Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Media Use

2.1.1. Social Media Addiction

2.1.2. Motivational Drivers of Social Media Addiction

2.2. Fear of Missing Out

2.2.1. Definition

2.2.2. Different Contextual Conceptualizations of FoMO

2.2.3. Cognitive and Behavioral Antecedents of Fear of Missing Out

2.4. Procrastination and Cyberloafing

2.4.1. Definition

2.4.2. Cyberloafing

2.4.3. Psychological and Situational Causes of Cyberloafing

2.5. Work Engagement

2.6. Organizational Commitment

2.7. Hypotheses and Research Question On the basis of the theoretical background, six hypotheses and a research question were derived.

2.7.1. Social Media Addiction and Work Engagement

2.7.2. Social Media Addiction and Organizational Commitment

2.7.3. Social Media Addiction and Fear of Missing Out

2.7.4. Fear of Missing Out and Cyberloafing

2.7.5. Cyberloafing and Work Engagement

2.7.6. Cyberloafing and Organizational Commitment

2.8. Research Question

3. Methods

3.1. Open Science Practices

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS)

3.3.2. Fear of Missing Out Scale

3.3.3. Cyberloafing Scale

3.3.4. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)

3.3.5. Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ)

3.4. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Social Media Use

4.2. Testing of Hypotheses

4.3. Network Analysis

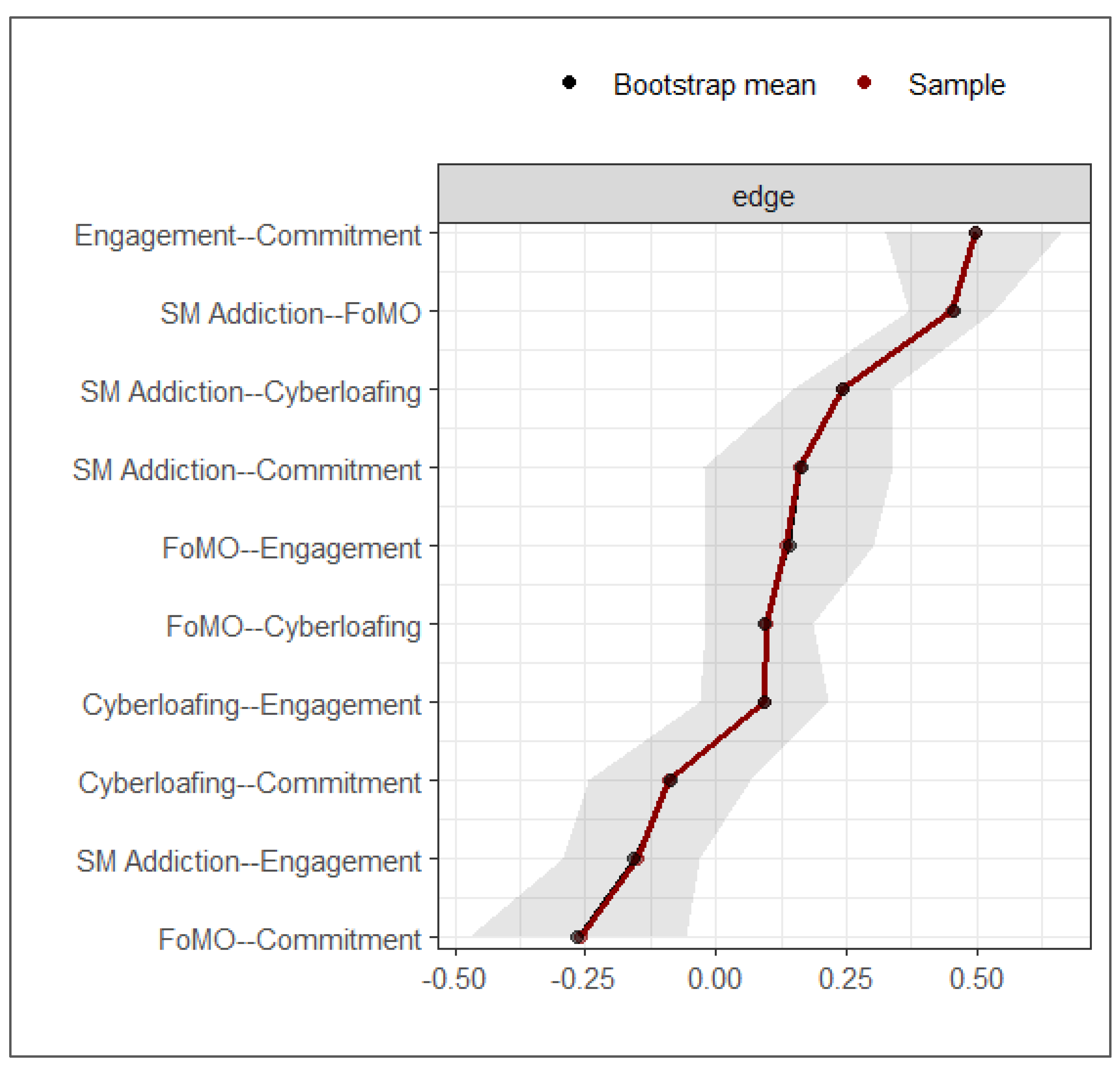

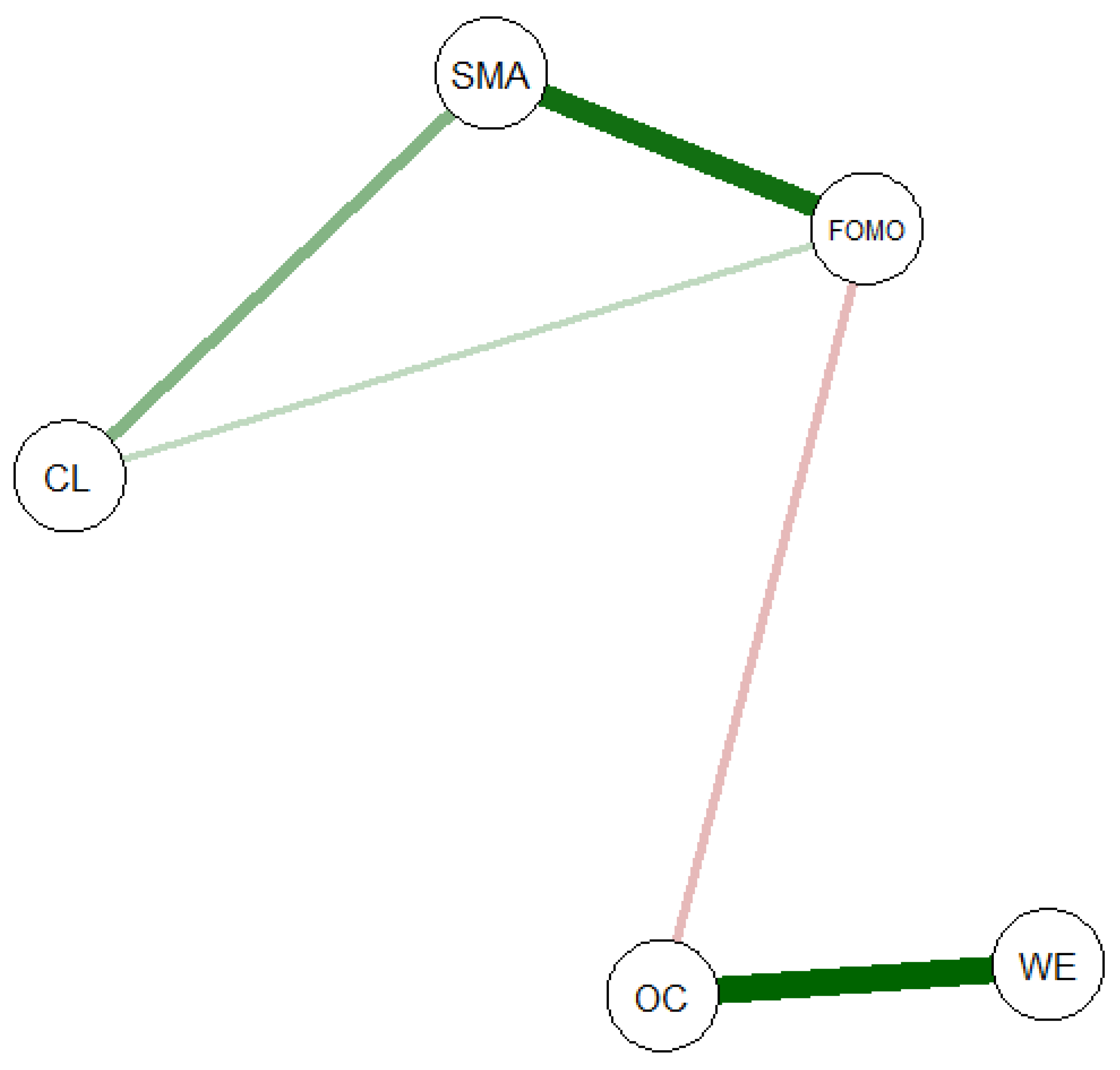

4.4. Network Structure

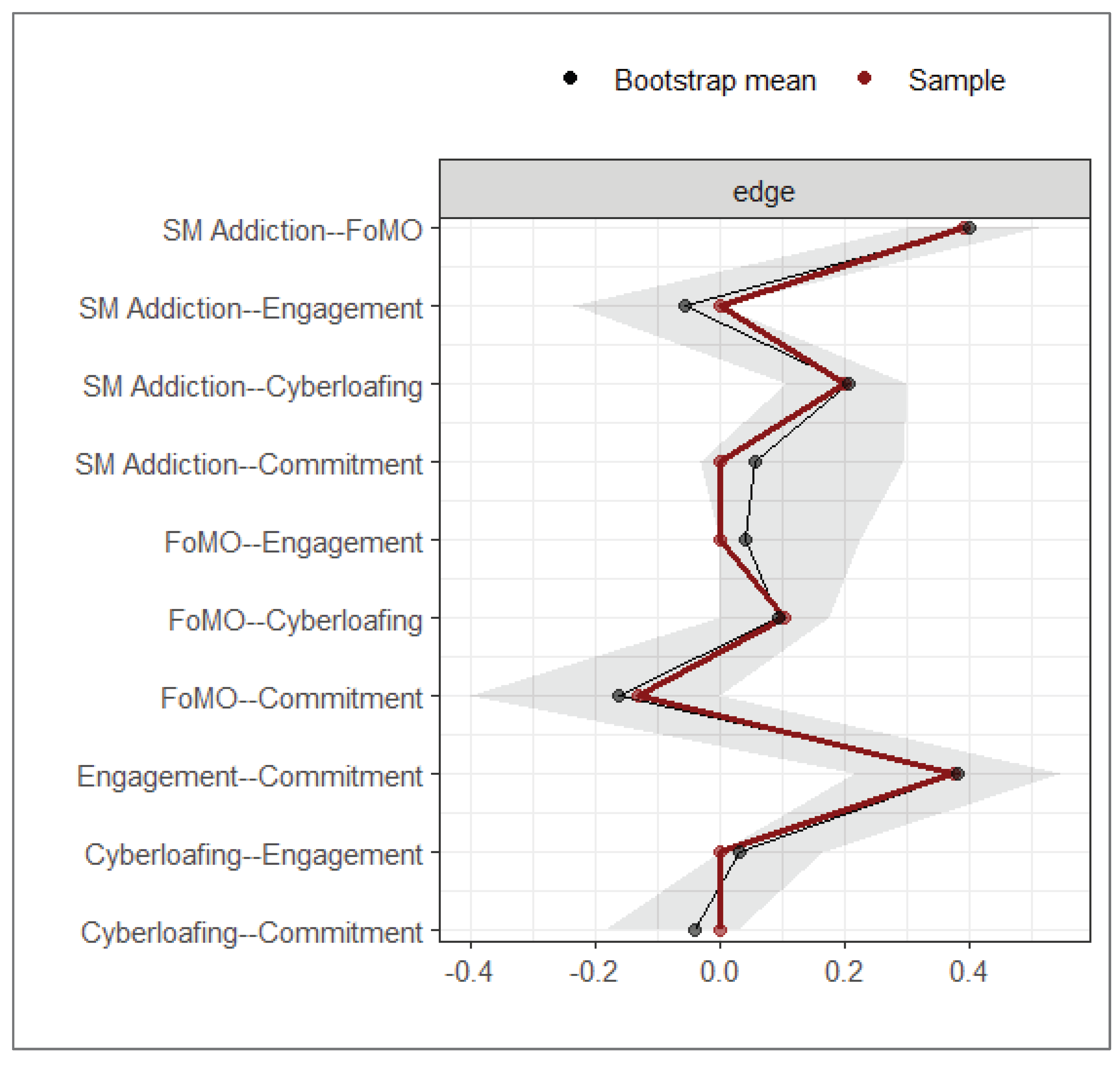

4.5. Explorative analyses: Network Analysis Using Graphical LASSO with EBIC Model Selection

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Results and Interpretation

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Appendices

Appendix A

Demographic Data

| Language | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| German | 408 | 90.27% |

| Italian | 11 | 2.43% |

| English | 10 | 2.21% |

| Russian | 9 | 1.99% |

| Turkish | 6 | 1.33% |

| French | 5 | 1.11% |

| Portuguese | 5 | 1.11% |

| Arabian | 4 | 0.88% |

| Spanish | 3 | 0.66% |

| Polish | 3 | 0.66% |

| Others | 39 | 5.53% |

| Occupational status | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Student | 278 | 61.50% |

| Employed | 12 | 2.65% |

| Student and employed | 162 | 35.84% |

| Retired | 0 | 0.00% |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0.00% |

| Language | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0-10 hours | 61 | 13.86% |

| 11-20 hours | 100 | 22.73% |

| 21-30 hours | 126 | 28.64% |

| 31-40 hours | 120 | 27.27% |

| 41-50 hours | 29 | 6.59% |

| More than 50 hours | 4 | 0.91% |

| Language | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0-10 hours | 67 | 38.51% |

| 11-20 hours | 61 | 35.06% |

| 21-30 hours | 27 | 15.52% |

| 31-40 hours | 12 | 6.90% |

| 41-50 hours | 7 | 4.02% |

| More than 50 hours | 0 | 0.00% |

Appendix B

Survey Instruments

| Items (English) |

Items (German) |

Response Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often during the last year have you . . . | Wie oft innerhalb des letzten Jahres haben bzw. sind Sie… | ||

| 1. | ...spent a lot of time thinking about social media or planned use of social media? | …viel Zeit damit verbracht, über soziale Medien nachzudenken oder die Nutzung von sozialen Medien geplant? | English 1 = very rarely 2 = rarely 3 = sometimes 4 = often 5 = very often German 1 = sehr selten 2 = selten 3 = manchmal 4 = oft 5 = sehr oft |

| 2. | ...felt an urge to use social media more and more? | ...einen Drang verspürt, soziale Medien mehr und mehr zu nutzen? | |

| 3. | … used social media to forget about personal problems? | …soziale Medien genutzt, um persönliche Probleme zu vergessen? | |

| 4. | … tried to cut down on the use of social media without success? | …versucht ohne Erfolg die Nutzung von sozialen Medien zu reduzieren? | |

| 5. | … become restless or troubled if you have been prohibited from using social media? | …unruhig oder besorgt geworden, wenn Ihnen nicht gestattet wurde soziale Medien zu nutzen? | |

| 6. | … used social media so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/studies? | …soziale Medien in einem so hohen Maß genutzt, dass es einen negativen Einfluss auf Ihre Arbeit/Studium/Schule hatte? |

| Items (English) |

Items (German) |

Response Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I fear others have more rewarding experiences than me. | Ich fürchte, andere machen mehr belohnende Erfahrungen als ich. |

English 1 = not at all true of me 2 = slightly true of me 3 = moderately true of me 4 = very true of me 5 = extremely true of me German 1 = trifft überhaupt nicht für mich zu 2 = trifft geringfügig für mich zu 3 = trifft etwas für mich zu 4 = trifft sehr für mich zu 5 = trifft extrem gut für mich zu |

| 2. | I fear my friends have more rewarding experiences than me. | Ich fürchte, meine Freunde haben mehr belohnende Erfahrungen als ich. | |

| 3. | I get worried when I find out my friends are having fun without me. | Es beunruhigt mich, wenn ich erfahre, dass meine Freunde ohne mich Spaß haben. | |

| 4. | I get anxious when I don’t know what my friends are up to. | Ich werde ängstlich, wenn ich nicht weiß, was meine Freunde vorhaben. | |

| 5. | It is important that I understand my friends ‘‘in jokes’’. | Es ist wichtig, dass ich die Witze meiner Freunde verstehe. | |

| 6. | Sometimes, I wonder if I spend too much time keeping up with what is going on. | Manchmal frage ich mich, ob ich nicht zu viel Zeit damit verbringe, herauszufinden, was gerade los ist. | |

| 7. | It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends. | Es ärgert mich, wenn ich eine Gelegenheit verpasse, meine Freunde zu treffen. | |

| 8. | When I have a good time it is important for me to share the details online (e.g. updating status). | Wenn es mir gerade gut geht, ist es für mich wichtig, Einzelheiten darüber online mitzuteilen (z. B. meinen Status zu updaten). | |

| 9. | When I miss out on a planned get-together it bothers me. | Wenn ich ein geplantes Treffen verpasse, ärgert mich das. | |

| 10. | When I go on vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing. | Auch wenn ich in Urlaub gehe, verfolge ich das, was meine Freunde so treiben, weiter. |

| Items (English) |

Items (German) |

Response Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Visit non-job related websites | Besuch von nicht berufsbezogenen Websites |

English 1 = never 2 = a few times per month 3 = a few times per week 4 = once a day 5 = a few times a day 6 = constantly German 1 = nie 2 = einige Male pro Monat 3 = einige Male pro Woche 4 = einmal pro Tag 5 = einige Male pro Tag 6 = ständig |

| 2. | Visit general news websites | Besuch von allgemeine Nachrichten-Websites | |

| 3. | Visit entertainment websites | Besuch von Unterhaltungs-Websites | |

| 4. | Visit sports related websites | Besuch von sportbezogenen Websites | |

| 5. | Instant message/chat online | Instant messaging/Online chatten | |

| 6. | Download non-work related information | Herunterladen von nicht arbeitsbezogenen Informationen | |

| 7. | Look for employment | Nach einer (anderen) Arbeitsstelle suchen | |

| 8. | Shop online | Online einkaufen | |

| 9. | Play online games | Online-Spiele spielen | |

| 10. | Visit adult-oriented (sexually explicit) websites | Besuch von Websites für Erwachsene (sexuell explizit) | |

| 11. | Visit online discussion boards or forums | Besuch von Online-Diskussionsforen oder -Plattformen | |

| 12. | Visit video sharing sites (YouTube, etc) | Besuch von Videoportalen (YouTube usw.) | |

| 13. | Visit social networking websites (Facebook, etc.) | Besuch von Websites für soziale Netzwerke (Instagram usw.) | |

| 14. | Visit investment or banking websites | Besuch von Websites für Investitionen oder Banken | |

| 15. | Check non-work related email | Abrufen von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | |

| 16. | Send non-work related email | Versenden von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | |

| 17. | Receive non-work related email | Empfangen von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | |

| 18. | Play games on social networking sites (Facebook games) | Spiele in sozialen Netzwerken spielen (Facebook-Spiele) | |

| 19. | Visit social news websites (reddit) | Besuch von sozialen Nachrichten-Websites (reddit) |

| Items (English) |

Items (German) |

Response Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | At my work, I feel bursting with energy. | Bei meiner Arbeit bin ich voll überschäumender Energie. |

English 1 = never 2 = almost never 3 = rarely 4 = sometimes 5 = often 6 = very often 7 = always German 1 = nie 2 = fast nie 3 = ab und zu 4 = regelmäßig 5 = häufig 6 = sehr häufig 7 = immer |

| 2. | At my job, I feel strong and vigorous. | Beim Arbeiten fühle ich mich fit und tatkräftig. | |

| 3. | I am enthusiastic about my job. | Ich bin von meiner Arbeit begeistert. | |

| 4. | My job inspires me. | Meine Arbeit inspiriert mich. | |

| 5. | When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. | Wenn ich morgens aufstehe, freue ich mich auf meine Arbeit. | |

| 6. | I feel happy when I am working intensely. | Ich fühle mich glücklich, wenn ich intensiv arbeite. | |

| 7. | I am proud of the work that I do. | Ich bin stolz auf meine Arbeit. | |

| 8. | I am immersed in my work. | Ich gehe völlig in meiner Arbeit auf. | |

| 9. | I get carried away when I’m working. | Meine Arbeit reißt mich mit. |

| Items (English) |

Items (German) |

Response Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected in order to help this company be successful. |

Ich bin bereit, mich mehr als nötig zu engagieren, um zum Erfolg des Unternehmens beizutragen. |

English 1 = totally disagree … 5 = totally agree German 1 = stimme absolut nicht zu … 5 = stimme völlig zu |

| 2. | I talk up this organization to my friends as a great company to work for. | Freunden gegenüber lobe ich dieses Unternehmen als besonders guten Arbeitgeber. | |

| 3. | I feel very little loyalty to this organization.* | Ich fühle mich diesem Unternehmen nur wenig verbunden.* | |

| 4. | I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this company. | Ich würde fast jede Veränderung meiner Tätigkeit akzeptieren, nur um auch weiterhin für dieses Unternehmen arbeiten zu können. | |

| 5. | I find that my values and the company's values are very similar. | Ich bin der Meinung, dass meine Wertvorstellungen und die des Unternehmens sehr ähnlich sind. | |

| 6. | I am proud to tell others that I am part of this company. | Ich bin stolz, wenn ich anderen sagen kann, dass ich zu diesem Unternehmen gehöre. | |

| 7. | I could just as well be working for a different company as long as the type of work were similar.* | Eigentlich könnte ich genauso gut für ein anderes Unternehmen arbeiten, solange die Tätigkeit vergleichbar wäre.* | |

| 8. | This company really inspires the very best in me in the way of job performance. | Dieses Unternehmen spornt mich zu Höchstleistungen in meiner Tätigkeit an. | |

| 9. | It would take very little change in my present circumstances to cause me to leave this company.* | Schon kleine Veränderungen in meiner gegenwärtigen Situation würden mich zum Verlassen des Unternehmens bewegen.* | |

| 10. | I am extremely glad that I chose this company to work for over others I was considering at the time I joined. | Ich bin ausgesprochen froh, dass ich bei meinem Eintritt dieses Unternehmen anderen vorgezogen habe. | |

| 11. | There’s not too much to be gained by sticking with this organization indefinitely.* | Ich verspreche mir nicht allzu viel davon, mich langfristig an dieses Unternehmen zu binden.* | |

| 12. | Often, I find it difficult to agree with this company's policies on important matters relating to its employees.* | Ich habe oft Schwierigkeiten, mit der Unternehmenspolitik in Bezug auf wichtige Arbeitnehmerfragen übereinzustimmen.* | |

| 13. | I really care about the fate of this company. | Die Zukunft dieses Unternehmens liegt mir sehr am Herzen. | |

| 14. | For me this is the best of all possible companies for which to work. | Ich halte dieses für das beste aller Unternehmen, die für mich in Frage kommen. | |

| 15. | Deciding to work for this organization was a definite mistake on my part.* | Meine Entscheidung, für dieses Unternehmen zu arbeiten war sicher ein Fehler.* |

Appendix C

Translation Procedure of the Cyberloafing Scale

| Original Item (English) |

Translation (German) |

Back-Translation (English) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Visit non-job related websites |

Besuch von nicht berufsbezogenen Websites | Visiting work-based websites |

| 2. | Visit general news websites | Besuch von allgemeinen Nachrichten-Websites | Visiting news websites |

| 3. | Visit entertainment websites | Besuch von Unterhaltungs-Websites | Visiting entertainment websites |

| 4. | Visit sports related websites | Besuch von sportbezogenen Websites | Visiting sport websites |

| 5. | Instant message/chat online | Sofortnachrichten/Chat online | Direct messenger / online chat |

| 6. | Download non-work related information | Herunterladen von nicht arbeitsbezogenen Informationen | Downloading non-work-related information |

| 7. | Look for employment | Nach einer (anderen) Arbeitsstelle suchen | Looking for another workplace |

| 8. | Shop online | Online einkaufen | Online shopping |

| 9. | Play online games | Online-Spiele spielen | Playing online-games |

| 10. | Visit adult-oriented (sexually explicit) websites | Besuch von Websites für Erwachsene (sexuell explizit) | Visiting adult websites (sexual, explicit) |

| 11. | Visit online discussion boards or forums | Besuch von Online-Diskussionsforen oder -Plattformen | Visiting online-discussion forum or panels |

| 12. | Visit video sharing sites (YouTube, etc) | Besuch von Videoportalen (YouTube usw.) | Visiting video platforms (YouTube etc.) |

| 13. | Visit social networking websites (Facebook, etc.) | Besuch von Websites für soziale Netzwerke (Instagram, Facebook usw.) | Visiting websites of social network platforms (Facebook etc.) |

| 14. | Visit investment or banking websites | Besuch von Websites für Investitionen oder Banken | Visiting investment or banking websites |

| 15. | Check non-work related email | Abrufen von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | Access non-work-related emails |

| 16. | Send non-work related email | Versenden von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | Sending non-work-related emails |

| 17. | Receive non-work related email | Empfangen von nicht berufsbezogenen E-Mails | Receiving non-working-related emails |

| 18. | Play games on social networking sites (Facebook games) | Spiele in sozialen Netzwerken spielen (Facebook-Spiele) | Playing social-network-games (Facebook etc.) |

| 19. | Visit social news websites (reddit) | Besuch von sozialen Nachrichten-Websites (reddit) | Visiting social-network websites (reddit) |

Appendix D

Participants' Use of Social Media Platforms

| Social Media Platform | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 69 | 15.27% | |

| 407 | 90.04% | |

| 444 | 98.23% | |

| Snapchat | 280 | 61.95% |

| TikTok | 189 | 41.81% |

| 57 | 12.61% | |

| Telegram | 36 | 7.96% |

| Twitter/X | 28 | 6.19% |

| 6 | 1.33% | |

| Twitch | 31 | 6.86% |

| YouTube | 353 | 78.10% |

| 41 | 9.07% | |

| 235 | 51.99% | |

| Others | 10 | 2.21% |

| Number of Social Media Platforms Used | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 2.21% |

| 2 | 16 | 3.54% |

| 3 | 58 | 12.80% |

| 4 | 105 | 23.20% |

| 5 | 113 | 25.00% |

| 6 | 95 | 21.00% |

| 7 | 36 | 7.96% |

| 8 | 13 | 2.88% |

| 9 | 3 | 0.66% |

| 10 | 1 | 0.22% |

| 11 | 2 | 0.44% |

| Frequency of Use | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 5 | 1.11% |

| 1-2 times per month | 3 | 0.66% |

| 3-4 times per month | 5 | 1.11% |

| 1-2 times per week | 7 | 1.55% |

| 3-4 times per week | 16 | 3.54% |

| At least once per day | 76 | 16.81% |

| 3-4 times per day | 133 | 29.42% |

| More than 4 times per day | 207 | 45.80% |

| Frequency of Use | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 275 | 60.84% |

| 1-2 times per month | 56 | 12.39% |

| 3-4 times per month | 26 | 5.75% |

| 1-2 times per week | 35 | 7.74% |

| 3-4 times per week | 19 | 4.20% |

| At least once per day | 22 | 4.87% |

| 3-4 times per day | 16 | 3.54% |

| More than 4 times per day | 3 | 0.66% |

| Frequency of Use | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1-2 times per month | 0 | 0.00% |

| 3-4 times per month | 2 | 0.44% |

| 1-2 times per week | 4 | 0.88% |

| 3-4 times per week | 1 | 0.22% |

| At least once per day | 22 | 4.87% |

| 3-4 times per day | 63 | 13.94% |

| More than 4 times per day | 360 | 79.65% |

Appendix E

Results of the Network Analysis

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Addiction | - | ||||

| Fear of Missing Out | .45 | - | |||

| Cyberloafing | .24 | .10 | - | ||

| Work Engagement | -.15 | .13 | .09 | - | |

| Organizational Commitment | .16 | -.26 | -.09 | .50 | - |

Appendix F

Results of the EBICglasso Network Analysis

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Media Addiction | - | ||||

| 2. Fear of Missing Out | .39 | - | |||

| 3. Cyberloafing | .20 | .10 | - | ||

| 4. Work Engagement | - | - | - | - | |

| 5. Organizational Commitment | - | -.13 | - | .42 | - |

| Node | Measure | Value (Absolut) |

Value (z-standardized) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social Media Addiction | Betweenness | 3 | 0.54 |

| 2 | Fear of Missing Out | Betweenness | 3 | 1.10 |

| 3 | Cyberloafing | Betweenness | 0 | -1.10 |

| 4 | Work Engagement | Betweenness | 0 | -1.10 |

| 5 | Organizational Commitment | Betweenness | 3 | 0.54 |

| 6 | Social Media Addiction | Closeness | 0.03 | 0.74 |

| 7 | Fear of Missing Out | Closeness | 0.04 | 1.24 |

| 8 | Cyberloafing | Closeness | 0.02 | -1.05 |

| 9 | Work Engagement | Closeness | 0.02 | -0.90 |

| 10 | Organizational Commitment | Closeness | 0.03 | -0.03 |

| 11 | Social Media Addiction | Strength | 0.59 | 0.81 |

| 12 | Fear of Missing Out | Strength | 0.63 | 1.05 |

| 13 | Cyberloafing | Strength | 0.30 | -1.27 |

| 14 | Work Engagement | Strength | 0.37 | -0.77 |

| 15 | Organizational Commitment | Strength | 0.51 | 0.18 |

| 16 | Social Media Addiction | Expected Influence | 0.59 | 1.64 |

| 17 | Fear of Missing Out | Expected Influence | 0.36 | -0.10 |

| 18 | Cyberloafing | Expected Influence | 0.30 | -0.54 |

| 19 | Work Engagement | Expected Influence | 0.37 | -0.01 |

| 20 | Organizational Commitment | Expected Influence | 0.24 | -1.00 |

Folgende Ding könntest du schonmal machen:

References

- Abel, J.P.; Buff, C.L.; Burr, S.A. Social Media and the Fear of Missing Out: Scale Development and Assessment. Journal of Business & Economics Research 2016, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Seman, S.A.; Mohd Hashim, M.J.; Zainal, N.Z. & Mohd Ishar, N.I. Distracted in the digital age: Unveiling cyberslacking habits among university students. International Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/95092/. 2024, 19, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, S.; Gupta, S. Organizational commitment and work engagement as a facilitator for sustaining higher education professionals. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 2019, 7, 1846–1851. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/savita-gupta-5/publication/333845020_organizational_commitment_and_work_engagement_a_s_a_facilitator_for_sustaining_higher_education_professionals/links/5d08c2eca6fdcc35c1560539/organizational-commitment-and-work-engagement-a-s-a-facilitator-for-sustaining-higher-education-professionals.pdf.

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, S.A.; Kessler, S.R.; Pindek, S.; Kleinman, G.; Spector, P.E. Is cyberloafing more complex than we originally thought? Cyberloafing as a coping response to workplace aggression exposure. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 101, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The Relationship Between Addictive Use of Social Media and Video Games and Symptoms of Psychiatric Disorders: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Social network site addiction - an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2014, 20, 4053–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Brunborg, G.S.; Pallesen, S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, K.L. (2012). The relationship between cyberloafing and task performance and an examination of the theory of planned behavior as a model of cyberloafing (Dissertation). University of South Florida. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/154469515.pdf.

- Baethge, A.; Rigotti, T.; Roe, R.A. Just more of the same, or different? An integrative theoretical framework for the study of cumulative interruptions at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2015, 24, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. (2010). Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. Psychology Press.

- Beard, K.W.; Wolf, E.M. Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society 2001, 4, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.; Leaman, C.; Tramposch, R.; Osborne, C.; Liss, M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and Fear of Missing Out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.L.; Henle, C.A. Correlates of different forms of cyberloafing: The role of norms and external locus of control. Computers in Human Behavior 2008, 24, 1067–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodjrenou, K.; Xu, M.; Bomboma, K. Antecedents of Organizational Commitment: A Review of Personal and Organizational Factors. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2019, 7, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Schillack, H.; Margraf, J. (2020). Tell me why are you using social media (SM)! Relationship between reasons for use of SM, SM flow, daily stress, depression, anxiety, and addictive SM use – An exploratory investigation of young adults in Germany. Computers in Human Behavior. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Budnick, C.J.; Rogers, A.P.; Barber, L.K. The Fear of Missing Out at work: Examining costs and benefits to employee health and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior 2020, 104, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglass, S.L.; Binder, J.F.; Betts, L.R.; Underwood, J.D. Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network site use and FOMO. Computers in Human Behavior 2017, 66, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapri, B.; Gündüz, B.; Akbay, S.E. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student Forms' (UWES-SF) Adaptation to Turkish, Validity and Reliability Studies, and the Mediator Role of Work Engagement between Academic Procrastination and Academic Responsibility. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1147496. 2017, 17, 411–435. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, C.T.; Hayes, R.A. Social Media: Defining, Developing, and Divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication 2015, 23, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Rugai, L.; Fioravanti, G. Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the Fear of Missing Out and social media addiction. Addictive Behaviors 2018, 85, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan, M.; Galperin, B.L.; Ostle, A.; Behl, A. Millennial’s perception on cyberloafing: Workplace deviance or cultural norm? Behavior & Information Technology 2022, 41, 2860–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. Narcissism and Social Media Addiction in Workplace. The Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business 2018, 5, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbeanu, A.; Iliescu, D. The Link Between Work Engagement and Job Performance. Journal of Personnel Psychology 2023, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Perugini, M.; Mõttus, R.; Waldorp, L.J.; Cramer, A.O. State of the aRt personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. Journal of Research in Personality 2015, 54, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, V.; Mensink, D.; O'Sullivan, M. Patterns of Academic Procrastination. Journal of College Reading and Learning 2000, 30, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Boston, MA: Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçer, E.; Saygın, M.; Karadal, H. (2022). The Fear of Missing Out (FoMO): Theoretical Approach and Measurement in Organizations. In F. Özsungur (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Digital Violence and Discrimination Studies (pp. 631–651). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.; Norman, H.; Alrobai, A.; Jiang, N.; Nordin, N.; Adnan, A. A web-based intervention for social media addiction disorder management in higher education: Quantitative survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2019, 21. Retrieved from https://www.jmir.org/2019/10/e14834/.

- Dursun, O.O.; Donmez, O.; Akbulut, Y. Predictors of Cyberloafing among Preservice Information Technology Teachers. Contemporary Educational Technology Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/cet/issue/34282/378820. 2018, 9, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, J.R. Compulsive procrastination: Some self-reported characteristics. Psychological Reports 1991, 68, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, J.R. (1993). Procrastination and impulsiveness: Two sides of a coin? In W. G. McCown, J. Johnson, & M. B. Shure (Eds.), The Impulsive client: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 265–276). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J.R. Dysfunctional procrastination and its relationship with self-esteem, interpersonal dependency, and self-defeating behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences 1994, 17, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzi Behnagh, R.; Ferrari, J.R. Exploring 40 years on affective correlates to procrastination: A literature review of situational and dispositional types. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 1097–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Casale, S.; Benucci, S.B.; Prostamo, A.; Falone, A.; Ricca, V.; Rotella, F. Fear of Missing Out and social networking sites use and abuse: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 122, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foygel, R.; Drton, M. Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2010, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.; Li, R.; Liang, Y. The Relationship between Stress Perception and Problematic Social Network Use among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of the Fear of Missing Out. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, F. & Feeney, M.K. Social Media in the Workplace: Information Exchange, Productivity, or Waste? The American Review of Public Administration 2018, 48, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, G.; Shourie, S. Relationship between Social Media Addiction, FOMO and Self-Esteem among Young Adults. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Approaches in Psychology Retrieved from https://www.psychopediajournals.com/index.php/ijiap/article/view/101. 2023, 1, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, R.K.; Danziger, J.N. Disaffection or expected outcomes: Understanding personal Internet use during work. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2008, 13, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.K.; Danziger, J.N. On cyberslacking: Workplace status and personal internet use at work. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society 2008, 11, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.; Popescul, D. Social Media – The New Paradigm of Collaboration and Communication for Business Environment. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 20, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.; Klare, D.; Ceballos, N.; Dailey, S.; Kaiser, S.; Howard, K. Do You Dare to Compare? The Key Characteristics of Social Media Users Who Frequently Make Online Upward Social Comparisons. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2022, 38, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-romá, V.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Lloret, S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational Behavior 2006, 68, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Internet addiction fuels other addictions. STUDENTBMJ 1999, 7, 428–429. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. Internet Addiction - Time to be Taken Seriously? Addiction Research 2000, 8, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J. Adolescent social media addiction (revisited). Education and Health Retrieved from https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/31776/1/pubsub9230_griffiths.pdf. 2017, 35, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Groenestein, E.; Willemsen, L.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Kerkhof, P. (2024). Fear of Missing Out and social media use: A three-wave longitudinal study on the interplay with psychological need satisfaction and psychological well-being. New Media & Society. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Gullu, B.F.; Serin, H. The Relationship between Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) Levels and Cyberloafing Behavior of Teachers. Journal of Education and Learning Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1270589. 2020, 9, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, F.; Bayrakli, M.; Gezgin, D.M. The effect of cyberloafing behaviors on smartphone addiction in university students: The mediating role of Fear of Missing Out. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning 2023, 6, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamutoglu, N.B.; Topal, M.; Gezgin, D.M. Investigating Direct and Indirect Effects of Social Media Addiction, Social Media Usage and Personality Traits on FOMO. International Journal of Progressive Education Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1249965. 2020, 16, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartijasti, Y.; Fathonah, N. Cyberloafing across generation X and Y in Indonesia. Journal of Information Technology Applications & Management 2014, 21. Retrieved from https://koreascience.kr/article/jako201410661372802.page.

- Hassan, K.M.; Bolong, J. Relationship between social media addiction and organizational commitment. Al-I’lam-Journal of Contemporary Islamic Communication and Media Retrieved from https://jcicom.usim.edu.my/index.php/journal/article/download/1/1. 2021, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, T. (2018). Dopamine, Smartphones & You: A battle for your time.

- Hensel, P.G.; Kacprzak, A. Job Overload, Organizational Commitment, and Motivation as Antecedents of Cyberloafing: Evidence from Employee Monitoring Software. European Management Review 2020, 17, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoşgör, H.; Ülker Dörttepe, Z. ; Memiş; K Social media addiction and work engagement among nurses. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2021, 57, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, E.; Wadley, G.; Berthouze, N.; Cox, A.L. Social Media Breaks: An Opportunity for Recovery and Procrastination. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2024, 8, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xiong, D.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 2009, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, M.-T.; Wang, F. Social media addiction and employees’ innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model of work engagement and mindfulness. Current Psychology 2024, 43, 34729–34746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Yusra, Y.; Shah, N.U. Impact of Social Media Addiction on Work Engagement and Job Performance. Polish Journal of Management Studies 2022, 25, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.; Ma, R.; McNally, R.J. Bridge Centrality: A Network Approach to Understanding Comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2021, 56, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanning, U.P.; Hill, A. Validation of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) in six languages. Journal of Business and Media Psychology Retrieved from https://journal-bmp.de/wp-content/uploads/kanning-hill-formatiert-final2_aretz_22012014.pdf. 2013, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerse, G.; Deniz, V.; Cakici, A.B. The Effect of “Fear of Missing Out at Work (W-FoMO)” on Psychological Well-Being: The Serial Mediating Roles of Smartphone Use After Work and Work-Family Conflict. SAGE Open 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Moin, M.F.; Khan, N.A.; Zhang, C. A multistudy analysis of abusive supervision and social network service addiction on employee's job engagement and innovative work behavior. Creativity and Innovation Management 2022, 31, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y. Workplace ostracism and cyberloafing: A moderated–mediation model. Internet Research 2018, 28, 1122–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koessmeier, C.; Büttner, O.B. Why Are We Distracted by Social Media? Distraction Situations and Strategies, Reasons for Distraction, and Individual Differences. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 711416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online social networking and addiction-a review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwala, A.F.; Agoyi, M. The Influence of Cyberloafing on Workplace Outcomes: A Study Utilizing the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Theory. SAGE Open 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenny, D.J.; Doleck, T.; Bazelais, P. Self-Determination, Loneliness, Fear of Missing Out, and Academic Performance. Knowledge Management & E-Learning Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1245586. 2019, 11, 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, S.-L.; Sun, X.-J.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Fan, C.-Y.; Niu, G.-F.; Liu, Q.-Q. Social networking site addiction and undergraduate students' irrational procrastination: The mediating role of social networking site fatigue and the moderating role of effortful control. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0208162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, V.K.G. The IT way of loafing on the job: Cyberloafing, neutralizing and organizational justice. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2002, 23, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.K.G.; Teo, T.S.H. Prevalence, perceived seriousness, justification and regulation of cyberloafing in Singapore: An exploratory study. Information & Management Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0378720604001600. 2005, 42, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, V.K.; Chen, D.J. Cyberloafing at the workplace: Gain or drain on work? Behavior & Information Technology 2012, 31, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Ma, L. (2021). Taking Micro-breaks at Work: Effects of Watching Funny Short-Form Videos on Subjective Experience, Physiological Stress, and Task Performance. In P.-L. P. Rau (Ed.), Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Arts, Learning, Well-being, and Social Development (pp. 183–200). Cham: Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lei, K. Development and validity test of impression management efficacy scale based on self-presentation behavior of Chinese youth on social media. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16, 1494083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macit, H.B.; Macit, G.; Güngör, O. A Research on Social Media Addiction and Dopamine Driven Feedback. Journal of Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Economics and Administrative Sciences Faculty 2018, 5, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, E.; Perez Vallejos, E.; Spence, A. Digital workplace technology intensity: Qualitative insights on employee wellbeing impacts of digital workplace job demands. Frontiers in Organizational Psychology 2024, 2, 1392997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhurst, A.R.; Albrecht, S.L. Salesperson work engagement and flow. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 2016, 11, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J.R.; Rosado-Solomon, E.H.; Downes, P.E.; Gabriel, A.S. Office Chitchat as a Social Ritual: The Uplifting Yet Distracting Effects of Daily Small Talk at Work. Academy of Management Journal 2021, 64, 1445–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, U.B.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Taris, T.W. Correlates of procrastination and performance at work: The role of having "good fit". Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 2018, 46, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metin, U.B.; Taris, T.W.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Korpinen, M.; Smrke, U.; Razum, J.; Kolářová, M; Baykova, R.; Gaioshko, D. Validation of the Procrastination at Work Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2020, 36, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Paunonen, S.V.; Gellatly, I.R.; Goffin, R.D.; Jackson, D.N. Organizational commitment and job performance: It's the nature of the commitment that counts. Journal of Applied Psychology 1989, 74, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.E.; Hu, B.; Beldona, S.; Clay, J. Cyberslacking! Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 2001, 42, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M.; Saffran, M.; Hope, N.; Koestner, R. Fear of Missing Out: Prevalence, dynamics, and consequences of experiencing FOMO. Motivation and Emotion 2018, 42, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Błaszkiewicz, K.; Sariyska, R.; Lachmann, B.; Andone, I.; Trendafilov, B.; Eibes, M.; Markowetz, A. Smartphone usage in the 21st century: Who is active on WhatsApp? BMC Research Notes 2015, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafi, M. The Effects of Cyberloafing on Organizational Commitment: The Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Job Overload. Jurnal Bisnis: Teori Dan Implementasi 2023, 14, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M.C.; Marchetti, I.; Beevers, C.G. Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Symptoms of Adolescent Depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology American Psychological Association Division 53 2019, 48, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.M.; Wegmann, E.; Stolze, D.; Brand, M. Maximizing social outcomes? Social zapping and Fear of Missing Out mediate the effects of maximization and procrastination on problematic social networks use. Computers in Human Behaviors 2020, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaei, M.; Peidaei, M.M.; Nasiripour, A.A. The relation between staff cyberloafing and organizational commitment in organization of environmental protection. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Kuwait Chapter) Retrieved from https://j.arabianjbmr.com/index.php/kcajbmr/article/view/575. 2014, 3, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, A.; Rabie, G.H.; Beer, L.T. de Investigating cyberloafing, organisational justice, work engagement and organisational trust of South African retail and manufacturing employees. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, M.A.; Castellano, S.; Khelladi, I.; Marinelli, L.; Monge, F. Technology distraction at work. Impacts on self-regulation and work engagement. Journal of Business Research 2021, 126, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, H.M. Koç, U. The Role of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) in the relationship between personality traits and cyberloafing. Ege Academic Review 2022, 23, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Kerse, G. Smartphone and internet addiction as predictors of cyberloafing levels in students: A mediated model. Education for Information 2022, 38, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Stasi, A.; Bhatiasevi, V. Research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1017506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of Fear of Missing Out. Computers in Human Behavior 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pychyl, T.A.; Lee, J.M.; Thibodeau, R.; Blunt, A. Five days of emotion: An experience sampling study of undergraduate student procrastination. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=08861641&an=10637249&h=djwg8xkvphsvfnlaue%2b9wjou31yvw5akmpzgr5za1rudwpb957twu68bpkbtlms0m7r5huod%2bg%2f9njmizanspg%3d%3d&crl=c. 2000, 15, 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Young, A.L. Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bulletin of Science Technology & Society 2010, 30, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, M.; Taghi Amini, M.; Foroozandeh, N. Studying the impact of the organizational commitment on the job performance. Management Science Letters 2014, 4, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T. Personal web usage and work inefficiency. Business Strategy Series 2010, 11, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, R.; John, A.S. (2023). Determinants of Procrastination among young adults in their academics and professional lives, Youth Voice Journal. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=20492073&an=171382950&h=6cemfvxa%2ffykijqbgxkv4vo5w9q6meqg9binrrtxobh9hvdo1iixryd63xagdaplajzrl77jy8sozrkpalnciq%3d%3d&crl=c.

- Reer, F.; Tang, W.Y.; Quandt, T. Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and Fear of Missing Out. New Media & Society 2019, 21, 1486–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, L.-E.; Binnewies, C.; Ozimek, P.; Loose, S. I Do Not Want to Miss a Thing! Consequences of Employees' Workplace Fear of Missing Out for ICT Use, Well-Being, and Recovery Experiences. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2016, 125, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothblum, E.D.; Solomon, L.J.; Murakami, J. Affective, cognitive, and behavioral differences between high and low procrastinators. Journal of Counseling Psychology 1986, 33, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Sindermann, C.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. (2020). Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and social media's impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat Use Disorders mediate that association? Addictive Behaviors. (110). Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0306460320306171.

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehan, M.; Negahban, A. Social networking on smartphones: When mobile phones become addictive. Computers in Human Behavior 2013, 29, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritepeci, M. Predictors of cyberloafing among high school students: Unauthorized access to school network, metacognitive awareness and smartphone addiction. Education and Information Technologies 2020, 25, 2201–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. (2004b). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale - Preliminary Manual. Retrieved from Utrecht University website: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_English.pdf.

- Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A 'how to'guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0090261617300876. 2017, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senécal, C.; Koestner, R.; Vallerand, R.J. Self-Regulation and Academic Procrastination. The Journal of Social Psychology 1995, 135, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, P; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T.; Hakanen, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Tolvanen, A.; Schaufeli, W. The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Multisample and Longitudinal Evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies 2009, 10, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W. Kyle & Pychyl, Timothy A. (2009). In search of the arousal procrastinator: Investigating the relation between procrastination, arousal-based personality traits and beliefs about procrastination motivations, 47, 906–911. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0191886909003213.

- Smith, A.; Anderson, M. (2018). Social Media Use in 2018.

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, M. Smartphones, Angst und Stress. Nervenheilkunde 2015, 34, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M. Antecedents and Outcomes of Organizational Commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly 1977, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addictive Behaviors 2021, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Singh, H.; Thangaraju, S.K.; Bakri, N.E.; Hwa, K.Y. & Kusalavan, P.A.L. The impact of cyberloafing on employees' job performance: A review of literature. Journal of Advances in Management Sciences & Information Systems https://www.researchgate.net/profile/sumera-syed/publication/345972045_the_impact_of_cyberloafing_on_employees'_job_performance_a_review_of_literature/links/5fbf38b8458515b7976febf0/the-impact-of-cyberloafing-on-employees-job-performance-a-review-of-literature.pdf. 2020, 6, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Ruparel, N.; Islam, J.U.; Dhir, A. Cyberloafing and cyberslacking in the workplace: Systematic literature review of past achievements and future promises. Internet Research 2022, 32, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M.; Bratslavsky, E.; Baumeister, R.F. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2001, 80, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunc-Aksan, A.; Akbay, S.E. Smartphone Addiction, Fear of Missing Out, and Perceived Competence as Predictors of Social Media Addiction of Adolescents. European Journal of Educational Research 2019, 8, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, G.B.; Özer, Z. & Atan, G. The relationship between cyberloafing levels and social media addiction among nursing students. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2021, 57, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Serenko, A. The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. European Journal of Information Systems 2012, 21, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutgun Ünal, A. A Comparative Study of Social Media Addiction Among Turkish and Korean University Students. Journal of Economy Culture and Society 2020, 62, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslukaya, A.; Zincirli, M. Reciprocal relationships between job resources and work engagement in teachers: A longitudinal examination of cross-lagged and simultaneous effects. Social Psychology of Education 2025, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Javed, U.; Shoukat, A.; Bashir, N.A. Does meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles of affective commitment and leader-member exchange. Behavior & Information Technology 2021, 40, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eerde, W. (2016). Procrastination and Well-Being at Work. In F. M. Sirios & T. A. Pychyl (Eds.), Procrastination, Health, and Well-Being (pp. 233–253). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, W.; Verhoeven, J.W.; Vliegenthart, R. Understanding the consequences of public social media use for work. European Management Journal 2017, 35, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanMeter, R.A.; Grisaffe, D.B.; Chonko, L.B. Of “Likes” and “Pins”: The Effects of Consumers’ Attachment to Social Media. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2015, 32, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, A. On the Desirability of Social Desirability Measures in Substance Use Research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2022, 83, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitak, J.; Crouse, J.; LaRose, R. Personal Internet use at work: Understanding cyberslacking. Computers in Human Behavior 2011, 27, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.A.; Rose, J.P.; Roberts, L.R.; Eckles, K. Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 2014, 3, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, M.; Lei, L. Fear of Missing Out and Procrastination as Mediators Between Sensation Seeking and Adolescent Smartphone Addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2019, 17, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. The Emotional Reinforcement Mechanism of and Phased Intervention Strategies for Social Media Addiction. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, A.; Williams, D. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2013, 16, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Lei, L. Basic psychological needs satisfaction and Fear of Missing Out: Friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Research 2018, 268, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S. Internet addiction: Evaluation and treatment. BMJ 1999, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivnuska, S.; Carlson, J.R.; Carlson, D.S.; Harris, R.B.; Harris, K.J. Social media addiction and social media reactions: The implications for job performance. The Journal of Social Psychology 2019, 159, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable/Scale | Number of Items |

Response Format | Cronbach’s α | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale | 6 | Very rarely (1) – very often (5) | .79 | 2.68 | 0.80 |

| Fear of Missing Out Scale | 10 | Not at all true of me (1) – Extremely true of me (5) | .74 | 2.62 | 0.59 |

| Cyberloafing Scale | 19 | Never (1) – Once a day (4) – Constantly (6) | .89 | 2.39 | 0.73 |

| Utrecht Work Engagement Scale | 9 | Never (1) – Always (7) | .92 | 4.21 | 0.99 |

| Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) | 15 | Totally disagree (1) – Totally agree (5) | .91 | 3.20 | 0.78 |

| Node | Measure | Value (Absolut) |

Value (z-standardized) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social Media Addiction | Betweenness | 3 | 1.38 |

| 2 | Fear of Missing Out | Betweenness | 2 | 0.61 |

| 3 | Cyberloafing | Betweenness | 0 | -0.92 |

| 4 | Work Engagement | Betweenness | 0 | -0.92 |

| 5 | Organizational Commitment | Betweenness | 1 | -0.15 |

| 6 | Social Media Addiction | Closeness | 0.05 | 0.83 |

| 7 | Fear of Missing Out | Closeness | 0.05 | 1.06 |

| 8 | Cyberloafing | Closeness | 0.03 | -1.37 |

| 9 | Work Engagement | Closeness | 0.03 | -0.55 |

| 10 | Organizational Commitment | Closeness | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 11 | Social Media Addiction | Strength | 1.01 | 0.69 |

| 12 | Fear of Missing Out | Strength | 0.94 | 0.36 |

| 13 | Cyberloafing | Strength | 0.52 | -1.72 |

| 14 | Work Engagement | Strength | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| 15 | Organizational Commitment | Strength | 1.00 | 0.66 |

| 16 | Social Media Addiction | Expected Influence | 0.71 | 1.42 |

| 17 | Fear of Missing Out | Expected Influence | 0.43 | -0.27 |

| 18 | Cyberloafing | Expected Influence | 0.34 | -0.78 |

| 19 | Work Engagement | Expected Influence | 0.57 | 0.60 |

| 20 | Organizational Commitment | Expected Influence | 0.31 | -0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).