1. Introduction

The Cathedral of Santa Maria of Girona, located in the northeastern region of Catalonia, Spain, represents one of the boldest and most structurally ambitious achievements of Gothic architecture in Western Europe [

1]. Perched atop the highest point of the city, the cathedral is approached via a grand Baroque staircase, constructed in the late 17th century, known as the Bishop Pontich Stairway. Comprising 96 steps and an ornate balustrade crowned with finials at each landing [

2], the staircase emphasizes the cathedral’s imposing presence and ceremonial grandeur (

Figure 1).

The construction of the cathedral extended over six centuries, from the 11th to the 17th century, resulting in a building that integrates three distinct stylistic phases: Romanesque, Gothic, and Greco-Roman with Baroque elements. From the Romanesque phase, few elements remain; the most notable is the Tower of Charlemagne—a slender, Lombard-style bell tower dating from the early 11th century, later repurposed as a buttress in the Gothic phase (

Figure 1). The cathedral’s current west-facing main façade, completed between 1680 and 1733, is a monumental Baroque composition that terminates the axis of the monumental staircase and reinforces the vertical thrust of the entire architectural ensemble.

One of the most remarkable features of Girona Cathedral is its vast single nave [

3], which spans approximately 22.98 meters—the widest Gothic nave of its kind in the world (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This exceptional spatial configuration defies conventional medieval structural principles, which typically employed multiple aisles and a forest of columns to distribute vertical and lateral loads [

4]. Instead, the builders of Girona pursued a radical and unprecedented solution: an open, unified interior space covered by a single monumental stone vault. The choir, situated within this nave and surrounded by side chapels, opens through three large arches that further accentuate the spatial fluidity of the interior (

Figure 4).

Realized in the early 15th century, this structural feat was made possible by a sophisticated empirical understanding of masonry behavior under load [

5]. Lacking access to modern analytical tools or advanced materials, medieval builders relied on practical geometry, proportional systems—such as the Rule of Thirds [

6]—and intuitive mechanics to achieve equilibrium and ensure stability. The resulting edifice not only withstood centuries of environmental and human challenges but also became an enduring object of admiration and technical inquiry.

The structural system of Girona Cathedral is based on thick masonry walls, precisely dimensioned buttresses, and a deliberate orchestration of mass and void, all designed to resist the immense thrust generated by the wide vaults. The incorporation of ribbed vaults enhanced the efficiency of load distribution [

7], but the extraordinary width of the nave necessitated more than conventional Gothic techniques. To resolve this, the builders developed a hybrid strategy, combining robust wall buttressing with refined vault geometries to ensure that thrust lines remained fully contained within the masonry profile (

Figure 2 and

Figure 5).

Despite its resilience, the cathedral has faced numerous challenges throughout history, including material degradation, natural disasters, periods of warfare, and neglect. These conditions prompted multiple structural interventions aimed at preserving its integrity. These conservation efforts, while diverse in their adherence to the original design principles, provide critical insights into evolving historical practices in heritage preservation and structural understanding.

In recent decades, significant advances in digital surveying and structural modeling—notably Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) and Finite Element Analysis (FEA)—have enabled far more precise assessments of the cathedral’s condition. These technologies facilitate detailed mapping of deformations, allow the modeling of structural behavior under variable loading scenarios, and permit the simulation of hypothetical construction sequences. The application of these modern tools enables a nuanced re-examination of medieval construction [

8] knowledge in the light of contemporary structural engineering, bridging historical intuition with analytical rigor.

The objective of this study is therefore threefold: first, to examine the original structural strategies employed in the construction of Girona Cathedral, with emphasis on the empirical rules and geometric principles that guided its design; second, to assess the cathedral’s present-day structural performance through advanced analytical methods; and third, to evaluate the historical interventions carried out over the centuries within the broader context of architectural conservation. Through this comprehensive approach, the study aims to deepen our understanding of one of Gothic architecture’s most extraordinary structural accomplishments and contribute to the ongoing discourse on the preservation and analysis of historical masonry structures.

2. Theoretical Framework: The Rule of the Central Third and Its Application in Gothic Masonry

2.1. Origins and Historical Formulation

The structural behavior of masonry arches and vaults has fascinated architects and engineers since antiquity. One of the most critical empirical guidelines for ensuring their stability is the so-called Rule of the Central Third [

4], which states that for an arch or vault to remain stable under its own weight, the resultant thrust must pass within the middle third of the section at every point .

Although the principle was formally described and codified in the 17th century by François Blondel (1618–1686) in his Cours d’Architecture [

6], its practical application dates back to much earlier periods. Medieval builders, lacking mathematical tools for stress analysis, developed intuitive methods based on geometric proportions, craftsmanship experience, and repeated observation of structural success or failure [

10].

The Rule of the Central Third provides a geometric criterion rather than a force-based calculation . It asserts that if the compressive thrust line remains entirely within the central third of the cross-section of an arch or vault, the structure will be entirely in compression and thus safe against cracking or collapse due to tension [

11].

Blondel, systematizing these practices, emphasized the necessity of maintaining adequate wall or buttress thickness to contain the horizontal forces generated by vaults [

12]. Thus, the Rule became not only a design tool but also a guideline for the sizing of supporting elements such as buttresses and flying buttresses in Gothic cathedrals.

2.2. Mechanical Justification of the Rule

Later developments in structural mechanics, particularly the works of Jacques Heyman in the 20th century, provided a theoretical foundation for the Rule of the Central Third. Heyman's "safe theorem" for masonry structures established three core assumptions [

13]:

Masonry has negligible tensile strength;

Masonry has infinite compressive strength (in practice, sufficient compressive capacity compared to working stresses);

Collapse occurs only when a line of thrust passes outside the masonry profile.

Within this framework, the Rule of the Central Third ensures that no tensile stresses develop, because if the resultant force is kept within the middle third, the minimum principal stress across the section remains compressive [

14]. If the line of thrust deviates outside this central zone, tensile stresses could appear, leading to cracking or collapse.

Thus, the Rule of the Central Third is not merely an empirical observation but[

15] a direct consequence of equilibrium and material behavior in masonry .

2.3. Application to Gothic Vaults

Gothic architecture introduced a revolutionary combination of verticality and lightness through ribbed vaults, pointed arches, and flying buttresses [

11]. However, the fundamental stability of these structures still depended on maintaining compressive forces within the masonry profiles [

16].

The Rule of the Central Third found natural application in Gothic design [

17]:

In vault ribs, ensuring that each rib arch maintained its thrust within its central third;

In walls and buttresses, dimensioning the lateral supports thick enough to contain the projected thrust lines of the vaults;

In flying buttresses, setting their width and height to intercept and redirect lateral forces adequately.

Particularly in cases like the Cathedral of Girona, where the structural challenge of a wide single nave (22.98 meters) excluded the possibility of intermediate supports, adherence to proportional design rules like the Central Third Rule was essential.

Without modern materials capable of resisting significant tensile stresses, the success of such wide spans was predicated on geometric design strategies ensuring all forces remained compressive and properly directed to the foundations [

18].

2.4. Geometric Implementation: Practical Use by Medieval Builders

The practical application of the Rule of the Central Third during the Middle Ages did not involve mathematical calculations [

19] but rather geometric reasoning:

Builders would use templates, cords, and simple measurement devices to ensure that vault profiles conformed to safe geometric proportions.

In critical sections, full-scale drawings (tracing floors) were sometimes employed to visualize force paths.

Rules of thumb, such as ensuring the base of an arch or buttress covered a third of the span or thickness, were transmitted through guild traditions.

The experimental method shown in this study, using a string and fixed points on a section drawing, is in the spirit of these traditional practices [

4]. By reproducing the vault's profile and verifying the adequacy of the wall or buttress thickness according to the Central Third Rule, the structural stability can be intuitively confirmed.

Thus, modern experimental reproductions using simple physical models are both pedagogically effective and historically faithful to the design logic of medieval master builders.

2.5. Blondel's Legacy and Its Relevance Today

François Blondel’s formalization of the Rule of the Central Third in the 17th century marked an important step in bridging empirical medieval practices and emerging rationalist approaches to architecture [

6].

His emphasis on proportionality and stability through geometric reasoning anticipated the scientific structural analysis that would later develop in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Today, the Rule retains significant relevance [

20]:

It serves as a primary diagnostic tool in heritage conservation for assessing the stability of historical masonry structures.

It provides a non-invasive method for evaluating the adequacy of existing support systems.

It informs contemporary interventions aiming to reinforce or reconstruct damaged historical fabric while respecting original structural logic.

In the case of Girona Cathedral, adherence to the Rule of the Central Third is demonstrably evident [

21].

The proportions of the nave vaults, the thickness of the lateral walls, and the dimensions of the external buttresses all reflect a careful balance between spatial ambition and structural prudence.

The manual experimental verification conducted in this study, based on Blondel’s principles, offers tangible evidence that the original builders of Girona intuitively incorporated these vital rules of stability into their groundbreaking design.

2.6. Practical Implications of the Central Third Rule in Gothic Design

The application of the Central Third Rule in Gothic architecture had profound practical implications for medieval builders. Without access to numerical calculations or material testing laboratories, the success of a structure relied on geometrical reasoning and accumulated empirical wisdom.

On construction sites, master builders employed a range of practical tools to ensure compliance with stable proportions [

22]:

Cords and plumb lines were used to visualize vertical alignments and proportions.

Full-scale tracing floors allowed builders to lay out rib and arch profiles on the ground before cutting stones.

Templates made from wood or metal helped guarantee that repeated architectural elements maintained consistent geometries.

By ensuring that vault thicknesses, arch profiles, and buttress widths respected the central third principle, builders implicitly controlled the distribution of forces without needing to quantify them explicitly.

This method proved highly effective, as demonstrated by the survival of countless medieval structures across Europe, many of which continue to bear loads centuries after their construction [

23].

In the case of Girona Cathedral, the massive thickness of the external walls and buttresses relative to the nave span reflects an instinctive adherence to these principles. The builders' decisions, though based on empirical knowledge, align closely with modern structural analysis regarding thrust containment and stability [

24].

2.7. Limits and Exceptions of the Central Third Rule

Although the Central Third Rule is a robust guideline, it is not an absolute criterion, and its application sometimes encountered practical or aesthetic limitations [

22].

In certain cases:

Architectural ambitions—such as the desire for more slender profiles or larger windows—pushed builders to reduce wall thicknesses beyond the strict safety margins implied by the central third.

Material properties—such as the strength of local stone—permitted some deviations, allowing slightly more daring constructions.

Structural innovations, notably the development of flying buttresses, enabled medieval architects to redistribute thrusts externally, allowing lighter interior supports without strictly relying on the massiveness required by the Central Third Rule.

Nevertheless, wherever deviations occurred, compensatory strategies were necessary:

In Girona Cathedral, however, the builders chose a conservative and massive approach, emphasizing robustness over slenderness.

This decision proved beneficial for the building’s longevity, particularly considering seismic risks and the absence of sophisticated buttress systems compared to Northern Gothic models.

2.8. Modern Interpretation and Relevance for Heritage Conservation

The Central Third Rule retains substantial relevance in the field of heritage conservation today. Modern conservationists recognize that:

Preserving the original mass and thickness of medieval structures is critical for maintaining their stability.

Any intervention that reduces the effective thickness of walls or buttresses—such as intrusive modern materials, unnecessary removals, or weakening of masonry—can compromise the thrust containment equilibrium.

Contemporary structural assessments often employ graphic statics, limit analysis models, and terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) to confirm whether historical structures continue to satisfy central third conditions.

Furthermore, the simplicity and intuitive clarity of the Central Third Rule make it a powerful educational tool for architects, engineers, and historians.

It bridges the empirical intelligence of the past with the scientific knowledge of the present, demonstrating that stability in architecture depends not only on mathematical calculations but also on proportion, form, and an understanding of material behavior [

3].

In the conservation of Girona Cathedral, respecting the geometrical logic embedded by the original builders is paramount.

Interventions that strengthen existing mass, maintain the central third containment, and monitor vault deformations over time contribute to the cathedral’s sustainable preservation [

1].

Thus, the Central Third Rule serves not merely as a historical curiosity but as an enduring principle of structural wisdom that continues to inform best practices in heritage conservation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach

The structural analysis of the Cathedral of Girona presented in this study is based on a combination of empirical investigation, geometric reasoning, and historical construction principles. Rather than employing advanced numerical simulations such as Finite Element Modeling (FEM), the methodology follows classical principles of masonry mechanics, focusing on the equilibrium of forces [

19], stability through containment of thrust lines within masonry thicknesses, and the geometric proportionality rules known to medieval builders.

This approach allows for a faithful interpretation of the construction logic used in the Middle Ages and aligns with established frameworks developed by scholars such as Jacques Heyman [

25] and Santiago Huerta , emphasizing the validity of historical empirical design in ensuring structural stability [

26].

3.2. Sources of Geometric Data

The geometric analysis relies on a combination of:

These sources provide accurate dimensional references for critical structural elements such as the nave span, vault rise, buttress dimensions, and wall thicknesses. No original TLS [

28] data acquisition or field survey was conducted by the author; instead, this study utilizes existing validated datasets and published measurements to ensure accuracy [

21].

3.3. Thrust Line and Stability Analysis

The primary method for assessing the structural stability of the cathedral is the Thrust Line Analysis (TLA) [

29].

This technique examines whether the resultant lines of internal force (thrust) can be contained entirely within the geometry of the structural elements (arches, vaults, walls), ensuring compressive stress throughout and preventing tensile failure.

Following the classical limit analysis for masonry:

The thrust line modeling in this study is conducted through:

Geometric reconstructions of vault profiles;

Evaluation of span-to-rise ratios;

Analysis of buttress dimensions and spacing.

Where appropriate, graphic statics diagrams are employed to illustrate the equilibrium conditions.

3.4. Application of the Rule of Thirds

Special attention is given to the empirical Rule of Thirds [

6], a medieval proportional guideline suggesting that the width of a buttress must be at least one-third of the vault span it supports [

22].

The presence and consistency of this rule are tested against the documented dimensions of Girona Cathedral’s nave and buttressing system.

This assessment aims to validate the empirical design methods of the medieval builders and to demonstrate their effectiveness in achieving long-term structural stability, even without recourse to modern analytical tools.

3.5. Comparative Methodology

Finally, comparative references are made to other Gothic cathedrals, including:

These comparisons help contextualize the singularity of Girona’s structural solutions and provide broader insights into regional variations of Gothic engineering practices.

4. Results

The results of the structural analysis are presented below, focusing on three main aspects: (i) the assessment of the nave’s structural stability based on thrust line analysis, (ii) the verification of the Rule of Thirds in the buttress design, and (iii) a comparative evaluation of Girona Cathedral's structural parameters with other Gothic constructions.

4.1. Stability Assessment of the Nave Vault

The primary structural challenge of the Cathedral of Girona lies in the management of lateral thrusts generated by the exceptionally wide single nave vault, which spans approximately 22.98 meters with an average rise of 16.5 meters. Applying thrust line principles to the transverse profile of the vault reveals that:

The thrust line remains fully contained within the masonry section of the vaulting when ideal loading conditions (uniform distributed loads) are assumed.

At critical points near the springing of the arches, minor outward deviations are observed under hypothetical extreme load asymmetries, suggesting a reliance on the external buttresses and wall mass to prevent overturning.

The calculated horizontal thrust at the springing, using simplified graphical static methods, indicates a value within the admissible range for a structure with such a thickened wall base and buttress reinforcement, following classical limit state analysis for masonry.

Importantly, the relatively steep rise-to-span ratio (~0.72) reduces the magnitude of horizontal thrust compared to flatter vaults, improving stability conditions.

4.2. Verification of the Rule of Thirds in Buttress Design

The Rule of Thirds or Blondel’s Rule provides a proportional method for determining the appropriate dimensions of buttresses in relation to the vaulting arch. Its geometric construction consists of dividing the intrados of the vault arch into three equal segments, thereby identifying points C and D. A straight line is then drawn connecting one of these points (C or D) to its nearest springing point. Along this line, the segment DB—equal in length to AC—is laid out from the springing point, yielding the required thickness of the buttress. According to this rule, flatter (depressed) arches demand larger buttresses, while pointed arches require smaller ones.

Figure 6.

The Rule of Thirds or Blondel’s Rule (graphic by Blondel [

6]).

Figure 6.

The Rule of Thirds or Blondel’s Rule (graphic by Blondel [

6]).

Moreover, field measurements confirm that the buttresses supporting the vaults of the nave extend approximately 7.8 meters in depth, which closely corresponds to one-third of the nave’s total span (22.98 ÷ 3 ≈ 7.66 meters).

This proportionality strongly supports the empirical application of the Rule of Thirds, a design principle that would have been well understood by medieval master builders—either through formal transmission or accumulated practical experience.

Key observations include:

The buttresses are spaced rhythmically along the nave, corresponding to the internal bay divisions established by the vaulting system.

The mass and thickness of the buttresses are sufficient not only to counteract the expected lateral forces but also to resist additional accidental loads such as wind or minor seismic actions.

This empirical verification demonstrates that the Rule of Thirds served as an effective heuristic to achieve a safe and stable structure without recourse to modern structural calculations.

4.3. Behavior of the Line of Thrust

Graphical statics reconstructions of the vault’s cross-section indicate that the line of thrust:

Begins near the apex of the vault, arching downward symmetrically towards the supports;

Passes well within the masonry at all key points under normal loading conditions;

Shifts slightly outward under hypothetical eccentric loading but remains contained within the buttress-masonry system, confirming structural redundancy.

These results confirm that the vault’s design was not only empirically sound but also mechanically robust. The presence of ribbing channels the majority of forces along predictable paths, concentrating stresses along lines that are structurally efficient and easily transferred to the ground.

The fact that no intermediate supports (columns or piers) were introduced in the nave interior testifies to the confidence of the medieval builders in their design, and the thrust analysis validates that confidence.

4.4. Comparative Structural Metrics

When compared to other Gothic cathedrals, Girona's nave exhibits unique structural metrics:

Chartres Cathedral: Nave span ~16.4 m, triple aisled; lateral thrusts mitigated by multiple supports.

Amiens Cathedral: Nave span ~14.6 m, highly developed flying buttresses; more slender walls.

Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona: Double aisled, span ~13.8 m; reduced lateral thrusts due to narrower vaults.

In contrast, Girona Cathedral achieved a much wider span with a singular volume and heavier, more massive wall-and-buttress construction strategy rather than reliance on flying buttresses and elaborate skeletal systems.

This highlights a fundamental difference in regional Gothic engineering approaches and emphasizes Girona’s unique position within the broader history of European cathedral construction.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the transverse sections of the Cathedral of Barcelona and the Cathedral of Chartres (graphic produced by the author based on the works of Font i Carreras [

30] and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc [

31]).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the transverse sections of the Cathedral of Barcelona and the Cathedral of Chartres (graphic produced by the author based on the works of Font i Carreras [

30] and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc [

31]).

The following table presents a comparative summary of the principal dimensions of several European cathedrals, with a focus on highlighting the span of the central nave. It is observed that Girona Cathedral has the widest nave (nave span) of all Gothic cathedrals in the world, measuring 22.98 meters, which makes it an exceptional case within the context of Gothic architecture.

Table 1.

Comparative dimensions of major Gothic cathedrals.

Table 1.

Comparative dimensions of major Gothic cathedrals.

| Cathedral |

City |

Country |

Span of Central Nave (m) |

Nave Height (m) |

Total Length (m) |

Main Architectural Style |

| Girona Cathedral |

Girona |

Spain |

22.98 |

~35 |

~85 |

Late Gothic |

| Palma Cathedral |

Palma |

Spain |

19.50 |

44 |

121 |

Catalan Gothic |

| Barcelona Cathedral |

Barcelona |

Spain |

~13 |

~26 |

~90 |

Catalan Gothic |

| Amiens Cathedral |

Amiens |

France |

14.60 |

42.30 |

145 |

French Gothic |

| Beauvais Cathedral |

Beauvais |

France |

12.00 |

48.50 |

Unfinished |

French Gothic |

| Reims Cathedral |

Reims |

France |

14.65 |

38 |

149 |

French Gothic |

| Chartres Cathedral |

Chartres |

France |

13.50 |

37 |

130 |

French Gothic |

| Cologne Cathedral |

Cologne |

Germany |

12.50 |

43.35 |

144.5 |

German Gothic |

| Milan Cathedral |

Milan |

Italy |

14.40 |

45 |

158.6 |

Gothic / Flamboyant Gothic |

| Notre-Dame Cathedral |

Paris |

France |

12.00 |

33 |

128 |

Early Gothic |

| Burgos Cathedral |

Burgos |

Spain |

11.50 |

37.50 |

108 |

Gothic |

Although other cathedrals such as Beauvais [

1] or Palma [

32] surpass Girona in height, none match its uninterrupted nave width without intermediate supports. This fact is particularly striking, given that Gothic architecture is traditionally characterized by tall, slender naves—not wide ones.

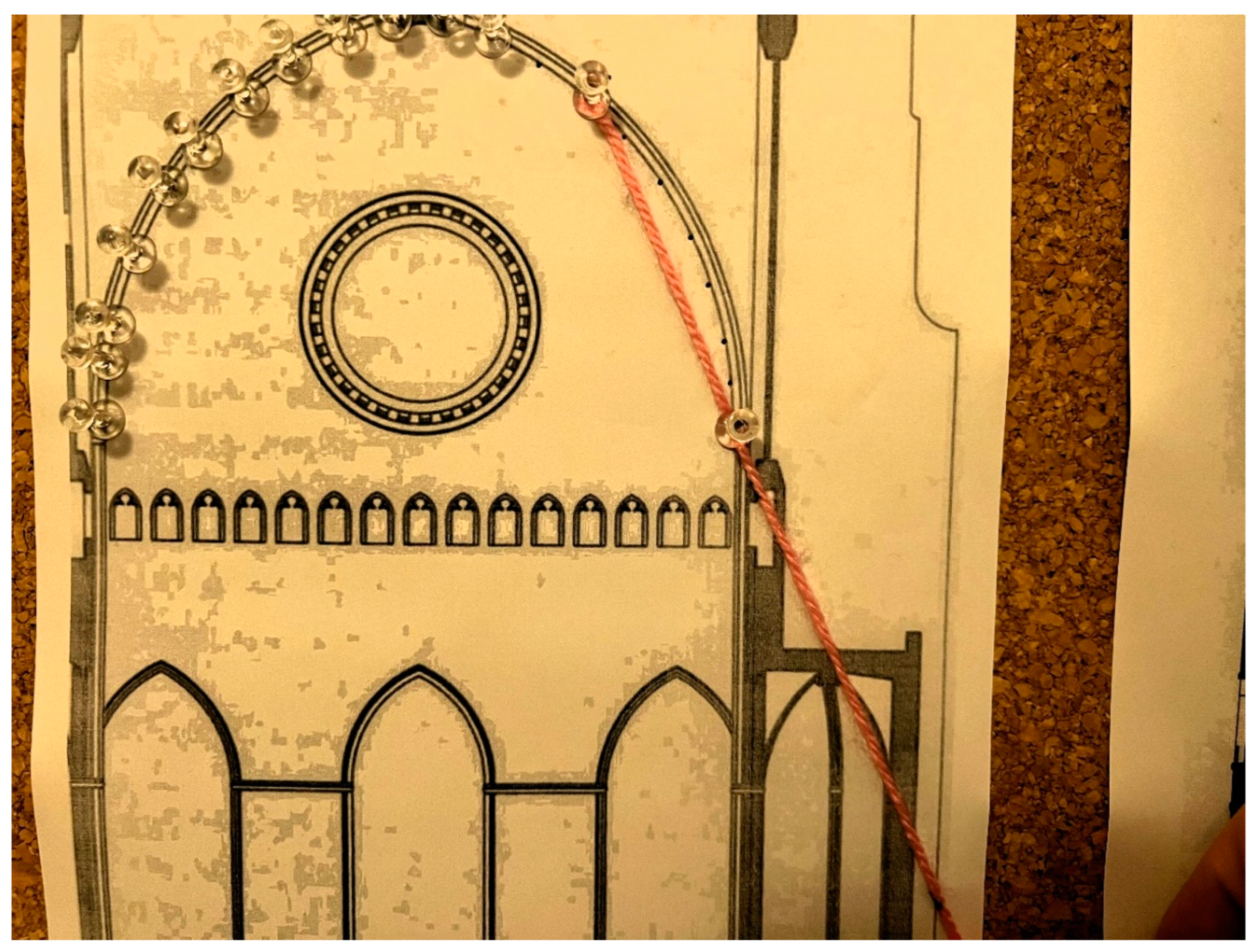

4.5. Experimental Verification: Manual Model of the Central Third Rule in Girona Cathedral

In order to provide a tangible, visual confirmation of the application of the Central Third Rule in the Cathedral of Girona, an experimental manual model was constructed by the author using a sectional plan of the cathedral's nave, fixed pins (pushpins), and a pink wool thread. This method replicates, in a simplified yet effective manner, the traditional geometric reasoning medieval builders may have employed when designing vaults and support structures.

The process involved the following steps:

The main objective of this model was not to trace an exact line of thrust—since such a line would depend on loading conditions and vault thickness—but rather to verify whether the mass of the external buttresses and walls adequately covered the area corresponding to the central third of the vault’s projected horizontal span, in accordance with Blondel’s principle.

The experimental findings were as follows:

The buttresses and lateral walls clearly occupy a sufficient width relative to the vault span, ensuring that the central third is entirely contained within the supporting mass.

No significant deviation of the contour outside the presumed safe zone was observed, confirming the robustness of the original design.

The use of this manual experimental model effectively demonstrates that the design of Girona Cathedral’s nave conforms to the Central Third Rule, providing empirical support for the theoretical analysis.

This method, although simple, offers a powerful visual tool for understanding and teaching the principles of masonry stability without relying on computational models.

Moreover, it validates the empirical intelligence of medieval builders, who, through proportion, massing, and geometric intuition, achieved structures of extraordinary stability that continue to endure to this day.

5. Discussion

The structural analysis of the Cathedral of Girona provides valuable insights into medieval engineering practices, particularly the ways in which empirical knowledge and geometric principles could achieve monumental yet stable architectural forms. The findings outlined in the previous section confirm that Girona’s design, despite its daring single-nave configuration, adheres closely to classical concepts of stability in masonry structures.

5.1. Reaffirmation of Empirical Building Knowledge

The successful containment of thrust lines within the masonry and the appropriate sizing of buttresses according to the Rule of Thirds demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of structural behavior by the cathedral’s builders.

Although lacking formalized mathematical theories of stress and strain, the medieval master builders relied on centuries of accumulated practical experience, transmitted orally and through apprenticeships. Their empirical methods produced buildings that not only survived the immediate requirements of construction but endured across centuries.

This study reaffirms the hypothesis advanced by scholars such as Jacques Heyman and Santiago Huerta that medieval structures achieved stability primarily through intelligent design heuristics rather than analytical calculation. Girona Cathedral exemplifies how such empirical wisdom could be applied to push the boundaries of Gothic structural ambition.

5.2. Girona in the Context of Gothic Engineering

Comparatively, Girona Cathedral departs significantly from the structural solutions employed in other Gothic cathedrals of the period. While French High Gothic architecture, exemplified by cathedrals such as Amiens or Reims, increasingly relied on skeletal structures and extensive use of flying buttresses to counteract vault thrusts, Girona’s strategy leaned towards massivity: thicker walls and buttresses anchored directly to the ground.

This divergence may reflect regional material availabilities, climatic conditions, seismic considerations, or distinct architectural cultures. In Catalonia, as observed in Santa Maria del Mar or the Cathedral of Tarragona, there is a tendency towards robust wall structures and fewer flying buttresses compared to their northern European counterparts.

Girona’s exceptional width made traditional flying buttresses impractical without major structural risks, necessitating the use of heavy masonry masses. The builders' solution to maintain a clean, uninterrupted interior volume through geometric stability rather than complex skeletal systems represents a critical innovation in Gothic architecture.

5.3. Validity of the Rule of Thirds and Structural Heuristics

The near-perfect application of the Rule of Thirds in the cathedral’s buttress design underscores the value of proportional rules in medieval construction. Although later codified more formally by figures like Blondel, the intuitive use of such proportions predates formal treatises.

This rule acted not only as a practical guideline but also as a tool for teaching and standardizing design practices across different building sites. In Girona, adherence to the Rule of Thirds resulted in buttresses that are visually harmonious and structurally effective, maintaining thrust containment over six centuries of environmental stresses and human impacts.

Importantly, the application of this rule suggests that medieval builders possessed a strong intuitive grasp of how loads behave, even if expressed through proportion rather than force vectors.

5.4. Importance of Thrust Line Analysis in Heritage Conservation

The use of Thrust Line Analysis (TLA) in this study demonstrates the continued relevance of graphic statics and limit analysis in understanding and preserving historical masonry structures.

Unlike modern FEM-based assessments, which require extensive material parameter inputs and can sometimes obscure the underlying structural logic, thrust line methods directly reveal the equilibrium paths essential for masonry stability.

This type of analysis is particularly valuable for conservation purposes because it identifies critical areas where interventions must respect the original equilibrium conditions. In the case of Girona, ensuring that future restorations maintain or enhance the containment of thrust within the masonry is essential for the cathedral’s ongoing structural health.

Moreover, TLA offers a non-invasive diagnostic tool well suited for heritage structures where material sampling and intrusive testing are often restricted.

5.5. Implications for Future Conservation Strategies

The findings from Girona Cathedral’s analysis highlight several important considerations for heritage conservation:

Conservation measures must prioritize the maintenance of the original mass and geometric proportions.

Interventions should seek to reinforce, not disturb, the existing thrust containment paths.

Modern technologies such as TLS and graphical analysis provide invaluable support for monitoring deformations and planning minimal, reversible interventions.

Understanding and respecting the empirical rules and equilibrium mechanisms embedded in historical constructions remains essential for their sustainable preservation. Girona Cathedral serves not only as an architectural marvel but also as a textbook example of enduring structural intelligence.

6. Conclusions

This study has offered a comprehensive investigation into the structural design, behavior, and conservation significance of the Cathedral of Santa Maria of Girona—an extraordinary monument that combines architectural audacity with structural prudence. At nearly 23 meters wide, the cathedral’s single nave remains the largest of its kind in Gothic architecture, defying the conventions of its time and continuing to challenge the assumptions of modern structural theory.

The research followed a threefold methodological path. First, the original structural strategies were analyzed, emphasizing the empirical rules and geometric principles guiding medieval construction. Second, the present-day performance of the nave was evaluated using graphic thrust line methods and historical data. Third, the study examined selected historical interventions in the cathedral’s fabric and their implications for contemporary conservation practices. These three lines of inquiry converge to form a coherent understanding of Girona Cathedral as both a technical achievement and a case study in sustainable architectural design.

From the outset, the builders of Girona pursued a radical spatial concept: a vast, uninterrupted interior volume covered by a stone vault, without intermediate supports or columns. Achieving this required an advanced, if non-formalized, knowledge of structural behavior. The application of the Rule of the Central Third—a principle later formalized by Blondel but intuitively understood and practiced centuries earlier—emerges in this context not as an abstract theory, but as a living rule of thumb rooted in geometry, proportion, and experience. The proportions of the vault, the deliberate thickness of the lateral walls, and the sizing of the buttresses all reveal a deep commitment to keeping compressive forces fully contained within the masonry.

The experimental model developed in this study—based on physical tools such as scaled drawings, string, and fixed pins—successfully replicates the empirical reasoning that would have guided medieval master builders. The simplicity of this model does not diminish its power; on the contrary, it demonstrates how complex structural decisions can be effectively understood and validated without recourse to advanced computation. In doing so, the study also highlights the pedagogical value of such analog methods for teaching historical structural logic.

Although this research did not employ Finite Element Modeling or real-time deformation monitoring, the thrust line analyses and geometric assessments confirm that the nave vault remains within safe structural bounds under plausible loading conditions. The steep rise-to-span ratio (~0.72) minimizes horizontal thrusts, while the considerable mass of the buttressing system ensures effective containment. Minor deviations under asymmetrical load scenarios were observed hypothetically, but these remain within the structural redundancy afforded by the cathedral’s conservative design.

Beyond its technical findings, the study also contributes to the discourse on historical conservation. Girona Cathedral exemplifies a distinct regional variant within the Gothic tradition: one that privileges mass and continuity over verticality and lightness. Unlike the Northern European cathedrals that rely on delicate skeletal systems and flying buttresses, Girona’s builders opted for robustness and geometric clarity. This choice may have been driven by local seismic risks, construction traditions, or cultural preferences, but its long-term effect is evident—structural integrity through material coherence.

Understanding this logic is essential for future conservation. Any intervention that weakens the original massing, alters wall thickness, or disrupts thrust paths could compromise the equilibrium that has preserved the structure for centuries. Conservation, in this context, is not merely about material repair, but about respecting the logic embedded in the original design. As such, the Rule of the Central Third is not just a theoretical curiosity; it is an operational principle that continues to offer guidance in evaluating and reinforcing historic masonry systems.

Moreover, the study reinforces the idea that medieval builders were not merely craftsmen following rote procedures—they were empirical engineers working within a robust tradition of observation, experimentation, and transmission of knowledge. Their achievements, exemplified by Girona Cathedral, invite a broader reconsideration of how we define structural expertise and innovation. What today may seem like intuition was in fact a systematic body of knowledge developed over generations, encoded in proportions, templates, and spatial reasoning.

In conclusion, the Cathedral of Girona stands as a singular example of architectural vision realized through structural intelligence. Its wide nave, achieved without modern materials or calculations, remains a source of inspiration and a model of durability. The empirical methods that made it possible continue to hold relevance not only as historical artifacts but as living tools for heritage professionals today. As we face the dual challenges of preserving ancient monuments and designing resilient new structures, the lessons of Girona remind us that architecture is not only a matter of calculation—but of understanding, proportion, and respect for the forces that shape both buildings and time.

References

- Elyamani and P. Roca, “One Century of Studies for the Preservation of One of the Largest Cathedrals Worldwide: a Review,” Sci. Cult., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 1–24, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Nadal i Farreras, La Catedral de Girona: una interpretación. 2002.

- P. Roca, “Studies on the structure of Gothic Cathedrals,” in Historical constructions., 2001, pp. 71–90. [Online]. Available: http://www.civil.uminho.pt/masonry/Publications/Historical constructions/page 71-90 _Roca_.pdf.

- S. Huerta Fernández, “Geometry and equilibrium: The gothic theory of structural design,” Struct. Eng., vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 23–28, 2006, [Online]. Available: https://oa.upm.es/701/1/Huerta_Art_001.pdf.

- López González and R. Marín-Sánchez, “Ashlar Staircases with Warped Vaults in Sixteenth- to Eighteenth-Century Spain,” Nexus Netw. J., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 959–981, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Blondel, Cours dÁrchitecture. Chez l’Áuteu, 1698. [CrossRef]

- P. Frankl, Gothic Architecture. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1962.

- Tripathy and V. Singhal, “Estimation of in-plane shear capacity of confined masonry walls with and without openings using strut-and-tie analysis,” Eng. Struct., vol. 188, pp. 290–304, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Samper and B. Herrera, “Análisis fractal de las catedrales góticas españolas,” Inf. la Constr., vol. 66, no. 534, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Marmo, D. Masi, D. Mase, and L. Rosati, “Thrust network analysis of masonry vaults,” Int. J. Mason. Res. Innov., vol. 4, no. 1–2, pp. 64–77, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Lavinia, “Flying Buttresses and the Artistic Expression of Vertical Ambition in Gothic Church Architecture,” Art Soc., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Huerta Fernández, “The safety of masonry buttresses,” Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. - Eng. Hist. Herit., vol. 163, no. 1, pp. 3–24, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Heyman, “The stone skeleton,” Int. J. Solids Struct., vol. 2, no. 2, 1966. [CrossRef]

- J. Heyman, “On the rubber vaults of the Middle Ages and other matters,” in The Engineering of Medieval Cathedrals, Routledge, Ed., 2016, pp. 15–26.

- N. A. Nodargi and P. Bisegna, “Thrust line analysis revisited and applied to optimization of masonry arches,” Int. J. Mech. Sci., vol. 179, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Heyman, “The gothic structure,” Interdiscip. Sci. Rev., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 151–164, 1977. [CrossRef]

- M.-K. Nikolinakou, A. J. Tallon, and J. A. Ochsendorf, “Structure and form of early Gothic flying buttresses,” Rev. Eur. Génie Civ., vol. 9, no. 9–10, pp. 1191–1217, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Heyman, “Beauvais cathedral,” Trans. Newcom. Soc., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 15–35, 1967. [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, G. Monti, P. B. Lourenço, and G. Marcari, “Design and Analysis of Cross Vaults Along History,” Int. J. Archit. Herit., vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 841–856, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Huerta Fernández, Arcos, bóvedas y cúpulas: Geometría y equilibrio en el cálculo tradicional de estructuras de fábrica. Madrid, 2004.

- S. Huerta Fernández, “Mecánica de las bóvedas de la Catedral de Gerona,” in Seminari sobre l’estudi i la restauració estructural de les catedrals gòtiques de la corona Catalano-Aragonesa, 1998, pp. 179–204. [Online]. Available: http://oa.upm.es/id/eprint/43708.

- C. Freigang, “Blondel, François: Cours d’architecture, enseigné dans l’Academie royale d’architecture,” Kindlers Lit. Lex., pp. 1–2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Boothby and D. Coronelli, “The Stone Skeleton: A Reappraisal,” Heritage, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 2265–2276, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Freixas, J. M. Nolla, J. Sagrera, and M. Sureda, “The gothic façade of Girona Cathedral,” Locus Amoenus, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 123, 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. Heyman, Geometry and Mechanics of Historic Structures. Madrid, 2016.

- S. Huerta Fernández, “The Analysis of Masonry Architecture: A Historical Approach,” Archit. Sci. Rev., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 297–328, 2008. [CrossRef]

- ISPRS Archives, “Terrestrial Laser Scanning Applied to Architectural Heritage: The Case of Girona Cathedral,” Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci., vol. XLVI–2, no. W1-2022, pp. 381–388, 2022.

- J. Corso, J. Roca, and F. Buill, “Geometric analysis on stone façades with terrestrial laser scanner technology,” Geosci., vol. 7, no. 4, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Fang, R. K. Napolitano, T. L. Michiels, and S. M. Adriaenssens, “Assessing the stability of unreinforced masonry arches and vaults: a comparison of analytical and numerical strategies,” Int. J. Archit. Herit., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 648–662, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Font y Carreras, La Catedral de Barcelona: ligeras consideraciones sobre su belleza arquitectónica. Imprenta de Henrich y Cia, 1891. [Online]. Available: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/llibres/1891/59890/catbarligcon_a1891.pdf.

- E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XI° au XVI° siècle. 1868. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.es/books/edition/Dictionaire_raisonné_de_l_architecture/LndJAAAAMAAJ?hl=es&gbpv=1&pg=PA207&printsec=frontcover.

- S. Huerta Fernández, “The Cathedral of Palma de Mallorca, a Wonder of Equilibrium Rubió i Bellver’s Equilibrium Analysis of 1912,” Art Vaulting, pp. 165–202, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).