Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

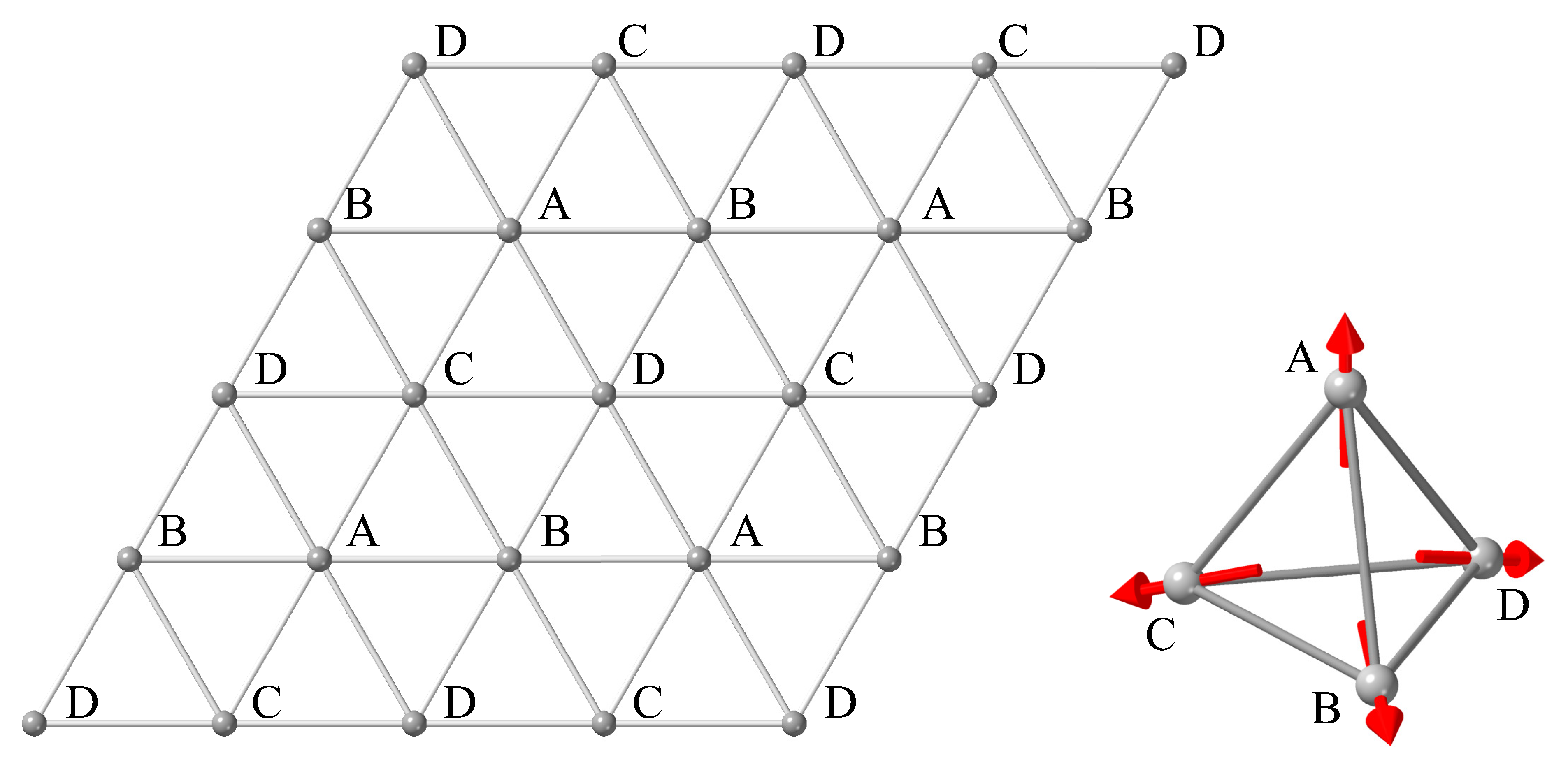

2. Setup

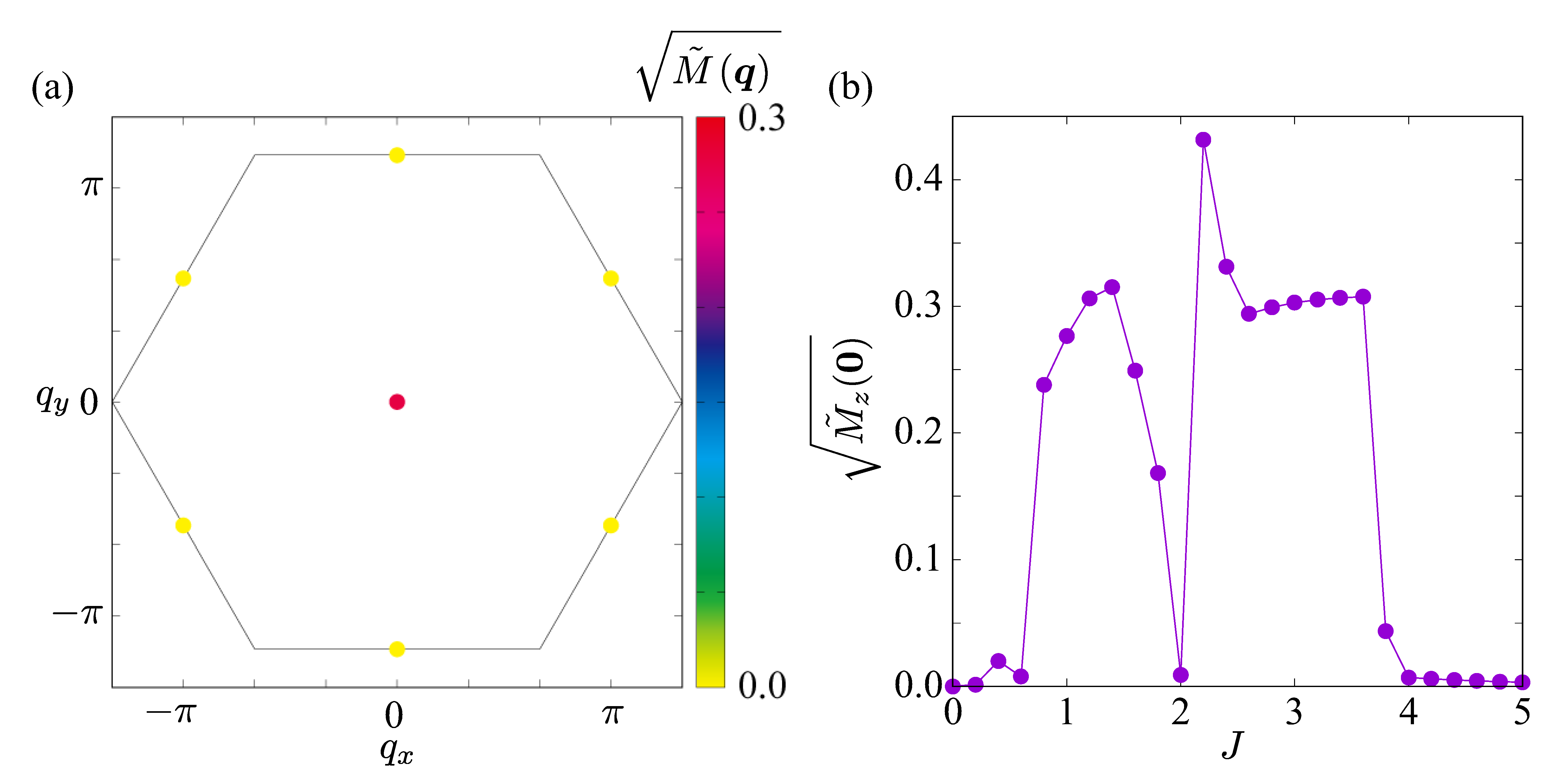

3. Results Without the Spin–Orbit Coupling

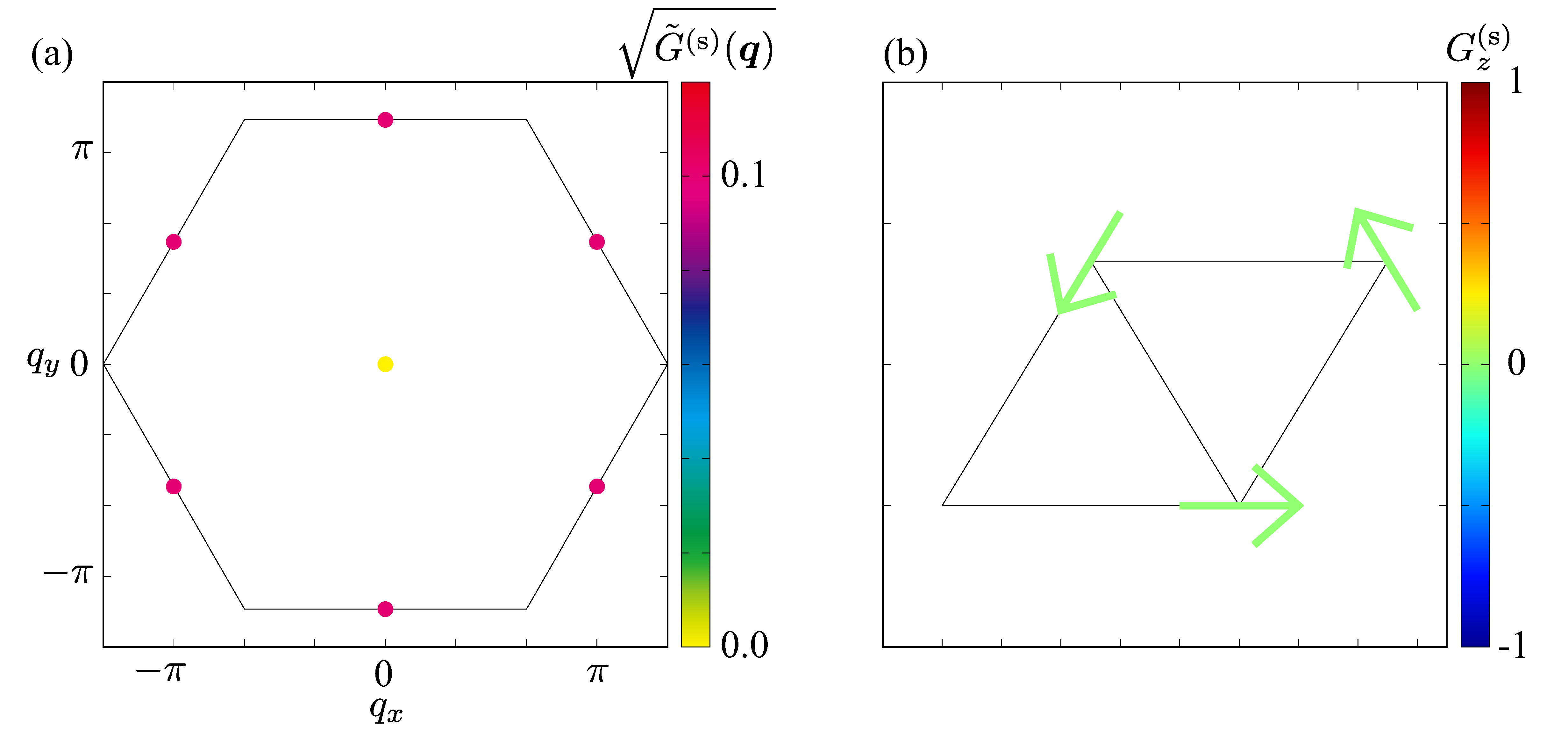

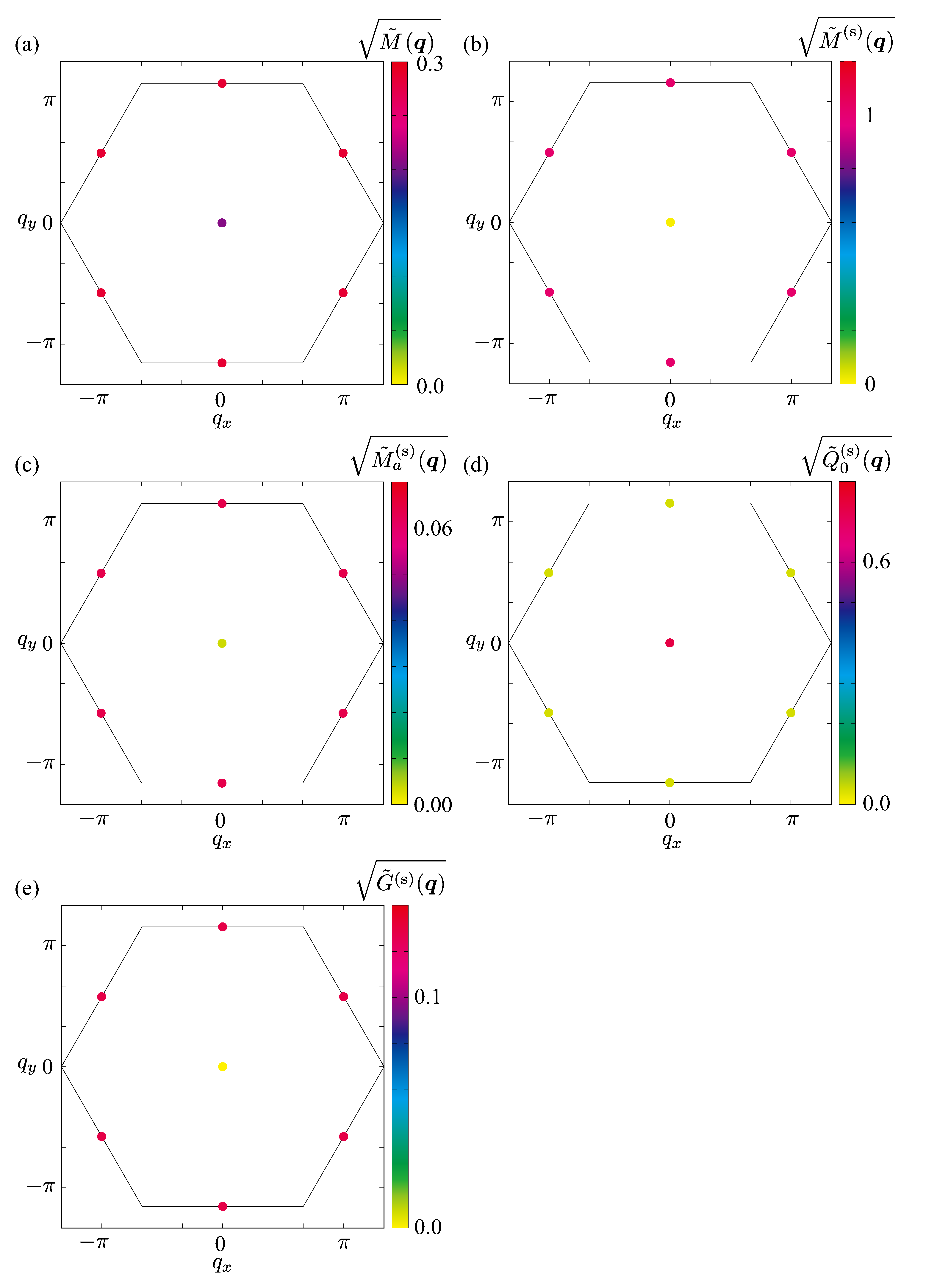

3.1. Orbital Magnetic Dipole

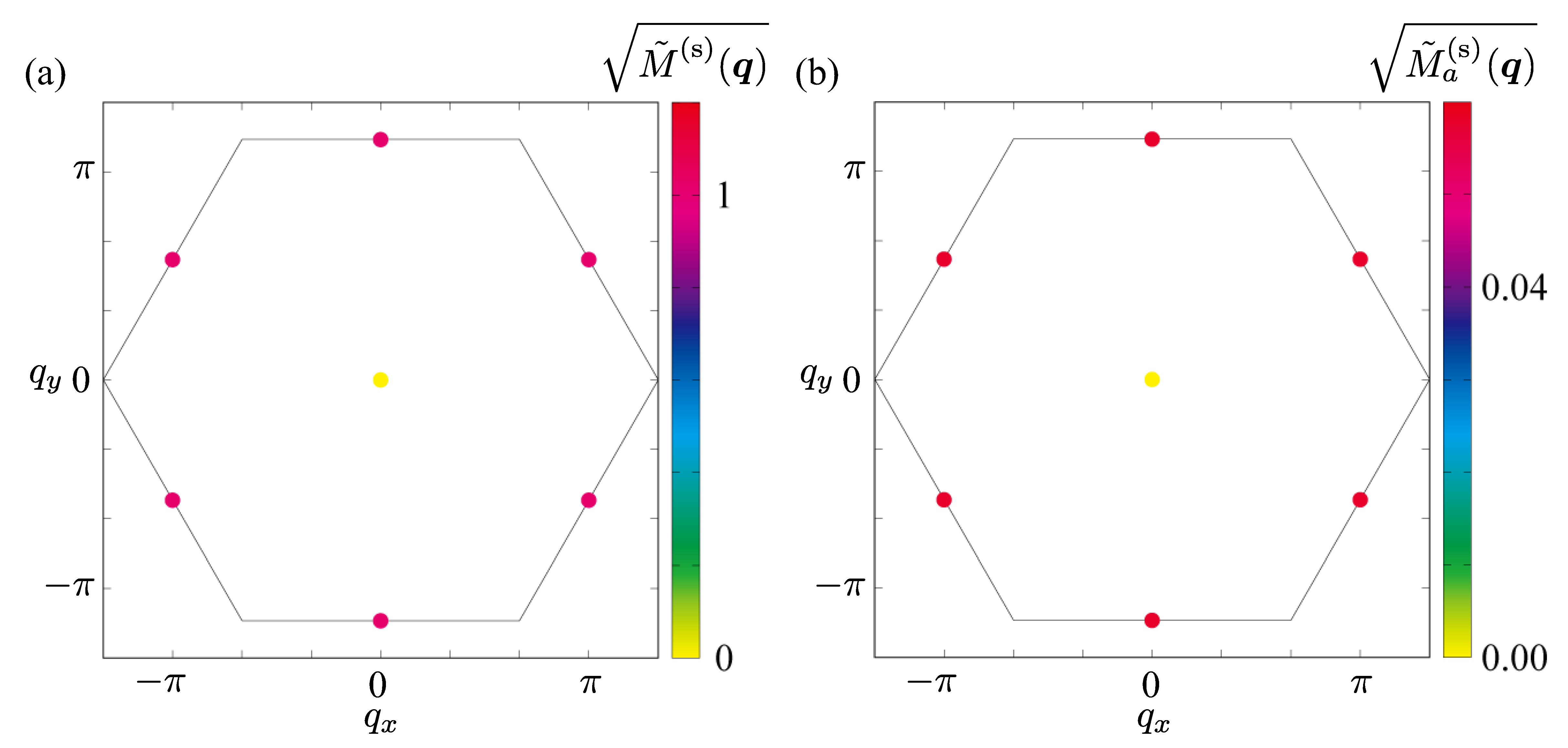

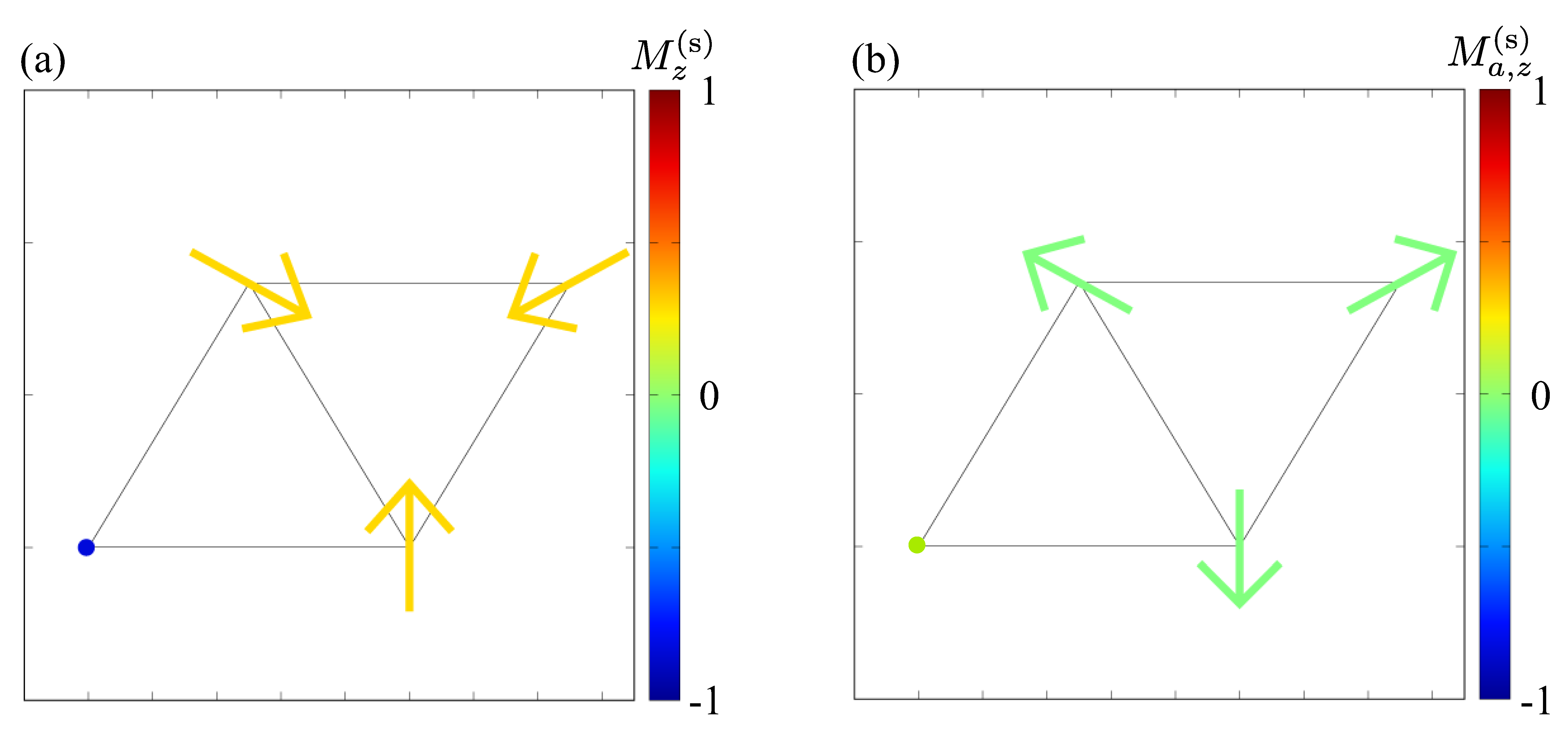

3.2. Spin and anisotropic magnetic dipoles

3.3. Effective Spin–Orbit Coupling

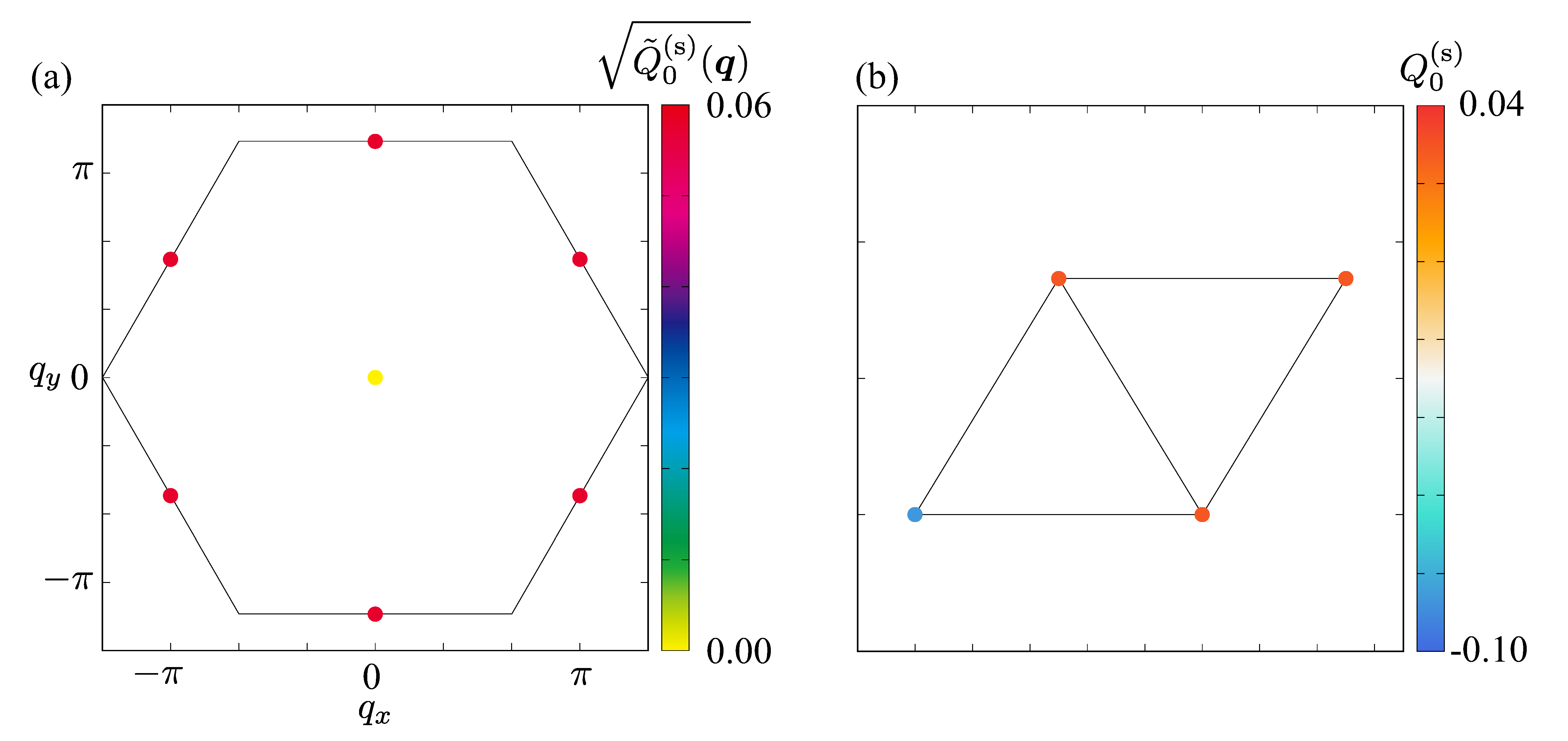

3.4. Axial Density Waves

4. Results with the Spin–Orbit Coupling

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Ohgushi, K.; Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N. Spin anisotropy and quantum Hall effect in the kagomé lattice: Chiral spin state based on a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, R6065–R6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.; Oohara, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Spin chirality, Berry phase, and anomalous Hall effect in a frustrated ferromagnet. Science 2001, 291, 2573–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatara, G.; Kawamura, H. Chirality-driven anomalous Hall effect in weak coupling regime. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 71, 2613–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A. Theory of helical spin crystals: Phases, textures, and properties. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 214408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, Y.; Nakatsuji, S.; Maeno, Y.; Tayama, T.; Sakakibara, T.; Onoda, S. Unconventional anomalous Hall effect enhanced by a noncoplanar spin texture in the frustrated Kondo lattice Pr2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 057203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C.; Binz, B.; Rosch, A.; Ritz, R.; Niklowitz, P.G.; Böni, P. Topological Hall Effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 186602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Okubo, T.; Motome, Y. Phase shift in skyrmion crystals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yatsushiro, M. Nonlinear nonreciprocal transport in antiferromagnets free from spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 014420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yatsushiro, M. Nonreciprocal Transport in Noncoplanar Magnetic Systems without Spin–Orbit Coupling, Net Scalar Chirality, or Magnetization. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 094704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eto, R.; Pohle, R.; Mochizuki, M. Low-Energy Excitations of Skyrmion Crystals in a Centrosymmetric Kondo-Lattice Magnet: Decoupled Spin-Charge Excitations and Nonreciprocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 017201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olive, J.A.; Young, A.P.; Sherrington, D. Computer simulation of the three-dimensional short-range Heisenberg spin glass. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 6341–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, H. Chiral ordering in Heisenberg spin glasses in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3785–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Stabilization mechanisms of magnetic skyrmion crystal and multiple-Q states based on momentum-resolved spin interactions. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Frustration-induced skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 183004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.; Batista, C.D. Itinerant Electron-Driven Chiral Magnetic Ordering and Spontaneous Quantum Hall Effect in Triangular Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 156402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, Y.; Motome, Y. Spin Chirality Ordering and Anomalous Hall Effect in the Ferromagnetic Kondo Lattice Model on a Triangular Lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 083711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; van den Brink, J. Frustration-Induced Insulating Chiral Spin State in Itinerant Triangular-Lattice Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 216405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Martin, I.; Batista, C.D. Stability of the Spontaneous Quantum Hall State in the Triangular Kondo-Lattice Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 266405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, P.; Lebech, B. "Triple-q→" Modulated Magnetic Structure and Critical Behavior of Neodymium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, K.A.; Walker, M.B. Free-energy analysis of the single-q and double-q magnetic structures of neodymium. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 1781–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zochowski, S.; McEwen, K. Thermal expansion study of the magnetic phase diagram of neodymium. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1986, 54, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgan, E.; Rainford, B.; Lee, S.; Abell, J.; Bi, Y. The magnetic structure of CeAl2 is a non-chiral spiral. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1990, 2, 10211. [Google Scholar]

- Korshunov, S.E. Chiral phase of the Heisenberg antiferromagnet with a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 6165–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messio, L.; Lhuillier, C.; Misguich, G. Lattice symmetries and regular magnetic orders in classical frustrated antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 184401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, P.; Bihlmayer, G.; Hirai, K.; Blügel, S. Three-Dimensional Spin Structure on a Two-Dimensional Lattice: Mn/Cu(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.S.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, J.X.; Sheng, D.N.; Yang, K. Global phase diagram and quantum spin liquids in a spin-12 triangular antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 075116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, K.; Venderbos, J.W.F.; Chern, G.W.; Batista, C.D. Exotic magnetic orderings in the kagome Kondo-lattice model. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 245119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; O’Brien, P.; Henley, C.L.; Lawler, M.J. Phase diagram of the Kondo lattice model on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 024401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindou, R.; Nagaosa, N. Orbital Ferromagnetism and Anomalous Hall Effect in Antiferromagnets on the Distorted fcc Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, P.; Iqbal, Y.; Penc, K. Degenerate manifolds, helimagnets, and multi-Q chiral phases in the classical Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the face-centered-cubic lattice. Phys. Rev. Research 2020, 2, 043278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, T.; Kubo, K.; Niki, K. Possible Chiral Phase Transition in Two-Dimensional Solid 3He. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 2081–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, Y.; Udagawa, M.; Motome, Y. Hidden Multiple-Spin Interactions as an Origin of Spin Scalar Chiral Order in Frustrated Kondo Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 096401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Ishizuka, H. Colossal Enhancement of Spin-Chirality-Related Hall Effect by Thermal Fluctuation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, D.; Goldbart, P.M. Persistent currents from Berry’s phase in mesoscopic systems. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13544–13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Millis, A.J.; Shraiman, B.I.; Majumdar, P.; Tešanović, Z. Berry Phase Theory of the Anomalous Hall Effect: Application to Colossal Magnetoresistance Manganites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 3737–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Sinova, J.; Onoda, S.; MacDonald, A.H.; Ong, N.P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1539–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Chang, M.C.; Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1959–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Yablonskii, D.A. Thermodynamically stable “vortices" in magnetically ordered crystals: The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 1989, 68, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, A.; Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1994, 138, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 2009, 323, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonietz, F.; Mu¨hlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Neubauer, A.; Mu¨nzer, W.; Bauer, A.; Adams, T.; Georgii, R.; Bo¨ni, P.; Duine, R.A.; et al. Spin Transfer Torques in MnSi at Ultralow Current Densities. Science 2010, 330, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Jonietz, F.; Bauer, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Keiderling, U.; Everschor, K.; et al. Long-Range Crystalline Nature of the Skyrmion Lattice in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 217206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Magnetic phase diagram of MnSi inferred from magnetization and ac susceptibility. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 214418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. Specific Heat of the Skyrmion Lattice Phase and Field-Induced Tricritical Point in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 177207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, A.; Bauer, A.; Adams, T.; Rucker, F.; Brandl, G.; Georgii, R.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. Uniaxial Pressure Dependence of Magnetic Order in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 267202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Kindervater, J.; Adams, T.; Bauer, A.; Keiderling, U.; Pfleiderer, C. Kinetic small angle neutron scattering of the skyrmion lattice in MnSi. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 075017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, M.; Bauer, A.; Leitner, M.; Gigl, T.; Anwand, W.; Butterling, M.; Wagner, A.; Kudejova, P.; Pfleiderer, C.; Hugenschmidt, C. Positron spectroscopy of point defects in the skyrmion-lattice compound MnSi. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.Z.; Onose, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Park, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Matsui, Y.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 2010, 465, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzer, W.; Neubauer, A.; Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Franz, C.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Pedersen, B.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Skyrmion lattice in the doped semiconductor Fe1-xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 041203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Neubauer, A.; Münzer, W.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Pedersen, B.; Böni, P.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Skyrmion lattice domains in Fe1-xCoxSi. In Proceedings of the J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. IOP Publishing, Vol. 200; 2010; p. 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Kanazawa, N.; Onose, Y.; Kimoto, K.; Zhang, W.; Ishiwata, S.; Matsui, Y.; Tokura, Y. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Meng, K.Y.; Brangham, J.T.; Wang, H.L.; Esser, B.D.; McComb, D.W.; Yang, F.Y. Robust Zero-Field Skyrmion Formation in FeGe Epitaxial Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 027201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, E.; Paik, H.; Nguyen, K.; Muller, D.A.; Schlom, D.G.; Fuchs, G.D. Engineering Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in B20 thin-film chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 074404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.S.; Gayles, J.; Porter, N.A.; Sugimoto, S.; Aslam, Z.; Kinane, C.J.; Charlton, T.R.; Freimuth, F.; Chadov, S.; Langridge, S.; et al. Helical magnetic structure and the anomalous and topological Hall effects in epitaxial B20 Fe1-yCoyGe films. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 214406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Sakakibara, T.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Giant Hall resistivity and magnetoresistance in cubic chiral antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 023701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Frontzek, M.D.; Matsuda, M.; Nakao, A.; Munakata, K.; Ohhara, T.; Kakihana, M.; Haga, Y.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Helical Magnetic Order and Field-Induced Phase in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 013702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, C.; Matsumura, T.; Nakao, H.; Michimura, S.; Kakihana, M.; Inami, T.; Kaneko, K.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Magnetic Field Induced Triple-q Magnetic Order in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi Studied by Resonant X-ray Scattering. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 093704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Harima, H.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Magnetic Phases in the Skyrmion Lattice and Fermi Surface Properties in Cubic Chiral Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 094705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Manchanda, P.; Pahari, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Valloppilly, S.R.; Li, X.; Sarella, A.; Yue, L.; Ullah, A.; et al. Chiral Magnetism and High-Temperature Skyrmions in B20-Ordered Co-Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 057201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Field-Direction Sensitive Skyrmion Crystals in Cubic Chiral Systems: Implication to 4f-Electron Compound EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 073705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, V.; Xu, Q.; Ntallis, N.; Clulow, R.; Shtender, V.; Cedervall, J.; Sahlberg, M.; Wikfeldt, K.T.; Thonig, D.; Pereiro, M.; et al. Tuning skyrmions in B20 compounds by 4d and 5d doping. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 084401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kézsmárki, I.; Bordács, S.; Milde, P.; Neuber, E.; Eng, L.M.; White, J.S.; Rønnow, H.M.; Dewhurst, C.D.; Mochizuki, M.; Yanai, K.; et al. Neel-type skyrmion lattice with confined orientation in the polar magnetic semiconductor GaV4S8. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordács, S.; Butykai, A.; Szigeti, B.G.; White, J.S.; Cubitt, R.; Leonov, A.O.; Widmann, S.; Ehlers, D.; von Nidda, H.A.K.; Tsurkan, V.; et al. Equilibrium skyrmion lattice ground state in a polar easy-plane magnet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujima, Y.; Abe, N.; Tokunaga, Y.; Arima, T. Thermodynamically stable skyrmion lattice at low temperatures in a bulk crystal of lacunar spinel GaV4Se8. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 180410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Ukleev, V.; Feoktystov, A.; Arima, T.h.; Kakurai, K.; Tokura, Y. Néel-Type Skyrmion Lattice in the Tetragonal Polar Magnet VOSe2O5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 237201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Fujishiro, Y.; Hayami, S.; Moody, S.H.; Nomoto, T.; Baral, P.R.; Ukleev, V.; Cubitt, R.; Steinke, N.J.; Gawryluk, D.J.; et al. Transition between distinct hybrid skyrmion textures through their hexagonal-to-square crystal transformation in a polar magnet. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.R.; Sugawara, H.; Matsuda, T.D.; Sato, H.; Mallik, R.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic anisotropy, first-order-like metamagnetic transitions, and large negative magnetoresistance in single-crystal Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 12162–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Hirschberger, M.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Taguchi, Y.; Arima, T.h.; Tokura, Y. Skyrmion lattice with a giant topological Hall effect in a frustrated triangular-lattice magnet. Science 2019, 365, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Spitz, L.; Nomoto, T.; Kurumaji, T.; Gao, S.; Masell, J.; Nakajima, T.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; et al. Topological Nernst Effect of the Two-Dimensional Skyrmion Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 076602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Iyer, K.K.; Paulose, P.L.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic and transport anomalies in R2RhSi34pt0ex(R=Gd, Tb, and Dy) resembling those of the exotic magnetic material Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 144440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spachmann, S.; Elghandour, A.; Frontzek, M.; Löser, W.; Klingeler, R. Magnetoelastic coupling and phases in the skyrmion lattice magnet Gd2PdSi3 discovered by high-resolution dilatometry. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 184424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomilšek, M.; Hicken, T.J.; Wilson, M.N.; Franke, K.J.A.; Huddart, B.M.; Štefančič, A.; Holt, S.J.R.; Balakrishnan, G.; Mayoh, D.A.; Birch, M.T.; et al. Anisotropic Skyrmion and Multi-q Spin Dynamics in Centrosymmetric Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 046702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kabeya, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Araki, K.; Katoh, K.; Ochiai, A. Spin trimer formation in the metallic compound Gd3Ru4Al12 with a distorted kagome lattice structure. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 054410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Nakajima, T.; Gao, S.; Peng, L.; Kikkawa, A.; Kurumaji, T.; Kriener, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; et al. Skyrmion phase and competing magnetic orders on a breathing kagome lattice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Hayami, S.; Tokura, Y. Nanometric skyrmion lattice from anisotropic exchange interactions in a centrosymmetric host. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 023039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Magnetic anisotropies and skyrmion lattice related to magnetic quadrupole interactions of the RKKY mechanism in the frustrated spin-trimer system Gd3Ru4Al12 with a breathing kagome structure. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 184433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, P.; Carretta, S.; Amoretti, G.; Caciuffo, R.; Magnani, N.; Lander, G.H. Multipolar interactions in f-electron systems: The paradigm of actinide dioxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 807–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, Y.; Kusunose, H.; Kiss, A. Multipole orders and fluctuations in strongly correlated electron systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.T.; Ikeda, H.; Oppeneer, P.M. First-principles theory of magnetic multipoles in condensed matter systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 041008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunose, H.; Hayami, S. Generalization of microscopic multipoles and cross-correlated phenomena by their orderings. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 464002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayami, S.; Kusunose, H. Unified description of electronic orderings and cross correlations by complete multipole representation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 93, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.T.; Koretsune, T.; Ochi, M.; Arita, R. Cluster multipole theory for anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 094406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Oiwa, R.; Kusunose, H. Electric Ferro-Axial Moment as Nanometric Rotator and Source of Longitudinal Spin Current. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 113702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Mechanism of antisymmetric spin polarization in centrosymmetric multiple-Q magnets based on effective chiral bilinear and biquadratic spin cross products. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 024413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhachov, P.; Linder, J. Impurity-induced Friedel oscillations in altermagnets and p-wave magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 205114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, B.; Sukhachov, P.; Giil, H.G.; Brataas, A.; Linder, J. Minimal Models and Transport Properties of Unconventional p-Wave Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 236703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, H.; Nagaosa, N.; Balatsky, A.V. Spin Current and Magnetoelectric Effect in Noncollinear Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 057205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostovoy, M. Ferroelectricity in Spiral Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 067601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergienko, I.A.; Dagotto, E. Role of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in multiferroic perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 094434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.B.; Yildirim, T.; Aharony, A.; Entin-Wohlman, O. Towards a microscopic model of magnetoelectric interactions in Ni3V2O8. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 184433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Seki, S.; Nagaosa, N. Multiferroics of spin origin. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2014, 77, 076501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 1834–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Spin Hall Effect in the Presence of Spin Diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Zhang, S.C. Dissipationless quantum spin current at room temperature. Science 2003, 301, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Zhang, S.C. Spin-Hall Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 156804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinova, J.; Culcer, D.; Niu, Q.; Sinitsyn, N.A.; Jungwirth, T.; MacDonald, A.H. Universal Intrinsic Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 126603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunose, H.; Oiwa, R.; Hayami, S. Complete Multipole Basis Set for Single-Centered Electron Systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, R.; White, J.; Hayami, S.; Arita, R.; Honecker, D.; Rønnow, H.; Tokura, Y.; Seki, S. Multiple-q noncollinear magnetism in an itinerant hexagonal magnet. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Zhang, K.X.; Park, P.; Cho, W.; Kim, H.; Noh, H.J.; Park, J.G. Electrical control of topological 3Q state in intercalated van der Waals antiferromagnet Cox-TaS2. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Lin, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, B.; Lv, Y.; Han, G.; Li, S.; Cai, Y.; Jin, F.; et al. Spontaneous Topological Hall Effect in Intercalated Co1/3TaS2 Nanoflakes with Non-Coplanar Antiferromagnetic Order. Adv. Func. Mater. 2025; 2502016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, P.; Cho, W.; Kim, C.; An, Y.; Iida, K.; Kajimoto, R.; Matin, S.; Zhang, S.S.; Batista, C.D.; Park, J.G. Spin Dynamics of Triple-Q Magnetic Orderings in a Triangular Lattice: Implications for Multi-Q Orderings in General Two-Dimensional Lattices. Phys. Rev. X 2025, 15, 031032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulaevskii, L.N.; Batista, C.D.; Mostovoy, M.V.; Khomskii, D.I. Electronic orbital currents and polarization in Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 024402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt, D. Berry phases in electronic structure theory: electric polarization, orbital magnetization and topological insulators; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018.

- Resta, R.; Ceresoli, D.; Thonhauser, T.; Vanderbilt, D. Orbital magnetization in extended systems. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2005, 6, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Shi, J.; Niu, Q. Berry Phase Correction to Electron Density of States in Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 137204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thonhauser, T.; Ceresoli, D.; Vanderbilt, D.; Resta, R. Orbital Magnetization in Periodic Insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 137205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresoli, D.; Thonhauser, T.; Vanderbilt, D.; Resta, R. Orbital magnetization in crystalline solids: Multi-band insulators, Chern insulators, and metals. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 024408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Vignale, G.; Xiao, D.; Niu, Q. Quantum Theory of Orbital Magnetization and Its Generalization to Interacting Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 197202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.; Vanderbilt, D. Dichroic f-sum rule and the orbital magnetization of crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 054438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, Y.; Nakao, H.; Arima, T.h. Augmented Magnetic Octupole in Kagomé 120-degree Antiferromagnets Detectable via X-ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 083703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Kusunose, H. Essential role of the anisotropic magnetic dipole in the anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, L180407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimata, M.; Sasabe, N.; Kurita, K.; Yamasaki, Y.; Tabata, C.; Yokoyama, Y.; Kotani, Y.; Ikhlas, M.; Tomita, T.; Amemiya, K.; et al. X-ray study of ferroic octupole order producing anomalous Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasabe, N.; Kimata, M.; Nakamura, T. Presence of X-Ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism Signal for Zero-Magnetization Antiferromagnetic State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 157402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgata, S.; Hayami, S. Intrinsic anomalous Hall effect under anisotropic magnetic dipole versus conventional magnetic dipole. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 014421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovik, V.; Cheshkov, A. Multipole expansion in classical and quantum field theory and radiation. Sov. J. Part. Nucl 1975, 5, 318–337. [Google Scholar]

- Dubovik, V.; Tugushev, V. Toroid moments in electrodynamics and solid-state physics. Phys. Rep. 1990, 187, 145–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlinka, J. Eight Types of Symmetrically Distinct Vectorlike Physical Quantities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 165502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlinka, J.; Privratska, J.; Ondrejkovic, P.; Janovec, V. Symmetry Guide to Ferroaxial Transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 177602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.W.; Lim, S.; Du, K.; Huang, F.T. Permutable SOS (symmetry operational similarity). npj Quantum Mater. 2021, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.W.; Huang, F.T.; Kim, M. Linking emergent phenomena and broken symmetries through one-dimensional objects and their dot/cross products. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2022, 85, 124501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasu, J.; Hayami, S. Antisymmetric thermopolarization by electric toroidicity. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 245125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Guimarães, M.H.D.; Sławińska, J. Unconventional spin Hall effects in nonmagnetic solids. Phys. Rev. Materials 2022, 6, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inda, A.; Hayami, S. Nonlinear Transverse Magnetic Susceptibility under Electric Toroidal Dipole Ordering. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 92, 043701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Drueke, E.; Li, S.; Admasu, A.; Owen, R.; Day, M.; Sun, K.; Cheong, S.W.; Zhao, L. Observation of a ferro-rotational order coupled with second-order nonlinear optical fields. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, T.; Uemura, Y.; Kimura, K.; Matsuoka, S.; Hagihala, M.; Hirose, S.; Morioka, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Kimura, T. Phase transition and domain formation in ferroaxial crystals. Phys. Rev. Materials 2021, 5, 124409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, T.; Uemura, Y.; Kimura, K.; Matsuoka, S.; Morikawa, D.; Hirose, S.; Tsuda, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Kimura, T. Visualization of ferroaxial domains in an order-disorder type ferroaxial crystal. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, H.; Hayashida, T.; Kitahara, D.; Kimura, T. Three-dimensional imaging of ferroaxial domains using circularly polarized second harmonic generation microscopy. npj Quantum Mater. 2022, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Yoshida, W.; Nakamura, K.; Ogita, N.; Matsuhira, K. Raman Scattering Investigation of Structural Transition in Ca5Ir3O12. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 054602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanate, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Hayami, S.; Tsutsui, S.; Kawano, S.; Matsuhira, K. First Observation of Superlattice Reflections in the Hidden Order at 105 K of Spin–Orbit Coupled Iridium Oxide Ca5Ir3O12. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 063702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Tsutsui, S.; Hanate, H.; Nagasawa, N.; Yoda, Y.; Matsuhira, K. Cluster Toroidal Multipoles Formed by Electric-Quadrupole and Magnetic-Octupole Trimers: A Possible Scenario for Hidden Orders in Ca5Ir3O12. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 92, 033702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanate, H.; Tsutsui, S.; Yajima, T.; Nakao, H.; Sagayama, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Matsuhira, K. Space-Group Determination of Superlattice Structure Due to Electric Toroidal Ordering in Ca5Ir3O12. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 92, 063601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, F.T.; Admasu, A.S.; Kratochvílová, M.; Chu, M.W.; Park, J.G.; Cheong, S.W. Multiple ferroic orders and toroidal magnetoelectricity in the chiral magnet BaCoSiO4. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 184407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inda, A.; Hayami, S. Emergent cross-product-type spin-orbit coupling under ferroaxial ordering. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, L041104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).