1. Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) can be defined as a state where abnormal high levels of insulin are needed to produce a normal response in target tissues [

1,

2]. According to Konstantinos N. Aronis and Christos S. Mantzoros [

3] who have extensively studied this topic, IR was first identified by Rosalyn S. Yalow and Solomon A. Berson in 1960. These authors, using a new method to measure insulin, found that individuals with late-onset diabetes mellitus had elevated insulin levels [

1,

2]. The next breakthrough came when it was discovered that in rodents, high insulin levels due to IR were associated with abnormal insulin binding to its receptor [

4,

5]. In 1976, the first evidence that defects in the insulin receptor could lead to IR in humans provided further confirmation of the significance of IR in human health [

6]. In 1988, Gerald M. Reaven proposed that IR was the underlying factor in the modern concept of metabolic syndrome, which includes high blood pressure, abnormal blood sugar levels, and unhealthy cholesterol levels [

7].

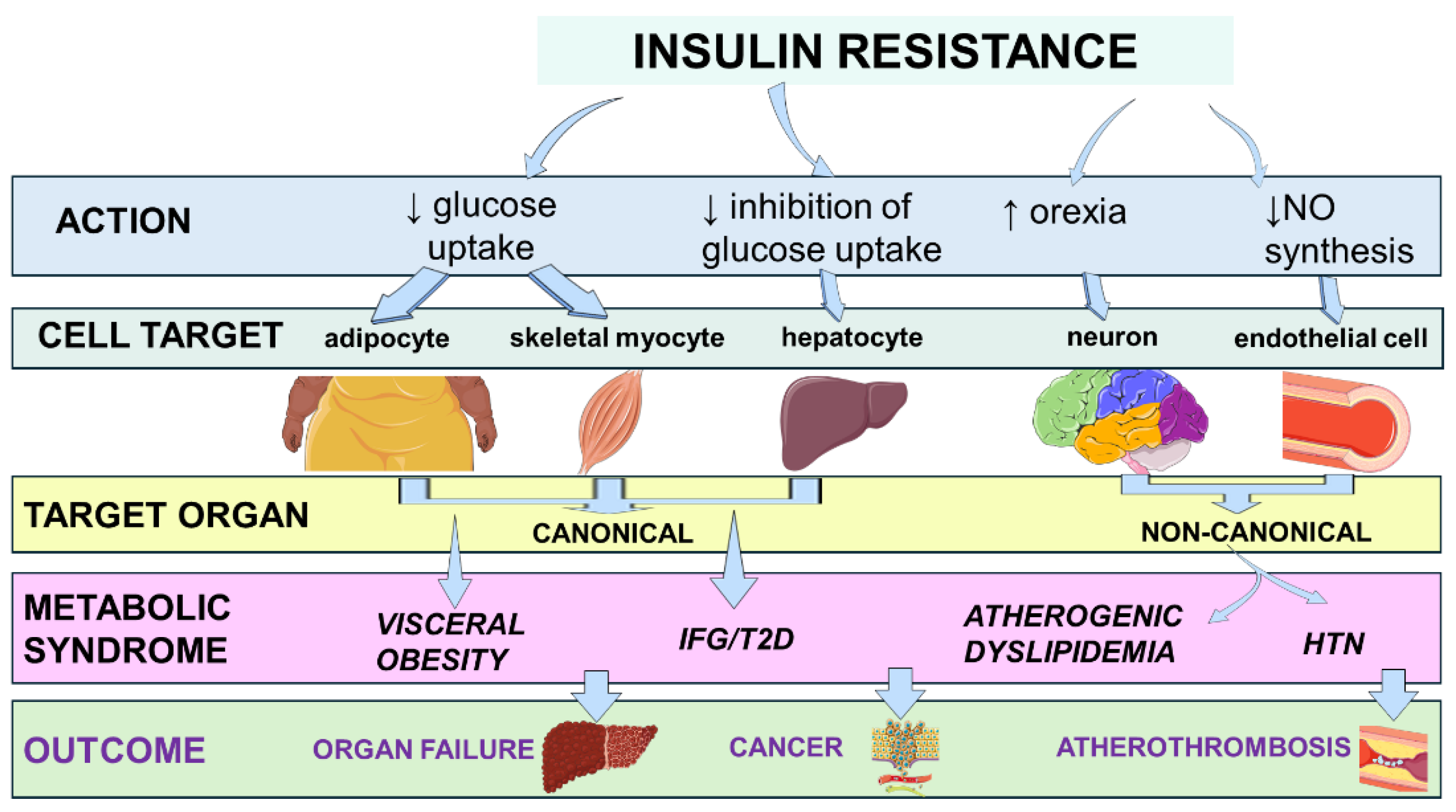

Figure 1 illustrates the link between IR and clinical outcomes through the metabolic syndrome [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Over the past few decades, research has expanded the understanding of IR beyond type 2 diabetes (T2D) and metabolic syndrome. It now highlights that IR plays a crucial role as a strategic intersection among various seemingly unrelated conditions. Complex pathophysiological systemic mechanisms, such as cell stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic subclinical low-grade inflammation, often exacerbated by factors like obesity, are intricately linked with IR. This, in turn, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), organ failure, and cancer by triggering a vicious cycle where each metabolic dysfunction worsens and perpetuates other features of the metabolic syndrome over time [

14,

15,

16,

17].

IR, a modern epidemic reflecting a complex interplay between lifestyle habits, and psycho-social determinants, imposes a significant financial burden. This is mainly due to the increased rates of T2D, CVDs, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [

18,

19,

20]. The ongoing need for treatment drives up healthcare costs and results in productivity losses, impacting individuals, businesses, and the economy. Moreover, IR associated with obesity has serious social implications, including stigma and discrimination, which can significantly affect mental health and reinforce socio-economic disparities [

19].

With this background, the present review synthesizes current knowledge on the molecular pathogenesis of IR, elucidates its role in metaflammation and the progression to CVD, organ failure, and cancer. We also propose a translational agenda aimed at improving prevention and treatment strategies.

2. Research Strategy

Following the objectives outlined in the Introduction, we conducted a comprehensive narrative literature search in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus for articles published up to October 2025. We used key terms such as “insulin resistance,” “metaflammation,” “metabolic syndrome,” “type 2 diabetes,” “cardiovascular disease,” “organ failure,” and “cancer” to guide our search. Additionally, we searched reference lists of important articles to identify any additional relevant studies. Our priority was to include original research, large cohort studies, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and authoritative reviews written in English. We also considered studies focusing on pediatric populations, gestational diabetes, or rare monogenic disorders, if they provided insights that could be applied to adult metabolic diseases. We carefully screened titles, abstracts, and full texts of selected studies. Information regarding study design, population characteristics, molecular findings, clinical outcomes, and therapeutic implications was extracted. This information was then qualitatively synthesized to provide an integrative overview that informs the subsequent sections of this review.

3. Etiology and Assessment of Insulin Resistance

3.1. Causes of Insulin Resistance

There are numerous causes that can eventually lead to the development of IR. Genetic forms of IR include myotonic dystrophy, ataxia-telangiectasia, Alstrom syndrome, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, Werner syndrome, lipodystrophy, type-A IR caused by abnormalities of the insulin receptor gene, which can result in abnormal glucose homeostasis, ovarian virilization, and acanthosis nigricans, and type-B IR triggered by insulin receptor autoantibodies leading to altered glucose homeostasis, ovarian-type hyperandrogenism, and acanthosis nigricans [

21].

Table 1 summarizes the acquired forms of IR.

3.2. Assessment of Insulin Resistance in Clinics and in Epidemiological Studies

In clinical practice, IR should be suspected in individuals with a family history of T2D, especially if objective findings indicate an enlarged waist circumference, arterial hypertension, or acanthosis nigricans [

28]. Another clinical clue to IR is the presence of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [

29]. PCOS may be suspected in young women based on altered menses, hyperandrogenism and ultrasonographic evidence of polycystic ovaries [

30].

The simplest laboratory test to reveal IR is assessing fasting plasma glucose [

31], and elevated fasting glycemia may be an early and inexpensive biomarker of IR, particularly when associated with concomitant compensatory fasting hyperinsulinemia [

32]. Although the significance of post-prandial hyperglycemia is widely acknowledged in the context of diabetes, its impact in non-diabetic subjects is poorly defined [

33]. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), while used primarily to diagnose glucose intolerance, by measuring blood glucose and insulin levels at intervals after a glucose oral load, can offer insights into glucose tolerance and insulin dynamics [

34].

The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is calculated using fasting triglycerides and fasting blood glucose according to the formula

ln(

triglycerides x glucose/2/

triglycerides×

glucose/2) and is a simple, cost-effective, and reliable surrogate bio marker in the diagnosis of IR [

35]. Although it is correlated with standard measures such as the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) [

36] and is also used to assess cardiometabolic risk [

37]. Its accuracy and optimal cutoff values vary depending on age, race, and sex. A study based on more than 2,000 hypertriglyceridemic adults has suggested a single cutoff point of 4.5 to classify individuals with IR [

38]. The HOMA-IR is a widely used simple surrogate index of IR that does not involve a log transformation and is simply calculated as the product of fasting insulin and glucose [

39]. A Korean study enrolling 10,997 participants found that the cut-off values of the HOMA-IR were 2.20 in men, 2.55 in premenopausal women, and 2.03 in postmenopausal women [

40].

The Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index (QUICKI) is another simple index that uses fasting glucose and insulin levels, differing from HOMA-IR. QUICKI uses a mathematical transformation, specifically the inverse of the sum of the logarithms of fasting insulin and glucose [

41].

3.3. Assessment of Insulin Resistance in the Diabetes Research Setting

The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, considered the gold standard in research involves infusing insulin to suppress glucose production in the liver while simultaneously infusing a glucose solution to keep blood glucose levels stable and normal [

42]. The rate of glucose infusion needed to maintain this stability during the clamp provides a precise measurement of insulin sensitivity [

42].

Compared to the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, the insulin tolerance test (IST) is a simpler yet highly accurate research-based test to determine IR [

43]. The IST involves the intravenous infusion of glucose while monitoring its disappearance over time until it returns to fasting levels in order to estimate insulin sensitivity [

31].

4. Molecular Physiology of Insulin Signaling and Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance

4.1. Inter-Organ Crosstalk: Hepatokines, Myokines, and Adipokines

Insulin action begins with receptor autophosphorylation, IRS engagement, PI3K activation, and downstream Akt-mediated effects that promote glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, lipogenesis, and protein translation [

44]. While this proximal cascade is ubiquitous, its systemic outcome is sculpted by a dynamic three-way dialogue among the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. In the post-prandial state, insulin suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, stimulates glycogen storage, and drives de novo lipogenesis. However, the liver also acts as an endocrine organ, releasing hepatokines such as fetuin-A, fibroblast growth factor-21, and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) that modify insulin responsiveness in distant tissues [

45]. For example, Fetuin-A binds to the insulin receptor and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on adipocytes and myocytes, promoting serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins and thereby dampening PI3K-Akt signaling. On the other hand, FGF-21 exerts the opposite effect by enhancing fatty-acid oxidation and glucose uptake, illustrating how shifts in hepatokine balance can tip systemic insulin sensitivity in either direction.

Skeletal muscle, which ordinarily disposes of approximately 70% of meal-derived glucose, secretes myokines whose profiles depend on contractile activity. Exercise releases irisin and myonectin that augment hepatic β-oxidation and promote browning of white fat [

45,

46]. Conversely, physical inactivity elevates myostatin, which suppresses GLUT4 expression and encourages adiposity, reinforcing IR [

47]. Adipose tissue adds a third endocrine axis, in which anti-inflammatory adiponectin activates AMPK and PPAR-α in the liver and muscle to increase fatty acid combustion. However, its concentrations fall in obesity, while leptin, resistin, and visfatin rise, driving NF-κB and JNK activation in macrophages and parenchymal cells, thereby amplifying systemic IR [

48].

4.2. Lipotoxicity and the Self-Expanding Network of the Metabolic Syndrome

When caloric intake chronically exceeds oxidative needs, subcutaneous fat deposits reach their storage limit. Surplus fatty acids are then redirected to visceral fat, the liver, muscles, pancreas, heart, and kidneys, where they accumulate as diacylglycerols, ceramides, and acyl-CoAs. These substances poison insulin signaling, a process termed lipotoxicity. These lipid intermediates activate novel protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms and TLR4, leading to IKKβ- and JNK-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1/2 (IRS1/2) and uncoupling of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase [

49,

50]. This, in turn, blunts insulin-mediated glucose transport, causes endothelial dysfunction, and raises blood pressure.

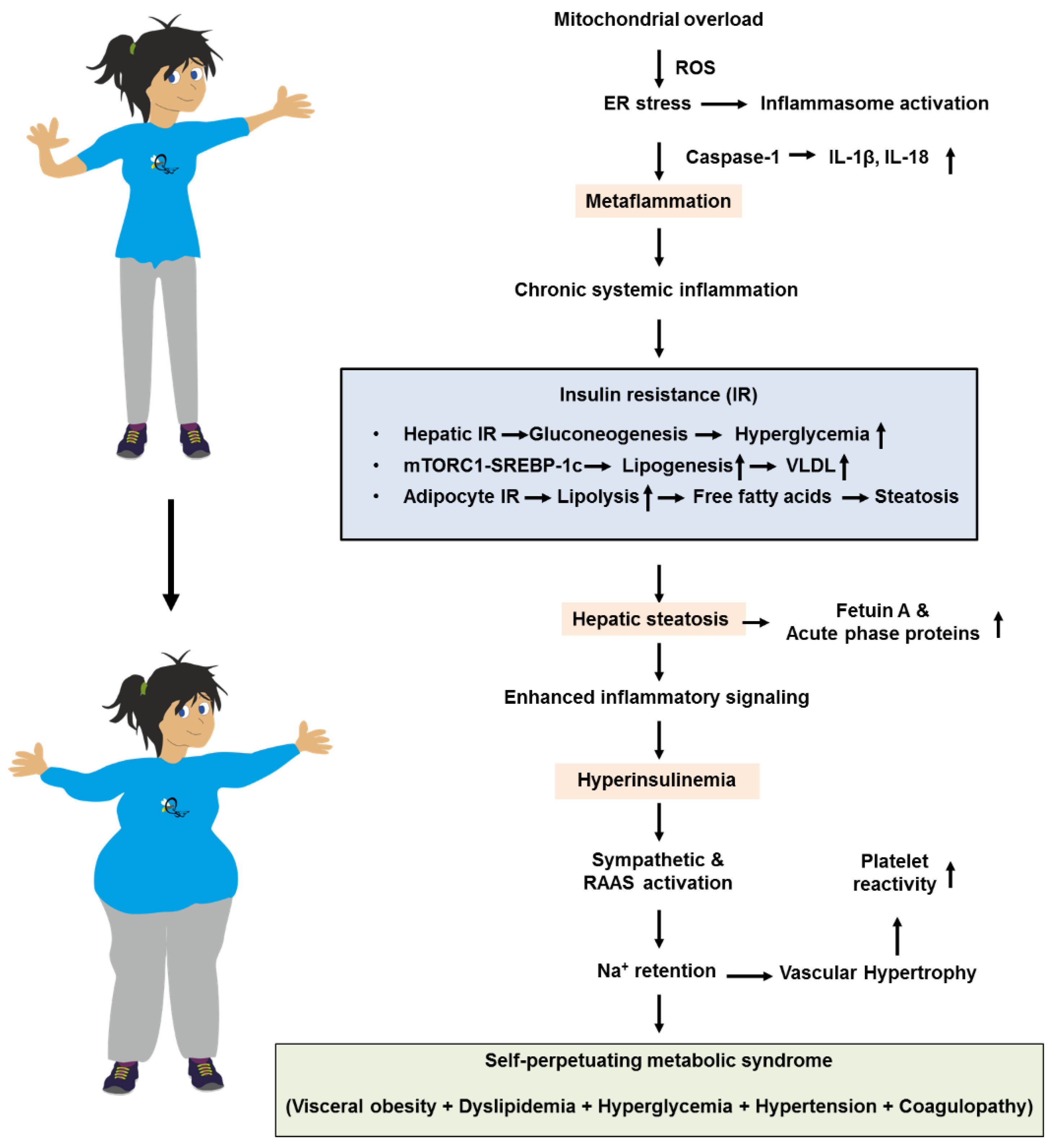

Mitochondrial overload generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that intensify ER stress and inflammasome activation. This leads to caspase-1–dependent maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, resulting in “metaflammation” that perpetuates cytokine spill-over. This creates a positive feedback loop that maintains tissues in a state of chronic IR. Selective hepatic IR further skews metabolism [

51]. While Akt inhibition allows unabated gluconeogenesis and fasting hyperglycemia, mTORC1-driven SREBP-1c activity remains relatively preserved [

52]. This sustains de novo lipogenesis and VLDL overproduction, raising plasma triglycerides, lowering HDL cholesterol via cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) exchange, and accelerating atherogenesis [

53]. Simultaneously, impaired insulin suppression of adipocyte lipolysis floods the portal circulation with free fatty acids, worsening hepatic steatosis. This fuels the production of fetuin A, ceruloplasmin, and acute-phase reactants that spread inflammatory signals. These events might trigger a cascade in which the metaflammation provokes IR, hepatic steatosis, finally ending in metabolic syndrome (

Figure 2).

Hyperinsulinemia, originally a compensatory response, exacerbates sympathetic activation and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone signaling [

54]. This drives sodium retention and vascular hypertrophy, while directly stimulating smooth-muscle proliferation and platelet reactivity. These factors integrate hypertension and pro-thrombotic risk into the metabolic-syndrome complex [

54]. Common molecular lesions, such as ectopic lipid overload, organelle stress, and inflammatory kinase activation, act as the centripetal force that clusters visceral obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and pro-coagulant states. This causes the syndrome to perpetuate and worsen progressively over time.

4.3. Drug-Induced Derailment of Insulin signaling

A variety of therapeutic agents can exacerbate IR by targeting the same molecular nodes that regulate insulin action. Glucocorticoids increase the expression of enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis (PEPCK, G6Pase), inhibit the translocation of muscle GLUT4, and promote visceral fat accumulation, leading to hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia [

55]. Calcineurin inhibitors like cyclosporine and tacrolimus hinder the dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of an activated T cell (NFAT), reducing insulin production and β-cell mass, while also decreasing muscle glucose uptake seen in post-transplant diabetes [

56,

57].

HIV protease inhibitors interfere with GLUT4 function and cause lipodystrophy, ectopic fat storage, and oxidative stress, resulting in severe IR similar to metabolic syndrome [

58,

59]. Atypical antipsychotics affect central appetite regulation through 5-HT2C and H1 blockade but also impair mitochondrial function in the liver and β-cells, disrupt AMPK signaling, increase fat production, leading to weight gain, dyslipidemia, and poor blood sugar control [

60]. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, while typically weight-neutral, can increase adrenergic activity and cortisol release, reducing insulin effectiveness. Androgen-deprivation therapy reduces muscle mass and increases visceral fat, raising the risk of diabetes in men with prostate cancer. Even high doses of exogenous insulin can down-regulate its own receptor and promote fat formation, worsening IR and requiring higher doses, known as “hyperinsulinemia-induced insulin resistance”.

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial to make informed decisions on drug selection and potentially combine with insulin-sensitizing medications like metformin, thiazolidinediones, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to mitigate iatrogenic metabolic harm while maintaining treatment effectiveness. IR arises from disrupted signaling in liver, muscle, and fat cells, exacerbated by lipotoxic and inflammatory factors that link these tissues, and exacerbated by medications targeting overlapping pathways. This understanding supports a comprehensive, tissue-specific, and drug-conscious approach to combat the complex metabolic syndrome.

5. Pathobiology and Clinical Science Associating Ethnicity Insulin Resistance, Sex and Aging

5.1. Pathobiology Associating Insulin Resistance, Ethnicity Sex and Aging

Marked heterogeneity in the prevalence and severity of IR across ethnic groups, between the sexes and over the life span reflects a mosaic of molecular differences that modulate the canonical insulin signaling cascade. Genome-wide association studies indicate that risk alleles in loci such as

TCF7L2,

PPARG,

IRS1 and

SLC16A11 are differentially distributed among populations of African, Hispanic, South-Asian and East-Asian ancestry, predisposing carriers to impaired insulin receptor substrate (IRS) phosphorylation and reduced glucose uptake at lower body-mass indices than in populations of European descent [

61]. Moreover, Asians and people of African ancestry tend to accumulate more visceral and hepatic fat and possess smaller adipocytes that reach their lipid storage threshold earlier, promoting ectopic diacylglycerol and ceramide deposition, activating novel PKC isoforms and phosphorylation of IRS1/2, thereby amplifying IR at comparatively modest degrees of obesity [

62]. Ethnic variation in adipokine profiles, such as lower adiponectin and higher resistin, visfatin and fetuin-A levels, further augments inflammatory IKKβ/JNK signaling and fuels metaflammation, providing a mechanistic explanation for the high IR burden seen in Black and Hispanic communities.

Sexual dimorphism in IR is driven chiefly by sex hormones and their influence on adipose topography, mitochondrial biology and immune tone [

63]. Estrogen activates ERα, boosts insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation and promotes subcutaneous rather than visceral fat deposition; it also enhances mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC-1α and dampens NF-κB activity, conferring pre-menopausal women relative protection against IR [

64]. Men, with higher androgen but lower estrogen exposure, exhibit larger myofiber cross-sectional areas and preferential visceral fat expansion, conditions that favor free fatty-acid flux to the liver and skeletal muscle, propagating lipotoxic inhibition of insulin signaling [

64]. After menopause, declining estrogen, rising FSH and augmented visceral adiposity converge to reduce adiponectin, elevate leptin and accentuate pro-inflammatory cytokine release, narrowing the sex gap in IR prevalence [

64]. Conversely, hyperandrogenism in women with PCOS and hypogonadism in aging men impair GLUT4 translocation and mitochondrial oxidative capacity, reinforcing IR in a hormone-specific manner.

Aging compounds these disparities through progressive sarcopenia, mitochondrial DNA damage, altered mitophagy and redistribution of fat from subcutaneous to ectopic depots [

65]. This enhances ROS generation and stimulates

NLRP3 inflammasome activity, thereby intensifying IRS serine phosphorylation and diminishing PI3K–Akt efficiency. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis and immunosenescence bias the cytokine milieu toward chronic low-grade inflammation, while epigenetic drift and telomere attrition exacerbate metabolic inflexibility, creating a milieu in which even modest genetic or hormonal vulnerabilities translate into overt IR. Thus, the intersection of ethnic/genetic background, sex hormones and age-linked cellular stress orchestrates a spectrum of molecular perturbations, including lipotoxicity, inflammatory kinase activation, and organelle dysfunction, which underlie the observed demographic gradients in IR.

5.2. Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance, Ethnicity, Sex, and Aging

IR is associated with ethnicity, sex and aging, with each factor playing a complex and interacting role. Certain ethnic groups such as Black, Hispanic individuals, and Asians, have higher rates of IR compared to non-Hispanic Whites, even at the same body weight or body mass index (BMI) [

66]. This can be linked to factors such as genetics, body fat distribution, and carbohydrate metabolism [

67].

Aging-associated worsening of the odds of IR is deemed to be due to age-related increases in adiposity [

68]. Additional factors explaining the increased risk of IR with aging include a decline in muscle mitochondrial function, and the significant increase in the metabolic syndrome in both sexes after the age of 60 [

69].

Sex differences are also significant, with pre-menopausal women generally being more insulin sensitive than men. This protection diminishes after menopause due to the decline of estrogen levels and expanded visceral adiposity [

70,

71]. Sex hormones influence insulin sensitivity differently in men and women. For example, hyperandrogenemia in women, typically observed, among individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and hypogonadism in men (which may result from aging, diabetes or cirrhosis) are both linked with IR and MASLD risk [

71].

Interestingly, indices of IR exhibit a sex-specific predictive ability, with TyG-BMI calculated as the natural logarithm (fasting triglyceride [mg/dL] * fasting glucose [

72] being the only index able to predict functional decline in women and HOMA-IR in men [

73]. These findings suggest that a cause-and-effect mutual relationship links aging and IR in a sex-specific manner.

6. Pathobiology and Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Inflammation

6.1. Pathobiology Associating Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Inflammation

Visceral adipocyte hypertrophy, hypoxia and mechanical stretch create an initial dangerous environment that recruits monocytes and converts tissue-resident M2 macrophages into pro-inflammatory M1 cells [

74], establishing the earliest focus of “metaflammation” in insulin-resistant states. Saturated fatty acids released from these stressed adipocytes ligate TLR4 on adipocytes, hepatocytes and macrophages, triggering MyD88–IRAK–IKKβ and JNK cascades that serine-phosphorylate IRS proteins, directly antagonizing PI3K-Akt signaling and propagating IR. Simultaneously, mitochondrial ROS species, ceramides and extracellular ATP activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, driving caspase-1- dependent maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, cytokines that amplify both local and systemic insulin antagonism [

75]. Lipid spill-over into the liver and skeletal muscle yields diacylglycerols and ceramides that activate novel PKC isoforms and provoke endoplasmic-reticulum stress, each feeding back into JNK/NF-κB/AP-1 transcriptional programs that sustain cytokine output while inhibiting insulin-stimulated glucose transport and glycogen synthesis. Compensatory hyperinsulinemia further fuels the loop by up-regulating SREBP-1c and ChREBP, expanding lipid stores and generating a constant supply of lipotoxic intermediates that keep innate immune sensors engaged [

76]. Adipokine imbalance adds another layer: excess leptin, resistin and visfatin potentiate Th1 polarization and macrophage activation, whereas hypoadiponectinemia removes AMPK- and PPAR-α-mediated anti-inflammatory brakes. Hepatokines such as fetuin-A synergize with saturated fatty acids to activate TLR4 [

77], and myokines like myostatin curtail insulin-sensitizing irisin release [

78], broadcasting inflammatory cues across metabolic organs. The result is a self-perpetuating, low-grade inflammatory circuit (i.e., metaflammation) that not only entrenches IR but also primes endothelial cells for dysfunction, β-cells for failure and parenchymal organs for fibrosis, thereby constituting the molecular nexus linking nutrient surplus to cardio-metabolic-hepato-renal disease.

6.2. Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Inflammation

Visceral obesity promotes chronic, low-grade subclinical sterile inflammation, often referred to as

“metaflammation” [

79]. Strong epidemiological and clinical evidence supports the idea that expanded and inflamed adipose tissue in individuals with obesity shows a shift in immune cells from anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages to pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, a pattern linked to IR [

80]. Obesity is also characterized by elevated levels of IR-inducing adipokines such as leptin, visfatin, and resistin [

80,

81]. With global obesity rates on the rise, projections indicate that by 2030, severe obesity will be most prevalent among low-income adults, Black individuals, and women, highlighting the urgent need for effective intervention strategies [

80]. In turn, IR is marked by secondary compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which can perpetuate inflammation and promote tissue damage through the accumulation of ectopic fat [

82].

The likelihood of subclinical systemic inflammation due to IR can vary, but studies consistently show a significant and positive association. For example, one study found that a higher HOMA-IR score was linked to a significantly higher likelihood of subclinical inflammation, as measured by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) among prediabetic individuals with MASLD [

83]. Another study demonstrated that elevated IR (higher HOMA-IR) increased the risk of future IR and T2D, with a combined higher risk of inflammation and IR [

84]. Overall, these studies support the idea that IR is strongly connected to systemic subclinical inflammation, suggesting that treating IR could effectively reduce the systemic inflammatory state in individuals with metabolic dysfunction.

7. Pathobiology and Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Disease

7.1. Pathobiology Associating Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Disease

IR triggers a selective impairment of the endothelial PI3K-Akt pathway, leading to decreased phosphorylation of endothelial-nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) and a significant reduction in bioavailable nitric oxide (NO), a key vasodilator and antithrombotic molecule [

85]. The parallel MAPK arm of insulin signaling remains relatively unaffected, promoting the release of endothelin-1 and the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. This shifts the vasculature towards vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and sympathetic activation, all crucial factors in the development of arterial hypertension in states of IR. The uncoupling of eNOS, caused by mitochondrial ROS and tetrahydrobiopterin depletion, transforms the enzyme from an NO generator to a superoxide producer [

86]. This amplifies oxidative stress, further reducing NO availability, leading to the stiffening of resistance arteries and an increase in systemic blood pressure.

The decreased NO levels also create a pro-atherothrombotic environment, in which reduced anti-adhesive signaling boosts the expression of endothelial VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, facilitating the migration of leukocytes [

87]. Meanwhile, impaired Akt–eNOS activity allows the pro-atherogenic NF-κB cascade to go unchecked, resulting in the secretion of inflammatory molecules like IL-6, MCP-1, and tissue factor. Hyperinsulinemia increases hepatic VLDL output and generates small, dense LDL particles that are easily oxidized. These particles, along with elevated free fatty acids and ceramides, activate TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes in macrophages, leading to foam-cell formation and unstable plaques [

88]. Platelet hyper-reactivity, caused by low NO and prostacyclin, high PAI-1, and increased thromboxane A₂ synthesis, contributes to a pro-thrombotic state that accelerates adverse cardiovascular events in individuals with IR.

In the myocardium, chronic IR reduces insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, forcing cardiomyocytes to rely on fatty acid oxidation, a process that increases mitochondrial ROS and accumulates lipotoxic intermediates, leading to glucolipotoxicity, cell apoptosis and fibrosis [

89]. Endothelial NO deficiency impairs endothelial dysfunction, coronary microvascular dilation, causing sub-endocardial hypoxia that affects diastolic relaxation and promotes the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [

90,

91]. Additionally, hyperinsulinemia activates the sympathetic nervous system and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis, resulting in concentric left-ventricular hypertrophy and extracellular-matrix deposition, changes that can progress to overt systolic dysfunction if the metabolic insult persists [

92].

Thus, through interconnected mechanisms involving eNOS dysfunction, oxidative stress, and lipotoxic-inflammatory signaling, IR intricately links arterial hypertension, atherothrombosis, and heart-failure phenotypes along a shared molecular continuum.

7.2. Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Disease

IR is a major risk factor for cardiometabolic disorders, including hypertension and atherosclerosis. Individuals living with the prototypic state of IR, namely T2D, are typically exposed to an increased risk for macrovascular complications, which represent the major cause of mortality in this population [

93]. However, effective treatment of established cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, and a procoagulant state will still leave a significant amount of residual, unexplained cardiovascular risk. This risk is contributed to by persisting IR via endothelial dysfunction, dyslipidemia, and a systemic pro-inflammatory state that promotes the buildup of plaque in arteries, increasing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) [

94].

Two seminal studies have addressed the importance of lifestyle changes in T2D: the Look AHEAD trial - a large, randomized clinical study comparing an intensive lifestyle intervention with a standard diabetes support and education control group for overweight and obese adults with T2D [

95] - and the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study, which showed that supervised exercise comprising aerobic and resistance training is more effective than standard exercise counseling alone for improving cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with T2D and the metabolic syndrome [

96]. Together, these trials demonstrate that lifestyle management notably enhances physical fitness, glycemic homeostasis assessed with HbA1c, and coronary heart disease risk factors [

93].

Glucose-lowering therapies significantly contribute to reducing cardiovascular risk in individuals with T2D [

97]. Additionally, bariatric surgery can enhance cardiovascular outcomes by promoting weight loss and reducing glycated hemoglobin levels [

98]. Lastly, a comprehensive approach to managing CVD risk factors, including addressing blood glucose levels, smoking, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure, helps lower mortality rates from MACE [

99]. Collectively, these various studies consistently show that IR is causally involved in the development and progression of CVD.

8. Pathobiology and Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Organ Failure

8.1. Pathobiology Associating Insulin Resistance and Organ Failure

Persistent IR forces pancreatic β-cells to sustain supraphysiological insulin output. Initially, this is achieved through β-cell hyperplasia, increased insulin-gene transcription, and augmented secretory granule biogenesis, mechanisms that compensate for diminished peripheral insulin action. Chronic nutrient excess, however, exposes β-cells to glucolipotoxicity [

100]. Elevated glucose boosts mitochondrial ROS, while free fatty acid influx generates toxic diacylglycerols and ceramides that activate PKCε, JNK, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways [

101,

102]. This culminates in oxidative damage, unfolded-protein response exhaustion, and ultimately apoptosis or dedifferentiation of β-cells to a non-secretory state. Lineage-tracing studies in rodents and analyses of human autopsy islets corroborate a trajectory in which initial β-cell expansion gives way to progressive mass and function loss once fasting glycaemia rises above ~5.5 mmol/L, defining the transition from compensated IR to overt T2D.

Beyond the pancreas, ectopic deposition of lipids in non-adipose tissues provides the biochemical substrate for organ dysfunction. In the liver, incomplete β-oxidation of oversupplied fatty acids yields ROS and lipid peroxides that provoke hepatocyte death and activate Kupffer cells [

103]. The ensuing secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and TGF-β stimulates stellate cell transdifferentiation and collagen deposition, driving the evolution from simple steatosis to MASH and cirrhosis. In the kidney, podocyte and proximal-tubule lipid overload induces ER stress and NLRP3-inflammasome activation, promoting mesangial expansion, glomerulosclerosis, and progressive CKD that ultimately manifests in nearly 40% of individuals with long-standing T2D. Cardiomyocytes exposed to high circulating fatty acids switch from glucose to fatty-acid oxidation, an energetically costly process that accelerates mitochondrial ROS generation and accumulates lipotoxic intermediates and DNA damage [

104]. This triggers apoptosis, interstitial fibrosis via TGF-β/SMAD signaling, and ventricular stiffening characteristics of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. In the brain, insulin-signaling defects impair neuronal glucose uptake, facilitate tau hyperphosphorylation, and reduce Aβ clearance. Microglial inflammasome activation perpetuates neuroinflammation, linking IR to cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes.

These degenerative cascades are fueled by systemic immunometabolic derangements inherent in IR. Visceral adipose expansion shifts macrophage polarity from M2 to M1, elevating TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1. These cytokines enter the circulation and impair insulin-receptor signaling in distant tissues through IKKβ- and JNK-mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS1/2. Hyperinsulinemia itself exerts pro-inflammatory effects by activating NF-κB and upregulating VCAM-1 expression, whereby adhesion of leukocytes and monocytes to the endothelium increases [

105]. Excess leptin and reduced adiponectin further skew the immune milieu toward Th1 and Th17 dominance, lowering the threshold for tissue injury. In parallel, hepatic release of fetuin-A complexes with saturated fatty acids to engage TLR4 on Kupffer cells and renal macrophages, amplifying inflammasome activation and fibrosis. Endothelial NO deficiency, secondary to selective insulin-signaling defects, enhances oxidative stress, recruits neutrophils, and facilitates platelet activation, a triad that not only accelerates atherothrombosis but also compromises organ perfusion, thereby worsening cardiac, renal, and cerebral outcomes [

90,

91].

Collectively, IR initiates a multidimensional assault. It begins with β-cell exhaustion, which erodes insulin supply. This leads to the production of lipotoxic intermediates that trigger parenchymal apoptosis and fibrogenesis, as well as chronic low-grade inflammation. This inflammation orchestrates immune cell infiltration and excess cytokines, establishing a self-reinforcing loop. Ultimately, this culminates in the failure of the pancreas, liver, kidney, heart, and brain.

8.2. Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Organ Failure

Over time, chronic inflammation and metabolic derangements closely linked to IR can result in organ damage and failure. For example, IR and chronic subclinical inflammation play crucial roles in the development of pancreatic β-cell failure and T2D [

106]. While T2D is mainly caused by decreased insulin secretion from β-cell in individuals with long-standing IR, the connection between reduced β-cell mass and dysfunction remains a topic of debate. Studies in mice using lineage tracing suggest that β-cell mass can increase to compensate for IR, sustaining insulin secretion until hyperglycemia occurs through β-cell hyperplasia and activation of various cellular mechanisms, such as islet cell trans-differentiation and dedifferentiation to a non-secretory state [

107]. This adaptive physiological hyperinsulinemia typically prevents the onset of T2D in most individuals. However, some may eventually develop overt hyperglycemia due to β-cell failure to compensate [

10]. Nonetheless, the majority of human islet data is derived from autopsy or donor samples, which limits functional insights due to the absence of in vivo profiling data [

108].

Longitudinal studies of individuals progressing to T2D demonstrate an elevation in insulin levels during both the normoglycemic and prediabetic stages. This elevation sustains near-normal glycemia despite IR, which is indicative of β cell compensation, followed by a subsequent decline as fasting glycemia exceeds the upper normal limit of 5.5 mM (β-cell failure) [

109]. Additionally, during the natural history of T2D progressive deterioration of β-cell function occurs associated with decreased β-cell mass due to cell apoptosis. This process is not invariably irreversible and may be blocked or delayed by effective disease management through lifestyle modification alone, eventually requiring insulin therapy at later stages of diabetic disease [

110].

Similarly, in the pathogenesis of T2D, long-standing IR may eventually lead to liver cirrhosis via MASLD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in individuals living with either obesity or T2D [

111,

112]. A seminal population-based cohort study totaling 11,465 adults without any evidence of liver cirrhosis at the study entry or during the first 5 years of follow-up, who were followed-up for a mean of 12.9 years showed that among individuals who did not consume alcohol, there was a strong association between obesity (adjusted hazard ratio 4.1, 95% CI 1.4–11.4) or being overweight (adjusted hazard ratio 1.93, 95% CI 0.7–5.3) and cirrhosis-related death or hospitalization [

113]. Consistent with these findings, an Australian study involving 8,631 participants demonstrated that individuals with T2D compared to those without T2D had a significantly higher prevalence of cryptogenic cirrhosis (42.4% vs. 27.3%; p<0.001), MASLD/MASH (13.8% vs. 3.4%; p<0.001), and admissions for hepatocellular carcinoma (18.0% vs. 12.2%; p<0.001). Furthermore, among patients with liver cirrhosis, those with T2D experienced a significantly greater median hospital stay (6 [range, 1–11] vs. 5 [range, 1–11] days; p<0.001), twice the rate of non-cirrhosis-related admissions (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.98–2.07), a 1.35-fold increase in cirrhosis-related admissions (IRR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.30–1.41), and markedly reduced survival rates (p<0.001) [

114].

Similarly, the strain posed by obesity on renal function can lead to kidney failure. A meta-analysis of 21 articles totaling 3,504,303 individuals (521,216 with obesity) followed up for an average of 9.86 years found that the relative risk of obese people developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) was 1.81 (95%CI: 1.52-2.16) indicating that living with obesity carries a 1.81 times higher risk of developing CKD than the non-obese population [

115]. Another meta-analysis of 20 studies totaling 1,711,926 participants found that around 40% of those living with T2D will develop CKD, with the risk increasing in parallel with the duration of the diabetic disease [

116]. The presence of MASLD, common among individuals with diabesity, is considered an independent risk factor for developing CKD [

117,

118].

Additional examples of IR eventually leading to target organ damage include Alzheimer’s disease [

119], MACE and heart failure [

120,

121]. Interestingly, fibrosing MASLD could be an intermediate step associating IR and target organ damage in both cases [

122,

123]. In summary, strong evidence demonstrates that IR is a major determinant of organ failure across a range of clinical manifestations spanning dementia to cardiovascular and hepatorenal health, with MASLD playing a significant role in mediating the pathomechanics of target organ dysfunction.

9. Pathobiology and Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Cancer

9.1. Pathobiology Associating Insulin Resistance and Cancer

Hyperinsulinemia, secondary to IR, is a ‘silent killer’ that leads to chronically elevated levels of circulating insulin and C-peptide [

124]. This drives the over-activation of the insulin receptor-A (IR-A) and hybrid IR/IGF-1 receptors, which strongly couple to the mitogenic MAPK and mTOR–S6K axes [

125,

126]. This stimulation results in uncontrolled cellular proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, creating an environment in which neoplastic clones can easily expand. At the same time, high insulin suppresses the hepatic synthesis of SHBG, leading to increased levels of free estradiol and testosterone [

127]. These unbound hormones act on estrogen or androgen receptors in breast, ovarian, endometrial, and prostate tissues, promoting cell cycle progression and genomic instability. This explains the sexual dimorphism observed in obesity- and diabetes-related cancers.

IR-driven lipotoxicity further fuels oncogenesis by causing the ectopic accumulation of saturated fatty acids, diacylglycerols, and ceramides. This activates PKC, NF-κB, and JNK, enhancing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6. These cytokines create a tumor-permissive micro-environment rich in ROS and growth factors, inducing DNA damage, epigenetic reprogramming, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [

128]. This fosters both the initiation and invasion of malignant cells. Chronic activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 stimulate angiogenesis via VEGF up-regulation, providing tumors with the vascular support needed for expansion and metastasis.

Dysregulation of adipokines adds another oncogenic layer. Elevated leptin enhances JAK-STAT3 and PI3K-Akt signaling in neoplastic cells, promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis. On the other hand, hypoadiponectinemia removes AMPK-mediated restraints on mTOR and ERK pathways, tipping the balance toward tumor growth. Hepatic steatosis, a hallmark of MASLD, increases the secretion of pro-oncogenic hepatokines such as fetuin-A and angiopoietin-like protein 8 (ANGPTL8), often in complex with ANGPTL3 or ANGPTL4 [

129,

130]. Together with insulin-induced FGF-2 and PDGF release, these potentiate systemic insulin-like and angiogenic signals that accelerate hepatocarcinogenesis and may nurture distant metastases.

Finally, IR-associated immune perturbations, characterized by predominance of M1 macrophages, Th17 skewing, and cytotoxic T-cell exhaustion, create an immunosuppressive environment that enables early tumors to avoid detection by the immune system [

131]. This combination of factors, including hyperinsulinemia, imbalance of adipokines, lipotoxic-inflammatory stress, hormonal disruptions, and immune evasion, forms a self-reinforcing oncogenic cycle. This positions IR as a key molecular driver of cancer development, advancement, and spread to various organs.

9.2. Clinical Science Associating Insulin Resistance and Cancer

IR is linked to an increased risk of several types of cancer, including breast, liver, pancreatic, and colon cancer through insulin acting as a growth factor. In association with insulin-resistance-related subclinical systemic inflammation, it can stimulate the growth and proliferation of cancer cells [

132].

A seminal population-based case-control study conducted in 21,022 incident cases of 19 types of cancer and 5,039 controls examined the association between obesity and the risks of various cancers [

133]. Data have shown that obesity explained 7.7% of all cancers in Canada, 9.7% in men and 5.9% in women. Compared to non-obese controls those with a BMI ≥30 kg/m

2 exhibited a higher risk of overall cancer [multivariable adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.34, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.22, 1.48), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (OR=1.46, 95% CI: 1.24, 1.72), leukemia (OR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.32, 1.96), multiple myeloma (OR=2.06, 95% CI: 1.46, 2.89), and cancers of the kidney (OR=2.74, 95% CI: 2.30, 3.25), colon (OR=1.93, 95% CI: 1.61, 2.31), rectum (OR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.36, 2.00), pancreas (OR=1.51, 95% CI: 1.19, 1.92), breast among postmenopausal women (OR=1.66, 95% CI: 1.33, 2.06), ovary (OR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.44, 2.64), and prostate (OR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.47).

Similarly, a recent nationwide study conducted in Hungary found that T2D was associated with a higher risk of cancer [

134]. The OR for overall cancer incidence among individuals with diabetes compared to non-diabetic controls was 2.50 (95% CI 2.46–2.55, p<0.0001) with risks being significantly higher in males than in females [OR

males: 2.76 (2.70–2.82) vs. OR

females: 2.27 (2.22–2.33), p< 0.05 for male-to-female comparison].

Solid evidence indicates that MASLD plays an independent role in mediating these increased risks among individuals with conditions predisposing to IR [

135,

136,

137,

138,

139].

Taken collectively, observational studies strongly support the theory that IR, as observed among individuals living with obesity and/or T2D, predisposes to the risk of cancer across various organ systems, with MASLD acting as a connecting ring in this chain of events.

10. Principles of Treatment of Insulin Resistance

Given that (visceral) adipose tissue plays a key role in determining IR, it is expected that loss of body weight, regardless of how it is achieved, will invariably be followed by restored insulin sensitivity. Confirming this prediction, weight loss obtained through lifestyle changes or bariatric surgery is consistently associated with improved insulin sensitivity [

140,

141]. This improved insulin sensitivity can be so significant that it leads to T2D reversal or remission in a considerable number of individuals after metabolic surgeries such as sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass, which alter the anatomy and physiology of the upper digestive tract by restricting food intake and affecting calorie homeostasis [

142,

143]. However, bariatric and metabolic surgeries are invasive, carry risks of complications and long-term side effects [

144].

Obesity-related IR can also be reduced with drugs. Metformin, the most commonly used drug treatment for decreasing IR in individuals with prediabetes, obesity, diabetes, and PCOS, increases peripheral glucose utilization by inducing glucose transporter 4 expression and its increased translocation to the plasma membrane [

145]. Additionally, Metformin has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and improves lipid profiles [

10]. Despite around 150 million people globally being treated with metformin, a drug that has been recommended as first-line therapy for T2D since 2009 due to its effective glucose-lowering activity, safety, and affordability, the exact mechanisms of action and critical targets of this drug remain incompletely defined [

10,

145]. Among the limitations of this drug, it is worth noting that metformin does not reduce cancer incidence in individuals with high BMI and/or altered glucose metabolism [

146], nor does it improve liver histology in MASH [

147].

Thiazolidinediones are considered the only true insulin-sensitizing antidiabetic drugs. One drug in this class, pioglitazone, has been shown to reduce cardiovascular events and slow the atherosclerotic process in high-risk patients with T2D [

94]. By targeting nuclear receptors, this class of drugs improves the utilization of insulin in target organs, ultimately leading to an increased response to insulin and decreased levels of glycemia, triglycerides and free fatty acids in the blood [

148]. However, some side effects associated with thiazolidinediones, such as fluid retention, weight gain, and an increased risk of fractures, make this class less suitable for elderly individuals. Other potential side effects include edema, worsening heart failure, and, in rare cases, liver toxicity and bladder cancer. More common, but less severe, side effects may include headaches, muscle pain, and upper respiratory tract infections [

148].

Semaglutide, belonging to the class of glucagon-like peptide receptor 1 agonists (GLP-1RA) inhibits food intake by acting both centrally on neuronal circuits involved in hunger and reward and peripherally by slowing gastric emptying [

149]. Semaglutide is available for weekly subcutaneous administration or daily orally [

150]. It induces an average weight loss of 11.62 kg compared to placebo, reduces waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, C-reactive protein, improves lipid profiles, offers cardiovascular benefits for patients with established atherosclerotic CVD, reduces the odds of CKD and cardiovascular mortality, may resolve MASH and positively impact mental health and quality of life [

149]. The most common adverse events are generally transient mild-to-moderate gastrointestinal complaints; hypoglycemia is more common without lifestyle intervention and weight regain will often follow semaglutide withdrawal [

149].

Resmetirom, approved as a thyroid hormone receptor-β (THR-β) agonist for fibrosing MASLD, enhances lipophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and fatty acid β-oxidation [

151]. It increases deiodinase type 1 expression, boosting local T4-to-T3 conversion while lowering inactive reverse T3 and CPT1, which supports oxidative phosphorylation, reduces ROS, and improves insulin sensitivity [

152]. The drug also demonstrates anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects by inhibiting nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), Janus kinase- signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Jak-STAT3), tumor necrosis factor-

α (TNF-α), interleukin -6 (IL-6), Kupffer cell activation, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling [

152]. Additionally, resmetirom improves lipid profiles and raises SHBG, suggesting both hepatic and broader metabolic benefits, with potential impacts on insulin sensitivity and diabetes risk that deserve further investigation [

153].

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with T2D, but their cardiovascular benefit appears to be mediated via mechanisms other than reduced IR [

94]. Additional drug agents of potential significance in combatting IR have been discussed elsewhere [

112,

154].

11. Article Highlights

Whenever supranormal insulin concentrations are required to elicit a quantitatively normal response in target tissues, IR is the underlying pathogenic defect.

IR serves as a strategic point of intersection among the trajectories of clinically heterogeneous non-communicable diseases that are a significant public health issue globally.

Organ failure (such as T2D, MASLD-cirrhosis, CKD, dementia, and heart failure), major adverse cardiovascular events, and cancer all share a common pathobiological denominator in IR.

IR is strongly associated with perturbed cellular and sub-cellular components homeostasis, eventually leading to cell death and the activation of pro-fibrogenic pathways that may result in organ failure.

Weight loss, regardless of how it is achieved, and insulin-sensitizing drugs may improve IR and potentially reverse T2D.

12. Conclusions and Research Agenda

Originally described in the diabetes arena, IR has now become a key player in common non-communicable diseases such as obesity, metabolic dysfunction, cardiovascular-hepato-nephro-metabolic health, and cancer. Reflecting the complexity of lifestyle habits, such as dietary preferences and variable attitudes towards engaging in physical activity which are intimately associated with psychosocial causes, IR mirrors the challenges faced by developed and developing countries in terms of food security and social equity [

155,

156] as key determinants of health and disease. However, IR is also strongly dependent on physiological processes and is affected by sex and aging. From a therapeutic point of view, the lesson from MASH is that combating IR may be a “necessary but not sufficient” condition [

157] as this physiopathological derangement may spark a dysmetabolic fire that will autonomously self-maintain over time.

Consequently, the next decade demands a concerted, transdisciplinary research agenda. This agenda should focus on (i) deciphering the spatiotemporal dynamics of IR across organs by integrating single-cell multi-omics and advanced in vivo imaging, (ii) mapping the bidirectional crosstalk among hepatokines, myokines, adipokines, and the immune system using CRISPR-based perturbation screens, (iii) developing “digital twins” capable of simulating individual metabolic trajectories and predicting therapeutic responses, (iv) testing combination metabolic therapies such as GLP-1RA + SGLT2 inhibitors and THR-β agonists in adaptive platform trials with clamp-based and imaging-based IR read-outs, (v) exploring microbiome-targeted interventions such as synbiotics to attenuate gut-derived metaflammation, (vi) designing precision-lifestyle interventions driven by wearables, continuous glucose monitoring, and AI-guided feedback loops, and (vii) embedding socio-ecological studies that evaluate how food-insecurity mitigation, urban-design innovations, and fiscal policies modulate population-level IR.

An improved understanding of the molecular events underlying IR and the pathobiology of β-cell exhaustion promises to provide innovative approaches to clinically heterogeneous disease phenotypes spanning common non-transmissible chronic conditions from diabesity, cardiovascular disorders, organ dysfunction and cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and R.W.; validation, A.L. and R.W. formal analysis, A.L. and R.W.; data curation, A.L. and R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L. and R.W.; writing—review and editing, A.L. and R.W.; visualization, A.L.; supervision, A.L. and R.W.; project administration, A.L. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

body mass index |

| CKD |

chronic kidney disease |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| CPT1 |

carnitine O-palmitoiltransferase 1 |

| CVD |

cardiovascular disease |

| GLP-1RA |

glucagon-like peptide receptor 1 agonist(s) |

| HOMA-IR |

homeostasis model of insulin resistance |

| IL-6 |

interleukin-6 |

| IR |

insulin resistance |

| IRR |

incidence rate ratio |

| ISR1/2 |

insulin receptor substrate 1/2) |

| IST |

insulin tolerance test |

| MACE |

major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MASLD |

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH |

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| OR |

odds ratio |

| PCOS |

polycystic ovary syndrome |

| QUICKI |

quantitative insulin sensitivity check index |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| SGLT2 |

sodium-glucose transporter 2 |

| SHBG |

sex hormone binding globulin |

| SRRI |

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| THR-β |

thyroid hormone receptor-β |

| T2D |

type 2 diabetes |

| TLR4 |

toll-like receptor 4 |

| TyG |

triglyceride-glucose index |

References

- Yalow, R.S.; Berson, S.A. Immunoassay of endogenous plasma insulin in man. J Clin Invest. 1960, 39, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalow, R.S.; Berson, S.A. Plasma insulin concentrations in nondiabetic and early diabetic subjects. Determinations by a new sensitive immuno-assay technic. Diabetes 1960:254-60. [CrossRef]

- Aronis, K.N.; Mantzoros, C.S. A brief history of insulin resistance: from the first insulin radioimmunoassay to selectively targeting protein kinase C pathways. Metabolism 2012, 61, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, C.R.; Neville DMJr Roth, J. Insulin-receptor interaction in the obese-hyperglycemic mouse. A model of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1973, 248, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfine, I.D.; Kahn, C.R.; Neville DMJr Roth, J.; Garrison, M.M.; Bates, R.W. Decreased binding of insulin to its receptors in rats with hormone induced insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973, 53, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, C.R.; Flier, J.S.; Bar, R.S.; Archer, J.A.; Gorden, P.; Martin, M.M.; Roth, J. The syndromes of insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans. Insulin-receptor disorders in man. N Engl J Med. 1976, 294, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, G.M. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988, 37, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniyappa R, Chen H, Montagnani M, Sherman A, Quon MJ: Endothelial dysfunction due to selective insulin resistance in vascular endothelium: insights from mechanistic modeling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2020, 319:E629–E646. [CrossRef]

- Batista TM, Haider N, Kahn CR: Defining the underlying defect in insulin action in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 994–1006. [CrossRef]

- Andreadi, A.; Bellia, A.; Di Daniele, N.; Meloni, M.; Lauro, R.; Della-Morte, D.; Lauro, D. The molecular link between oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: A target for new therapies against cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangregorio, F.; Mosconi, E.; Debellis, M.G.; Provini, S.; Esposito, C.; Garolfi, M.; et al. A Systematic Review of Metabolic Syndrome: Key Correlated Pathologies and Non-Invasive Diagnostic Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Z.Q.; Chen, Y.Z.; Huang, Z.M.; Luo, Y.H.; Zeng, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Chen, Y.X.; Fang, J.Y. Metabolic syndrome, its components, and gastrointestinal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 31 prospective cohorts and Mendelian randomization study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024, 39, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamooya, B.M.; Siame, L.; Muchaili, L.; Masenga, S.K.; Kirabo, A. Metabolic syndrome: epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic approaches. Front Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonardo, A.; Ballestri, S.; Marchesini, G.; Angulo, P.; Loria, P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a precursor of the metabolic syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Kostara, C.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Salamou, E.; Guzman, E. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Int Med Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231164548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, B.K.; Bhimineni, C.; Modi, S.; Jahanshahi, A.; Quiza, K.; Bitetto, D. The Role of Insulin Resistance in Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2025, 32, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzobokela, J.; Muchaili, L.; Mwambungu, A.; Masenga, S.K.; Kirabo, A. Pathophysiology and emerging biomarkers of cardiovascular-renal-hepato-metabolic syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1661563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A. The heterogeneity of metabolic syndrome presentation and challenges this causes in its pharmacological management: a narrative review focusing on principal risk modifiers. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2023, 16, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.Y.; Alruwaili, Y.M.; Alsairra, M.N.; Almnaa, S.A.; Mosly, A.F.; Lasuwaidan, D.T.; et al. The Economic and Social Burden of Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Journal of Healthcare Sciences 2024, 4, JOHS2024000873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, E.; Piredda, M.; Sguanci, M.; Mancin, S. What Factors Influence Obesity in Spain? A Multivariate Analysis of Sociodemographic, Nutritional, and Lifestyle Factors Affecting Body Mass Index in the Spanish Population. Healthcare (Basel) 2025, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M.; Acevedo, L.A.; Pennings, N. Insulin Resistance. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507839/].

- Medscape. Updated Nov, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/122501-overview. Last accessed 6 November, 2025.

- Ramos de Mendonça, C.; Cristina Monteiro Galindo, L.; Karoline Alves de Melo Silva, B.; Hilary Avelino de Vasconcelos, B.; de Araújo Bandeira, V.C.; Massao Hirabara, S.; et al. Maternal obesogenic diet causes insulin resistance by modulating insulin signaling pathways in peripheral tissues of offspring: a systematic review. Life Sci. 2025, 380, 123947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Hong, S.C. The impact of sleep and circadian disturbance on hormones and metabolism. Int J Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 591729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldi, G.; Lonardo, A.; Ballestri, S.; Zona, S.; Stentarelli, C.; Orlando, G.; Carli, F.; Carulli, L.; Roverato, A.; Loria, P. Human immunodeficiency virus is the major determinant of steatosis and hepatitis C virus of insulin resistance in virus-associated fatty liver disease. Arch Med Res. 2011, 42, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M.N.; Rocha, G.Z.; Guadagnini, D.; Santos, A.; Magro, D.O.; Assalin, H.B.; Oliveira, A.G.; Pedro, R.J.; Saad, M.J.A. Insulin Resistance in HIV-Patients: Causes and Consequences. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, B.; Smith, U. Cigarrettrökning ger insulinresistens. Nya rön om tobakens metabola effekter [Cigarette smoking causes insulin resistance. New findings on metabolic effects of tobacco]. Lakartidningen. 1995, 92, 731–733. [Google Scholar]

- Swarup, S.; Ahmed, I.; Grigorova, Y.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome. [Updated 2024 Mar 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459248/.

- Amisi, C.A. Markers of insulin resistance in Polycystic ovary syndrome women: An update. World J Diabetes 2022, 13, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Rasquin, L.I.; Anastasopoulou, C. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. [Updated 2025 Jul 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459251/.

- Madan R, Varghese RT; Ranganath. Assessing Insulin Sensitivity and Resistance in Humans. [Updated 2024 Oct 16]. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278954/.

- Vaidya, R.A.; Desai, S.; Moitra, P.; Salis, S.; Agashe, S.; Battalwar, R.; et al. Hyperinsulinemia: an early biomarker of metabolic dysfunction. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2023, 4, 1159664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P.R.E.; Cardin, J.L.; Nisevich-Bede, P.M.; McCarter, J.P. Continuous glucose monitoring in a healthy population: understanding the post-prandial glycemic response in individuals without diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2023, 146, 155640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Launico, M.V. Glucose Tolerance Test. [Updated 2025 Sep 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532915/.

- Sun, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, W.; An, X.; Lian, F. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur J Intern Med. 2025, 131, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, D.; Sivaslioglu, A.; Bulus, H.; Ozturk, B. TyG index is positively associated with HOMA-IR in cholelithiasis patients with insulin resistance: Based on a retrospective observational study. Asian J Surg. 2024, 47, 2579–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avagimyan, A.; Pogosova, N.; Fogacci, F.; Aghajanova, E.; Djndoyan, Z.; Patoulias, D.; et al. Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) as a novel biomarker in the era of cardiometabolic medicine. Int J Cardiol. 2025, 418, 132663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, J.; Bermúdez, V.; Calvo, M.; Olivar, L.C.; Luzardo, E.; Navarro, C.; et al. Optimal cutoff for the evaluation of insulin resistance through triglyceride-glucose index: A cross-sectional study in a Venezuelan population. F1000Res. 2017, 6, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cassia da Silva, C.; Zambon, M.P.; Vasques, A.C.J.; Camilo, D.F.; de Góes Monteiro Antonio, M.Â.R.; Geloneze, B. The threshold value for identifying insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in an admixed adolescent population: A hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2023, 67, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.; Park, J.H.; Jang, E.J.; Park, Y.K.; Yu, J.M.; Park, J.S.; et al. The Cut-off Values of Surrogate Measures for Insulin Sensitivity in a Healthy Population in Korea according to the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2007-2010. J Korean Med Sci. 2018, 33, e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, M.; Bissonnette, S.; Lamantia, V.; Devaux, M.; Faraj, M. Sex-Specific Models to Predict Insulin Secretion and Sensitivity in Subjects with Overweight and Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.S.; Xie, W.; Johnson, W.D.; Cefalu, W.T.; Redman, L.M.; Ravussin, E. Defining insulin resistance from hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Pacini, G.; Brazzale, A.R.; Ahrén, B. Comparative evaluation of simple insulin sensitivity methods based on the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, T.; Gao, L.; Yao, Z.; Shao, S.; Wang, X.; Proud, C.G.; Zhao, J. Hepatic selective insulin resistance at the intersection of insulin signaling and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, P. The endocrine role of hepatokines: implications for human health and disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2025, 16, 1663353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Magenes, V.C.; Bianchi, A.; Rossi, V.; Gatti, A.; Marin, L.; Vandoni, M.; Zuccotti, G. How Can Promoting Skeletal Muscle Health and Exercise in Children and Adolescents Prevent Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes? Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consitt, L.A.; Clark, B.C. The Vicious Cycle of Myostatin Signaling in Sarcopenic Obesity: Myostatin Role in Skeletal Muscle Growth, Insulin Signaling and Implications for Clinical Trials. J Frailty Aging 2018, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, H.T.; Weiskirchen, R. Exercise-Induced Release of Pharmacologically Active Substances and Their Relevance for Therapy of Hepatic Injury. Front Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Woo, G.H.; Kwon, T.H.; Jeon, J.H. Obesity-Driven Metabolic Disorders: The Interplay of Inflammation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 9715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of SCAP/SREBP as Central Regulators of Lipid Metabolism in Hepatic Steatosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, W.; Lobo, M.; Siniawski, D.; Huerín, M.; Molinero, G.; Valéro, R.; Nogueira, J.P. Therapy with cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors and diabetes risk. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 44, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.A.; do Carmo, J.M.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Mouton, A.J.; Hall, J.E. Role of Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance in Hypertension: Metabolic Syndrome Revisited. Can J Cardiol. 2020, 36, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.; McQueen, A.; Chen, T.C.; Wang, J.C. Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis by Glucocorticoids. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015, 872, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Yao, H.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Role of NFAT in the Progression of Diabetic Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 635172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkera, H.A.; Mandarino, L.J. Calcineurin inhibition and new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation. Transplantation. 2013, 95, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, H.; Hruz, P.W.; Mueckler, M. The mechanism of insulin resistance caused by HIV protease inhibitor therapy. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 20251–20254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, J.; Struthers, H.; Horj, C.B.; Hruz, P.W. A structural basis for the acute effects of HIV protease inhibitors on GLUT4 intrinsic activity. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279, 55147–55152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhuang, X. Atypical antipsychotics-induced metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a critical review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019, 15, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaresh Rizi, E.; Teo, Y.; Leow, M.K.; Venkataraman, K.; Khoo, E.Y.; Yeo, C.R.; Chan, E.; Song, T.; Sadananthan, S.A.; Velan, S.S.; Gluckman, P.D.; Lee, Y.S.; Chong, Y.S.; Tai, E.S.; Toh, S.A.; Khoo, C.M. Ethnic Differences in the Role of Adipocytokines Linking Abdominal Adiposity and Insulin Sensitivity Among Asians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015, 100, 4249–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-Guevara, I.A.; Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; Osuna-Prieto, F.J.; Labayen, I.; Aguilera, C.M.; Ruiz, J.R. The role of sex in the relationship between fasting adipokines levels, maximal fat oxidation during exercise, and insulin resistance in young adults with excess adiposity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023, 216, 115757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R.; Lonardo, A. Sex Hormones and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh Pahlavani, H.; Laher, I.; Knechtle, B.; Zouhal, H. Exercise and mitochondrial mechanisms in patients with sarcopenia. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 1040381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raygor, V.; Abbasi, F.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Kim, S.; Ingelsson, E.; Reaven, G.M.; Knowles, J.W. Impact of race/ethnicity on insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridaemia. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019, 16, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasishta, S.; Ganesh, K.; Umakanth, S.; Joshi, M.B. Ethnic disparities attributed to the manifestation in and response to type 2 diabetes: insights from metabolomics. Metabolomics 2022, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.K.; Jensen, M.D. Metabolic changes in aging humans: current evidence and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Invest. 2022, 132, e158451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, J.; Chen, P.J.; Xiao, W.H. Mechanism of increased risk of insulin resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarambino, T.; Crispino, P.; Guarisco, G.; Giordano, M. Gender Differences in Insulin Resistance: New Knowledge and Perspectives. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023, 45, 7845–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Jamalinia, M.; Weiskirchen, R. Sex differences in MASLD. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fan, H.; Wang, T.; Yu, B.; Mao, S.; Wang, X.; et al. TyG index is positively associated with risk of CHD and coronary atherosclerosis severity among NAFLD patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022, 21, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Carnicero, J.A.; Molina-Baena, B.; García-García, F.J.; Sosa, P.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Gender-specific capacity of insulin resistance proxies to predict functional decline in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2024, 28, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Wu, D.; Qiu, Y. Adipose tissue macrophage in obesity-associated metabolic diseases. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 977485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Leung, J.C.K.; Chan, L.Y.Y.; Yiu, W.H.; Tang, S.C.W. A global perspective on the crosstalk between saturated fatty acids and Toll-like receptor 4 in the etiology of inflammation and insulin resistance. Prog Lipid Res. 2020, 77, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misceo, D.; Mocciaro, G.; D'Amore, S.; Vacca, M. Diverting hepatic lipid fluxes with lifestyles revision and pharmacological interventions as a strategy to tackle steatotic liver disease (SLD) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Nutr Metab (Lond). 2024, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Dasgupta, S.; Kundu, R.; Maitra, S.; Das, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Ray, S.; Majumdar, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S. Fetuin-A acts as an endogenous ligand of TLR4 to promote lipid-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2012, 18, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Thurmond, D.C. Mechanisms by Which Skeletal Muscle Myokines Ameliorate Insulin Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasan, I.-M.; Tanase, M.; Delia, C.E.; Gradisteanu-Pircalabioru, G.; Cimpean, A.; Ionica, E. Metaflammation’s Role in Systemic Dysfunction in Obesity: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus. 2022, 14, e22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. The Pivotal Role of the Western Diet, Hyperinsulinemia, Ectopic Fat, and Diacylglycerol-Mediated Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.A.; Akter, S.; Bhuiyan, F.R.; Shah, M.R.; Rahman, M.K.; Ali, L. Subclinical inflammation in relation to insulin resistance in prediabetic subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Res Notes 2016, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Bazzano, L.; He, J.; Mi, J.; Chen, W. Temporal relationship between inflammation and insulin resistance and their joint effect on hyperglycemia: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symons, J.D.; McMillin, S.L.; Riehle, C.; Tanner, J.; Palionyte, M.; Hillas, E.; Jones, D.; Cooksey, R.C.; Birnbaum, M.J.; McClain, D.A.; Zhang, Q.J.; Gale, D.; Wilson, L.J.; Abel, E.D. Contribution of insulin and Akt1 signaling to endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the regulation of endothelial function and blood pressure. Circ Res. 2009, 104, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascali, F.; Hemann, C.; Samons, K.; Chen, C.A.; Zweier, J.L. Hypoxia and reoxygenation induce endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling in endothelial cells through tetrahydrobiopterin depletion and S-glutathionylation. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3679–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Lucke-Wold, B.P.; Li, X.; Logsdon, A.F.; Xu, L.C.; Xu, S.; LaPenna, K.B.; Wang, H.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Siedlecki, C.A.; Huber, J.D.; Rosen, C.L.; He, P. Reduction of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Increases the Adhesiveness of Constitutive Endothelial Membrane ICAM-1 through Src-Mediated Phosphorylation. Front Physiol. 2018, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; RKashyap, S.; AMajor, J.; Silverstein, R.L. Insulin promotes macrophage foam cell formation: potential implications in diabetes-related atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2012, 92, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerf, M.E. Cardiac Glucolipotoxicity and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas) 2018, 54, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorop, O.; van de Wouw, J.; Chandler, S.; Ohanyan, V.; Tune, J.D.; Chilian, W.M.; Merkus, D.; Bender, S.B.; Duncker, D.J. Experimental animal models of coronary microvascular dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2020, 116, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amario, D.; Migliaro, S.; Borovac, J.A.; Restivo, A.; Vergallo, R.; Galli, M.; Leone, A.M.; Montone, R.A.; Niccoli, G.; Aspromonte, N.; Crea, F. Microvascular Dysfunction in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front Physiol. 2019, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorp, A.A.; Schlaich, M.P. Relevance of Sympathetic Nervous System Activation in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. J Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 341583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, P.F.; Li, Q.; Khamaisi, M.; Qiang, G.F. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Macrovascular Complications. Int J Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 4301461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pino, A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis: Implications for Insulin-Sensitizing Agents. Endocr Rev. 2019, 40, 1447–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, M.G. The Look AHEAD Trial: Translating Lessons Learned Into Clinical Practice and Further Study. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, S.; Sacchetti, M.; Haxhi, J.; Orlando, G.; Zanuso, S.; Cardelli, P.; et al. The Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study 2 (IDES-2): a long-term behavioral intervention for adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle. Trials 2015, 16, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Dixon, D.L.; Buckley, L.F.; Abbate, A. Glucose-Lowering Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: State-of-the-Art Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018, 93, 1629–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, W.J.; Spann, M.D.; Aher, C.V.; Williams, D.B. Cardiovascular risk reduction following metabolic and bariatric surgery. Ann Transl Med. 2020, 8 (Suppl. S1), S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]