1. Introduction

Wakatobi Regency, Indonesia, is a nationally strategic region rich in marine biodiversity and cultural heritage. (1,2), but its tourism management still faces various challenges in achieving decent work and inclusive economic growth in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Eight (3,4). Policy formulation remains top-down with low community participation (5), labor conditions tend to be informal and seasonal (6), and institutional coordination is weak (7). Additionally, environmental impacts caused by unsustainable tourism practices, particularly in coastal areas, further hinder the long-term sustainability of this sector (8).

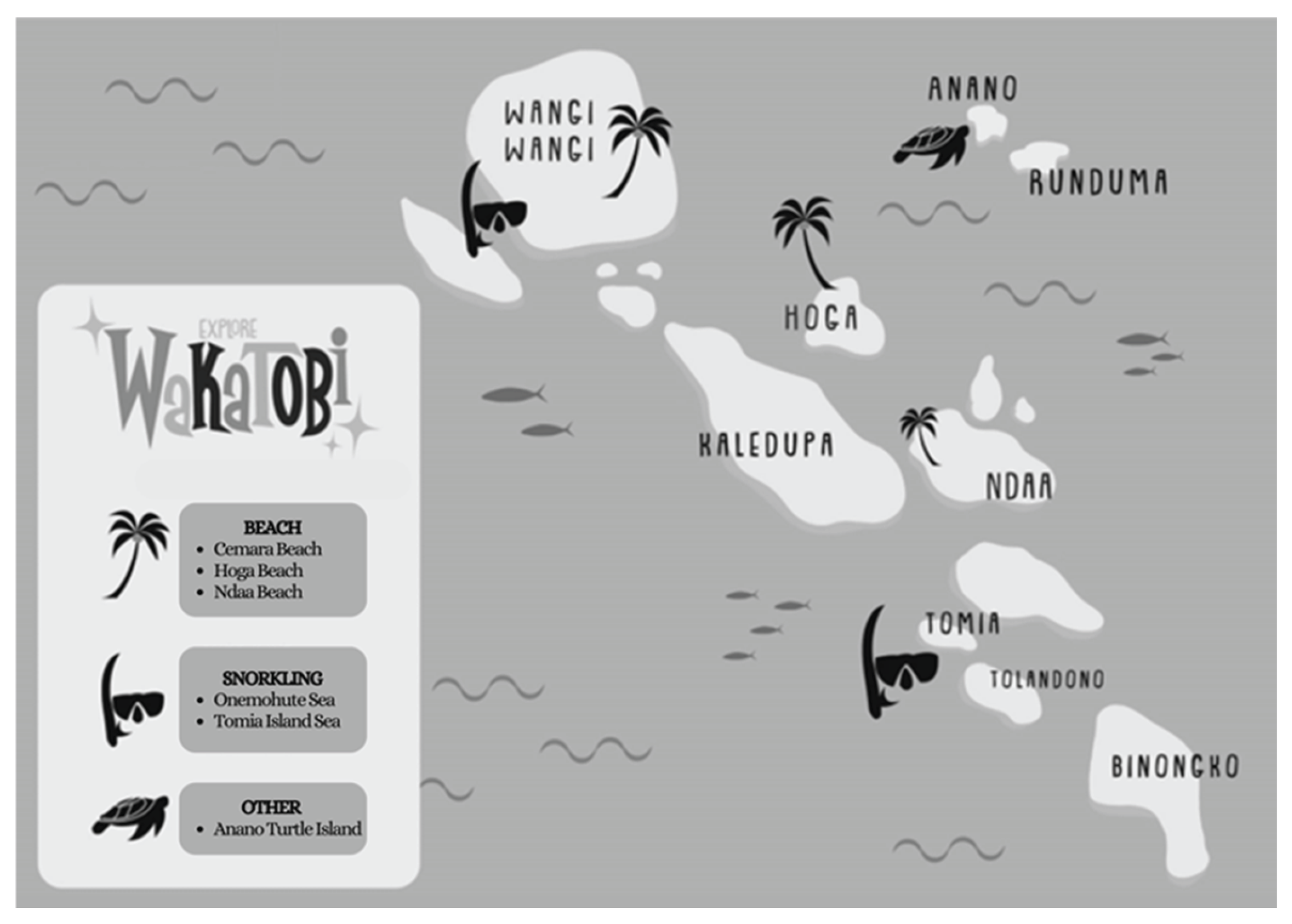

Figure 1 illustrates the geographic layout of Wakatobi Regency, comprising four main islands Wangi-Wangi, Kaledupa, Tomia, and Binongko—which form a strategic coastal and marine corridor in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. The map highlights the region’s status as both a national park and a designated super-priority tourism area. Its ecological richness, including coral reefs and endemic marine species, underscores the importance of integrated spatial planning in tourism governance. Understanding this geographic context is essential for analyzing spatial disparities in infrastructure, employment distribution, and community access to tourism benefits.

To strengthen governance and support the achievement of SDG Eight, several solutions have been proposed: encouraging multi-stakeholder participation in tourism governance (10), developing green infrastructure and environmentally friendly accommodation (11), and enhancing community capacity through training and human resource development (12). The integration of innovative policies based on digital technology and participatory approaches is expected to bridge the gap between planning and implementation. By prioritizing workforce development and environmental resilience, Wakatobi has the potential to become a local model for implementing global development goals.

The implementation of SDG Eight in Wakatobi, which emphasizes sustainable economic growth and decent work, still faces structural challenges in its tourism sector. Although this region has been designated a super-priority destination and boasts high ecological wealth, its tourism management strategy remains incomplete and lacks community participation and environmental sustainability (5,6). Economic benefits are not evenly distributed due to limited access to financial institutions, technological support, and regulations that do not favor local communities (13). Additionally, pressure on the environment and cultural heritage reinforces the urgency for more inclusive and sustainable governance (14).

In this context, several research and institutional gaps are highlighted. There are no comprehensive indicators to measure the effectiveness of green economic policies in Wakatobi (5), while the roles of institutions such as the BOP, TNW, and local government tend to be fragmented, leading to conflicts over access and authority (15,16). Key questions that need to be addressed include: How is SDG Eight applied in the context of Wakatobi tourism?; What is the configuration of tourism policies and institutions in this region?; How is the model of sustainable tourism governance implemented regionally?; and How can tourism job creation strategies be optimized at the local level?

Previous studies have highlighted various dynamics: from evaluations of tourism policies and the green economy (5,6), the socio-ecological impacts of ecotourism practices (16), the dominance of institutional actors and regulatory conflicts [

8], to the challenges of community involvement in tourism marketing (13). This study is important as a basis for developing an adaptive governance model based on local empowerment. A collaborative approach and strengthening community social capital are considered potential strategies in promoting governance transformation towards sustainability and economic justice (10,16).

This research focuses on the development of sustainable tourism in Indonesia through participatory approaches, collaborative governance, and environmental conservation to promote economic growth and decent employment. Its objectives include: analyzing sustainable tourism practices (14,17), exploring the role of community empowerment in tourism management and marketing (5,18,19), evaluating policy and institutional frameworks that support sustainable development (20–22), and examining innovative approaches such as green tourism and eco-innovation (23). The literature highlights the importance of direct community involvement in tourism marketing and management, as well as the need for policies that integrate conservation, social inclusion, and economic empowerment.

This research presents novelty through the application of a community-based strategic approach and technology in strengthening tourism governance in Indonesia. This approach emphasizes cross-sectoral policy integration, ecotourism innovation (11), and the utilization of social capital (10,18) to address economic inequality and ecological pressure. Additionally, this research highlights the Community-Based Tourism (CBT) model as an inclusive strategy that can improve local well-being (21), while aligning tourism practices with the SDGs. With this contribution, the research is relevant for policymakers and institutional actors in designing transformative strategies toward fair and sustainable tourism.

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for understanding the contribution of regional sustainable tourism governance to employment creation can be grounded in the concept of “relational work” from economic sociology (24–26). This approach emphasizes the importance of the diverse and complex relationships within small-scale tourism enterprises, which are central actors in rural labor markets (26). These enterprises facilitate job opportunities, sustained business relationships, and resilient work relationships, contributing significantly to SDG Eight (26). The framework involves analyzing the boundary work between various types of relationships in the tourism labor market, such as formal and informal, professional and personal, and marketized and non-marketized work relationships.

Another critical aspect of the theoretical framework is sustainable human resource management (HRM) (27). This approach focuses on ensuring that tourism employment is sustainable and decent, aligning with the goals of SDG Eight (28,29). Sustainable HRM involves engaging multiple stakeholders at various scales to comprehensively address the sustainability of tourism employment (30). This includes implementing policies and practices that promote decent work conditions, fair wages, and job security, essential for achieving sustainable economic growth and full employment in the tourism sector.

The governance and policy-making framework for sustainable tourism is also crucial. This framework involves understanding the complex interplay of various policy initiatives and governance structures that influence regional tourism (31,32). For instance, New South Wales, Australia's case study, highlights the importance of destination management planning as a framework to drive sustainable tourism outcomes (33). This approach ensures that tourism governance is aligned with sustainable development principles, promoting economic growth and employment while preserving environmental and cultural resources.

The CBT is an innovative approach that places local communities at the center of tourism development (34). This model aligns with SDG Eight by fostering inclusive economic growth, empowering marginalized communities, and promoting cultural and environmental sustainability (35). CBT generates sustainable livelihoods, preserves cultural heritage, and addresses governance challenges, making it a vital component of the theoretical framework for sustainable tourism governance (36,37). By involving local communities in tourism planning and decision-making, CBT ensures that the benefits of tourism are equitably distributed, contributing to employment creation and poverty alleviation.

Inclusive tourism governance is another important element of the theoretical framework (38). This approach integrates sustainable practices in the tourism sector by engaging a wide range of stakeholders, including customers, employees, investors, suppliers, and local communities (39,40). Inclusive tourism governance promotes sustainable consumption and production, responsible resource use, and inclusive economic growth, which aligns with the broader goal of sustainable development (41). This approach ensures sustainable tourism development and contributes to job creation and economic growth by fostering stakeholder collaboration.

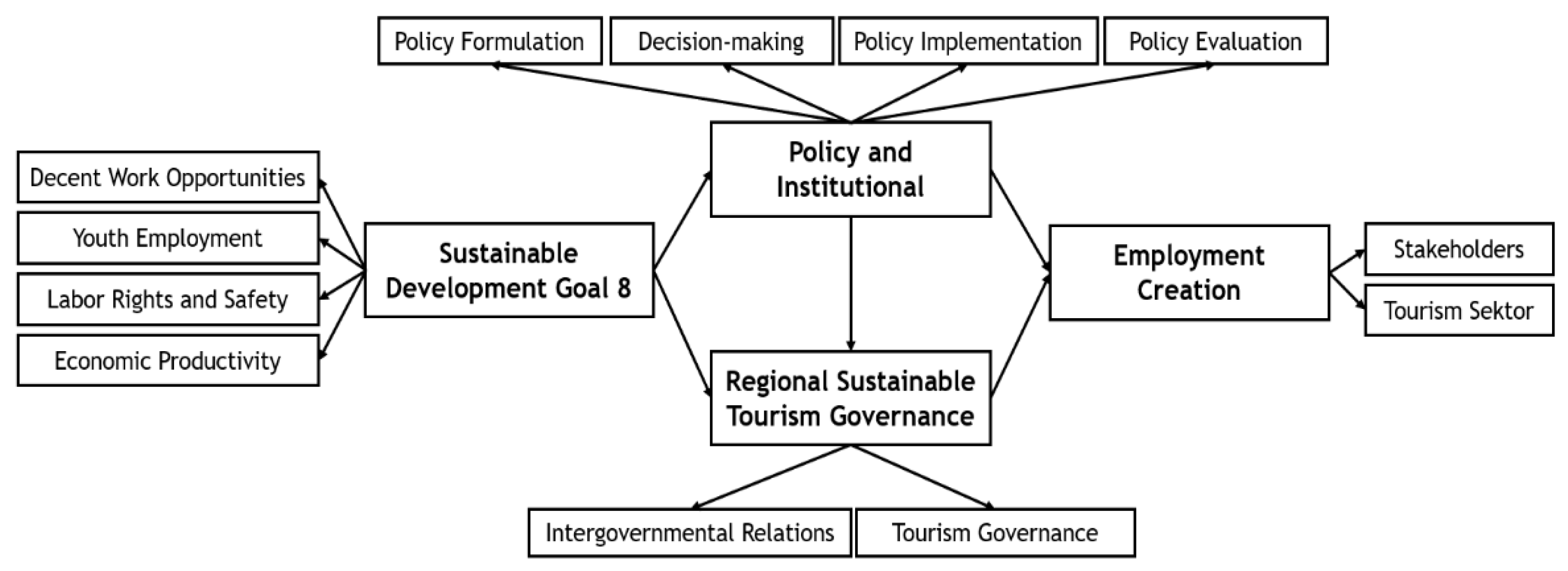

Figure 2 presents a theoretical framework that highlights the role of regional sustainable tourism governance in job creation. The framework illustrates the interrelated elements of policy-making and institutional strategies that support SDG Eight, which emphasizes decent work opportunities, youth employment, workers' rights, workplace safety, and economic productivity. The framework covers stages such as policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation and shows their implications for tourism governance. It also highlights how stakeholder engagement and active participation of the tourism sector contribute to sustainable job creation. This visual serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding how an effective governance framework can promote sustainable job creation in tourism.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Approach

This research employs a qualitative, exploratory case study approach to understand complex governance processes (42,43) and their impact on sustainable employment in tourism. The choice of qualitative methods stems from the study's aim to explore perceptions, experiences, and institutional relationships that cannot be adequately captured through purely quantitative approaches (44,45). The case study design is particularly appropriate given the need for an in-depth investigation of regional governance in a specific socio-cultural and economic context: Wakatobi, Indonesia. A qualitative case study facilitates the exploration of how policy frameworks, stakeholder interactions, and local governance mechanisms influence the capacity of tourism to generate employment that aligns with SDG Eight objectives. This approach enables the examination of contextual specificities and supports theory-building grounded in real-world dynamics.

3.2. Study Site: Wakatobi as a Strategic Case

Wakatobi is a regency located in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, comprising four main islands and designated as both a national park and a marine biodiversity hotspot. It is internationally recognized for its rich marine ecosystems and cultural heritage, making it a prime tourism destination. However, despite its potential, Wakatobi faces various socio-economic challenges, including limited employment diversification, inadequate infrastructure, and weak policy enforcement. The region’s dependence on tourism for economic development, coupled with environmental sensitivity, renders it an ideal case for examining the intersection of governance, sustainability, and employment. Wakatobi’s tourism sector involves a range of stakeholders, from local communities and tour operators to government agencies and international NGOs, creating a complex governance environment that necessitates empirical investigation.

3.3. Population and Sampling Strategy

The study population includes stakeholders who play key roles in Wakatobi’s tourism governance and employment generation. These include government officials, tourism entrepreneurs, community leaders, non-governmental organizations, and youth groups involved in tourism-related activities. Given the qualitative nature of the study, purposive sampling was employed to select participants based on their relevance to the research objectives and their ability to provide rich, experience-based insights. In total, 25 semi-structured interviews were conducted. Participants were selected to ensure representation across various sectors and governance levels. Criteria for inclusion involved (1) direct involvement in tourism planning, management, or operations; (2) a minimum of two years of experience in tourism-related roles in Wakatobi; and (3) willingness to engage in a recorded interview under informed consent protocols. Snowball sampling was also used to identify additional respondents through recommendations by initial interviewees (46,47). This method proved effective in accessing hard-to-reach stakeholders, such as informal workers and community-based tourism actors who may not be registered in official databases but hold valuable contextual knowledge.

3.4. Data Collection Methods

Data was collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews, allowing for flexibility in the questioning process while maintaining thematic consistency (48). Interview guides were developed based on the study’s theoretical framework and included questions on tourism policy implementation, governance structures, institutional barriers, stakeholder participation, and perceptions of decent work. The interviews were conducted in the Indonesian language and Wakatobi local dialects where appropriate, then transcribed and translated into English for analysis. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and was conducted in settings that ensured participant comfort and privacy. In addition to interviews, policy documents, local government reports, and tourism development plans were analyzed to triangulate data and verify claims made by respondents. Field notes were also maintained to capture non-verbal cues, environmental conditions, and researcher reflections during the fieldwork (49,50). Ethical clearance was obtained prior to fieldwork, and informed consent was secured from all participants (51). Confidentiality and anonymity were assured, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

3.5. Data Analysis Procedures

Thematic analysis was employed to systematically code and interpret qualitative data. This involved several stages:

- a)

Familiarization: Researchers thoroughly reviewed transcripts to become immersed in the data.

- b)

Initial Coding: Codes were generated using NVivo 12 Plus software, guided by both the theoretical framework and emergent themes from the interviews.

- c)

Categorization: Codes were grouped into thematic categories that aligned with the study’s research questions—namely, governance practices, employment conditions, stakeholder engagement, and policy implementation.

- d)

Pattern Recognition: Relationships and patterns across themes were identified to construct a holistic understanding of the mechanisms through which governance impacts employment.

- e)

Interpretation: Themes were analyzed in light of relevant literature to draw conclusions and formulate recommendations.

The use of NVivo 12 Plus software enhanced analytical rigor by enabling the visualization of thematic networks, frequency analysis, and co-occurrence of concepts. This software also facilitated the transparent documentation of coding decisions, increasing the reliability and replicability of the analysis (52,53).

3.6. Validity, Reliability, and Triangulation

To ensure the validity of the findings, data triangulation was applied by cross-referencing interview responses with official documents and policy reports (54). Member checking was also conducted by presenting preliminary findings to selected participants for feedback and validation. Reliability was enhanced through a clear audit trail of data collection and analysis procedures, consistent use of coding protocols, and inter-coder verification during the analysis phase. Researcher reflexivity was maintained to minimize bias, with ongoing self-assessment throughout fieldwork and analysis.

4. Results

4.1. SDG Eight in the Context of Wakatobi Tourism

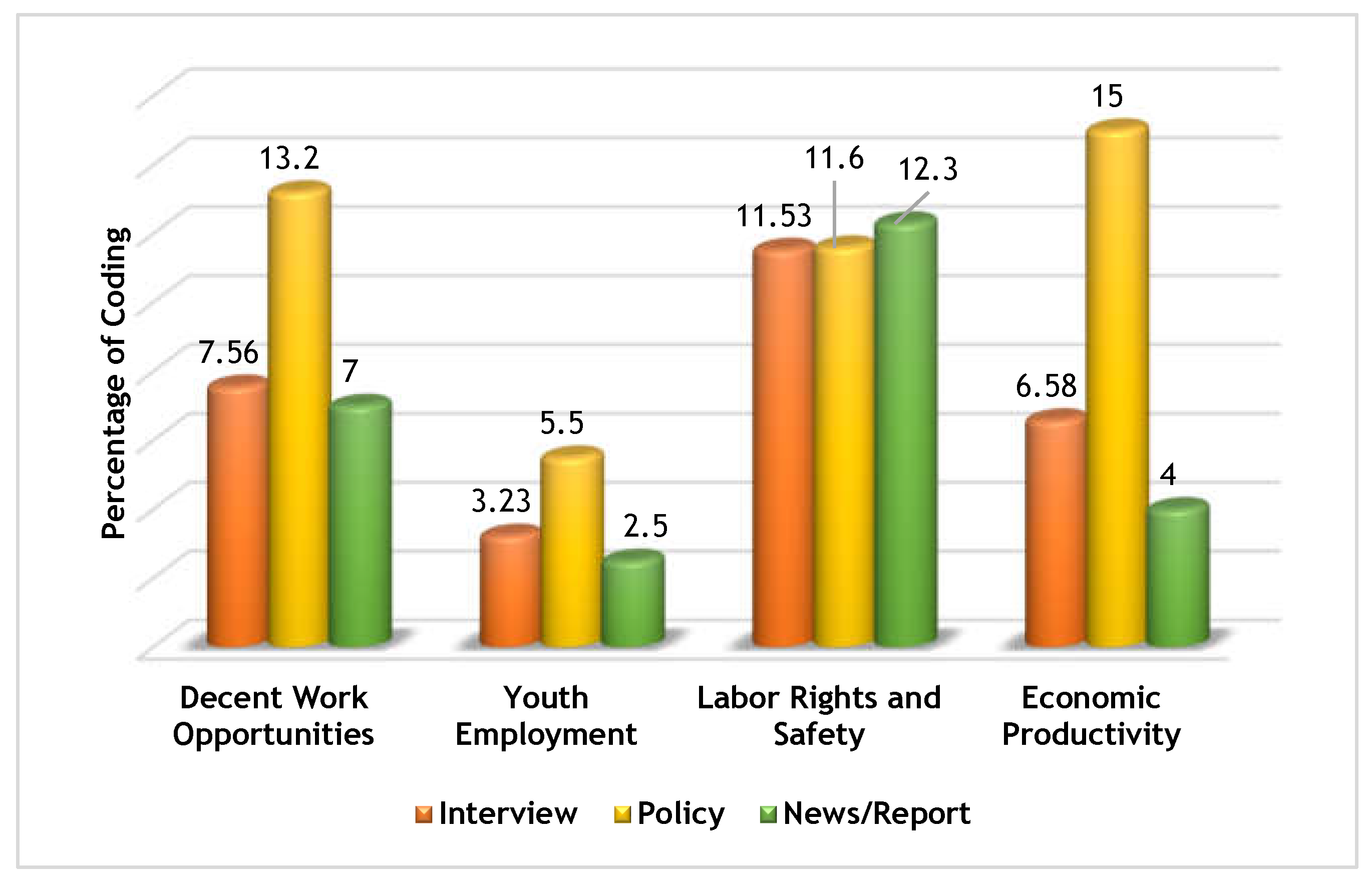

SDG Eight, in the context of tourism in local government, is an important pillar for promoting inclusive economic growth and decent work. Analyzing indicators such as decent job opportunities (28,55), youth employment (56), workers' rights and safety (57), and economic productivity (58) is crucial to ensuring that tourism contributes to the well-being of the community. Local governments must integrate principles of sustainability and social protection into their policies while establishing monitoring systems to ensure efficiency and fairness in the development of the tourism sector.

Figure 3 shows the dominance of the issue of “Workers' Rights and Safety” in the discourse on tourism in Wakatobi, reflected in the highest intensity of codes in interviews (11.53 percent) and news sources (12.3 percent). This indicates that the perceptions of field actors highlight the weak protection of informal workers and the lack of social security. The Wakatobi tourism sector is still dominated by seasonal forms of employment, without clear legal status and adequate labor protection. Although policy documents emphasize a focus on “economic productivity” (15 percent), the imbalance between economic expansion and social protection remains a critical point in the effectiveness of sustainability policies. The gap between policy narratives and practical realities highlights the limited institutional commitment to fair labor dimensions.

On the other hand, the low proportion of “Youth Employment” in interviews (3.23 percent) and news (2.5 percent) indicates that the youth segment has not yet become a strategic part of the tourism work ecosystem. However, according to (56), infrastructure development and local capacity mapping can significantly reduce youth unemployment rates. “Youth involvement should not be merely symbolic but designed as part of the framework for regional economic transformation,” as emphasized in the interview with the head of the tourism division. This disparity highlights the need for new, more progressive, and contextual policy designs, with labor interests as the core of sustainable tourism development.

4.2. Policy and Institutionalization of Tourism in Wakatobi

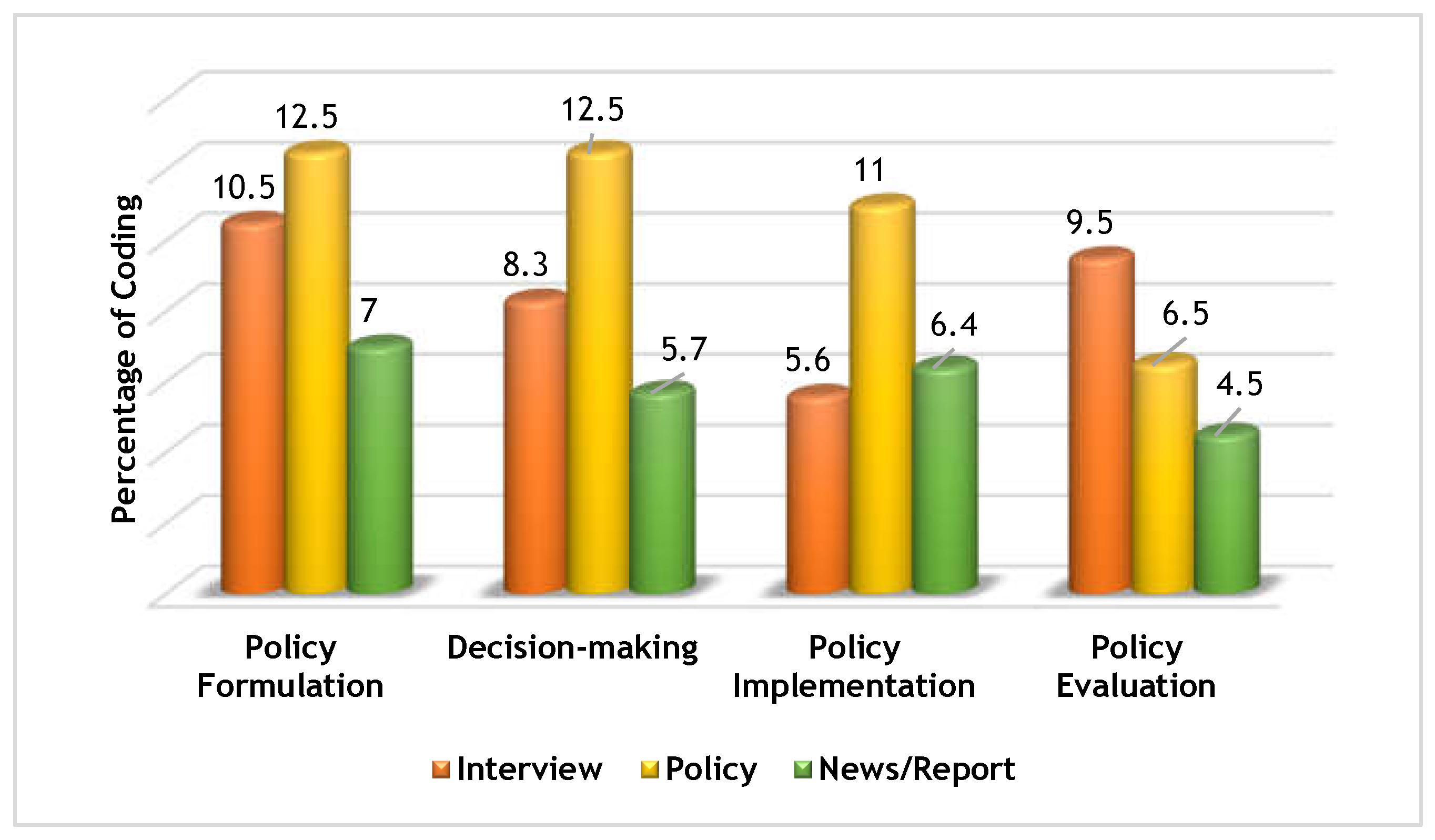

Tourism policy and institutionalization in local government require analysis of key indicators such as policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, and policy evaluation. Contextual and participatory formulation (59,60), inclusive decision-making with stakeholder involvement (61), and inter-agency coordination in implementation (62) are essential for policy effectiveness. Evaluation through governance indicators and sustainable monitoring systems (63) ensures that policies remain adaptive and relevant. This analysis strengthens responsive and sustainable tourism governance at the local level.

Figure 4 illustrates a cross-analysis of the four main components of tourism policy and institutionalization in Wakatobi: “Policy Formulation,” “Decision Making,” “Policy Implementation,” and “Policy Evaluation.” In the interview category, “Policy Formulation” (10.5 percent) and “Policy Evaluation” (9.5 percent) received high attention, indicating that field actors are more concerned about the gap between policy design and implementation. Many respondents stated that the planning process remains technocratic, “fails to adequately consider the voices of local communities,” and is not fully adaptive to the needs of marine tourism areas. Conversely, policy documents show a balanced proportion between “Formulation” and “Decision-making” (each at 12.5 percent), but “Evaluation” is only 6.5 percent, reflecting the weakness of monitoring systems and success indicators.

The discrepancy between the intensity of statements in the news (only 4.5 percent for evaluation) and the focus of formal policies indicates that the evaluation process is not a priority for the public or the media. However, according to (60), “without a system of sustainability indicators, policies easily lose their relevance.” The low proportion of “Policy Implementation” in the interviews (5.6 percent) indicates a lack of clarity in the roles of institutions in the field and coordination challenges. These findings underscore the need for a participatory governance framework, with comprehensive improvements in the evaluation and implementation stages of policies to ensure the effectiveness of sustainable tourism in Wakatobi.

4.3. Regional Sustainable Tourism Governance in Wakatobi

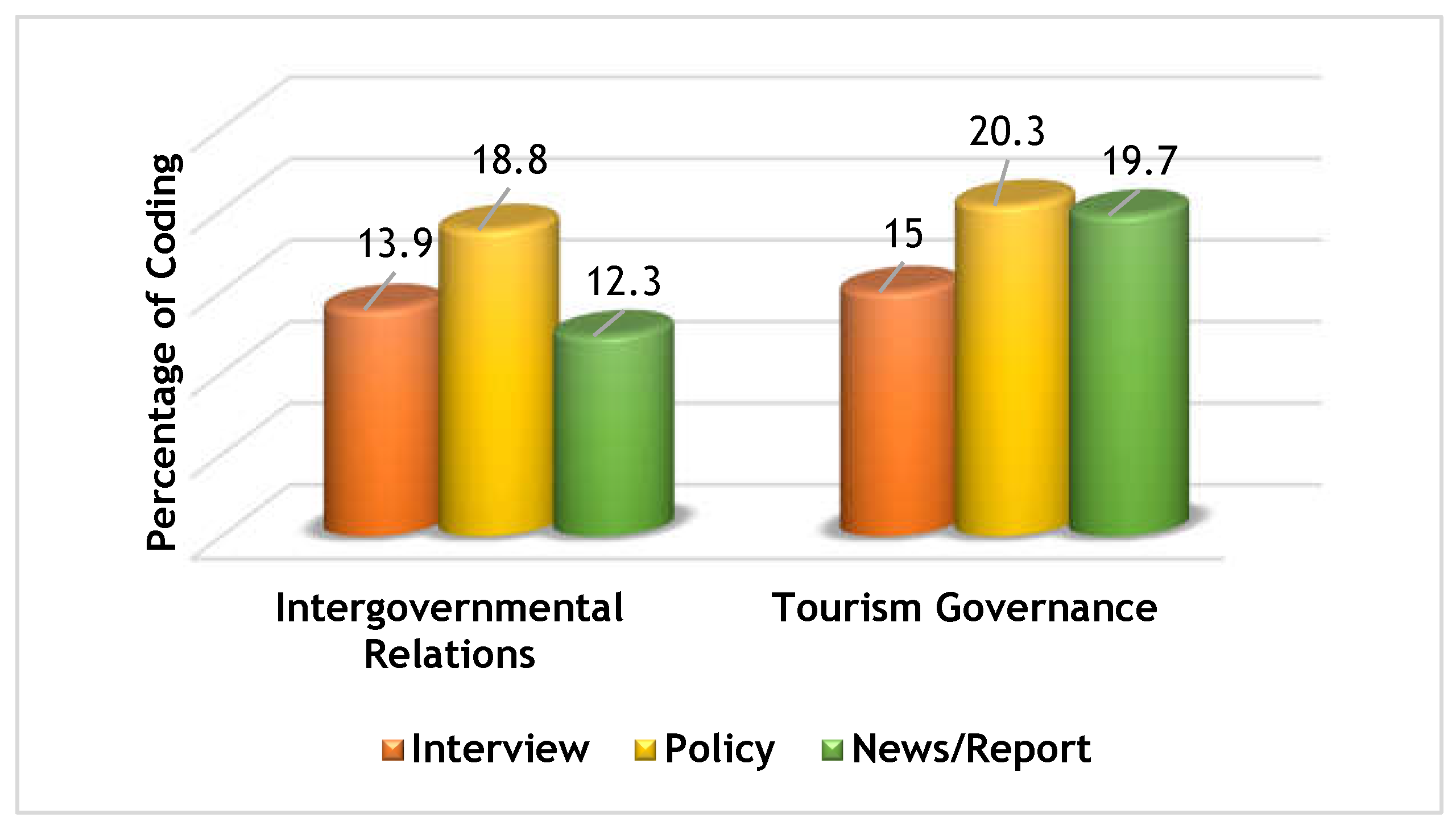

Sustainable tourism governance at the local government level requires policies that are fair, inclusive, and responsive to environmental sustainability and social welfare (64). Analysis of indicators such as intergovernmental relations is important for understanding cross-level coordination in policy formulation and implementation (65), while tourism governance indicators help identify the roles of stakeholders and the effectiveness of participatory mechanisms (31,66). By integrating these two sets of indicators, local governments can optimize strategies, enhance policy legitimacy, and strengthen accountability in the governance of sustainable tourism destinations.

Figure 5 reveals the dynamics of sustainable tourism governance in Wakatobi through a cross-analysis of two key indicators: “Intergovernmental Relations” and “Tourism Governance.” The interview categories show that “Tourism Governance” received the highest attention (15 percent), illustrating the significant attention given to the distribution of roles among actors and participatory mechanisms that are not yet functioning optimally. Many narratives from local stakeholders emphasize that inter-agency coordination often gets “stuck in sectoral egos” and lacks collaborative forums. On the other hand, policy documents show a dominance of the topics “Intergovernmental Relations” (18.8 percent) and “Tourism Governance” (20.3 percent), reflecting regulatory intentions to strengthen connectivity between levels of government, though this has not yet been fully realized in practice.

In news reports, the proportion of “Tourism Governance” reached 19.7 percent, while “Intergovernmental Relations” only accounted for 12.3 percent, indicating that governance issues receive higher public attention compared to formal institutional coordination. According to (31), effective destination governance requires “clear consensus mechanisms and distribution of responsibilities.” This imbalance shows that although the policy framework has adopted the principle of sustainability, implementation in the field still faces obstacles in intergovernmental harmonization and stakeholder engagement. Restructuring governance and strengthening inter-institutional networks are strategic steps to ensure the success of sustainable tourism in Wakatobi.

4.4. Tourism Employment Creation in Wakatobi

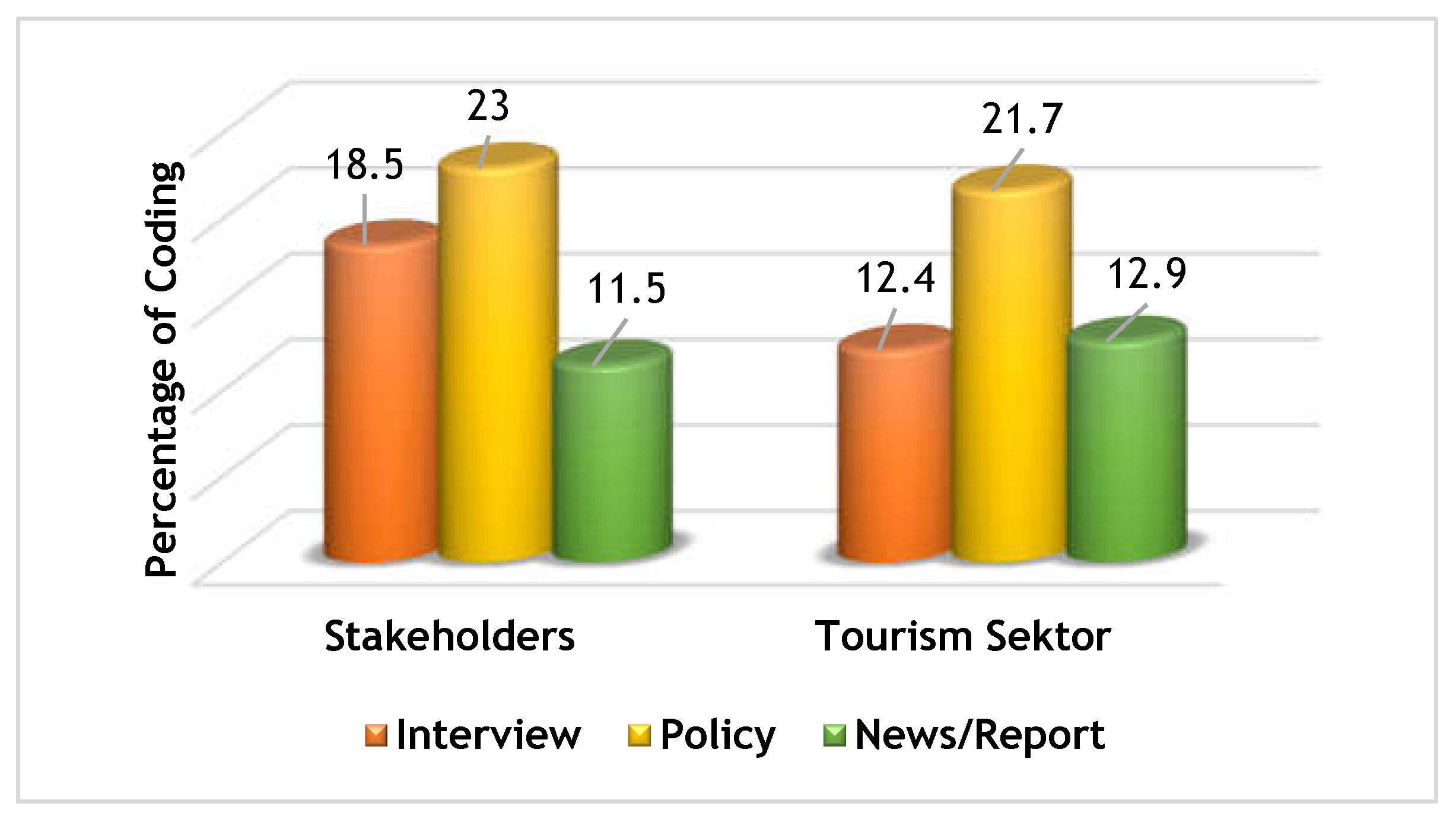

Job creation in the tourism sector within local government contributes significantly to regional economic growth and poverty alleviation (56). To ensure sustainability and inclusivity, it is important to analyze indicators such as stakeholder engagement (67,68), which reflects collaboration between the community, government, and private sector. In addition, monitoring the performance of the tourism sector through economic, social, and environmental indicators (69–71) helps identify new job opportunities and supports evidence-based policy-making, increasing the effectiveness of tourism-based local development programs.

Figure 6 shows the relationship between the indicators “Stakeholders” and “Tourism Sector” in job creation in Wakatobi, with data distribution from interviews, policy documents, and news sources. In the interviews, “stakeholders” accounted for the highest percentage (18.5 percent), indicating that local actors strongly emphasize the importance of collaboration between local government, communities, and businesses. One respondent stated that “cross-actor coordination is often ad hoc, without permanent mechanisms,” highlighting weaknesses in the participatory institutional structure. Conversely, the “Tourism Sector” only accounted for 12.4 percent in the interviews, indicating that discussions related to industry dynamics—such as workforce competencies and business innovation—remain underrepresented.

Policy documents show a dominant focus on two indicators: “Stakeholders” (23 percent) and “Tourism Sector” (21.7 percent), reflecting the government’s formal commitment to cross-sectoral collaboration and the development of the tourism industry as an economic driver. However, the proportion in news reports for the “Tourism Sector” (12.9 percent) is higher than that for “Stakeholders” (11.5 percent), indicating that public narratives focus more on industry performance than on inter-party relations. In line with the findings of (68), the use of stakeholder indicators is crucial to promote collaborative policy design that can expand job creation and economic inclusion in a sustainable manner.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study show that the tourism governance structure in Wakatobi tends to emphasize economic expansion without adequate protection for workers. The disparity between the focus on economic productivity in policy and the lack of attention to the rights and safety of informal workers (72,73) indicates a failure to apply the principle of social justice, which is at the core of SDG Eight (55). This pattern aligns with the argument by (74) regarding the weak integration of sustainable HRM in the tourism sector in developing countries. The lack of institutional accountability further weakens the effectiveness of policies (63), resulting in an anomaly between regulations and workplace realities that hinders the achievement of inclusive development.

Additionally, the marginalization of youth groups is evident in the low intensity of narratives in documents and public discourse related to youth employment (56). This contradicts the urgency of development based on productive demographics, as emphasized by (75,76), who place youth empowerment as a core element in community-based tourism. The minimal involvement of the younger generation reinforces. (77,78), view that inclusive tourism requires not only representation but also redistribution of roles and access within the work ecosystem. The mismatch between policy approaches and local potential demands structural reforms within the framework of regional tourism governance.

Theoretically, the findings of this study support the “relational work” approach in sociological economics as a critical framework for understanding the dynamics of informal and institutional work in tourism (26,79). In the context of Wakatobi, relationships between actors are often in tension between market work and community work, highlighting the need for adaptive and participatory institutional structures (10,16). Practically, these findings call for strengthening social indicators in monitoring systems and integrating cross-sectoral policies to ensure that tourism transformation not only drives economic growth but also guarantees social sustainability and meaningful community involvement. (80,81).

6. Practical Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several practical actions are recommended to enhance sustainable tourism governance and advance decent work and economic growth in Wakatobi:

- a)

Strengthen Institutional Coordination and Policy Integration

Local governments should establish a cross-institutional task force that brings together representatives from tourism, labor, environmental, and community sectors. This would bridge the gap between policy formulation and implementation while ensuring the alignment of SDG 8 principles with other development goals.

- b)

Enhance Labor Standards and Social Protection Mechanisms

Tourism stakeholders should formalize employment agreements and provide social protection for workers, especially in informal and seasonal positions. Programs such as local insurance schemes, skills certification, and safety training can enhance labor rights and job security.

- c)

Promote Youth Engagement and Capacity Building

Policies must target the empowerment of youth through vocational training, apprenticeship programs, and entrepreneurship support in the tourism value chain. Leveraging digital tools and creative industries could open new opportunities for young people in tourism-related services.

- d)

Foster Community-Based and Inclusive Tourism Models

Community-Based Tourism (CBT) initiatives should be scaled up by integrating local knowledge and prioritizing community participation in decision-making. Support for microfinance and cooperative models can help local communities capture value from tourism while preserving cultural and ecological assets.

- e)

Develop Monitoring and Evaluation Frameworks

Local authorities should adopt context-specific sustainability indicators to monitor tourism impacts, employment outcomes, and governance performance. Periodic assessments and stakeholder feedback mechanisms will help refine policies and ensure accountability.

- f)

Invest in Green and Resilient Tourism Infrastructure

Encouraging the development of eco-friendly accommodations, renewable energy systems, and waste management solutions in tourist areas will minimize environmental degradation while attracting responsible visitors. Such initiatives should be supported by financial incentives and technical assistance.

- g)

Encourage Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships

Collaboration among government, private sector, academia, and civil society is vital for fostering innovation and resource pooling. These partnerships should aim at inclusive marketing strategies, global networking, and sustainable destination branding.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, the scope of this research is limited to a single case study of Wakatobi Regency, which, although rich in insights due to its unique socio-ecological context, restricts the generalizability of the findings. Comparative studies involving other tourism-dependent regions in Indonesia or Southeast Asia would help to validate and refine the findings, particularly in terms of policy implementation and community participation in tourism governance.

Second, the qualitative nature of the study, based on semi-structured interviews and document analysis, offers in-depth understanding but limits the ability to quantify the economic and social outcomes of tourism labor policies. Future research could adopt mixed-methods approaches, integrating survey methods or secondary economic data, to measure the direct impact of governance reforms on employment quality and economic resilience.

Third, while this study reflects stakeholder perspectives from government, private sector, and community actors, it acknowledges the underrepresentation of vulnerable groups, such as women, informal workers, and youth who are not actively engaged in formal tourism management structures. Expanding the participant base to include these groups could offer a more balanced view of tourism’s social implications and better inform inclusive policy recommendations.

Finally, the fast-evolving nature of global tourism dynamics, especially with the rise of digital platforms and the effects of post-pandemic travel behavior, indicates that longitudinal research would be valuable. Tracking governance reforms, employment patterns, and technological integration over time could illuminate how adaptive governance contributes to sustainable and future-proof tourism sectors.

8. Conclusions

This study shows that sustainable tourism governance in Wakatobi has not been fully integrated with the dimensions of decent work and social inclusion as mandated by the eighth Sustainable Development Goal. The imbalance between economic expansion and labor protection, as well as the low involvement of youth, are indicators that the policy approach is still technocratic and not responsive to local conditions. Furthermore, weak intergovernmental coordination and a lack of policy evaluation systems show that existing institutional structures are unable to bridge the gap between participatory and adaptive implementation.

The implications of these findings are significant, both theoretically and practically. In general, this study supports the claim that participatory and community-based governance is a key prerequisite for achieving socially just and sustainable tourism. For the future, this work provides a perspective that strengthening local institutional capacity, substantially involving youth, and using context-based social indicators should be priorities in tourism policy design. Further research could be directed toward developing a more applicable and responsive SDG-based policy evaluation model that is responsive to local dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and H.L.; methodology, A.S.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., H.L. and L.M.A.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, H.L.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and L.M.A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, L.M.A.S..

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and the confidentiality agreements made with participants during the fieldwork.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the local government of Wakatobi Regency, community leaders, tourism practitioners, and all interview participants who generously shared their time, knowledge, and experiences during the fieldwork. Special thanks are also extended to the research assistants and local facilitators who supported data collection and logistics in the field. The authors are also grateful to colleagues from [Universitas Muhammadiyah Buton] for their constructive feedback during the development of this manuscript. Their intellectual and technical support greatly contributed to the refinement of this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| CBT |

Community-Based Tourism |

| HRM |

Human Resource Management |

| NVivo |

Qualitative Data Analysis Software (NVivo 12 Plus) |

| BOP |

Tourism Authority Board |

| TNW |

Wakatobi National Park |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| UNWTO |

United Nations World Tourism Organization |

| NGO |

Non-Governmental Organization |

| M&E |

Monitoring and Evaluation |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| DOI |

Digital Object Identifier |

References

- Huijbens, E.H. Topological encounters: Marketing landscapes for tourists. Jóhannesson GT, Ren C, René van der D, editors. Tourism Encounters and Controversies: Ontological Politics of Tourism Development. University of Aberdeen, The James Hutton Institute, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2016; pp. 201–220.

- Faryuni, I.D.; Saint-Amand, A.; Dobbelaere, T.; Umar, W.; Jompa, J.; Moore, A.M.; et al. Assessing coral reef conservation planning in Wakatobi National Park (Indonesia) from larval connectivity networks. Coral Reefs. 2024, 43, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, A.N.; Tichaawa, T.M. Sustainable development goals and socio-economic development through tourism in central Africa: Myth or reality? Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2018, 23, 780–796. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyacheya, J.; Hampton, M.P. Wishful thinking or wise policy? Theorising tourism-led inclusive growth: Supply chains and host communities. World Dev. 2020, 131, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawelai, H.; Sadat, A.; Harakan, A. The Level of Local Community Involvement in Sustainable Tourism Marketing of the World Coral Triangle in Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2024, 19, 4831–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, E.P.; Khairunnisa, T. Green Economy: Increasing Economic Growth to Support Sustainable Tourism in Super Priority Destinations. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2024, 19, 4021–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, D.; Soedarso Suryani, A.; Wibowo, B.M.; Muklason, A.; Endarko, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Sustainable tourism development based on local participation: Case study on Dalegan District for the East Java tourism industry. J.M.S. T, A. U, J.A. P, editors. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021, 777, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, K.M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Quevedo, J.M.D.; Kohsaka, R. Tourism impacts on small island ecosystems: public perceptions from Karimunjawa Island, Indonesia. J Coast Conserv. 2022, 26, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaya, F. behance.net. 2021. Peta Grafis Pariwisata Wakatobi. Available from: https://www.behance.net/gallery/111076635/Peta-Grafis-Pariwisata-Wakatobi.

- Nuraini, H.; Gunarto, G.; Satyawan, D.S.; Tobirin. Leveraging Local Potential through Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainable Tourism Village Development. Pak J Life Soc Sci. 2025, 23, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islahuddin Tun Ismail, W.N.A. Challenges and Opportunities for Implementing Innovative Green Tourism Practices: Evidence From Indonesia. Planning Malaysia. 2024, 22, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanto, B.T. Managing human resource in the rural tourism sector: evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Subarsono, A.; Rahmawati, I.Z.; Laksana, L.U.A.; Prabawati, V.D.N.; Wessiani, N.A.; Sulistiono, B. Poverty alleviation for coastal communities through tourism development: a case study of Kulon Progo Regency. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, E.B.; Ginting, N.; Revita, I.; Argarini, T.O.; Larasati, A.F. Evaluation of Community-Based Governance after the Revitalization of Huta Siallagan in Samosir Regency, Indonesia. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development 2024, 12, 266–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, L.D.; Melati, S.R.; Ganindha, R.; Wahyuliana, I.; Kurniawan, L.F.; Amilia, D.; et al. Tourism SDGs action plan from a regulatory perspective. Ma’arif A, Amzeri A, Caesarendra W, Suwarno I, editors. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 146, 01062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliah, A.; Prayitno, G.; Ari, I.R.D.; Adrianto, D.W.; Subagiyo, A.; Biloshkurska, N.V.; et al. The Role of Community Social Capital and Collective Action in the Development of Sustainable Tourism. Int Soc Sci J. 2025, 75, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswita, D.; Suryadarma, I.G.P.; Suyanto, S. Local wisdom of sabang island society (aceh, Indonesia) in building ecological intelligence to support sustainable tourism. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2018, 22, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Riana, N.; Fajri, K. Community empowerment in developing integrated tourism potentials at Cimincrang Sub-District, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2024, 1366, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlina, Sumarmi, Astina IK. Sustainable marine ecotourism management: A case of marine resource conservation based on local wisdom of bajo mola community in wakatobi national park. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2020, 32, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemy, D.M.; Teguh, F.; Pramezwary, A. TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: Establishment of Sustainable Strategies. In Bridging Tourism Theory and Practice; Pelita Harapan University, Indonesia: Emerald Group Holdings Ltd., 2019; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fianto, A.Y.A. Community-based marine tourism development in East Java Province, Indonesia. ABAC Journal. 2020, 40, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ristiawan, R.; Huijbens, E.; Peters, K. Projecting Development through Tourism: Patrimonial Governance in Indonesian Geoparks. Land (Basel) 2023, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, A.; Moslehpour, M.; Qiu, R.; Lin, P.K.; Ismail, T.; Rahman, F.F. The impact of eco-innovation, ecotourism policy and social media on sustainable tourism development: evidence from the tourism sector of Indonesia. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson Cederholm, E.; Sjöholm, C. The tourism business operator as a moral gatekeeper–the relational work of recreational hunting in Sweden. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2023, 31, 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernecky, T. Advancing critico-relational inquiry: is tourism studies ready for a relational turn? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2024, 32, 1201–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, E.A.; Helgadóttir, G.; Leick, B.; Sigurðardóttir, I. Relational Work in Rural Tourism Enterprising: Navigating In-between the Formal and the Informal. In Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer, 2024; pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari, P.; Muller-Camen, M.; Aust, I. The Sustainable HRM-SDG nexus: Contributions to global sustainable development. In Social Sustainability and Good Work in Organizations; Routledge, 2024; pp. 173–98.

- Santos, E. From Neglect to Progress: Assessing Social Sustainability and Decent Work in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15, 10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2019, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.; Hillman, A.G.; Elbe, J. Sustainable Tourism Employment, the Concept of Decent Work, and Sweden. In Tourism Employment in Nordic Countries: Trends, Practices, and Opportunities; Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020; pp. 327–48. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, A. Regional network governance and sustainable tourism. Tourism Geographies. 2015, 17, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aall, C.; Dodds, R.; Sælensminde, I.; Brendehaug, E. Introducing the concept of environmental policy integration into the discourse on sustainable tourism: a way to improve policy-making and implementation? Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2015, 23, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, M. Drivers of change in regional tourism governance: a case analysis of the influence of the New South Wales Government, Australia, 2007–2013. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2015, 3, 990–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Milanés, C.B. Factors that influence community-based tourism (CBT) in developing and developed countries. Tourism Geographies. 2021, 23, 1040–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A. Community-Based Tourism: A Catalyst for Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals One and Eight. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu LAd Walkowski, M.d.C.; Perinotto, A.R.C.; Fonseca, J.F.d. Community-Based Tourism and Best Practices with the Sustainable Development Goals. Adm Sci. 2024, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Rahmanita, M.; Zhixue, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Achieving Rural Sustainability through Community-Based Tourism (CBT). In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination (TGDIC 2023). Atlantis Press; 2023; pp. 299–306.

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.P.; Martin-Rios, C. “Think sustainable, act local” – a stakeholder-filter-model for translating SDGs into sustainability initiatives with local impact. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2019, 31, 2428–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Responsible tourism that creates shared value among stakeholders. Tourism Planning and Development 2016, 13, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, Y.; Içöz, O.; Içöz, O. Inclusive tourism and alignment of sustainable development goals (SDGs) among tourism stakeholders. In Inclusive Business Approaches in Tourism: Stakeholder Engagement; University of Massachusetts Amherst, United States: Nova Science Publishers, Inc, 2024; pp. 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, C.N.; O’Hara, K.L. Qualitative Research: Answering In-Depth Questions. In Evidence-Based Medicine: From the Clinician and Educator Perspective; Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, United States: Nova Science Publishers, Inc, 2022; pp. 129–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gillan, C.; Palmer, C.; Bolderston, A. Qualitative methodologies and analysis. In Research for the Radiation Therapist: From Question to Culture. Princess Margaret Cancer Centre; Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada: Apple Academic Press, 2014; pp. 127–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal 2025, 33, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A. Qualitative methodology for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med. 2005, 37, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. Guetterman TC, editor. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.R. Collecting Data from Networked Populations: Snowball and Respondent-Driven Sampling. In The Handbook of Teaching Qualitative and Mixed Research Methods: a Step-by-Step Guide for Instructors; London: Routledge, 2023; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dejonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured Interviewing in Primary Care Research:a Balance of Relationship and Rigour. Chinese General Practice 2019, 22, 2786–2792. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X. The biomechanics of public speaking: Enhancing political communication and persuasion through posture and gesture analysis. MCB Molecular and Cellular Biomechanics 2024, 21, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, A.; Lindholm, T.; Alm, C. Non-verbal cues in eyewitness testimonies do not predict accuracy or credibility assessments. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, S. Ethical Issues in Ethnographic Research: A Methodological Practice in the Field. In Ethnographic Research in the Social Sciences; London: Routledge India, 2023; pp. 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, R.S.; Koerber, A.L. Using NVivo to answer the challenges of qualitative research in professional communication: Benefits and best practices: Tutorial. IEEE Trans Prof Commun. 2011, 54, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, D. Analyzing Qualitative Data Using NVivo. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research; Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019; pp. 435–50. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H. Using Triangulation and Crystallization to Make Qualitative Studies Trustworthy and Rigorous. Qualitative Report 2024, 29, 1844–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Noguer-Juncà, E.; Louzao, N.; Coromina, L. Barcelona hotel employees and their conception of fair work. An exploratory study. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 2023, 42, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobing, M.; Afifuddin, S.; Ginting, R.; Sari, R.L. Evaluating Community Welfare Effects of the Tourism Development on Geopark Caldera Toba. Journal of Ecohumanism. 2024, 3, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D. Tourism Work and Workers in the Context of Sustainable Development. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism, Second Edition; Institution of Economics, Geography, Law and Tourism, Finland: Wiley, 2024; pp. 398–410. [Google Scholar]

- Polukhina, A.; Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Suranova, O.; Agalakova, O.; Antonov-Ovseenko, A. The Concept of Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in the Face of COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresiana, N.; Kartika, T. Developing a Model for Sustainable Traditional Tourism Village. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2024, 19, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniche, A.; Gallego, I. Benefits of policy actor embeddedness for sustainable tourism indicators’ design: the case of Andalusia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2023, 31, 1756–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafa, L.M.; Qi, H.; Chan, C.S. The roles of hierarchical administrations of tourism governance in China: a content analysis. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 2019, 11, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ap, J. Factors affecting tourism policy implementation: A conceptual framework and a case study in China. Tour Manag. 2013, 36, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Tabales, A.; Foronda-Robles, C.; Galindo-Pérez-de-Azpillaga, L.; García-López, A. Developing a system of territorial governance indicators for tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2017, 25, 1275–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, I.; Eduard, E.M. Opportunities and Challenges in Achieving Sustainable Tourism on Regional Level. In International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management; SGEM. University “1 Decembrie 1918” of Alba Iulia, Romania: International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference, 2024; pp. 165–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, A.; Seier, G.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Policies related to sustainable tourism – An assessment and comparison of European policies, frameworks and plans. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. 2020, 29, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández Mde la, C.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Is there a good model for implementing governance in tourist destinations? The opinion of experts. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.T.; Chau, N.T.; Vo, L.X.S. Applying network analysis in assessing stakeholders’ collaboration for sustainable tourism development: A case study at Danang, Vietnam. International Journal of Tourism Policy 2018, 8, 244–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.T.P.; Góis, S.M.R.; Gomes GN de, C.O. Tourism Monitoring as a Strategic Tool for Tourism Management: The Perceptions of Entrepreneurs from Centro de Portugal. Adm Sci. 2023, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga-Vallejo, L.C.; Guamán-Camacho, Y. Perception of local actors about tourism indicator system for destination management. Loja case study. In: C. S, M. O, S. S, editors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism Research. Private Technical University of Loja, Ecuador: Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited; 2021; pp. 261–8.

- Purwaningsih, R.; Agusti, F.; Nugroho Widyo Pranomo, S.; Susanty, A.; Purwanggono, B. Assessment sustainable tourism: A literature review composite indicator. Warsito B, Sudarno, Triadi Putranto T, editors. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 202, 03001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga-Vallejo, L.C.; Guaman-Camacho, Y.E. Tourism indicators and their impact on the management of emerging destinations. Journal of Tourism and Development 2023, 40, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.Y.S.; Rodríguez-Pallas, Á.; Reyes, G.L.V. Informality and tourist development on the Ecuadorian coast. In Managing Tourism and Hospitality Sectors for Sustainable Global Transformation; Peninsula de Santa Elena State University, Ecuador: IGI Global, 2024; pp. 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzopoulou, I.C. Labour Mobility and Tourism. Challenges and Opportunities for Decent and Sustainable Work in the Tourism Sector. The Case of Greece. In: V. K, G. C, editors. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Department of Tourism Management, University of Patras, Patras, Greece: Springer Nature, 2024; pp. 245–55.

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Applying sustainable employment principles in the tourism industry: righting human rights wrongs? Tourism Recreation Research 2019, 44, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, Y.; Sujarwo, S.; Suryono, Y. Learning From Goa Pindul: Community Empowerment through Sustainable Tourism Villages in Indonesia. Qualitative Report 2023, 28, 1365–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčinović, M.; Vujko, A.; Stanišić, N. Community-Led Sustainable Tourism in Rural Areas: Enhancing Wine Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Local Empowerment. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2025, 17, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.U. Community-led tourism and social equity: A regenerative approach to sustainable development. In Regenerative Tourism for Social Development; Abu Dhabi University, United Arab Emirates: IGI Global, 2025; pp. 339–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gillovic, B.; McIntosh, A. Accessibility and inclusive tourism development: Current state and future agenda. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, C.; Iannuzzi, E.; Curiello, S.; Spinnato, R.; Lurgi, M. A concrete action system in shaping an organizational field for roots tourism exploitation. The case study of ‘Rete Destinazione Sud’. Sinergie. 2024, 42, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, P.; Sousa, B.B.; Costa, M.; Liberato, D. Tourism sustainable planning in low density territories and the post (disaster) pandemic context. In Resilient and Sustainable Destinations After Disaster: Challenges and Strategies; Polytechnic Institute of Porto, School of Hospitality and Tourism, Portugal: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2023; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, M.B.; Khan, M.R.; Kumar, S. Socioeconomic gaps and foster inclusive growth: Sustainable tourism initiatives. In Building Community Resiliency and Sustainability With Tourism Development; International University of Business Agriculture and Technology, Bangladesh: IGI Global, 2024; pp. 56–82. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).