This section presents the validation and performance assessment of the proposed multi-fidelity surrogate-based optimization framework for analog circuit design. The analysis is organized into three parts.

3.3. Results and Analysis

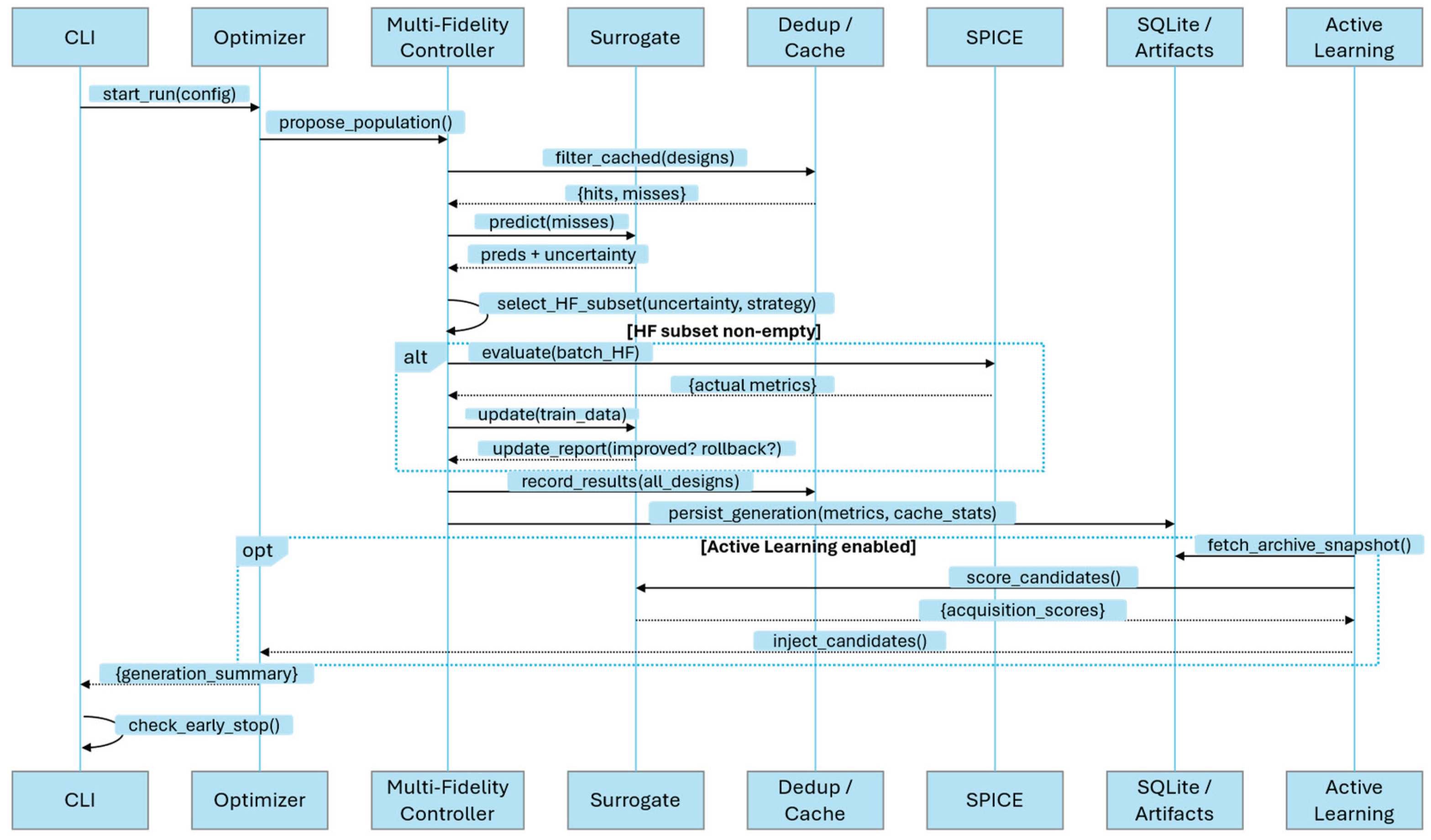

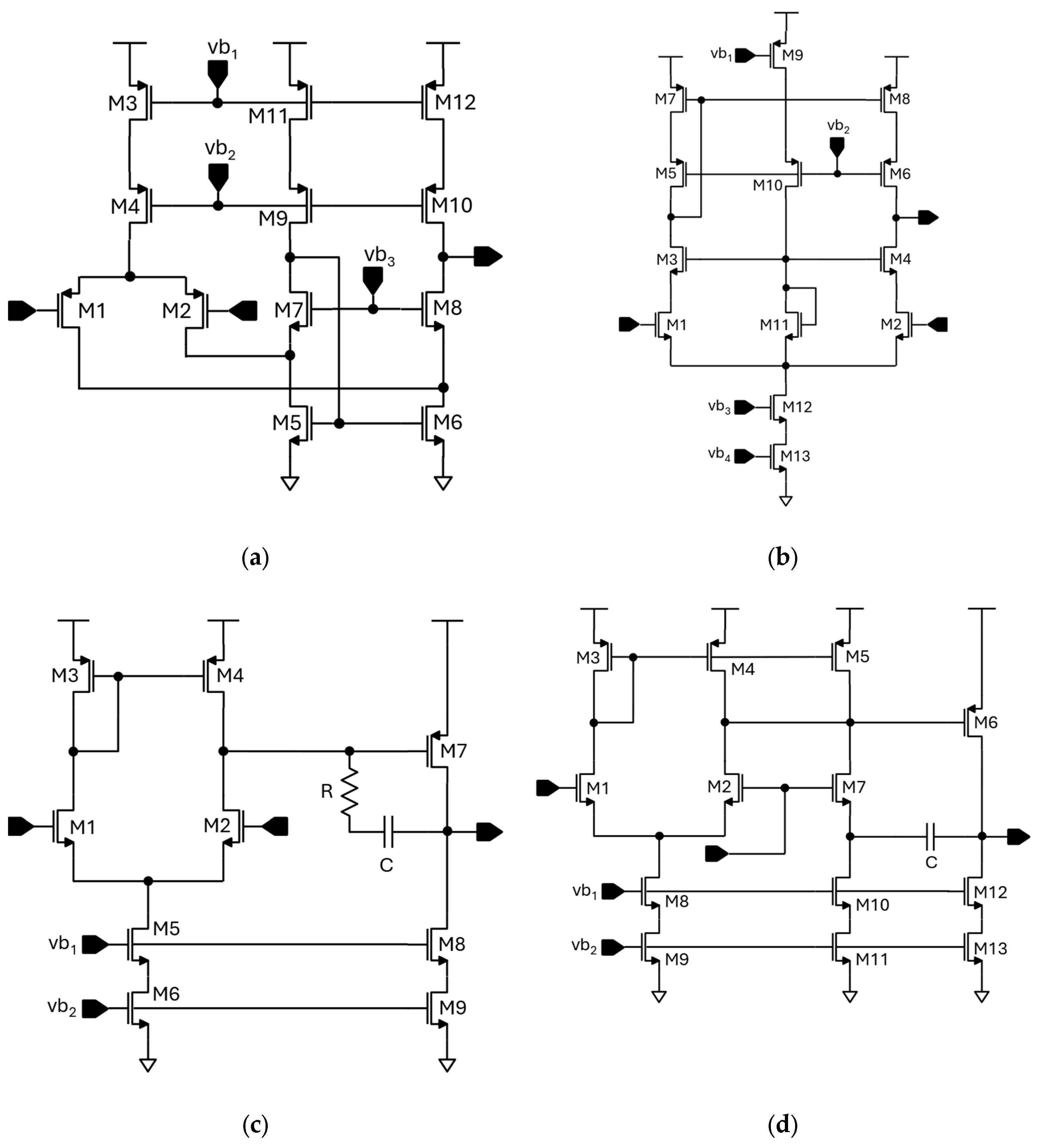

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the proposed optimization framework, focusing on simulator performance, algorithmic behavior, and Pareto-front quality across the different circuit topologies depicted in

Figure 8 and optimization modes. The discussion is organized to highlight (i) computational efficiency and scalability, (ii) genetic algorithm performance, and (iii) accuracy of surrogate and multi-fidelity predictions relative to SPICE truth.

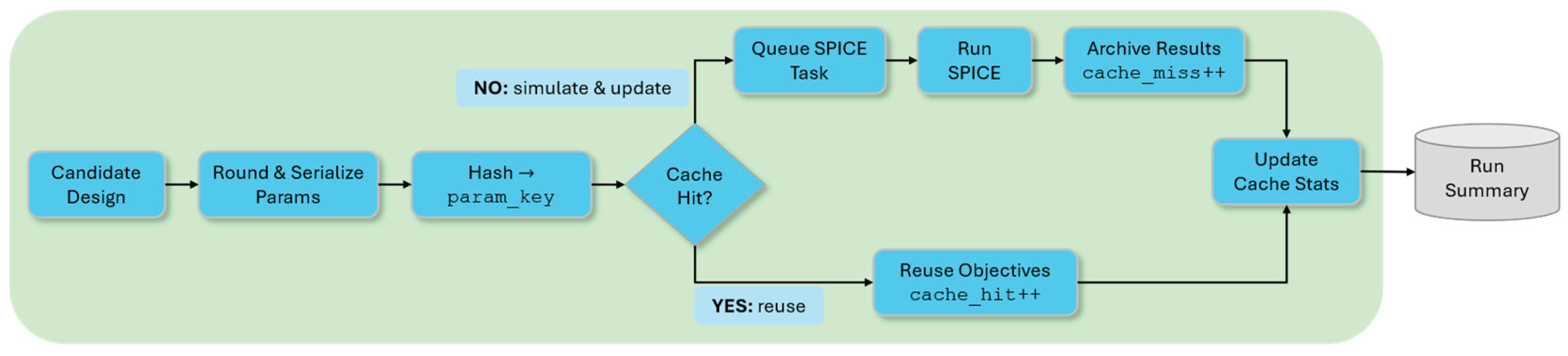

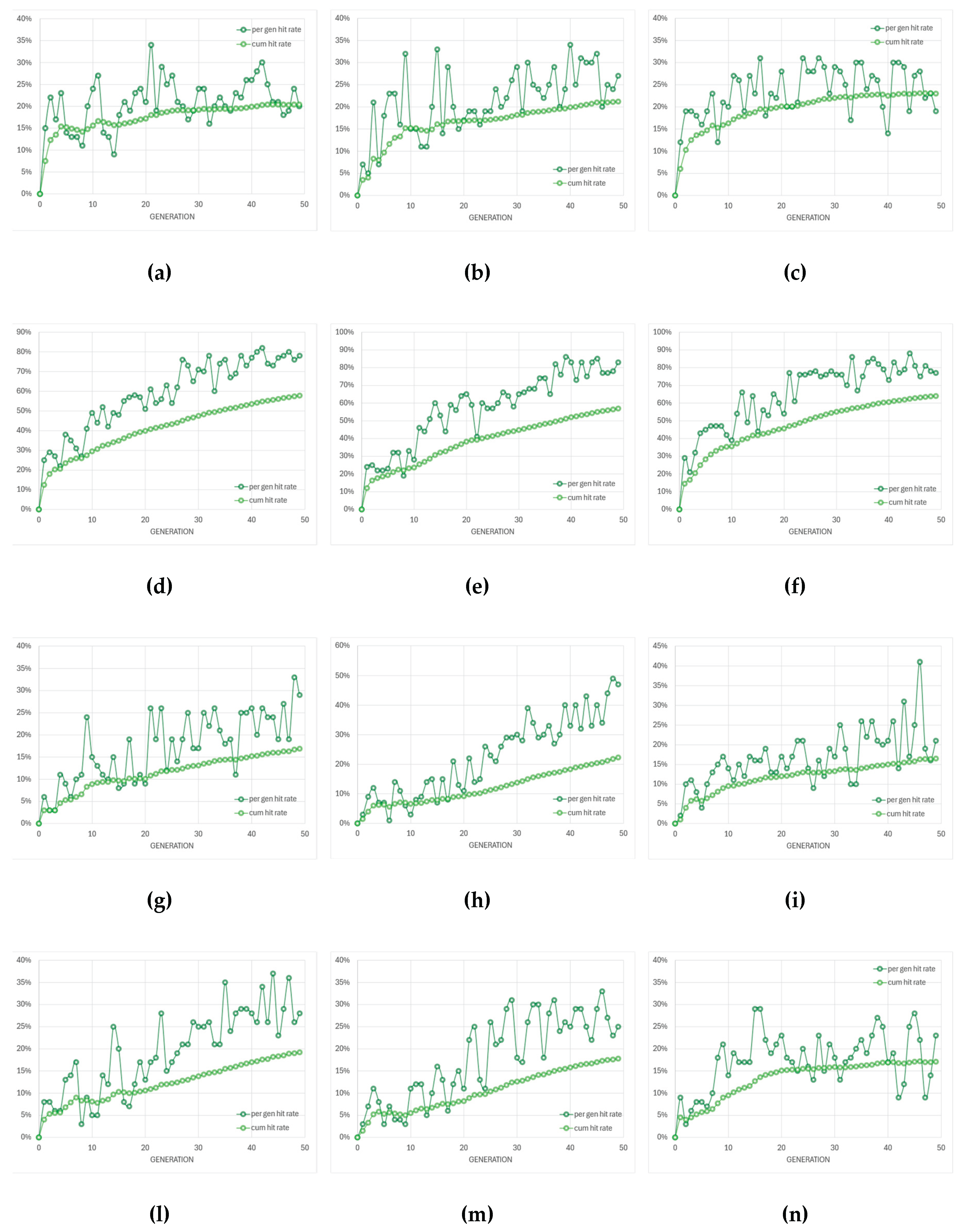

Figure 9 summarizes the evolution of cache-hit rates during SPICE-only optimization of the four amplifier topologies using three evolutionary algorithms. The cache system records and bypasses repeated circuit evaluations, thereby reducing computational cost without altering the optimization logic. Across all configurations, the hit rate exhibits a rapid growth phase during early generations—when the search space is densely revisited—followed by a gradual saturation as the optimizer approaches convergence.

This increase indicates that multiple individuals in later generations either replicate, or become very similar to, designs that were already evaluated in previous generations. As a consequence, more solutions can be served from the cache instead of requiring a new SPICE run, and the cumulative cache-hit curve rises monotonically.

The exact shape of this evolution is algorithm- and topology-dependent. Some algorithm/topology pairs show a smooth, monotonic rise in the cumulative cache-hit curve with relatively small oscillations in the instantaneous hit rate. This behaviour is consistent with fast convergence toward a narrow region of the search space. Other cases show intermittent bursts in the instantaneous hit rate followed by drops, which suggests that the optimizer occasionally re-injects diversity (e.g., by mutation) and briefly explores alternative regions before collapsing again toward previously known solutions. In other words, high, sustained cache-hit rates are a signature of strong convergence pressure; fluctuating cache-hit rates are a signature of continued exploration.

However, a high cache-hit rate—although beneficial for reducing total simulation time—also indicates a reduction in population diversity, as many individuals share identical parameter sets or converge toward the same local region of the search space. While this accelerates convergence, it also narrows the set of distinct circuit solutions that are analyzed. In contrast, lower or more erratic cache-hit traces correspond to broader exploration and higher diversity, at the expense of more SPICE simulations. This trade-off highlights the need to balance computational efficiency with design-space exploration: excessive caching efficiency may lead to premature convergence and a narrower set of analyzed designs, whereas moderate hit rates preserve diversity at the cost of longer run times. To summarize, the cache-hit trajectories in

Figure 9 do not simply indicate “better” or “worse” performance. Instead, they quantify the balance between (i) computational efficiency via reuse of simulated individuals and (ii) preservation of design-space diversity.

Figure 10 complements the previous results by showing how the instantaneous cache-hit behavior translates into the number of SPICE simulations and cache reuses per generation. In the early generations, almost all individuals are evaluated through new SPICE simulations, since the cache is empty, and population initially explores previously unvisited regions of the parameter space. Consequently, the number of cached evaluations is low and the computational cost per generation is high.

As the optimization proceeds, the number of cached individuals progressively increases, mirroring the rise of the cache-hit rate observed in

Figure 9. This shift reflects the optimizer’s tendency to revisit or reproduce already-evaluated circuit configurations as it converges toward stable design regions. For most topologies (Miller-compensated, folded-cascode, and telescopic-cascode), the behavior across algorithms is broadly consistent: after an initial phase dominated by new simulations, both simulated and cached counts evolve in a relatively balanced way. In these cases, cached reuse becomes relevant as the run progresses, but it does not overwhelmingly suppress new SPICE evaluations. This indicates that, although the optimizer begins to resample previously encountered designs (as also suggested by the rising cache-hit trends in

Figure 9), it continues to introduce fresh individuals at most generations. In practical terms, this means that convergence is happening, but exploration is not completely shut down. By contrast, the transistor-compensated differential amplifier is a clear exception. In this topology, cached evaluations dominate strongly over time, and the number of genuinely new SPICE simulations per generation drop more aggressively compared with the other topologies. This implies that the optimizer very quickly concentrates around a narrow subset of designs and then repeatedly reuses them. In other words, it reaches a “solution basin” early and keeps sampling within it instead of continuing broad exploration.

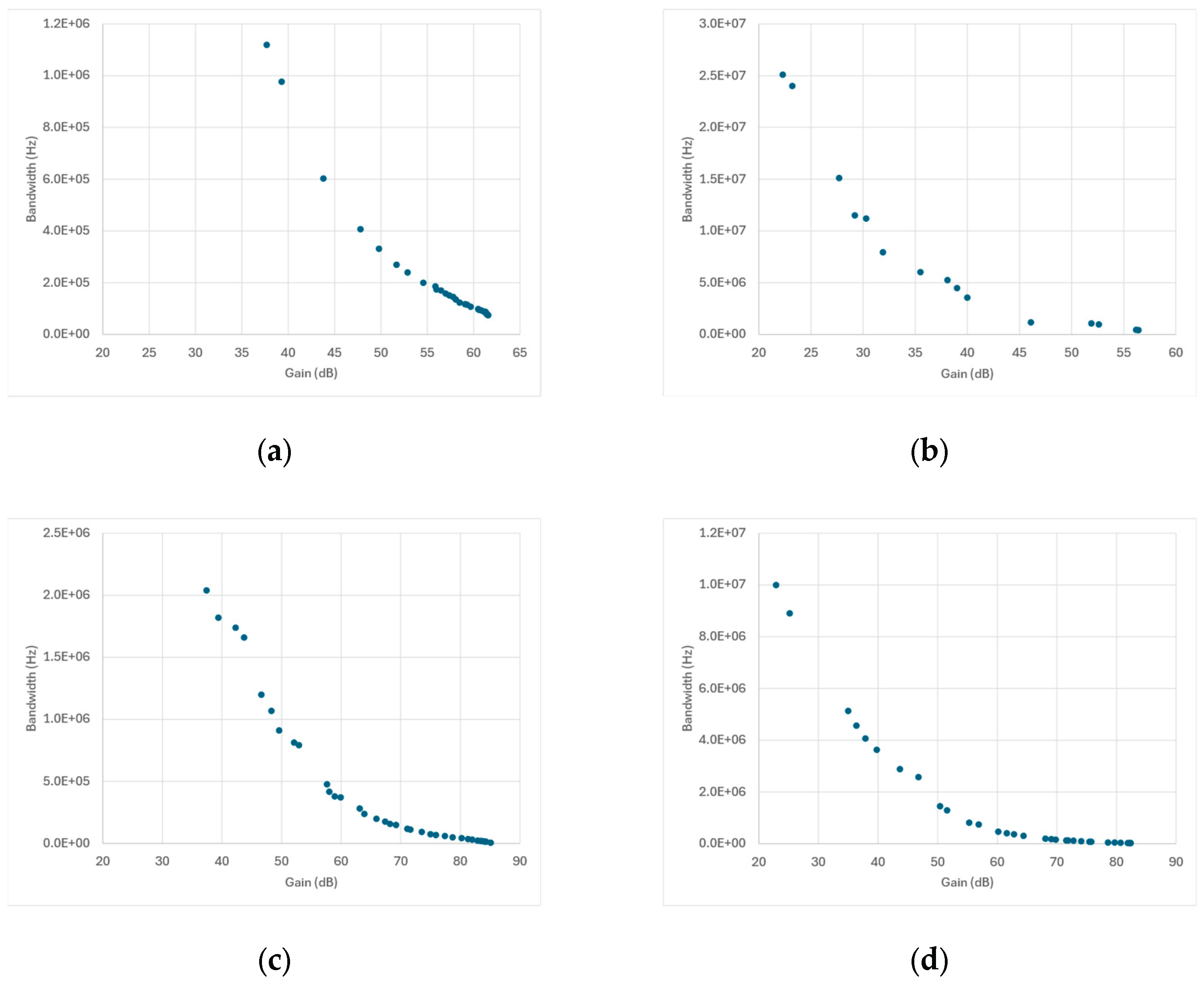

Figure 11 presents the Pareto fronts obtained from SPICE-only optimization for each amplifier topology and optimization algorithm. The data points collected throughout the optimization process naturally trace the expected two-dimensional trade-off between gain and bandwidth, allowing the extraction of a pseudo-Pareto front that reflects each algorithm’s convergence and design diversity.

Across most topologies, the overall front shapes are broadly similar: a well-defined, downward-sloping curve characteristic of the classical gain–bandwidth trade-off. However, the density and spread of the points along each front differ significantly among algorithms and correlate strongly with the cache behavior previously discussed in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

Topologies in which the number of new SPICE simulations per generation remained high—such as the Miller-, folded-, and telescopic-cascode amplifiers—show broader and smoother Pareto distributions, indicating that the optimizer continued to sample diverse design regions until late in the run. This sustained exploration produced fronts with a continuous coverage of intermediate gain-bandwidth combinations and fewer gaps between solutions.

In contrast, the transistor-compensated differential amplifier, where cached-design reuse dominated (

Figure 9d to

Figure 9f and

Figure 10d to

Figure 10f), exhibits markedly sparse Pareto fronts with large gaps between points. Here, the optimizer repeatedly recycled previously evaluated designs, leading to few genuinely new SPICE simulations per generation. As a result, the search concentrated early on a narrow region of the design space, producing only a limited number of distinct high-performing solutions. While this behavior yielded faster execution times, it reduced the ability to map the full continuum of gain-bandwidth trade-offs. The overall similarity across most topologies and genetic algorithms confirms that algorithmic effects are secondary to topology-dependent complexity and caching dynamics.

These results highlight that in SPICE-only optimization, caching efficiency and population diversity are inherently coupled, and both must be managed carefully to achieve physically meaningful design trade-offs.

Up to this point, the discussion has primarily focused on the accuracy, convergence behavior, and population diversity of the optimization framework, emphasizing how caching and algorithmic dynamics shape the distribution of evaluated designs. In the following analysis, the attention shifts from qualitative convergence characteristics to quantitative performance metrics, assessing the computational efficiency of the simulator itself. Specifically, two complementary metrics are considered: (i) the simulator throughput, defined as the number of completed SPICE simulations per second per generation, which reflects the effective processing rate of circuit evaluations; and (ii) the wall-clock time per generation, which quantifies the total elapsed time needed to complete all simulations within a single optimization generation. These metrics allow us to assess the impact of different execution strategies on overall simulation performance and scalability. Results obtained from fully sequential execution are compared against those achieved through parallelized runs, where multiple SPICE processes are executed concurrently. Two forms of parallelism are analyzed: lightweight process-based parallel execution, and distributed task scheduling via a local Dask cluster. Parallel execution was evaluated using two complementary configurations. In the first, process-based parallelism was employed by spawning eight concurrent SPICE processes, each handling an independent circuit evaluation within the same generation. In the second configuration, simulations were distributed over a local Dask cluster composed of five worker nodes. Due to hardware limitations of the test platform the Dask scheduler could not deploy more than five nodes, which constrained further scalability tests but still provided a representative measure of achievable local parallel speedup.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 compare the evolution of simulator throughput and wall clock time per generation achieved for the different amplifier topologies and optimization algorithms under different execution strategies. Across all algorithms and amplifier topologies, the throughput drift with generation is minimal, indicating that the computational workload per generation remains largely stable throughout the optimization process. The main variations in throughput stem not from algorithmic evolution but from the selected parallel-execution scheme.

When running on a single computer, process-based parallelism consistently yields higher throughput than the local Dask cluster. Spawning eight independent SPICE processes allows the simulator to exploit all CPU cores efficiently with limited coordination overhead. In contrast, the Dask cluster introduces additional scheduling and serialization costs that become non-negligible on a resource-constrained host system. Consequently, cluster execution provides little or no benefit on a single machine when compared to parallel process execution, though it remains advantageous for multi-node or distributed environments where its workload-balancing capabilities can be fully exploited.

The transistor-compensated differential amplifier displays a distinct trend: its wall-clock time decreases markedly with generation, regardless of execution mode. This reduction is not linked to parallelism but to its high cache-reuse ratio, which limits the number of new SPICE simulations as the run progresses. Nevertheless, its throughput remains constant and comparable to other topologies, revealing that the computational savings from cache reuse are offset by I/O latency and database-access overhead. In this case, execution becomes I/O-bound rather than compute-bound, as the simulator spends an increasing fraction of time performing cache lookups and data serialization.

Taken together,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 demonstrate that parallel execution markedly improves runtime efficiency on a single machine, but excessive cache reliance shifts the bottleneck from computation to storage. Under the tested hardware constraints, process-parallel execution offers the best trade-off between speed and resource usage, whereas cluster-based task scheduling becomes effective only when deployed on a physical multi-node cluster with greater memory and I/O bandwidth.

While the plots depicted in figures 12 and 13 illustrate temporal trends and instantaneous variations, aggregated averages provide a concise quantitative measure of each configuration’s efficiency and allow a direct estimation of relative speedups.

Table 3 summarizes these results, enabling comparison between sequential execution, process-based parallelism, and the local Dask cluster, and highlighting the practical performance gains achieved under each parallelization strategy.

Table 3 quantitatively summarizes the average simulation performance across all amplifier designs and execution strategies. In every case, parallel execution substantially reduces the wall-clock time per generation, yielding speedups between roughly 2× and 3× relative to sequential runs. The process-based mode consistently outperforms the local Dask cluster, providing higher throughput and greater speedup on the same hardware.

Speedup factors are broadly consistent across amplifier topologies and across NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, which indicates that the parallelization strategy dominates the overall runtime behavior more than the specific optimization algorithm. It is important to note that these averages capture global efficiency but do not fully reflect per-generation dynamics such as the strong cache-driven wall-clock reduction observed for the transistor-compensated op-amp. That behavior, discussed in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, is local to later generations and is partially hidden when values are averaged over the entire run.

3.3.1. MOEA/D Algorithm

In addition to the classical multi-objective evolutionary algorithms analyzed so far—namely NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2—the MOEA/D (Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition) was also employed to benchmark simulator performance. This algorithm deserves separate analysis because, unlike the aforementioned methods, it is not a genetic algorithm in the strict sense.

While NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2 rely on population-level genetic operators—such as crossover, mutation, and tournament-based selection—to evolve candidate solutions through Pareto ranking and crowding measures, MOEA/D adopts a fundamentally different approach. It decomposes the multi-objective problem into multiple scalar subproblems, each associated with a distinct weight vector, and optimizes them simultaneously in a cooperative neighborhood framework. Instead of relying on stochastic recombination, MOEA/D focuses on localized search and information sharing among neighboring subproblems, promoting convergence along well-distributed regions of the Pareto front with reduced genetic diversity.

This structural distinction has important implications for simulation workload and parallelization efficiency. Because MOEA/D updates subproblems incrementally and performs fewer global population-wide operations, its computational pattern differs significantly from that of classical genetic algorithms.

As a result, the external parallel-execution strategies previously employed—such as process spawning or Dask-based clustering—are not applicable here. Performance optimization is instead achieved internally through the parallelization backend provided by PyMOO, one of the core libraries on which our simulator is built.

Accordingly, this section evaluates simulator performance under MOEA/D by analyzing both the global throughput (total SPICE simulations per second over the full optimization run) and the overall wall-clock time, along with the shape and convergence quality of the final Pareto front. This approach allows a consistent comparison with the other algorithms while recognizing that, in MOEA/D, these metrics describe the aggregate efficiency of the entire optimization process rather than per-generation behavior.

Figure 14.

Pareto-optimal fronts obtained using the MOEA/D for the four operational-amplifier topologies under test: (a) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (b) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (c) folded-cascode op-amp; (d) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Figure 14.

Pareto-optimal fronts obtained using the MOEA/D for the four operational-amplifier topologies under test: (a) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (b) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (c) folded-cascode op-amp; (d) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

The MOEA/D configuration used in this work was selected primarily to ensure fair comparison with the other optimization algorithms (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2). For consistency, analogous settings were adopted across all methods—namely, a population size of 100 (corresponding to 100 subproblems in MOEA/D), a crossover probability of 0.9, a mutation probability of 0.1, and a similar early-stopping criterion (see

Table 2). This common configuration allowed a balanced assessment of simulator performance under equivalent computational workloads and solver conditions, including identical SPICE analysis parameters and solver tolerances.

Under these settings, the Pareto fronts generated by MOEA/D exhibited the expected gain–bandwidth trade-off but showed a sparser solution distribution, with most non-dominated points clustered toward the high-gain region. This outcome reflects our conservative configuration biased toward fast local convergence rather than broad design-space exploration. Specifically, the combination of high crossover probability, low mutation rate, and strong parent-selection locality (delta = 0.9, neighbors = 15) emphasizes exploitation over exploration. The Tchebycheff decomposition further reinforces this tendency by driving optimization toward extreme objective values. Namely, Tchebycheff decomposition tends to favor the objective that is easier to improve—in this case, gain—so the search mostly converges toward high-gain regions while exploring the low-gain, high-bandwidth trade-offs less extensively.

Table 4 shows the summary of MOEA/D optimization statistics using sequential execution. All MOEA/D simulations processed 5000 design evaluations (50 iterations over 100 individuals) under identical optimization and SPICE-solver conditions.

The transistor-compensated differential amplifier exhibits the highest cache-reuse ratio (≈ 91%), confirming strong convergence toward a limited set of recurring designs. However, its throughput remains low (≈ 6.5 sim/s) because frequent database lookups dominate runtime once cache hits prevail. The other amplifier topologies show similar cache-hit levels (≈ 70–74%) and slightly higher throughputs of 9–13 sim/s, consistent with a more balanced mix of cached and new evaluations.

Despite exploiting PyMoo’s internal parallel-evaluation backend, the results summarized in

Table 5 indicate that parallel execution does

not yield any measurable performance improvement over the sequential MOEA/D runs. Across all amplifier topologies, the wall-clock times remain comparable or even slightly higher, confirming that the internal thread-level parallelism introduces additional scheduling and synchronization overhead that offsets the potential benefit of concurrent SPICE evaluations.

The throughput values (≈ 5–13 sim/s) are effectively identical to those of the sequential configuration, demonstrating that evaluation latency is dominated by SPICE solver execution and cache I/O rather than CPU availability. Similarly, the cache-hit ratios remain in the 0.68–0.77 range (and 0.93 for the transistor-compensated amplifier), showing that parallelization neither enhances design reuse nor affects the caching dynamics established by MOEA/D’s decomposition-based search. These results confirm that, on a single-machine setup, PyMoo’s internal parallelization provides no runtime benefit compared with sequential execution, as the optimization remains constrained by SPICE simulation cost and I/O-bound cache operations rather than computational parallelism.

3.3.2. Surrogate-Guided Optimization

The surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) strategy was also employed to accelerate the multiobjective analog circuit design process by coupling machine-learning-based surrogate models with periodic SPICE truth evaluations. In the adopted configuration, the optimization proceeded with a truth interval of two generations—meaning that every two evolutionary generations, the surrogate model was updated and validated against ground-truth SPICE simulations. Each verification stage (truth sweep) comprised a truth batch size of 16, corresponding to the number of candidate designs selected by the surrogate for SPICE evaluation in each update cycle. As a result, only 3.5% of all evaluated individuals were subjected to full SPICE simulation, while 96.5% of evaluations relied on fast surrogate inferences. This hybrid approach drastically reduced the computational burden, yielding an approximate 94% reduction in total simulation time compared to pure SPICE-based optimization.

Surrogate predictions were deliberately not parallelized because they already execute as highly efficient, batched vector operations that fully exploit optimized numerical kernels on the CPU. In this context, the computational asymmetry between model inference and circuit-level SPICE evaluations is extreme—predictions are orders of magnitude faster, so distributing them across multiple processes would introduce overheads that outweigh any potential gains. Batched inference ensures optimal use of CPU vector units and system memory without duplicating model parameters across processes, while avoiding thread contention and preserving deterministic numerical behavior essential for reproducibility in evolutionary loops. Consequently, parallel execution was applied only to the high-latency SPICE truth evaluations, where it brings tangible benefits provided that the batch size is sufficiently large—but not in this case, where the truth batch represented a small fraction of the overall workload. Under these conditions, only surrogate model training benefits meaningfully from parallelization, while inference remains an in-process, vectorized operation that is both simpler and more stable on a CPU-only system. As a result, parallel execution provided no significant additional speedup, and comparable runtimes were observed across all genetic algorithms under test.

The performance of the surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) process was assessed by jointly analyzing the quality of the resulting Pareto fronts and the predictive accuracy of the surrogate models. The Pareto front evaluation provides a direct measure of how effectively the SGO strategy captures the trade-off surface between conflicting design objectives, revealing whether the surrogate-driven exploration converges toward the true multiobjective optimum identified by SPICE ground-truth evaluations. Complementarily, the predictive performance of the surrogate models was quantified using the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) computed over each truth batch.

MAE was selected as the principal accuracy metric for several reasons directly aligned with the dynamics of surrogate-assisted optimization. First, it offers direct interpretability in the same units as the design objectives (e.g., dB for gain, Hz for bandwidth), allowing engineers to immediately assess the average prediction deviation without requiring squaring or square-root transformations as in MSE or RMSE. This makes MAE particularly useful for adaptive control of surrogate updates, such as checkpoint acceptance and rollback decisions during the optimization loop.

Second, MAE exhibits robustness to outliers, which are common in analog circuit design where certain candidates may produce invalid or unstable operating points. Unlike MSE, which amplifies large errors quadratically and can distort model assessment, MAE treats all deviations linearly, ensuring that a few extreme mispredictions do not overshadow the typical predictive behavior across the Pareto front. This stability translates into more reliable model update and rollback logic.

Third, MAE provides consistent scaling across multiple objectives with heterogeneous numerical ranges—such as gain (20–100 dB) and bandwidth (10³–10⁹ Hz) —without biasing the aggregate error toward high-magnitude variables. The metric also produces a stable and predictable convergence signal: thresholds like rollback if MAE increases by > 0.15 can be tuned intuitively because MAE’s scale remains bounded and insensitive to isolated large errors.

Finally, MAE is computationally efficient and empirically validated in our workflow. It requires only the sign of the residual during backpropagation, reducing numerical overhead and improving stability during online surrogate updates. In practice, the MAE exhibits a generally decreasing trend as the number of generations increases, showing an oscillatory behavior that reflects the adaptive refinement of the surrogate model through successive truth evaluations. This evolution indicates progressive improvement in predictive accuracy and stability, further confirming the effectiveness of the adopted SGO strategy.

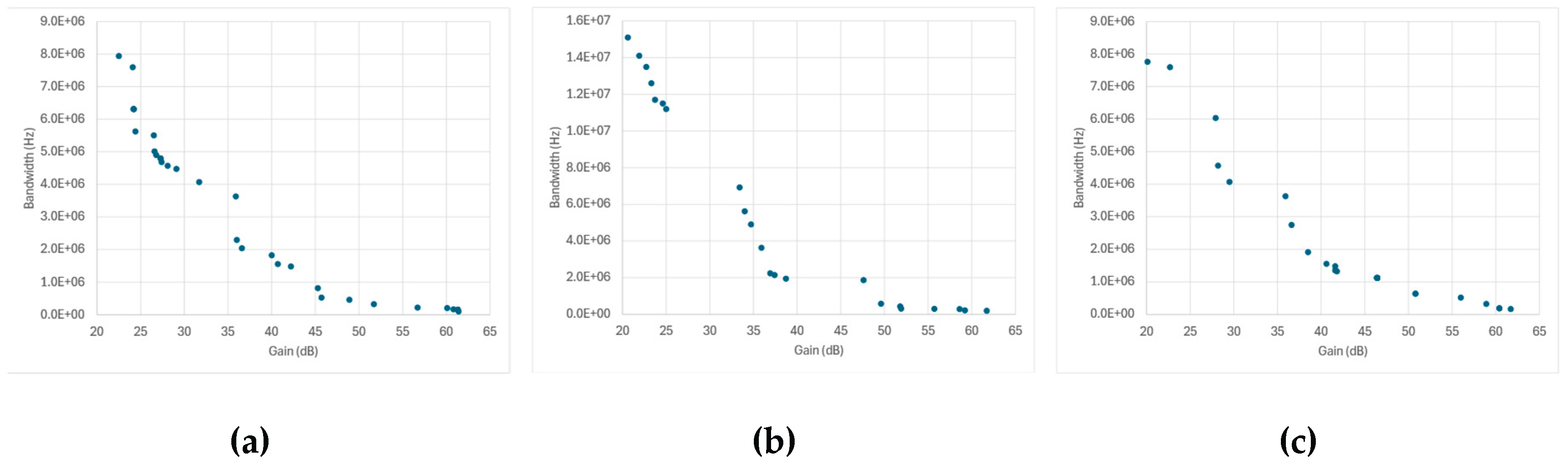

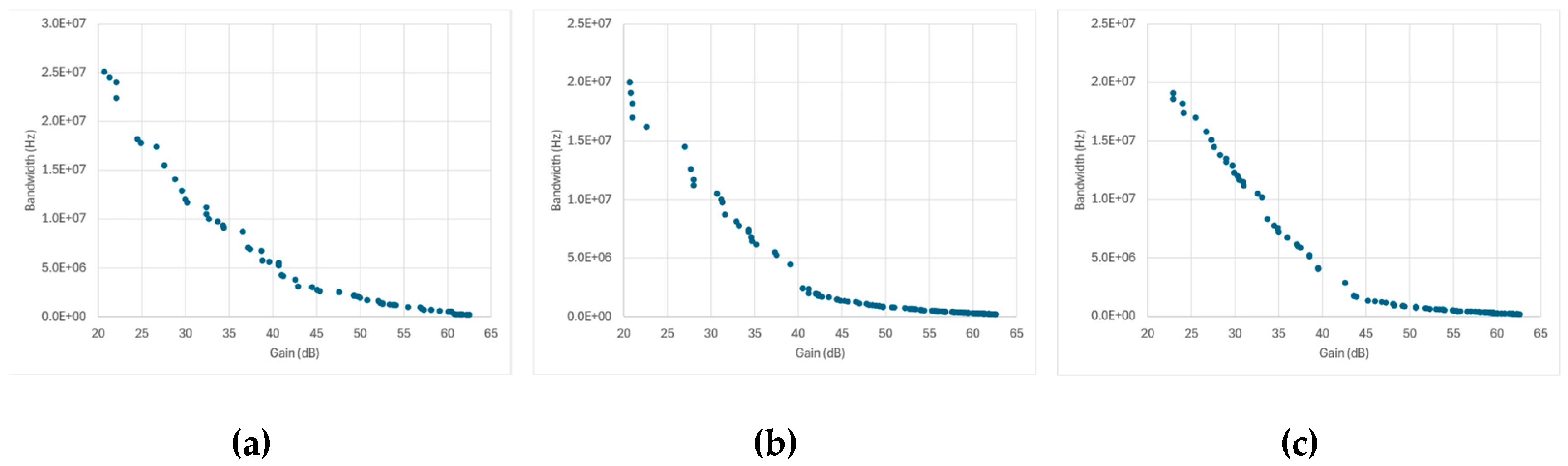

The Pareto fronts presented in

Figure 15 confirm that surrogate-guided optimization effectively captures the trade-off between gain and bandwidth across all amplifier topologies, producing fronts consistent with the expected hyperbolic trend observed in pure SPICE-based optimization. For the Miller- and telescopic-cascode amplifiers, the predicted fronts show good coverage of the of the objective space with a coherent, monotonic profile—consistent with well-behaved surrogate generalization. The folded-cascode case exhibits a similar overall quality, with the notable exception of a slight clustering in the high-gain / low-bandwidth region, indicating local over-exploitation of that corner of the trade-off.

A topology–algorithm interaction emerges for the transistor-compensated differential amplifier under SPEA2 (see

Figure 15f)

. Post-analysis of the surrogate inference logs revealed that, in this case, the surrogate performed a large number of redundant predictions—assigning identical output metrics to multiple distinct design vectors which led to overlapping points and a degraded Pareto front. This redundancy is compatible with a training set locally saturated in similar samples and with SPEA2’s archive dynamics, which can preserve minimally distinct individuals once dominance relations stabilize. By contrast, NSGA-II and NSGA-III—through crowding and reference-direction mechanisms—are less susceptible to this collapse and yield more evenly distributed predicted fronts.

These observations underscore the need to periodically re-enrich the surrogate with diverse ground-truth samples (e.g., targeted truth checks in sparsely populated regions) and to monitor prediction uniqueness to prevent accumulation of duplicates, especially for archive-based algorithms and topologies prone to local clustering.

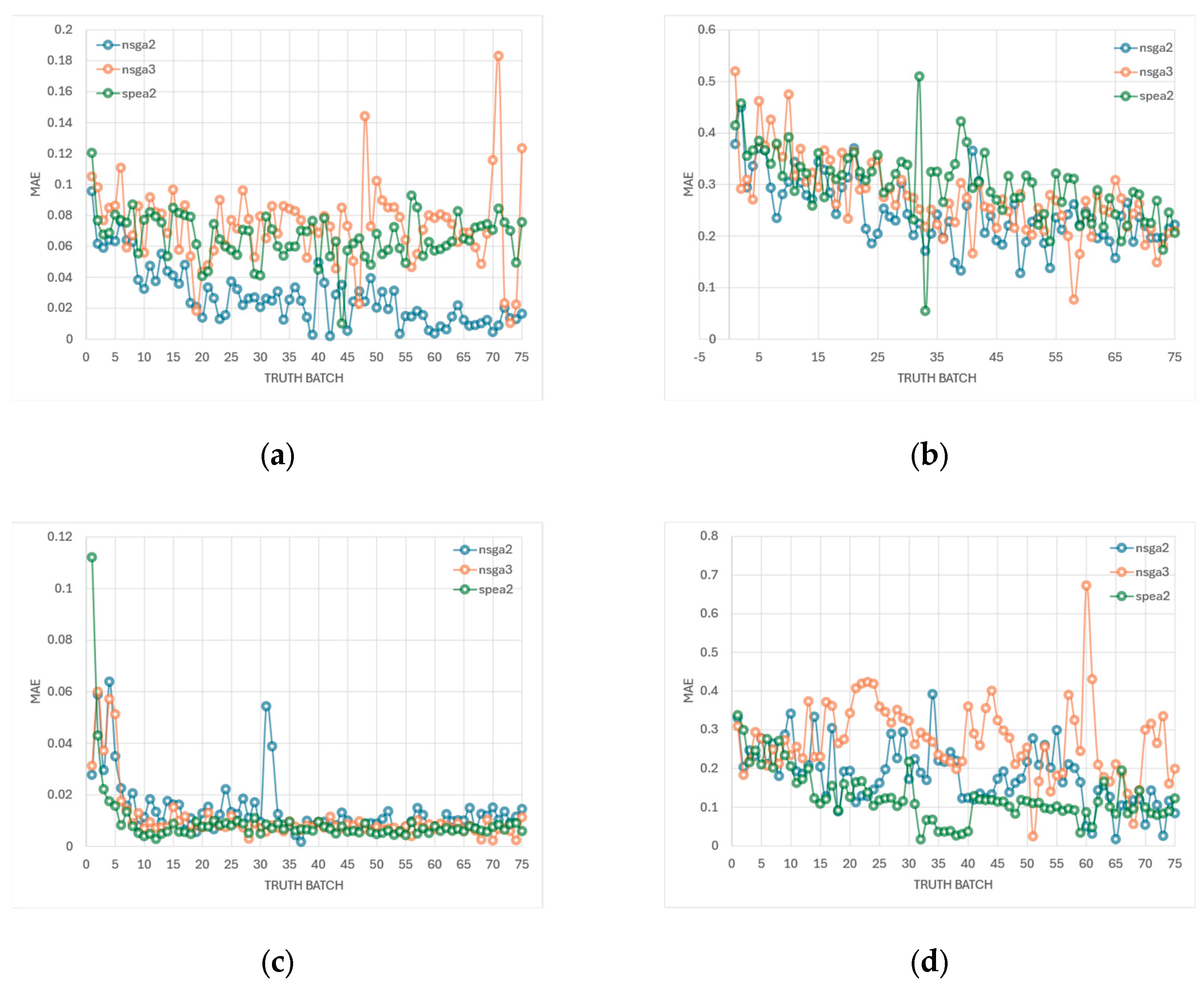

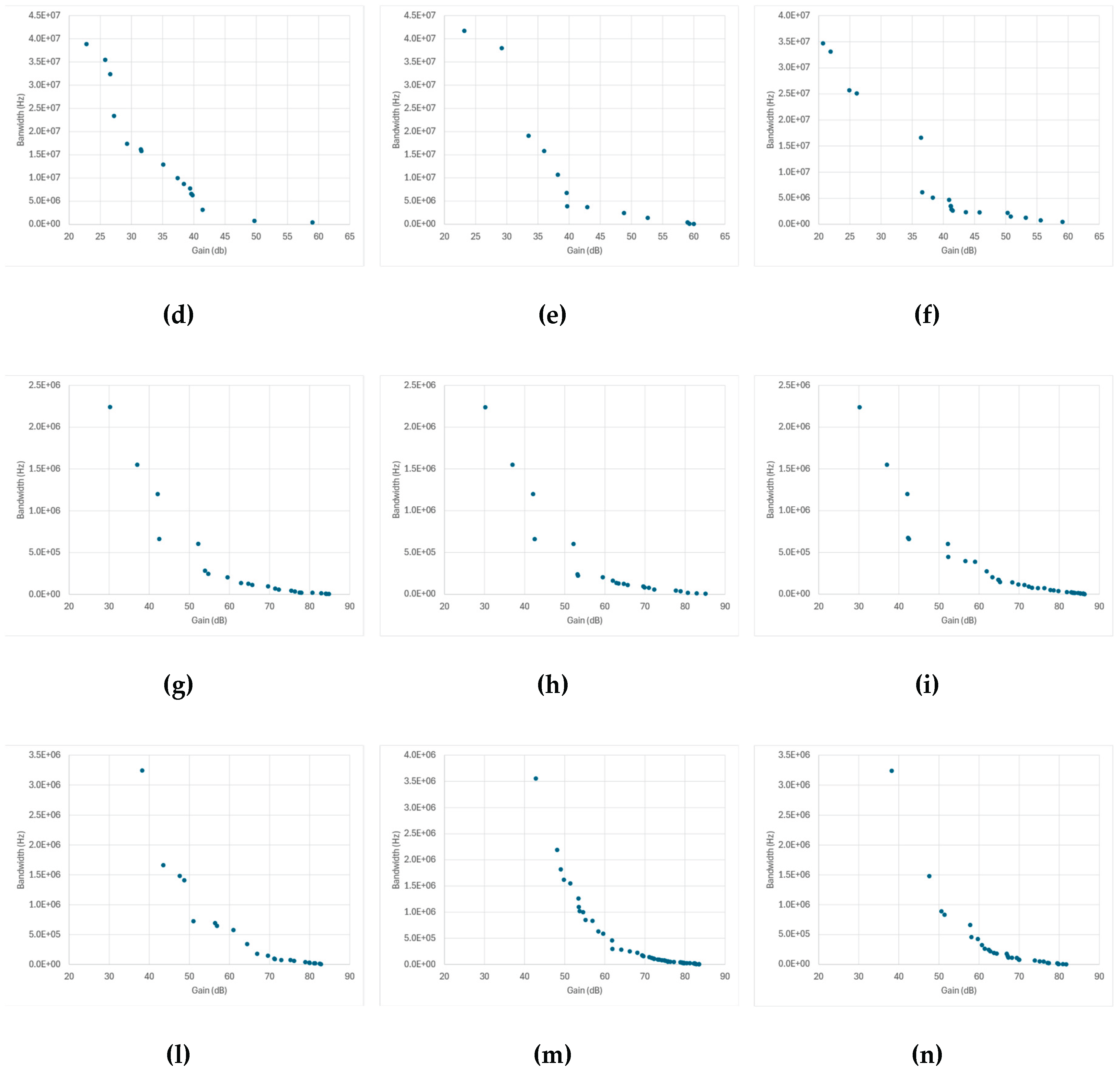

The MAE trends in Figure 16 confirm that, in most cases, surrogate accuracy improves progressively with successive ground-truth updates, following the expected pattern of oscillatory but overall decreasing error. For the Miller-compensated amplifier, NSGA-II shows a rapid drop in MAE that stabilizes early at a low error level, whereas SPEA2exhibits steadier oscillations with a slower but continuous decline. NSGA-III, instead, presents wider fluctuations, indicating stronger corrective adjustments as the optimizer compensates for larger initial prediction discrepancies. In contrast, the folded-cascode amplifier displays a smoother downward trend across all algorithms, reaching consistently low MAE values that reflect stable convergence and effective surrogate refinement.

The telescopic-cascode amplifier follows a similar overall behavior but with more irregular fluctuations. This pattern likely arises from the amplifier’s higher sensitivity to device-level parameter interactions which amplify small modeling inaccuracies and cause local prediction corrections to vary more strongly between truth batches.

Figure 15.

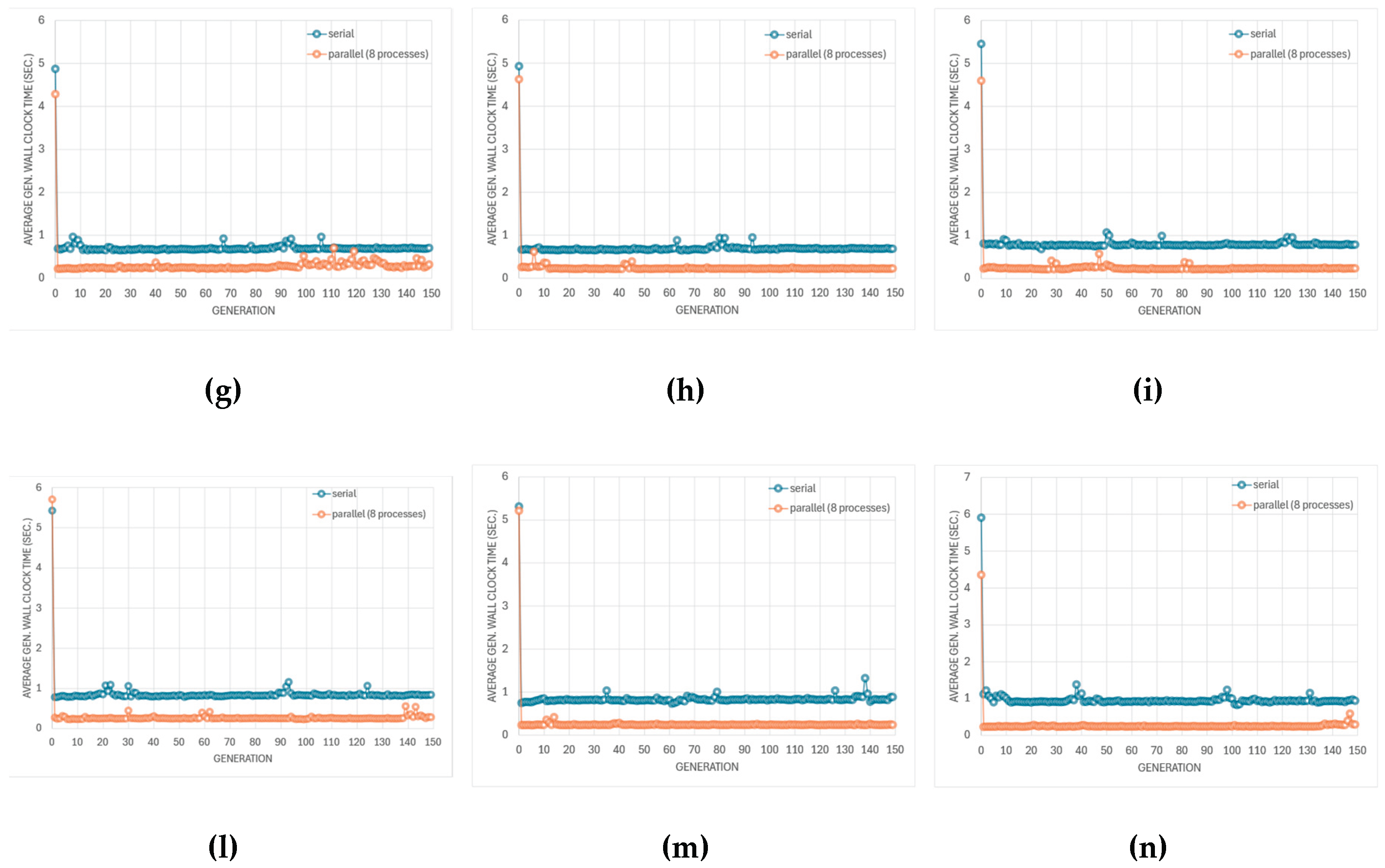

Pareto fronts obtained through surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively). The explored design space is and : (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Figure 15.

Pareto fronts obtained through surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively). The explored design space is and : (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

A distinctive behavior is observed for the transistor-compensated differential amplifier, where all three algorithms show a monotonic decrease of MAE with generation, comparable to the other topologies. This confirms that, despite the poor Pareto front observed for this case with SPEA2, the surrogate predictions remain accurate overall. The degradation in the Pareto front thus stems not from high prediction error, but from redundant surrogate outputs, where distinct input parameter combinations yield identical gain and bandwidth values. Such redundancy limits design diversity but does not compromise the surrogate’s numerical accuracy, which continues to improve steadily across generations.

The oscillatory but steadily declining MAE curves validate the soundness of the SGO workflow and demonstrate that the surrogate maintains effective predictive accuracy across generations, with local variations arising mainly from topology-dependent model complexity and algorithmic sampling diversity.

Figure 16.

Evolution of the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of the surrogate model during surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) for the four amplifier topologies under study. Curves report MAE values versus truth batch index for NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, averaged over all predicted individuals per generation (ground-truth evaluations are performed every two generations to update the surrogate and measure prediction accuracy). Each plot corresponds to: (a) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (b) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (c) folded-cascode op-amp; (d) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Figure 16.

Evolution of the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of the surrogate model during surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) for the four amplifier topologies under study. Curves report MAE values versus truth batch index for NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, averaged over all predicted individuals per generation (ground-truth evaluations are performed every two generations to update the surrogate and measure prediction accuracy). Each plot corresponds to: (a) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (b) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (c) folded-cascode op-amp; (d) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Finally,

Table 6 complements the MAE-evolution analysis by providing quantitative statistics over 12 independent SGO runs for each amplifier topology. The results confirm the overall improvement in surrogate accuracy observed in Figure 16, with the MAE consistently decreasing between the initial, final, and best-recorded values across all designs. The folded-cascode amplifier achieves the lowest median final MAE (≈ 0.022), reflecting its smoother response surface and higher predictability. The Miller-compensated amplifier follows closely, although the wider range between runs indicates moderate sensitivity to the specific training trajectory. The telescopic-cascode amplifier maintains a clear reduction in MAE but with larger residual errors, consistent with its more complex biasing and coupling behavior. The transistor-compensated differential amplifier remains the most challenging case, exhibiting the highest initial and final MAEs, yet still demonstrating a consistent downward trend.

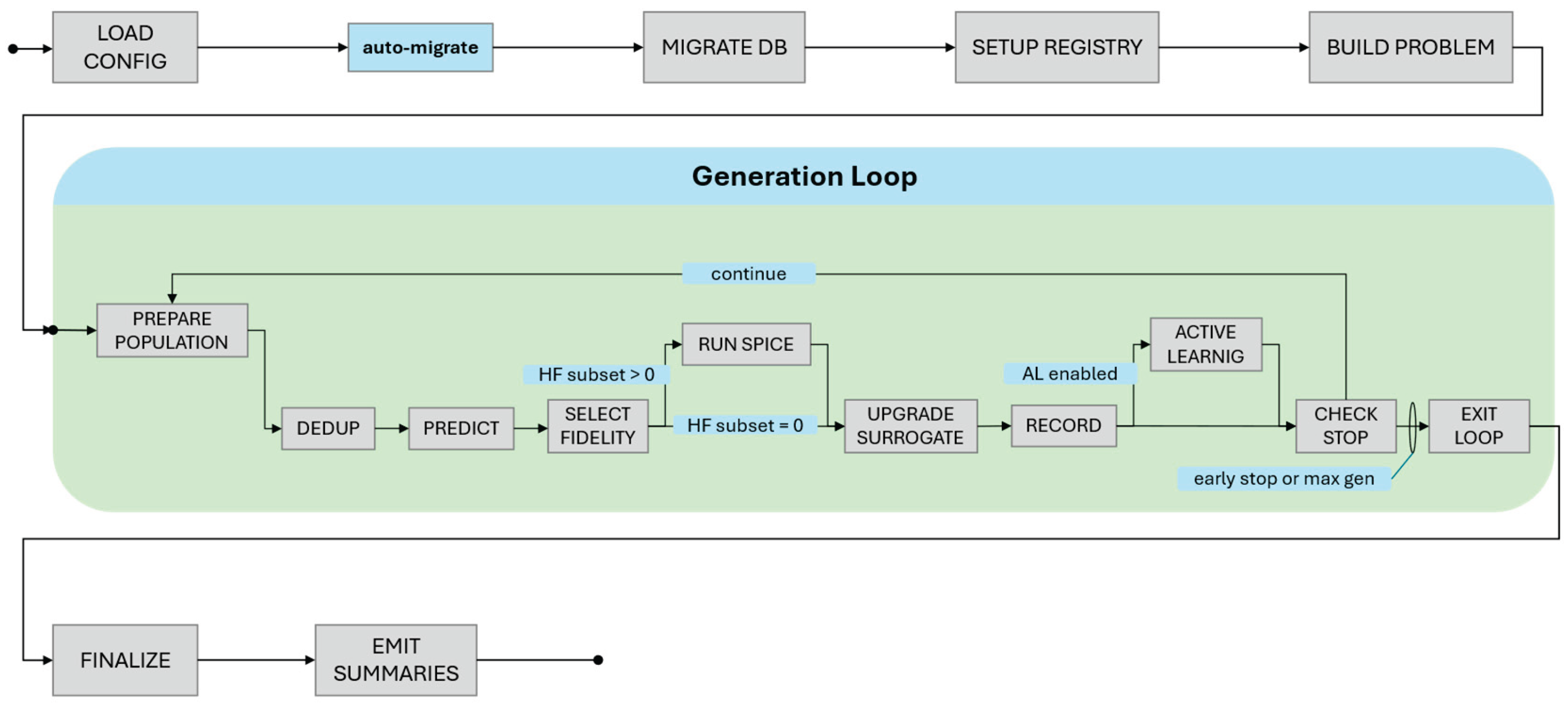

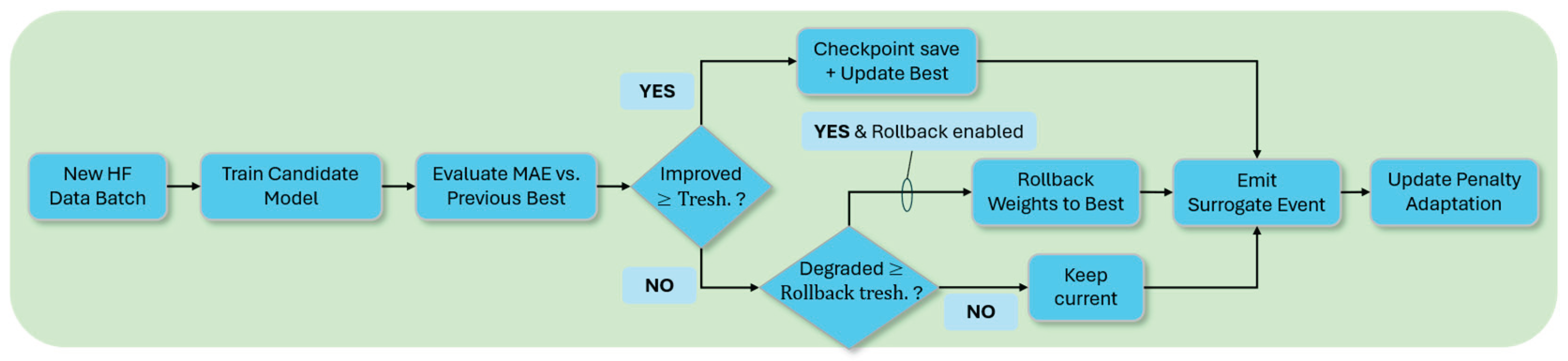

3.3.3. Multi-Fidelity Adaptive Optimization

While surrogate-guided optimization (SGO) relies on a fixed verification schedule with periodic ground-truth batches evaluated at constant intervals, multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) introduces a dynamic fidelity allocation strategy that adapts evaluation effort based on real-time uncertainty quantification. The key distinction lies in the decision process: SGO verifies a predetermined fraction of candidates using SPICE at regular generational intervals, whereas MFO employs an adaptive fidelity controller that assigns high-fidelity evaluations to selected candidates according to composite scoring criteria—such as uncertainty-driven, hybrid exploitation–exploration, or hypervolume-proxy strategies.

This adaptive scheme is complemented by an uncertainty penalty mechanism that continuously adjusts the penalty weight applied to surrogate predictions in proportion to the current mean uncertainty relative to a predefined target value. When the global uncertainty exceeds this threshold, the penalty weight increases, discouraging exploration in regions of low surrogate confidence; conversely, when the uncertainty falls below the target, the penalty is relaxed, enabling broader exploration of the design space.

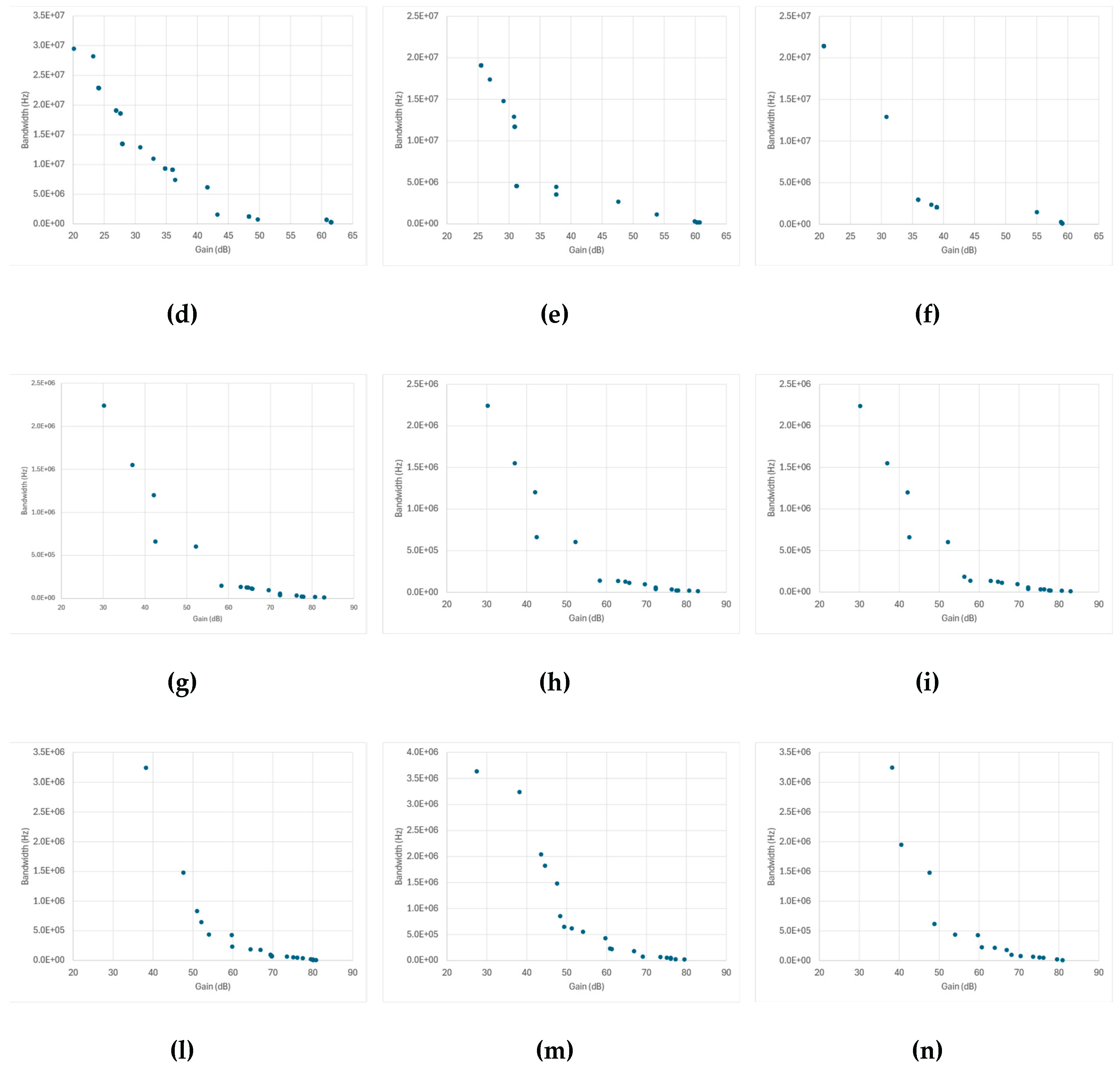

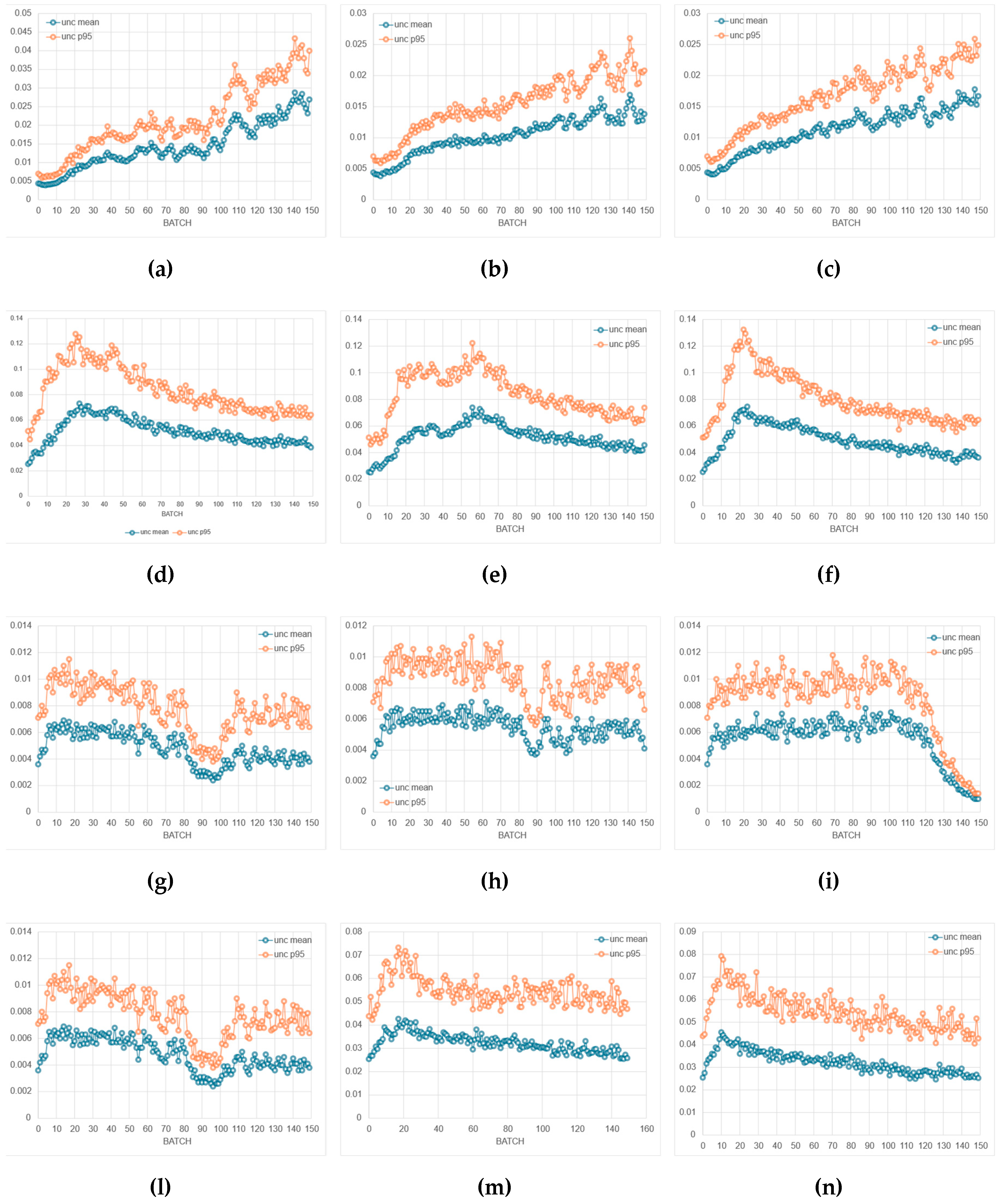

Through this closed-loop adaptation, MFO automatically balances computational cost and prediction confidence throughout the optimization process. This makes it particularly effective for problems where the surrogate’s reliability is non-uniform across the design space or evolves as additional ground-truth data are incorporated. The defining feature of MFO is therefore the shift from a schedule-based verification policy to a confidence-based allocation of computational resources, allowing SPICE evaluations to focus where the surrogate is least reliable while sustaining aggressive exploration in well-modeled regions. The Pareto fronts in Figure 16 demonstrate that multi-fidelity optimization successfully enhances the consistency and smoothness of the predicted trade-offs between gain and bandwidth compared with the fixed-interval surrogate-guided approach. Across all amplifier topologies, MFO produces denser and more uniformly distributed Pareto fronts, indicating that adaptive fidelity allocation effectively concentrates high-fidelity evaluations in regions where the surrogate’s uncertainty is higher, while relying on low-fidelity inference in well-modeled areas.

Figure 16.

Pareto fronts obtained through multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively). The explored design space is and : (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Figure 16.

Pareto fronts obtained through multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively). The explored design space is and : (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

For the Miller-compensated and folded-cascode amplifiers, all three algorithms converge to well-defined, continuous fronts that closely approximate the expected monotonic gain–bandwidth relation. The improvement over the single-fidelity surrogate-guided optimization is particularly evident in the edge regions of the Pareto front, where MFO avoids the local sparsity previously observed due to fixed truth intervals.

The telescopic-cascode amplifier also benefits from the adaptive scheme, showing a more stable front with fewer scattered or discontinuous points. This suggests that MFO’s uncertainty-driven truth allocation efficiently mitigates the effects of local nonlinearity and parameter coupling that previously introduced variability in surrogate-only predictions. A notable improvement is seen in the transistor-compensated differential amplifier, especially for SPEA2, where the degenerate Pareto front observed in the surrogate-guided case is now replaced by a more evenly spread set of trade-off solutions. The adaptive uncertainty controller in MFO selectively reinforces ground-truth verification for individuals exhibiting high predictive variance, thus breaking the redundancy that led to overlapping predictions in the previous configuration.

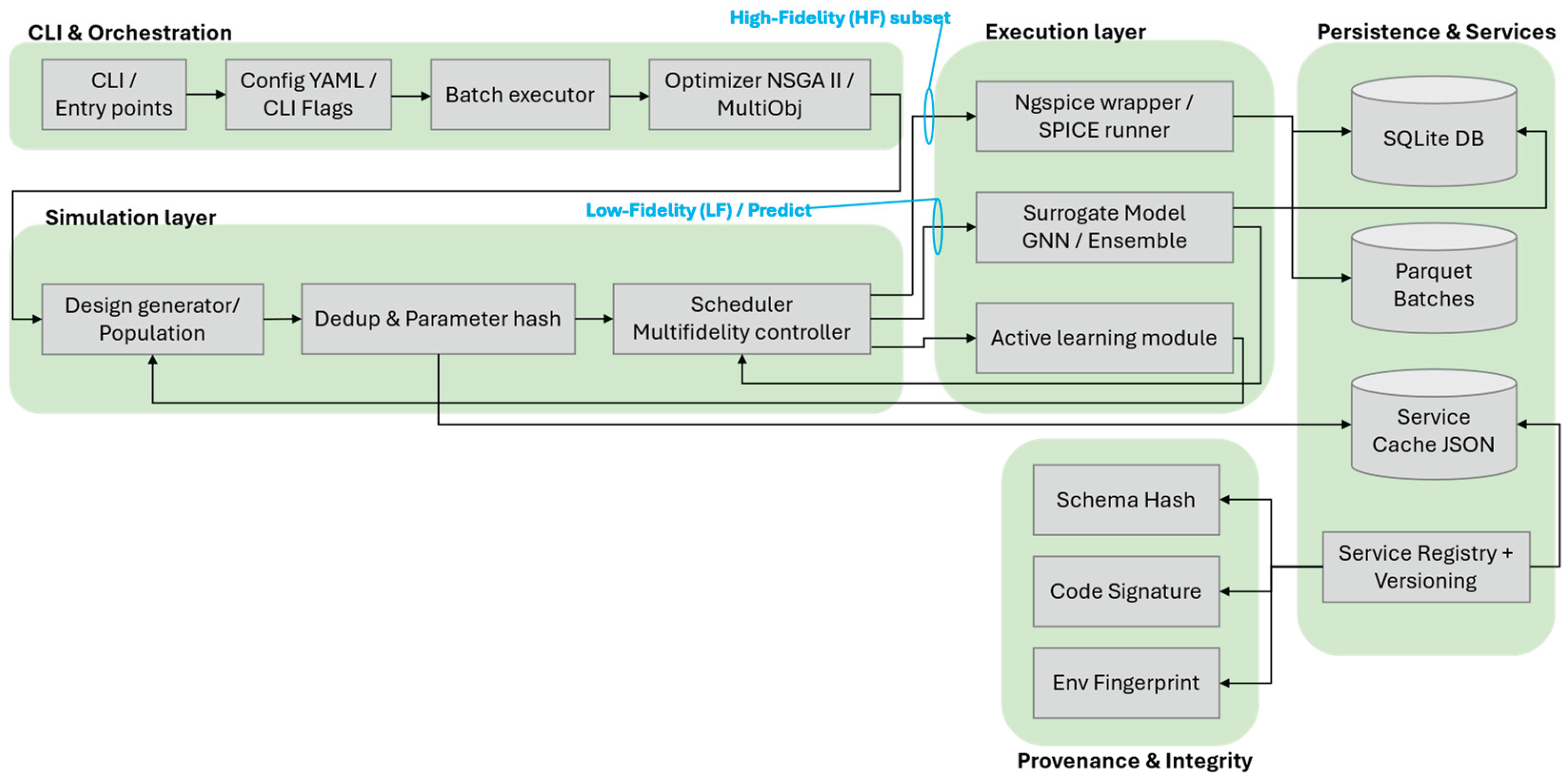

The multi-fidelity optimization framework monitors two key uncertainty metrics to guide the adaptive allocation of high-fidelity SPICE simulations: UncMean (mean predicted uncertainty across the population) and UncP95 (95th percentile uncertainty). These metrics quantify the surrogate model’s confidence in its predictions, with lower values indicating higher reliability.

The fidelity allocation mechanism employs a composite scoring approach rather than simple threshold-based selection. While the system uses an initial uncertainty threshold of 0.15 to flag candidates potentially requiring SPICE verification, the actual selection is rank-based: candidates are scored using normalized uncertainty combined with exploitation or diversity metrics (depending on the acquisition strategy), and the top-N are allocated for SPICE evaluation. The simulator has been configured so that the target SPICE fraction is adaptively adjusted between 10% and 30% of the population based on the proportion of candidates exceeding the threshold. To prevent excessive reliance on uncertain predictions, the framework includes an adaptive penalty mechanism that targets a mean uncertainty of 0.3. When UncMean exceeds this target, a penalty weight is gradually increased (default adaptation rate: 0.15 per generation, maximum weight: 2.0), adding a penalty term proportional to prediction uncertainty to the objective function. This encourages the optimizer to explore regions where the surrogate is more confident. Conversely, when UncMean falls below the target, the penalty decreases.

In our experiments across four op-amp topologies, uncertainty metrics remained consistently well below both thresholds (UncMean < 0.15, UncP95 < 0.15), indicating excellent surrogate quality throughout optimization. This resulted in penalty weights remaining near zero and enabled sustained high surrogate reliance (89.7% of evaluations) without sacrificing prediction reliability. However, consistently low uncertainty from the start raises important considerations regarding potential optimization bias. When the surrogate maintains high confidence early in the search, there is a risk of premature convergence through: (1) over-exploitation of known regions, where the optimizer preferentially samples areas of existing confidence rather than exploring uncertain regions; (2) false confidence, where low uncertainty does not guarantee accuracy—the model may be confidently incorrect in unexplored areas, leading to locally optimal but globally suboptimal Pareto fronts; (3) reduced diversity, as minimal SPICE verification (10% at minimum allocation) provides limited opportunity to detect missing design space features; and (4) initial training bias, where DOE samples concentrated in specific regions produce surrogates that are well-trained locally but ignorant yet falsely confident in undersampled areas.

Figure 17.

Evolution of the batch uncertainty during multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively): (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Figure 17.

Evolution of the batch uncertainty during multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) for the different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test (NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2, respectively): (a-c) Miller-compensated differential amplifier; (d-f) Transistor-compensated differential amplifier; (g-i) folded-cascode op-amp; (l-n) Telescopic-cascode amplifier.

Empirical analysis across our runs revealed a robust correlation between uncertainty evolution and Pareto quality: runs achieving the best Pareto fronts consistently exhibited monotonically increasing UncMean and UncP95, indicating sustained exploration into previously unseen regions of the design space as superior trade-offs were discovered. Conversely, runs with stationary or monotonically decreasing uncertainty tended to stagnate and produced inferior fronts, consistent with premature convergence and over-exploitation of already-confident regions.

Importantly, this pattern held across multiple MOEAs—including NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and SPEA2—suggesting it is not tied to a specific algorithmic detail but rather to a general exploration–exploitation dynamic. As the search moves toward novel objective combinations and parameter regimes, the surrogate naturally encounters unfamiliar inputs, which increases predictive uncertainty; in this context, rising uncertainty is a healthy signal of active exploration rather than model degradation.

These dynamics are supported by the framework’s diversity-preserving mechanisms (e.g., niching and reference-point guidance in NSGA variants, strength-based selection in SPEA2), the composite scoring used for fidelity allocation (which blends uncertainty with exploitation/diversity cues), the hypervolume-proxy option that explicitly rewards frontier expansion, and continuous retraining from SPICE-verified samples. Together, these elements mitigate exploitation bias while enabling the surrogate to remain the dominant evaluator without sacrificing discovery.

The aggregated MAE convergence data in

Table 7 confirm that the surrogate models consistently improve their predictive accuracy throughout the optimization process. The mean relative improvement ranges between approximately 40% and 65%, depending on the circuit topology, with the folded-cascode and Miller-compensated amplifiers showing the strongest refinement. Conversely, the transistor-compensated differential amplifier and the telescopic-cascode amplifier remain the most challenging cases, exhibiting smaller MAE reductions and higher final residual errors. These results are consistent with their more irregular Pareto fronts and the stronger parameter coupling expected in these topologies, which complicate accurate surrogate interpolation.

When these MAE dynamics are cross-referenced with the uncertainty-evolution trends, a consistent pattern emerges. Runs achieving the best Pareto fronts are not necessarily those with the lowest final MAE, but rather those exhibiting increasing uncertainty throughout the optimization trajectory. This correlation indicates that uncertainty growth serves as an indicator of active exploration, as the optimizer encounters novel regions of the design space where the surrogate confidence is lower.

In contrast, runs with flat or decreasing uncertainty curves—particularly those associated with limited MAE improvement—tend to converge in suboptimal regions, leading to poorer trade-offs. Thus, while decreasing MAE confirms the surrogate’s improving reliability, maintaining a moderate level of predictive uncertainty is essential to preserve exploration pressure and prevent the optimizer from over-exploiting already well-characterized regions.

Figure 18 reports the average wall-clock time per generation for both sequential and parallel multi-fidelity optimization (MFO) runs for all the amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms under test. The per-generation timing profiles presented in

Figure 18 provide a qualitative view of the temporal evolution of the optimization process and highlight the impact of parallel execution on runtime stability.

To complement these observations with quantitative data,

Table 8 summarizes the corresponding average wall-clock times and parallel execution metrics for all amplifier topologies and algorithms. This table consolidates the results across both sequential and parallel configurations, allowing a direct assessment of overall speedups, efficiency, and time reduction achieved by the multi-fidelity optimization framework under identical solver and uncertainty-control settings.

The wall-clock time evolution per generation across all multi-fidelity optimization runs reveals distinct performance profiles for different amplifier topologies and genetic algorithms. On average, sequential execution exhibits generation times ranging from 0.7 to 1.3 seconds per generation, with folded cascode showing the shortest execution times (0.8 s/gen) and transistor-compensated differential amplifier requiring the longest (1.3 s/gen). Parallel execution with multiple workers yields substantial performance improvements, achieving an average speedup of 2.54× and reducing total wall-clock time by approximately 60.2% on average. The parallel efficiency averages 31.7%, indicating limited scaling behavior. The deviation from ideal linear speedup can be attributed to synchronization overhead in batch-based SPICE evaluations and the inherent sequential dependencies in adaptive surrogate model updates.