Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Evolving Landscape of Organizational Sustainability

1.1. Problem Statement and Research Gap

1.2. Research Objectives

- To develop and empirically test an integrated theoretical framework connecting psychological sustainability constructs across individual, leadership, and systems levels

- To identify the psychological constructs most strongly associated with organizational sustainability outcomes across varied contexts

- To examine how contextual factors moderate the relationships between psychological sustainability practices and organizational outcomes

- To identify implementation challenges and potential strategies for enhancing psychological sustainability in organizations

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Historical Development of Psychological Sustainability Concepts

2.2. Key Psychological Constructs: Definitions and Boundaries

2.3. Integrated Theoretical Framework

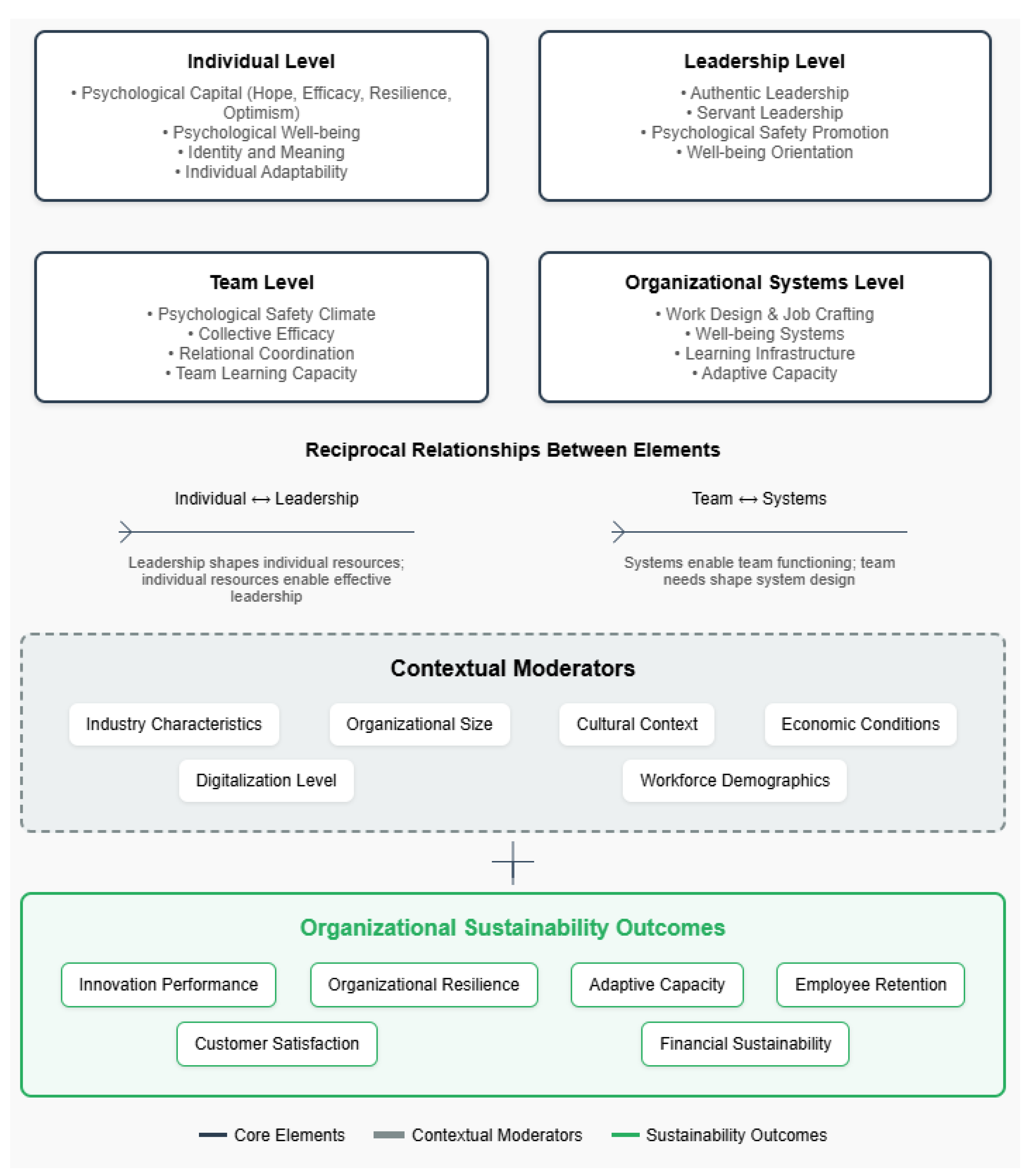

- Reinforcing cycles: The bidirectional arrows in the model represent potential reciprocal relationships, where elements may mutually reinforce each other. For example, psychological safety may enable the development of psychological capital by creating environments where learning from failure is encouraged, while psychological capital may contribute to psychological safety by providing individuals with the confidence to take interpersonal risks.

- Resource conservation and expansion: Drawing on Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), the framework suggests that psychological resources can buffer against demands and stressors, while also creating opportunities for resource expansion. This helps explain why organizations with strong psychological foundations may demonstrate greater resilience during disruption.

- Contextual activation: Different contextual factors may activate or amplify the influence of specific psychological elements. For example, the association between psychological safety and innovation may be stronger in knowledge-intensive industries where idea generation and risk-taking are crucial for success.

2.4. Research Questions

- What psychological constructs show the strongest associations with organizational sustainability outcomes across varied contexts?

- How do leadership practices appear to be associated with the development of psychological sustainability?

- What implementation barriers do organizations face when attempting to cultivate psychological sustainability?

- How do contextual factors moderate the relationships between psychological sustainability practices and organizational outcomes?

3. Methodology

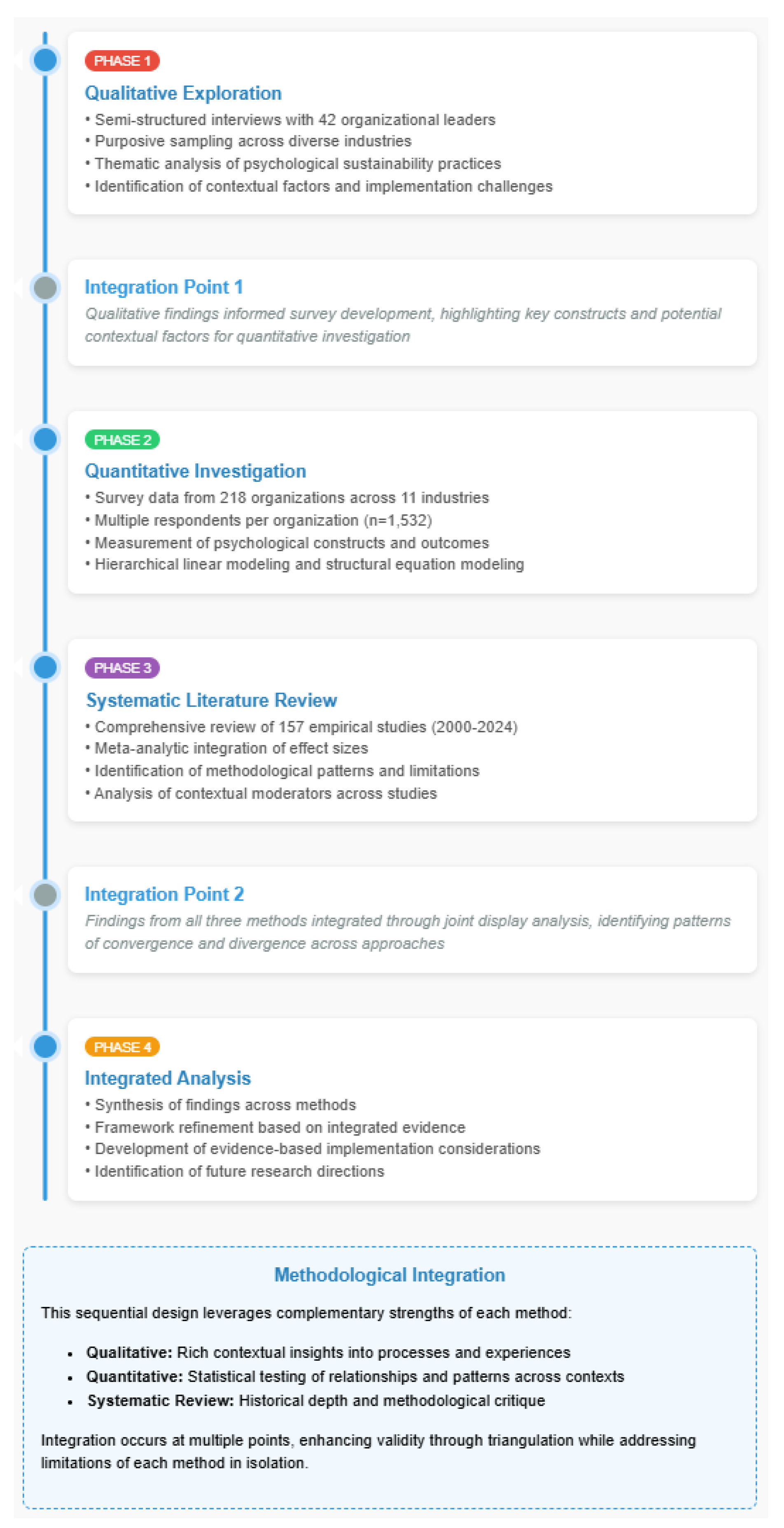

3.1. Research Design

- Qualitative interviews with 42 organizational leaders across diverse industries to explore experiences and practices related to psychological sustainability (Phase 1)

- Quantitative survey data from 218 organizations spanning 11 industries, collecting measures of psychological constructs and organizational outcomes (Phase 2)

- Systematic literature review of 157 empirical studies published between 2000-2024 examining psychological dimensions of organizational functioning (Phase 3)

3.2. Qualitative Methods

3.2.1. Participants and Sampling

- 16 C-suite executives (8 female, 8 male)

- 14 senior HR leaders (9 female, 5 male)

- 12 middle managers (5 female, 7 male)

3.2.2. Interview Protocol and Data Collection

- “How would you describe the psychological climate of your organization?”

- “What practices have you found most effective in developing psychological resources?”

- “What barriers have you encountered when implementing these approaches?”

- “How do industry and organizational factors influence these practices?”

3.2.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

- Development of a detailed codebook with definitions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and exemplars

- Regular peer debriefing sessions to challenge emerging interpretations

- Negative case analysis to refine themes

- Maintenance of an audit trail documenting analytical decisions

- Presentation of preliminary findings to a subset of participants (n=7) for feedback

3.2.4. Researcher Reflexivity

3.3. Quantitative Methods

3.3.1. Participants and Sampling

3.3.2. Measures

- Turnover rates (voluntary and involuntary, from HR records)

- Financial performance (ROA, revenue growth, from annual reports and financial databases)

- Public recognition (awards, rankings) related to workplace quality

3.3.3. Survey Administration and Data Collection

- Temporal separation between predictor and outcome measures

- Different response formats across measures

- Counterbalancing of question order

- Assurance of anonymity and confidentiality

- Elimination of ambiguous or complex items during pilot testing

3.3.4. Quantitative Analysis

- Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables

- HLM analyses testing direct relationships between psychological constructs and outcomes

- Path analysis testing the relationships proposed in the theoretical framework

- Moderation analyses examining contextual effects

- Structural equation modeling (SEM) assessing the overall fit of the theoretical model

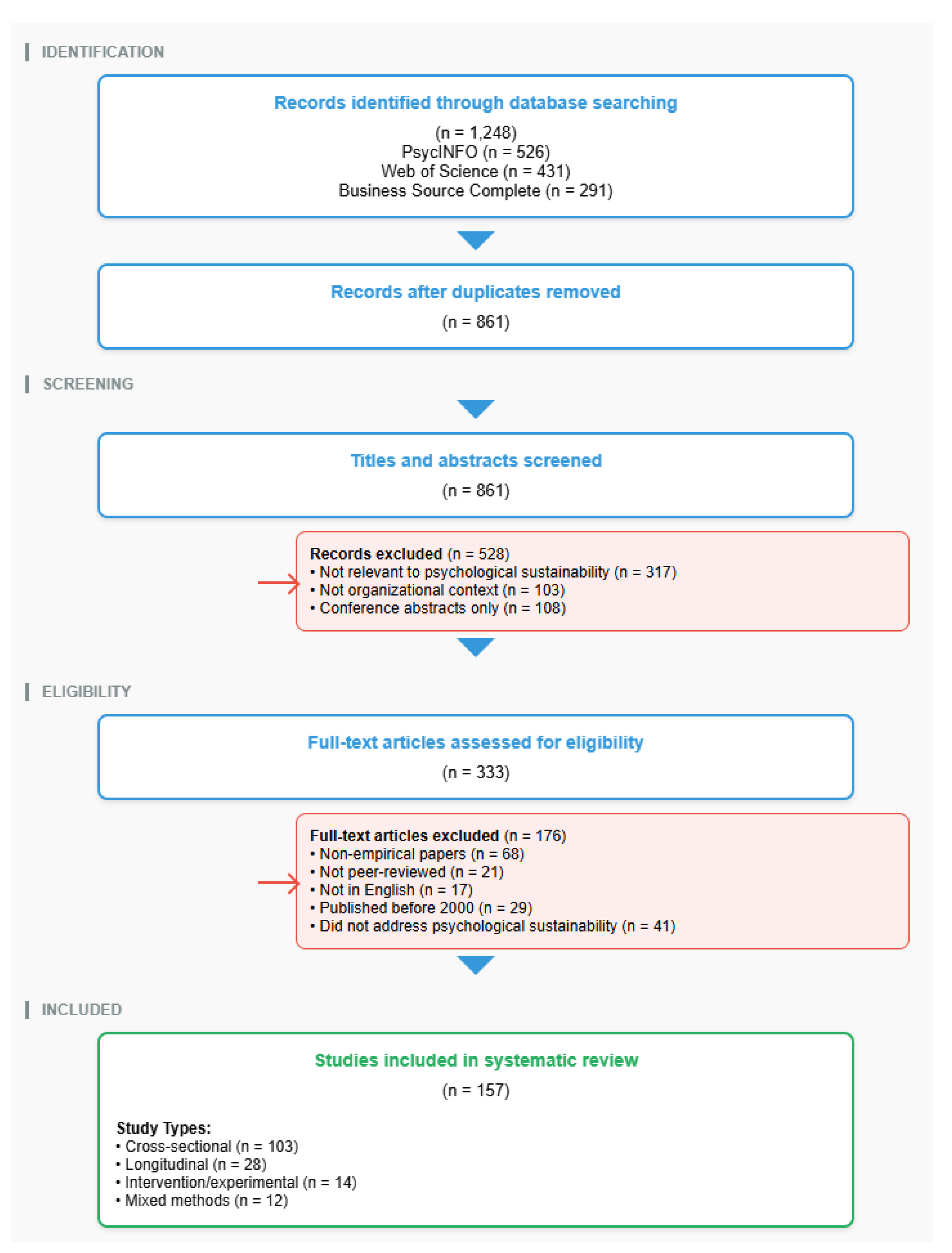

3.4. Systematic Literature Review

3.4.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

- Psychological terms: “psychological safety,” “psychological capital,” “psychological well-being,” “positive psychology”

- Organizational terms: “organization*,” “workplace,” “employee,” “leadership”

- Sustainability terms: “sustain*,” “resilience,” “adaptation,” “long-term”

- Non-empirical (theoretical, review, or commentary papers) (n=68)

- Not peer-reviewed (n=21)

- Not in English language (n=17)

- Published before 2000 (n=29)

- Did not substantially address psychological sustainability constructs (n=41)

3.4.2. Coding and Analysis

- Study characteristics (design, sample, methods)

- Psychological constructs examined

- Measures used

- Organizational outcomes assessed

- Contextual factors examined

- Effect sizes and statistical findings

- Methodological quality indicators

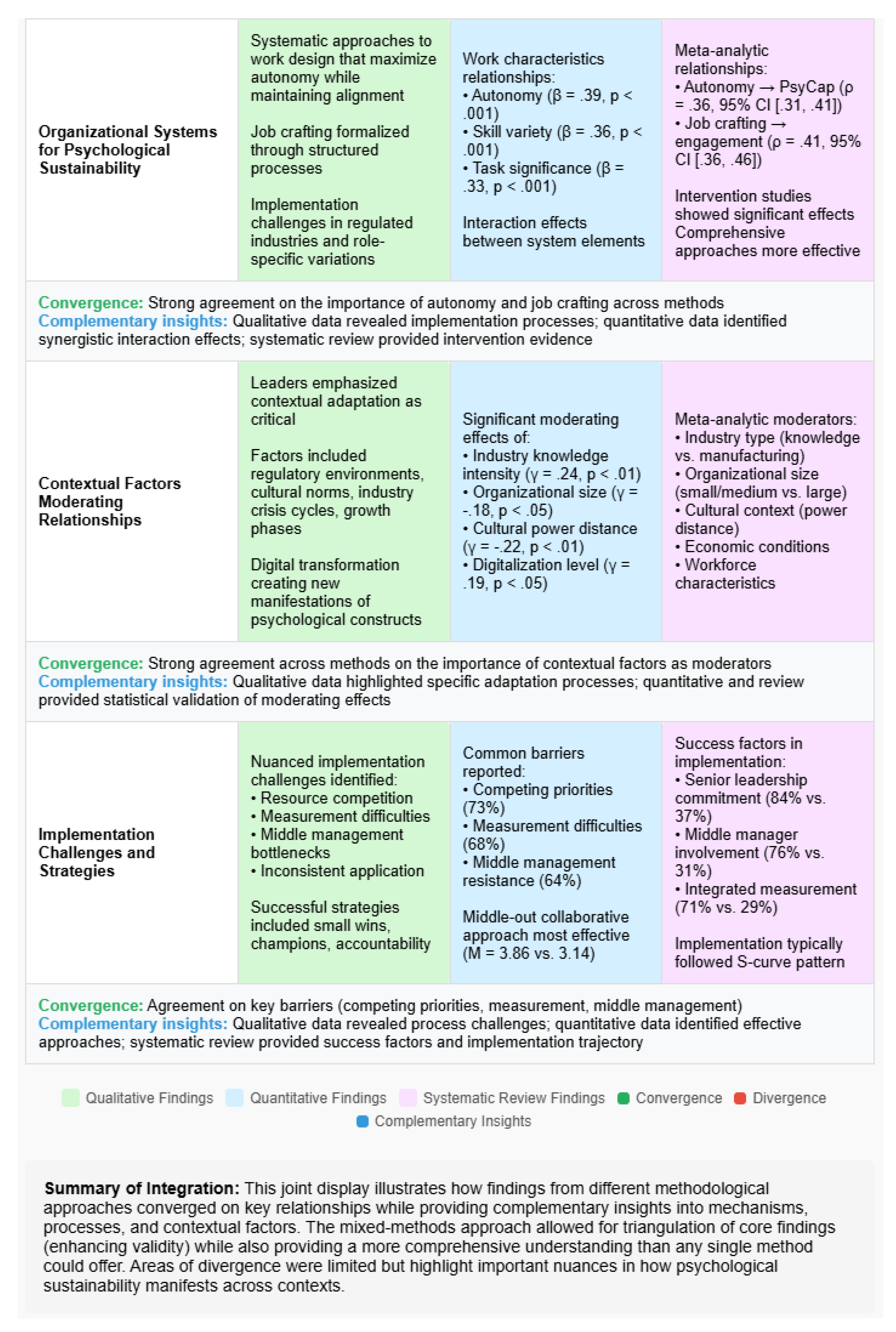

3.5. Integrated Analysis

- Creation of a joint display matrix organizing findings by key themes

- Identification of patterns of confirmation, expansion, and discordance across methods

- Examination of meta-inferences that emerge from the combined evidence

- Critical analysis of how different methods illuminated different aspects of the phenomenon

3.6. Limitations of Research Design

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Psychological Safety and Organizational Outcomes

4.2.1. Quantitative Findings

4.2.2. Qualitative Findings

- Normalizing failure through structured debriefs

- Modeling vulnerability from senior leadership

- Separating idea generation from evaluation

- Creating forums specifically designed for constructive dissent

4.2.3. Systematic Review Findings

4.3. Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap) and Resilience

4.3.1. Quantitative Findings

4.3.2. Qualitative Findings

- Developmental challenges that build efficacy through progressive mastery

- Scenario planning practices that develop pathways thinking (hope)

- Storytelling about organizational recovery from setbacks (resilience)

- Recognition practices that highlight progress toward goals (optimism)

4.3.3. Systematic Review Findings

4.4. Leadership Approaches and Psychological Sustainability

4.4.1. Quantitative Findings

4.4.2. Qualitative Findings

- Regular developmental conversations separate from performance evaluation

- Leadership vulnerability through acknowledgment of mistakes and uncertainties

- Delegation of meaningful decision authority, not just tasks

- Inclusive decision processes that incorporate diverse perspectives

4.4.3. Systematic Review Findings

4.5. Organizational Systems Supporting Psychological Sustainability

4.5.1. Quantitative Findings

4.5.2. Qualitative Findings

- Quarterly “craft your job” conversations between managers and employees

- Role adaptation processes that formalize employee-initiated changes

- Cross-training programs that allow exploration of new responsibilities

- Decision authority frameworks that clarify autonomy boundaries

4.5.3. Systematic Review Findings

4.6. Contextual Factors Moderating Psychological Sustainability

4.6.1. Quantitative Findings

- Industry knowledge intensity moderated the relationship between psychological safety and innovation (γ = .24, p < .01, 95% CI [.18, .30]), with stronger relationships in knowledge-intensive industries

- Organizational size moderated the relationship between leadership approaches and psychological safety (γ = -.18, p < .05, 95% CI [-.24, -.12]), with stronger relationships in smaller organizations

- Cultural power distance moderated the relationship between job crafting and engagement (γ = -.22, p < .01, 95% CI [-.28, -.16]), with stronger relationships in low power distance contexts

- Digitalization level moderated the relationship between well-being systems and outcomes (γ = .19, p < .05, 95% CI [.13, .25]), with stronger relationships in highly digitalized organizations

4.6.2. Qualitative Findings

- Regulatory environments that constrain certain practices

- Local cultural norms around hierarchy and communication

- Industry crisis cycles that affect psychological resource availability

- Organizational growth phases that create distinctive challenges

- Workforce demographics that influence reception of practices

4.6.3. Systematic Review Findings

- Industry type: Knowledge work (ρ = .42, 95% CI [.37, .47]) vs. manufacturing (ρ = .31, 95% CI [.26, .36]) vs. service (ρ = .35, 95% CI [.30, .40]); Q = 8.83, p < .01

- Organizational size: Small/medium (ρ = .39, 95% CI [.34, .44]) vs. large (ρ = .29, 95% CI [.24, .34]); Q = 6.21, p < .05

- Cultural context: Low power distance (ρ = .41, 95% CI [.36, .46]) vs. high power distance (ρ = .29, 95% CI [.24, .34]); Q = 7.65, p < .01

- Economic conditions: Growth periods (ρ = .34, 95% CI [.29, .39]) vs. contraction periods (ρ = .41, 95% CI [.36, .46]); Q = 4.12, p < .05

- Workforce characteristics: Professional/knowledge workers (ρ = .38, 95% CI [.33, .43]) vs. frontline workers (ρ = .29, 95% CI [.24, .34]); Q = 5.45, p < .05

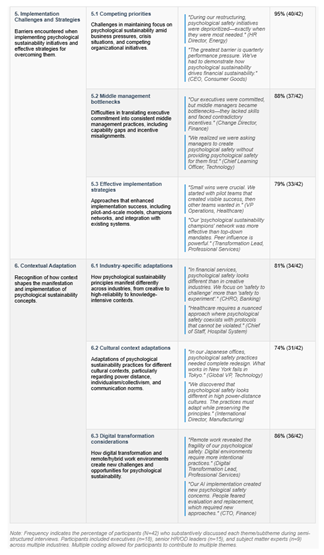

4.7. Implementation Challenges and Strategies

4.7.1. Quantitative Findings

4.7.2. Qualitative Findings

- Resource competition: “The urgent constantly crowds out the important, and psychological sustainability initiatives often fall into the ‘important but not urgent’ quadrant” (P5, Technology)

- Measurement difficulties: “We know these things matter, but quantifying their impact in ways that satisfy our finance team is incredibly difficult” (P18, Manufacturing)

- Middle management bottlenecks: “Our senior leaders get it, our frontline employees want it, but our middle managers are caught in the middle with competing priorities” (P29, Healthcare)

- Inconsistent application: “The hardest part is consistent execution across different managers, departments, and locations” (P34, Retail)

- Starting with small, visible wins to build momentum

- Connecting psychological initiatives directly to business outcomes

- Identifying and supporting internal champions

- Building measurement approaches that capture both leading and lagging indicators

- Creating explicit accountability for psychological sustainability metrics

4.7.3. Systematic Review Findings

- Senior leadership commitment demonstrated through resource allocation (found in 84% of successful implementations vs. 37% of unsuccessful ones; χ² = 23.6, p < .001)

- Middle manager involvement in design and adaptation (76% vs. 31%; χ² = 19.4, p < .001)

- Measurement approaches that captured both process and outcome indicators (71% vs. 29%; χ² = 17.2, p < .001)

- Adaptation processes that allowed for contextual customization (68% vs. 26%; χ² = 16.8, p < .001)

- Integration with existing organizational systems rather than standalone programs (74% vs. 35%; χ² = 18.3, p < .001)

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Alternative Theoretical Explanations

- Common cause factors: Both psychological sustainability and organizational outcomes might be influenced by unmeasured third variables such as industry growth, resource abundance, or organizational legacy factors. While the analyses controlled for some potential confounds, others may remain.

- Reverse causality: Organizations experiencing success may have more resources to invest in psychological sustainability, rather than psychological sustainability driving success. The predominantly cross-sectional nature of much of the data limits causal inferences.

- Institutional isomorphism: Organizations might adopt psychological sustainability practices for legitimacy reasons rather than effectiveness, with any performance benefits being incidental (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The observed contextual variations make this explanation less plausible but still possible in some cases.

- Confirmation bias in measurement: Leaders invested in psychological approaches might perceive better outcomes due to confirmation bias rather than actual effects. The multi-source data collection helps mitigate but does not eliminate this possibility.

5.3. Practical Implications

- Conduct a Psychological Sustainability Assessment: Assess current levels of psychological safety, psychological capital, leadership approaches, and supporting systems to identify strengths and gaps.

- Map Contextual Factors: Analyze industry, structural, and cultural factors that may moderate the effectiveness of psychological sustainability practices in your specific context.

- Consider Starting with Psychological Safety: Given its foundational role, psychological safety interventions may be particularly important, especially in knowledge-intensive contexts where its associations with outcomes appear strongest.

- Develop Leader Capabilities: Investments in developing authentic and servant leadership capabilities may be valuable, particularly at middle management levels where implementation bottlenecks often occur.

- Design for Autonomy and Meaning: Review work design to increase autonomy, skill variety, and task significance—the work characteristics most strongly associated with psychological sustainability.

- Consider Implementing Structured Job Crafting: Formal processes for job crafting that balance employee initiative with organizational requirements may enhance engagement.

- Build Comprehensive Well-being Systems: Integrated approaches addressing multiple well-being dimensions rather than fragmented programs appear to show stronger associations with outcomes.

- Establish Measurement Systems: Metrics that capture both psychological processes and tangible outcomes may help build the business case for sustainability investments.

- Pilot and Adapt: Pilot implementations can test approaches before organization-wide rollout, with explicit adaptation processes to fit local contexts.

- Create Vertical Alignment: Consistency between senior leadership messaging, management practices, and frontline experiences may help avoid implementation gaps.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

- Extended Longitudinal Studies: Track psychological sustainability implementations over longer timeframes (3-5 years) to better understand developmental trajectories and sustainability of effects.

- Cross-Cultural Expansion: Extend research into more diverse cultural contexts, particularly high power distance and collectivist settings where psychological constructs may manifest differently.

- Multi-stakeholder Perspective: Incorporate external stakeholder perspectives to understand how psychological sustainability affects and is affected by relationships with customers, communities, and suppliers.

- Digital Context Exploration: Examine how psychological sustainability functions in increasingly digital and hybrid work environments, including remote and distributed teams.

- Intervention Studies: Conduct randomized controlled trials of specific psychological sustainability interventions to establish causal effects and boundary conditions.

- Measurement Refinement: Develop and validate more precise measurement approaches for psychological constructs in organizational settings, particularly tools suitable for regular monitoring.

- Identity and Diversity Focus: Examine how psychological sustainability practices are experienced differently based on gender, race, age, and other identity dimensions.

- Negative Consequences: Investigate potential negative consequences or limitations of psychological sustainability approaches to develop more balanced understanding.

6. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aarons, G. A. , Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 11-28.

- Accenture. (2022). Truly human at Accenture: Creating a culture of psychological safety and well-being. Accenture Insights, 13(4), 78-95.

- Allan, B. A. , Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500-528.

- Avey, J. B. , Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127-152.

- Avolio, B. J. , & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315-338.

- Bailey, C. , Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., & Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 83-113.

- Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273-285.

- Bamberger, P. (2008). Beyond contextualization: Using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 839-846.

- Barley, S. R. , Treem, J. W., & Kuhn, T. (2022). Valuing time: Digital overload and the rhythms of academic life. Academy of Management Discoveries, 8(1), 56-77.

- Bartlett, C. A. , & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Building organizational and cultural contexts for effectiveness. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Batistič, S. , Černe, M., Kaše, R., & Zupic, I. (2023). Twenty-five years of human resource management research: A bibliometric review and future research directions. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(5), 965-997.

- Bauer, M. S. , Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 32-44.

- Bernstein, E. S. , & Turban, S. (2018). The impact of the ‘open’ workspace on human collaboration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1753), 20170239.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597.

- Carnevale, J. B. , & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183-187.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cooper, C. L. , Quick, J. C., & Schabracq, M. J. (2019). International handbook of work and health psychology (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cram, W. A. , & Wiener, M. (2020). Technology-mediated control: Case evidence and research directions for the future of organizational control. Journal of Information Technology, 35(1), 56-80.

- Creswell, J. W. , & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Dagenais-Desmarais, V. , & Savoie, A. (2012). What is psychological well-being, really? A grassroots approach from the organizational sciences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(4), 659-684.

- Damschroder, L. J. , Reardon, C. M., Opra Widerquist, M. A., & Lowery, J. (2022). Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The CFIR outcomes addendum. Implementation Science, 17(1), 1-10.

- Deci, E. L. , & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: A few comments. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 24-29.

- Demerouti, E. , Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. (2020). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103470.

- DiMaggio, P. J. , & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

- Dreison, K. C. , Luther, L., Bonfils, K. A., Sliter, M. T., McGrew, J. H., & Salyers, M. P. (2018). Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 18-30.

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

- Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons.

- Edmondson, A. C. , & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23-43.

- Eva, N. , Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111-132.

- Fetters, M. D. , Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134-2156.

- Filev, A. (2022). Building psychological safety in a global, all-remote organization: Lessons from GitLab. Harvard Business Review, 100(4), 64-71.

- Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384-412.

- Flamholtz, E. , & Randle, Y. (2016). Growing pains: Building sustainably successful organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ford, M. T. , Wang, Y., Jin, J., & Eisenberger, R. (2018). Chronic and episodic anger and gratitude toward the organization: Relationships with organizational and supervisor supportiveness and extrarole behavior. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 175-187.

- Frazier, M. L. , Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113-165.

- Funder, D. C. , & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156-168.

- Gallup. (2023). Gallup global wellbeing report. Gallup, Inc.

- Gelfand, M. J. , Aycan, Z., Erez, M., & Leung, K. (2017). Cross-cultural industrial organizational psychology and organizational behavior: A hundred-year journey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 514-529.

- Gittell, J. H. , & Bamber, G. J. (2022). Sustaining high-road employment systems: Positive relationships at Southwest Airlines. In Positive Organizational Relationships (pp. 235-257). Routledge.

- Goleman, D. , Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2013). Primal leadership: Unleashing the power of emotional intelligence. Harvard Business Press.

- Grandey, A. A. , & Melloy, R. C. (2017). The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 407-422.

- Grawitch, M. J. , Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129-147.

- Grossmeier, J., Fabius, R., Flynn, J. P., Noeldner, S. P., Fabius, D., Goetzel, R. Z., & Anderson, D. R. (2016). Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(1), 16-23.

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0232076.

- Harms, P. D. , & Luthans, F. (2012). Measuring implicit psychological constructs in organizational behavior: An example using psychological capital. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 589-594.

- Hartwell, M., Keener, A., Coffey, S., Chesher, T., Torgerson, T., & Vassar, M. (2021). Brief interventions to promote meaning and purpose in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 785-792.

- Harvard Business Review. (2022). The future of team connection: Technology for building relationships in the hybrid workplace. Harvard Business Review Analytic Services.

- Herschcovis, M. S. , & Barling, J. (2010). Towards a multi-foci approach to workplace aggression: A meta-analytic review of outcomes from different perpetrators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 24-44.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285-291.

- House, R. J. , Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. J., & de Luque, M. F. S. (2014). Strategic leadership across cultures: GLOBE study of CEO leadership behavior and effectiveness in 24 countries. SAGE Publications.

- House, R. J. , Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications.

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635-672.

- Johns, G. (2018). Advances in the treatment of context in organizational research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 21-46.

- Johnson, R. B. , Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112-133.

- Johnson & Johnson. (2022). The evolution of workplace wellbeing programs: Lessons from global implementation. Johnson & Johnson Health and Wellness Solutions.

- Kantur, D. , & Say, A. I. (2015). Measuring organizational resilience: A scale development. Journal of Business Economics and Finance, 4(3), 456-472.

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285-308.

- Kellogg, K. C. , Valentine, M. A., & Christin, A. (2020). Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 366-410.

- Kern, M. L. (2014). The workplace PERMA profiler. University of Pennsylvania.

- Klein, K. J. , & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2000). From micro to meso: Critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(3), 211-236.

- Kompier, M. , Yang, S., Ilies, R., & Van Hooff, M. (2022). Implementing occupational health interventions: Context matters! Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(3), 316-332.

- Kossek, E. E. , & Lautsch, B. A. (2018). Work–life flexibility for whom? Occupational status and work–life inequality in upper, middle, and lower level jobs. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 5-36.

- Kossek, E. E. , Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2021). Work–nonwork boundary management profiles in two cultures: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 122, 103472.

- Lee, M. Y. , & Edmondson, A. C. (2017). Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37, 35-58.

- Liden, R. C. , Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434-1452.

- Liu, S. , Jiang, K., Chen, J., Pan, J., & Lin, X. (2020). Linking employee boundary spanning behavior to task performance and the boundary spanning context: The mediating role of employee well-being. Personnel Psychology, 73(4), 695-738.

- Liu, Y. , Cooper, C. L., & Tarba, S. Y. (2022). Resilience, wellbeing and HRM: A multidisciplinary perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(6), 1060-1082.

- Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 695-706.

- Luthans, F. , Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541-572.

- Luthans, F. , Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press.

- Lysova, E. I. , Allan, B. A., Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Steger, M. F. (2019). Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 374-389.

- Marquis, C. , & Villa, M. A. (2022). TOMS Shoes: Scaling social mission during business model evolution. Harvard Business School Case Study.

- Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Prentice-Hall.

- Maslach, C. , & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103-111.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

- Mayo, E. (1933). The human problems of an industrial civilization. Macmillan.

- McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. McGraw-Hill.

- McKinsey & Company. (2020). Organizational Health Index: A technical manual. McKinsey & Company, Inc.

- Miao, C. , Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2021). Emotional intelligence and servant leadership: A meta-analytic review. Business Ethics: A European Review, 30(2), 231-243.

- Mittal, S. , & Mathur, G. (2023). Cultural influence on psychological capital: A comparative study of collectivist and individualist contexts. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 30(2), 307-332.

- Morgeson, F. P. , & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321-1339.

- Morris, L. , & Fry, R. (2021). Adobe’s journey to reimagining performance management. Harvard Business School Case Study.

- Neeley, T. B. , & Leonardi, P. M. (2022). The digital matrix: Mapping the technological ties that bind us. Research in Organizational Behavior, 42, 100153.

- Neumann, N. , Wagner, D., & Mell, J. N. (2022). The paradox of connectivity: How digital technology can both decrease and increase perceptions of distance in distributed work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(1), 143-160.

- Newman, A. , Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521-535.

- Nielsen, K. , Christensen, M., Nygaard Jensen, L., & Finne, L. B. (2021). Integrating and addressing occupational health and wellbeing: Setting an agenda for knowledge translation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(6), 777-781.

- Nielsen, K. , & Randall, R. (2013). Opening the black box: Presenting a model for evaluating organizational-level interventions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(5), 601-617.

- Nielsen, K. , Dawson, J., Hasson, H., & von Thiele Schwarz, U. (2021). What about me? The impact of employee change agents’ person-role fit on their job satisfaction during organisational change. Work & Stress, 35(1), 57-73.

- Nielsen, M. B. , Christensen, J. O., Finne, L. B., & Knardahl, S. (2022). Psychological safety climate as a predictor of mental health at work: A 2-year follow-up study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(4), 853-862.

- O’Rourke, D. , & Strand, R. (2022). Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions. California Management Review, 64(1), 187-206.

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S.,... Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71.

- Parker, S. K. , & Grote, G. (2022). Automation, algorithms, and beyond: Why work design matters more than ever in a digital world. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 93-126.

- Parker, S. K. , Morgeson, F. P., & Johns, G. (2017). One hundred years of work design research: Looking back and looking forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 403-420.

- Perlow, L. A. , & Porter, J. L. (2017). Making time off predictable—and required. Harvard Business Review, 95(5), 106-113.

- Pfeffer, J. (2018). Dying for a paycheck: How modern management harms employee health and company performance—and what we can do about it. HarperCollins.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539-569.

- Pugh, D. S., Hickson, D. J., Hinings, C. R., & Turner, C. (1968). Dimensions of organization structure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 13(1), 65-105.

- Ramarajan, L. , & Roberts, L. M. (2022). Positive identity construction at work: A review and theoretical integration. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 259-286.

- Rockmann, K. W. , & Pratt, M. G. (2022). Technology and the sense of being there: Virtuality, physicality, and identity in the modern workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 177-201.

- Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Simon and Schuster.

- Rothmann, S. (2022). Flourishing at work: A southern perspective. In Positive Psychological Intervention Design and Protocols for Multi-Cultural Contexts (pp. 315-342). Springer.

- Rudolph, C. W. , Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112-138.

- Ryff, C. D. , & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727.

- Schein, E. H. , & Schein, P. A. (2016). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Schneider, B. , Yost, A. B., Kropp, A., Kind, C., & Lam, H. (2018). Workforce engagement: What it is, what drives it, and why it matters for organizational performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 462-480.

- Schyns, B. , & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138-158.

- Scott, S. G. , & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580-607.

- Seligman, M. E. , & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

- Shanafelt, T. D. , & Noseworthy, J. H. (2017). Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(1), 129-146.

- Shanafelt, T. , Trockel, M., Ripp, J., Murphy, M. L., Sandborg, C., & Bohman, B. (2021). Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Academic Medicine, 96(4), 540-548.

- Spreitzer, G. M. , Cameron, L., & Garrett, L. (2021). Designing work, working better, and living well: The role of work design in human thriving. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management, 1-38.

- Steger, M. F. , Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322-337.

- Steiber, A. , & Alänge, S. (2020). Corporate-startup co-creation for increased innovation and societal change. Triple Helix, 7(2-3), 198-226.

- Sutcliffe, K. M., Vogus, T. J., & Dane, E. (2020). Mindfulness in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7, 213-238.

- Taris, T. W. , Leisink, P. L., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2023). A balanced job demands-resources model: A systematic review and revised conceptual model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1065556.

- Tate, R. (2023). Does Google’s “20% time” still exist? An organizational ethnography of evolving innovation practices. Research Policy, 52(4), 104694.

- Taylor, F. W. (1911). The principles of scientific management. Harper & Brothers.

- Unilever. (2023). Wellbeing framework impact assessment: Five-year longitudinal study results. Unilever Sustainable Living Report.

- van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1228-1261.

- van Dierendonck, D. , & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 249-267.

- van Woerkom, M. , & Meyers, M. C. (2019). Strengthening personal growth: The effects of a strengths intervention on personal growth initiative. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(1), 98-121.

- Vogus, T. J. , & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2021). Organizational mindfulness: Towards theoretical clarity and new directions for research. Academy of Management Annals, 15(2), 1-35.

- Vogus, T. J. , Rothman, N. B., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Weick, K. E. (2021). The affective foundations of high-reliability organizing. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(3), 260-276.

- Walumbwa, F. O. , Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89-126.

- Wang, B. , Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16-59.

- Wartzman, R. (2022). Microsoft’s turnaround under Satya Nadella. Harvard Business Review, 100(5), 142-149.

- Weick, K. E. , & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Wrzesniewski, A. , & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179-201.

- Wrzesniewski, A., Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2022). Job crafting and the cultivation of meaningful work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 42, 100159.

- Wu, C. M. , & Nguyen, N. T. (2021). The antecedents and consequences of psychological capital: A meta-analytic approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(6), 982-1003.

- Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., Weston, J., Joyce, C., Shah, N., Sherman, K., Hecht, B., & Teevan, J. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 43-54.

- Youssef-Morgan, C. M. , & Luthans, F. (2013). Positive leadership: Meaning and application across cultures. Organizational Dynamics, 42(3), 198-208.

| Construct | Definition | Key Measurements | Conceptual Distinctions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Safety | Shared belief that team/organization is safe for interpersonal risk-taking | Team Psychological Safety Survey (Edmondson, 1999) Psychological Safety Scale (Newman et al., 2017) |

Distinct from physical safety climate and psychological security; operates primarily at team/collective level vs. individual |

| Psychological Capital | Individual’s positive psychological state of development (hope, efficacy, resilience, optimism) | PCQ-24 (Luthans et al., 2007) Implicit PsyCap Questionnaire (Harms & Luthans, 2012) |

Distinct from human capital and social capital; state-like (developable) rather than trait-like; can be aggregated to team/org level |

| Psychological Well-being | Multidimensional construct encompassing hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of work experience | Workplace PERMA Profiler (Kern, 2014) Psychological Well-being at Work Scale (Dagenais-Desmarais & Savoie, 2012) |

Broader than job satisfaction; encompasses both pleasure/satisfaction and meaning/purpose dimensions; distinct from merely absence of distress |

| Leadership for Psychological Sustainability | Leadership approaches associated with fostering psychological resources and well-being | Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (Walumbwa et al., 2008) Servant Leadership Survey (van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) |

Focuses specifically on psychological resource development aspect of leadership vs. task/strategic dimensions |

| Organizational Systems for Psychological Sustainability | Formal and informal structures supporting psychological resources and well-being | Organizational Health Index (McKinsey, 2020) Healthy Workplace Practices Scale (Grawitch et al., 2006) |

Systems-level perspective beyond individual practices; includes formal and informal elements; addresses sustainability over time |

| Construct | Measure | Sample Item | Reliability | Validity Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Psychological Safety | Team Psychological Safety Survey (Edmondson, 1999) | “Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues” | α = .92ω = .91Test-retest r = .79 | Convergent validity with team trust (r = .65) Discriminant validity from team efficacy (r = .38) Predictive validity for learning behaviors (r = .52) |

| Psychological Capital | PCQ-24 (Luthans et al., 2007) | “I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution” | α = .94ω = .93Test-retest r = .82 | Convergent validity with optimism (r = .71) Discriminant validity from trait measures (r = .39) Predictive validity for performance (r = .45) |

| Authentic Leadership | Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | “My leader solicits feedback to improve interactions with others” | α = .91ω = .90Test-retest r = .76 | Convergent validity with ethical leadership (r = .67) Discriminant validity from LMX (r = .44) Predictive validity for trust (r = .59) |

| Servant Leadership | Servant Leadership Survey (van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) | “My manager helps me to further develop myself” | α = .93ω = .92Test-retest r = .81 | Convergent validity with transformational leadership (r = .60) Discriminant validity from transactional leadership (r = .32) Predictive validity for commitment (r = .53) |

| Work Design | Work Design Questionnaire (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) | “The job allows me to make decisions about what methods I use to complete my work” | α = .89ω = .88Test-retest r = .74 | Convergent validity with job characteristics (r = .72) Discriminant validity from personality (r = .29) Predictive validity for satisfaction (r = .56) |

| Well-being Systems | Organizational Health Index (McKinsey, 2020) | “This organization actively supports employee well-being” | α = .88ω = .87Test-retest r = .75 | Convergent validity with perceived organizational support (r = .68) Discriminant validity from climate measures (r = .41) Predictive validity for engagement (r = .49) |

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Innovation Performance | Innovation Performance Scale (Scott & Bruce, 1994) | “This team generates creative ideas” | α = .87ω = .86Test-retest r = .79 | Convergent validity with creativity measures (r = .70) Predictive validity for patents/new products (r = .41) |

| Organizational Resilience | Organizational Resilience Scale (Kantur & Say, 2015) | “We quickly adapt when unexpected changes occur” | α = .90ω = .89Test-retest r = .77 | Convergent validity with adaptability measures (r = .63) Predictive validity for recovery from disruption (r = .47) |

| Adaptive Capacity | Adaptive Capacity Scale (developed for this study) | “Our organization effectively responds to market shifts” | α = .86ω = .85Test-retest r = .74 | Convergent validity with dynamic capability measures (r = .61) Predictive validity for market share changes (r = .39) |

| Moderating Variables | ||||

| Industry Characteristics | Industry Attribute Questionnaire (developed for this study) | “Our industry requires continuous innovation to remain competitive” | α = .83ω = .82 | Factor analysis confirmed three distinct dimensions: knowledge intensity, risk profile, digitalization level |

| Organizational Structure | Structural Dimensions Survey (based on Pugh et al., 1968) | “Decision-making in our organization is highly centralized” | α = .85ω = .84 | Factor analysis confirmed centralization and formalization dimensions |

| Cultural Context | GLOBE cultural dimension scales (House et al., 2014) | “Managers in this culture are expected to be decisive and assertive” | α = .81-.89ω = .80-.87 | Established cross-cultural validity in prior research |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological Safety | 3.64 | 0.78 | (.92) | ||||||||

| 2. Psychological Capital | 3.82 | 0.67 | .42*** | (.94) | |||||||

| 3. Authentic Leadership | 3.45 | 0.84 | .51*** | .36*** | (.91) | ||||||

| 4. Servant Leadership | 3.23 | 0.92 | .47*** | .32*** | .56*** | (.93) | |||||

| 5. Work Design (Autonomy) | 3.51 | 0.76 | .38*** | .33*** | .35*** | .41*** | (.89) | ||||

| 6. Well-being Systems | 3.19 | 0.89 | .44*** | .31*** | .49*** | .52*** | .36*** | (.88) | |||

| 7. Innovation Performance | 3.42 | 0.82 | .42*** | .35*** | .29*** | .31*** | .36*** | .28*** | (.87) | ||

| 8. Organizational Resilience | 3.38 | 0.75 | .37*** | .38*** | .32*** | .34*** | .30*** | .31*** | .39*** | (.90) | |

| 9. Adaptive Capacity | 3.27 | 0.79 | .36*** | .35*** | .30*** | .33*** | .27*** | .29*** | .43*** | .56*** | (.86) |

| Contextual Factor | Relationship Moderated | Interaction Coefficient (γ) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Intensity | Psychological Safety → Innovation | .24 | [.18, .30] | < .01 |

| Knowledge Intensity | Psychological Capital → Adaptability | .21 | [.15, .27] | < .01 |

| Organizational Size | Leadership → Psychological Safety | -.18 | [-.24, -.12] | < .05 |

| Organizational Size | Well-being Systems → Outcomes | -.15 | [-.21, -.09] | < .05 |

| Power Distance | Job Crafting → Engagement | -.22 | [-.28, -.16] | < .01 |

| Power Distance | Psychological Safety → Voice | -.26 | [-.32, -.20] | < .001 |

| Digitalization Level | Well-being Systems → Outcomes | .19 | [.13, .25] | < .05 |

| Digitalization Level | Psychological Capital → Innovation | .17 | [.11, .23] | < .05 |

| Industry Volatility | Leadership → Resilience | .23 | [.17, .29] | < .01 |

| Gender Composition | Servant Leadership → Outcomes | .16 | [.10, .22] | < .05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).