Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

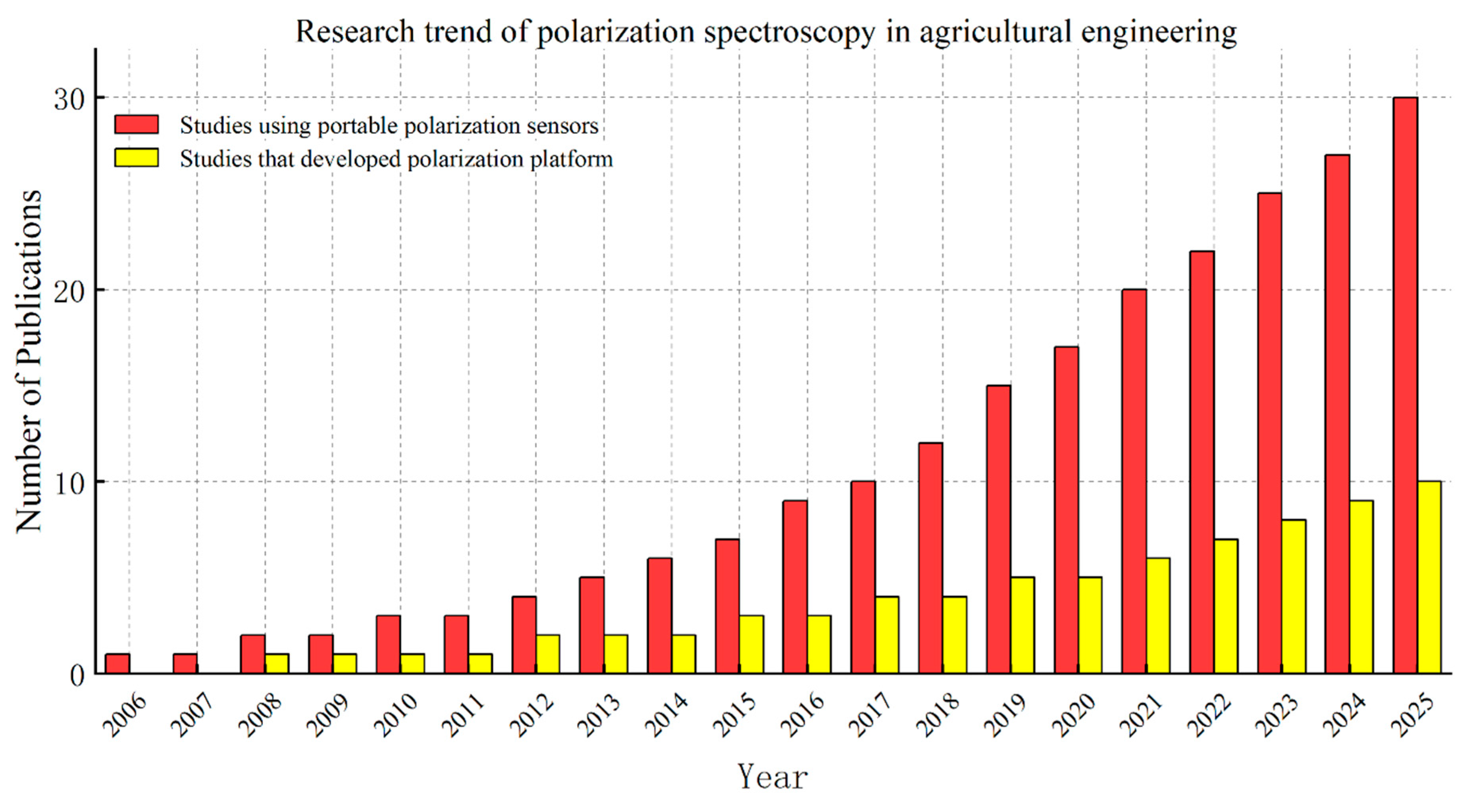

1. Introduction

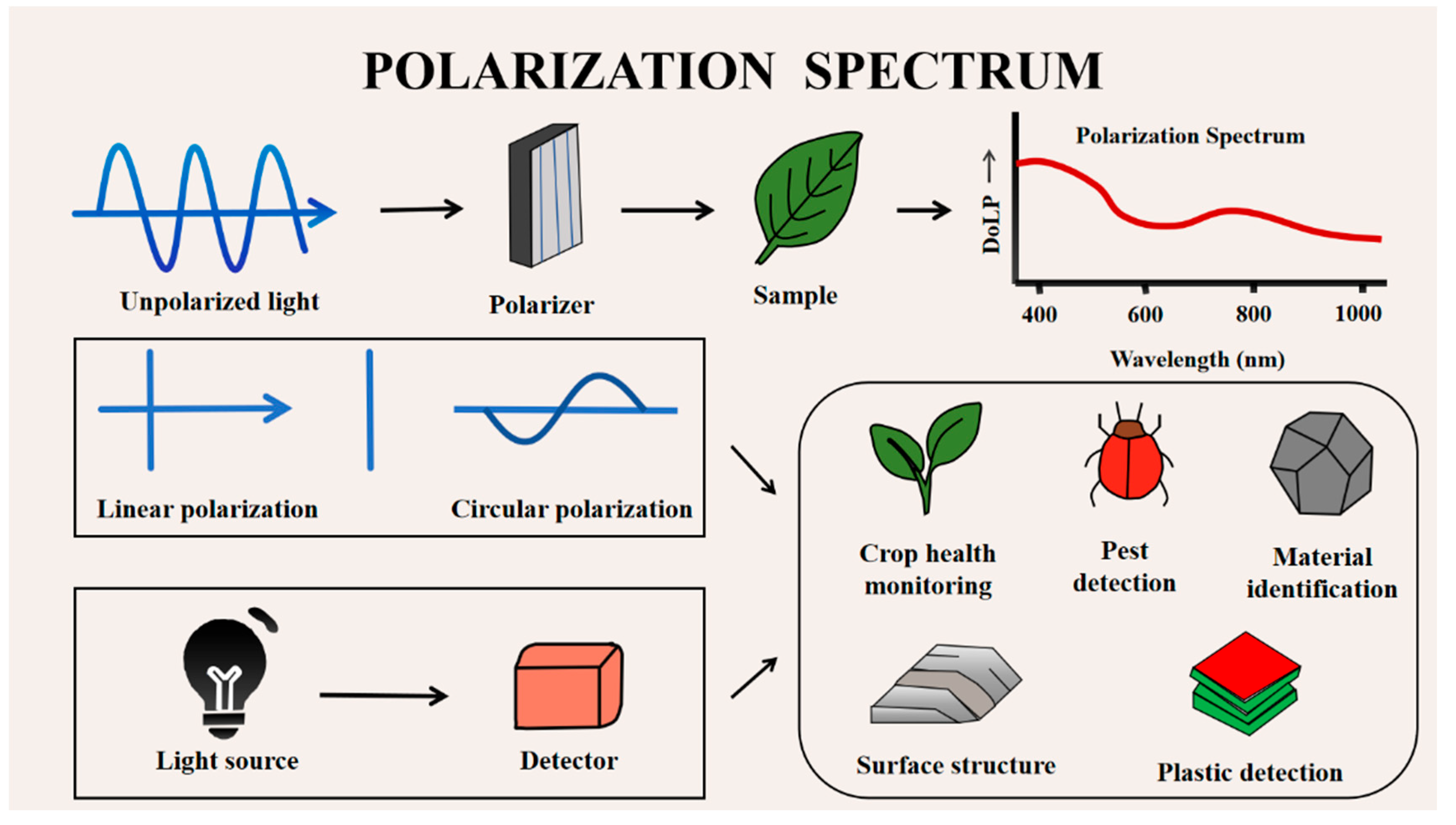

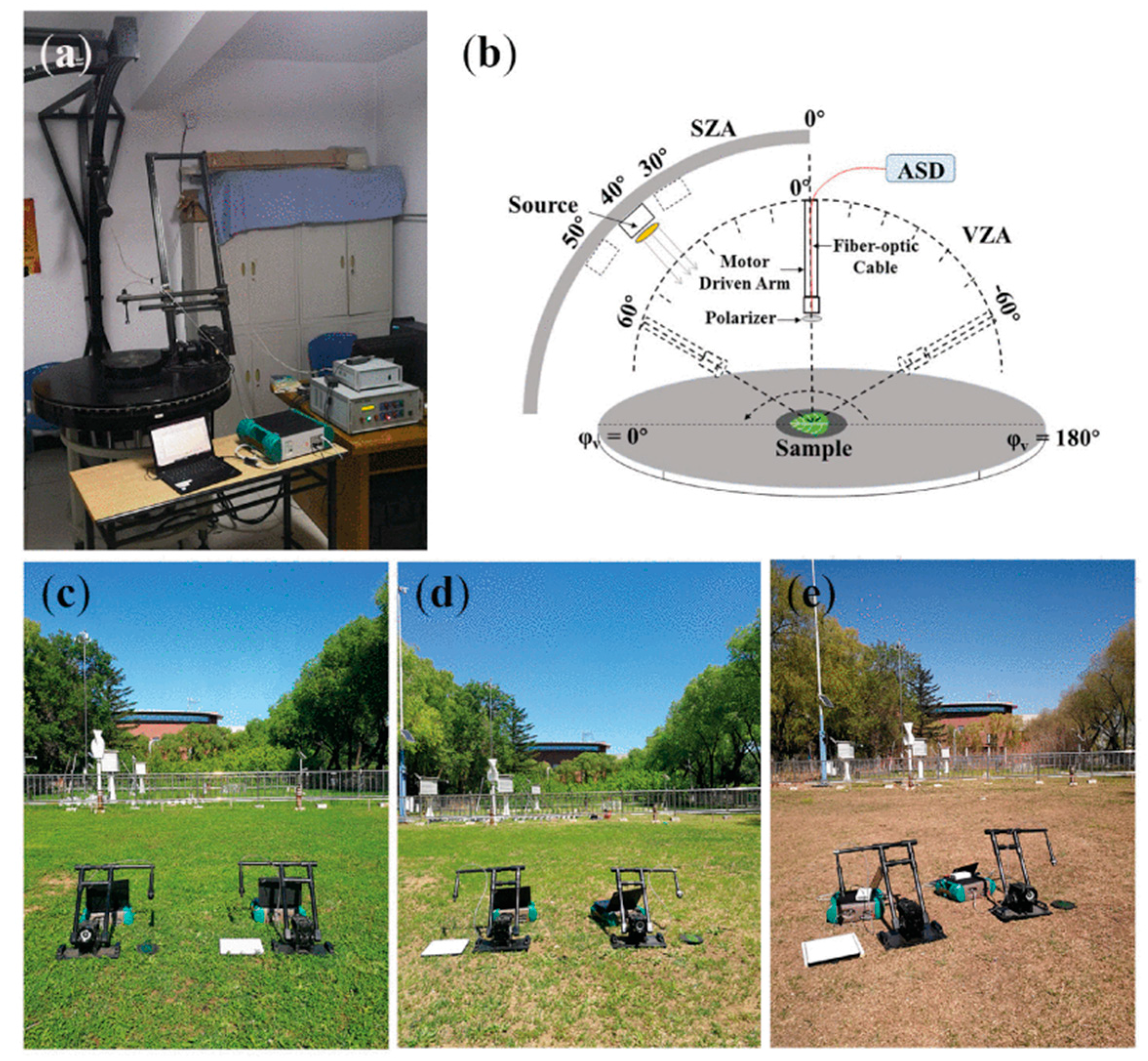

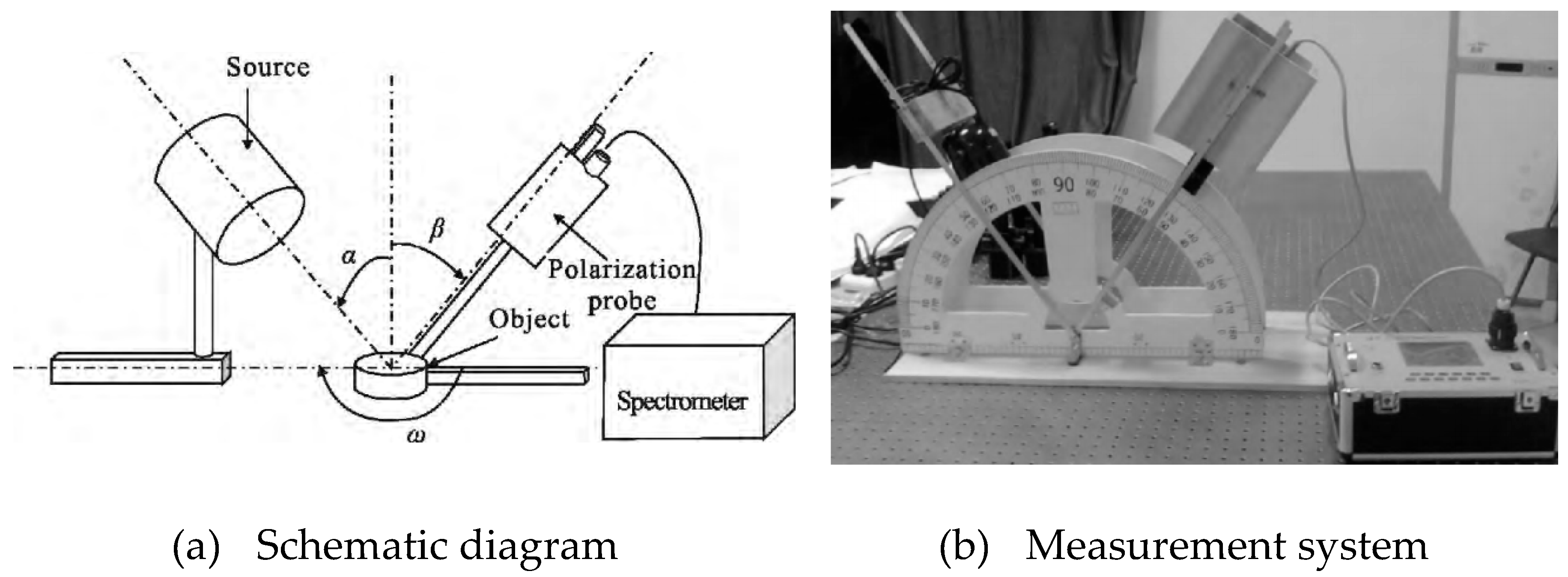

2. The Principle and Advantages of Polarization Spectroscopy Analysis Technology

2.1. Stokes Parameters

2.2. Polarization Degree

2.3. Polarization Angle

| application area | Stokes parameter | degree of polarization | polarizing angle |

| Crop health monitoring | Chlorophyll content [54], disease identification [55] | disease detection [38] | Seed germination test [56] |

| Soil quality assessment | Soil moisture content [57] | Soil moisture [58] | Soil pollution [59] |

| Agricultural product maturity testing | Fruit maturity [60] | Maturity, freshness [61] | Surface condition of fruit [62] |

| Food quality testing | Pig's egg quality [63] | Classification of vegetable oils [64] | Quality inspection [50] |

2.4. Differences and Advantages Between Polarized Spectroscopy and Traditional Spectroscopy (Visible Light, Near Infrared, etc.) in Detection Ability

2.4.1. The Difference Between Polarization Spectrum Analysis Technology and Other Typical Nondestructive Testing Technologies

2.4.2. Advantages of Polarization Spectrum Analysis Technology

- 1). High detection sensitivity and revealing microscopic characteristics

- 2). Enhance contrast and anti-interference

- 3). Enhance the ability of early diagnosis

- 4). Comprehensive information fusion

2.4.3. Classification of Polarization Spectroscopy Analysis Techniques

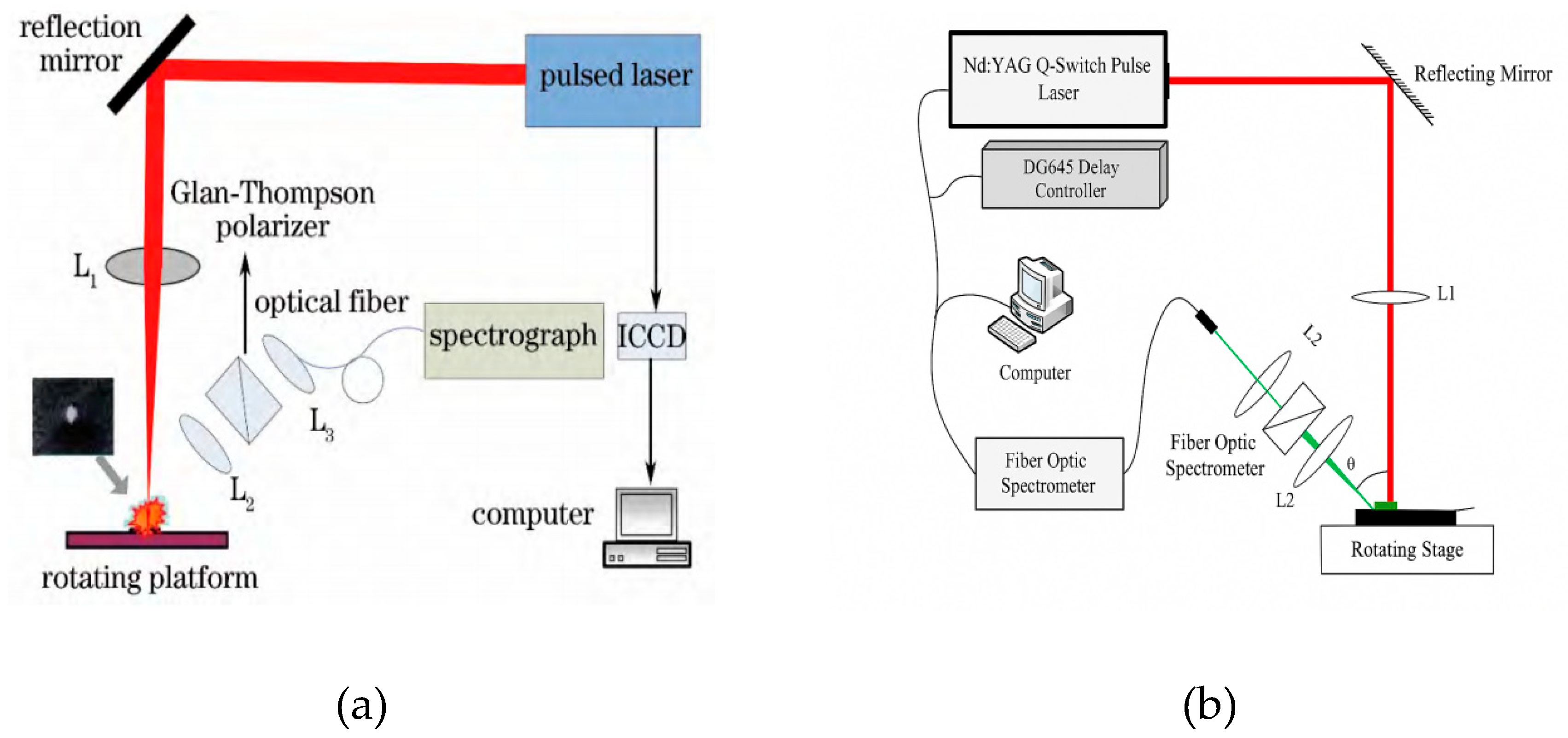

3. Application in Crop Health and Disease Detection

3.1. Chlorophyll Content Monitoring

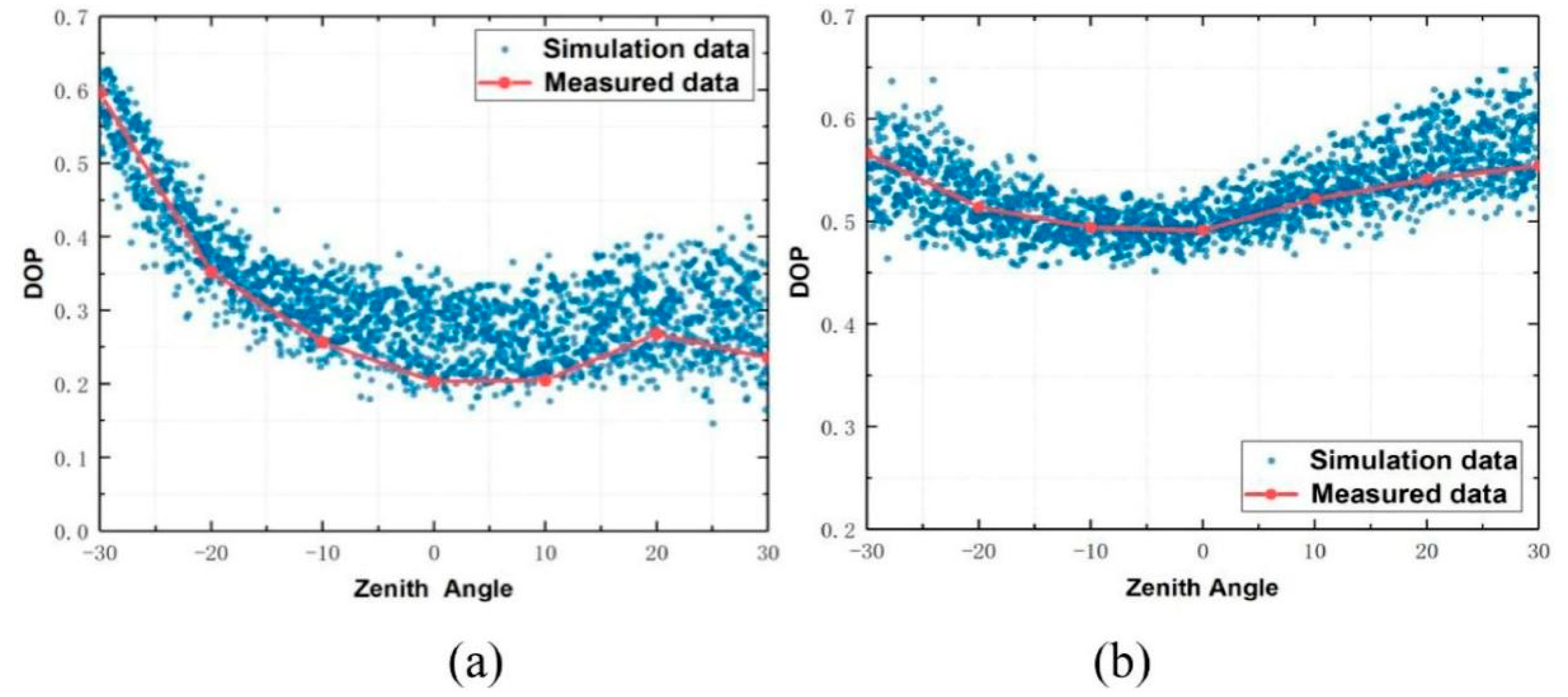

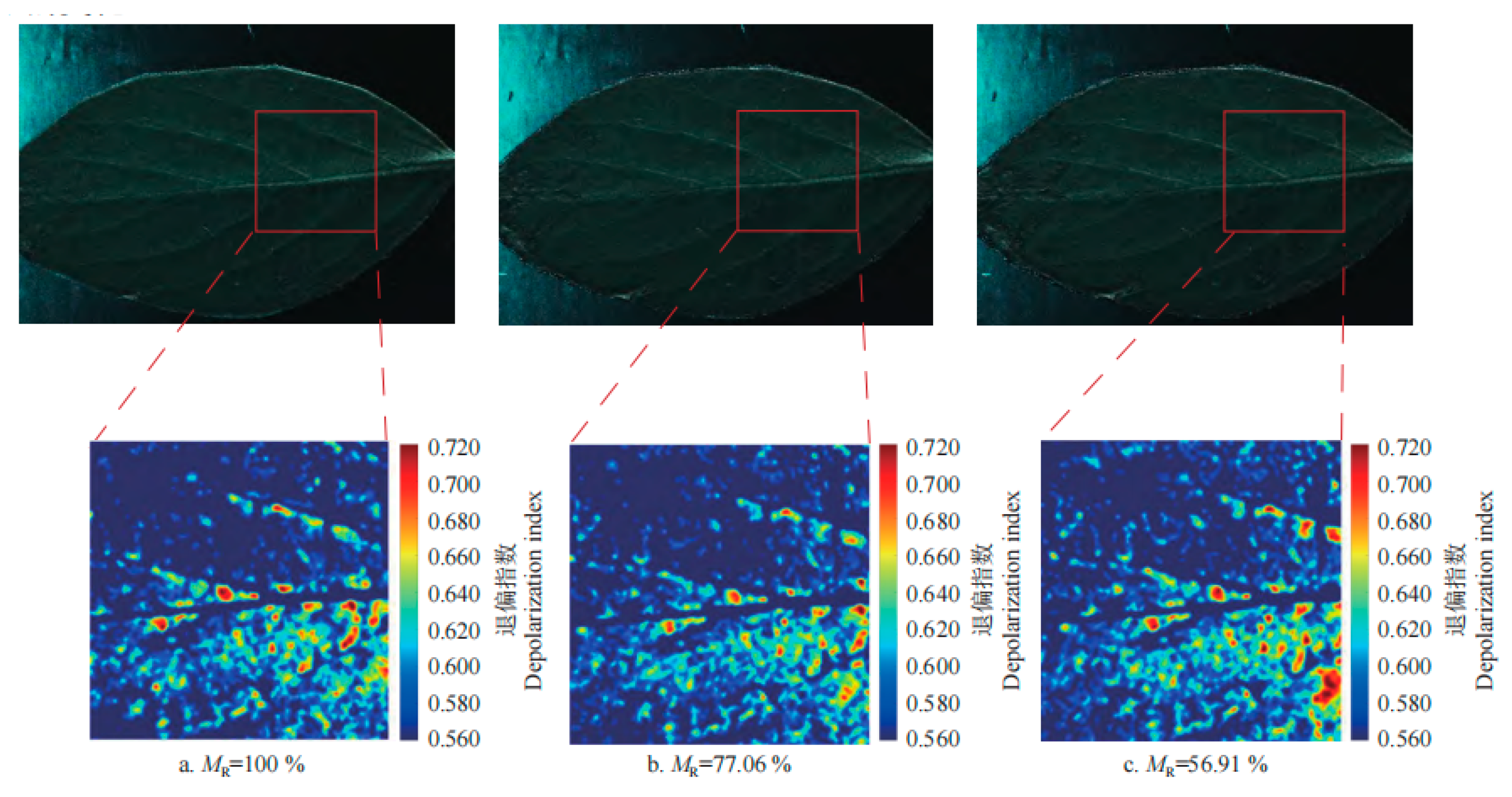

3.2. Leaf Moisture Detection

3.3. Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium Content Detection

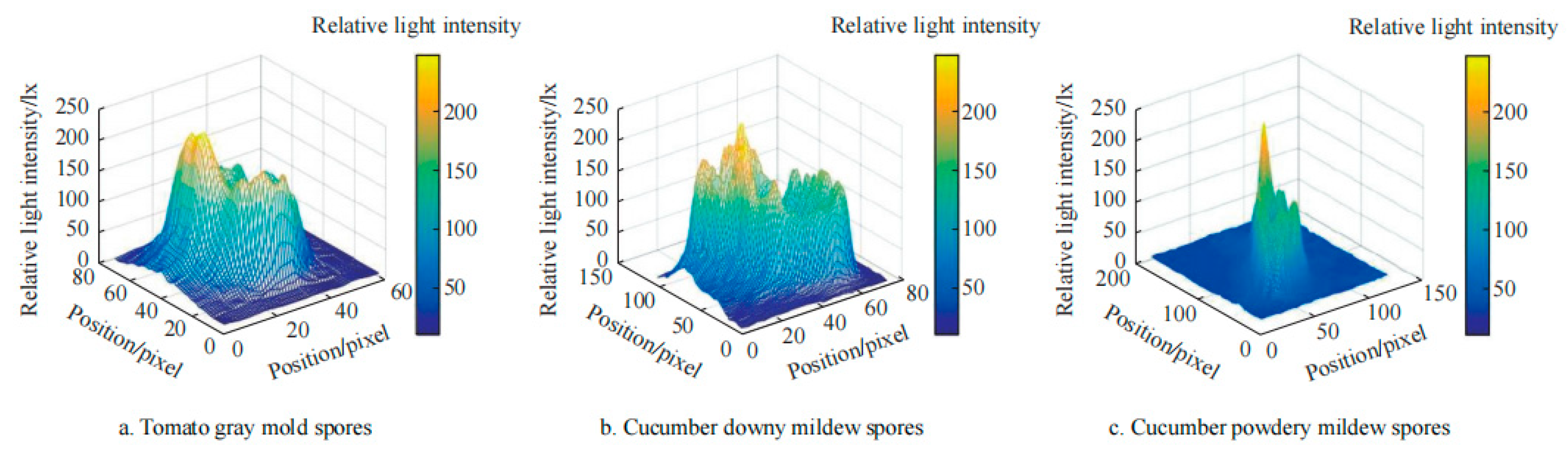

3.4. Identification and Monitoring of Pests and Diseases

4. Non-Destructive Testing of Quality of Agricultural Products and Seeds

4.1. Quality Testing of Agricultural Products

| Sample | Research contents | Research technique | Finding | Reference |

| Winter jujube in southern Xinjiang | Improve spectral inversion accuracy under complex outdoor conditions | Collected 900–1750 nm multi-polarization spectral data; corrected using four BPDF models; modeled with CARS-PLS | Rp improved by 10–30%; proportion of models with RPIQ > 2 increased from 40% to 60%; Litvinov and Xie–Cheng models performed best | [110] |

| Corn and five weeds | To explore the feasibility of using polarization spectroscopy to identify crops and weeds | The imaging spectrometer FISS-P with a polarization filter was used to collect images, analyze the spectral response and identify the model accuracy | The overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient of the recognition model are over 90%, and the highest accuracy is achieved when 0° polarization is applied | [109] |

| pulse crops | The design of a polarization detection system based on aperture imaging is designed to extract characteristics of beans | A polarization imaging detection system was built to carry out imaging experiments on red beans | The system based on simultaneous polarization imaging can highlight the detailed features of the target, show the surface defects of beans and other characteristics, and improve the accuracy of target sorting | [87] |

| nectarine | Non-destructive bruise detection of nectarines using polarization imaging | Collected 4-angle polarization images; built ResNet-G18 (ResNet-18 + Ghost) | Accuracy: 96.21%, TPR: 97.69%, Detection time: 17.32 ms | [62] |

4.2. Seed Nondestructive Testing

5. Soil and Environmental Monitoring

5.1. Soil Moisture

| Soil type | Theoretical principle | Research objectives | Measure the band | Humidity range | Application condition | Key findings | Reference |

| Red soil (Guilin, Guangxi) | Stokes vector method was used to analyze the variation of polarization degree with humidity directly | The relationship between polarization spectrum and soil moisture was explored to assist traditional hyperspectral remote sensing | Mainly in 500-700nm | 0%–26% | Medium and high humidity (> 15%) is more suitable | When the humidity is high, the polarization degree is positively correlated with the humidity, which can reach 0.98 | [120] |

| yellow brown earth | Geometrical optics, establish the relationship between refractive index and humidity | The semi-empirical model of soil polarization reflection was established to quantitatively invert soil moisture | Visible spectrum | 0%–33.4% | Medium to high humidity | The inverse humidity error is 4.88%, and the minimum model error can be 1.16% | [121] |

| Red soil (Guangxi) | Stokes vector and Mueller matrix theory are used to analyze the polarization degree variation in different bands | The feasibility of measuring soil moisture by polarization characteristics in visible/near infrared bands was verified | Visible to near-infrared bands (600-800 nm) | 0%–35% | The effect is best in the humidity range of 14%-30%, and the effect is poor in low humidity or saturated humidity | The polarization is linearly related to the humidity within the range of 14%-30%, and the standard deviation is less than 3% | [119] |

5.2. Farmland Pollution Detection

5.3. Underwater Research

6. The Combination of Polarized Spectroscopy with Other Technologies

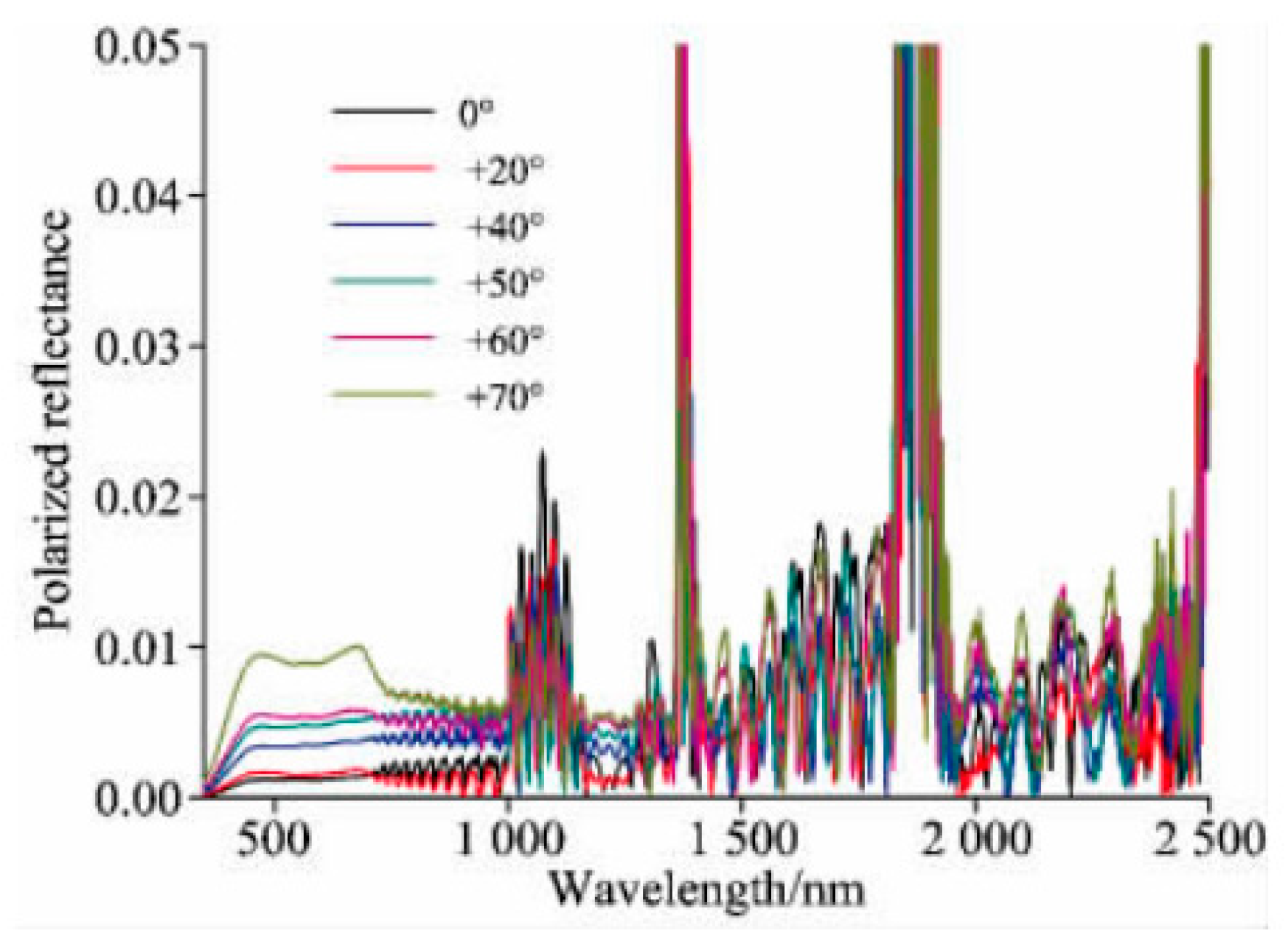

6.1. Polarization and Hyperspectral Combination

| Sample | Purpose of research | Key technology/parameter | Experimental equipment and methods | Main data processing | Main conclusion | Reference |

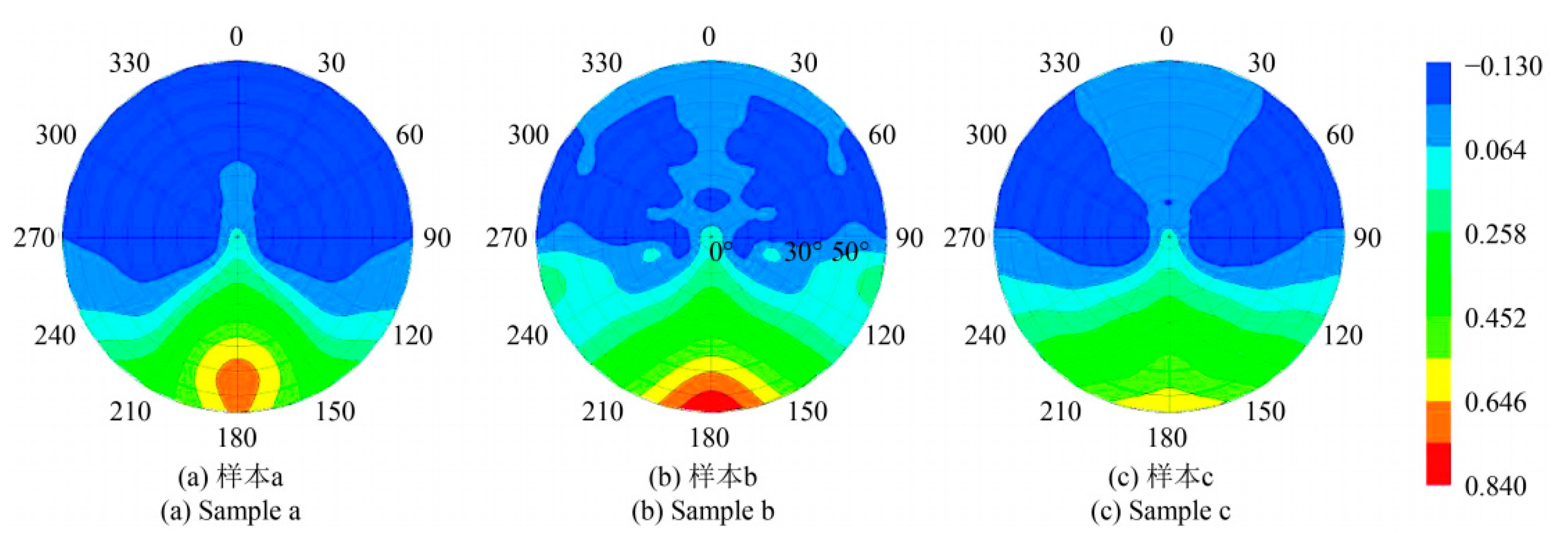

| Farmland soil in northeast China | Relationship between polarization reflection and soil fertility | Polarized reflectance ratio, azimuth, zenith Angle, multi-angle polarization spectrum measurement | Field sampling + laboratory multi-angle polarization hyperspectral measurement | Polarization reflection ratio calculation and correlation analysis between polarization parameters and fertility index | Polarized reflectance ratio is negatively correlated with fertility | [138] |

| Smooth leaves (mulberry, camellia, photinia) | Relationship between polarization characteristics and chlorophyll content | DOP (polarization degree), Rmax, Rmin, polarization reflectivity | Multi-angle platform + polarizer + ASD spectrometer + SPAD chlorophyll measurement | The relationship between DOP and chlorophyll was modeled and analyzed, and the nonlinear fitting and accuracy were evaluated | The correlation between DOP and chlorophyll was the highest | [139] |

| Dry plants and bare soil (8 species) | Distinguish between dry plants with similar spectra and bare soil | Spectral-HOG, Spectral-E and hierarchical clustering | NENULGS platform, ASD FS3 hyperspectral instrument, polarizing mirror | EMD denoising, feature extraction and cluster analysis | The combined features can distinguish all 8 categories of targets | [140] |

| Spider plant, pothos, tiger lily | The variation law of chlorophyll fluorescence and polarization was analyzed | LIF excitation, F685/F740 ratio and polarization modeling | Multi-angle fluorescence platform, AvaSpec spectrometer, laser | Regression analysis, polar coordinate drawing, correlation modeling | Fluorescence and polarization are significantly affected by Angle, and the modeling effect is good | [142] |

6.2. Polarization and Multispectral Combination

6.3. Polarization and Fluorescence Combination

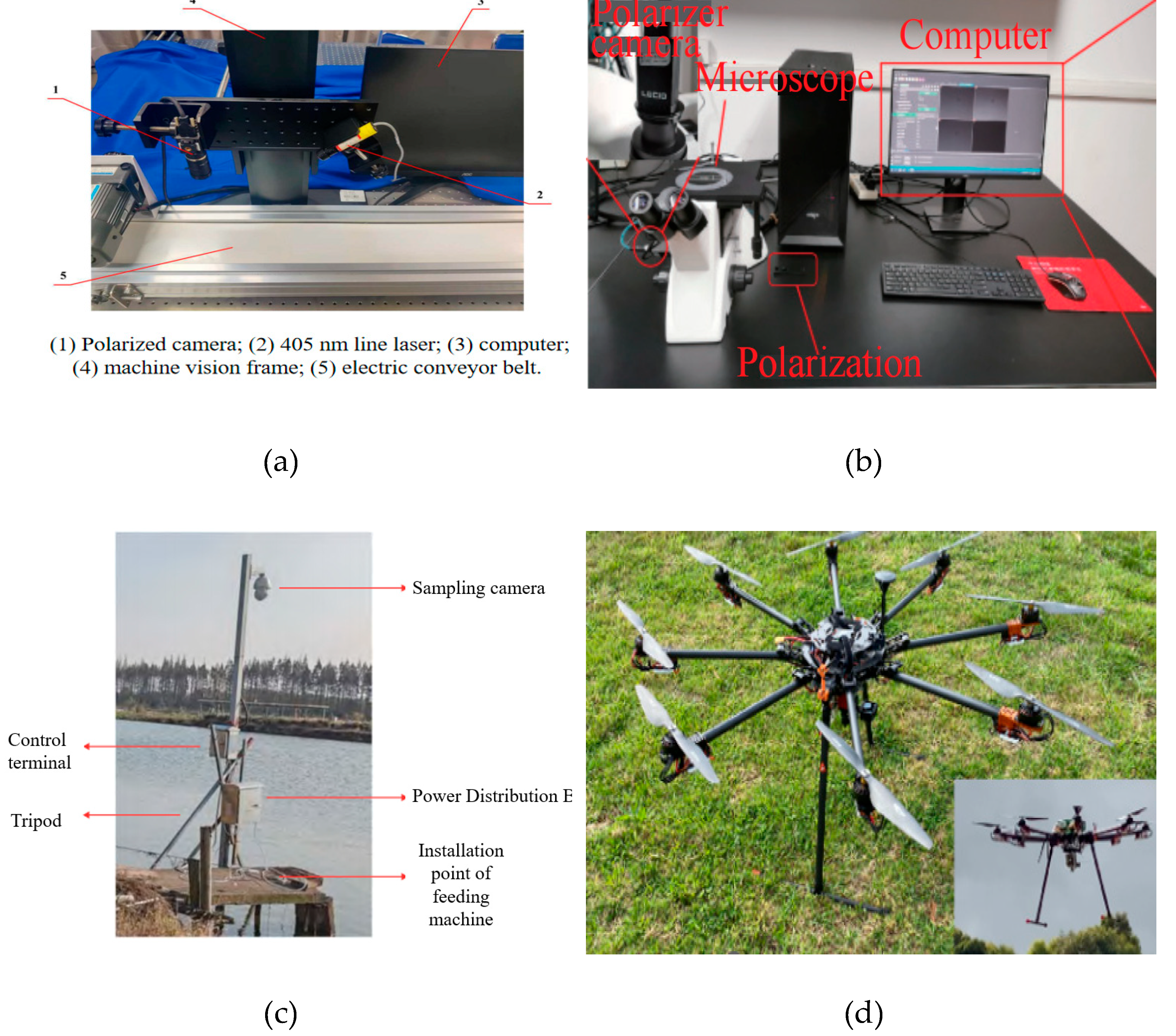

7. Other Applications in Agricultural Engineering

7.1. Pesticide Residue Detection

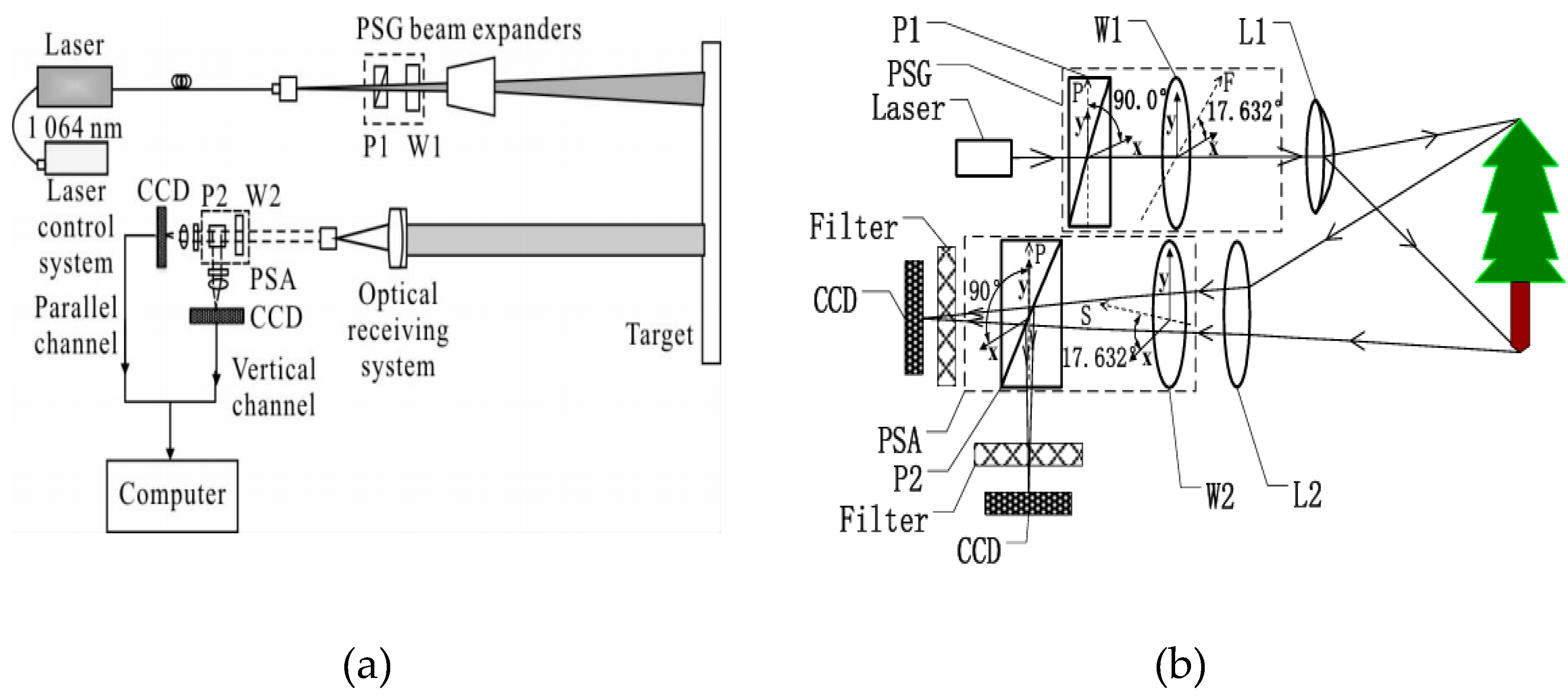

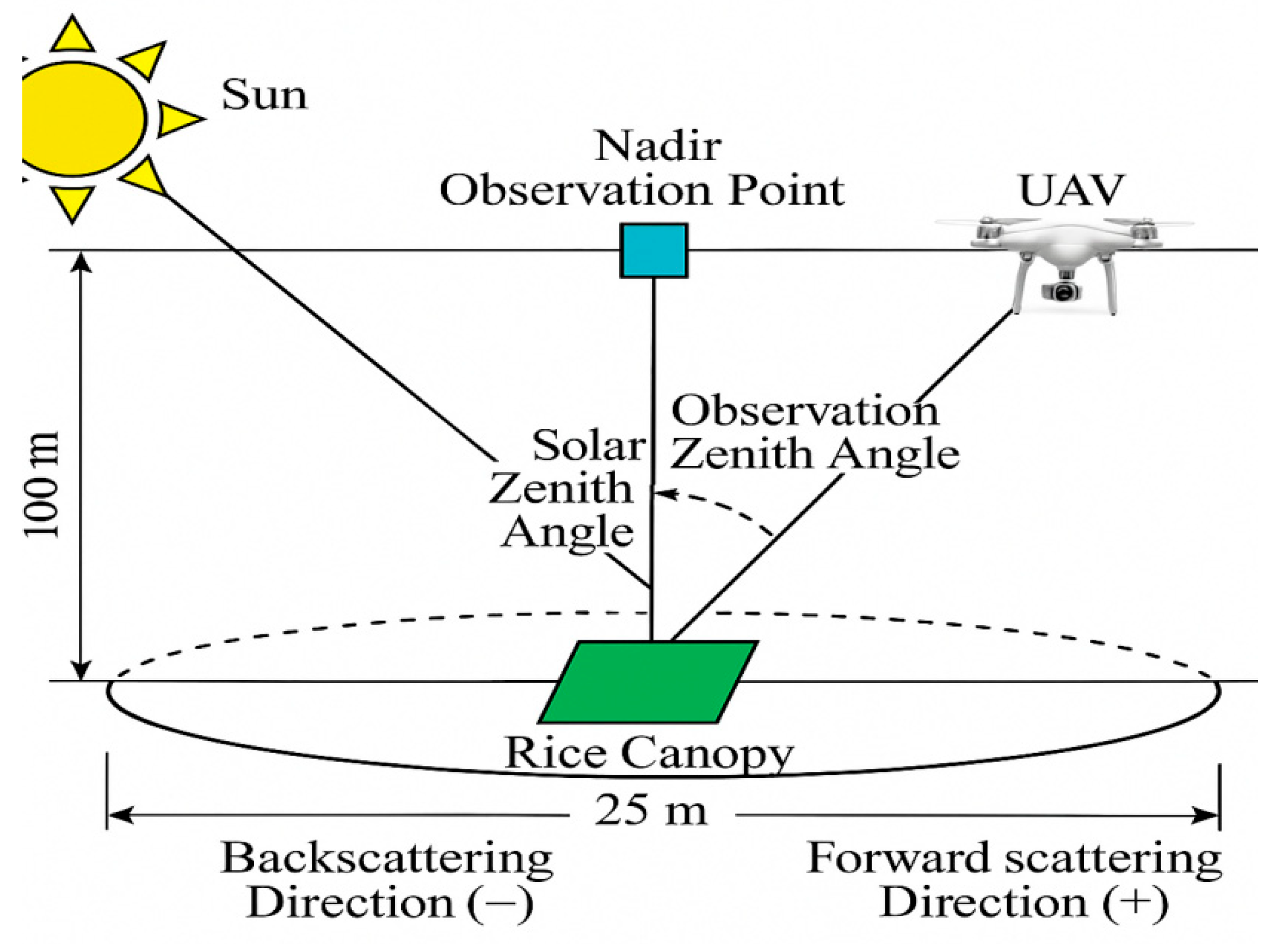

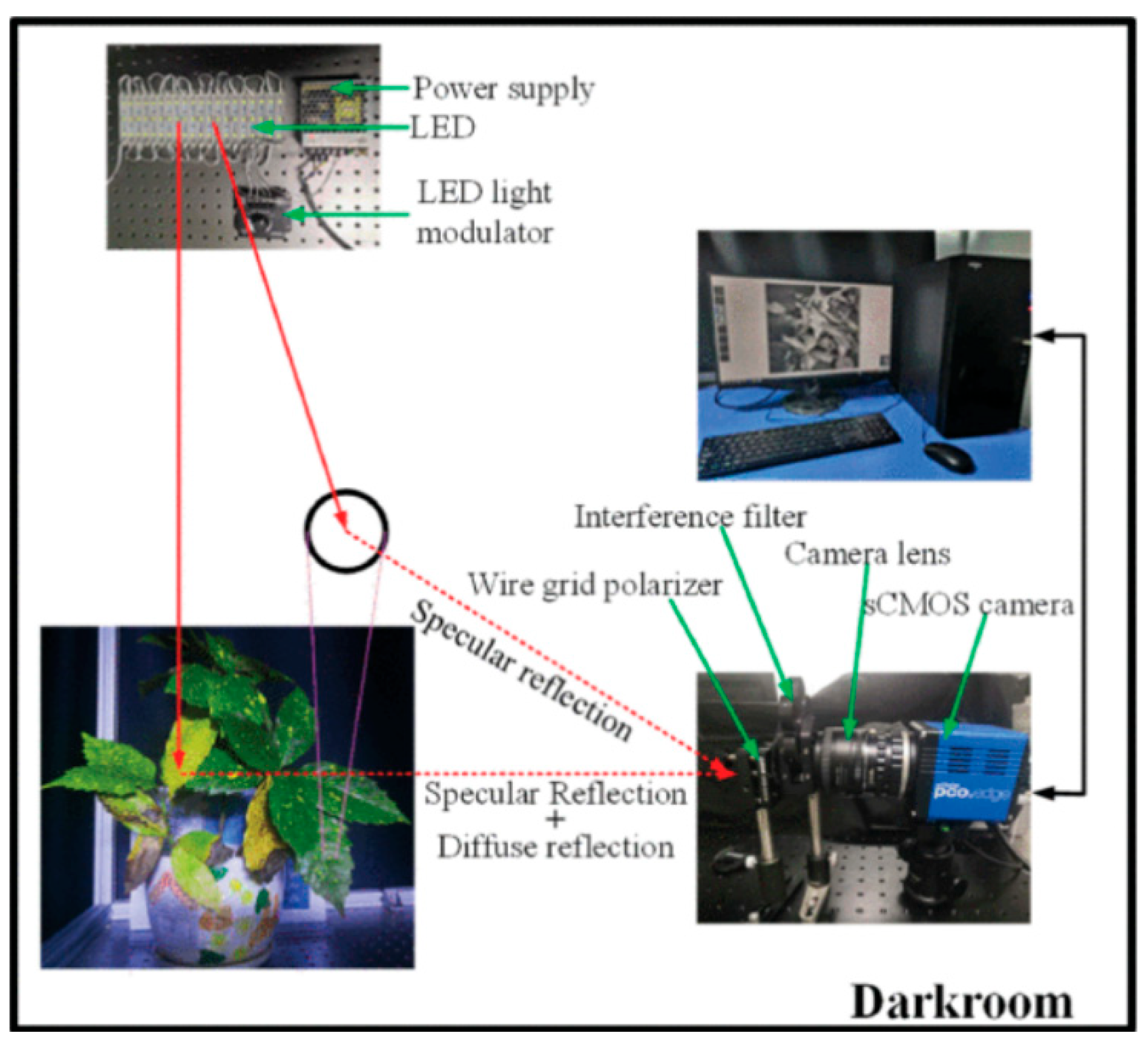

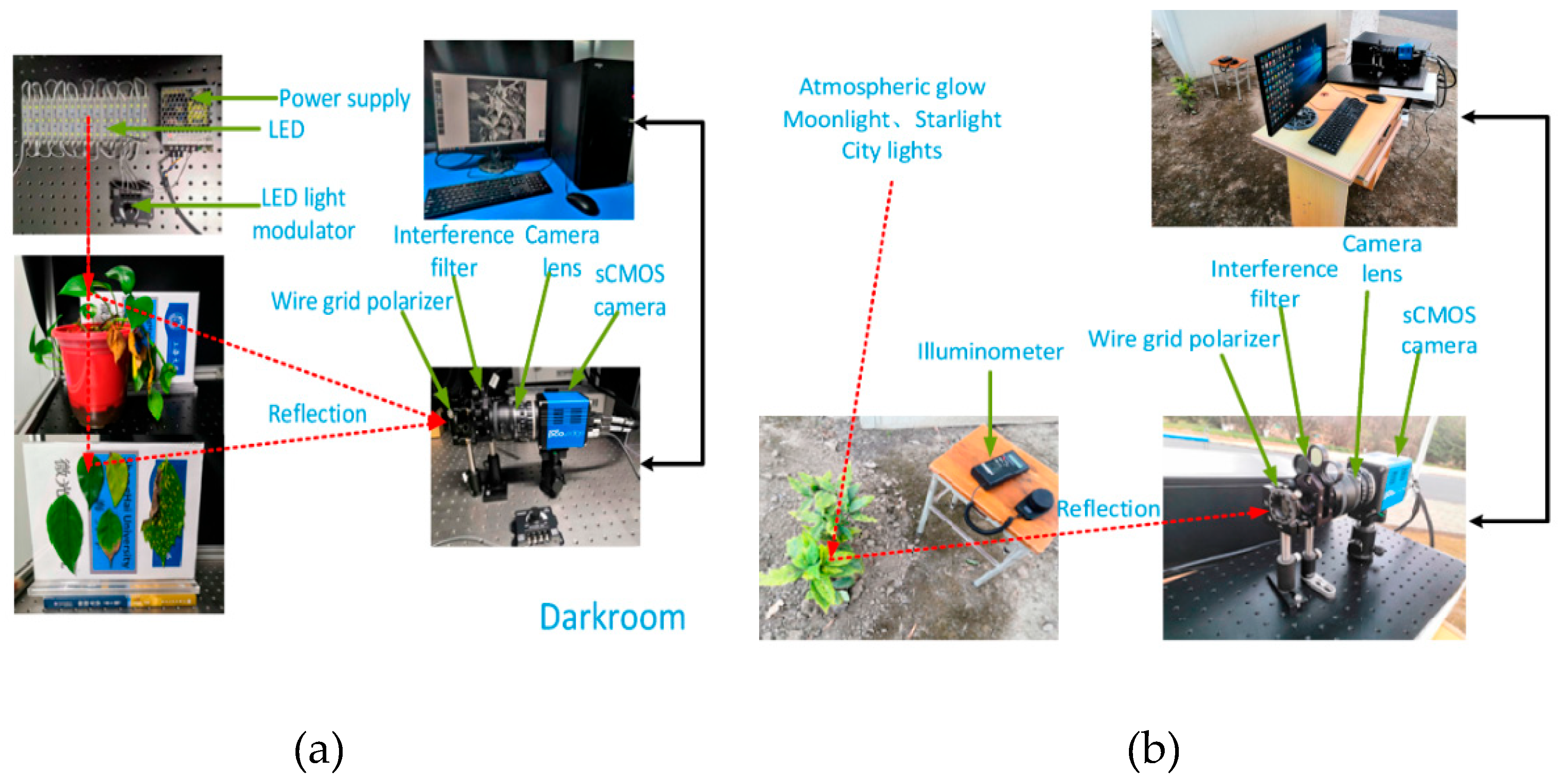

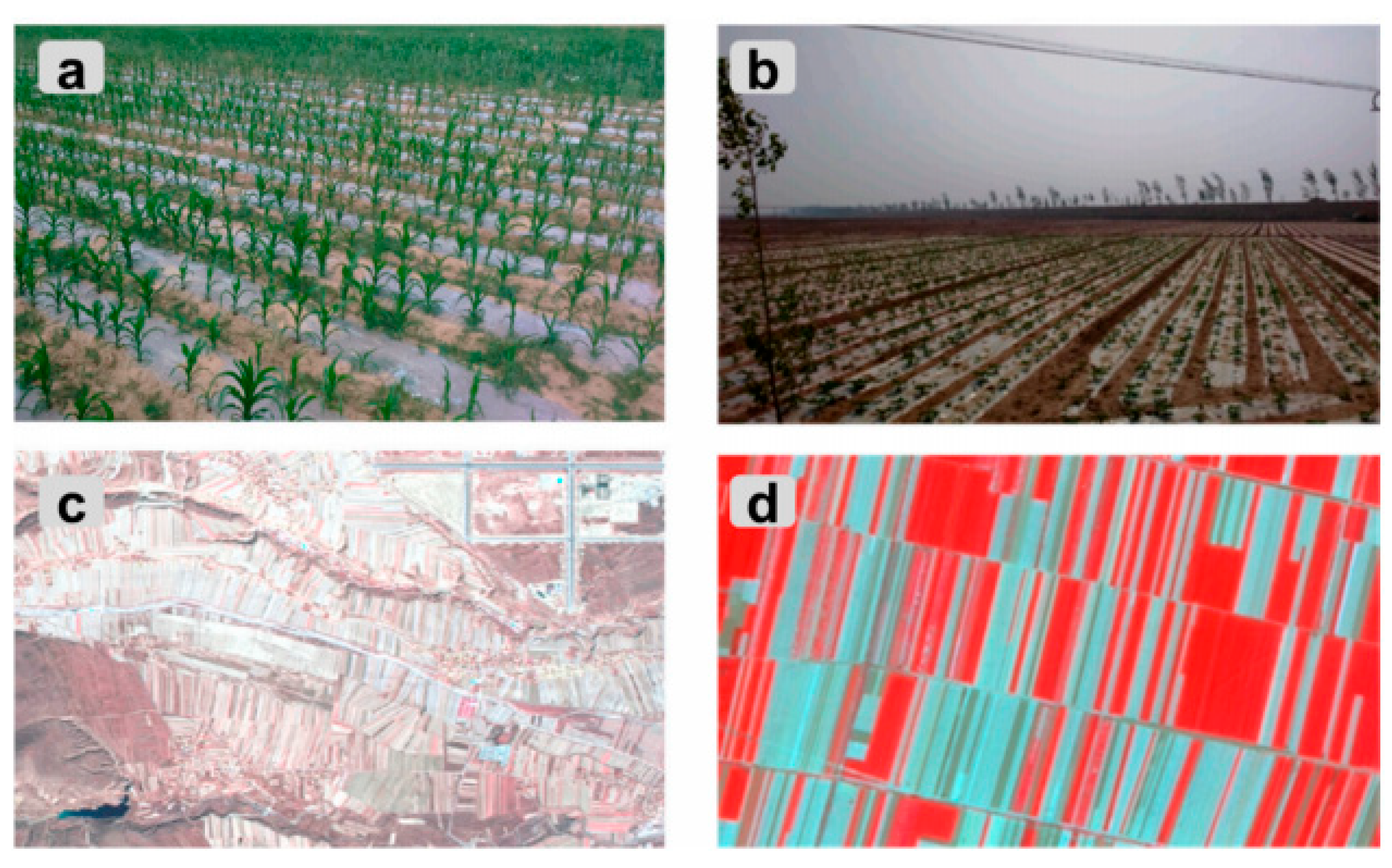

7.2. Application of Polarization Remote Sensing in Agriculture

7.3. Research on Dehazing Enhancement and Image Clarity

8. Development Trend

Acknowledgments

References

- Kumari, R., Kalpana Suman, S. Karmakar, V. Mishra, Sameer Gunjan Lakra, Gunjan Kumar Saurav, and B. K. Mahto. "Regulation and Safety Measures for Nanotechnology-Based Agri-Products." Frontiers in Genome Editing 5 (2023).

- Lee, Jaenam, and Hyungjin Shin. "Agricultural Reservoir Operation Strategy Considering Climate and Policy Changes." Sustainability 14, no. 15 (2022): 9014.

- Chamara, Nipuna, Md Didarul Islam, Geng Frank Bai, Yeyin Shi, and Yufeng Ge. "Ag-Iot for Crop and Environment Monitoring: Past, Present, and Future." Agricultural systems 203 (2022): 103497.

- Xuan, Guantao, Chong Gao, and Yuanyuan Shao. "Spectral and Image Analysis of Hyperspectral Data for Internal and External Quality Assessment of Peach Fruit." Spectrochimica acta part A: molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy 272 (2022): 121016.

- Xu, Sai, Hanting Wang, Xin Liang, and Huazhong Lu. "Research Progress on Methods for Improving the Stability of Non-Destructive Testing of Agricultural Product Quality." Foods 13, no. 23 (2024): 3917.

- Sun, Zhaoxiang, Bin Li, Akun Yang, and Yande Liu. "Detection the Quality of Pumpkin Seeds Based on Terahertz Coupled with Convolutional Neural Network." Journal of Chemometrics 38, no. 7 (2024): e3547.

- WANG, Xuejiao, Yuan XUE, Quan ZHANG, Jiawen YUAN, Longhua LI, Chi WU, and Zhenjiang LIU. "Research Progress on the Application of Manganese-Based Nanoenzyme in the Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticide Residues." Chinese Journal of Pesticide Science 27, no. 2 (2025): 207–20.

- Wen, Jing, Guoqian Xu, Ang Zhang, Wen Ma, and Gang Jin. "Emerging Technologies for Rapid Non-Destructive Testing of Grape Quality: A Review." Journal of Food Composition & Analysis 133, no. 000 (2024): 13.

- Lacotte, Virginie, Sergio Peignier, Marc Raynal, Isabelle Demeaux, François Delmotte, and Pedro da Silva. "Spatial–Spectral Analysis of Hyperspectral Images Reveals Early Detection of Downy Mildew on Grapevine Leaves." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 17 (2022): 10012.

- Kim, Jongyoon, Yu Kyeong Shin, Yunsu Nam, Jun Gu Lee, and Ji Hoon Lee. "Optical Monitoring of the Plant Growth Status Using Polarimetry." Scientific Reports.

- Khan, Zohaib, Hui Liu, Yue Shen, and Xiao Zeng. "Deep Learning Improved Yolov8 Algorithm: Real-Time Precise Instance Segmentation of Crown Region Orchard Canopies in Natural Environment." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 224 (2024): 109168.

- Liu, Xiaoyang, Weikuan Jia, Chengzhi Ruan, Dean Zhao, Yuwan Gu, and Wei Chen. "The Recognition of Apple Fruits in Plastic Bags Based on Block Classification." Precision agriculture 19, no. 4 (2018): 735–49.

- Xu, Sizhe, Xingang Xu, Qingzhen Zhu, Yang Meng, Guijun Yang, Haikuan Feng, Min Yang, Qilei Zhu, Hanyu Xue, and Binbin Wang. "Monitoring Leaf Nitrogen Content in Rice Based on Information Fusion of Multi-Sensor Imagery from Uav." Precision agriculture 24, no. 6 (2023): 2327–49. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Weiping, Mohamed Abdel-Basset, Ibrahim Alrashdi, and Hossam Hawash. "Next Generation of Computer Vision for Plant Disease Monitoring in Precision Agriculture: A Contemporary Survey, Taxonomy, Experiments, and Future Direction." Information science 665, no. 000 (2024): 30.

- Rui, Yu-Kui, Shu-Zhen Xin, and Jun-Hui Li. "Application of Nirs to Detecting Total N of Cucumber Leaves Growing in Greenhouse." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 31, no. 8 (2011): 2114–16.

- Tan, Baohua, Wenhao You, Chengxu Huang, Tengfei Xiao, Shihao Tian, Lina Luo, and Naixue Xiong. "An Intelligent near-Infrared Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy Scheme for the Non-Destructive Testing of the Sugar Content in Cherry Tomato Fruit." Electronics 11, no. 21 (2022): 3504.

- Lin, Fenfang, Sen Guo, Changwei Tan, Xingen Zhou, and Dongyan Zhang. "Identification of Rice Sheath Blight through Spectral Responses Using Hyperspectral Images." Sensors 20, no. 21 (2020): 6243.

- Oprisescu, Serban, Radu-Mihai Coliban, and Mihai Ivanovici. "Polarization-Based Optical Characterization for Color Texture Analysis and Segmentation." Pattern Recognition Letters 163 (2022): 74–81.

- Lin, Yi-Hsin, Hao-Hsin Huang, Yu-Jen Wang, Huai-An Hsieh, and Po-Lun Chen. "Image-Based Polarization Detection and Material Recognition." Optics Express 30, no. 22 (2022): 39234–43.

- Guan, Caizhong, Nan Zeng, and Honghui He. "Review of Polarization-Based Technology for Biomedical Applications." Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 18, no. 02 (2025): 2430002.

- Tukimin, Siti Nurainie, Salmah Binti Karman, Mohd Yazed Ahmad, and Wan Safwani Wan Kamarul Zaman. "Polarized Light-Based Cancer Cell Detection Techniques: A Review." IEEE Sensors Journal 19, no. 20 (2019): 9010–25.

- Zhu, Xinlong, Xiaohan Guo, Fang Kong, Farhad Banoori, Wenli Ren, Fangzheng Ding, and Yinjing Guo. "A Review of Underwater Skylight Polarization Detection." Optics & Laser Technology 192 (2025): 113505.

- Duan, Changfei, Yingjie Zhang, Peipei Li, Qiang Li, Wenbo Yu, Kai Wen, Sergei A Eremin, Jianzhong Shen, Xuezhi Yu, and Zhanhui Wang. "Dual-Wavelength Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay for Simultaneous Detection of Sulfonamides and Antibacterial Synergists in Milk." Biosensors 12, no. 11 (2022): 1053.

- Gastellu-Etchegorry, Jean Philippe, Nicolas Lauret, Tiangang Yin, Lucas Landier, Abdelaziz Kallel, Zbynek Malenovsky, Ahmad Al Bitar, Josselin Aval, Sahar Benhmida, and Jianbo Qi. "Dart: Recent Advances in Remote Sensing Data Modeling with Atmosphere, Polarization, and Chlorophyll Fluorescence." IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing (2017): 2640–49.

- Hosseini, Mehdi, and Heather McNairn. "Using Multi-Polarization C-and L-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar to Estimate Biomass and Soil Moisture of Wheat Fields." International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 58 (2017): 50–64.

- Lunagaria, Manoj M, and Haridas R Patel. "Changes in Reflectance Anisotropy of Wheat Crop during Different Phenophases." International Agrophysics 31, no. 2 (2017): 203.

- Xu, Jun-LiGobrecht, AlexiaHeran, DaphneGorretta, NathalieCoque, MarieGowen, Aoife A.Bendoula, RyadSun, Da-Wen. "A Polarized Hyperspectral Imaging System for in Vivo Detection: Multiple Applications in Sunflower Leaf Analysis." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 158 (2019).

- Sun, Zhongqiu, Di Wu, and Yunfeng Lv. "Effects of Water Salinity on the Multi-Angular Polarimetric Properties of Light Reflected from Smooth Water Surfaces." Applied Optics 61, no. 15 (2022): 4527–34.

- Li, Xiao, Zhongqiu Sun, Shan Lu, and Kenji Omasa. "A Radiative Transfer Model for Characterizing Photometric and Polarimetric Properties of Leaf Reflection: Combination of Prospect and a Polarized Reflection Function." Remote Sensing of Environment 318 (2025): 114559.

- Huang, Wenjiang, Qinying Yang, Ruiliang Pu, and Shaoyuan Yang. "Estimation of Nitrogen Vertical Distribution by Bi-Directional Canopy Reflectance in Winter Wheat." Sensors 14, no. 11 (2014): 20347–59.

- Di, Wu, and Sun Zhongqiu. "Research on Polarization Spectral Reflectance Characteristics of Vegetation Canopy Based on Field Measurements." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 37, no. 08 (2017): 2533–38. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Feizhou, Xufang Liu, Yun Xiang, Zihan Zhang, Siyuan Liu, and Lei Yan. "Estimation of Rock Characteristics Based on Polarization Spectra: Surface Roughness, Composition, and Density." Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 87, no. 12 (2021): 907–12.

- Huang, Longqian, Ruichen Luo, Xu Liu, and Xiang Hao. "Spectral Imaging with Deep Learning." Light: Science & Applications 11, no. 1 (2022): 61.

- Shen, Ying, Wenfu Lin, Zhifeng Wang, Jie Li, Xinquan Sun, Xianyu Wu, Shu Wang, and Feng Huang. "Rapid Detection of Camouflaged Artificial Target Based on Polarization Imaging and Deep Learning." IEEE Photonics Journal 13, no. 4 (2021): 1–9.

- Zuo, Chao, Jiaming Qian, Shijie Feng, Wei Yin, Yixuan Li, Pengfei Fan, Jing Han, Kemao Qian, and Qian Chen. "Deep Learning in Optical Metrology: A Review." Light: Science & Applications 11, no. 1 (2022): 39.

- Brahimi, Mohammed, Marko Arsenovic, Sohaib Laraba, Srdjan Sladojevic, and Abdelouhab Moussaoui. "Deep Learning for Plant Diseases: Detection and Saliency Map Visualisation." (2018).

- Wang, Rui, Zhi-Feng Zhang, Ben Yang, Hai-Qi Xi, Yu-Sheng Zhai, Rui-Liang Zhang, Li-Jie Geng, Zhi-Yong Chen, and Kun Yang. "Detection and Classification of Cotton Foreign Fibers Based on Polarization Imaging and Improved Yolov5." Sensors 23, no. 9 (2023): 4415.

- Wang, Yafei, Ning Yang, Guoxin Ma, Mohamed Farag Taha, Hanping Mao, Xiaodong Zhang, and Qiang Shi. "Detection of Spores Using Polarization Image Features and Bp Neural Network." International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 17, no. 5 (2024): 213–21. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Shijing, Xueying Tu, and Cheng Qian. "Classification of Grass Carp Feeding Status Based on Inter-Frame Optical Flow Features and Improved Rnn." Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica 46, no. 06 (2022): 914–21. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Soon Hock, Blake Allan, Daniel Ierodiaconou, Vijayakumar Anand, Alexander Babanin, and Saulius Juodkazis. "Drone Polariscopy—Towards Remote Sensing Applications." Engineering Proceedings 11, no. 1 (2021): 46.

- Xu, Chenyi, YANG Jiaxin, JIN Zhongyu, and YU Fenghua. "Research Progress in Polarization Spectroscopy in the Inversion of Agronomic Parameters of Field Crops." Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis 36, no. 11 (2024): 2596. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yong, Yuqing Su, Xiangyu Sun, Xiaorui Hao, Yanping Liu, Xiaolong Zhao, Hongsheng Li, Xiushuo Zhang, Jing Xu, and Jingjing Tian. "Principle and Implementation of Stokes Vector Polarization Imaging Technology." Applied Sciences 12, no. 13 (2022): 6613.

- Bi, Hongru, Wei Chen, and Yi Yang. "Extracting Illuminated Vegetation, Shadowed Vegetation and Background for Finer Fractional Vegetation Cover with Polarization Information and a Convolutional Network." Precision agriculture 25, no. 2 (2024): 1106–25.

- Kulchin, Yuriy N, Sergey O Kozhanov, Alexander S Kholin, Vadim V Demidchik, Evgeny P Subbotin, Yuriy V Trofimov, Kirill V Kovalevsky, Natalia I Subbotina, and Andrey S Gomolsky. "The Ability of Plants Leaves Tissue to Change Polarization State of Polarized Laser Radiation." Brazilian Journal of Botany 47, no. 2 (2024): 463–72.

- Wang, Wei. "Statistical Properties of the Integrated Stokes Parameters of Polarization Speckle or Partially Polarized Thermal Light." Journal of the optical society of america a 40, no. 5 (2023): 914–24.

- Kuratsuji, Hiroshi, and Satoshi Tsuchida. "Evolution of the Stokes Parameters, Polarization Singularities, and Optical Skyrmion." Physical Review A 103, no. 2 (2021): 023514.

- Yi, Jia, Huilin Jiang, and Yong Tan. "The Detection of Soybean Bacterial Blight Based on Polarization Spectral Imaging Techniques." Agronomy 15, no. 1 (2024): 50.

- Cheng, Qian, Ying-min Wang, and Ying-luo Zhang. "Analysis of the Polarization Characteristics of Scattered Light of Underwater Suspended Particles Based on Mie Theory." Optoelectronics Letters 17, no. 4 (2021): 252–56.

- Xu, Xiang, Zenghui Liu, and Zhijian Chen. "Detecting Early Changes in Plant Leaf Moisture Content Using Polarization Imaging." Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 39, no. 11 (2023): 175–82. [CrossRef]

- Takruri, Maen, Abubakar Abubakar, Noora Alnaqbi, Hessa Al Shehhi, Abdul-Halim M Jallad, and Amine Bermak. "Dofp-Ml: A Machine Learning Approach to Food Quality Monitoring Using a Dofp Polarization Image Sensor." IEEE Access 8 (2020): 150282–90.

- Shibayama, Michio, Toshihiro Sakamoto, and Akihiko Kimura. "A Multiband Polarimetric Imager for Field Crop Survey:―Instrumentation and Preliminary Observations of Heading-Stage Wheat Canopies―." Plant Production Science 14, no. 1 (2011): 64–74.

- He, Qingyi, Juntong Zhan, Xuanwei Liu, Chao Dong, Dapeng Tian, and Qiang Fu. "Multispectral Polarimetric Bidirectional Reflectance Research of Plant Canopy." Optics and Lasers in Engineering 184 (2025): 108688.

- Kim, Yong-Hyun, Duk-Jin Kim, Jae-Hong Oh, and Yong-Il Kim. "Paddy Field Extraction Using Beta and Polarization Orientation Angles." Paper presented at the 2015 IEEE 5th Asia-Pacific Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar (APSAR) 2015.

- Meng, Xia, Donghui Xie, and Yan Wang. "Experimental Study on Influencing Factors of Multi-Angle Polarized Spectral Characteristics of Plant Leaves." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 34, no. 03 (2014): 619–24. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Carla, Enrique Garcia-Caurel, Teresa Garnatje, Mireia Serra i Ribas, Jordi Luque, Juan Campos, and Angel Lizana. "Polarimetric Observables for the Enhanced Visualization of Plant Diseases." Scientific Reports 12, no. 1 (2022): 14743.

- Cheng, Yuqiong, Wei Lu, and Delin Hong. "Detection Method for Rice Seed Germination Rate Based on Continuous Polarized Spectroscopy." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 36, no. 07 (2016): 2200–06. [CrossRef]

- Germann, Peter, Andreas Helbling, and Tomaso Vadilonga. "Rivulet Approach to Rates of Preferential Infiltration." Vadose Zone Journal 6, no. 2 (2007): 207–20.

- McNairn, Heather, Amine Merzouki, Yifeng Li, George Lampropoulos, Weikai Tan, Jarrett Powers, and Matthew Friesen. "Retrieval of Field-Scale Soil Moisture Using Compact Polarimetry: Preparing for the Radarsat-Constellation." Paper presented at the IGARSS 2018-2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 2018.

- Kong, Zheng, Jiheng Yu, Zhenfeng Gong, Dengxin Hua, and Liang Mei. "Visible, near-Infrared Dual-Polarization Lidar Based on Polarization Cameras: System Design, Evaluation and Atmospheric Measurements." Optics Express 30, no. 16 (2022): 28514–33.

- Sarykar, Mukul, and Maher Assaad. "Measuring Perceived Sweetness by Monitoring Sorbitol Concentration in Apples Using a Non-Destructive Polarization-Based Readout." Applied Optics 60, no. 19 (2021): 5723–34.

- Sarkar, M, N Gupta, and M Assaad. "Monitoring of Fruit Freshness Using Phase Information in Polarization Reflectance Spectroscopy." Applied Optics 58, no. 23 (2019): 6396–405.

- Yang, Yu, Liang Wang, Min Huang, Qibing Zhu, and Ruili Wang. "Polarization Imaging Based Bruise Detection of Nectarine by Using Resnet-18 and Ghost Bottleneck." Postharvest Biology and Technology 189 (2022): 111916.

- Wang, F., Y. Wen, Z. Tan, F. Cheng, and W. Yi. "Nondestructive Detecting Cracks of Preserved Eggshell Using Polarization Technology and Cluster Analysis." Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 30, no. 9 (2014): 249–55.

- Mu, Taotao, Meng, Fandong, Zhang, Yinchao, Guo, Pan, Liu, and Xiaohua. "Fluorescence Polarization Technique: A New Method for Vegetable Oils Classification." Analytical Methods 7, no. 12 (2015): 5175–79. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Yutong, Hongchun Qu, Ansong Leng, Xiaoming Tang, and Shidong Zhai. "Methods and Challenges in Computer Vision-Based Livestock Anomaly Detection, a Systematic Review." Biosystems Engineering 253 (2025): 104135.

- Gu, Haiyang, Riqin Lv, Xingyi Huang, Quansheng Chen, and Yining Dong. "Rapid Quantitative Assessment of Lipid Oxidation in a Rapeseed Oil-in-Water (O/W) Emulsion by Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy." Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 114 (2022): 104762.

- Huang, Xing-yi, Si-hui Pan, Zhao-yan Sun, Wei-tao Ye, and Joshua Harrington Aheto. "Evaluating Quality of Tomato during Storage Using Fusion Information of Computer Vision and Electronic Nose." Journal of Food Process Engineering 41, no. 6 (2018): e12832.

- Li, Yating, Jun Sun, Xiaohong Wu, Bing Lu, Minmin Wu, and Chunxia Dai. "Grade Identification of Tieguanyin Tea Using Fluorescence Hyperspectra and Different Statistical Algorithms." Journal of food science 84, no. 8 (2019): 2234–41.

- Wang, Junyi, Zhiming Guo, Caixia Zou, Shuiquan Jiang, Hesham R El-Seedi, and Xiaobo Zou. "General Model of Multi-Quality Detection for Apple from Different Origins by Vis/Nir Transmittance Spectroscopy." Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 16, no. 4 (2022): 2582–95.

- Wang, Yafei, Hanping Mao, Xiaodong Zhang, Yong Liu, and Xiaoxue Du. "A Rapid Detection Method for Tomato Gray Mold Spores in Greenhouse Based on Microfluidic Chip Enrichment and Lens-Less Diffraction Image Processing." Foods 10, no. 12 (2021): 3011.

- Li, Xu, Jingming Wu, Tiecheng Bai, Cuiyun Wu, Yufeng He, Jianxi Huang, Xuecao Li, Ziyan Shi, and Kaiyao Hou. "Variety Classification and Identification of Jujube Based on near-Infrared Spectroscopy and 1d-Cnn." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 223 (2024): 109122.

- Zheng, Yuanhao, Ying Zhou, Penghui Liu, Yingjie Zheng, Zichao Wei, Zetong Li, and Lijuan Xie. "Improving Discrimination Accuracy of Pest-Infested Crabapples Using Vis/Nir Spectral Morphological Features." Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 18, no. 10 (2024): 8755–66.

- Zhang, Xijia, Hongbin Pu, and Da-Wen Sun. "Photothermal Detection of Food Hazards Using Temperature as an Indicator: Principles, Sensor Developments and Applications." Trends in Food Science & Technology 146 (2024): 104393.

- Terentev, Anton, Viktor Dolzhenko, Alexander Fedotov, and Danila Eremenko. "Current State of Hyperspectral Remote Sensing for Early Plant Disease Detection: A Review." Sensors 22, no. 3 (2022): 757.

- Adetutu, Awosan Elizabeth, Yakubu Fred Bayo, Adekunle Abiodun Emmanuel, and Agbo-Adediran Adewale Opeyemi. "A Review of Hyperspectral Imaging Analysis Techniques for Onset Crop Disease Detection, Identification and Classification." Journal of forest and environmental science 40, no. 1 (2024): 1–8.

- Ni, Jiheng, Yawen Xue, and Jialin Liao. "Dynamic Changes and Spectrometric Quantitative Analysis of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity of Tylcv-Infected Tomato Plants." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 232 (2025): 110109.

- Xue, Yingbin, Shengnan Zhu, Rainer Schultze-Kraft, Guodao Liu, and Zhijian Chen. "Dissection of Crop Metabolome Responses to Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium, and Other Nutrient Deficiencies." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 16 (2022): 9079.

- Li, Daoliang, Zhaoyang Song, Chaoqun Quan, Xianbao Xu, and Chang Liu. "Recent Advances in Image Fusion Technology in Agriculture." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 191 (2021): 106491.

- Takács, Péter, Adalbert Tibiássy, Balázs Bernáth, Viktor Gotthard, and Gábor Horváth. "Reflection–Polarization Characteristics of Greenhouses Studied by Drone-Polarimetry Focusing on Polarized Light Pollution of Glass Surfaces." Remote Sensing 16, no. 14 (2024): 2568.

- Wang, Xiaobin, Hongkai Zhao, and Yudi Zhou. "Polarization Ocean Lidar Detection of Characteristics of Yellow Sea Jellyfish." Infrared and Laser Engineering 50, no. 06 (2021): 122–28. [CrossRef]

- Hoshikawa, Keisuke, Takanori Nagano, Akihiko Kotera, Kazuo Watanabe, Yoichi Fujihara, and Osamu Kozan. "Classification of Crop Fields in Northeast Thailand Based on Hydrological Characteristics Detected by L-Band Sar Backscatter Data." Remote Sensing Letters 5, no. 4 (2014): 323–31.

- Liu, Shijing, Xueying Tu, Cheng Qian, Jie Zhou, and Jun Chen. "Feeding Behavior Classification of Grass Carp Based on Inter-Frame Optical Flow Features and an Improved Rnn." Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica 46, no. 06 (2022): 914–21. [CrossRef]

- Li, Siyuan, Jiannan Jiao, and Chi Wang. "Research on Polarized Multi-Spectral System and Fusion Algorithm for Remote Sensing of Vegetation Status at Night." Remote Sensing 13, no. 17 (2021): 3510. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xiang, Zenghui Liu, and Zhijian Chen. "Early Detection of Leaf Water Content Variation in Plants Using Polarization Imaging. ." Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 39, no. 11 (2023): 175–82. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Yang, Hou Kun, and Zhao Yunsheng. "Identification of Withered Plants and Bare Soil Using Polarization Spectra Based on Histogram of Oriented Gradients." Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves 38, no. 03 (2019): 365–70. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yufeng, Xianfeng Zhou, Yunrui Lin, Pengtao Shi, Daoyou Pan, and Jingcheng Zhang. "Evaluation of Tea Tree Leaf Chlorophyll Content Retrieval Using Multi-Angle Polarized Remote Sensing." Paper presented at the 2024 7th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence (PRAI) 2024.

- Huang, Shizhao, and Yanhui Tao. "Feature Extraction Method for Legumes Based on Polarization Information. ." Journal of Jiamusi University (Natural Science Edition) 38, no. 02 (2020): 130–32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Liyuan, Aichen Wang, Huiyue Zhang, Qingzhen Zhu, Huihui Zhang, Weihong Sun, and Yaxiao Niu. "Estimating Leaf Chlorophyll Content of Winter Wheat from Uav Multispectral Images Using Machine Learning Algorithms under Different Species, Growth Stages, and Nitrogen Stress Conditions." Agriculture 14, no. 7 (2024): 1064.

- Zhu, Jin, Xianhua Wang, Banglong Pan, and Hanhan Ye. "Polarized Spectral Characteristics of Chlorophyll in Water Bodies." Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 38, no. 05 (2013): 538–42. [CrossRef]

- Pang, HF, Lin Wang, LL Jiang, YL Chen, BQ Wang, and DQ Xiong. "Separation of Chlorophyll Fluorescence from Scattering Light of Algal Water Based on the Polarization Technique." Guang pu xue yu Guang pu fen xi= Guang pu 37, no. 2 (2017): 486–90.

- Yao, Ce, Shan Lu, and Zhongqiu Sun. "Estimation of Leaf Chlorophyll Content with Polarization Measurements: Degree of Linear Polarization." Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 242 (2020): 106787.

- Huang, Yufeng, Xianfeng Zhou, Yunrui Lin, Pengtao Shi, Daoyou Pan, and Jingcheng Zhang. "Evaluation of Tea Tree Leaf Chlorophyll Content Retrieval Using Multi-Angle Polarized Remote Sensing." Paper presented at the 2024 7th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence (PRAI) 2024.

- Xu, Jiayi, Huaping Luo, and Yuting Suo. "Application of Polarized Spectroscopy in Non-Destructive Detection of Jujube Leaves." Xinjiang Agricultural Mechanization, no. 01 (2021): 23–26. [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, Mohanned, Mutez Ali Ahmed, Gaochao Cai, Fabian Wankmüller, Nimrod Schwartz, Or Litig, Mathieu Javaux, and Andrea Carminati. "Stomatal Closure during Water Deficit Is Controlled by Below-Ground Hydraulics." Annals of Botany 129, no. 2 (2022): 161–70.

- Li, Xiaolu, Yunye Li, Xinzhao Xie, and Lijun Xu. "Research on a Laser Polarization Imaging Model Based on Leaf Water Content." Infrared and Laser Engineering 46, no. 11 (2017): 121–26. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Xinhao, Lijun Xu, and Xiaolu Li. "Leaf Moisture Content Measurement Using Polarized Active Imaging Lidar." Paper presented at the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST) 2017.

- Xu, Xiang, J. I. Yeqin, Zhijian Chen, Zenghui Liu, Bo Sun, and Dengxin Hua. "Rapid Nondestructive Detection of the Moisture Content of Holly Leaves Using Focal Plane Polarization Imaging." Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 40, no. 3 (2024): 219–26. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Siyuan, Bin Yang, Zihan Zhang, Yun Xiang, Taixia Wu, Yunsheng Zhao, and Feizhou Zhang. "Influence of Polarized Reflection on Airborne Remote Sensing of Canopy Foliar Nitrogen Content." International Journal of Remote Sensing 41, no. 13 (2020): 4879–900.

- Liu, Ming, Zhongqiu Sun, Shan Lu, and Kenji Omasa. "Combining Multiangular, Polarimetric, and Hyperspectral Measurements to Estimate Leaf Nitrogen Concentration from Different Plant Species." IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 60 (2021): 1–15.

- Zi-han, Zhang, Yan Lei, Liu Si-yuan, Fu Yui, Jiang Kai-wen, Yang Bin, Liu Sui-hua, and Zhang Fei-zhou. "Leaf Nitrogen Concentration Retrieval Based on Polarization Reflectance Model and Random Forest Regression." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 41, no. 9 (2021): 2911–17.

- Xu, Tongyu, Jiaxin Yang, and Jucheng Bai. "Inversion Model of Rice Canopy Nitrogen Content Based on Uav Polarimetric Remote Sensing." Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 54, no. 10 (2023): 171–78. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Wen-Jing, Han-Ping Mao, Hong-Yu Liu, Xiao-Dong Zhang, and Ji-Heng Ni. "Study on the Polarized Reflectance Characteristics of Single Greenhouse Tomato Nutrient Deficiency Leaves." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 34, no. 1 (2014): 145–50.

- Hanping, Mao, Zhu Wenjing, and Liu Hongyu. "Determination of Nitrogen and Potassium Content in Greenhouse Tomato Leaves Using a New Spectro-Goniophotometer." Crop and Pasture Science 65, no. 9 (2014): 888–98.

- Mahmood ur Rehman, Muhammad, Jizhan Liu, Aneela Nijabat, Muhammad Faheem, Wenyuan Wang, and Shengyi Zhao. "Leveraging Convolutional Neural Networks for Disease Detection in Vegetables: A Comprehensive Review." Agronomy 14, no. 10 (2024): 2231.

- Pourreza, Alireza, Won Suk Lee, Ed Etxeberria, and Yao Zhang. "Identification of Citrus Huanglongbing Disease at the Pre-Symptomatic Stage Using Polarized Imaging Technique." IFAC-PapersOnLine 49, no. 16 (2016): 110–15.

- Zhu, Shiming, Elin Malmqvist, Wansha Li, Samuel Jansson, Yiyun Li, Zheng Duan, Katarina Svanberg, Hongqiang Feng, Ziwei Song, and Guangyu Zhao. "Insect Abundance over Chinese Rice Fields in Relation to Environmental Parameters, Studied with a Polarization-Sensitive Cw near-Ir Lidar System." Applied Physics B 123, no. 7 (2017): 211.

- Xu, Qian, Jian-Rong Cai, Wen Zhang, Jun-Wen Bai, Zi-Qi Li, Bin Tan, and Li Sun. "Detection of Citrus Huanglongbing (Hlb) Based on the Hlb-Induced Leaf Starch Accumulation Using a Home-Made Computer Vision System." Biosystems Engineering 218 (2022): 163–74.

- Tan, Zuojun, Fei Cheng, Pengfei Wu, and Fang Wang. "Detection of Egg Freshness Throughpolarization Imaging." Applied Engineering in Agriculture 30, no. 2 (2014): 317–23.

- Fenfang, Lin, Zhang Dongyan, Wang Xiu, Wu Taixia, and Chen Xinfu. "Identification of Corn and Weeds on the Leaf Scale Using Polarization Spectroscopy." Infrared and laser Engineering 45, no. 12 (2016): 1223001–01 (10).

- Di, Yabei, Jinlong Yu, Huaping Luo, Huaiyu Liu, Lei Kang, and Yuesen Tong. "Study on Outdoor Spectral Inversion of Winter Jujube Based on Bpdf Models." Agriculture 15, no. 13 (2025): 1334.

- Geng, Dechun, Bin Chen, and Mingjie Chen. "Polarization Perturbation 2d Correlation Fluorescence Spectroscopy of Edible Oils: A Pilot Study." Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 13, no. 2 (2019): 1566–73.

- Xing, Muye, Yuan Long, Qingyan Wang, Xi Tian, Shuxiang Fan, Chi Zhang, and Wenqian Huang. "Physiological Alterations and Nondestructive Test Methods of Crop Seed Vigor: A Comprehensive Review." Agriculture 13, no. 3 (2023): 527.

- Rahman, Anisur, and Byoung-Kwan Cho. "Assessment of Seed Quality Using Non-Destructive Measurement Techniques: A Review." Seed Science Research 26, no. 4 (2016): 285–305.

- Xinyu, Wang, Guo Yangming, and Lu Wei. "Portable Rapid Detection Device for Rice Seed Germination Rate Based on Polarized Spectroscopy." Measurement and Control Technology 38, no. 01 (2019): 89–92. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Qingying, Wei Lu, Yuxin Guo, Wei He, Hui Luo, and Yiming Deng. "Vigor Detection for Naturally Aged Soybean Seeds Based on Polarized Hyperspectral Imaging Combined with Ensemble Learning Algorithm." Agriculture 13, no. 8 (2023): 1499.

- Rasheed, Muhammad Waseem, Jialiang Tang, Abid Sarwar, Suraj Shah, Naeem Saddique, Muhammad Usman Khan, Muhammad Imran Khan, Shah Nawaz, Redmond R Shamshiri, and Marjan Aziz. "Soil Moisture Measuring Techniques and Factors Affecting the Moisture Dynamics: A Comprehensive Review." Sustainability 14, no. 18 (2022): 11538.

- Cheng, Guangliang, Yunmeng Huang, Xiangtai Li, Shuchang Lyu, Zhaoyang Xu, Hongbo Zhao, Qi Zhao, and Shiming Xiang. "Change Detection Methods for Remote Sensing in the Last Decade: A Comprehensive Review." Remote Sensing 16, no. 13 (2024): 2355.

- Luo, Dayou, Xingping Wen, and Junlong Xu. "All-Sky Soil Moisture Estimation over Agriculture Areas from the Full Polarimetric Sar Gf-3 Data." Sustainability 14, no. 17 (2022): 10866.

- Wang, Xinqiang, Xiaobing Sun, and Lijuan Zhang. "Experimental Study on Spectral Polarization Characteristics of Soil Moisture in the Visible/near-Infrared Region." Infrared and Laser Engineering 44, no. 11 (2015): 3288–92. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Song, Dongfeng Deng, and Xiaobing Sun. "Experimental Study on a Remote Sensing Method for Soil Moisture Using Polarized Spectroscopy." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 36, no. 05 (2016): 1434–39. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ying, Yanqiang Yu, and Huijie Zhao. "Soil Moisture Retrieval Method Based on Polarization Information." Infrared and Laser Engineering 47, no. 01 (2018): 206–11. [CrossRef]

- Wenlong, Qiu, Ting Tang, Song He, Zheng Zeyong, Lv Jinhong, Guo Jiacheng, Zeng Yunfang, Lao Yifeng, and Weibin Wu. "Inversion Studies on the Heavy Metal Content of Farmland Soils Based on Spectroscopic Techniques: A Review." Agronomy 15, no. 7 (2025): 1678.

- Yang, Yu, Zhao Nanjing, and Meng Deshuo. "Research on Soil Heavy Metal Detection Based on Polarization-Resolved Libs Technology " Chinese Laser 45, no. 08 (2018): 267–72. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, DeWei. Soil Heavy Metal Detection Based on Polarization-Resolved Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. 硕士, Wuhan University of Technology, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Qianyi, Yang Han, Yaping Xu, Haiyan Yao, Haofang Niu, and Fang Huang. "Laboratory Research on Polarized Optical Properties of Saline-Alkaline Soil Based on Semi-Empirical Models and Machine Learning Methods." Remote Sensing 14, no. 1 (2022): 226.

- Manikandan, TT, Rajeev Sukumaran, M Radhakrishnan, MR Christhuraj, and M Saravanan. "Network Layer Communication Protocol Design for Underwater Agriculture Farming." International journal of communication systems 35, no. 6 (2022): e5088.

- Yue, Wei, Li Jiang, Xiubin Yang, Suining Gao, Yunqiang Xie, and Tingting Xu. "Optical Design of a Common-Aperture Camera for Infrared Guided Polarization Imaging." Remote Sensing 14, no. 7 (2022): 1620.

- Shen, Linghao, Mohamed Reda, Xun Zhang, Yongqiang Zhao, and Seong G Kong. "Polarization-Driven Solution for Mitigating Scattering and Uneven Illumination in Underwater Imagery." IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 62 (2024): 1–15.

- Guan, Jin Ge, Jing Ping Zhu, Heng Tian, and Xun Hou. "Real-Time Polarization Difference Underwater Imaging Based on Stokes Vector." Acta Physica Sinica -Chinese Edition- 64, no. 22 (2015).

- Qian, Jiamin, Jianxin Li, Yubo Wang, Jie Liu, Jiaxin Wang, and Donghui Zheng. "Underwater Image Recovery Method Based on Hyperspectral Polarization Imaging." Optics Communications 484 (2021): 126691.

- Pan, Tianfeng, Xianqiang He, Xuan Zhang, Jia Liu, Yan Bai, Fang Gong, and Teng Li. "Experimental Study on Bottom-up Detection of Underwater Targets Based on Polarization Imaging." Sensors 22, no. 8 (2022): 2827.

- Gui, Xinyuan, Ran Zhang, Haoyuan Cheng, Lianbiao Tian, and Jinkui Chu. "Multi-Turbidity Underwater Image Restoration Based on Neural Network and Polarization Imaging." Laser Optoelectron. Prog 59 (2022): 0410001.

- Song, Qiang, Xiaobing Sun, and Xiao Liu. "Investigation on the Influence of Bubble Groups in Underwater Environment on Target Imaging Based on Polarization Information " Acta Physica Sinica 70, no. 14 (2021): 210–25. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Axin, Tingfa Xu, Jianan Li, Geer Teng, Xi Wang, Yuhan Zhang, and Chang Xu. "Compressive Full-Stokes Polarization and Flexible Hyperspectral Imaging with Efficient Reconstruction." Optics and Lasers in Engineering 160 (2023): 107256.

- Tan, Jian, Junping Zhang, and Ye Zhang. "Target Detection for Polarized Hyperspectral Images Based on Tensor Decomposition." IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 14, no. 5 (2017): 674–78.

- Xie, Jun, Jiaolei Di, and Yuwen Qin. "Application of Deep Learning in Underwater Imaging Technology (Special Invited) " Journal of Photonics 51, no. 11 (2022): 9–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Wen Jing, Han Ping Mao, Qing Lin Li, Hong Yu Liu, Jun Sun, Zhi Yu Zuo, and Yong Chen. "Study on the Polarized Reflectance-Hyperspectral Information Fusion Technology of Tomato Leaves Nutrient Diagnoses." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 34, no. 9 (2014): 2500–05.

- Pan, Qian, Yang Han, and Lingzhi Wang. "Polarized Hyperspectral Reflectance Characteristics and Fertility Analysis of Soils in Northeast China's Farmland Area." Infrared 37, no. 08 (2016): 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lingzhi, Yang Han, and Qian. Pan. "A Study on a Multi-Angle Polarization Hyperspectral Model for Soil Fertility in Farmland." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 38, no. 01 (2018): 240–45. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Wei, Kun Hou, and Yunsheng Zhao. "A Study on the Identification of Withered Plants and Bare Soil Using Gradient Direction Histograms." Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves 38, no. 03 (2019): 365–70. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Wenjing, Jinyang Li, Lin Li, Aichen Wang, Xinhua Wei, and Hanping Mao. "Nondestructive Diagnostics of Soluble Sugar, Total Nitrogen and Their Ratio of Tomato Leaves in Greenhouse by Polarized Spectra-Hyperspectral Data Fusion." International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, no. 2 (2020).

- Hao, Tianyi, Yang Han, and Zeping Liu. " Spatial Variation Distribution and Model Establishment of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Based on Multi-Angle Spectral and Polarization Spectroscopy." Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 40, no. 12 (2020): 3692–98. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Huaping, Luying Yi, Ling Guo, and Wei Li. "Based on Hyperspectral Polarization to Build the Quantitative Remote Sensing Model of Jujube in Southern Xinjiang." Paper presented at the Sixth Symposium on Novel Optoelectronic Detection Technology and Applications 2020.

- Faqeerzada, Mohammad Akbar, Anisur Rahman, Geonwoo Kim, Eunsoo Park, Rahul Joshi, Santosh Lohumi, and Byoung-Kwan Cho. "Prediction of Moisture Contents in Green Peppers Using Hyperspectral Imaging Based on a Polarized Lighting System." Korean Journal of Agricultural Science 47, no. 4 (2020): 995–1010.

- Hao, Jinglei, Yongqiang Zhao, Haimeng Zhao, and Peter BREZANY. "3d Reconstruction of High-Reflective and Textureless Targets Based on Multispectral Polarization and Machine Vision." Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 47, no. 06 (2018): 816–24. [CrossRef]

- Li, Siyuan, Jiannan Jiao, Jinbo Chen, and Chi Wang. "A New Polarization-Based Vegetation Index to Improve the Accuracy of Vegetation Health Detection by Eliminating Specular Reflection of Vegetation." IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 60 (2022): 1–18.

- Mukhametova, Liliya I, Marya K Kolokolova, Ivan A Shevchenko, Boris S Tupertsev, Anatoly V Zherdev, Chuanlai Xu, and Sergei A Eremin. "Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay for Rapid, Sensitive Detection of the Herbicide 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid in Juice and Water Samples." Biosensors 15, no. 1 (2025): 32.

- Zhou, Liangliang, Jiachuan Yang, Zhexuan Tao, Sergei A Eremin, Xiude Hua, and Minghua Wang. "Development of Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay for Imidacloprid in Environmental and Agricultural Samples." Frontiers in Chemistry 8 (2020): 615594.

- Lippolis, Vincenzo, Michelangelo Pascale, Stefania Valenzano, Anna Chiara Raffaella Porricelli, Michele Suman, and Angelo Visconti. "Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay for Rapid, Accurate and Sensitive Determination of Ochratoxin a in Wheat." Food Analytical Methods 7, no. 2 (2014): 298–307.

- Zhang, Xiya, Qianqian Tang, Tiejun Mi, Sijun Zhao, Kai Wen, Liuchuan Guo, Jiafei Mi, Suxia Zhang, Weimin Shi, and Jianzhong Shen. "Dual-Wavelength Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay to Increase Information Content Per Screen: Applications for Simultaneous Detection of Total Aflatoxins and Family Zearalenones in Maize." Food Control 87 (2018): 100–08.

- Yao, Li, Jianguo Xu, Wei Qu, Dongqing Qiao, Sergei A Eremin, Jianfeng Lu, Wei Chen, and Panzhu Qin. "Performance Improved Fluorescence Polarization for Easy and Accurate Authentication of Chicken Adulteration." Food Control 133 (2022): 108604.

- Sindhu, Sindhu, and Annamalai Manickavasagan. "Nondestructive Testing Methods for Pesticide Residue in Food Commodities: A Review." Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 22, no. 2 (2023): 1226–56.

- Guo, Zhiming, Xinchen Wu, Heera Jayan, Limei Yin, Shanshan Xue, Hesham R El-Seedi, and Xiaobo Zou. "Recent Developments and Applications of Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering Spectroscopy in Safety Detection of Fruits and Vegetables." Food Chemistry 434 (2024): 137469.

- Xu, Lingyuan, AM Abd El-Aty, Jong-Bang Eun, Jae-Han Shim, Jing Zhao, Xingmei Lei, Song Gao, Yongxin She, Fen Jin, and Jing Wang. "Recent Advances in Rapid Detection Techniques for Pesticide Residue: A Review." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 70, no. 41 (2022): 13093–117.

- Xin, Zhou, Sun Jun, Lu Bing, Wu Xiaohong, Dai Chunxia, and Yang Ning. "Study on Pesticide Residues Classification of Lettuce Leaves Based on Polarization Spectroscopy." Journal of Food Process Engineering 41, no. 8 (2018): e12903.

- Wang, Yulong, Zhenfeng Li, Bogdan Barnych, Jingqian Huo, Debin Wan, Natalia Vasylieva, Junli Xu, Pan Li, Beibei Liu, and Cunzheng Zhang. "Investigation of the Small Size of Nanobodies for a Sensitive Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay for Small Molecules: 3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid, an Exposure Biomarker of Pyrethroid Insecticides as a Model." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 67, no. 41 (2019): 11536–41.

- Hernández, Mercedes, Andrés A Borges, and Desiderio Francisco-Bethencourt. "Mapping Stressed Wheat Plants by Soil Aluminum Effect Using C-Band Sar Images: Implications for Plant Growth and Grain Quality." Precision agriculture 23, no. 3 (2022): 1072–92.

- Hasituya, Zhongxin Chen, Fei Li, and Hongmei. "Mapping Plastic-Mulched Farmland with C-Band Full Polarization Sar Remote Sensing Data." Remote Sensing 9, no. 12 (2017): 1264.

- Sid’ko, AF, I Yu Botvich, TI Pisman, and AP Shevyrnogov. "Analysis of the Polarization Characteristics of Wheat and Maize Crops Using Land-Based Remote-Sensing Measurements." Biophysics 60, no. 4 (2015): 668–71. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yuanzhi, Hongsheng Zhang, and Hui Lin. "Improving the Impervious Surface Estimation with Combined Use of Optical and Sar Remote Sensing Images." Remote Sensing of Environment 141 (2014): 155–67.

- Kuester, Theres, and Daniel Spengler. "Structural and Spectral Analysis of Cereal Canopy Reflectance and Reflectance Anisotropy." Remote Sensing 10, no. 11 (2018): 1767.

- Heine, Iris, Thomas Jagdhuber, and Sibylle Itzerott. "Classification and Monitoring of Reed Belts Using Dual-Polarimetric Terrasar-X Time Series." Remote Sensing 8, no. 7 (2016): 552.

- Sun, Zhongqiu, Yunsheng Zhao, and Shan Lu. "The Role of Polarized Reflectance Information in the Study of Bidirectional Reflection in Vegetation Remote Sensing." Remote Sensing Journal 22, no. 06 (2018): 947–56. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Limin, Jia Liu, Lingbo Yang, Zhongxin Chen, Xiaolong Wang, and Bin Ouyang. "Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images on Agricultural Remote Sensing Monitoring." Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 29, no. 18 (2013): 136–45.

- Zhang, Zhengxin, and Lixue Zhu. "A Review on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing: Platforms, Sensors, Data Processing Methods, and Applications." drones 7, no. 6 (2023): 398.

- Larsen, Joshua, Jeffrey Dunne, Robert Austin, Cassondra Newman, and Michael Kudenov. "Drone-Based Polarization Imaging System for Leaf Spot Severity Determination in Peanut Plants." The Plant Phenome Journal 8, no. 1 (2025): e270018.

- Száz, Dénes, Péter Takács, Balázs Bernáth, György Kriska, András Barta, István Pomozi, and Gábor Horváth. "Drone-Based Imaging Polarimetry of Dark Lake Patches from the Viewpoint of Flying Polarotactic Insects with Ecological Implication." Remote Sensing 15, no. 11 (2023): 2797.

- Larsen, Joshua C, Robert Austin, Jeffrey Dunne, and Michael W Kudenov. "Drone-Based Polarization Imaging for Phenotyping Peanut in Response to Leaf Spot Disease." Paper presented at the Polarization: Measurement, Analysis, and Remote Sensing XV 2022.

- Liu, Fei, SJ Sun, PL Han, K Yang, and X Shao. "Development of Underwater Polarization Imaging Technology." Laser & Optoelectronics Progress 58, no. 6 (2021): 0600001.

- Ren, Qiming, Yanfa Xiang, Guochen Wang, Jie Gao, Yan Wu, and Rui-Pin Chen. "The Underwater Polarization Dehazing Imaging with a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network." Optik 251 (2022): 168381.

- Sun, Chunsheng, Zhichao Ding, and Liheng Ma. "Optimized Method for Polarization-Based Image Dehazing." Heliyon 9, no. 5 (2023).

- Liu, Shuai, Hang Li, Jinyu Zhao, Junchi Liu, Youqiang Zhu, and Zhenduo Zhang. "Atmospheric Light Estimation Using Polarization Degree Gradient for Image Dehazing." Sensors 24, no. 10 (2024): 3137.

- Zhang, Xin, Xia Wang, Changda Yan, Gangcheng Jiao, and Huiyang He. "Polarization-Based Two-Stage Image Dehazing in a Low-Light Environment." Electronics 13, no. 12 (2024): 2269.

- Liang, Jian, Liyong Ren, Haijuan Ju, Wenfei Zhang, and Enshi Qu. "Polarimetric Dehazing Method for Dense Haze Removal Based on Distribution Analysis of Angle of Polarization." Optics Express 23, no. 20 (2015): 26146–57.

- Schlund, Michael, and Stefan Erasmi. "Sentinel-1 Time Series Data for Monitoring the Phenology of Winter Wheat." Remote Sensing of Environment 246 (2020): 111814.

- Zapotoczny, Piotr, Jacek Reiner, M Mrzygłód, and Piotr Lampa. "The Use of Polarized Light and Image Analysis in Evaluations of the Severity of Fungal Infection in Barley Grain." Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 169 (2020): 105154.

- Nguyen-Do-Trong, Nghia, Jean Claude Dusabumuremyi, and Wouter Saeys. "Cross-Polarized Vnir Hyperspectral Reflectance Imaging for Non-Destructive Quality Evaluation of Dried Banana Slices, Drying Process Monitoring and Control." Journal of Food Engineering 238 (2018): 85–94.

- Jin, DUAN, ZHANG Hao, SONG Jingyuan, and LIU Ju. "Review of Polarization Image Fusion Based on Deep Learning." Infrared Technology 46, no. 2 (2024): 119–28.

- Pierangeli, Davide, Giovanni Volpe, and Claudio Conti. "Deep Learning Enabled Transmission of Full-Stokes Polarization Images through Complex Media." Laser & Photonics Reviews 18, no. 11 (2024): 2400626.

- Zhang, Xiaodong, Yafei Wang, Zhankun Zhou, Yixue Zhang, and Xinzhong Wang. "Detection Method for Tomato Leaf Mildew Based on Hyperspectral Fusion Terahertz Technology." Foods 12, no. 3 (2023): 535.

| Sample | Direction of application | Core method | Best performance | Reference | |

| The laboratory prepared water and Chaohu lake water | Remote sensing inversion of chlorophyll concentration in water | Polarization and reflectivity spectrum comparison modeling | The correlation between blue and green polarization models is high (R²=0.948) | [89] | |

| Tea tree leaves | Remote sensing estimation of chlorophyll content | Multi-angle polarized remote sensing, Maignan model, specular separation | NDVI model R² improved from 0.22 to 0.53, RMSE reduced from 16.11 to 12.67 μg/cm² (≈25% improvement) | NDVI model R² improved from 0.22 to 0.53, RMSE reduced from 16.11 to 12.67 μg/cm² (≈25% improvement) | [92] |

| NDVI model R² improved from 0.22 to 0.53, RMSE reduced from 16.11 to 12.67 μg/cm² (≈25% improvement) | |||||

| Green leaves, ginkgo and apple leaves | Remote sensing inversion of vegetation canopy structure | Stokes vector and PROSPECT model analysis | The polarization degree of red light band is stable, the near infrared band is sensitive to the Angle, and water has no significant effect | [54] |

| Sample | Technical method | Model method | Main conclusion | Reference |

| Rice seeds after aging treatment | Continuous polarization spectrum(different polarization angles and wavelengths) | PLSR、BPNN、RBFNN | RBFNN has the highest accuracy (r = 0.976) | [56] |

| Foreign fibers in cotton | Line laser polarization imaging | Improved YOLOv5 (with Shufflenetv2, PANet optimization, and CA attention) | YOLOv5-CFD achieved 96.9% accuracy, 385 FPS, and 0.75 MB model size | [37] |

| Rice seeds in soaking solution | STM32 control system and polarization spectroscopy device | Modeling based on changes in polarization intensity | A portable detector was constructed to adapt to a variety of rice varieties, and the prediction accuracy reached more than 90% | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).