specific, legitimate, and backed by the authority to act. Building on this, McDermott et al. [

67] caution that enforcement mechanisms, if not embedded in equitable and inclusive governance frameworks, can inadvertently reinforce existing power imbalances, exclude marginalized actors, and undermine the very goals of justice and environmental integrity they aim to protect. Taken together, these insights affirm that land policy enforcement is more than a technical or regulatory function—it is a deeply social and political process. For enforcement to serve as a pillar of institutional trust and land-use legitimacy, it must be transparent, participatory, and responsive to the local context, ensuring not only compliance but fairness and community empowerment.

These five subthemes account for 378 coded references, while the thematic summary of the parent node includes 530 coded references. The discrepancy reflects overlapping codes and broader institutional remarks coded directly at the parent level. In conclusion, institutions are not just facilitators of post-mining land transitions—they are enablers of systemic change. Through legitimacy, coordination, services, and enforcement, they provide the scaffolding needed for reclamation to evolve from fragmented intervention into a durable and trusted governance practice.

Institutions are not passive implementers—they are the strategic backbone of post-mining land reclamation. When they coordinate effectively, enable local actors, enforce land rights fairly, and earn legitimacy through transparency and engagement, they transform reclamation from isolated intervention into a sustained and credible development pathway.

Collectively, this finding affirms the relevance of Stakeholder Theory, Legitimacy Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Stakeholder Theory is reinforced by the necessity of institutional coordination and multi-actor alignment. Effective reclamation outcomes depend not only on stakeholder participation but also on institutional frameworks that fairly balance authority and responsibility. However, it also challenges the theory’s implicit assumption that actors operate with shared interests—clarity in power structures is equally vital for achieving collaborative goals. From a Legitimacy Theory standpoint, government transparency and role clarity are essential to public trust. When roles are well-defined and programs are aligned, legitimacy is strengthened. Conversely, disjointed mandates and unclear legal status erode the credibility of institutional actors and reduce public confidence in reclamation governance. Communities are more likely to support and participate in land transitions when institutions fulfill their procedural and moral obligations consistently. Finally, this theme speaks to the Theory of Planned Behavior by illustrating how institutional trust and regulatory predictability affect behavioral control and intention. Farmers and community actors are less likely to engage in land-use transformation if regulatory processes are opaque or unreliable. When institutions are seen as capable, consistent, and responsive, they shape social norms and individual motivations in ways that make sustainable practices more achievable.

Institutional presence alone is not sufficient without inclusive mechanisms for negotiation and co-creation. The following section explores how multi-stakeholder collaboration strengthens governance by fostering trust, mediating conflict, and anchoring co-ownership among all actors.

4.3. Stakeholder Collaboration: Cultivating Trust, Resolving Conflict, and Enhancing Co-Ownership

Post-mining land reclamation thrives when collaboration replaces fragmentation, and when trust is cultivated through inclusive and accountable governance. This theme is supported by 372 coded references, synthesized across five verified subthemes: Benefit-sharing Schemes (27 references), Community Feedback Loops (142), Co-monitoring Processes (30), Conflict Resolution Mechanisms (167), and Cross-sector Partners (6).

Benefit-sharing schemes—captured in 27 coded references—focused on how both material and non-material gains were distributed among stakeholders participating in post-mining land reclamation. Respondents highlighted examples such as equitable access to rehabilitated land, input subsidies (e.g., seedlings and tools), and employment opportunities linked to restoration activities. When benefits were perceived as fairly allocated and transparently managed, community members expressed greater trust, willingness to participate, and a stronger sense of shared ownership over reclamation outcomes. Schreckenberg et al. [

68] argue that equitable benefit-sharing is a foundational principle of environmental governance, emphasizing that material redistribution must be coupled with processes of social recognition and inclusive engagement—particularly in contexts involving vulnerable or historically excluded groups. Building on this, Santarlacci et al. [

69] propose participatory governance frameworks in which financial and non-financial benefits are co-designed with local and Indigenous communities, ensuring that distribution mechanisms reflect context-specific needs, values, and customary rights. Taken together, these perspectives affirm that benefit-sharing is not only about what is shared but also about how and with whom. In post-extractive landscapes, where power dynamics and historical grievances often shape local perceptions, fair and participatory benefit-sharing becomes both a justice imperative and a governance tool for building legitimacy, cohesion, and lasting stewardship.

Community feedback loops—evident in 142 coded references—emerged as critical mechanisms for ensuring mutual accountability, continuous learning, and inclusive decision-making in post-mining reclamation efforts. Respondents described a range of feedback channels, including village forums, multi-stakeholder dialogues, suggestion boxes, and participatory monitoring and evaluation exercises. These platforms were credited with improving program quality, surfacing local concerns, and building transparency and trust between community members, implementing agencies, and corporate actors. Goethel et al. [

70] support this perspective by demonstrating that stakeholder involvement in iterative management strategies enhances adaptive co-management, allowing governance systems to remain flexible and responsive to evolving local needs. Their research affirms that when communities are not just consulted but continuously engaged, policy and program implementation becomes more contextually grounded and resilient. Adding to this, Hamilton et al. [

71] emphasize the importance of integrating feedback loops into broader social-ecological systems frameworks. They show that such loops help uncover hidden cognitive biases, institutional inertia, and disincentives that might otherwise block innovation or reform—thus playing a crucial role in making governance systems more self-correcting and learning-oriented. Taken together, these insights affirm that community feedback is not simply an add-on to engagement—it is a structural element of good governance. By embedding iterative communication into the fabric of reclamation programs, institutions can cultivate legitimacy, adapt to complexity, and co-create solutions that endure

Co-monitoring processes—identified in 30 coded references—referred to collaborative efforts to track reclamation progress through active involvement of farmers, village authorities, CSR field teams, and NGOs. These practices included joint field inspections, participatory mapping of reclaimed areas, and the use of community scorecards to assess project milestones. Respondents emphasized that such co-monitoring initiatives were instrumental in fostering shared understanding, validating progress claims, and reinforcing mutual accountability among stakeholders. Danielsen et al. [

72] provide strong support for this view, demonstrating that locally-based monitoring systems not only generate relevant, real-time data but also enhance adaptive environmental management by empowering communities to play a direct role in governance. Their findings highlight that trust in monitoring increases when local actors are not merely observers, but co-producers of information and oversight. Similarly, the Global Environment Facility [

73] stresses that participatory monitoring frameworks are essential for ensuring transparency, improving learning loops, and holding both public and private actors accountable to sustainability commitments. Taken together, these perspectives underscore that co-monitoring is far more than a data collection exercise—it is a relational and governance-building mechanism. When embedded within reclamation programs, co-monitoring fosters inclusive oversight, nurtures local ownership, and supports more credible, adaptive, and equitable land-use transitions.

Conflict resolution mechanisms—highlighted in 167 coded references—emerged as the most frequently cited subtheme in relation to post-mining land reclamation governance. Respondents described how a variety of conflicts—ranging from land boundary disputes and unmet program expectations to misunderstandings between stakeholders—were addressed through both formal and informal channels. These included village council deliberations, CSR-appointed ombudspersons, and the involvement of respected third-party mediators such as community elders or civil society representatives. Such mechanisms were consistently identified as vital to maintaining stakeholder trust, minimizing escalation, and ensuring the continuity of reclamation programs. Fisher-Yoshida [

74] offers theoretical grounding for this approach by emphasizing the importance of intercultural dialogue and the need to recognize the deeply held paradigms and power asymmetries that inform conflict perceptions. Her work highlights that true conflict transformation involves more than resolution—it requires creating space for mutual recognition and systemic reflection. Complementing this, Wynn [

75] advocates for inclusive, education-based conflict frameworks that prioritize shared understanding, capacity building, and participatory learning as tools for long-term transformation. Taken together, these insights suggest that effective conflict resolution in land governance settings must go beyond immediate dispute settlement. When framed as opportunities for dialogue and collective learning, conflict resolution mechanisms become foundational to building resilient, locally legitimate, and adaptive land-use systems in post-extractive contexts

Cross-sector partners—though only referenced in 6 coded segments—nonetheless emerged as important enablers within post-mining reclamation governance. Respondents noted the valuable roles played by NGOs, academic institutions, and development agencies, particularly as neutral facilitators, knowledge brokers, and technical advisors. These actors often served to bridge institutional divides, support marginalized voices, and help reconcile divergent agendas between government agencies, communities, and private sector stakeholders. Emerson et al. [

76] provide theoretical support for this function, arguing that third-party conveners play a catalytic role in collaborative governance by fostering principled engagement, nurturing shared motivation, and enhancing the collective capacity for coordinated action. Their framework emphasizes that durable partnerships are often rooted in the facilitative competencies that external actors bring to multi-stakeholder settings. Expanding on this, Hafer et al. [

77] caution that power dynamics within cross-sector collaboration must be interpreted through functional, critical, and pragmatic lenses. They argue that while external actors can strengthen governance, they must be mindful not to unintentionally reproduce existing inequalities or institutional biases—particularly when working in historically contested or extractive contexts. Taken together, these insights highlight that cross-sector actors are not passive supporters, but essential contributors to the legitimacy, innovation, and inclusiveness of reclamation governance. When engaged thoughtfully, they help create collaborative spaces that are not only technically effective, but also socially equitable and conflict-sensitive.

The total number of references across these five subthemes is 372, while the thematic summary of the parent node includes 665 coded references. The gap reflects overlapping codes and general insights coded directly to the stakeholder collaboration node when respondents discussed systemic partnership dynamics. Stakeholder collaboration is not a procedural formality—it is the lifeblood of post-mining reclamation governance. When communities, companies, governments, and civil society engage as co-creators rather than separate actors, land restoration evolves from fragmented intervention into a shared journey of trust-building, conflict resolution, and long-term stewardship.

This finding strongly reinforces Stakeholder Theory, especially its emphasis on salience, legitimacy, and participatory structures. The transition from consultation to co-creation reveals that enduring outcomes require relational governance rather than transactional engagement. Stakeholder Theory is expanded here through attention to feedback loops and negotiated benefit-sharing that go beyond traditional engagement checklists. The insights also support Legitimacy Theory, demonstrating that communities judge institutional legitimacy not solely on policy but on inclusion, transparency, and responsiveness. Trust is earned through consistent dialogue and responsiveness to local values. When governance aligns with community expectations, legitimacy becomes a co-produced outcome rather than a top-down assumption. Finally, the Theory of Planned Behavior is illustrated through the behavioral outcomes associated with collaboration. When feedback channels and co-monitoring are in place, individuals report greater confidence in the system (perceived behavioral control), stronger communal norms around participation (subjective norms), and higher intent to sustain engagement. These psychological pathways validate the TPB’s relevance in collaborative governance environments.

Collaborative governance gains legitimacy when it addresses historical grievances and rights-based claims. The next section investigates how land compensation strategies transform liability into opportunity by securing access, ensuring fairness, and restoring community trust.

4.4. Land Compensation Strategy: Transforming Liability into Opportunity

Land compensation strategy is a cornerstone theme in post-mining reclamation, serving both as a restorative mechanism and a developmental opportunity. This theme is supported by 674 coded references, which have been synthesized into five subthemes: Post-Mining Land Legitimacy (148 references), Strategic Land Allocation (131), Integration into Village Spatial Planning (122), Incentive Mechanisms (138), and Community Acceptance and Trust (135).

Post-mining land legitimacy—reflected in 148 coded references—emerged as a foundational precondition for successful reclamation and long-term investment. Respondents consistently emphasized the importance of formal documentation, legal clarity, and the recognition of customary or indigenous rights. In many cases, communities viewed reclaimed land as insecure or “borrowed” when these conditions were absent, leading to reluctance in committing labor or resources to sustainable land use. Larson et al. [

78] highlight that secure tenure and recognized land rights are critical drivers of local engagement in resource conservation, particularly in decentralized governance systems like Indonesia’s. Similarly, Rakotonarivo et al. [

79] shows that in resource-based economies, perceived legitimacy of land tenure significantly influences willingness to invest in ecological restoration, as ambiguity undermines both trust and accountability. Taken together, these findings suggest that legitimacy—both legal and perceived—is not merely a bureaucratic formality but a behavioral enabler. When communities are assured of their land rights, they are far more likely to participate actively in long-term reclamation and stewardship, anchoring sustainability in a foundation of security and recognition.

Strategic land allocation—highlighted in 131 coded references—focused on how post-mining reclaimed land was distributed among different user groups, influencing both equity and sustainability outcomes. Respondents described a variety of allocation approaches, including village-managed demonstration plots, shared community parcels, and prioritization schemes aimed at youth, women, and economically vulnerable households. Many emphasized that fairness, transparency, and participatory decision-making were essential to prevent conflict and ensure long-term community buy-in. Borras and Franco [

80] emphasize that the success of land reform and redistribution efforts—particularly in decentralized contexts—depends heavily on inclusive targeting and equity-focused implementation. Their research underscores that land access must be socially negotiated and institutionally supported to avoid reinforcing existing inequalities. Taken together, these insights suggest that reclaimed land allocation is not just a logistical exercise, but a strategic process deeply tied to legitimacy, representation, and community cohesion. When allocation mechanisms are transparent and inclusive, they reinforce perceptions of justice and ownership, motivating collective stewardship and strengthening the social foundations of sustainable land use.

Integration into village spatial planning—evident in 122 coded references—emerged as a critical factor for securing the long-term relevance and stability of post-mining reclamation efforts. Respondents emphasized that when reclaimed lands were formally embedded into village maps, zoning documents, or mid-term development plans, they gained greater institutional legitimacy and became more attractive for long-term investment and use. Roengtam and Agustiyara [

81] demonstrate that spatial planning serves not only as a technical tool but as a governance mechanism that legitimizes land use decisions and aligns local aspirations with formal development pathways. Similarly, Ibrahim et al. [

82,

83] highlight how the inclusion of reclaimed land in participatory village planning frameworks reduces the risk of future land-use conflicts, particularly when multiple actors—such as customary leaders, government agencies, and community groups—are engaged in decision-making. Taken together, these insights suggest that integrating post-mining lands into formal spatial and development planning is more than a procedural step; it is a strategic act of institutional embedding. This alignment enhances legal clarity, promotes cross-sectoral coordination, and ensures that reclaimed landscapes are not left in limbo, but actively contribute to the village’s broader socio-economic trajectory.

Incentive mechanisms—highlighted in 138 coded references—played a catalytic role in encouraging farmer participation and sustaining post-mining land reclamation efforts. Respondents pointed to various forms of incentives, including the provision of cacao seedlings, farming tools, agricultural subsidies, and access to secure market linkages. These forms of support were seen not only as material enablers but also as symbolic signals of institutional commitment. Bryan [

83], drawing from behavioral economics, emphasizes that well-timed and context-sensitive incentives can significantly increase the likelihood of early adoption, particularly in settings where perceived risk is high and behavioral inertia is strong. His research suggests that incentives are most effective when they lower initial barriers and nudge individuals toward experimentation, which can later translate into long-term behavioral change. Taken together, these findings underscore that incentive structures are not merely about compensation or support—they are strategic instruments of behavioral activation. When thoughtfully designed, they reduce uncertainty, encourage trial participation, and build the momentum necessary for broader community uptake of sustainable land practices.

Community acceptance and trust—captured in 135 coded references—emerged as a crucial social linchpin for the success of land compensation and reclamation initiatives. Farmers expressed a greater willingness to engage in post-mining land use when the process was perceived as inclusive, transparent, and grounded in mutual respect. Pratama et al. [

84] highlight that community buy-in is significantly strengthened when compensation processes are preceded by open dialogue, accessible information sharing, and repeated fulfillment of earlier commitments. In contrast, broken promises or top-down approaches often eroded trust and provoked resistance. Similarly, Lyu et al. [

85] emphasize the role of social capital—particularly the involvement of respected community figures—in enhancing perceived fairness and fostering long-term cooperation. Their findings show that participatory mechanisms such as village forums and leadership engagement can transform abstract policies into locally owned practices. Taken together, these insights suggest that trust is not merely a byproduct of successful implementation—it is a precondition. When communities feel heard, included, and respected, they are far more likely to view land compensation not as external imposition but as a legitimate opportunity for shared progress.

While the total reference count across these five subthemes is 674, thematic summary data showed 593 unique coded references under the parent node. This gap reflects the presence of overlapping references coded to multiple subthemes or directly to the broader theme of land compensation when data did not neatly fall under a single category. Land compensation is not just a restorative gesture—it is a strategic mechanism for transforming post-mining liability into long-term opportunity. When land redistribution is handled with legitimacy, transparency, and inclusivity, it repositions degraded terrain as a platform for local development, community ownership, and future prosperity.

This finding provides significant insights for three key theoretical lenses: Legitimacy Theory is directly supported through the emphasis on legal clarity, recognition of customary rights, and institutional embedding. Secure and recognized land rights build moral and procedural legitimacy, which are essential for mobilizing long-term community stewardship. Conversely, when land compensation lacks legal certainty or fails to respect local norms, it undermines institutional legitimacy and perpetuates historical grievances. Stakeholder Theory is affirmed in how inclusive planning, equitable land allocation, and transparent incentive systems increase stakeholder salience and strengthen co-ownership. It expands the theory’s relevance by emphasizing that stakeholders are not passive recipients but co-creators of governance solutions. However, failure to engage key stakeholders in meaningful decision-making undermines the theory’s assumptions about mutual benefit and participatory governance, reducing legitimacy and shared responsibility. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is demonstrated in how legitimacy and incentives enhance perceived behavioral control and shape positive intentions toward land use. When systems reduce uncertainty and reflect shared values, farmers and local actors are more likely to engage in sustainable practices. On the contrary, if governance systems are opaque or poorly communicated, perceived behavioral control declines, social norms become fragmented, and the likelihood of voluntary behavioral change diminishes. In sum, land compensation is not merely a post-extractive obligation—it becomes a transformative mechanism when rooted in legitimacy, inclusion, and behavioral activation. It shifts the paradigm from reactive restoration to proactive rural development grounded in trust and co-ownership. Yet, this potential can only be realized if institutional structures and stakeholder relationships are consistently inclusive, credible, and responsive.

In post-extractive settings, land is not merely returned—it is repositioned as a shared resource, a justice tool, and a launchpad for sustainable futures. However, land alone does not guarantee participation—behavioral intention and readiness must also align. The following section delves into how farmers’ attitudes, social norms, and perceived control shape their willingness to engage in sustainable post-mining land use.

4.5. Behavioral Change as a Driver of Post-Mining Land Use Decisions

Behavioral change is central to transforming degraded post-mining landscapes into productive agroecosystems. This theme is supported by 812 unique coded references, interpreted through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The analysis is organized around five interrelated subthemes: Attitudes Toward Sustainability (103 references), Subjective Norms and Peer Influence (236), Perceived Behavioral Control (120), Risk Perception and Motivation (164), and Community Readiness (189).

Attitudes toward sustainability—captured in 103 coded references—played a pivotal role in shaping how farmers interpreted the purpose and value of post-mining reclamation. Many participants conveyed a strong moral and intergenerational commitment to restoring degraded landscapes, often framing reclamation as an obligation to preserve land for future generations. Cacao frequently emerged as a symbol of ecological renewal and long-term stability, described by some as a “hopeful” crop due to its perennial nature and capacity to regenerate disturbed soils. These positive attitudes were often influenced by agricultural training and exposure to demonstration plots, which enhanced farmers’ perceived behavioral control and confidence in sustainable practices [

17]. In parallel, religious teachings and local cultural narratives around land stewardship further reinforced sustainability as a moral imperative [

86]. Together, these insights suggest that behavioral readiness for sustainable reclamation is not only shaped by technical exposure but also by deep-seated social norms and ethical worldviews.

Subjective norms and peer influence—supported by 236 coded references—revealed the significant role of social structures in shaping farmers’ behavioral intentions toward cacao-based post-mining reclamation. Many farmers described how peers, village leaders, and local champions served as informal authorities whose actions and endorsements influenced decision-making. Mudege et al. [

87] highlight that farmers are more likely to adopt new practices when they observe successful examples among their social peers, particularly in closely-knit rural communities where innovation spreads through observation and informal conversation. Meanwhile, Hidayah et al. [

88] emphasize the influence of religious and community leaders in setting normative expectations around land use, particularly when sustainability is framed as a communal and spiritual responsibility. When these respected figures lead by example—by cultivating cacao themselves or promoting land restoration publicly—their actions serve as powerful social proof, legitimizing change and reinforcing behavioral commitment. Taken together, these findings suggest that normative pressure is most persuasive when it arises from within culturally embedded structures of trust and authority, bridging individual intent with collective acceptance.

Perceived behavioral control—reflected in 120 coded references—captured how farmers assessed their own capacity to engage in reclamation activities using sustainable methods such as cacao cultivation. Many farmers described a sense of empowerment when they had access to essential resources like tools, seedlings, and ongoing technical support. Ajzen and Schmidt [

89] emphasize that perceived behavioral control is closely linked to the availability of enabling conditions; when farmers feel they have the means and support, their intention is more likely to convert into action. Conversely, barriers such as unreliable irrigation, limited financial capital, or fear of crop failure significantly diminished farmers’ confidence in their ability to succeed. Ofosu-Ampong et al. [

90] similarly found that even when positive attitudes and social encouragement were present, a lack of infrastructural support could neutralize motivation and stall adoption of sustainable practices. Together, these insights suggest that behavioral intention alone is insufficient—perceived capacity to act, shaped by access to tangible support systems, is a decisive factor in whether sustainable reclamation practices are realistically adopted and maintained.

Risk perception and motivation—reflected in 164 coded references—were found to be deeply intertwined in shaping farmers’ behavioral decisions regarding post-mining land reclamation. Farmers with prior agricultural experience or access to training tended to perceive the risks of adopting cacao-based systems as manageable, often drawing confidence from their past success or technical knowledge. Wauters & Mathijs [

91] highlight that experience significantly reduces perceived uncertainty, enabling farmers to make more rational and confident land-use decisions in the face of environmental and economic variability. On the other hand, households that were previously dependent on mining income or lacked farming experience often viewed reclamation activities as uncertain, unsafe, or even economically unviable. Daxini et al. [

92] emphasize that individual motivation is strongly influenced by expected outcomes—whether economic, familial, or ideological. In this context, many farmers cited income diversification, the desire to leave a land legacy for their children, and spiritual values tied to environmental stewardship as key motivational drivers. Taken together, these findings suggest that perceived risk does not operate in isolation; it is filtered through both prior experience and the strength of intrinsic motivation. When confidence aligns with meaningful personal incentives, farmers are more likely to engage in sustainable reclamation despite uncertainties.

Community readiness—reflected in 189 coded references—captured the collective dynamics that drive behavioral change at the village level. Farmers expressed a greater willingness to adopt cacao-based reclamation when they observed active participation from their peers and consistent engagement from institutional actors such as agricultural extension agents or CSR facilitators. Rogers et al. [

93] emphasize that visible early adopters within a community can serve as behavioral catalysts, especially when participation reaches a threshold that shifts the norm from hesitancy to momentum. This sense of shared movement is further reinforced when individual costs are reduced through collective action. Mulyono et al. [

94] demonstrate that community-led initiatives—such as joint land preparation, farmer forums, or group labor arrangements—not only reduce resource constraints but also build trust and shared accountability. These activities function as tipping points where behavioral change transcends individual intention and becomes a communal practice. Together, these insights suggest that readiness for sustainable land-use transitions is not merely an individual calculation but a socially embedded process, where participation is amplified by visible support structures, shared labor, and the emergence of collective efficacy

While the five subthemes represent 812 distinct coded references, the cumulative total of references across overlapping codes reaches 890. This discrepancy reflects NVivo’s allowance for multi-coding, where a single remark may touch upon multiple behavioral dimensions. Some references were also coded directly at the parent node to reflect holistic behavioral insight.

Behavioral change is not a secondary outcome of reclamation—it is its catalyst. In the context of post-mining landscapes, sustainable land use begins not with tools or funding, but with shifts in mindset, social norms, and perceived ability to act. When farmers develop positive attitudes, feel supported by their peers, and trust in their capacity to succeed, their role transforms from passive recipients to proactive land stewards.

This finding significantly deepens the applicability of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in post-mining settings. TPB is reinforced by how personal attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control converge to shape behavioral intention. The finding confirms that behavioral change begins with belief, is legitimized through community norms, and is enabled by tangible support systems. When these three components align, farmers shift from passive recipients to proactive land stewards. However, the application of TPB also exposes its vulnerability in under-resourced settings. Positive attitudes and peer pressure cannot produce behavioral change if structural barriers—such as inadequate irrigation or market instability—persist. Thus, TPB must be applied contextually, alongside institutional interventions. Stakeholder Theory is implicitly relevant, as behavioral change is embedded in networks of peer influence, leadership trust, and communal learning. Stakeholders must be seen as interdependent actors in a shared behavioral ecosystem. Although Legitimacy Theory is not the primary frame for this theme, it appears indirectly through the role of community norms and institutional responsiveness. Trust in local facilitators, fairness of support programs, and alignment with cultural values all influence whether behavioral cues are accepted or rejected. In summary, behavioral change is not an outcome—it is a catalyst. Post-mining sustainability relies on aligning mindsets, social proof, and practical capacity. The Theory of Planned Behavior provides a powerful lens, but its real-world utility is maximized when paired with enabling environments that foster community readiness, stakeholder inclusion, and localized legitimacy.

Moreover, this insight highlights the importance of community readiness as a collective behavior dynamic. Behavioral change is not confined to the individual—it becomes a social movement when early adopters, peer networks, and trusted institutions align to generate shared momentum. By anchoring behavioral theory in real-world rural experience, this finding reinforces the idea that sustainable reclamation is driven as much by belief and trust as by policy or input. TPB, when applied contextually, becomes not just a predictive model, but a roadmap for enabling transformation at the human level.

Motivation is most effective when paired with capacity and agency. The next section highlights how farmer empowerment—through training, inclusion, and leadership development—builds the human capital needed to actualize sustainable land transitions.

4.6. Farmer Empowerment: Cultivating Agency, Leadership, and Local Ownership