Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

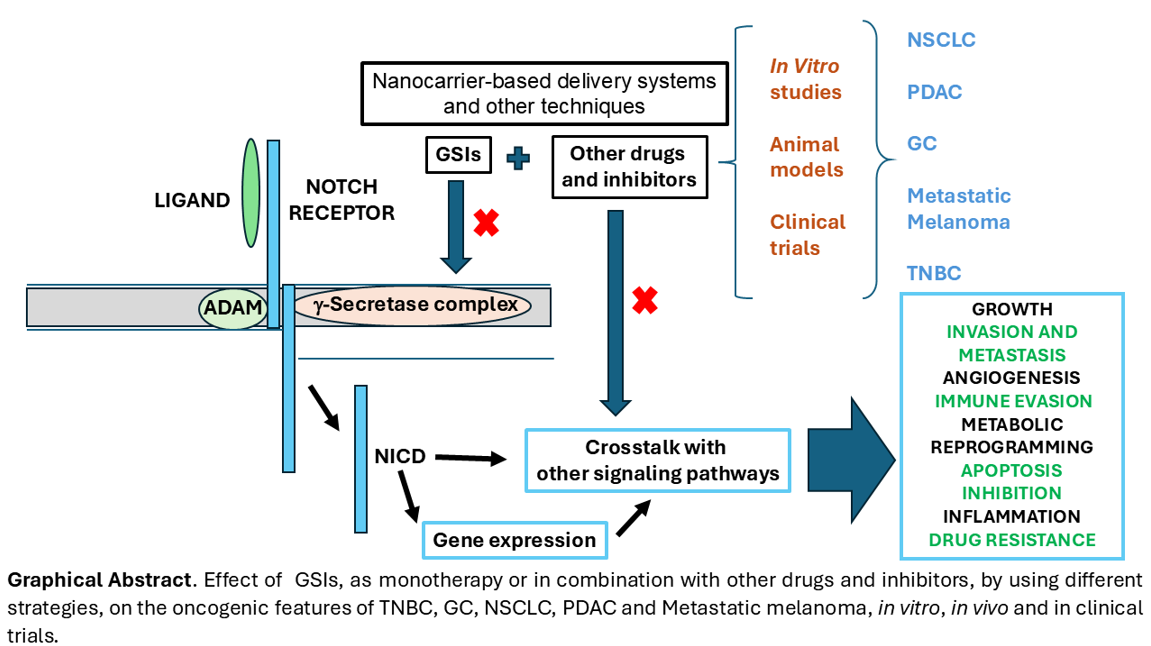

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

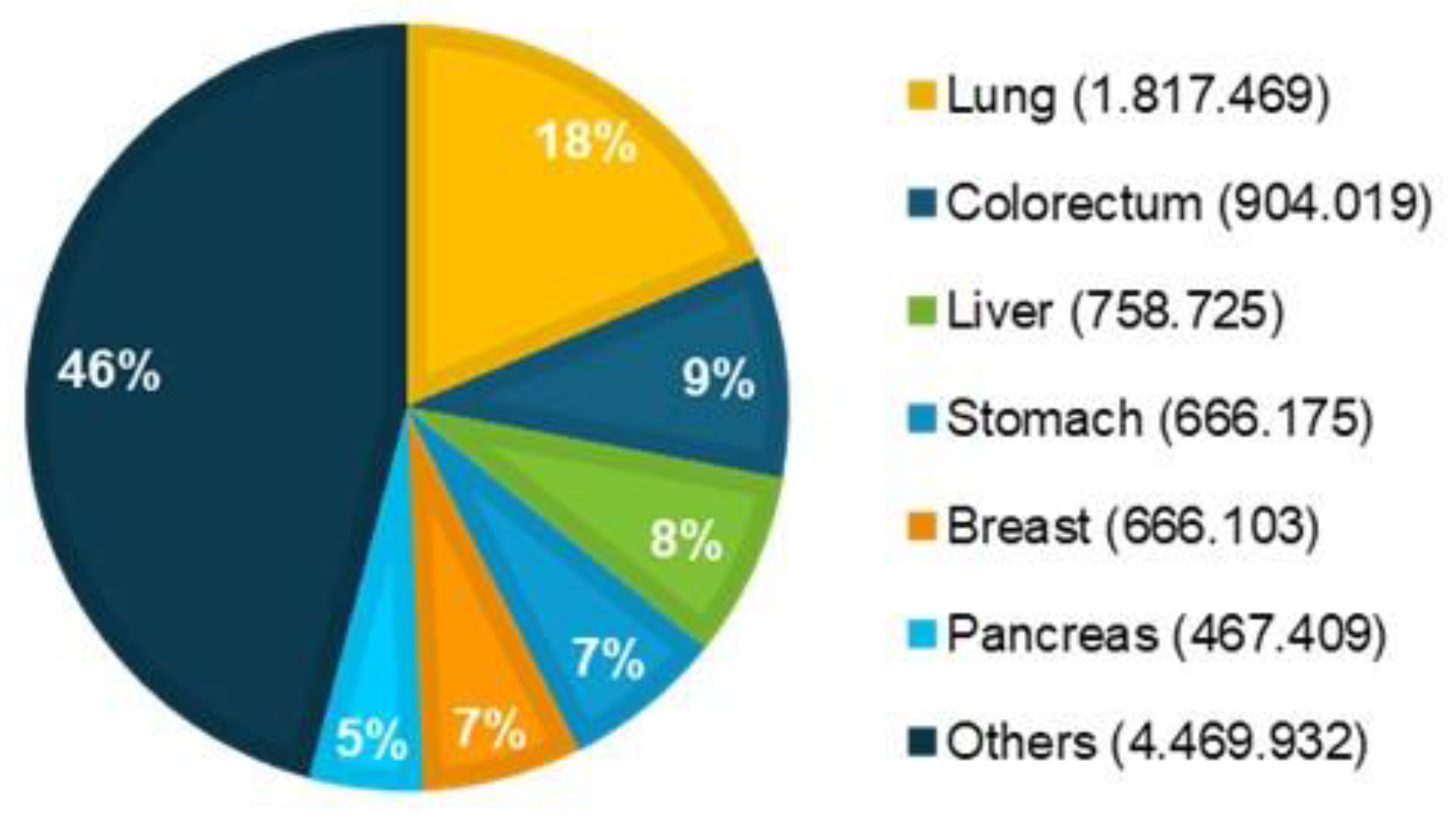

1.1. Global Cancer Epidemiology Overview

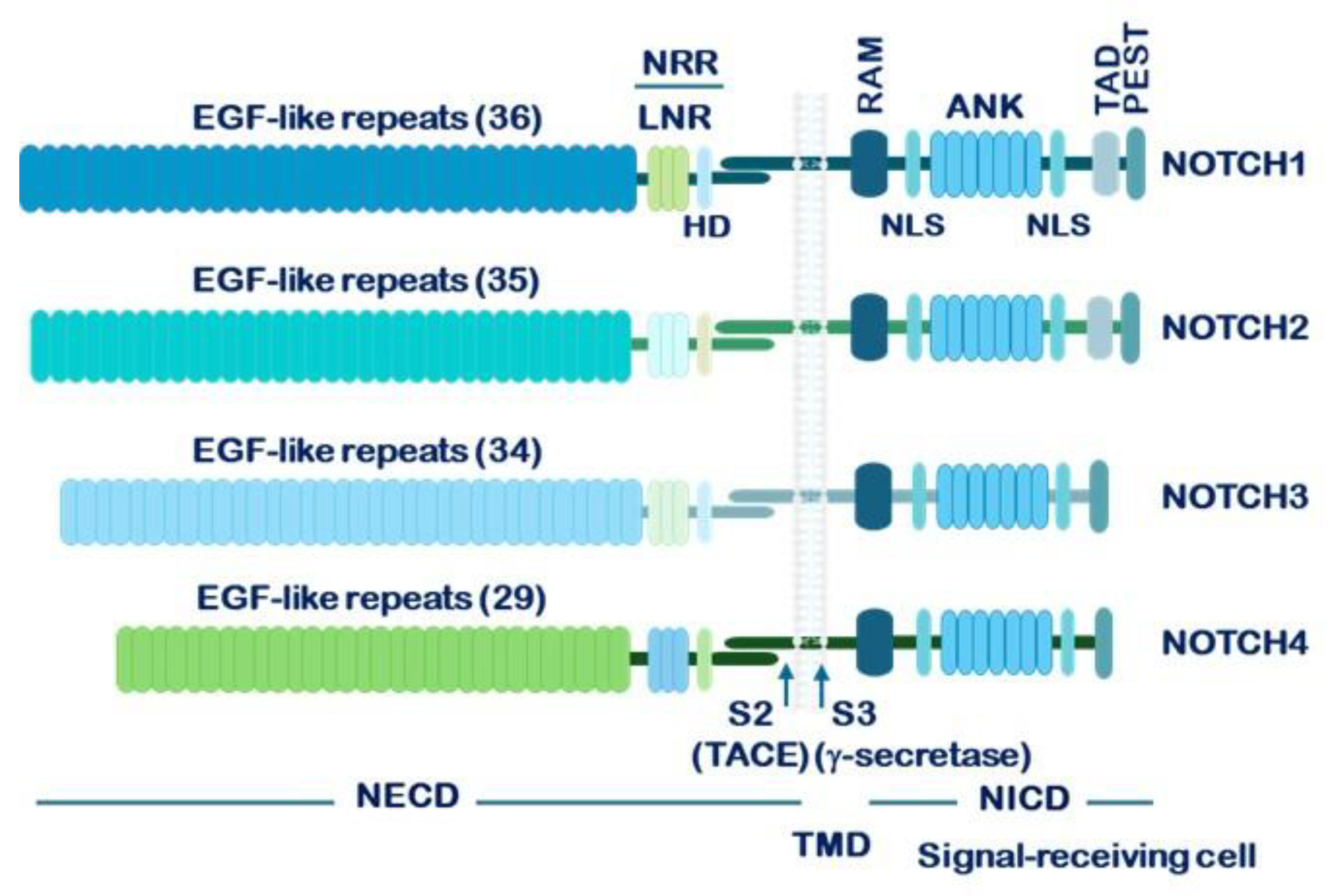

1.2. Structure of NOTCH Receptors and Their Ligands

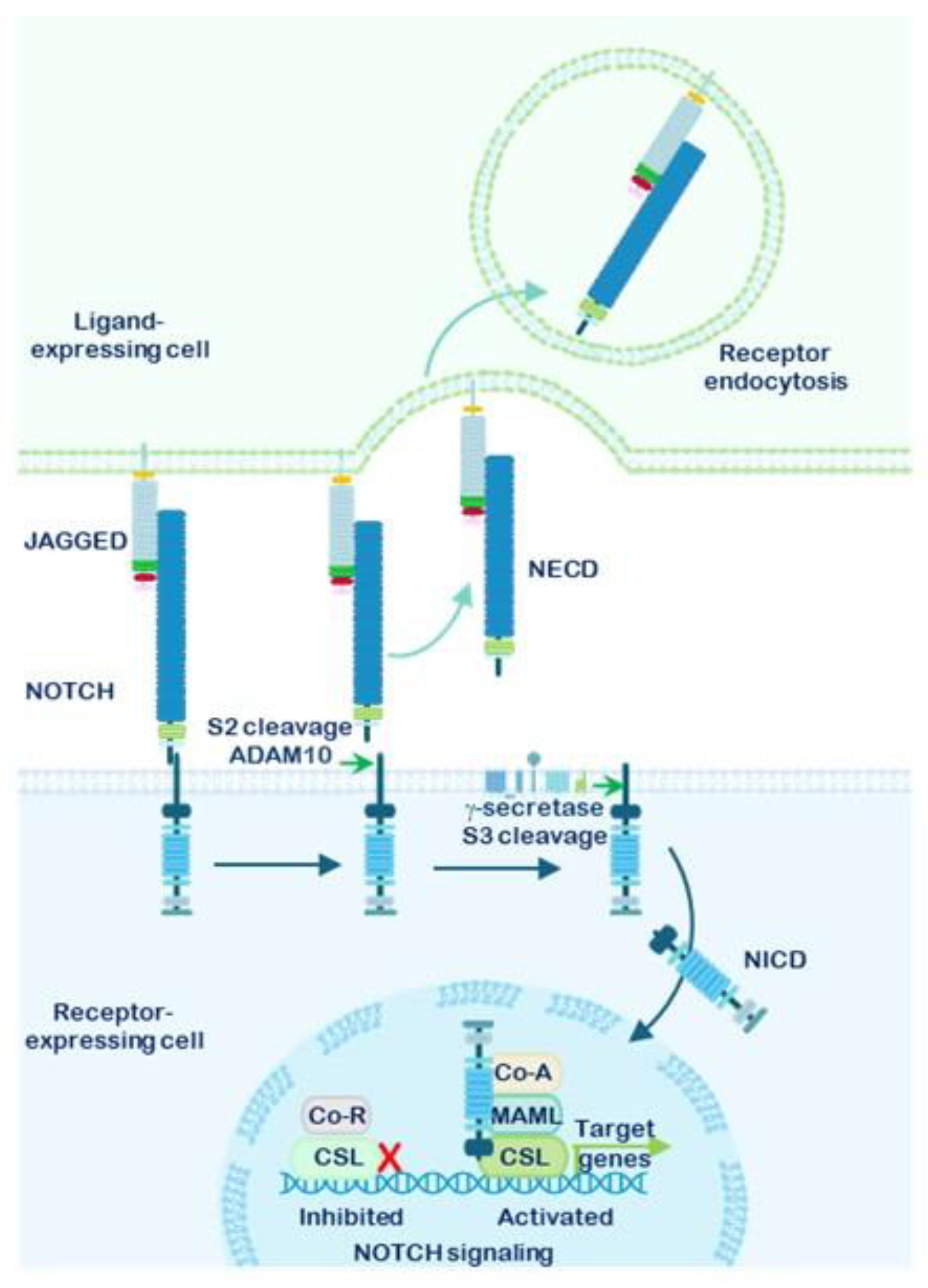

1.3. Mechanism of NOTCH Receptor Activation and Downstream Signaling

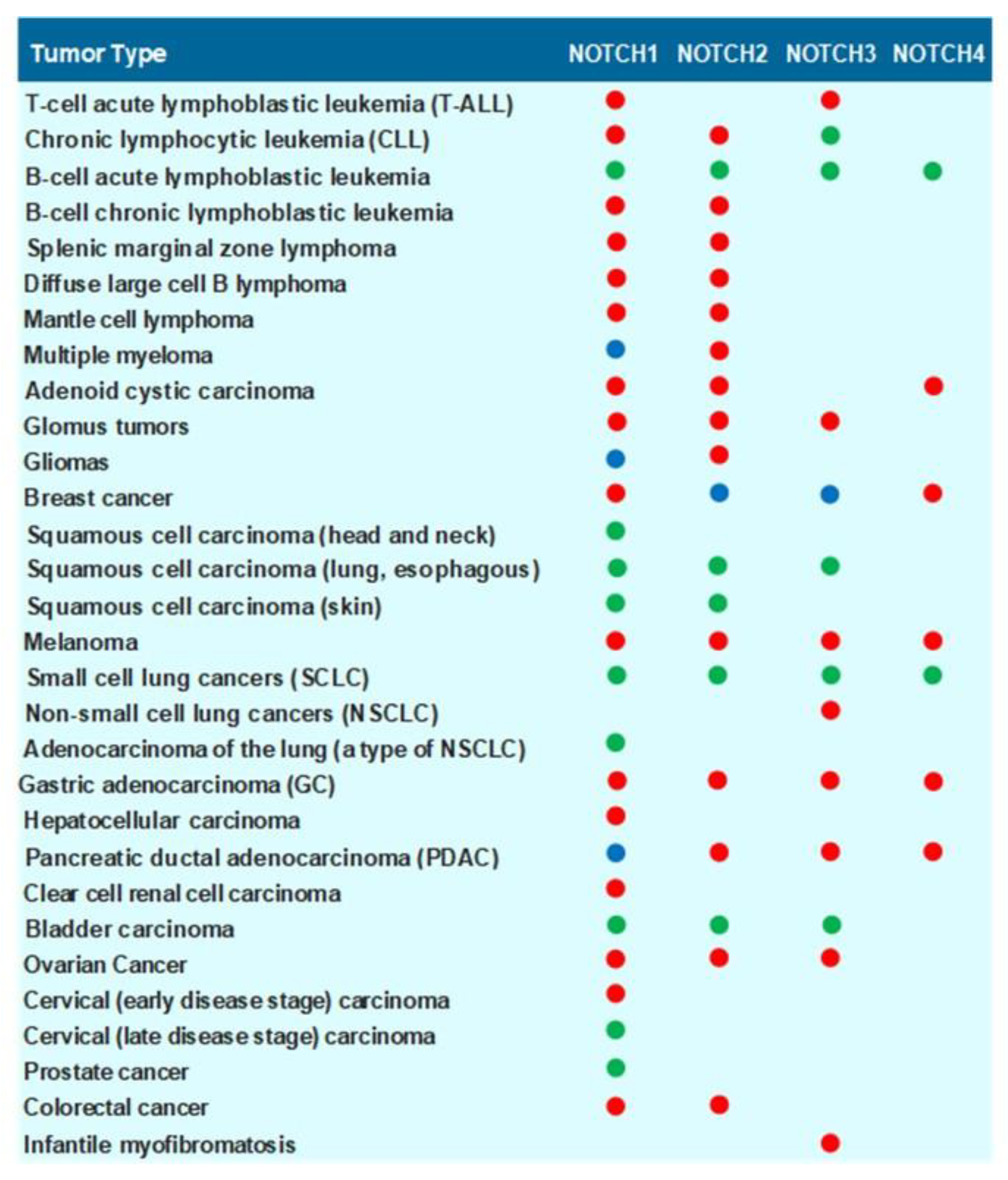

1.4. Role of NOTCH Receptors and NOTCH Ligands in Carcinogenesis

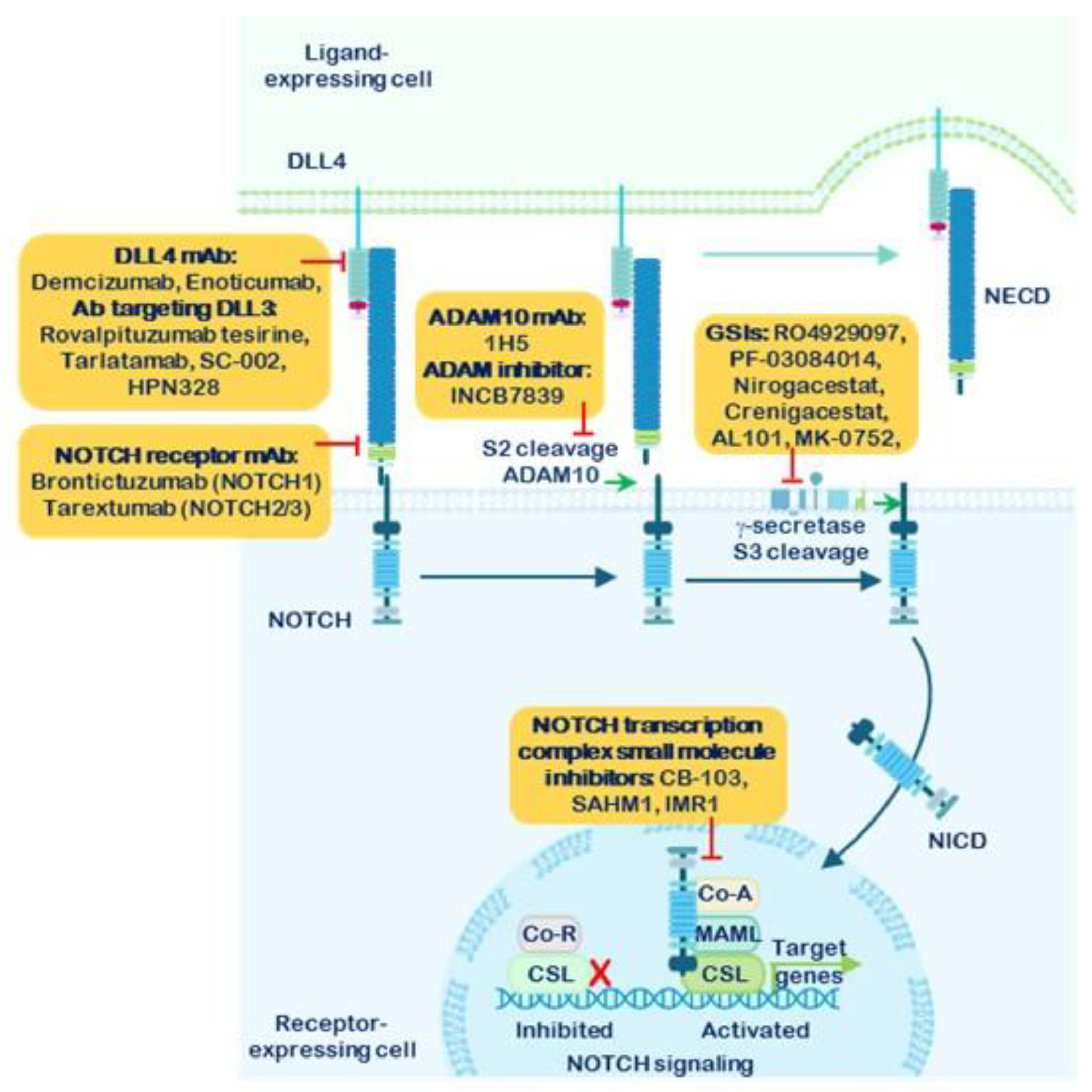

1.5. Strategies for the Inhibition of NOTCH Receptor Signaling

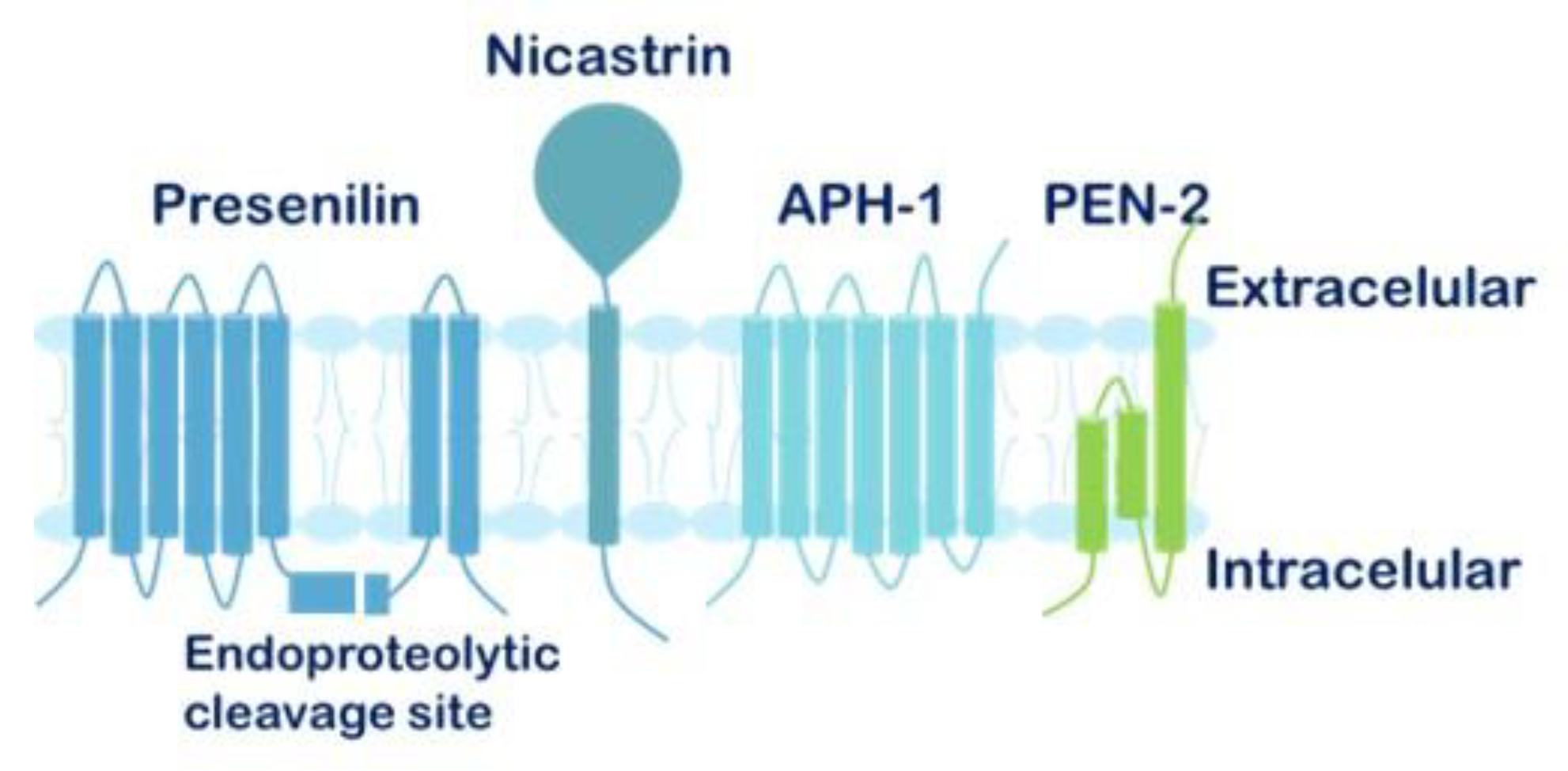

1.6. The γ-Secretase Complex and γ-Secretase Complex Inhibitors (GSIs)

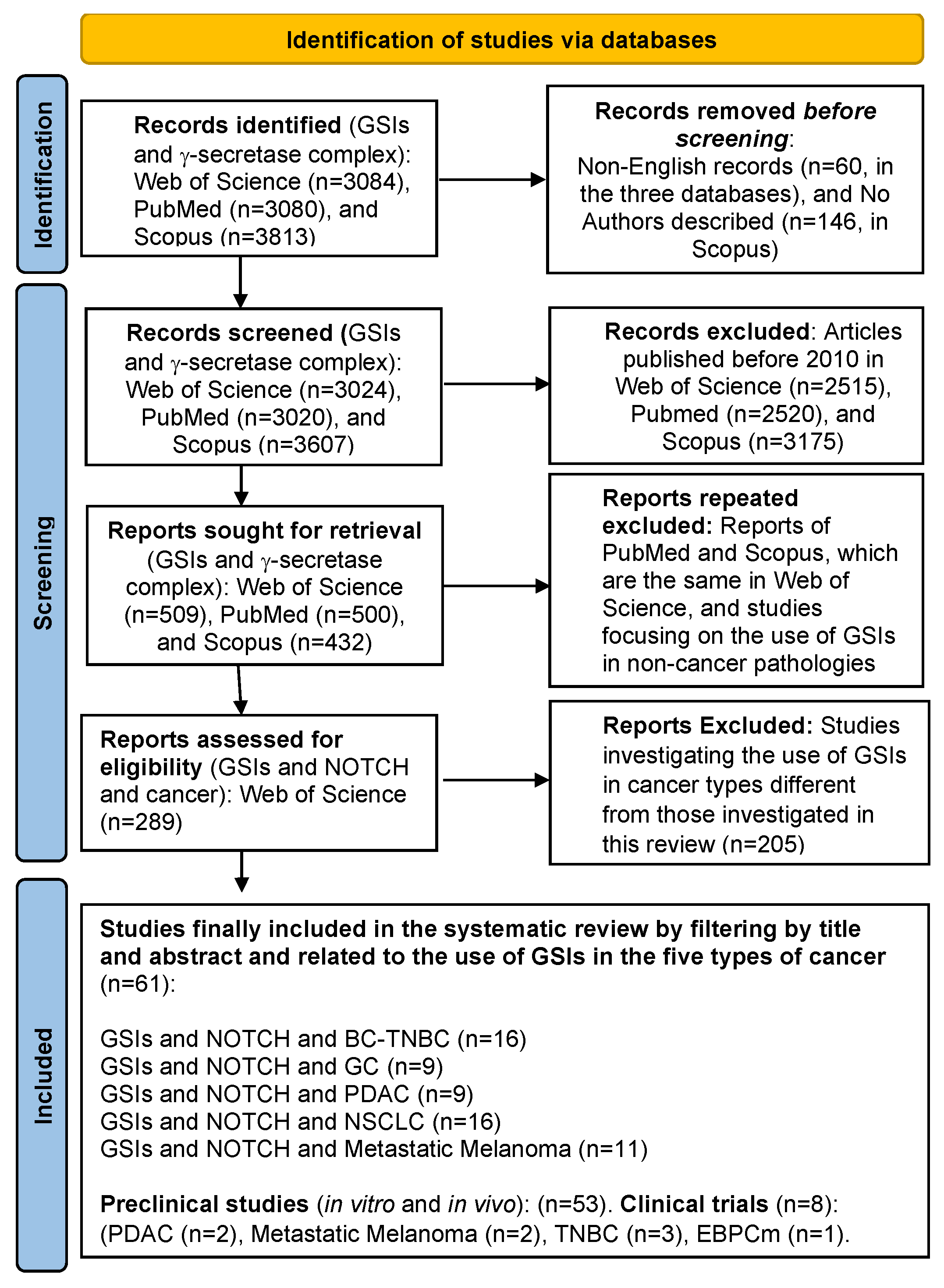

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Combination of GSIs with Other Therapeutic Agents has Demonstrated Efficacy in Reducing Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) Progression

3.2. Treatment Resistance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Can Be Mitigated Through the Application of γ-Secretase Inhibitors as Monotherapy and Combined with Other Drugs

3.3. The Use of GSIs, ADAM Inhibitors and Other Combined Therapies Have Contributed to Elucidating the Role of NOTCH Signaling in Gastric Cancer (GC)

3.4. GSIs Enhance the Efficacy of Targeted Therapies for Metastatic Melanoma

3.5. Various Works Explore the Use of GSIs as Monotherapy and in Combination Therapies for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Abbreviations

| ABT-737 | Bcl-2 inhibitor |

| ADAM | A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B (PKB) |

| ALDH | aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| ATRA | All-trans retinoic acid. |

| BCL2i | BLC-2 inhibitors. |

| BCSCs | Breast cancer stem cells. |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BRAFi | BRAF inhibitor. |

| BRCA1/2 | Breast cancer gene 1/2 |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CAR-T | Chimeric artificial T cell receptors |

| CB-103 | Non-gamma-secretase inhibitor |

| CD44 | Cell Surface Glycoprotein CD44 |

| CD133 | Transmembrane glycoprotein CD133 |

| CREKA | Pentapeptide lineal biologically active compound |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CSCs | cancer stem cells |

| CSL | CBF1/Suppressor of Hairless/LAG-1, also known as RBP-Jκ |

| DAPT | GSI-IX |

| DLK1 | Delta like homolog 1. |

| DLK2 | Delta like homolog 2. |

| DLL1 | Canonical Delta-Like1 ligand. |

| DLL3 | Canonical Delta-Like3 ligand. |

| DLL4 | Canonical Delta-Like4 ligand. |

| DOS | Delta and OSM-11 Motif. |

| DTP | Drug-tolerant persisted cells |

| DSL | Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 domain |

| DT | Desmoid tumors |

| DUSP1 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor. |

| EGFR | |

| EMT | Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. |

| EPBCm | Estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| ErbB-4 | EGFR subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| ERKi | ERK MAPK inhibitor. |

| EVO | Evodiamine. |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| GC | Gastric cancer. |

| GCSCs | Gastric cancer stem cells. |

| GSC | γ-Secretase complex |

| GSI | γ-Secretase inhibitor. |

| Hes1 | Hairy and enhancer of split-1 |

| HEY | Hes related family BHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IGF-1R | Receptor of growth factor similar to insulin 1. |

| JAG1 | Canonical Jagged 1 ligand. |

| JAG2 | Canonical Jagged 2 ligand. |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat Sarcoma |

| LCSCs | Lung cancer stem cells. |

| mAb | monoclonal antibodies |

| MAML | Mastermind-like protein. |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MEK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 1 (MAP2K1) |

| MEKi | MEK inhibitor. |

| MET | Mesenchymal Epithelial Transition receptor tyrosine kinase |

| METi | MET inhibitor. |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| MTD | maximum tolerated dose |

| MSC | Melanoma stem cells. |

| NECD | NOTCH extracellular domain |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor enhancing kappa light chains of activated B cells |

| NICD | NOTCH intracellular domain. |

| NRR | Negative regulatory region. |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer. |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. |

| PEST | proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine domain |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PFS | Progression-free survival. |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| RBP-Jκ | Recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region |

| RECK | Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs. |

| RT | Radiotherapy. |

| SAHA | Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. |

| SOX2 | SRY-related HMG-box 2 |

| SS | Sulindac sulfide. |

| TACE | Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-converting enzyme |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TMD | transmembrane domain. |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer. |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR1 | Receptor of vascular endothelial growth factor 1 |

| WNT | Wingless and Int-1. |

| 2D | Two dimensions. |

| 3D | Three dimensions. |

| WHO | World Health Organization. |

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer 2025; Available from: https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-topics/.

- World Health Organization. 2025; Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1.

- Aster, J.C., W.S. Pear, and S.C. Blacklow, The Varied Roles of Notch in Cancer. Annu Rev Pathol, 2017. 12: p. 245-275. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. and J.C. Aster, Notch signaling in cancer: Complexity and challenges on the path to clinical translation. Semin Cancer Biol, 2022. 85: p. 95-106. [CrossRef]

- Guo, M., et al., Notch signaling, hypoxia, and cancer. Front Oncol, 2023. 13: p. 1078768. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B., et al., Notch signaling pathway: architecture, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2022. 7(1): p. 95. [CrossRef]

- Siebel, C. and U. Lendahl, Notch Signaling in Development, Tissue Homeostasis, and Disease. Physiol Rev, 2017. 97(4): p. 1235-1294. [CrossRef]

- Kopan, R. and M.X. Ilagan, The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell, 2009. 137(2): p. 216-33. [CrossRef]

- Bray, S., Notch. Curr Biol, 2000. 10(12): p. R433-5.

- Bray, S. and M. Furriols, Notch pathway: making sense of suppressor of hairless. Curr Biol, 2001. 11(6): p. R217-21. [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.J., Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2006. 7(9): p. 678-89. [CrossRef]

- Zamfirescu, A.M., A.S. Yatsenko, and H.R. Shcherbata, Notch signaling sculpts the stem cell niche. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 1027222. [CrossRef]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., M.D. Rand, and R.J. Lake, Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science, 1999. 284(5415): p. 770-6.

- Weinmaster, G., Notch signal transduction: a real rip and more. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2000. 10(4): p. 363-9. [CrossRef]

- Mumm, J.S. and R. Kopan, Notch signaling: from the outside in. Dev Biol, 2000. 228(2): p. 151-65.

- Lai, E.C., Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate. Development, 2004. 131(5): p. 965-73. [CrossRef]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. and M.A. Muskavitch, Notch: the past, the present, and the future. Curr Top Dev Biol, 2010. 92: p. 1-29.

- DEXTER, J.S., The Analysis of a Case of Continuous Variation in Drosophila by a Study of Its Linkage Relations. The American Naturalist, 1914. 48: p. 712-758. [CrossRef]

- Blaumueller, C.M., et al., Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane. Cell, 1997. 90(2): p. 281-91. [CrossRef]

- Logeat, F., et al., The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998. 95(14): p. 8108-12. [CrossRef]

- Czerwonka, A., J. Kalafut, and M. Nees, Modulation of Notch Signaling by Small-Molecular Compounds and Its Potential in Anticancer Studies. Cancers (Basel), 2023. 15(18). [CrossRef]

- Tsaouli, G., et al., Molecular Mechanisms of Notch Signaling in Lymphoid Cell Lineages Development: NF-kappaB and Beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2020. 1227: p. 145-164.

- Lopez-Lopez, S., et al., NOTCH3 signaling is essential for NF-kappaB activation in TLR-activated macrophages. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 14839. [CrossRef]

- Lubman, O.Y., et al., Quantitative dissection of the Notch:CSL interaction: insights into the Notch-mediated transcriptional switch. J Mol Biol, 2007. 365(3): p. 577-89. [CrossRef]

- Kopan, R., et al., Signal transduction by activated mNotch: importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1996. 93(4): p. 1683-8. [CrossRef]

- Kopan, R. and R. Cagan, Notch on the cutting edge. Trends Genet, 1997. 13(12): p. 465-7. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, L.T., et al., Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev, 2000. 14(11): p. 1343-52.

- D’Souza, B., L. Meloty-Kapella, and G. Weinmaster, Canonical and non-canonical Notch ligands. Curr Top Dev Biol, 2010. 92: p. 73-129.

- D’Souza, B., A. Miyamoto, and G. Weinmaster, The many facets of Notch ligands. Oncogene, 2008. 27(38): p. 5148-67. [CrossRef]

- Hozumi, K., Distinctive properties of the interactions between Notch and Notch ligands. Dev Growth Differ, 2020. 62(1): p. 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Kuintzle, R., L.A. Santat, and M.B. Elowitz, Diversity in Notch ligand-receptor signaling interactions. bioRxiv, 2024.

- Laborda, J., et al., dlk, a putative mammalian homeotic gene differentially expressed in small cell lung carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor cell line. J Biol Chem, 1993. 268(6): p. 3817-20. [CrossRef]

- Baladron, V., et al., dlk acts as a negative regulator of Notch1 activation through interactions with specific EGF-like repeats. Experimental Cell Research, 2005. 303(2): p. 343-359. [CrossRef]

- Nueda, M.L., et al., The novel gene EGFL9/Dlk2, highly homologous to Dlk1, functions as a modulator of adipogenesis. J Mol Biol, 2007. 367(5): p. 1270-80. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Solana, B., et al., The EGF-like proteins DLK1 and DLK2 function as inhibitory non-canonical ligands of NOTCH1 receptor that modulate each other’s activities. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2011. 1813(6): p. 1153-64. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L., et al., dlk, pG2 and Pref-1 mRNAs encode similar proteins belonging to the EGF-like superfamily. Identification of polymorphic variants of this RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1995. 1261(2): p. 223-32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Pref-1 , a preadipocyte secreted factor that inhibits adipogenesis J Nutr, 2006. 136: p. 2953-2956.

- Smas, C., L. Chen, and H. Sul, Cleavage of membrane-associated pref-1 generates a soluble inhibitor of adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol, 1997. 17: p. 977-988. [CrossRef]

- Smas, C.M., D. Green, and H.S. Sul, Structural characterization and alternate splicing of the gene encoding the preadipocyte EGF-like protein pref-1. Biochemistry, 1994. 33(31): p. 9257-65. [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, J.F.H., et al., The role of delta-like non-canonical Notch ligand 1 (DLK1) in cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2021. 28(12): p. R271-R287. [CrossRef]

- Nueda, M.L., et al., DLK proteins modulate NOTCH signaling to influence a brown or white 3T3-L1 adipocyte fate. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 16923. [CrossRef]

- Yevtodiyenko, A. and J.V. Schmidt, Dlk1 expression marks developing endothelium and sites of branching morphogenesis in the mouse embryo and placenta. Dev Dyn, 2006. 235(4): p. 1115-23. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gallastegi, P., et al., Similarities and differences in tissue distribution of DLK1 and DLK2 during E16.5 mouse embryogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol, 2019. 152(1): p. 47-60. [CrossRef]

- Barrick, D. and R. Kopan, The Notch transcription activation complex makes its move. Cell, 2006. 124(5): p. 883-5. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, P.F., et al., Targeting the Notch Signaling Pathway in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 668207. [CrossRef]

- Miele, L., Notch signaling. Clin Cancer Res, 2006. 12(4): p. 1074-9.

- Mumm, J.S., et al., A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell, 2000. 5(2): p. 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Brou, C., et al., A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell, 2000. 5(2): p. 207-16.

- Lai, E.C., Notch cleavage: Nicastrin helps Presenilin make the final cut. Curr Biol, 2002. 12(6): p. R200-2. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.S., Substrate recognition and processing by gamma-secretase. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr, 2020. 1862(1): p. 183016. [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, W.T., et al., Notch and the amyloid precursor protein are cleaved by similar gamma-secretase(s). Biochemistry, 2003. 42(1): p. 137-44.

- Wong, E., G.R. Frost, and Y.M. Li, gamma-Secretase Modulatory Proteins: The Guiding Hand Behind the Running Scissors. Front Aging Neurosci, 2020. 12: p. 614690. [CrossRef]

- Schroeter, E.H., J.A. Kisslinger, and R. Kopan, Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature, 1998. 393(6683): p. 382-6. [CrossRef]

- Previs, R.A., et al., Molecular pathways: translational and therapeutic implications of the Notch signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2015. 21(5): p. 955-61. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M. and M. Katoh, Precision medicine for human cancers with Notch signaling dysregulation (Review). Int J Mol Med, 2020. 45(2): p. 279-297.

- Bernasconi-Elias, P., et al., Characterization of activating mutations of NOTCH3 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and anti-leukemic activity of NOTCH3 inhibitory antibodies. Oncogene, 2016. 35(47): p. 6077-6086. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K., et al., Notch3 signaling promotes colorectal tumor growth by enhancing immunosuppressive cells infiltration in the microenvironment. BMC Cancer, 2023. 23(1): p. 55. [CrossRef]

- Aster, J.C. and S.C. Blacklow, Targeting the Notch pathway: twists and turns on the road to rational therapeutics. J Clin Oncol, 2012. 30(19): p. 2418-20. [CrossRef]

- Chimento, A., et al., Notch Signaling in Breast Tumor Microenvironment as Mediator of Drug Resistance. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(11). [CrossRef]

- Gallahan, D. and R. Callahan, The mouse mammary tumor associated gene INT3 is a unique member of the NOTCH gene family (NOTCH4). Oncogene, 1997. 14(16): p. 1883-90. [CrossRef]

- Demitrack, E.S. and L.C. Samuelson, Notch as a Driver of Gastric Epithelial Cell Proliferation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017. 3(3): p. 323-330.

- Gupta, S., P. Kumar, and B.C. Das, HPV: Molecular pathways and targets. Curr Probl Cancer, 2018. 42(2): p. 161-174. [CrossRef]

- Cook, N., et al., Gamma secretase inhibition promotes hypoxic necrosis in mouse pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Exp Med, 2012. 209(3): p. 437-44. [CrossRef]

- Grochowski, C.M., K.M. Loomes, and N.B. Spinner, Jagged1 (JAG1): Structure, expression, and disease associations. Gene, 2015. 576(1 Pt 3): p. 381-4. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, E.S. and A. Pietras, Emerging Roles of DLK1 in the Stem Cell Niche and Cancer Stemness. J Histochem Cytochem, 2022. 70(1): p. 17-28. [CrossRef]

- Nueda, M.-L., et al., The proteins DLK1 and DLK2 modulate NOTCH1-dependent proliferation and oncogenic potential of human SK-MEL-2 melanoma cells. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Cell Research, 2014. 1843(11): p. 2674-2684. [CrossRef]

- Nueda, M.L., et al., Different expression levels of DLK1 inversely modulate the oncogenic potential of human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through inhibition of NOTCH1 signaling. FASEB J, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, A.I., et al., Different Expression Levels of DLK2 Inhibit NOTCH Signaling and Inversely Modulate MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Tumor Growth In Vivo. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(3). [CrossRef]

- Lundkvist, J. and J. Naslund, Gamma-secretase: a complex target for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2007. 7(1): p. 112-8.

- Moore, G., et al., Top Notch Targeting Strategies in Cancer: A Detailed Overview of Recent Insights and Current Perspectives. Cells, 2020. 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Groth, C. and M.E. Fortini, Therapeutic approaches to modulating Notch signaling: current challenges and future prospects. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2012. 23(4): p. 465-72. [CrossRef]

- Panelos, J., et al., Expression of Notch-1 and alteration of the E-cadherin/beta-catenin cell adhesion complex are observed in primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma (Merkel cell carcinoma). Mod Pathol, 2009. 22(7): p. 959-68. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al., The gamma-secretase complex: from structure to function. Front Cell Neurosci, 2014. 8: p. 427.

- Wolfe, M.S., Structure and Function of the gamma-Secretase Complex. Biochemistry, 2019. 58(27): p. 2953-2966.

- Kimberly, W.T. and M.S. Wolfe, Identity and function of gamma-secretase. J Neurosci Res, 2003. 74(3): p. 353-60.

- Hur, J.Y., gamma-Secretase in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Mol Med, 2022. 54(4): p. 433-446.

- Mekala, S., G. Nelson, and Y.M. Li, Recent developments of small molecule gamma-secretase modulators for Alzheimer’s disease. RSC Med Chem, 2020. 11(9): p. 1003-1022.

- Song, C., et al., The critical role of gamma-secretase and its inhibitors in cancer and cancer therapeutics. Int J Biol Sci, 2023. 19(16): p. 5089-5103. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Nieva, P., et al., More Insights on the Use of gamma-Secretase Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Oncologist, 2021. 26(2): p. e298-e305. [CrossRef]

- McCaw, T.R., et al., Gamma Secretase Inhibitors in Cancer: A Current Perspective on Clinical Performance. Oncologist, 2021. 26(4): p. e608-e621. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari-Movahed, M., et al., Unlocking the Secrets of Cancer Stem Cells with gamma-Secretase Inhibitors: A Novel Anticancer Strategy. Molecules, 2021. 26(4). [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y., et al., gamma-Secretase inhibitors in cancer clinical trials are pharmacologically and functionally distinct. EMBO Mol Med, 2017. 9(7): p. 950-966. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021. 372: p. n71.

- Avila, J.L. and J.L. Kissil, Notch signaling in pancreatic cancer: oncogene or tumor suppressor? Trends Mol Med, 2013. 19(5): p. 320-7. [CrossRef]

- Samore, W.R. and C.S. Gondi, Brief overview of selected approaches in targeting pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 2014. 23(6): p. 793-807. [CrossRef]

- Yabuuchi, S., et al., Notch signaling pathway targeted therapy suppresses tumor progression and metastatic spread in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett, 2013. 335(1): p. 41-51.

- Mizuma, M., et al., The gamma secretase inhibitor MRK-003 attenuates pancreatic cancer growth in preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther, 2012. 11(9): p. 1999-2009. [CrossRef]

- Palagani, V., et al., Combined inhibition of Notch and JAK/STAT is superior to monotherapies and impairs pancreatic cancer progression. Carcinogenesis, 2014. 35(4): p. 859-66. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.C.M., et al., Tumor-stromal cross-talk modulating the therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2018. 17(5): p. 461-472. [CrossRef]

- Gounder, M., et al., Nirogacestat, a gamma-Secretase Inhibitor for Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med, 2023. 388(10): p. 898-912. [CrossRef]

- Cook, N., et al., A phase I trial of the gamma-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer, 2018. 118(6): p. 793-801. [CrossRef]

- De Jesus-Acosta, A., et al., A phase II study of the gamma secretase inhibitor RO4929097 in patients with previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs, 2014. 32(4): p. 739-45.

- Zhang, Y., et al., NOTCH1 Signaling Regulates Self-Renewal and Platinum Chemoresistance of Cancer Stem-like Cells in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res, 2017. 77(11): p. 3082-3091.

- Morgan, K.M., et al., Gamma Secretase Inhibition by BMS-906024 Enhances Efficacy of Paclitaxel in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther, 2017. 16(12): p. 2759-2769. [CrossRef]

- Sosa Iglesias, V., et al., Synergistic Effects of NOTCH/gamma-Secretase Inhibition and Standard of Care Treatment Modalities in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Front Oncol, 2018. 8: p. 460. [CrossRef]

- Maraver, A., et al., Therapeutic effect of gamma-secretase inhibition in KrasG12V-driven non-small cell lung carcinoma by derepression of DUSP1 and inhibition of ERK. Cancer Cell, 2012. 22(2): p. 222-34. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.P., et al., Cisplatin selects for multidrug-resistant CD133+ cells in lung adenocarcinoma by activating Notch signaling. Cancer Res, 2013. 73(1): p. 406-16.

- Xie, M., et al., gamma Secretase inhibitor BMS-708163 reverses resistance to EGFR inhibitor via the PI3K/Akt pathway in lung cancer. J Cell Biochem, 2015. 116(6): p. 1019-27. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H., et al., Notch pathway regulates osimertinib drug-tolerant persistence in EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci, 2023. 114(4): p. 1635-1650.

- Pine, S.R., Rethinking Gamma-secretase Inhibitors for Treatment of Non-small-Cell Lung Cancer: Is Notch the Target? Clin Cancer Res, 2018. 24(24): p. 6136-6141.

- Mizugaki, H., et al., gamma-Secretase inhibitor enhances antitumour effect of radiation in Notch-expressing lung cancer. Br J Cancer, 2012. 106(12): p. 1953-9. [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara-Konishi, J., et al., Combined antitumor effect of gamma-secretase inhibitor and ABT-737 in Notch-expressing non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol, 2017. 22(2): p. 257-268. [CrossRef]

- He, F., et al., Synergistic Effect of Notch-3-Specific Inhibition and Paclitaxel in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Cells Via Activation of The Intrinsic Apoptosis Pathway. Med Sci Monit, 2017. 23: p. 3760-3769. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S., et al., Multimodality Approaches to Treat Hypoxic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Microenvironment. Genes Cancer, 2012. 3(2): p. 141-51. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H., et al., Single-Cell Analysis Identifies NOTCH3-Mediated Interactions between Stromal Cells That Promote Microenvironment Remodeling and Invasion in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res, 2024. 84(9): p. 1410-1425. [CrossRef]

- Paris, D., et al., Inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth by beta and gamma-secretase inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol, 2005. 514(1): p. 1-15.

- Yang, X., et al., Evodiamine suppresses Notch3 signaling in lung tumorigenesis via direct binding to gamma-secretases. Phytomedicine, 2020. 68: p. 153176. [CrossRef]

- Witt, M., et al., On the Way to Accounting for Lung Modulation Effects in Particle Therapy of Lung Cancer Patients-A Review. Cancers (Basel), 2024. 16(21). [CrossRef]

- Demitrack, E.S., et al., NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 regulate epithelial cell proliferation in mouse and human gastric corpus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2016. 312(2): p. G133-G144. [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.J., et al., RECK inhibits stemness gene expression and tumorigenicity of gastric cancer cells by suppressing ADAM-mediated Notch1 activation. J Cell Physiol, 2014. 229(2): p. 191-201. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.C., et al., Gastric tumor-initiating CD44(+) cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition are inhibited by gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Oncol Lett, 2015. 10(5): p. 3293-3299. [CrossRef]

- Barat, S., et al., Gamma-Secretase Inhibitor IX (GSI) Impairs Concomitant Activation of Notch and wnt-beta-catenin Pathways in CD44+ Gastric Cancer Stem Cells. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J., et al., Activation of nuclear PTEN by inhibition of Notch signaling induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in gastric cancer. Oncogene, 2015. 35(2): p. 251-60. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W., et al., Targeting Notch signaling by gamma-secretase inhibitor I enhances the cytotoxic effect of 5-FU in gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2015. 32(6): p. 593-603. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J., et al., Combination treatment of PD98059 and DAPT in gastric cancer through induction of apoptosis and downregulation of WNT/beta-catenin. Cancer Biol Ther, 2013. 14(9): p. 833-9. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., et al., Concurrent Treatment with Anti-DLL4 Enhances Antitumor and Proapoptotic Efficacy of a gamma-Secretase Inhibitor in Gastric Cancer. Transl Oncol, 2018. 11(3): p. 599-608. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D., et al., Notch1-MAPK Signaling Axis Regulates CD133(+) Cancer Stem Cell-Mediated Melanoma Growth and Angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol, 2016. 136(12): p. 2462-2474. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G., et al., Combination with gamma-secretase inhibitor prolongs treatment efficacy of BRAF inhibitor in BRAF-mutated melanoma cells. Cancer Lett. 376(1): p. 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, L., et al., BRAF(V600E;K601Q) metastatic melanoma patient-derived organoids and docking analysis to predict the response to targeted therapy. Pharmacol Res, 2022. 182: p. 106323. [CrossRef]

- Krepler, C., et al., Targeting Notch enhances the efficacy of ERK inhibitors in BRAF-V600E melanoma. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(44): p. 71211-71222. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N., et al., Combining a GSI and BCL-2 inhibitor to overcome melanoma’s resistance to current treatments. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(51): p. 84594-84607. [CrossRef]

- Keyghobadi, F., et al., Long-Term Inhibition of Notch in A-375 Melanoma Cells Enhances Tumor Growth Through the Enhancement of AXIN1, CSNK2A3, and CEBPA2 as Intermediate Genes in Wnt and Notch Pathways. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 531. [CrossRef]

- Skarmoutsou, E., et al., FOXP3 expression is modulated by TGF-beta1/NOTCH1 pathway in human melanoma. Int J Mol Med, 2018. 42(1): p. 392-404.

- Tolcher, A.W., et al., Phase I study of RO4929097, a gamma secretase inhibitor of Notch signaling, in patients with refractory metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol, 2012. 30(19): p. 2348-53. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M., et al., Phase 2 study of RO4929097, a gamma-secretase inhibitor, in metastatic melanoma: SWOG 0933. Cancer, 2015. 121(3): p. 432-440. [CrossRef]

- Thippu Jayaprakash, K., et al., In Vitro Evaluation of Notch Inhibition to Enhance Efficacy of Radiation Therapy in Melanoma. Adv Radiat Oncol, 2021. 6(2): p. 100622. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, D.J., et al., Triple negative breast cancer initiating cell subsets differ in functional and molecular characteristics and in gamma-secretase inhibitor drug responses. EMBO Mol Med, 2013. 5(10): p. 1502-22. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., et al., Signaling pathway inhibitors target breast cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol Rep, 2019. 41(1): p. 437-446. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X., et al., pH sensitive peptide functionalized nanoparticles for co-delivery of erlotinib and DAPT to restrict the progress of triple negative breast cancer. Drug Deliv, 2019. 26(1): p. 470-480. [CrossRef]

- Stoeck, A., et al., Discovery of biomarkers predictive of GSI response in triple-negative breast cancer and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cancer Discov, 2014. 4(10): p. 1154-67.

- Zhang, S., et al., Targeting Met and Notch in the Lfng-deficient, Met-amplified triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther, 2014. 15(5): p. 633-42. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L., et al., Gamma secretase inhibitor enhances sensitivity to doxorubicin in MDA-MB-231 cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2015. 8(5): p. 4378-87.

- Paroni, G., et al., Retinoic Acid Sensitivity of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells Characterized by Constitutive Activation of the notch1 Pathway: The Role of Rarbeta. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Sen, P. and S.S. Ghosh, gamma-Secretase Inhibitor Potentiates the Activity of Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid by Inhibiting Its Ability to Induce Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Stemness via Notch Pathway Activation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci, 2023. 6(10): p. 1396-1415. [CrossRef]

- Sen, P., T. Kandasamy, and S.S. Ghosh, Multi-targeting TACE/ADAM17 and gamma-secretase of notch signalling pathway in TNBC via drug repurposing approach using Lomitapide. Cell Signal, 2023. 102: p. 110529. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F., et al., Sulindac sulfide as a non-immune suppressive gamma-secretase modulator to target triple-negative breast cancer. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1244159. [CrossRef]

- Vigolo, M., et al., The Efficacy of CB-103, a First-in-Class Transcriptional Notch Inhibitor, in Preclinical Models of Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2023. 15(15). [CrossRef]

- Fournier, M., et al., Reciprocal inhibition of NOTCH and SOX2 shapes tumor cell plasticity and therapeutic escape in triple-negative breast cancer. EMBO Mol Med, 2024. 16(12): p. 3184-3217. [CrossRef]

- Schott, A.F., et al., Preclinical and clinical studies of gamma secretase inhibitors with docetaxel on human breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 2013. 19(6): p. 1512-24.

- Locatelli, M.A., et al., Phase I study of the gamma secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 in combination with docetaxel in patients with advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(2): p. 2320-2328. [CrossRef]

- Sardesai, S., et al., A phase I study of an oral selective gamma secretase (GS) inhibitor RO4929097 in combination with neoadjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin in triple negative breast cancer. Invest New Drugs, 2020. 38(5): p. 1400-1410. [CrossRef]

- Means-Powell, J.A., et al., A Phase Ib Dose Escalation Trial of RO4929097 (a gamma-secretase inhibitor) in Combination with Exemestane in Patients with ER + Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC). Clin Breast Cancer, 2022. 22(2): p. 103-114. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A., et al., Development and Application of a Novel Model System to Study “Active” and “Passive” Tumor Targeting. Mol Cancer Ther, 2016. 15(10): p. 2541-2550.

- Sen, P. and S.S. Ghosh, The Intricate Notch Signaling Dynamics in Therapeutic Realms of Cancer. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci, 2023. 6(5): p. 651-670. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y., et al., Combination therapy with epigenetic-targeted and chemotherapeutic drugs delivered by nanoparticles to enhance the chemotherapy response and overcome resistance by breast cancer stem cells. J Control Release, 2015. 205: p. 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., et al., DT7 peptide-modified lecithin nanoparticles co-loaded with gamma-secretase inhibitor and dexamethasone efficiently inhibit T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and reduce gastrointestinal toxicity. Cancer Lett, 2022. 533: p. 215608. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C., T. Zheng, and B.P. Hubbard, CRISPR/Cas technologies for cancer drug discovery and treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2025. 46(5): p. 437-452. [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, S.K. and D. Schramek, In vivo CRISPR screens reveal potent driver mutations in head and neck cancers. Mol Cell Oncol, 2020. 7(4): p. 1758541. [CrossRef]

- Tedder, B. and M. Bhutani, Resistance Mechanisms to BCMA Targeting Bispecific Antibodies and CAR T-Cell Therapies in Multiple Myeloma. Cells, 2025. 14(14). [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.J., et al., gamma-Secretase inhibitor in combination with BCMA chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy for individuals with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a phase 1, first-in-human trial. Lancet Oncol, 2023. 24(7): p. 811-822. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., et al., Bispecific antibodies targeting EGFR/Notch enhance the response to talazoparib by decreasing tumour-initiating cell frequency. Theranostics, 2023. 13(11): p. 3641-3654. [CrossRef]

- Feng, M., et al., Inhibition of gamma-secretase/Notch pathway as a potential therapy for reversing cancer drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol, 2024. 220: p. 115991. [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, E., et al., Effect of DAPT, a gamma secretase inhibitor, on tumor angiogenesis in control mice. Adv Biomed Res, 2014. 2: p. 83. [CrossRef]

- Tansir, G., S. Rastogi, and M.M. Gounder, Repurposing nirogacestat, a gamma secretase enzyme inhibitor in desmoid tumors. Future Oncol, 2025. 21(23): p. 2985-2993. [CrossRef]

- Federman, N., Molecular pathogenesis of desmoid tumor and the role of gamma-secretase inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol, 2022. 6(1): p. 62. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C., et al., The Notch signaling pathway in desmoid tumor: Recent advances and the therapeutic prospects. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2024. 1870(1): p. 166907. [CrossRef]

- He, W., et al., High tumor levels of IL6 and IL8 abrogate preclinical efficacy of the gamma-secretase inhibitor, RO4929097. Mol Oncol, 2011. 5(3): p. 292-301. [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, S., et al., Immune checkpoint inhibitors and Carbon iON radiotherapy In solid Cancers with stable disease (ICONIC). Future Oncol, 2023. 19(3): p. 193-203. [CrossRef]

| GSI | Type of cancer | Type of study | Main results | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRK003 | PDAC | In vivo (xenograft) +/- gemcitabine | The combination blocked tumor progression | [63], [87] | |

| TNBC | In vitro e in vivo + placitaxel |

Greater antitumor activity of the combination in cells with higher NICD levels | [130] | ||

| NSCLC | In vivo + erlotinib | Induced cell death in hypoxic tumors and decreased metastasis to the liver and brain. Prolonged median survival in mice. | [104] | ||

| Mesenchymal cells and 9 treatment-naïve patients | Reduced collagen production and suppressed invasive behavior. | [105] | |||

| GSI-IX | PDAC | In vivo (xenograft) + AG-490 |

Mice treated with the combination showed no visible tumors | [88] | |

| In vitro and in a xenograft mouse model | Reduced the growth of pancreatic tumor-initiating CD44+/EpCAM+ cells | [80] | |||

| GC | In vitro, in CD44+ cells | Smaller tumor spheres and increased apoptosis | [112] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) | Reduced tumor growth and increased necrosis | ||||

| NSCLC | In vitro + paclitaxel | Synergistic antitumor effect by modulating the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and enhancing cell death. Reduced NOTCH3–induced chemoresistance in a concentration-dependent manner | [103] | ||

| Metastatic melanoma | In vitro | GSI decreased CD133+ cells (MSCs) | [117] | ||

| GSI-X | |||||

| PF-03084014 (Nirogacestat) | PDAC | In vivo (xenograft) +/- gemcitabine |

Only in combination did it show antiproliferative activity and reduce cancer stem cells | [86] | |

| Metastatic melanoma | In vitro + MEKi | The combination was more effective in stopping proliferation and migration | [119] | ||

| DAPT | PDAC | In vitro | CAF monocultures hardly responded to DAPT which suggested that CAFs are more resistant to standard chemo-treatments than the epithelial cancer cells. High levels of IL-6 were also associated with a reduced response to therapy | [89] | |

| NSCLC | In vitro + cisplatin | Decrease in the appearance of CD133+, ALDH+ LCSC cells, with lower resistance to cisplatin | [97] | ||

| KrasG12V-driven NSCLC | GSI treatment upregulated DUSP1, leading to reduced phospho-ERK levels | [96] | |||

| In vitro and lung adenocarcinoma tumors xenotransplanted into nude mice. | Reduced endothelial cell proliferation, suppressed the formation of capillary structures, opposed the sprouting of microvessel outgrowths and potently inhibit the growth and vascularization | [106] | |||

| GC | In vitro | Inhibited the formation of GCSC-rich spheres by 25% | [110] | ||

| In vitro, in CD44+ and CD44- cells | CD44+ cells, behaving as GCSCs, showed greater antitumor response to GSI. Enhanced sensitivity to 5-FU | [111] | |||

| In vivo (xenograft) | Significant inhibition of tumor growth and EMT | ||||

| In vitro +/- PD98059 In vivo (xenograft) +/- PD98059 |

Reduced tumor growth and increased apoptosis in combination | [115] | |||

| In vitro +/- anti-DLL4 | Significant increase in apoptosis and reduced invasion and tumor size | [116] | |||

| Metastatic melanoma | In vivo (xenograft) +/- BRAFi |

Reversal of melanoma cell resistance to BRAFi | [118] | ||

| DAPT | Metastatic melanoma | In vitro +/- DLK1 and/or DLK2 levels |

Dose-dependent effect of DAPT: decreased proliferation at high doses, increased at low doses. The combination reduced cell proliferation | [66] | |

| In vitro e In vivo (Xenograft) | Long-term use of DAPT increased tumor growth | [122] | |||

| TNBC | In vitro, in BCSCs cells | Reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis | [128] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) | Delay in tumor formation and reduced subsequent growth | ||||

| Nanoparticles carrying the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT In vivo (xenograft) + Erlotinib + Director peptide |

The nanoparticle reduced tumor growth and cell migration | [129] | |||

| In vitro + ATRA | The combination was more effective in inhibiting tumor growth | [133] | |||

| GSI-34 | NSCLC | In vivo (xenograft) with CD166+Lin- LCSC cells +/- cisplatin |

CD166+Lin- showed intrinsic resistance to cisplatin, which was reversed with GSI. The combination effectively reduced tumor size | [93] | |

| BMS-708163 | In vitro, in NSCLC-gefitinb resistant cells + gefitinib |

High doses of GSI reversed resistance to gefitinib and formed smaller colonies | [98] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) + gefitinib |

The combination produced considerable inhibition of tumor growth | ||||

| BMS-906024 | In vitro, in NSCLC cells + RT +/- placitaxel y crizotinib |

Monotherapy + RT did not show significant reduction. It was observed with the combination | [95] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) + placitaxel |

The combination enhanced the cytotoxic effect of paclitaxel | [94,100] | |||

| GSI-XX | In vivo (xenograft) + RT |

The combination caused a significant delay in tumor growth | [101] | ||

| In vitro and in vivo experiments + osimertinib | Impaired drug-tolerant persistence, suppressed phospho-ERK, and enhanced DUSP1 expression. | [99] | |||

| In vitro and in vivo +ABT-737 |

Treatment with either agent and in combination inhibit cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner and regulated the expression of apoptosis proteins. | [102] | |||

| GSI-I | In vitro + RT | Higher level of apoptosis than isolated RT | [101] | ||

| GC | In vitro and in vivo (xenograft) + placitaxel or 5-FU |

Increased activity of PTEN, a tumor suppressor gene. Both combinations were more effective than monotherapy |

[113], [114] | ||

| Metastatic melanoma | In vivo (xenofraft) and in vitro + BCL2i |

The combination was more effective than monotherapy | [121] | ||

| RO4929097 | In vitro + ERKi | Sensitization to ERKi in cell lines that did not respond to it in monotherapy | [120] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) +ERKi | The combination was more effective than monotherapy | ||||

| In vitro + RT | Synergism at low doses in combination | [126] | |||

| TNBC | In vitro, in CD24 low and CD24- (BCSCs) cells | Inhibition of CD24low sphere growth | [127] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) with CD24 low and CD24- (BCSCs) cells | Halted tumor growth and metastasis in CD24 low models | ||||

| MK-0752 | In vitro. Different levels of NOTCH expression + METi |

The combination showed synergism in halting cell growth | [131] | ||

| In vivo (xenograft) | Injecting BCSC cells treated with GSI did not reproduce the tumor | [139] | |||

| LY411575 | In vitro + SAHA | SAHA in monotherapy was seen to promote EMT. The combination reduced EMT and increased apoptosis | [134] | ||

|

LY3039478 (Crenigacestat) |

TNBC | TNBC xenografts + Paclitaxel + Dasatinib | Tumor growth and metastasis reduction | [138] | |

|

OTHERS (Evodiamine) |

NSCLC | In vitro | Not a GSI but behaves like one. It reduced cell proliferation and metastasis | [107] | |

|

OTHERS (NSAID sulindac (SS)) |

TNBC | In vitro, in vivo and ex vivo | Significantly inhibited nanosphere growth in all human and murine TNBC models. Eliminated NOTCH1 protein expression in tumors |

[136] | |

|

OTHERS (CB103, a pan-Notch inhibitor) |

Endocrine-resistant BC xenografts | When combined with SERDs or CDK inhibitors in endocrine-resistant recurrent breast cancers, and with taxane-based chemotherapy in TNBC, CB-103 produced synergistic effects boosting paclitaxel’s impact | [137] | ||

|

OTHERS (Lomitapide) |

In vitro | Multi-targeting TACE/ADAM17 and gamma-secretase complex of NOTCH signaling pathway | [135] |

| Type of cancer | GSI | Phase | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDAC | MK-0752 + gemcitabine |

I | 14 out of 44 patients reached a stable condition, in both monotherapy and combination therapy. Gastrointestinal disorders and anemia were observed. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01098344. | [91] |

| RO4929097 | II | The trial could not be completed because GSI synthesis was discontinued. Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01232829 | [92] | |

| Metastatic melanoma | RO4929097 |

I | In two groups of 110 patients, 33% and 41% reached a stable condition. Hypophosphatemia was noted. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) | [124] |

| II | Of 32 evaluated patients, 1 had a partial response and 8 reached a stable condition. Hypophosphatemia was also observed, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01120275 | [125] | ||

| TNBC | MK-0752 + docetaxel |

I | Among 24 patients, 11 had a partial response, 9 reached a stable condition, and 3 showed tumor progression. There was one case of severe pneumonitis. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00645333 | [139] |

| PF-03084014 + docetaxel |

I | 29 women showed limited treatment efficacy, with severe hematologic and infectious reactions. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01876251 | [140] | |

| RO4929097 + placitaxel + carboplatin |

I | Of 14 evaluated patients, 5 had a partial response, 4 reached a stable condition, and 5 had residual disease. Neutropenia was reported (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocol). | [141] | |

| EPBCm | RO4929097 + exemestane |

Ib | Among 14 evaluated patients, 7 had a partial response and 7 reached a stable condition, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01149356 | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).