Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participants

2.2. Fibroblast Growth Factor 19 and Choline Metabolism

2.3. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21

2.4. Galectin-3

2.5. Irisin

2.6. Leptin and Adiponectin: The Relevance of Sex Dimorphism

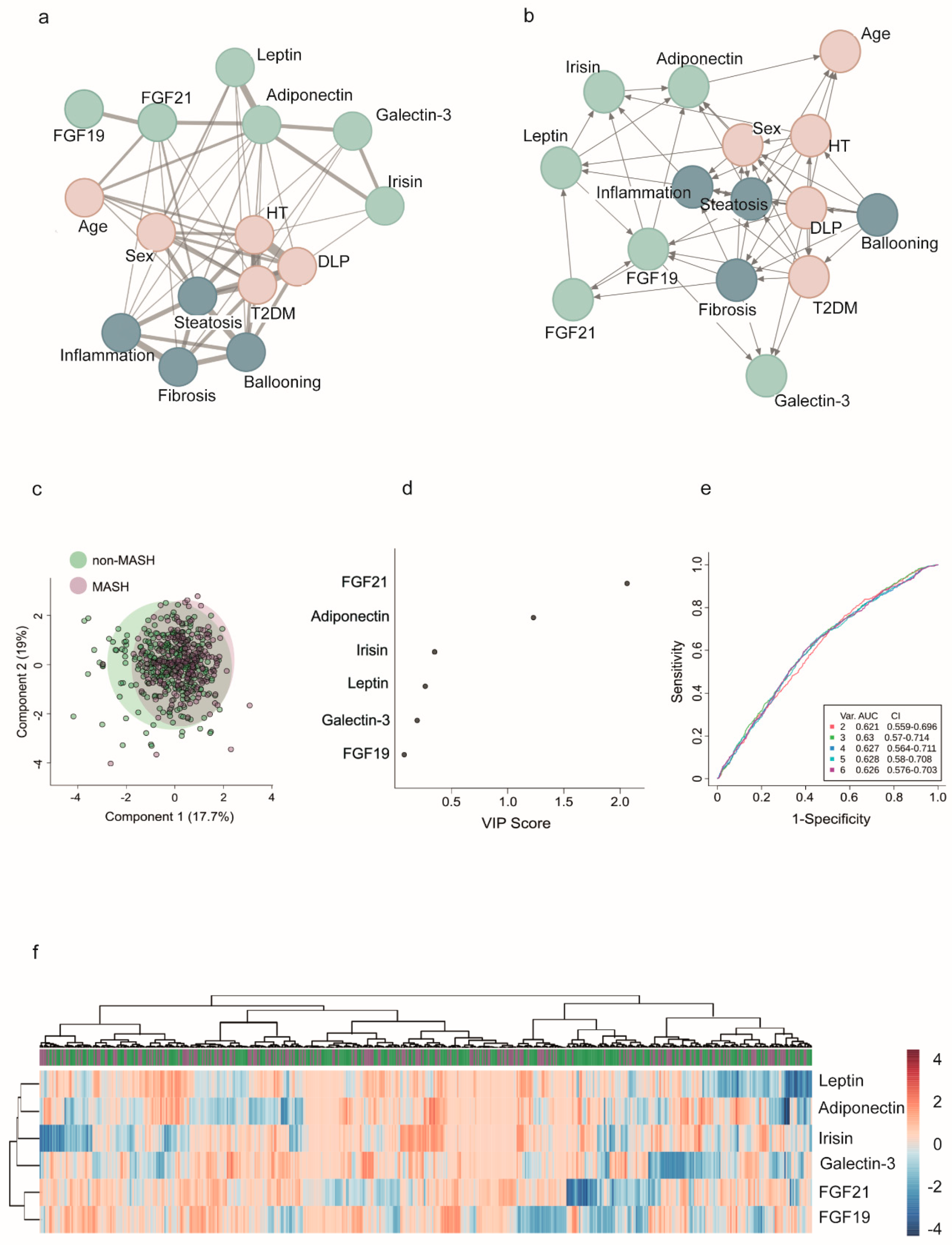

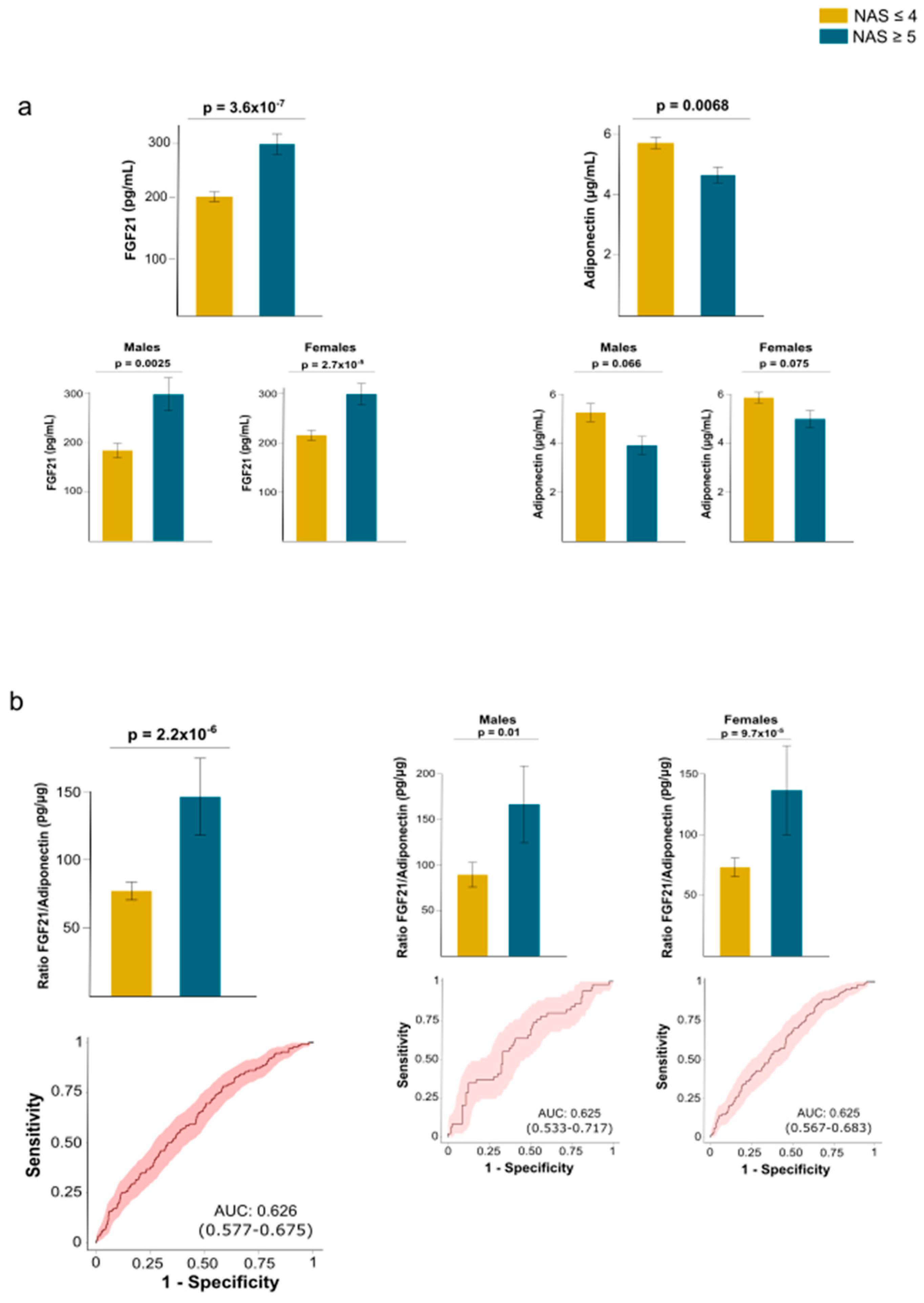

2.7. Network Modeling and Insights into Patterns: The Functional Overlap Between FGF21 and Adiponectin

3. Discussion

4. Strenghts and Limitations of the Study

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Design

5.2. Sampling and Data Collection

5.3. Biochemical and Histologic Assessments

5.4. Mass Spectrometry for Selected Metabolites

5.5. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| NAS | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| UHPLC | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

References

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8.

- Ellison-Barnes, A.; Johnson, S.; Gudzune, K. Trends in obesity prevalence among adults aged 18 through 25 years, 1976-2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2073–2074. [CrossRef]

- Fryar, C.D.; Carroll, M.D.; Afful, J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 Through 2017–2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-adult-17-18/obesity-adult.htm (Accessed 18 Jul 2025).

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; París, M.; Sabench, F.; Del Castillo, D.; López-Miranda, J.; Menéndez, J.A.; Camps, J.; Joven, J. Plasma metabolic alterations in patients with severe obesity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 374–387. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J.; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014. [CrossRef]

- Azzu, V.; Vacca, M.; Virtue, S.; Allison, M.; Vidal-Puig, A. Adipose tissue-liver cross talk in the control of whole-body metabolism: Implications in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1899–1912. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 706978. [CrossRef]

- Cypess, A.M. Reassessing human adipose tissue. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 768–779. [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Kajimura, S. Metabolic adaptation and maladaptation in adipose tissue. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Franco, A.; Castañé, H.; Martínez-Navidad, C., Placed-Gallego, C.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Samarra, I.; Canela-Capdevila, M.; Arenas, M.; Zorzano, A.; Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Castillo, D.D.; Paris, M.; Menendez, J.A.; Camps, J.; Joven, J. Metabolic adaptations in severe obesity: Insights from circulating oxylipins before and after weight loss. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 246–258. [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Trauner, M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell. Metab. 2022, 34, 1700–1718. https://. [CrossRef]

- Gérard, P. Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 147–162. [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.H.; Rutkowski, J.M.; Scherer, P.E. Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell. Metab. 2016, 23, 770–784. [CrossRef]

- Jangam, T.C.; Desai, S.A.; Patel, V.P.; Pagare, N.B.; Raut, N.D. Exosomes as therapeutic and diagnostic tools: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, K.; Cohen, T.S. Can you trust your gut? Implicating a disrupted intestinal microbiome in the progression of NAFLD/NASH. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 592157. [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.M.; Dilts, M.; Pokhrel, S.; Stahl, Z.; Boehme, S.; Wang, X.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Fibroblast growth factor 19 alters bile acids to induce dysbiosis in mice with alcohol-induced liver disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 71–87. [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Tondo, M.; Cedó, L.; Farràs, M.;, Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Trimethylamine N-oxide: A link among diet, gut microbiota, gene regulation of liver and intestine cholesterol homeostasis and HDL function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3228. [CrossRef]

- Camps, J.; Castañé, H.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Arenas, M.; Iftimie, S.; Joven, J. On the role of paraoxonase-1 and chemokine ligand 2 (C-C motif) in metabolic alterations linked to inflammation and disease. A 2021 update. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 971. [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Olaniyi, P.; Isarinade, T.; Yusuf, I.A. Recent advances in bariatric surgery: a narrative review of weight loss procedures. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 2023, 85, 6091–6104. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastián, D.; Vives, S.; Ivanova, S.; Bartoccioni, P.; Kakimoto, P.; Plana, N.; Veiga, S.R.; Hernández, V.; Vasconcelos, N.; Peddinti, G.; Adrover, A.; Jové, M.; Pamplona, R.; Gordaliza-Alaguero, I.; Calvo, E.; Cabré, N.; Castro, R.; Kuzmanic, A.; Boutant, M.; Sala, D.; Hyotylainen, T.; Orešič, M.; Fort, J.; Errasti-Murugarren, E.; Rodrígues, C.M.P.; Orozco, M.; Joven, J.; Cantó, C.; Palacin, M.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Vendrell, J.; Zorzano, A. Deficient endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine transfer causes liver disease. Cell 2019, 177, 881–895.e17. [CrossRef]

- Naón, D.; Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Shinjo, S.; Wieczor, M.; Ivanova, S.; Martins de Brito, O.; Quintana, A.; Hidalgo, J.; Palacín, M.; Aparicio, P.; Castellanos, J.; Lores, L.; Sebastián, D.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Vendrell, J.; Joven, J.; Orozco, M.; Zorzano, A.; Scorrano, L. Splice variants of mitofusin 2 shape the endoplasmic reticulum and tether it to mitochondria. Science 2023, 380, eadh9351. [CrossRef]

- Priest, C.; Tontonoz, P. Inter-organ cross-talk in metabolic syndrome. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 1177–1188. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.P.M.D.; Maio, M.C.; Lemes, M.A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Haber, J.F.D.S.; Bechara, M.D.; Prado, P.S.D. Jr.; Rauen, E.C.; Costa, F.; Pereira, B.C.A.; Flato, U.A.P.; Goulart, R.A.; Chagas, E.F.B.; Barbalho, S.M. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and organokines: What is now and what will be in the future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 498. https:/doi: 10.3390/ijms23010498.

- Ma, F.; Longo, M.; Meroni, M.; Bhattacharya, D.; Paolini, E.; Mughal, S.; Hussain, S.; Anand, S.K.; Gupta, N.; Zhu, Y.; Navarro-Corcuera, A.; Li, K.; Prakash, S.; Cogliati, B.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Yurdagul, A. Jr.; Rom, O.; Wang, L.; Fried, S.K.; Dongiovanni, P.; Friedman, S.L.; Cai, B. EHBP1 suppresses liver fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Cell. Metab. 2025, 37, 1152–1170.e7. [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R.; Schnabl, B.; Knight, R.; Loomba, R. Current concepts, opportunities, and challenges of gut microbiome-based personalized medicine in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. Metab. 2021, 33, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- van de Wiel, S.M.W.; Bijsmans, I.T.G.W.; van Mil, S.W.C.; van de Graaf, S.F.J. Identification of FDA-approved drugs targeting the farnesoid X receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2193. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, A.; Aydin, Ö.; Olsson, L.M.; Sjöland, W.; Henricsson, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Marschall, H.U.; Franken, R.; van de Laar, A.; Gerdes, V.; Meijnikman, A.S.; Hofsø, D.; Groen, A.K.; Hjelmesæth, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Bäckhed, F. Alterations in bile acid kinetics after bariatric surgery in patients with obesity with or without type 2 diabetes. EBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105265. [CrossRef]

- Barb, D.; Kalavalapalli, S.; Godinez Leiva, E.; Bril, F.; Huot-Marchand, P.; Dzen, L.; Rosenberg, J.T.; Junien, J.L.; Broqua, P.; Rocha, A.O.; Lomonaco, R.; Abitbol, J.L.; Cooreman, M.P.; Cusi, K. Pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with T2D and MASLD. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 979-991. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, W.; Ma, X.; Ren, L.; Feng, M.; Hu, S.; Xue, C.; Chen, R. Roles and mechanisms of choline metabolism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cancers. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 2024, 29, 182. [CrossRef]

- Schugar, R.C.; Gliniak, C.M.; Osborn, L.J.; Massey, W.; Sangwan, N.; Horak, A.; Banerjee, R.; Orabi, D.; Helsley, R.N.; Brown, A.L.; Burrows, A.; Finney, C.; Fung, K.K.; Allen, F.M.; Ferguson, D.; Gromovsky, A.D.; Neumann, C.; Cook, K.; McMillan, A.; Buffa, J.A.; Anderson, J.T.; Mehrabian, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Willard, B.; Mak, T.D.; Armstrong, A.R.; Swanson, G.; Keshavarzian, A.; Garcia-Garcia, J.C.; Wang, Z.; Lusis, A.J.; Hazen, S.L.; Brown, J.M. Gut microbe-targeted choline trimethylamine lyase inhibition improves obesity via rewiring of host circadian rhythms. Elife 2022, 11, e63998. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Zhang, J.; Gong, Y.; Gupte, J.; Ye, J.; Weiszmann, J.; Samayoa, K.; Coberly, S.; Gardner, J.; Wang, H.; Corbin, T.; Chui, D.; Baribault, H.; Li, Y. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) deficiency improves insulin resistance and glucose metabolism under diet-induced obesity conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 30470–30480. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, C.; Mo, C.; Ding, B.S. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) mediates the crosstalk between the gut microbiota and hepatic vascular niche to alleviate liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 964477. [CrossRef]

- Kharitonenkov, A.; Shiyanova, T.L.; Koester, A.; Ford, A.M.; Micanovic, R.; Galbreath, E.J.; Sandusky, G.E.; Hammond, L.J.; Moyers, J.S.; Owens, R.A.; Gromada, J.; Brozinick, J.T.; Hawkins, E.D.; Wroblewski, V.J.; Li, D.S.; Mehrbod, F.; Jaskunas, S.R.; Shanafelt, A.B. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 1627–1635. [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, S.A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. A dozen years of discovery: Insights into the physiology and pharmacology of FGF21. Cell. Metab. 2019, 29, 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.; Xiao, J.; Ng, C.H.; Law, M.; Gunalan, S.Z.; Danpanichkul, P.; Ramadoss, V.; Sim, B.K.L.; Tan, E.Y.; Teo, C.B.; Nah, B.; Teng, M.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Seko, Y.; Lim, M.C.; Takahashi, H.; Nakajima, A.; Noureddin, M.; Muthiah, M.; Huang, D.Q.; Loomba, R. Comparative efficacy of pharmacologic therapies for MASH in reducing liver fat content: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology 2024, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Rolph, T.; Knott, M.; Dubourg, J. FGF21 agonists: An emerging therapeutic for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and beyond. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 562–576. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Borlak, J. A comparative genomic study across 396 liver biopsies provides deep insight into FGF21 mode of action as a therapeutic agent in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70218. [CrossRef]

- Brunt, E.M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Wilson, L.A.; Belt, P.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011, 53, 810–820. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Fibla, M.; Fernández-Julià, R.; París, M.; Sabench, F.; Castillo, D.D.; Menéndez, J.A.; Camps, J.; Joven, J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy reverses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolism 2019, 99, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.S.; Xu, A.; Woo, Y.C.; Tso, A.W.; Cheung, S.C.; Fong, C.H.; Tse, H.F.; Chau, M.T.; Cheung, B.M.; Lam, K.S. Serum fibroblast growth factor-21 levels are associated with carotid atherosclerosis independent of established cardiovascular risk factors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 2454–2459. [CrossRef]

- Sciacchitano, S.; Lavra, L.; Morgante, A.; Ulivieri, A.; Magi, F.; De Francesco, G.P.; Bellotti, C.; Salehi, L.B.; Ricci, A. Galectin-3: One molecule for an alphabet of diseases, from A to Z. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 379. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, P. Galectin-3 in metabolic disorders: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 31, 424–437. [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, S.; Yavuz, B.G.; Mohamed, Y.I.; Lee, S.S.; Yao, J.C.; Hu, Z.I.; LaPelusa, M.; Xiao, L.; Sun, R.; Morris, J.S.; Hatia, R.I.; Hassan, M.; Duda, D.G.; Diab, M.; Mohamed, A.; Nassar, A.; Amin, H.M.; Kaseb, A.O. Circulating galectin-3: A prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Precis. Oncol. 2024, 7, 255–262. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, A.C.; Humphries, D.C.; Herman, K.; Roper, J.A.; Holyer, I.; Mabbitt, J.; Mills, R.; Nilsson, U.J.; Leffler, H.; Pedersen, A.; Schambye, H.; Zetterberg, F.; Slack, R.J. Effect of GB1107, a novel galectin-3 inhibitor on pro-fibrotic signalling in the liver. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 985, 177077. [CrossRef]

- Comeglio, P.; Guarnieri, G.; Filippi, S.; Cellai, I.; Acciai, G.; Holyer, I.; Zetterberg, F.; Leffler, H.; Kahl-Knutson, B.; Sarchielli, E.; Morelli, A.; Maggi, M.; Slack, R.J.; Vignozzi, L. The galectin-3 inhibitor selvigaltin reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis in a high fat diet rabbit model of metabolic-associated steatohepatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1430109. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yu, F.; Wei, W.P.; Yang, P.; Zhang, R.; Sheng, Y.; Shi, YQ. Relationship between circulating irisin levels and overweight/obesity: A meta-analysis. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 1444–1455. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamada, T.; Katagiri, H. Inter-organ communication involved in brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1461, 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wu, K.; Ke, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, J. Circulating irisin levels in patients with MAFLD: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1464951. [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; Lonardo, A.; Maki, P.M.; McCullough, L.D.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Rubin, J.B.; Sandberg, K.; Suzuki, A. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. https.//doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0.

- Friedman, J.; Halaas, J. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in Mammals. Nature 1998, 395, 763–770. [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Soskic, S.; Essack, M.; Arya, S.; Stewart, A.J.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Leptin and obesity: Role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 585887. [CrossRef]

- Maxim, M.; Soroceanu, R.P.; Vlăsceanu, V.I.; Platon, R.L.; Toader, M.; Miler, A.A.; Onofriescu, A.; Abdulan, I.M.; Ciuntu, B.M.; Balan, G.; Trofin, F.; Timofte, D.V. Dietary habits, obesity, and bariatric surgery: A review of impact and interventions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 474. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Scherer, P. Adiponectin, the past two decades. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 8, 93–100. https://doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjw011.

- Buechler, C.; Wanninger, J.; Neumeier, M. Adiponectin, a key adipokine in obesity related liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 2801–2811. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, B.; Cheng, X.; Wang, D.; la Gahu, Z.; Xue, Z.; Da, Y.; Li, D.; Yao, Z.; Gao, F.; Xu, A.; Zhang, R. Adiponectin-derived active peptide ADP355 exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic activities in thioacetamide-induced liver injury. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19445. [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Feng, T.: Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Xu, A. The FGF21-adiponectin axis in controlling energy and vascular homeostasis. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 8, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.T.; Xiao, T.M.; Wu, C.X.; Cheng, J.Y.; Li, L.Y. Correlation of adiponectin gene polymorphisms rs266729 and rs3774261 with risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 798417. [CrossRef]

- Patt, M.; Karkossa, I.; Krieg, L.; Massier, L.; Makki, K.; Tabei, S.; Karlas, T.; Dietrich, A.; Gericke, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Blüher, M.; von Bergen, M.; Schubert, K.; Kovacs, P.; Chakaroun, R.M. FGF21 and its underlying adipose tissue-liver axis inform cardiometabolic burden and improvement in obesity after metabolic surgery. EBioMedicine 2024, 110, 105458. [CrossRef]

- Jirapinyo, P.; McCarty, T.R.; Dolan, R.D.; Shah, R.; Thompson, C.C. Effect of endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 511–524.e1. [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Bedossa, P.; Ponnaiah, M.; Oppert, J.M.; Siksik, J.M.; Genser, L.; Charlotte, F.; Thabut, D.; Clement, K.; Ratziu, V. Persistence of severe liver fibrosis despite substantial weight loss with bariatric surgery. Hepatology 2022, 76, 456–468. [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Hartman, M.L.; Lawitz, E.J.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Boursier, J.; Bugianesi, E.; Yoneda, M.; Behling, C.; Cummings, O.W.; Tang, Y.; Brouwers, B.; Robins, D.A.; Nikooie, A.; Bunck, M.C.; Haupt, A.; Sanyal, A.J.; SYNERGY-NASH Investigators. Tirzepatide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Bhatt, D.L.; Alkhouri, N.; Frias, J.P.; Bedossa, P.; Harrison, S.A.; Lazas, D.; Barish, R.; Gottwald, M.D.; Feng, S.; Agollah, G.D.; Hartsfield, C.L.; Mansbach, H.; Margalit, M.; Abdelmalek, M.F. Randomized, controlled trial of the FGF21 analogue pegozafermin in NASH. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 998–1008. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q.; Wong, V.W.S.; Rinella, M.E.; Boursier, J.; Lazarus, J.V.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Loomba, R. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 14. [CrossRef]

- Huttasch, M.; Roden, M.; Kahl, S. Obesity and MASLD: Is weight loss the (only) key to treat metabolic liver disease? Metabolism 2024, 157, 155937. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, N.; Camps, J.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.; Arija, V.; Ferre, N.; Tous, M.; Simo, D.; Murphy, M.M.; Vilella, E.; Joven, J. Diet and lifestyle are associated with serum C-reactive protein concentrations in a population-based study. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2005, 145, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; Yeh, M.; McCullough, A.J.; Sanyal, A.J.; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Chapski, D.J.; Baiges-Gaya, G., Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Castañé, H.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; París, M.; Sabench, F.; Castillo, D.D.; Del Bas, J.M.; Tomé, M.; Bodineau, C.; Sola-García, A.; López-Miranda, J.; Martín-Montalvo, A.; Durán, R.V.; Vondriska, T.M.; Rosa-Garrido, M.; Camps, J.; Menéndez, J.A.; Joven,.

- J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with severe obesity restores adaptive responses leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7830. [CrossRef]

| Variable |

Controls (n = 258) |

Severe obesity (n = 923) |

P-value |

| Women, n (%) | 121 (47.1) | 677 (73.4) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 45 (35 - 62) | 49 (41 - 56) | 0.347 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 (23.3 - 29.8) | 43.9 (40.3 - 48.4) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89 (78 - 98) | 130 (120 - 139) | <0.001 |

| T2DM, n (%) | 18 (7.0) | 253 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 40 (15.5) | 406 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 25 (9.7) | 234 (25.4) | <0.001 |

| Conventional biochemical variables | |||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.7 (4.3 - 5.2) | 6.7 (5.5 - 8.5) | <0.001 |

| Insulin (pmol/L) | 47.0 (29.3 - 65.8) | 67.8 (37.7 - 109.5) | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.4 (0.9 - 2.2) | 3.2 (1.7 - 5.7) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.7 - 1.5) | 1.5 (1.2 - 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2 (4.7 - 5.9) | 4.0 (3.5 - 4.7) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.1 (2.6 - 3.8) | 2.4 (1.9 – 3.0) | <0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.4 (1.2 - 1.8) | 1.0 (0.8 - 1.2) | <0.001 |

| ALT (μKat/L) | 0.3 (0.2 - 0.4) | 0.6 (0.4 - 0.9) | <0.001 |

| AST (μKat/L) | 0.3 (0.3 - 0.4) | 0.6 (0.4 - 0.8) | <0.001 |

| GGT (μKat/L) | 0.2 (0.2 - 0.4) | 0.4 (0.2 - 0.6) | <0.001 |

| Organokines and metabolites | |||

| FGF19 (pg/mL) | 37.2 (19.0 – 70.7) | 21.3 (6.2 - 49.9) | <0.001 |

| Betaine (μM) | 7.5 (7.3 - 8.6) | 7.0 (5.5 - 8.8) | 0.163 |

| Choline (μM) | 8.8 (8.2 - 10.7) | 3.9 (3.0 - 5.9) | <0.001 |

| TMA (μM) | 18.1 (14.7 - 20.1) | 3.2 (2.2 - 5.2) | <0.001 |

| TMAO (μM) | 0.5 (0.4 - 1.1) | 0.6 (0.4 - 0.9) | 0.957 |

| FGF21 (pg/mL) | 119.7 (25.6 - 222.8) | 164.2 (54.5 - 326.1) | <0.001 |

| Galectin-3 (ng/mL) | 11.3 (6.2 - 17.3) | 12.7 (6.6 - 21.2) | 0.080 |

| Irisin (ng/mL) | 1.1 (0.6 - 1.6) | 1.5 (0.8 - 2.4) | <0.001 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 12.0 (5.4 - 23.0) | 51.6 (26.7 - 85.1) | <0.001 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) | 4.4 (2.9 - 6.8) | 4.2 (2.4 - 7.5) | 0.225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).