Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

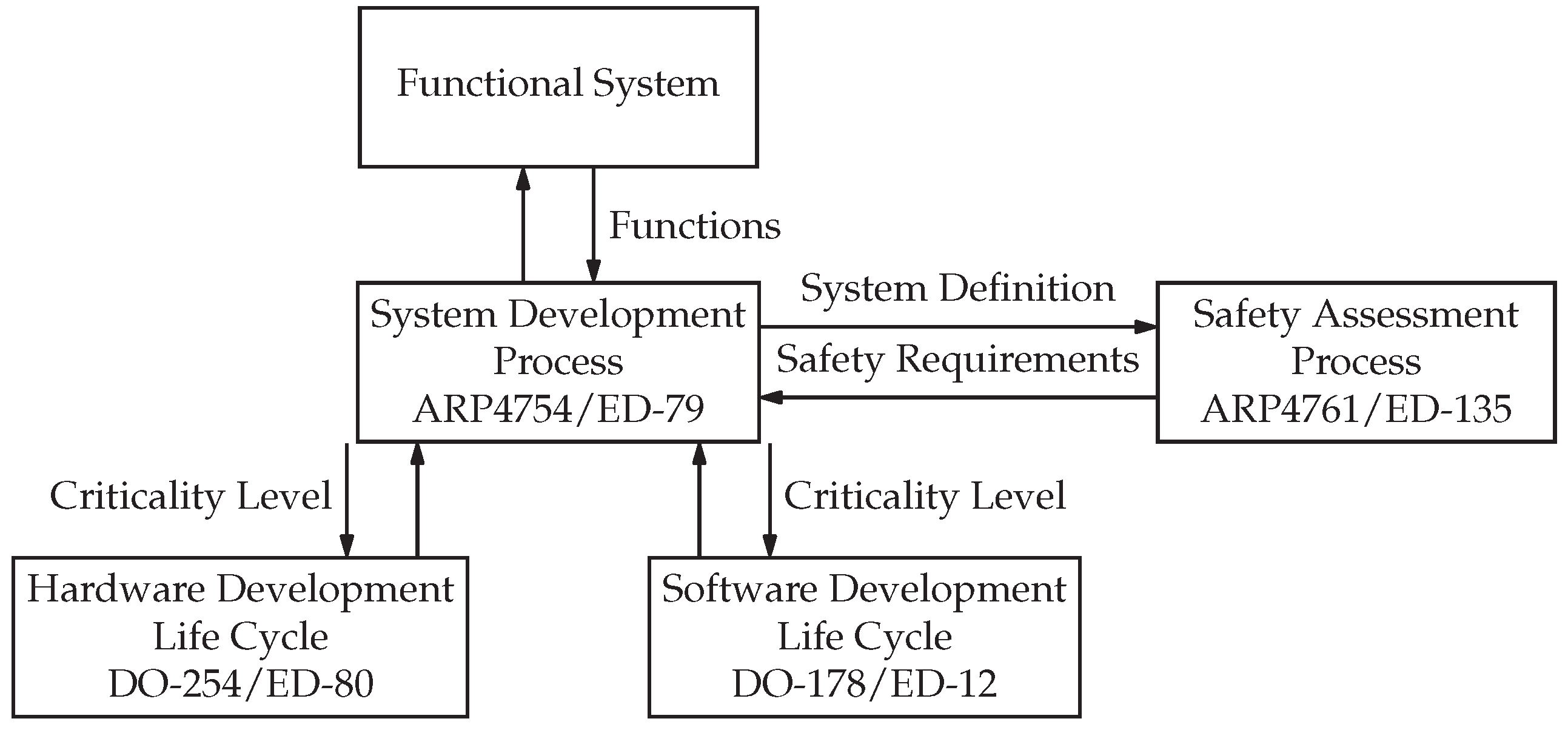

2. State of the Art

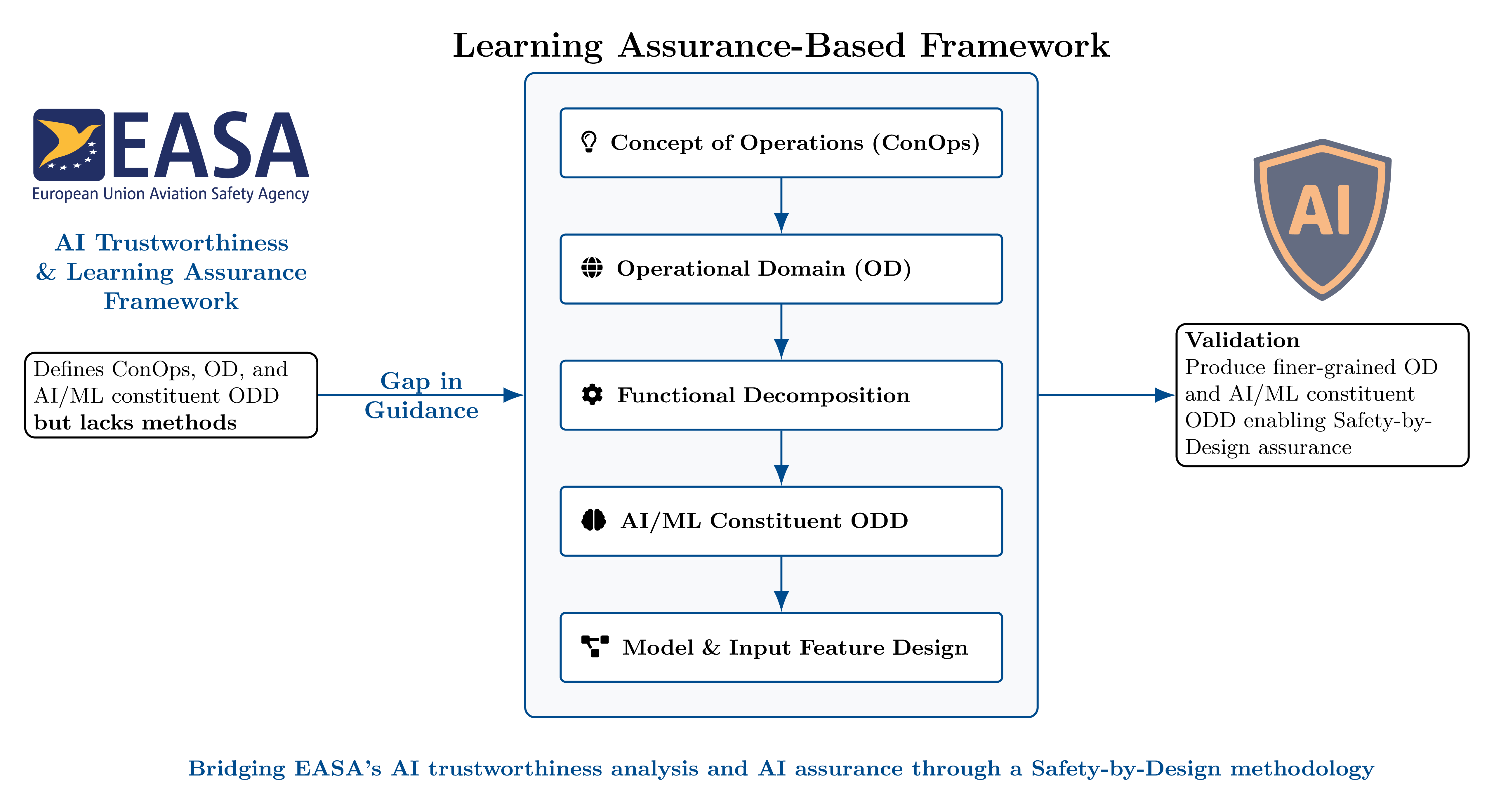

3. Methodology

3.1. Definition of a Concept of Operations

3.2. Definition of an Operational Domain

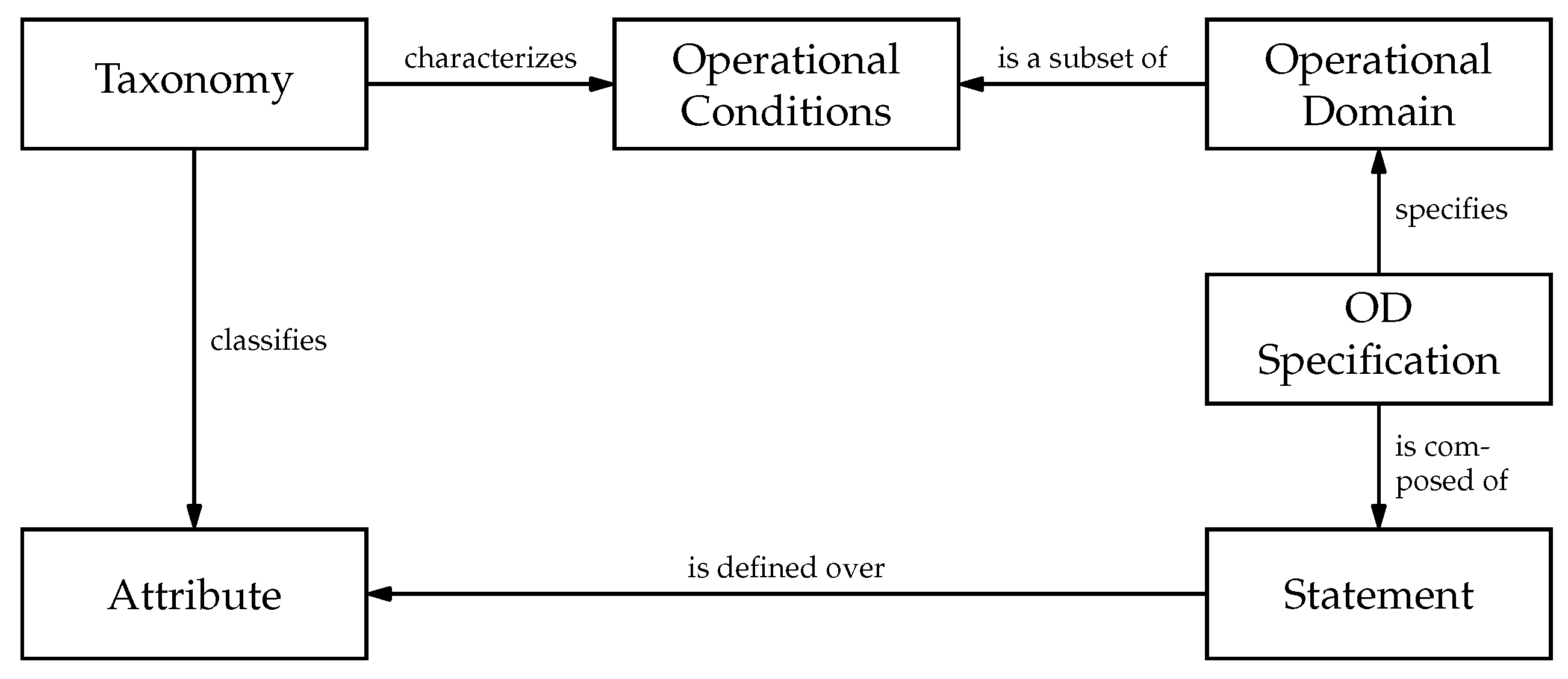

3.2.1. Operational Domain Taxonomy

3.2.2. Operational Domain Definition Language

3.2.3. OD Specification

3.3. Functional Decomposition of the AI-Based System

3.4. Definition of the AI/ML Constituent Operational Design Domain

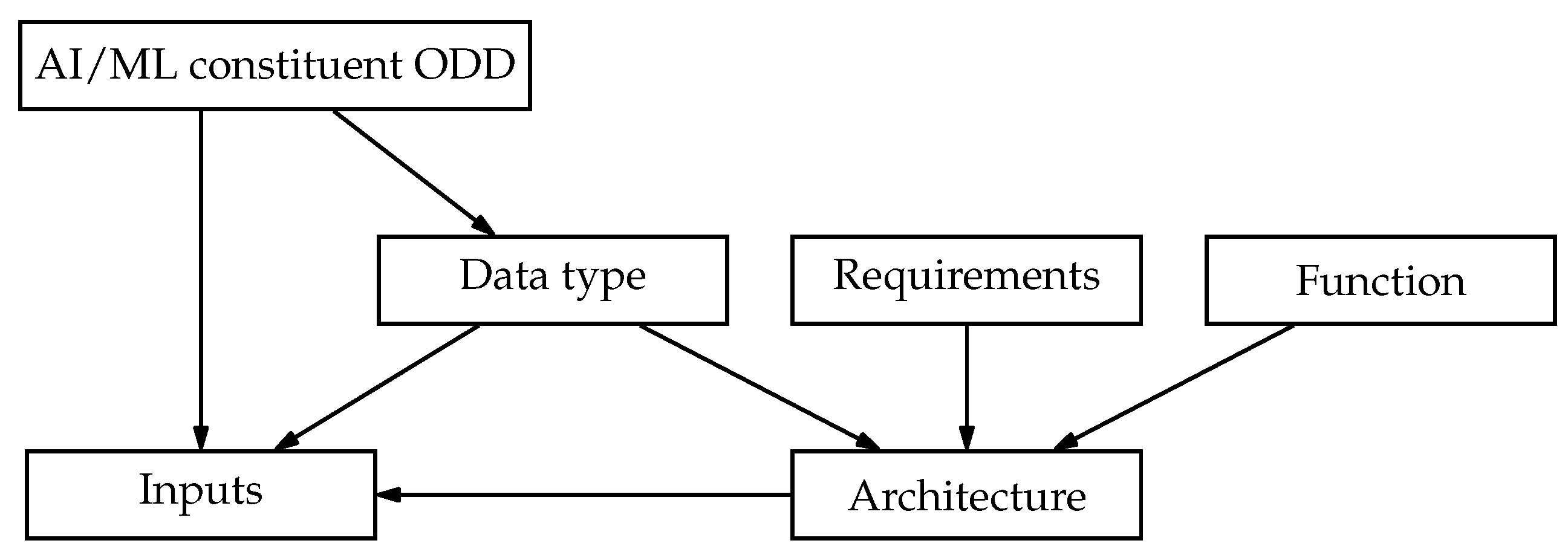

3.4.1. AI/ML Constituent ODD Taxonomy

3.4.2. AI/ML Constituent ODD Definition Language

3.4.3. AI/ML Constituent ODD Specification

3.4.4. AI/ML Constituent ODD Verification and Validation

3.5. Model Architecture and Input-Feature Selection

4. Results

4.1. Definition of a ConOps for pyCASX

4.2. Definition of an OD for pyCASX

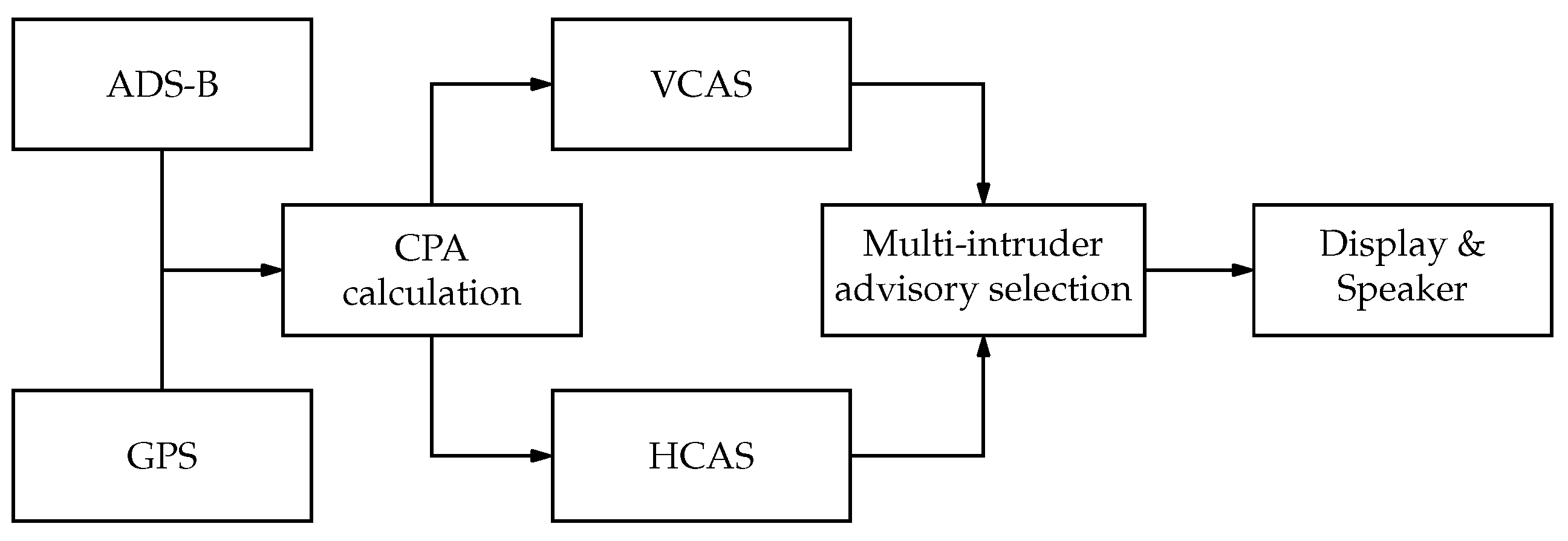

4.3. Functional Decomposition of pyCASX

4.4. Definition of an AI/ML Constituent ODD for VCAS and HCAS

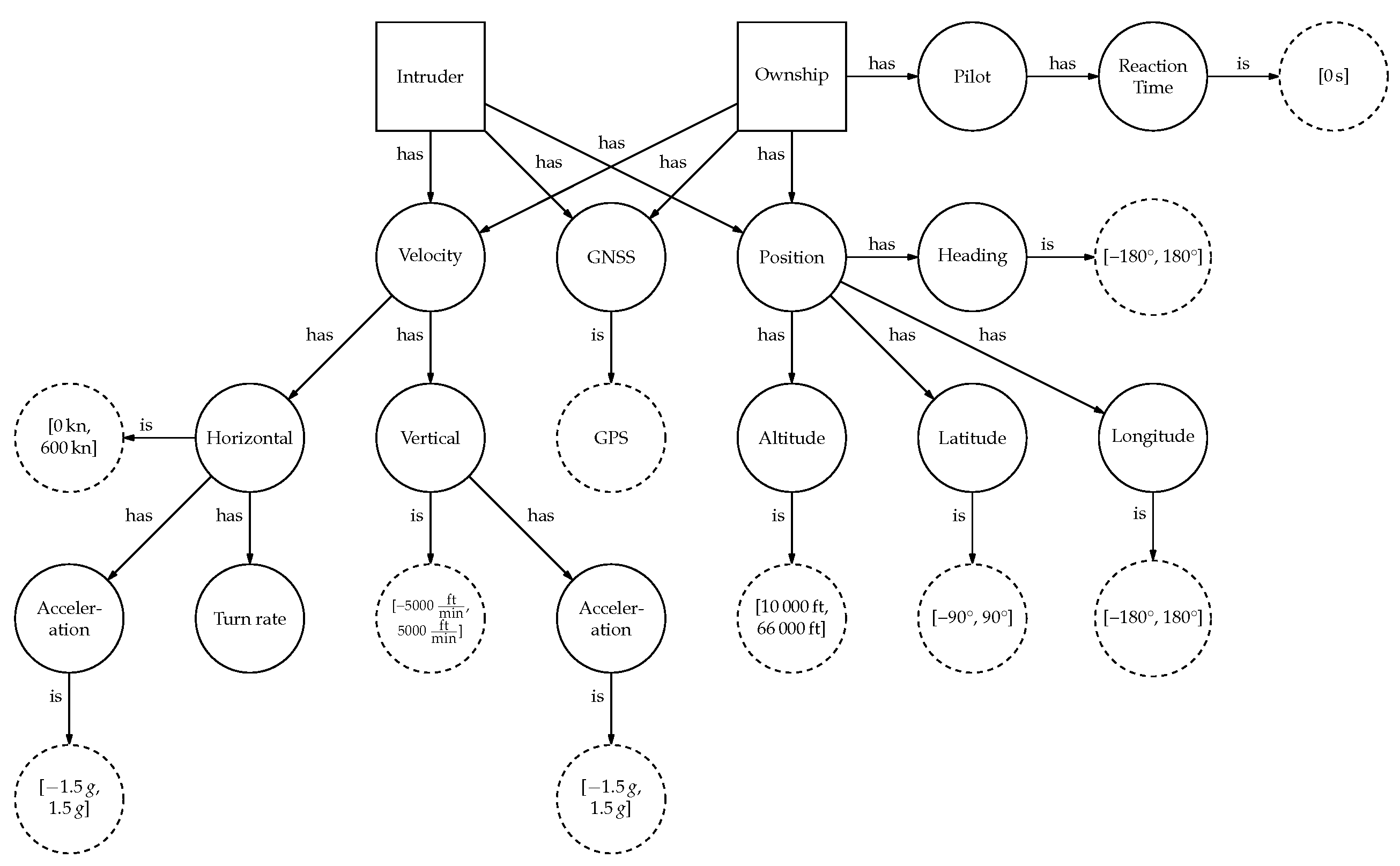

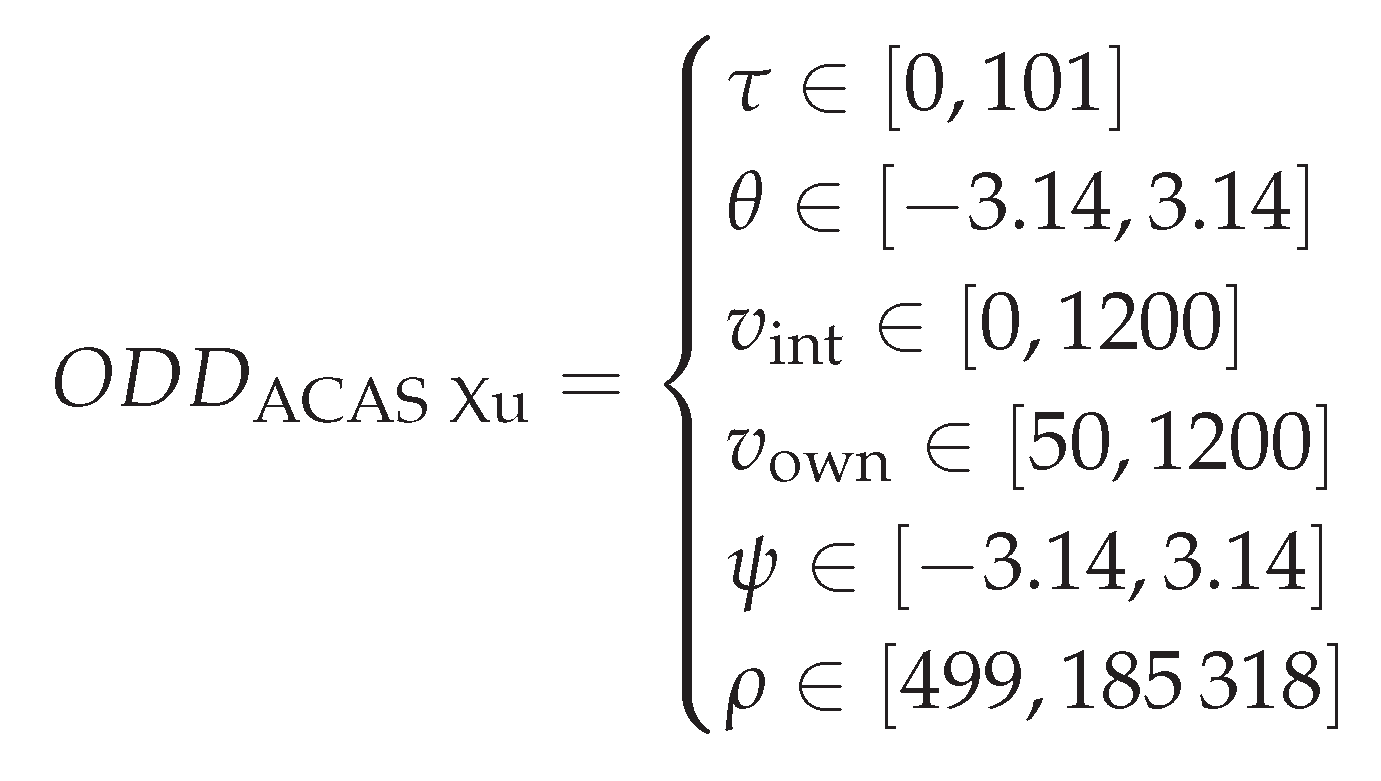

4.4.1. The AI/ML Constituent ODD for VCAS

4.4.2. The AI/ML Constituent ODD for HCAS

4.5. Framework Validation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACAS | Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIR | Aerospace Information Report |

| ARP | Aerospace Recommended Practice |

| ConOps | Concept of Operations |

| CPA | Closest Point of Approach |

| DO | Document |

| EASA | European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

| ED | EUROCAE Document |

| EUROCAE | European Organization for Civil Aviation Equipment |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HCAS | Horizontal Collision Avoidance System |

| IFR | Instrument Flight Rules |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NM | Nautical Mile |

| OD | Operational Domain |

| ODD | Operational Design Domain |

| SAE | SAE International |

| SysML | Systems Modeling Language |

| VCAS | Vertical Collision Avoidance System |

| VFR | Visual Flight Rules |

References

- S-18 Aircraft and Sys Dev and Safety Assessment Committee. Guidelines for Development of Civil Aircraft and Systems; 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTCA, Inc. Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification. techreport DO-178C, GlobalSpec, Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- RTCA, Inc. DO-200B - Standards for Processing Aeronautical Data. Technical report, GlobalSpec, Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- G-34 Artificial Intelligence in Aviation. Artificial Intelligence in Aeronautical Systems: Statement of Concerns; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). EASA Concept Paper: Guidance for Level 1 & 2 Machine Learning Applications. techreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), Postfach 10 12 53, 50452 Cologne, Germany, 2024.

- Kaakai, F.; Adibhatla, S.; Pai, G.; Escorihuela, E. Data-centric Operational Design Domain Characterization for Machine Learning-based Aeronautical Products. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security; Springer, 2023; pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Mamalet, F.; Jenn, E.; Flandin, G.; Delseny, H.; Gabreau, C.; Gauffriau, A.; Beaudouin, B.; Ponsolle, L.; Alecu, L.; Bonnin, H.; et al. White Paper Machine Learning in Certified Systems. Research report, IRT Saint Exupéry ; ANITI, 2021.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Artificial Intelligence Roadmap 2.0. techreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), Postfach 10 12 53, 50452 Cologne, Germany, 2023.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. The Agency. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/the-agency/the-agency (accessed on 2024-08-15).

- Durand, J.G.; Dubois, A.; Moss, R.J. Formal and Practical Elements for the Certification of Machine Learning Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/AIAA 42nd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC); 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S-18 Aircraft and Sys Dev and Safety Assessment Committee. Guidelines for Conducting the Safety Assessment Process on Civil Aircraft, Systems, and Equipment; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTCA, Inc.. Design Assurance Guidance for Airborne Electronic Hardware. techreport, GlobalSpec, Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Luettig, B.; Akhiat, Y.; Daw, Z. ML meets aerospace: challenges of certifying airborne AI. Frontiers in Aerospace Engineering 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Safety Assurance. Technical report, Federal Aviation Administration, 800 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20591, 2024.

- EASA and Daedalean. Concepts of Design Assurance for Neural Networks (CoDANN). resreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), 2020.

- EASA and Daedalean. Concepts of Design Assurance for Neural Networks (CoDANN) II with appendix B. resreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), 2024.

- MLEAP Consortium. EASA Research – Machine Learning Application Approval (MLEAP) Final Report. Technical Report 1, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), 2024.

- Bello, H.; Geißler, D.; Ray, L.; Müller-Divéky, S.; Müller, P.; Kittrell, S.; Liu, M.; Zhou, B.; Lukowicz, P. Towards certifiable AI in aviation: landscape, challenges, and opportunities, 2024.

- The British Standards Institution. PAS 1883:2020 - Operational Design Domain (ODD) taxonomy for an automated driving system (ADS) – Specification; BSI Standards Limited, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 34503: Road Vehicles – Test scenarios for automated driving systems – Specification for operational design domain; Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- On-Road Automated Driving (ORAD) Committee. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenseer, F.; Sarkar, S.; Shakeri, A. A Systematic Methodology for Specifying the Operational Design Domain of Automated Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW), Tsukuba, Japan; 2024; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, E.; Kimmel, S.C.; Chaka, M.; Hamilton, B.A.; et al. A Framework for Automated Driving System Testable Cases and Scenarios. Technical report, United States. Department of Transportation. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Hallerbach, S. Simulation-Based Testing of Cooperative and Automated Vehicles. phdthesis, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, 2020.

- PEGASUS RESEARCH PROJECT. The PEGASUS Method, 2019.

- Fjørtoft, K.E.; Rødseth, Ø.J. Using the operational envelope to make autonomous ships safer. In Proceedings of the The 30th European Safety and Reliability Conference, Venice, Italy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, S.; Chapdelaine, C.; Cappi, C.; Gardes, L.; Jenn, E.; Lefevre, B.; Soumarmon, T. Ensuring Dataset Quality for Machine Learning Certification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW); 2020; pp. 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, K. Operational world model ontology for automated driving systems–part 1: Road structure. Technical report, Waterloo Intelligent Systems Engineering (WISE) Lab, University of Waterloo, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, K. Operational world model ontology for automated driving systems–part 2: Road users, animals, other obstacles, and environmental conditions,”. Technical report, Waterloo Intelligent Systems Engineering (WISE) Lab, University of Waterloo, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mendiboure, L.; Benzagouta, M.L.; Gruyer, D.; Sylla, T.; Adedjouma, M.; Hedhli, A. Operational Design Domain for Automated Driving Systems: Taxonomy Definition and Application. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtes, M.; Westhofen, L.; Turner, L.R.; Lotto, K.; Schuldes, M.; Weber, H.; Wagener, N.; Neurohr, C.; Bollmann, M.; Körtke, F.; et al. 6-Layer Model for a Structured Description and Categorization of Urban Traffic and Environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59131–59147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, T.; Jameel, M.; Gerdes, I.; Hunger, R.; Bruder, C.; Hoemann, E.; Christensen, J.M.; Girija, A.A.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; et al. Towards an Operational Design Domain for Safe Human-AI Teaming in the Field of AI-Based Air Traffic Controller Operations. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA; 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berro, C.; Deligiannaki, F.; Stefani, T.; Christensen, J.M.; Gerdes, I.; Köster, F.; Hallerbach, S.; Raulf, A. Leveraging Large Language Models as an Interface to Conflict Resolution for Human-AI Alignment in Air Traffic Control. In Proceedings of the 2025 AIAA DATC/IEEE 44th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Montreal, Canada; 2025; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gabreau, C.; Gauffriau, A.; Grancey, F.D.; Ginestet, J.B.; Pagetti, C. Toward the certification of safety-related systems using ML techniques: the ACAS-Xu experience. In Proceedings of the 11th European Congress on Embedded Real Time Software and Systems (ERTS 2022), Toulouse, France; 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, T.; Anilkumar Girija, A.; Mut, R.; Hallerbach, S.; Krüger, T. From the Concept of Operations towards an Operational Design Domain for safe AI in Aviation. In Proceedings of the DLRK 2023, Stuttgart, Germany; 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, T.; Christensen, J.M.; Hoemann, E.; Anilkumar Girija, A.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; Hallerbach, S. Applying Model-Based System Engineering and DevOps on the Implementation of an AI-based Collision Avoidance System. In Proceedings of the 34th Congress of the International Councilof the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS), Florence, Italy; 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Anilkumar Girija, A.; Christensen, J.M.; Stefani, T.; Hoemann, E.; Durak, U.; Köster, F.; Hallerbach, S.; Krüger, T. Towards the Monitoring of Operational Design Domains Using Temporal Scene Analysis in the Realm of Artificial Intelligence in Aviation. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA; 09 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.M.; Anilkumar Girija, A.; Stefani, T.; Durak, U.; Hoemann, E.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; Hallerbach, S. Advancing the AI-Based Realization of ACAS X Towards Real-World Application. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 36th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Herdon, VA, USA; 10 2024; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torens, C.; Juenger, F.; Schirmer, S.; Schopferer, S.; Zhukov, D.; Dauer, J.C. Ensuring Safety of Machine Learning Components Using Operational Design Domain. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2023 Forum; 2023; p. 1124. [Google Scholar]

- Gariel, M.; Shimanuki, B.; Timpe, R.; Wilson, E. Framework for Certification of AI-Based Systems, 2023.

- Hasterok, C.; Stompe, J.; Pfrommer, J.; Usländer, T.; Ziehn, J.; Reiter, S.; Weber, M.; Riedel, T. PAISE®. Das Vorgehensmodell für KI-Engineering. Technical report, Fraunhofer-Institut für Optronik, Systemtechnik und Bildauswertung (IOSB), 2021.

- Zhang, R.; Albrecht, A.; Kausch, J.; Putzer, J.H.; Geipel, T.; Halady, P. DDE process: A requirements engineering approach for machine learning in automated driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 29th International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE); 2021; pp. 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.M.; Stefani, T.; Anilkumar Girija, A.; Hoemann, E.; Vogt, A.; Werbilo, V.; Durak, U.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; Hallerbach, S. Formulating an Engineering Framework for Future AI Certification in Aviation. Aerospace 2025, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappi, C.; Cohen, N.; Ducoffe, M.; Gabreau, C.; Gardes, L.; Gauffriau, A.; Ginestet, J.B.; Mamalet, F.; Mussot, V.; Pagetti, C.; et al. How to design a dataset compliant with an ML-based system ODD? In Proceedings of the 12th European Congress on Embedded Real Time Software and Systems (ERTS), Toulouse, France; 06 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhndorf, L.; Dmitriev, K.; Vasudevan, J.K.; Subedi, S.; Klarmann, N.; Holzapfel, F. Artificial Intelligence Verification Based on Operational Design Domain (ODD) Characterizations Utilizing Subset Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC); 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu/egan, A. WG-114 AI Standards in Aviation.

- International, S. G-34 Artificial Intelligence in Aviation. Available online: https://standardsworks.sae.org/standards-committees/g-34-artificial-intelligence-aviation (accessed on 2025-01-10).

- G-34 Artifical Intelligence In Aviation Committee. Process Standard for Development and Certification/Approval of Aeronautical Safety-Related Products Implementing AI. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/arp6983/ (accessed on 2024-11-16).

- Kaakai, F.; Machrouh, J. Guide to the Preparation of Operational Concept Documents (ANSI/AIAA G-043B-2018), 2025.

- Julian, K.D.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Guaranteeing Safety for Neural Network-Based Aircraft Collision Avoidance Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/AIAA 38th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA; 09 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.M.; Zaeske, W.; Beck, J.; Friedrich, S.; Stefani, T.; Girija, A.A.; Hoemann, E.; Durak, U.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; et al. Towards Certifiable AI in Aviation: A Framework for Neural Network Assurance Using Advanced Visualization and Safety Nets. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA; 09 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damour, M.; De Grancey, F.; Gabreau, C.; Gauffriau, A.; Ginestet, J.B.; Hervieu, A.; Huraux, T.; Pagetti, C.; Ponsolle, L.; Clavière, A. Towards Certification of a Reduced Footprint ACAS-Xu System: A Hybrid ML-Based Solution. In Proceedings of the Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security, Cham, Switzerland; 2021; pp. 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO/IEC/IEEE International Standard - Systems and software engineering – Life cycle processes – Requirements engineering. ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2018(E) 2018, pp. 1–104. [CrossRef]

- Verein zur Förderung der internationalen Standardisierung von Automatisierungs- und Meßsystemen (ASAM) e.V.. ASAM OpenODD Base Standard 1.0.0 Specification, 2025.

- Mercedes-Benz Research; Development North America, Inc. Introducing DRIVE PILOT: An Automated Driving System for the Highway. Available online: https://group.mercedes-benz.com/dokumente/innovation/sonstiges/2023-03-06-vssa-mercedes-benz-drive-pilot.pdf (accessed on 2024-11-07).

- Shakeri, A. Formalization of Operational Domain and Operational Design Domain for Automated Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 24th International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security Companion (QRS-C); 2024; pp. 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Zeller, M.; Schoenhaar, H.; Fraunhofer, C.D.; Kreutz, A. Approach for Argumenting Safety on Basis of an Operational Design Domain. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 3rd International Conference on AI Engineering – Software Engineering for AI (CAIN); 2024; pp. 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Adedjouma, M.; Botella, B.; Ibanez-Guzman, J.; Mantissa, K.; Proum, C.M.; Smaoui, A. Defining Operational Design Domain for Autonomous Systems: A Domain-Agnostic and Risk-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the SOSE 2024 - 19th Annual System of Systems Engineering Conference, Tacoma, WA, United States; 06 2024; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Nayeer, N.; Garcia, D.E.; Agrawal, A.; Liu, B. Identifying the Operational Design Domain for an Automated Driving System through Assessed Risk. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2020; pp. 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, N.; Corpino, S.; Fioriti, M.; Stesina, F.; et al. Functional analysis in systems engineering: Methodology and applications. In Systems engineering-practice and theory; InTech, 2012; pp. 71–96.

- S-18 Aircraft and Sys Dev and Safety Assessment Committee. Guidelines and Methods for Conducting the Safety Assessment Process on Civil Airborne Systems and Equipment; 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Witt, C.; Lake, L.; Guneshka, S.; Heinzemann, C.; Bonarens, F.; Feifel, P.; Funke, S. Using ontologies for dataset engineering in automotive AI applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE); 2022; pp. 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems, M.P. General Properties and Characteristics of Sensors. Available online: https://www.monolithicpower.com/en/learning/mpscholar/sensors/intro-to-sensors/general-properties-characteristics?srsltid=AfmBOooPonoNMaH1XZkUdaUvY50wL1EeRCkqxWEdjWBG8xttduX4OQ1V (accessed on 2024-12-10).

- Dodge, S.; Karam, L. Understanding how image quality affects deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 Eighth International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX); 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, X. Dataset Constrution through Ontology-Based Data Requirements Analysis. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, N.W.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z. Dataset Discovery and Exploration: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Davison, J.a.C.; Tostes, P.I.; Guerra Carneiro, C.A. Framework Architecture for AI/ML Data Management for Safety-Critical Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC); 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzberger, D.; Kühl, N.; Hirschl, S. Machine learning operations (mlops): Overview, definition, and architecture. IEEE access 2023, 11, 31866–31879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Intelligent Systems Laboratory. VerticalCAS Repository, 2020.

- Stanford Intelligent Systems Laboratory. HorizontalCAS Repository, 2020.

- Christensen, J.M.; Anilkumar Girija, A.; Stefani, T.; Durak, U.; Hoemann, E.; Köster, F.; Krüger, T.; Hallerbach, S. Advancing the AI-Based Realization of ACAS X Towards Real-World Application, 2024. [CrossRef]

- RTCA, Inc.. Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System X (ACAS X) (ACAS Xa and ACAS Xo). techreport DO-385, GlobalSpec, Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- RTCA, Inc.. Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System Xu (ACAS Xu). techreport DO-386, GlobalSpec, Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- FlightGear developers; contributors. FlightGear. Available online: https://www.flightgear.org/ (accessed on 2023-03-09).

- EUROCAE. Minimum Aviation System Performance Standard for Detect and Avoid (Traffic) in Class A-C airspaces - with Corrigendum 1. Technical report, EUROCAE, Saint-Denis, France, 2022.

- EUROCAE. ED-313. Technical report, EUROCAE, Saint-Denis, France, 2023.

- Safety, S.A. GPWS. Available online: https://skybrary.aero/gpws (accessed on 2024-12-28).

- Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand. ADS-B in New Zealand. Available online: https://www.nss.govt.nz/assets/nss/resources/2018-07-31-ADSB-FAQ-Document-V0.3.docx.pdf (accessed on 2025-01-10).

- Force, U.S.S. GPWS. Available online: https://www.spaceforce.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Article/2197765/global-positioning-system/ (accessed on 2024-12-29).

- Oceanic, N.; Administration, A. GPS Accuracy. Available online: https://www.gps.gov/systems/gps/performance/accuracy/ (accessed on 2024-12-29).

- Chryssanthacopoulos, J.P.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Collision avoidance system optimization with probabilistic pilot response models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2011 American Control Conference; 2011; pp. 2765–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, K.D.; Lopez, J.; Brush, J.S.; Owen, M.P.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Policy compression for aircraft collision avoidance systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/AIAA 35th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Sacramento, CA, USA; 09 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, K.D.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Owen, M.P. Deep Neural Network Compression for Aircraft Collision Avoidance Systems. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2019, 42, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grancey, F.; Gerchinovitz, S.; Alecu, L.; Bonnin, H.; Dalmau, J.; Delmas, K.; Mamalet, F. On the Feasibility of EASA Learning Assurance Objectives for Machine Learning Components. In Proceedings of the ERTS 2024, Toulouse, France, 06 2024; ERTS2024. Best paper award at ERTS 2024.

| Objective | Description |

|---|---|

| CO-01 | “The applicant should identify the list of end users that are intended to interact with the AI-based system, together with their roles, their responsibilities [...] and expected expertise [...].” |

| CO-02 | “For each end user, the applicant should identify which goals and associated high-level tasks are intended to be performed in interaction with the AI-based system.” |

| CO-04 | “The applicant should define and document the ConOps for the AI-based system, including the task allocation pattern between the end user(s) and the AI-based system. A focus should be put on the definition of the OD and on the capture of specific operational limitations and assumptions.” |

| CO-06 | “The applicant should perform a functional analysis of the system, as well as a functional decomposition and allocation down to the lowest level.” |

| DA-03 | “The applicant should define the set of parameters pertaining to the AI/ML constituent ODD, and trace them to the corresponding parameters pertaining to the OD when applicable.” |

| DA-06 | “The applicant should describe a preliminary AI/ML constituent architecture [...]” |

| LM-01 | “The applicant should describe the ML model architecture.” |

| Top-level attribute | Sub-attribute | Qualifier | Attribute | Attribute value | Unit |

| Scenery | Airspace | Include | Type | C | - |

| Airspace | Include | Flight Rule | IFR, VFR | - | |

| Airspace | Include | Altitude | [10000, 66000] | ||

| Airspace | Include | Latitude | [-90, 90] | ||

| Airspace | Include | Longitude | [-180, 180] | ||

| Airspace | Include | Route Type | Free Route Airspace | - | |

| Airspace | Exclude | Geography | Any | - | |

| Airspace | Exclude | Structures | Any | - | |

| Environment | Weather | Exclude | Adverse Conditions | Any | - |

| Connectivity | Include | Satellite Positioning | GPS | - | |

| Connectivity | Include | Communication Type | ADS-B | - | |

| Connectivity | Include | Communication Range | |||

| Dynamic Elements | Intruder | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - |

| Intruder | Include | Maximum Agent Density | 0.06 | ||

| Intruder | Include | Latitude | [-90, 90] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Longitude | [-180, 180] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Altitude | [10000, 66000] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Horizontal Airspeed | [0, 600] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Horizontal Acceleration | [-1.5, 1.5] | g | |

| Intruder | Include | Vertical Rate | [-5000, 5000] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration | [, ] | g | |

| Intruder | Include | Heading | [-180, 180] | ||

| Intruder | Include | Communication Type | ADS-B | - | |

| Ownship | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - | |

| Ownship | Include | Latitude | [-90, 90] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Longitude | [-180, 180] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Altitude | [10000, 66000] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Horizontal Airspeed | [0, 600] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Horizontal Acceleration | [-1.5, 1.5] | g | |

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate | [-5000, 5000] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration | [, ] | g | |

| Ownship | Include | Heading | [-180, 180] | ||

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Capability | |||

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration Capability | g | ||

| Ownship | Include | Turn Rate Capability | |||

| Ownship | Include | Turn Rate Acceleration Capability | |||

| Ownship | Include | Pilot Type | Pilot, Remote Pilot | - |

| Top-level attribute | Sub-attribute | Qualifier | Attribute | Attribute value | Unit | Distribution | Source |

| Scenery | Airspace | Include | Type | C | - | Constant | - |

| Airspace | Include | Flight Rule | IFR, VFR | - | - | - | |

| Airspace | Include | Route Type | Free Route Airspace | - | Constant | - | |

| Environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dynamic Elements | Intruder | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - | Constant | ADS-B |

| Intruder | Include | Vertical Rate | [-5000, 5000] | − | ADS-B | ||

| Intruder | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration | [, ] | g | - | - | |

| Intruder | Include | Relative Altitude to Ownship | [-10000, 10000] | − | - | ||

| Intruder | Include | Time until loss of separation | [0, 60] | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - | Constant | - | |

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate | [-5000, 5000] | − | GPS | ||

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration | [, ] | g | - | GPS | |

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Capability | ≥2000 | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Vertical Rate Acceleration Capability | g | - | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Pilot reaction time | [0] | - | |||

| Operating Parameters | Ownship | Include | GPS Inaccuracy | None | - | Constant | GPS |

| Intruder | Include | GPS Inaccuracy | None | - | Constant | GPS |

| Top-level attribute | Sub-attribute | Qualifier | Attribute | Attribute value | Unit | Distribution | Source |

| Scenery | Airspace | Include | Type | C | - | Constant | - |

| Airspace | Include | Flight Rule | IFR, VFR | - | - | - | |

| Airspace | Include | Route Type | Free Route Airspace | - | Constant | - | |

| Environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dynamic Elements | Intruder | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - | Constant | ADS-B |

| Intruder | Include | Horizontal Airspeed | [0, 600] | − | ADS-B | ||

| Intruder | Include | Horizontal Acceleration | [-1.5, 1.5] | g | - | - | |

| Intruder | Include | Relative Angle to Ownship | [-180, 180] | − | - | ||

| Intruder | Include | Time until loss of separation | [0, 60] | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Agent Type | Airplane | - | Constant | - | |

| Ownship | Include | Horizontal Airspeed | [0, 600] | − | GPS | ||

| Ownship | Include | Horizontal Acceleration | [-1.5, 1.5] | g | - | GPS | |

| Ownship | Include | Distance to Intruder | [0, 122000] | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Angle to Intruder | [-180, 180] | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Turn Rate Capability | ≥3 | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Turn Rate Acceleration Capability | ≥1 | − | - | ||

| Ownship | Include | Pilot reaction time | [0] | - | |||

| Operating Parameters | Ownship | Include | GPS Inaccuracy | None | - | Constant | GPS |

| Intruder | Include | GPS Inaccuracy | None | - | Constant | GPS |

| Objective | Requirement | Fulfilled |

| CO-01 | Identification of end users | Partially |

| CO-02 | Goals of the end users | Partially |

| High-level tasks of the end users | Completely | |

| CO-04 | Operational scenarios | Completely |

| Task allocation in the operational scenarios | Completely | |

| Capturing of operating conditions | Completely | |

| CO-06 | Functional decomposition of the system | Completely |

| Function allocation in the system architecture | Completely | |

| Classification of AI/ML items | Completely | |

| DA-03 | Set of parameters for the AI/ML constituent | Partially |

| Traced parameters to the OD | Completely |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).