3.1. AtGRP7 Positively Regualte Seed Vigor

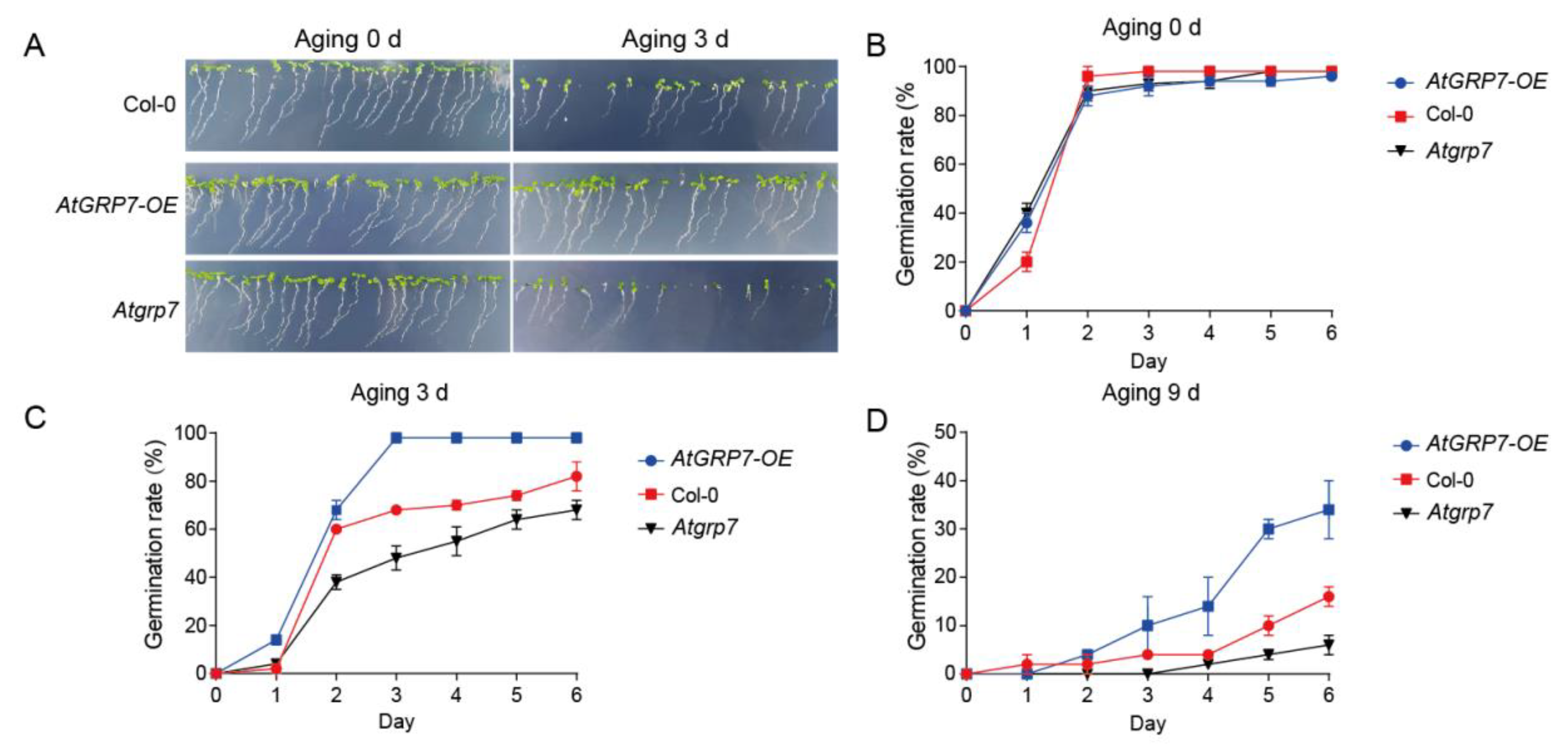

In previous research, we identified an RNA-binding protein, AtGRP7, involved in stress responses in

Arabidopsis thaliana [

15,

17]. To further investigate its biological function in maintaining seed vigor, we conducted systematic artificial accelerated aging experiments using wild-type (Col-0),

AtGRP7-overexpression (

AtGRP7-OE), and

atgrp7 mutant seeds. Germination rate analysis showed that all genotypes exhibited similarly high germination levels under untreated conditions (0 d;

Figure 1A, B), indicating no significant differences in initial seed viability among the genotypes. However, after 3 days of artificial aging treatment, distinct phenotypic differences emerged: the

AtGRP7-OE lines maintained strong germination capacity and normal seedling establishment, comparable to the non-aged control group, whereas the

atgrp7 mutant showed the most severe decline in viability, with significantly reduced germination rates (

Figure 1A, C). When the aging period was extended to 9 days, the genotypic differences became more pronounced:

AtGRP7-OE seeds consistently exhibited significantly higher germination rates than the wild-type control, while the

atgrp7 mutant displayed the lowest germination level among all lines (

Figure 1D). These time-course experimental results demonstrate that AtGRP7, actively participates in maintaining seed vigor under artificial aging stress and functions as a positive regulator in this process.

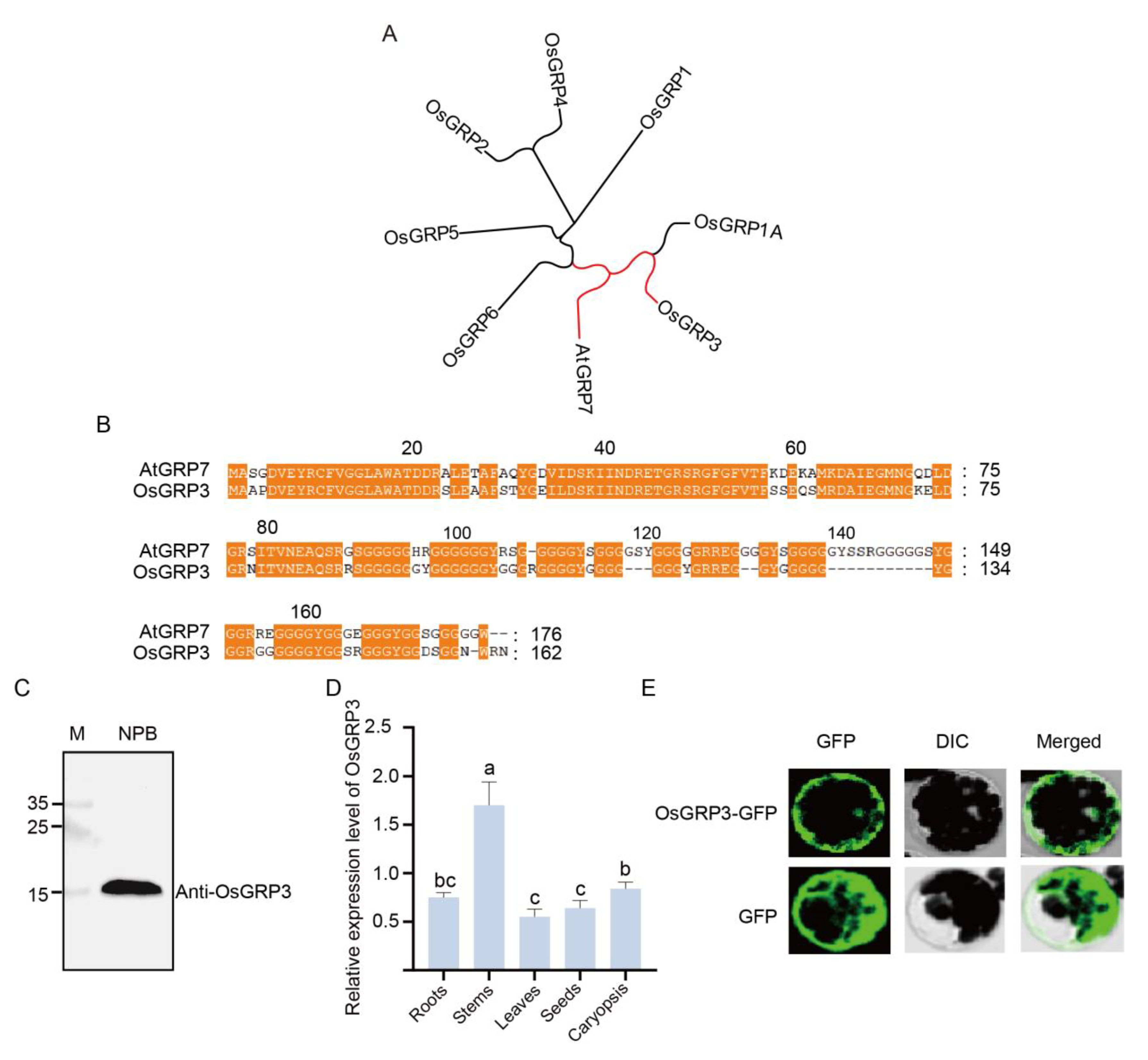

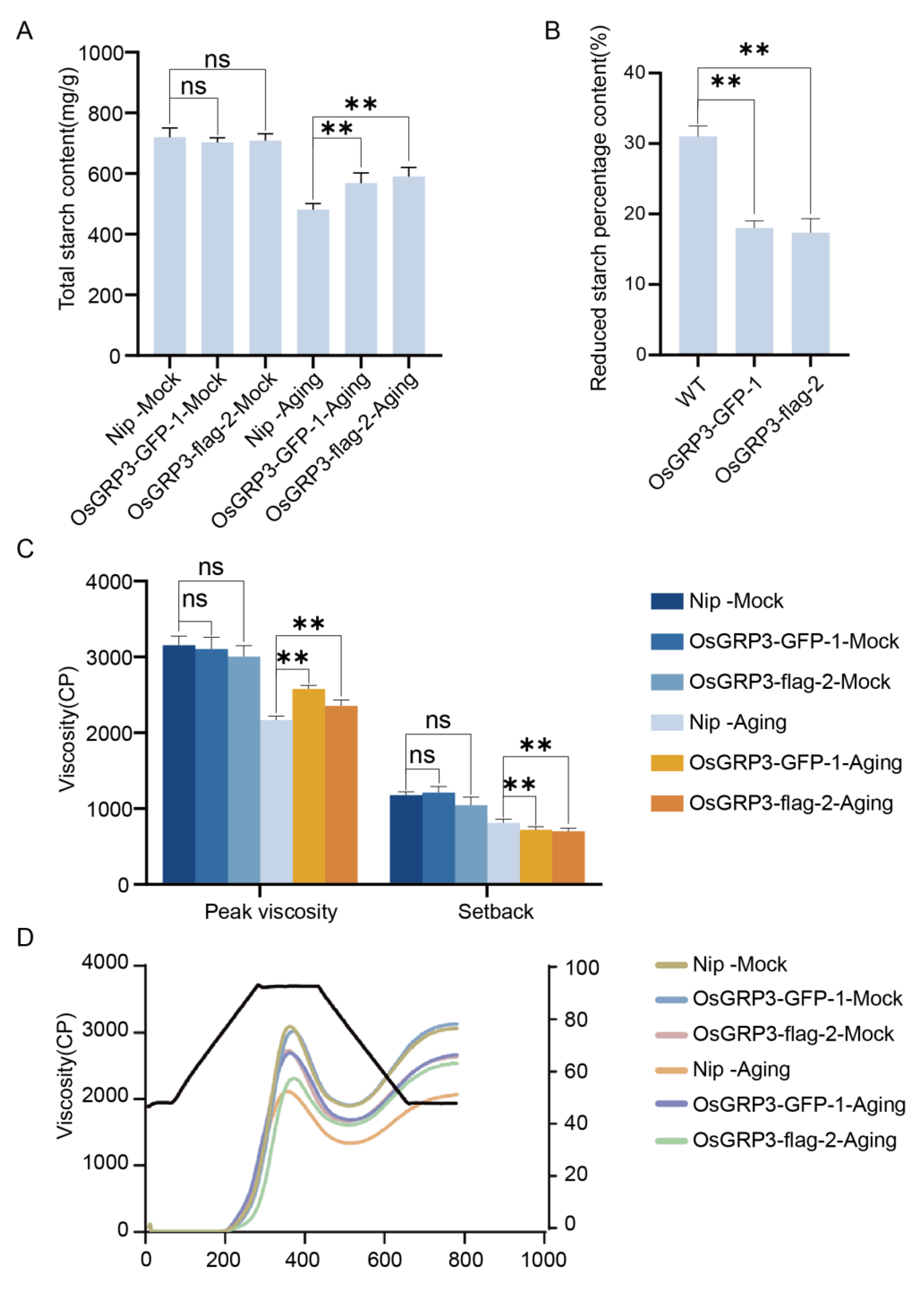

3.2. The Homologous Gene of AtGRP7, OsGRP3, Is Expressed in Rice

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that OsGRP3 shares the closest evolutionary relationship with AtGRP7 (

Figure 2A, red marker), suggesting potential functional conservation between these two proteins. Further protein sequence alignment demonstrated multiple highly conserved regions between OsGRP3 and AtGRP7 (

Figure 2B, orange highlights), particularly within the N-terminal domain, indicating that OsGRP3 likely maintains structural and functional characteristics similar to AtGRP7.

To determine whether OsGRP3 is expressed in seeds, we employed an endogenous antibody for detection. A single clear band of the expected molecular weight was detected in the Nipponbare (Nip) cultivar (

Figure 2C), confirming that OsGRP3 is normally expressed in rice seeds. Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed distinct expression patterns, with the highest abundance in stems, followed by caryopses and roots, while relatively lower levels were observed in leaves and seeds (

Figure 2D). Subcellular localization experiments revealed that the OsGRP3-GFP fusion protein was distributed throughout the cell, consistent with our previously reported localization pattern of AtGRP7 (

Figure 2E). Collectively, phylogenetic and experimental analyses demonstrate that OsGRP3 represents a functional homolog of AtGRP7 in rice, and its expression in seeds suggests a potential role in seed vigor.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship, sequence alignment, expression pattern, and subcellular localization of rice OsGRP3. A, Phylogenetic analysis of GRP family members from rice and Arabidopsis thaliana AtGRP7. The red branch highlights the close evolutionary relationship between AtGRP7 and OsGRP3. B, Amino acid sequence alignment of AtGRP7 and OsGRP3. Conserved domains, indicative of potential functional similarity, are marked by orange boxes. C, Immunoblot validation of the OsGRP3 protein. Lane M represents the protein molecular weight marker, and Nip serves as the negative control. A specific band for OsGRP3 confirms its detection. D, Analysis of relative OsGRP3 expression levels across different rice tissues (root, stem, leaf, and hypocotyl). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences among the tissue groups (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). E, Subcellular localization of the OsGRP3-GFP fusion protein (upper panel) compared to the GFP-only control (lower panel). Images from left to right show the GFP green fluorescence channel, DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) imaging, and the merged image. The localization pattern demonstrates the specific subcellular distribution of OsGRP3.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship, sequence alignment, expression pattern, and subcellular localization of rice OsGRP3. A, Phylogenetic analysis of GRP family members from rice and Arabidopsis thaliana AtGRP7. The red branch highlights the close evolutionary relationship between AtGRP7 and OsGRP3. B, Amino acid sequence alignment of AtGRP7 and OsGRP3. Conserved domains, indicative of potential functional similarity, are marked by orange boxes. C, Immunoblot validation of the OsGRP3 protein. Lane M represents the protein molecular weight marker, and Nip serves as the negative control. A specific band for OsGRP3 confirms its detection. D, Analysis of relative OsGRP3 expression levels across different rice tissues (root, stem, leaf, and hypocotyl). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences among the tissue groups (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). E, Subcellular localization of the OsGRP3-GFP fusion protein (upper panel) compared to the GFP-only control (lower panel). Images from left to right show the GFP green fluorescence channel, DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) imaging, and the merged image. The localization pattern demonstrates the specific subcellular distribution of OsGRP3.

3.3. OsGRP3 Positively Regualte Seed Vigor

To elucidate the biological function of OsGRP3 in maintaining rice seed vigor, we successfully generated two independent overexpression lines,

OsGRP3-GFP-1 and

OsGRP3-flag-2. Under normal growth conditions, the germination rates of transgenic lines and wild-type seeds were comparable (

Figure 3A, B), indicating that OsGRP3 overexpression does not affect the normal seed germination process. Following 20 days of artificial accelerated aging treatment, significant differences emerged among genotypes. Wild-type seeds showed a marked decline in germination rate, while both overexpression lines maintained higher germination capacity throughout the observation period (

Figure 3A, C). This difference became particularly pronounced during the later stages of treatment, suggesting that OsGRP3 overexpression effectively alleviates the damage caused by aging stress on seed germination capability. In addition, we assessed metabolic activity in seed embryos using TTC staining. The results revealed that after aging treatment, the embryos of overexpression lines exhibited more intense red staining (

Figure 3D), indicating preserved dehydrogenase activity and cellular metabolic function. This indicates that OsGRP3, similar to AtGRP7, positively regulates seed vigor in rice.

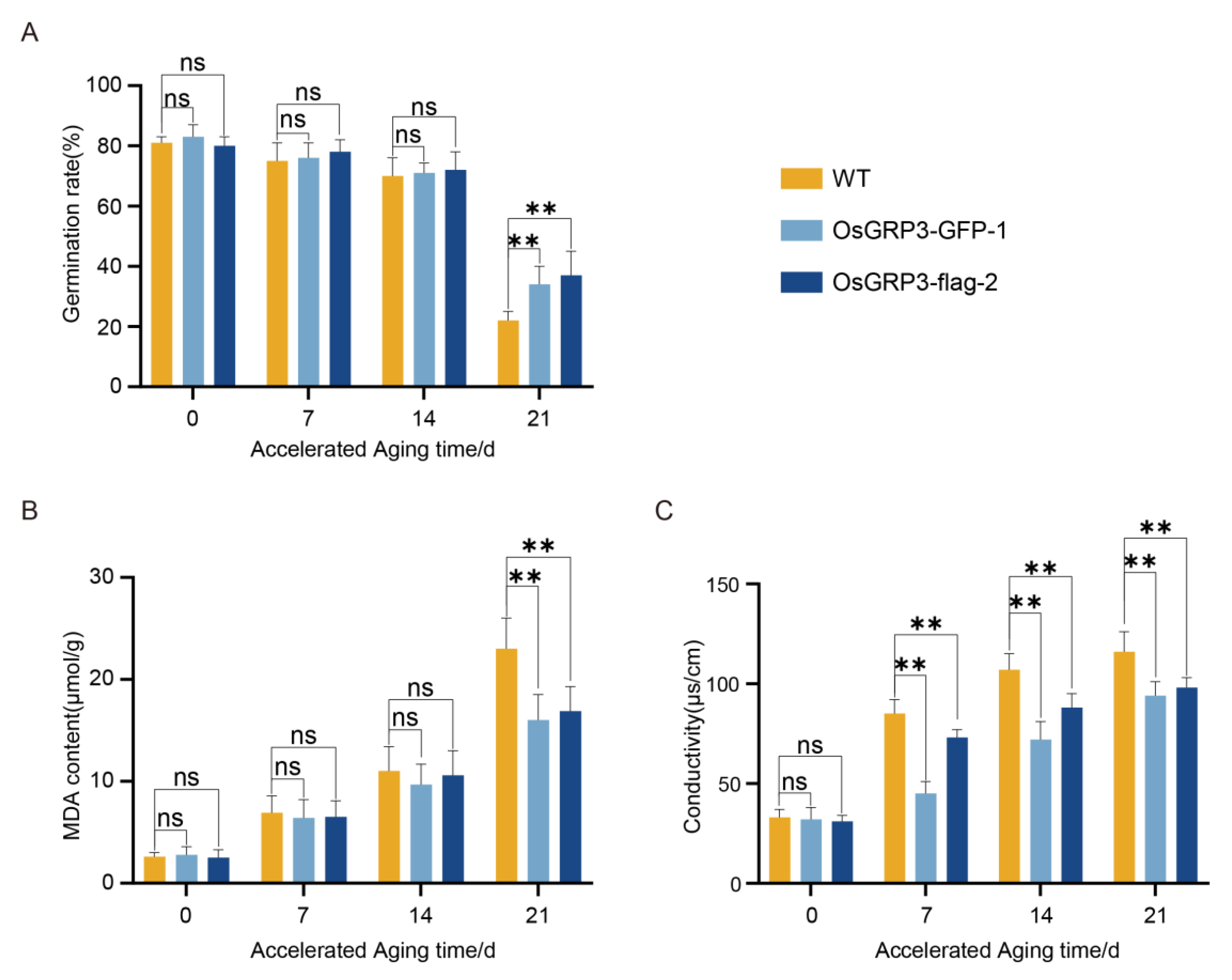

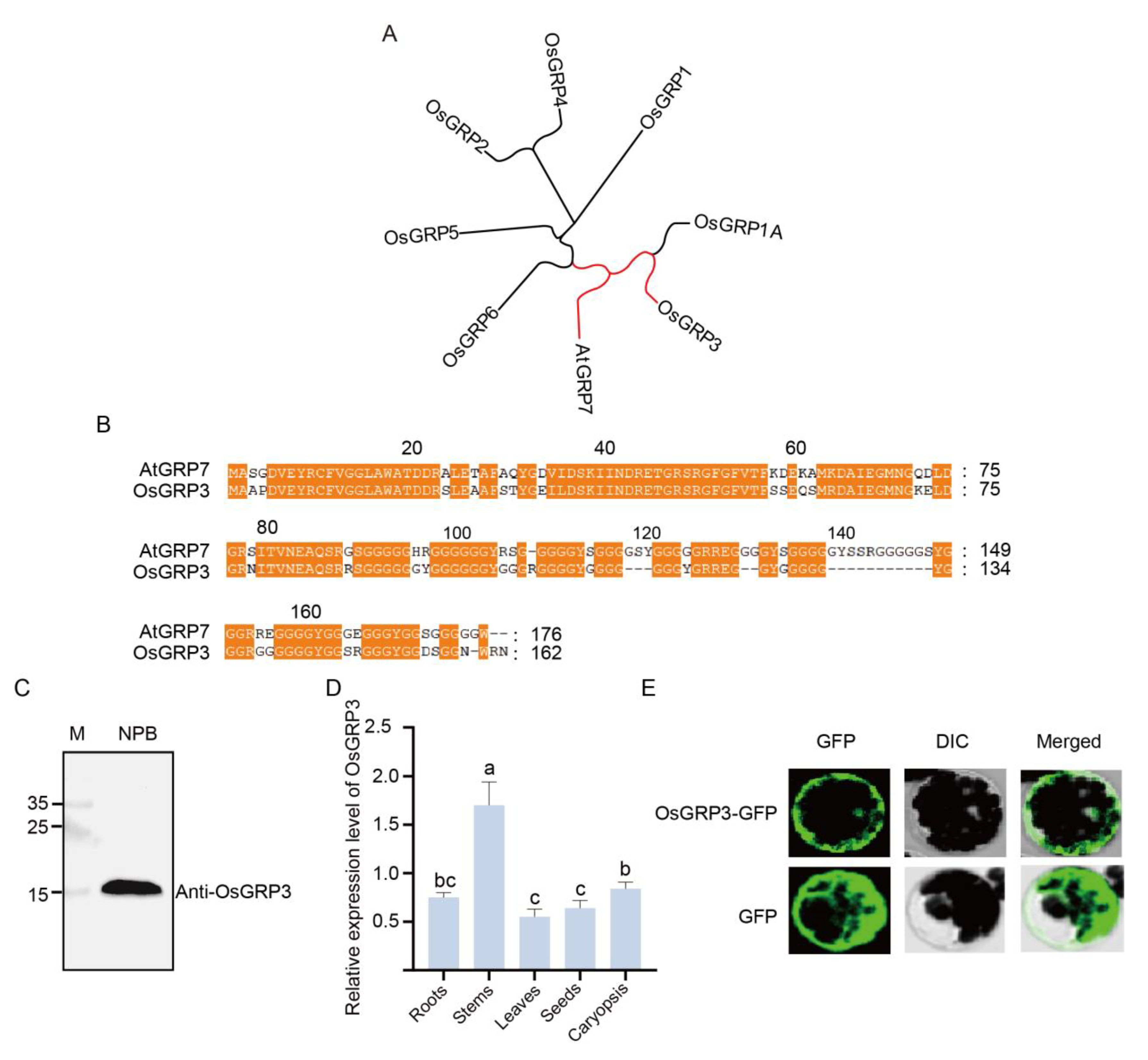

3.4. OsGRP3 Sustains Seed Vigor by Alleviating Membrane Damage During Prolonged Aging

To investigate the sustained protective effect of OsGRP3 under long-term storage conditions, we further analyzed its temporal characteristics during a 21-day accelerated aging process. At the initial stage of aging (0 d), all genotypes showed similarly high germination rates, indicating comparable initial viability among the different lines. However, as the aging process progressed, genotypic differences gradually emerged: wild-type seeds displayed a continuous decline in germination capacity, with a significant reduction observed by day 21. In contrast, both OsGRP3-overexpression lines maintained higher germination levels even during the later stages of aging (

Figure 4A), demonstrating their ability to sustainably preserve seed vigor.

Consistent with the germination phenotypes, further analysis of the physiological status of the seeds revealed the important role of OsGRP3 in mitigating aging-induced damage. Malondialdehyde (MDA), a key indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation [

24], showed continuously increasing levels in wild-type seeds throughout the aging period, but remained relatively low in transgenic lines even at day 21 (

Figure 4B). This result biochemically confirms that OsGRP3 overexpression effectively alleviates membrane lipid peroxidation damage caused by aging. Meanwhile, electrolyte leakage measurements, reflecting membrane integrity [

25], demonstrated significantly lower rates in overexpression lines compared to wild-type during the entire aging process (

Figure 4C), further supporting the crucial role of OsGRP3 in maintaining structural integrity of cell membranes. In summary, these results demonstrate that OsGRP3 enhances the germination of aged seeds while simultaneously mitigating aging-induced membrane damage and MDA accumulation.

Figure 4.

Effects of OsGRP3 overexpression on germination rate, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and electrolyte leakage in rice seeds during accelerated aging. A, Germination rates of wild-type (WT), OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds after 0, 7, 14, and 21 days of accelerated aging. No significant differences (ns) were observed at 0, 7, and 14 days. After 21 days of aging, the germination rate of WT seeds was significantly lower than that of the OsGRP3-overexpression lines (**p < 0.01), indicating that OsGRP3 overexpression enhances the ability to germinate following prolonged accelerated aging (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). B, MDA content in WT, OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds during accelerated aging. MDA levels showed no significant differences at 0, 7, and 14 days. After 21 days, WT seeds accumulated significantly more MDA than the overexpression lines, demonstrating that OsGRP3 overexpression reduces oxidative damage and helps maintain membrane integrity under severe aging stress (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). C, Electrolyte leakage measurements in WT, OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds during accelerated aging. No significant difference was detected at day 0. However, after 7, 14, and 21 days of aging, WT seeds exhibited significantly higher electrolyte leakage compared to the OsGRP3-overexpression lines, providing further evidence that OsGRP3 overexpression enhances membrane stability and reduces cellular leakage during the aging process (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates).

Figure 4.

Effects of OsGRP3 overexpression on germination rate, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and electrolyte leakage in rice seeds during accelerated aging. A, Germination rates of wild-type (WT), OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds after 0, 7, 14, and 21 days of accelerated aging. No significant differences (ns) were observed at 0, 7, and 14 days. After 21 days of aging, the germination rate of WT seeds was significantly lower than that of the OsGRP3-overexpression lines (**p < 0.01), indicating that OsGRP3 overexpression enhances the ability to germinate following prolonged accelerated aging (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). B, MDA content in WT, OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds during accelerated aging. MDA levels showed no significant differences at 0, 7, and 14 days. After 21 days, WT seeds accumulated significantly more MDA than the overexpression lines, demonstrating that OsGRP3 overexpression reduces oxidative damage and helps maintain membrane integrity under severe aging stress (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates). C, Electrolyte leakage measurements in WT, OsGRP3-GFP-1, and OsGRP3-flag-2 seeds during accelerated aging. No significant difference was detected at day 0. However, after 7, 14, and 21 days of aging, WT seeds exhibited significantly higher electrolyte leakage compared to the OsGRP3-overexpression lines, providing further evidence that OsGRP3 overexpression enhances membrane stability and reduces cellular leakage during the aging process (mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates).

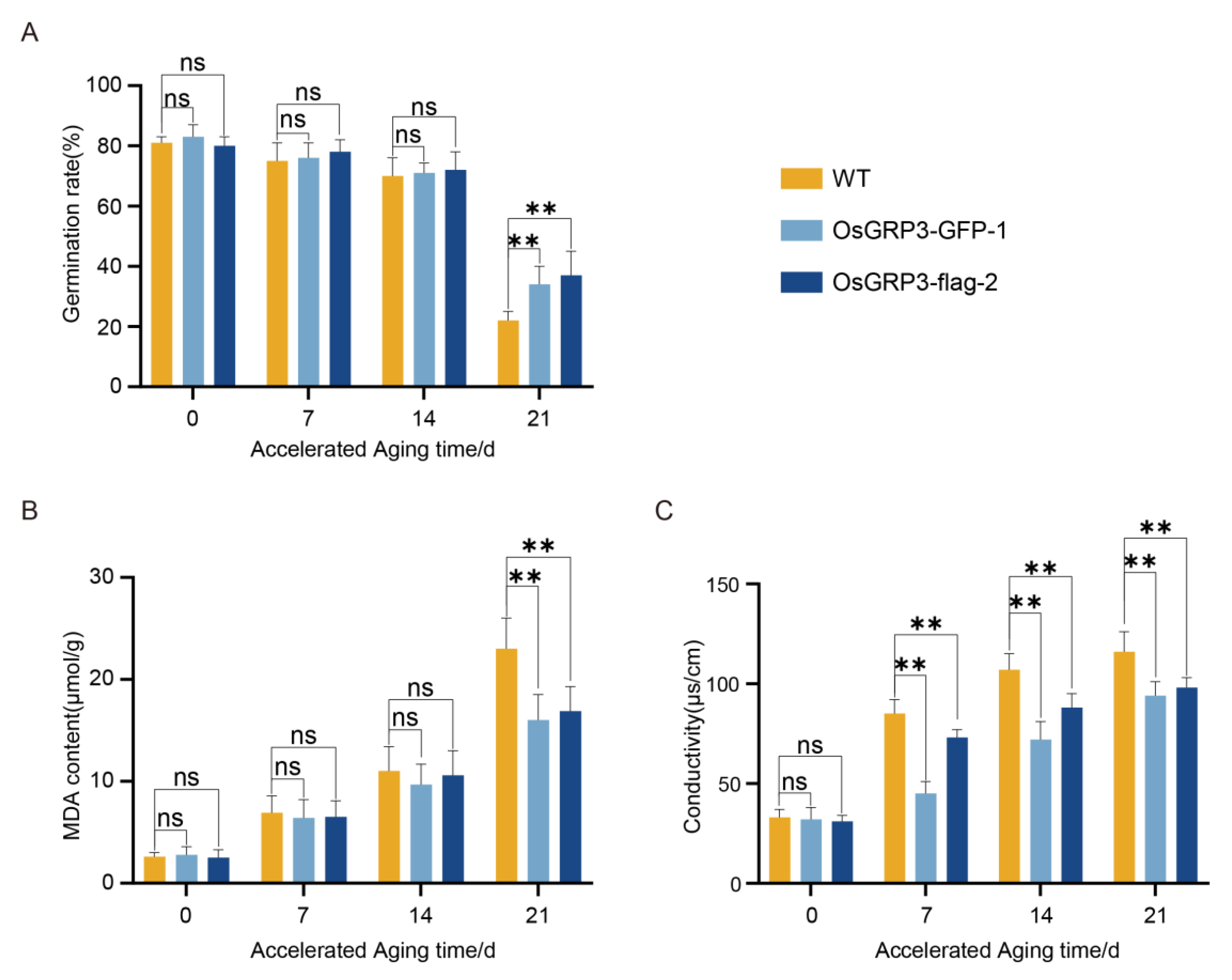

3.6. OsGRP3 Overexpression Attenuates mRNA-Level Changes During Aging

To elucidate the function of OsGRP3 in rice seed development and aging response, we performed RNA-seq analysis on mature seeds of wild-type (Nip) and OsGRP3 overexpression lines. The experimental design included untreated control groups and 15-day artificial accelerated aging treatment groups, with three biological replicates per condition.

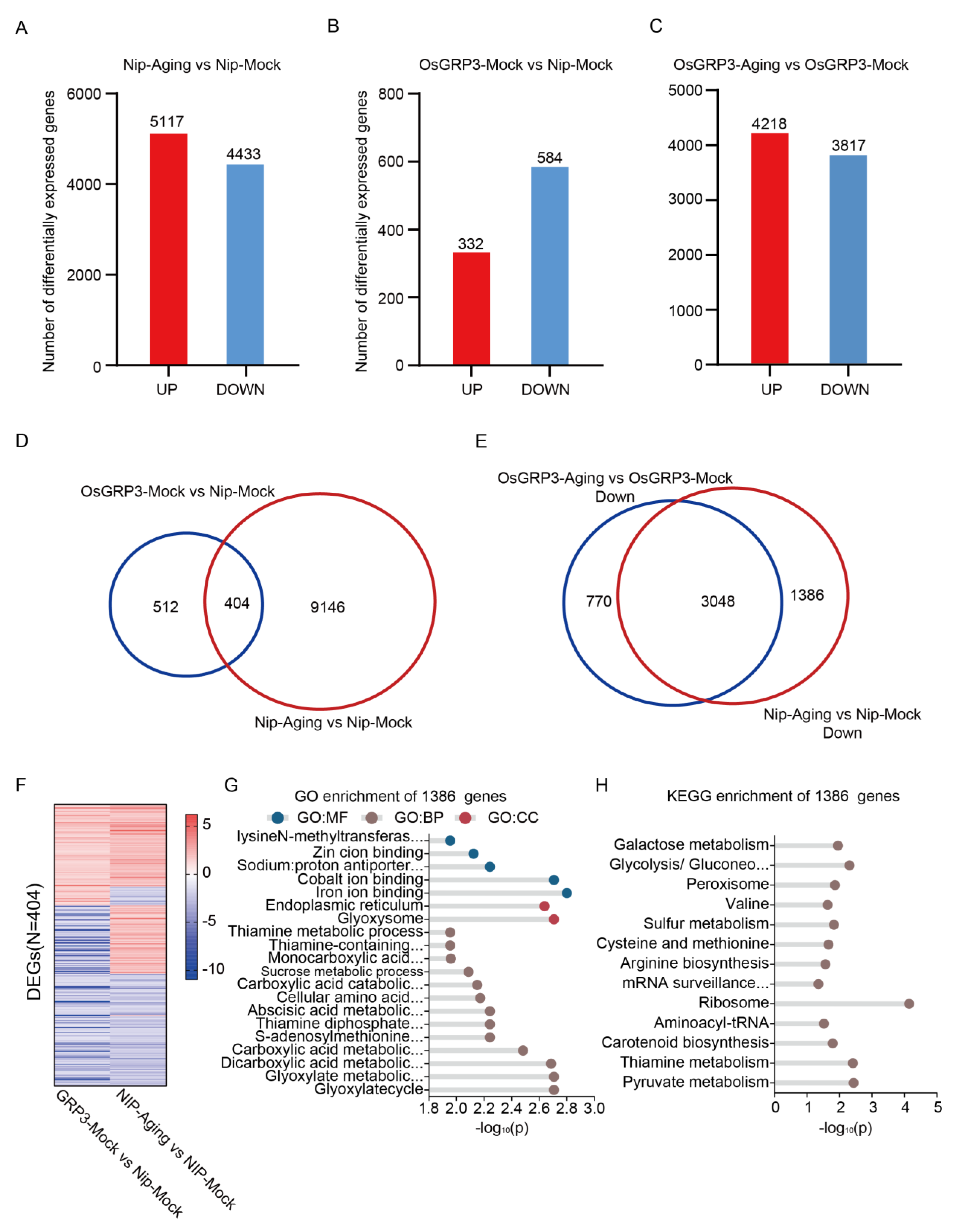

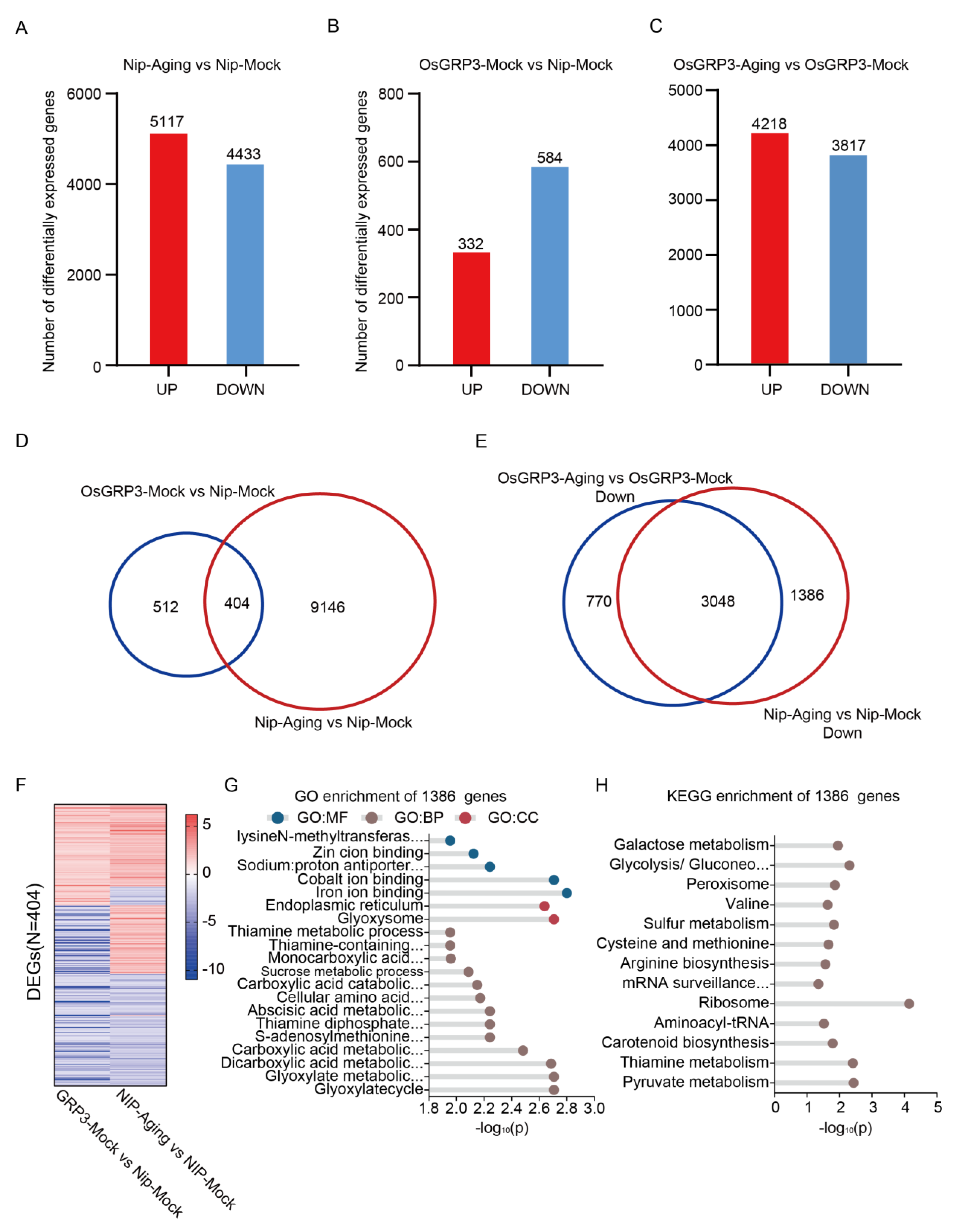

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed tight clustering of biological replicates across all materials, both before and after aging, confirming high reproducibility of the transcriptome data (

Figure S2). In wild-type seeds, aging stress induced extensive transcriptional reprogramming, with 5,117 genes up-regulated and 4,433 down-regulated (

Figure 6A). Notably, even under non-stress conditions, OsGRP3 overexpression alone modulated the expression of 916 genes (332 up, 584 down;

Figure 6B). Compared to wild-type, OsGRP3-overexpressing lines exhibited a more attenuated transcriptomic shift upon aging, with 4,218 genes up-regulated and 3,817 down-regulated (

Figure 6C), suggesting that OsGRP3 mitigates mRNA instability during seed aging.

We further identified a significant overlap between the 916 genes differentially expressed in OsGRP3-overexpressing lines under non-stress conditions and those altered in aged Nipponbare seeds, with 404 genes common to both sets (

Figure 6D). These overlapping genes were significantly enriched in key biological pathways such as DNA replication, gluconeogenesis, and essential amino acid metabolism (

Figure S3). Their consistent expression patterns under both conditions (

Figure 6F) indicate that OsGRP3 establishes a pre-adaptive molecular state in seeds, thereby enhancing their capacity to withstand subsequent aging stress.

Crucially, comparative analysis of downregulated genes revealed that a set of 1,386 genes exhibiting significant suppression in aged wild-type seeds were specifically preserved in aged OsGRP3 seeds (

Figure 6E). Functional enrichment analysis demonstrated that these genes were strongly associated with fundamental processes including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, peroxisome function, arginine biosynthesis, mRNA surveillance pathway, and pyruvate metabolism (

Figure 6G, H). Transcripts related to glycolysis and pyruvate metabolism are essential for energy provision during early germination, whereas those involved in ribosome biogenesis and mRNA surveillance contribute to the stability of long-lived mRNAs. Additionally, pathways such as carotenoid biosynthesis and sulfur metabolism help mitigate oxidative damage. Collectively, our transcriptomic profiling indicates that OsGRP3 sustains seed vigor by attenuating excessive mRNA degradation while selectively preserving long-lived mRNAs that are critical for the initial stages of germination.

Figure 6.

Transcriptomic analysis of seed aging and OsGRP3 overexpression in rice. A, Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the Nip-Aging and Nip-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 5,117 up-regulated and 4,433 down-regulated genes, respectively, indicating that the aging treatment triggers extensive changes in the gene expression profile. B, Number of DEGs (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the OsGRP3-Mock and Nip-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 332 up-regulated and 584 down-regulated genes, respectively, demonstrating that OsGRP3 overexpression itself alters the transcriptional landscape even in the absence of aging stress. C, Number of DEGs (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the OsGRP3-Aging and OsGRP3-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 4218 up-regulated and 3817 down-regulated genes, respectively, reflecting the substantial transcriptional differences under both OsGRP3 overexpression and aging treatment. D, Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs between the OsGRP3-Mock vs. Nip-Mock comparison (blue circle) and the Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparison (red circle). The two sets share 404 common DEGs, with 512 unique to the OsGRP3-Mock group and 9,146 unique to the Nip-Aging group. E, Venn diagram showing the overlap of down-regulated DEGs between the OsGRP3-Aging vs. OsGRP3-Mock comparison (blue circle) and the Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparison (red circle). The two sets share 3048 common down-regulated genes, with 770 unique to the OsGRP3 group and 1386 unique to the Nip group, suggesting both conserved and specific aspects in the aging-associated down-regulated genes modulated by OsGRP3. F, Heatmap displaying the expression patterns of alternative splicing events for the 404 common DEGs identified in both the OsGRP3-Mock vs. Nip-Mock and Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparisons. The color gradient represents expression level differences, visually presenting the consistent expression patterns of these common DEGs under both conditions. G, GO enrichment analysis of the 1386 unique DEGs. Significantly enriched terms are presented from three categories: Molecular Function (GO:MF), Cellular Component (GO:CC), and Biological Process (GO:BP). The x-axis shows the -log10(P), where higher values indicate greater enrichment significance. H, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 1,386 unique DEGs. The x-axis shows the -log10(P). The results reveal significant enrichment in pathways including Galactose metabolism, Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis, and Ribosome, suggesting these pathways may play key roles in OsGRP3-mediated aging regulation.

Figure 6.

Transcriptomic analysis of seed aging and OsGRP3 overexpression in rice. A, Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the Nip-Aging and Nip-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 5,117 up-regulated and 4,433 down-regulated genes, respectively, indicating that the aging treatment triggers extensive changes in the gene expression profile. B, Number of DEGs (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the OsGRP3-Mock and Nip-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 332 up-regulated and 584 down-regulated genes, respectively, demonstrating that OsGRP3 overexpression itself alters the transcriptional landscape even in the absence of aging stress. C, Number of DEGs (|log2FC| > 1, q < 0.01) between the OsGRP3-Aging and OsGRP3-Mock groups. Red and blue bars represent 4218 up-regulated and 3817 down-regulated genes, respectively, reflecting the substantial transcriptional differences under both OsGRP3 overexpression and aging treatment. D, Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs between the OsGRP3-Mock vs. Nip-Mock comparison (blue circle) and the Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparison (red circle). The two sets share 404 common DEGs, with 512 unique to the OsGRP3-Mock group and 9,146 unique to the Nip-Aging group. E, Venn diagram showing the overlap of down-regulated DEGs between the OsGRP3-Aging vs. OsGRP3-Mock comparison (blue circle) and the Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparison (red circle). The two sets share 3048 common down-regulated genes, with 770 unique to the OsGRP3 group and 1386 unique to the Nip group, suggesting both conserved and specific aspects in the aging-associated down-regulated genes modulated by OsGRP3. F, Heatmap displaying the expression patterns of alternative splicing events for the 404 common DEGs identified in both the OsGRP3-Mock vs. Nip-Mock and Nip-Aging vs. Nip-Mock comparisons. The color gradient represents expression level differences, visually presenting the consistent expression patterns of these common DEGs under both conditions. G, GO enrichment analysis of the 1386 unique DEGs. Significantly enriched terms are presented from three categories: Molecular Function (GO:MF), Cellular Component (GO:CC), and Biological Process (GO:BP). The x-axis shows the -log10(P), where higher values indicate greater enrichment significance. H, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 1,386 unique DEGs. The x-axis shows the -log10(P). The results reveal significant enrichment in pathways including Galactose metabolism, Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis, and Ribosome, suggesting these pathways may play key roles in OsGRP3-mediated aging regulation.