1. Introduction

The integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) into tourism services has markedly reshaped how consumers access and evaluate travel information. ChatGPT, created by OpenAI in 2022, is a major tool in the travel industry that allows instant, custom and appropriate advice to users through casual conversations (Lecler et al., 2023, Haleem et al., 2022). Today, ChatGPT is used throughout tourism such as while making an itinerary and picking destinations, thanks to services like Trip.com’s TripGen (Dwivedi et al., 2023). The study by Statista (2023) indicates that the revenue share of AI-influenced travel businesses will go from 21% to 32% in the next year due to AI’s impact on how people choose travel services. Even with this growth, not much is known from current academic studies about how tourists use ChatGPT when faced with information uncertainty (Gursoy et al., 2023).

Amid this growing adoption, however, a critical challenge emerges: the uncertainty users experience when assessing the reliability and accuracy of information provided by ChatGPT. A critical issue remains the uncertainty users feel regarding the reliability and accuracy of the information provided by generative AI systems (To & Yu, 2025; Tosyalı et al., 2024). User uncertainty is particularly critical in the context of tourism, where decisions involve significant personal and financial implications. Scholars note that uncertainty directly impacts travel intentions, destination image perceptions, and sustained usage of AI systems (Chang et al., 2024; Stergiou & Nella, 2024). However, limited research has empirically explored what specific antecedents contribute significantly to reducing such uncertainty in generative AI contexts.

In addressing these gaps, previous literature has primarily explored general technology adoption or generic AI interactions, leaving the psychological mechanisms influencing uncertainty largely unexamined within tourism contexts (Orden-Mejía et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025). Anthropomorphism, defined as the attribution of human-like traits to non-human agents (Epley et al., 2007), has been suggested as one method to mitigate uncertainty, yet empirical support in tourism is scant and inconclusive (Song & Shin, 2022). Meanwhile, AI skepticism, the cautious and critical stance users take toward AI capabilities and ethical implications (Gursoy et al., 2019), is typically seen as exacerbating uncertainty. Intriguingly, recent studies indicate skepticism might paradoxically lead to a more deliberate information processing that reduces rather than increases uncertainty (Dietvorst et al., 2015; Kieslich et al., 2020).

To provide clarity on these issues, this study applies Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT) as a theoretical lens to investigate anthropomorphism and AI skepticism as sources of uncertainty. URT posits that individuals seek information to reduce uncertainty and enhance predictability during initial interactions (Berger & Calabrese, 1975; Tidwell & Walther, 2002). Extending URT to generative AI in tourism contexts, this research aims to empirically assess whether anthropomorphism or skepticism more significantly contributes to reducing uncertainty (Low Level of Uncertainty, LLU). Additionally, the study examines the subsequent effects of LLU on two critical user outcomes: continued usage intention of ChatGPT and intention to visit the recommended tourism destinations. Thus, the central research objective is to identify which factor—anthropomorphism or AI skepticism—predominantly influences LLU and how LLU mediates favorable behavioral intentions.

By explicitly addressing these constructs within an integrated model, this study makes two primary contributions. First, it expands URT’s application into the AI-assisted tourism decision-making context, offering new theoretical insights into human-AI interactions. Second, it is the first to empirically compare anthropomorphism and AI skepticism as dual predictors of informational uncertainty in generative AI interactions.

Research Objectives:

1. To investigate whether anthropomorphism significantly reduces user uncertainty when using ChatGPT for travel decisions.

2. To determine the role of AI skepticism in influencing user uncertainty levels in generative AI interactions.

3. To assess how low levels of uncertainty influence continuance usage intention towards ChatGPT.

4. To evaluate the impact of low uncertainty perceptions on users’ destination visit intentions.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Previous Studies and Gaps Identification

Table 1 presents thorough literature review conducted by the authors to identify the gaps of previous study that will be addressed by this study. Chang et al. (2024), grounded in Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT), investigated how users reduce uncertainty when interacting with ChatGPT in educational contexts. They found that interactive uncertainty reduction strategies (URS) were more effective than passive URS. While the study highlighted the role of information transparency, accuracy, and privacy in shaping uncertainty, it did not address how these dynamics influence tourism-specific behaviors such as destination visit intention, nor did it consider AI skepticism or anthropomorphism, which are increasingly important in tourism AI adoption studies. Orden-Mejía et al. (2025) applied the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to understand how information quality, enjoyment, and usefulness influence continuance usage intention and subsequent destination visit intention in tourism contexts. Although their findings reinforce the role of satisfaction in behavioral intention, the study lacks attention to key psychological factors such as uncertainty, AI skepticism, and perceived anthropomorphism, which are essential to comprehending user trust and emotional security in human-AI interactions.

Xu et al. (2025) employed the PAD (Pleasure-Arousal-Dominance) framework to explore how service ubiquity, entertainment, and anthropomorphism influence emotional responses, and continued usage of ChatGPT in tourism. Their results confirm that anthropomorphism shapes pleasure and dominance, which in turn lead to positive word-of-mouth and continuance intention. However, the study does not consider how perceived uncertainty or skepticism toward AI might undermine these effects. Additionally, destination visit intention, a key outcome in tourism behavior, was not addressed. Gambo and Ozad (2021) examined URS strategies in social media use within education, showing that active, passive, and interactive methods significantly reduce perceived uncertainty and enhance continued use. However, the study is limited in both scope and context—it does not consider tourism applications, nor does it include constructs such as anthropomorphism, AI skepticism, or destination-related outcomes. Addressing these cumulative gaps, the present study advances the application of URT into the tourism sector, explicitly examining ChatGPT usage with a more comprehensive and integrated set of constructs—anthropomorphism, AI skepticism, and low level of uncertainty. The proposed model argues analytically that anthropomorphism and AI skepticism play a critical role in mitigating users' perceived uncertainty toward ChatGPT. The subsequent reduction in uncertainty is then posited to positively influence users' intentions for continuous ChatGPT usage and, notably, their intentions to visit tourism destinations.

2.2. Uncertainty Reduction Theory

Uncertainty Reduction Theory, first coined by Berger and Calabrese (1974), asserts how individuals seek to reduce uncertainty in initial interactions by gathering information to make behavior more predictable. URT which was first used in human interactions, has later been applied to online and AI-enabled communication and tourism scenarios (Tidwell & Walther, 2002; Wang et al., 2016). In the context of AI-driven tourism tools like ChatGPT, users often experience uncertainty due to unfamiliarity with the technology or doubts about information reliability. This study applies URT to explore how anthropomorphism and AI skepticism influence users’ perceived low level of uncertainty, which subsequently shapes continuance usage intention and destination visit intention.Anthropomorphism, or attributing human-like features to AI, can decrease how uncertain users feel while making them feel more comfortable and related to the AI (Song & Shin, 2022; Cheng et al., 2021). When users find ChatGPT to be human-like, they are likely to find the responses clearer and more understandable which leads to fewer unclear choices. While traditional theory suggests that AI skepticism should increase uncertainty, findings from this study suggest a more complex relationship. Skeptical users may be more vigilant and thoughtful in their use, leading to a paradoxical increase in confidence about AI outputs—thus contributing to lower perceived uncertainty (Kieslich et al., 2020). As uncertainty decreases, users are more likely to continue using ChatGPT and to act on its travel recommendations. Prior studies have confirmed that reduced uncertainty fosters technology adoption and destination-related behavior (Cheng et al., 2021; Stergiou & Nella, 2024). Thus, URT offers a strong foundation for understanding how psychological perceptions influence AI use in tourism. By focusing on anthropomorphism and skepticism as antecedents to uncertainty, this study extends URT into a novel domain of AI-assisted travel behavior.

2.3. Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism refers to assigning people-like feelings, habits and personality to AI, robots or digital assistants (Epley et al., 2007; Nass & Moon, 2000). Having anthropomorphic design in technology encourages users to interact with it like they would with a person, making the interaction natural (Nowak & Fox, 2018). In AI environments like ChatGPT, using anthropomorphism makes it easier for people to understand, expect results and sense the emotional side of the situation (Song & Shin, 2022). From the URT perspective (URT; Berger & Calabrese, 1975), human-like interactions with AI create a psychologically comfortable environment, mitigating ambiguity in communication. Areas like tourism which involve high risks and costs, benefit greatly from reduced uncertainty by getting reliable and clear details (Cheng et al., 2021). Having anthropomorphic characteristics in AI makes interactions more casual and clear which helps build reliability and trust in the output (Rzepka & Berger, 2018). So, anthropomorphism helps AI systems decrease user uncertainty. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Anthropomorphism significantly affects low level of uncertainty.

2.4. AI SKepticism

AI skepticism pertains to individuals' doubts or caution concerning the reliability, safety, or ethical implications of AI technologies (Gursoy et al., 2019; Kieslich et al., 2020). Many people skeptic to AI, mainly because they see risks, could lose some control, have moral concerns and notice AI’s frequent negative portrayal in the media (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2020). Usually, being skepticism increases perceived uncertainty, since some users might question what AI systems say. Yet, recent studies suggest a nuanced relationship in the specific context of ChatGPT. Those who are doubtful may look into the details more carefully which eventually strengthens their certainty and lowers doubt about the outcomes (Dietvorst et al., 2018; Gursoy et al., 2019). Having such skepticism helps people use AI systems more cautiously which may allow them to process data more accurately and thus fewer doubts in their thoughts. Understanding this relationship, expressing skepticism about AI may actually encourage people to pay closer attention to what they read on ChatGPT.

Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

AI skepticism significantly affects low level of uncertainty.

2.5. Continuous Visit Intention

Low-level uncertainty—defined as users’ perception of ChatGPT's responses as clear, accurate, and reliable—plays a key role in shaping continued use in AI-enabled tourism. When users feel the information is dependable and consistent, it builds trust and encourages repeated interaction (Gefen et al., 2003; Komiak & Benbasat, 2006). This is particularly relevant in tourism, where real-time, high-stakes decisions rely on AI guidance (Stergiou & Nella, 2024). According to the Expectation Confirmation Model (Bhattacherjee, 2001), when perceived service quality meets user expectations, satisfaction drives continuance intention. Additionally, Uncertainty Reduction Theory (Berger & Calabrese, 1975) suggests that reduced uncertainty fosters trust, further supporting ongoing use. Thus, reliable and low-uncertainty AI outputs are essential for sustained engagement with ChatGPT in tourism planning.

H3.

Low level of uncertainty positively influences ChatGPT continuance usage intention.

2.6. Destination Visit Intention

Uncertainty is a key factor influencing tourists’ decision-making when selecting destinations. In AI-mediated contexts, such as when using ChatGPT, users who perceive the information provided as low in uncertainty are more likely to feel confident in both the AI platform and the destination being suggested (Tosyalı et al., 2025). Guided by the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework, the AI’s output (stimulus) shapes users’ cognitive evaluations (organism), which in turn drive behavioral responses like travel intention (Pham et al., 2024). When uncertainty is reduced, users experience greater clarity and find the information more diagnostic and trustworthy, both of which enhance destination image and increase the likelihood of travel planning (Cheng et al., 2021). In the post-pandemic tourism landscape, where risk perception and digital reliability become concerns, the assurance of clear and consistent information fosters psychological comfort. This reduction in cognitive dissonance contributes to a stronger sense of control over decision-making (Ajzen, 1991). Consequently, lower uncertainty not only improves the user experience but also emotionally engages travelers and motivates them to act on their travel intentions (Stergiou & Nella, 2024).

Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4:

Low level of uncertainty significantly affects destination visit intention.

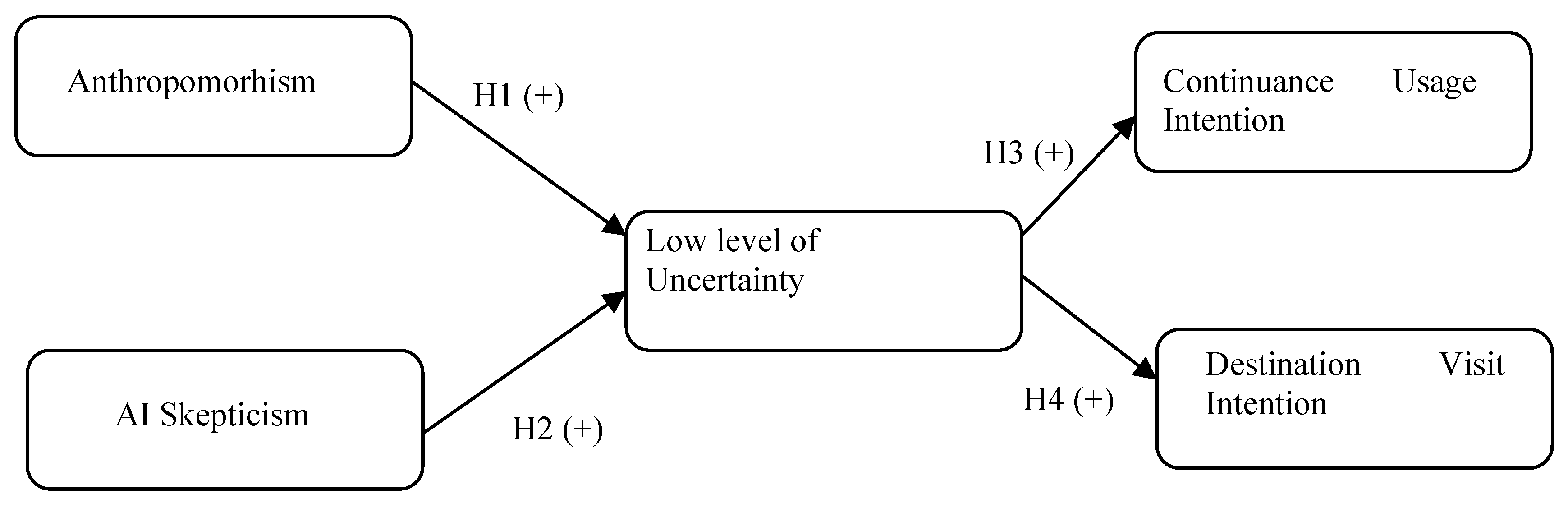

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

3. Methods

3.1. Operationalization and Measurement Items

The researchers examine and assess the core constructs to guarantee that the findings are valid and that the outcomes do not contradict within the study. The main factors researched are anthropomorphism, low level of uncertainty, destination visit intention, and continuance usage intention. The 7-point Likert scale is used to rate each construct, from 1 ("strongly disagree") to 7 ("strongly agree").

Table 2 shows a thorough list of all measurement items.

3.2. Sampling Technique and Data Collection

The present study exercised purposive sampling, a form of non-probability sampling, to make sure they fit the eligibility criteria. The survey included the requirements for respondents to: (1) be either male or female, (2) be 18 years old or older, (3) have finished high school or its equivalent, and (4) have previously used ChatGPT. The criteria made it possible to pick participants who would be most helpful to the study. An online questionnaire made in Google Forms was distributed on Line, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram to collect the data. There were three different parts in the survey: a part to check eligibility, a part for gathering demographics, and a part to assess the respondent’s intentions. Those taking part used a 7-point Likert scale to clearly indicate their views and opinions. Over December 2024- February 2025, the authors gathered 450 valid surveys. This data makes it possible to thoroughly investigate the things influencing choosing to visit a destination and continuance usage intention of ChatGPT.

3.3. Analysis Technique

The analysis in this study was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with SmartPLS 4.0. SEM was selected due to its effectiveness in investigating emerging research areas, particularly in understanding the interrelationships among multiple variables (Hair et al., 2017). This method enables the examination of latent constructs—such as behavioral intention—through their observed indicators. Since latent variables are not directly measurable, they were assessed through observed dimensions, including the social and technical aspects of live streaming and the trust transfer mechanism (Falk & Miller, 1992). To ensure the reliability and appropriateness of the constructs, Common Method Variance (CMV) was addressed at the outset. The construct validity was confirmed by verifying that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) outcomes were greater than 0.5 and the factor loadings had values more than 0.7 following the guidelines by Baumgartner and Weijters (2021). Reliability was further validated by assessing both Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) exceeded a value of 0.7 as suggested by Hair et al. (2017). The Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied to assess discriminant validity by making sure that the square root of each AVE was greater than any correlation between the present construct and other constructs. In addition, the cross-loading matrix demonstrated that each item loaded more strongly on its associated construct than on any others (Henseler et al., 2015). Finally, hypothesis testing was performed by examining Goodness of Fit (GoF), R-squared values, and Q-squared values, thereby strengthening the study’s robustness and credibility through a rigorous, step-by-step analytical process.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

The study included the feedback of 450 people who had previously used ChatGPT. In terms of gender, 62.44% of the respondents were male and majority of the respondents were aged 30 to 39 (249, 55.33%), followed by aged 20 to 29 (137, 30.44%). Related to education level, (218 or 48.44%) of respondents have a bachelor’s degree, followed by (103 or 22.89%) have a master’s degree, highlighting the high educational level among community members. Occupationally, most respondents were civil servants (115 respondents) and private employees (98 respondents), proving the popularity of ChatGPT in both sectors. The most frequent responses for how long respondents have been using ChatGPT were 10–12 months (31.56%) and 6–9 months (29.11%), indicating they have spent a moderate amount of time with the platform. About 34.67% (156 respondents) of the participants used ChatGPT to find travel information and 17.11% (77 respondents) used it for academic reasons which is in line with the exploration of behavioral intention in tourism. This shows that those included are experienced, well-educated and driven by practice, showing that the research’s constructs matter. The full demographic information is given in

Table 3.

4.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

To evaluate Common Method Variance, the authors first used Harman’s single-factor test, following the guidelines from Baumgartner and Weijters (2021). The test was done to see if one main factor could explain most of the variation in the data, as this would raise concerns about common method bias. Since only one factor explained just over 45.7% of the variance, which is below 50%, the common method bias of this study is unlikely to have a significant issue. In addition, the robustness of Common Method Variance (CMV) was further evaluated using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) method. According to established guidelines, VIF values below 3 suggest that multicollinearity is not a concern among the measurement items. In this study, VIF values ranged from a minimum of 1.000 to a maximum of 2.046, well within the acceptable threshold. These results confirm that CMV does not pose a significant issue, supporting the reliability of the data.

4.3. Validity and Reliability Assement

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed using SmartPLS 4.0 to rigorously assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. A systematic evaluation was conducted to ensure the robustness and quality of the model. Initially, factor loadings were examined, all of which exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.7, confirming the reliability of the measurement items used to represent their respective constructs (Hair et al., 2017). As presented in

Table 4, the results demonstrate that each construct is accurately reflected by its corresponding indicators, supporting the model’s overall measurement validity.

Following this, the values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were analyzed to test for convergent validity. All reported AVE values were higher than the required value of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2017), confirming that every latent factor explains much of the variation in its individual indicators, as can be seen in

Table 4. To see how the measures relate to each other internally, Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) were used and all the constructs exceeded the threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017). These results assert that the constructs are reliable and effective at measuring behavioral intention in the context of the study.

Table 4 shows that the model is strong and reliable, indicating it is ready for further analysis.

Once validity and reliability were established, discriminant validity was evaluated with three standard approaches. Firstly, the Fornell-Larcker measure was applied and it requires that the square root of an AVE be bigger than its correlation with other constructs. All the constructs in the study met this condition, confirming discriminant validity, as it can be seen in

Table 5. Secondly, using cross-loading analysis confirmed that all items loaded more strongly on the construct they were developed for rather than any other one, as shown in

Table 7 further supporting discriminant validity. Next, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) was applied with a threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015). As exhibited in

Table 6, the HTMT values were all lower than the prescribed threshold, showing that the constructs are disctinct from one another.

4.4. Model Robustness Testing

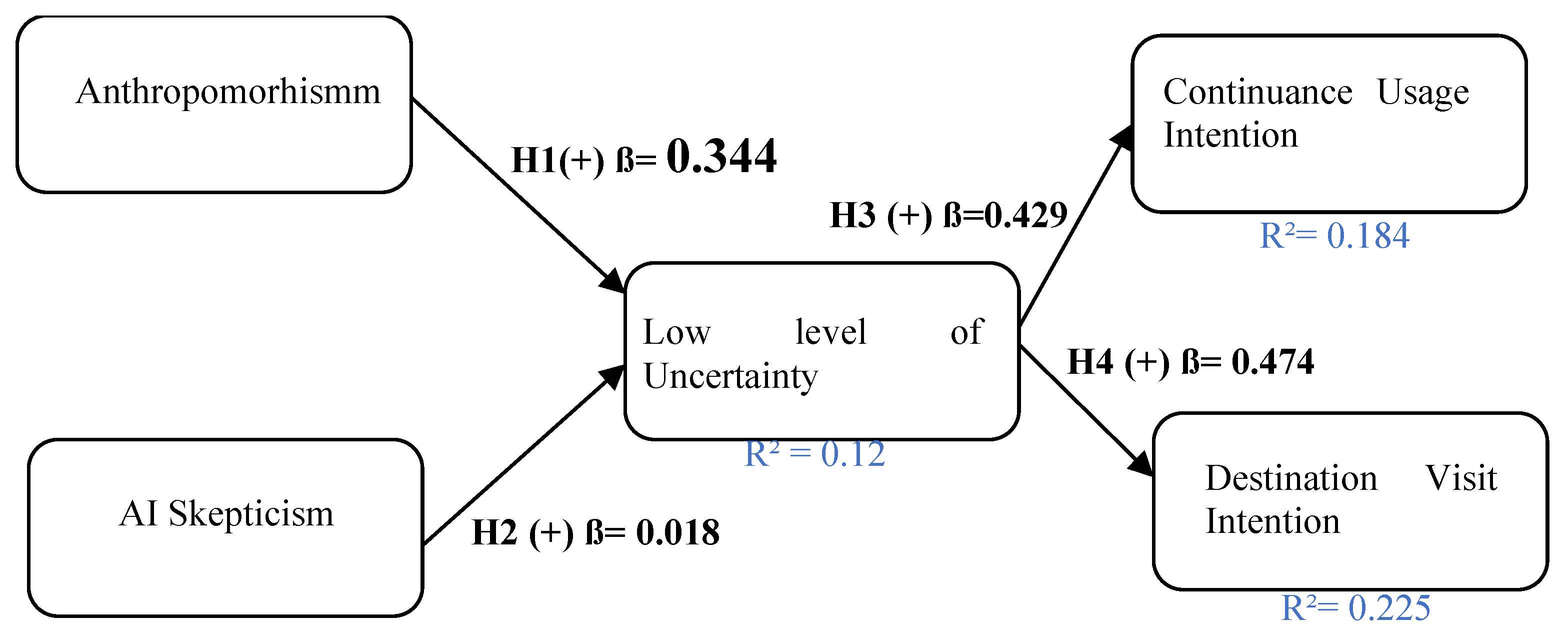

Initially, R² values for the outcomes were studied to see how well they were explained by the predictors. Falk and Miller (1992) suggest that a value of R² greater than 0.1 signifies a model is viable. The present study’s findings show that continuance usage intention (R² = 0.184), destination visit intention (R² = 0.225) and perceived low uncertainty (R² = 0.12), signifying they can be explained by AI skepticism and anthropomorphism. Based on these findings, it is likely that the model accurately explains how the constructs relate to each other and gives useful insights into what leads to destination visit intention and ChatGPT continuance usage intention. After that, the authors examined how the whole model fits together as a whole. As Hair et al. (2017) suggest, if the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) has a value not exceeding 0.05 or 0.08, the model fit is satisfactory. This research’s SRMR value (0.076) is considered acceptable. Besides, the results from d_ULS (1.017), d_G (0.362) and NFI (0.634) further suggested that the model was strong enough, based on accepted guidelines for a robust structural model. Afterward, the authors assessed Q² with continuance usage intention (Q² = 0.028), destination visit intention (R² = 0.1), and low level of uncertainty (Q² = 0.079) further confirmed predictive relevance (Henseler et al. 2015).

To assess the overall reliability and effectiveness of the research model, the Goodness of Fit (GoF) index was employed. GoF provides a comprehensive measure by integrating both the model’s explanatory power (R²) and convergent validity (AVE) into a single value. It is calculated by multiplying the average R² by the average AVE and then taking the square root of the result. This approach offers a holistic evaluation of how well the model fits the data and captures the relationships among the constructs. The GoF formula is as follows:

According to established benchmarks proposed by Tenenhaus et al. (2005) and Wetzels et al. (2009), GoF values below 0.10 suggest a poor fit, values between 0.10 and 0.25 indicate a small fit, between 0.25 and 0.36 represent a moderate fit, and values above 0.36 denote a strong fit. In this study, the calculated GoF was 0.467, signifying a high model fit. These results confirm that the research model is robust and effectively captures the structural relationships among the observed constructs.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 8 exhibits the results of hypothesis testing of this study. For H1 of AI skepticism significantly influences low level of uncertainty is accepted with path coefficient of 0.344 and T-value of 3.079. H2 of anthropomorphism significantly affects low level of uncertainty is rejected with path coefficient of 0.018 and T-value of 0.465. H3 of low level of uncertainty significantly affects continuance usage intention is accepted with path coefficient of 0.429 and T-value of 4.751. Meanwhile, H3 of low level of uncertainty significantly affects destination visit intention is accepted with path coefficient of 0.474 and T-value of 5.207.

Figure 2 exhibits hypothesis summary of this study.

5. Discussion

H1 of AI skepticism significantly influences low level of uncertainty, was accepted (β = 0.344, T = 3.079). This finding asserts that people who doubt AI tend to feel less uncertain when they communicate with ChatGPT. It signifies that skepticism might trigger a more critical and analytical approach from users, leading them to scrutinize and verify AI-generated information more carefully. Such meticulous engagement paradoxically results in greater confidence and lower perceived uncertainty. This is in line with Dietvorst et al. (2015), who observed similar phenomena known as "algorithm aversion," where initial skepticism prompts deeper cognitive engagement with AI-generated results, subsequently fostering greater trust and certainty upon verification. Similarly, Gursoy et al. (2019) contend that skepticism may lead to finding out more about technology which later boosts trust in it.

H2 of anthropomorphism significantly affects low level of uncertainty, was rejected (β = 0.018, T = 0.465). This result implies that the human-like characteristics of ChatGPT did not meaningfully reduce perceived uncertainty. Travelers might value having up-to-date, true and relevant information when booking a trip above the AI being able to interact with them naturally. Prior studies have also indicated mixed results for anthropomorphism's role in uncertainty reduction, suggesting context-dependent effects. For instance, Song and Shin (2022) found that excessive anthropomorphism could trigger a sense of unease or perceived manipulation among users, a phenomenon known as the "uncanny valley," potentially diluting its positive effects on uncertainty reduction. Chen et al. (2024) concluded that task difficulty and how much information is revealed matter when using anthropomorphic cues which may explain the lack of strong effects seen in this tourism-planning research.

H3 of low level of uncertainty significantly affects continuance usage intention, was accepted (β = 0.429, T = 4.751). This finding asserts that when users see ChatGPT's outputs as accurate, reliable, and clear, they are likely to maintain continued engagement. This finding is consistent with the Expectation Confirmation Model by Bhattacherjee (2001), which argues that confirming users' information quality expectations cause greater satisfaction and repeated use. Moreover, Gefen et al. (2003) and Komiak and Benbasat (2006) emphasize that clear and reliable interactions with technology enhance cognitive trust, a critical driver of sustained technology usage behaviors. In tourism, Stergiou and Nella (2024) underscore the importance of reducing ambiguity in travel-related information to foster repeat interactions with AI-based recommendation systems.

H4 of low level of uncertainty significantly influences destination visit intention, was also accepted (β = 0.474, T = 5.207). This highlights that reducing perceived uncertainty through reliable AI-generated information significantly impacts users' travel intentions. The S-O-R framework by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) supports this result by positing that the perceived quality and clarity of external stimuli (ChatGPT information) directly influence internal evaluations (confidence and perceived clarity), subsequently guiding behavioral intentions. Ajzen (1991) further explains this through the lens of the TPB, where reduced uncertainty enhances perceived behavioral control, increasing users’ intention to follow through with recommended travel plans.

This study successfully addressed its four research objectives through robust empirical analysis. Next, it asserted evidence that AI skepticism makes using ChatGPT for tourism appear clearer to users, meeting the first objective which was to show that skepticism reduces user uncertainty. As suggested by prior studies, skeptical users tend to use critical thinking when using AI, resulting in higher confidence trust in the outcomes (Dietvorst et al., 2015; Kieslich et al., 2020). Moreover, the second objective regarding anthropomorphism's role in reducing uncertainty was not supported, indicating that human-like features alone may not sufficiently alleviate user doubts in high-stakes decision-making like travel planning (Gursoy et al., 2019; Song & Shin, 2022). Third, the study found that increased certainty or knowledge about ChatGPT leads to higher intentions to keep using it and underlines the role of understanding in maintaining user involvement (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Komiak & Benbasat, 2006). Finally, the positive effect of reduced uncertainty on users’ intentions to visit AI-recommended destinations, thereby achieving the fourth objective. This is based on what prior study has found that lower uncertainty can make a destination image stand out and help customers decide confidently when booking online (Stergiou & Nella, 2024).

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The current study significantly contributes to the theoretical understanding of user interaction with ChatGPT within the tourism domain, specifically by expanding the URT. Prior research utilizing URT primarily investigated traditional contexts or general technology usage scenarios (Gambo & Ozad, 2021; Chang et al., 2024), often neglecting the distinct psychological dimensions relevant to AI-mediated decision-making. This research addresses these limitations by examining two critical yet underexplored antecedents of uncertainty—AI skepticism and anthropomorphism—in shaping user perceptions within AI-assisted tourism decisions. The findings importantly reveal that AI skepticism, traditionally perceived negatively in technology adoption literature, can paradoxically enhance clarity and reduce user uncertainty through increased vigilance and critical scrutiny of information (Dietvorst et al., 2015; Gursoy et al., 2019). This novel insight enriches URT by highlighting a nuanced psychological mechanism where skepticism acts constructively rather than detrimentally in technology-mediated communication.

Contrarily, the insignificant effect of anthropomorphism on reducing uncertainty suggests the conditional and context-dependent effectiveness of anthropomorphic cues. This result challenges prevailing assumptions from earlier research, which broadly advocated anthropomorphic features as universally beneficial for enhancing user engagement and reducing ambiguity (Song & Shin, 2022; Cheng et al., 2021). The current findings indicate the need for more nuanced theoretical modeling that accounts for situational or task-specific factors influencing the utility of anthropomorphism in technology use. Finally, the significant direct influences of low-level uncertainty on continuance usage and destination visit intention empirically substantiate URT's applicability in tourism-specific AI interactions. By explicitly confirming uncertainty reduction as a critical cognitive mediator driving both continuous technology usage and travel behaviors, this research advances the theoretical discourse in AI-enabled tourism and behavioral decision-making frameworks (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Stergiou & Nella, 2024). Thus, this study provides a comprehensive theoretical expansion of URT, addressing the psychological complexity inherent in AI-driven tourism contexts.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study’s findings offer several practical implications for users, destination managers, and tourism marketers. For users, the study posits that that AI skepticism can reduce uncertainty, a critical implication for users is the importance of maintaining a thoughtful and evaluative approach when engaging with ChatGPT in tourism planning. Skepticism should be understood as a helpful mental process that helps someone check the information provided by ChatGPT. Skeptical people often check if the information is trustworthy and important, helping them decide better. ChatGPT should be seen as a tool to support planning, so users should compare its results with information given by tourism boards, reputable travel agencies, and peer travel reviews. Also, writing clear and personalized prompts, for example by listing your expected trip details, can help ChatGPT provide clearer and more helpful information.

Meanwhile, destination managers can influence the visibility and accuracy of AI-sourced content through indirect content seeding. This involves curating destination-related content on websites (such as official DMO pages, Wikipedia, and open-access blogs), which ChatGPT draw from during training and real-time searches. Managers should prioritize uploading structured data (e.g., opening hours, event schedules, and local insights) in accessible formats, so that ChatGPT can gather up-to-date and rich information. Additionally, ensuring multilingual content availability and clear cultural context can mitigate visitor uncertainty, especially for international markets.

Likewise, tourism marketers may align their digital content with AI-generated outputs. Since the study shows that low levels of uncertainty foster both destination visit intention and continuance usage, marketers can develop clear, evidence-based narratives around safety, accessibility, and uniqueness of the destination. Embedding frequently asked questions (FAQs), or scenario-based storytelling into official content helps reinforce clarity and reduce perceived ambiguity among potential tourists. Moreover, marketers can produce video-based content or structured visual guides (e.g., interactive maps and digital itineraries), which are often summarized by AI systems, thus ensuring that tourists receive streamlined, confident messaging when using ChatGPT for travel planning.

7. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

This study examined how anthropomorphism and AI skepticism affect perceived uncertainty in generative AI tourism contexts. The findings show that while anthropomorphism does not significantly reduce uncertainty, AI skepticism plays a constructive role in lowering it. Reduced uncertainty, in turn, positively influences both continued use of ChatGPT and intention to visit AI-recommended destinations. These insights extend Uncertainty Reduction Theory to AI-assisted tourism decision-making and highlight the value of critical user engagement. This study has a limitation as it focused only on ChatGPT. Further work could compare different generative AI tools to generalize the findings. Future studies may also explore user characteristics that moderate the effects of AI skepticism on uncertainty and travel behaviors.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.D.K.S., A.P.T., and I.J.E.; methodology, A.D.K.S.; software, I.J.E.; validation, A.D.K.S, I.J.E., and A.P.T.; formal analysis, A.D.K.S.; investigation, I.J.E., and A.D.K.S.; resources, A.P.T.; data curation, A.D.K.S. and I.J.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.K.S. and A.P.T.; writing—review and editing, A.D.K.S and I.J.E. and; visualization, I.J.E.; supervision, A.D.K.S.; project administration, A.D.K.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The data analyzed during the present work are not publicly available due to respect to respondent’s privacy

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afshardoost, M., & Eshaghi, M. S. (2020). Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Manament, 81, 104154.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Baumgartner, H., & Weijters, B. (2021). Structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 549-586). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS quarterly, 351-370.

- Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. J. (1974). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(2), 99–112.

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519.

- Chang, Y. H., Silalahi, A. D. K., & Lee, K. Y. (2024). From uncertainty to tenacity: Investigating user strategies and continuance intentions in AI-powered ChatGPT with uncertainty reduction theory. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1-19.

- Çelik, K., & Ayaz, A. (2022). Validation of the Delone and McLean information systems success model: A study on student information system. Education and Information Technologies, 27(4), 4709–4727.

- Chen, J., Guo, F., Ren, Z., Li, M., & Ham, J. (2024). Effects of anthropomorphic design cues of chatbots on users’ perception and visual behaviors. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(14), 3636–3654.

- Cheng, X., Bao, Y., Zarifis, A., Gong, W., & Mou, J. (2021). Exploring consumers' response to text-based chatbots in e-commerce: the moderating role of task complexity and chatbot disclosure. Internet Research, 32(2), 496-517.

- Chi, N. T. K., & Pham, H. (2024). The moderating role of eco-destination image in the travel motivations and ecotourism intention nexus. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10(2), 317–333.

- Choung, H., David, P., & Ross, A. (2023). Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(9), 1727–1739.

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., ... & Wright, R. (2023). Opinion paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Pandey, N., Currie, W., & Micu, A. (2024). Leveraging ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications in the hospitality and tourism industry: practices, challenges and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 1-12.

- Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864–886.

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Filieri, R., Alguezaui, S., & McLeay, F. (2015). Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust toward consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tourism Management, 51, 174-185. [CrossRef]

- Gambo, S., & Özad, B. (2021). The influence of uncertainty reduction strategy over social network sites preference. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research, 16(2), 116-127.

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS quarterly, 51-90.

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., Bilgihan, A., Okumus, F., & Shi, F. (2022). The impact of eWOM source credibility on destination visit intention and online involvement: A case of Chinese tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(5), 855–874.

- Gorji, A. S., Garcia, F. A., & Mercadé-Melé, P. (2023). Tourists' perceived destination image and behavioral intentions towards a sanctioned destination: Comparing visitors and non-visitors. Tourism Management Perspectives, 45, 101062.

- Gursoy, D., Chi, O. H., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169.

- Gursoy, D., Li, Y., & Song, H. (2023). ChatGPT and the hospitality and tourism industry: an overview of current trends and future research directions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32(5), 579-592.

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458.

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Singh, R. P. (2022). An era of ChatGPT as a significant futuristic support tool: A study on features, abilities, and challenges. BenchCouncil transactions on benchmarks, standards and evaluations, 2(4), 100089.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Irfan, M., Malik, M. S., & Zubair, S. K. (2022). Impact of vlog marketing on consumer travel intent and consumer purchase intent with the moderating role of destination image and ease of travel. Sage Open, 12(2), 21582440221099522.

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2020). Rulers of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons, 63(1), 37–50.

- Kelleher, S. R. (2023, May 10). A third of travelers are likely to use ChatGPT to plan a trip. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/suzannerowankelleher/2023/05/10/chatgpt-to-plan-a-trip/. 2023.

-

Kieslich, K., Lünich, M., & Marcinkowski, F. (2020).The Threats of Artificial Intelligence Scale (TAI): Development, Measurement and Test Over Three Application Domains . arXiv preprint, arXiv:2006.07211.

- Kim, J. H., Kim, J., Kim, C., & Kim, S. (2023). Do you trust ChatGPTs? Effects of the ethical and quality issues of generative AI on travel decisions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(9), 779–801.

- Komiak, S. Y., & Benbasat, I. (2006). The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS quarterly, 941-960.

- Ku, E. C. S. (2023). Anthropomorphic chatbots as a catalyst for marketing brand experience: Evidence from online travel agencies. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(23), 4165–4184. [CrossRef]

- Lecler, A., Duron, L., & Soyer, P. (2023). Revolutionizing radiology with GPT-based models: current applications, future possibilities and limitations of ChatGPT. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, 104(6), 269-274.

- Lin, X., Mamun, A. A., Yang, Q., & Masukujjaman, M. (2023). Examining the effect of logistics service quality on customer satisfaction and re-use intention. PLOS ONE, 18(5), e0286382.

- Marinchak, C., Forrest, E., & Hoanca, B. (2018). The impact of artificial intelligence and virtual personal assistants on marketing. Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 12(3), 10–16.

- McKinsey & Company. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. https://www.mckin sey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-ofgenerative-

ai-the-next-productivity-frontier.

- Mostafa, R. B., & Kasamani, T. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of chatbot initial trust. European Journal of Marketing, 56(6), 1748–1771.

- Muliadi, M., Muhammadiah, M. U., Amin, K. F., Kaharuddin, K., Junaidi, J., Pratiwi, B. I., & Fitriani, F. (2024). The information sharing among students on social media: The role of social capital and trust. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 54(4), 823–840.

- Nass, C., & Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81–103.

- Nowak, K. L., & Fox, J. (2018). Avatars and computer-mediated communication: A review of the definitions, uses, and effects of digital representations of people. Review of Communication Research, 6, 30–53.

- Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, M., Huertas, A., Carvache-Franco, O., & Carvache-Franco, W. (2025). Analysing how AI-powered chatbots influence destination decisions. PLOS ONE, 20(3), e0319463.

- Petter, S., DeLone, W., & McLean, E. R. (2008). Measuring information systems success: Models, dimensions, measures, and interre lationships. European Journal of Information Systems, 17(3), 236–263. [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. C., Duong, C. D., & Nguyen, G. K. H. (2024). What drives tourists' continuance intention to use ChatGPT for travel services? A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 78, 103758.

- Phelps, A. (1986), “Holiday destination image—the problem of assessment: An example developed in Menorca”, Tourism Management, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 168-180.

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality.

- Rzepka, C., & Berger, B. (2018). User interaction with AI-enabled systems: A systematic review of the evidence. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 171–189.

- Seçilmiş, C., Özdemir, C., & Kılıç, İ. (2022). How travel influencers affect visit intention? The roles of cognitive response, trust, COVID-19 fear and confidence in vaccine. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(17), 2789–2804.

- Shi, S., Gong, Y., & Gursoy, D. (2021). Antecedents of trust and adoption intention toward artificially intelligent recommendation systems in travel planning: A heuristic–systematic model. Journal of Travel Research, 60(8), 1714–1734.

- Shin, S., Kim, J., Lee, E., Yhee, Y., & Koo, C. (2025). ChatGPT for trip planning: The effect of narrowing down options. Journal of Travel Research, 64(2), 247–266.

- Statista. (2023). AI-influenced revenue share of travel companies worldwide 2018–2024. Statista Research Department. Retrieved May 31, 2025, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1378046/ai-revenue-share-travel-companies-worldwide/.

- Song, S. W., & Shin, M. (2022). Uncanny valley effects on chatbot trust, purchase intention, and adoption intention in the context of e-commerce: The moderating role of avatar familiarity. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 38(5), 441–456. [CrossRef]

-

Stergiou, D. P., & Nella, A. (2024). ChatGPT and Tourist Decision-Making: An Accessibility–Diagnosticity Theory Perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), e2757

.

- Tedjakusuma, A. P., Retha, N. K. M. D., & Andajani, E. (2023). The effect of destination image and perceived value on tourist satis faction and tourist loyalty of Bedugul Botanical Garden, Bali. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 85–99.

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational statistics & data analysis, 48(1), 159-205.

- Tidwell, L. C., & Walther, J. B. (2002). Computer-mediated communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations. Human Communication Research, 28(3), 317–348.

- Tosyali, H., Tosyali, F., & Coban-Tosyali, E. (2025). Role of tourist-chatbot interaction on visit intention in tourism: The mediating role of destination image. Current Issues in Tourism, 28(4), 511–526.

- To, W. M., & Yu, B. T. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Research in Tourism and Hospitality Journals: Trends, Emerging Themes, and the Rise of Generative AI. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 63.

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Wang, D., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2020). Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 140–154. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Xiang, Z., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2016). Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 52–63.

- Wang, H., & Yan, J. (2022). Effects of social media tourism information quality on destination travel intention: Mediation effect of self-congruity and trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1049149.

- Wang, L., Wong, P. P. W., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Travellers’ destination choice among university students in China amid COVID-19: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Tourism Review, 76(4), 749–763. [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS quarterly, 177-195.

- Whitmore, G. (2023, February 7). Will ChatGPT replace travel agents? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/geof fwhitmore/2023/02/07/will-chatgpt-replace-travel-agents/.

- Yang, X., Zhang, L., & Feng, Z. (2024). Personalized tourism recommendations and the e-tourism user experience. Journal of Travel Research, 63(5), 1183–1200.

- Xu, H., Law, R., Lovett, J., Luo, J. M., & Liu, L. (2024). Tourist acceptance of ChatGPT in travel services: the mediating role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(7), 955-972.

- Xu, H., Li, X., Lovett, J. C., & Cheung, L. T. (2025). ChatGPT for travel-related services: a pleasure–arousal–dominance perspective. Tourism Review.

- Ye, Y., You, H., & Du, J. (2023). Improved trust in human-robot collaboration with ChatGPT. IEEE Access, 11, 55748–55754.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).