1. Introduction

Obesity and its related abnormalities are the most serious threats to public health worldwide [

1,

2]. Obesity is a chronic and systemic disease characterised by excessive fat accumulation, which disrupts the normal functioning of tissues and organs [

3]. The consequences of obesity are complex, and many aspects are still not fully understood. To effectively mitigate its metabolic impact, proactive prevention strategies are essential. When these strategies are insufficient, targeted medications and aggressive weight loss interventions become necessary [

4,

5,

6,

7]. A specific group of patients suffering from severe obesity, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 40 kg/m² or greater, requires special attention due to their exceptionally high risk of life-threatening complications [

8,

9].

These patients provide a valuable model for studying how the circulating lipidome reflects metabolic abnormalities caused by changes in fat accumulation and weight loss [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In patients with severe obesity, weight loss achieved through lifestyle changes is often not sustained in the long term, and there is no sufficient information on the role of new effective medications for obesity management [

14]. In contrast, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and other more invasive surgical procedures can lead to rapid, significant, and sustained weight loss, with effects observable at the cellular level [

15,

16,

17]. These surgeries lead to systemic metabolic changes [

18,

19] and highlight the crucial roles of the liver and adipose tissue in regulating the complex lipid metabolism processes associated with obesity [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The effect of weight loss on circulating lipid levels has not been thoroughly investigated, primarily due to the significant challenges related to studying the diversity of human lipids. For instance, the most widely accepted classification system identifies over 50,000 unique lipid structures, many of which exist in tiny quantities. As a result, investigators will need to critically evaluate the vast amount of information generated from lipidomics. A practical research approach should combine high-throughput lipidomics methods with computational data processing tools and clinico-biological information [

18,

19,

26,

27]. In this study, we take advantage of the weight loss observed after LSG in patients with severe obesity to investigate their disrupted lipid metabolism and the impact of weight loss on improving metabolic health. Our findings may contribute to personalised management strategies for obesity-related conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Participants

This pilot study received approval from our institution's ethics committee (EPIMET PI21/00510_083, PL4NASH112/2021, and EOM 244/2024) by the procedures outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

We recruited 50 healthy, non-obese individuals from a population study conducted by the Institut d'Investigació Sanitària Pere Virgili [

28]. This group, referred to as Cohort 1, followed standardised biobanking strategies and adhered to protocol adjustments for sample collection and maintenance. To ensure reliable results, blood samples were collected from all participants between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m., after requiring them to fast for at least 10 hours and to refrain from physical activity for the last 30 minutes prior to sample collection. The samples were processed within two hours and stored at -80ºC until analysis.

We enrolled 50 patients with severe obesity scheduled to undergo LSG who had maintained a stable weight for at least one month before surgery (Cohort 2). Blood samples from this cohort were collected during the week before surgery. To study the effects post-surgery, additional blood samples were collected during a scheduled visit exactly one year after the procedure (Cohort 3). These patients were recruited from a prospective longitudinal study registered at ClinicalTrials.org (document number: NCT05554224). All eligible patients met the inclusion criteria for LSG, which stipulated that participants must be over 18 years old, not pregnant or breastfeeding, have undergone a psychiatric evaluation, and have a BMI of 35 kg/m² or greater. Exclusion criteria included clinical or analytical evidence of severe illness, chronic or acute inflammation, cancer, or infectious diseases. Our previous findings informed our approach to determining the sample size and matching criteria using the algorithm from the MatchIt R package [

4,

27,

29]. All participants in the study shared a similar ethnic background and were recruited in line with the typical skewed sex distribution observed in our patient population, which consisted of 60% women and 40% men. To evaluate the effectiveness of LSG in reducing body weight and to investigate associated metabolic differences, patients were arbitrarily classified as total responders if their post-surgical BMI fell below 35 kg/m² and as partial responders if it remained above 35 kg/m². We measured selected biochemical parameters in a single batch for all participants using standard tests on a Roche Modular Analytics system (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). All clinical and surgical interventions were designed and implemented according to the most recent evidence-based guidelines for obesity treatment [

30].

2.2. Liver Biopsies and Genotyping

The variation in surgical responses necessitates risk stratification based on baseline liver damage and genotypes that are known to influence the disease. Wedge liver biopsies were collected during surgery. These biopsies were stained using hematoxylin and eosin, as well as Masson's trichrome stain. They were then scored using whole-slide imaging and a validated histological method to evaluate steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis [

31,

32]. We extracted DNA from buffy coats to analyse allele frequencies of gene polymorphisms using TaqMan™ SNP Genotyping Assays in an OpenArray AutoLoader instrument coupled to a QuantStudio 12K qPCR system (Thermo Fisher, Barcelona, Spain). Specifically, we assessed four SNPs of the FTO gene (rs9939609, rs9930506, rs8050136, and rs17817449), as well as one SNP each from PNPLA3 (rs738409) and TRIB1AL (rs6982502). We selected these SNPs due to their known associations with obesity, liver fat accumulation, and lipid regulation [

33].

2.3. Lipidomics Analyses

Details regarding the extraction columns, the composition of mobile phases and solvents, and the various gradients can be found elsewhere [

27,

34]. Additional experimental data, reference spectra, and analytical procedures are available through the Metabolights database and repository under the study number MTBLS7758. We obtained lipid extracts using either a mixture of tert-butyl ether and methanol in a 1:2 (v/v) ratio containing 0.5% acetic acid or simply methanol. The process involves sample preparation and analyses using a chromatography system that includes an ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatograph (UHPLC) coupled with a quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QTOF), which was equipped with an electrospray ionisation (ESI) source. This system, provided by Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA), consisted of a binary pump (G4220A) and an autosampler (G4226A), which was maintained at 4°C. To ensure measurement reproducibility, we injected lipid extracts from a pool of different samples twice daily and conducted quality control checks after every 20 analyses. Labelled internal standards were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA), or the SPLASH mixture from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). We employed a semi-targeted approach, utilising selected standards from each lipid category to create calibration curves for quantifying the corresponding lipid species. We used a representative standard mixture from the same lipid class to measure lipids with similar chemical structures. Labelled internal standards were implemented to adjust the responses of each detected lipid species. To address potential drawbacks, we followed detailed protocols in lipidomic analysis [

34,

35,

36], ensuring that accurate masses and isotopic distributions aligned with the Metlin PCDL database (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) and Lipid MASS®. Quantification was performed using the Mass Hunter Quantitative Analysis B.07.00 software from Agilent Technologies.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio (R version 4.0.2) and available modules in MetaboAnalyst™. We utilized the Readxl and dplyr packages for data management. We performed the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess the normality of each variable's distribution. To maintain consistency, we employed non-parametric methods in our descriptive statistics. The Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for comparisons between two groups and multiple groups, respectively. We applied the Fisher Exact test to categorical variables. The Tableone package helped us summarise relevant data from our cohorts, presenting continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables as counts and percentages. For graphical representations, we used the ggplot2, ggpubr, and pROC packages to create box plots, bar plots, correlation plots, and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. When necessary, we performed additional analyses, including hierarchically clustered heatmaps, Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), random forest analysis, and biomarker and enrichment analysis using MetaboAnalyst. A Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) p-value <0.05 was considered significant for the overall analyses, and a Bonferroni p-value <0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. LSG is Effective in Inducing Weight Loss

We included a group of healthy, non-obese individuals as controls to compare the changes in biochemical variables of patients with severe obesity and to evaluate the effects of surgical weight loss. The characteristics of the participants (

Table 1) highlighted the connection between excess body fat and metabolic health. One year after LSG, patients were still classified as having obesity, even though they experienced 27% reduction in BMI. A decrease in the number of prescribed medications further indicated significant improvements in conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia. Moreover, laboratory markers related to glucose and lipid metabolism, along with indicators of liver damage, returned to levels comparable to those of the control group. In parallel, non-invasive imaging techniques conducted on a subset of participants revealed significant differences in fat distribution among the groups (

Supplementary Figure S1).

3.2. The Circulating Lipidome Captures the Systemic Metabolic Stress in Severe Obesity

The observed differences in circulating lipidome between non-obese individuals and patients with severe obesity reflect a complex and multifaceted dysregulation. Patients with severe obesity exhibited significantly higher levels of circulating fatty acyls and glycerolipids. In contrast, concentrations of glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and sterol lipids were markedly lower (

Figure 1A). PLS-DA demonstrated that plasma lipidomic signatures effectively distinguish individuals with severe obesity from non-obese controls (

Figure 1B).

Figure 2 presents box plots and heatmaps illustrating differences in lipid subclass concentrations and highlighting the lipid species showing the greatest variation within each subclass. Notably, individuals with severe obesity showed a marked reduction in bile acids and cholesteryl esters within the sterol lipid subclass, suggesting disruptions in bile acid circulation. Differentially abundant lipids are ranked by statistical significance in

Supplementary Table S1. Volcano plots and hierarchical cluster analysis further confirm distinct lipidomic profiles at the species level (

Figure 1C), supported by variable importance in projection (VIP) scores (

Supplementary Figure S2A), which identify the most discriminative lipid species. Several of these, particularly those involving polyunsaturated fatty acids and eicosanoid metabolism, such as adrenic, 11,14-eicosadienoic, and linoleic acids, show promise as binary classifiers (

Figure 1C). Overall, the pronounced remodelling of circulating lipid profiles in severe obesity underscores underlying oxidative, inflammatory, and mitochondrial stress, pointing to wide-ranging biological consequences.

3.3. Extensive Weight Loss Causes Dynamic Changes in the Circulating Lipidome

Complementing the clinical observations in patients who underwent LSG (

Table 1,

Supplementary Figure S1), the lipid changes observed after one year reflect a significant shift in lipidomics toward a healthier metabolic state. Fatty acyls and glycerolipids, which were elevated in obese patients compared to controls (

Figure 1A), tended to normalise after weight loss. In contrast, glycerophospholipids and sterol lipids, initially reduced, showed a tendency to increase (

Figure 3A).

Supplementary Figure S3 displays box plots and heatmaps that depict variations in lipid subclass concentrations and emphasise the lipid species with the most pronounced changes within each subclass. The volcano plot in

Figure 3B highlights the five most significantly altered lipid species after LSG based on fold change and p-values. These include reduced levels of the fatty acids linolenic, palmitic, and palmitoleic acids, alongside increased levels of the glycerophospholipid lysophosphatidylcholine and the carnitine ester glutaconyl carnitine. Our results from the PLS-DA indicate that lipid profiles can effectively distinguish patients following weight loss, with differences in fatty acids playing a primary role in this differentiation (

Figure 3C).

The results presented in

Supplementary Table S1 further support and expand these findings. Following surgery, we observed a significant reduction in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which serve as precursors to eicosanoids, suggesting a decrease in chronic low-grade inflammation. Reductions in saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, including palmitic, myristic, and oleic acids, point to diminished hepatic lipid synthesis. Weight loss also reversed the accumulation pattern of several acylcarnitines, indicating enhanced mitochondrial efficiency and reduced lipotoxicity. The restoration of lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) and lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPEs) reflects improved phospholipid turnover, which may contribute to normalised lipoprotein metabolism. Moreover, decreased levels of sphingomyelin (SM) and complex triglycerides suggest a reduction in lipid storage and lipotoxic intermediates, supporting systemic metabolic recovery, improved insulin sensitivity, and a lower cardiometabolic risk profile. Finally, the analysis of VIP scores (

Supplementary Figure S2B), the actual values presented in

Supplementary Table S1, and the ROC curves (

Figure 3D) have identified linolenic acid, LPC 20:0-sn1, and glutaconyl carnitine as potential markers for assessing the metabolic benefits of significant weight loss.

3.4. Lipidomic Signatures Indicate Persistent Dysregulation After Weight Loss

Despite substantial improvements following weight loss, the circulating lipidome does not completely revert to the profile of the non-obese cohort (

Figure 4). Our results support the idea that LSG leads to systemic metabolic recovery; however, PLS-DA indicates residual differences (

Figure 4A). These differences may be partly explained because patients who underwent surgery remain classified as obese (

Table 1). Our findings highlight qualitative changes that suggest that metabolic reprogramming is still in progress. The distribution of glycerolipids remained nearly identical between the two groups, while plasma bile acids levels were either decreased or returned to near-normal levels (

Supplementary Figure S4). Additionally, there was considerable variability in other lipid classes (

Supplementary Table S1,

Supplementary Figure S4). The bubble and volcano plots show that most differentially abundant lipid species following weight loss were downregulated, although some were significantly upregulated (

Figure 4B and C). The differences observed in glycerophospholipids, including phosphatidylcholines (PCs), ether-linked PCs, and LPEs, indicate ongoing disruptions in phospholipid remodelling and biosynthesis. These disruptions, as well as those shown in

Supplementary Table S1, suggest persistent alterations in membrane integrity and lipid-mediated signalling, particularly in specific species such as PC 36:2, PC 36:3e, PC 34:2, and LPE 22:4-sn2. We noted a decrease in sphingomyelins, such as SM 41:1, SM 41:2, and SM 39:1, indicating a delayed normalisation of sphingolipid pathways, which may be related to effects on membrane dynamics. Remarkably, adrenic acid and oxylipins levels, like 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) and 9,12,13-trihydroxy-10-octadecenoic acid (9,12,13-TriHOME), were elevated compared to those in the controls, indicating adaptive immune remodelling in a context of residual systemic inflammation. The lower circulating concentration of octanoyl carnitine after weight loss suggests a reduced accumulation of intermediates in mitochondrial β-oxidation. The actual concentrations listed in

Supplementary Table S1 and the calculated VIP scores shown in

Figure S2C highlight potential candidates for assessing variability. According to the ROC curves, plasma levels of 12-HETE, SM 41:1, and SM 36:2 may serve as biomarkers for partial normalisation, as illustrated in

Figure 4D. These comparisons suggest that specific metabolic pathways remain partially dysregulated after surgery. Alternatively, a previous metabolic history may limit the complete restoration of metabolism, requiring longer-term adaptation.

3.5. Residual Dysregulation Supports the Use of Lipidomic Biomarkers for Prediction of Outcomes and Long-Term Follow-Up

Despite achieving a healthier lipid profile, LSG does not entirely reverse the lipid changes associated with severe obesity in all patients. The lipidomic profiles of patients who have lost weight fall between those of individuals with severe obesity and non-obese controls. Our findings reveal different expression patterns of lipid species across all three groups, highlighting distinct clustering patterns (

Figure 5). This analysis underscores the metabolic disruption caused by severe obesity and the partial normalisation achieved through weight loss interventions. However, patient responses were not uniform. When comparing total and partial responders, we found that total responders had significantly lower baseline body weight and experienced greater postoperative weight loss. They also exhibited a trend toward higher statin use (

Supplementary Table S2). Notably, despite comparable conventional biochemical parameters, the two groups displayed distinct lipidomic profiles. These findings suggest that routine clinical measurements may fail to capture key alterations in underlying metabolic pathways and suggest the use of biomarkers to consider additional therapeutic interventions.

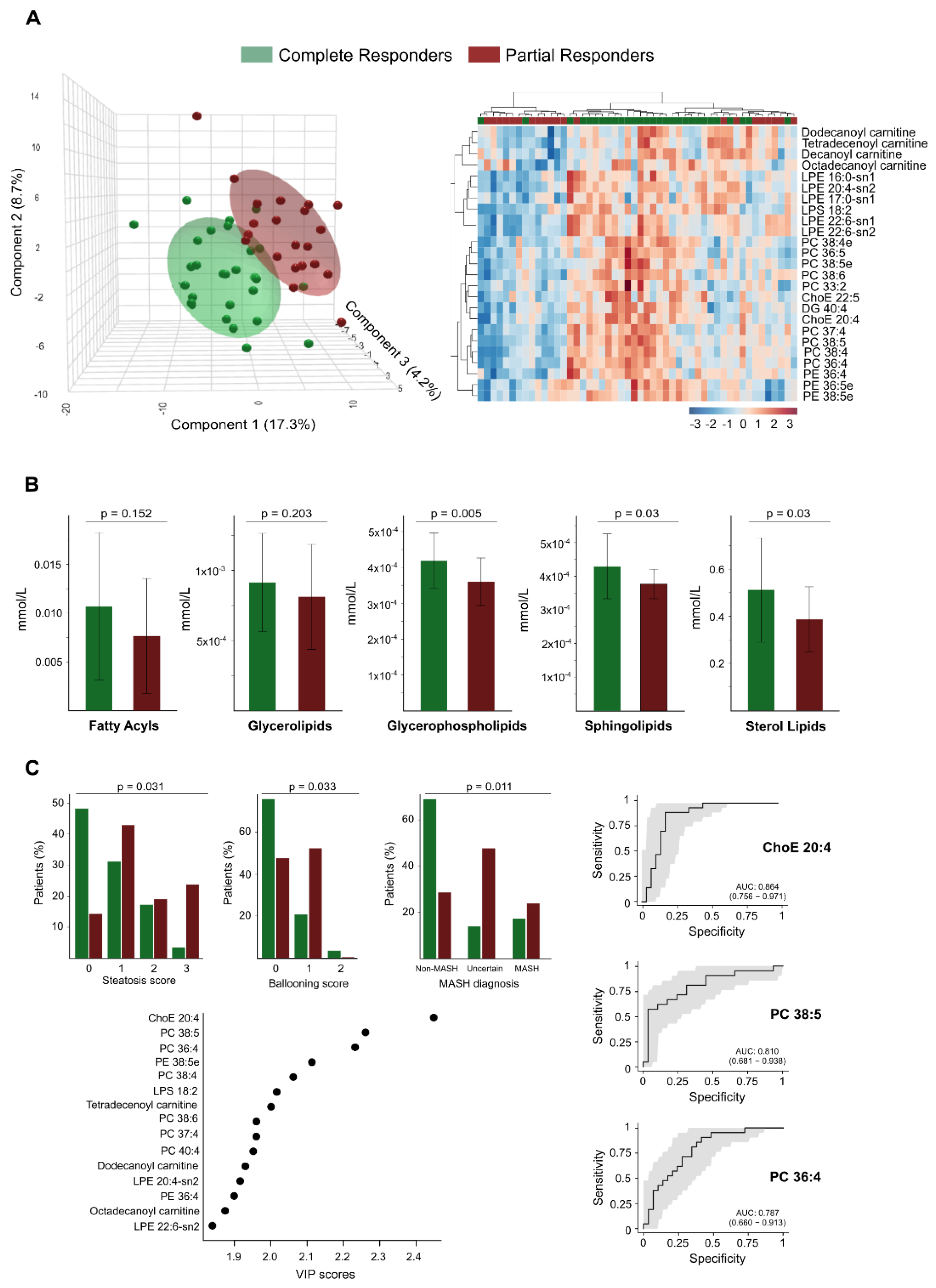

Through PLS-DA and hierarchical cluster analysis of the circulating lipidome profile, we were able to differentiate between the two groups at this follow-up stage (

Figure 6A). We identified significant differences in plasma concentrations of 68 lipid species between the groups, with higher concentrations found in total responders (

Supplementary Table S3). Notably, we observed no differences in the concentrations of circulating fatty acids between the groups; we found the most significant differences in glycerophospholipids. The levels of the glycerolipid diacylglycerol (DG) 40:4 were also higher among total responders (

Supplementary Table S3). Greater BMI reduction was also associated with milder baseline liver damage; steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis diagnosis were less frequent among responders (

Figure 6C). These findings align with the lower prevalence of risk-associated polymorphisms in total responders, specifically in genes linked to obesity (FTO), liver injury (PNPLA3), and cardiometabolic risk (TRIB1AL), as shown in

Supplementary Figure S5. Further analysis using VIP scores identified several lipid species, such as the cholesteryl arachinodate (ChoE 20:4), PC 38:5, and PC 36:4, as effective discriminators between total and partial responders. ROC curve analysis confirmed their predictive potential, with AUC values of 0.86, 0.81, and 0.79, respectively (

Figure 6C).

4. Discussion

Our study offers valuable insights into the dynamic changes in lipid homeostasis after one year of management and follow-up in patients with severe obesity. We emphasise that treatment should focus on achieving metabolic normalisation rather than solely on weight loss. Some patients may continue to experience dysregulation in specific metabolic pathways. Our findings suggest that lipidomic markers can help in the early identification of individuals who are not responding optimally.

Our observations align with the concept of lipid-induced chronic, low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress [

37,

38]. Specifically, we found a strong association between severe obesity and plasma levels of cis-7,10,13,16-docosatetraenoic acid, commonly known as adrenic acid. Its catabolism, through both enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions, produces lipid derivatives with distinct biological effects on inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death [

39]. We also observed significant increases in the levels of cis-palmitoleic acid, palmitic acid, and oleic acid among patients with severe obesity. These results suggest the presence of lipotoxicity and changes in de novo lipogenesis [

40]. In particular, palmitic acid, a saturated fatty acid, may contribute to insulin resistance and promote inflammatory pathways through various mechanisms [

41]. The lipid profile of patients with severe obesity shows a significant reduction in glycerophospholipids. Coupled with elevated levels of circulating fatty acids, this likely leads to impaired membrane remodelling. As a result, the biophysical properties of cells are affected, disrupting lipoprotein secretion and insulin sensitivity [

21,

42,

43,

44]. Given this context, the metabolic pathway of linolenic acid could be a promising therapeutic target. Animal studies have demonstrated that diet can modulate these lipid changes [

45,

46]. Although similar studies in humans are more complex, lipidomics and related immunosensing methods [

47] may eventually serve as clinical tools for monitoring responses.

Weight loss following surgery results in a reduction of harmful lipid accumulation in plasma, confirming the pathogenic importance of dysfunctions in lipid fuel metabolism [

19,

48]. Specifically, fatty acids were significantly decreased, and glycerophospholipid species were restored, suggesting attenuated inflammation and improved membrane remodelling and lipid signalling. Similarly, lower levels of circulating sphingolipids and carnitines were revealed to enhance metabolic flexibility and reduce lipid storage. Our findings suggest that these lipid changes serve as biomarkers for metabolic recovery and reduced cardiovascular risk in patients [

49,

50,

51]. A key finding of this study is that the circulating lipid profile does not completely revert to that of non-obese controls after a decrease in BMI. The lipidomic profiles can provide biomarkers to assess residual inflammation or adaptive immune remodelling, indicating an incomplete return to homeostasis [

18,

52,

53]. Furthermore, the lower abundance of SMs in plasma is associated with a healthier composition of low-density lipoprotein and very low-density lipoprotein particles [

54].

One strength of this study is the comparison of patients with differing outcomes. There is a need for further research into the mechanistic links between the benefits of weight loss and the significant changes in the circulating lipidome. In our patient population, we found a correlation between higher BMI and notable liver damage, as well as a poorer lipidomic response. This finding highlights the importance of prioritising liver health and implementing early interventions to prevent complications. The potential impact of gene variants is significant and deserves further investigation. The elevated levels of cholesteryl arachidonate in total responders indicate improved reverse cholesterol transport and enhanced restoration of lipoprotein metabolism. Conversely, lower levels in partial responders could reflect persistent hepatic steatosis. Similarly, increased concentrations of glycerophospholipids such as PC 38:5, PC 36:4, and PE 38:5e in responders suggest active membrane remodelling, improved mitochondrial function, and enhanced lipid utilisation. In contrast, reduced levels in partial responders indicate impaired metabolic flexibility. Lower diacylglycerol (DG) concentrations observed in partial responders may reflect altered lipid storage or impaired lipolysis, potentially due to residual insulin resistance or deficient adipose tissue remodelling after surgery. Alternatively, higher DG levels in responders could be indicative of transient fat mobilisation. Overall, these lipidomic alterations point to disruptions in lipid transport mechanisms, possibly linked to changes in high-density and low-density lipoprotein composition, which may have implications for cardiovascular risk assessment [

55].

This study has several limitations. As it is an exploratory pilot study, our findings need to be validated in larger and more diverse cohorts. To enhance causal inference, we will apply Mendelian randomization in future research designs. Additionally, to improve our methods, we will reassess the selection of lipid species to ensure we do not overlook subtle but important changes in lipid profiles. Future studies should also consider longer-term metabolic adaptations and investigate the effects of other bariatric surgeries.

5. Conclusions

In summary, an integrative analysis of lipidomic and clinical markers shows that lipidomics can be a valuable tool for distinguishing between different metabolic outcomes and redefining success in weight loss. This discovery paves the way for more precise treatment of severe obesity. Future studies will focus on translating the biomarker-guided strategy we propose into accessible diagnostic tools, ultimately improving patient outcomes beyond traditional metrics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Representative computed tomography images of study cohorts; Figure S2: Top discriminant lipid species across study group comparisons; Figure S3: Weight loss results in significant changes in lipid class composition; Figure S4: Lipidomic differences between patients with severe obesity after weight loss and the control group; Figure S5: Distribution of alleles among selected genotypes in partial and complete responders; Table S1: Detailed results from the circulating lipidomics analyses, comparing cohorts 1, 2, and 3, and including only those lipids with a fold change ≥ 1.5 and a p-value < 0.05.. Table S2: Clinical, biochemical, and treatment characteristics of total and partial responders to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; Table S3: Detailed results from the circulating lipidomics analyses, comparing complete and partial responders, and including only those lipids with a p-value < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven; Data curation, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven; Formal analysis, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu; Funding acquisition, Antonio Zorzano and Jorge Joven; Investigation, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Vicente Cambra-Cortés, Andrea Jiménez-Franco, Anna Hernandez, David Parada and Francesc Riu; Methodology, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Vicente Cambra-Cortés, Andrea Jiménez-Franco, Anna Hernandez, David Parada and Francesc Riu; Project administration, Jorge Joven; Resources, Antonio Zorzano and Jorge Joven; Software, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Vicente Cambra-Cortés and Andrea Jiménez-Franco; Supervision, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven; Validation, Antonio Zorzano, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven; Visualization, Jorge Joven; Writing – original draft, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven; Writing – review & editing, Alina-Iuliana Onoiu, Antonio Zorzano, Jordi Camps and Jorge Joven. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LA CAIXA FOUNDATION (Barcelona, Spain), grant number HR21-00430 and the INSTITUTO DE SALUD CARLOS III (Madrid Spain) cofunded by the European Union, grant numbers PI18/00921, PI21/00510 and PI24/01146.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of INSTITUT D’INVESTIGACIÓ SANITÀRIA PERE VIRGILI (protocol codes EPIMET PI21/00510_083, PL4NASH112/2021, and EOM 244/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results..

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| DG |

Diacylglycerol |

| FDR |

False discovery rate |

| HETE |

Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| HOME |

Hydroxyoctadecenoic acid |

| LPC |

Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| LPE |

Lysophosphatidylethanolamine |

| LSG |

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

| PC |

Phosphatidylcholine |

| PLS-DA |

Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| QTOF |

Quadruploe-time-on-flight mas spectrometry |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SM |

Sphingomyelin |

| SNP |

Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| UHPLC |

Ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography |

| VIP |

Variable importance in projection |

References

- Ellison-Barnes, A.; Johnson, S.; Gudzune, K. Trends in obesity prevalence among adults aged 18 through 25 years, 1976-2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2073–2074.

- UN, World Population Prospects. World Population Prospects 2024, Online Edition. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2024. https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A., et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Hernández-Aguilera, A., et al. Plasma metabolic alterations in patients with severe obesity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 374–387. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 706978. [CrossRef]

- Cypess, A.M. Reassessing human adipose tissue. New Eng. J. Med. 2022, 386, 768–779. [CrossRef]

- Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Results. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2024. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Joven, J.; Micol, V.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Alonso-Villaverde, C.; Menéndez, J.A. Polyphenols and the modulation of gene expression pathways: can we eat our way out of the danger of chronic disease? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 985–1001. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Modica, S.; Dong, H.; Wolfrum, C. Plasticity and heterogeneity of thermogenic adipose tissue. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 751–61. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sharma, A.K.; Wolfrum, C. Novel insights into adipose tissue heterogeneity. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Korf, H.; Vidal-Puig, A. An adipocentric perspective on the development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 1048–1062. [CrossRef]

- Carobbio, S.; Pellegrinelli, V.; Vidal-Puig, A. Adipose tissue dysfunction determines lipotoxicity and triggers the metabolic syndrome: Current challenges and clinical perspectives. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1460, 231–272. [CrossRef]

- Aronne, L.J.; Horn, D.B.; le Roux, C.W.; Ho, W.; Falcon, B.L.; Gomez Valderas, E., et al. Tirzepatide as compared with semaglutide for the treatment of obesity. New Engl. J. Med. 2025, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Chapski, D.J.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Hernández-Aguilera, A., et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with severe obesity restores adaptive responses leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7830. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Fibla, M., et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy reverses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolism 2019, 99, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Magkos, F.; Klein, S. Effects of bariatric surgery on glucose homeostasis and type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 897–912. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Franco, A.; Castañé, H.; Martínez-Navidad, C.; Placed-Gallego, C.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Fernández-Arroyo, S., et al. Metabolic adaptations in severe obesity: Insights from circulating oxylipins before and after weight loss. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 246–258. [CrossRef]

- Sinturel, F.; Chera, S.; Brulhart-Meynet, M.C.; Montoya, J.P.; Lefai, E.; Jornayvaz, F.R., et al. Alterations of lipid homeostasis in morbid obese patients are partly reversed by bariatric surgery. iScience 2024, 27, 110820. [CrossRef]

- Ruperez, C.; Madeo, F.; de Cabo, R.; Kroemer, G.; Abdellatif, M. Obesity accelerates cardiovascular ageing. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2161–2185. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastián, D.; Vives, S.; Ivanova, S.; Bartoccioni, P.; Kakimoto, P., et al. Deficient endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine transfer causes liver disease. Cell 2019, 177, 881–895. [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Park, Y.S.; Cho, C.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Park, D.J., et al. Short-term changes in the serum metabolome after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 71. [CrossRef]

- Kayser, B.D.; Lhomme, M.; Dao, M.C.; Ichou, F.; Bouillot, J.L.; Prifti, E., et al. Serum lipidomics reveals early differential effects of gastric bypass compared with banding on phospholipids and sphingolipids independent of differences in weight loss. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 2017, 41, 917–925. [CrossRef]

- Cabré, N.; Gil, M.; Amigó, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S., et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy alters 1H-NMR-measured lipoprotein and glycoprotein profile in patients with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11: 1343. [CrossRef]

- Köfeler, H.C.; Eichmann, T.O.; Ahrends, R.; Bowden, J.A.; Danne-Rasche, N.; Dennis, E.A., et al. Quality control requirements for the correct annotation of lipidomics data. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4771. [CrossRef]

- Castañé, H.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Herrero, P., et al. Coupling machine learning and lipidomics as a tool to investigate metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. A general overview. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 473. [CrossRef]

- Castañé, H.; Jiménez-Franco, A.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Martínez-Navidad, C.; Cambra-Cortés, V.; Onoiu, A.I., et al. Multi-omics profiling reveals altered mitochondrial metabolism in adipose tissue from patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. EBioMedicine 2025, 111, 105532. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, N.; Camps, J.; Fernandez-Ballart, J.; Arija, V.; Ferre, N.; Tous, M., et al. Diet and lifestyle are associated with serum C-reactive protein concentrations in a population-based study. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2005, 145, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, R.A.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Castañé, H.; Jiménez-Franco, A.; Joven, J.; Burks, D.J., et al. Landscape of sex differences in obesity and type 2 diabetes in subcutaneous adipose tissue: a systematic review and meta-analysis of transcriptomics studies. Metabolism 2025, 168, 156241. [CrossRef]

- Cornier. M.A. A review of current guidelines for the treatment of obesity. Am. J. Manag. Care 2022, 28(15 Suppl), S288–S296. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [CrossRef]

- Onoiu, A.I.; Domínguez, D.P.; Joven, J. Digital pathology tailored for assessment of liver biopsies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 846. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, X.; Kuppa, A.; Feitosa, M.F.; Bielak, L.F.; O'Connell, J.R. et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies 17 loci associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1640–1650. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; de Vries, M.A.; Burggraaf, B.; van der Zwan, E.; Pouw, N. et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on the postprandial lipid profile in obese patients: A non-targeted lipidomics study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1194. [CrossRef]

- Foguet-Romero, E.; Samarra, I.; Guirro, M.; Riu, M.; Joven, J.; Menendez, J.A. et al. Optimization of a GC-MS injection-port derivatization methodology to enhance metabolomics analysis throughput in biological samples. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2555–2565. [CrossRef]

- Köfeler, H.C.; Ahrends, R.; Baker, E.S.; Ekroos, K.; Han, X.; Hoffmann, N. et al. Recommendations for good practice in MS-based lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100138. [CrossRef]

- Dowgiałło-Gornowicz, N.; Wityk, M.; Lech, P. Staying on track: Factors influencing 10-year follow-up adherence after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2025, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, S.; Helmiö, M.; Juuti, A.; Tiusanen, R.; Hurme, S.; Löyttyniemi, E. et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs roux-en-y gastric bypass on weight loss and quality of life at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 137–146. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.Y.; Lin, X.; Xu, F.; Shan, S.K.; Guo, B.; Li, F.X. et al. Ferroptosis and its potential role in metabolic diseases: A curse or revitalization? Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 701788. [CrossRef]

- Domagalski, M.; Simiczyjew, A.; Kot, M.; Skoniecka, A.; Tymińska, A.; Pikuła, M. et al. Response of primary human adipocytes to fatty acid treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70622. [CrossRef]

- Riera-Borrull, M.; Cuevas, V.D.; Alonso, B.; Vega, M.A.; Joven, J.; Izquierdo, E. et al. Palmitate conditions macrophages for enhanced responses toward inflammatory stimuli via JNK activation. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3858–3869. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tontonoz, P. Phospholipid remodeling in physiology and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 165–188. [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Wang, B.; Dunham, M.M.; Hedde, P.N.; Wong, J.S.; Gratton, E. et al. Lpcat3-dependent production of arachidonoyl phospholipids is a key determinant of triglyceride secretion. Elife 2015, 4, e06557. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.J.; Rong, X.; Maschek, J.A.; Verkerke, A.R.; Siripoksup, P.; Song, H et al. Lysophospholipid acylation modulates plasma membrane lipid organization and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 131, e135963. [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.M.; Bellenger-Germain, S.H.; Engler, M.B.; Narce, M.M.; Poisson, J.P. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid affects stearic acid desaturation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Lipids 2000, 35, 1011–1015. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.G.; Song, Z.X.; Yin, H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Shu, G.F.; Lu, H.X. et al. Low n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio improves lipid metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial function in rats using plant oils as n-3 fatty acid source. Lipids 2016, 51, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel, V.; Iftimie, S.; Montero-Calle, A.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Castro, A. et al. Contributing to the management of viral infections through simple immunosensing of the arachidonic acid serum level. Mikrochim. Acta 2024, 191, 369. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Tanriverdi, K.; Iafrati, M.D.; Mosley, J.D.; Freedman, J.E.; Ferguson, J.F. Characterization of the plasma metabolome and lipidome in response to sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgeries reveals molecular patterns of surgical weight loss. Metabolism 2024, 158, 155955. [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Gutaj, P.; Plewa, S.; Spasenenko, I.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Krasińska, B. et al. Obesity and acylcarnitine derivates interplay with coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15676. [CrossRef]

- Vianello, E.; Ambrogi, F.; Kalousová, M.; Badalyan, J.; Dozio, E.; Tacchini, L. et al. Circulating perturbation of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) is associated to cardiac remodeling and NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular patients with insulin resistance risk. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2024, 137, 104895. [CrossRef]

- Grapov, D.; Fiehn, O.; Campbell, C.; Chandler, C.J.; Burnett, D.J.; Souza, E.C. et al. Impact of a weight loss and fitness intervention on exercise-associated plasma oxylipin patterns in obese, insulin-resistant, sedentary women. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14547. [CrossRef]

- Pauls, S.D.; Du, Y.; Clair, L.; Winter, T.; Aukema, H.M.; Taylor, C.G. et al. Impact of age, menopause, and obesity on oxylipins linked to vascular health. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 883–897. [CrossRef]

- Barrachina, M.N.; Hermida-Nogueira, L.; Moran, L.A.; Casas, V.; Hicks, S.M.; Sueiro, A.M. et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis of platelets in severe obesity uncovers platelet reactivity and signaling pathways alterations. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 478–490. [CrossRef]

- Dashti, M.; Kulik, W.; Hoek, F.; Veerman, E.C.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Rezaee, F. A phospholipidomic analysis of all defined human plasma lipoproteins. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 139. [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E.; van Dorsten, F.A.; Troost, J.; Paliukhovich, I.; van Velzen, E.J.; Hendriks, M.M. et al. A lipidomic analysis approach to evaluate the response to cholesterol-lowering food intake. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 894–906. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).