1. Introduction

Plastic products have been widely used in human production and daily life because of their light weight, waterproof, insulation, durability and corrosion resistance. According to statistics, more than 350 million tons of plastic are consumed globally every year. However, due to the difficulty in decomposing plastics in the natural environment, waste plastics continue to accumulate in the environment [

1]. They can only be gradually broken into smaller particles through physical action, chemical reaction or microbial activity. Usually, particles with a diameter of less than 5 mm are defined as microplastics [

2]. In aquatic ecosystems, the presence of microplastics has an inevitable impact on microorganisms, aquatic plants and animal communities. Studies have revealed that these tiny plastic particles can enter organisms through the food chain. Although most of the microplastics can be eliminated by excretion, some of them accumulate in the gills or internal organs of fish, triggering oxidative stress and even death [

3]. Through the progressive layers of the food chain, it poses a serious threat to human health [

4].

At present, a large number of studies have simulated the process of fish intake of microplastics in a laboratory environment and explored the toxic effects of microplastics. Studies have shown that microplastic particles ingested by fish accumulate in their gills and digestive tract, and may migrate to important organs such as liver and brain. These tiny particles not only cause mechanical damage to tissues, but also cause abnormal physiological functions, metabolic disorders and significant changes in behavioral patterns in fish. Gua et al. found that it had a negative impact on the intestinal health and growth performance of juvenile large yellow croaker (

Larimichthys crocea) during 14 days of nanoplastic exposure [

5]. Digestive enzyme activity decreased, the number of potential pathogenic bacteria increased significantly, lysozyme activity decreased, growth rate decreased, and mortality increased [

6]. Polyethylene microplastics do not cause serious toxic effects in adult zebrafish (

Danio rerio), but they affect the activity of certain biochemical enzymes and persist in the intestines of juvenile zebrafish. [

7] Studies have shown that the 96h challenge test caused zebrafish to show changes in antioxidant enzyme activity [

8]. Wan et al. found that microplastics could significantly inhibit the activity of catalase (CAT) in zebrafish larvae and lead to a significant decrease in glutathione (GSH) levels [

9]. Jeong et al. found that exposure to polystyrene microplastics significantly affected the motor function of zebrafish larvae, which was manifested by decreased swimming speed and impaired motor coordination. [

10] Chen et al. found that microplastics and nanoplastics have direct and indirect toxic effects on the swimming activity of zebrafish larvae [

11].

Sebastes schlegelii (Sebastes schlegelii), also known as blackfish, is a temperate near-bottom-dwelling fish distributed in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. [

12] It is a common species in mariculture and marine ecological research because of its delicious meat and important economic value. [

13] Previous studies on Sebastes schlegelii mainly focused on the effects of temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and light [

14,

15,

16,

17]. There are few studies on the toxic effects of microplastics on Sebastes schlegelii. In this study, juvenile Sebastes schlegelii was used as the experimental object to observe and analyze the effects of microplastic pollution stress on the immune physiological indexes and behaviors of juvenile Sebastes schlegelii.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject

The test materials of Sebastes schlegelii were purchased from Dalian Tianzheng Industrial Co., Ltd. After purchase, it was placed in an indoor circulating temperature control tank for 7 days of domestication, and the water temperature was maintained at (16 ± 0.5) °C. During the domestication period, they were fed with commercial feed at 8: 00 every day. After 1 hour of feeding, siphons were used to remove residual bait and feces. Replace 1 / 3 of the water every day to ensure that the water is clean. During the whole domestication process, oxygen was continuously supplied day and night. The photoperiod was set to 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness (L ∶ D = 12 h ∶ 12 h), and the illumination time was from 8: 00 to 20: 00.

2.2. Experimental Design

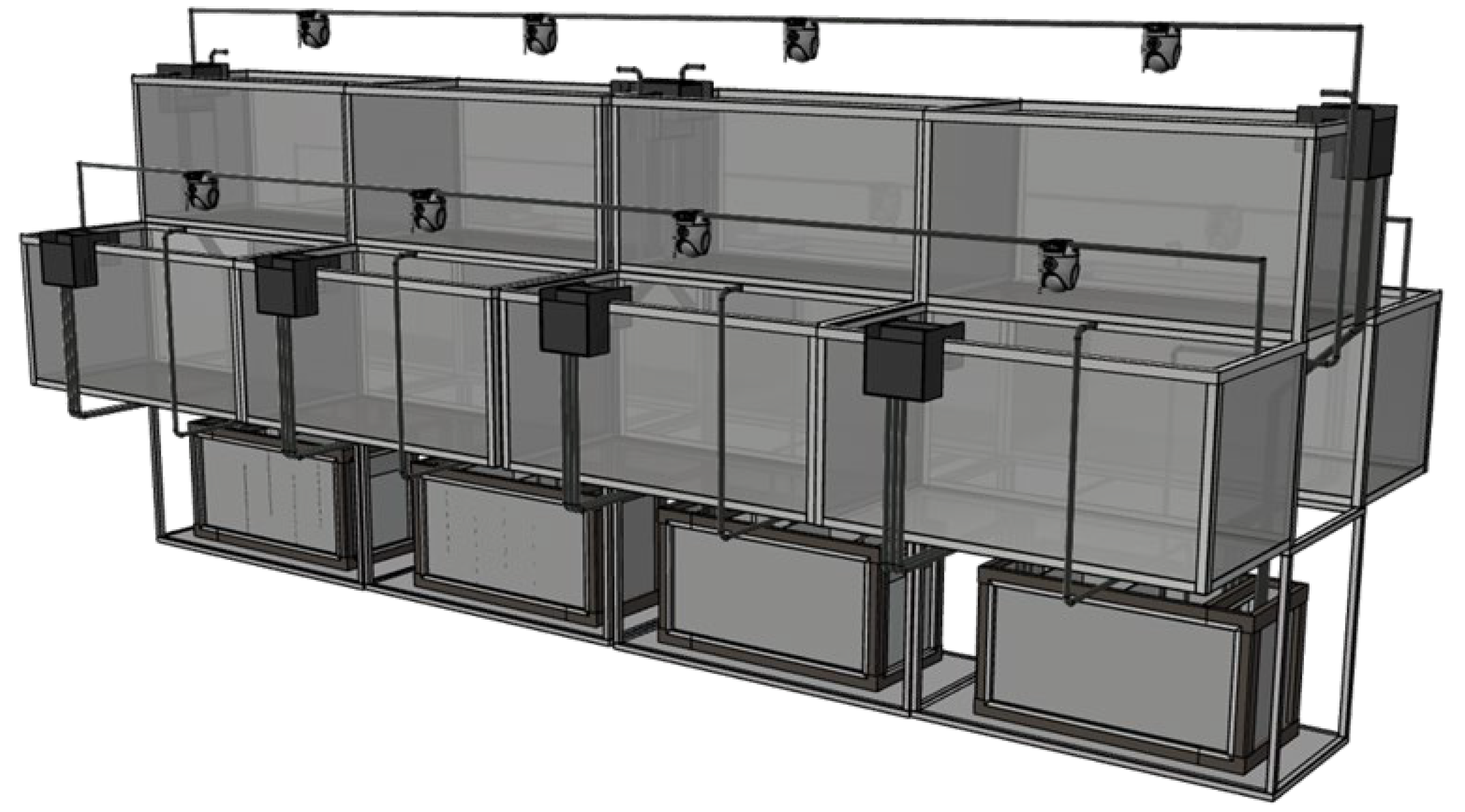

After two weeks of temporary feeding, the experiment was officially started after ensuring the stable growth and normal feeding of the experimental fish. Before the experiment, the experimental fish were fasted for 24 hours. 144 healthy fish (initial body weight 8-11g, body length 7-9cm) were selected. Exposure to control group (0 mg / L): no polystyrene microplastics were added, low concentration group (0.01 mg / L), medium concentration group (0.1 mg / L) and high concentration group (1 mg / L), polystyrene microplastics particle size was 0.5 μm. Three parallel cylinders were set up in each group, and 16 fish were placed in each cylinder. The seawater with aeration for 24 hours was used as the exposure liquid, and half of the exposure liquid was replaced every day to keep the water quality stable. Continuous aeration to prevent the aggregation of microplastic particles. The experimental device is shown in

Figure 1. The exposure period was 24 days, and the water quality was consistent with the temporary period. An infrared camera video was placed 1 m above the middle of the sink to record the behavior of the fish in real time. Swimming speed, nearest neighbor distance, and inter-individual distance in group behavior. Using EthoVisio XT 12 behavioral analysis software, the x-axis and y-axis coordinate values of the test fish were derived and calculated and analyzed. In addition, the polarity of the fish group arrangement was counted. Through the above data, the cohesion and coordination of the fish group can be analyzed. During the experiment, the fish were taken on the 6th, 12th, 18th and 24th days to measure their growth indicators and their livers were taken for physiological detection.

2.3. Determination of Growth Physiological Indexes

2.3.1. Growth Index Determination

Samples were taken on the 6th, 12th, 18th and 24th day of the exposure period, and three fish were taken in each parallel. MS-222 was used for anesthesia according to the size of the fish. The survival rate (SR), body weight (BW), body length (BL) and weight gain rate (WGR) of juvenile Sebastes schlegelii were measured and analyzed. The formula is as follows:

In the formula: W0 is the initial mass (g) of the fish, Wt is the final mass (g) of the fish, N0 and Nt are the number of fish in each group at the beginning and the end of the experiment, t is the test time (d).

2.3.2. Physiological Index Determination

The experimental fish was dissected and washed three times in a sterile physiological solution pre-cooled at 4 °C. Subsequently, the washed tissue samples were mixed with 9 times the volume of frozen PBS buffer, and the tissue homogenizer was used to grind in an ice bath environment to prepare a tissue suspension with a concentration of 10%. The mixture was then transferred into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 2500 r / min for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Finally, the supernatant liquid in the centrifuge tube was collected for biochemical index detection. The biochemical indexes involved in the experiment were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Specific detection items include: alkaline phosphatase (AKP), aspartate aminotransferase (GOT), lysozyme (LZM), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), acetylcholinesterase (ACHE), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). All kits are provided by Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, and the detection process of each index strictly follows the standard operating procedures provided by the manufacturer.

2.4. Group Behavior Parameter Calculation

Nearest neighbor distance: represents the minimum distance (cm) between one individual and all other individuals in the fish school, which is used to measure group cohesion. The calculation formula is as follows:

In formula (3): NND is the nearest neighbor distance (cm); xi and xj are the abscissa values of the ith and jth fish in the fish school at time t; yi and yj are the ordinate values of the i and j fishes in the fish school at time t.

Inter-individual distance: The average distance (cm) between all individuals in the fish group is used to evaluate the group cohesion. The calculation formula is as follows.

In formula (4):IID is the distance between individuals (cm); xi and xj are the abscissa values of the ith and jth fish in the fish school at time t; yi and yj are the ordinate values of the i and j fishes in the fish school at time t.

Group polarity: Group polarity refers to the degree of consistency of the direction of individual movement in the fish group.

In Equation (5): m represents the number of individuals consistent with the direction of the leader fish, and n represents the total number of individuals in the population; when calculating the polarity, 10 frames of images were selected every 1 min, and then the movement directions of different test fish individuals in the group were observed frame by frame.

2.5. Data Analysis

After the experimental data were preliminarily processed by Excel, SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA, α = 0.05) combined with LSD multiple comparisons were used to test the significance of differences between groups. The data were expressed as Mean ± SE, and the significance level was set to P < 0.05. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the correlation between behavioral indicators and physiological indicators of Sebastes schlegelii (P < 0.05). Drawing with Origin 2019 32b.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

Different microplastics had no effect on the survival rate of juvenile Sebastes schlegelii, no death occurred, and the survival rate was 100%.

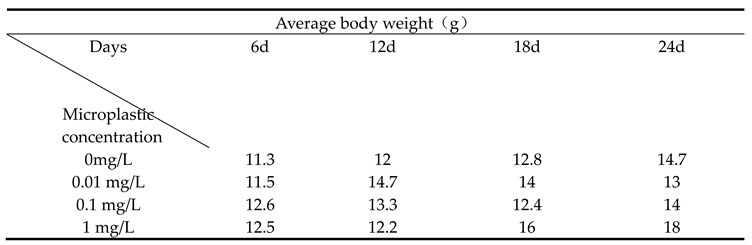

The effects of different concentrations of microplastics on the body weight of Sebastes schlegelii were as shown in

Table 1. The overall growth rate of the control group was gentle, which was in line with the growth law of juvenile fish under normal conditions. The weight change of juvenile fish exposed to 0.01 mg / L microplastics showed a unique biphasic effect of first promotion and then inhibition. In the early stage of exposure, the weight of juvenile fish was significantly higher than that of the control group, indicating that microplastics could promote growth in the short term. However, as the exposure time extended to 18 days and 24 days, the weight gain stagnated and began to decline, and finally was lower than that of the control group, indicating that long-term exposure had a negative effect on inhibiting growth. During the whole experiment, there was no statistically significant difference in body weight between the 0.1 mg / L group and the control group at any time point (P > 0.05). Although the weight gain curve fluctuates, it can be regarded as within the normal physiological fluctuation range. The 1 mg / L group was significantly lower than other groups (P< 0.05).

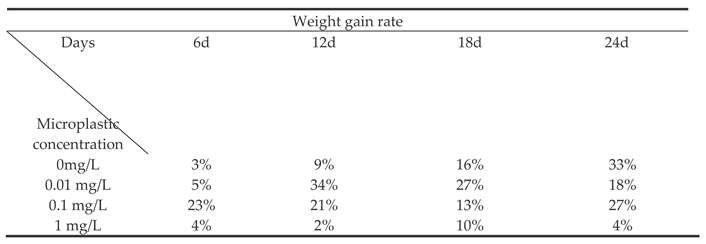

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the weight growth rate of Sebastes schlegelii. As shown in

Table 2, the WGR of the 0.01 mg / L concentration group changed most dramatically. In the middle of exposure (day 12), its WGR reached a peak, which was significantly higher than all other groups in the same period (P< 0.05), showing a strong short-term growth promotion effect. However, since then, WGR continued to decrease significantly, and was still higher than the control group on the 18th day but the advantage shrank. Finally, it was significantly lower than the control group on the 24th day (P< 0.05), indicating that early high-speed growth was not sustainable and eventually led to a decline in growth performance. 0.1 mg / L On the 6th day, the WGR was as high as 23%, which was the highest value of all groups at that time point, significantly higher than other groups. But it declined rapidly thereafter. High concentration group (1 mg / L) During the whole experiment, it showed continuous and strong growth inhibition. WGR was at a very low level at all time points and was significantly lower than that of the control group (P< 0.05). The concentration of 1 mg / L microplastics had a significant toxic effect on Sebastes schlegelii. High concentrations of microplastics may seriously affect the feeding behavior, intestinal function, nutrient absorption and energy metabolism of fish, resulting in serious inhibition of its growth. The microplastic stress at this concentration is beyond the physiological regulation range of the fish body and cannot produce any promoting effect.

3.2. Physiological Function

3.2.1. Oxidation Resistance

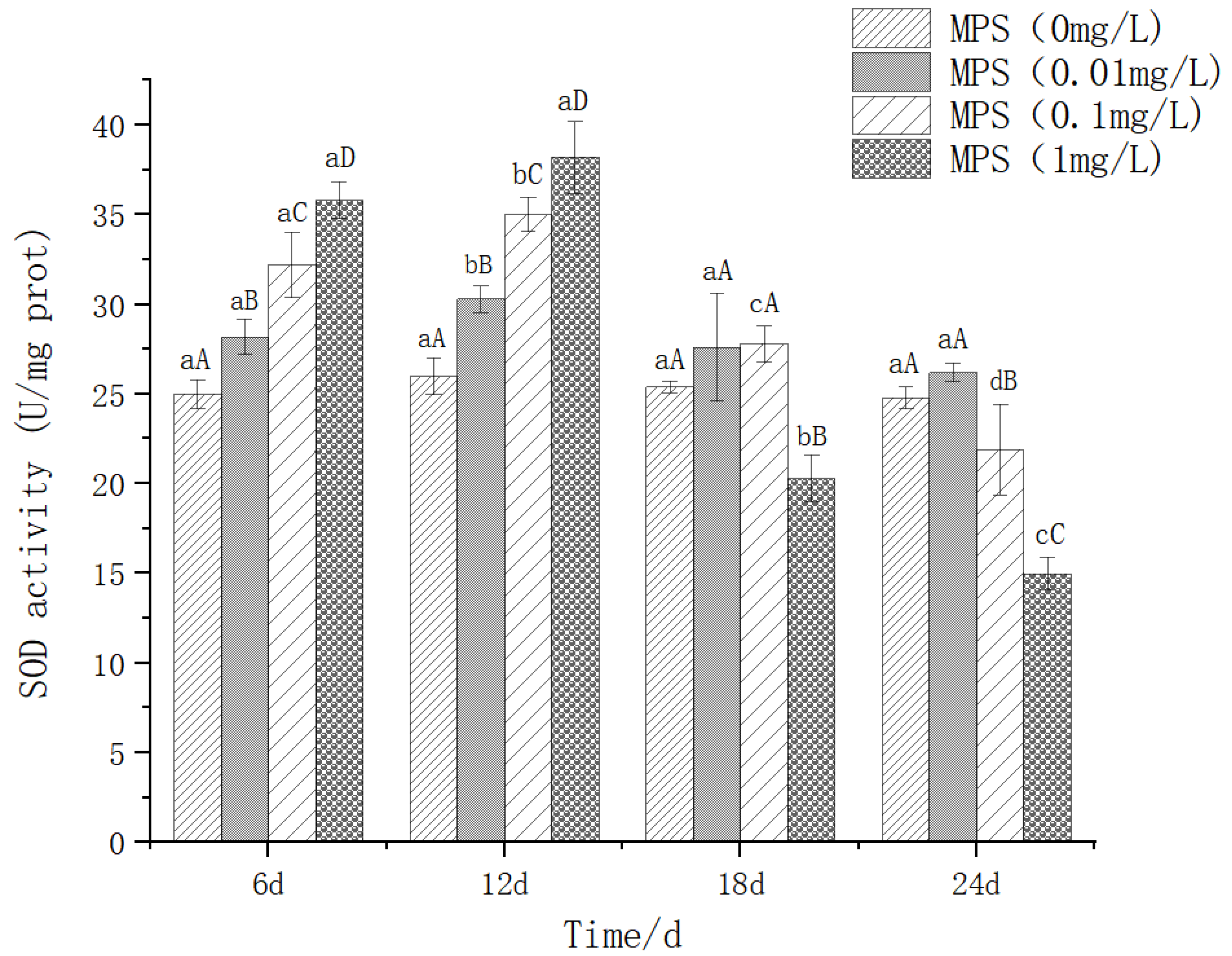

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the liver of Sebastes schlegelii. As shown in

Figure 1, after 6d and 12d of treatment with different concentrations of microplastics, there were significant differences between the concentrations (P < 0.05), and increased with the increase of concentration. At 18d, there was no significant difference among 0mg / l, 0.01mg / l and 0.1mg / l groups (P > 0.05), while 1mg / l group was significantly lower than the other three groups (P< 0.05). At 24d, there was no significant difference between 0mg / l and 0.01mg / l group (P > 0.05), 0.1mg / l group was significantly lower than the other two groups (P< 0.05), 1mg / l group was significantly lower than the other three groups (P< 0.05). In the 0.01mg / l treatment group, it was significantly higher on the 12th day than on the 6th, 18th and 24th day (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between 6d, 18d and 24d (P> 0.05). The content of SOD increased first and then decreased slowly to a gentle trend. The 0.1mg / l treatment group was significantly higher than other days at 12d, and significantly lower than 6d and 12d at 18d and 24d. The content of SOD increased first and then decreased continuously. The trend of 1mg / l and 0.1mg / l increased first and then decreased sharply.

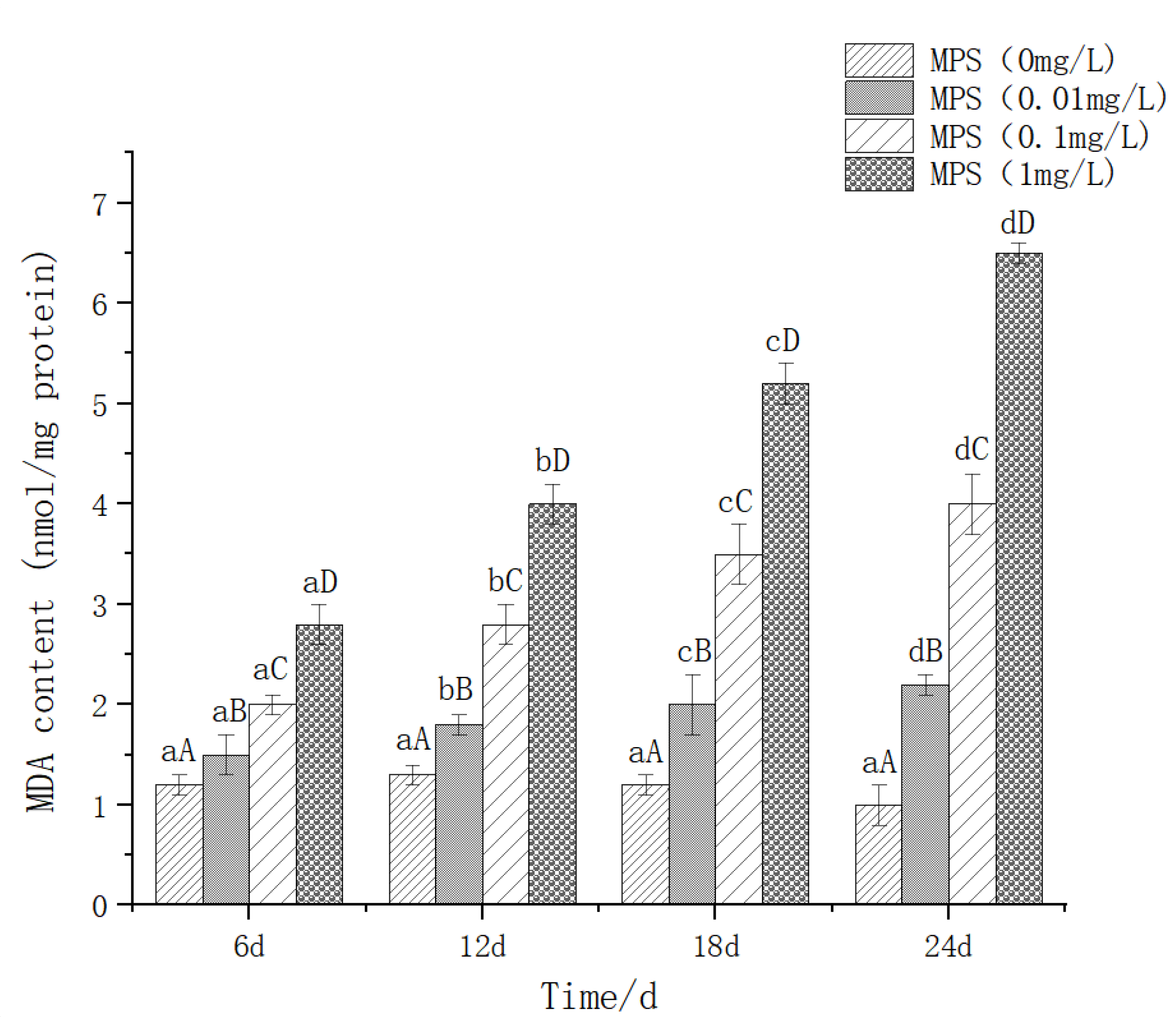

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the liver of Sebastes schlegelii. As shown in

Figure 2, the content of MDA increased significantly with the increase of concentration at 6d, 12d, 18d and 24d (P< 0.05). 0.01mg / l, 0.1mg / l, 1mg / l treatment group, the same concentration, each time the difference was significant (P< 0.05), showed a gradual upward trend.

3.2.2. Non-Specific Immunity

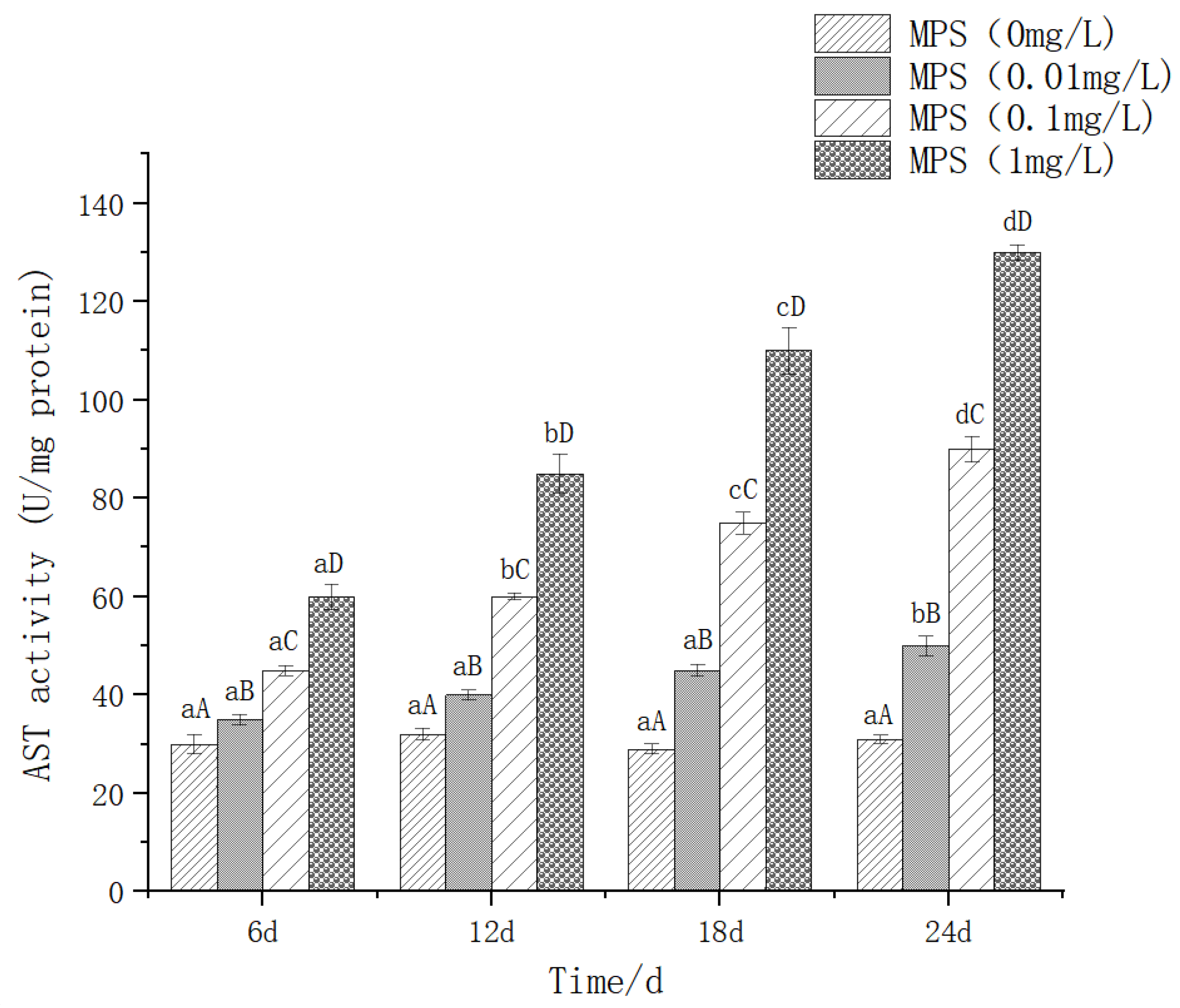

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) is shown in

Figure 3.At the same time of 6d, 12d, 18d and 24d, the difference between different concentrations was significant. The higher the concentration, the higher the AST content. There was no significant difference in the 0.01mg / l treatment group at 6d, 12d, and 18d (

P> 0.05), and it increased significantly at 24d (

P< 0.05).

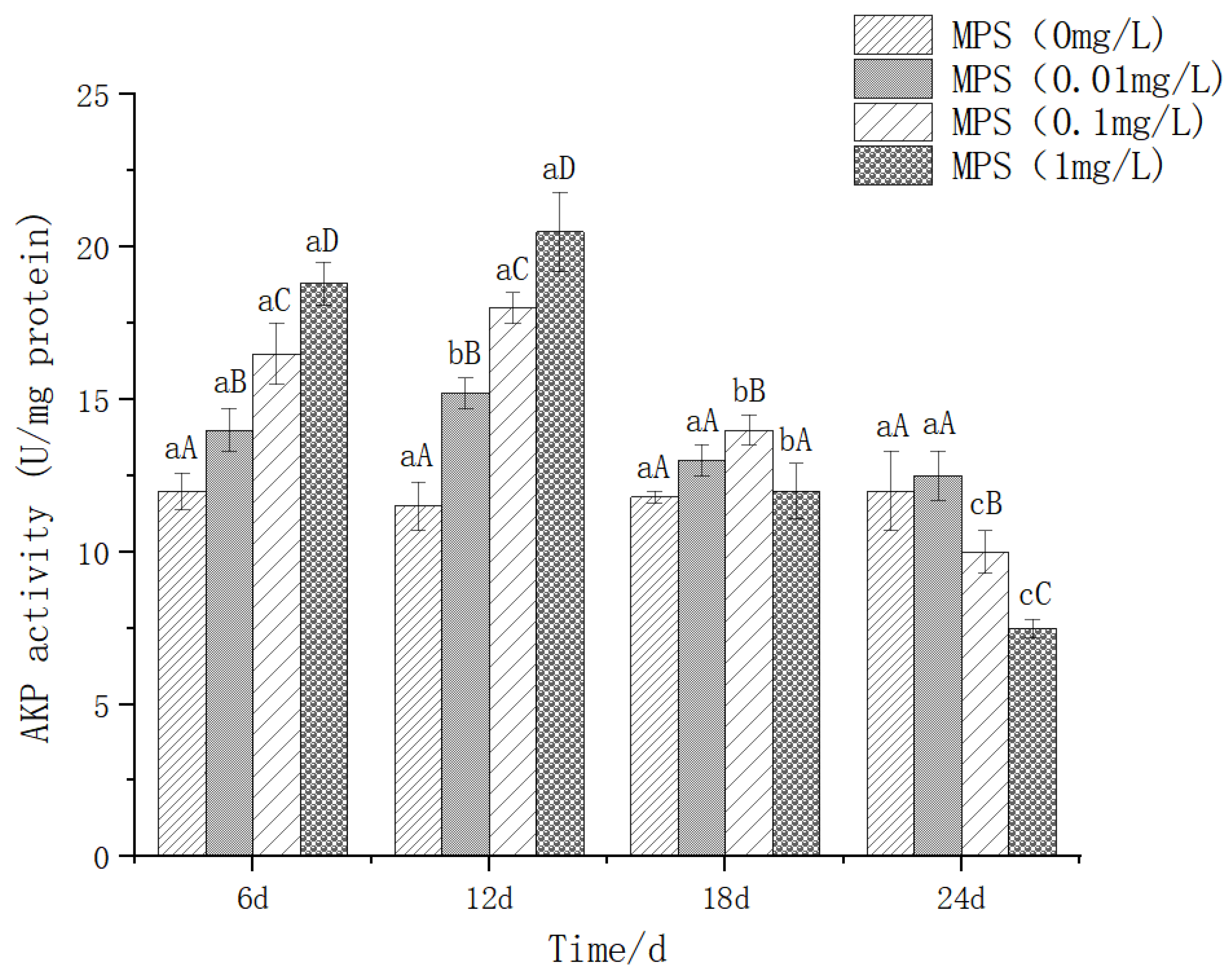

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on alkaline phosphatase (AKP) content as shown in

Figure 4, at the same time of 6d and 12d, the higher the concentration, the higher the AKP content, and the difference between different concentrations was significant (

P< 0.05). On the 18th day, the 1mg / l treatment group was significantly higher than the other three groups (

P< 0.05). There was no significant difference between the other three groups (

P > 0.05). On the 24th day, the 0.1mg / l and 1mg / l groups were significantly lower than the 0mg / l and 0.01mg / l groups. 0.1 mg / l group on the 12th day was significantly higher than that on the 6th, 18th and 24th day (

P< 0. 05). There was no significant difference between the three days (

P> 0.05). The 18d and 24d were significantly lower than the 6d and 12d (

P< 0.05), showing a trend of increasing first and then decreasing significantly.

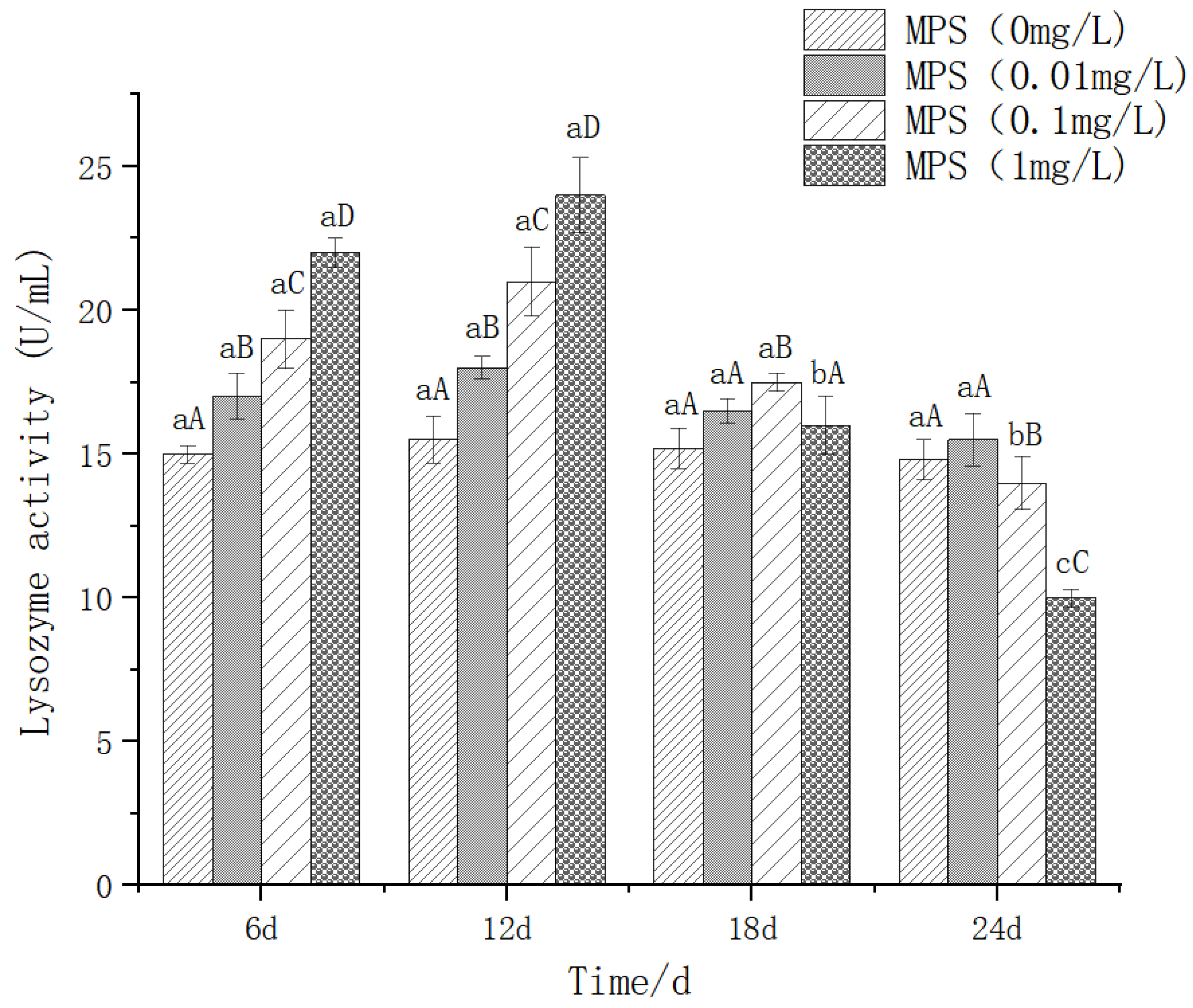

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of lysozyme (LZM) was shown in

Figure 5. On the 6th and 12th days, there were significant differences between different concentrations (

P < 0.05). The higher the concentration, the higher the activity of LZM. On the 18th day, 0.1mg / l was significantly higher than the other three groups (

P< 0.05). On the 24th day, there was no significant difference between 0mg / l and 0.01mg / l (

P> 0.05), and the 0.1mg / l and 1mg / l groups were significantly lower than the 0mg / l and 0.01mg / l groups. There was no significant difference between 6d and 12d in 1mg / l group, and 18d and 24d were significantly lower than 6d and 12d. It shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing sharply.

3.2.3. Neurotoxic Markers

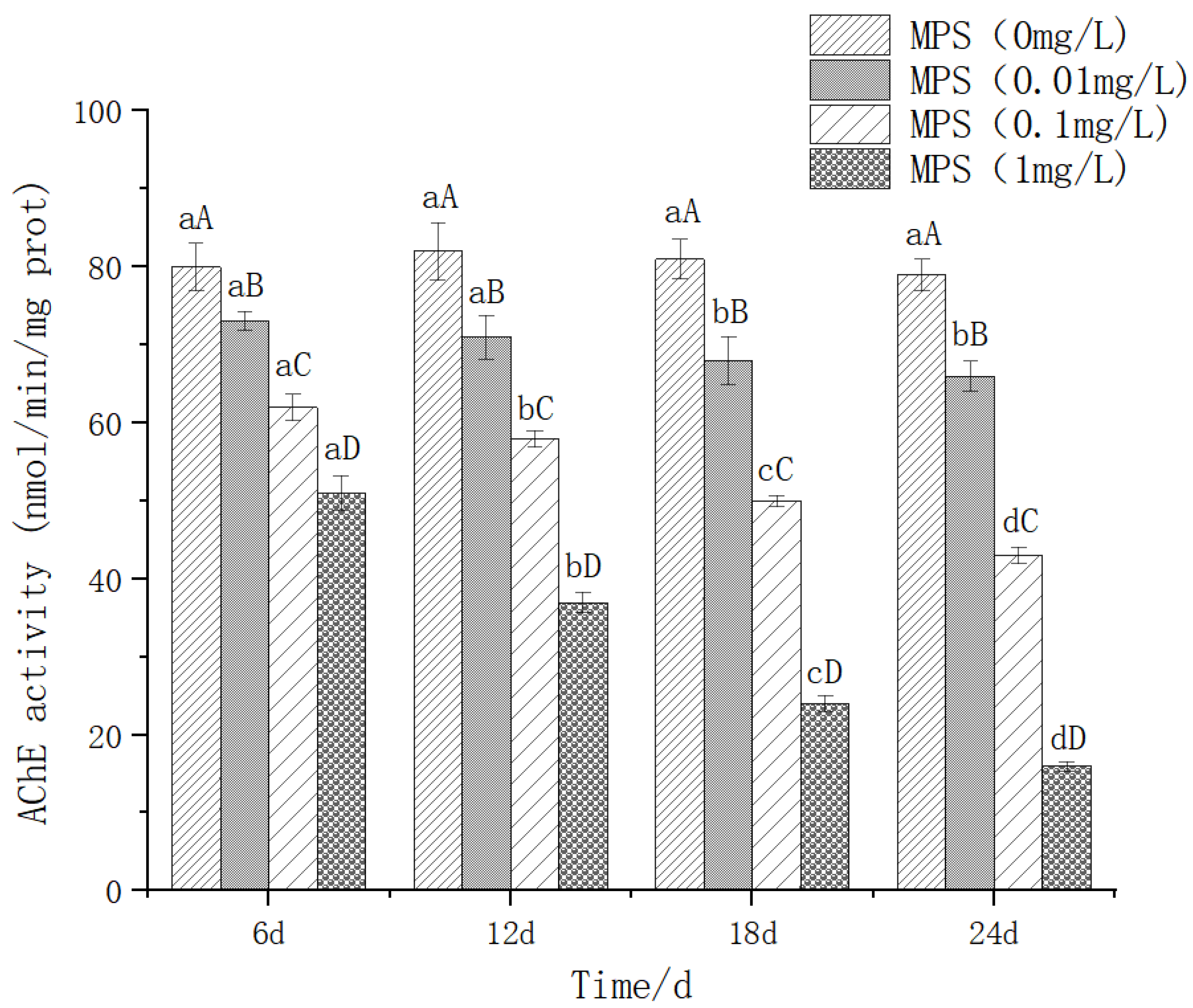

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of acetylcholinesterase (Ache) is shown in

Figure 6.As the concentration of microplastics increases, the activity of Ache generally decreases. There were significant differences in different concentrations of microplastics under the same number of days (

P< 0.05). The higher the concentration of polystyrene microplastics, the lower the Ache content. There was no significant difference between 6d and 12d in 0.01mg / l group (

P> 0.05). In 0.1mg / l and 1mg / l groups, Ache activity decreased significantly with the increase of days (

P< 0.05).

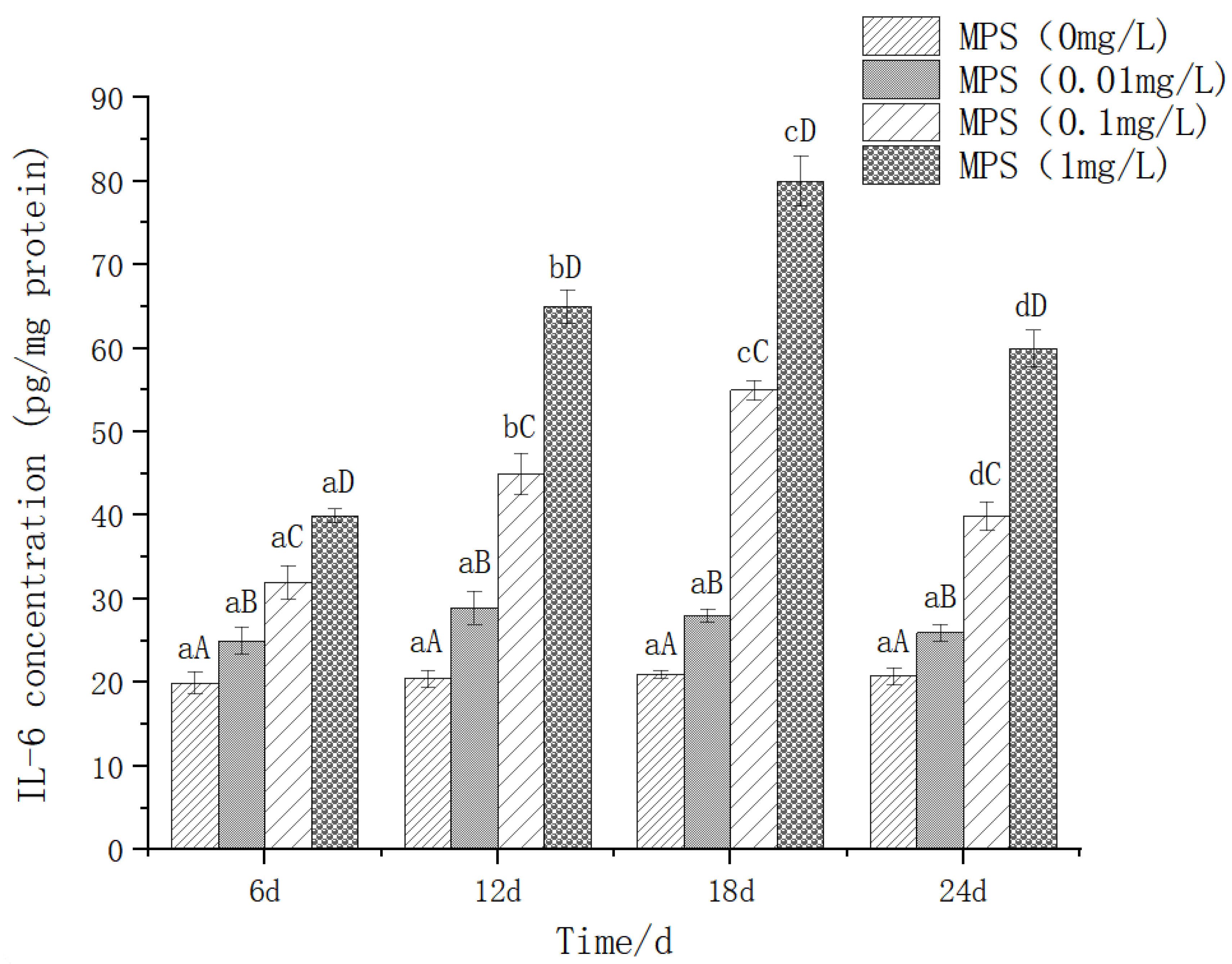

3.2.4. Proinflammatory Cytokine

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of IL-6 (interleukin-6) As shown in

Figure 7, on the same day, the higher the concentration of microplastics, the higher the expression level of IL-6, and the difference between them was significant (P< 0.05). The levels of IL-6 in the microplastic exposure group (0.1 mg/L and 1 mg/L) showed a significant concentration-time-dependent change (P< 0.05). With the prolongation of exposure time, the expression of IL-6 increased first and then decreased, reaching a peak at 18 days of exposure.

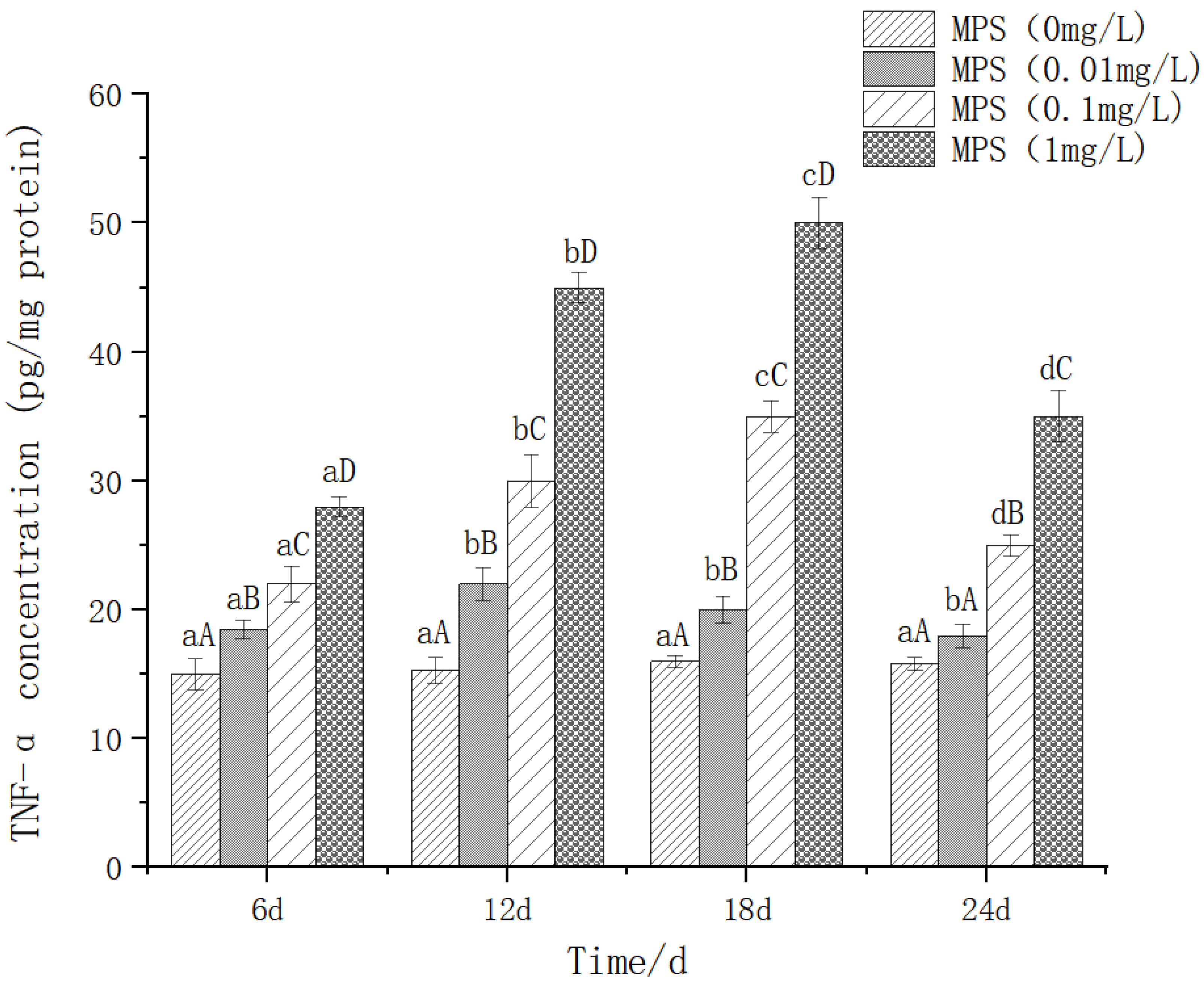

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the content of TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α) is shown in

Figure 8. On the same day, the higher the concentration of microplastics, the higher the expression level of TNF-α. There was no significant difference between 0mg/l and 0.01mg/l groups. There was a significant difference between 0.1mg/l and 1mg/l groups (P< 0.05), which showed a trend of increasing first and then decreasing, and the content of TNF-α was the highest on the 18th day.

3.3. Behavior

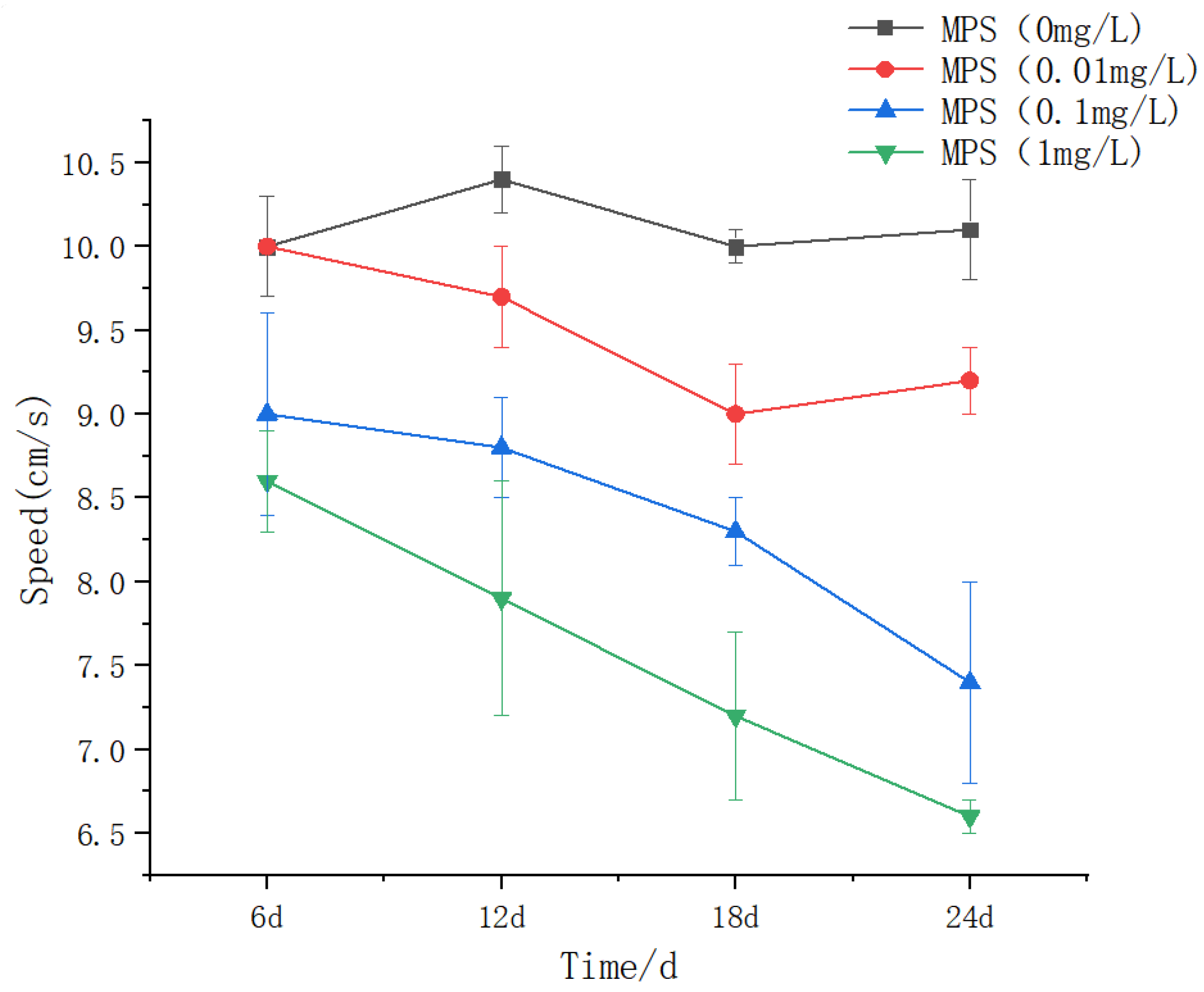

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the swimming speed of Sebastes schlegeliiAs shown in

Figure 9, there was no statistical difference in the 0 mg / L treatment group (P > 0.05). The swimming speed of 18 days and 24 days was significantly lower than that of 6 days and 12 days (

P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between 6 days and 12 days in 0.1 mg / L treatment group (

P > 0.05). The swimming speed of 18 days was significantly lower than that of 6 days and 12 days, and that of 24 days was significantly lower than that of the previous days (

P < 0.05). There were statistical differences in the 1 mg / L group, showing a downward trend. At 6 days, the 0.1 mg / L treatment group was significantly lower than the first two group, and the 1 mg / L treatment group was significantly lower than the first three groups (

P < 0.05). At 12 days, 0.1 mg / L and 1 mg / L treatment groups were significantly lower than 0 mg / L and 0.01 mg / L groups. At 18 days and 24 days, the differences between the groups were significant (

P < 0.05), and the higher the concentration, the smaller the speed.

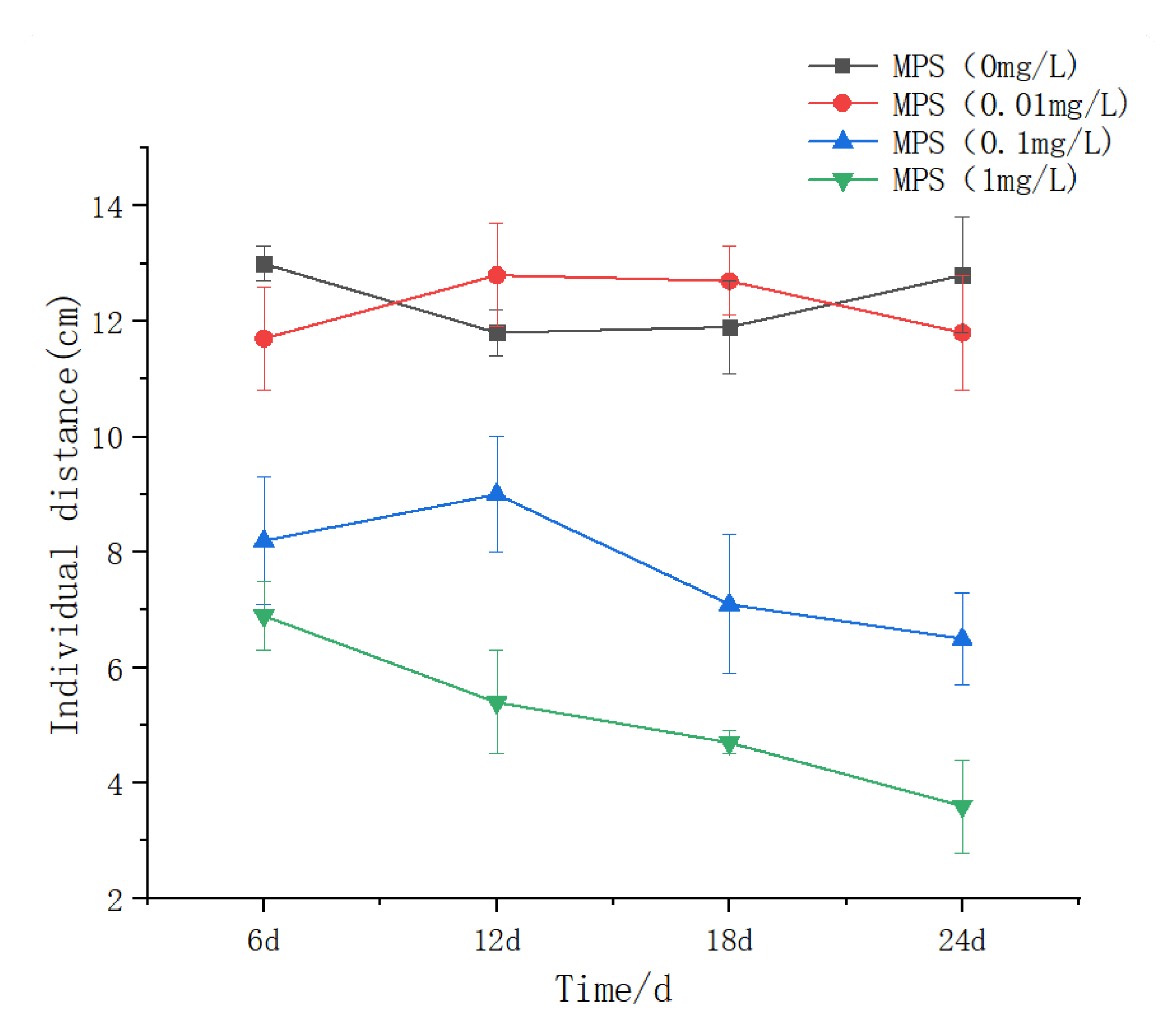

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the distance between individuals of Sebastes schlegelii. As shown in

Figure 10, the distance between individuals in the 0.01 mg / L group was lower than that in the control group at the beginning of the experiment, and increased from 6d to 12d and then decreased and stabilized. There was no significant difference between the control group (

P > 0.05). The distance between individuals in the 0.1 mg / L group was significantly lower than that in the 0 and 0.01 mg / L groups at 6d, slightly increased at 12d, and gradually decreased at 18d and 24d. The distance between individuals at 18d and 24d was significantly lower than that at 12d. At the beginning of the experiment, the distance between individuals in the 1 mg / L group was significantly lower than that in the first three groups and then continued to decrease significantly (

P < 0.05), indicating that high concentrations of microplastics had a significant effect on the behavior of fish, resulting in a further decrease in the distance between them.

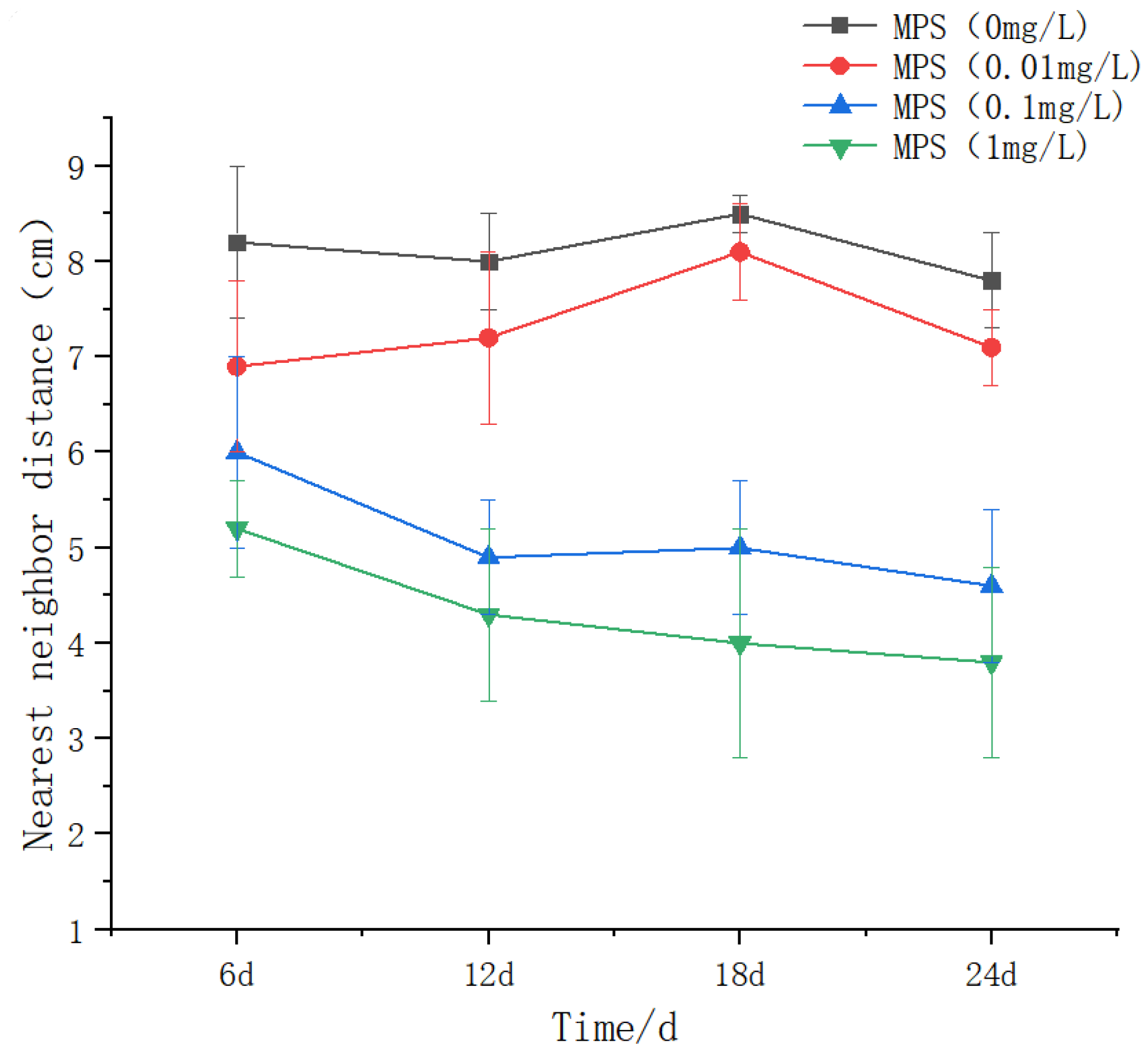

The effect of different concentrations of microplastics on the nearest neighbor distance of Sebastes schlegelii population as shown in

Figure 11. With the increase of MPS concentration, the value of the nearest distance generally showed a downward trend. There was no significant difference between the days in the 0.01 mg / L group (

P > 0.05), showing a slight upward trend on the 18th day, and the decline on the 24th day was close to that on the 6th day. The 0.1 mg / L group was significantly lower than the 0 and 0.01 mg / L groups at 6,12,18 and 24 days. 12d was significantly lower than 6d (

P < 0.05). 1 mg / L group, the difference between the groups was significant (

P < 0.05), which was significantly lower than that of the other groups on the same day. The difference within the group was significant, showing a downward trend.

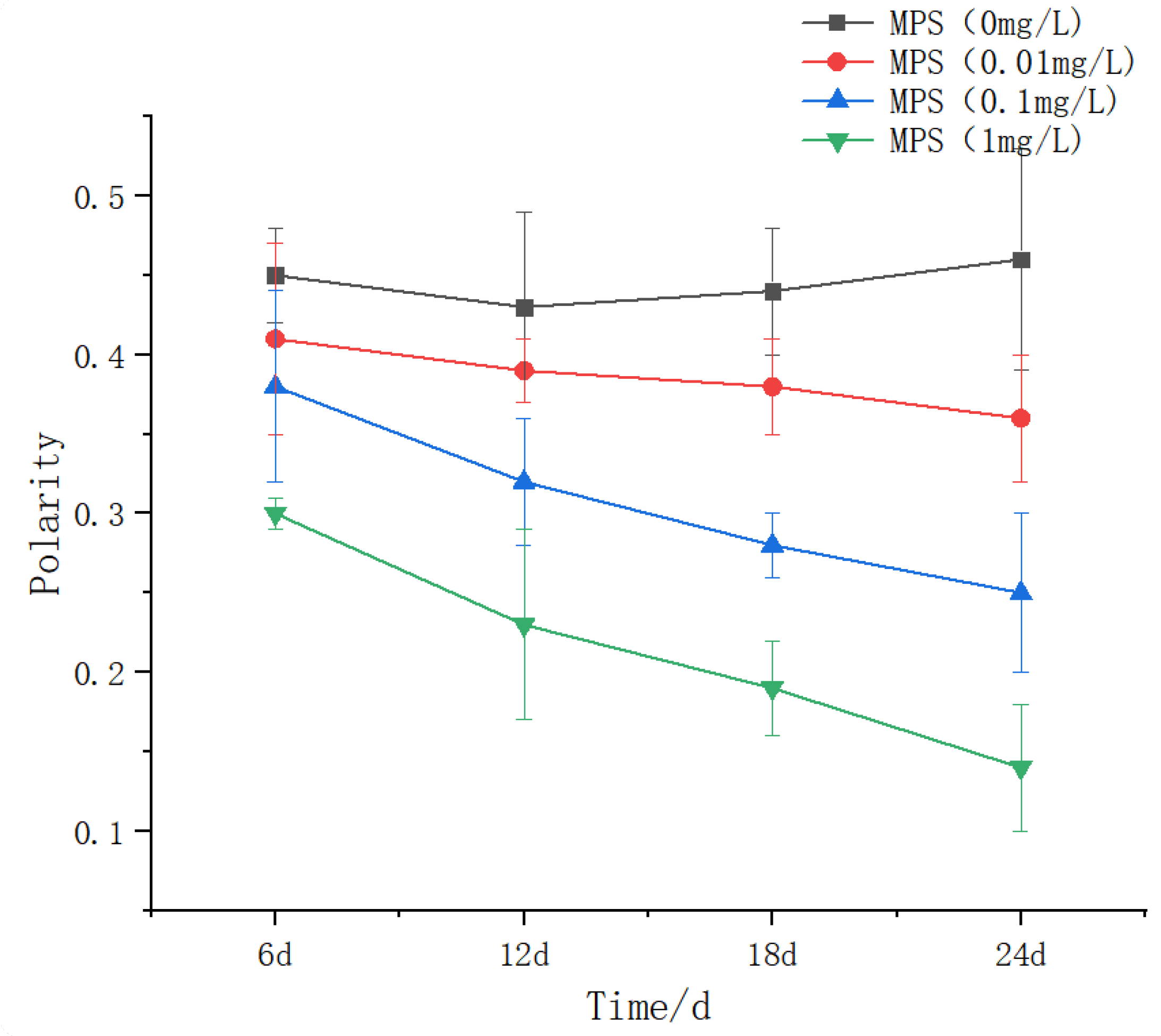

The effects of different concentrations of microplastics on the population polarity of Sebastes schlegelii are shown in

Figure 12.There was no significant difference between the 0.01 mg / L group at 6,12 and 18 days. The 24 days were significantly lower than the previous days (

P < 0.05), but showed a slight downward trend, and the 24 days were significantly lower than the previous days. The difference between the 1 mg / L group was significant (

P < 0.05), showing a downward trend.

Figure 13.

Group polarity of Sebastes schlegelii under different concentrations of microplastics.

Figure 13.

Group polarity of Sebastes schlegelii under different concentrations of microplastics.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Different Concentrations of Polystyrene Microplastics on the Growth of Juvenile Sebastes schlegelii

The biphasic growth effect of ‘ first promotion and then inhibition ‘ was observed in the 0.01 mg / L group (initial body weight increased significantly, later recession). This phenomenon is partially consistent with the Hormesis theory of low-concentration microplastics: In zebrafish (Danio rerio) studies, short-term exposure to low-concentration polyethylene microplastics (0.1 mg / L) can activate antioxidant enzyme systems (such as SOD, CAT), promote energy metabolism and growth, but long-term exposure leads to oxidative damage and growth inhibition. [

16] Similarly, the growth rate of juvenile European seabass (

Dicentrarchus labrax) increased briefly after 21 days of exposure to 0.1 mg / L polystyrene microplastics, but decreased significantly after 56 days, which was associated with intestinal inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction. [

17] There was no significant difference in body weight in the 0.1 mg / L group, but the weight growth rate (WGR) was inhibited in the middle stage. This result is different from freshwater fish research: Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to 0.1 mg / L polyethylene microplastics for 28 days, the growth was not significantly affected, but the liver antioxidant enzyme activity increased. [

18]. The possible reason is that the medium concentration of microplastics has not yet exceeded the physiological compensation threshold, but its transient inhibitory effect may be related to energy redistribution (such as immune response consumes resources). For example, Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) preferentially maintains basal metabolism rather than growth at similar concentrations, resulting in decreased growth efficiency [

19]. Exposure to 1 mg/L microplastics significantly inhibited the growth of juvenile Sebastes schlegelii (such as a decrease in weight growth rate). This result is highly consistent with the conclusions of most fish studies, and its core mechanism involves the synergistic effect of physical damage, metabolic disorders and oxidative stress. The inhibition of fish growth by high concentrations of microplastics (usually ≥ 1 mg/L) has been observed in a variety of species: Yellow catfish (

Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) exposed to 1,000 μg / L (i.e., 1 mg/L) polystyrene microplastics for 28 days, the body weight and growth rate decreased significantly, accompanied by intestinal vacuolization and decreased digestive enzyme activity. [

20] Crucian carp (

Carassius auratus) exposed to 1 mg/L polyethylene microplastics for 30 days showed significant weight loss and severe liver damage (such as cell vacuolization). [

21] Although there was no significant difference in growth of Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) exposed to 5 mg/L polyethylene microplastics, the liver oxidative stress index (MDA content, GST activity) was significantly increased, suggesting sublethal toxicity [

22].

4.2. Effects of Different Concentrations of Polystyrene Microplastics on the Physiology of Juvenile Sebastes schlegelii

Microplastic exposure induced significant oxidative stress, inflammatory response and neurotoxicity, and showed obvious concentration and time-dependent characteristics. At the beginning of the experiment (6d and 12d), the content of SOD increased significantly with the increase of microplastic concentration. This may be because low concentration of microplastics produced slight oxidative stress on the body. The body scavenged free radicals and maintained redox balance by increasing the synthesis of SOD [

23], which is consistent with some research results. Ding et al. [

24] found that the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the liver of red tilapia was significantly induced under microplastic exposure. Wang et al. [

25] found that low concentration of microplastics exposure can induce the increase of SOD activity in fish liver tissue, which is an antioxidant stress response of the body. At the later stage of the experiment (18d and 24d), the SOD content of the high concentration microplastics (1mg/L) group decreased significantly, and the oxidative damage of the high concentration microplastics to the liver significantly exceeded the compensatory ability of the body ‘s antioxidant defense system, resulting in a decrease in superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity [

26]. Liu et al. [

27] found that the activity of SOD in fish liver decreased under long-term exposure to high concentrations of microplastics. The content of MDA increased significantly with the increase of concentration-time, which indicated that microplastic exposure aggravated the degree of lipid peroxidation in the liver tissue of Sebastes schlegelii. MDA is the end product of lipid peroxidation. The increase of MDA content reflects the peroxidation of cell membrane lipids under the action of free radicals, which leads to the damage of cell structure and function [

28]. Oxidative stress induced by PS-MPs treatment PS-MPs (2 and 200 μm) increased MDA content in fish in a dose-dependent manner on day 7 [

29]. AST mainly exists in cells. When cells are damaged, AST will be released into the blood. The increase of AST content is an important indicator of liver cell damage [

30]. The AST content in the 0.01mg / L treatment group changed little at 6-18 days and increased at 24 days, which may cause chronic damage to hepatocytes due to long-term low-concentration microplastic exposure and aggravate with time. The AST content in the 0.1mg / L and 1mg / L treatment groups continued to increase significantly with time, further confirming that the damage of high-concentration microplastics to liver cells increased with time. The change of AKP content can reflect the pathological state of liver, and its release is related to the damage of liver cells and the change of membrane permeability [

31]. The results of this paper are similar to the experimental results of injecting different concentrations of polystyrene microplastics into the shell of Crassostrea rivularis. After 48 h of stress, AKP showed a trend of increasing first and then decreasing [

32]. The activity of LZM in the 0.1mg/L group at 24 d was significantly lower than that in the previous days, and that in the 1mg/ L group at 18-24 d was significantly lower than that at 6-12 d, showing a trend of increasing first and then decreasing, indicating that the inhibition of LZM activity by high concentration of microplastics had a time cumulative effect, and long-term exposure may damage immune function. Zhou et al. [

33] studied and evaluated the hepatotoxicity of 100 nm plastic on medaka after three months of chronic exposure, and found that the activity of lysozyme (LZM) decreased significantly after exposure to high concentration of nanoplastics. The higher the concentration of microplastics, the more significant the decrease of Ache activity, and the longer the exposure time at the same concentration, the more obvious the inhibition. This indicates that microplastics disrupt the nerve signal transduction function of Sebastes schlegelii by interfering with neurotransmitter metabolism or directly inhibiting enzyme activity. [

34] Studies have found that microplastic exposure leads to a significant decrease in AChE activity in fish brains [

35]. The increase of microplastic concentration and exposure time significantly increased the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, indicating that it induced a strong inflammatory response. In the 0.1 mg/L and 1 mg/L groups, IL-6 and TNF-α reached the peak at 18 days, and then decreased, which may be related to inflammation self-regulation or immunosuppression. There was no significant difference between 0 mg/L and 0.01 mg/L groups at each time point, indicating that low concentration of microplastics was not enough to trigger significant inflammation. Microplastics may drive excessive release of inflammatory factors by activating immune cells (such as macrophages) or pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (such as NF-κB). This is similar to the results that in zebrafish, 0.5μm microplastic exposure significantly increased the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 [

36]. 80 nm microplastics induced up-regulation of TNF-α by 4 times in grass carp [

37].

4.3. Effects of Different Polystyrene Microplastic Concentrations on the Behavior of Juvenile Sebastes schlegelii

The degree of inhibition of swimming speed was significantly positively correlated with microplastic concentration and exposure time. The swimming speed of the 0.1 mg/L and 1 mg/L treatment groups decreased to the lowest at 24 days (significant difference between the groups, P < 0.05), and the 1 mg/L group showed a monotonous downward trend, indicating that the high concentration of microplastics caused irreversible damage through continuous bioaccumulation. This is consistent with the study of zebrafish exposed to polystyrene microplastics (PS-MPs): 5μm MPs accumulate in the liver and lead to insufficient energy supply by inducing oxidative stress ( ncreased SOD and CAT activity ) and lipid metabolism disorders [ 38 ]. The 0.01 mg / L group showed a significant decrease in 18-24 days (

P < 0.05), but there was no difference in 6-12 days, suggesting that low concentration exposure had threshold effect and time dependence. A similar phenomenon was observed in African tilapia. After 15 days of exposure to 1 mg / L microplastics, antioxidant enzyme activity and DNA damage could be restored, while higher concentrations caused irreversible damage [

39].

The effect of polystyrene microplastics ( PS-MPs ) on the distance between individuals of Sebastes schlegelii showed a concentration-dependent and time-cumulative effect: there was no statistical difference between the 0.01 mg / group and the control group (

P > 0.05 ), indicating that the environment-related concentration ( such as the abundance of PS-MPs in the surface water of the North Atlantic 0.02-0.1 mg / L ) has not yet exceeded the behavioral interference threshold [ 40 ]. This is in contrast to the sensitivity of zebrafish (Danio rerio) to exercise inhibition at 7 days under 0.05 mg / L PS-MPs [

41,

42], reflecting that Sebastes schlegelii has stronger metabolic buffering capacity as a carnivorous reef fish [

43]. In the 0.1 mg/L group, the distance at 6 days was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05), reflecting acute neurotoxicity; the continuous decrease in 18-24 days suggests a chronic cumulative effect, which may be related to the inhibition of cholinesterase activity caused by MPs enrichment in brain tissue [

44,

45]. Santos et al.found that zebrafish exposed to 1-5 μm MPs (2 mg/L) had no behavioral changes in acute tests (≤96 h), but chronic exposure (14 days) significantly reduced swimming distance to support the time accumulation of low-concentration effects. The recovery ability of S.schlegelii may be due to the environmental adaptation advantage brought by its high habitat loyalty (habitat index 0.90 ±0.13). The whole distance of the 1 mg / L group was significantly reduced (

P < 0.05), and continued to decline, indicating that high concentrations of MPs directly destroy the motor coordination ability, which is related to muscle nerve fiber damage and decreased acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity [

39]. The benthic habits of Sebastes schlegelii make it easier to access high-density MPs (such as PVC, PET). Compared with planktonic fish, its escape behavior is limited. For example, the swarming behavior of Sebastes marmoratus decreases after exposure to 15 μm MPs [

47], while Sebastes schlegelii aggravates the compression of inter-individual distance. The nearest neighbor distance was delayed at low concentrations (0.01 mg/L), and there was no significant difference in NND in the 0.01 mg / L group throughout the experiment (

P > 0.05), only a brief increase (stress compensation) after 18 days, indicating that the environmental concentration MPs (≤0.01 mg/L) did not break through the behavioral regulation threshold. Short-term exposure can maintain spatial behavior homeostasis through physiological compensation [

48]. NND in the 0.1 mg / L group was significantly lower than that in the control group at 6 days.The results showed that the inhibition of irreversible behavior induced by medium concentration of MPs was related to the penetration of MPs into the blood-brain barrier and the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity [

49]. The whole NND in 1 mg/L group was significantly lower than that in other groups (

P < 0.05), and continued to decrease with time, reflecting that high concentration of MPs led to progressive motor dysfunction. The NND of Sebastes schlegelii continues to compress after MPs exposure, which is related to its ecological habits of strong territoriality and weak escape ability [

50].

In terms of group polarity, there is a downward trend. 0.01 mg / L group: There was no significant change in polarity between 6-18 days (

P > 0.05), and it decreased significantly at 24 days (

P < 0.05), indicating that low concentration MPs need long-term exposure to break through the steady-state threshold of behavior. 0.1 mg / L group: the polarity decreased slightly from 6 to 18 days (no statistical difference), and decreased significantly at 24 days (

P < 0.05), reflecting the neurotoxicity lag effect of medium concentration MPs. Lu et al. [

50] studied that zebrafish was exposed to 0.05 μm PS-MPs for 7 days to inhibit motor coordination (swimming speed decreased by 40%), which was similar to the mechanism of polarity decline in the 0.1 mg / L group of Sebastes schlegelii, both due to acetylcholinesterase inhibition and liver metabolism disorders. After 28 days of exposure to polyethylene MPs, glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity was significantly modulated, accompanied by discrete group behavior, which was consistent with the decrease of 24-day polarity in the 0.01 mg / L group of Sebastes schlegeli. The response threshold of carp was higher (0.5 mg / L), but the time effect pattern was similar [

51].

5. Conclusions

This study systematically explored the comprehensive effects of different concentrations of polystyrene microplastics (0,0.01,0.1,1 mg/L) on the physiological function and group behavior of juvenile Sebastes schlegelii. The results showed that microplastic exposure could induce significant oxidative stress, inflammatory response and neurotoxicity, and interfere with the social behavior patterns of fish, and these effects showed obvious concentration and time dependence.

At the physiological level, microplastics could activate the body ‘s antioxidant defense system (such as increased SOD activity) at the initial stage of exposure (6-12 d). However, with the prolongation of exposure time (18-24 d), the antioxidant capacity of the high concentration group (0.1-1 mg / L) decreased significantly, while lipid peroxidation products (MDA) and inflammatory factors (IL-6, TNF-α) continued to accumulate, indicating that oxidative damage and inflammatory response were aggravated. The abnormality of liver function indexes (AST, AKP) further confirmed that microplastics could endanger fish health through metabolic disorders and cell damage. The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity suggests that microplastics may interfere with nerve signal transduction and affect motor coordination.

At the behavioral level, microplastic exposure resulted in decreased swimming speed, decreased distance between individuals, and decreased group polarity, indicating that fish ‘s athletic ability and social cohesion were impaired. The behavioral abnormalities in the high concentration group (1 mg / L) were particularly significant. The level of microplastic pollution should be strictly controlled in mariculture management to reduce its ecological risk to economic fish and the subsequent food chain transmission effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., S.L., T.T., Z.H.,Z.W.,J.Y. and S.Y.; methodology, Z.W., S.L. and Z.H.; software, S.W., L.S. and X.W.; validation, S.M. and S.L.; formal analysis, S.W., S.L., T.T. and S.Y.; investigation, S.M.,S.L., Z.H. and J.Y.; resources, S.W.,J.Y. and S.L.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W., Z.H., Z.W. and T.T.; visualization, S.Y. and Z.W.; supervision, T.T.; project administration, T.T.; funding acquisition, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

The National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD2401103)

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out in 2023. We thank Tao Tian for his mentorship and help. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Dalian Ocean University Liaoning Province Marine Ranch Research Center for their help in the completion of this research, especially Zhongxin Wu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Hou M, Wang C, Xu C., et al. Effects of polystyrene microplastic exposure on the growth of rare juvenile crucian carp. Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2020, 39(2), 8.

- Thompson C R, Olsen Y, Mitchell P R, et al. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? [J]. Science, 2004, 304(5672): 838-838. [CrossRef]

- Yu P, Liu Z Q, Wu D L, et al. Accumulation of polystyrene microplastics in juvenile Eriocheir sinensis and oxidative stress effects in the liver[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2018, 200: 28-36.

- Jin Y, Xia J, Pan Z, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut of adult zebrafish[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 235322-329. [CrossRef]

- Qiang L Y, Cheng J P. Exposure to microplastics decreases swimming competence in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 176: 226-233. [CrossRef]

- Huaxin Gua, Shixiu Wang, Xinghuo Wang, et al. Nanoplastics impair the intestinal health of the juvenile large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 397: 122773. [CrossRef]

- Ingrid F S D, Luiza M F, Benetis T P, et al.Multilevel Toxicity Evaluations of Polyethylene Microplastics in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,2023,20(4):3617-3617. [CrossRef]

- Wan Z, Wang C, Zhou J, et al. Effects of polystyrene microplastics on the composition of the microbiome and metabolism in larval zebrafish[J]. Chemosphere, 2019,217646-658. [CrossRef]

- Jeong S, Jang S, Kim S S, et al. Size-dependent seizurogenic effect of polystyrene microplastics in zebrafish embryos[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 439: 129616. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Gundlach M, Yang S, et al. Quantitative investigation of the mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics toward zebrafish larvae locomotor activity[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 584-585: 1022-1031. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B, Li, Z, & Jin, X. Food composition and food selectivity of Sebastes schlegelii. Chinese Journal of Aquaculture,2014, 21(1), 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Feng J, Zhao W, et al. Evaluation of the Residency of Black Rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) in Artificial Reef Areas Based on Stable Carbon Isotopes[J]. Sustainability, 2024,16(5):. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Effects of aquaculture density and models on growth environment and growth performance of Sebastes schlegelii[D]. Dalian: Dalian Ocean University, 2023.

- Zhang Y C, Wen H S, Li L M, et al. Effects of acute temperature stress on the reproductive endocrine function of gestational ovoviviparous black rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) [J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2016, 46(9): 29-37.

- Han X, Z. Study on feeding method of Korean rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) and its response mechanism to starvation stress[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ocean University, 2023.

- Lönnstedt M O, Eklöv P. Environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastic particles influence larval fish ecology[J]. Science, 2016,352(6290):1213-1216. [CrossRef]

- Kay C, O M H. Effects of microplastic exposure on the body condition and behaviour of planktivorous reef fish (Acanthochromis polyacanthus). [J]. PloS one,2018,13(3): e0193308. [CrossRef]

- Hurt R, O’Reilly M C, Perry L W. Microplastic prevalence in two fish species in two U.S. reservoirs[J]. Limnology and Oceanography Letters,2020,5(1):147-153. [CrossRef]

- Nicieza A G, Metcalfe N B. Growth compensation in juvenile Atlantic salmon: responses to depressed temperature and food availability[J]. Ecology, 1997, 78(8): 2385-2400. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J, Fan, B, Yuan, J, et al. Combined toxic effects of environmental concentration oxytetracycline and polystyrene microplastics on the intestine of juvenile yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco). Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2023, 18(1):426–439.

- Hu, J, Zuo, J, Li, J, et al. Effects of microplastics on the growth, liver damage, and intestinal microbiota composition of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Environmental Science, 2022,43(7), 3664–3671.

- Zhang, X, Yu, Q., Zhao, Y., et al. Effects of polyethylene microplastics on the growth, antioxidant capacity, immune response, and intestinal microbiota of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2022, 17(6), 301–314.

- Que, K, Meng, S., Zhang, D., et al. Effects of microplastics on the antioxidant enzyme system of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2022,17(2), 38–48.

- Guo H, Zhang X, Johnsson I J. Effects of size distribution on social interactions and growth of juvenile black rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) [J]. Applied Animal Behaviour Science,2017,194135-142. [CrossRef]

- Udayadharshini S, Saliya R A, Shanu V, et al. Effects of microplastics, pesticides and nano-materials on fish health, oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanism[J]. Frontiers in physiology, 2023, 14: 1217666. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X, Shi, D., Han, Y, et al. Combined exposure to microplastics and MEHP inhibits SIRT3/SOD2-mediated mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress in hepatocytes. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2024, 19(3), 363–372.

- Zhou S, Lin H, Liu Z, et al. The impact of co-exposure to polystyrene microplastics and norethindrone on gill histology, antioxidant capacity, reproductive system, and gut microbiota in zebrafish (Danio rerio) [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2024, 273: 107018. [CrossRef]

- Gawe S, Wardas M, Niedworok E, et al. Malondialdehyde (MDA) as a lipid peroxidation marker[J]. Wiad Lek, 2004, 57(9-10): 453-455.

- Shibo F, Yanhua Z, Zhonghua C, et al. Polystyrene microplastics alter the intestinal microbiota function and the hepatic metabolism status in marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) [J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2020, 759 (prepublish): 143558.

- Yu H R, Tsai C Y, Chen W L, et al. Exploring Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Dysregulation in Lung Tissues of Offspring Rats Exposed to Prenatal Polystyrene Microplastics: Effects of Melatonin Treatment[J]. ANTIOXIDANTS, 2024, 13(12):1459. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M, Gao, F, Wang, X., et al. Effects of microplastics on immune and digestive physiology of black sea cucumber (Holothuria atra). Marine Sciences, 2021,45(4), 126–135.

- Mu, H, Wang, R, Wang, J, et al. Effects of microplastics on the immunity of estuarine oyster (Crassostrea ariakensis). Marine Sciences,2023, 47(9), 53–60.

- Long-Term Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoplastics Impairs the Liver Health of Medaka Ribeiro F, Garcia A R, Pereira B P, et al. Microplastics effects in Scrobicularia plana[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2017, 122(1-2):379. [CrossRef]

- Minne Prüst, Meijer J, Westerink R H S. The plastic brain: neurotoxicity of micro- and nanoplastics[J]. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 2020, 17: 24. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y, Zhu, J, Hu, J., Zhang, Z., Li, L., & Wu, Q. Co-exposure to different sized polystyrene microplastics and benzo[a]pyrene affected inflammation in zebrafish and bronchial-associated cells. Science Bulletin, 2020, 65(36), 4281–4290. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Wang F, Wang Q, et al. Species-specific effects of microplastics on juvenile fishes[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2023, 14(000):9. [CrossRef]

- Lönnstedt M O, Eklöv P. Environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastic particles influence larval fish ecology [J]. Science, 2016, 352 (6290): 1213-1216. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Luo Z, Li C, et al. Antioxidant responses, hepatic intermediary metabolism, histology and ultrastructure in Synechogobius hasta exposed to waterborne cadmium [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2011, 74 (5): 1156-1163. [CrossRef]

- Yifeng L, Yan Z, Yongfeng D, et al. Response to Comment on “Uptake and Accumulation of Polystyrene Microplastics in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and Toxic Effects in Liver”. [J]. Environmental science & technology, 2016, 50 (22): 12523-12524. [CrossRef]

- Sun Z, Wu B, Yi J, et al. Impacts of Environmental Concentrations of Nanoplastics on Zebrafish Neurobehavior and Reproductive Toxicity. [J]. Toxics, 2024, 12 (8): 617-617. [CrossRef]

- Giacomo L, Annalaura M, Assja B, et al. Microplastics induce transcriptional changes, immune response and behavioral alterations in adult zebrafish[J]. Scientific reports, 2019, 9(1): 15775.

- Martha K, C. D B, Despoina X, et al. Toxicity and Functional Tissue Responses of Two Freshwater Fish after Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics[J]. Toxics, 2021, 9(11): 289-289.

- Xue, Y, Zhang, M., Xu, Z., Hu, J., & Li, L. Sources, distribution, and ecological toxicity effects of microplastics in aquatic environments on fish. Fisheries Science, 2023, 42(6), 1081–1090.

- Li, S, Zhao, Z., Sui, C., et al. Research progress on neurobehavioral toxicity in fish. Journal of Aquatic Biology, 2023, 47(2), 355–364.

- Wang, X, & Yan, Y. (2023). Research progress on neurobehavioral toxicity in fish. Aquaculture, 44(8), 42–48.

- Yin L, Liu H, Cui H, et al. Impacts of polystyrene microplastics on the behavior and metabolism in a marine demersal teleost, black rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii) [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 380120861. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W, Bao, Y, Jing, M, et al. Effects of microplastics on the morphology, behavior, and physiological characteristics of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis) hatchlings. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 2024, 47(1), 68–81.

- Wright L S, Thompson C R, Galloway S T. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2013, 178483-492. [CrossRef]

- Yong Y Q C, Valiya veetill S, Tang L B. Toxicity of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Mammalian Systems [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 17 (5): 1509.

- Xia, B, Du, Y, Zhao, X, et al. Research progress on microplastics pollution in marine fishery water and their biological effects[J]. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2019, 40(3): 178-190.

- S. P, P. M, K. D, et al. The effect of planktivorous fish on the vertical flux of polystyrene microplastics [J]. The European Zoological Journal, 2023, 90 (1): 401-413.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).