1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming governance and industry, with tourism among the most digitalized sectors. AI systems—spanning forecasting, navigation, and personalization—improve efficiency and user experience, while GenAI, NLP, and IoT enhance sustainable destination management [

1,

2,

3]. Yet privacy leakage, algorithmic bias, and opaque accountability continue to undermine confidence, making trust the foundation of sustainable AI adoption. The coexistence of privacy concern and continuous reliance—the privacy paradox—reveals a tension between control and dependence [

4,

5].

Sustainable tourism must therefore reconcile innovation and accountability, consistent with SDGs 8, 12, and 17, which emphasize decent work, responsible production, and multi-actor partnership [

35,

36,

37]. Existing studies often analyze single stakeholders, leaving unresolved how governments, firms, and users co-construct trust within integrated governance systems.

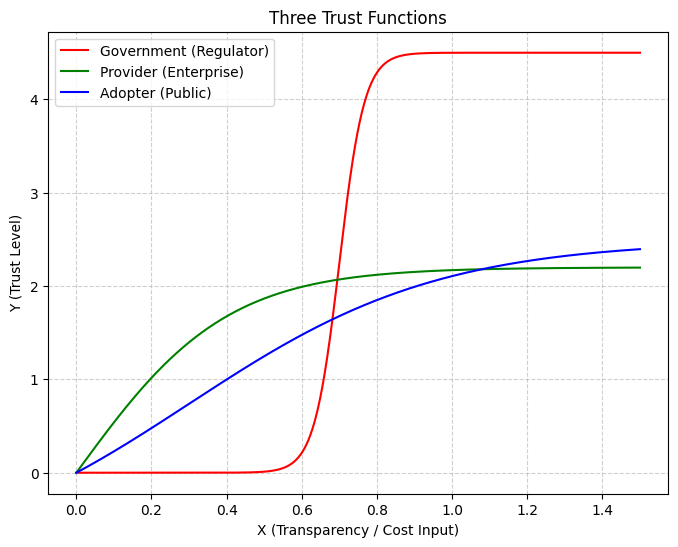

To address this gap, this study introduces the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF), which identifies three recurring trajectories:

Visibility thresholds in government transparency;

Efficiency balancing in enterprise operations;

Familiarity accumulation among users.

These trajectories depict bounded-rational satisficing behaviors, where actors seek “good-enough” rather than optimal outcomes [

21,

25].

Accordingly, this study asks: (1) How do trust–information-control relations differ across actors? (2) Can a unified heuristic capture their nonlinear convergence? (3) Does this convergence reflect a Satisficing Equilibrium (SE)?

Based on 1,590 valid survey responses, 35 semi-structured interviews, and robustness checks with an expanded 1,840-case dataset (Appendices D–E), the analysis employs Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), LOESS visualization, and Binary Logit with Average Marginal Effects (AME) to reveal nonlinear trust patterns and validate the stability of SE.

Contributions.

- ✧

Conceptual: Reframes multi-actor trust through the satisficing logic of TLHF, emphasizing heuristic rather than fitted modeling.

- ✧

Methodological: Combines nonparametric visualization with marginal-effect estimation for pattern verification.

- ✧

Practical: Highlights transparency visibility and low-friction usability as foundations for sustainable AI governance.

2. Literature Review

Artificial intelligence (AI) increasingly underpins smart tourism through forecasting, navigation, and personalized recommendation, transforming traveler behavior and destination management. GenAI, NLP, and IoT tools enhance efficiency and link digitalization with sustainability goals [

1,

2,

3]. Yet the critical challenge is not performance but trust—the foundation of ethical and sustainable AI governance. Data overcollection, algorithmic bias, and opaque accountability continue to erode confidence. Existing research typically treats these risks separately, seldom explaining how they interact. The privacy paradox—continued data sharing despite stated concerns—illustrates asymmetric feedback between control and reliance [

4,

5].

Trust in AI tourism is therefore co-produced among governments, firms, and users rather than an individual attitude. Sustainable governance depends on coordinated roles: governments ensure transparency, firms balance efficiency and responsibility, and users build confidence through stable, low-friction interaction. However, prior studies often isolate user psychology and assume linear trust growth, overlooking the interdependence and feedback across institutional layers.

To address this, the present study integrates all actors into a unified Information-Control-Level–Trust (ICL–T) framework for cross-actor comparison. Prior findings already indicate nonlinear trust trajectories:

- ■

Rapid acceleration once visibility thresholds are crossed (governments) [

6];

- ■

Diminishing returns after operational maturity (firms) [

7];

- ■

Gradual accumulation through repeated usability and familiarity (public) [

8,

9].

These processes form interlinked feedback loops within a governance ecosystem. Recent syntheses further show that performance, process, and purpose cues jointly sustain trust [

10]. Building on this insight, the study advances the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF)—a descriptive, nonparametric lens explaining how diverse trust paths converge into a mid–high Satisficing Equilibrium (SE), where adequacy outweighs maximal control.

Empirically, using 1,590 baseline surveys, 35 interviews, and robustness tests with an expanded 1,840-sample dataset, the study demonstrates how AI-enabled tourism systems sustain bounded-rational trust through the coordination of visibility, efficiency, and familiarity across actors.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Characteristics

Design.

A mixed-method design combined an international online survey and 35 semi-structured interviews to analyze AI-enabled tourism governance. The Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF) serves as a nonparametric lens visualizing convergence toward a mid–high Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) rather than estimating actor-specific effects. The Information Control Level (ICL) was modeled as a formative composite, for which internal-consistency indices (e.g., Cronbach’s α) are non-diagnostic [

38]. Following formative-measurement principles and privacy-calculus logic, visibility (Q5), concern (Q6), and accountability (Q7) jointly define information-control thresholds; thus α ≈ 0.29 is documentary rather than diagnostic [

38,

39] (see Appendix C.3).

- (1)

Survey.

The online survey (May–September 2025) was administered through Tencent Survey, a major data-collection platform operated by Tencent Holdings Ltd. (China). Respondents were required to log in via verified QQ, WeChat, or mainland China mobile accounts, ensuring single-entry authenticity and preventing duplicate responses. However, this design also limited participation by foreign users who lacked such credentials. The survey yielded 1,590 valid responses (84.7 %), and an expanded validation round produced N = 1,840 with stable patterns and consistent distributions. Little’s MCAR test (χ² = 12.4, p = 0.26) confirmed random missingness. Indicators were z-standardized under OECD/JRC guidelines, and bilingual items were harmonized via back-translation [

16,

17,

18]. The survey examined how Trust/Usage (Y) varies with ICL (X); Q5 (privacy / data-use notice) was dual-coded as “any-seen” (main) and “strict” (robustness) for replication.

Geographic distribution (expanded dataset, N = 1,840).

Respondents were concentrated in East and Southeast Asia—China (1,643; ≈ 84 %), Korea (253), Germany (21), United States (9), Thailand (7), Malaysia (6), and Japan (4)—with smaller subsamples from Canada, India, Egypt, Netherlands, Lebanon, and others (≤ 2 each). This Asia-anchored but globally inclusive profile enables cross-regional comparison while acknowledging limited cross-cultural validation at the national subsample level. Open-ended responses (N ≈ 50 from 15 countries) contextualize privacy sensitivity, authenticity, and trust formation, aligning with TLHF phases of visibility, efficiency, and familiarity (Appendix F).

- (2)

Interviews.

Thirty-five semi-structured interviews (15–60 min) involved institutional actors: 24 government officials (municipal / provincial tourism bureaus, data regulators) and 11 enterprise or technical staff (OTA platforms, smart-destination operators, AI service providers). Coding followed TLHF dimensions—transparency thresholds, efficiency–maintenance trade-offs, and user friction—derived from survey patterns; ≈ 20 % of transcripts were cross-checked for inter-coder reliability. Officials highlighted regulatory visibility and fiscal limits; firms emphasized maintenance stability; practitioners stressed usability and safety. These findings qualitatively validate TLHF’s three trajectories without substituting statistical inference [

14,

19].

Design rationale.

The qualitative strand traces institutional mechanisms (visibility, capacity, maintenance), while the survey captures user-side privacy and confidence. This two-track triangulation—mechanism tracing vs. distributional validation—supports the applicability of TLHF and SE across contexts (Appendix F).

- (3)

Key Variables.

- ■

Formative composite from Q5–Q7 (z-standardized; α ≈ 0.29, documentary not diagnostic) [

38,

39].

- ■

Trust / Usage (Y): From Q3–Q4 — usage count (0–5) and mean positive experience (efficiency, usability, personalization, labor saving), both normalized to [0, 1].

Respondents were mainly aged 18–29 (54 %) and traveled 1–2 times per year (55 %). Use rates were highest for voice navigation (57 %), AI customer service (52 %), and recommendation systems (50 %). About 72 % reported efficiency / usability gains; privacy sensitivity varied—consistent with bounded-rational satisficing. Nonlinearity was visualized via KDE / LOESS, and Logit + AME estimated marginal effects. Robustness on the expanded dataset (N = 1,840) confirmed stability (Appendix D).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Survey Sample (N = 1,590).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Survey Sample (N = 1,590).

| Variable |

Obs. |

Categories/Range |

Top Category (%) |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

| Age group |

1,590 |

4 |

18–29 (53.7%) |

— |

— |

| Travel frequency |

1,590 |

3 |

1–2 (55.1%) |

— |

— |

| AI customer service |

1,590 |

Binary |

Used/Agree |

0.52 |

0.50 |

| Voice navigation |

1,590 |

Binary |

Used/Agree |

0.57 |

0.49 |

| Personalized recommendation |

1,590 |

Binary |

Used/Agree |

0.50 |

0.50 |

| VR/AR features |

1,590 |

Binary |

Used/Agree |

0.22 |

0.42 |

| AI translator |

1,590 |

Binary |

Used/Agree |

0.23 |

0.42 |

| Perceived efficiency gain |

1,590 |

Binary |

Agree |

0.72 |

0.45 |

| Ease of use |

1,590 |

Binary |

Agree |

0.72 |

0.45 |

| Personalization helpful |

1,590 |

Binary |

Agree |

0.50 |

0.50 |

| Labor-cost reduction |

1,590 |

Binary |

Agree |

0.44 |

0.50 |

| No obvious improvement |

1,590 |

Binary |

— |

0.04 |

0.19 |

Two-Track Strategy and Ethics.

A continuous Trust / Usage score (Q3–Q4) supports KDE / LOESS, while binary Q8 informs Logit-AME probability changes. All procedures were anonymous and voluntary with electronic consent; no personally identifiable data were collected. Ethics approval was waived under institutional minimal-risk guidelines for anonymous, non-interventional social research.

3.2. Analytical Methods and Models

This study integrates descriptive statistics, nonparametric visualization, and a Binary Logit model with Average Marginal Effects (AME) to examine how the Information Control Level (ICL) shapes Trust/Usage (Y) and whether these relations converge toward a Satisficing Equilibrium (SE). Analyses were conducted in Python 3.11 (statsmodels, matplotlib, numpy), and replication scripts are archived in Appendices B and D. Nonparametric Visualization. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) and locally weighted regression (LOESS) were applied to reveal nonlinear associations without functional assumptions [

11,

12,

13]. Results show a modal cluster near X ≈ 2 and Y ≈ 0.5, indicating that users who noticed privacy disclosures (~70%) and experienced low friction (≤ 2/5) tend to “satisfice” once transparency and usability reach visible adequacy.

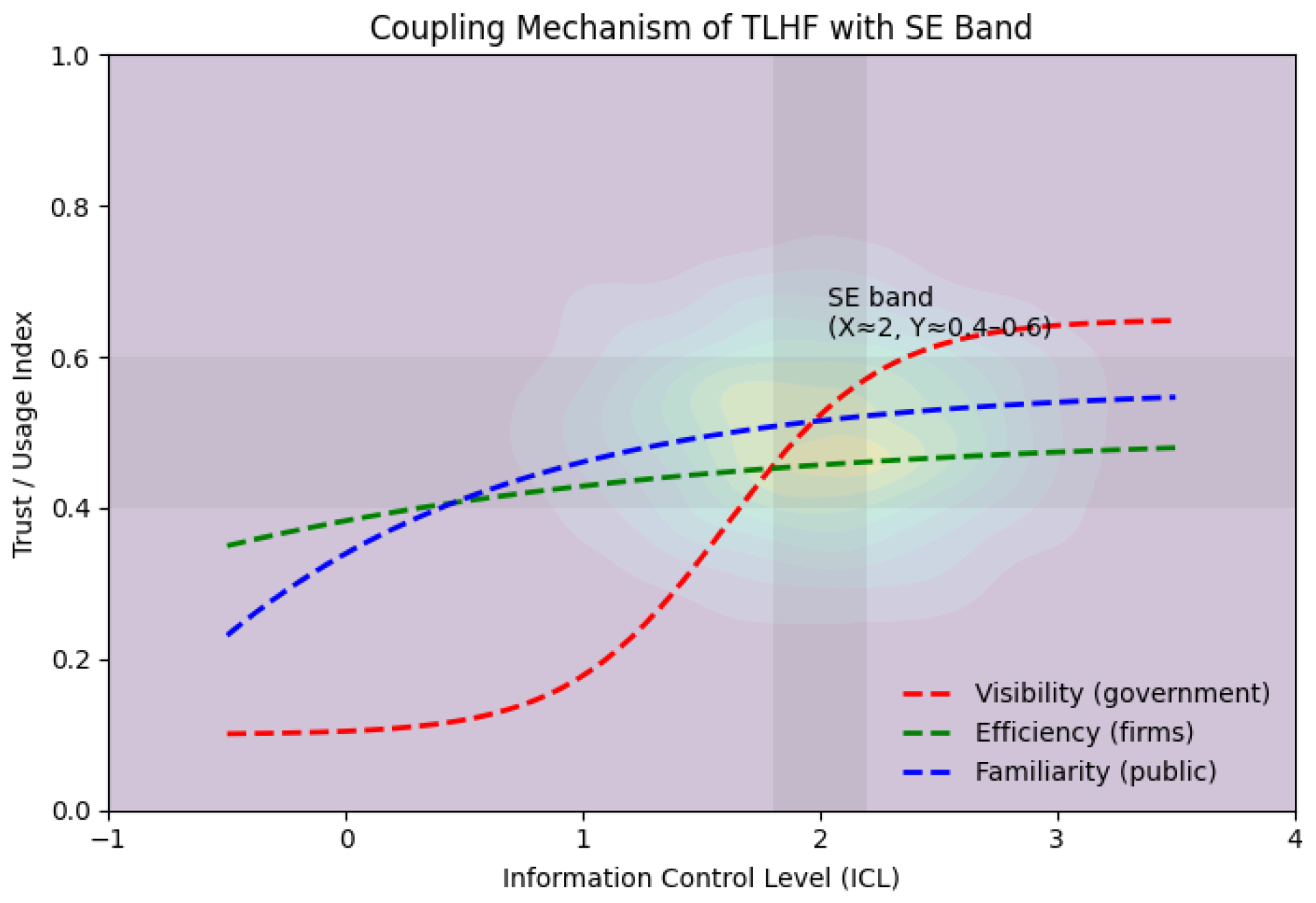

Within the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF), governments accelerate trust once transparency becomes visible, firms face diminishing returns as efficiency stabilizes, and users build confidence through familiar, low-friction interaction—together forming a bounded-rational convergence zone rather than an optimal equilibrium.

Figure 1.

Coupling Mechanism of TLHF with SE Band.

Figure 1.

Coupling Mechanism of TLHF with SE Band.

Note. The shaded area (X ≈ 2, Y ≈ 0.4–0.6) denotes the SE band where transparency and usability jointly sustain trust; trajectories represent visibility (government), efficiency (enterprise), and familiarity (public).

Binary Logit and Marginal Effects. The Positive Index shows a significant positive effect (p < 0.05; AME ≈ +3.2 pp), while AI Use and Privacy Concern are insignificant; Never-Used-AI is weakly negative (p ≈ 0.11). Model diagnostics confirm acceptable fit (AIC = 1,847.3; pseudo-R² = 0.18; AUC = 0.68), supporting bounded-rational variation.

Table 2.

Baseline Binary Logit Model with Coefficients and Average Marginal Effects (AME).

Table 2.

Baseline Binary Logit Model with Coefficients and Average Marginal Effects (AME).

| Variable |

Coefficient (β) |

Std.

Error |

p-

value |

AME (Δ Probability) |

Interpretation |

| Positive Index |

0.124 |

0.053 |

0.020 |

+0.032 |

Significant positive effect: higher positive experience increases probability of safe/ethical platform choice. |

AI Use Index

(0–5) |

−0.049 |

0.052 |

0.344 |

−0.019 |

Non-significant: additional AI functions do not linearly enhance trust. |

Privacy

Concern (0–3) |

0.071 |

0.062 |

0.249 |

+0.007 |

Weak, non-significant effect; concern alone does not reduce adoption. |

| Never-Used-AI (dummy) |

−0.301 |

0.191 |

0.115 |

−0.091 |

Marginally negative; long-term non-users show lower willingness to engage. |

| Constant |

−0.456 |

0.184 |

0.013 |

— |

Baseline probability for neutral users. |

Heuristic Summary.

Empirical patterns align with three expectations:

- (1)

Transparency acceleration—trust rises once visible openness crosses a threshold;

- (2)

Efficiency plateau—returns diminish as technical systems mature;

- (3)

Familiarity accumulation—trust deepens through repeated, low-friction interaction.

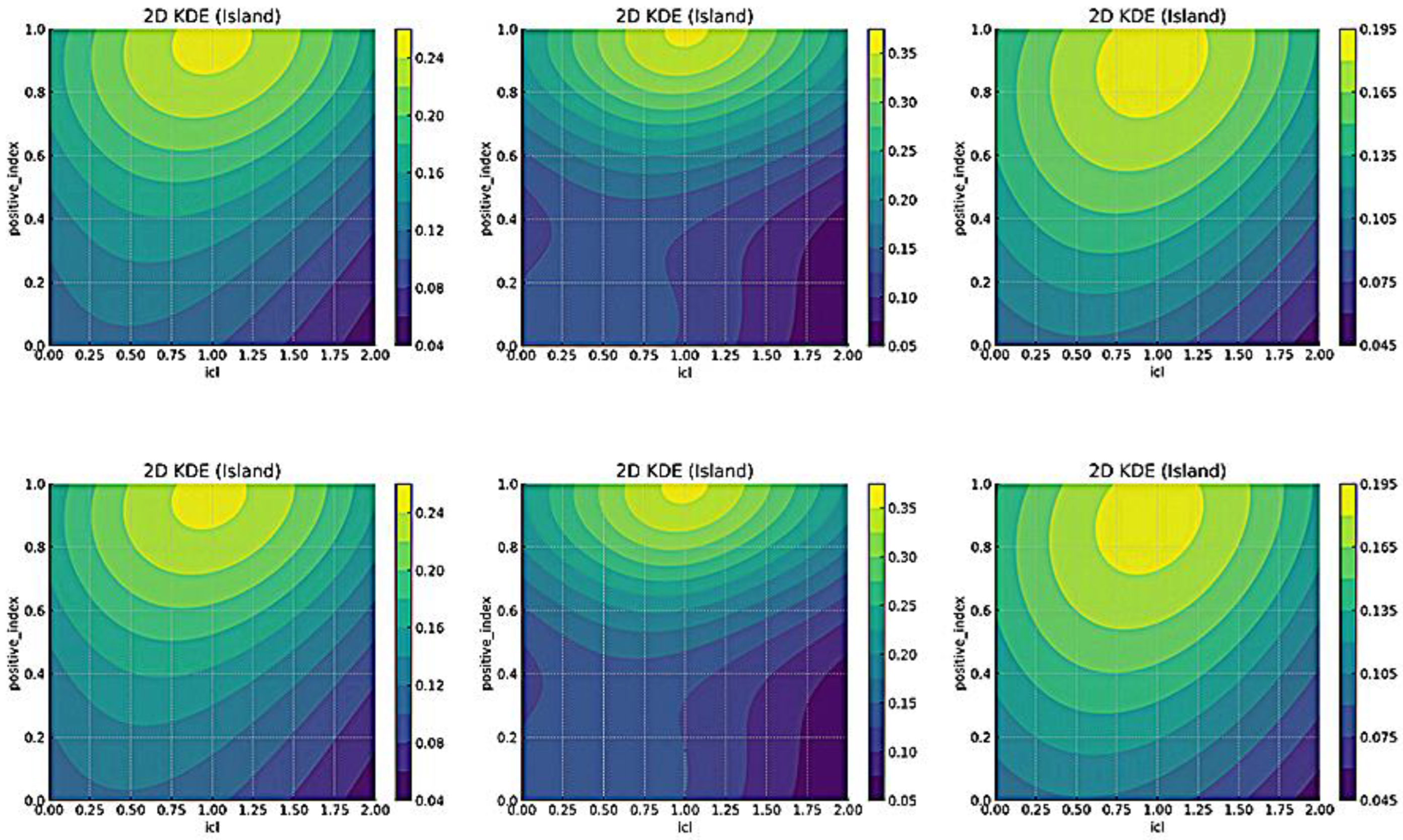

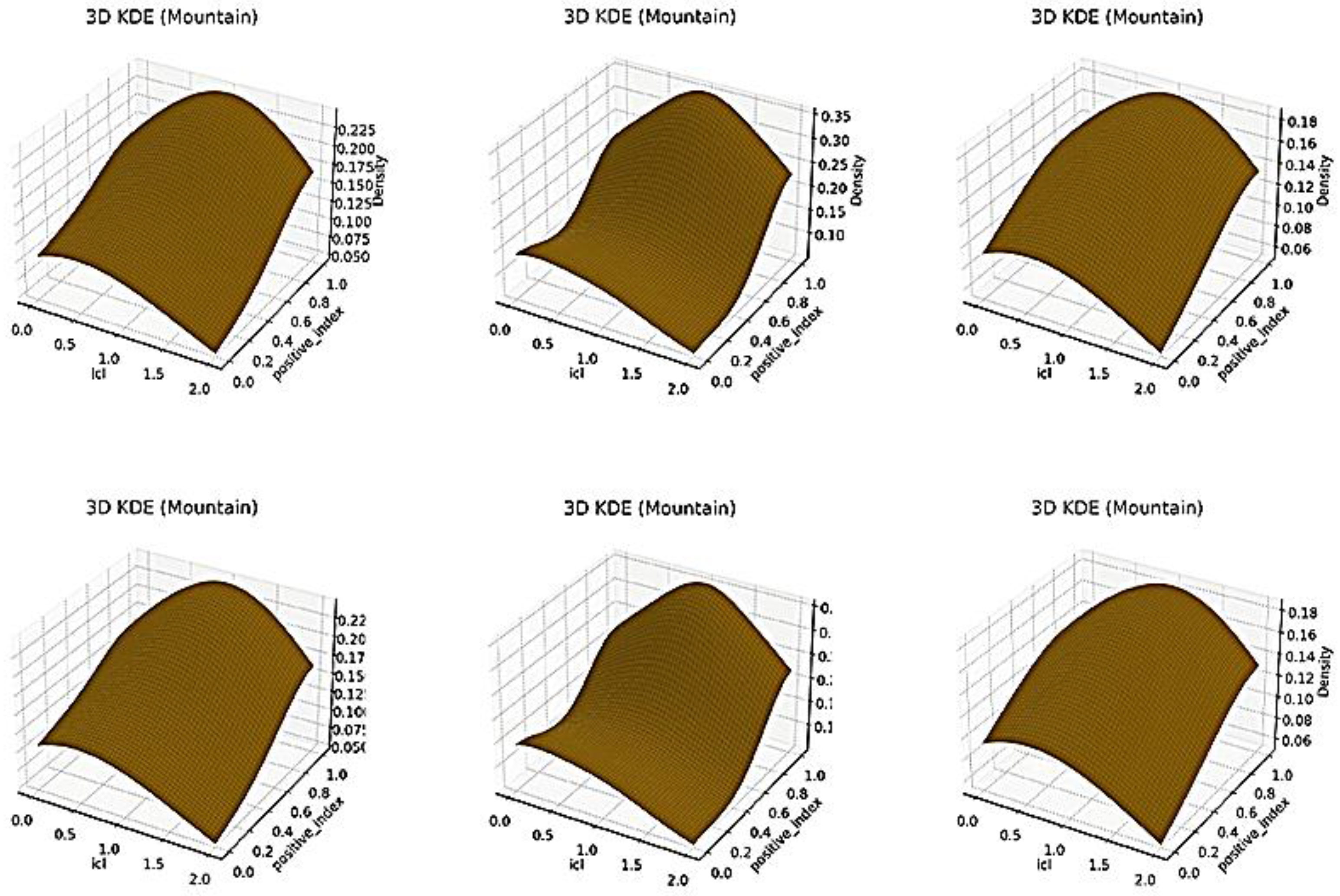

Density contours across Figures E1–E3 cluster around ICL ≈ 0.7–1.0 and Positive Index ≈ 0.8–0.9, confirming the SE band (X ≈ 2, Y ≈ 0.4–0.6) as a stable descriptive zone where further complexity adds little trust gain.

Summary.

Nonparametric and regression results jointly indicate a mid-high satisficing zone dominated by transparency and usability rather than technical sophistication—consistent with TLHF’s rise → threshold → plateau trajectory [

11,

12,

13,

15,

23,

24].

4. Results

4.1. Survey Patterns and Distributional Features

The survey reveals a persistent concern–action gap: only 39.1% read privacy notices, yet ≈70% expressed medium–high privacy concern, ≈90% demanded accountability, and 86.4% preferred well-rated platforms. This asymmetry illustrates the privacy paradox—valuing protection in principle while continuing data sharing when perceived risks are manageable [

4,

5].

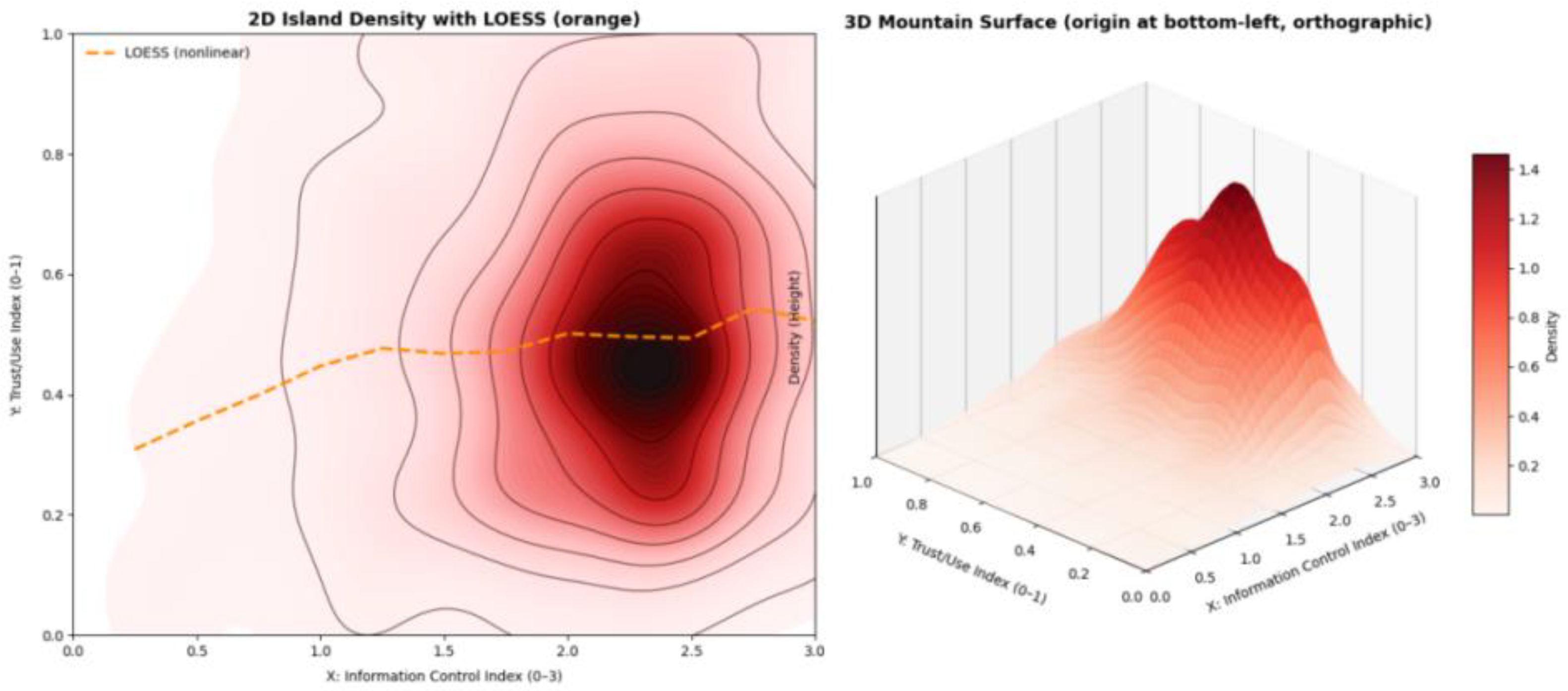

Nonparametric visualizations (

Figure 2 and Figure 3) exhibit three consistent features: (i) low trust at low ICL, (ii) a sharp rise once transparency becomes visible, and (iii) a plateau at higher ICL—a satisficing rather than linear trajectory [

11,

12,

13,

20,

22]. The 3-D KDE surface centers near X ≈ 2, Y ≈ 0.4–0.6, indicating a mid–high Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) band where users perceive visible safety cues (~70%) and low interaction friction (≤ 2/5).

Regression results are consistent: after visibility thresholds are crossed, Privacy Concern loses predictive power, whereas the Positive Index remains the dominant driver of safe-platform preference (p < 0.05; AME ≈ +3.2 pp). Usability and efficiency thus sustain equilibrium trust more effectively than abstract caution.

Robustness checks using stricter Q5 recoding and the expanded dataset (N = 1,840) reproduce the rise → threshold → plateau pattern. Overlay tests (Appendix E, Figure E13) recover the same SE band, confirming that the pattern reflects stable behavior rather than a smoothing artifact.

Cross-national open responses (N ≈ 50 from 15 countries) further corroborate these distributions (Appendix F, Tables F1–F4): respondents in developed economies (e.g., Germany, Korea) emphasized transparency and advertising fatigue; emerging contexts (e.g., Thailand, India, Malaysia) highlighted affordability and usability; and post-conflict regions (e.g., Lebanon) showed cautious satisficing under infrastructural limits. Together, these narratives reinforce SE as a bounded-rational adequacy pattern across diverse institutional and cultural settings.

Figure 2.

2-D Distribution (KDE + LOESS) of Trust Formation.(left).

Figure 2.

2-D Distribution (KDE + LOESS) of Trust Formation.(left).

Figure 3. 3-D Kernel Surface Highlighting the Mid–High Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) Band.(right). Note.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 jointly depict 2-D KDE/LOESS and the 3-D surface of trust; once transparency is visible (X≈2), trust stabilizes near Y≈0.5 (SE band). Visuals are descriptive/heuristic; robustness across bandwidths/samples in Appendix E.

4.2. Integrated Findings (Mechanism–Data Alignment)

This section aligns the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF) with observed trust distributions and platform-choice intentions (Q8), integrating quantitative and qualitative evidence.

① Choice Intention and Acceptance. Using Q8 (1 = Yes, 0 otherwise) as the dependent variable, Binary Logit with AME yields consistent effects across datasets. The Positive Index has a significant positive impact (p < 0.05; AME ≈ +3.2 pp), confirming that visible usability and efficiency increase safe-platform preference. The AI Use Index and Privacy Concern become non-significant once transparency is visible, while Never-Used-AI is weakly negative—indicating lower readiness among non-users. Results remain robust in the expanded dataset (N = 1,840) and statistically equivalent under TOST replication tests (Appendix D3–D4).

② Mechanism–Data Alignment. KDE and LOESS consistently show low trust at minimal ICL, sharp gains with visible transparency, and a plateau near X ≈ 2, Y ≈ 0.4–0.6—the mid-high SE band. Interpreted via TLHF, governments trigger threshold acceleration, firms face diminishing returns once efficiency stabilizes, and users build confidence through repeated low-friction interaction. Robustness tests—including alternative Q5 codings, ±25% bandwidth shifts, and cross-sample replication—reproduce this SE band (Appendices D3–D5; E1–E12). Qualitative interviews (A1–A35) and cross-national open responses (Appendix F, Tables F1–F4) corroborate these trajectories, linking transparency thresholds, maintenance-centric efficiency, and familiarity-based stabilization.

③ Robustness Visualization. Across

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, KDE and LOESS robustness tests exhibit stable peaks around X ≈ 2 and Y ≈ 0.5, confirming that the SE zone is both empirically reproducible and conceptually coherent—not a visualization artifact. Appendix E retains Figure E13 as a consolidated overlay for clarity.

Figure 4.

2-D Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) Robustness Across Bandwidths and Samples.

Figure 4.

2-D Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) Robustness Across Bandwidths and Samples.

Note. Rows represent datasets (top = baseline N = 1,590; bottom = expanded N = 1,840), and columns show bandwidths (−25%, baseline, +25%). Consistent density peaks near X ≈ 2 and Y ≈ 0.5 verify reproducibility of the SE band under different smoothing levels.

Figure 5.

3-D LOESS Surface Robustness Across Bandwidths and Samples. Note. 4. LOESS surfaces display persistent ridges near X ≈ 2 and Y ≈ 0.5, indicating stable satisficing behavior across bandwidths and samples. Contours mirror TLHF’s rise–threshold–plateau logic.

Figure 5.

3-D LOESS Surface Robustness Across Bandwidths and Samples. Note. 4. LOESS surfaces display persistent ridges near X ≈ 2 and Y ≈ 0.5, indicating stable satisficing behavior across bandwidths and samples. Contours mirror TLHF’s rise–threshold–plateau logic.

Synthesis.

Across all analyses, transparency and usability consistently anchor trust, while additional complexity yields diminishing returns. This bounded-rational trajectory—early rise, threshold acceleration, and plateau—is reproduced across quantitative and qualitative evidence (Appendix E13; Appendix F), demonstrating the integrative validity of TLHF and the stability of the SE band.

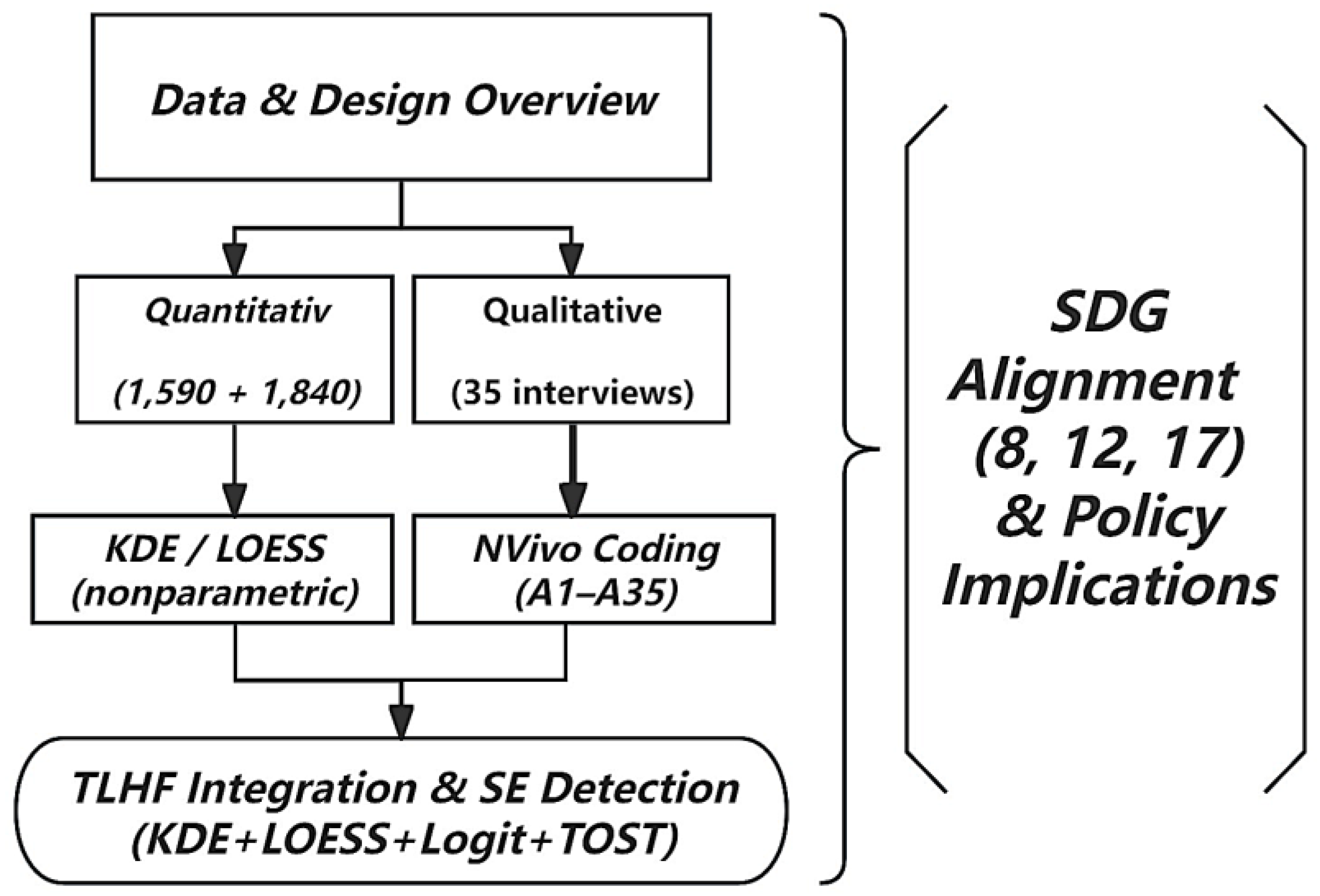

Figure 6.

Integrated Analytical Workflow for TLHF and Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) Detection.

Figure 6.

Integrated Analytical Workflow for TLHF and Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) Detection.

Note. The workflow links data collection (survey + interviews) with nonparametric visualization (KDE + LOESS), inference (Logit + TOST), and SDG-oriented interpretation (SDGs 8, 12, 17), summarizing the analytical pipeline connecting

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2 with

Figure 2, Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Empirical Integration

Findings show that trust and usage stabilize within a mid–high Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) band rather than increasing indefinitely with Information Control Level (ICL). Users pursue “good-enough” adequacy between efficiency, safety, and effort—reflecting bounded rationality rather than contradiction. Even under privacy concerns, once compliance cues become visibly sufficient, adoption continues, illustrating a bounded-rational privacy paradox. Beyond this threshold, further regulation or feature expansion yields only marginal gains, forming the plateau typical of satisficing behavior.

Within the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF), three adaptive trajectories explain this dynamic:

Governments experience accelerated trust once transparency becomes visible;

Firms face diminishing returns after operational stability is achieved;

Users consolidate confidence through habitual, low-friction interaction.

Interview evidence from southeastern China (A1–A35) and extended international responses (Appendix F) reinforce this mechanism: transparency precedes expansion, maintenance outweighs escalation, and usability sustains continuity. Robustness tests confirm these findings: TOST equivalence analyses show that over 80 % of key coefficients remain stable within ±2 percentage points across samples (N = 1,590 and 1,840; Appendix D4), and KDE overlay visualizations (Figure E13) display nearly identical density contours—verifying that the mid-high SE band is replicable rather than sample-dependent.

Together, these interactions define SE as a behavioral stability corridor integrating policy, enterprise, and public feedback within one ICL–Trust plane. SE therefore captures adaptive efficiency consistent with SDGs 8, 12, and 17 [

6,

21,

25,

35,

36,

37].

Theoretical Contributions.

This study reframes satisficing as a multi-actor equilibrium rather than a psychological compromise. It contributes by (1) unifying government, firm, and public trust logics under a descriptive heuristic; (2) demonstrating nonparametric identification of nonlinear convergence without causal assumptions; and (3) empirically grounding TLHF through 1,590 valid surveys and 35 institutional interviews. These results extend bounded-rationality theory toward sustainability-oriented digital governance, emphasizing visibility, adequacy, and restraint as durable foundations of confidence.

5.2. Practical Implications

Empirical evidence clarifies that the concern–action gap stems from rational satisficing rather than inconsistency. Once transparency and usability are visible, users rely on low-effort cues—ratings, certifications, predictable interfaces—over dense privacy statements whose cognitive cost exceeds perceived benefit. Consequently, Privacy Concern loses predictive power, while the Positive Index remains the strongest determinant of safe-platform preference (AME ≈ +3.2 pp; p < 0.05).

Governance should therefore make trust visible through standardized disclosure, interoperable oversight, and transparent breach reporting—transferring assurance from user cognition to institutional signaling. TLHF and SE together show that visible sufficiency and usability sustain confidence more effectively than over-regulation or technical sophistication. Sustainable trust arises when institutional thresholds match user expectations, aligning with SDGs 8, 12, and 17 [

35,

36,

37].

Across actors, a shared satisficing logic prevails:

Governments maintain credibility through phased, auditable rollouts;

Firms sustain reliability via privacy-by-design and consistent maintenance;

Users respond to stable, predictable experience rather than abstract guarantees.

Cross-national evidence further supports this pattern. Participants from developed economies (e.g., Germany, Korea) emphasized data-use visibility and advertising fatigue, while respondents from emerging contexts (e.g., Thailand, India, Malaysia) valued affordability and usability over perfection. Participants from regions with infrastructural fragility (e.g., Lebanon) stressed that visible reliability fosters trust even amid disruption.

In practice, visible adequacy—not maximal control—balances efficiency, cost, and confidence. Policymakers can operationalize SE as a monitoring dashboard linking transparency thresholds, usability friction, and trust stability, thus preventing governance fatigue and maintaining equilibrium in AI-enabled tourism ecosystems.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Sustainable Implications (SDGs 8, 12, and 17)

The Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) framework shows how bounded rationality and visible adequacy sustain digital transformation across institutional and cultural settings. Once transparency and usability become visible, trust stabilizes—anchored in clarity rather than compliance. SE thus maintains governance within a resilient corridor where adequacy outweighs optimization.

Cross-national evidence—from China, Korea, Germany, India, Malaysia, and other contexts—confirms that satisficing behavior emerges universally once safety cues and predictable interaction are visible. This extends the Three-Line Heuristic Framework (TLHF) from national to global governance, linking user confidence with institutional coordination.

SE aligns directly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- ⮚

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Inclusive Growth): Gradual, auditable AI deployment supports inclusive employment by shifting human roles toward oversight and ethical supervision.

- ⮚

SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production): Satisficing discourages redundant upgrades and excessive data extraction; privacy-by-design and usability-focused systems reduce digital and cognitive waste.

- ⮚

SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals): Multi-actor trust partnerships—via transparency signals, efficiency thresholds, and familiarity feedback—turn digital ecosystems into adaptive co-governance networks.

Together these dimensions position SE as a diagnostic lens for sustainable digital trust, emphasizing moderation, clarity, and accountability.

6.2. Summary and Outlook

SE and TLHF jointly redefine sustainable AI governance as moderation in action—trust that stabilizes through adequacy, not excess. Transparency, usability, and restraint form the durable foundation of multi-actor confidence, aligning bounded rationality with systemic resilience. Embedding SE metrics—transparency thresholds, usability indicators, and trust-stability indices—into policy dashboards enables early detection of governance fatigue and guides adaptive regulation.

Limitations and Future Directions.

Although the survey covered participants from 15 countries and regions, the dataset remains Asia-anchored, with China contributing about 84% of responses and smaller subsamples from Korea, Germany, and other countries. This composition primarily reflects the survey’s data-collection infrastructure: the questionnaire was distributed via Tencent Survey, which requires QQ, WeChat, or mainland China mobile authentication. This design ensured single-response validity and data authenticity but also limited participation by international users who lacked such credentials. Consequently, cross-cultural validation is exploratory rather than representative.

Open-ended responses (N ≈ 50) provide qualitative triangulation across developed, emerging, and conflict-affected contexts, yet broader sampling—from Western, Latin American, and African participants—is required to test TLHF and SE under diverse institutional and cultural conditions (e.g., Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance or power distance). Future studies should employ globally accessible survey systems to improve representativeness and inclusiveness, and pursue longitudinal tracking to capture how satisficing behavior evolves as governance systems mature.

Ultimately, satisficing offers a human-centered equilibrium between technological performance and ethical accountability—advancing SDGs 8, 12, and 17 through sustainable, coordinated digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; Methodology, S.H. and G.S.; Validation, G.S. and L.J.; Formal analysis, S.H.; Investigation, S.H. and L.J.; Data curation, L.J.; Writing—original draft, S.H.; Writing—review & editing, S.H. and G.S.; Visualization, S.H. and L.J.; Supervision, G.S.; Funding acquisition, L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the institutional and national guidelines for social-science research ethics. Ethical review and approval were waived by the Institutional Review Board of Youngsan University because the study involved anonymous, minimal-risk online surveys and interviews, and did not include any personally identifiable or medical information.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided electronic informed consent before participation and could withdraw at any time without penalty.

Data Availability Statement

Aggregated datasets and replication materials (survey coding and analysis scripts) are included in the Appendices. Due to privacy protection and sensitive geographic metadata, individual-level data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and a signed data-use agreement.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the 1,590 survey respondents and 35 interviewees for their voluntary participation, and further acknowledge the additional participants who contributed to the expanded validation dataset (N = 1,840). The survey was conducted through Tencent Survey, whose authentication requirements ensured data integrity but also limited access for some international users. The authors are grateful to overseas participants who nevertheless completed the questionnaire despite technical and connectivity constraints. Their contributions enriched the cross-cultural analysis of trust, usability, and transparency across diverse contexts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Suanpang, P.; et al. Integrating Generative AI and IoT for Sustainable Smart Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. How Artificial Intelligence (AI) Is Powering New Tourism Marketing and the Future Agenda for Smart Tourist Destinations. Electronics 2024, 13(21), 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, A.B.; Forid, M.S.; Yong, L.; Du, A.M.; Goodell, J.W. Artificial intelligence as a catalyst for sustainable tourism growth and economic cycles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2025, 210, 123875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschprung, R.S. Is the Privacy Paradox a Domain-Specific Phenomenon? Computers 2023, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzoglou, E.; et al. The Role of Privacy Obstacles in the Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Perspective. Systems 2023, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, G.J.S. The Theory of Risk Homeostasis: Implications for Safety and Health. Risk Analysis 1982, 2, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.A.; Loeb, M.P. The Economics of Information Security Investment. ACM Transactions on Information and System Security 2002, 5, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R.B. Attitudinal Effects of Mere Exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1968, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in Automation: Designing for Appropriate Reliance. Human Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firmino de Souza, D.; et al. Trust and Trustworthiness from a Human-Centered Standpoint: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2025, 14, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S. Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1979, 74, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S.; Devlin, S.J. Locally Weighted Regression: An Approach to Regression Analysis by Local Fitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1988, 83, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall: London, U.K., 1986.

- Jin, Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Artificial Intelligence as a Catalyst for Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study from China. Systems 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S.; Hoffmann, A.; Giovannini, E. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Pagkalou, F.I.; Liapis, K.I.; Thalassinos, E.I. Defining the Total CSR Z-Score: A Methodological Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlidayi, I.C.; Gupta, L. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: A Critical Step in Multi-National Survey Studies. Journal of Korean Medical Science 2024, 39(49), e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Vera, B.M.; Pelegrín-Entenza, N. Methodological Reflection on Sustainable Tourism in Protected Natural Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Evaluation of attraction and spatial pattern analysis of world heritage tourist destinations in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, G. Bounded Rationality: A Simon-Like Explication. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1994, 18, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Huang, K.; Ying, S.; Huang, W.; Kang, Z. Modeling of Time Geographical Kernel Density Function under Network Constraints. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, T.D. Best Practices for Estimating, Interpreting, and Presenting Average Marginal Effects. Sociological Science 2019, 6, 81–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nature Machine Intelligence 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, L.; Di Dio, C.; Manzi, F.; Massaro, D.; Bisconti, P.; Marchetti, A. Decoding Trust in Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Measures and Related Variables. Informatics 2025, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Yamaka, W.; Liu, J. Collaborative Digital Governance for Sustainable Rural Development in China: An Evolutionary Game Approach. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, R.; Xu, G. Sustainability of the Rural Environment Based on a Tripartite Game among Government, Enterprises, and Farmers under the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Sustainability 2025, 17, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Ji, Z.; Jin, X. Research on Privacy-by-Design Behavioural Decision-Making of Information Engineers Considering Perceived Work Risk. Systems 2024, 12, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.B. Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events. The Economic Journal 1989, 99, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Boulos, M.N.K.; et al. Privacy-by-Design Environments for Large-Scale Health Research and Federated Learning from Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikraftar, T.; Jafarpour, E. Using Q-methodology for Analyzing Divergent Perspectives about Sustainable Tourism. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 23, 5904–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Fang, L.; Li, X. Key Factors and Configuration Analysis of Improving Tourist Loyalty in Forest Park: Evidence from Yingde National Forest Park, South China. Forests 2025, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, L. Assessment and Improvement Strategies for Sustainable Development in China’s Cultural and Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.L.; Nițu, A.; Ionescu, A.; Gheorghe, I.G. AI-Enhanced Strategies to Ensure New Sustainable Destination Tourism Trends among the 27 European Union Member States. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030, 2nd ed.; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, A.; Ben Youssef, A.; Maherzi Zahar, T. The Role of Digital Tourism Platforms in Advancing Sustainable Development Goals in the Industry 4.0 Era. Sustainability 2025, 17(8), 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. Journal of Business Research 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Information Systems Research 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xia, Z.; Zeng, Z. The Economic Governance Capability of the Government and High-Quality Development of China’s Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).