Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

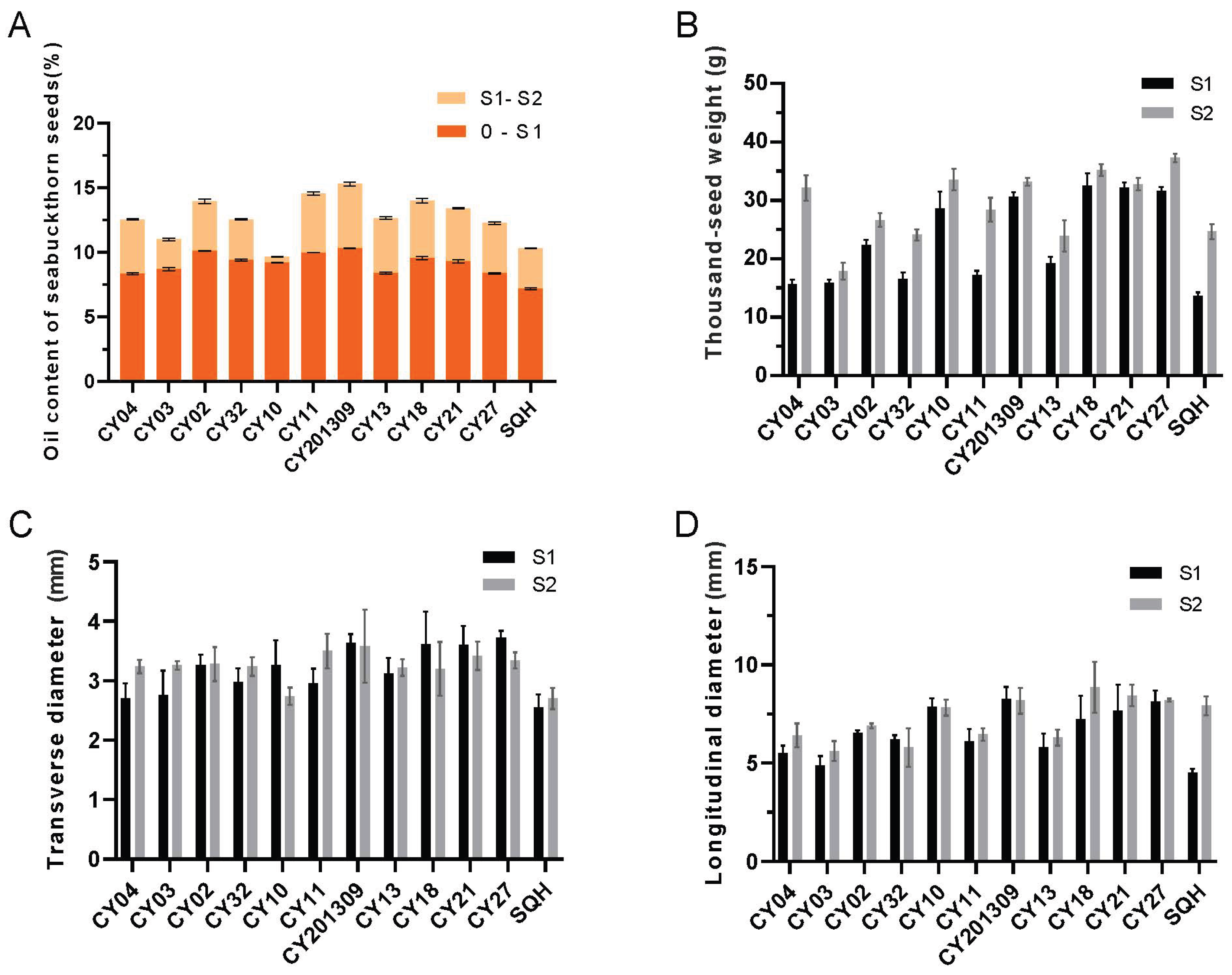

2.1. Seed Traits

2.2. Analysis of UID Transcriptome Data

2.3. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Functional Annotation

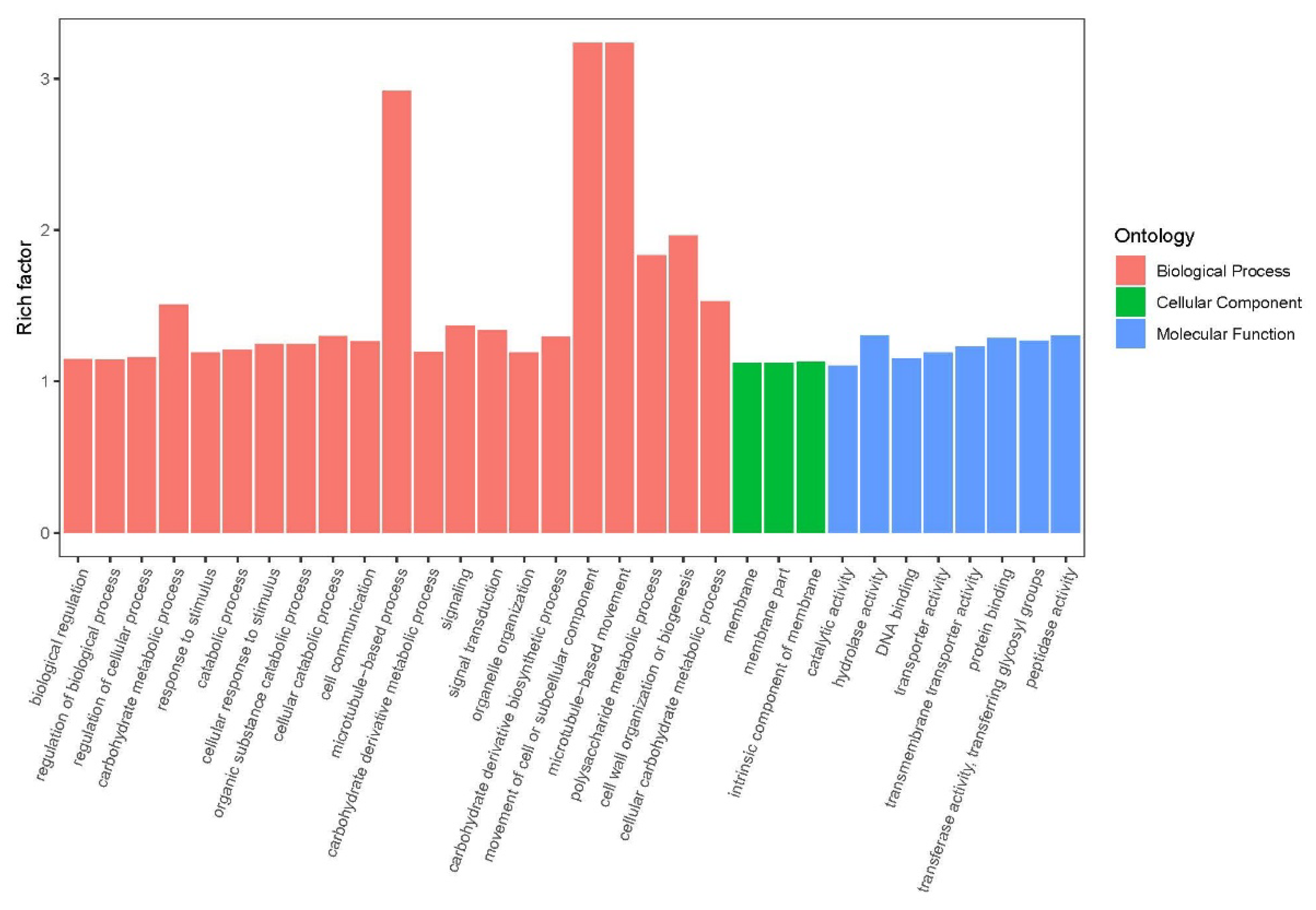

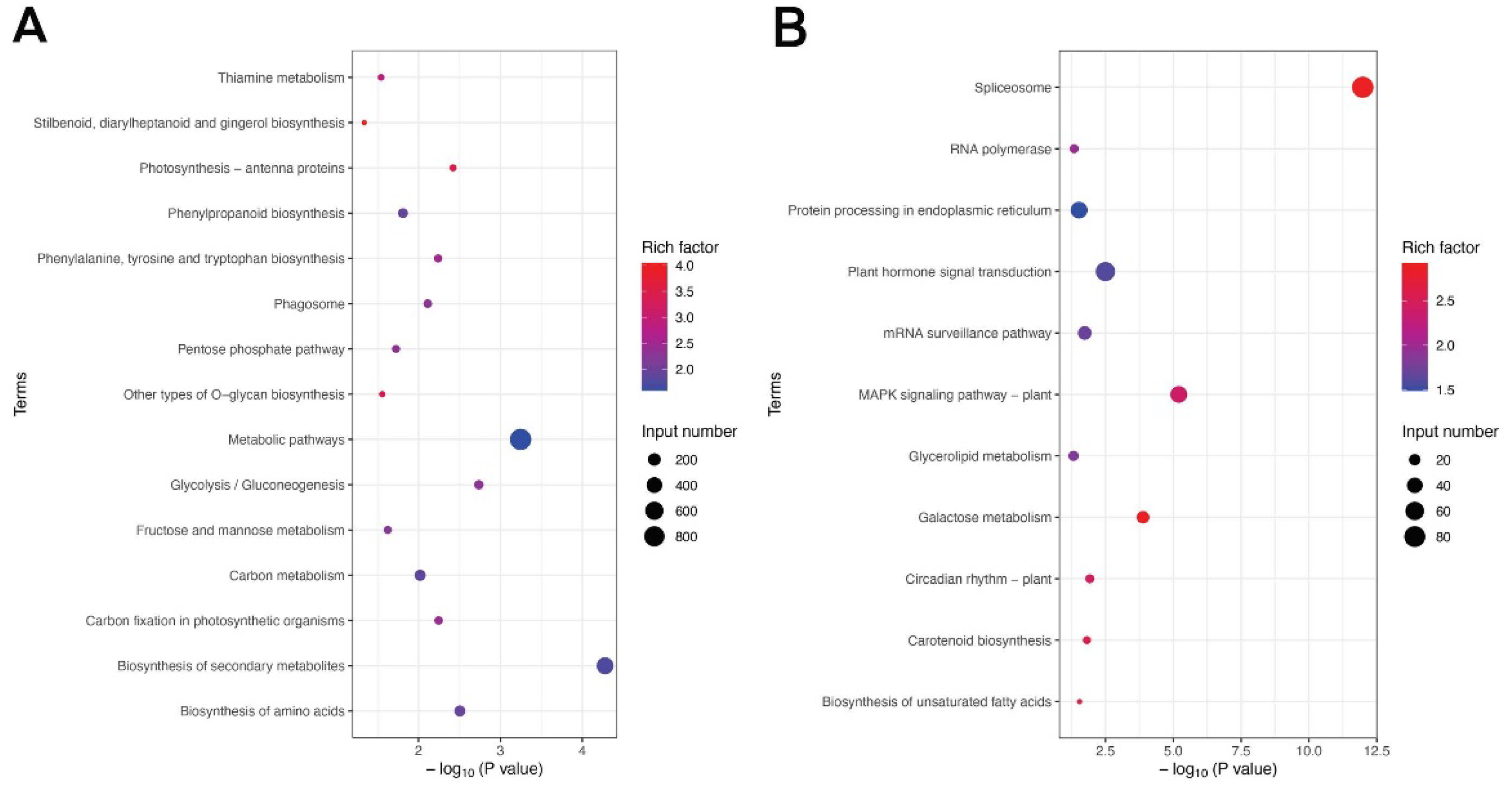

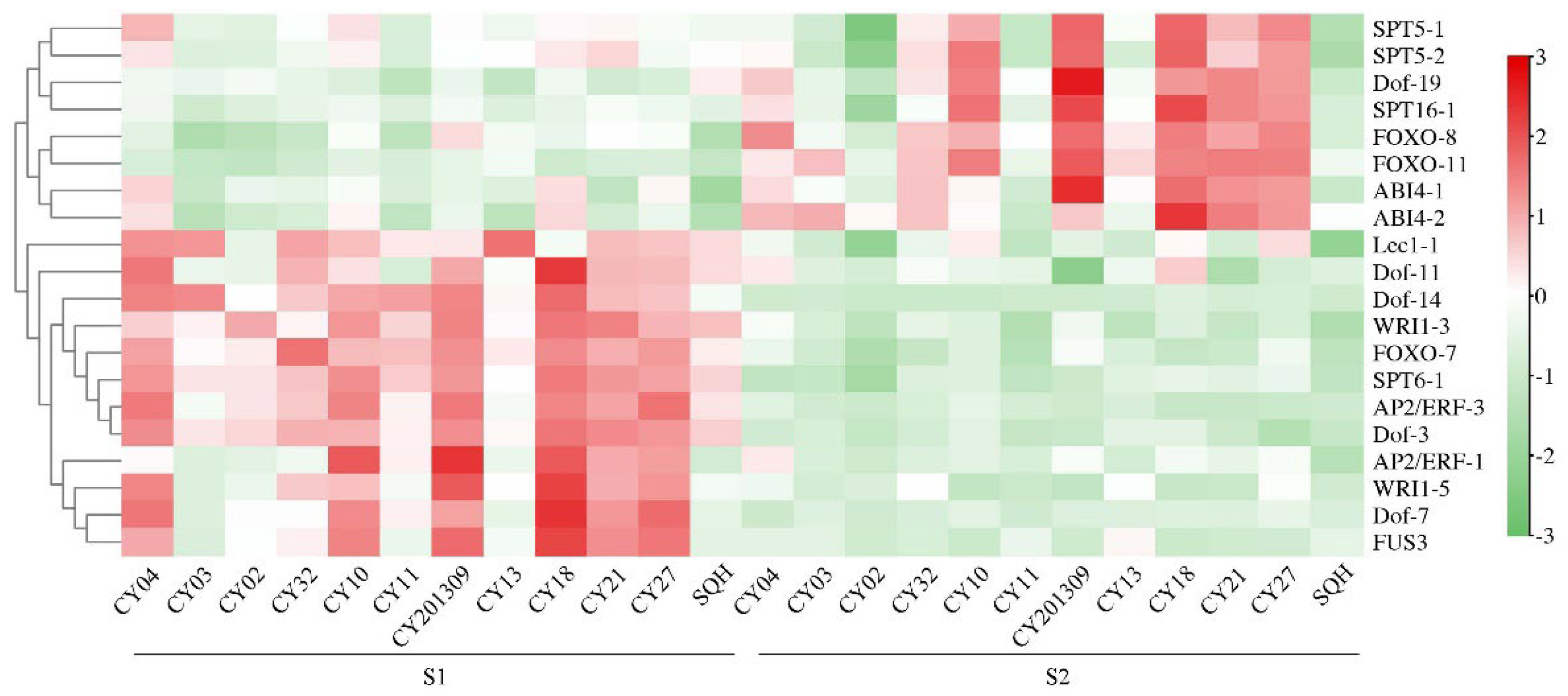

2.4. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Involved in Seed Development

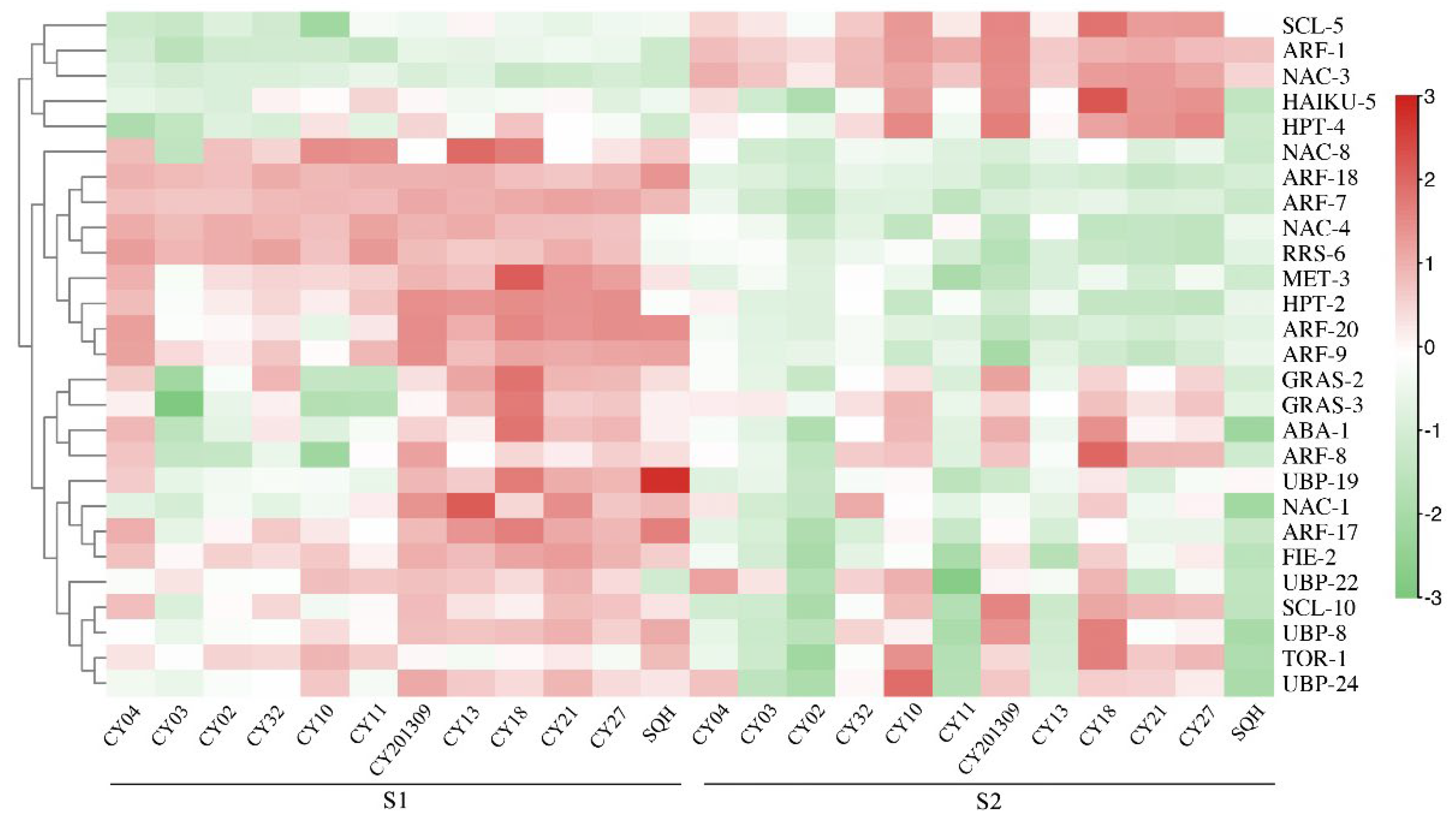

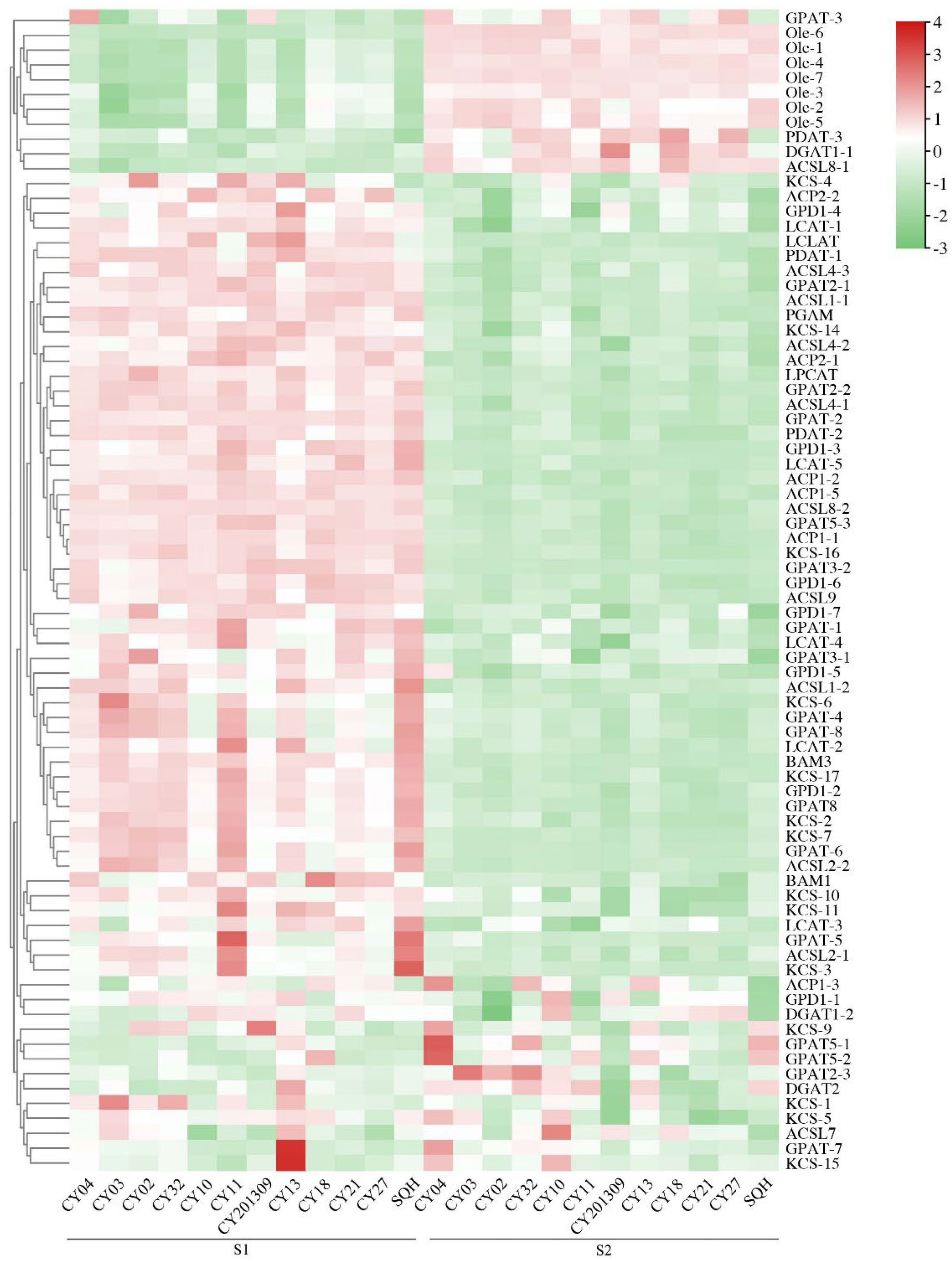

2.5. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Involved in Lipid Biosynthesis

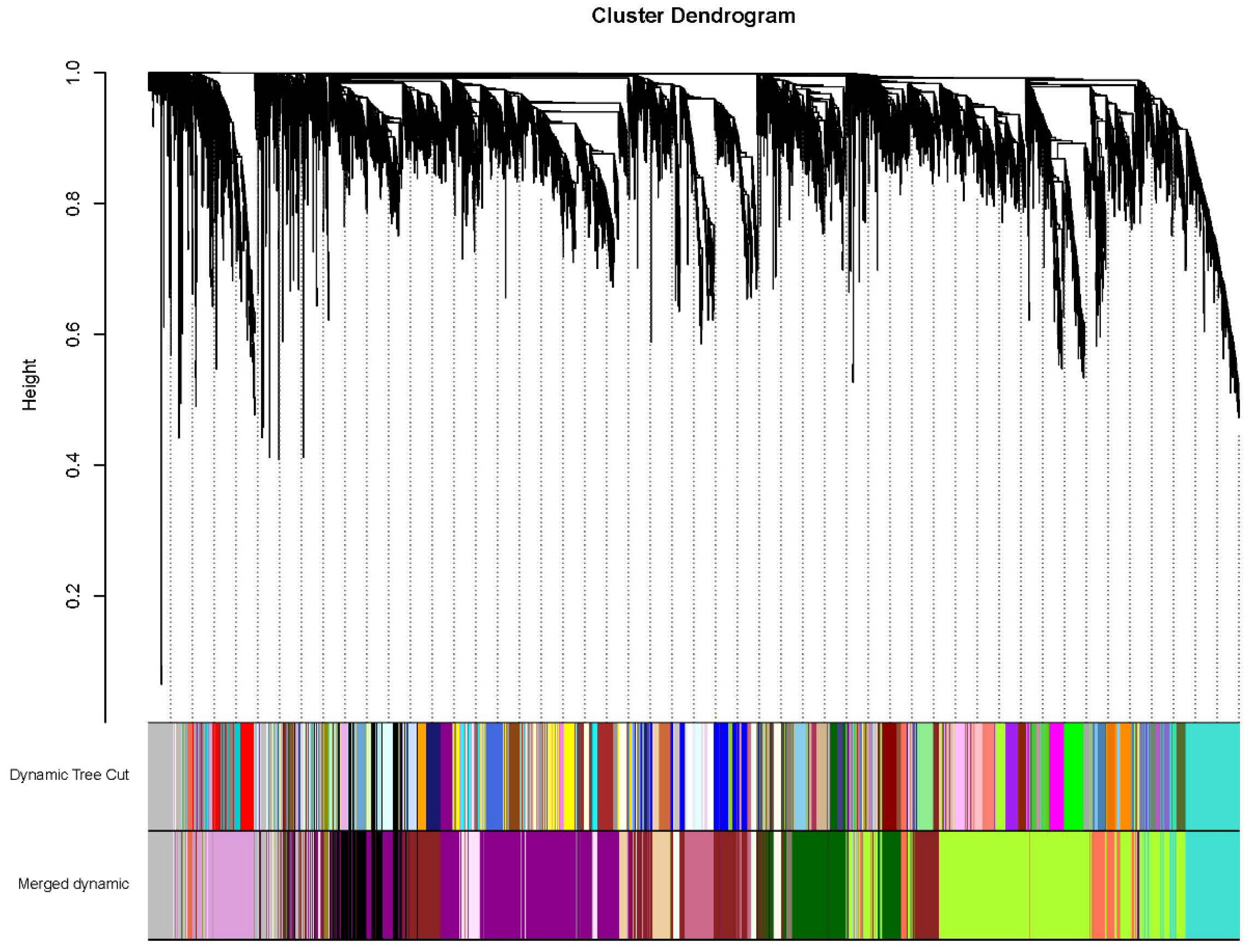

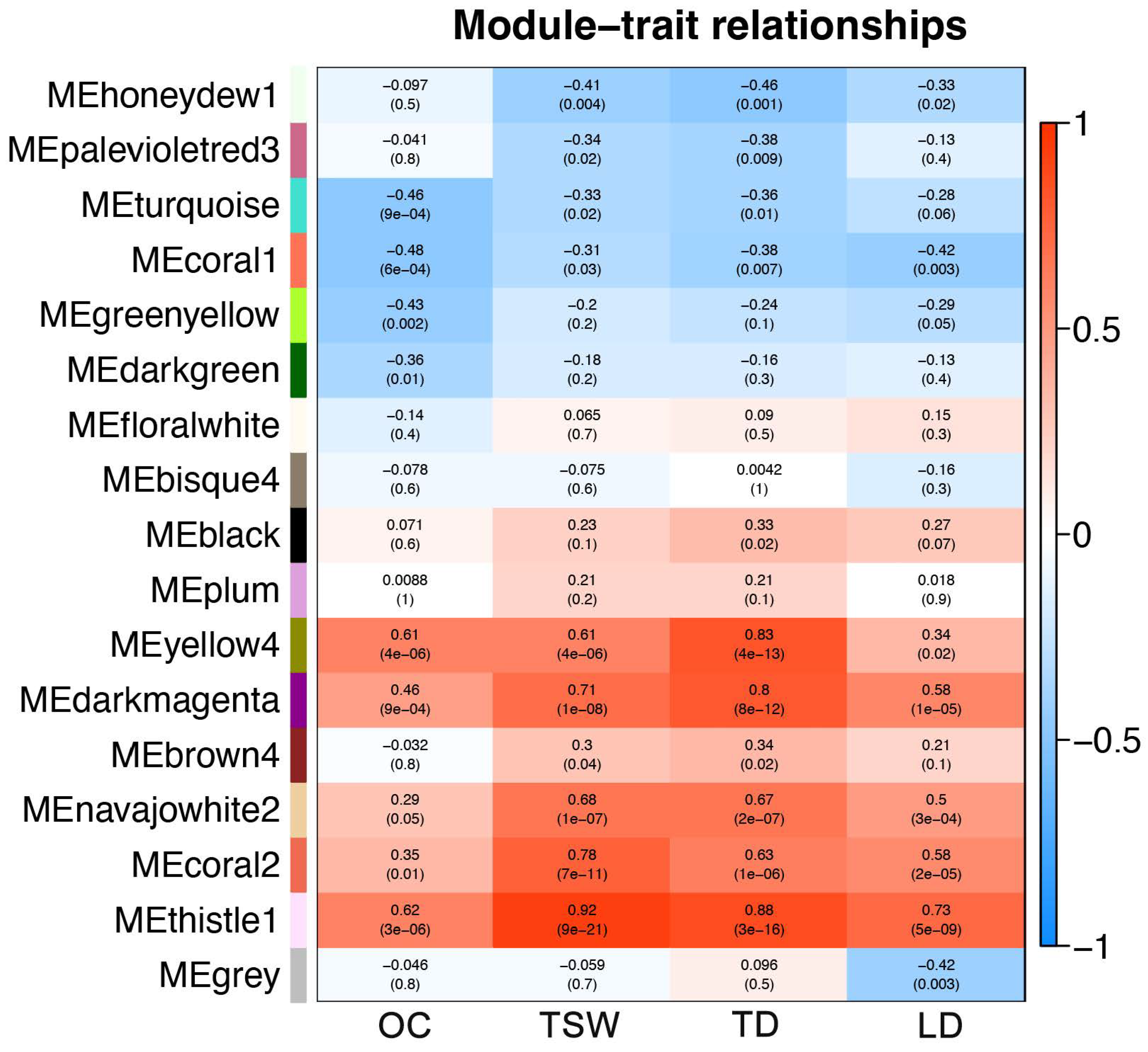

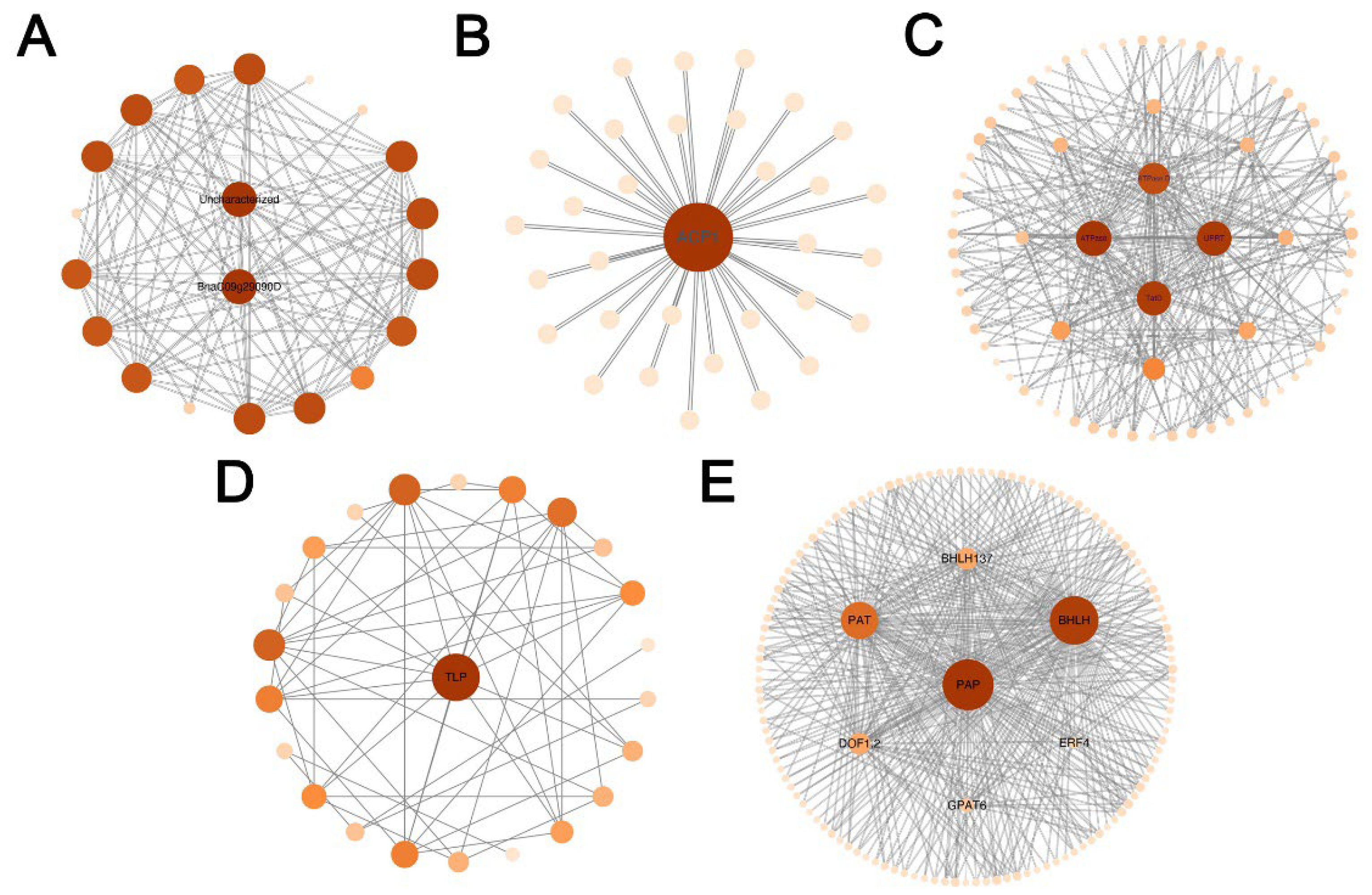

2.6. Co-Expression Network Analysis of DEGs by WGCNA

2.7. qRT-PCR of key DEGs

3. Discussion

3.1. Key Genes Associated with Seed Development

3.2. Key Genes Associated with Lipid Metabolism

3.3. Key Genes Associated with Lipid Metabolism

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Determination of Seed Traits

4.3. Total RNA Extraction, Library Preparation and UID Transcriptome Sequencing

4.4. RNA-seq Data Analysis

4.5. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruan, C.J.; Rumpunen, K.; Nybom, H. Advances in improvement of quality and resistance in a multipurpose crop: sea buckthorn. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2013, 33, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, D.; Ma, X.; Fu, F.; Cao, F. Research Status and Development Prospects of Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) Resources in China. Forests 2023, 14, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Kalimo, K.O.; Tahvonen, R.L.; Mattila, L.M.; Katajisto, J.K.; Kallio, H.P. Effect of dietary supplementation with sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides) seed and pulp oils on the fatty acid composition of skin glycerophospholipids of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Nutr Biochem 2000, 11, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Ruan, C.; Guan, Y.; Li, H.; Du, W.; Lu, S.; Wen, X.; Tang, K.; Chen, Y. Nontargeted metabolomic and multigene expression analyses reveal the mechanism of oil biosynthesis in sea buckthorn berry pulp rich in palmitoleic acid. Food Chem 2022, 374, 131719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ruan, C.; Guan, Y.; Krishna, P. Identification of microRNAs involved in lipid biosynthesis and seed size in developing sea buckthorn seeds using high-throughput sequencing. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 4022–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, S.; et al. Natural allelic variation of GmST05 controlling seed size and quality in soybean. Plant Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Pang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive Element Binding Factor Superfamily Genes in Soybean Seed Development. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 566647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, F.; Xiao, Y.; Kang, X.; Wang, X.; Kuang, R.; Ni, M. Global analysis of canola genes targeted by SHORT HYPOCOTYL UNDER BLUE 1 during endosperm and embryo development. Plant J 2017, 91, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, B.; Xie, G. Overexpressing OsFBN1 enhances plastoglobule formation, reduces grain-filling percent and jasmonate levels under heat stress in rice. Plant Sci 2019, 285, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Tao, J.J.; Cheng, T.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Jiang, Z.H.; Sun, W.C.; et al. Global analysis of seed transcriptomes reveals a novel PLATZ regulator for seed size and weight control in soybean. New Phytol 2023, 240, 2436–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fu, Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Chern, M.; Li, M.; Cheng, M.; Dong, H.; Yuan, Z.; Gui, L.; Yin, J.; et al. The PGS1 basic helix-loop-helix protein regulates Fl3 to impact seed growth and grain yield in cereals. Plant Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, V.S.; Singh, U.S.; Kumar, A. Transcriptional profiling and in silico analysis of Dof transcription factor gene family for understanding their regulation during seed development of rice Oryza sativa L. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38, 2827-2848. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38, 2827–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, P.; Gillet, B.; Römer, S.; Eymery, F.; Massimino, J.; Peltier, G.; Kuntz, M. Over-expression of a pepper plastid lipid-associated protein in tobacco leads to changes in plastid ultrastructure and plant development upon stress. The Plant Journal : For Cell and Molecular Biology 2000, 21, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hua, W.; Hu, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, R.; Deng, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Natural variation in ARF18 gene simultaneously affects seed weight and silique length in polyploid rapeseed. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 5123–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, F.; Luo, J.; Hu, J.; Yu, H.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; Fu, F. Identification of novel natural anti-browning agents based on phenotypic and metabolites differences in potato cultivars. Food Chem 2025, 463, 141450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Qin, H.; Mao, X.; Jiang, H.; Xin, D.; Yin, Z.; Zhu, R.; et al. Meta-analysis and transcriptome profiling reveal hub genes for soybean seed storage composition during seed development. Plant Cell Environ 2018, 41, 2109–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nie, L.; Ma, J.; Zhou, B.; Han, X.; Cheng, J.; Lu, X.; Fan, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y. Transcriptomic Variations and Network Hubs Controlling Seed Size and Weight During Maize Seed Development. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 828923–828936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhou, X.; Huang, L.; Luo, H.; Xie, M.; Liao, B.; et al. Global Transcriptome and Co-Expression Network Analyses Revealed Hub Genes Controlling Seed Size/Weight and/or Oil Content in Peanut. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 3144–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Snyder, C.L.; Schroeder, W.R.; Cram, D.; Datla, R.; Wishart, D.; Weselake, R.J.; Krishna, P. Fatty acid composition of developing sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) berry and the transcriptome of the mature seed. PLoS One 2012, 7, e34099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ruan, C.; Du, W.; Guan, Y. RNA-seq data reveals a coordinated regulation mechanism of multigenes involved in the high accumulation of palmitoleic acid and oil in sea buckthorn berry pulp. Bmc Plant Biol 2019, 19, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Ding, J.; Yu, X.; Li, H.; Ruan, C.J. Identification and expression analysis of critical microRNA-transcription factor regulatory modules related to seed development and oil accumulation in developing seeds. Ind Crop Prod 2019, 137, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Ono, N.; Inoue, S.; Terashima, I.; Kinoshita, T. Overexpression of plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells promotes light-induced stomatal opening and enhances plant growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, S.; Takata, N.; Ando, E.; Toda, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Mitsuda, N.; Nagano, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Kinoshita, T. Overexpression of Plasma Membrane H(+)-ATPase in Guard Cells Enhances Light-Induced Stomatal Opening, Photosynthesis, and Plant Growth in Hybrid Aspen. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 766037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, B. Effect of exogenous calcium on growth, nutrients uptake and plasma membrane H+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase activities in soybean (Glycine max) seedlings under simulated acid rain stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 165, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromas, A.; Paque, S.; Stierlé, V.; Quettier, A.-L.; Muller, P.; Lechner, E.; Genschik, P.; Perrot-Rechenmann, C. Auxin-binding protein 1 is a negative regulator of the SCF(TIR1/AFB) pathway. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Mar Marques-Bueno, M.; Bruce, C.G.; Karnik, R. Unusual Roles of Secretory SNARE SYP132 in Plasma Membrane H(+)-ATPase Traffic and Vegetative Plant Growth. Plant Physiol 2019, 180, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xue, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Schmidt, W.; Shen, R.; Lan, P. Genes of ACYL CARRIER PROTEIN Family Show Different Expression Profiles and Overexpression of ACYL CARRIER PROTEIN 5 Modulates Fatty Acid Composition and Enhances Salt Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.J.; Yu, L.J.; Chen, Q.F.; Wang, F.Z.; Huang, L.; Xia, F.N.; Zhu, T.R.; Wu, J.X.; Yin, J.; Liao, B.; et al. Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP3 participates in plant response to hypoxia by modulating very-long-chain fatty acid metabolism. Plant J 2015, 81, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gully, K.; Berhin, A.; De Bellis, D.; Herrfurth, C.; Feussner, I.; Nawrath, C. The GPAT4/6/8 clade functions in Arabidopsis root suberization nonredundantly with the GPAT5/7 clade required for suberin lamellae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2314570121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.X.; Mao, X.; Zhao, K.; Ji, X.J.; Ji, C.L.; Xue, J.N.; Li, R.Z. Characterisation of phospholipid: diacylglycerol acyltransferases (PDATs) from and their roles in stress responses. Biology Open 2017, 6, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.C.; Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, G.R.; Xing, W.F.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.N. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 6 (GPAT6) is important for tapetum development in Arabidopsis and plays multiple roles in plant fertility. Mol Plant 2012, 5, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.H.; Ren, Z.H.; Lu, C.F. The Phosphatidylcholine Diacylglycerol Cholinephosphotransferase Is Required for Efficient Hydroxy Fatty Acid Accumulation in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2012, 158, 1944–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellaud, S.; Bory, A.; Chabert, V.; Romanens, J.; Chaisse-Leal, L.; Doan, A.V.; Frey, L.; Gust, A.; Fromm, K.M.; Mene-Saffrane, L. WRINKLED1 and ACYL-COA:DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE1 regulate tocochromanol metabolism in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 2018, 217, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.M.; Duncan, R.E. The lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferases (acylglycerophosphate acyltransferases) family: one reaction, five enzymes, many roles. Curr Opin Lipidol 2018, 29, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizouq, M.; Peisker, H.; Gutbrod, K.; Melzer, M.; Hölzl, G.; Dörmann, P. Triacylglycerol and phytyl ester synthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 6216–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Onorato, J.M.; Chen, L.; Nelson, D.W.; Yen, C.-L.E.; Cheng, D. Synthesis of neutral ether lipid monoalkyl-diacylglycerol by lipid acyltransferases. Journal of Lipid Research 2017, 58, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nolan, T.M.; Ye, H.; Zhang, M.; Tong, H.; Xin, P.; Chu, J.; Chu, C.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y. Arabidopsis WRKY46, WRKY54, and WRKY70 Transcription Factors Are Involved in Brassinosteroid-Regulated Plant Growth and Drought Responses. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1425–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, L.; Pelletier, J.M.; Harada, J.J. Central role of the LEAFY COTYLEDON1 transcription factor in seed development. J Integr Plant Biol 2019, 61, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumajo-Cardona, C.; Gabrieli, F.; Anire, J.; Albertini, E.; Ezquer, I.; Colombo, L. Evolutionary studies of the bHLH transcription factors belonging to MBW complex: their role in seed development. Annals of Botany 2023, 132, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, J.; White, J.; Graham, I.; Halliday, K.; Josse, E.M. Shedding light on flower development: phytochrome B regulates gynoecium formation in association with the transcription factor SPATULA. Plant Signal Behav 2011, 6, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, G.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L. PbbHLH137 interacts with PbGIF1 to regulate pear fruit development by promoting cell expansion to increase fruit size. Physiol Plant 2024, 176, e14451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varaud, E.; Brioudes, F.; Szecsi, J.; Leroux, J.; Brown, S.; Perrot-Rechenmann, C.; Bendahmane, M. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 regulates Arabidopsis petal growth by interacting with the bHLH transcription factor BIGPETALp. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.N.; Yin, Y.H. WRKY transcription factors are involved in brassinosteroid signaling and mediate the crosstalk between plant growth and drought tolerance. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2017, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.Y.; Liu, J.X.; Hao, J.N.; Feng, K.; Duan, A.Q.; Yang, Q.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Xiong, A.S. Genomic identification of AP2/ERF transcription factors and functional characterization of two cold resistance-related AP2/ERF genes in celery (Apium graveolens L.). Planta 2019, 250, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.A.; Sun, H.L.; Han, Z.Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Li, Q.Q.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.Z.; Xu, X.F.; et al. ERF4 affects fruit ripening by acting as a JAZ interactor between ethylene and jasmonic acid hormone signaling pathways. Horticultural Plant Journal 2022, 8, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.M.; Xu, C.T.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, M.J.; Yan, N.; Dai, C.B.; Lv, J.; Cui, M.M.; Wang, W.F.; Sun, Y.H. ERF4 interacts with and antagonizes TCP15 in regulating endoreduplication and cell growth in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol 2022, 64, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.T.; Wu, T.R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Pei, T.; Yang, H.H.; Li, J.F.; Xu, X.Y. Genome-Wide Analyses of the Genetic Screening of CH-Type Zinc Finger Transcription Factors and Abiotic and Biotic Stress Responses in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Based on RNA-Seq Data. Frontiers in Genetics 2020, 11, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Deng, X.; Liu, D.; Li, M.; Cui, D.; Hu, Y.; Yan, Y. Genome-wide analysis of wheat DNA-binding with one finger (Dof) transcription factor genes: evolutionary characteristics and diverse abiotic stress responses. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Hou, D.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xie, L.; Ma, Y.; Gao, J. Characterization of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) Dof transcription factors in floral development and abiotic stress responses. Genome 2018, 61, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.A.; Choi, D.; Yeom, S.I. Genome-wide analysis of Dof transcription factors reveals functional characteristics during development and response to biotic stresses in pepper. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 33332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Chen, D.; Kam, J.; Richardson, T.; Drenth, J.; Guo, X.; McIntyre, C.L.; Chai, S.; Rae, A.L.; Xue, G.P. Abiotic stress upregulated TaZFP34 represses the expression of type-B response regulator and SHY2 genes and enhances root to shoot ratio in wheat. Plant Sci 2016, 252, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.; Qin, T.; Zhao, Z. Overexpression of the zinc finger protein gene OsZFP350 improves root development by increasing resistance to abiotic stress in rice. Acta Biochim Pol 2019, 66, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, K.; Lv, M.; Qian, J.; Lian, Y.; Liu, R.; Huo, S.; Rehman, O.U.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Identification and Characterization of the DOF Gene Family in Phoebe bournei and Its Role in Abiotic Stress-Drought, Heat and Light Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 11147–11166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Ma, Q.; Li, D.; Xue, Z.; Chong, K. OsDOG, a gibberellin-induced A20/AN1 zinc-finger protein, negatively regulates gibberellin-mediated cell elongation in rice. J Plant Physiol 2011, 168, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; You, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Small Grain and Dwarf 2, encoding an HD-Zip II family transcription factor, regulates plant development by modulating gibberellin biosynthesis in rice. Plant Sci 2019, 288, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Kallio, H.P. Fatty acid composition of lipids in sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) berries of different origins. J Agric Food Chem 2001, 49, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).