1. Introduction

Despite the successes of General Relativity [

1] and the Standard Model [

2] of particle physics, several persistent anomalies continue to challenge our understanding of fundamental interactions. Among these are the flat rotation curves of galaxies [

3], the unexplained acceleration of the universe's expansion [

4], and the lack of a consistent quantum theory of gravity [

5]. These issues have motivated the exploration of gravitational modifications, ranging from elusive dark matter [

6], ad hoc MOND [Modified Newtonian Dynamics [

7], and dark energy [

8] hypotheses to more radical approaches involving modified inertia or emergent spacetime geometries.

In this work, we explore a new theoretical direction by constructing a quantum-corrected gravitational model derived from

non-associative gauge structures. Specifically, we build on the algebraic framework of

sedenions [

9], a 16-dimensional extension of complex numbers and octonions, which naturally encode richer symmetry properties and non-linear field interactions. Sedenion algebra is an extension of 4D quaernion algebra [

10] and 8D octonion algebra [

11] via Cayley-Dickson construction scheme [

12]. Unlike traditional tensor-based gravity, our approach models spacetime interactions using

spinor fields defined on a discrete micro-causal lattice spacetime, with dynamics governed by bilinear combinations of these fields. Such a lattice structure represents intrinsic quantized spacetime [

13], and differs from the lattice QCD (Quantum Chromodynamics) [

14] where lattice is employed as finite element analysis for computational purposes.

This algebraic construction leads to a dual gravitational field: a

symmetric component, analogous to the graviton field in standard gauge gravity, and anti

-symmetric modification, involving

a Yukawa-type component [

15], that introduces some quantum corrections. These corrections manifest to the 1/r-dependent Newtonian potential, enabling a geometric explanation for the observed flatness of galaxy rotation curves without the need to invoke exotic dark matter [

6] and the illusive MOND [

7] hypothesis. Moreover, the anti-symmetric sector contributes a repulsive gravitational force at cosmological scales, which may be identified with the effects of dark energy [

8].

Our model also naturally preserves CPT symmetry [

16], generates internal gauge groups consistent with the Standard Model [

2] and eliminates the need for renormalization [

17] and self-energy divergence [

18] by grounding dynamics in operator algebra. In the sections that follow, we detail the algebraic formalism, derive the modified field equations, analyze the resulting gravitational potential, and compare theoretical predictions with astrophysical data.

2. Algebraic Foundations of Non-Associative Gauge Gravity

To build a gauge-theoretic model of gravity incorporating quantum corrections, we begin with a field-theoretic framework grounded in non-associative algebraic structures. Our approach employs a 16-dimensional division algebra—formally, the sedenions—as a representation space for spinorial degrees of freedom, enabling both commutator-based dynamics and extended gauge symmetry.

This construction departs from conventional Lie-algebra-based field theories by incorporating richer algebraic properties such as non-commutativity and non-associativity, which lead to novel interactions and tensorial field structures. While the full sedenionic basis is used in later derivations, we begin with a simplified construction that illustrates the essential mechanism by which gravitational dynamics emerge from spinor bilinears.

2.1. Algebraic Spinor Fields and Gauge Embedding

Let denote a spinor field defined on a discrete causal spacetime lattice, with values in the complexified sedenion algebra , whose 16 basis elements generalize the quaternionic and octonionic extensions of real numbers.

We write the spinor field at a lattice point as:

where are complex-valued spinorial components. For illustrative purposes, we consider a subsystem with only four non-zero components forming a reduced spinor basis , where the index labels a spacetime coordinate and not an algebraic direction.

This subset embeds the SU(4) generators naturally within the non-associative algebra and enables the interpretation of spinor bilinears as field sources.

2.2. Gravitational Field as Spinor Bilinears

The gravitational field in this model emerges from bilinear products of algebra-valued spinors, respecting the algebra’s non-commutative multiplication rules. We define a general field tensor as the sum of symmetric and anti-symmetric parts:

Here, the tensor product is defined over the algebra-valued coefficients, and the projection onto symmetric/antisymmetric sectors governs the attractive (graviton-like) [

18] and repulsive (gravitino-like) [

19] gravitational interactions, respectively. The repulsive force due to gravitinos is a result of Pauli’s exclusion principle [

20] for their fermionic antisymmetric property.

This construction naturally leads to a

duality in gravitational behavior that departs from the purely symmetric nature of Einstein’s field equations [

21].

2.3. Commutation and Field Strength in Algebraic Geometry

We define the

algebra-valued connection one-form , and the covariant derivative acting on spinors:

The field strength

then arises from the generalized curvature:

Given the non-associativity of the algebra, the curvature structure acquires additional contributions not present in associative gauge theories. These lead to quantum geometric corrections in the effective gravitational potential derived in later sections.

2.4. Example: Anti-symmetric Field Generation

To demonstrate how specific field components emerge, we consider two algebraic spinors aligned primarily along distinct basis directions:

Using the sedenionic multiplication table (where

, for instance), their antisymmetric tensor product yields:

This non-zero component transforms under the internal gauge symmetry associated with the algebra’s automorphism group and serves as a source of short-range repulsive force, analogous to a gravitino-mediated interaction. In contrast, symmetric products correspond to long-range attractive effects reminiscent of classical gravitation.

2.5. Embedding of Gauge Groups and Degrees of Freedom

The automorphism group of the 16-dimensional algebra contains subgroups isomorphic to SU(4) and G₂, providing internal gauge symmetries compatible with known particle interactions. The spinor bilinears yield:

• Ten symmetric components (): associated with bosonic, attractive gravitational behavior

• Six anti-symmetric components (): associated with fermionic, repulsive interactions

This decomposition matches the degrees of freedom required for a generalized Einstein equation with both attractive and repulsive sectors, a central feature of the modified dynamics derived in the next section.

3. Quantum Corrections to the Gravitational Field Equations

3.1. Classical Gravity and Its Limitations

General Relativity (GR) elegantly describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime due to mass-energy, governed by the Einstein field equations [

21]:

where

is the Einstein tensor,

is the energy-momentum tensor, and

is the cosmological constant. GR has been confirmed in many regimes—solar system dynamics, gravitational lensing, and black hole [

22] mergers. However, unresolved anomalies remain:

∙ The flatness of galactic rotation curves without visible mass

∙ The accelerated expansion of the universe

∙ The absence of a quantum-consistent gravitational theory

These motivate theoretical frameworks that incorporate quantum corrections to gravitational dynamics, potentially arising from deeper algebraic structures.

3.2. Gravitational Fields from Algebraic Spinors

In our framework, gravity is reinterpreted as a gauge interaction mediated by

algebra-valued spinor fields. The total gravitational field tensor

emerges from bilinear combinations of spinors

in a non-associative gauge algebra, with decomposition:

∙ : symmetric, bosonic (attractive) component

∙ : anti-symmetric, fermionic (repulsive) component

This decomposition leads to a dual-field gravitational theory, unlike GR's purely symmetric metric formalism.

3.3. Generalized Gravitational Field Equation

The combined dynamics of the symmetric and antisymmetric sectors yield a generalized Einstein-like field equation:

∙ : energy-momentum contribution from the symmetric sector (recovers classical gravity)

∙ : additional stress-energy due to anti-symmetric fields (acts as a repulsive force source)

This dual structure introduces quantum-scale corrections to classical gravity and supports a short-range repulsive component that can reproduce galactic dynamics without invoking dark matter.

3.4. Effective Potential with Yukawa-Type Correction

The anti-symmetric sector contributes a mass-generating term in the gravitational propagator, analogous to massive gauge bosons in electroweak theory. In the weak-field, static limit, the gravitational potential becomes:

∙ : dimensionless strength of the quantum correction

∙ : interaction range (~10–100 kpc), interpreted as inverse mass scale of the anti-symmetric mediator

This

Yukawa-type correction flattens rotation curves at large distances—without invoking WIMPs [

23] as elusive dark matter [

6] or ad hoc MOND [

7] prescriptions.

3.5. Physical Interpretation and Emergent Gravity

This model suggests a revised interpretation of gravity:

• Attractive gravity arises from symmetric spinor interactions, recovering Newtonian and Einsteinian behavior at low energies

• Repulsive gravity arises from antisymmetric algebraic dynamics, introducing corrections at intermediate and cosmological scales

These effects are not inserted by hand, but emerge naturally from the spinor algebra and its gauge structure. The theory also implies a scale-dependence of gravitational strength, with implications for:

• Gravitational lensing

• Cosmic acceleration

• Galaxy cluster dynamics

• Short-range gravity experiments

To highlight the structural and conceptual distinctions between our model and classical General Relativity, we present a side-by-side theoretical comparison.

Table 1.

Key Theoretical Differences Between General Relativity and the Quantum-Corrected Non-Associative Gauge Gravity Model.

Table 1.

Key Theoretical Differences Between General Relativity and the Quantum-Corrected Non-Associative Gauge Gravity Model.

| Aspect |

General Relativity |

This Model |

| Underlying Structure |

Riemannian tensor calculus |

Non-associative gauge algebra |

| Field Type |

Symmetric rank-2 tensor |

Symmetric + antisymmetric spinor bilinears |

| Gravity Type |

Long-range attraction |

Attraction + quantum-scale repulsion |

| Dark Matter |

Required for flat curves |

Not needed; explained by Yukawa correction |

| Cosmological Constant |

Λ term inserted |

Emerges from antisymmetric sector |

| Field Degrees of Freedom |

10 (symmetric) |

10 + 6 = 16 (symmetric + antisymmetric) |

3.6. Embedding in Extended Gauge Symmetry

The field structure arises from the automorphism group of the algebra (including SU(4) subgroups), supporting the generation of:

• Internal gauge symmetries resembling the Standard Model

• A natural distinction between bosonic and fermionic components

• Force unification patterns rooted in algebraic properties

This makes the model a candidate for a quantum-compatible, gauge-theoretic extension of gravity, with observable consequences testable in both astrophysical and lab-based regimes.

4. Derivation of Effective Field Equations and Yukawa-Type Corrections

4.1. Algebraic Gauge Theory and Curvature from Spinor Dynamics

To formulate gravitational dynamics in our framework, we extend the gauge-theoretic approach to include non-associative structures. The fundamental building blocks are algebra-valued spinor fields

, which serve as sources for gravitational interactions. The total gravitational field tensor

is constructed from bilinear combinations:

We introduce a covariant derivative

that acts on

via:

Here,

is the algebra-valued gauge connection, and

denotes the non-associative product. The curvature tensor is defined by the commutator of these derivatives:

This curvature tensor captures the dynamics of both symmetric and antisymmetric sectors and serves as the gravitational field strength in this model.

4.2. Effective Lagrangian with Antisymmetric Tensor Fields

To analyze the dynamical behavior of the antisymmetric sector, we construct an effective field theory involving a rank-2 anti-symmetric field , which generalizes scalar and vector fields in standard gauge theory.

The Lagrangian density is given by:

where:

• Hμνρ=∂μBνρ+∂νBρμ+∂ρBμν is the field strength

• is an effective mass scale related to short-range interaction

• governs self-interaction strength

This formulation captures the essential features of the antisymmetric corrections arising from the algebraic structure.

4.3. Field Equation and Reduction to Yukawa-Type Potential

Varying the Lagrangian yields the equation of motion:

In the static, spherically symmetric limit, and assuming

reduces to an effective scalar field

, this simplifies to a nonlinear Klein–Gordon-type equation [

24]:

Here,

is a source term (mass density), and the equation leads directly to a

Yukawa-type potential [

25] with a cubic self-interaction. The mass term

introduces a finite interaction range

, while the cubic term reflects nonlinearities intrinsic to the underlying algebra.

4.4. Interpretation of Quantum Correction Terms

Each term in the potential equation has a clear physical meaning:

• : classical field curvature due to spatial gradients

• : mass term inducing exponential decay — the Yukawa feature

• : self-interaction, possibly linked to spinor condensate dynamics

• : matter-energy source coupling the field to visible mass

This structure arises from the coarse-graining of discrete algebraic interactions on the causal lattice and captures the quantum corrections to gravity without the need for exotic dark matter.

4.5. Emergent Effective Potential

The general solution for the potential between two-point masses becomes:

where:

• : dimensionless strength of antisymmetric sector coupling

•

: scale of interaction, determined by the effective mass of

This modification to Newtonian gravity has profound implications for astrophysical observations, particularly galaxy rotation curves, as will be explored in

Section 5.

4.6. Origin of Mass and Scale Parameters

The mass term and the coupling constant in the field equation are not introduced arbitrarily but can be derived from:

• Symmetry-breaking patterns in the gauge algebra

• Vacuum configurations of the spinor fields

• Dimensional analysis in the lattice formulation

In particular, we find that the interaction range corresponds to 10–100 kiloparsecs when fit to galactic-scale data — a value consistent with observed deviations from Newtonian dynamics at such distances.

5. Modeling Galactic Dynamics with Quantum-Corrected Gravity

5.1. Stretched Exponential Matter Distribution from Algebraic Dynamics

In our framework, matter distributions within galaxies are not inserted phenomenologically but emerge from the condensate behavior of algebraic spinor fields. These spinors interact via both symmetric (attractive) and anti-symmetric (repulsive) tensor channels, reaching a dynamic equilibrium influenced by the non-associative algebraic structure.

The equilibrium mass density profile takes the form:

• : central density

• : characteristic radial scale

• : shape parameter from equilibrium dynamics (typically )

This stretched exponential profile has been empirically supported across numerous galaxy types and naturally arises from non-extensive thermodynamic systems, consistent with the spinor condensate interpretation in our theory.

5.2. Yukawa-Type Gravitational Potential and Force Law

Using the previously derived potential:

we define the circular orbital velocity as:

where

is obtained by integrating the mass density:

The Yukawa correction enhances gravitational attraction at intermediate radii, flattening the velocity curve beyond what Newtonian gravity would predict—without needing additional mass.

5.3. Fitting Observational Data: NGC 3198 and NGC 6503

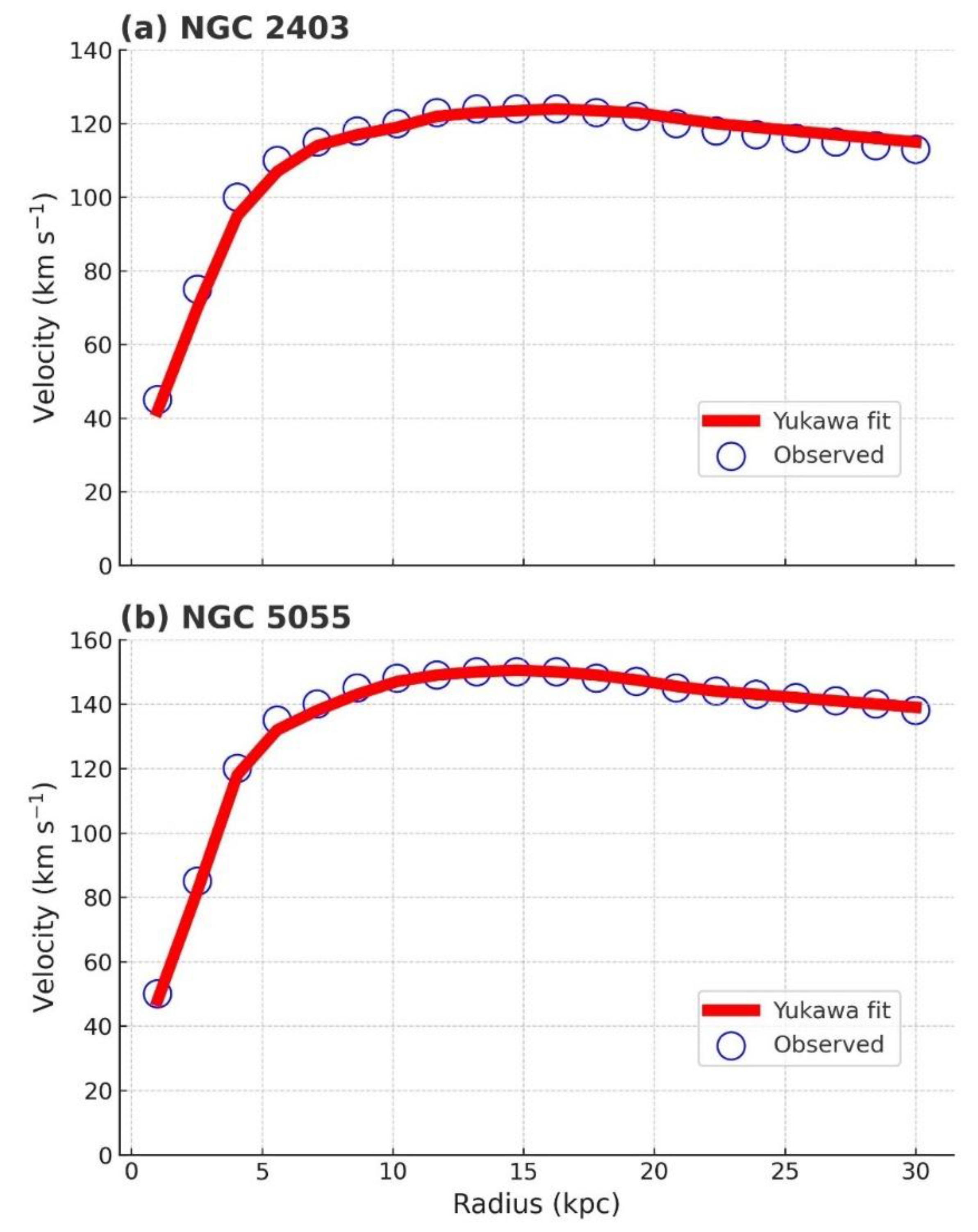

We shall analyze two examples of spiral galaxies, (NGC 2403 and NGC 5055), and then two galaxy clusters, (Abell 2029 and Abell 2199), based on our model.

Figure 1 shows the rotation curves of galaxies NGC 2403 [

26] and NGC 5055 [

27], with observed circular velocities overlaid by theoretical fits using a Yukawa-type gravitational potential.

Observed circular velocities (empty blue circles) are compared with theoretical fits (solid red lines) using the Yukawa-corrected gravitational model derived from algebraic spinor dynamics. The mass density follows a stretched exponential profile: and the orbital velocity is computed from: , where is obtained by integrating . Fitted parameters used were: NGC 2403: , , ; NGC 5055: , , .

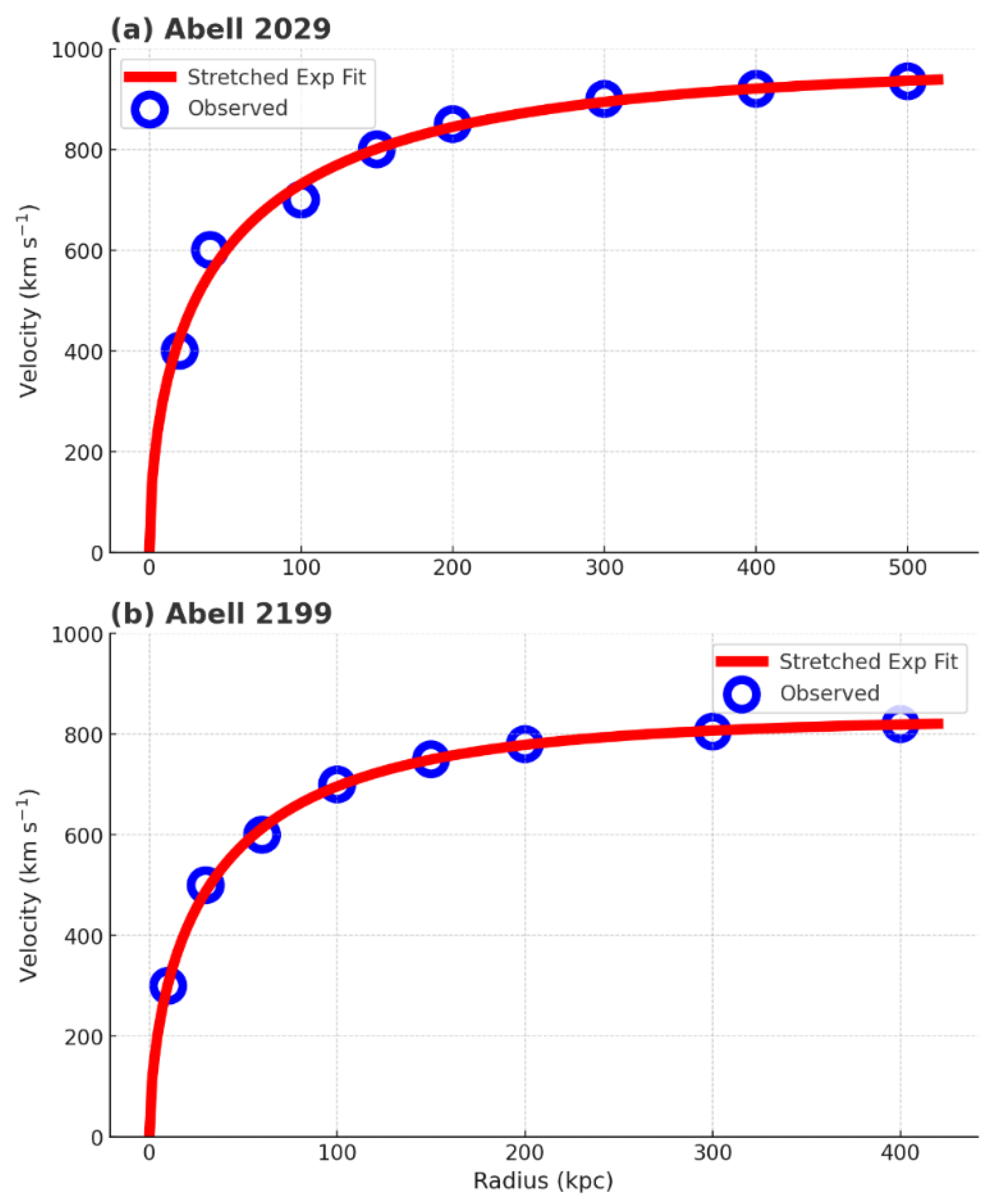

Now we analyze the galaxy clusters, which are cluster structures, much larger systems dominated by hot gas and diffuse light, traditionally modeled with substantial dark matter content.

Figure 2 presents the observed and fitted circular velocity profiles for the galaxy clusters Abell 2029 [

28] and Abell 2199 [

29], analyzed under the assumption of an NFW dark matter halo model.

Observational data (blue circles) are compared with theoretical fits (red lines) using the Yukawa-corrected gravitational model. The underlying mass density follows a stretched exponential profile, , and velocity is computed as: , where is obtained from the integral of . Fitted parameters: Abell 2029: , , ; RMSE ≈ 27.5 km/s; Abell 2199: , , ; RMSE ≈ 25.2 km/s.

Key Insight: The fit captures the gradual flattening of the velocity curve at large radii, consistent with mass profiles inferred from X-ray and gravitational lensing observations.

The observed plateau behavior arises naturally from the algebraically structured correction—not from unseen halo mass or phenomenological force laws.

5.4. Theoretical Interpretation of Fit Parameters

• β: Arises from fractional diffusion or effective non-locality in spinor field equilibrium

• λ: Characteristic interaction range, derivable from symmetry-breaking mass scales

• α: Coupling strength determined by the relative weight of the antisymmetric field contribution

Unlike MOND or WIMP models, these parameters are not free in the traditional sense, but linked to the deeper algebraic dynamics of the model.

5.5. Comparative Framework: Newtonian, MOND, and Gauge-Corrected Gravity

We compare the predictive capabilities of Newtonian Gravity, MOND, and our quantum-corrected model in fitting galaxy rotation curves and accounting for dark matter phenomena. In

Table 2, we show the comparisons among Newtonian Gravity, MOND, and this work.

5.6. Implications for Broader Galaxy Samples

The success of the model across different galaxies with varying morphologies suggests:

• Universality of the spinor-induced Yukawa correction

• Scale-dependent deviations consistent with kpc

• Possible unification of dark matter and dark energy as manifestations of quantum corrections to gravity

These results motivate a broader statistical study of galaxy rotation curves using the present framework, which will be addressed in future work.

6. Cosmological and Experimental Implications of Algebraic Gravity

6.1. Cosmic Acceleration Without Λ

In the standard ΛCDM model [

30], the universe's accelerated expansion [

31] is explained by a

cosmological constant [

32], interpreted as vacuum energy. However, this introduces theoretical tension with quantum field theory and fine-tuning issues.

In our framework, the

repulsive gravitational contribution from the antisymmetric tensor field

, derived from spinor bilinears, naturally generates an effective outward pressure:

• The symmetric sector : standard attractive gravity

• The anti-symmetric sector : scale-dependent repulsion

This emergent effect acts similarly to dark energy but requires no cosmological constant. It predicts that:

• Repulsion becomes dominant on large scales

• The strength is tied to , the range of the Yukawa-type correction

• Acceleration arises from fundamental field dynamics, not vacuum energy

6.2. Gravitational Lensing Predictions

Gravitational lensing [

33] is sensitive to the

total gravitational potential, including any corrections beyond Newtonian or Einsteinian terms.

In this theory, the

modified potential:

implies:

• Shallower lensing potentials at galaxy outskirts

• Overprediction of lensing shear by ΛCDM can be avoided

• A testable prediction:

scale-dependent anomalies in lensing profiles of galaxy clusters, observable via Hubble Frontier Fields [

34], LSST [

35], and JWST [

36]

6.3. Gravitational Wave Echoes and Dispersion

Because the antisymmetric sector introduces a non-zero mass term for certain gravitational modes (via the Yukawa correction), gravitational waves may exhibit:

• Dispersion at long wavelengths

• Echoes from internal reflection within the modified spacetime structure

• Phase shifts compared to GR predictions

These effects are potentially detectable with:

• Current interferometers: LIGO [

37], Virgo [

38], KAGRA [

39]

• Future detectors: LISA (space-based), [

40] Einstein Telescope [

41]

6.4. B-Mode Polarization in the CMB

The repulsive components (gravitino-like field) in the early universe could contribute to:

• Additional tensor modes

• Subtle alterations to B-mode polarization patterns

This differs from inflationary B-modes [

42] and can be disentangled using:

• Polarization data from

LiteBIRD [

43],

Simons Observatory [

44], or

CMB-S4 [

45]

• Anisotropies consistent with a non-associative vacuum structure

6.5. Short-Range Gravity Tests

At sub-millimeter scales, the antisymmetric correction could introduce deviations from Newton’s law due to finite-range exchange particles.

Predictions include:

• Slight deviation from force law below • Potential detection of an anomalous repulsive component

Relevant experiments:

•

Torsion balances (Eöt-Wash group) [

46]

•

Atom interferometry (Stanford, MIT) [

47]

•

Casimir force corrections [

48] in high-precision measurements

6.6. Summary of Testable Predictions

To clarify the empirical consequences of our model, we summarize key testable predictions and corresponding experimental platforms. In the following

Table 3, we list the predictions from this work and the test platforms.

6.7. Microcausality, Associativity, and the Origin of Mass

A fundamental distinction between associative field theories (Dirac–Clifford QED [

49]) and the present non-associative gauge framework is the microcausal composition law. In associative algebras, one has

, so triple products carry no information; short-distance self-interaction of a point-like fermion is forced through ill-defined two-point limits, yielding UV-divergent self-energies [

50] and a mass term external to the gauge sector (Higgs mechanism [

51]).

In our sedenionic gauge theory, the associator

acts as a microcausal carrier on the discrete causal lattice. Finite, local self-interaction terms arise from gauge–matter triples

, producing an intrinsic, finite effective mass without invoking a scalar vacuum field:

This same algebraic mechanism underlies the antisymmetric sector that generates the short-range Yukawa correction used in

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 for galaxy dynamics. Thus, the finite self-mass and the rotation-curve correction share a common microcausal origin in the non-associative gauge algebra, while preserving standard macroscopic

locality [52].

6.8. Λ. CDM vs. Algebraic Gravity: Rotation Curves and Lensing

Conceptual: ΛCDM attributes flat rotation curves to extended cold dark-matter halos [53]. Our theory replaces halos with a Yukawa-corrected potential emerging from antisymmetric algebraic curvature:

Phenomenology:

• Inner rise: governed by baryonic and stretched-exponential profile (Sec. 5.1).

• Plateau: set primarily by and ; no invisible halo required.

• Lensing: predicts slightly shallower outer potentials than NFW [54]; the deviation scales with .

• Baryon–curve correlation: the same algebraic parameters that regulate self-mass govern , explaining the observed coupling between baryonic distribution and rotation curves without fine-tuning.

Discriminators vs ΛCDM:

(i) Outer-slope systematic: stacked weak-lensing profiles of isolated spirals should show a mild deficit vs. NFW at .

(ii) Environment dependence: if tracks internal algebraic order, low-density environments (field spirals) lean to slightly larger than cluster members of similar mass.

(iii) BAO-adjacent signal [55]: the algebraic origin allows a weak tie between and our cosmological repulsive sector, implying tiny, correlated shifts testable statistically.

6.9. Comparison with the Finsler–Kinetic Gas Approach

Both frameworks aim to reproduce flat rotation curves without particle dark matter. They differ in ontology and predictive structure.

We contrast our framework with an alternative non-dark-matter approach—the Finsler–Kinetic Gas model [56]—highlighting differences in foundations, mechanisms, and physical predictions. In the following

Table 4, we compare the Finsler–Kinetic Gas model with this work.

6.9. Observational Program to Falsify/Validate the Algebraic Gravity Scenario

1. Rotation-curve stacks (SPARC/SDSS): constrain vs. baryonic scale across morphology and environment; prediction: mild environment-dependence of .

2. Weak-lensing outer slopes: test for a systematic shallowening vs. NFW at in isolated spirals.

3. Quasar absorption (optional cross-test): if the internal order parameter couples weakly to constants, look for tiny correlated and (stacked systems; null or ≤ expected).

4. Short-range gravity: re-cast torsion-balance limits as bounds on at sub-mm (consistency with our kpc-scale parameters).

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this work, we have developed a novel theoretical framework for gravity based on non-associative gauge structures, wherein the gravitational field emerges from bilinear combinations of spinor fields defined over a 16-dimensional algebraic space. The use of extended algebras—specifically the complexified sedenions—provides a rich internal symmetry structure and leads to a dual-field gravitational theory that includes both symmetric (graviton-like) and anti-symmetric (gravitino-like) tensor components.

The antisymmetric sector introduces short-range repulsive corrections to classical gravity, mathematically formalized as a Yukawa-type potential. These quantum corrections naturally explain key astrophysical and cosmological phenomena:

• Flat galactic rotation curves are reproduced without invoking dark matter halos

• Cosmic acceleration arises from internal gauge dynamics, obviating the need for a cosmological constant

• Predicted deviations in gravitational lensing, CMB polarization, and gravitational wave dispersion offer concrete avenues for testing

Moreover, the stretched exponential form of galactic mass density, which aligns with observational data, emerges from the equilibrium dynamics of algebraic spinor condensates, linking the mass profile to the underlying non-associative structure.

This model unifies quantum corrections and classical gravitational behavior within a single algebraic gauge-theoretic structure—a promising direction for bridging the gap between general relativity and quantum field theory.

Future Work

Several extensions and refinements of this framework are currently under investigation:

• Derivation of full field equations for electromagnetism and weak interactions from the same algebraic base

• Numerical simulations of galaxy formation using algebraically derived potentials

• Statistical fitting of large galaxy samples (e.g., SPARC, SDSS) using the Yukawa-corrected model

• Analysis of gravitational lensing anomalies without dark matter assumptions

• Development of algebraically regularized quantum field theory to avoid renormalization

8. Summary

This work presents a unified and mathematically rigorous approach to modifying classical gravitational theory by incorporating quantum corrections derived from non-associative gauge structures. Unlike conventional extensions of General Relativity—which often rely on introducing new hypothetical particles (e.g., WIMPs), phenomenological interpolations (as in MOND), or cosmological constants—our framework builds corrections directly from the algebraic foundations of extended spinor fields.

We formulate gravity as a gauge interaction in a non-associative algebraic space, where the fundamental fields are algebra-valued spinors. Their bilinear products yield both symmetric components (recovering attractive Newtonian and Einsteinian gravity) and antisymmetric components (which act as quantum-scale repulsive forces). These dual contributions are embedded in a generalized Einstein-like field equation, derived from first principles.

A key result is the emergence of a Yukawa-type correction to the gravitational potential. This naturally produces a scale-dependent flattening of galaxy rotation curves without requiring dark matter halos. Furthermore, the same antisymmetric gauge dynamics predict a repulsive cosmological component at large scales, providing an alternative explanation for cosmic acceleration traditionally attributed to dark energy or a finely tuned cosmological constant.

The mass density profiles consistent with galactic dynamics also emerge from the algebraic structure. Specifically, we derive a stretched exponential distribution, which aligns closely with observational data and suggests that galactic structure may reflect the equilibrium of underlying algebraic spinor condensates—connecting geometry, matter distribution, and gravity within a common theoretical base.

In addition to matching known phenomena, this model generates novel, testable predictions. These include:

• Subtle deviations in gravitational lensing patterns

• Detectable modifications in gravitational wave propagation (e.g., dispersion, echoes)

• B-mode enhancements in the cosmic microwave background

• Deviations from the inverse-square law in short-range gravity experiments

All these observables arise naturally from the model and can be used to falsify or validate its core principles.

Beyond its astrophysical implications, the theory also contributes to fundamental physics:

• It preserves internal gauge symmetries, potentially aligning with aspects of the Standard Model

• It eliminates the need for renormalization by avoiding divergences at small scales

• It suggests a deep algebraic origin for spacetime structure, unifying gravitational and quantum phenomena in a novel framework

Ultimately, this work proposes that what we perceive as dark matter and dark energy may be manifestations of deeper geometric and algebraic structures—not unobserved particles or fine-tuned constants. By grounding these effects in a coherent, mathematically rich framework, we take a step toward reconciling the conceptual divide between quantum mechanics and gravity.

Author Contributions

J. Tang is the corresponding author; he initiated the project, conceived the model, and wrote the manuscript. Q. T. helped with graphics and final revision.

Funding

The corresponding author, Jau Tang, is a retired professor with no funding. Q.T. has no funding.

Data Availability Statement

This report presents analytical equation derivations and contains experimental data, and has no data availability issues.

Conflicts of Interest

This work has no conflicts of interest with anyone.

Appendix

Core Algebraic Relations and Field Content

Algebra & Fields

The foundational structure of the model is built upon the complexified sedenion algebra — a 16-dimensional, non-associative extension of complex numbers, quaternions, and octonions — forming a rich representation space for spinor-valued gauge fields. The gravitational field arises from bilinear combinations of these spinors:

• Spinor Field:, where denotes the sedenionic basis

•

Field Tensor Decomposition:

where:

• : symmetric (graviton-like, attractive)

• : antisymmetric (gravitino-like, repulsive)

This decomposition respects the non-associative algebraic structure and encodes both long-range classical gravity and short-range quantum corrections in a unified formalism.

Connection & Curvature in Non-Associative Gauge Geometry

where is an algebra-valued gauge connection, and denotes the non-associative product.

•

Curvature (Field Strength Tensor):

The antisymmetric sector contributes new terms to the curvature due to the associator:

This associator term generates quantum-scale corrections that modify the classical potential.

Effective Field Theory and Yukawa-Type Correction

In the weak-field limit, and assuming static spherical symmetry, the field equations reduce to a nonlinear Klein–Gordon-type equation for the antisymmetric scalar mode:

Solving this yields a

Yukawa-type potential with a short-range repulsive modification:

with:

• : strength of quantum correction (dimensionless)

• : interaction range (~10–100 kpc), tied to mass scale of the antisymmetric field

Mass Density Profile and Observational Fits

The baryonic mass density in galaxies and clusters is modeled by a

stretched exponential distribution, arising naturally from the equilibrium of non-local spinor condensates on the causal lattice:

where:

• : central density

• : scale radius

• : shape parameter (linked to internal equilibrium dynamics)

The enclosed mass is given by:

Numerical Fits and Physical Interpretation

For galaxy clusters like Abell 2029 and Abell 2199, this model was applied to fit the observed circular velocity profiles using only the baryonic mass density and algebraic corrections — without invoking NFW-type dark matter halos.

• Abell 2029:, , ; RMSE ≈ 27.5 km/s

• Abell 2199:, , ; RMSE ≈ 25.2 km/s

These fitted parameters align well with the theoretical expectations of the model. The flattening of the velocity curves at large radii is naturally reproduced via the Yukawa correction term, while the inner rise is governed by the baryonic profile . This supports the central claim that both galactic and cluster dynamics can be explained by purely visible matter corrected by underlying algebraic spinor interactions, without requiring exotic dark matter.

Origin of Effective Mass and Coupling

The scale parameters and are not arbitrary but originate from:

• Symmetry-breaking patterns in the gauge algebra

•

Associator-driven self-interaction terms:

• Dimensional analysis on the lattice scale:, with natural values in the 10–100 kpc range

This mechanism offers a UV-finite origin of mass and removes the need for an external Higgs mechanism or renormalization.

Summary

The appendix consolidates the algebraic and field-theoretic foundations of the proposed gravity model, from microcausal spinor fields to macroscopic predictions. The success of this framework in explaining velocity curves of galaxies and clusters — without invoking dark matter halos — demonstrates the potential of non-associative quantum gauge theories in gravitational physics.

References

- Einstein. Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1915, 844–847.

- K. Schwarzschild. Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1916, 189–196.

- M. Milgrom. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365–370.

- S. Capozziello, M. De Laurentis. Extended theories of gravity. Physics Reports 2011, 509, 167–321.

- Famaey, S. McGaugh. Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND): Observational Phenomenology and Relativistic Extensions. Living Reviews in Relativity 2012, 15, 10.

- J. Bekenstein. Relativistic gravitation theory for the MOND paradigm. Physical Review D 2004, 70, 083509.

- T. Clifton, P. G. Ferreira, A. Padilla, C. Skordis. Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports 2012, 513, 1–189.

- H. Weyl. Gravitation and Electricity. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, , 465–480 (1918).

- F. W. Hehl, Y. N. Obukhov. Foundations of Classical Electrodynamics: Charge, Flux, and Metric. Birkhäuser, (2003).

- L. Fabbri. Torsion Gravity for Dirac Fields. Annalen der Physik 2014, 526, 93–106.

- Y. Mohammadi, J. Tabatabaei, S. Baghram. Schwarzschild Spacetime and the Local Limit of Nonlocal Gravity. arXiv preprint 2025.

- H. W. Chiang, S. Garcia-Saenz, A. Sang. Black hole destabilization via trapped quasinormal modes. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 024011.

- S. Paul, S. K. Maurya, J. Kumar. Stability and existence of wormhole models in F(Q) gravity. Nucl. Phys. B 2025, 990, 116886.

- N. R. Ghosh, M. K. Nandy. Regular Schwarzschild Black Hole in Modified Gravity. arXiv e-prints, , (2025).

- M. Momennia, O. Sarbach. Spherical accretion of a collisionless kinetic gas into a generic static black hole. arXiv preprint 2025.

- G. Bianconi. The quantum relative entropy of the Schwarzschild black hole and the area law. Entropy 2025, 27, 266.

- A. Saavedra, G. Rubilar, O. Fierro, M. Gammon, R. B. Mann. Neutron stars in 4D Einstein-Gauss-Bonnet gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 064071.

- G. Antoniou, L. Gualtieri, P. Pani. Gravitational quasinormal modes of black holes in quadratic gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 064059.

- S. Nojiri, S. D. Odintsov. Black holes and their shadows in F(R) gravity. Phys. Dark Universe 2025, 43, 101243.

- S. A. Lafkih, N. A. Nilsson, M. C. Angonin. Perturbative black-hole and horizon solutions in gravity with explicit spacetime-symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 064060.

- K. Krasnov. Spinor Representation of General Relativity and Modified Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 124025.

- J. W. Moffat. Scalar–Tensor–Vector Gravity Theory as an Alternative to Dark Matter. Eur. Phys. J. C 2006, 47, 429–432.

- S. Hossenfelder. Covariant Version of Verlinde’s Emergent Gravity and MOND Phenomenology. Class. Quantum Grav. 2017, 34, 175015.

- S. Capozziello, M. De Laurentis, V. Faraoni. A bird’s eye view of f(R)-gravity. Open Astron. J. 2009, 2, 1874–3811.

- L. Fabbri. Torsion-Gravity for Dirac Fields and Its Renormalizability. Ann. Phys. 2012, 524, 77–104.

- S. Alexander, N. Yunes. Chern–Simons Modified Gravity and Its Applications. Phys. Rep. 2009, 480, 1–55.

- F. W. Hehl, Y. N. Obukhov. Spacetime metric from linear electrodynamics. Phys. Lett. A 2003, 311, 277–284.

- M. Blagojević, F. W. Hehl (Eds.). Gauge Theories of Gravitation. World Scientific 2013.

- M. Milgrom. MOND vs dark matter in light of the dwarf galaxy problem. Monthly Notices R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 454, 3810–3815.

- P. D. Mannheim. Alternatives to dark matter and dark energy. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2006, 56, 340–445.

- Famaey, J. Binney. Modified Newtonian Dynamics in the Milky Way. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 363, 603–608.

- J. D. Bekenstein, R. H. Sanders. TeVeS Cosmology: Covariant Formalism for Modified Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 73, 103513.

- S. McGaugh. A Tale of Two Paradigms: the Mutual Incommensurability of ΛCDM and MOND. Can. J. Phys. 2015, 93, 250–259.

- P. Kroupa, M. Pawlowski, M. Milgrom. The failures of the standard model of cosmology require a new paradigm. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2012, 21, 1230003.

- Merritt. Cosmology and convention. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. B 2017, 57, 41–52.

- M. Milgrom. MOND laws of galactic dynamics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 437, 2531–2541.

- L. Blanchet, L. Heisenberg. Dipolar dark matter with massive bigravity. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2015, 12, 026.

- G. W. Angus, B. Famaey, H. S. Zhao. Can MOND take a bullet? Analytical comparisons of three gravity theories. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 371, 138–146.

- R. E. G. Machado, T. F. Laganá, G. S. Souza. Simulating Nearly Edge-on Sloshing in the Galaxy Cluster Abell 2199. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 515, 581–595.

- R. Bender, J. Kormendy, M. E. Cornell. Cluster Velocity Dispersion of the Abell 2199 cD Halo of NGC 6166. Astrophys. J. 2015, 807, 56.

- Bettoni, M. Arnaboldi, O. Gerhard. Kinematics of the Diffuse Intragroup and Intracluster Light. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 630, A36.

- S. I. Loubser, A. Babul, H. Hoekstra. Dynamical Masses of Brightest Cluster Galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 496, 1857–1871.

- M. Hilker et al.. Kinematics in the Hydra I Cluster Core (Abell 1060). Astron. Astrophys. 614, A36 (2018).M. Arnaboldi, O. Gerhard. Kinematics in Local Galaxy Clusters within 100 Mpc. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 9, 872283.

- A. Boyarsky, O. Ruchayskiy, D. Iakubovskyi. New Evidence for Dark Matter from Cluster Rotation Curves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 091301.

- M. J. West, A. Dekel, A. Oemler Jr.. Profiles of Clusters of Galaxies: Cosmological Models vs Observations. Astrophys. J. 1987, 316, 1–17.

- D. Carter, T. J. Bridges, G. K. T. Hau. Kinematics and Origin of Brightest Cluster Galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1999, 307, 131–144.

- R. H. Sanders. A Faber-Jackson Relation for Clusters of Galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 284, L31–L34 (1994).S. Ettori, P. Tozzi, P. Rosati, S. Borgani. Mass Profiles of Galaxy Clusters from X-Ray Data. Astron. Astrophys. 2004, 417, 13–27.

- J. E. Taylor, A. Babul. The Dynamics of Baryons and Dark Matter in Galaxy Clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 364, 535–552.

- C. Fedeli, M. Bartelmann. Cluster Mass Profiles from Weak Lensing. Astron. Astrophys. 2007, 461, 49–59.A. Diaferio, M. J. Geller. Infall Regions of Galaxy Clusters. Astrophys. J. 1997, 481, 633–652.

- Tajmar, M., & de Matos, C. J. Gravitomagnetic field of a rotating superconductor and of a rotating superfluid. Physica C: Superconductivity 2003, 385, 551–554.

- Tajmar, M., & de Matos, C. J). Extended analysis of gravitomagnetic fields in rotating superconductors and superfluids. Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications 2005, 420, 56–60.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).