Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

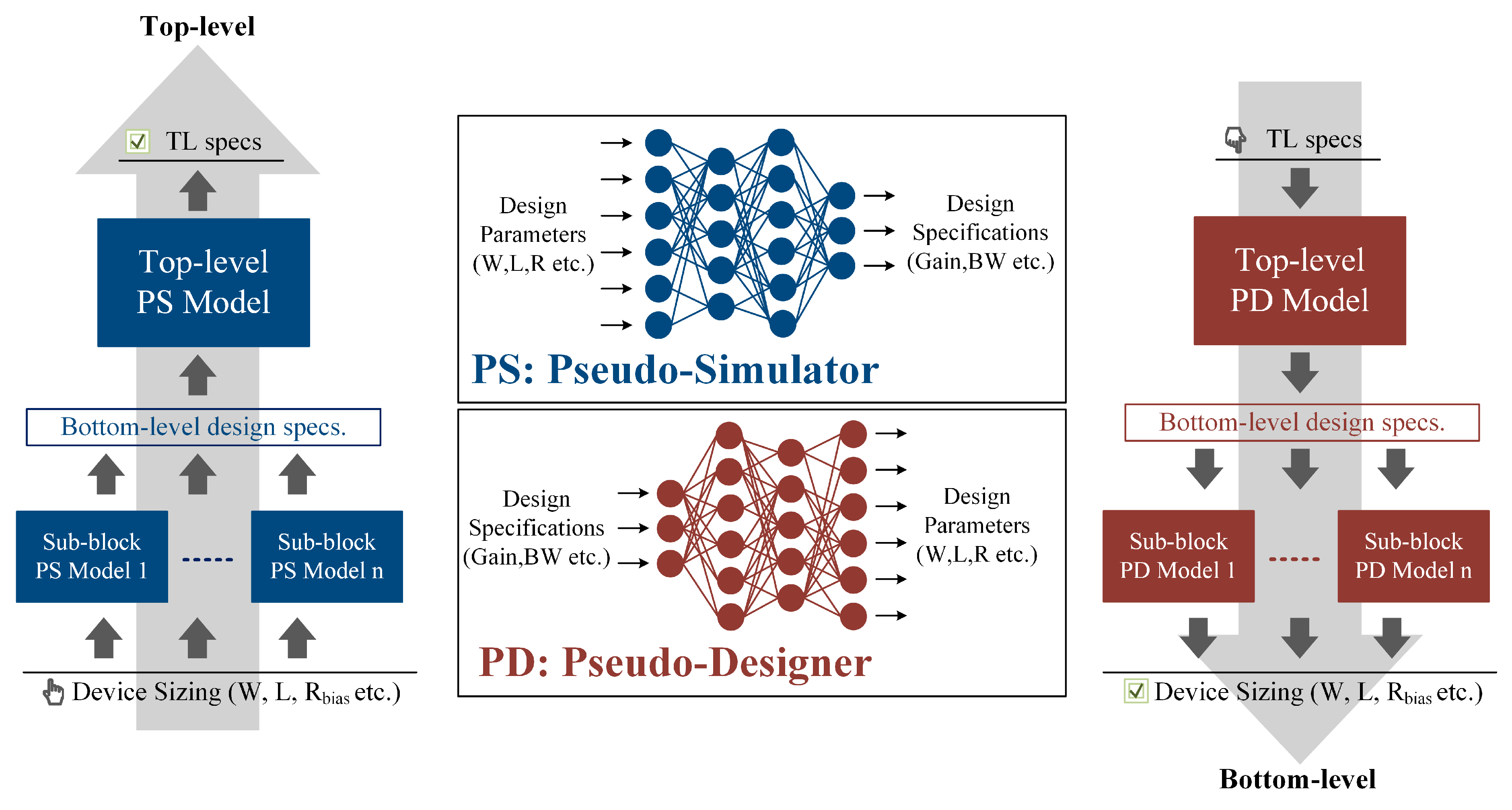

- In addition to system-level modeling, sub-blocks were modeled individually, enabling rapid mapping between circuit parameters and top-level specifications.

- All circuits were modeled bidirectionally (from design parameters to specifications and vice versa), regardless of their position in the hierarchy, thereby facilitating the exploration of new regions in the solution space with minimal effort.

- To the best of our knowledge, the proposed method is the first simulation-free solution once the framework has been constructed.

- Once all the models are available, the time-to-design takes less than one second.

- Under changing design conditions, sub-block circuits can be re-optimized within a short time using the trained models, enhancing design flexibility at the system level.

- The proposed methodology was validated on two diverse and complicated circuits: 8-Bit ADC and RF receiver.

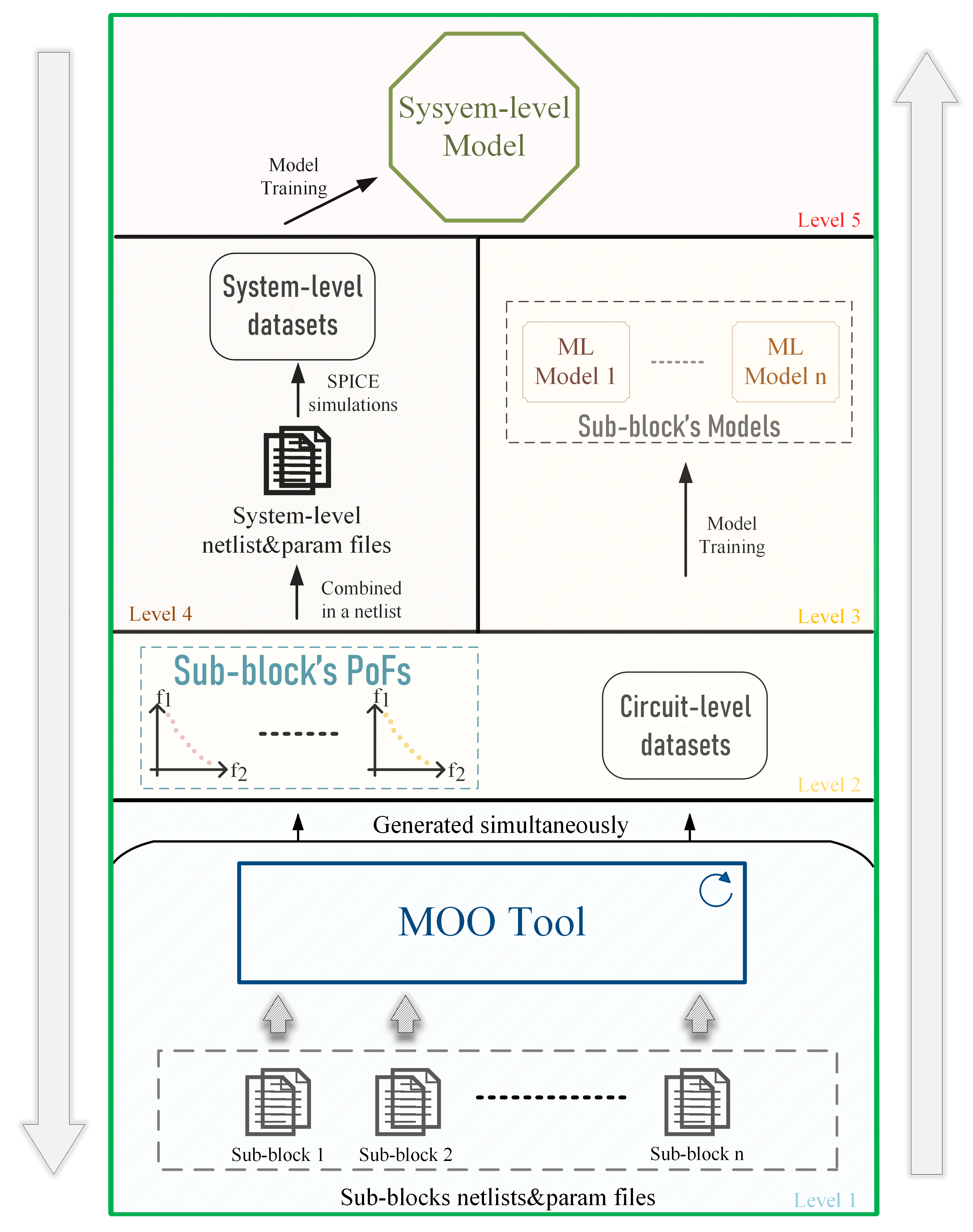

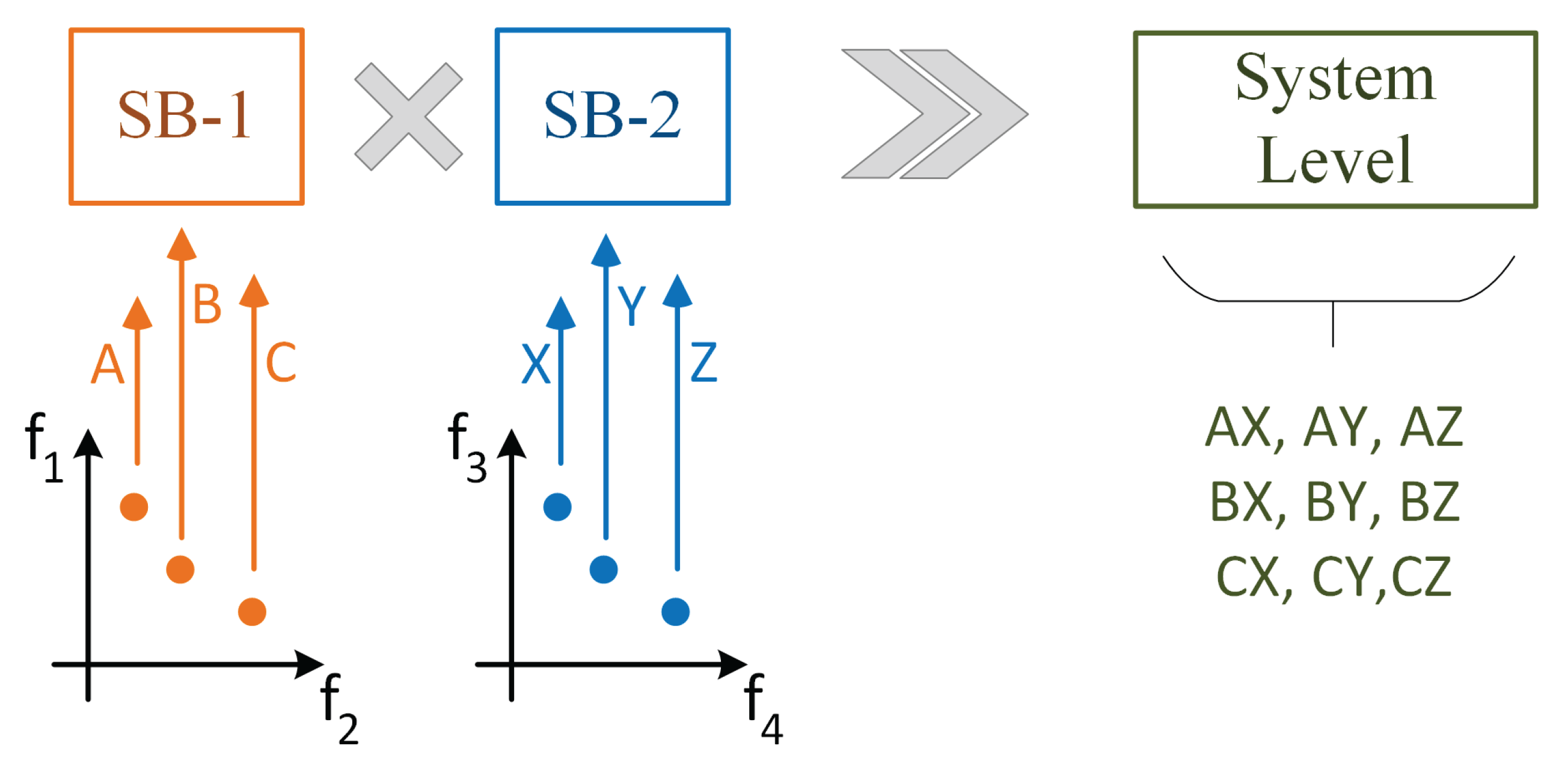

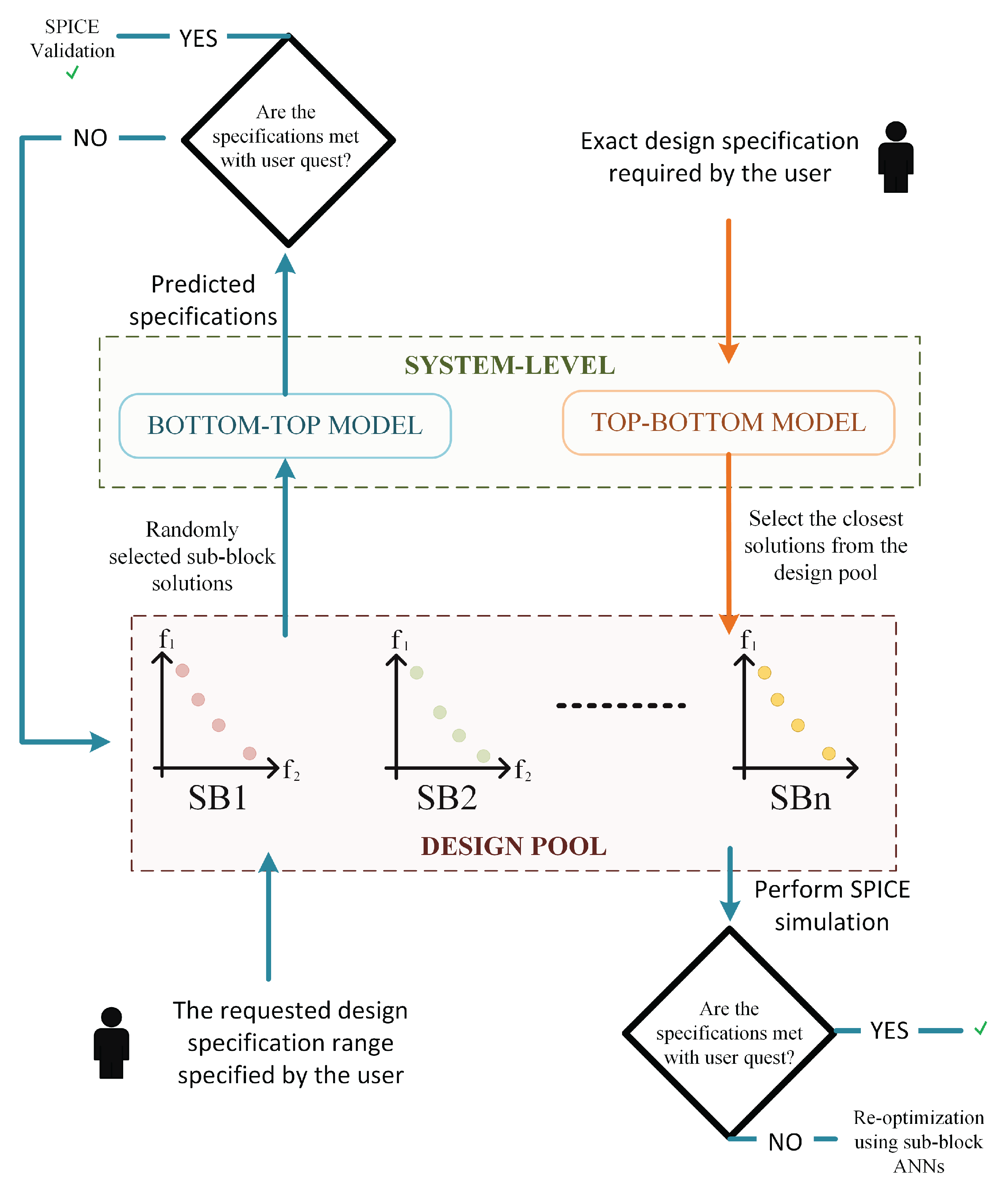

2. Hierarchical Automation through ANN-Based Reusable Sub-Block Modeling

2.1. Approach Overview

2.2. Circuit Sizing

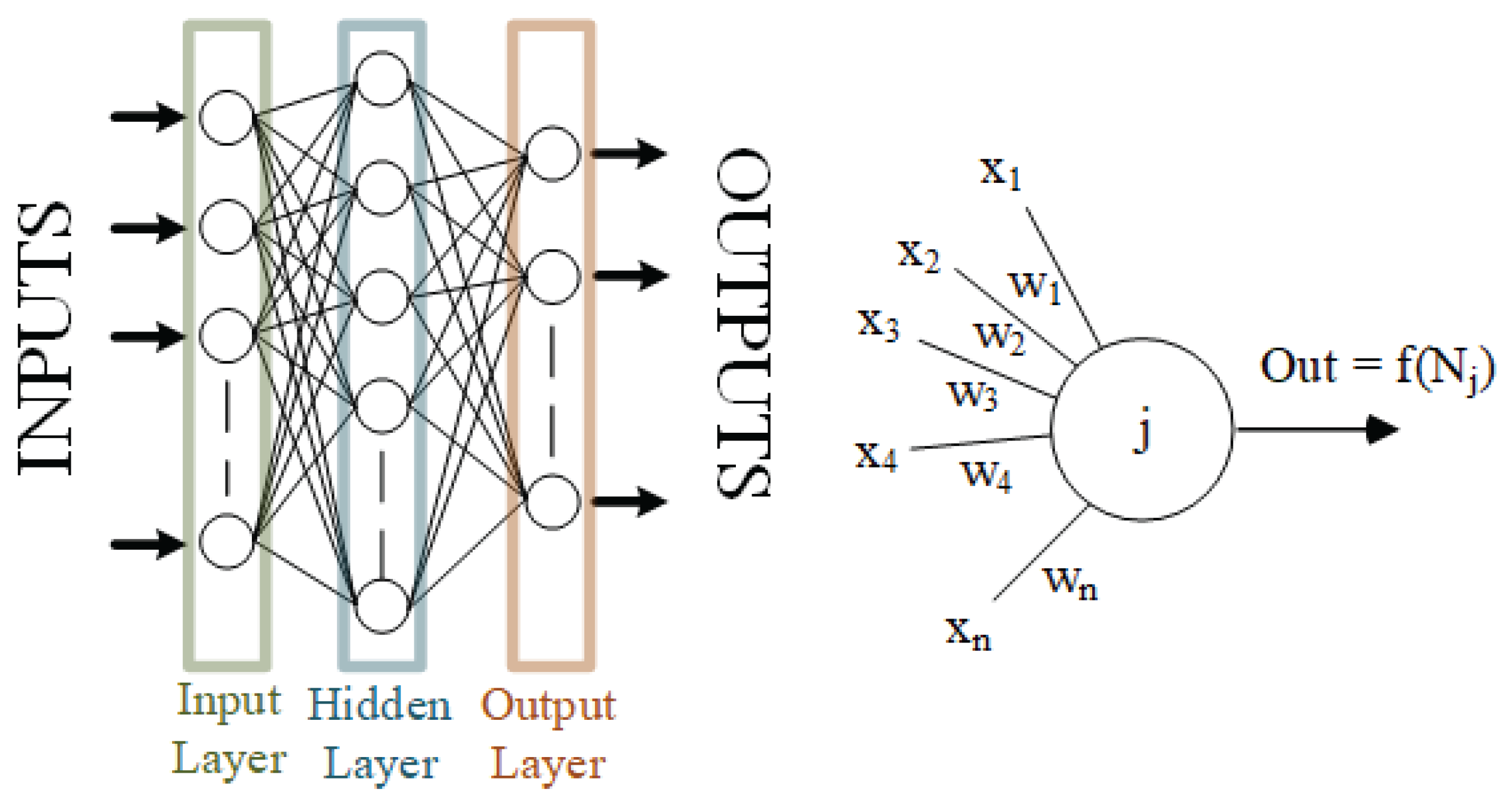

2.3. ANN Modeling

2.4. System-Level Synthesis

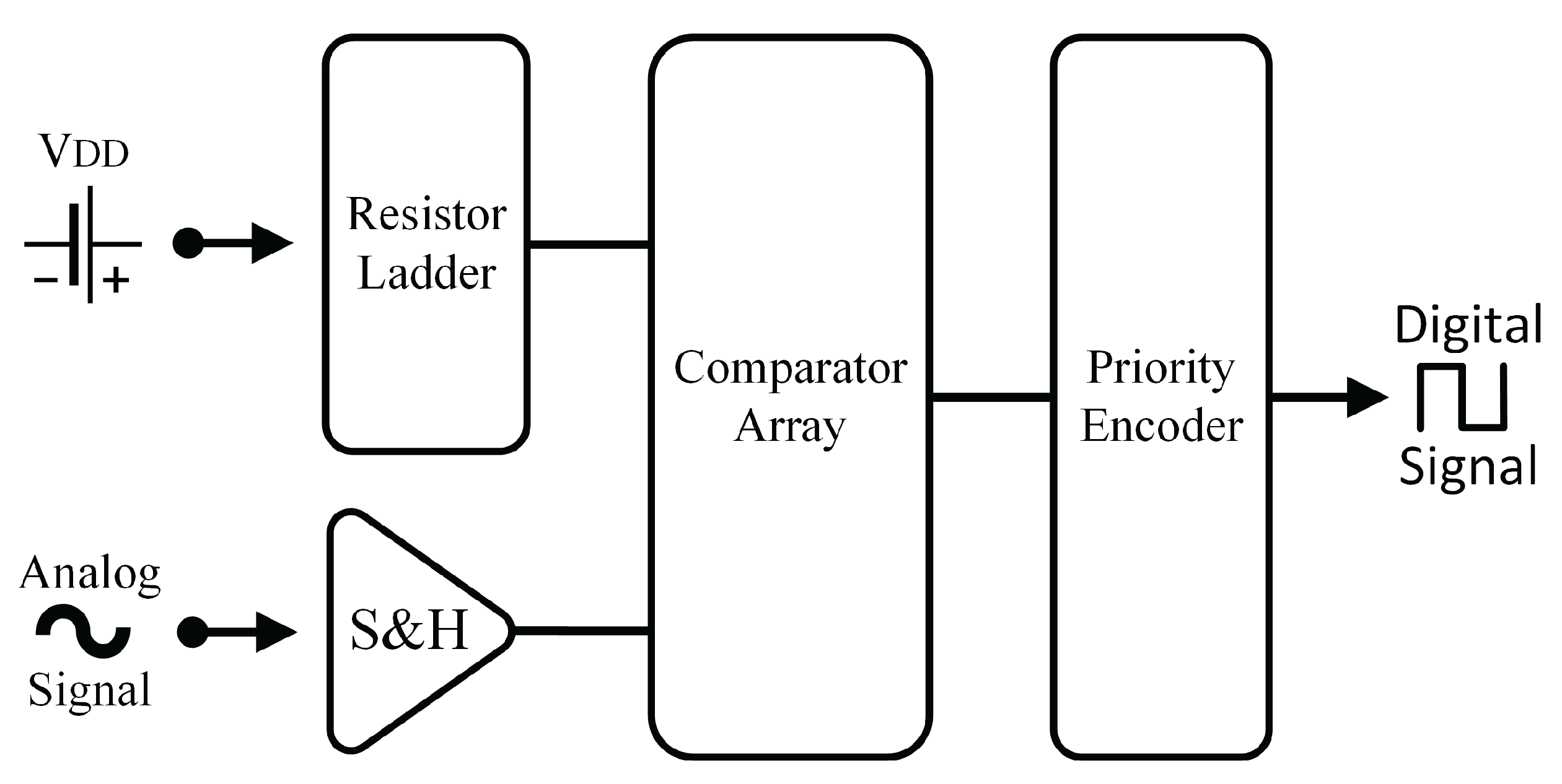

3. Case Study - I: Hierarchical Modeling of Flash ADC

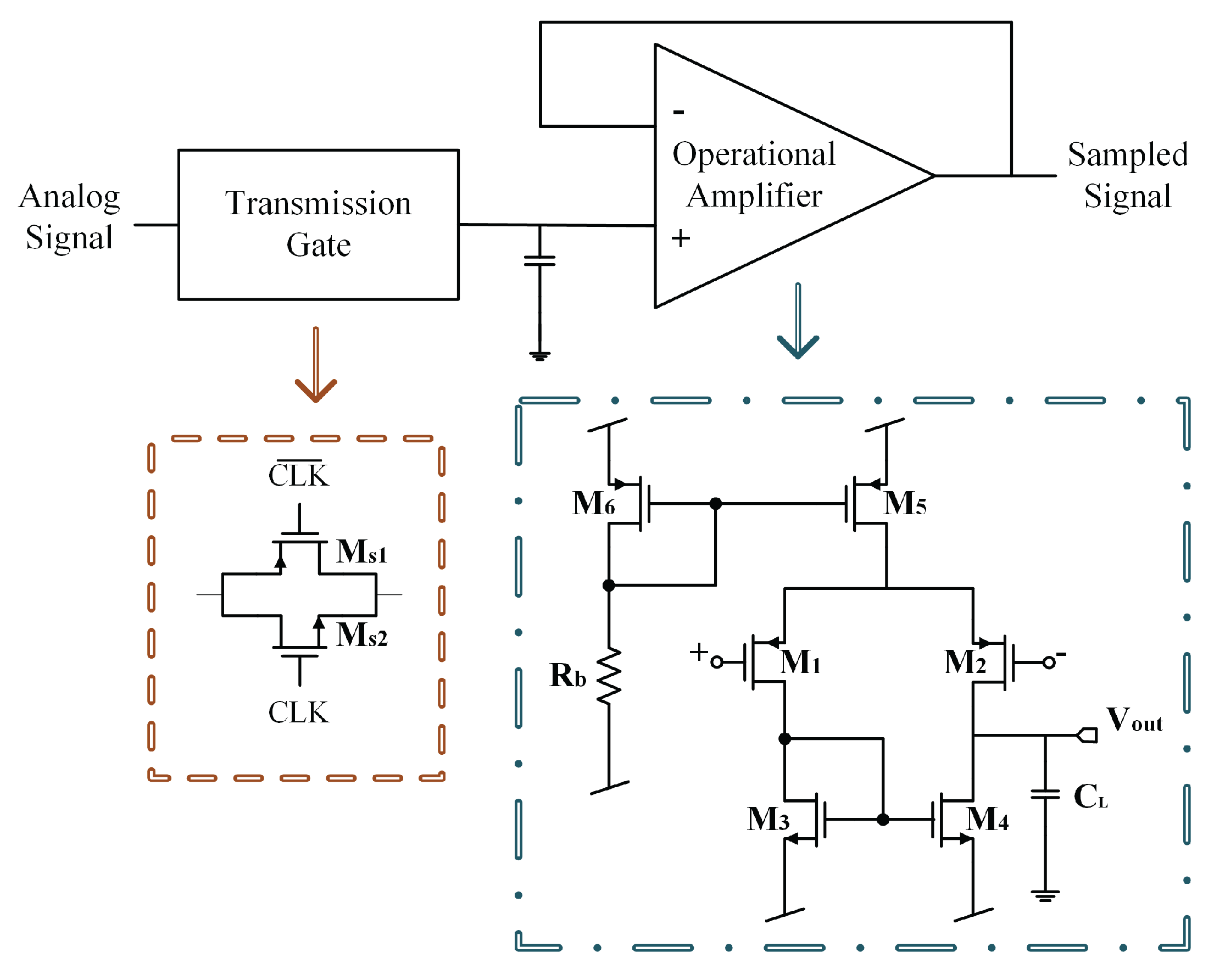

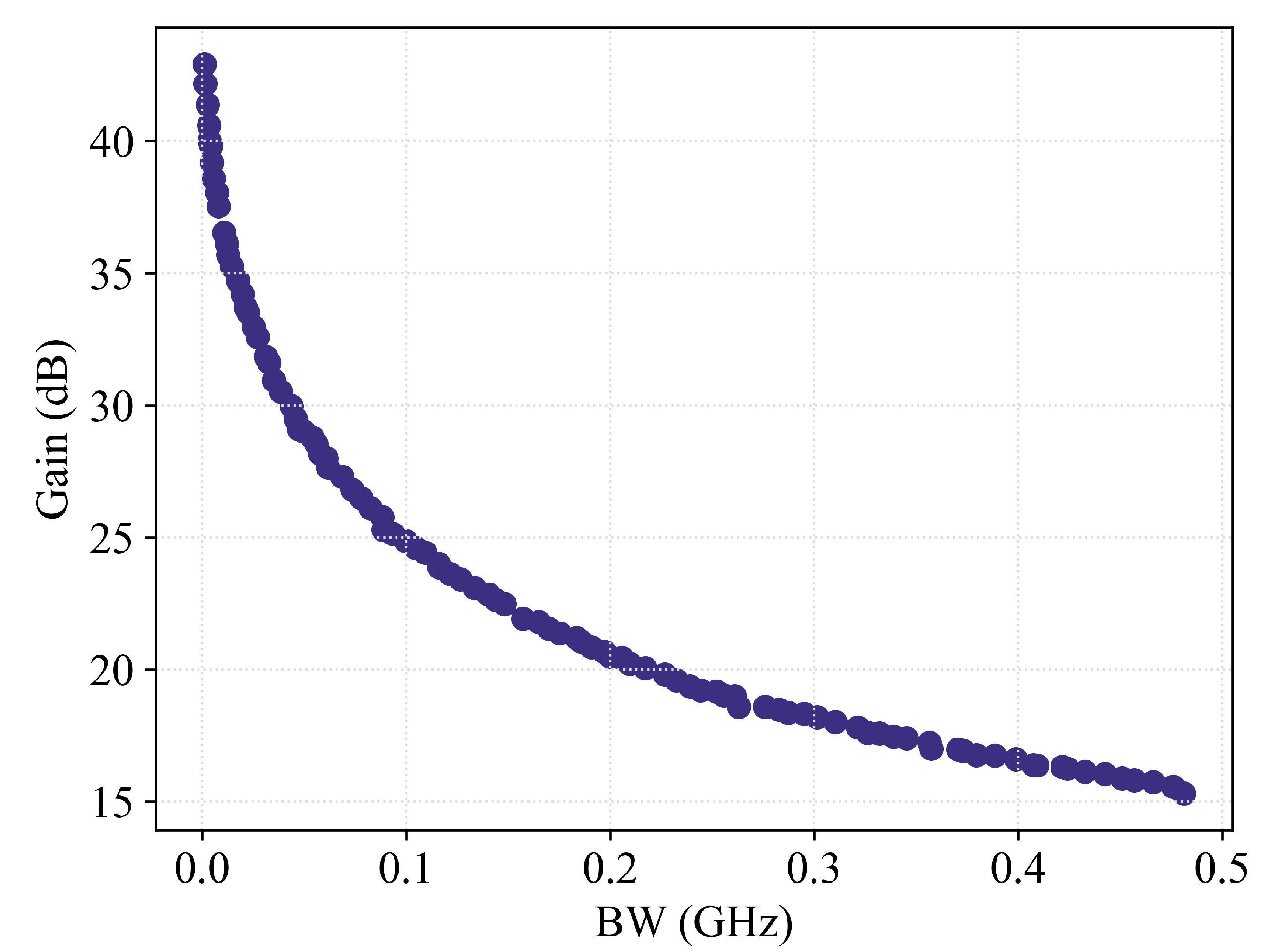

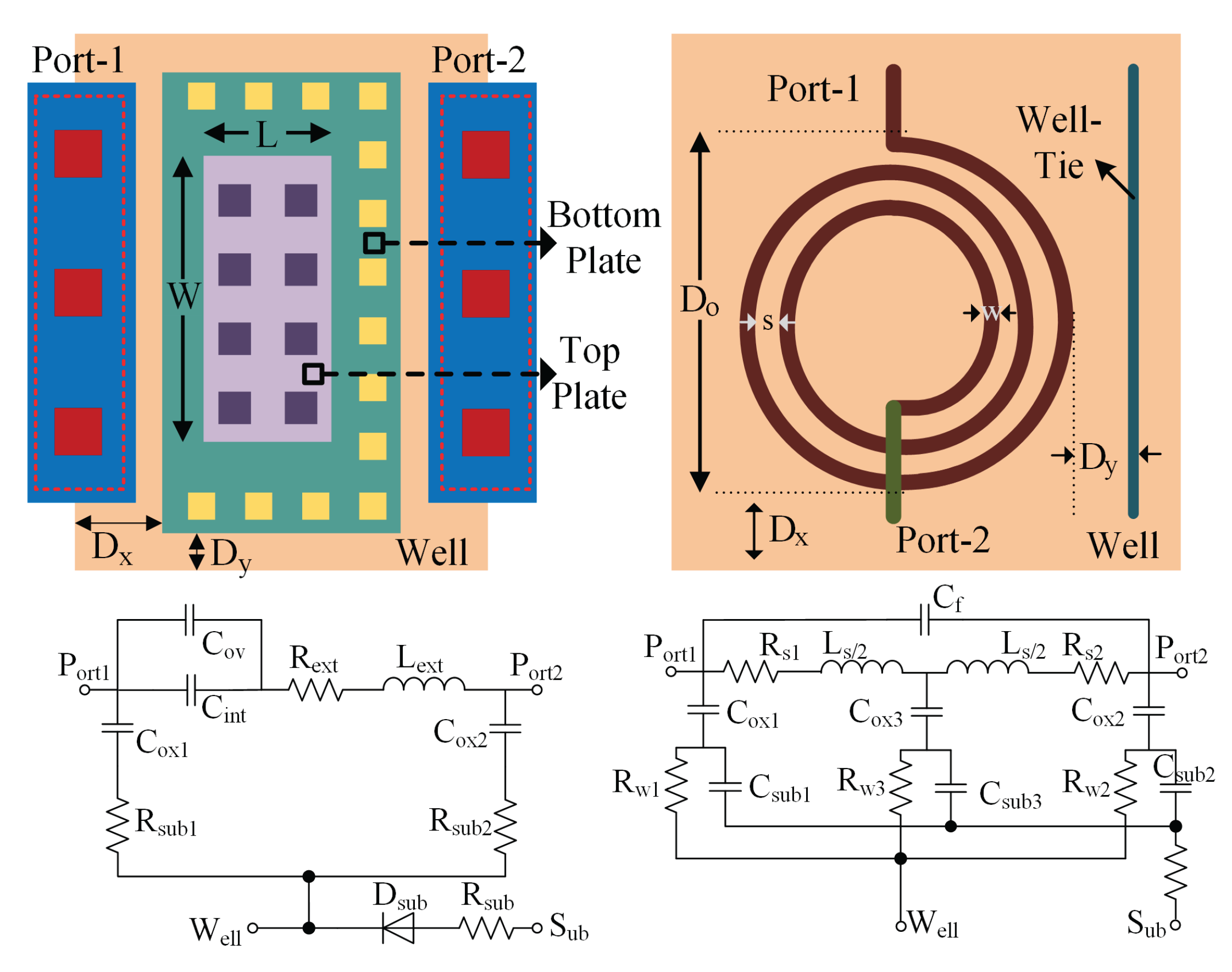

3.1. S&H Block: Differential Amplifier Modeling

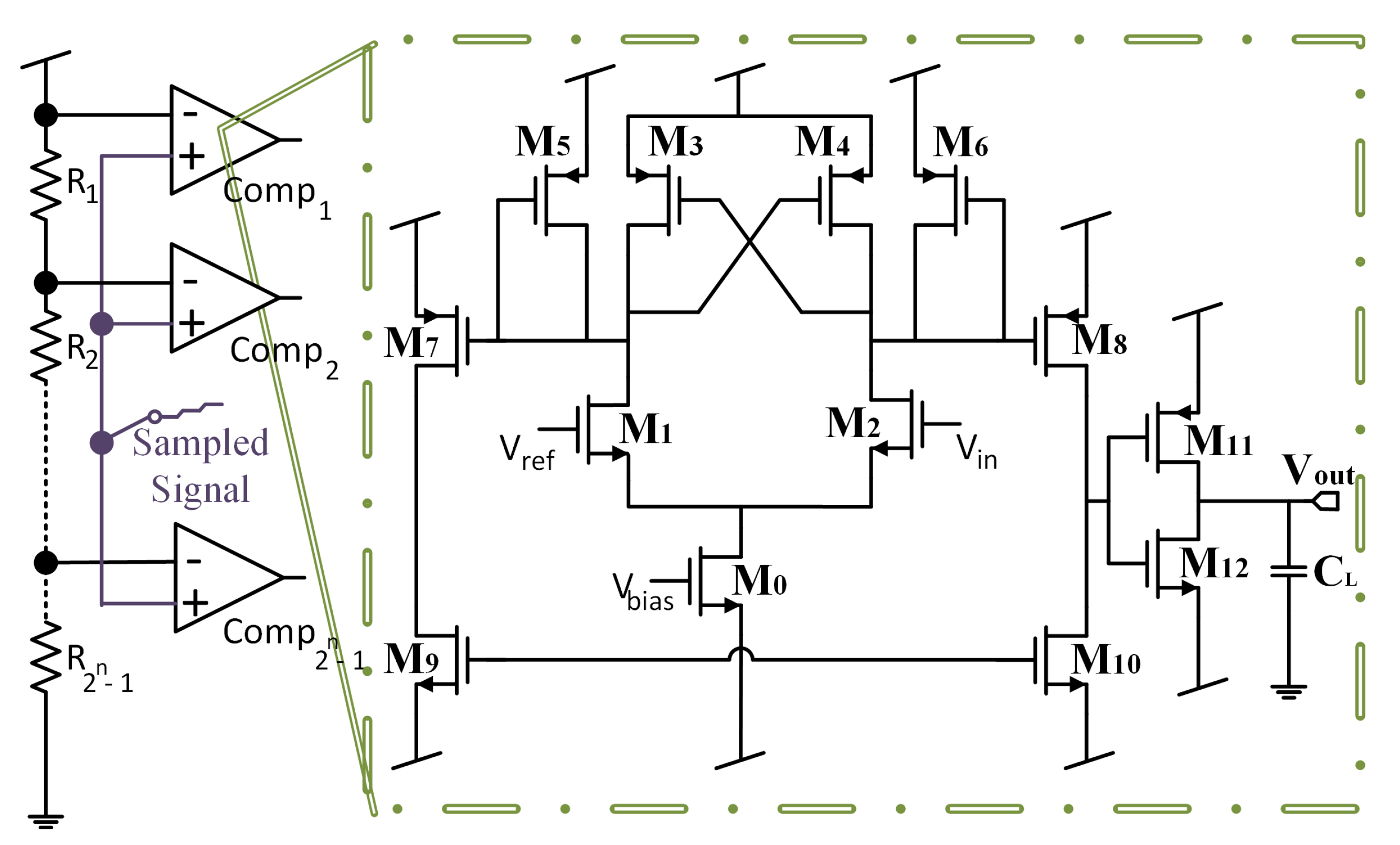

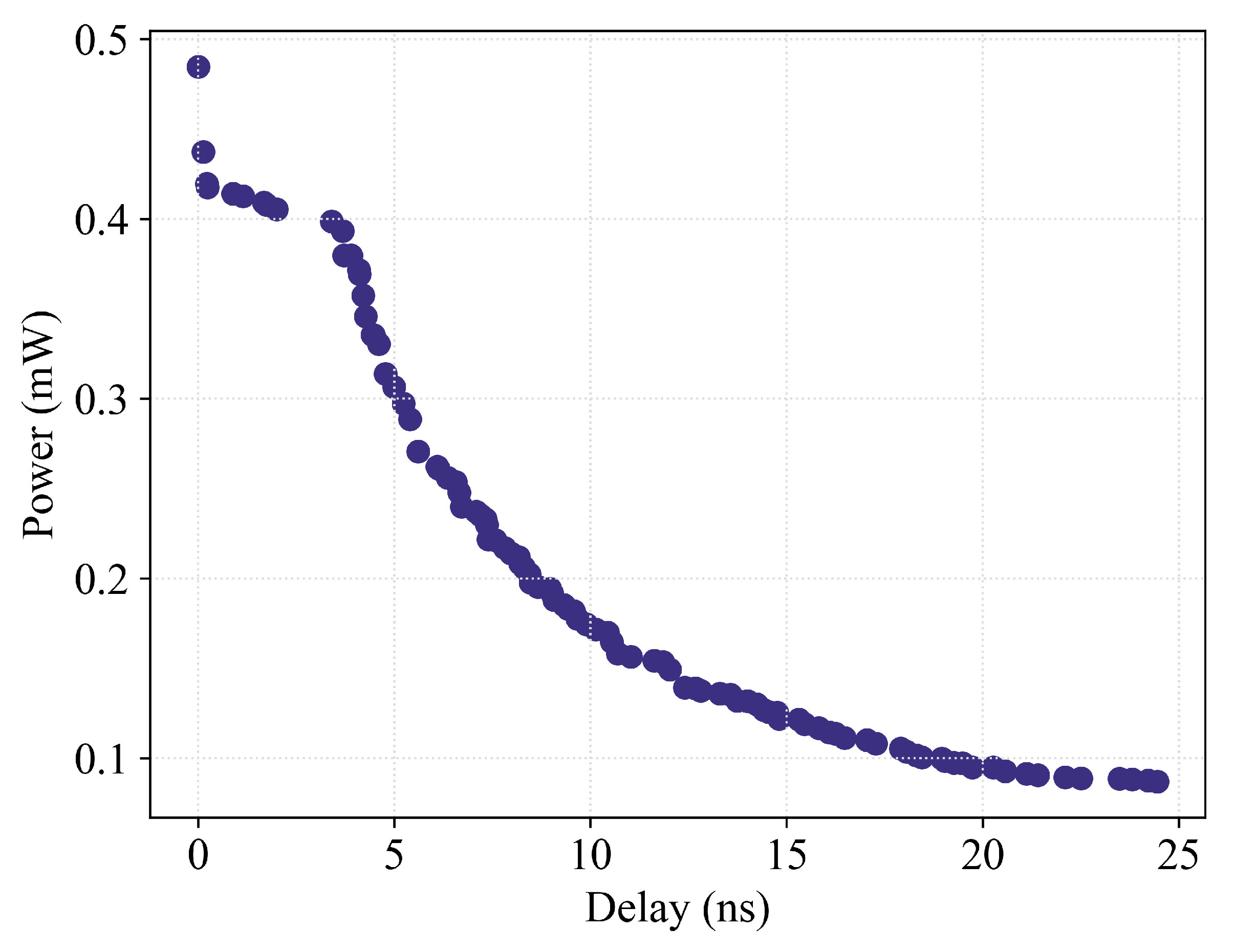

3.2. Resistor&Comparator Array: Comparator Modeling

3.3. Priority Encoder: Verilog-AMS Modeling

3.4. 8-Bit ADC: System Level Modeling

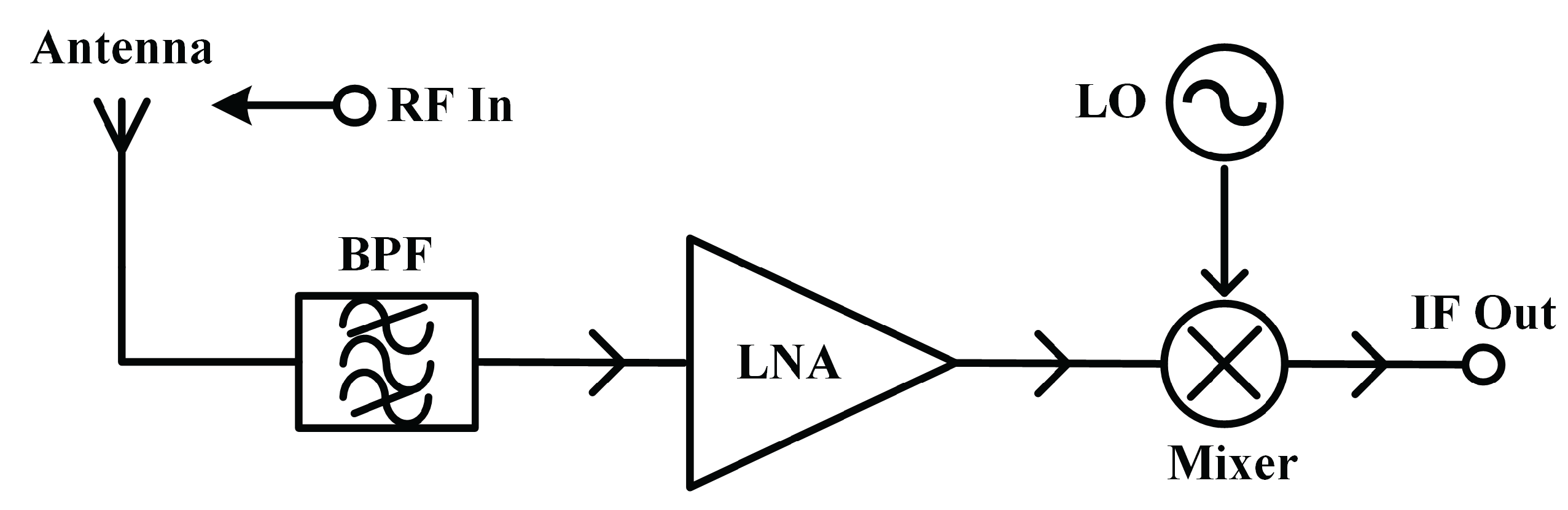

4. Case Study - II: Hierarchical Modeling of Generic Heterodyne Receiver

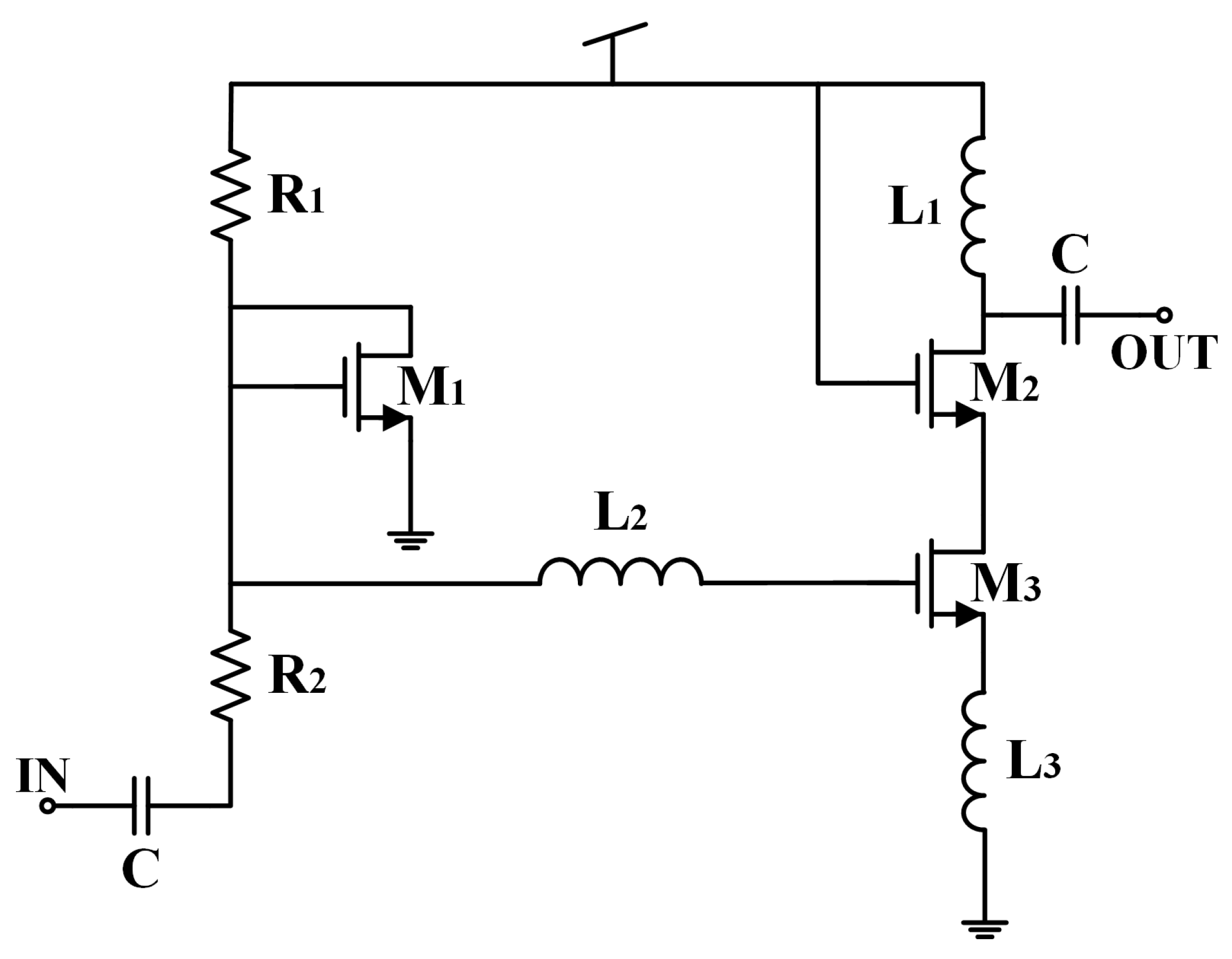

4.1. Low Noise Amplifier

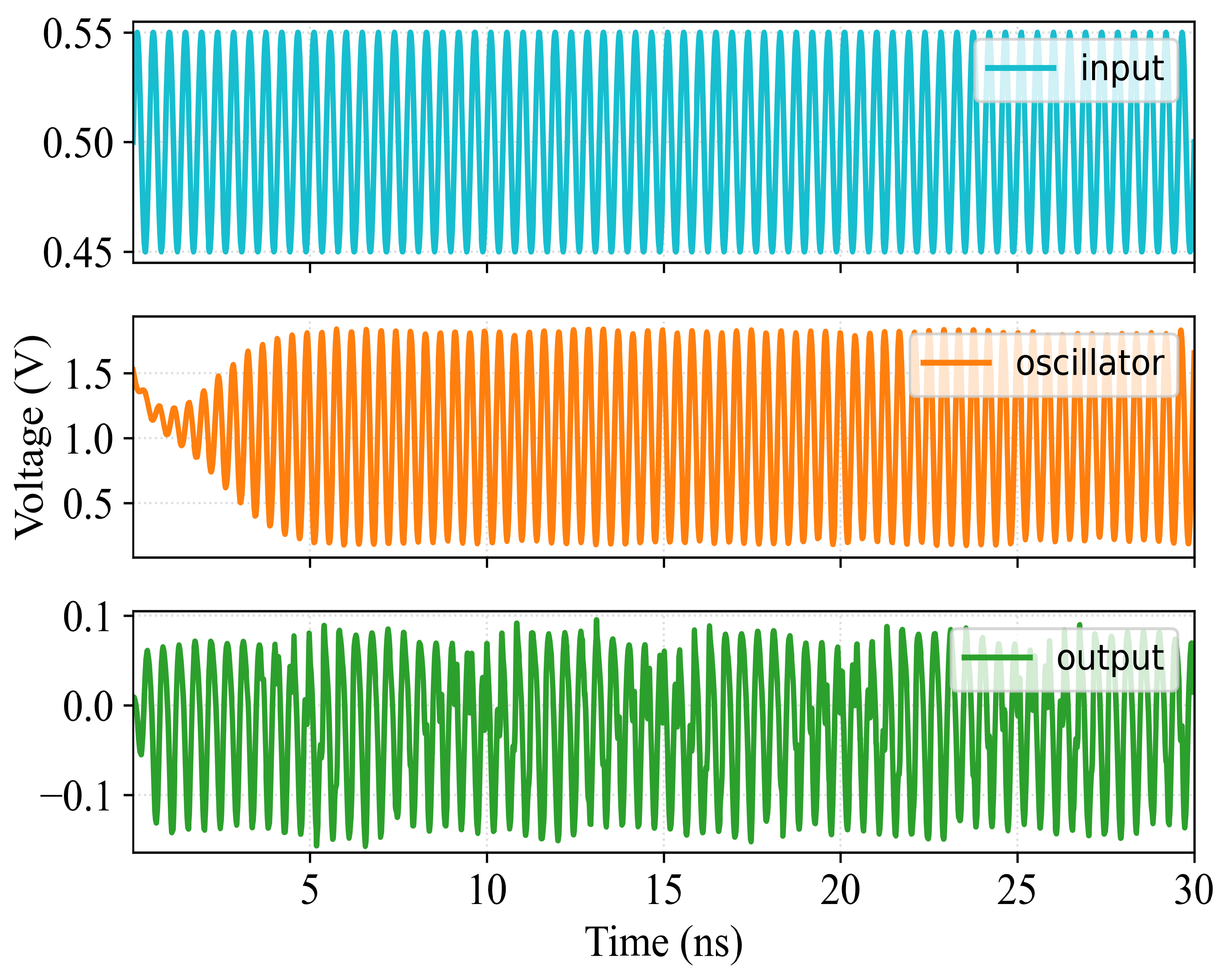

4.2. Oscillator

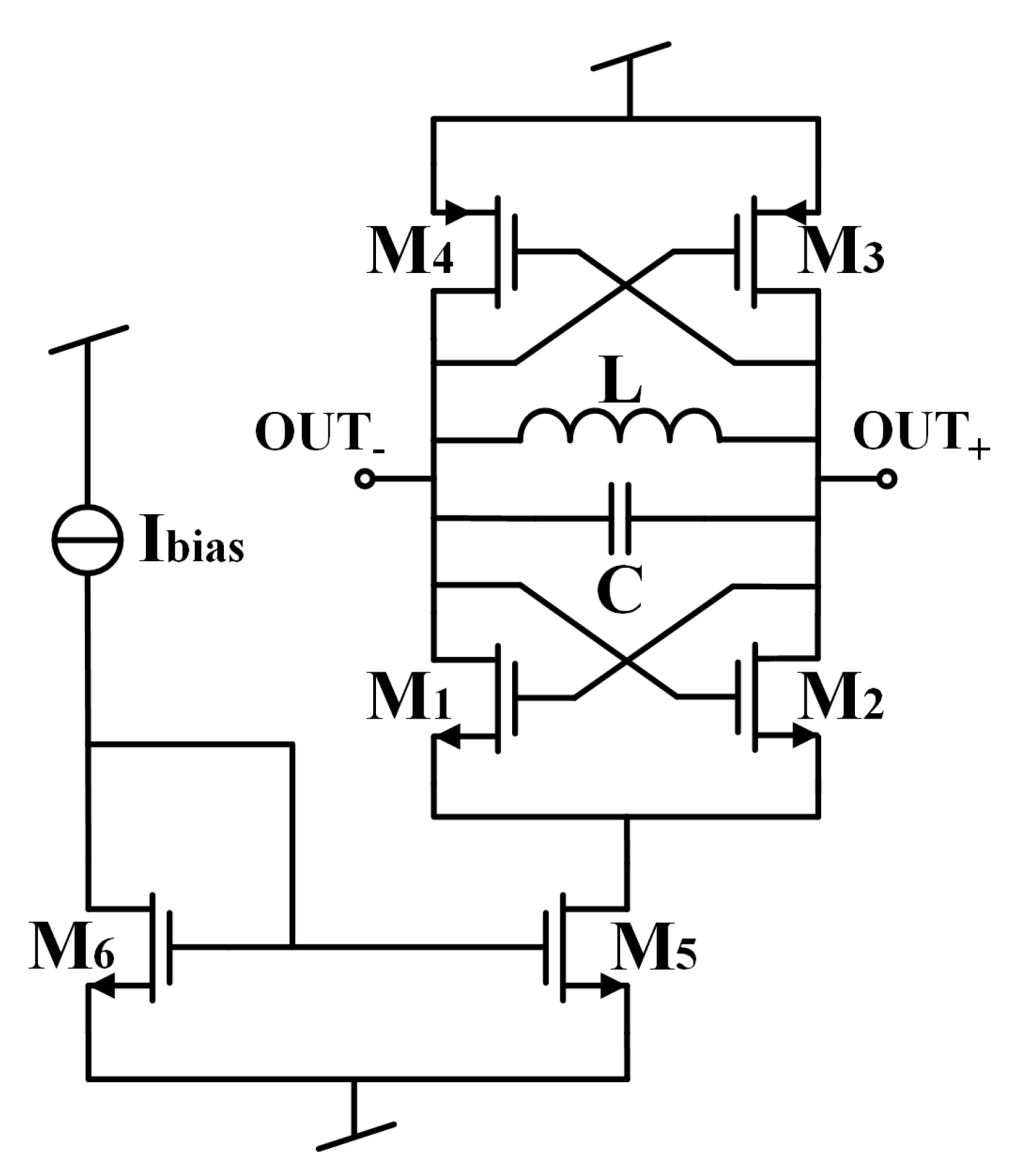

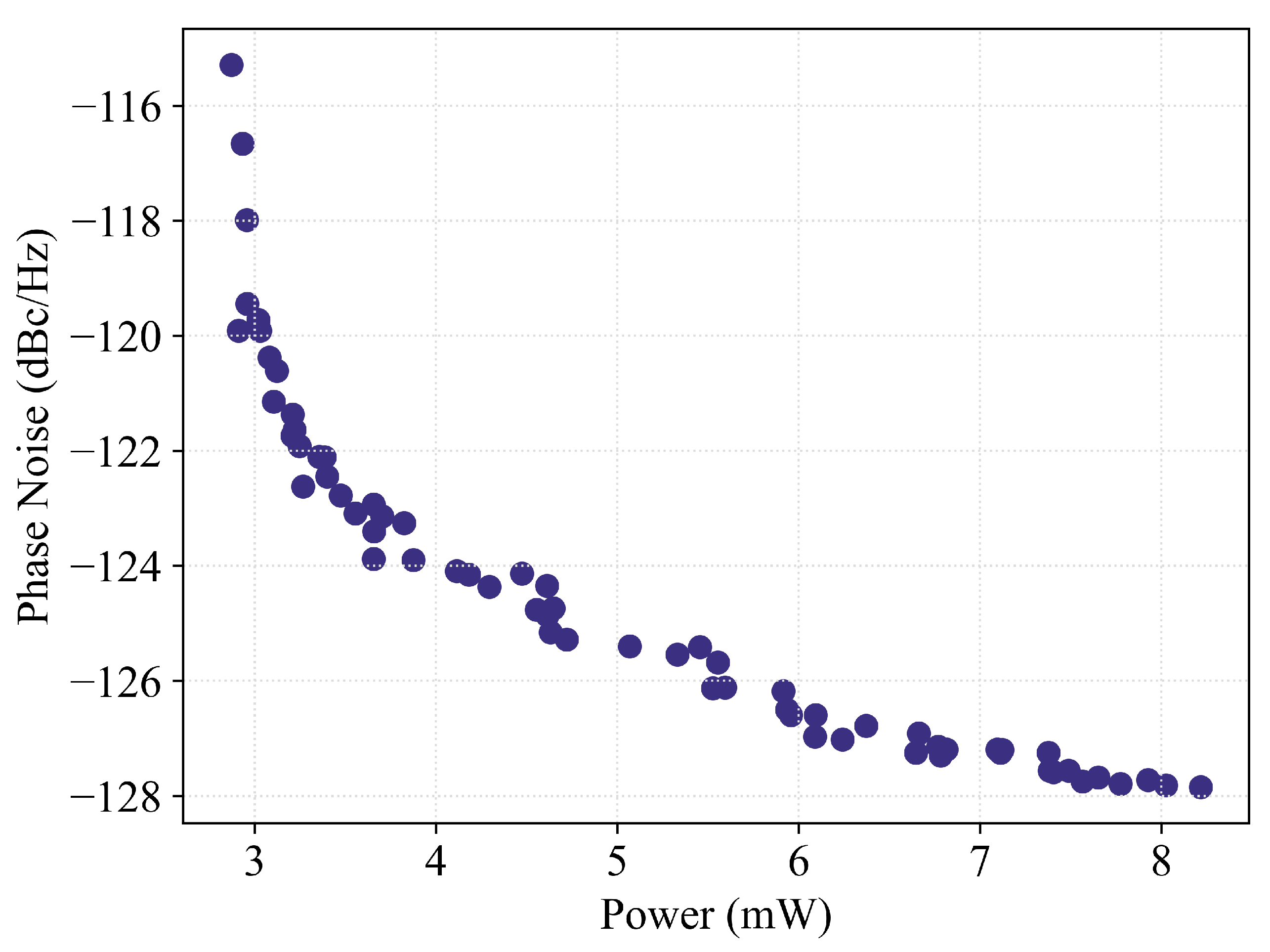

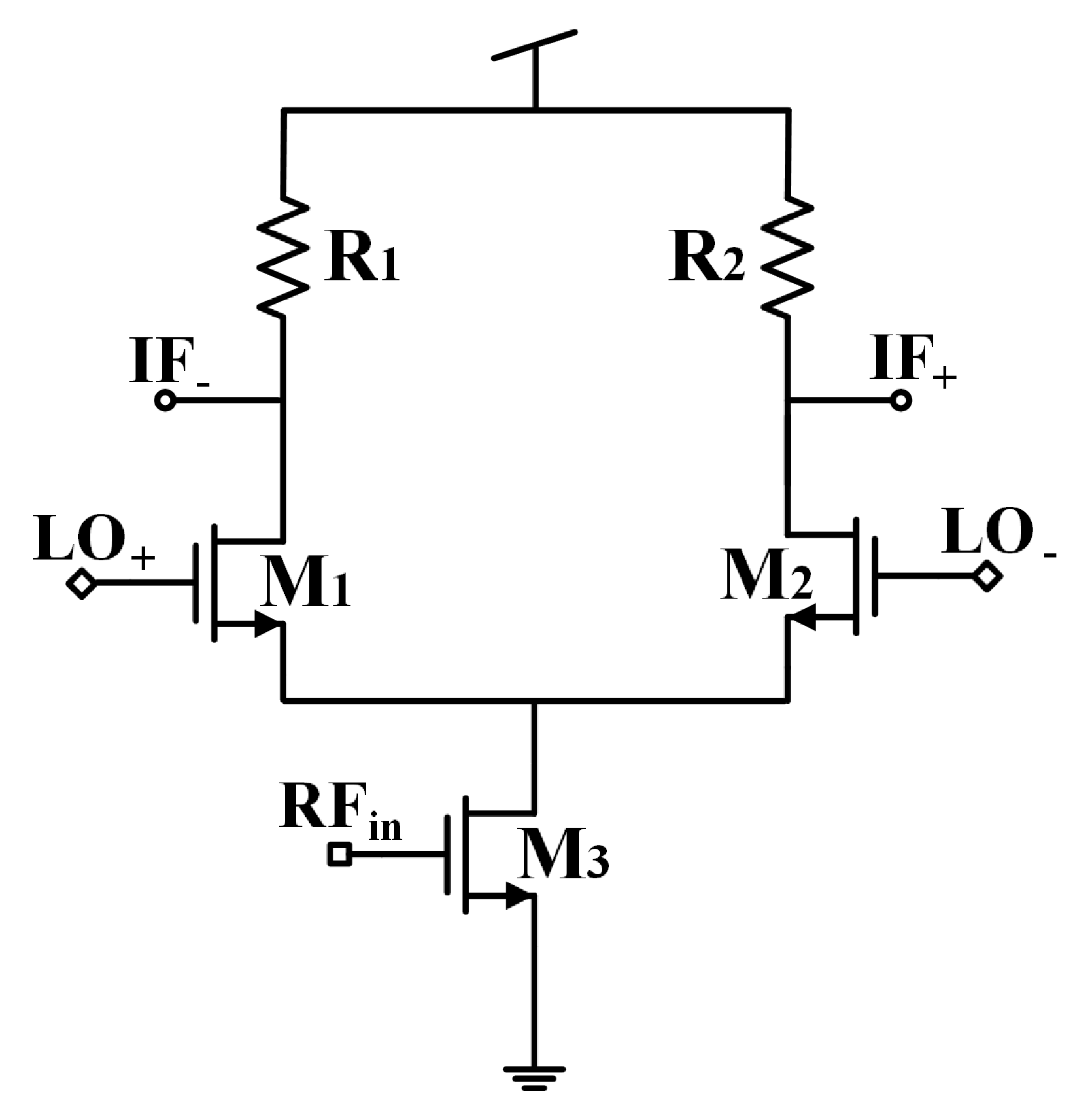

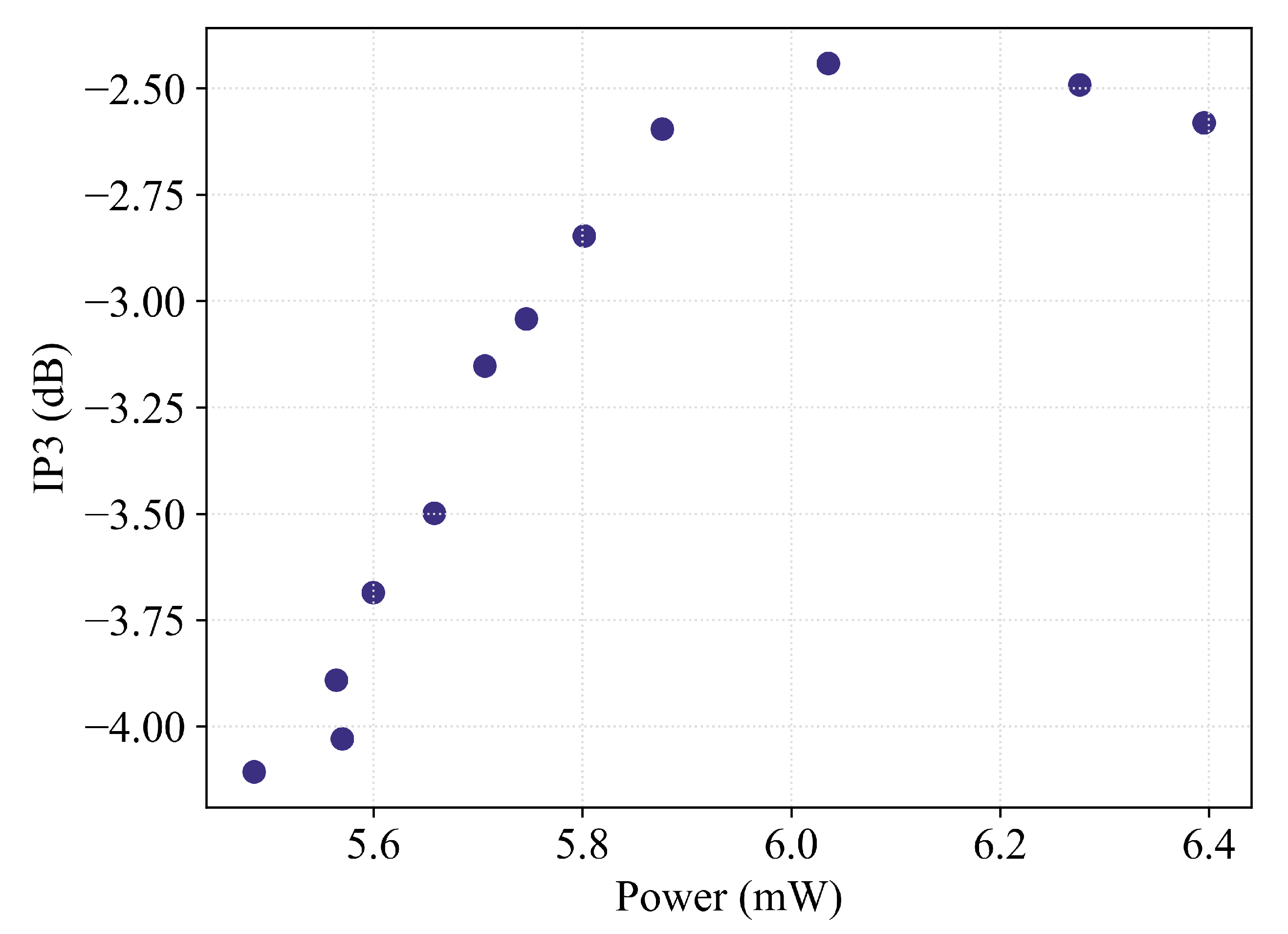

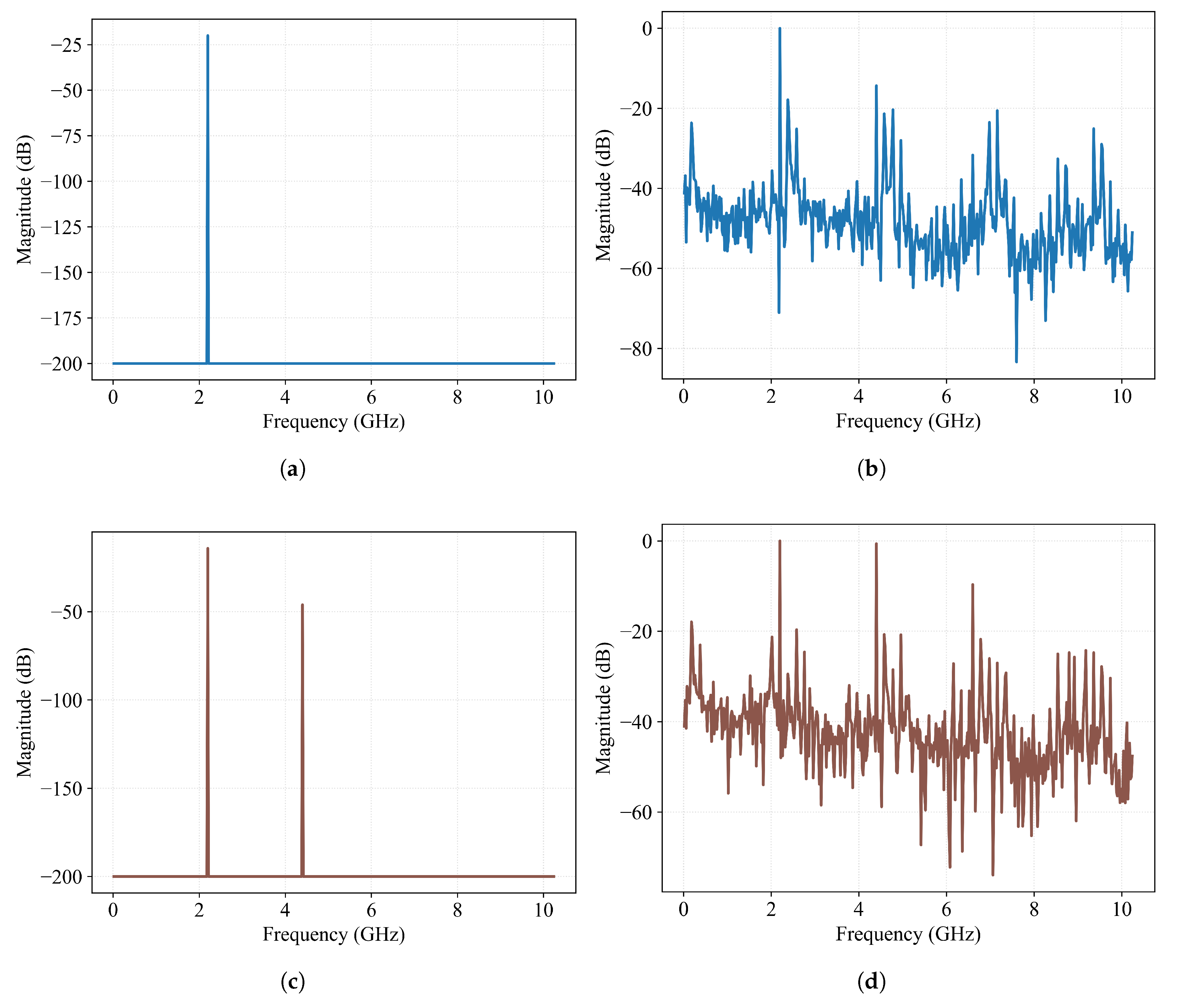

4.3. Mixer

4.4. Heterodyne Receiver: System Level Modeling

5. Experimental Results: Hierarchical Syntheses

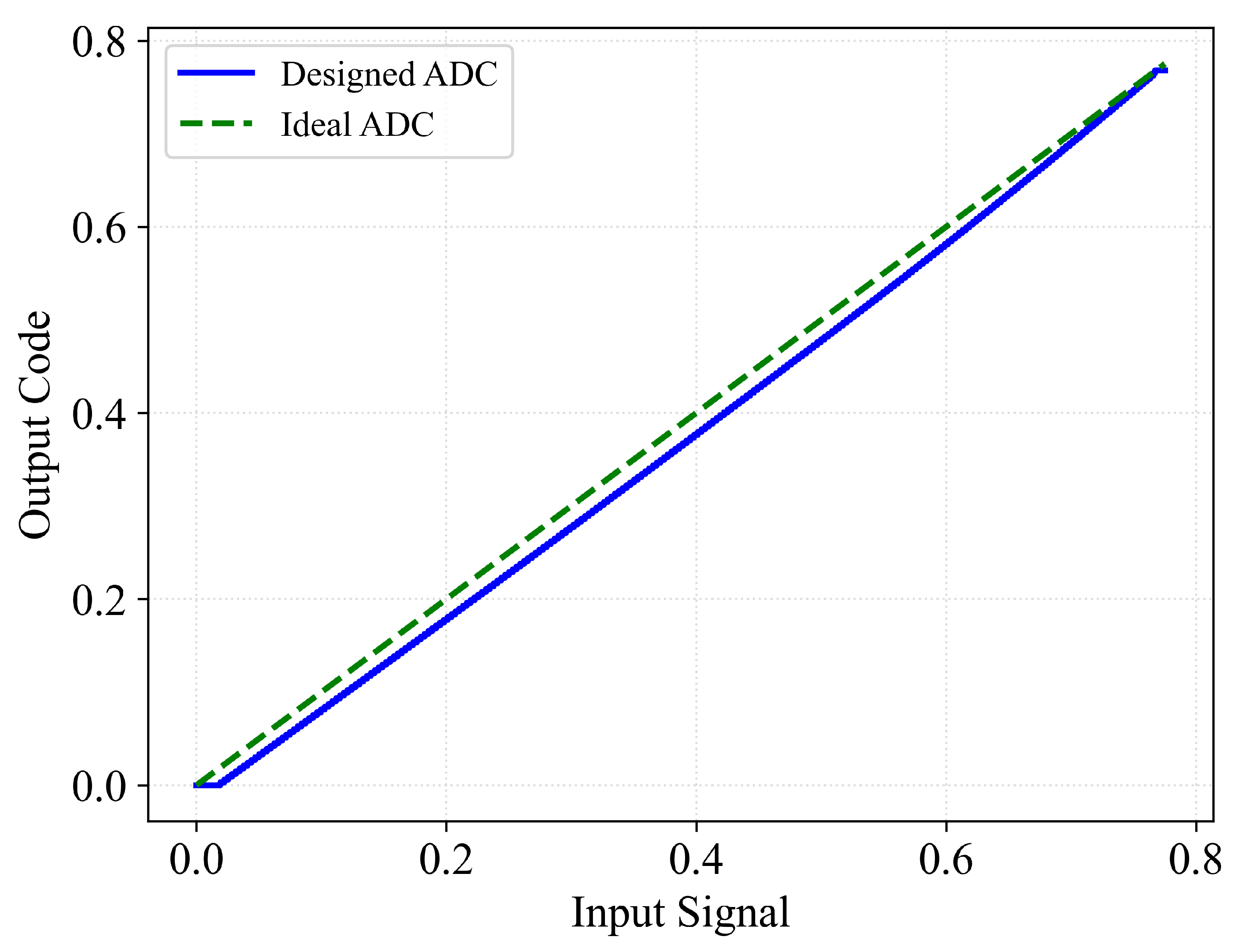

5.1. Hierarchical Synthesis of 8-Bit Flash ADC

5.2. Hierarchical Synthesis of Heterodyne Receiver

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harjani, R.; Rutenbar, R.A.; Carley, L.R. OASYS: A framework for analog circuit synthesis. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 1989, 8, 1247–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, C.A.; Toumazou, C. Analog IC design automation. II. Automated circuit correction by qualitative reasoning. IEEE transactions on computer-aided design of integrated circuits and systems 1995, 14, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.Y.; Sequin, C.H.; Gray, P.R. OPASYN: A compiler for CMOS operational amplifiers. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 1990, 9, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Hershenson, M.; Boyd, S.P.; Lee, T.H. GPCAD: A tool for CMOS op-amp synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE/ACM international conference on Computer-aided design, 1998, pp. 296–303.

- Kruiskamp, W.; Leenaerts, D. DARWIN: CMOS opamp synthesis by means of a genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd annual ACM/IEEE design automation conference, 1995, pp. 433–438.

- Paulino, N.; Goes, J.; Steiger-Garção, A. Design methodology for optimization of analog building blocks using genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the ISCAS 2001. The 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (Cat. No. 01CH37196). IEEE. Vol. 5, 2001; 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: an introductory analysis with applications to biology, control, and artificial intelligence; MIT press, 1992.

- Gielen, G.G.; Walscharts, H.C.; Sansen, W.M. Analog circuit design optimization based on symbolic simulation and simulated annealing. IEEE Journal of solid-state circuits 1990, 25, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt Jr, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nye, W.; Riley, D.C.; Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A.; Tits, A.L. DELIGHT. SPICE: An optimization-based system for the design of integrated circuits. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 1988, 7, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, A.; Chavez, J.; Franquelo, L.G. FASY: A fuzzy-logic based tool for analog synthesis. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 1996, 15, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnicki, M.; Phelps, R.; Rutenbar, R.A.; Carley, L.R. MAELSTROM: Efficient simulation-based synthesis for custom analog cells. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th annual ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 1999, pp. 945–950.

- Silva, J.; Horta, N. Genom: circuit-level optimizer based on a modified Genetic Algorithm kernel. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems. Proceedings (Cat. No. 02CH37353). IEEE, 2002, Vol. 1, pp. I–I.

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaghy, T.; Palmers, P.; Gielen, G.; Steyaert, M. Simultaneous multi-topology multi-objective sizing across thousands of analog circuit topologies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th annual Design Automation Conference, 2007, pp. 944–947.

- Pradhan, A.; Vemuri, R. Efficient synthesis of a uniformly spread layout aware pareto surface for analog circuits. In Proceedings of the 2009 22nd International Conference on VLSI Design. IEEE, 2009, pp. 131–136.

- Lourenço, N.; Horta, N. GENOM-POF: multi-objective evolutionary synthesis of analog ICs with corners validation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, 2012, pp. 1119–1126.

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks. ieee, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948.

- Fakhfakh, M.; Cooren, Y.; Sallem, A.; Loulou, M.; Siarry, P. Analog circuit design optimization through the particle swarm optimization technique. Analog integrated circuits and signal processing 2010, 63, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, R.A.; Yildirim, T. Analog circuit sizing via swarm intelligence. AEU-International journal of electronics and communications 2012, 66, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H. Analog circuits design using ant colony optimization. International Journal of Electronics, Computer and Communications Technologies 2012, 2, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stutzle, T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE computational intelligence magazine 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.; Noije, W.A. Multi-objective design of analog integrated circuits using simulated annealing with crossover operator and weight adjusting. Journal of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2012, 7, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallem, A.; Benhala, B.; Kotti, M.; Fakhfakh, M.; Ahaitouf, A.; Loulou, M. Application of swarm intelligence techniques to the design of analog circuits: evaluation and comparison. Analog Integrated Circuits and Signal Processing 2013, 75, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lberni, A.; Marktani, M.A.; Ahaitouf, A.; Ahaitouf, A. Efficient butterfly inspired optimization algorithm for analog circuits design. Microelectronics Journal 2021, 113, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Echevarría, R.; Roca, E.; Castro-López, R.; Fernández, F.V.; Sieiro, J.; López-Villegas, J.M.; Vidal, N. An automated design methodology of RF circuits by using Pareto-optimal fronts of EM-simulated inductors. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2016, 36, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Zhang, L. Efficient parasitic-aware hybrid sizing methodology for analog and RF integrated circuits. Integration 2018, 62, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, E. Inversion coefficient optimization based analog/RF circuit design automation. Microelectronics Journal 2019, 83, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, E.; Dundar, G. A comprehensive analysis on differential cross-coupled CMOS LC oscillators via multi-objective optimization. Integration 2019, 67, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumanns, M. SPEA2: Improving the strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm. Technical Report, Gloriastrasse 35 2001.

- Zhou, R.; Poechmueller, P.; Wang, Y. An analog circuit design and optimization system with rule-guided genetic algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2022, 41, 5182–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, A.F.; Gandara, M.; Shi, W.; Pan, D.Z.; Sun, N.; Liu, B. An efficient analog circuit sizing method based on machine learning assisted global optimization. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2021, 41, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağlican, E.; Afacan, E. An Open-Source ANN-based Analog/RF Intellectual Property for SkyWater130nm Technology. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design (SMACD). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–4.

- İslamoğlu, G.; Çakıcı, T.O.; Güzelhan, Ş.N.; Afacan, E.; Dündar, G. Deep learning aided efficient yield analysis for multi-objective analog integrated circuit synthesis. Integration 2021, 81, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lberni, A.; Marktani, M.A.; Ahaitouf, A.; Ahaitouf, A. Analog circuit sizing based on Evolutionary Algorithms and deep learning. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 237, 121480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria-Borbón, A.C.; Soto-Aguilar, S.; Estrada-López, J.J.; Allaire, D.; Sánchez-Sinencio, E. Gaussian-process-based surrogate for optimization-aided and process-variations-aware analog circuit design. Electronics 2020, 9, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Xue, P.; Yang, F.; Yan, C.; Hong, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, D. An efficient bayesian optimization approach for automated optimization of analog circuits. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2017, 65, 1954–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, P.D. Advanced Methods in Neural Computing, 1993.

- Berkol, G.; Afacan, E.; Dündar, G.; Fernandez, E. A hierarchical design automation concept for analog circuits. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS). IEEE, 2016, pp. 133–136.

- Hassanpourghadi, M.; Su, S.; Rasul, R.A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.S.W. Circuit connectivity inspired neural network for analog mixed-signal functional modeling. In Proceedings of the 2021 58th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 505–510.

- Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Madhusudan, M.; Sapatnekar, S.S.; Harjani, R.; Hu, J. MMM: Machine Learning-Based Macro-Modeling for Linear Analog ICs and ADC/DACs. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024.

- Fayazi, M.; Taba, M.T.; Afshari, E.; Dreslinski, R. AnGeL: fully-automated analog circuit generator using a neural network assisted semi-supervised learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2023.

- Liñán-Cembrano, G.; Lourenço, N.; Horta, N.; de la Rosa, J.M. Design Automation of Analog and Mixed-Signal Circuits Using Neural Networks–A Tutorial Brief. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2023.

- Liu, M.; Tang, X.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Sun, N.; Pan, D.Z. OpenSAR: An open source automated end-to-end SAR ADC compiler. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference On Computer Aided Design (ICCAD). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–9.

- Passos, F.; Roca, E.; Sieiro, J.; Fiorelli, R.; Castro-López, R.; López-Villegas, J.M.; Fernández, F.V. A multilevel bottom-up optimization methodology for the automated synthesis of RF systems. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2019, 39, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Automatic Design for W-Band Front-End System via Bottom-Up Sizing and Layout Generation. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2023.

- Canelas, A.; Passos, F.; Lourenço, N.; Martins, R.; Roca, E.; Castro-López, R.; Horta, N.; Fernández, F.V. Hierarchical yield-aware synthesis methodology covering device-, circuit-, and system-level for radiofrequency ICs. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 124152–124164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkıran, H.; Sağlıcan, E.; Afacan, E. ANN-based Analog/RF IC Synthesis Featuring Reinforcement Learning-based Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design (SMACD). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–4.

- Blank, J.; Deb, K. Pymoo: Multi-objective optimization in python. Ieee access 2020, 8, 89497–89509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, R.; Jabbour, C.; Sakr, G.E. A review of machine learning techniques in analog integrated circuit design automation. Electronics 2022, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Optimization | Modeling | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Objectives and Constraints | Pseudo-Simulator | Pseudo-Designer | |||||||

| [m] | [] | Gain (max.) | BW (max.) | Power | PM | INPUTS (7): | INPUTS (4): Gain, BW, PM, Power | |||

| min | 0.13, 0.65 | 100 | – | OUTPUTS (4): Gain, BW, PM, Power | OUTPUTS (7): | |||||

| max | 1.3, 97.5 | 10k | – | – | – | – | NN Model: ReLU(64)-ReLU(128) | NN Model: ReLU(64)-ReLU(128) | ||

| Optimization | Modeling | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Objectives and Constraints | Pseudo-Simulator | Pesudo-Designer | |||||

| L [m] | W [m] | Power(min.) | Delay(min.) | INPUTS (5): | INPUTS (2): Power, Delay | |||

| min | 0.13 | 1 | mW | s | OUTPUTS (2): Power, Delay | OUTPUTS (5): | ||

| max | 1.3 | 80 | NN Model: ReLU(64)-ReLU(128) | NN Model: ReLU(64)-ReLU(128) | ||||

| Pseudo-Simulator | Pseudo-Designer | |

|---|---|---|

| Input | , , , , | Best fitted INL, DNL |

| Output | Best fitted INL, DNL | , , , , |

| NN Model | ReLU(64)-D.O(30%)-ReLU(64)-D.O(30%)-ReLU(64)-D.O(30%) | ReLU(64)-D.O(30%)-ReLU(64)-D.O(30%)-ReLU(128)-D.O(30%) |

| Time, MSE | Dataset Generation & Training: 30.5 hours, 0.01 | Dataset Generation & Training: 30.5 hours, 0.005 |

| Design Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | 0.13, 24 | 1k | 75 | 2 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| max | 1, 480 | 15k | 150 | 10 | 7.5 | 2.5 |

|

Obj.& Const. |

NF (min.) | Power (min.) | Freq. | |||

| – | ||||||

| Modeling | ||||||

|

Pseudo Simulator |

IN - ReLU(128) - ReLU(128) - OUT; IN (20): Design Parameters – OUT (5): S-params, Power, Noise Figure |

|||||

|

Pseudo Designer |

IN - ReLU(360) - D.O - ReLU(260) - D.O - ReLU(512) - D.O - OUT; IN (5): S-params, Power, Noise Figure – OUT (20): Design Parameters |

|||||

| min | 0.13 | 10, 10 | 0.5 | 10, 10 | 135 | 3 | 5 | 1.5 |

| max | 1 | 35, 500 | 6 | 30, 35 | 150 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 2.5 |

| Objectives & Constraints | Modeling | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Noise @1 MHz(min.) | -150 <PN [dBc/Hz] <-115 |

Pseudo Simulator |

IN - ReLU(64) - ReLU(64) - OUT; | |

| Power Consumption(min.) | <10 mW | IN (13): Design parameters – OUT (4): PN, power, signal amplitude, frequency | ||

| Oscillation Frequency | 2.39 < [GHz] <2.41 |

Pseudo Designer |

IN - ReLU(64) - ReLU(128) - OUT; | |

| Signal Amplitude @(3&7)ns | >1V | IN (4): PN, power, signal amplitude, frequency – OUT (13): Design parameters | ||

| Optimization | Modeling | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Objectives & Constraints | Pseudo-Simulator | Pseudo-Designer | ||||||

| Power (min.) | IP3 (max.) | CG | IN (5): ; OUT (3): Power, IP3, CG | IN (3): Power, IP3, CG; OUT (5): | |||||

| min | 0.13, 1 | 50 | mW | dB | dB | IN - ReLU(64) - ReLU(64) - OUT | IN - ReLU(360) - D.O. (50%) - ReLU(260) - D.O. (50%) - ReLU(512) - D.O. (50%) - OUT |

||

| max | 4, 500 | 300k | |||||||

| Pseudo-Simulator | Pseudo-Designer | |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Conversion Gain, IP3 | |

| Output | Conversion Gain, IP3 | |

| NN Model | ReLU-ReLU-DO(45%)-ReLU-ReLU-DO(25%)-ReLU-ReLU | ReLU-ReLU-DO(45%)-ReLU-ReLU-ReLU-ReLU |

| Time, MSE | Dataset Generation & Training: 32 hours, 0.124 | Dataset Generation & Training: 32 hours, 0.06 |

| Requested DNL (LSB) |

Requested INL (LSB) |

Requested Word Count |

Obtained DNL (Syhtnesis) |

Obtained INL (Syhtnesis) |

Obtained Word Count (Syhtnesis) |

Error DNL (LSB) % |

Error INL (LSB) % |

Synthesis Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.166 | 0.0653 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.0648 | 256 | 0 | 0.76 | 890 |

| 0.5 | 0.0736 | 256 | 0.566 | 0.0744 | 256 | 13.2 | 1.08 | 940 |

| 0.166 | 0.0921 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.0986 | 256 | 0 | 7.05 | 890 |

| 0.2 | 0.1337 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.1338 | 256 | 17 | 0.07 | 990 |

| 0.166 | 0.1494 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.1522 | 256 | 0 | 1.87 | 830 |

| Design Specifications | Model Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNL (LSB) | INL (LSB) | Word Count | DNL (LSB) | INL (LSB) | Word Count | ||

| <0.5 | <0.5 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.24 | 256 | ||

| <0.5 | <0.5 | 256 | 0.133 | 0.445 | 256 | ||

| <0.5 | <0.5 | 256 | 0.233 | 0.508 | 256 | ||

| <0.5 | <0.5 | 256 | 0.233 | 0.364 | 256 | ||

| <0.5 | <0.5 | 256 | 0.166 | 0.149 | 256 | ||

| Top-to-bottom | Bottom-to-top | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requested CG (dB) |

Requested IP3 (dB) |

Obtained CG (Syhtnesis) |

Obtained IP3 (Syhtnesis) |

Error CG (dB) % |

Error IP3 (dB) % |

Synthesis Time (ms) |

CG (dB) >-10 |

IP3 (dB) >-10 |

|

| -9.34 | -5.76 | -9.61 | -6.31 | 2.89 | 9.54 | 770 | -5.47 | -6.13 | |

| -8.38 | -5.9 | -8.4 | -6.06 | 0.23 | 2.71 | 850 | -5.59 | -6.15 | |

| -9.34 | -5.8 | -9.29 | -5.9 | 0.53 | 1.72 | 980 | -5.72 | -6.07 | |

| -12.62 | -3.55 | -12.65 | -3.97 | 0.23 | 11.83 | 730 | -5.8 | -6.98 | |

| -10.34 | -5.76 | -10.81 | -6.16 | 4.54 | 6.94 | 940 | -6.52 | -8.28 | |

| [42] | [44] | [45] | [46] | This Work | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Circuit Complexity |

Three-stage OPAMP & active filter topologies |

SAR ADC | RF front-end receiver | W-Band front-end receiver |

Full-flash ADC & RF front-end receiver |

|

Synthesis Direction |

Top-to-bottom | Top-to-bottom | Bottom-to-top | Bottom-to-top | Both direction |

|

Automation Method |

Tool firstly decides propoer sub-circuit. As following step NN classfier determine tran- sistor level topology. Finally, tool sizes all-sub-circuits via local and global optimization, which are carried out by PSO and NN, respectively. |

Top level specs are mapped to components via design equa- tions. Digital part uses redun- dancy optimizaiton, while ana- log relies on Bayesian optimi- zation. Layouts of the analog part generated automatically. |

Firstly, PoFs are generated for inductor using surrogate mo- dels. As a second step, subcir- cuits are synhtesized, where in- ductors are selected from exis- ting PoFs via matrix mapping technique. The same flow conti- nues to acheive top-level. |

Component libraries are pre- pared to utilize in an optimiza- tion loop. These libraries faci- litate the RF sub-block synthe- sis without compromising accu- racy. Pre-existed PoFs of the sub-blocks are used to achieve high-level synthesis. |

All system sub-blocks are synt- hesized while generating corres- ponding circuit dataset. Each sub-block is modeled bi-directi- onally. At the system level, cir- cuits are only represented by design specifications, and ANN models handle synthesis both directions. |

|

Used Algorithms |

NN classifier/regressor, PSO |

Design equations, redundancy optimization, BO |

Surrogate Model, EA | EA | ANN, EA |

| Accuracy | for OPAMP 94.1% & for filter 94.6% |

User intervention may be required in the synthesis. |

Approximately 99% | Not specified | **Receiver Model: 95.89% & *ADC Model: 95.9% |

| Speed | OPAMP: 9.4 h & filter: Not specified |

2 h | 27 h | 16.5 days | *BT for receiver: 35.5 h & for ADC: 34 h TB for receiver: 35 h & for ADC: 31 h |

|

Key Propoerty |

Dataset expansion via NN reduces training time. |

ADC layouts are generated based on user requests |

Stored PoFs can be reused for any circuit operating in the same band. |

Different topologies can be efficiently synthesized using the libraries. |

Sub-block models enable rapid synthesis even for out-of-space design requests. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).