Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

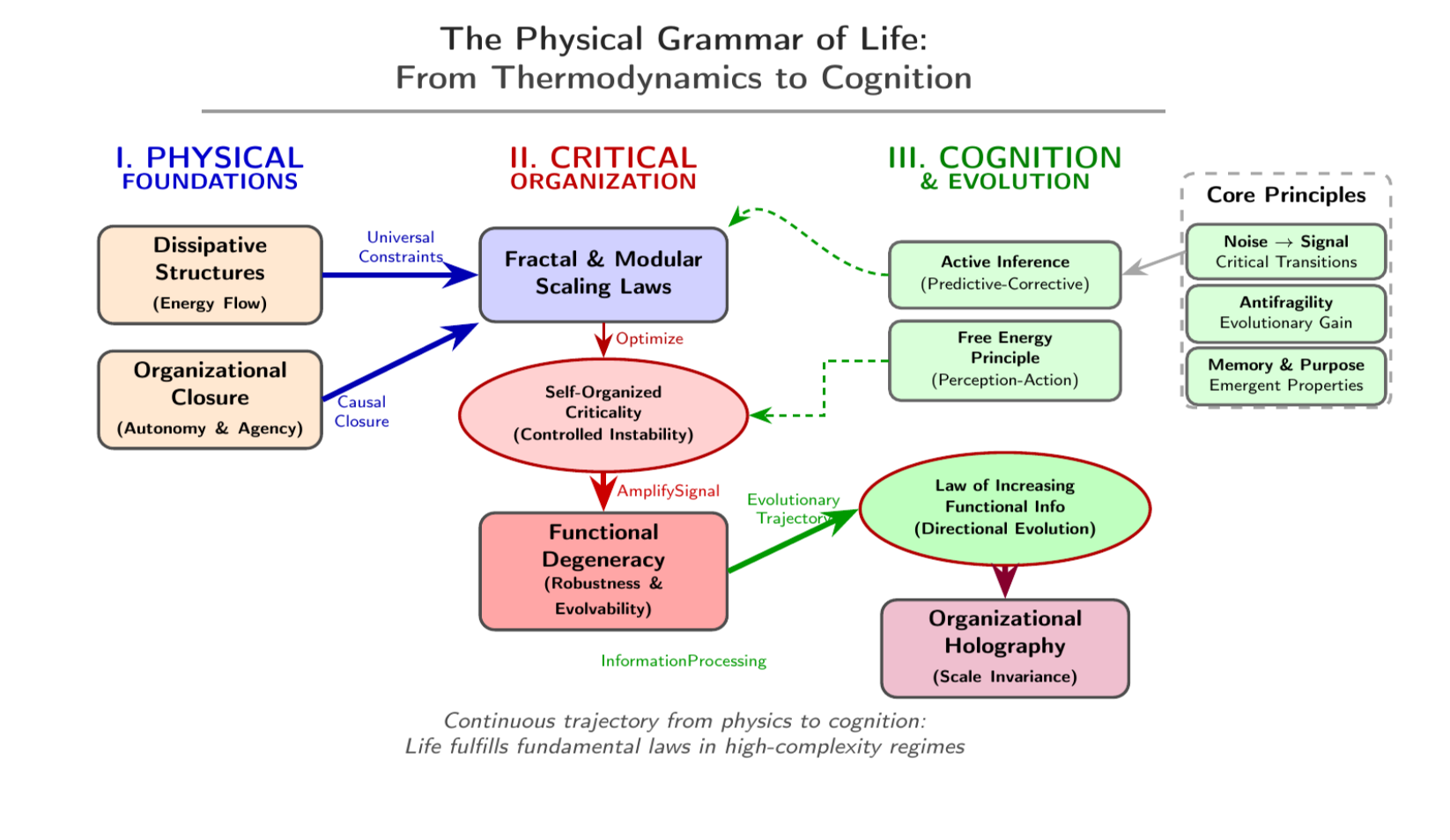

Introduction

Results

State of the Art and Main Formal Models

Thermodynamic Foundation: Dissipation, Instability, and Organization

Logic of Self-Fabrication: Organizational Closure and Autonomy

Universal Organizational Principles

Autopoiesis, (M,R) Systems, and Autocatalytic Sets

Fractality and Modularity

Criticality

Distributed Cognition

Antifragility and Degeneracy

Law of Increasing Functional Information (LIFC)

Conceptual Synthesis and Structural Analogies: The Holographic View

The Immune System: Autonomy, Fractality, and Distributed Cognition

The Brain: Criticality, Modularity, and Informational Efficiency

The Microbiome: Critical Ecological Network and Co-autonomy

Tissues: Self-organization and Morphodynamic Patterns

Ecosystems and Biosphere: Critical Flow Networks and Resilience

Organizational Holography: A Universal Grammar of Life At All Scales, Life Obeys a Universal Organizational Grammar

Falsifiable Predictions, Controversies, Limits, and Experimental Projections

Controversies and Limits

Falsifiable Predictions

Conceptual Integration and Interdisciplinary Applications

Precision Medicine and Dynamic Pathophysiology

Bioengineering, Synthetic Biology, and the Design of Life

Artificial Intelligence, Cognition, and Complex Systems

Towards a Technobiological Synthesis

Discussion

Critical Conclusions and Prospects for a Physics of Life

Epistemological Implications

Future Scientific Agenda

Towards a Physics of Creative Order

Limitations of the Study

Resource Availability

Materials Availability

- This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

-

This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. All data and theoretical models discussed are available from the cited references.

- This paper does not report original code.

- Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Declaration Of Interests

Declaration Of Generative Ai And Ai-Assisted Technologies

References

- Woese, C.R. (2004). A New Biology for a New Century. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68, 173–186. [CrossRef]

- Goldenfeld, N., and Woese, C. (2011). Life is Physics: Evolution as a Collective Phenomenon Far From Equilibrium. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2, 375–399. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I., and Nicolis, G. (1985). Self-Organisation in Nonequilibrium Systems: Towards A Dynamics of Complexity. In Bifurcation Analysis, M. Hazewinkel, R. Jurkovich, and J. H. P. Paelinck, eds. (Springer Netherlands), pp. 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. (1952). The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 237, 37–72. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D., Aon, M.A., and Cortassa, S. (2001). Why Homeodynamics, Not Homeostasis? The Scientific World JOURNAL 1, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.R., and Varela, F.J. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: the realization of the living (D. Reidel Publishing).

- Rosen, R. (1991). Life itself: a comprehensive inquiry into the nature, origin, and fabrication of life (Columbia University Press).

- Varela, F.J. (1981). Describing the logic of the living: The adequacy and limitations of the idea of autopoiesis. In Autopoiesis: A theory of living organization, pp. 36–48.

- Kauffman, S.A. (1993). The origins of order: self-organization and selection in evolution (Oxford University Press).

- West, G.B., Brown, J.H., and Enquist, B.J. (2007). A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science 276, 122–126. [CrossRef]

- West, G.B., and Brown, J.H. (2000). The origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. In Scaling in biology (Oxford University Press), pp. 87–112.

- Fleischaker, G.R. (1988). Autopoiesis: the status of its system logic. Biosystems 22, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Ravasz, E., Somera, A.L., Mongru, D.A., Oltvai, Z.N., and Barabási, A.-L. (2002). Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks. Science 297, 1551–1555. [CrossRef]

- Bak, P., Tang, C., and Wiesenfeld, K. (1987). Self-organized criticality: an explanation of 1/f noise. Physical Review Letters 59, 381–384. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.A. (2018). Colloquium: Criticality and dynamical scaling in living systems. Reviews of Modern Physics 90, 031001. [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, Y. (1984). Chemical oscillations, waves, and turbulence (Springer-Verlag).

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N.N. (2012). Antifragile: things that gain from disorder (Random House).

- Edelman, G.M., and Gally, J.A. (2001). Degeneracy and complexity in biological systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 13763–13768. [CrossRef]

- Hazen, R.M., Grew, E.S., Downs, R.T., Golden, J., and Hystad, G. (2023). On the roles of function and selection in evolving systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, e2310223120. [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, O., and Schneider, E.D. (1998). The thermodynamics and evolution of complexity in biological systems. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 120, 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. (2020). Answering Schrödinger’s “What Is Life?” Entropy 22, 815. [CrossRef]

- Kondepudi, D.K., De Bari, B., and Dixon, J.A. (2020). Dissipative structures, organisms and evolution. Entropy 22, 1305. [CrossRef]

- Painter, K.J., Hunt, G.S., Wells, K.L., Johansson, J.A., and Headon, D.J. (2012). Towards an integrated experimental-theoretical approach for assessing the mechanistic basis of hair and feather morphogenesis. Interface Focus 2, 433–450. [CrossRef]

- Mossio, M. (2024). Introduction: Organization as a Scientific Blind Spot. In Organization in Biology History, Philosophy and Theory of the Life Sciences., M. Mossio, ed. (Springer International Publishing), pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Jureček, M., and Švorcová, J. (2025). Flowing boundaries in autopoietic systems and microniche construction. BioSystems 254, 105477. [CrossRef]

- Hordijk, W., Kauffman, S.A., and Steel, M. (2011). Required Levels of Catalysis for Emergence of Autocatalytic Sets in Models of Chemical Reaction Systems. IJMS 12, 3085–3101. [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M., and Frieden, B.R. (2021). Autopoiesis and Its Efficacy—A Metacybernetic View. Systems 9, 75. [CrossRef]

- Huitzil, S., and Huepe, C. (2024). Life’s building blocks: the modular path to multiscale complexity. Front Syst Biol 4, 1417800. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H., and Payton, D.W. (2018). Optimization by Self-Organized Criticality. Sci Rep 8, 2358. [CrossRef]

- Shojaie, A., Jauhiainen, A., Kallitsis, M., and Michailidis, G. (2014). Inferring Regulatory Networks by Combining Perturbation Screens and Steady State Gene Expression Profiles. PLOS ONE 9, e82393. [CrossRef]

- Nourisa, J. and others (2025). geneRNIB: a living benchmark for gene regulatory network inference. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.B., Torday, J.S., and Baluška, F. (2020). The N-space Episenome unifies cellular information space-time within cognition-based evolution. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 150, 112–139. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.E., and Turley, S.J. (2015). Stromal infrastructure of the lymph node and coordination of immunity. Trends in Immunology 36, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Bahl, A., Pandey, S., Rakshit, R., Kant, S., and Tripathi, D. (2025). Infection-induced trained immunity: a twist in paradigm of innate host defense and generation of immunological memory. Infect Immun 93, e00472-24. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S., Haobijam, D., Malik, Md.Z., Ishrat, R., and Singh, R.K.B. (2018). Fractal rules in brain networks: Signatures of self-organization. Journal of Theoretical Biology 437, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Heiney, K., Huse Ramstad, O., Fiskum, V., Christiansen, N., Sandvig, A., Nichele, S., and Sandvig, I. (2021). Criticality, Connectivity, and Neural Disorder: A Multifaceted Approach to Neural Computation. Front Comput Neurosci 15, 611183. [CrossRef]

- Berg, G., Rybakova, D., Fischer, D., Cernava, T., Vergès, M.-C.C., Charles, T., Chen, X., Cocolin, L., Eversole, K., Corral, G.H., et al. (2020). Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 8, 103. [CrossRef]

- Baruah, G., and Lakämper, T. (2024). Stability, resilience and eco-evolutionary feedbacks of mutualistic networks to rising temperature. Journal of Animal Ecology 93, 989–1002. [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C., Olson, C.A., and Hsiao, E.Y. (2017). Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci 20, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is life? The physical aspect of the living cell (Cambridge University Press).

- Nguyen, L.L., and D’Amore, P.A. (2001). Cellular interactions in vascular growth and differentiation. In International Review of Cytology (Elsevier), pp. 1–48. [CrossRef]

- Lane, P.A., and Paulin, N. (2025). The Reality of Constraint and the Illusion of Control in Ecological Networks. Preprint at Computer Science and Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Equihua, M., Espinosa Aldama, M., Gershenson, C., López-Corona, O., Munguía, M., Pérez-Maqueo, O., and Ramírez-Carrillo, E. (2020). Ecosystem antifragility: beyond integrity and resilience. PeerJ 8, e8533. [CrossRef]

- Goenner, H.F.M. (2014). On the History of Unified Field Theories. Part II. (ca. 1930–ca. 1965). Living Rev. Relativ. 17, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gintis, H. (2007). A framework for the unification of the behavioral sciences. Behav Brain Sci 30, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.C., Jeynes, C., and Walker, S.D. (2025). A Metric for the Entropic Purpose of a System. Entropy 27, 131. [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, G., Ferrari, U., Battaglia, F.P., Cocco, S., and Monasson, R. (2017). Functional coupling networks inferred from prefrontal cortex activity show experience-related effective plasticity. Network Neuroscience 1, 275–301. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, S. (2023). Cartography of the multiple formal systems of molecular autopoiesis: from the biology of cognition and enaction to anticipation and active inference. Biosystems 230, 104955. [CrossRef]

- Solé, R., Kempes, C., and Stepney, S. (2025). Origins of life: the possible and the actual. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 380, 20240281. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, Y.I., Katsnelson, M.I., and Koonin, E.V. (2018). Physical foundations of biological complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115. [CrossRef]

- Toro-Domínguez, D., and Alarcón-Riquelme, M.E. (2021). Precision medicine in autoimmune diseases: fact or fiction. Rheumatology 60, 3977–3985. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, N., and Levin, M. (2024). Bio-inspired AI: Integrating Biological Complexity into Artificial Intelligence. Preprint at arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, A. (2024). Science of science: A multidisciplinary field studying science. Heliyon 10, e36066. [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, R.F. (2016). Applied and Computational Mathematics Division: Summary of Activities for Fiscal Year 2015 (National Institute of Standards and Technology). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).