1. Introduction

Postharvest preservation of horticultural crops is crucial for reducing global food loss and ensuring a stable supply. Among these technologies, drying has emerged as one that greatly extends shelf life by significantly limiting microbial growth and enzymatic activity [

1]. Carrots (Daucus carota L.) are one of the most important root vegetables worldwide, not only because they are widely used in different culinary forms but also due to their rich content of bioactive compounds. This phytochemical profile is genotype-dependent. Orange carrots are rich in carotenoids like β-carotene, which is a provitamin A compound, while black carrots represent a significant source of stable anthocyanins, contributing greatly to health [

2].

However, despite such widespread use, drying triggers adverse physicochemical transformations that could degrade critical quality attributes beyond acceptability. Among those, microstructure is highly sensitive, which plays a decisive role in functional properties such as rehydration and color integrity, directly linked with pigment stability. The major drawbacks of pigment oxidative degradation and cellular structural collapse, appearing as color loss and poor rehydration capacity, still remain a big challenge to be overcome in the conventional drying process [

3].

HAD is still an industrially widely used drying method because of its operational simplicity and uniformity of dehydration. However, the consequent heat transfer by convection normally involves long processing time, high energy density, and severe thermal degradation of heat-sensitive nutrients and pigments [

4]. IRD presents a more sophisticated and innovative technology that directly applies radiant energy to water molecules in the product matrix. The related mechanism, due to its higher efficiency, enables rapid heating and considerably reduces the drying time. However, one of the serious problems facing IRD systems is surface overheating, especially with geometrically complicated samples, which may result in nonuniform moisture profiles. This may lead to deterioration of product quality [

5].

It is within this framework that hybrid drying strategies have emerged to overcome hot air and infrared drying, considering the commonly used methods result in long-lasting, energy-negative impacts. Recently, the IRD-HAD system has attracted particular attention in drying processes due to its high potential. This integrated system combines the advantages of infrared drying and hot air drying methods, which are desired but not wholly achieved by both individual methods. It utilizes intensive infrared pretreatment for fast initial moisture removal and then finally completes drying by hot air at a final gentle stage to reach uniform final moisture content and product stabilization. The synergy of the system enhances drying efficiency while maintaining product quality [

6,

7].

While this is true for drying kinetics and quality criteria for many fruits, vegetables, and other foods, direct and systematic studies in comparing orange and black carrots using HAD, IRD, and combined IRD-HAD processes are noticeably missing in the literature. Given their different chemical structures, the dominant pigments in these varieties of carrots (lipophilic carotenoids and hydrophilic anthocyanins) may also differ significantly in stability under different thermal regimes. A comparative assessment of the influence of the drying technologies applied on quality indices, namely color accuracy and rehydration capacity-an immediate indicator of microstructural integrity-for these two cultivars of carrots, is required.

This study, therefore, carries out a comprehensive comparative analysis on the effect of hot air drying, infrared drying, and their combination on the drying kinetics and quality characteristics of orange and black carrot slices. It is hypothesized that the combined IRD-HAD approach will be superior to individual methods by enhancing drying kinetics and preserving color and rehydration capacity in both genotypes. Specific objectives are as follows: (1) to evaluate and model the drying kinetics for each carrot cultivar and method; (2) to quantify the effect on color parameters, L*, ΔE, and BI, to determine the stability of pigments; and (3) to analyze rehydration characteristics as an indication of structural damage and final product quality. The findings will give useful information for the development of genotype-specific drying protocols aimed at maximizing functional and sensory property preservation in dried carrot products.

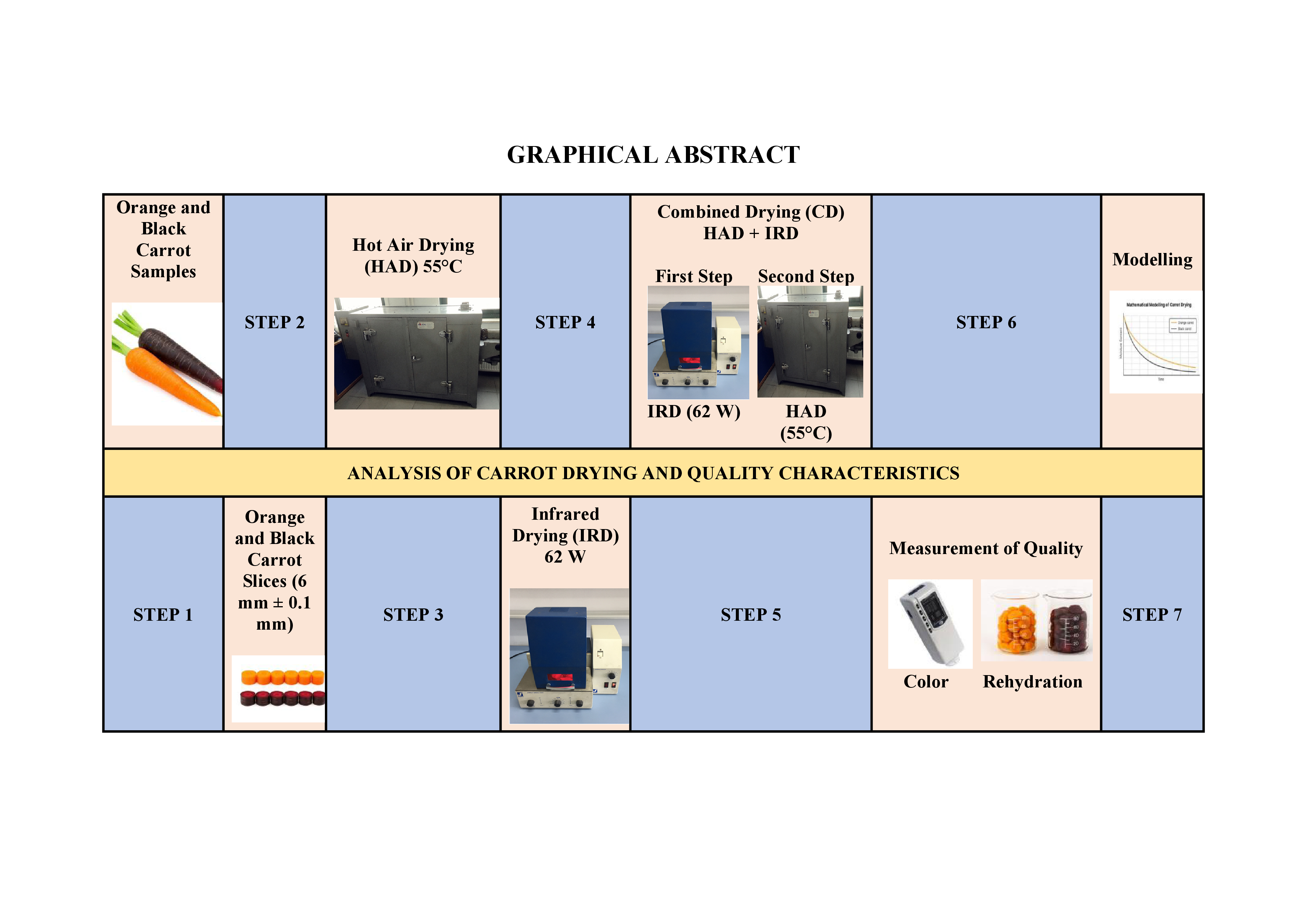

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Carrot Preparation

Orange carrots (Daucus carota L.) of the Ankara-Beypazarı genotype and black carrots of the Konya-Ereğli genotype (Daucus carota L. spp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) were obtained commercially. After receiving them, carrot roots were kept in a climate chamber at 4 ± 0.1°C to keep them fresh before further processing. For measurements, carrots were cleaned with tap water, peeled manually, and then sliced mechanically to obtain uniform discs of 6 ± 0.1 mm thickness. To provide a basis for comparison, the moisture content of raw materials was determined in triplicate using the official guidelines of AOAC (2016) [

8]. All preparatory steps were fully standardized between samples to ensure homogeneity and allow for experimental reproducibility.

2.2. Drying Protocols

Three different methods were used to analyze the drying behavior: convective drying (HAD), infrared drying (IRD), and infrared-convective combined drying (IR-HA). In the HAD process, samples were dried in a tray dryer (APV & PASILAC Limited, UK) operating at 55°C temperature with a constant air flow velocity of 2 m/s. The infrared drying technique was performed using an infrared moisture analyzer, Snijders Moisture Balance (Snijders b.v., Netherlands), which was used under constant radiant power of 62 W. In the infrared-convective combination method of IR-HA, carrot slices first underwent some predrying in the infrared system for 30, 60, or 90 minutes, respectively; afterward, they were sent for HAD at 55 °C to attain a final moisture content of 10% on a dry basis. Each drying experiment was performed three times to ensure reliability in the data.

2.3. Drying Kinetics and Mass Transfer Analysis

Drying performance was carefully investigated to find the reduction of moisture loss from carrot slices as a function of time. The following parameters were calculated for the study of drying kinetics and to determine basic mass transfer properties.

2.3.1. Moisture Ratio

Moisture ratio of carrots slices dried in all drying systems was determined in Equation (1) [

9]:

where M, M₀, and Mₑ are the moisture content at time t, the initial moisture content, and equilibrium moisture content, respectively, in g water/g dry solid. It has been observed that under the high temperature drying conditions, the value of Mₑ is negligible compared to M0 and Mt [

9]. Therefore, MR was simplified as in Equation (2) for model fitting and kinetic analysis:

The following form is widely adopted in thin-layer drying kinetics analyses of food materials [

10]:

2.3.2. Effective Moisture Diffusivity

Deff is a critical transport property that represents internal resistance to moisture movement through a solid matrix. Application of Fick's second diffusion law has been employed for the determination of effective moisture diffusivity. For one-dimensional moisture movement, an infinite plate geometry, constant diffusion coefficient, and homogeneous initial distribution, the solution takes the form of Equation (3) [

11]:

For long drying times, the solution converges rapidly and the logarithmic form, retaining only the first term (n=0), is a reliable linear model as indicated in Equation (4):

where L is the half thickness of the carrot slice (m). The effective moisture diffusion coefficient was calculated as in Equation (5) from the slope (K) of the linear regression between ln(MR) and time (t):

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean values ± SD.

2.4. Mathematical Modelling of Drying Kinetics

The thin-layer drying behavior of carrot slices has been mathematically characterized by fitting the experimental MC data to eleven established models based on drying time, as outlined in detail in

Table 1.

The empirical, semi-empirical, and theoretically derived approaches have been selected since such models have proven benefits in describing the phenomenon of moisture transport in porous food materials. The model parameter estimates were carried out using nonlinear regression analysis implemented in TIBCO Statistica®, version 14.1.0, 2023, which minimizes the sum of residual squares between experimental and predicted MR values. The suitability of each model was statistically tested based on the coefficient of determination, R²; root mean square error, RMSE; and reduced chi-square, χ². The model with the highest R² value and the lowest RMSE and χ² values was selected as the best model for the carrot slice drying kinetics. All the parameter estimates were done with a 95% confidence interval.

2.5. Colorimetric Evaluation and Browning Index

Color of the surface was measured using a handheld colorimeter (PCE-CSM 1) in triplicate and mean values for CIE L, a, b* were recorded. The total color difference (ΔE) from fresh carrot slices (L₀, a₀, b₀) was then calculated by the Equation (6) [

23]:

The Browning Index (BI) was developed to quantify the intensity of non-enzymatic browning. BI is a good indicator of color change promoted by heat treatment and the advancement of the Maillard reaction, and it was determined by the Equation (7) and Equation (8) [

24]:

where

2.6. Evaluation of Rehydration Properties

Drying food matrices' rehydration behavior is an important indicator of the degree of cellular and structural integrity conserved during the process of dehydration. The rehydration capacity is inversely proportional to the rate of the physicochemical deterioration, thus being an important criterion for the evaluation of quality of the final product and efficiency of process [

25].

The kinetics of rehydration of dried carrot slices were studied by soaking in distilled water (solid-solvent ratio 1:100 w/v) at 30.0 ± 0.5°C for 7 hours until almost saturated. After hydration, the samples were taken out and drained on a standard sieve for 120 seconds to remove unbound surface water and then dried with laboratory-grade absorbent paper. Rehydration performance was quantified by two main criteria: Rehydration Ratio (RR) and Water Absorption Capacity (WAC).

Rehydration Ratio is the mass of the hydrated sample compared to its initial dry mass and calculated by the Equation (9) [

25]:

where Wᵣ and Wd denote the mass of the rehydrated and dried samples, respectively.

WAC is expressed as a percentage and represents the mass of water absorbed and retained per unit mass of dry matter and calculated by the Equation (10) [

26,

27]:

All analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure statistical accuracy and results are reported as mean values ± standard deviation.

2.7. Statistical Evaluation

Data were analyzed using TIBCO Statistica® version 14.1.0, 2023; TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA. Model parameters have been estimated through nonlinear regression using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. To describe model fit, R², reduced chi-square (χ²), and RMSE were employed-a comprehensive approach for describing fit and prediction accuracy. All experiments were repeated three times. To investigate the influence of drying method and variety of carrot, a two-way ANOVA was performed; significant differences (p < 0.05) were further examined for pairwise comparisons by Tukey's HSD post-hoc test.

3. Results

This study describes the complex interactions among dehydration methodology, moisture transport mechanism, and the preservation of physicochemical and quality properties for two different carrot varieties, orange and black. Clearly, the results show that the drying mechanism, together with the structural and biochemical composition of the plant matrix, dictates not only the kinetics of water removal but also the functional, nutritional, and sensory properties preserved in the final dehydrated product. Thus, statistical and mechanistic approaches were used to analyze drying kinetics, rehydration performance, and chromatic behavior in order to create a holistic framework linking process parameters to microstructural and quality outcomes.

3.1. Drying Time and Effective Moisture Diffusion Coefficient (Deff)

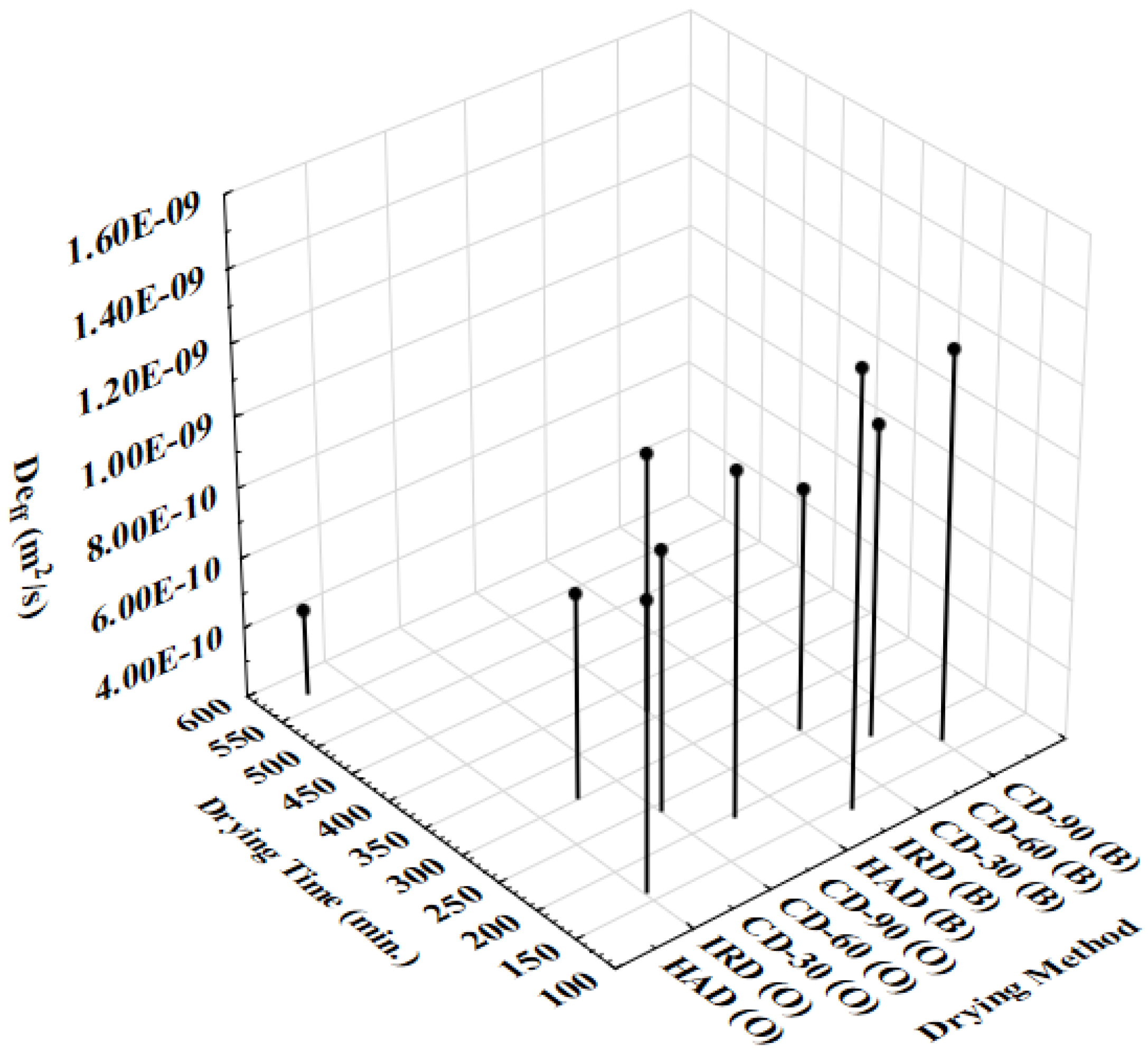

Kinetic analysis showed that the drying method and product type were statistically significant factors that determined Deff and total drying time. Interaction between the two factors can be explained by the hypothesis that the drying kinetics are controlled by a synergistic relationship between the intrinsic properties of the plant tissue and the drying method applied. Results for carrot types are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1; orange and black carrots gave significantly different results to the various drying protocols.

HAD resulted in the longest dehydration times and the lowest effective moisture diffusivity values for Deff in both carrot cultivars; thus, it indicates that moisture removal is limited mainly by external mass transfer resistance and thermal conduction within the porous tissue matrix [

28]. Orange carrots took 570 min to reach the target moisture content, and its effective moisture diffusivity (Deff) value was calculated as 4.44 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s. Whereas, this time was 360 min for black carrots, and its Deff value was found to be 5.23 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s. The results agree with the previous reports that mentioned underlined slow migration of moisture inside the carrot matrix due to the drying system and, hence, the longer drying time, which may increase oxidative pigment and tissue degradation [

29,

30].

Unlike the convective hot air drying system, infrared drying (IRD) significantly increased the drying rate, decreasing the total drying time about 60–70% as compared to HAD. The orange carrots reached the target moisture level in 160 min with a Deff value of 1.40 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s; for black carrots, this took 140 min with a corresponding Deff of 1.42 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s. The significant difference observed could be attributed to the volumetric heating effect due to which infrared radiation directly stimulates the water molecules to initiate the vapor formation inside the carrot samples and creates a considerable vapor pressure gradient that acts as a trigger for moisture migration [

31]. This is in agreement with the studies of Lee et al. [

32] and Teymori-Omran et al. [

33], who reported that infrared treatment enhances moisture flux and better retention of bioactive compounds by reducing exposure to convective losses.

Combined Drying (CD) approaches shortened the drying time with progressive enhancement of Deff and provided an extension of IR pretreatment times. For orange carrots, Deff values ranged from 7.79 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s for the CD-30 to 1.17 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s for the CD-90, while for black carrots, the respective increase was from 8.88 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s for the CD-30 to 1.30 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s for the CD-90, corresponding to a reduced drying time from 300 min to 195 min and from 255 min to 165 min, respectively. This confirms the synergistic effect between the series combination of IR and convective mechanisms. After the rapid removal of surface and capillary moisture, the controlled convective desorption of bound water, without immediate surface hardening and structural collapse, occurs due to IR radiation [

34]. CD-90 emerged as the best treatment protocol from all of the combined drying protocols in terms of balancing high diffusion against the minimum drying time. It also agrees with the findings on similar root vegetable systems. The time required for yam slices to achieve target moisture content using IR-HAD at 50, 55, 60, 65, and 70°C was 270, 240, 195, 180, and 165 minutes, respectively, as reported by Zhang et al. [

35]. On the other hand, conventional HAD required 405, 360, 315, 270, and 240 minutes at the same temperatures. IR-HAD hence cuts drying time by approximately 31–38% compared to HAD. Taghinezhad et al. [

36] demonstrated that turnip samples dried by hybrid convective–infrared (HCIR) drying recorded significantly shorter drying times, though this varied depending on the pretreatment method used. Once combined with any pretreatment methods like microwave or ultrasound, HCIR drying has considerably increased the drying rate due to increased moisture diffusion and evaporation rates. This explains the potential benefits of HCIR technology combined with advanced pretreatment methods to achieve fast and efficient dehydration processes and can be applied to large-scale, high-throughput food processing. A clear trend was also observed in the experiment regarding the response of the two tested cultivars. Black carrots have given consistently shorter drying time and slightly higher Deff values in all drying regimes. These cultivar-dependent effects are in agreement with the literature, as Swiacka et al. [

38] showed that significant factors affecting drying kinetics are related to tissue morphology and biochemical composition.

3.2. Modelling of Drying Kinetics

The drying kinetic of orange and black carrot slices was investigated using eleven well-known thin-layer drying models to characterize the moisture removal behavior under hot air, infrared, and combined drying systems. The corresponding model constants and statistical parameters for oranges and black carrots are given in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. Considering all the models tested, the Midilli and Kucuk model showed the best fit for both varieties of carrot and gave an excellent predictive capability in representing the drying process.

In

Table 3, R² values for the drying of orange carrots are in the range of 0.9998-0.9999, while χ² and RMSE values vary between 0.0014-0.0032 and 0.0033-0.0059, respectively. Similar values for black carrots are given in

Table 4; there, the R² values also ranged from 0.9998 to 0.9999, and χ² and RMSE values varied from 0.0010 to 0.0034 and from 0.0033 to 0.0049, respectively. These statistical indicators confirm the excellent fit between the experimental and predicted MR values, establishing the Midilli-Küçük model as the most reliable model for describing the drying kinetics of both carrot types.

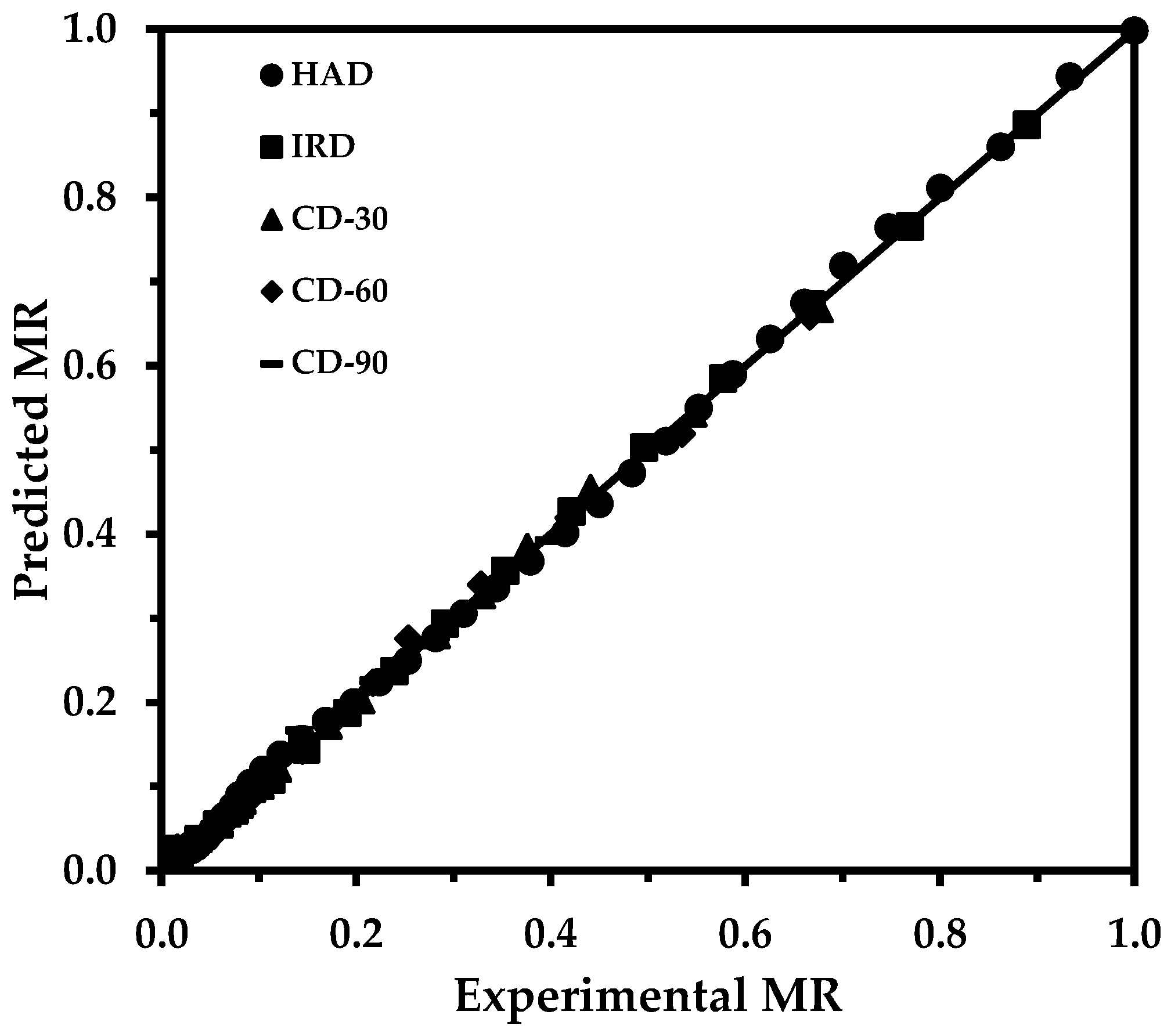

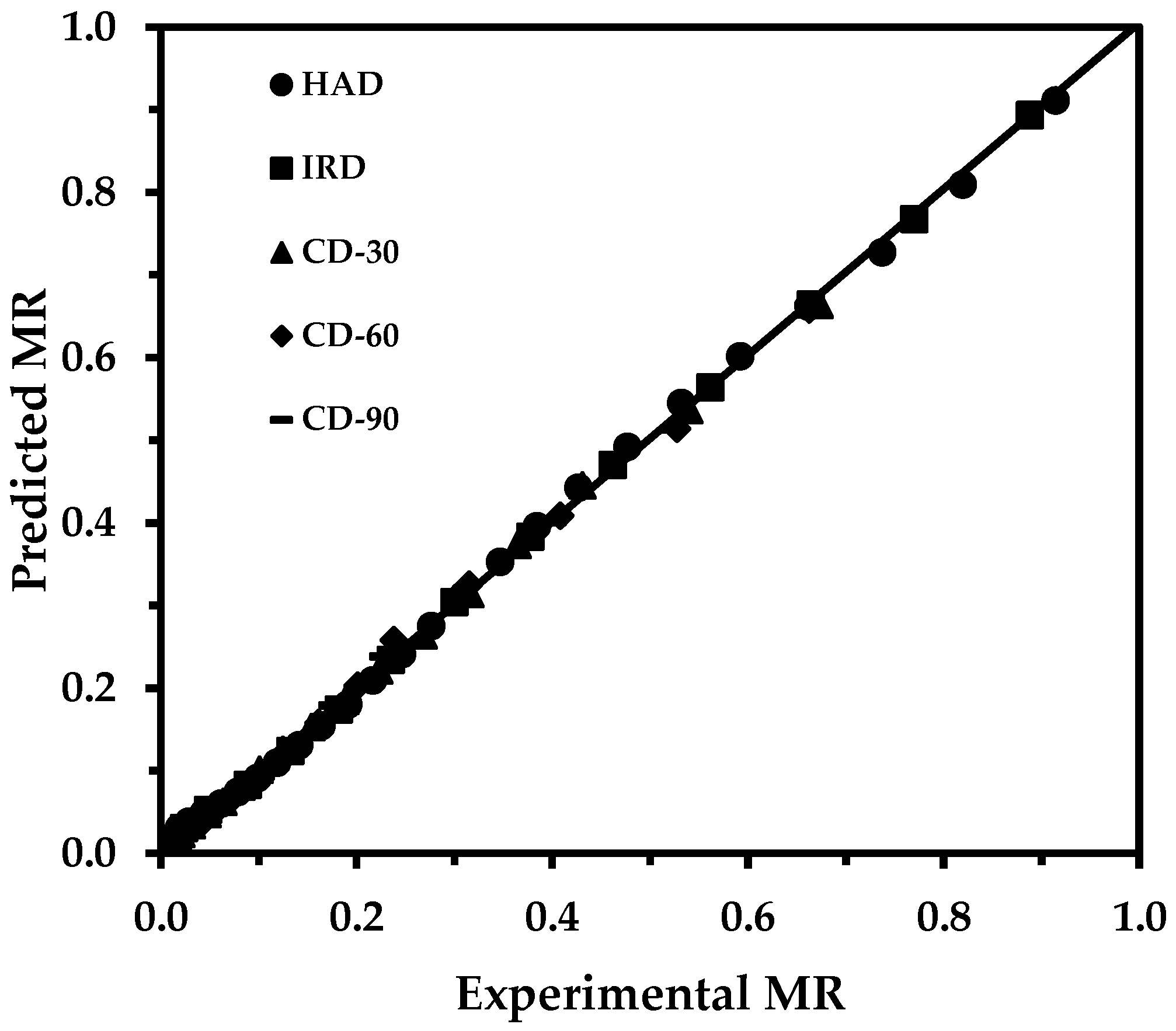

The parity graphs for orange and black carrot varieties are presented in

Figure 2 and 3, respectively, demonstrating a good fit between the experimental and predicted moisture content. The proximity of the data points to the line of equality at a 45° angle and the minimal dispersion confirm the robustness of the Midilli and Küçük model. Excellent concordance gives evidence that the model represents the main physical processes controlling the drying behaviour of carrot slices under the variation of operating conditions tested, namely internal moisture diffusion and surface evaporation.

Figure 2.

Experimental vs. Predicted MR for Midilli & Kucuk model for orange carrot.

Figure 2.

Experimental vs. Predicted MR for Midilli & Kucuk model for orange carrot.

Figure 3.

Experimental vs. Predicted MR for Midilli & Kucuk model for black carrot.

Figure 3.

Experimental vs. Predicted MR for Midilli & Kucuk model for black carrot.

Moreover, the robustness of the model across all three drying methods, namely, hot air, infrared, and combined drying, further underlines the wide applicability of process modeling, optimization, and industrial-scale drying control. Results of this modeling study are in good agreement with those by Kidane et al. [

39], Rida et al. [

40], and Ambawat et al. [

41], and also indicated that the Midilli and Küçük model was the best in describing the thin-layer drying characteristics of agricultural products. Thus, both orange and black carrot slices dried, and the Midilli and Küçük models were found to best represent the drying kinetics with high coefficients of determination, low error indices, and excellent proximity of data points to the 45° equivalence line, proving their appropriateness in modeling, simulation, and optimization of the industrial drying of crops.

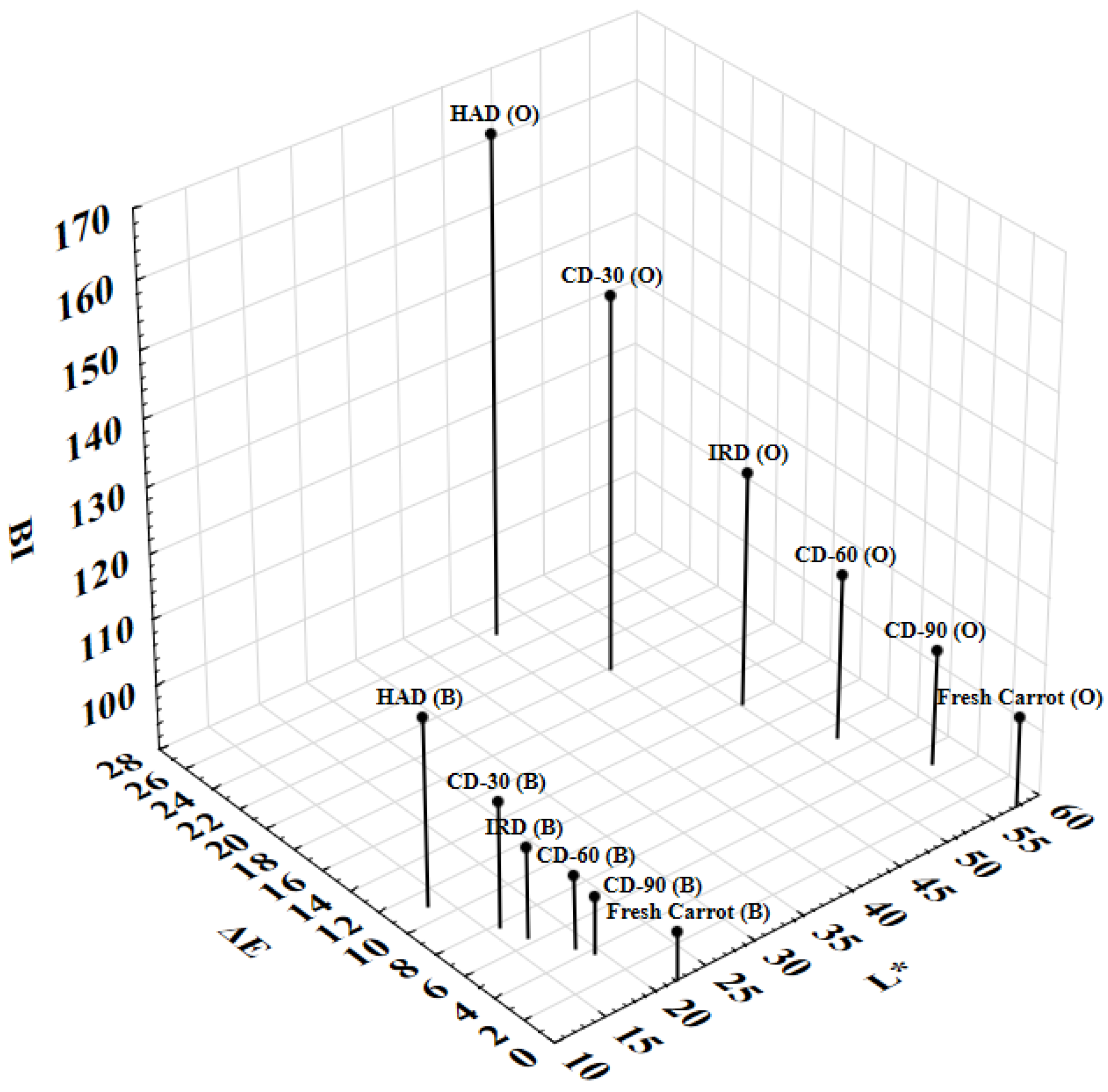

3.3. Chromatic Stability and Preservation of Pigment

Colorimetric analyses directly measure the visual quality of dried products and quantitatively reflect the chemical and structural transformations induced by different drying methods. Colour is considered one of the most important sensory parameters and a key indicator of biochemical integrity, while it is also directly related to the level of preservation of carotenoids, anthocyanins, and phenolic compounds responsible for the nutritional value and consumer acceptance of foods [

42,

43]. Color analysis results of carrots after being dried are summarized in

Table 5 and graphically presented in

Figure 4.

The results of experimental tests showed that both drying method and variety significantly affected the chromatic properties of orange and black carrots. By two-way ANOVA, significant main effects of drying method, carrot cultivars, and their interaction were found on L*, ΔE, and BI values, confirming the complexity of the process and pigment stability (p < 0.05). Tukey's HSD test clarified specific differences between groups.

Fresh orange carrots had a high lightness L* = 57.40 ± 0.69, minimum ΔE = 0.00 ± 0.00, and a baseline BI of 104.0 ± 0.4, which refers to natural visual quality. Convective hot air drying, HAD at 55°C, provoked the greatest discoloration in carrot samples, reducing L* to 41.29 ± 1.12 and increasing ΔE to 25.50 ± 0.70, while increasing BI to 165.5 ± 0.8. High discoloration is indicative of extensive Maillard and caramelization reactions accompanied by oxidative degradation of carotenoids as previously established [

44,

45].

Infrared drying (IRD, 62 W) significantly improved color retention with values of L* = 50.14 ± 0.41, ΔE = 13.77 ± 0.27 and BI = 125.8 ± 0.4. This is because volumetric energy absorption and rapid water removal reduce the exposure of chromophores to high-temperature oxidative stress [

46,

47].

Infrared pretreatment significantly and progressively improved chromatic quality in combined drying protocols. While L* = 45.10 ± 0.26, ΔE = 19.83 ± 0.45, and BI = 147.2 ± 0.8 were obtained for CD-30, L* increased to 52.90 ± 0.59, ΔE decreased to 9.03 ± 0.35, and BI decreased to 115.3 ± 0.6 for CD-60. Near-native color values were obtained for the CD-90 treatment (L* = 56.29 ± 0.54, ΔE = 4.80 ± 0.20, BI = 107.6 ± 0.4), which showed that the rapid moisture removal caused by IR reduced pigment degradation due to the synergistic effect of controlled hot air finishing while maintaining structural integrity [

48].

Fresh black carrots had a naturally darker L* value at 22.05 ± 0.19, indicative of anthocyanin build-up. HAD significantly decreased L* to 13.30 ± 0.54, with ΔE increasing to 10.92 ± 0.17 and BI reaching 118.5 ± 0.5, highlighting the sensitivity of anthocyanins to extended thermal stress and oxidation [

49]. IRD counteracted these changes to a certain extent, giving a L* of 16.74 ± 0.15, ΔE = 6.40 ± 0.26, and BI = 103.6 ± 0.4.

The pigment retention was also enhanced by the CD treatments. Thus, the following values were obtained: L* = 15.89 ± 0.32, ΔE = 7.73 ± 0.30, and BI = 109.1 ± 0.6 for CD-30, while for CD-60, L* was further increased to 18.61 ± 0.24, ΔE = 4.47 ± 0.21, and BI = 101.1 ± 0.3. Maximum color preservation was obtained for CD-90: L* = 19.31 ± 0.12, ΔE = 3.60 ± 0.20, and BI = 99.0 ± 0.2, reflecting better anthocyanin stability for rapid IR-assisted dehydration followed by convective finishing. This result agrees with previous observations indicating that although anthocyanins are heat-sensitive, under controlled thermal regime conditions they may exhibit enhanced stability when sequestered in intact vacuoles [

50,

51].

Because of their structurally dark anthocyanin pigments, the absolute lightness value of black carrots was always lower than that of orange carrots through all treatment conditions. However, lower ΔE values measured in black carrots during the IR and CD treatments indicate that anthocyanins have a higher thermal stability compared to β-carotene. The trends in BI further confirm this, with HAD increasing browning more intensely in orange carrots (BI = 165.5 ± 0.8) compared to that in black carrots (BI = 118.5 ± 0.5), presumably due to the differential susceptibility of carotenoids to oxidative degradation.

Results obtained show that hybrid drying methods, and specifically the CD-90 method, preserve color clarity as well as pigment stability by reaching an optimum between fast moisture removal and limited thermal exposure. The results show that varietal drying protocols play a significant role in maintaining qualitative appearance and functional quality during dehydration of root vegetables. These data strongly support the industrial-scale applicability of IR-assisted hybrid drying systems for the processing of high-value-added vegetable products [

52,

53,

54].

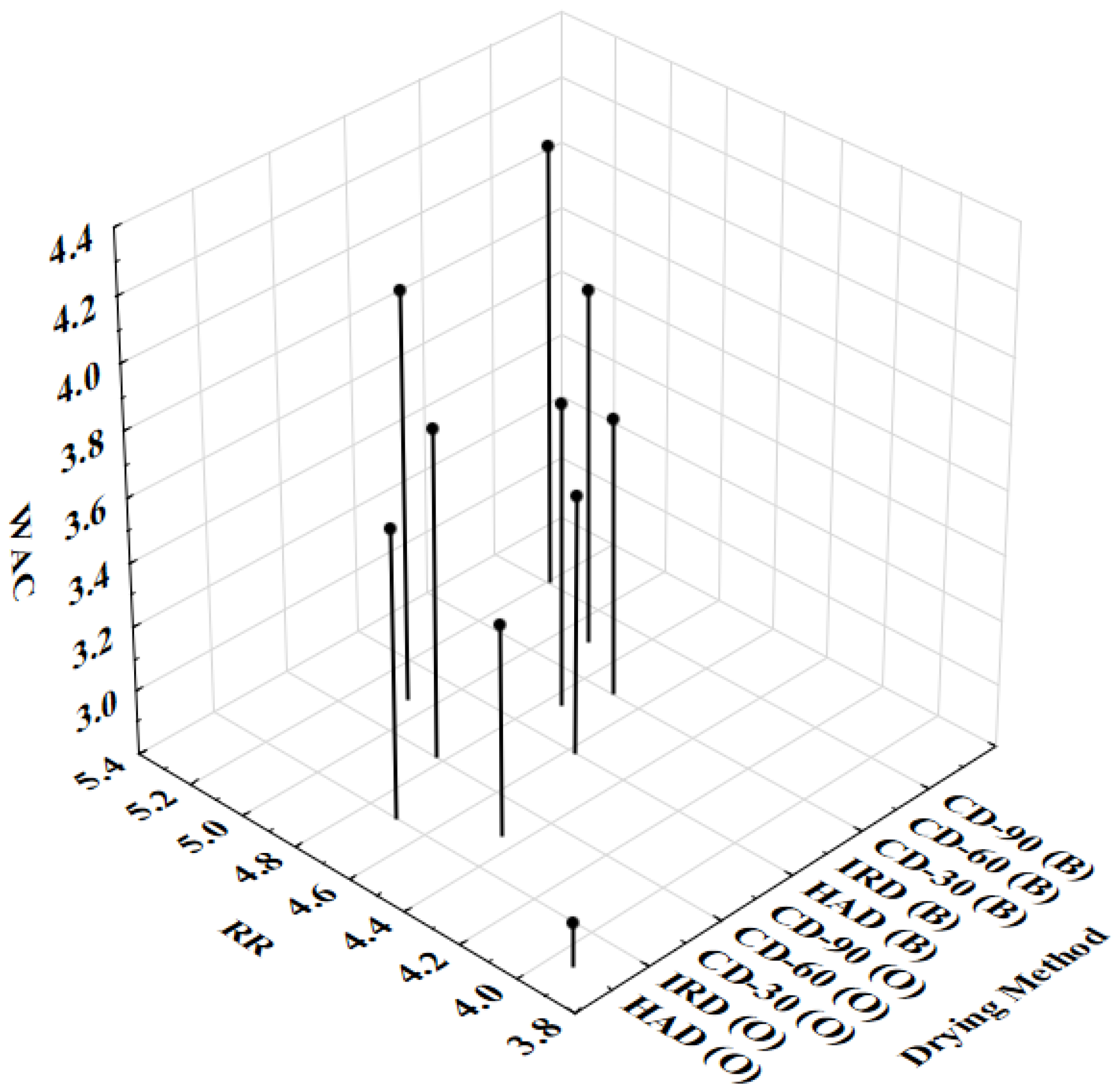

3.4. Rehydration Characteristics

It is now widely accepted that rehydration capacity reflects the preservation of microstructural integrity of dried plant tissues, a parameter responsible for the ability of a sample to reabsorb water, at least partially recovering its original morphology [

55].

Table 6 presents the final Rehydration Rate (RR) and Water Absorption Capacity (WAC) values for orange and black carrot cultivars during 7 h of rehydration period under standard conditions.

Figure 5 shows in graphical form the variation of RR and WAC values according to drying systems and carrot cultivars..

Convective hot air drying (HAD, 55 °C) yielded the poorest rehydration performance of all treatments. Orange carrots dried by HAD showed a RR of 3.93 ± 0.07 and a WAC of 2.94 ± 0.04 g/g, whereas that for black carrots reached a RR = 4.57 ± 0.05 and WAC = 3.61 ± 0.03 g/g. These lowered values evidence extensive structural collapse, hornification of cellulose networks, and partial starch gelatinization, which together reduce capillary connectivity and inhibit water uptake [

56]. The pronounced difference between HAD-treated orange and black carrots further reflects intrinsic varietal differences wherein the denser parenchymal structure and higher content of phenolics in black carrots mitigate collapse and maintain moderate rehydration [

57].

IRD at 62 W significantly enhanced the water absorption and tissue healing ability of carrots. Orange carrots treated by IRD reached an RR value of 4.70 ± 0.02 and a WAC of 3.70 ± 0.02 g/g, while for black carrots the corresponding values were RR = 4.75 ± 0.02 and WAC = 3.75 ± 0.03 g/g. The improved performance is attributed to volumetric heating and rapid moisture removal that minimized the accumulation of mechanical stresses and preserved the internal porosity, facilitating efficient water diffusion during rehydration [

58].

Combined drying (CD) protocols further improved structural adhesion, and the improvements showed correlation with the duration of IR pretreatment. For orange carrots, RR gradually increased from 4.45 ± 0.01 (CD-30) to 4.82 ± 0.04 (CD-60) and reached 5.07 ± 0.03 for CD-90, while WAC correspondingly increased from 3.46 ± 0.02 to 3.82 ± 0.02 to 4.07 ± 0.03 g/g for carrots. Black carrots presented RR = 4.69 ± 0.02, 4.91 ± 0.06 and 5.19 ± 0.03, WAC = 3.67 ± 0.02, 3.91 ± 0.02, 4.18 ± 0.02 g/g for CD-30, CD-60 and CD-90, respectively. The superior performance of CD-90 samples indicated that initial IR-induced rapid moisture removal creates vapor-mediated microchannels to maintain the three-dimensional capillary networks and prevent excessive tissue shrinkage of the samples. This allowed a gentle removal of the remaining moisture by the subsequent convective finishing step, minimizing structural deformation and favoring maximum water absorption during the rehydration process [

59].

Under all drying conditions, black carrots exhibited consistently higher RR and WAC values than orange carrots, indicating a stronger preservation of textural integrity. This difference can be attributed to a more developed parenchyma cell structure and the comprehensive stabilizing effect of phenolic images, both of which can effectively limit tissue collapse caused by the thermal dehydration process [

60,

61]. The processed and rehydrated carrot samples presented in

Table 6, along with previous studies on the cultivation of root vegetables, demonstrate that hybrid drying techniques, in this study, enhanced rehydration processes and preserved tissue structure [

62]. Overall, these findings demonstrate that optimizing dehydration rates for both the variety and the targeted product properties is clearly evident. In particular, IR-assisted hybrid regime methods with the CD-90 configuration offer an effective approach for preserving microstructural integrity and maximizing functional rehydration capacity. This creates a viable solution for high-quality vegetative regional production.

3.5. Overall Optimization, Energy Efficiency, and Industrial Applicability

The hybrid drying protocol of CD-90 brings a better result compared to conventional hot air and infrared methods alone in preserving the nutritional and functional quality parameters of carrot varieties. This potential makes it an effective strategy for industrial-scale drying of carrot varieties.

In comparison to the conventional HAD system, the CD-90 protocol reduced the total drying time for orange carrots from 570 to 195 minutes and that of black carrots from 360 to 165 minutes, thus giving a significant drying time reduction by about 55-65%. This reduction in drying time also contributes to a reduction in energy demand, hence increased overall thermal efficiency.

From the point of view of process scalability, the application of sequential IR pretreatment with HAD offers a flexible and adaptable framework for industrial applications. First, IR modules quickly remove moisture from the carrot surface and make the development of internal microchannels possible. Then, the stage of HAD performs a controlled desorption of bound water. This combination not only allows for a short drying time but also reduces thermal stress applied to the tissues, minimizing the risk of structural collapse and shrinkage.

In regard to product quality, the CD-90 protocol constantly had the highest rehydration ratio and color retention for both cultivars. In black carrots, the highest RR (RR = 5.19 ± 0.03) and WAC (WAC = 4.18 ± 0.02 g/g) were noted, while superior color characteristics (ΔE ≤ 4.8, BI ≤ 107.5) were retained in orange carrots. These data indicate less cellular damage and a high pigment stability, enhancing the sensory, nutritional, and functional quality. These quality criteria meet the growing consumer demand for minimally processed dried vegetable products rich in nutrients.

Consequently, IR-assisted hybrid drying can be regarded as both a technological and economically favorable way of drying carrots or, generally, colored root vegetables rich in anthocyanins or carotenoids. The CD-90 protocol achieved faster drying kinetics with reduced energy consumption and better retention of quality attributes, hence being industrially suitable for sustainable, high-yield, and high-quality food processing.

3.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite this valuable contribution, there are some limitations to the applicability of the present study to the industrial field. The experiments were performed under controlled laboratory conditions; thus, results may hardly be directly extrapolated to an industrial scale. The absence of cultivars other than the two carrots studied here limits the generalization of the findings across genotypes. Analyses focused on physical and colorimetric properties, while no study concerning the preservation of biologically active compounds and nutritional values was conducted.

Recommended lines for further research will involve:

Evaluation of the retention of nutrients and bioactive compounds like carotenoids, anthocyanins, and phenolics is needed..

Integration of real-time process monitoring and adaptive control strategies in hybrid IR-HAD systems..

Sensory analyses and shelf-life assessments for consumer-focused quality verification.

This could also be expanded to include studies of other carrot cultivar and root vegetable crops in order to increase the applicability of the findings.

These trends will lead to increasing industrial applicability and lay a sound basis for the production of high-quality, nutritionally preserved dried vegetables by efficiently using energy..

4. Conclusions

This study thoroughly investigated the interactions between different drying methods, including HAD, IRD, and CD, and the retention of structural, functional, and color properties of carrot cultivars. The findings showed that moisture transport kinetics, tissue integrity, and pigment stability are determined by both the energy transfer mechanism and the biochemical and morphological properties of carrot tissue. Hot air drying (HAD) was characterized by long drying times, low effective moisture diffusion coefficients, and significant cell deformation. Cell deformation significantly reduced the rehydration rate, while oxidative reactions induced by long drying times, combined with the presence of oxygen in the drying air, and Maillard reactions induced by high temperatures also caused color loss..

From an infrared drying system perspective, the infrared drying system (IRD) significantly increased drying rates and significantly improved quality parameters such as color and rehydration rate compared to the hot air drying system (HAD), thanks to advantages such as volumetric energy absorption, improved moisture diffusion, preserved cellular porosity, and reduced pigment degradation. The combined drying method (CD), specifically the CD-90 protocol, utilized the synergistic effects of IR and HAD to achieve higher drying efficiency, better color stability, and superior rehydration capacity. Variety-specific responses were also observed in the study. Black carrots experienced faster moisture loss and exhibited greater structural stability and higher rehydration capacity. This is attributed to the high soluble solids content, anthocyanin-rich vacuoles, and phenolic cross-links present in black carrots.

On the other hand, based on color analysis, orange carrots, rich in β-carotene, are more susceptible to pigment degradation during prolonged heat treatment. Our findings highlight the need for effective drying strategies to be based on a holistic assessment of the textural and chemical properties of individual varieties. The CD-90 hybrid drying protocol offers an energy-efficient and industrially applicable approach to producing high-quality dried carrots that retain structural integrity, functional properties, and color stability while maintaining high rehydration capacity.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualization of the study. M.S.: Writing original draft, methodology, investigation, formal analysis. İ.D.: Conceptualization, review and editing, supervision, methodology. All authors read the final version of the manuscript and approved its publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. For more information, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yıldız Technical University for providing the laboratory infrastructure and materials necessary for this research. Generative AI was used in the preparation of the article to assist in the preliminary interpretation of the data and to improve the quality of the language. The authors have critically evaluated all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the published content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or personal conflicts of interest that could affect the work reported in this paper. This study received no specific funding that could create a conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HAD |

Hot Air Drying |

| IRD |

Infrared Drying |

| CD |

Combined Drying |

References

- ElGamal, R.; Song, C.; Rayan, A.M.; Liu, C.; Al-Rejaie, S.; ElMasry, G. Thermal Degradation of Bioactive Compounds during Drying Process of Horticultural and Agronomic Products: A Comprehensive Overview. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Koley, T.K.; Maurya, A.; Singh, P.M.; Singh, B. Phytochemical and antioxidative potential of orange, red, yellow, rainbow and black coloured tropical carrots (Daucus carota subsp. sativus Schubl. & Martens). Physiol Mol Biol Plants 2018, 24, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çetin, N.; Pinar, H.; Ciftci, B.; Kaplan, M.; Jahanbakhshi, A. Comparison of innovative and conventional drying methods for the retention of nutritional and chromatic properties of tomatoes. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2026; 115, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Tao, H.; Gao, W.; Wu, Z.; Yu, B.; Cui, B. Effect of hot-air drying on the structure, physicochemical properties, and digestibility of corn germ protein from two cultivars cultivated in East China. Food Sci Biotechnol 2025, 34, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, S.; Qin, M.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Effects of Infrared Radiation Parameters on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Rice: A Systematic Review. Food Bioprocess Technol 2025, 18, 6813–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.-L.; Shirkole, S. S.; Ju, H.-Y.; Niu, X.-X.; Xie, Y.-K.; Li, X.-Y.; Lin, Z.-F.; Zheng, Z.-A.; Xiao, H.-W. An improved infrared combined hot air dryer design and effective drying strategy analysis for sweet potato. LWT 2025, 215, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Yang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, B. Design and experiment of combined infrared and hot-air dryer based on temperature and humidity control with sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.). Foods 2023, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. (2016). Official methods of analysis of AOAC International (20th ed.). AOAC International.

- Çetin, N.; Pınar, H.; Çiftci, B.; Kaplan, M.; Jahanbakhshi, A. Comparison of innovative and conventional drying methods for the retention of nutritional and chromatic properties of tomatoes. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2026, 115, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Iancu, P.; Plesu, V.; Bildea, C. S.; Manolache, F. A. Mathematical Modeling of Thin-Layer Drying Kinetics of Tomato Peels: Influence of Drying Temperature on the Energy Requirements and Extracts Quality. Foods 2023, 12(20), 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, T.K. Convective Drying of Potato Slices: Impact of Ethanol Pretreatment and Time on Drying Behavior, Comparison of Thin-Layer and Artificial Neural Network Modeling, Color Properties, Shrinkage Ratio, and Chemical and ATR-FTIR Analysis of Quality Parameters. Potato Res. 2024, 67, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchariya, P. C.; Popovic, D.; Sharma, A. L. Thin-layer modelling of black tea drying process. J. Food Eng. 2002, 52(4), 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Khan, M. A.; Mujeebu, M. A.; Shiekh, R. A. Comparative study of microwave assisted and conventional osmotic dehydration of apple cubes at a constant temperature. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D. de C.; Steidle Neto, A. J.; Santiago, J. K. Comparison of equilibrium and logarithmic models for grain drying. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 118, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midilli, A.; Kucuk, H. Mathematical modeling of thin layer drying of pistachio by using solar energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44(7), 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolola, A. ; Jideani, A; Kapila, P. Drying kinetics of banana (Musa spp.). Interciencia 2015, 40, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Aghbashlo, M.; Kianmehr, M.; Khani, S.; Ghasemi, M. Mathematical modelling of thin-layer drying of carrot. Int. Agrophys. 2009, 23(4), 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Najla, M. M. M.; Bawatharani, R. Evaluation of Page model on drying kinetics of red chillies. Iconic Res. Eng. J. 2019, 2(10), 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Joshi, M. Modelling Microwave Drying Kinetics of Sugarcane Bagasse. Int. J. Electron. Eng. 2010, 2, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, S.; Das, H. Modelling for vacuum drying characteristics of coconut presscake. J. Food Eng. 2007, 79(1), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Lara-Aravena, E.; Di Scala, K. Effect of osmotic dehydration and drying methods on physicochemical properties of foods: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2009, 32(5), 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R. P. F. Analysis of the drying kinetics of S. Bartolomeu pears for different drying systems. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 9(11), 1772–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, F.; Kashaninejad, M. Modeling of moisture loss kinetics and color changes in the surface of lemon slice during the combined infrared-vacuum drying. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5(4), 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, A.-C.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.-Z.; Zheng, Z.-A. Quality evaluation and browning control in the multi-stage processing of Mume Fructus (Wumei). Foods 2024, 13(2), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayi, P.; Kumar, N.; Kachchadiya, S.; Chen, H.-H.; Singh, P.; Shrestha, P.; Pandiselvam, R. Rehydration modeling and characterization of dehydrated sweet corn. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11(6), 3224–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, L.; Adnouni, M.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Numerical Study on the Variable-Temperature Drying and Rehydration of Shiitake. Foods 2024, 13(21), 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoh, E. O.; Dahunsi, B. I. O. Suitability of oil-palm-broom-fibres as reinforcement for laterite-based roof tiles. Int. J. Softw. Hardw. Res. Eng. 2017, 5(4), 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Maroulis, Z. B.; Kiranoudis, C. T.; Marinos-Kouris, D. Heat and mass transfer modeling in air drying of foods. J. Food Eng. 1995, 26(1), 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Lipan, L.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Kharaghani, A.; Masztalerz, K.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A; Figiel, A. Comparison of Traditional and Novel Drying Techniques and Its Effect on Quality of Fruits, Vegetables and Aromatic Herbs. Foods 2020, 9(9), 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntsowe, K.; Workneh, T. S.; Laurie, S.; Emmambux, N. Different drying techniques and their impact on physicochemical properties of sweet potato: A review. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90(8), e70458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhile, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, B.; Dai, J.; Song, C.; Pan, Z.; Ma, H. Research progress in the application of infrared blanching in fruit and vegetable drying process. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, SH.; Ko, SC.; Kang, SM.; Cha, SM.; Ahm, GN.; Um, BH.; Jeon, YJ. Antioxidative effect of Ecklonia cava dried by far infrared radiation drying. Food Sci Biotechnol 2010, 19, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymori-Omran, M.; Askari Asli-Ardeh, E.; Taghinezhad, E.; Motevali, A.; Szumny, A.; Nowacka, M. Enhancing energy efficiency and retention of bioactive compounds in apple drying: Comparative analysis of combined hot air–infrared drying strategies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(13), 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwude, DI.; Hashim, N.; Chen, G.; Putranto, A.; Udoenoh, NR. A fully coupled multiphase model for infrared-convective drying of sweet potato. J Sci Food Agric. 2021, 101(2), 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, T. Effect of combined infrared hot air drying on yam slices: Drying kinetics, energy consumption, microstructure, and nutrient composition. Foods 2023, 12(16), 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghinezhad, E.; Kaveh, M.; Szumny, A. Optimization and prediction of the drying and quality of turnip slices by convective–infrared dryer under various pretreatments by RSM and ANFIS methods. Foods 2021, 10(2), 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Acosta-Motos, J. R.; Großkinsky, D. K.; Hernández, J. A.; Lütken, H.; Barba-Espin, G. (2019). UV-B Exposure of Black Carrot (Daucus carota ssp. sativus var. atrorubens) Plants Promotes Growth, Accumulation of Anthocyanin, and Phenolic Compounds. Agronomy 2019, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiacka, J.; Kaiser, V.; Bertsche, U.; Schwadorf, K.; Koenzen, E.; Jekle, M. How drying methods and carrot varieties influence the acrylamide formation in carrot-enriched breads? Food Chem X 2025, 29, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, H.; Farkas, I.; Buzás, J. Characterizing agricultural product drying in solar systems using thin-layer drying models: comprehensive review. Discov Food 2025, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rida, J. M.; Rachida, O.; Mohammed, B.; Lahcen, H.; Younes, B.; Lahcen, E. M.; Ali, I. Conservation of Moroccan apricot varieties using solar energy. Sol. Energy 2025, 287, 113217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, A.; Saini, R. K. Mathematical modeling of thin layer drying kinetics and moisture diffusivity study of pretreated Moringa oleifera leaves using fluidized bed dryer. Processes 2022, 10(12), 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İzli, N.; Yıldız, G.; Ünal, H.; Işık, E.; Uylaşer, V. Effect of different drying methods on drying characteristics, colour, total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of Goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, N. I. M.; Ijod, G.; Abas, F.; Ramli, N. S.; Mohd Adzahan, N.; Mohamad Azman, E. Influence of different drying methods on anthocyanins composition and antioxidant activities of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) pericarps and LC-MS analysis of the active extract. Foods 2023, 12, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, F.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Shi, J. Mechanisms of color change and smart control strategies during carrot drying. Dry. Technol. 2025, 43, 1742–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, RC.; Ademosun, OT.; Ajanaku, CO.; Olanrewaju, IO.; Walton, JC. Free Radical Mediated Oxidative Degradation of Carotenes and Xanthophylls. Molecules 2020, 25(5), 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfiya, D. S. A.; Prashob, K.; Murali, S.; Alfiya, P. V.; Samuel, M. P.; Pandiselvam, R. Drying kinetics of food materials in infrared radiation drying: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 45(6), e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Ma, Y.; Guo, X.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, C.; Gao, K.; Ma, H.; Pan, Z. Catalytic infrared blanching and drying of carrot slices with different thicknesses: Effects on surface dynamic crusting and quality characterization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 88, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, K. Mechanistic Insights into Vegetable Color Stability: Discoloration Pathways and Emerging Protective Strategies. Foods 2025, 14(13), 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N. P.; O'Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B. K. Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods: Mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, W.; Sun, D.; Li, D.; Zheng, Z.; Gao, F. Effect of Combined Infrared and Hot Air Drying Strategies on the Quality of Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat.) Cakes: Drying Behavior, Aroma Profiles and Phenolic Compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oancea, S. A Review of the Current Knowledge of Thermal Stability of Anthocyanins and Approaches to Their Stabilization to Heat. Antioxidants 2021, 10(9), 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurzyńska, A.; Janowicz, M.; Karwacka, M.; Galus, S.; Kowalska, J.; Gańko, K. The Effect of Hybrid Drying Methods on the Quality of Dried Carrot. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(20), 10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Deng, G.; Han, C.; Ning, X. Process optimization based on carrot powder color characteristics. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2015, 8(3), 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, M.; Lukyanov, A.; Rudoy, D.; Miletić, N.; Filipović, V.; Zhuravleva, V. Optimizing carrot slices drying: A comprehensive study of combined microwave and convective drying. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 460, 02001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindakshan, S.; Nguyen, T. H. A.; Kyomugasho, C.; Buvé, C.; Dewettinck, K.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. E. The Impact of Drying and Rehydration on the Structural Properties and Quality Attributes of Pre-Cooked Dried Beans. Foods 2021, 10(7), 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokida, M. K.; Maroulis, Z. B. Structural properties of dehydrated products during rehydration. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36(5), 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Guleria, S.; Kimta, N.; Nepovimova, E.; Taneja, A.; Dhanjal, D. S.; Malik, T. Black carrot: From underutilized crop to a new avenue in functional/nutraceutical enrichment applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doymaz, İ. Infrared drying kinetics and quality characteristics of carrot slices. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39(6), 2738–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, K. H.; Giwari, G. K.; Hebbar, H. U. Infrared assisted dry-blanching and hybrid drying of carrot. Food Bioprod. Process. 2013, 91(2), 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Torki, M.; Kaveh, M.; Beigi, M.; Yang, X. Characteristics and multi-objective optimization of carrot dehydration in a hybrid infrared/hot air dryer. LWT 2022, 172, 114229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, S.; Guclu, G.; Kelebek, H.; Keskin, M.; Selli, S. Comparative elucidation of colour, volatile and phenolic profiles of black carrot (Daucus carota L.) pomace and powders prepared by five different drying methods. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, ZG.; Guo, XY.; Wu, T. A novel dehydration technique for carrot slices implementing ultrasound and vacuum drying methods. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 30, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).