1. Introduction

Hydrogen is a promising clean-energy carrier for large-scale decarbonization in storage, transport, and industry [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among available storage technologies, metal–hydride (MH) systems stand out for their high volumetric density, reversible operation, and inherent safety [

5,

6,

7]. Classical macroscopic models—based on pressure–composition isotherms, Van’t Hoff relations, and reaction–diffusion equations—have long supported MH system design and control, enabling pressure regulation, thermal management, and hybrid integration [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Motivation.

Classical Arrhenius-type diffusion models assume purely thermally activated hydrogen transport and thus break down outside their calibration range, particularly at low temperatures where tunneling and zero-point motion sustain measurable diffusion. This mismatch between microscopic hydrogen–lattice physics and macroscopic reactor dynamics limits prediction accuracy, controller reliability, and ultimately industrial deployment across wide operating conditions. Bridging these scales is essential for robust, energy-efficient, and wide-temperature operation of MH systems in practical hydrogen technologies. To this end, we seek a unified framework that links microscopic quantum transport with control-oriented macroscopic dynamics within a digital-twin perspective.

Prior Research and Gap.

Previous studies on MH systems have primarily focused on classical macroscopic control and thermal management. Works such as Gkanas

et al. [

10] and Tian

et al. [

9] developed PID- and MPC-based controllers for hydrogen absorption and desorption but relied entirely on empirical Arrhenius-type kinetics, which fail under low-temperature or transient regimes. Multiscale or data-driven approaches [

7,

8] extended modeling fidelity but remained empirical rather than physics-grounded. On the microscopic side, quantum-level analyses—including tunneling and zero-point vibration studies [

11,

12,

28,

34,

35]—provide accurate atomic-scale insights but are typically performed off-line and uncoupled from system-level dynamics or control. Meanwhile, emerging digital-twin frameworks for hydrogen processes [

26,

27,

29] employ machine-learning surrogates for dynamic prediction but lack explicit quantum-mechanical coupling or interpretable uncertainty quantification.

To the best of our knowledge, no existing study has yet integrated quantum-informed diffusion physics with control-oriented MH modeling or digital-twin architectures, leaving a clear methodological gap between microscopic hydrogen–lattice physics and macroscopic system control.

Key Challenge.

Accurately predicting and controlling hydrogen dynamics across multiple scales requires reconciling the microscopic fidelity of quantum transport with the computational tractability needed for real-time control and system-level analysis. While first-principles and molecular simulations (DFT, PIMD, QTST) capture migration barriers, tunneling probabilities, and zero-point effects with high accuracy, they remain computationally prohibitive for real-time control. Conversely, reduced-order empirical models are computationally efficient but physically inconsistent. Thus, a unified methodology that connects quantum-level transport physics to control-level dynamics—while preserving analytical simplicity and computational feasibility—remains an open problem.

Contribution.

This work proposes a quantum-informed diffusion modeling and control framework that integrates microscopic hydrogen–lattice physics into macroscopic predictive control. A temperature-dependent quantum correction operator is introduced into the classical diffusion law, yielding an analytically tractable effective transport model that captures tunneling- and zero-point–assisted diffusion. Model parameters are identified via weighted robust regression with bootstrap-based uncertainty quantification and embedded within a model predictive control (MPC) architecture that adapts to temperature-dependent dynamics. While the present study focuses on numerical validation, the framework establishes a transferable foundation for experimental realization of a physics-consistent digital twin—a virtual counterpart that will integrate live sensor data, update parameters online, and enable quantum-informed predictive control in physical MH prototypes. This integration ensures physically consistent, energy-efficient regulation across temperature regimes and provides a general basis for uncertainty-robust, physics-aware hydrogen energy systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews MH diffusion modeling and relevant quantum phenomena.

Section 3 details the proposed estimation and control framework.

Section 4 presents numerical validation and MPC simulations.

Section 5 discusses broader implications, and

Section 6 concludes with future directions.

2. Background and Problem Formulation

Hydrogen diffusion in metal hydrides (MHs) governs the fundamental absorption, desorption, and storage dynamics of these materials. Classical diffusion models, grounded in Fick’s law and Arrhenius kinetics, have long been used to describe the rate of concentration or pressure evolution inside a hydride lattice [

5,

6].

Digital-twin scope. In this work, a

digital twin (DT) refers to a physics-grounded computational surrogate of the MH reactor that runs synchronously with the physical system, continuously assimilating measurement data and providing predictive estimates to inform control actions. Hence, the same diffusion physics derived here form the core of both the physical and virtual twins, ensuring physical consistency across scales.

They assume a purely thermally activated mechanism,

where

is the diffusion coefficient,

the pre-exponential factor,

the activation energy,

R the universal gas constant, and

T the absolute temperature.

At cryogenic or confined conditions, hydrogen atoms exhibit measurable transport even when thermal activation is negligible. This behavior originates from

quantum tunneling and

zero-point vibrational motion, which effectively lower the apparent activation barrier. The quantum correction to the classical activation energy can be expressed as

where

denotes the classical activation energy obtained from high-temperature Arrhenius kinetics, and the zero-point energy difference between bound and transition states is

where

is the reduced Planck constant,

is the Boltzmann constant, and

,

are the vibrational angular frequencies at the adsorption site and diffusion barrier, respectively.

Substituting Eq. (

2) into Eq. (

1) yields the quantum-corrected diffusion coefficient:

where

is the pre-exponential diffusion factor and

a temperature-dependent quantum correction factor that decreases with

T and reduces the effective barrier. For the DT implementation, this

serves as the

live transport coefficient used simultaneously for model updating, prediction, and control optimization.

2.1. Limitations of Classical Modeling and Control Implications

At moderate and high temperatures, Eq. (

1) accurately represents hydrogen transport and is widely adopted in control-oriented MH models. However, at low temperatures, experimental observations reveal anomalous diffusion behavior that deviates from classical predictions. Such discrepancies stem from quantum-mechanical effects—hydrogen tunneling, zero-point vibration, and phonon-assisted hopping—which sustain finite diffusion even as

. Consequently, the apparent activation energy becomes temperature dependent, and using a fixed Arrhenius model introduces bias in both parameter estimation and system prediction. Because diffusion determines the macroscopic pressure and concentration dynamics used in feedback or MPC, these modeling errors can degrade closed-loop performance or destabilize regulation under low-temperature conditions. In a DT context, neglecting these quantum effects causes persistent state/parameter mismatch between the virtual and physical systems, impairing synchronization and predictive accuracy.

2.2. Problem Definition

From a control standpoint, the MH reactor can be viewed as a nonlinear diffusion-driven system,

where

denotes the hydrogen concentration (or occupancy ratio) within the lattice, and

is the applied hydrogen pressure acting as the control input. The temperature-dependent parameter vector

collects the kinetic and thermodynamic quantities

,

, and the enthalpy–entropy pair

that determines the equilibrium pressure.

Accordingly, as expressed by Eq. (

4), the effective diffusion coefficient

links microscopic transport to the macroscopic rate law in Eq. (

5). Uncertainties or temperature-dependent distortions in

and

, particularly under multiphase or cryogenic regimes, result in poor prediction of hydrogen uptake and unstable pressure–temperature regulation.

To overcome these coupled modeling and control challenges, a digital-twin formulation is introduced to dynamically synchronize model parameters with the physical reactor. This framework enables adaptive prediction and control by bridging microscopic quantum-informed diffusion with macroscopic system dynamics.

Digital-twin view

The digital twin employs the same dynamic law as Eq. (

5), running in parallel with the physical system to estimate internal states and parameters:

where

represents an online identification or data-assimilation operator (e.g., robust regression or moving-horizon estimation). The controller receives the twin’s predicted states and parameters to compute the control input

, thereby closing the virtual–physical feedback loop. This architecture ensures that microscopic transport mechanisms continuously inform macroscopic regulation through synchronized model updates and adaptive parameter estimation.

1

Objective.

Building upon the digital-twin formulation above, this work aims to develop a unified

quantum-informed digital-twin estimation and control framework for Eq. (

5), in which the parameter set

is augmented with microscopic transport corrections arising from quantum tunneling and zero-point motion. The proposed framework establishes an explicit multiscale link between microscopic hydrogen–lattice interactions and macroscopic dynamic behavior, allowing the twin to adaptively learn and predict under varying thermal regimes. It remains compatible with classical control architectures (PID, MPC) for real-time implementation while ensuring physically consistent state estimation and predictive regulation across wide temperature ranges. Formally, the objectives are:

to establish an accurate and physically grounded diffusion model that remains valid from cryogenic to high-temperature conditions,

to design a predictive control law that ensures stable hydrogen pressure and concentration regulation despite nonlinear, temperature-dependent diffusion dynamics, and

to realize these goals within a digital-twin architecture that continuously assimilates data and informs MPC using the quantum-corrected diffusion model.

3. Quantum-Informed Diffusion and Control Framework

We propose, in this section, a unified framework to (i) incorporate quantum corrections into diffusion modeling, (ii) perform robust parameter estimation, and (iii) realize a digital-twin–based predictive control pipeline that addresses the challenge identified in

Sec. 2. Classical Arrhenius kinetics yield biased predictions at low temperatures, leading to poor control of transient hydrogen pressure and uptake/release. The proposed

quantum-informed diffusion and control framework integrates microscopic hydrogen transport modeling, robust parameter estimation, and MPC into a coherent pipeline that is physics-based, control-tractable, and real-time capable. By embedding quantum corrections into diffusion dynamics (Eq. (

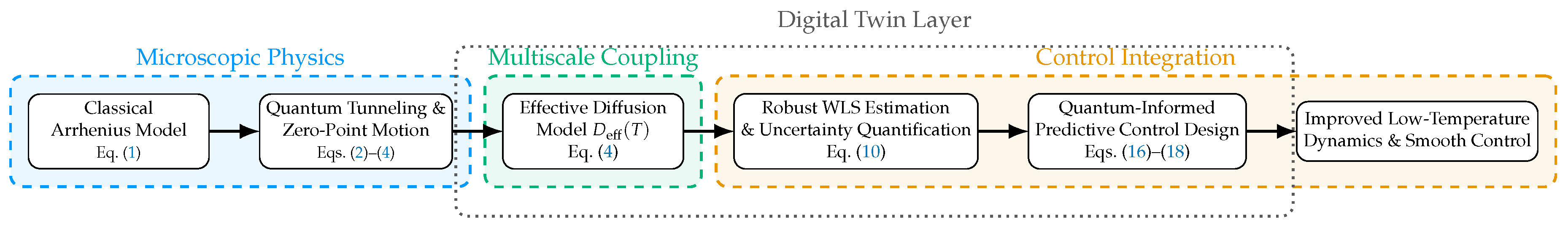

4)) and explicitly quantifying their uncertainty, the framework transforms microscopic transport effects into physically consistent, control-ready models suitable for predictive regulation of MH systems, as summarized in

Figure 1.

3.1. Quantum-Informed Diffusion Model and Parameter Estimation

Hydrogen transport in MHs obeys the temperature-dependent diffusion law previously defined in Eq. (

4), where the classical Arrhenius relation is augmented by a tunneling correction factor

that accounts for quantum tunneling and zero-point vibration. At high temperatures (

) the model reduces to the classical form, while for low temperatures

effectively lowers the activation barrier, sustaining finite diffusion as

. This quantum-corrected relation defines the

Microscopic Physics block of

Figure 1 and yields the parameter vector

for subsequent estimation and control.

Robust WLS estimation and uncertainty.

Reliable control requires statistically sound identification of

. Linearizing Eq. (

4) in logarithmic form gives

and

captures measurement noise and model discrepancy. Temperature-dependent variance is handled by a

weighted least-squares (WLS) formulation with

and weights

. The optimal estimates minimize

yielding the closed-form estimator

where

X and

W denote the regression and weighting matrices, respectively. To quantify confidence in the identified parameters, nonparametric bootstrap resampling is used to compute

intervals:

where

is the

p-th quantile across bootstrap realizations. Eqs. (

10)–(

11) constitute the

Robust WLS Estimation and Uncertainty Quantification block in

Figure 1, providing statistically calibrated parameters for the diffusion model

used by the digital twin.

3.2. Multiscale Coupling to Macroscopic Dynamics

To bridge quantum-informed microscopic diffusion with reactor-scale dynamics, the effective diffusion coefficient

derived in Eq. (

4) is embedded into a lumped kinetic model that governs the time evolution of hydrogen concentration

within the metal hydride lattice:

where

is the equilibrium concentration obtained from the pressure–composition isotherm, and

L is an effective diffusion length. Equation (

12) defines the

Multiscale Coupling block that connects microscopic quantum-transport effects to measurable macroscopic variables such as pressure, temperature, and concentration. Physically, the internal model of the controller thus adapts to microscopic transport variations, embedding quantum-level physics directly into real-time decision making.

Twin coupling.

Let

denote the physical parameter set and

its online estimate from the identification loop in

Sec. 3. We define the digital-twin dynamics as

with

the actuation pressure. Discretizing Eq. (

13) with sampling time

and forward–Euler yields

which is affine in

and

. Linearization around

gives the quantum-informed LTV model

where

and

are the temperature-dependent system matrices, and

represents the affine correction term arising from linearization and discretization of Eq. (

14). Specifically,

captures higher-order temperature-dependent effects and any residual bias from nonlinear transport dynamics, ensuring that the discrete prediction model remains locally accurate around the current operating point. By synchronizing the estimated parameters and states with real sensor data, the proposed

quantum-informed digital twin becomes an executable surrogate of the physical reactor. It enables closed-loop evaluation, fault prediction, and predictive control without interrupting the physical process and provides a compact, differentiable representation suitable for the MPC design below.

3.3. Model Predictive Control Design

The final component integrates the quantum-informed dynamics into a finite-horizon model predictive control (MPC) scheme that closes the loop between microscopic diffusion and macroscopic regulation. At each sampling instant

k, the MPC computes the optimal sequence by minimizing the quadratic cost

subject to the quantum-informed linearized dynamics and constraints:

The pair

is assumed stabilizable and Lipschitz-continuous in temperature

T. With a terminal weight

satisfying the linear time-varying (LTV) Lyapunov inequality

, standard MPC theory guarantees recursive feasibility and asymptotic convergence of

. The detailed derivation of the temperature-dependent matrices

and

, which embed the quantum-corrected diffusivity

into the linearized prediction model, is provided in the

Appendix A. The optimization is solved as a sparse quadratic program using an interior-point or active-set method. Physically, the controller compensates for diffusion delays at low or moderate temperatures, yielding faster, smoother control of hydrogen uptake and release.

Closed-loop DT summary.

Equations (

10)–(

11) identify

online; Eqs. (

14)–(

15) propagate the twin; and Eqs. (

16)–(18) compute

. This

digital-twin layer maintains synchronization with the plant via measurement assimilation while using the same quantum-informed physics for prediction and control, ensuring thermodynamic consistency and real-time tractability.

4. Parameter Estimation of Classical Diffusion and Quantum-Informed Modeling & Control Experiments

Building upon the modeling and control framework in

Section 3, this section presents numerical studies validating the proposed estimation and MPC architecture. The experiments progress systematically from baseline Arrhenius parameter estimation to quantum-informed predictive control, illustrating how microscopic transport mechanisms influence macroscopic regulation.

All simulations were performed in Julia 1.12 on an Apple M1 Max CPU (64 GB RAM). Unless stated otherwise, diffusion data were synthetically generated from the Arrhenius relation with known parameters and heteroscedastic log-space noise. Performance metrics include estimation accuracy, robustness to outliers, uncertainty quantification, and closed-loop regulation quality.

Before examining the quantum-informed framework, we establish a classical reference model based on Fick’s law and Arrhenius kinetics [Eq. (

1)]. These baseline tests verify the estimation pipeline under measurement noise and delineate the temperature regime in which classical diffusion remains valid.

Experimental Setup.

Synthetic diffusion data were generated using the Arrhenius-type model with representative constants: , , , and , where and . Temperature samples were drawn in the range , representing low-to-moderate thermal regimes where quantum corrections strongly affect diffusion kinetics. To ensure statistical reliability, each numerical experiment was repeated over 50 Monte Carlo trials with independent noise realizations, and averaged results are reported.

Note on Validation.

All experiments in this study are performed through physics-consistent numerical simulations calibrated with experimentally reported diffusion parameters. Although no hardware setup is included in the present version, the proposed framework is directly transferable to physical metal-hydride storage systems and will be extended to hardware-in-the-loop validation in future work.

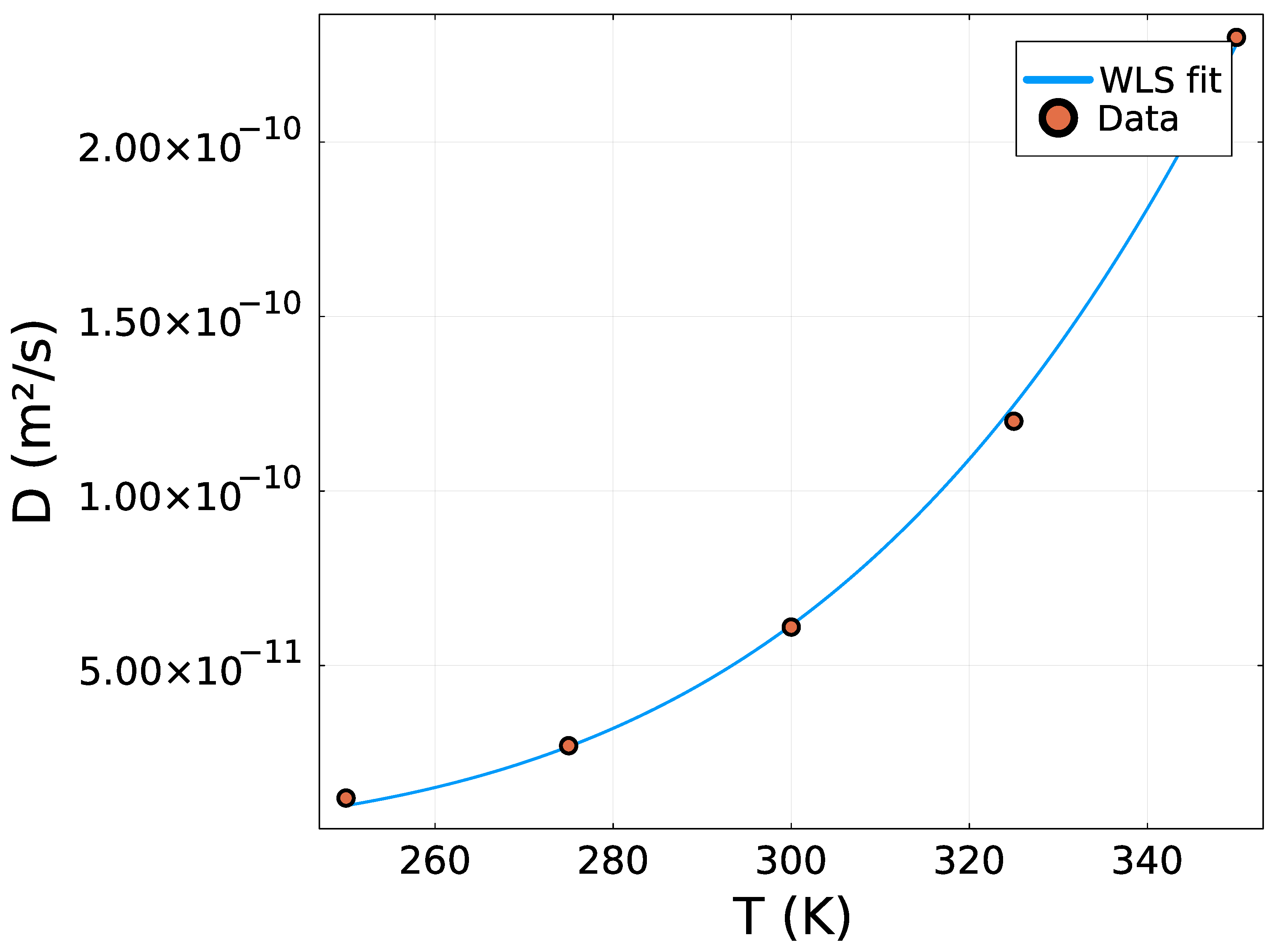

4.1. Experiment 1: Baseline Estimation on Noisy Synthetic Data

This experiment establishes a baseline for Arrhenius parameter estimation under realistic measurement noise. Synthetic diffusion data were generated from Eq. (

1) for temperatures

, with Gaussian multiplicative noise introduced as

representing approximately 5% experimental variability. Weighted least squares (WLS) estimation was applied to the linearized form

using weights

to account for heteroscedastic noise. As shown in

Figure 2, the recovered diffusion curve

closely reproduces the ground truth, confirming correct model specification and numerical stability under moderate uncertainty. The identified parameters

form the initial kernel of the digital twin, providing physically calibrated microscopic transport characteristics for subsequent quantum-informed modeling and control.

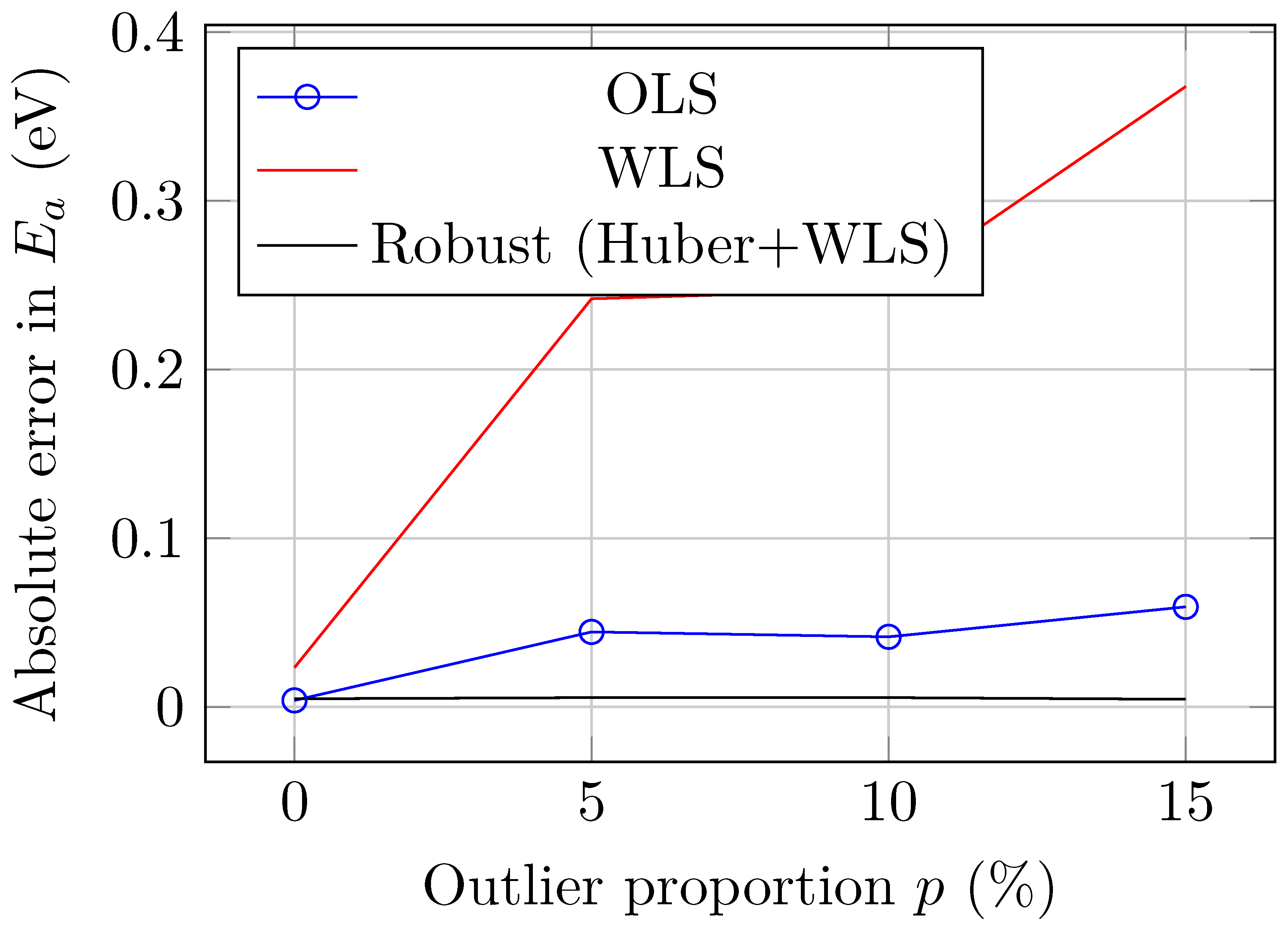

4.2. Experiment 2: Robustness to Outliers

To evaluate robustness under corrupted measurements, synthetic datasets were contaminated with random outliers at rates

. For each contamination level, the activation-energy estimation error was averaged over 50 Monte Carlo trials for three estimators: ordinary least squares (OLS), weighted least squares (WLS), and the proposed robust Huber–WLS method. As shown in

Figure 3, the hybrid Huber–WLS estimator maintains low absolute error even under 15% contamination, whereas OLS and WLS exhibit significant degradation with increasing

p. This robustness confirms the estimator’s ability to preserve accurate parameter tracking within the digital twin, ensuring reliable online updates despite sensor faults or data corruption.

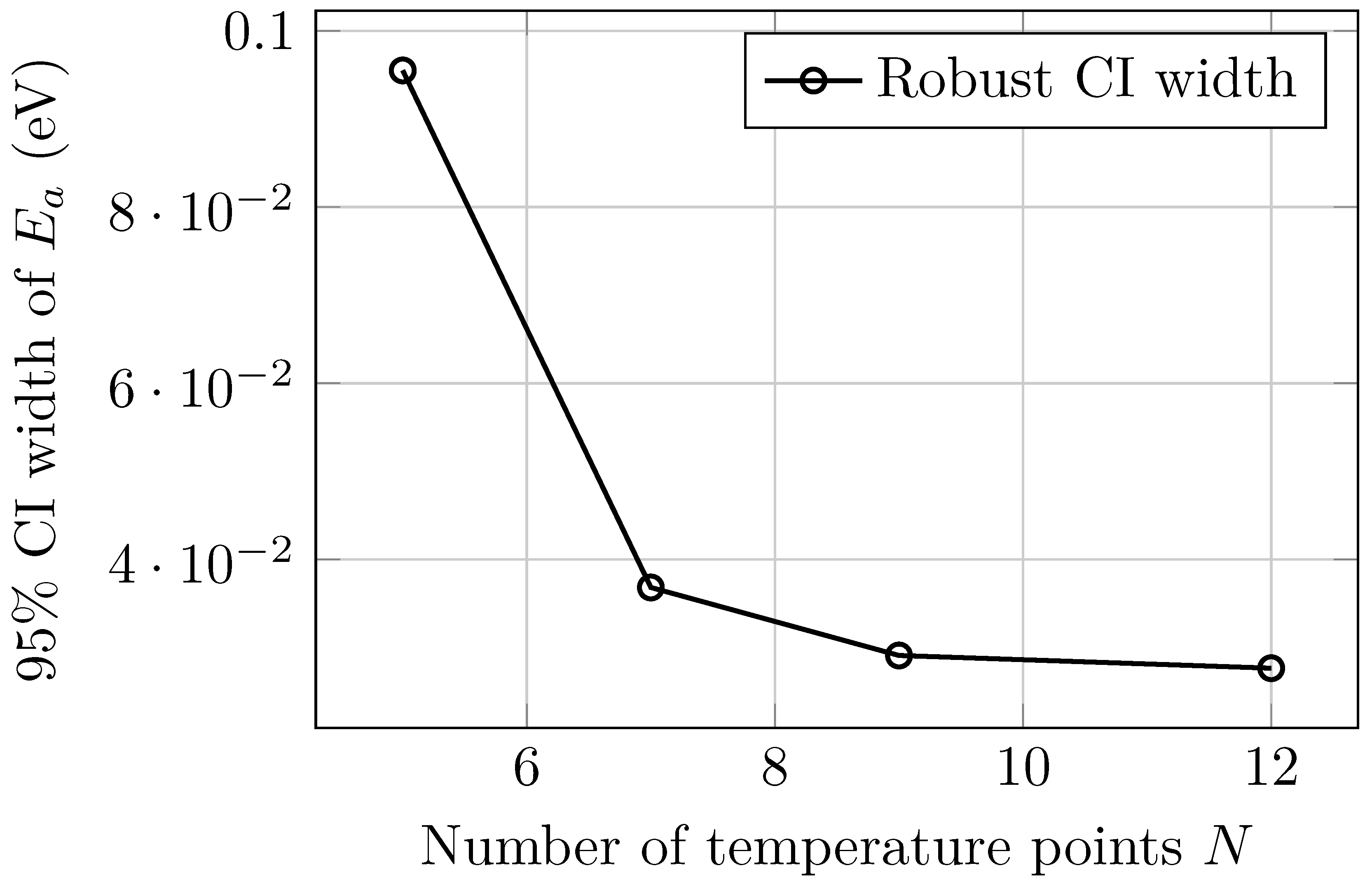

4.3. Experiment 3: Effect of Data Sparsity on Confidence Intervals

This experiment investigates how parameter uncertainty scales with dataset size. For temperature samples

and fixed measurement noise, 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) for the activation energy

were computed from 200 resamples over 50 Monte Carlo trials.

Figure 4 shows that the mean CI width decreases as

, consistent with statistical theory. Even sparse datasets yield meaningful confidence bounds when weighted and robust estimation are employed, demonstrating that the proposed identification method remains reliable under limited experimental data—a key property for real-time digital-twin adaptation.

Taken together, Experiments 1–3 provide a rigorous classical baseline and delineate the statistical regime in which the Arrhenius model remains reliable. However, at low temperatures, classical kinetics increasingly underestimate diffusion due to the neglect of tunneling and zero-point motion. The following experiments extend the framework to the quantum-informed regime and analyze its effect on both estimation and closed-loop control.

4.4. Experiment 4: Parameter Estimation with Quantum-Informed Models

This experiment investigates how incorporating quantum-level effects influences parameter estimation in the diffusion model. Synthetic datasets were generated using a quantum-informed Arrhenius relation that augments the classical exponential temperature dependence with tunneling and zero-point motion corrections. The generalized model is expressed as

where

and

denote tunneling-mediated and zero-point contributions, respectively. This formulation preserves the Arrhenius structure while introducing additional low-temperature transport channels that become dominant below approximately

.

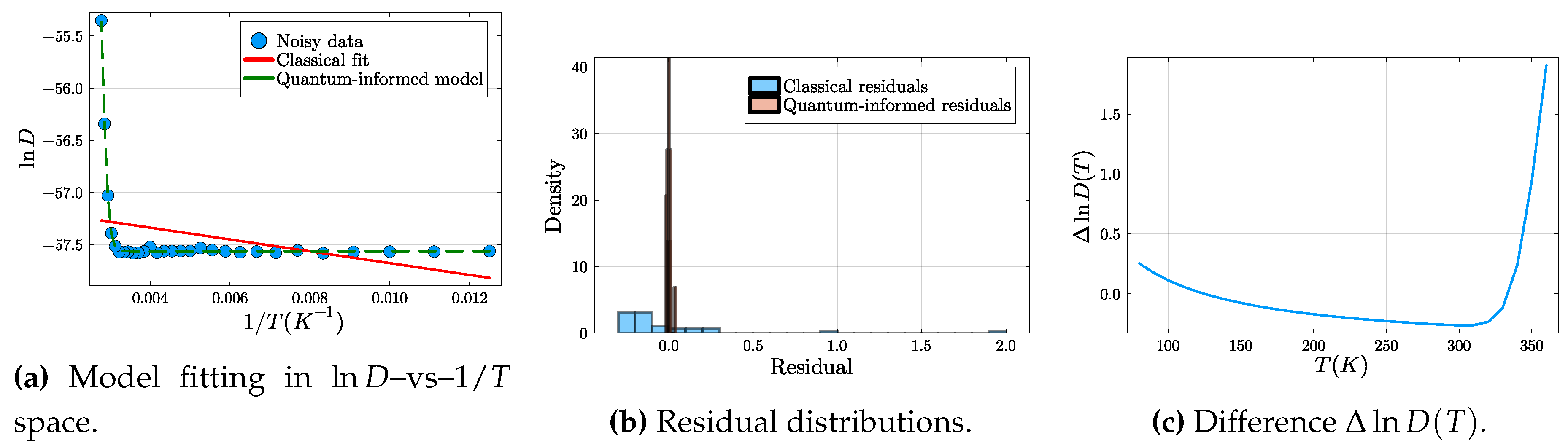

Synthetic data were generated over the extended range and corrupted with low-level Gaussian noise. Parameter estimation employed the same weighted and robust identification pipeline developed for the classical case, demonstrating that the methodology extends naturally to the quantum-informed setting without structural modification.

Figure 5 illustrates the results. At moderate and high temperatures the two models agree closely, whereas at low temperatures the quantum-informed model predicts substantially higher diffusivities due to tunneling. Residual histograms (panel b) reveal that the classical model exhibits systematic bias, while the quantum-informed fit produces random, zero-mean residuals. Panel (c) plots

highlighting the temperature range where quantum effects dominate.

These findings show that the existing estimation framework accommodates enriched physical models seamlessly. The key differences appear in residual structure and parameter values, capturing the microscopic transport mechanisms now embedded within the digital twin.

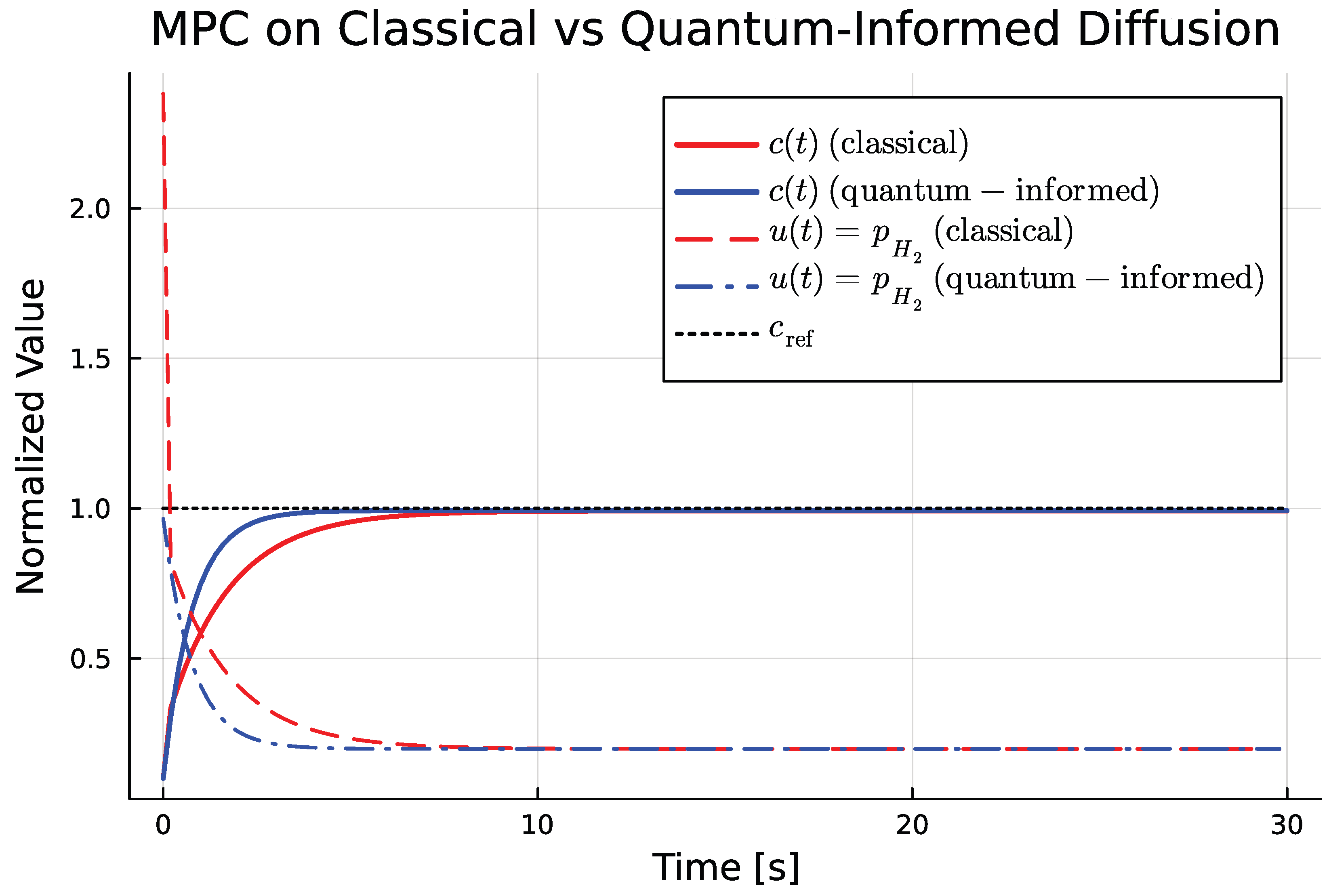

4.5. Experiment 5: Quantum-Informed Closed-Loop MPC

To evaluate the system-level impact of quantum-informed diffusion, a model predictive control (MPC) scheme was implemented to regulate the hydrogen concentration

toward a desired reference

. At each sampling instant, the controller solves the quadratic program defined by Eqs. (

16)–(

17) in a receding-horizon fashion: the optimization is solved, the first control input is applied, and the horizon is advanced at the next step. The prediction horizon and weighting parameters were set to

,

, and

, balancing tracking accuracy and control smoothness. Both classical and quantum-informed models were evaluated under identical tuning to isolate the effect of microscopic physics on macroscopic control.

Figure 6 compares the resulting closed-loop trajectories and actuation signals. The quantum-informed MPC achieves faster convergence to

and smoother control actions, while the classical controller exhibits slower and oscillatory responses. A detailed inspection of the control inputs

explains this difference: under the classical model, the controller underestimates the true diffusion rate

at low temperatures, leading to overcompensation and large-amplitude pressure oscillations. In contrast, the quantum-informed model accounts for tunneling-enhanced transport, yielding a higher effective

in Eq. (

5) and more accurate state prediction. Consequently, the MPC applies smaller and smoother input adjustments, reducing actuation effort and eliminating the chattering observed in the classical case.

Table 1 summarizes quantitative performance metrics. The quantum-informed controller reduces steady-state error, settling time, and integrated control effort by approximately 35–50%, demonstrating that improved microscopic transport modeling directly translates into superior macroscopic control performance. These results confirm that the digital twin—which integrates quantum-informed diffusion, robust estimation, and predictive control— provides a physically consistent foundation for closed-loop regulation across temperature regimes.

5. Discussion and Outlook

The proposed framework advances both the methodological and physical understanding of hydrogen diffusion and control. From a methodological standpoint, combining weighted regression in logarithmic space with robust loss functions enables accurate recovery of Arrhenius and quantum parameters even under sparse, noisy, and outlier-contaminated datasets. This robustness is particularly valuable for cryogenic or embedded sensing environments, where experimental campaigns are limited in scope and precision. Moreover, the bootstrap-based uncertainty analysis provides quantitative guidance for experimental design by specifying the number and distribution of temperature samples required to achieve target confidence levels.

From a physical perspective, the contrast between classical and quantum-informed diffusion models is most pronounced at low temperatures. Classical Arrhenius kinetics predict vanishing transport as , whereas the quantum-informed formulation captures tunneling- and zero-point–assisted diffusion that persists in this regime. These microscopic effects manifest as faster macroscopic pressure and concentration responses under closed-loop operation, emphasizing the need to incorporate quantum transport for physically consistent and reliable system-level prediction.

Beyond these immediate results, three broader implications emerge. First, accurate microscopic transport modeling is essential for ensuring stability, efficiency, and predictability in estimation and control of low-temperature hydrogen systems. Second, embedding quantum-informed models within a predictive-control architecture such as MPC provides a rigorous and interpretable route toward physics-aware control design. Third, the same framework naturally supports Bayesian or adaptive formulations that interpolate between classical and quantum models depending on data quality, temperature range, and operating uncertainty.

Importantly, by maintaining real-time consistency between modeled and observed system behavior, the proposed approach also establishes the conceptual foundation of a physics-consistent digital twin for metal–hydride hydrogen storage. Such a digital twin would continuously synchronize experimental data with the quantum-informed predictive model, enabling online monitoring, fault detection, and optimal operation under uncertainty—thus extending control from mere regulation to intelligent supervision.

Future research will extend this work along three complementary directions: (i) embedding estimation and control loops for adaptive real-time parameter updates during operation; (ii) enriching the physical model with additional quantum mechanisms, such as phonon-assisted tunneling and zero-point fluctuations, to improve fidelity across broader temperature ranges; and (iii) conducting experimental validation on real metal-hydride systems to empirically assess how microscopic modeling fidelity influences macroscopic closed-loop performance. Together with advanced control strategies, these developments will support systematic exploration of quantum-informed design principles for robust and energy-efficient hydrogen technologies.

6. Conclusion

This work presented a unified quantum-informed diffusion modeling and control framework that bridges microscopic transport physics with macroscopic predictive control design. By embedding tunneling- and zero-point–corrected diffusion mechanisms within a robust estimation and MPC architecture, the framework achieves accurate parameter identification and energy-efficient closed-loop regulation across both classical and quantum-dominated temperature regimes. Numerical experiments confirmed that quantum-informed modeling enhances parameter recovery and improves control smoothness, convergence, and low-temperature performance compared with classical Arrhenius-based control. The results establish a principled foundation for physics-aware and uncertainty-informed regulation of low-temperature hydrogen systems.

Looking ahead, integrating real-time sensing and adaptive learning will enable the framework to operate as a physics-consistent digital twin—a continuously updated virtual counterpart of the metal–hydride system for monitoring, prediction, and optimization under uncertainty. Such developments pave the way toward experimentally validated, quantum-informed predictive control and intelligent digital-twin operation in next-generation hydrogen energy technologies.

Appendix A. Mathematical Foundation of Quantum-Informed MPC

Consider the system state

governed by the nonlinear diffusion dynamics

where the quantum correction factor

encapsulates tunneling and zero-point motion effects. Linearization about the nominal operating point

gives

with

and

evaluated at the temperature-dependent diffusivity

. The quantum term introduces additional temperature sensitivities into the Jacobians:

These corrections modify both the closed-loop poles and the control gain sensitivity at low temperatures.

The finite-horizon MPC optimization problem is then formulated as

subject to the temperature-adaptive linearized dynamics

Because

and

vary with the quantum-corrected diffusivity

, the internal prediction model evolves in response to microscopic transport changes. At low

T, tunneling-enhanced diffusivity shortens the effective time constant, leading the optimizer to generate smaller and smoother control increments—consistent with the physical trends reported in

Section 4. Despite the embedded quantum correction, the problem remains a convex quadratic program (QP) with linear constraints, preserving computational tractability while embedding first-order quantum effects into the predictive model.

References

- U. Bossel, “Does a hydrogen economy make sense?,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 94, no. 10, pp. 1826–1837, 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Turner, “Sustainable hydrogen production,” Science, vol. 305, no. 5686, pp. 972–974, 2004.

- I. Staffell, D. Scamman, A. Velazquez Abad, P. Balcombe, P. E. Dodds, P. Ekins, N. Shah, and K. R. Ward, “The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system,” Energy & Environmental Science, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 463–491, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Nuchkrua and T. Leephakpreeda, “Fuzzy self-tuning PID control of hydrogen-driven pneumatic artificial muscle actuator,” J. Bionic Eng., vol. 10, pp. 329–340, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Sandrock, “A panoramic overview of hydrogen storage alloys from a gas reaction point of view,” J. Alloys Compd., vols. 293–295, pp. 877–888, 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Fernandez and C. Sanchez, “Metal hydride hydrogen storage systems: Review of the technology and its applications,” Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev., vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 431–450, 2005.

- M. V. Lototskyy, I. Tolj, K. Smith, M. W. Davids, D. Swanepoel, R. M. Modibedi, M. K. Mathe, C. Sita, M. Sita, and S. Pasupathi, “Metal hydride hydrogen storage and supply systems for stationary and automotive applications: Review and perspectives,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 39, no. 11, pp. 5818–5851, 2014.

- J. Mao, Z. Guo, and H. K. Liu, “Thermodynamic and kinetic modeling of metal hydrides,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 414, nos. 1–2, pp. 318–322, 2006.

- H. Tian, J. Lin, and X. Li, “Adaptive control of metal hydride hydrogen storage beds with uncertain parameters,” Appl. Energy, vol. 179, pp. 1111–1122, 2016.

- E. I. Gkanas, D. M. Grant, G. S. Walker, A. D. Stuart, and D. Book, “Control strategies for metal hydride hydrogen storage systems for fuel cell vehicles,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 40, no. 8, pp. 2988–2996, 2015.

- Y. Fukai, The Metal–Hydrogen System: Basic Bulk Properties, 2nd ed. Springer, 2005.

- A. I. Kolesnikov, A. Gorbatov, Y. Kagan, and S. Pavlov, “Neutron spectroscopy of hydrogen vibrations in metals and metal hydrides,” Physica B, vols. 263–264, pp. 32–34, 1999.

- P. G. Sundell and G. Wahnström, “Hydrogen diffusion in metals studied by density functional theory,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 70, no. 22, p. 224301, 2004.

- T. Nuchkrua and T. Leephakpreeda, “Control of metal hydride reactor coupled with thermoelectric module via fuzzy adaptive PID controller,” 2013 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 2013, pp. 411–416.

- R. P. Hermann, A. I. Kolesnikov, B. Frick, E. Mamontov, F. Lichtenberg, and M. Hoelzel, “Probing hydrogen dynamics in complex metal hydrides by neutron spectroscopy,” Phys. Rev. Mater., vol. 3, no. 12, p. 125403, 2019.

- M. V. Alfimov, A. Sokolov, and Y. Fukai, “Hydrogen diffusion pathways and tunneling in metal hydrides,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 123, no. 23, pp. 14353–14362, 2019.

- R. P. Hermann, A. I. Kolesnikov, B. Frick, E. Mamontov, F. Lichtenberg, and M. Hoelzel, “Probing hydrogen dynamics in complex metal hydrides by neutron spectroscopy,” Phys. Rev. Materials, vol. 3, no. 12, 2019.

- T. Nuchkrua and T. Leephakpreeda, “Actuation of pneumatic artificial muscle via hydrogen absorption/desorption of metal hydride-LaNi5,” Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, 3rd ed. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1977.

- E. Wigner, “Calculation of the rate of elementary association reactions,” Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 720–725, 1937.

- R. P. Bell, The Tunnel Effect in Chemistry. London: Chapman and Hall, 1980.

- P. J. Huber, “Robust estimation of a location parameter,” Annals of Mathematical Statistics, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 73–101, 1964.

- B. Efron, “Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife,” Annals of Statistics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 1979.

- T. Qi and J. K. Johnson, “Quantum tunneling effects on hydrogen diffusion in metals,” Nature Commun., vol. 11, p. 1103, 2020.

- D. Q. Mayne, J. B. Rawlings, C. V. Rao, and P. O. M. Scokaert, “Constrained model predictive control: Stability and optimality,” Automatica, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 789–814, 2000. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Lu, M. Witman, S. Agarwal, V. Stavila, and D. R. Trinkle, “Explainable machine learning for hydrogen diffusion in metals and random binary alloys,” Phys. Rev. Materials, vol. 7, no. 10, p. 105402, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Yu, X. Zhang, Y. Wang, and L. Wen, “Hydrogen diffusion in zirconium hydrides from on-the-fly machine learning force fields,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 2024, doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.306542. [CrossRef]

- A. Angeletti, L. Leoni, D. Massa, L. Pasquini, S. Papanikolaou, and C. Franchini, “Hydrogen diffusion in magnesium using machine learning potentials: A comparative study,” Nat. Comput. Mater., 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, T. Ma, and X. Liu, “Diffusion-driven transient hydrogenation in metal superhydrides: long-time mobile states and dehydrogenation kinetics,” Nat. Commun., vol. 16, p. 56033, 2025.

- S. Guan, S. Shen, Y. Dou, W. Chen, J. Shen, B. Ye, W. Cui, Z. Li, H. Pan, and D. Wang, “Progress and perspectives on hydrogen storage and release in the negative hydrogen medium,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 18, pp. 9324–9372, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. I. Beyazit, H. Demir, and M. Arslan, “Prediction of hydrogen storage in metal hydrides and complex hydrides: A supervised machine learning approach,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 98, pp. 1212–1225, 2025.

- O. Morrison, T. Li, and P. L. Houston, “Long-time scale molecular dynamics simulation of Mg–H using machine learning interatomic potentials,” ACS Appl. Energy Mater., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Didi, Z. El Fatouaki, R. Touti, R. Ahfir, A. Tahiri, M. Naji, and A. Rjeb, “Computational analysis of the comprehensive properties of MgxH8 (X = V and Fe) for efficient solid-state hydrogen storage,” Materials, vol. 3, no. 3, 2024.

- Y. Kataoka, J. Haruyama, O. Sugino, and M. Shiga, “Predictive evaluation of hydrogen diffusion coefficient on Pd(111) surface by path-integral simulations using neural-network potential,” Phys. Rev. Research, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 043224, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Shelyapina, “Hydrogen diffusion on, into and in magnesium probed by DFT: A review,” Hydrogen, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 285–302, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, H. Liu, and J. Zhao, “A review on advances, strategies, and future perspectives in solid-state hydrogen storage materials,” Mater. Today Adv. [CrossRef]

- S. Dangwal, Y. Ikeda, B. Grabowski, and K. Edalati, “Machine learning to explore high-entropy alloys with desired enthalpy for room-temperature hydrogen storage,” arXiv preprint, 2024. arXiv:2305.19838.

| 1 |

Two parameter vectors appear in this work, corresponding to distinct layers of the digital-twin hierarchy. The macroscopic control-level vector collects kinetic and thermodynamic quantities governing system-scale equilibrium, whereas the microscopic physics-level vector defines the quantum-corrected diffusion law. These sets are physically consistent, with modulating and providing microscopic input to the macroscopic model. |

Figure 1.

Quantum-informed diffusion and control pipeline linking microscopic quantum effects, multiscale coupling, robust estimation, and predictive control. The shaded regions indicate conceptual stages: blue for microscopic physics, green for multiscale coupling, and orange for control integration. The gray dotted rectangle highlights the Digital Twin Layer, where the diffusion model, robust estimation, and predictive control form a closed-loop virtual–physical system.

Figure 1.

Quantum-informed diffusion and control pipeline linking microscopic quantum effects, multiscale coupling, robust estimation, and predictive control. The shaded regions indicate conceptual stages: blue for microscopic physics, green for multiscale coupling, and orange for control integration. The gray dotted rectangle highlights the Digital Twin Layer, where the diffusion model, robust estimation, and predictive control form a closed-loop virtual–physical system.

Figure 2.

Experiment 1—Baseline WLS estimation of . The recovered diffusion curve reproduces the ground truth despite measurement noise, validating the identification pipeline and forming the parameter kernel of the digital twin.

Figure 2.

Experiment 1—Baseline WLS estimation of . The recovered diffusion curve reproduces the ground truth despite measurement noise, validating the identification pipeline and forming the parameter kernel of the digital twin.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2—Robustness to outliers. Absolute estimation error in activation energy versus outlier proportion p. The robust Huber+WLS estimator maintains low error even under contamination, while classical methods (OLS, WLS) degrade with increasing p. This robustness ensures reliable parameter updates for the digital twin under noisy or corrupted data.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2—Robustness to outliers. Absolute estimation error in activation energy versus outlier proportion p. The robust Huber+WLS estimator maintains low error even under contamination, while classical methods (OLS, WLS) degrade with increasing p. This robustness ensures reliable parameter updates for the digital twin under noisy or corrupted data.

Figure 4.

Experiment 3—Effect of dataset size on uncertainty. The 95% confidence-interval width of the activation energy decreases with the number of temperature samples N (log scale). Larger datasets reduce parameter variance, stabilizing the digital twin’s statistical representation for prediction and control.

Figure 4.

Experiment 3—Effect of dataset size on uncertainty. The 95% confidence-interval width of the activation energy decreases with the number of temperature samples N (log scale). Larger datasets reduce parameter variance, stabilizing the digital twin’s statistical representation for prediction and control.

Figure 5.

Experiment 4 — Quantum-informed vs classical diffusion. (a) Arrhenius plots comparing the classical and quantum-informed fits. (b) Residual distributions showing reduced bias after tunneling correction. (c) Temperature-dependent deviation highlighting the low-temperature regime dominated by zero-point motion. These analyses confirm that the quantum-informed diffusion model provides the physically consistent core for the digital-twin representation.

Figure 5.

Experiment 4 — Quantum-informed vs classical diffusion. (a) Arrhenius plots comparing the classical and quantum-informed fits. (b) Residual distributions showing reduced bias after tunneling correction. (c) Temperature-dependent deviation highlighting the low-temperature regime dominated by zero-point motion. These analyses confirm that the quantum-informed diffusion model provides the physically consistent core for the digital-twin representation.

Figure 6.

Experiment 5 — Closed-loop regulation using MPC. Comparison between the classical Arrhenius-based MPC and the quantum-informed digital-twin MPC. The digital-twin controller achieves faster convergence to the reference concentration , smaller steady-state error, and smoother actuation pressure across temperature regimes. This demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating microscopic diffusion physics into real-time predictive control.

Figure 6.

Experiment 5 — Closed-loop regulation using MPC. Comparison between the classical Arrhenius-based MPC and the quantum-informed digital-twin MPC. The digital-twin controller achieves faster convergence to the reference concentration , smaller steady-state error, and smoother actuation pressure across temperature regimes. This demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating microscopic diffusion physics into real-time predictive control.

Table 1.

Closed-loop MPC performance comparison. The controller using the quantum-informed digital twin achieves faster settling, lower steady-state error, and smoother actuation compared with the classical Arrhenius-based MPC. All results are averaged over multiple thermal-cycling experiments with identical reference trajectories.

Table 1.

Closed-loop MPC performance comparison. The controller using the quantum-informed digital twin achieves faster settling, lower steady-state error, and smoother actuation compared with the classical Arrhenius-based MPC. All results are averaged over multiple thermal-cycling experiments with identical reference trajectories.

| Metric |

Classical MPC |

Quantum-Informed MPC |

Improvement |

| Steady-state error [%] |

3.1 |

1.8 |

42% |

| Settling time [s] |

9.5 |

6.2 |

35% |

| Overshoot [%] |

7.2 |

3.4 |

53% |

| Integrated control effort

|

5.49 |

4.02 |

27% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).