1. Introduction

The bell tower of Murcia Cathedral, erected between 1521 and 1793—spanning nearly two and a half centuries—stands as an unmistakable and defining landmark of both the cathedral and the city of Murcia [

1]. Rising 93 metres in height (98 m including the weather vane at its summit), it is the second tallest bell tower in Spain, surpassed only by Seville’s

Giralda [

2], and long engaged in a historically debated rivalry for that position with the bell tower of Salamanca Cathedral [

3].

Its conception dates back to 1519, as one of the most ambitious undertakings promoted by the cathedral chapter under the direction of Cardinal-Bishop Mateo Lang von Wellenburg. Initially, the Italian architect Francesco Florentino was responsible for the design, but after his early contribution, his brother Jacobo Florentino assumed full direction of the project. It was Jacobo who began the actual construction of this imposing campanile, working on it until his death in 1525.

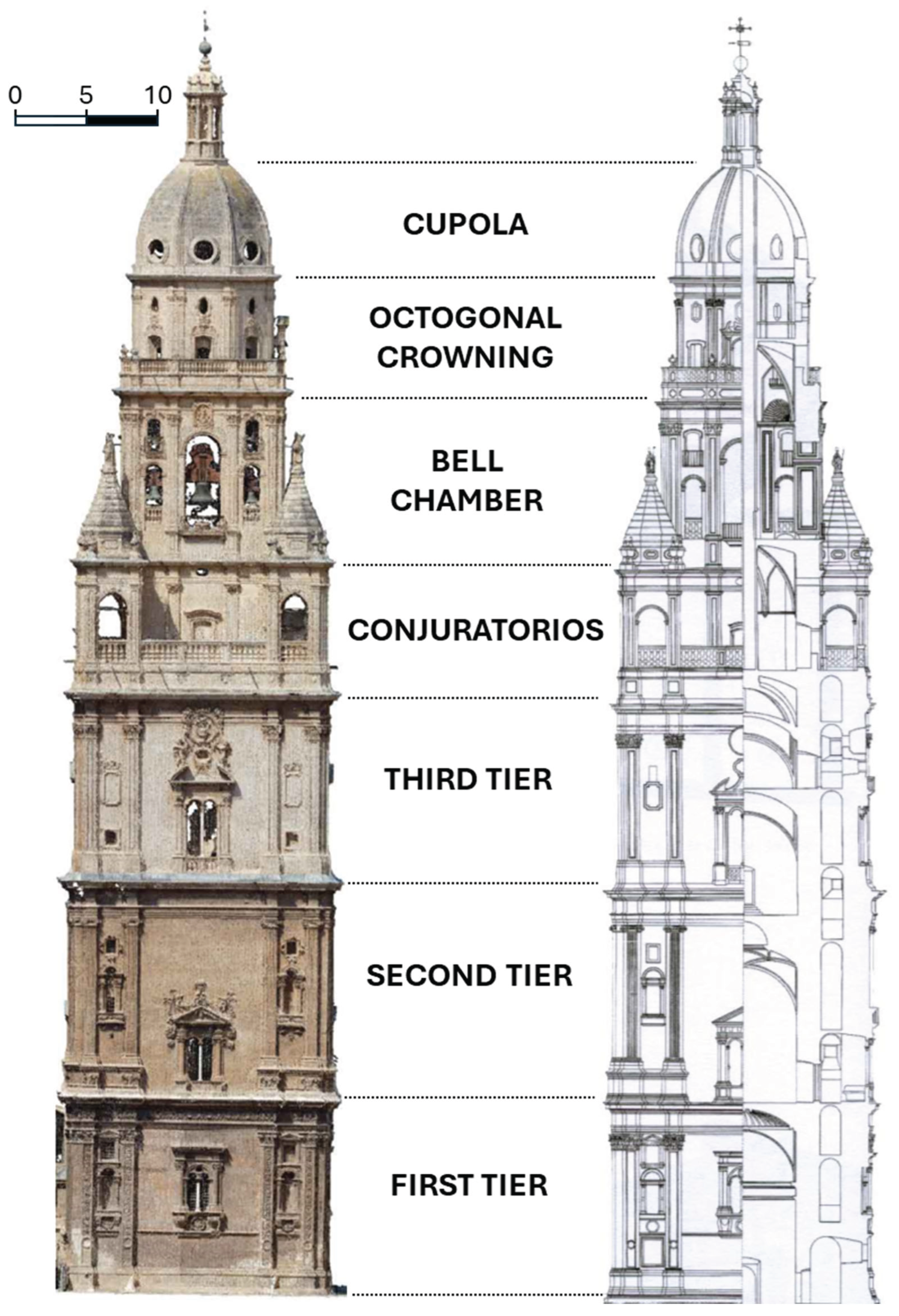

The prolonged building process, which extended for more than two and a half centuries, allowed each stage and architectural tier to incorporate a variety of stylistic influences, mirroring the artistic currents prevailing at different moments in history. As a result, the tower now presents a clear vertical stratification of architectonic languages, organized into distinct and well-defined bodies (

Figure 1).

During such a protracted construction period, the tower experienced problems of inclination, primarily due to the characteristics of the ground upon which it was founded. These issues became particularly apparent during the sixteenth century and were later addressed—though never entirely corrected—during the eighteenth.

The left-hand image shows two adjacent façades with a slight perspective distortion, while on the right the opposite sides have been digitally corrected. The slight real inclination of the tower toward the west, in the direction of

Plaza del Cardenal Belluga, is also evident (

Figure 2).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to provide an integral analysis of the architectural, structural, and geotechnical evolution of the bell tower of Murcia Cathedral (1521–1793), with the purpose of clarifying the physical, historical, and constructive causes that gave rise to its slight inclination and to the differential settlements recorded over the centuries.

To achieve this overall aim, the following specific objectives are established:

To document and interpret the architectural configuration and stylistic evolution of the three principal construction phases of the tower—Renaissance, Late Renaissance, and Baroque—identifying the functional and symbolic logic that guided each stage.

-

To characterize the subsoil beneath the tower, integrating available geological, geotechnical, and hydrogeological data (from IGME maps and piezometric records) in order to assess its bearing capacity, its long-term consolidation behaviour, and its influence on the overall stability of the structure.

To analyse the structural configuration of the tower by applying the classical principles of masonry mechanics (Heyman) and elastic column theory (Euler), adapting these models to the specific case of a double-wall system composed of calcareous ashlar, lime mortar, and rubble infill, to estimate compressive and tensile stresses under current conditions.

To evaluate the historical causes of the observed inclination, by comparing construction records with settlement data and calculated stresses, and by analysing the corrective measures implemented by José López in the eighteenth century to rebalance the structure.

To determine the current state of stability of the tower and its safety margin against crushing, overturning, and foundation failure, taking into account both gravitational loads and seismic actions documented during major historical earthquakes (1755, 1829, and 2011).

To interpret the geotechnical and structural behaviour not only from an engineering standpoint but also from a cultural perspective, understanding the deformation of the tower as an expression of equilibrium between matter and time, between gravity and grace, between technique and history.

3. Architectural Analysis of the Tower

3.1. First Tier

The first tier of the bell tower of Murcia Cathedral was erected on the site that, during the fifteenth century, had been occupied by the Chapel of Saints Simon and Jude. This chapel had been granted to the widow of Jacobo de las Leyes, an episode that underscores the historical connection between the architectural development of the cathedral and the prominent figures of its time. However, in 1519, with the commencement of works under the Florentine brothers, the chapel was demolished and replaced by the Main Sacristy, a space that not only survives to this day but has become a central element of the cathedral complex.

On the north façade of the first tier, an inscription records 19 October 1521 as the date when the first ashlar block of the tower was laid. The selection of the site posed major challenges. The soil, composed of soft clay saturated with water due to the high water table of the sixteenth century, required innovative solutions. To address these difficulties, Francesco and Jacobo Florentino, renowned for their expertise in Renaissance engineering and architecture, took charge of the foundations and the design of the first body. Their approach, grounded in technical rigour, included the use of extraction pumps to remove the accumulated groundwater during the works—a measure that ensured the long-term stability of the tower.

From the exterior (

Figure 3), this first tier presents a square plan and a structure characteristic of the Spanish Renaissance. The

sotabanco—a rebated plinth acting as a foundation—remained concealed until the later urban reforms of the

Plaza de las Cadenas. This element, approximately 2.5

palmos high and 3

palmos wide, integrates seamlessly into the tower’s base, securing its solidity. The Corinthian pilasters adorning the exterior, recessed and ringed, take inspiration from Lombard architecture and are decorated with garlands, grotesques, musical instruments, vases, shields, and fruit motifs, all recurrent elements of Tuscan Renaissance ornamentation.

The frieze of the first tier is unique within architectural history, as it employs lyres as a decorative motif. These lyres—resembling violins without a bridge—reflect the creativity and symbolic refinement of the period. The windows, positioned on three sides of the tower, combine diverse architectural influences: Bramantesque arches, Florentine spatial organisation, and details reminiscent of Michelangelo and Sangallo, such as the hanging corbels supporting the balustrades. The attached columns framing the openings display capitals with inverted volutes and masks, a distinctive feature of Jacobo Florentino’s design language also observed in San Jerónimo in Granada.

Inside, the Main Sacristy houses notable architectural features, including a groin dome, another vault with a cow-horn profile, and a portal designed as a triumphal arch. Probably completed between 1539 and 1540, it contains an elaborate cajonería (set of drawers) made of pine and walnut. This cabinet, begun by Jacobo Florentino in 1523, was completed by Gabriel Pérez de Mena after the fire of 1689, with restoration by Francisco Guil, concluded in 1712.

3.2. Second Tier

The second tier of the tower began construction in the 1540s under the direction of Jerónimo Quijano. This master builder respected the structural layout conceived by the Florentino brothers for the first body, though he introduced greater decorative richness. On the exterior, the Ionic pilasters exhibit a more refined design, with capitals featuring retracted volutes and collarinos, reflecting artistic currents arriving from Florence (

Figure 4). Quijano also made certain adjustments, such as omitting capitals at the corners, since the proposed design did not allow for their proper placement.

The frieze, probably reconstructed in later centuries, departs from Quijano’s characteristic ornamental taste, suggesting that it is not part of the original design. The windows, while similar to those of the first tier, are distinguished by Plateresque candelabra motifs on the jambs and triangular pediments above, establishing a dialogue between Spanish Renaissance refinement and local craftsmanship.

Inside, this second tier served multiple functions over time. Until the nineteenth century, it housed the wardrobe and treasury of the Virgin of La Fuensanta, and also served as a meeting room for the cathedral chapter during floods that made the Chapter Hall inaccessible. Today, it is home to the Archives of the Cathedral Chapter of Cartagena, preserving historic documents such as the petition for the transfer of the bishopric in the time of Alfonso X the Wise. The space is covered by a Renaissance dome with pendentives, attributed to Andrés de Vandelvira, one of the foremost architects of the Spanish Renaissance.

3.3. Third Tier and Crowning

Construction of the third tier of the tower, resumed in the mid-eighteenth century under the direction of José López, marked a decisive milestone in the completion of this monumental structure. This phase not only resolved significant structural challenges but also introduced a stylistic shift toward the Baroque, manifested both in its architectural composition and ornamental detail.

One of the first issues López had to confront was the inclination of the tower toward its northwest face, caused by the differential settlement of the foundations of the two earlier Renaissance tiers. This tilt, accompanied by slight structural sway, threatened the overall stability of the monument. To correct it, López adopted an ingenious technical solution—examined in detail later in this paper—by increasing the thickness of the southeast wall by two feet (approximately 60 cm) and reducing the wall thickness of the third tier by one foot on each side. These carefully calculated modifications effectively stabilised the structure and allowed work to proceed on the upper levels.

From the outside, the third tier is distinguished by its Baroque interpretation, which contrasts with the Renaissance restraint of the lower levels (

Figure 5). This tier introduces a reinterpretation of the Corinthian order, clearly visible in the attached pilasters, whose fluting and volutes exhibit a more dynamic and ornamented design. The corners, in particular, are reinforced by paired pilasters, enhancing the perception of robustness and monumentality throughout the composition.

The ornamentation of this third body follows the formal language of the Cathedral’s Baroque façade. Among its most notable decorative features are mixtilinear profiles, concave–convex mouldings, and fully modelled sculptures, which lend a theatrical and dramatic quality characteristic of the Baroque. This tier also houses the cathedral clock, which transcended its merely functional role to become a symbol of time and civic rhythm for the inhabitants of Murcia and its surrounding region.

Above this level rise the conjuratorios—four rectangular pavilions at the corners—among the tower’s most distinctive features. They were designed to allow priests to perform rituals for the conjuration of storms and other liturgical acts from an elevated vantage point. The conjuratorios, crowned by pyramidal clochetons adorned with decorative bands, stand out for their solemnity and their symbolic role as intersections between the earthly and the divine. At their summits stand sculptures of the Four Saints of Cartagena—Fulgentius, Leander, Isidore, and Florentina—serving as spiritual protectors of the tower and the city.

The next level, the bell chamber, advances a step further into the realm of late Baroque, bordering on French Rococo in refinement. Its decorative lines, more elegant and delicate, are animated by a play of light and shadow produced by the careful articulation of mouldings and ornamental details. This space not only housed the cathedral’s twenty bells but also functioned as a symbolic mediator, connecting celestial rhythms with the temporal cadence of urban life.

Finally, the tower is crowned by the dome designed by Ventura Rodríguez, a synthesis of Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical principles. Its design evokes the structural harmony of Brunelleschi’s Renaissance domes, reinterpreted with eighteenth-century sensibility. The dome incorporates Gothic elements, such as the pointed profile of its upper section, which intensifies the perception of verticality and heightens the monument’s grandeur. Above it rises the small lantern cupola, built with a radial framework designed to bear the weight of the weather vane—an element both functional and emblematic that completes the tower’s ascent.

Inside the third tier, the structure is divided into two principal levels. The first houses the Sala de los Refugiados (Refuge Hall), also known as the Choir Book Archive, covered by a groin dome that demonstrates López’s architectural mastery. This chamber preserved the cathedral’s musical and liturgical records, essential to its ceremonial life. The upper level contains the Clock Mechanism Room, where the bell-ringer once lived, responsible for maintaining both the clock and the bells—devices that governed the rhythm of daily life in Murcia.

The interior of the conjuratorios is centred on the Sala del Lignum Crucis, a chamber devoted to the veneration of the relic of the Holy Cross. From here, priests accessed the terraces to perform the ritual acts. At its centre stands the spiral staircase, a true feat of engineering connecting the lower and upper levels. Rising more than 40 m in height and weighing 116 tons, the staircase is supported by four segmental arches that distribute the loads evenly toward the corners and midpoints of the tower’s façades.

The completion of the tower, with its complex design and symbolic richness, represents not only an architectural achievement but also a collective endeavour reflecting the evolution of styles that define the Cathedral of Murcia. From the Renaissance foundations of the Florentino brothers to the Baroque and Neoclassical refinements of Ventura Rodríguez, each tier of the tower narrates a chapter in the architectural and cultural history of this emblematic monument.

4. Subsoil Analysis Beneath the Tower

This section analyses the subsoil underlying the bell tower of Murcia Cathedral from the combined perspectives of geology, geotechnics, and construction history, with the aim of determining the physical origin of its inclination and assessing whether this deformation stems from the substratum itself. The research integrates data from the National Geological Map Nacional [

4], the Geotechnical Map of Spain [

5,

6], and the Geomechanical and Construction Conditions Map of Murcia [

7], complemented by subsidence records of the urban aquifer [

7].

Murcia Cathedral stands upon the Vega del Segura, a tectonic depression of Neogene origin that during the Miocene was a shallow marine basin and later evolved into a fluvial sedimentation plain. Its geological base belongs to the Neogene basin of the Mar Menor, bounded by the Betic reliefs of Carrascoy and Cresta del Gallo, whose folds—remnants of the Alpine orogeny—frame a structurally unstable yet fertile plain [

4].

The building is founded on a high Quaternary terrace (QT1) composed of silts, sands, and gravels with carbonate crusts, resting on Miocene marls and marly limestones of the Tortonian–Andalusian sequence. These marls, of a yellowish-grey tone, are compact yet plastic; their permeability is low, and their deformation modulus—ranging between 50 and 100 MPa—makes them suitable for uniform loads but vulnerable to differential settlement when combined with fluctuations of the groundwater level.

The surrounding relief, flat and gently sloping toward the river, embodies the paradox of large alluvial plains: their apparent stability conceals the slow mobility of sediments whose plastic response unfolds on geological rather than historical timescales. Upon this nearly horizontal surface, the vertical tower inscribes a tension that is at once structural and metaphysical.

The detailed geotechnical maps [

5,

6,

7] define the lithotechnical succession beneath the cathedral as follows:

Table 1.

Lithotechnical profile beneath the Murcia Cathedral Tower. Data from IGME geological and geotechnical maps [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Table 1.

Lithotechnical profile beneath the Murcia Cathedral Tower. Data from IGME geological and geotechnical maps [

4,

5,

6,

7].

| Unit |

Approximate Thickness |

Composition |

Mechanical Properties |

Allowable Bearing Pressure (qadm)

|

| Urban fill |

1–3 m |

Heterogeneous materials, medium-to-low density (N = 10–30) |

E ≈ 25–50 MPa |

≤122.58 kN/m2

|

| Silty–clayey deposits |

10–15 m |

CL–ML sediments with sandy lenses and fine gravels |

E = 4–12 MPa; compressible |

58.84 kN/m2

|

| Sandy gravels |

>12 m |

Coarse alluvial stratum of ancient riverbed |

E > 50 MPa |

≥196.13 kN/m2

|

The groundwater table remains high, between 2 and 5 m below the surface, and its seasonal oscillation directly influences the consolidation of the silts. The average pressure transmitted by the tower, considering its stone mass and foundation footprint, is estimated between 400 and 600 kPa, locally exceeding the bearing capacity of the silty–clayey layers and generating a long-term consolidation process that explains its gradual inclination.

The original foundation, constructed of massive masonry and lacking piles, was probably seated on the intermediate layers—above the competent gravels—following the sixteenth-century criterion that relied on the soil’s natural compactness. The later history of the tower is, in essence, the history of that confidence: the ground, subjected to constant loads and fluctuating water levels, has responded with almost organic slowness—a movement of less than a millimetre per year, imperceptible on a human scale yet legible on the architectural timescale.

The phenomenon of regional subsidence in Murcia has been precisely documented since the 1990s [

5,

8,

9]. Between 1991 and 1995, the piezometric drop caused by overexploitation of the urban aquifer reached 7–11 m, with a decline of 7.4 m recorded in the vicinity of the cathedral. The consolidation induced by the loss of interstitial pressure produced ground settlements estimated between 15 and 30 cm across the city, only partially recovered after subsequent natural recharge.

In the clays and silts beneath the cathedral, the coefficient of compressibility (mᵥ ≈ 3 × 10−4 m2/kN) and compression index (Cc = 0.2–0.4) indicate that a piezometric fall of 5 m may induce additional settlements of 10–20 mm. Such differential and cumulative deformations are sufficient to alter the equilibrium of a slender structure exceeding 90 metres in height.

From an engineering standpoint, the inclination does not constitute a failure but rather a geological reading of time: the tower records, in its slight deviation, the pulse of the aquifer. Each millimetre of tilt is a trace of hydrology written in stone. In symbolic terms, the subsoil acts as a chronometer of history—the slowness of subsidence transforms the ground into a clock that measures centuries.

Murcia’s urban core lies between isoseismal zones VIII and IX, yet the presence of fine alluvial deposits exerts a seismic damping effect, reducing the effective ground acceleration. The cathedral stands outside the sandy band of the active river channel—an amplification zone—explaining its relatively stable behaviour during historical earthquakes.

Nevertheless, the mild tectonisation associated with the Segura Fault system, combined with differential subsidence, has produced small vertical readjustments that, accumulated over time, affect the tower’s vertical alignment. From the standpoint of material physics, the inclination corresponds to a three-dimensional deformation vector—weight, water, and time as components of a single gravitational equation.

At its deepest level, geotechnics becomes a form of hermeneutics: reading in the earth the signs of the past to foresee its future responses. Beneath the cathedral, the soil is both text and memory. The numerical values—qadm = 58.84 kN/m2, E = 4–12 MPa, Δh = 7 m—are not cold figures but coordinates of a physical history. Each parameter represents a word in the subterranean discourse that architecture translates into form and imbalance.

To understand the causes is to master matter, and matter itself possesses a cultural semantics. The inclination of the Tower of Murcia is not merely the outcome of a consolidation gradient: it is the visible consequence of a hydraulic and agrarian culture that, for centuries, has domesticated the river and pumped its subsurface. The engineer can measure the settlement in millimetres; the historian recognises in that measurement the echo of the civilisation that cultivated the huerta.

Octavio Paz once wrote that “architecture is time turned to stone.” In Murcia, stone has also become the chronicler of liquid time: the water flowing beneath the cathedral dictates—at the pace of centuries—the gentle curvature of its tower.

5. Structural Analysis of the Tower

It may be assumed, as a general principle, that the first tier of any historic masonry tower functions as its structural shaft or sustaining core [

2,

10,

11]. In accordance with the architectural analysis presented in the previous section, the tower of Murcia Cathedral is composed of a double-tube system, consistent with the construction methods employed for masonry towers since antiquity.

Although no excavations have been performed in the lower section of the tower, sufficient indirect evidence allows us to infer that the walls are formed by two parallel ashlar faces with a central core of rubble bound with lime mortar. This interpretation is supported by three main observations:

The use of ashlars of different heights on the inner and outer faces of the walls, which indicates the absence of continuous through-stones or full interlocking between the two leaves.

Documentary evidence showing the systematic acquisition of lime and rubble, particularly under the supervision of Jerónimo Quijano (second tier, 1545–1569), clearly destined for the inner core fills.

The inspection of putlog holes that traverse the north face of the third tier, whose interiors exhibit the rough texture typical of rubble-and-mortar cores rather than the smooth surfaces of ashlar blocks.

Given this configuration, the structural analysis begins from the Euler critical load for a column clamped at its base and free at its top:

where

E is the elastic modulus of the material and

I the moment of inertia of the cross-section along the weak axis. Both magnitudes must be corrected to account for the heterogeneous and anisotropic composition of a wall formed by two ashlar leaves and an intermediate lime–rubble core.

To obtain an updated value of the equivalent elastic modulus, it must be considered that the material behaves as a composite system: ashlars and mortar joints act as materials in series, while the wall layers act in parallel. Thus, for elements in series, the modulus is:

and for elements in parallel:

Combining both gives the equivalent elastic modulus:

where:

e1: height of the ashlar blocks in the outer leaves

e2: height of the mortar joints

E1: elastic modulus of the limestone masonry

E2: elastic modulus of the lime mortar (considered equivalent to that of the internal rubble fill)

l1: combined thickness of both ashlar leaves

l3: thickness of the central lime–rubble core

The moment of inertia of the wall may be obtained as the sum of the three layers composed of two distinct materials:

for each unit length, later applied to both concentric tubes.

When these relationships are applied, it becomes clear that, despite the tower’s 93 m height, the critical stress remains below the working stress, confirming the overall stability of the masonry shell.

The vaults of broken webs represent, from an elastic standpoint, highly complex structures composed of multiple small vaults of simple geometry joined along ribs of varying curvature. Because these junction lines present discontinuities in the field of isostatic functions, Renaissance architects intuitively strengthened the folds by filling the extrados with regularising lime mortars, effectively homogenising their mechanical behaviour.

Determining the reactions at supports or the stresses within the web of such vaults is often complex, since many parameters—section geometry, materials, fill densities, elastic coefficients, and isotropy—remain unknowns rather than fixed values. In addition, these vaults frequently interact with other superimposed vaulted structures, further complicating the system of internal reactions.

No destructive testing has ever been conducted to determine the compressive strength of the tower’s limestone or other construction materials [

12]. Attempts were made [

13], but the ethical imperative of preserving the monument’s integrity prevailed over the desire for direct measurement. Consequently, the present study relied on non-destructive testing, specifically rebound hammer (Schmidt hammer) measurements, to estimate the compressive stress magnitudes (

Figure 6).

The procedure, while not perfectly precise, was deemed reliable, as the expected statistical dispersion rendered further complexity unnecessary. Only if the material had shown signs of operating near its mechanical limits—which was not the case—would more sophisticated techniques have been required. This study continues a series of previous sclerometric analyses performed on the same limestone [

12,

14]. As in earlier campaigns, the results indicate that the weathered limestone exhibits strengths roughly five times lower than the unaltered rock (

Figure 7). However, these alterations affect only superficial layers, averaging less than 1 cm in depth [

12,

15], and thus do not compromise the overall mechanical integrity of the masonry.

The tower is a masonry construction, and as such, it adheres to Heyman’s three fundamental principles for masonry structures [

16]: their stability depends on their self-weight, the material cannot resist tension, and thrust lines must remain within the masonry envelope. Owing to this behaviour, the internal portions of the walls can reach higher compressive capacities than those calculated from nominal stresses alone. This is due to the triaxial compression effect produced by the confinement of the masonry mass, which restricts transverse expansion.

In this case, the elastic modulus

E may be replaced by the adjusted value

E′, according to:

where

ν is Poisson’s ratio, which for sound material may be taken as 0.20. Based on the studies consulted [

12,

17] and the results of the Schmidt hammer tests, the mean elastic modulus of the healthy limestone is approximately

E = 19,613 N/mm

2. Consequently, the average compressive strength is:

Although Heyman’s principles acknowledge the inability of masonry to withstand tension [

16], a theoretical tensile strength equivalent to 1/15 of the compressive strength may be adopted for comparative purposes:

Hence, for sound material, the maximum working stress in the lower tier of the tower is:

This confirms the absence of crushing risk in the most compressed courses.

At the corner stones, where no lateral confinement occurs, the transverse strain is:

which corresponds to a tensile stress of:

—well below the theoretical tensile limit (0.52 N/mm

2).

The tower has demonstrated stability during major earthquakes, including the 1755 Lisbon event, whose effects reached Murcia [18,19], the 1829 Torrevieja earthquake [20], and the 2011 Lorca earthquake [21]. Occasional transient stress increases, possibly up to threefold, may explain the presence of minor vertical cracks observed on the lower north corners (

Figure 7), though these remain localised and non-structural.

As discussed earlier, the tower was built with two concentric tubes of thick masonry walls, employing the double-leaf technique with lime–rubble infills. Both were bonded at the corners through the interlocking spiral continuation of the inner shaft, where semicircular arches open to accommodate the ramp passages.

The outer shell carries only its self-weight and that of the ramp vaults, corresponding to the construction up to the balustrade above the third tier (

Figure 5). The working stress on the lower ashlars of the outer shell is 0.74 N/mm

2 (735.50 kN/m

2).

The inner shaft, about one-fifth thinner than the outer one (

Figure 1), bears a significantly higher load, receiving the weight of four internal domes and the entire bell chamber that rises from the third tier to the lantern. Here, the working stress reaches 1.02 N/mm

2 (1,019.89 kN/m

2).

Consequently, the elastic deformations are noticeably greater in the outer walls than in the inner shaft. The absolute vertical deformation of the outer wall is approximately:

while that of the inner shaft is:

The ingenious decision to separate the two structural tubes effectively prevented significant secondary stresses at their points of connection.

Finally, the helical staircase constitutes an independent load-bearing system. Measuring over 40 m in height and weighing 1,135 kN, it transmits its load to the central axis of the tower through two vaults forming the floor and ceiling of the first bell chamber.

The lower vault, though hidden between the floors, is the most structurally interesting. The cylindrical perimeter of the staircase and its core rest upon a stone ring, which itself forms the keystone of four powerful segmental arches—two spanning diagonally to the corners and two to the centres of the faces.

Assuming that the loads on each vault are evenly distributed and that the arches receive weights proportional to the fourth power of their spans, the diagonal arches each bear approximately 165 kN, while the axial arches carry about 115 kN.

This equilibrium of thrusts and counter-thrusts, subtly orchestrated in stone, confirms that the tower’s geometry is not merely aesthetic but profoundly structural—an embodiment of equilibrium between gravity and form.

6. Settlement of the Tower

When José López resumed construction of the tower in the mid-eighteenth century, he found that the two existing Renaissance tiers had suffered significant differential settlement [

14], accompanied by an overall tilt toward the eastern face [

1,22].

To compensate for the greater settlement that had occurred on the east side, López increased the thickness of the shaft on the opposite (west) side by two feet (≈55.8 cm), while simultaneously reducing the outer dimension of the third tier by one Parisian foot on each face. This eccentric loading generated a working stress, due solely to the induced moment, of approximately 10 N/cm

2, an excessive value for the bearing capacity of the subsoil [

5].

For this reason, when López proceeded with the construction of the bell-tower stages, he made a further correction, shifting the continuation of the inner shaft in the opposite direction. This followed what was known as the trial-and-error method, consisting of successive adjustments aimed at preventing greater deflections on the east face by counterbalancing them with smaller compensatory deformations on the west.

It must be understood that the construction of the tower was exceptionally complex. The original design implied a self-weight exceeding 195,000 kN. In other words, the ground—without any auxiliary device—would have been required to work at stresses greater than 50 N/cm2. For this reason, the cathedral chapter engaged Francesco Torni da Firenze, an Italian architect renowned for his experience in difficult foundation works [23,24,25,26].

As Francesco di Giorgio Martini himself wrote:

I campanili deno essere in prima ben fondati. E se fondo non si trovasse, sopra pali e banconi [si debbe] fondare. Dia essere il fondo al meno piè quindici sopra [debería decir, infra] delle terra, e di poi seguire le mura con debita grosezza. E gli spazi dell’altezza dall’uno sfinestrato all’altro piè vinti, più o manco sicondo la qualità d’esso, con le volte sicondo richiede. E gli ultimi sfinestrati le spazi più larghi dove le campane vanno, acciò che le voci occupate non sieno, et al.la superficie l’ultima volta con corridoio e parapetto intorno, e in esso la cimasa pirami dale o altra forma cor ornate scolture son da fare… E possasi fare ditti campanili di più varie forme: tondi, facciati, quadrati e graduati con bellissimi ornamenti di ricinte cornici, membri, colonne, tabernacoli e altre scolture sicondo la degnità de tempi [27].

This description closely coincides with the evidence recorded in Murcia and once again confirms that the entire construction process followed, to a great extent, the assumptions of the original design model.

The need to execute large footing slabs above areas likely supported by wooden piles required the excavation of deep trenches to receive them. Today, the groundwater level lies at approximately –3.60 m. Considering that the subsoil consists mainly of saturated silts, it is easy to understand the necessity of installing sheet piling during excavation—both beneath the tower foundations and in several supporting elements of the Gothic structure of the cathedral itself.

The critical height for cohesive soils, derived from the condition of null active Rankine pressure, is expressed as:

For the soil surrounding the Cathedral of Murcia [

5,28], this yields:

a magnitude roughly half the depth of the foundation trenches, thus demonstrating the necessity of such well-braced sheet piles.

The geotechnical tests carried out beneath the tower’s foundation did not detect any wooden piles. However, this negative result does not preclude their existence. The objective of the seven boreholes performed [29] was not to locate piles, but to determine the dimensions and material composition of the footing, as well as the mechanical characteristics of the subsoil.

Four boreholes were made outside the footing, seeking its edge, while three intersected its periphery; statistically, the probability of encountering a pile in these positions was extremely low—estimated at ≤0.02 [

14].

From the geotechnical tests conducted by Ceico [

14,28,29], the following parameters were obtained:

Cohesion: c = 29.42 kN/m3

Internal friction angle: φ = 10°

Dry unit weight: γ = 16.18 kN/m3

Soil type: soft clay up to 12 m depth; gravels and sands below that horizon

Groundwater level: n’ = −3.80 m relative to current grade; n = −4.10 m relative to the reference level (±0.00) at the step of the Portada de la Cruz, north façade

Foundation dimensions: a × b = 19.64 × 19.64 m

Mean footing thickness: z = 4.70 m

Average depth of foundation base: p’ = −5.60 m from pavement; p = −5.90 m from reference level

Material composition: lime mortar and limestone rubble conglomerate

From the geometric survey of the tower, the following gravitational loads were deduced:

Self-weight of the tower: P = 165,000 kN ±10%

Weight of the foundation: Q = 35,000 kN ±5%

Total load:

As mentioned previously, during the mid-sixteenth century the tower experienced eastward displacement during construction, which led to the suspension of works after completion of the second Renaissance tier.

Two centuries later, once the differential settlements had stabilised, José López resumed the works, slightly reducing the projected height and introducing adjustments to re-centre the loads and compensate for the earlier tilt [22].

The historical record of differential settlements is complex: along with the uniform settlement of the footing, there were uneven edge deformations caused primarily by two factors [

8,

9,

14,28,29]:

Higher lateral friction on the eastern side of the large square footing adjacent to the temple, where precompressed soils produced greater active thrust than on the opposite faces.

Successive adjustments by José López in the centre of gravity of the loads, first shifting it from east to west and later partially reversing it—by thickening the western wall of the third tier, then extending the bell chamber toward the east, enlarging the terrace on the western side.

These compensations are visible today from the north façade or the southwest corner (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), where the loss of vertical alignment and the successive corrections made during construction can clearly be observed in the slightly curved profile of the tower’s elevation.

Each corner of the tower exhibits two settlement components:

one due to uniform subsidence of the footing,

and another, differential, produced by the non-uniform deformation of its edges.

The uniform settlement of the footing is estimated at ≈32 cm, based on:

(a) the deformation observed in the most stable cornices (the uneven eaves of the ante-sacristy), and

(b) the level difference between the current cathedral pavement and the sacristy floor.

The additional settlement induced by the new eighteenth-century loads is evident in the misalignment of the wall containing the current tower door, measured at approximately 11 cm in the southeast corner.

Therefore, during the first phase—up to completion of the second tier (ca. 1520–1760)—the tower experienced a uniform settlement of about 20 cm; after the Baroque additions, this increased by another 12 cm, reaching the 32 cm now observed.

Superimposed upon this are corner-specific deformations, corresponding to the direction of local tilting. Despite the slow and progressive loading over its 275-year construction, the structure exhibits an anomalous but non-critical pattern of load transfer to the subsoil.

Assuming the absence of piles, the ultimate bearing capacity may be estimated using the Terzaghi–Brinch Hansen formulation for square foundations:

The allowable working stress should not exceed:

although a prudent criterion suggests ≤ 80 kN/m

2.

Accordingly, the maximum allowable load on the foundation base is:

Considering lateral friction on the four vertical faces, the active thrust is:

Assuming a Dörr coefficient suitable for silty soils (

f ≈ 0.10) and a perimeter area of

the lateral friction contribution is:

Hence, the total maximum load without piles is:

which is less than the tower’s total load:

This situation does not imply collapse, which would occur only for a virtual self-weight exceeding:

Thus, in the absence of piles, the safety factor against bearing failure would be:

Given the tower’s proven seismic stability during major earthquakes [18,19,20,21], it is highly plausible that the foundation rests on a grid of wooden piles about 6 m deep, driven into the gravel strata.

Since its foundation in 1519, the tower has experienced relative differential settlements, the northeast corner (

Figure 9, right) currently standing 56 cm lower than the northwest—distinct from the uniform settlement of the footing.

These issues were already evident in the sixteenth century, prompting Jerónimo Quijano to halt construction midway through the second tier (at 28.80 m), less than one-third of the total height. When works resumed in the eighteenth century, Juan de Gea and José López, following a public design competition, proposed an eccentric load redistribution to counteract the eastern settlement by overloading the western side.

This was achieved by thickening the outer western wall by two feet, introducing an eccentric overload of 18,632.64 kN and a bending moment of approximately 137,295 m·kN. Considering the section modulus of the tower’s plan (W = 1,300 m3), the edge stresses from this moment reach 0.1079 N/mm2 (≈108 kN/m2)—about 30% of the unit ground reaction produced by the weight of the three lower tiers alone.

Consequently, the western wall carried a stress of

a considerable magnitude that explains the maximum relative settlement observed at the northwest corner (

Figure 8).

When the upper tiers were subsequently built—with a single-wall structure—the geometry was once again offset in the opposite direction, mitigating the local settlement that had developed on the western side.

The tower’s total weight, including its foundation of 4.70 m average thickness, exceeds 200,000 kN (±10%), yielding average working stresses of about 332 kN/m2, even after discounting lateral friction. This value approaches the theoretical bearing capacity (521 kN/m2) predicted by Prandtl’s formula, suggesting that the tower was likely founded on a network of pine piles, as described by Renaissance treatises, still used in the cathedral’s later Baroque additions—particularly the main façade—at a rate of 3–5 piles per square metre.

It would therefore be advisable to perform inclined core drillings to confirm the presence or absence of this pile foundation system—not merely for theoretical knowledge, but to verify the long-term stability of the tower. A key concern is whether these wooden piles, after almost five centuries under heavy load, remain structurally sound.

Due to urban growth, the disappearance of irrigation channels, and the canalisation of the Segura River, the groundwater level is gradually dropping [

9]. It would thus be prudent to install buried piezometric sensors to monitor medium- and long-term variations in soil moisture—not only to detect potential clay shrinkage, but also to evaluate the risk of xylophagous decay in the pile heads, which have long been protected by the impermeable saturation of the surrounding clays.

7. Conclusions

The construction process of the tower reveals a rich synthesis of architectural styles that evolved over the course of nearly three centuries.

The first tier, begun in 1521 by the Italian brothers Francesco and Jacobo Florentino, displays a square plan and a distinct Renaissance character, enriched with Hispanic Plateresque ornamentation. Its interior houses the Main Sacristy, one of the cathedral’s most emblematic spaces.

The second tier, designed by Jerónimo Quijano, retains the Renaissance language, though in a purer and more disciplined form. Construction of this level was completed in 1555, after which the work was halted for over two centuries due to a growing inclination that began to affect the tower’s stability. The Cathedral Archives were later placed within this tier—at a height chosen deliberately to protect them from the frequent floods of the Segura River.

The third tier, erected in 1765 under José López, belongs fully to the Baroque period. López applied an ingenious architectural compensation strategy to counteract the pre-existing tilt, redistributing the load toward the opposite side. This tier contains the clock room, while above it rise the four conjuratorios—small temple-like pavilions capped by pyramidal domes and surmounted by the statues of Saints Fulgentius, Leander, Isidore, and Florentina. These spaces were used for the ritual conjuration of storms, performed with the relic of the Lignum Crucis still preserved in the cathedral.

Finally, before the crowning element, stands the bell chamber, which houses the cathedral’s twenty bells, most of them dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—today among the building’s most iconic features. The composition is crowned by an elegant dome designed by Ventura Rodríguez, of Neoclassical inspiration, completed in 1793 with the addition of the lantern.

The inclination of the tower originates in the geological nature of the ground upon which it stands:

The subsoil belongs to the alluvial plain of the Segura River, composed of artificial fills and compressible silts up to 15 m thick, resting on competent gravels.

The geotechnical properties indicate low bearing capacity (≤58.84 kN/m2), high groundwater table, and the presence of subsidence induced by piezometric fluctuations.

The differential settlement and observed inclination result jointly from the compressibility of the subsoil, minor tectonic activity, and centuries of progressive clay consolidation.

The seismic behaviour of the tower is mitigated by the soft alluvial deposits, which act as a dynamic cushion damping external vibrations.

Ultimately, the inclination of the Tower of Murcia embodies a lesson in equilibrium—a dialogue between gravity and grace, between rational calculation and the patience of matter.

Engineering expresses this dialogue through equations; architecture embodies it in form; and together they testify that calculation is not alien to culture, but one of its most profound expressions—the will to measure in order to understand, to weigh in order to elevate.

The soft, clayey soil combined with a high water table during the sixteenth century produced differential settlements in the foundations, resulting in a slight tilt toward the northwest face of the tower. The problem became apparent during the construction of the second tier and was later addressed in the eighteenth century by José López, who designed an architectural counterweight system by increasing the wall thickness on the southeast side and reducing that of the opposite walls, thus compensating the pre-existing lean. These adjustments allowed construction to continue safely until the tower’s completion in 1793.

Although these eighteenth-century interventions stabilised the structure, modern studies confirm that the tower retains a slight inclination—a condition both common and instructive among historic buildings erected upon the mutable soils of alluvial plains.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- García, E.M. La torre de la Catedral de Murcia. Representaciones en pintura y fotografía. Imafronte 2024, 31, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, R.R. Structural Analysis of ‘La Giralda’, Bell Tower of the Seville Cathedral. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, M.P. La Torre de las Campanas de la Catedral de Salamanca. 1988. Available Online: http://usal.worldcat.org/title/torre-de-las-campanas-de-la-catedral-de-salamanca/oclc/47644005&referer=brief_results.

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Mapa geológico de España, escala 1:50.000 (Hoja 934—Murcia). Mapa Geológico de España. Available Online: https://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/geologica/Magna50Hoja.aspx?Id=934&language=es.

- M. de I. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Dirección General de Minas, Mapa Geotécnico General. Murcia. Hoja 7-10/79. 1977.

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Mapa Geotécnico General de España, Escala 1:200.000 (Hoja 79—Murcia). Mapa Geotécnico General de España. Available Online: https://info.igme.es/catalogo/resource.aspx?portal=1&catalog=3&ctt=1&resource=7979&lang=spa&dlang=eng&llt=dropdown&q=puntos de agua&master=infoigme&shpu=true&shcd=true&shrd=true&shpd=true&shli=true&shuf=true&shto=true&shke=true&shla=true&shgc=true&shdi=true.

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Mapa Geotécnico y de Riesgos Geológicos 25k y 5k—Mapa de la Ciudad de Murcia. Mapa Geotécnico y de Riesgos Geológicos. Available Online: https://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/tematica/Geotecnico25Mapa.aspx?Id=Murcia&language=es.

- Carretero, N.J.V.; de Justo Alpanés, J.L. La Subsidencia en Murcia: Implicaciones y Consecuencias en la Edificación. 2002. Available Online: https://www.carm.es/web/pagina?IDCONTENIDO=9795&IDTIPO=246&RASTRO=c2255$m36284,36305.

- de Justo Alpañés, J.L.; Carretero, N.J.V.; de Justo Moscardó, E. Subsidencia en suelos saturados y parcialmente saturados. Aplicación al caso de Murcia. Rev. Digit. Cedex 2003, 132, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde, R.R. Analysis of the Tower of Hercules, the World’s Oldest Extant Lighthouse. Buildings 2023, 13, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, A.J.M.-G. Mecánica de las estructuras antiguas. O cuando las estructuras no se calculaban. 2011.

- Botí, A.V. La piedra caliza de la catedral de Murcia. Loggia Arquit Restauración 1997, 2, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.C.; Alonso Rodríguez, M.Á.; Díaz, E.R.; López Mozo, A. Cantería Renacentista en la Catedral de Murcia. 2005. Available Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10317/1644.

- Vera Botí, A. La Torre de la Catedral de Murcia: De la teoría a los resultados. Murgetana 1993, 87, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, C.M.; Esbert, R.M.; Díaz-Pache, F.; Alonso, F.J. Soiling of building stones in urban environments. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, J. The stone skeleton. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1966, 2, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbert, R.M.; Grossi, C.M.; Valdeón, L.; Ordaz, J.; Alonso, F.J.; Marcos, R.M. Estudios de laboratorio sobre la conservación de la piedra de la Catedral de Murcia = Laboratory studies for stone conservation at the Cathedral of Murcia. Mater. Construcción 1990, 40, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).