Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Simulation Environment: BlueSky

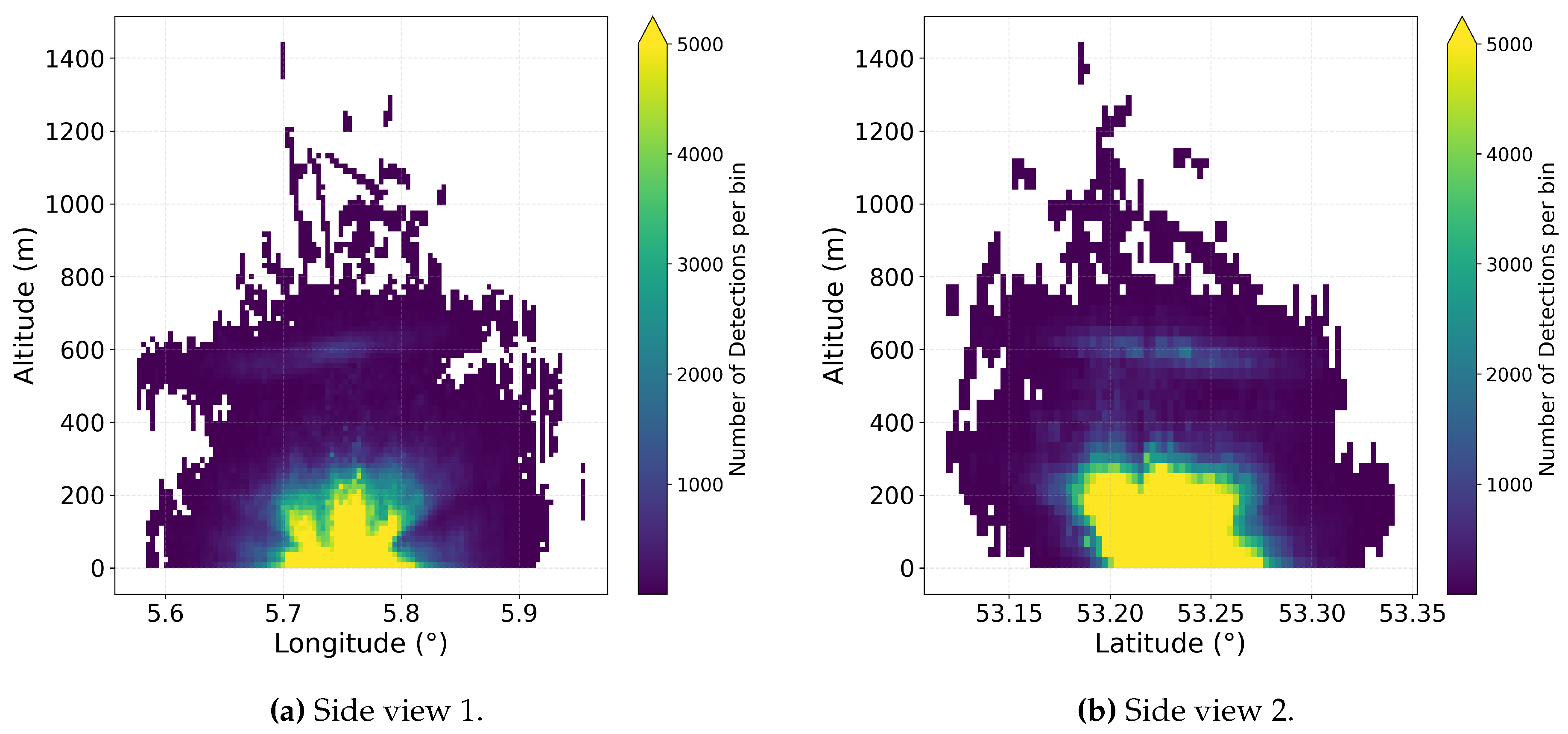

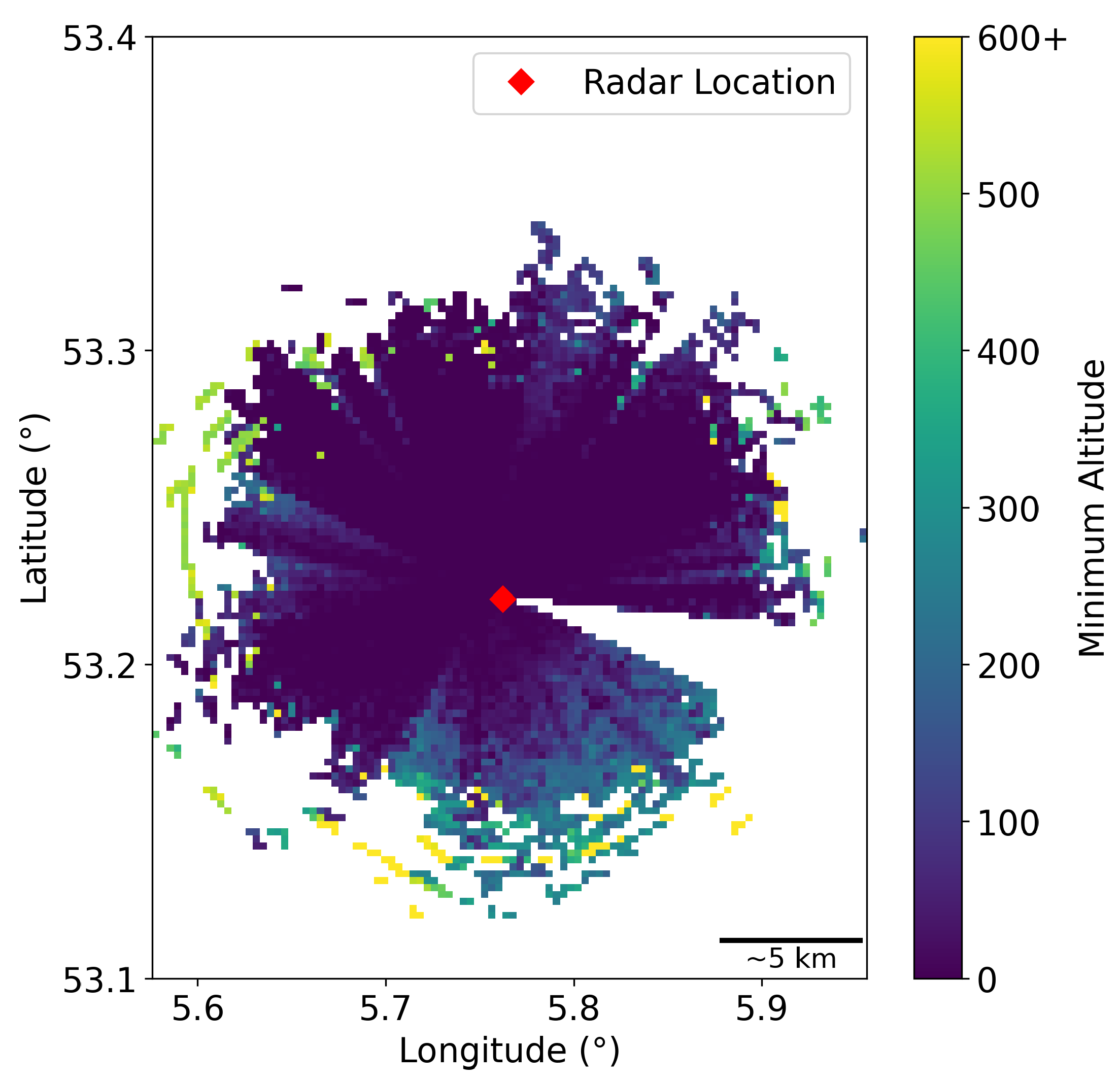

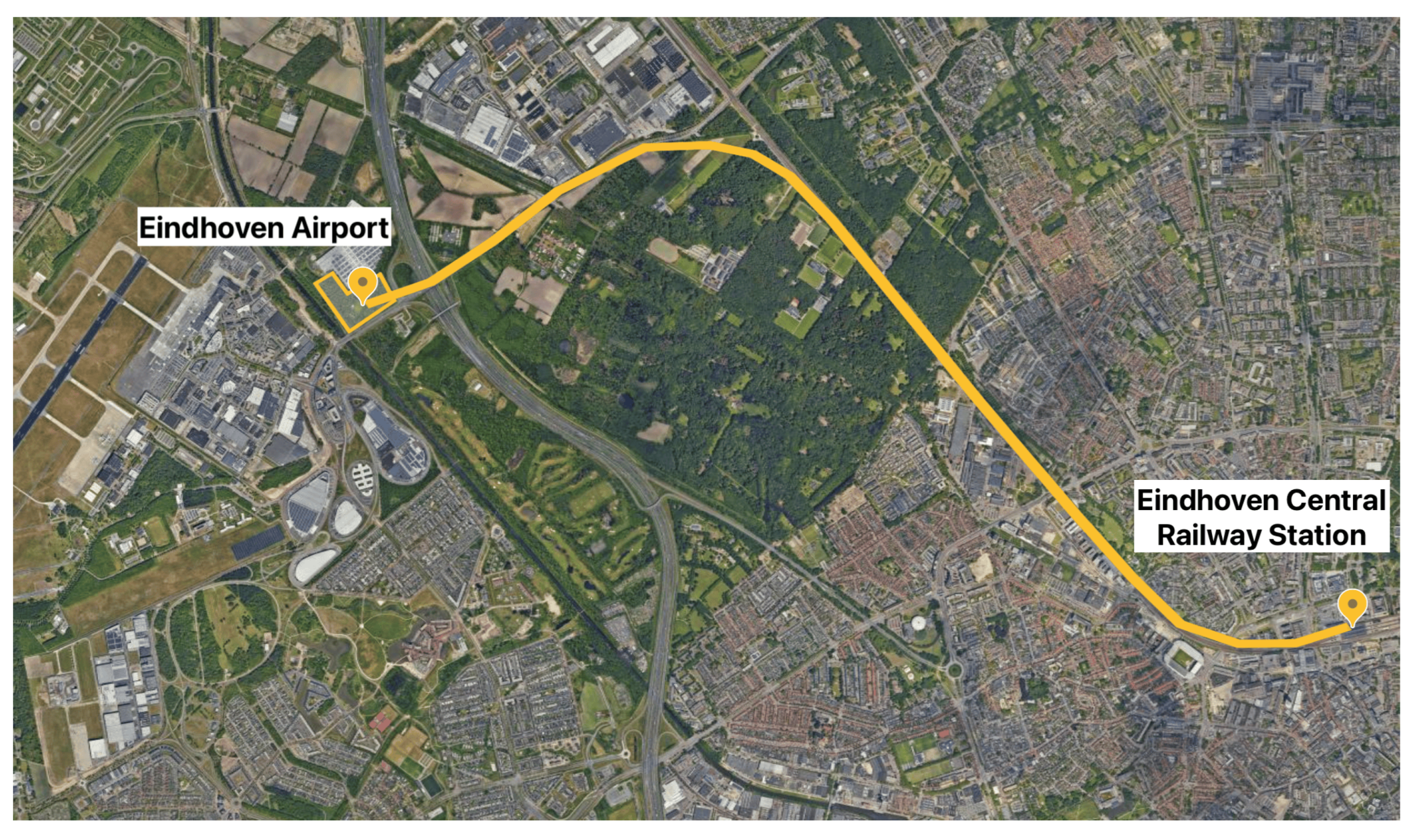

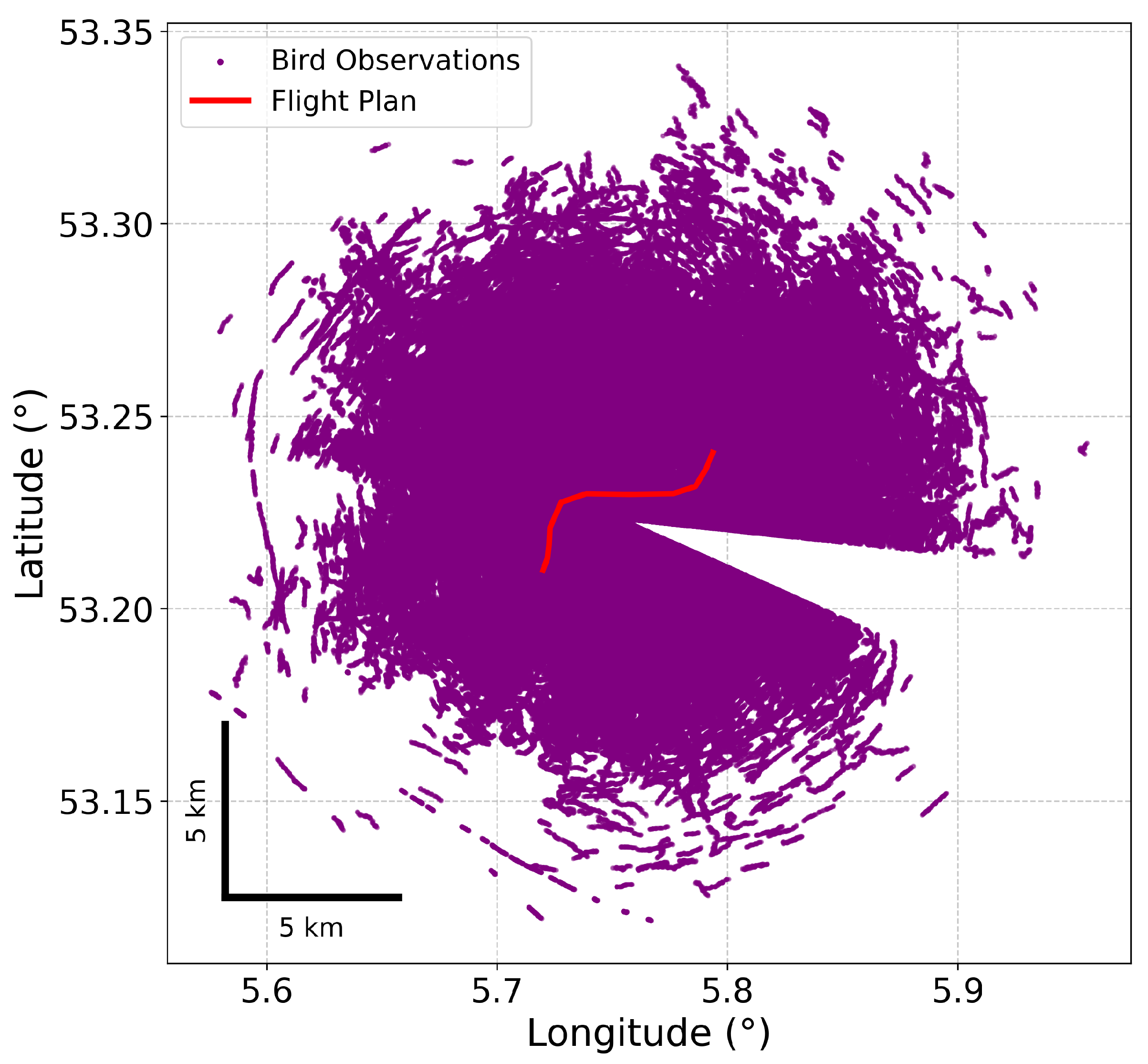

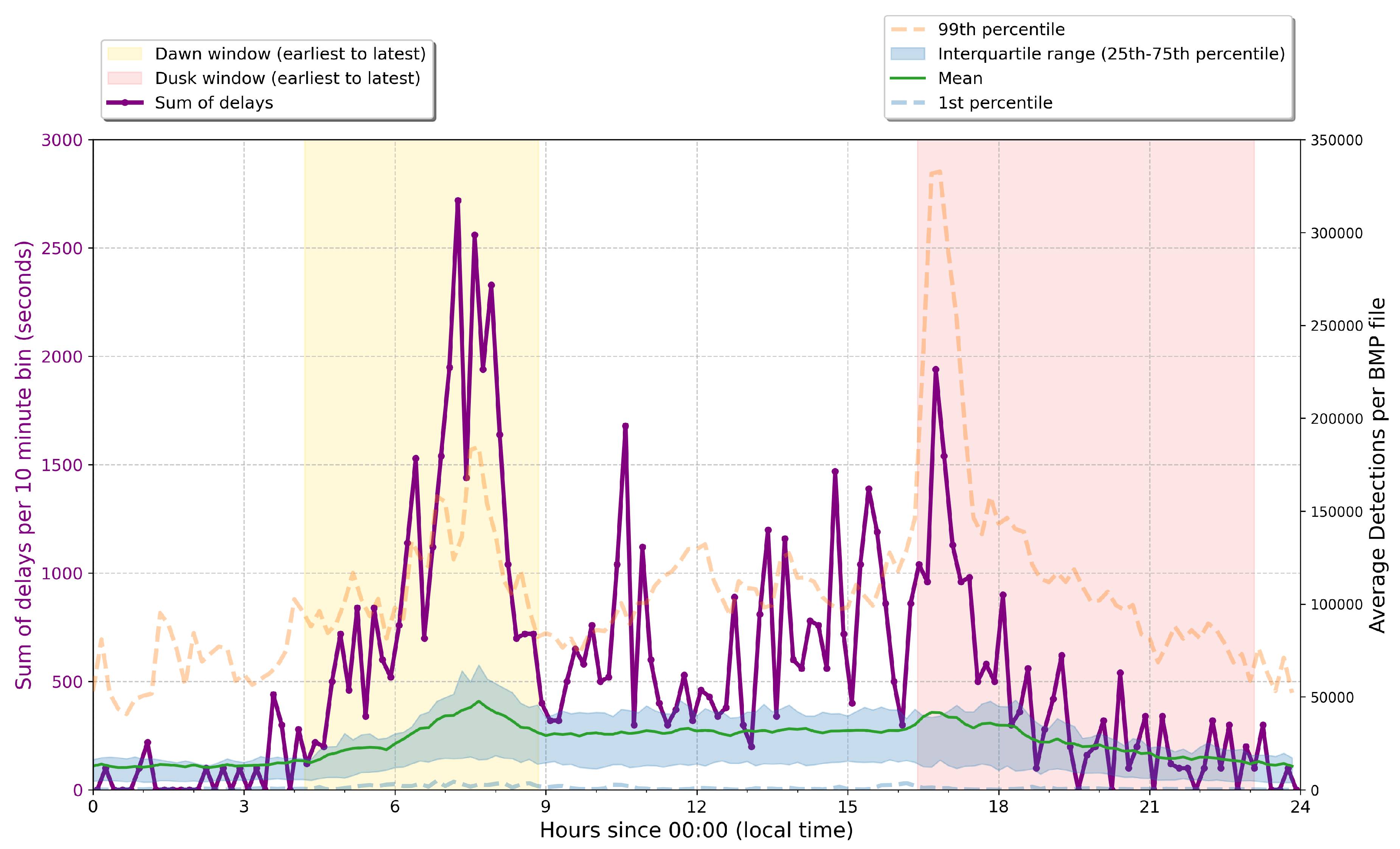

2.2. Bird Dataset and Flight Plan

2.3. UAM-CAS Implementation

2.3.1. UAM-CAS

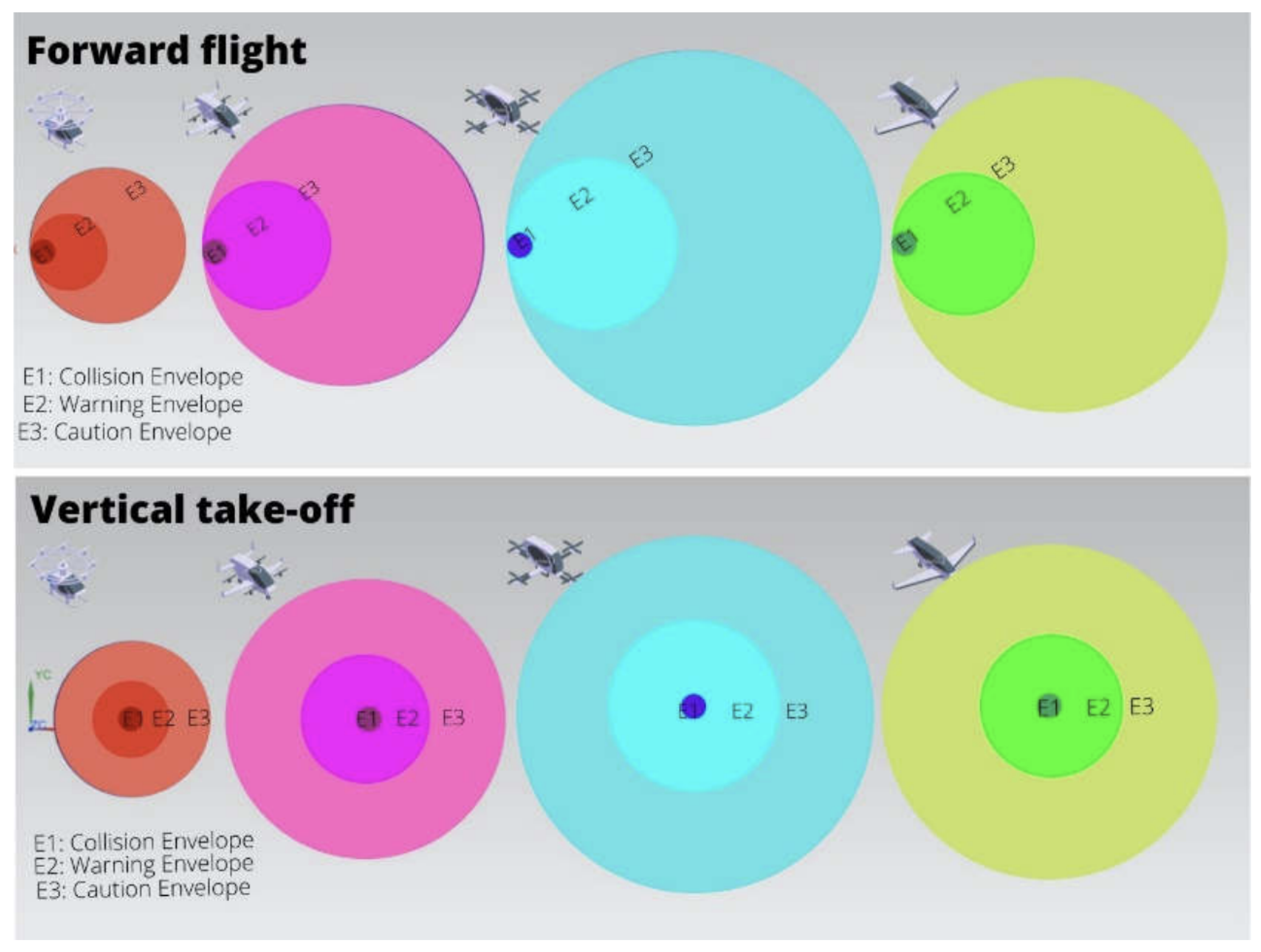

2.3.2. Safety Envelopes

- UAM configuration (dimensions and cruise speed). To understand the influence of UAM configuration on collision rates, and the efficacy of the proposed UAM-CAS in reducing them, it is important to consider the differentiating factors between each of the UAM configurations. In this study, these are considered to be the cruise speed and physical dimensions of the UAM aircraft which are presented in Table 1. Four UAM aircraft configurations (multicopter, liftcruise, vectored thrust, tilt rotor) were adopted from the previous study [16], which found that avoidance capabilities can vary substantially between these four common UAM aircraft configurations. In this study, the horizontal dimensions () and cruise speeds of the four UAM configurations are adopted from [16], which sources values from current UAM aircraft in development. These values are shown in Table 1. The vertical dimension () was taken as for all four UAM aircraft configurations, by averaging over the vertical dimensions of two UAM aircraft available in literature [27,28].

- The relative horizontal and vertical speeds between the UAM aircraft and the bird. Calculation of these values was implemented in the BlueSky bird plugin. The UAM-CAS avoidance logic, which currently consists of simple actions such as stopping and hovering, was found to react excessively and/or inappropriately to high-speed and uncharacteristic bird behaviour. As such, birds with vertical speed exceeding 5 / or horizontal speed exceeding 20 / are ignored in envelope calculations, meaning that avoidance with such birds is not carried out. Actual collisions with these birds are still logged. Avenues to improve UAM-CAS to overcome this are discussed in Section 4.2.

- System () and pilot reaction times () to the presence of a bird. is the autonomous system’s reaction time, counted from (caution envelope) incursion to the initiation of the automated tactical manoeuvre. is the pilot’s reaction time counted from (warning envelope) incursion to pilot action [16]. These were set in Panchal et al’s study to be and [16]. The system reaction time () used in [16] was found to be highly conservative, leading to a high number of potentially unnecessary avoidance manoeuvres in preliminary simulations. Hence, was reduced to 5 for this study. was sourced from previous research [29], but in this study was set to 5 . Its reduction is justified by the expectation that the pilot would receive advanced warning of an intruder once the caution envelope is intruded. The reductions of and in this study align with reductions in reaction times derived by Peinecke et al. [30] due to automated systems eliminating pilot latency.

2.3.3. Bird Detection Logic

- Distance Check: The horizontal and vertical distances between the UAM aircraft and each bird were calculated. These distances were then compared against the dynamically computed dimensions of the three envelopes for that specific aircraft-bird pair.

- Frontal Angle Check: For the caution and warning envelopes, an additional frontal angular filter was applied. Only birds within a specified frontal arc relative to the UAM’s heading were considered for triggering tactical or warning alerts to prevent unnecessary reactions to birds that are abeam or behind the aircraft. This angle was set to for the caution envelope and for the warning envelope.

2.3.4. Collision Avoidance

-

Strategic avoidance

- Original concept: Departure is delayed by five minutes if birds are detected close to the take-off area and their movement is classified as critical.

-

Implementation in this study: Strategic avoidance is activated if birds are detected within a “strategic envelope” at the time of departure. This strategic envelope was introduced in this study as a cylindrical 3D space along a certain distance of the initial leg of the flight plan. This yields two parameters which define the strategic envelope, namely a cylindrical length and cross-sectional radius. These were set at 500 and 100 respectively as an initial assumption to enable simulation.In addition, a strategic avoidance delay parameter of 30 seconds was used. This specifies the amount of time to wait, after a delayed take-off due to a strategic envelope intrusion, before trying to take-off again. If birds still intrude the strategic envelope after this delay, the bird plugin restarts the logic by initiating strategic avoidance again. The chosen delay parameter of 30 seconds is shorter than the five minutes of the original concept, to balance safety with service regularity.

-

Tactical avoidance

- Original concept: An automated “hover and descend” tactical manoeuvre is initiated when an intruder enters the outermost caution envelope.

-

Implementation in this study: Similar to the original concept, an automated tactical manoeuvre is initiated when an intruder enters the outermost caution envelope. The length of time for which to maintain the hover manoeuvre was set at 20 . Several changes were made to the original concept to better suit it towards real-world bird data.First, it was identified in test runs that with the default tactical avoidance action of hover and descent, the aircraft may inadvertently descend towards birds which are below the aircraft. To improve this behaviour, if at the point of detection in the caution envelope, the bird is above the UAM aircraft in altitude, then the UAM aircraft will hover and descend. If the bird is below, the UAM aircraft will hover and ascend.Second, if the UAM aircraft is in the ascent or descent phase and tactical avoidance is initiated, it hovers at its current altitude rather than ascending or descending. This maintains predictability and pilot control authority during these critical flight phases.Third, a tactical avoidance delay period is introduced. Upon the tactical avoidance action completing and the aircraft resuming its flight plan, the caution envelope is monitored for 10 . If any bird is detected during this window, tactical avoidance is considered unsuccessful and emergency avoidance is triggered.

-

Emergency avoidance

- Original concept: If the automated tactical avoidance manoeuvre is unsuccessful in resolving the conflict, resulting in an intrusion of the warning envelope, the human pilot must take over to resolve the conflict in the emergency avoidance phase.

-

Implementation in this study: To model the human intervention as a deterministic procedure in a simulation is challenging and beyond the scope of this study. As such, emergency avoidance is applied in this study by assuming the human always successfully resolves the conflict. This is implemented by clearing the aircraft from the simulation and starting the next scheduled flight.In the case of bird(s) intruding the warning envelope, if the aforementioned definition of emergency avoidance were implemented, no bird would reach the collision envelope, so collisions would drop to zero. As such, emergency avoidance was not implemented in this case. Therefore, the number of collisions in the simulations is expected to be larger than in reality.Emergency avoidance in this study is also triggered if, within 10 of resuming the flight plan after tactical avoidance, bird(s) enter the warning envelope. In this case, emergency avoidance was implemented. The assumption of successful resolution in this case was deemed justified because, immediately following tactical avoidance, the UAM aircraft would be travelling at low speeds, and the pilot would have heightened awareness of nearby birds through both visual observation and assistance from automated detection systems.

2.4. Simulation Set-Up

2.5. Simulation Outputs

- The reaction of birds to aircraft due to their movement and noise [11] was not modelled. Indeed, in the study by Metz into an Air Traffic Control bird advisory system for current commercial aviation [20], it was found that there was a threefold overestimate of bird strikes which was partly attributed to not modelling the reaction of birds to aircraft.

- Some collisions that occur in the simulation may not occur in reality due to the pilot’s response to birds which enter the warning envelope, which was not modelled in this study.

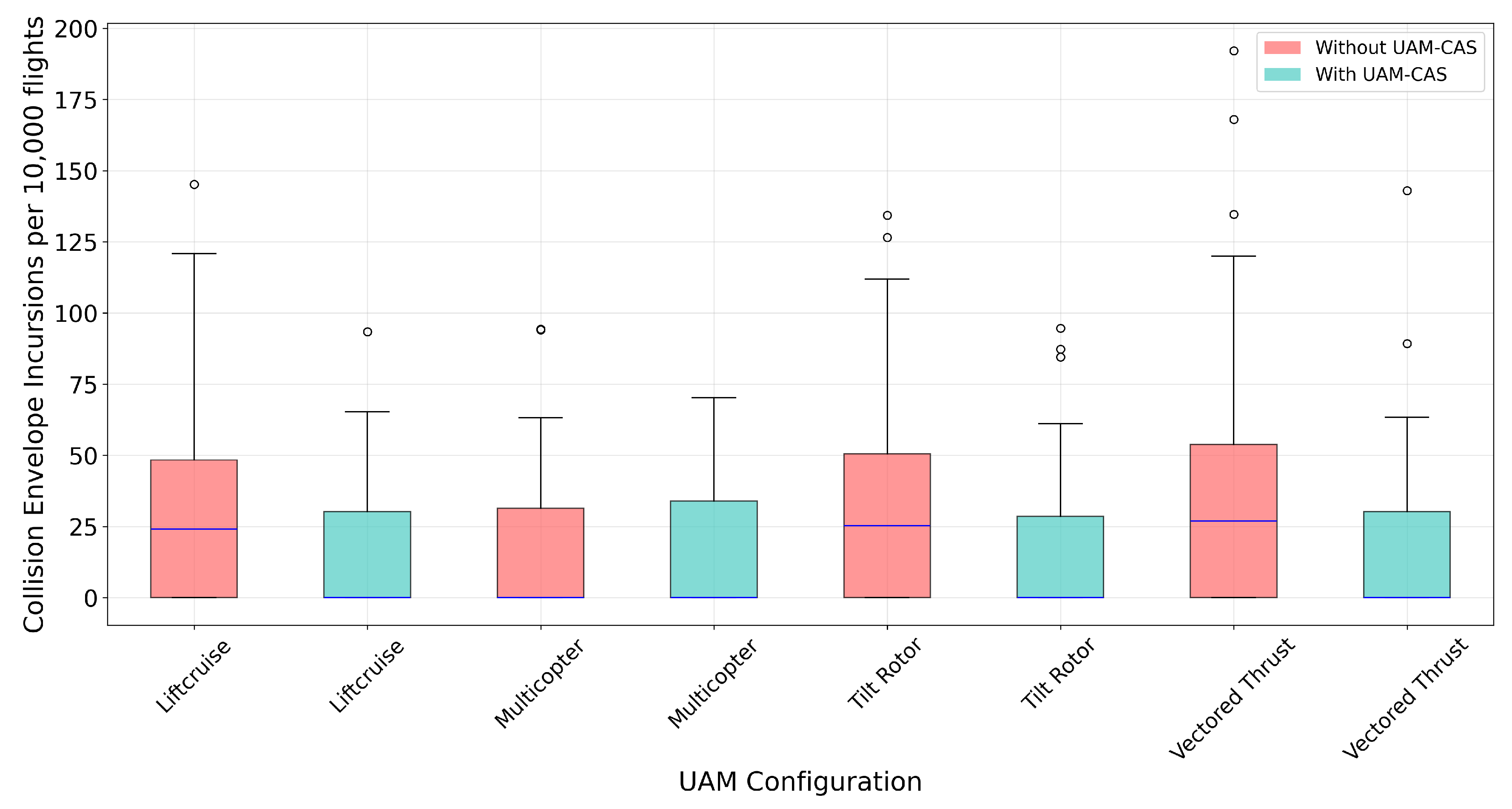

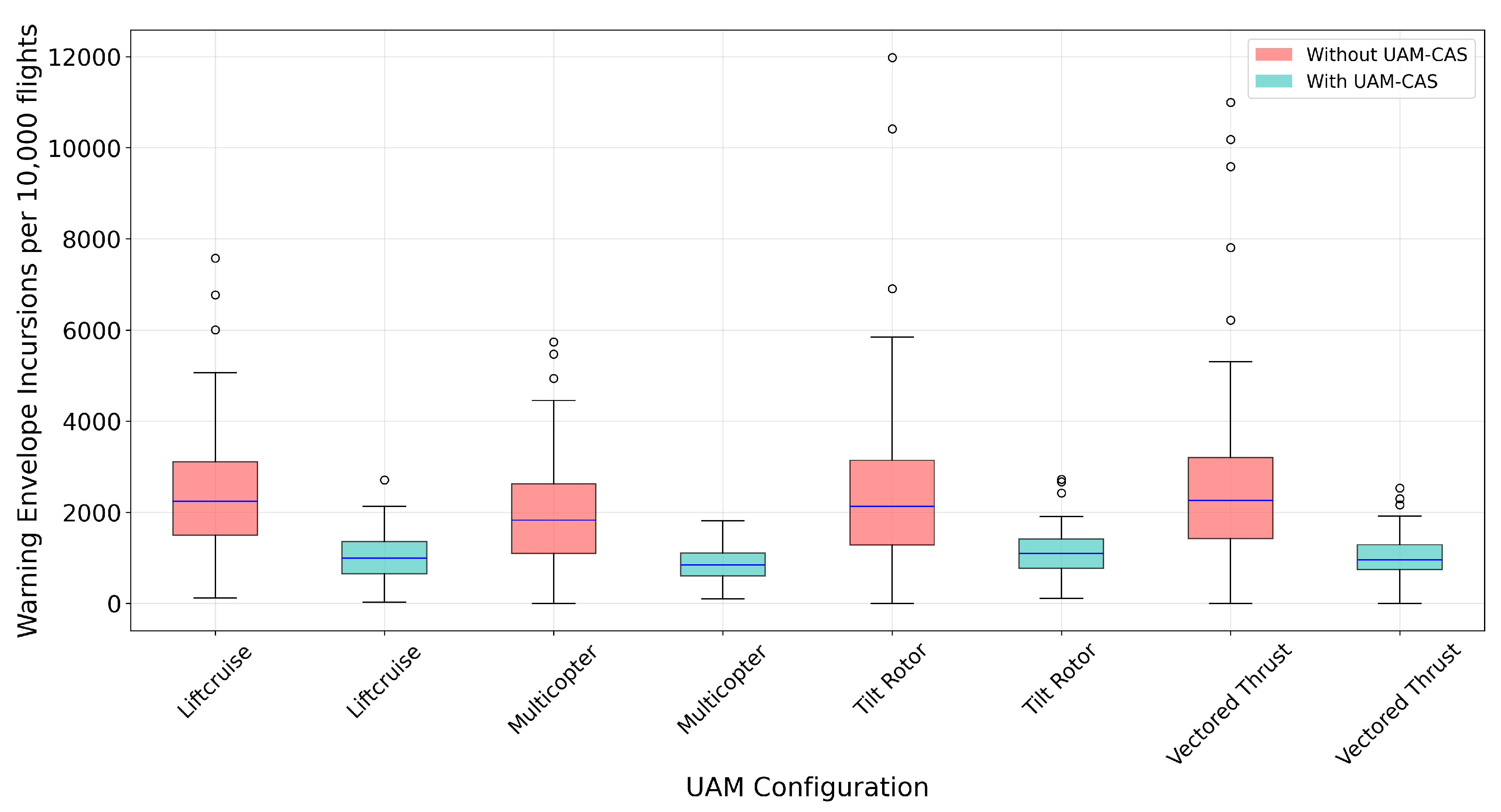

2.6. Significance of UAM Configuration on Collision Rates

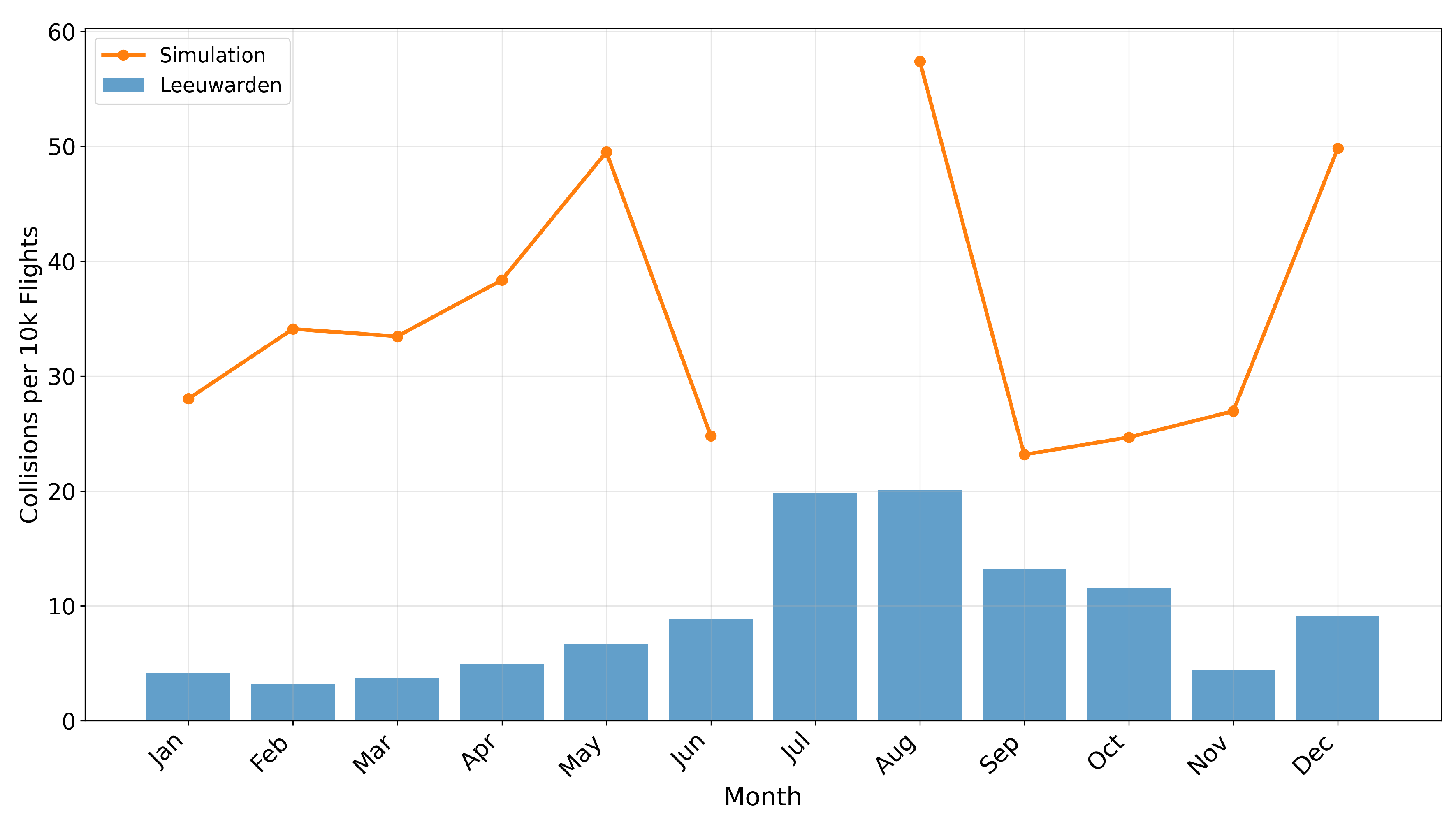

2.7. Validation of Baseline Simulation and Collision Trends

- The Leeuwarden Air Base bird-strike data is in relation to typical movements at Leeuwarden Air Base, which are military aircraft, which have much different flight profiles from those of a UAM air taxi service.

- The simulation is performed using 84 days of bird data in the year 2023, whereas the Leeuwarden Air Base bird-strike data is collected over the period 2000 to 2022. Hence, the sample size of the simulation results is relatively small.

- The Leeuwarden Air Base bird strike data does not include reliable data on the year 2023 because the runway was closed for part of that year (RNLAF Bird Strike Database. Hans van Gasteren, personal communication, 19 December 2024).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation

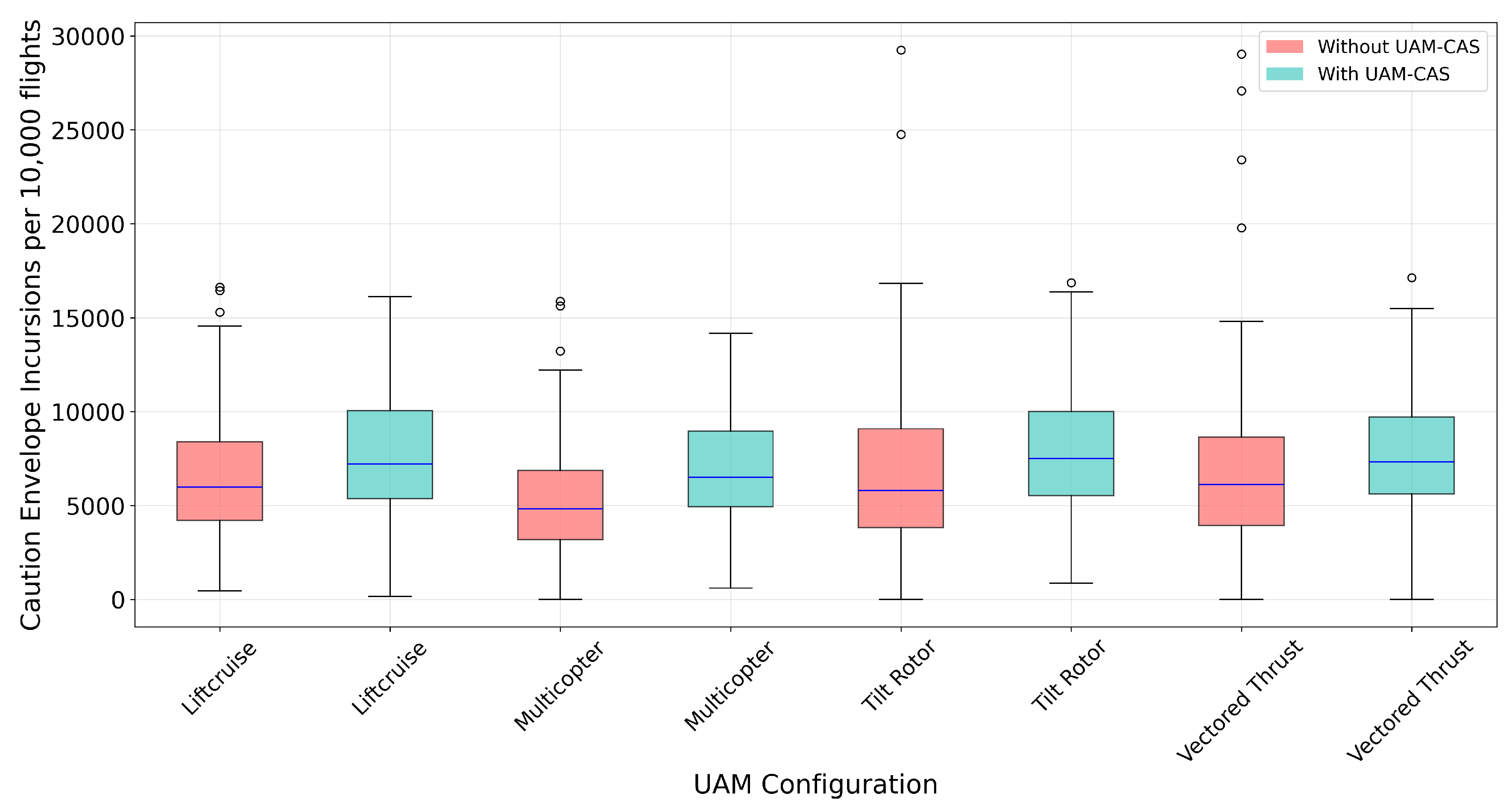

3.2. Envelope Incursion Rates

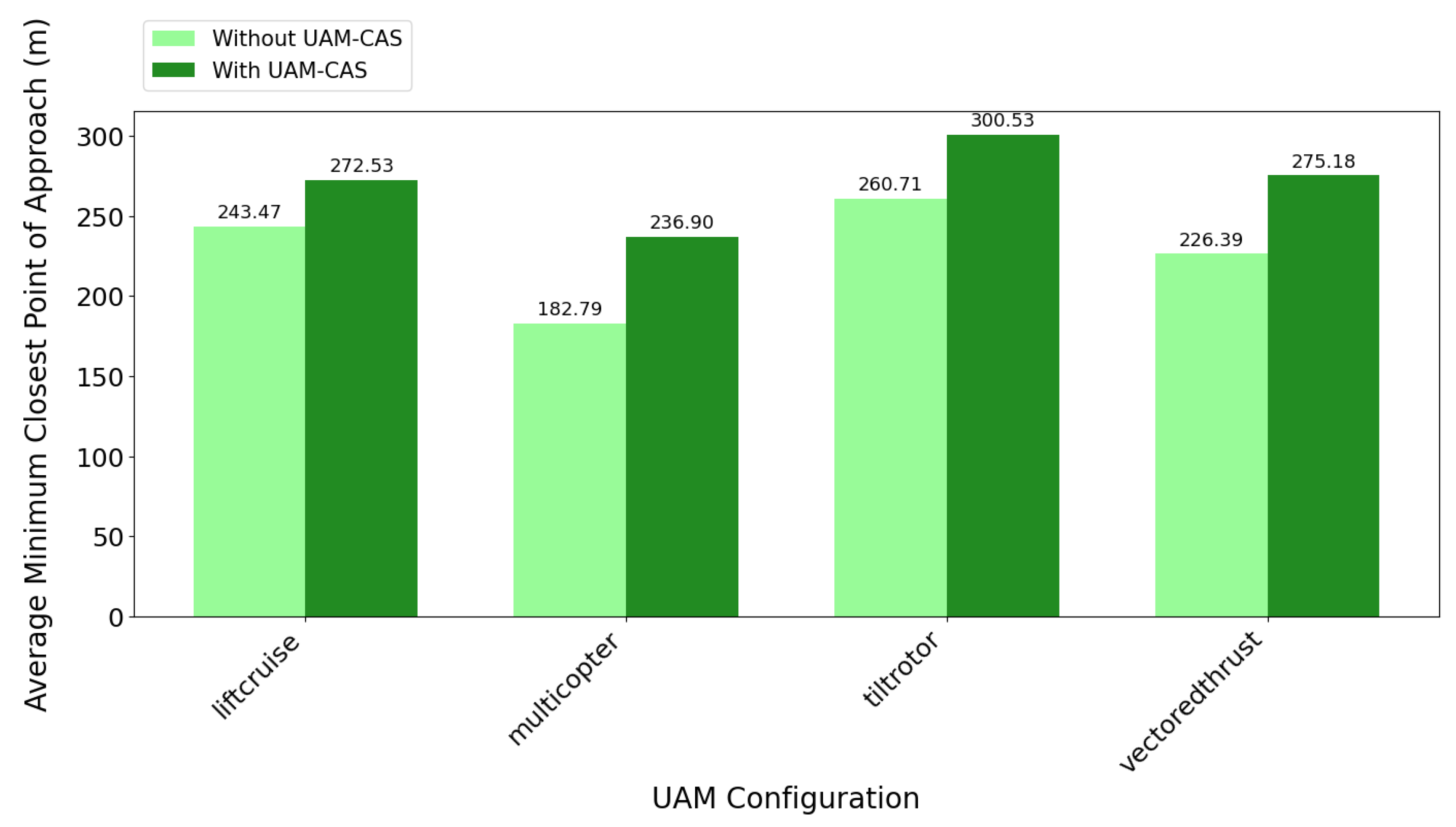

3.3. Closest Points of Approach

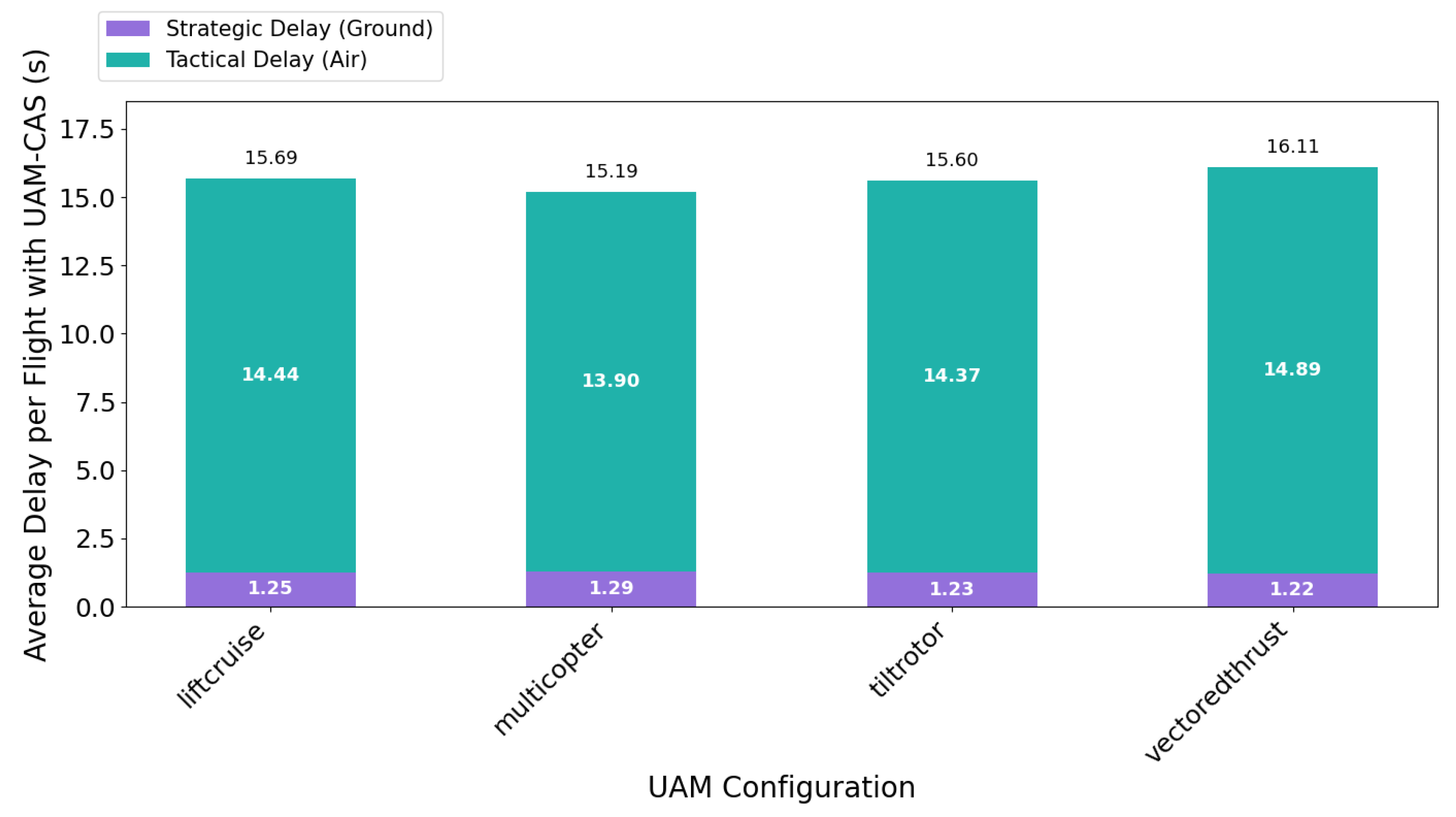

3.4. Delays

4. Conclusions

4.1. Key Outcomes

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Reuters. Electric planemaker Beta Technologies raises over $300 mln in new funding, 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/electric-planemaker-beta-technologies-raises-over-300-mln-new-funding-2024-10-31/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Archer Aviation. Archer Raises $300M From Leading Institutional Investors To Accelerate Hybrid Aircraft Platform Development As Defense Opportunities Look Stronger Than Expected, 2025. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250211879370/en/Archer-Raises-%24300M-From-Leading-Institutional-Investors-To-Accelerate-Hybrid-Aircraft-Platform-Development-As-Defense-Opportunities-Look-Stronger-Than-Expected (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Joby Aviation. Joby Aviation Announces Closing of $250 Million Investment, 2025. Available online: https://www.jobyaviation.com/news/joby-aviation-announces-closing-250-million-investment/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Joby Aviation. Joby Successfully Conducts First FAA Testing under TIA, Begins Final Phase of Certification Program, 2024. Available online: https://ir.jobyaviation.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/122/joby-successfully-conducts-first-faa-testing-under-tia (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Archer Aviation. Archer Applauds FAA’s Final Rules for Operating eVTOL Aircraft, 2024. Available online: https://investors.archer.com/news/news-details/2024/Archer-Applauds-FAAs-Final-Rules-for-Operating-eVTOL-Aircraft/default.aspx (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Rothfeld, R.; Fu, M.; Balać, M.; Antoniou, C. Potential Urban Air Mobility Travel Time Savings: An Exploratory Analysis of Munich, Paris, and San Francisco. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, M.F.; Stepanian, P.M.; Metz, I.C. Wildlife Strike Mitigation in AAM: Key Technology Gaps and Proposed Solutions. In Proceedings of the Vertical Flight Society (VFS) 81st Annual Forum & Technology Display, Vertical Flight Society, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, I.C.; Henshaw, C.; Harmon, L. Flying in the Strike Zone: Urban Air Mobility and Wildlife Strike Prevention. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2024, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Consulting LLP. UAM Vision Concept of Operations (ConOps) UAM Maturity Level (UML) 4. Concept of Operations Version 1.0, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 2020.

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Begier, M.J.; Miller, P.R.; Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L. Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States 1990–2023. Technical Report Serial Report Number 30, Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC, USA, 2024. In cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wildlife Services.

- Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Fernández-Juricic, E.; Devault, T.L.; Outward, R.J. Avian Responses to Aircraft in an Airport Environment. J. Wildl. Manag. 2019, 83, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Proposed Means of Compliance with the Special Condition VTOL. Public Consultation Document MOC SC-VTOL, European Union Aviation Safety Agency, Cologne, Germany, 2020. Issue: 1.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Guidelines for the Assessment of the Critical Area of an Unmanned Aircraft. Guidelines Final Issue 01, European Union Aviation Safety Agency, Cologne, Germany, 2024. Issue: 1.

- ICAO. Aerodromes, 8th ed.; Vol. I, ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeer, R.A. Increasing Trend of Damaging Bird Strikes with Aircraft Outside the Airport Boundary: Implications for Mitigation Measures. Human–Wildlife Interactions 2011, 5, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, I.; Armanini, S.F.; Metz, I.C. Evaluation of Collision Detection and Avoidance Methods for Urban Air Mobility through Simulation. CEAS Aeronautical Journal 2025, 16, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, L.M.; Peinecke, N. Detect and Avoid for Unmanned Aircraft in Very Low Level Airspace. In Automated Low-Altitude Air Delivery - Towards Autonomous Cargo Transportation with Drones; Dauer, J.C., Ed.; Research Topics in Aerospace, Springer, 2021; pp. 333–351. [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.M.; Ellerbroek, J. BlueSky ATC Simulator Project: An Open Data and Open Source Approach. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Research in Air Transportation (ICRAT), Philadelphia, PA, USA; 2016; pp. 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, I.C.; Ellerbroek, J.; Mühlhausen, T.; Kügler, D.; Hoekstra, J.M. Simulating the Risk of Bird Strikes. In Proceedings of the Seventh SESAR Innovation Days, Belgrade, Serbia., 28–30 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, I. Air Traffic Control Advisory System for the Prevention of Bird Strikes. Ph.d. thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Royal Netherlands Airforce (RNLAF). Data from Robin 3D MAX Radar at Leeuwarden Air Base, 2024. Personal communication with Hans van Gasteren. Data courtesy of the Royal Netherlands Airforce.

- Bruderer, B.; Boldt, A. Flight Characteristics of Birds: I. Radar Measurements of Speeds. Ibis 2001, 143, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI). KNMI Data Platform (KDP), 2025. Available online: https://www.knmi.nl/research/observations-data-technology/projects/knmi-data-platform (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- EASA. Study on the Societal Acceptance of Urban Air Mobility in Europe. Technical report, European Union Aviation Safety Agency, Cologne, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/uam-full-report.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Google Earth. Satellite imagery of Eindhoven. Map data: Airbus. Imagery date: 9 May 2022–newer. (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Panchal, I.; Metz, I.C.; Ribeiro, M.; Armanini, S.F. Urban Air Traffic Management for Collision Avoidance with Non-Cooperative Airspace Users. In Proceedings of the 33rd Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS 2022), Stockholm, Sweden; 2022; pp. 6801–6817. [Google Scholar]

- Volocopter GmbH. VoloCity Design Specifications, 2024. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/vnrac6vfvrab/3lVLdBP4Wmbv4e8hipNS1V/2adb898d09dbdd784183c26bd8bac960/2025_SpecSheet_VoloCit.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- EHang Holdings Limited. UAM-Passenger Autonomous Aerial Vehicle (AAV). Available online: https://www.ehang.com/ehangaav/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration. Pilots’ Role in Collision Avoidance. Advisory Circular AC 90-48D, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_90-48D.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Peinecke, N.; Limmer, L.; Volkert, A. Application of “Well Clear” to Small Drones. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/AIAA 37th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), London, UK; 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. Introduction to TCAS II Version 7.1. Technical Report HQ-111358, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Washington, D.C., 2011.

- Metz, I.C.; Giordano, M.; Ntampakis, D.; Moira, M.; Hamann, A.; Blijleven, R.; Ebert, J.J.; Montemaggiori, A. Impact of COVID-19 on aviation–wildlife strikes across Europe. Human–Wildlife Interactions 2022, 16, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.; Malouf, M.; Martin, W. The Impact of COVID-19 on Wildlife Strike Rates in the United States. Human–Wildlife Interactions 2022, 16, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altringer, L.; McKee, S.C.; Kougher, J.D.; Begier, M.J.; Shwiff, S.A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on wildlife–aircraft collisions at US airports. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 11602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, G.E.; Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L.; Kutschbach-Brohl, L. Fatal injuries to birds from collisions with aircraft reveal anti-predator behaviours. Ibis 2010, 152, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns Airport. CAPL Bird Watch Conditions. Presentation at the Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group (AAWHG) Forum, Brisbane, Australia, 22 October 2009, 2009. Available online: https://aawhg.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2009-Forum-capl_bird_watch_conditions_lamont.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Brix, J. Northern Territory Airports application of the IBSC Standards, 2013.

- Vaishnav, T.; Haywood, J.; Burns, K.C. Biogeographical patterns in the seasonality of bird collisions with aircraft. Ecological Solutions and Evidence 2024, 5, e12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Lima, S.L.; Fernández-Juricic, E. Effects of Vehicle Speed on Flight Initiation by Turkey Vultures: Implications for Bird–Vehicle Collisions. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e87944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Lima, S.L.; Fernández-Juricic, E. Speed kills: ineffective avian escape responses to oncoming vehicles. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 282, 20142188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.P. Map Projections: A Working Manual. Professional Paper 1395, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UAM | Horizontal | Vertical | Cruise | Non UAM-CAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Dimension (m) | Dimension (m) | Speed (knots) | Flight Time (s) |

| Multicopter | 12 | 2.3 | 48 | 280.67 |

| Liftcruise | 14 | 2.3 | 130 | 248.42 |

| Vectored Thrust | 14 | 2.3 | 134 | 247.85 |

| Tilt Rotor | 14 | 2.3 | 174 | 243.64 |

| Pair | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Multicopter vs Lift Cruise | 2.81 | 0.0937 |

| Multicopter vs Tilt Rotor | 6.50 | 0.0108 |

| Multicopter vs Vectored Thrust | 8.69 | 0.0032 |

| Lift Cruise vs Tilt Rotor | 1.12 | 0.2896 |

| Lift Cruise vs Vectored Thrust | 2.27 | 0.1315 |

| Tilt Rotor vs Vectored Thrust | 0.17 | 0.6806 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).