Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

The Growing Importance of Sustainability for Businesses

- Resource Depletion and Climate Change: Businesses face risks and regulations. Sustainability promotes resource efficiency and climate mitigation (Moslehpour et al., 2022).

- Shifting Stakeholder Expectations: Stakeholders increasingly demand social and environmental responsibility, influencing investment, talent retention and brand loyalty (Suryasa, Rodríguez-Gámez & Koldoris, 2022).

- Regulatory Pressures: Compliance with stricter global regulations protects reputation and avoids penalties.

- Efficiency and Cost Savings: Initiatives like energy efficiency and waste reduction lower operational costs.

Team Dynamics – Engine of Sustainable Practices

- Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration: Multidisciplinary expertise enables sustainable solutions (Dincă et al., 2023).

- Shared Vision and Goal Setting: Alignment fosters accountability and shared purpose.

- Problem Solving and Innovation: Safe experimentationspaces promote innovative embedding of sustainability into processes.

- Accountability and Ownership: Teams own sustainability goals, driving improvement.

- Motivation and Engagement: Common goals and recognition of sustainability initiatives enhance commitment.

Emerging Challenges in Team Management and Need for Holistic Approach

Emerging Challenges

Need For Holistic Approach

Limitations of Traditional Team Dynamics and the Sustainability Imperative

- Short-Termism: Ignoring long-term impacts undermines sustainability.

- Rigid Leadership: Top-down control stifles innovation and ownership.

- Individual Performance Metrics: Competition limits collaborative sustainability efforts.

- Neglected Well-being: Overemphasis on output reduces team contribution to sustainability.

The Sustainability Imperative

- Resource Depletion and Climate Change: Risks from resource depletion and climate impacts necessitate sustainable, resource-efficient practices for long-term viability.

- Stakeholder Expectations: Consumers, investors, and employees increasingly demand corporate responsibility, influencing investment, talent retention, and brand loyalty.

- Regulatory Pressures: Evolving environmental regulations require proactive sustainability to avoid fines, disruptions, and reputational harm.

Strategies for Building Effective Sustainability Teams

Literature Review

Rethinking Team Dynamics in the Sustainability Era

- Shared Vision and Long-Term Goals: Integrating sustainability into core missions encourages collective commitment (Woodard et al., 2022).

- Psychological Safety and Open Dialogue: Safe environments foster innovation and surface hidden concerns.

- Diversity and Inclusion: Heterogeneity improves problem-solving in complex contexts.

- Cross-Functional Collaboration: Multidisciplinary engagement is essential for addressing sustainability challenges.

- Continuous Learning: Ongoing development supports adaptability to emerging demands.

Sustainability as a Strategic Framework

Revisiting Team Effectiveness

Emergence of Sustainable Team Dynamics

- Intergenerational Equity: Emphasis on learning and well-being sustains team viability (Melia, 2016).

- Long-Term Thinking: Aligning team goals with sustainability ensures continuity (Lam et al., 2016).

- Systems Thinking: Recognizing interdependencies promotes open collaboration (Yao & Liu, 2022).

Evolving Definitions and Trends

Value of STD for Organizations

- Innovation: Diversity and safety enhance creativity (Szromek et al., 2022).

- Purpose Alignment: Sustainability-linked objectives foster lasting purpose (Maurer, Whitman & Wright, 2023).

- Engagement: Well-being strategies improve satisfaction and reduce attrition (Sypniewska, Baran & Kłos, 2023).

- Agility: Learning cultures adapt to change (Wu, Liu, & Huang, 2022).

- Resource Optimization: Efficient, lean operations emerge from sustainable practices.

Challenges in STD Implementation

- Balancing short-term business needs with long-term sustainability.

- Creating psychologically safe spaces for diverse participation.

- Countering burnout culture to protect health and motivation.

- Developing valid measures of sustainability-oriented team performance.

Strategic Levers for Leaders

- Aligning teams with a shared vision.

- Promoting inclusion and leveraging diversity.

- Fostering empowerment and recognition.

- Facilitating continuous learning in sustainability practices.

- Using performance systems focused on long-term priorities.

Theoretical Foundations

Social Exchange Theory (SET)

- Reciprocity: Balanced exchanges reinforce mutual commitment (Xia et al., 2023).

- Trust: Consistent, supportive interactions build confidence and risk-taking.

- Commitment: Shared vision and belonging enhance persistence and creativity.

- Promoting fairness and recognition.

- Building trust through consistent leadership.

- Strengthening shared goals to foster engagement.

Tuckman’s Stages of Development

Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

Hackman’s Model

- Clear boundaries and interdependence.

- A compelling direction.

- Enabling structure and norms.

- Supportive resources, rewards and leadership.

- Expert coaching.

IPO and IMOI Models

Salas Et al.’s Team Performance Model

Dysfunction Models

Belbin’s Team Roles Model

- Thinking: Plant, Monitor Evaluator, Specialist

- Action: Shaper, Implementer, Completer Finisher

- People: Coordinator, Teamworker, Resource Investigator

Additional Models

Integrative Insights and Future Directions

Reframing Sustainability for Team Application

- Environmental: Focused on climate mitigation, biodiversity, and resource efficiency.

- Social: Concerned with justice, human rights, and access to health and education.

- Economic: Promotes long-term growth through resource efficiency, CSR, and responsible investment.

Integrating Insights from Literature

Conceptual Development: Sustainability in Team & Organization

Team Sustainability: A Contemporary Perspective

- Longevity: Maintaining functional performance over time.

- Adaptability: Embracing change and evolving work practices.

- Resilience: Recovering from setbacks to maintain cohesion and productivity.

- Ethical Conduct: Upholding integrity and contributing to broader societal and environmental good.

Sustainability in the Organizational Context

- Environmental: Resource efficiency, emissions reduction, and waste management.

- Social: Ethical labor, employee well-being, diversity and community engagement.

- Economic: Financial viability pursued responsibly.

Merging Sustainability with Team Management: Theoretical Bases

Team Dynamics and Organizational Sustainability (TDOS)

Emerging Trends at the TDOS Intersection

Key Drivers of TDOS: Empirical Insights

Leadership and Management Practices

Team Composition and Diversity

Communication and Information Sharing

Conflict Resolution and Problem Solving

Organizational Support and Resources

Integrating Sustainability Principles with Team Dynamics

Sustainability Principles Aligned with Team Dynamics

- Intergenerational Equity: Like sustainability, teams must nurture continuous learning and capability building.

- Long-Term Thinking: Sustainable teams look beyond immediate goals to enduring impact.

- Systems Thinking: Recognizing interdependence, teams adopt collaborative, cross-functional strategies.

- Resource Efficiency: Mindful use of time, talent, and tools reflects sustainable practice.

- Innovation: Teams that support experimentation and diverse inputs adapt better to complex challenges.

Linking Team Models with Sustainability

- Hackman’s IPO Model: Incorporate sustainability in inputs (team design), processes (collaboration on green goals), and outputs (triple bottom line results).

- Salas et al.’s Contextual Model: Embed sustainability into organizational influences like leadership and culture.

- Katzenbach and Smith’s Dysfunctions Model: Extend accountability to include environmental and social commitments.

- Belbin’s Roles Model: Highlight the creative and evaluative roles essential for sustainable innovation.

Practical Strategies for Building Sustainable Teams

- Shared Vision: Align team missions with sustainability goals to foster commitment.

- Diversity and Inclusion: Use heterogeneous teams to generate innovative, inclusive solutions.

- Empowerment and Recognition: Support ownership of sustainability efforts and reward contributions.

- Continuous Learning: Offer training in sustainability tools and foster knowledge sharing.

- Aligned Performance Management: Integrate sustainability metrics into team evaluations.

- Well-being Focus: Promote work-life balance to sustain motivation and reduce burnout.

- Sustainability-Oriented Leadership: Cultivate leaders who model long-term thinking and collaborative action.

Implementation Challenges

- Balancing Goals: Leaders must reconcile short-term business pressures with long-term sustainability.

- Fostering Trust: A psychologically safe climate is essential for inclusivity and risk-taking.

- Measuring Impact: Developing sustainability-aligned metrics for teams remains a work in progress.

Conceptual Development: STD

Defining STD and Its Core Attributes

- Shared Purpose and Vision: Unified goals guide team efforts (Wyatt, 2021).

- Mutual Trust and Respect: Foundation for psychological safety and open communication (Liu et al., 2023).

- Effective Communication: Ensures clarity and coordination across tasks.

- Constructive Conflict Management: Navigates disagreements productively, fostering learning and innovation (Kay & Skarlicki, 2020).

- Collective Learning and Adaptability: Supports reflection, improvement, and resilience (Folke et al., 2010).

Dimensions of STD

- Sustainable Team Leadership: Leaders model ethical conduct, empower members, and promote inclusive decision-making that builds collective ownership and accountability (Iqbal & Piwowar-Sulej, 2023).

- Sustainable Team Processes: Teams sustain performance through open communication, transparent decision-making, active listening, collaborative conflict management and a knowledge-sharing culture (McMullin & Dilger, 2021; Lewis, 2022; Yeboah, 2023).

- Sustainable Outcomes: STD is reflected in team well-being (reduced stress, satisfaction, belonging), longevity (maintaining cohesion), and adaptability (responding to shifting demands) (Ji & Yan, 2020; Torricelli & Pellati, 2023).

- Organizational Support: Adequate resources and a culture that values collaboration and development are crucial (Dimas et al., 2023; Lacerenza et al., 2018).

Emerging Literature on STD

- Sustained Performance: Continuous achievement under evolving demands.

- Member Well-being: Psychological and physical health, job satisfaction, and sense of belonging.

- Longevity and Viability: Teams that remain effective over time despite disruption.

- Adaptive Capacity: Flexibility and learning to navigate uncertainty.

Frameworks and Empirical Evidence

- Innovation and Complex Problem-Solving: Teams that feel safe and supported are better positioned to tackle sustainability challenges with creativity.

- Employee Engagement and Retention: Prioritizing well-being correlates with satisfaction and reduces attrition (Sypniewska, Baran & Kłos, 2023).

- Efficiency and Cost-Reduction: Sustainable teams make better use of resources, enhancing organizational efficiency.

- Resilience and Adaptability: Teams grounded in learning are better equipped to handle change and uncertainty.

Synthesis: Toward a Sustainable Teaming Paradigm

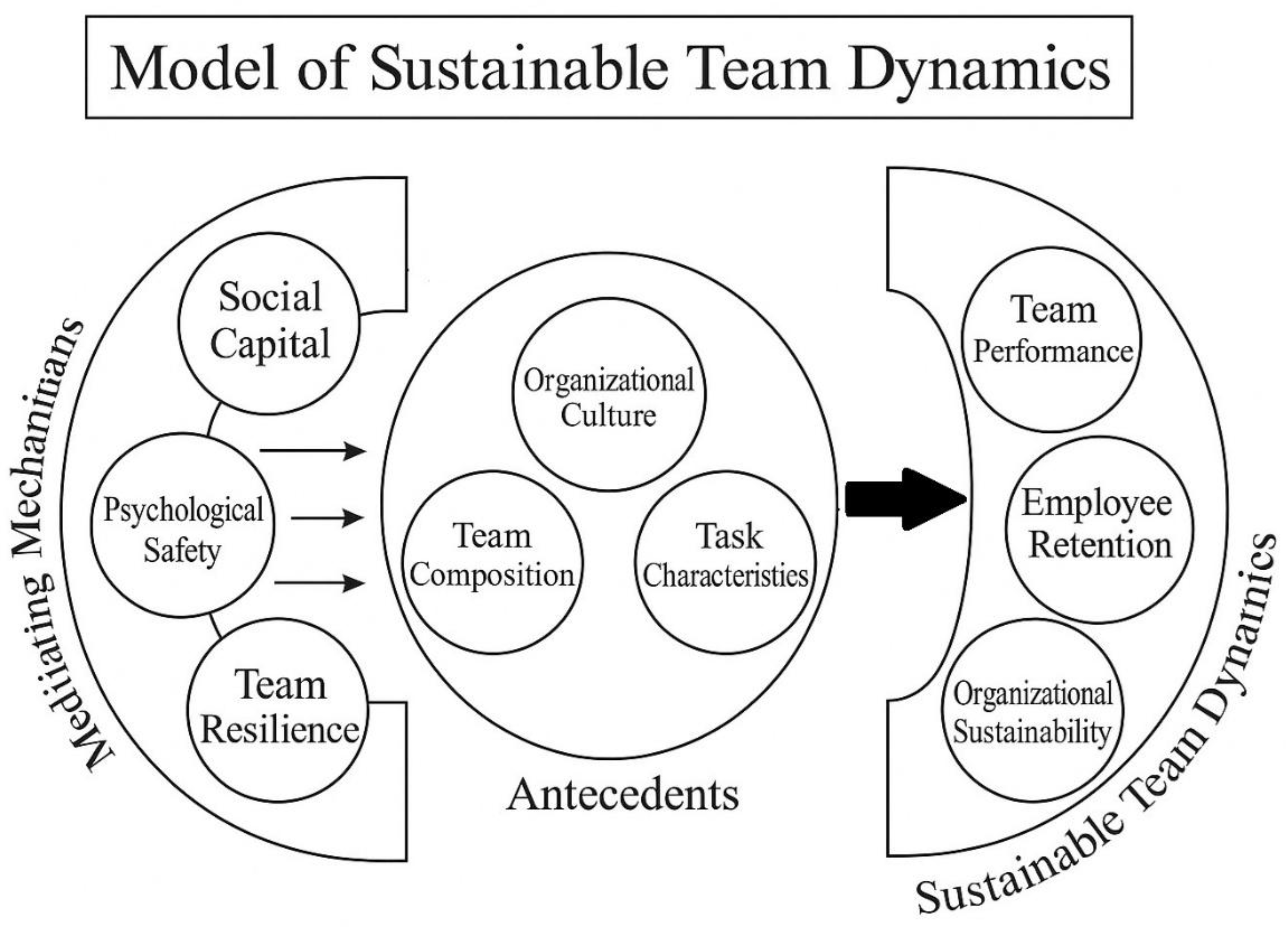

Proposed Theoretical Model of STD

- Social Capital, encompassing trust and shared norms, facilitates cooperation and information sharing (Nutakor et al., 2023).

- Psychological Safety enables open, risk-tolerant communication, which is essential for innovation.

- Team Resilience, the capacity to adapt to adversity and recover from setbacks, sustains performance and promotes long-term viability.

- High performance emerges through enhanced collaboration, problem-solving, and adaptability.

- Employee retention improves due to increased well-being, engagement, and a sense of belonging.

- Organizational sustainability benefits from a resilient, innovative, and productive workforce.

- Social Exchange Theory (SET) – emphasizing reciprocal relationships and fairness,

- Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) – focusing on resource acquisition and preservation,

- Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions – illustrating how positive experiences foster resilience and growth.

Conceptual Framework

- Effective knowledge sharing,

- Collective problem-solving, and

- Informal emotional and task-related support.

Key Interacting Components

- Team Performance: STD enhance innovation, adaptability, and consistent output over time.

- Employee Retention: Supportive, growth-oriented teams reduce burnout and turnover, fostering long-term engagement.

- Organizational Sustainability: Resilient teams contribute to human capital preservation, help meet strategic goals, and align with sustainable human resource management (HRM) principles.

Empirical Validation of Proposed Model

Research Objectives

- Testing relationships among antecedents, mediators, and outcomes.

- Confirming the mediating roles of social capital, psychological safety, and team resilience.

- Assessing the predictive power of antecedents on team performance, retention, and perceived sustainability.

Research Hypotheses

- H1: Organizational culture positively influences social capital.

- H2: Team composition diversity positively influences psychological safety.

- H3: Task interdependence positively influences team resilience.

- H4: Social capital positively affects psychological safety and resilience.

- H5: Psychological safety and resilience mediate the relationship between antecedents and outcomes.

- H6: Higher levels of social capital, psychological safety, and resilience predict enhanced team performance, lower turnover intention, and greater perceived team sustainability.

Constructs and Measures

Methodology

Research Design

Instrument Development

- Q1–Q3: Organizational Culture

- Q4–Q6: Team Composition

- Q7–Q9: Task Characteristics

- Q10–Q12: Social Capital

- Q13–Q15: Psychological Safety

- Q16–Q18: Team Resilience

- Q19–Q21: Team Performance

- Q22–Q24: Retention & Sustainability

Sample Design

- Population: Cross-functional teams (e.g., Operations, HR, MM, Marketing, R&D, CSR, L&D, Management) across sectors (corporate, nonprofit, academic).

- Sampling: Stratified purposive sampling based on sector and function.

- Sample Size: ~450 responses. This value was confirmed through AI tools to be sufficient for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and exceeding the minimum requirement based on G*Power and parameter estimation norms.

Data Analysis Plan

- Data Preparation: Reverse-coded negative items.

- Reliability & Validity: Cronbach’s Alpha for each construct and for entire questionnaire > 0.70.

- Hypothesis Testing:

- o Pearson correlations among constructs

- o Multiple regression analysis

Data Collection and Statistical Processing

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Interpretation. Can be summarized as:

- The mean scores (≈4.00) reflect consistently favorable perceptions across all constructs.

- Low standard deviations in outcome variables (Team Performance and Retention and Sustainability) suggest high agreement and low dispersion. Predictors show moderate variability (SD ~0.4).

Correlation Statistics

Regression Analysis

Interpretation Summary

- Organizational Culture positively shapes team dynamics by fostering a supportive, values-based environment.

- Psychological Safety enhances both innovation and retention by enabling open dialogue and reducing fear of failure.

- Social Capital, through trust and shared norms, bolsters collaboration and resilience.

- Team Resilience contributes not only to adaptive functioning but also to consistent outcomes over time.

Discussion

- For enhancing performance, efforts should prioritize skillful team composition, resilient mindsets, and psychological safety that nurture innovation.

- For promoting retention, attention to task design, supportive culture, and interpersonal trust becomes essential.

- Focus on strengthening Organizational Culture and Psychological Safety to enhance both performance and retention.

- Invest in team resilience training programs to support sustained outcomes as it’s a cross-cutting driver.

- Evaluate task designs to improve employee retention.

- Refine team composition strategies (Adjust team structures) to boost immediate team performance gains.

Conclusions and Implications

Theoretical Contributions

- The study advances the conceptualization of team sustainability by integrating temporal, structural, and psychological dimensions into a unified framework.

- It empirically demonstrates that sustainable team outcomes are not merely a function of performance but are significantly shaped by relational dynamics (trust, psychological safety, shared norms) and adaptive capacities (resilience, learning).

- The identification of distinct predictors for team performance and retention and sustainability adds granularity to the literature on team effectiveness and sustainability.

Practical Implications

- Cultivating a learning-oriented and inclusive organizational culture emerges as foundational for fostering both high performance and team retention.

- Investment in psychological safety and social capital development – through leadership training, team coaching, and open communication systems – is likely to yield sustainable returns in team functioning.

- Tailoring team composition strategically and designing meaningful, interdependent tasks can enhance performance and engagement.

- Building team resilience should be an explicit developmental priority, especially in volatile and complex operational environments.

Limitations and Future Research

- The cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Longitudinal studies could better capture the evolution of sustainable dynamics over time.

- Sectoral and cultural variations were not explored in depth; future studies should examine how industry context, cultural values and team lifecycle stage affect sustainability constructs. This would also need geographic extension of survey population.

- Future research could also:

- Refine the theoretical model through multilevel or longitudinal modeling, examining how sustainable dynamics unfold across time and organizational layers.

- Investigate interventions (e.g., resilience training, inclusion programs) that actively enhance the identified mediators and outcomes.

- Explore team sustainability in remote, hybrid, or AI-augmented team contexts, where dynamics may differ considerably.

References

- Ahmad, A., et al. (2023). Psychological transactions, reciprocity, exchange relationships, and the impact of various factors on this complex process. Scopus.

- Ahmad, R., Nawaz, M. R., Ishaq, R., Khan, H. R. & Ashraf, H. A. (2023). Social exchange theory: Systematic review and future directions.Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1015921. [CrossRef]

- Akaki, M., Ioki, M., Mitomi, K. & Maeno, T. (2022). Best Practices of Team-Building Activities in a Project-Based Learning Class ‘Design Project’ in a Japanese Graduate School. Proceedings of the Design Society, 2, 2263-2272. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L. M.& Pearson, C. M. (1999).Tit for tat?Thespiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452-471. [CrossRef]

- AusatAlmaududi, A.M., Risdwiyanto, A., Arfah, M. & Jemadi, J. (2023).Conflict Management Strategies in Work Teams in the Creative Industry. Kendali: Economics and Social Humanities. [CrossRef]

- Avery, G. C. (2005). Sustainable leadership: Honeybee and locust approaches. Taylor & Francis. ISBN: 9780203723944.

- Baker, J.P. &Hoidn, S. (2023). Transformational Leadership. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K. (2022). Influence of Cultural Dimensions on Intercultural Communication Styles: Ethnicity in a Moderating Role. Journal of Communication, Language and Culture. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 197–218. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717-736.

- Bates, G., Le Gouais, A., Barnfield, A., Callway, R., Hasan, M.N., Koksal, C., Kwon, H.R., Montel, L., Peake-Jones, S., White, J., Bondy, K. & Ayres, S. (2023). Balancing Autonomy and Collaboration in Large-Scale and Disciplinary Diverse Teams for Successful Qualitative Research.International Journal of Qualitative Methods. [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M., Guenther, C., Kritikos, A.S. & Thurik, R. (2021). Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics, 58, 593 - 609. [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. T. (2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 595–615. [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, D., Carlini, N., Goodfellow, I.J., Papernot, N., Oliver, A. & Raffel, C. (2019). MixMatch: A Holistic Approach to Semi-Supervised Learning. ArXiv, abs/1905.02249. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:146808485.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life.Routledge. ISBN: 9781138523197.

- Bonaconsa, C., Mbamalu, O.N., Mendelson, M., Boutall, A., Warden, C., Rayamajhi, S., Pennel, T., Hampton, M.I., Joubert, I.A., Tarrant, C., Holmes, A.H. & Charani, E. (2021). Visual mapping of team dynamics and communication patterns on surgical ward rounds: an ethnographic study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 30, 812 - 824. [CrossRef]

- Bouwmans, M., Runhaar, P., Wesselink, R. & Mulder, M. (2021). Team-Oriented HR Practices and Team Performance--Model. PsycTESTS Dataset. [CrossRef]

- Burack, O.R., Mak, W., Howard, M., Isaacs, T. & Reinhardt, J. (2023).The Importance of Adequate Resources and Equipment to Staff Engagement in a Healthcare System. Innovation in Aging, 7, 1136 - 1136. [CrossRef]

- Bush, S. (2023). Leading Teams 2: Stages of Group Development.

- Camiré, M., Newman, T.J., Bean, C. & Strachan, L. (2021).Reimagining positive youth development and life skills in sport through a social justice lens. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34, 1058 - 1076. [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, K. J., Logan, J. M., Zajac, S. A. & Holladay, C. L. (2021). Core conditions of team effectiveness: Development of a survey measuring Hackman’s framework. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(6), 928-936.

- Clauss, T., Kraus, S. & Jones, P.A. (2022). Sustainability in family business: Mechanisms, technologies and business models for achieving economic prosperity, environmental quality and social equity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A meta-analysis of construct validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386.

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D.& Morrison, R. (2018). Social exchange in the workplace: The past, the present, and the future. In The Cambridge Handbook of Workplace Affect (pp. 167-184).Cambridge University Press.

- Cropanzano, R. & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874-900.

- Cunningham, C.A., Crick, H.Q., Morecroft, M.D., Thomas, C.D. & Beale, C.M. (2023).Reconciling diverse viewpoints within systematic conservation planning. People and Nature. [CrossRef]

- Dimas, I.D., Torres, P., Rebelo, T. & Lourenço, P.R. (2023). Paths to Team Success: A Configurational Analysis of Team Effectiveness. Human Performance, 36, 155 - 179. [CrossRef]

- Dincă, M., Luştrea, A., Craşovan, M., Onițiu, A. & Berge, T. (2023).Students’ Perspectives on Team Dynamics in Project-Based Virtual Learning. SAGE Open, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ding, B., Ferràs Hernández, X. & AgellJané, N. (2023). Combining lean and agile manufacturing competitive advantages through Industry 4.0 technologies: an integrative approach.Production Planning & Control, 34(5), 442–458. [CrossRef]

- Drexler, A. B., Sibbet, D. & Forrester, R. H. (2008).The Drexler/Sibbet team performance model. Grove Consultants International.

- Du, Y., Chen, J., Zhao, C., Liu, C., Liao, F. & Chan, C. (2022). Comfortable and energy-efficient speed control of autonomous vehicles on rough pavements using deep reinforcement learning. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T. & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130-141.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2666999.

- Edmondson, A. & Bransby, D. P. (2022). Psychological Safety Comes of Age: Observed Themes in an Established Literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Egozi-Farkash, H., Lahad, M., Hobfoll, S. E., Leykin, D. & Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2022).Conservation of resources, psychological distress, and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Public Health, 67, Article 1604567. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1994). Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. California Management Review, 36, 90-100. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone.

- Elms, A. K., Gill, H. & González-Morales, M. (2022). Confidence Is Key: Collective Efficacy, Team Processes, and Team Effectiveness. Small Group Research, 54, 191-218. [CrossRef]

- Elyousfi, F., Anand, A. & Dalmasso, A. (2021). Impact of e-leadership and team dynamics on virtual team performance in a public organization. International Journal of Public Sector Management. [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: The environmental consciousness of investors. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 758-779.

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T. & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15, 20. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Gersick, C. J. G. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1), 9-41.

- Hackman, J. R. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Harvard Business School Press.

- Hagen, T.M. (2012). Maximizing team performance: key actions will help you improve operations. EMS world, 41 11, 38.

- Hasan, M. & Hassan, A. (2021).The Impact of Team Management on the Organizational Performance in Bahrain Government Sector. International Journal of Business Ethics and Governance. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Hindricks, G., Potpara, T.S., Dagres, N., Vanputte, B.P. & Watkins, C.L. (2020). 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European heart journal. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [CrossRef]

- Hornor, M.S. (2022). Diffusion of Innovation Theory. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Research Design. [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I., Chirico, A. (2023). The cultural dimension as a key value driver of the sustainable development at a strategic level: an integrated five-dimensional approach. Environ Dev Sustain, 25, 7011–7028. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.C. & Dillahunt, T.R. (2021). More than Shared Ethnicity: Shared Identity’s Role in Transnational Newcomers’ Trust in Local Consumer-to-Consumer E-commerce. Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. (2018). The impact of talent team optimization and innovative human resource management on organizational performance with the mediating effect of resilience capability. Sustainability, 10(12), 4644.

- Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M. & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual review of psychology, Vol. 56, 517-543.

- Iqbal, Q. & Piwowar-Sulej, K. (2023). Sustainable leadership and heterogeneous knowledge sharing: the model for frugal innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H., & Yan, J. (2020). How Team Structure Can Enhance Performance: Team Longevity’s Moderating Effect and Team Coordination’s Mediating Effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. (2021). Leading effective teams.BMJ Leader, 6, 6 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. (2019). The Tuckman’s Model Implementation, Effect, and Analysis&the New Development of Jones LSI Model on a Small Group. Management Practice eJournal. [CrossRef]

- Katzenbach,J & Smith, D (1992), The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization, Harvard Business Press, ISBN 9781422148150.

- ay, A.A .& Skarlicki, D.P. (2020).Cultivating a conflict-positive workplace: How mindfulness facilitates constructive conflict management. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 159, 8-20. [CrossRef]

- Krause, D. R., Scannell, T. V. & Pohlen, T. L. (2009). Reverse logistics: A review and future directions. Journal of Business Logistics, 30(2), 271-306.

- Lacerenza, C.N., Marlow, S.L., Tannenbaum, S.I. & Salas, E. (2018). Team Development Interventions: Evidence-Based Approaches for Improving Teamwork. American Psychologist, 73, 517–531. [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K., Huang, X., Walter, F. & Chan, S.C. (2016).Coworkers’ Relationship Quality and Interpersonal Emotions in Team-Member Dyads in China: the Moderating Role of Cooperative Team Goals. Management and Organization Review, 12, 687 - 716. [CrossRef]

- Lam, P. T. I. & Lai, K. H. (2015). Environmental management and corporate performance: The mediating role of green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 100, 237-247.

- Leana, C. R. & Barry, B. (2000). What’s in it for me? Workplace power and employee autonomy. Academy of Management Review, 25(2), 343-352.

- Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. John Wiley &Sons. ISBN 9788126522743.

- Levi, D. (2020). Group Dynamics for Teams. SAGE Publications. ISBN: 9781483378343.

- Lewis, D. (2022). Contesting liberal peace: Russia’s emerging model of conflict management. InternationalAffairs. [CrossRef]

- Li, L. (2022). Reskilling and Upskilling the Future-ready Workforce for Industry 4.0 and Beyond. Information Systems Frontiers, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Liu, Q., Stone, P., Garg, A., Zhu, Y. & Anandkumar, A. (2021). Coach-Player Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Team Composition. ArXiv, abs/2105.08692.

- Liu, H., Xing, L., Wang, C. & Zhang, H. (2022). Sustainability assessment of coupled human and natural systems from the perspective of the supply and demand of ecosystem services. Frontiers in Earth Science. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Huang, Y., Kim, J. & Na, S. (2023). How Ethical Leadership Cultivates Innovative Work Behaviors in Employees? Psychological Safety, Work Engagement and Openness to Experience. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Lin, P. & Chen, A.N. (2017). An empirical study of behavioral intention model: Using learning and teaching styles as individual differences. Journal of Discrete Mathematical Sciences and Cryptography, 20, 19 - 41. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M., Irshad, M., Khan, I.U. & Saeed, I. (2023). The Impact of Team Mindfulness on Project Team Performance: The Moderating Role of Effective Team Leadership. Project Management Journal, 54, 162 - 178. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J. E., Maynard, M. T., Rapp, T. & Gilson, L. L. (2008). Team effectiveness 1997-2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. Journal of Management, 34(1), 99-134.

- Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kukenberger, M. R., Donsbach, J. S. & Alliger, G. M. (2019). Team effectiveness 1997–2017: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 47-81.

- Maurer, H., Whitman, R.G. & Wright, N. (2023). The EU and the invasion of Ukraine: a collective responsibility to act? International Affairs. [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G. & Schaufeli, W.B. (2022). The impact of engaging leadership on employee engagement and team effectiveness: A longitudinal, multi-level study on the mediating role of personal- and team resources. PLoS ONE, 17. [CrossRef]

- McMullin, M. & Dilger, B. (2021). Constructive Distributed Work: An Integrated Approach to Sustainable Collaboration and Research for Distributed Teams. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35, 469 - 495. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, A. (2022). Effective Team Management Strategies in Global Organizations. Universal Research Reports. [CrossRef]

- Meisenbach, R.J. & Brandhorst, J.K. (2018).Organizational Culture. The International Encyclopaedia of Strategic Communication. [CrossRef]

- Melia, S. (2016).Sustainable travel and team dynamics among mobile health professionals. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 10, 131 - 138. [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M., Chau, K., Tu, Y., Nguyen, K., Barry, M. & Reddy, K. D. (2022).Impact of corporate sustainable practices, government initiative, technology usage, and organizational culture on automobile industry sustainable performance. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 83907-83920. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.C. & Agarwal, R.K. (2011).A Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations. International Journal of Transformations in Business Management, 1(1).

- Nguyen, N. (2021). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. The Learning Organization. [CrossRef]

- Nutakor, J.A., Zhou, L., Larnyo, E., Addai-Danso, S. & Tripura, D. (2023). Socioeconomic Status and Quality of Life: An Assessment of the Mediating Effect of Social Capital. Healthcare, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ones, D. S. & Dilchert, S. (2012). Employee green behavior.In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. P. M. Wilderom, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), The handbook of organizational culture and climate, 2nd ed., 427–462. Sage Publications.

- Orekoya, I.O. (2023). Inclusive leadership and team climate: the role of team power distance and trust in leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. [CrossRef]

- Raff, L.A., Reilly, K., Ratner, S.P., Moore, C.R. & Raff, E. (2022). Building High-Performance Team Dynamics for Rapid Response Events in a US Tertiary Hospital: A Quality Improvement Model for Sustainable Process Change. American Journal of Medical Quality. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L., Cui, L., Chen, C., Dong, X., Wu, Z., Wang, Y. & Yang, Q. (2019).The implicit beliefs and implicit behavioral tendencies towards smoking-related cues among Chinese male smokers and non-smokers. BMC Public Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L. & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698.

- Riggle, E. D., Edmondson, D. R. & Hansen, J. D. (2009). Perceived organizational support and pay satisfaction among volunteers: Examining social exchange and equity theory predictions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(4), 290-308.

- Robertson, J. L. (2021). The relationship between pro-environmental attitudes, behaviors, identity, team cohesion, and team performance on a sustainability-related project.

- Rolin, K.H., Koskinen, I., Kuorikoski, J. & Reijula, S. (2023). Social and cognitive diversity in science: introduction. Synthese, 202, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, I. M., Plovnick, M. S. & Fry, R. E. (1978).Task-oriented team development. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070541973.

- Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons.

- Sessitsch, A., Wakelin, S., Schloter, M., Maguin, E., Cernava, T., Champomier-Vergès, M.&Kostić, T. (2023). Microbiome Interconnectedness throughout Environments with Major Consequences for Healthy People and a Healthy Planet. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 87. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F. P. da, Mosquera, P. & Soares, M. (2022). Factors influencing knowledge sharing among IT geographically dispersed teams. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. (2022). Brundtland Commission: A Comparative Analysis of the Energy Gap between India and China. Jindal Journal of Public Policy. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. K. & Tushman, M. L. (2005). Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organization Science, 16(5), 522-536.

- Suryasa, I. W., Rodríguez-Gámez, M. & Koldoris, T. (2022). Post-pandemic health and its sustainability. International Journal of Health Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Sypniewska, B., Baran, M. & Kłos, M. (2023). Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management – based on the study of Polish employees. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R., Walas, B. & Kruczek, Z. (2022).The Willingness of Tourism-Friendly Cities’ Representatives to Share Innovative Solutions in the Form of Open Innovations. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. (2023). A Review of Technology Acceptance and Adoption Models and Theories. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research. [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, C. & Pellati, E. (2023).Social bonds and the “social premium”. Journal of Economics and Finance, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Tuckman, B. W. & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2(4),419-427.

- Tudor, G. J. & Trumble, W. W. (1996). Formative and summative evaluation: Different goals require different methods. Journal of Educational Measurement, 33(1), 1-5.

- Wang, Z., Pan, W., Li, H., Wang, X. & Zuo, Q. (2022). Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches for Conflict Resolution in Air Traffic Control. Aerospace. [CrossRef]

- Waters, L., Strauss, G., Somech, A., Haslam, N. & Dussert, D. (2020). Does team psychological capital predict team outcomes at work? International Journal of Wellbeing. [CrossRef]

- Wheelan, S. A. (1994). Group processes: A developmental perspective.Allyn and Bacon.

- Wijaya, N. H. S. (2020). The Effect of Team Social Exchange Perspective on Employee Job Satisfaction. The 2020 International Conference on E-Business Intelligence (ICEBI 2020), 177-181.

- Woodard, L., Amspoker, A.B., Hundt, N.E., Gordon, H.S., Hertz, B., Odom, E., Utech, A.E., Razjouyan, J., Rajan, S.S., Kamdar, N.P., Lindo, J., Kiefer, L., Mehta, P. & Naik, A.D. (2022). Comparison of Collaborative Goal Setting With Enhanced Education for Managing Diabetes-Associated Distress and HemoglobinA1c Levels. JAMA Network Open, 5. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Liu, C. & Huang, Y. (2022).The exploration of continuous learning intention in STEAM education through attitude, motivation, and cognitive load. International Journal of STEM Education, 9, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. (2022). Ethically Responsible and Trustworthy Autonomous Systems for 6G. IEEE Network, 36, 126-133. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, D.A. (2021). Our Shared Purpose: Leadership. AORN journal, 113 3, 223-224. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C., Wang, J., Perc, M. & Wang, Z. (2023).Reputation and reciprocity. Physics of life reviews, 46, 8-45. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., She, S., Gao, P. & Sun, Y. (2023). Role of green finance in resource efficiency and green economic growth. ResourcesPolicy. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. & Liu, X. (2022). The effect of activated resource-based fault lines on team creativity: mediating role of open communication and moderating role of humble leadership. Current Psychology, 42, 13411 - 13423. [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, A. (2023). Knowledge sharing in organization: A systematic review. Cogent Business & Management, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y., Li, Q., Huang, T. & Yu, Y. (2022).Strategic Information Sharing of Online Platforms as Resellers or Marketplaces.Mark. Sci., 42, 659-678. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. & Bartol, K.M. (2010). Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 107-128. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Pickett, S.T. & McPhearson, T. (2021). Conceptual frameworks facilitate integration for transdisciplinary urban science. npj Urban Sustainability, 1, 1-11. [CrossRef]

| Construct | Type | Example Indicators |

| Organizational Culture | Antecedent | Trust, learning orientation, supportiveness |

| Team Composition | Antecedent | Diversity in skills, values |

| Task Characteristics | Antecedent | Complexity, interdependence |

| Social Capital | Mediator | Trust, shared norms, mutual help |

| Psychological Safety | Mediator | Safe to express ideas, tolerance for mistakes |

| Team Resilience | Mediator | Recovery from setbacks, adaptability |

| Team Performance | Outcome | Innovation, productivity, responsiveness |

| Retention Intention | Outcome | Commitment to remain |

| Perceived Sustainability | Outcome | Long-term viability and cohesion |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min | Max | Range |

| Organizational Culture | 3.999 | 0.405 | -0.018 | -1.001 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Team Composition | 4.001 | 0.403 | -0.065 | -0.982 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Task Characteristics | 3.999 | 0.407 | -0.011 | -0.984 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Social Capital | 4.000 | 0.401 | 0.023 | -1.026 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Psychological Safety | 3.999 | 0.413 | -0.024 | -0.976 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Team Resilience | 4.000 | 0.415 | -0.063 | -1.044 | 3.33 | 4.67 | 1.34 |

| Team Performance | 4.538 | 0.163 | -0.469 | -1.788 | 4.33 | 4.67 | 0.34 |

| Retention Sustainability | 4.537 | 0.163 | -0.450 | -1.806 | 4.33 | 4.67 | 0.34 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Org Culture 1 | 1.000 | |||||||

| Team Composition 2 | 0.740 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Task Characteristics 3 | 0.750 | 0.724 | 1.000 | |||||

| Social Capital 4 | 0.716 | 0.741 | 0.722 | 1.000 | ||||

| Psych Safety 5 | 0.733 | 0.754 | 0.746 | 0.754 | 1.000 | |||

| Team Resilience 6 | 0.721 | 0.727 | 0.752 | 0.721 | 0.763 | 1.000 | ||

| Team Performance 7 | 0.667 | 0.657 | 0.612 | 0.649 | 0.665 | 0.663 | 1.000 | |

| Retention Sustainability 8 | 0.665 | 0.656 | 0.674 | 0.659 | 0.689 | 0.673 | 0.643 | 1.000 |

| Predictor | β Coeff. | Std. Err. | t-Stat. | p-Value | Significance |

| Intercept | 3.205 | 0.058 | 53.31 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Org Culture | 0.088 | 0.023 | 3.89 | 0.0001 | Significant, Strong positive influence |

| Team Composition | 0.061 | 0.023 | 2.63 | 0.009 | Significant, Moderate influence |

| Task Characteristics | -0.010 | 0.023 | -0.44 | 0.662 | Not Significant |

| Social Capital | 0.058 | 0.023 | 2.55 | 0.011 | Significant contributor |

| Psychological Safety | 0.061 | 0.024 | 2.56 | 0.011 | Significant Statistically relevant |

| Team Resilience | 0.076 | 0.022 | 3.39 | 0.001 | Significant, Positive, solid effect |

| Predictor | β Coeff. | Std. Err. | t-Stat. | p-Value | Significance |

| Intercept | 3.168 | 0.057 | 55.94 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Org Culture | 0.058 | 0.022 | 2.62 | 0.009 | Significant Positively related |

| Team Composition | 0.038 | 0.023 | 1.66 | 0.097 | Marginally significant (p > 0.07) |

| Task Characteristics | 0.062 | 0.023 | 2.76 | 0.006 | Significant in this model |

| Social Capital | 0.050 | 0.022 | 2.25 | 0.025 | Meaningful contributor |

| Psychological Safety | 0.075 | 0.023 | 3.25 | 0.001 | Strong predictor |

| Team Resilience | 0.059 | 0.022 | 2.69 | 0.007 | Important role |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).